Abstract

This study investigates the effects of surface thermochemical treatments using boriding, nitriding, and boronitriding on the microstructure and mechanical properties of martensitic stainless steel AISI 420 ESR. Powder-pack boriding, gas nitriding, and sequential boronitriding processes were applied to enhance surface hardness, wear resistance, and adhesion. The microstructural and mechanical properties of the surface samples were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, microhardness, and nanoindentation testing. Tribological behavior was analyzed using a pin-on-disk tribometer under dry-sliding wear conditions, with applied normal loads of 5 N and 10 N and a sliding distance of 1000 m. The results showed that the borided samples exhibited the highest surface hardness, up to 1182 HV0.05, as well as brittle fracture and spallation with poor adhesion, while the boronitrided layer offered excellent adhesion. The boronitriding condition demonstrated a synergistic balance, combining high wear resistance (5.92 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1 and 4.96 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1) and reduced friction (~0.78 and ~0.67) for loads of 5 N and 10 N, respectively, without brittle fractures on the coating layer. These results confirm that duplex coating treatment is an effective strategy for improving the surface performance of AISI 420 ESR components subjected to severe operating conditions.

1. Introduction

The most commonly used types of stainless steel are austenitic Cr-Ni steels, such as AISI 304, which account for more than 50% of global stainless steel production. The next most commonly used grades are ferritic chromium steels such as AISI 409 and AISI 430. Together, these grades account for 80% of industrial consumption. The remaining 20% are high-performance austenitic and martensitic grades [1]. Despite its limited usage in industrial applications, martensitic stainless steel is relevant in many industries. Martensitic stainless steels, such as AISI 420, are commonly used in demanding engineering applications due to their balanced combination of hardness, corrosion resistance, and heat treatability [2,3]. This steel is widely employed in components such as molds [4], high-pressure pipes [5], medical devices [6], and food processing [7], where surface integrity is crucial. In aggressive environments, surface properties may not be sufficient, leading to the exploration of surface modification techniques such as thermochemical nitriding and boriding processes.

Gas nitriding is a thermochemical process used to introduce nitrogen atoms into the surface of steel, forming hard nitrides such as γ′-Fe4N and ε-Fe3N. This process enhances surface hardness, wear resistance, and, in some cases, corrosion resistance. For AISI 420, Tang et al. [8] observed substantial improvements in surface properties due to CrN precipitation, while Dalibon et al. [9] achieved similar results using short-time ion nitriding. Plasma-based nitriding techniques have also demonstrated promising outcomes. Xi et al. [10] improved both toughness and crack resistance. Çetin et al. [11] confirmed enhanced wear behavior in duplex-treated samples. Wu et al. [12] introduced a rapid plasma nitriding method that produced deep diffusion profiles. Additional studies by Shen and Wang [13], Pinedo and Monteiro [14], Li et al. [15], and Xi et al. [16] confirmed uniform phase distribution and reduced porosity, even at low nitriding temperatures. Brühl et al. [17], Menthe et al. [18], and Sun et al. [19] further highlighted improvements in corrosion resistance and hardness–depth profiles due to optimized plasma parameters.

On the other hand, boriding forms hard boride compounds such as FeB and Fe2B on the surface, significantly increasing hardness and wear resistance. Studies of boriding on AISI 420 stainless steel have demonstrated enhanced mechanical and tribological properties. Ortiz-Domínguez et al. [20] analyzed layer thickness and diffusion behavior, establishing predictive models under powder-pack conditions. Additional studies on borided martensitic stainless steels by Gunes [21] confirmed a significant increase in surface hardness (up to 2147 HV0.05) and a fivefold reduction in the wear rate compared to untreated conditions. Altintaş et al. [22] demonstrated that increasing Ekabor 2 content to produce samples via dry pressing into a die, followed by cold isostatic pressing, leads to enhanced surface properties. Investigations by Juijerm et al. [23] and Barut et al. [24] emphasized the effects of process parameters on boride layer morphology. Turkoglu et al. [25], as well as Kayali [26], found that samples subjected to boriding exhibit superior hardness as the temperature increases. Similarly, Çakır et al. [27] and Shi et al. [28] studied the beneficial effects of boron treatment on erosion, wear, and corrosion resistance.

Beyond conventional thermochemical treatments, alternative surface modification and alloy design strategies have also been explored to enhance tribological performance. For example, Hou et al. [29] reported that low-temperature field-assisted ball burnishing applied to a TA2 titanium alloy led to microstructural refinement and notable improvements in corrosion and wear resistance through surface densification and strain hardening mechanisms. In parallel, recent reviews on high-entropy alloys (HEAs) have highlighted their outstanding tribological behavior, which is attributed to compositional complexity, thermodynamic stability, and process optimization strategies [30]. Compared with these approaches, the present work emphasizes a diffusion-based surface engineering route, in which sequential boriding and nitriding are employed to generate hard compound layers while maintaining the bulk properties of martensitic stainless steel.

Previous studies have established that boriding and nitriding treatments form hard compounds such as FeB, Fe2B, γ′-Fe4N, and ε-Fe3N, which considerably improve mechanical properties, thereby increasing the surface hardness and wear resistance of heat-treated layered AISI 420 ESR steels. Our hypothesis is that sequential boronitriding will improve adhesion–wear trade-offs compared to single treatments. The aim of this study is to describe the microstructural evolution and improvements in mechanical properties and tribological behavior resulting from sequential dual boriding and nitriding treatments, ultimately seeking to optimize the surface characteristics of martensitic stainless steel for demanding applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The base material used in this study was AISI 420 Electro-Slag-Refined martensitic stainless steel. The nominal chemical composition wt.% of commercial AISI 420 ESR stainless steel, provided by the manufacturer (SISA 420 ESR, Milano, Italy), is 0.38 C, 0.45 Mn, 0.60 Si, 13.60 Cr, 0.30 V, and <0.003 S. A cylindrical rod was sectioned to obtain samples 25 mm in diameter × 10 mm in thickness.

Prior to the thermochemical treatments, the samples underwent heat treatment at 1020 °C for 3 h, followed by rapid cooling in air and a double rapid cooling cycle at 250 °C for 2 h and 200 °C for 2 h, in accordance with the technical data sheet provided by the manufacturer of the AISI 420 ESR. All samples were ground with 2000-grit SiC paper to achieve the initial roughness of the untreated QT sample and the necessary thermochemical treatment conditions. The samples were not polished after thermochemical surface treatment prior to tribological tests.

2.2. Powder-Pack Boriding Process

Boriding was carried out using the powder-pack method. The boriding medium consisted of a commercial powder mixture DURBORID ® G, supplied by Durferrit GmbH (Mannheim, Germany), containing boron carbide (B4C), as reported in the literature [31]. Samples were embedded within the powder inside AISI 304 steel containers to minimize oxidation. The containers were sealed and placed in a furnace at 950 °C for 4 h [31,32,33]. After treatment, the samples were allowed to cool to room temperature.

2.3. Gas Nitriding Process

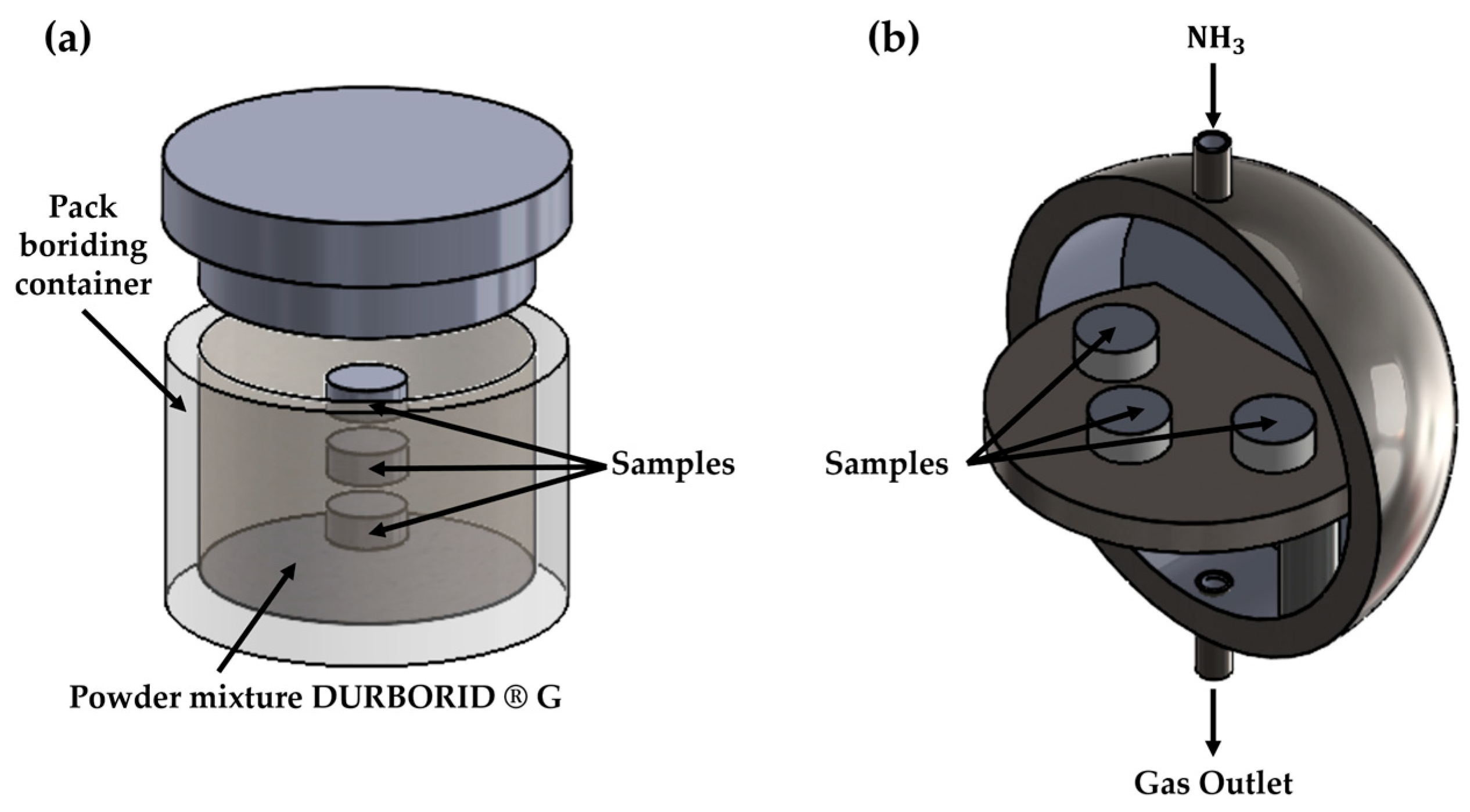

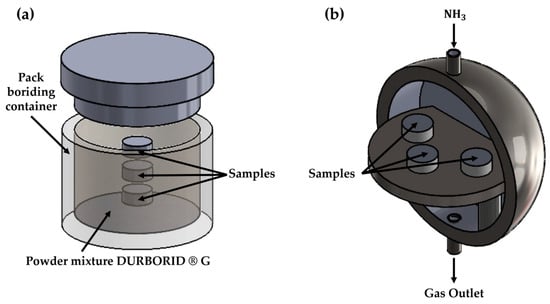

Following boriding, selected samples were subjected to gas nitriding. The nitriding process involved a staged thermal cycle: initial heating to 300 °C for 1 h, followed by stabilization and a gradual increase to 560 °C for 1 h. The nitriding atmosphere consisted of NH3 gas introduced in two stages (1.0 m3/h for 4 h and then 0.5 m3/h for 4 h), followed by a cooling cycle to room temperature. Quenched and tempered (non-borided) samples were also treated under the same nitriding conditions for comparison. A schematic representation of the surface treatment applied to the AISI 420 ESR samples is shown in Figure 1 ((a) powder-pack boriding and (b) gas nitriding). A summary of thermochemical surface treatments applied to the AISI 420 ESR samples is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the duplex surface treatment applied to the AISI 420 ESR samples, showing (a) powder-pack boriding and (b) gas nitriding.

Table 1.

Thermochemical treatments applied to the AISI 420 ESR samples.

The nitriding index can be determined with Equation (1) as follows [34]:

Equation (1) can also be expressed in the following form [1]:

With the ammonia volume flow of 1 m3/h used in the system, the sensor display on the nitriding furnace indicated a constant hydrogen partial pressure of 40% and thus a nitriding index as follows:

The hydrogen partial pressure remained constant throughout the entire process, meaning that no further adjustment of the partial pressures was necessary. According to Equations (1) and (2), the partial pressures are calculated as follows:

The true degree of dissociation αw can be calculated as follows [35]:

At a hydrogen partial pressure of 40%, we obtain

Additional process parameters are furnace pressure at 1 atm atmospheric pressure and gas purity

2.4. Post-Treatment Sample Cross-Section Preparation

After thermochemical treatment, the samples were sectioned. Then, the cross-sections were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath. The samples were ground with 600–2000 grit SiC paper, followed by polishing with 0.3 µm alumina suspension to obtain a mirror finish. Etching was performed with a solution of 25 g of iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl36H2O), 25 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl), and 100 mL of distilled water for 20 s.

2.5. Characterization Techniques

The microstructural characterization of the AISI 420 ESR steel was carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a TESCAN MIRA 3 (TESCAN GROUP, a.s., Kohoutovice, Brno, Czech Republic), in secondary electron (SE) mode at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was performed using a Bruker instrument (Bruker, Hamburg, Germany) to determine the semi-quantitative chemical composition of the samples. Metallographic phases before and after surface treatment were analyzed using an X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Phillips X’Pert 3040 (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) in Bragg–Brentano configuration (PANALITICAL, Great Malvern, UK). The instrument used a copper anode tube with Cu-Kα radiation operating at 45 kV and 30 mA, with a nominal step size of 0.02° at a scan speed of 30 s/step over a 2θ range of 20° to 90°. The microhardness profiles measured on the cross-section, with 10 repetitions at 5 positions (~50 µm) from the top surface to the base material, were obtained through Vickers indentation tests using a MicroMet 6010 microdurometer (BUEHLER, Shanghai, China) with a 50 g load and a 10 s dwell time (HV0.05), following the ISO 6507-1 standard [36]. The nanoindentation tests, with 10 repetitions for each surface condition, were performed using an RTec Instrument (RTEC-INSTRUMENTS Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) with a 150 mN load and a 12 s dwell time. The initial roughness and cross-sections of the wear tracks were evaluated using a Mitutoyo SJ-410 surface profilometer (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan). Worn pin surfaces and microhardness profiles were analyzed using a stereomicroscope (Stemi 508, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and an Axio microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), respectively.

2.6. Tribological Testing

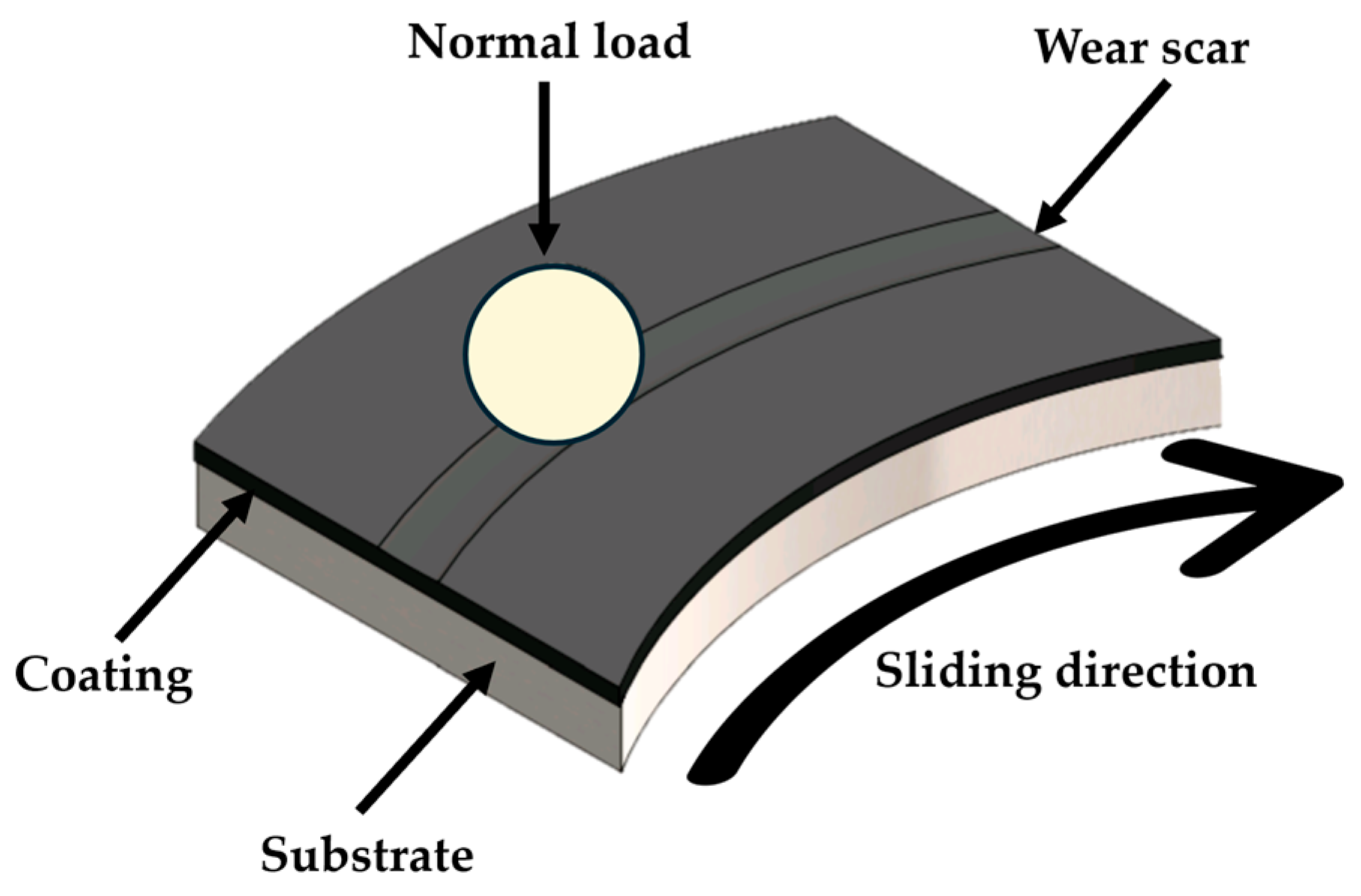

Tribological performance was evaluated using a pin-on-disk tribometer TBR (Anton Paar, Ostfildern-Scharnhausen, Germany) according to the ASTM G99-17 standard [37], as shown in the schematic in Figure 2. The wear tests for the four groups were carried out with 3 repetitions, using untreated QT as a control sample, along with boriding, nitriding, and boronitriding treatments conducted under dry-sliding conditions with alumina pins as counter bodies. The wear test parameters are shown in Table 2. The coefficient of friction was recorded during the tribological tests. The volume loss was numerically calculated via profilometry from the cross-sectional profiles of the wear track, measured at six different positions by rotating the circular wear track 60° per measurement. Untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel was not tribologically tested under 10 N due to excessive wear observed at 5 N.

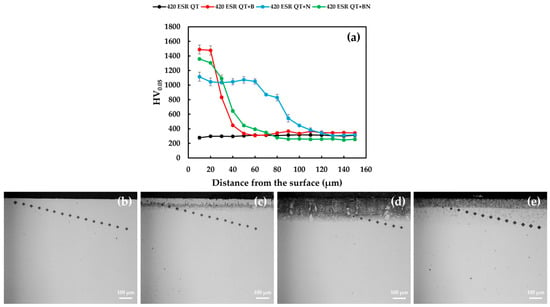

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the pin-on-disk testing according to the ASTM G99-17 standard.

Table 2.

Wear test parameters.

3. Results and Discussion

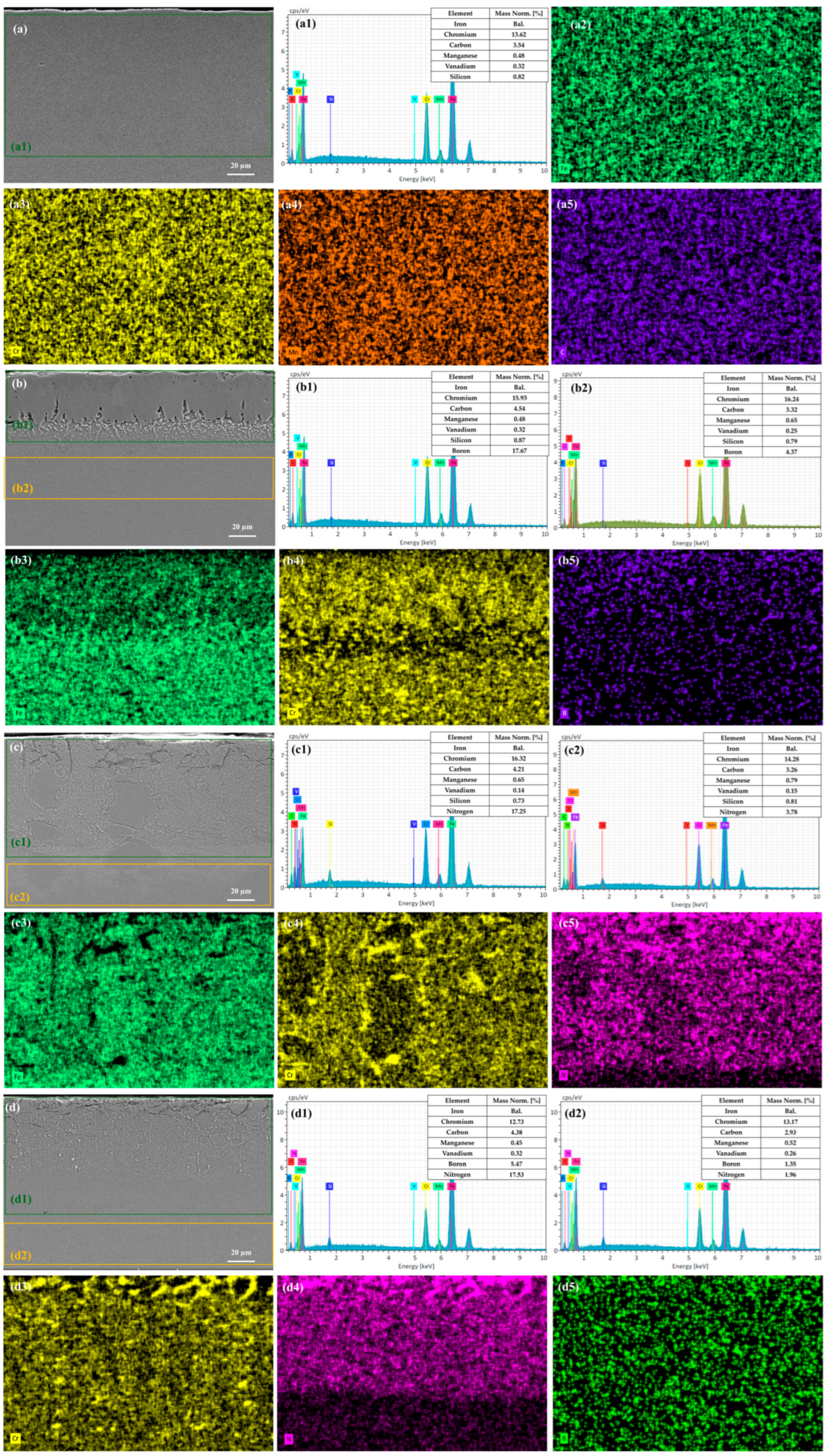

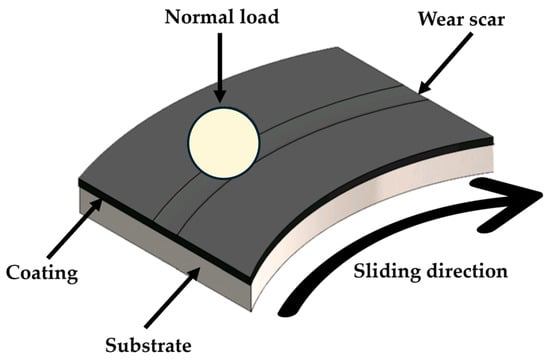

3.1. SEM and EDS Analyses

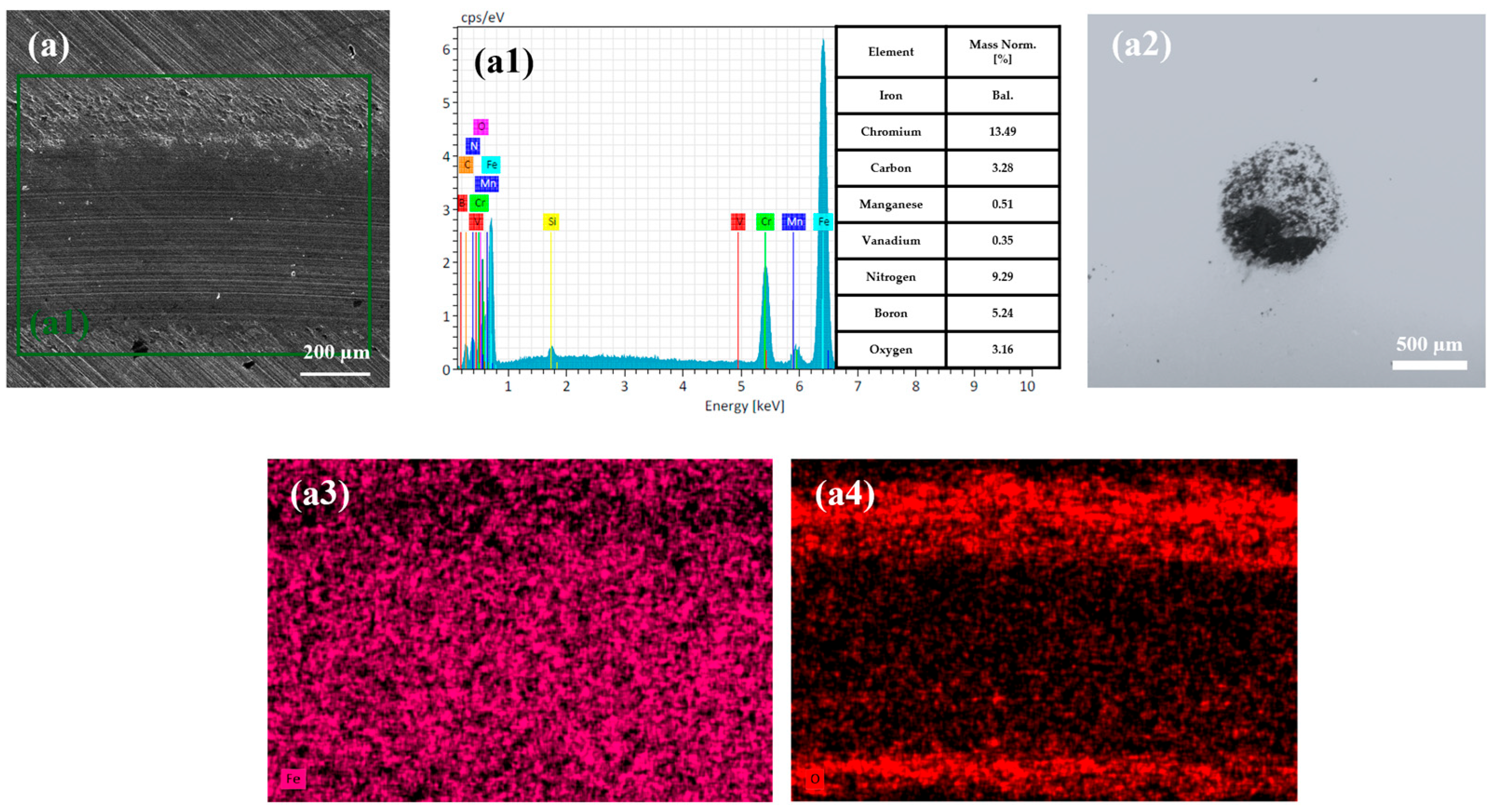

SEM micrographs provided detailed information on the morphology and quality of the quenching and tempering, boriding, nitriding, and boronitriding treatments. Additionally, EDS analyses were performed within the rectangular green area on the top of the cross-sectional SEM images, as shown in Figure 3. The QT sample (Figure 3a) exhibited a homogeneous martensitic structure. The martensitic microstructure matches the reference microstructure reported by Isfahany et al. [2]. EDS and elemental mapping of the QT sample (Figure 3(a1–a5)) showed a uniform elemental distribution, with iron, chromium, manganese, and carbon dominating the surface. These results are consistent with the nominal composition of AISI 420 ESR. The boron diffusion surface of the cross-section (Figure 3b) presented an external layer of FeB with a porous surface, followed by internal Fe2B with a dense and compact surface layer and a characteristic sawtooth profile caused by FeB and Fe2B phases, reaching an average thickness of 62.1 µm. Similar external layers of FeB followed by internal dense and compact Fe2B surface layers have been reported in the literature [21,24,27]. The external FeB’s porous quality was attributed to the optimum furnace conditions, causing a homogeneous distribution of the boron atoms and allowing them to form a continuous boride layer [25]. This morphology is characteristic of anisotropic boron diffusion, as documented in powder-pack boriding studies by Ortiz-Domínguez et al. [20] and further analyzed in their kinetic modeling work [38]. Abbasi-Khazaei and Mollaahmadi [5] also reported similar profiles, in which irregular interfaces promoted mechanical anchoring but could act as sites for crack propagation. This dual effect was also emphasized by Kayali and Taktak [3], who associated the sawtooth-shaped geometry with reduced adhesion of the boride layers. Semi-quantitative EDS and chemical elemental mapping analysis of the boron-treated sample showed significant boron enrichment at the surface (Figure 3(b1)). The boron content was approximately 17.67 wt.% near the surface, gradually decreasing toward the substrate, which presented a boron content of approximately 4.37 wt.%, as shown in Figure 3(b2). The iron content correspondingly decreased from the core to the outer region, confirming active diffusion of boron, with iron and chromium promoting the formation of a well-developed surface layer composed of FeB, Fe2B, and Cr2B (see Figure 3(b3–b5)). Abbasi-Khazaei and Mollaahmadi [5] reported comparable gradients, reinforcing the effective formation of FeB and Fe2B layers under boriding conditions. The nitrided cross-section surface (Figure 3c) revealed surface γ′-Fe4N and an ε-Fe3N layer with nitride precipitation in the diffusion zone, uniform thickness, and a flat interface, suggesting a controlled nitrogen diffusion process. Cracks at the surface were oriented parallel to the surface and developed within the nitrided layer but not at the interface. This phenomenon during the nitriding of AISI 420 stainless steel was reported by Tuckart et al. [39], who reported that the presence of precipitated particles and local residual stresses are possible causes of such a phenomenon. Dalibon et al. [9] observed comparable features in ion-nitrided AISI 420, reporting the formation of compact ε-Fe3N compound layers with strong bonding and low porosity. Li et al. [15] reported similarly clean interfaces produced by active screen plasma nitriding; such interfaces are favorable for mechanical stability. However, Pinedo and Monteiro [14] noted that abrupt transitions, although structurally sound, may limit the layer’s ability to withstand high cyclic stresses. The EDS and chemical elemental mapping analysis of the nitrided sample (Figure 3(c2–c5)) detected nitrogen in the diffusion zone, accompanied by a slight decrease in iron content. The nitrogen decreased gradually from the surface to the substrate, with phases rich in chromium and nitrogen visible in Figure 3(c3–c5). These findings are consistent with the ion-nitriding results described by Dalibon et al. [9], who also observed surface nitrogen enrichment without significant phase mixing. Li et al. [15] similarly reported surface nitrogen levels exceeding 8 wt.% in plasma-nitrided AISI 420, which correlates with the formation of ε and γ′ nitrides. The boronitrided cross-section surface (Figure 3d) exhibited a layered morphology with a denser outer zone and a gradual transition into the substrate caused by the dual formation of FeB, Fe2B, γ′-Fe4N, and ε-Fe3N phases. This layer had a smoother appearance and more continuous morphology than the well-known sawtooth shape of borided coatings. It was also possible to observe cracks on the outer layer oriented parallel to the surface. This can be attributed to the internal stresses arising between the FeB and Fe2B phases, generating cracks parallel to the surface [40]. Similarly, cracks oriented parallel to the nitrided layer may appear due to the presence of precipitated particles and local residual stresses, which are possible causes of this phenomenon [39]. EDS revealed that boron was concentrated on the outermost surface, reaching approximately 5.47 wt.%, while nitrogen was distributed regularly below the surface with a maximum value of 17.53 wt.% (Figure 3(d1)). The boron and nitrogen contents decreased to approximately 1.35 wt.% and 1.95 wt.%, respectively, in the substrate (Figure 3(d2)). This layered composition supports the formation of a duplex structure, where boron dominates the outer zone with nitrogen in the transition region. The chemical elemental mapping analysis revealed the simultaneous presence of boron and nitrogen, distributed in layered zones (Figure 3(d3–d5)). The boronitrided layer indicated high concentrations of nitrogen and boron elements in the coating layer, promoting the formation of borides and nitrides of iron and chromium. At the surface, the concentration of nitrogen and boron was higher than that in the substrate underneath the boronitrided layer. Initial boriding and subsequent nitriding promoted a combined diffusion of Ni and B, generating a limited diffusion of nitrogen and producing a thinner boronitrided layer than the nitrided layer (see Figure 3d). This result can be attributed to the formation of a B-rich zone limiting diffusion underneath the boride layer. In addition, chromium concentrates strongly on the surface with nitrogen in the outer region of the nitride layer (see Figure 3(d1–d5)) due to CrN nitride precipitation at the grain boundary [13].

Figure 3.

SEM cross-sectional micrographs for (a) quenching and tempering, (b) borided, (c) nitrided, and (d) boronitrided treatments, EDS spectra with elemental chemical analyses for (a1) quenching and tempering, (b1,b2) borided, (c1,c2) nitrided, and (d1,d2) boronitrided treatments and chemical elemental mapping for (a2–a5) quenching and tempering, (b3–b5) borided, (c3–c5) nitrided, and (d3–d5) boronitrided treatments.

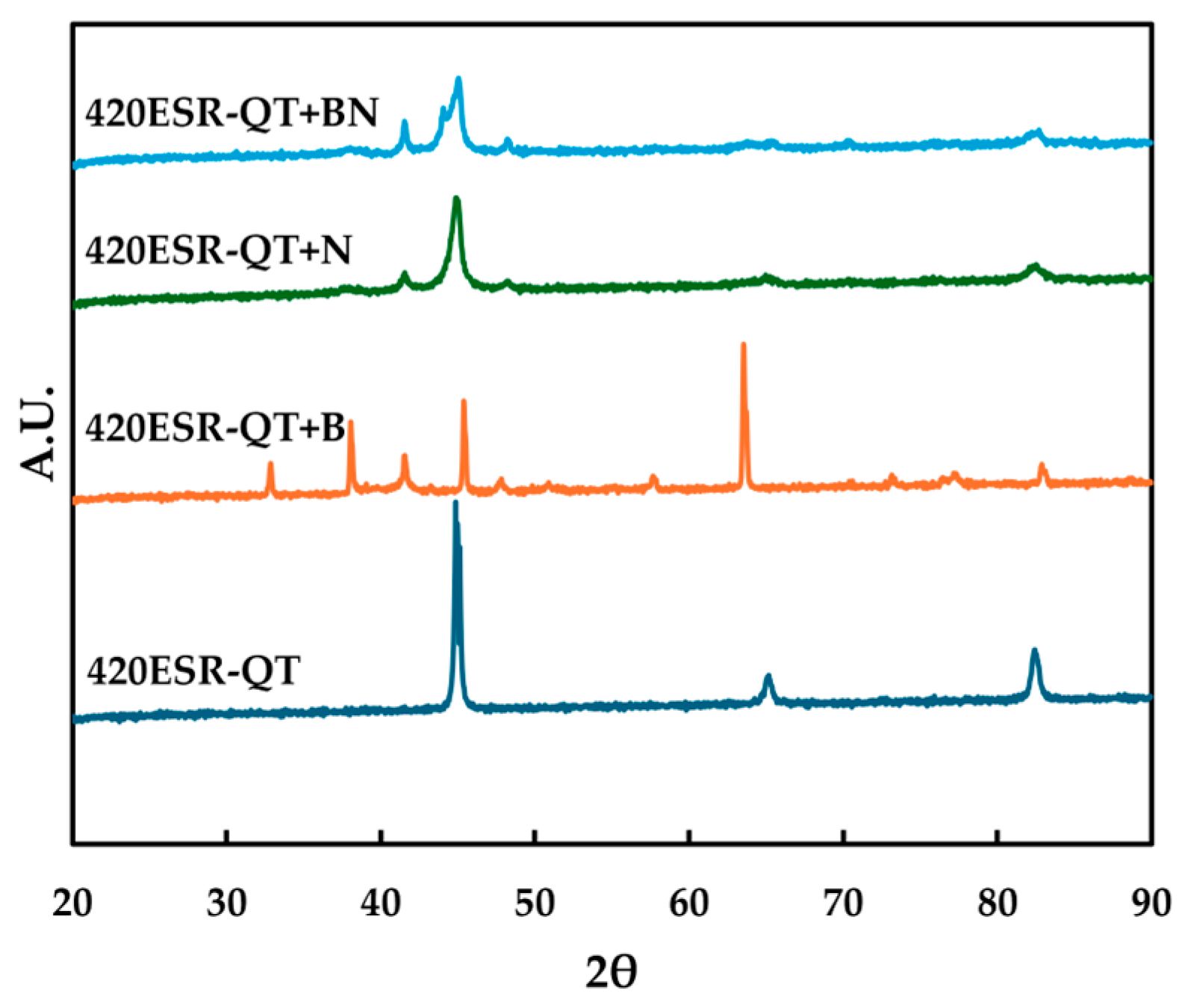

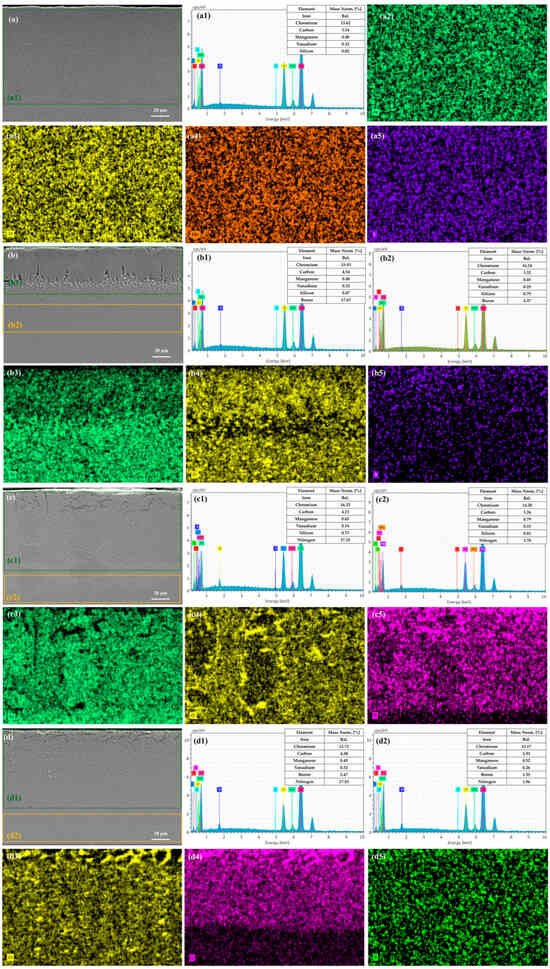

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

An X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed to identify the crystalline phases present in each sample and evaluate the phase evolution induced by the thermochemical treatments, as shown in Figure 4. The QT sample exhibited diffraction peaks corresponding exclusively to α-Fe (martensitic phase), with characteristic reflections at 44.6°, 65.0°, and 82.3°. These peaks are consistent with the ferritic/martensitic matrix of AISI 420 ESR and match the reference pattern for α-Fe (PDF 06-0696). The borided sample exhibited additional peaks appearing at 38.3°, 43.6°, and 47.8°, corresponding to Fe2B (PDF 04-019-2627). Peaks were also observed at 45.1° and 65.0°, attributed to FeB (PDF 04-007-6176). These peaks confirm the formation of an iron boride layer as a result of boron diffusion on the steel surface. The high intensity of the Fe2B peaks indicates that this phase is dominant in the outer region, in agreement with Barut et al. [24], who also reported these crystalline structures. The nitrided sample showed peaks at 41.2° and 43.6°, attributed to ε-Fe3N (PDF 04-007-3377), and a weak peak at 47.9° corresponding to γ′-Fe4N (PDF 01-071-4924). The appearance of these peaks confirms successful nitrogen diffusion and nitride formation. The presence of both ε and γ′ phases suggests a typical compound layer morphology as reported by Pinedo et al. [14] and Li et al. [15]. A more complex diffraction pattern was observed in the boronitrided sample. Peaks associated with Fe2B (38.3°, 43.6°, 47.8°), FeB (45.1°, 65.0°), ε-Fe3N (41.2°, 43.6°), and γ′-Fe4N (47.9°) were all detected. Additionally, weak peaks of Cr2B were identified near 41.2° and 82.2° (PDF 04-004-1242), suggesting the involvement of Cr during the boronitriding process. This multiphase composition confirms the successful formation of a duplex layer and reflects a layered structure.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction pattern for the 420 ESR QT and compound coatings after boriding and nitriding.

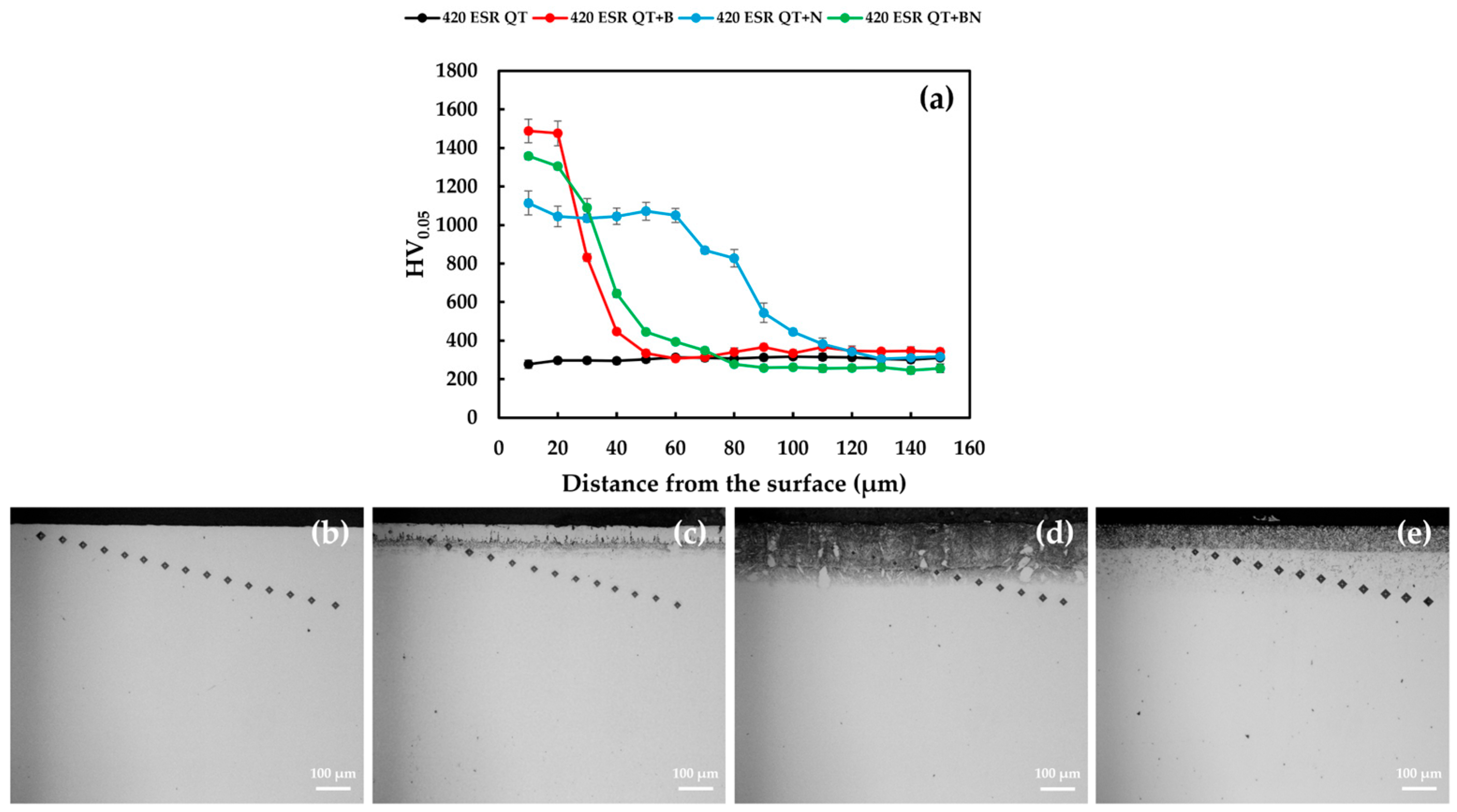

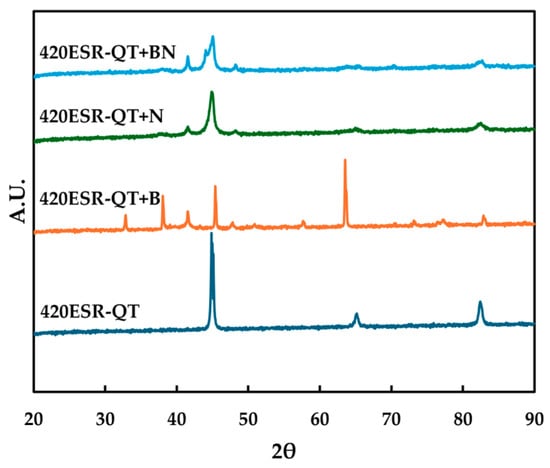

3.3. Microhardness Vickers

The microhardness Vickers HV0.05 profiles revealed significant differences in surface hardness among the various treatments, as shown in Figure 5a, and hardness Vickers indentations on the cross-section from the surface to the substrate for (b) quenching and tempering, (c) borided, (d) nitrided, and (e) boronitrided treatments. As expected, the QT sample showed the lowest surface hardness, averaging 304 ± 12.9 HV0.05 (see Figure 5a,b). The borided sample exhibited the highest surface hardness, with values reaching 1489.6 ± 61.4 HV0.05. This remarkable increase is attributed to the formation of the FeB and Fe2B phases in the hard boride layer, known for its high resistance to plastic deformation, as shown in Figure 5c. Kayali [26] reported hardness values of boride layers reaching 1160 to 1700 HV0.05 at 30 µm from the surface, depending on the process parameters. The nitrided sample reached an average surface hardness of 1114.1 ± 61.8 HV0.05, confirming the formation of γ′-Fe4N and ε-Fe3N nitrides in a deeper compound layer (see Figure 5d). Although slightly lower than that of the borided sample, this hardness still represents a significant improvement over the untreated conditions. These results are consistent with those of Wu et al. [12], who reported surface hardness values between 920 and 957 HV0.05 under plasma nitriding. The boronitrided sample reached a surface hardness of 1357.1 ± 15.5 HV0.05. This hardness value is lower than that of the borided samples, reflecting balanced hardness due to the combined FeB and Fe2B at the surface, as well as γ′-Fe4N and ε-Fe3N phase structures in the black zone layer and below the black zone layer (see Figure 5e), with contributions from both borides and nitrides.

Figure 5.

Hardness Vickers HV0.05 on the cross-section for (a) all conditions, hardness indentations on the cross-section for (b) quenching and tempering, (c) borided, (d) nitrided, and (e) boronitrided treatments.

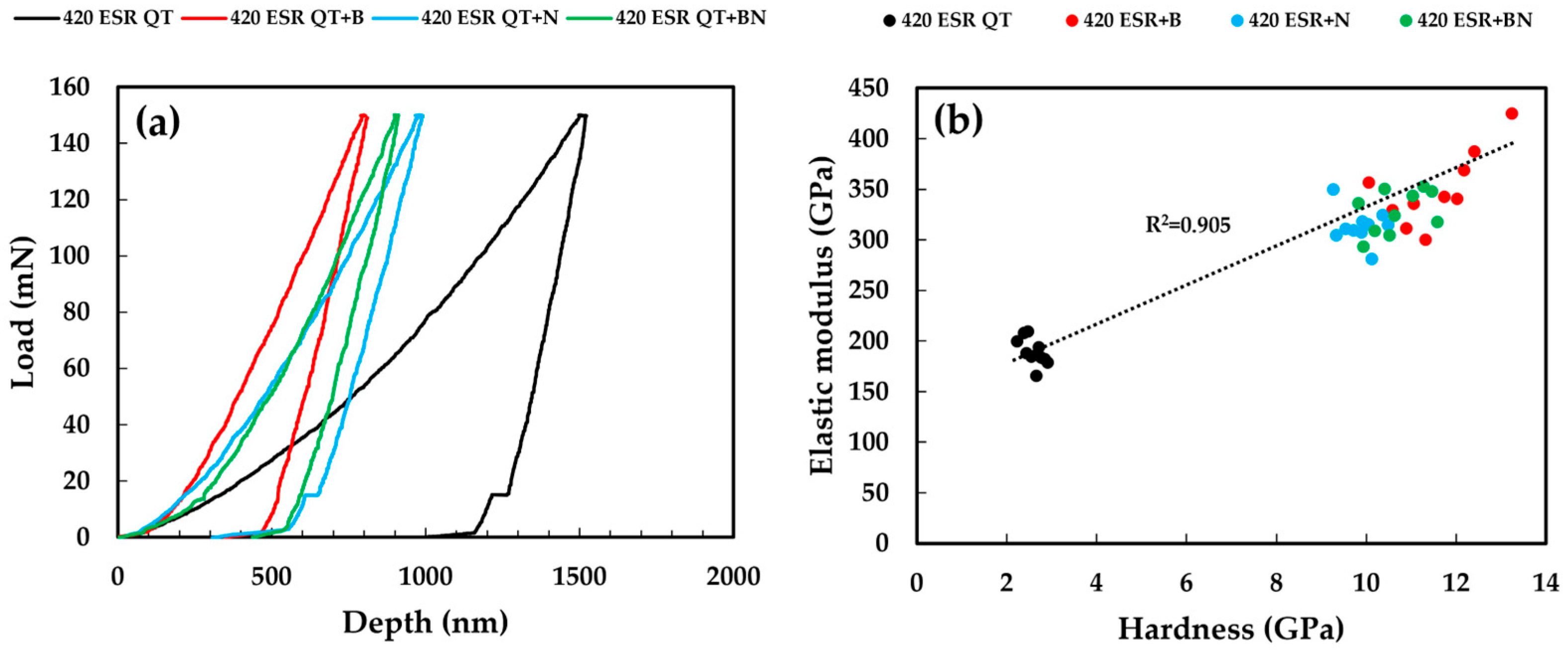

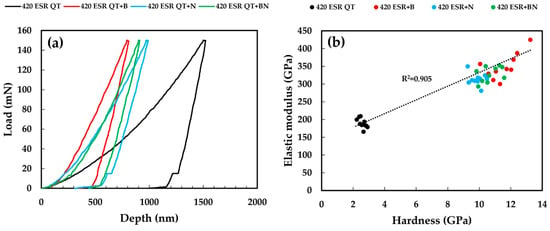

3.4. Nanoindentation Tests and Surface Roughness

The results of the nanoindentation load and unload curve for the untreated QT condition and the thermochemically treated boriding, nitriding, and boronitriding conditions are shown in Figure 6. The size effect shows an increase in hardness with a decrease in indentation depth (see Figure 6a). The QT sample load and unload curve presented a maximum indentation depth of 1520.5 nm. In comparison, the nanoindentation load and unload curves for boriding, nitriding, and boronitriding yielded maximum depths of 804.7 nm, 920.2 nm, and 912.7 nm, respectively. The relationship between the elastic modulus E and the hardness values H obtained from nanoindentation of all samples is shown in Figure 6b as scattered points. The data calculated from nanoindentation showed scattered points for the four groups, which belonged to the 420 ESR surfaces and the thermochemically treated surfaces. The homogeneous behavior of the black dots could be observed in the untreated 420 ESR tests. In contrast, thermochemically treated coatings resulted in a higher elastic modulus and greater hardness, translating into a visible distribution of blue, green, and red scatter points induced by defects and residual oxides in the surface coatings. The results showed a decrease in indentation depth, with the borided sample exhibiting the lowest penetration. The mechanical properties in terms of the elastic modulus (E) and hardness (H) are shown in Table 3. The results for the QT samples showed an elastic modulus of 189.4 ± 13.6 GPa and a hardness of 2.6 ± 0.3 GPa. Similar results were reported by Ben Lenda et al. [41] for 420 stainless steel subjected to normalizing heat treatment at 1075 °C and annealing at 250 °C, yielding an elastic modulus of 211 GPa and a hardness of 4 GPa. The mechanical properties in the borided samples increased the elastic modulus to 349.7 ± 36.8 GPa and the hardness to 11.5 ± 0.4 GPa, caused by FeB, Fe2B and Cr2B. García-Léon et al. [42] reported the effects on mechanical properties caused by the FeB and Fe2B phases in low-carbon stainless steel, which exhibited good resistance to plastic deformation in the layer, helping to prevent adhesion failures of the ceramic layer and conferring high wear resistance. The secondary Cr2B phase in the boride layer promotes precipitation strengthening, enhancing grain boundary stability, thereby improving the alloy’s hardness and wear resistance [43]. The effect of Cr2B as the precipitation strengthening phase during the boriding process effectively impedes dislocation motion, leading to significantly enhanced surface hardness and strength [44]. The elastic modulus and hardness of the nitrided samples produced by γ′-Fe4N and ε-Fe3N were 313.6 ± 17.2 GPa and 9.8 ± 0.5 GPa, respectively. Manfrinato et al. [45] reported the mechanical properties of nitriding at 400 °C on 420 stainless steel, with an elastic modulus of 281 ± 21 GPa and a hardness of 14.1 ± 1.0 GPa. The boronitrided samples showed intermediate mechanical properties, with a hardness of 10.7 ± 0.8 GPa and an elastic modulus of 327.9 ± 21.3 GPa caused by FeB, Fe2B, γ′-Fe4N, and ε-Fe3N. These results indicate a synergistic effect combining the mechanical properties of the elastic modulus and hardness. The H/E ratio is considered an indicator of wear resistance and the ability to plastically deform the tribological frictional contact without failure, where a higher ratio suggests better performance [46]. The H/E ratios presented in Table 3 revealed an increase for all thermochemically treated surfaces, with boron-treated samples mostly exhibiting higher ratios of ~0.0328. On the other hand, the nitrided sample showed a trend with lower ratios of ~0.0326. Moreover, the boronitrided sample presented an intermediate tendency ratio combining the mechanical properties of hardness and the elastic modulus with a ratio of ~0.0312. The initial roughness values of the untreated QT sample and the thermochemically treated borided, nitrided, and boronitrided samples are presented in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Nanoindentation test results for (a) load–unload nanoindentation curves and (b) scatter plots of the elastic modulus vs. hardness.

Table 3.

Nanoindentation mechanical properties and initial roughness.

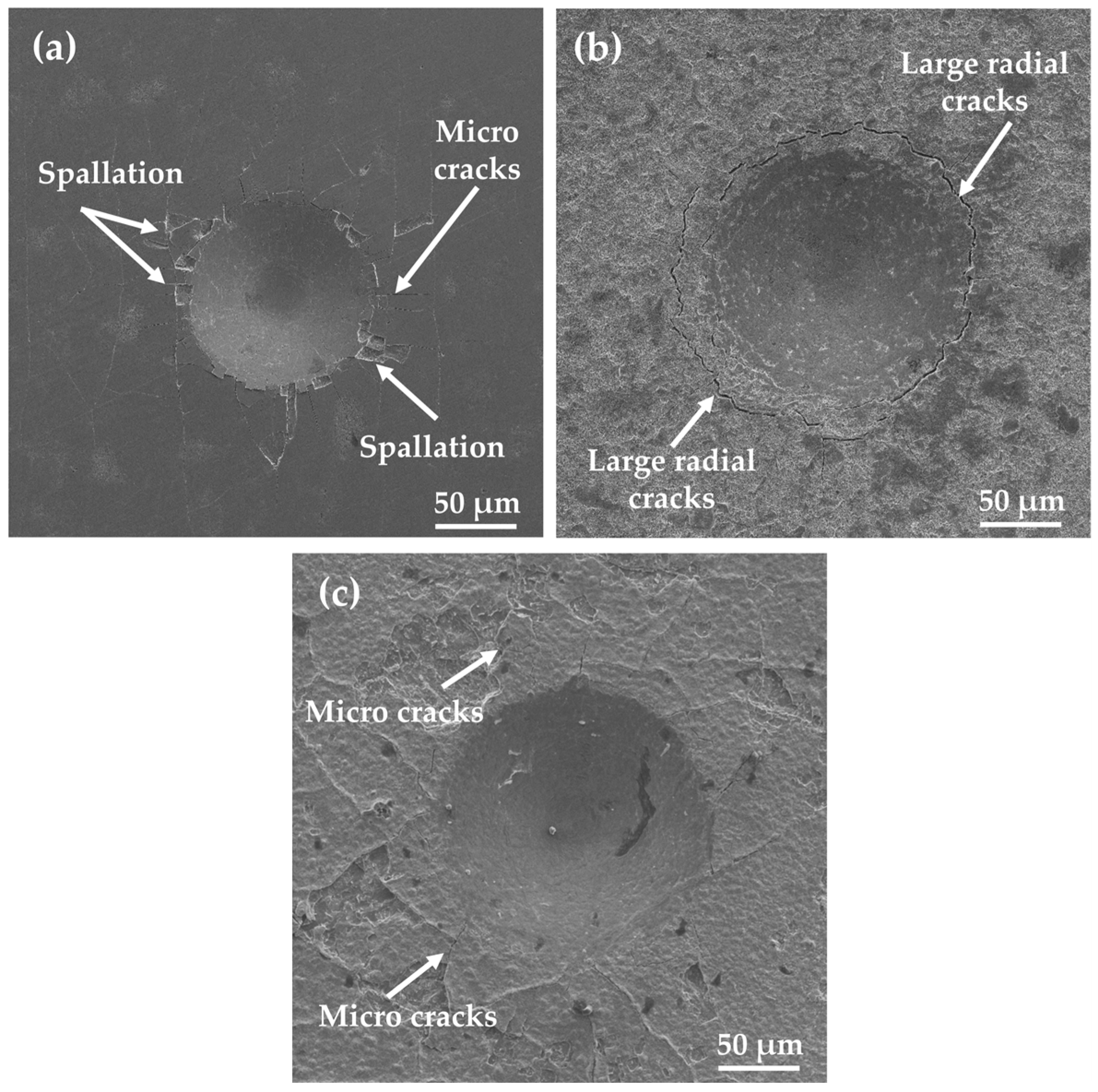

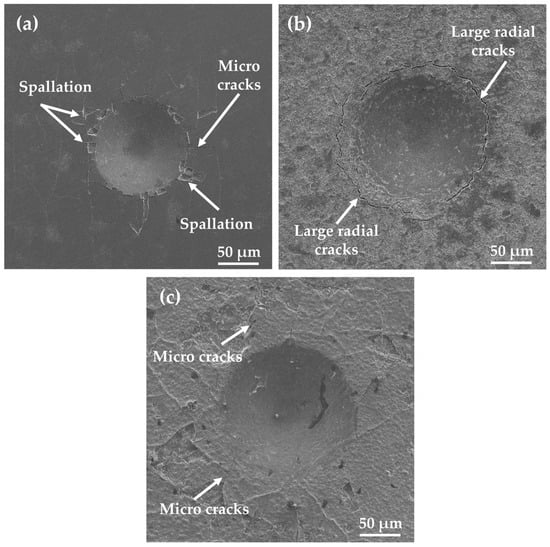

3.5. Rockwell-C Adhesion Properties

The adhesion behavior of the surface layers was evaluated using the Rockwell-C indentation method according to the VDI 3198 standard [47], as shown in Figure 7, which presents SEM images of Rockwell-C indentations on the borided, nitrided, and boronitrided AISI 420 ESR stainless steel substrates. The borided sample (Figure 7a) exhibited poor adhesion. Here, the indentation zone was surrounded by radial cracks and localized spallation, indicating the brittle behavior of the hard boride layer caused by the phases FeB and Fe2B, where these failures represent the HF2–HF3 type of adhesion strength quality. Similar adhesion failures in borided coatings were reported by Kayali [3] and Barut [24], who observed radial cracking and flaking around Rockwell indentations. The nitrided sample (Figure 7b) showed brittle fracture characteristics caused by γ′-Fe4N and ε-Fe3N. The indentation mark revealed signs of large radial cracking, suggesting the formation of a ductile and well-integrated nitride layer. These failures in the nitrided layer are related to the HF1–HF2 type of adhesion strength quality. In contrast, the boronitrided sample (Figure 7c) showed significantly improved adhesion produced by FeB, Fe2B, γ′-Fe4N, and ε-Fe3N when compared to the boriding and nitriding conditions. While minor radial lines were visible, no flaking or delamination occurred around the indentation, representing an HF1 type of adhesion strength quality.

Figure 7.

SEM images of Rockwell-C indentations for the (a) borided, (b) nitrided, and (c) boronitrided samples.

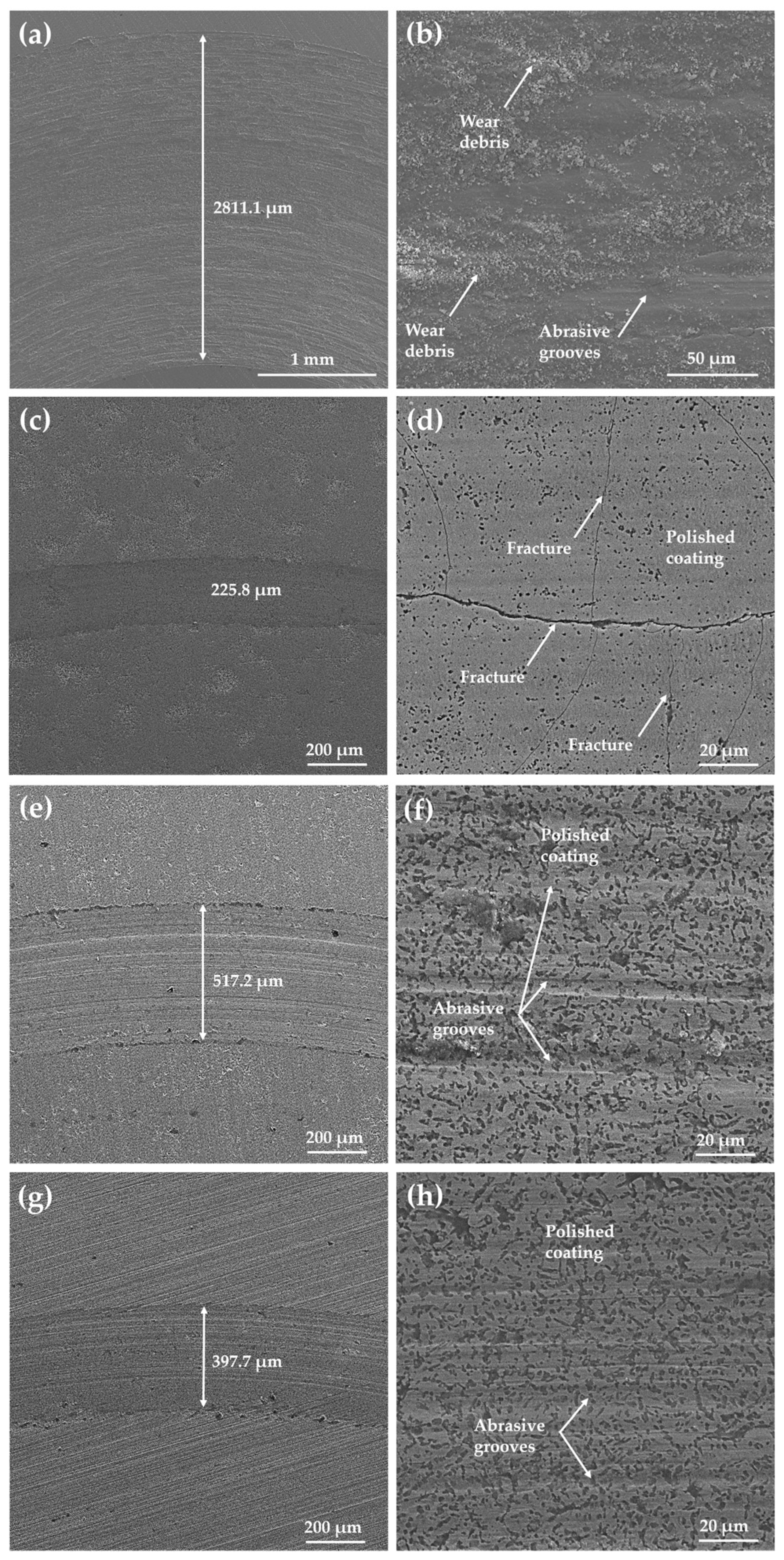

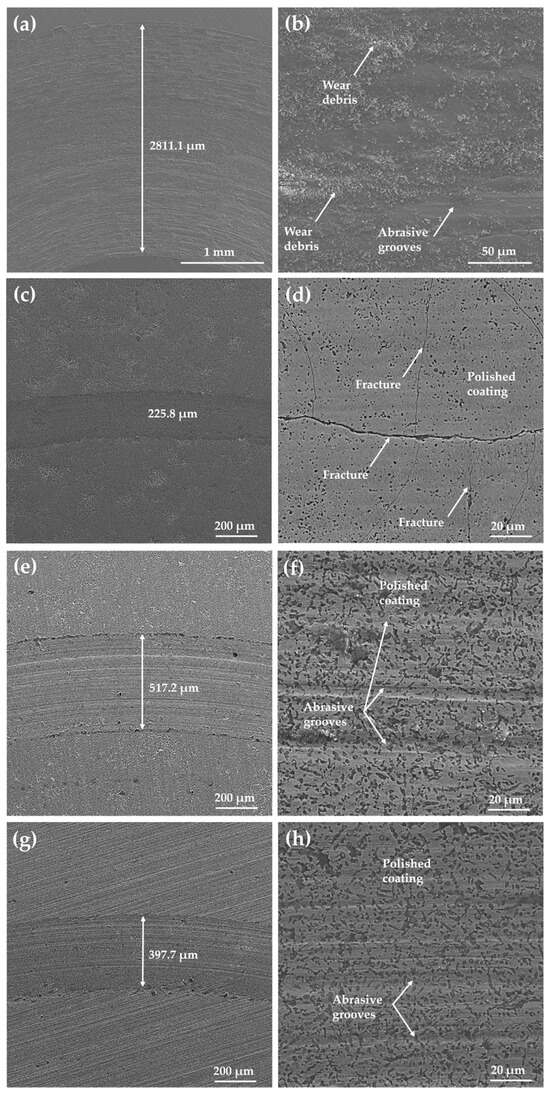

3.6. Worn Surface Characterization

Pin-on-disk wear tracks of the untreated and treated borided, nitrided, and boronitrided samples with an applied load of 5 N are shown in Figure 8. Untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel exhibited severe wear with a cross-sectional width of 2811.1 µm, as shown in Figure 8a. A high-magnification micrograph showed that the main wear mechanisms were abrasion grooves, adhesion, and debris agglomeration, as shown in Figure 8b. The borided sample presented the narrowest wear track width of 225.8 µm, as shown in Figure 8c, with a polished, smooth worn surface and the presence of microcracks and brittle fractures in the coating layer, as shown in Figure 8d. The nitrided sample presented a cross-sectional wear track width of 517.2 µm, as shown in Figure 8e. The main wear mechanisms were abrasion grooves on a worn, polished surface, exposing the composite layer and the continuous precipitation of nitrides (dark structures) in the diffusion zone (see Figure 8f). It is well known that the mechanical properties of borided and nitrided layers, such as hardness and the elastic modulus, have a significant impact on improving wear resistance. The wear resistance of the borided and nitrided surfaces shown in Figure 8d,f confirm that wear resistance was improved as hardness and the elastic modulus increased, as shown in Table 3. Different studies [10,11,12,13,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24] have described the effects of boriding and nitriding treatments on the hardness of ε-Fe3N, γ′-Fe4N, FeB, Fe2B, and CrB phases within the coating layers on 420 ESR, thereby improving both mechanical properties and tribological behavior. The worn boronitrided surface exhibited a cross-sectional wear track width of 397.7 µm, as shown in Figure 8g. As shown in Figure 8h, the wear track at high magnification presents less severe abrasion grooves due to the protective borided layer that exposed the nitride precipitation (dark structures) of the composite layer precipitation in the diffusion zone. The worn surface of the boronitrided sample showed slight signs of abrasion and scratches on the smooth worn surface.

Figure 8.

SEM images of wear tracks under a 5 N load for (a,b) QT 420 ESR stainless steel and (c,d) boriding, (e,f) nitriding, (g,h), and boronitriding conditions.

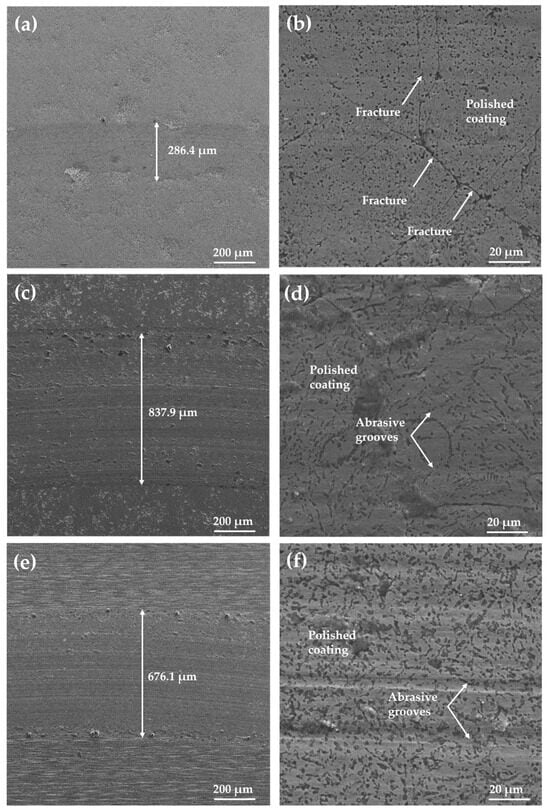

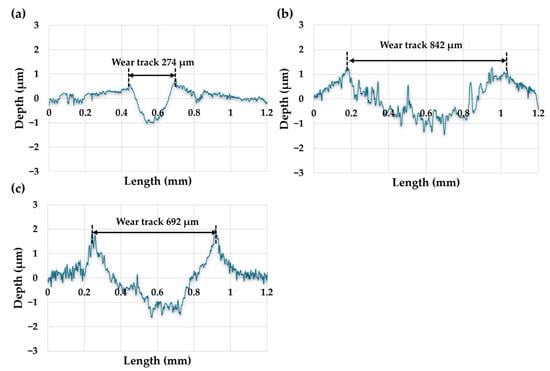

The wear tracks of borided, nitrided, and boronitrided samples with an applied load of 10 N are shown in Figure 9. Untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel was not tribologically tested with a 10 N load due to excessive wear produced at an applied load of 5 N. The borided coating revealed a cross-section wear track of 286.4 µm, as shown in Figure 9a. The surface was polished, presenting minor damage with visible microcracks and brittle fractures of the hard coating layer, as shown in Figure 9b. The brittle crack fractures shown in Figure 8d and Figure 9b can be explained by initial residual stress cracking and the presence of porosity, which can promote crack propagation [25], as shown in Figure 3b. The fracture in the coating layer was produced by the brittle boride layer acting as a site for crack initiation and propagation [48]. The cross-sectional wear track width for the nitrided sample was 837.9 µm, as shown in Figure 9c. The main wear mechanisms were slight abrasion and polishing of the surface, as shown in Figure 9d. Finally, the boronitrided worn surface exhibited a wear track width of 676.1 µm, as shown in Figure 9e. The boronitrided worn surface showed abrasion scratches on the polished surface, which can be seen in Figure 9f. Under both loads, 5 N and 10 N, the measurement of the wear track width of the combined boronitriding process was between that of boriding and nitriding, demonstrating a synergistic balance between boriding and nitriding treatments by combining the mechanical properties—including elastic modulus, hardness, and H/E ratio (Table 3)—with the coating adhesion of Rockwell-C indentation in terms of wear resistance.

Figure 9.

SEM images of wear tracks under a 10 N load for (a,b) boriding, (c,d) nitriding, (e,f), and boronitriding conditions.

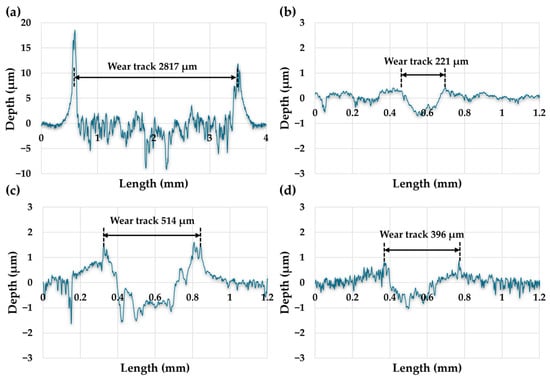

The profilometry on the cross-section of the wear tracks under a load of 5 N for (a) untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel and (b) borided, (c) nitrided, and (d) boronitrided steel is shown in Figure 10. The profilometer test on the cross-section of the wear track shows severe damage, presenting abrasion grooves on the untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel, with a value of 2817 µm, as shown in Figure 10a. Meanwhile, the cross-section on the borided surfaces presented wear marks of 221 µm, showing slight signs of surface damage, with a reduction in abrasion grooves (see Figure 10b). The cross-section wear track on the nitrided surface showed an increase of 514 µm on the wear marks with abrasion grooves (see Figure 10c). The combined effect of boronitriding on the wear track was 396 µm, as shown in Figure 10d. This beneficial effect can be explained by the combined effect of boriding and nitriding on the mechanical properties of the surface boronitrided layer, such as hardness and the elastic modulus, improving the coefficient of friction and wear without the detrimental surface fractures of hard boriding and the high deformation of nitriding treatments.

Figure 10.

Profilometry of cross-section wear tracks under a 5 N load for (a) QT 420 ESR stainless steel, (b) boriding, (c) nitriding, and (d) boronitriding conditions.

A cross-section of the wear tracks under a load of 10 N for (a) boriding, (b) nitriding, and (c) boronitriding is shown in Figure 11. The boronitriding profilometer test on the cross-section of the wear track showed a slight increase in the surface wear damage from 221 µm to 274 µm compared with the 5 N boriding wear results, as the normal load was increased to 10 N, with some abrasion grooves (see Figure 11a). The worst cross-section wear track condition on the treated surface was observed on the nitrided surface, with a width of 842 µm and severe abrasion grooves (see Figure 11b). The combined mechanical and tribological effect of boronitriding on the wear track was 692 µm, as shown in Figure 11c. The profilometer test on the cross-section of the wear tracks presented slight evidence of surface damage, yielding a reduction in abrasion grooves on the nitrided, borided, and boronitrided surfaces. This result can be explained by improvements in mechanical properties, such as the hardness and elastic modulus of the nitrided, borided, and boronitrided surface layers, decreasing the coefficient of friction and wear.

Figure 11.

Profilometry of cross-section wear tracks under a 10 N load for (a) boriding, (b) nitriding, and (c) boronitriding conditions.

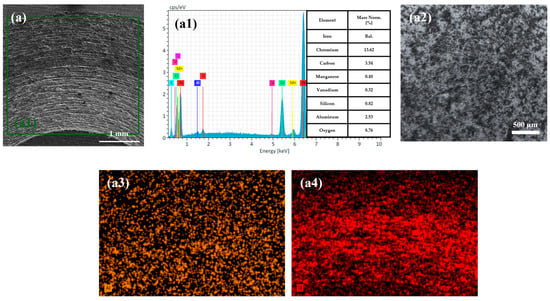

The worn surface characterization of the QT 420 ESR stainless steel wear track surface and alumina pin after wear tests with a 5 N load is shown in Figure 12. The SEM micrograph and elemental composition, EDS, and mapping analyses of the untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel are presented in Figure 12(a,a1). The worn surface and EDS mapping show the presence of chemical elements from the base untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel, as shown in Figure 12. The wear scar on the alumina pin evidences the adhesion mechanism of the untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel material (Figure 12(a2)). The results also indicate that the element of the alumina pin was transferred via adhesion from the pin to the base metal after adding the element of aluminum. Semi-quantitative EDS and chemical mapping detected the presence of the aluminum element, indicating that adhesion is a wear mechanism due to the transfer of pin material onto the wear surface (see Figure 12(a1–a3)). The adhesive wear mechanism could be caused by the poor mechanical properties of the QT 420 ESR stainless steel, which promote soft mechanical counter-body contact. This mechanical counter-body contact behavior of adhesive wear mechanisms caused by the transfer from a hard pin to a soft material with poor mechanical properties was previously reported by the authors in [49]. Oxygen can also be observed on the worn surface (see Figure 12(a4)), which indicates a significant contribution from the oxidative wear mechanism [50].

Figure 12.

Worn surface characterization of untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel: (a) SEM wear track surface micrograph, (a1) elemental composition EDS, (a2) stereoscopic micrographs of the alumina spheres after wear, and (a3,a4) mapping analyses under a 5 N load.

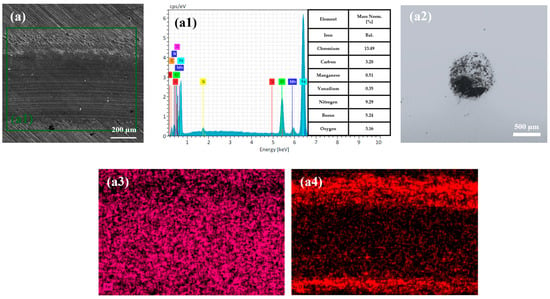

The worn boronitrided surface and alumina pin after wear tests with a 10 N load are shown in Figure 13(a–a2). The elemental composition EDS indicates the presence of boron and nitrogen in the QT 420 ESR stainless steel, as shown in Figure 13(a1). The presence of boron and nitrogen content on the wear track confirms the presence of a layer formed on the surface without evidence of aluminum, which suggests that the adhesion wear mechanism was not promoted by the transfer of pin material onto the wear surface, as demonstrated in Figure 13(a1). Meanwhile, slight evidence of adhesion on the alumina sphere was also observed (Figure 13(a2)). In contrast to the untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel, the boronitrided sample showed the presence of oxidized wear debris located in areas adjacent to the worn tracks, as shown in Figure 13(a3,a4). The chemical mapping shows the protective effect of oxidation produced in the wear track. Similarly, previous results reported that a nitrided coating promoting oxidized wear debris located in the adjacent areas of the worn track changes the wear mechanism [49].

Figure 13.

Worn surface characterization of the boronitrided surface: (a) SEM wear track surface micrograph, (a1) elemental composition EDS, (a2) stereoscopic micrographs of the alumina spheres after wear, and (a3,a4) mapping analyses under 10 N.

3.7. Tribological Behavior

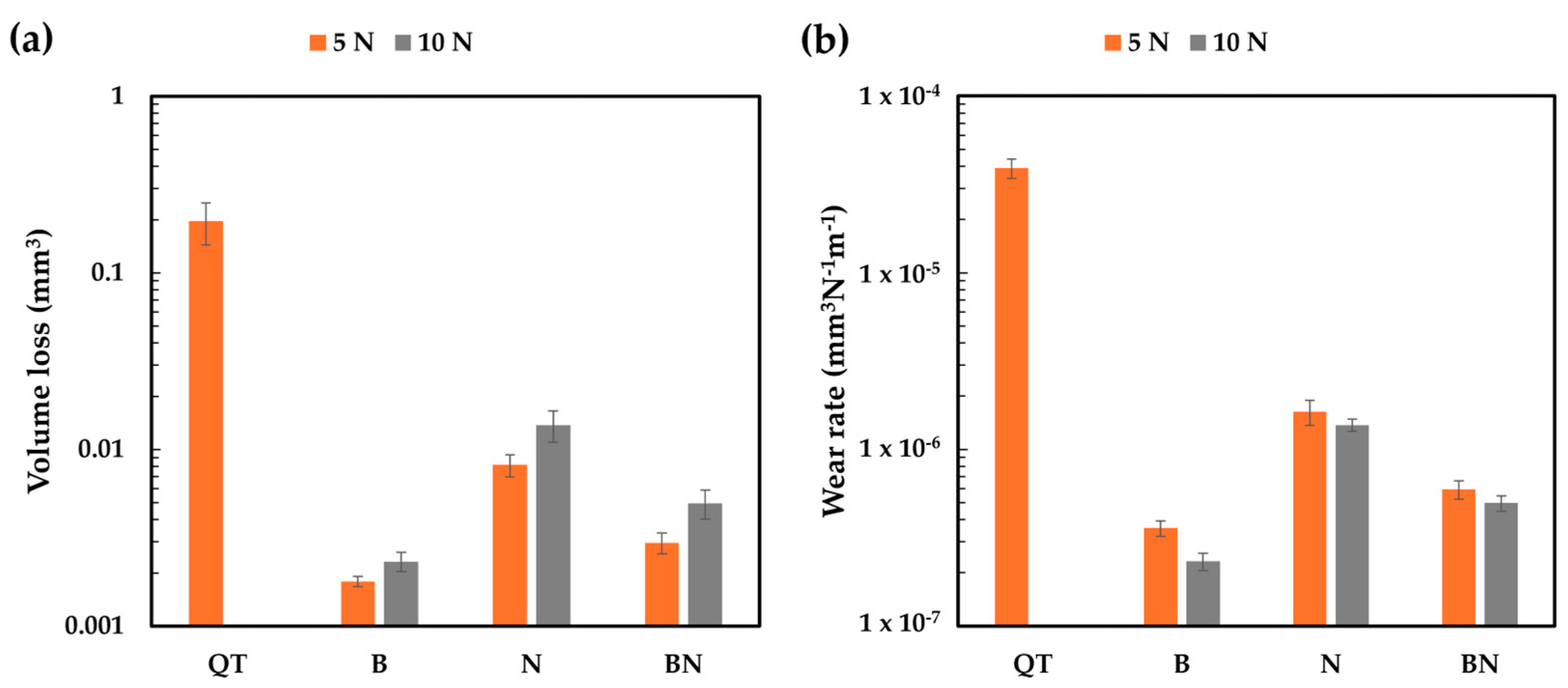

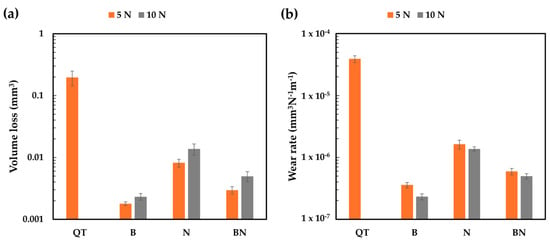

Figure 14 presents the wear performance of untreated samples and thermochemical coatings B, N, and BN under 5 N and 10 N loads in terms of volume loss (a) and wear rate (b) corresponding to each treatment. The sample QT under 5 N load exhibited the highest wear volume (0.1960 mm3) and rate (3.92 × 10−5 mm3N−1m−1) (Figure 14a,b). This low wear resistance is consistent with the untreated martensitic microstructure described by Brühl et al. [17]. Untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel was not tribologically tested under a 10 N load. The boriding condition yielded excellent performance at 5 N and 10 N, with wear volumes of 0.0017 mm3 and 0.0023 mm3 and wear rates of 3.58 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1 and 2.31 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1, respectively. Good wear performance can be obtained with a low wear rate under applied loads of both 5 N and 10 N. This result can be explained by the mechanical properties presenting the highest hardness and elastic modulus. In contrast, the nitriding treatment showed a wear increase under 5 N and 10 N, with wear volumes of 0.0081 mm3 and 0.0137 mm3 and wear rates of 1.63 × 10−6 mm3N−1m−1 and 1.37 × 10−6 mm3N−1m−1, respectively. This wear trend could be related to the reduced mechanical properties shown in Table 3 compared to those of the borided and boronitrided coatings. The boronitriding treatment exhibited balanced wear performance between the borided and nitrided samples, with wear volumes of 0.0029 mm3 and 0.0049 mm3 and wear rates of 5.92 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1 and 4.96 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1, respectively, between the borided and nitrided samples. The boronitriding wear trend demonstrated a synergistic balance, combining high wear resistance with reduced friction, lacking brittle fractures in the coating layer, confirming that a duplex coating treatment is an effective strategy for improving the surface performance of AISI 420 ESR.

Figure 14.

Volume loss (a) and wear rate (b) for QT and thermochemical coatings under 5 N and 10 N loads.

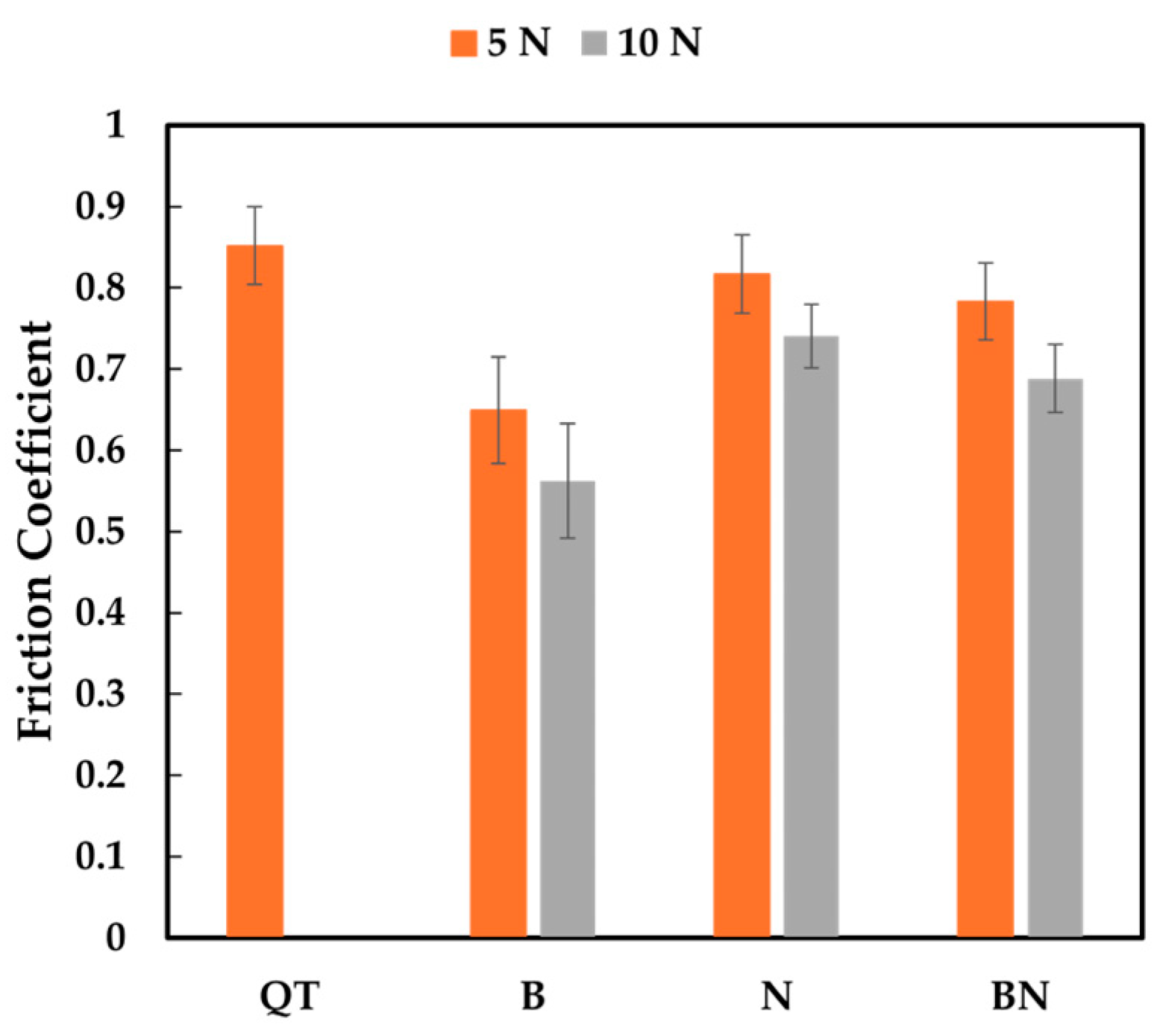

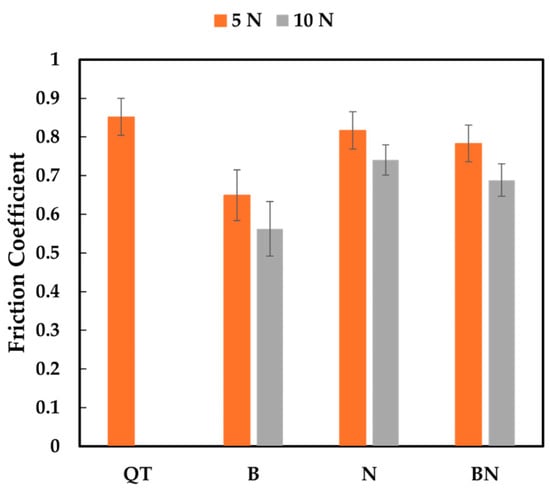

The average friction coefficient behavior of the untreated and treated borided, nitrided, and boronitrided samples under 5 N and 10 N loads is shown in Figure 15. The quenched and tempered conditions showed the highest coefficient of friction, ~0.85. This result is in good agreement with Dalibon et al. [9] for untreated 420 stainless steel against alumina under dry-sliding conditions. Untreated QT 420 ESR stainless steel was not tribologically tested with a 10 N load. The borided surface samples tested under 5 N and 10 N loads exhibited the lowest average coefficient of friction, ~0.65 and ~0.56, respectively. This result can be attributed to the high surface hardness and low plastic deformation of the boride layer. Similar trends were reported by Ortiz-Domínguez et al. [20]. The nitride surface sample achieved an average coefficient of friction of ~0.81 and ~0.74, respectively, under 5 N and 10 N loads. These results are comparable with observations by Dalibon et al. [9], Xi et al. [10], and Sun et al. [19]. Finally, the boronitrided sample yielded an average coefficient of friction of ~0.78 and ~0.67, respectively, under 5 N and 10 N loads.

Figure 15.

Mean friction coefficient for QT and thermochemical coatings under 5 N and 10 N loads.

The findings of the present study show that surface-dominant treatments such as sequential boriding and nitriding promote significant tribological improvements through the formation of hard compound layers, indicating a different but complementary pathway for wear resistance enhancement. Similar trends related to heat treatment, mechanical properties, and tribological behavior have been reported for tool steels subjected to conventional quenching and tempering treatments [51]. In particular, this study demonstrated that variations in hardness and elastic modulus induced by QT directly affect the friction coefficient and wear rate, highlighting the dominant role of microstructural strengthening mechanisms. A similar trend is observable between the wear and friction coefficient as the load increases (Figure 12 and Figure 13). This result could be because third-body particles produced with higher normal loads may generate more wear debris, thereby reducing friction by acting as a spacer between the sliding surfaces and rolling or sliding under a lateral force. Diomidis et al. [52] demonstrated that the evolution of the friction coefficient is strongly dependent on third-body properties and that wear is controlled by the applied load and thus the real contact area within the wear track. These findings suggest that the dual boronitriding surface treatment process is consistent with a balanced mechanical and tribological response in terms of material performance and durability.

4. Conclusions

AISI 420 stainless steel was quenched and tempered prior to gas nitriding and pack boriding. According to the characterization of the microstructure, mechanical properties, and tribological behavior, the following conclusions can be drawn.

- The nitrided layers were composed mainly of ε-Fe3N and γ′-Fe4N phases, while the borided layers consisted of FeB and Fe2B phases. The boronitrided layers exhibited a layered structure combining boride-rich outer zones and nitride diffusion layers. Cr2B was also detected in the duplex coating.

- Rockwell-C indentation revealed poor adhesion in the borided samples due to cracking, whereas boronitriding conditions exhibited strong adhesion with no spallation.

- The hardness after quenching and tempering was 304.8 HV0.05. The borided samples showed the highest surface hardness at 1487.6 HV0.05; the nitrided samples presented 1114.1 HV0.05; and the boronitrided samples exhibited 1357.1 HV0.05. Compared with the QT sample, the hardness increased 4.8 times with boriding, 3.6 times with nitriding, and 4.4 times with boronitriding.

- The samples treated with gas nitriding, package boriding, and boronitriding showed higher microhardness, elastic modulus, and hardness values compared to those of the QT samples. The boronitrided layer exhibited balanced hardness and ductility.

- Wear testing showed the B samples exhibited the lowest volume loss and wear rate of 0.0017 mm3 and 3.58 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1 under loads of 5 N and 10 N, respectively. The N samples exhibited a volume loss of 0.0081 mm3 and a wear rate of 1.63 × 10−6 mm3N−1m−1 under loads of 5 N and 10 N, respectively. The BN samples showed volume loss of 0.0029 mm3 and a wear rate of 5.92 × 10−7 mm3N−1m−1 under loads of 5 N and 10 N, respectively. Compared with the QT (3.92 × 10−5 mm3N−1m−1), the wear rate decreased by 99.1% for boriding, 95.8% for nitriding, and 98.5% for boronitriding.

- Compared with the QT sample, the coefficient of friction exhibited a decreasing trend under thermochemical treatments. The lowest value was obtained from the borided samples (23% lower than the QT condition), followed by the boronitrided (11% lower) and nitrided samples (4.7% lower).

- Although the boriding treatment demonstrated the highest hardness and wear resistance, the indentation revealed brittle fractures and spallation with poor adhesion. The boronitrided coating demonstrated a synergistic balance by combining high wear resistance with improved adhesion and lower friction, confirming that the duplex coating is an effective strategy for improving the surface performance of AISI 420 ESR components.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.V., R.C.E. and M.W.; methodology, M.W., V.L.L., S.B., H.M.H.G., J.C.D.G., R.M.A., M.A.C.-G. and P.M.G.; software, M.A.V.; validation, M.A.V., R.C.E. and M.W.; formal analysis, M.A.V., P.M.G. and M.W.; investigation, J.A.O.; resources, M.W., H.M.H.G., J.C.D.G., R.M.A., M.A.C.-G., V.L.L., S.B. and P.M.G.; data curation, M.A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.V. and V.L.L.; writing—review and editing, J.A.O.; visualization, M.A.V.; supervision, M.A.V., R.C.E. and V.L.L.; project administration, R.C.E.; funding acquisition, M.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Secihti).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Juan Carlos Díaz Guillén was employed by the company Innovabienestar de México, SAPI de CV. Author Héctor Manuel Hernández García was employed by the company Innovabienestar de México, SAPI de CV. The remaining authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Outokumpu Stainless AB. Handbook of Stainless Steel; Outokumpu: Avesta, Sweden, 2013; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Isfahany, A.N.; Saghafian, H.; Borhani, G. The effect of heat treatment on mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of AISI420 martensitic stainless steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 3931–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayali, Y.; Taktak, S. Characterization and Rockwell-C adhesion properties of chromium-based borided steels. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juiña, L.C.; Dávalos, E.J.; Landazurí, D.S.; Guaño, S.E.; Moreno, N.V. Roughness analysis of a concave surface as a function of machining parameters and strategies for AISI 420 steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Khazaei, B.; Mollaahmadi, A. Rapid tempering of martensitic stainless steel AISI420: Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelária, A.F.; Pinedo, C.E. Influence of the heat treatment on the corrosion resistance of the martensitic stainless steel type AISI 420. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2003, 22, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiczek, T.; Stachowiak, A.; Ulbrich, D.; Bartkowski, D.; Bartkowska, A.; Bieńczak, A. Tribocorrosion behavior of 420 martensitic stainless steel in extracts of allium cepa. Wear 2024, 558–559, 205576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Sun, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, H.; Ding, Z.; Chen, D.; Cui, G. Gas Nitriding of AISI 420 Martensitic Stainless Steel during the Incubation Period of CrN Precipitation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 10150–10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibon, E.; Charadia, R.; Cabo, A.; Brühl, S.P. Short Time Ion Nitriding of AISI 420 Martensitic Stainless Steel to Improve Wear and Corrosion Resistance. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20190415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.T.; Liu, D.X.; Han, D.; Han, Z.F. Improvement of mechanical properties of martensitic stainless steel by plasma nitriding at low temperature. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2008, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, A.; Tek, Z.; Öztarhan, A.; Artunç, N. A comparative study of single and duplex treatment of martensitic AISI 420 stainless steel using plasma nitriding and plasma nitriding-plus-nitrogen ion implantation techniques. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2007, 201, 8127–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Liu, G.Q.; Wang, L.; Xu, B.F. Research on new rapid and deep plasma nitriding techniques of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel. Vacuum 2010, 84, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wang, L. Mechanism and properties of plasma nitriding AISI 420 stainless steel at low temperature and anodic (ground) potential. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 403, 126390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, C.E.; Monteiro, W.A. On the kinetics of plasma nitriding a martensitic stainless steel type AISI 420. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2004, 179, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y.; Xiu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, B. Wear and corrosion properties of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel treated by active screen plasma nitriding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 329, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Liu, D.; Han, D. Improvement of corrosion and wear resistances of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel using plasma nitriding at low temperature. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühl, S.P.; Charadia, R.; Sanchez, C.; Staia, M.H. Wear behavior of plasma nitrided AISI 420 stainless steel. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 99, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menthe, E.; Rie, K.-T.; Schultze, J.W.; Simson, S. Structure and properties of plasma-nitrided stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1995, 74–75, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, J.; Xie, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.P.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.H.; Wang, Q.M. Properties of rapid arc discharge plasma nitriding of AISI 420 martensitic stainless: Effect of nitriding temperatures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 4804–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Domínguez, M.; Morales-Robles, Á.J.; Gómez-Vargas, O.A.; de Jesús Cruz-Victoria, T. Analysis of Diffusion Coefficients of Iron Monoboride and Diiron Boride Coating Formed on the Surface of AISI 420 Steel by Two Different Models: Experiments and Modelling. Materials 2023, 16, 4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, I. Investigation of Tribological Properties and Characterization of Borided AISI 420 and AISI 5120 Steels. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2014, 67, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintaş, A.; Sarigün, Y.; Çavdar, U. Effect of Ekabor 2 powder on the mechanical properties of pure iron powder metal compacts. Rev. Metal. 2016, 52, 3073. [Google Scholar]

- Juijerm, P.; Angkurarach, L.; Naemchanthara, P. Direct current field enhanced boronizing of stainless steels and predictive performance of diffusion kinetics, deep neural network, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system on boride layer thickness. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 16507–16522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barut, N.; Yavuz, D.; Kayali, Y. Investigation of the kinetics of borided AISI 420 and AISI 5140 steels. J. Sci. Eng. 2014, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, T.; Ay, I. Investigation of mechanical, kinetic and corrosion properties of borided AISI 304, AISI 420 and AISI 430. Surf. Eng. 2021, 37, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayali, Y. Investigation of the diffusion kinetics of borided stainless steels. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2013, 114, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, O.; Demirsöz, R.; Özdemir, M.T.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Gupta, M.K.; Günay, M.; Ross, N.S.; Nag, A. Investigating the erosive wear characteristics of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel after surface hardening by boriding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Li, J.; Mao, W.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Ma, X. Improving the wear and corrosion resistance of martensitic stainless steel by paste boriding treatment. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.T.; Shao, L.J.; Lou, N.; Shen, Z.K.; Piao, Z.Y.; Ding, C.; Zhou, Z.Y. Improvements in surface integrity, corrosion and wear resistances of TA2 titanium alloy via cool-assisted ball burnishing. Tribol. Int. 2026, 216, 111566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, F.; Ma, K.; Cheng, Y. Research status of tribological properties optimization of high-entropy alloys: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 4257–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulka, M. Trends in thermochemical techniques of boriding. In Current Trends in Boriding, Engineering Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Keddam, M.; Orihel, P.; Jurci, P.; Kusy, M. Characterization of Boride Layers on S235 Steel and Calculation of Activation Energy Using Taylor Expansion Model. Coatings 2025, 15, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihel, P.; Keddam, M.; Jurči, P. Growth, characterization, and kinetic modeling of diiron boride layers on W302 steel. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 40, 3351–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joritz, D.; Edenhofer, B. Geregelte Gasnitrierung und Gasnitrocarburierung in vollautomatischen Retortenöfen. HTM J. Heat Treat. Mater. 2005, 60, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M. Das Reaktionssystem beim Gasnitrieren von Eisenwerkstoffen. HTM J. Heat Treat. Mater. 1981, 36, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6507-1:2018; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Ortiz-Domínguez, M.; Keddam, M. Solid Boronizing of AISI 420 Steel: Characterizations and Kinetics Modelling. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2021, 59, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckart, W.; Forlerer, E.; Iurman, L. Delayed cracking in plasma nitriding of AISI 420 stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 202, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulutan, M.; Yildirim, M.M.; Çelik, O.N.; Buytoz, S. Tribological Properties of Borided AISI 4140 Steel with the Powder Pack-Boriding Method. Tribol. Lett. 2010, 38, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lenda, O.; Tara, A.; Lazar, F.; Jbara, O.; Hadjadj, A.; Saad, E. Structural and Mechanical Characteristics of AISI 420 Stainless Steel After Annealing. Strength Mater. 2020, 52, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-León, R.A.; Martinez-Trinidad, J.; Campos-Silva, I.; Wong-Angel, W. Mechanical characterization of the AISI 316L alloy exposed to boriding process. Dyna 2020, 87, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xue, W.; Guo, S.; Liu, H.-X.; Huang, S.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Improving cavitation erosion resistance of laser-Clad Fe–Mn–Si–Cr–Ni shape memory alloy coatings through B alloying. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 7320–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Qian, B.; Zhu, Z.; Zou, S.; Li, G.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, W. A mechanical strong yet ductile CoCrNi/Cr2B composite enabled by in-situ formed borides during laser powder bed fusion. Compos. B Eng. 2024, 278, 111428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrinato, M.D.; Sgarbi Rossino, L.; Kliauga, A.M.; Florêncio, O. Mechanical Properties of Indentation in Plasma Nitrided and Nitrocarburized Austenitic Stainless Steel AISI 321. Defect Diffus. Forum 2023, 429, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.K.; Kang, J.J.; Ma, G.Z.; Zhu, L.N.; Da, Q.; Liu, B.; Li, R.F. Annealing treatment’s impact on the microstructure and mechanical properties of HVOF-sprayed highentropy alloy coatings with AlxCoCrFeNi composition (x = 0.4, 0.7, 1.0). J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI 3198:1992-08; Beschichten von Werkzeugen der Kaltmassivumformung; CVD- und PVD-Verfahren (Coating (CVD, PVD) of Cold Forging Tools). VDI—Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1992.

- Guler, K.O.; Uyulgan, B.; Hizli, B.; Ince, U. Effect of boriding on wear and fatigue life of WC-Co die inserts in cold forming. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 179, 109762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera Espinoza, R.; Alvarez Vera, M.; Wettlaufer, M.; Kerl, M.; Barth, S.; Moreno Garibaldi, P.; Díaz Guillen, J.C.; Hernández García, H.M.; Muñoz Arroyo, R.; Ortega, J.A. Study on the Tribological Properties of DIN 16MnCr5 Steel after Duplex Gas-Nitriding and Pack Boriding. Materials 2024, 17, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Guillén, J.C.; Naeem, M.; Acevedo-Dávila, J.L.; Hdz-García, H.M.; Iqbal, J.; Jan Mayen, M.A.K. Improved Mechanical Properties, Wear and Corrosion Resistance of 316L Steel by Homogeneous Chromium Nitride Layer Synthesis Using Plasma Nitriding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escherová, J.; Krbata, M.; Kohutiar, M.; Barényi, I.; Chochlíková, H.; Eckert, M.; Jus, M.; Majerský, J.; Janík, R.; Dubcová, P. The Influence of Q & T Heat Treatment on the Change of Tribological Properties of Powder Tool Steels ASP2017, ASP2055 and Their Comparison with Steel X153CrMoV12. Materials 2024, 17, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomidis, N.; Mischler, S. Third body effects on friction and wear during fretting of steel contacts. Tribol. Int. 2010, 44, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.