Abstract

Erosion of the leading edge is one of the most severe forms of damage in wind turbine blades, particularly in offshore wind farms. This degradation, mainly caused by rain, sand, and airborne particles through droplet impingement wear, significantly decreases blade aerodynamic efficiency and power output. Since blades, typically made of fiber-reinforced polymer composites, are the most expensive components of a turbine, developing protective coatings is essential. In this study, polyurethane (PU) composite coatings reinforced with titanium dioxide (TiO2) particles were added on glass fiber substrates by spray coating. The incorporation of TiO2 improved the mechanical and electrochemical performance of the PU coatings. FTIR and XRD confirmed that low TiO2 loadings (1 and 3 wt%) were well dispersed within the PU matrix due to hydrogen bonding between TiO2 –OH groups and PU –NH groups. The PU/TiO2 3% coating exhibited ~61% lower corrosion current density (I_corr) compared to neat PU, indicating superior corrosion resistance. Furthermore, uniform TiO2 dispersion resulted in statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05) in hardness, yield strength, elastic modulus, and adhesion strength. Overall, the PU/TiO2 coatings, particularly at 3 wt% loading, show strong potential as protective materials for wind turbine blades, given their enhanced mechanical integrity and corrosion resistance.

1. Introduction

The generation of wind energy has become one of the essential strategies to mitigate the rise in global atmospheric temperatures. In 2024, the sector achieved a record milestone, with 117 GW of new wind power capacity added worldwide, giving the total established capacity to 1136 GW—an 11% increase compared to the earlier year. To reach this level of deployment, wind turbines have significantly increased in size, with blades extending to hundreds of meters in length [1]. Likewise, wind farms are increasingly being installed in locations with severe weather conditions, such as offshore sites, monsoon regions, and the North Sea. These trends have a common consequence: they make turbine maintenance both more difficult and more costly, while simultaneously increasing the frequency of required interventions due to the combined effects of mechanical and environmental stresses [2,3].

Leading edge erosion (LEE) of wind turbine blades is one of the most frequently observed and costly damage mechanisms. Leading edge erosion (LEE) is caused by multiple factors. One of the most critical occurs when the wind carries rain droplets, sand, hail, insects, or dust; these particles strike the blade surface at very high relative velocities (>80–100 m/s). The repeated impacts gradually remove small amounts of material, resulting in progressive erosion. Another important factor is environmental exposure. Offshore turbines, for example, are affected by saline environments and high moisture levels, while UV radiation and temperature cycles further degrade the coating, making the leading edge more vulnerable to damage [4,5,6]. On the word of Mishnaevsky Jr. et al., surface erosion is the only damage mechanism typically detected through the first year after installation and remains the most critical within the first five years of service. LEE not only compromises the structural integrity of the blade but also leads to significant annual energy production (AEP) losses. When erosion occurs, the blade surface topography is altered, increasing surface roughness and inducing turbulence at the leading edge. This turbulence promotes premature flow separation, which reduces the pressure distribution over the blade surface and causes detachment of the airflow. As a consequence, aerodynamic lift decreases, drag increases, and the overall efficiency of the wind turbine deteriorates [7,8,9,10,11].

Composite coatings are an interactive mixture of inorganic and organic constituents. The easiest method to create these coatings is by incorporating inorganic particles into an organic amorphous matrix. The organic phase imparts elasticity to the coating, whereas the inorganic phase provides hardness and durability. Such composite coatings can absorb, and diffuse impact energy generated by continual strikes of particulate matter, producing strong erosion resistance [12,13,14,15].

Polyurethane (PU) exhibits excellent elasticity, strong adhesion, toughness, chemical resistance, and abrasion resistance. However, the addition of particles such as carbides, nitrides, and oxides can act as support for materials to further improve its mechanical properties. Johansen et al. studied PU coatings reinforced with graphene–silica hybrids and graphene, analyzed for anti-erosion performance utilizing the single point impact fatigue testing (SPIFT). Their results showed that PU coatings protected with hybrid graphene and sol–gel nanoparticles provided superior erosion protection, extending service life up to 13 times longer compared with neat PU [16,17].

Similarly, unsaturated polyester resin was handled as the matrix, with methyl ethyl ketone peroxide (MEKP) as the hardener. The functionalized CNF coatings exhibited great potential for wind turbine blade applications due to their excellent impact–friction resistance, damping properties, and super hydrophobicity [18]. Recently, Pathak developed using a straightforward spray coating technique ceramic oxide-reinforced water-based PU coatings protecting wind turbine blades from solid particles. Three distinct concentrations (2, 5, and 10 wt%) of Al2O3, ZrO2, and CeO2 nanoparticles produced using a solution combustion synthesis method were employed. When compared to the neat PU coating, the typical erosion rates of PU–ceramic oxide coatings were 20–40% lower [19].

TiO2 particles have been widely employed in polymeric matrices for optical, photo-catalytic, and UV-protection applications, as well as in wastewater treatment, owing to their chemical stability, optical properties, UV absorption capacity, and low cost. Che and Wu concluded that increasing TiO2 content in PU enhances the wear resistance of the composite material [20,21,22,23,24].

This paper focuses on studying the effect of TiO2 particle concentration on the mechanical and anticorrosion properties of a PU matrix. Protective performance was further investigated through complementary tests, including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), corrosion tests, hardness tests, tensile tests, and pull-off adhesion tests.

2. Materials and Techniques

2.1. Substrate

Fiberglass substrates measuring 3 × 3 × 1 cm were prepared. To achieve a uniform surface roughness, one face was polished using a 50-grit sandpaper. To remove residual particles, the trials were placed in an ultrasonic bath (CS Scientific) operating at a frequency of 40 Khz for 30 min, and subsequently, the liquid residue was eliminated by evaporation in an oven for 30 min at 30 °C. To increase the surface energy, plasma treatment was applied for 15 s, as determined from previous experiments [25].

2.2. Titanium Oxide

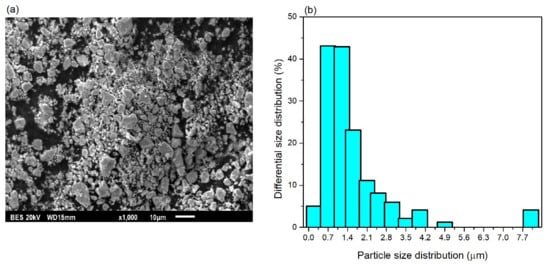

The TiO2 particles powder consisted of irregular particles with predominantly sizes ranging from 0.2 to 4.1 µm, as confirmed by SEM imaging and the particle-size histogram (see Figure 1a,b). A small fraction of larger particles (8 µm) was also observed, although these were not representative of main contribution. The particles exhibited high-purity (~99) and anatase crystalline structure and were supplied by LJQMETAL Element Store.

Figure 1.

SEM morphology (a) and particle size histogram (b) of TiO2 particles.

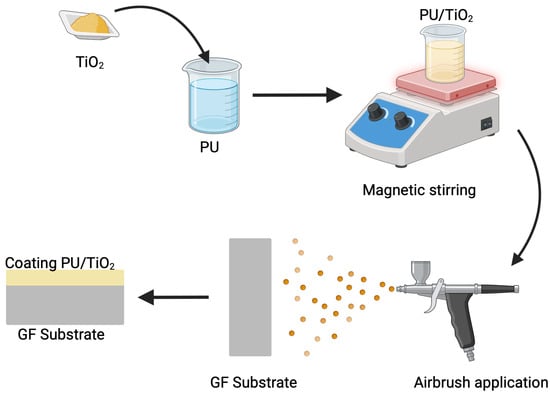

2.3. Coating Application

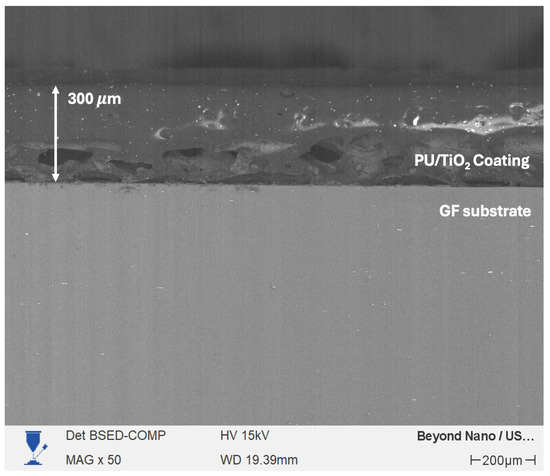

The TiO2 particles (Ps) were incorporated into a water-based polyurethane (PU) resin (Polyform® 3000, Pinturas Comex, Valle de Santiago, Mexico). Gravimetric drying confirmed that the polyurethane (PU) resin contains approximately 40 wt% non-volatile solids, with typical viscosity of 80–120 KU and a density of 1.00–1.05 g/mL, consistent with aliphatic PU dispersions. TiO2 particles was added at nominal concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 wt% relative to the as-received polyurethane (PU) resin, corresponding to the formulations PU/TiO2 1%, PU/TiO2 3%, and PU/TiO2 5%, respectively. The mixture was placed in a beaker, and the particles were dispersed by magnetic stirring for 5 h. The PU/TiO2 coatings were used onto the previously prepared substrates utilizing an airbrush gun at 30 psi (see Figure 2). The application time was 60 s, which allowed for an approximate thickness of 300 µm with a standard deviation of 34 µm (11%), which is typical for films applied by airbrush and indicates acceptable thickness homogeneity (see Figure 1). Additionally, PU/TiO2 coatings were sprayed onto glass Petri dishes to produce free-standing films for mechanical analyses. These films were prepared using the same spraying conditions described for the fiber-based substrates.

Figure 2.

Methodology for the preparation of PU/TiO2 coating films.

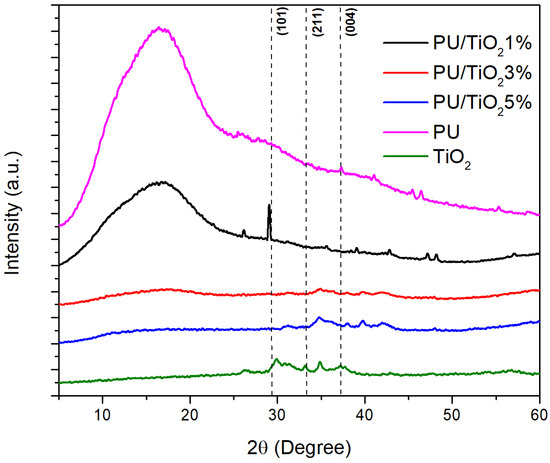

The diffraction patterns of the distinct concentrations of PU/TiO2 coatings were obtained on an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku Miniflex DMAX 2200, Rigaku Analytical Devices, Wilmington, MA, USA). The coating layer was irradiated using Cu–Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) and a graphite monochromator with 2θ range of 5–60°. A grazing incidence angle of 1° was used (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional SEM image showing the representative thickness of the PU/TiO2 coating.

FTIR spectra were obtained employing a Bruker IFS 125hr spectrometer to confirm the dispersion of TiO2 particles within the PU matrix.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed to evaluate the corrosion resistance of PU/TiO2 using an ACM Instruments potentiostat/galvanostat in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. A three-electrode configuration was employed, with PU/TiO2 as the working electrode, platinum as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference. The EIS tests were conducted over a frequency range of 105 to 10−2 Hz with an AC perturbation amplitude of 10 mV. All measurements were carried out in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at room temperature. The data was subsequently evaluated with ZView 4 software, version 4.0.h.

Pull-off tests were used to estimate the adhesion of the different coatings applied onto the fiberglass substrates. The tests were performed according to ASTM D4541 standards [26], using a PosiTest AT-M, ABQ Industrial, The woodland, TX, USA.

The hardness of the different PU/TiO2 coatings was determined using a Matsuzawa microhardness tester. Measurements were performed using a load of 10 g with a penetration time of 20 s. Five indentations were made on each coating to obtain an average value.

Stress–strain curves were recorded using a Linkam TST350 testing system, Linkan Scientific Instruments, Salfords, UK, with a crosshead speed of 100 mm/s and an applied load of 20 N. The experiments were conducted in accordance with ASTM D882-10.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD Analysis

As shown in Figure 4, polyurethane (PU) shows an amorphous behavior, evidenced by the manifestation of a broad hump (10° < 2θ < 25°), which confirms its low degree of crystallinity [27]. However, when TiO2 particles were incorporated into the formulation, several intense peaks appeared at 2θ = 28° (101) and 38° (004), corresponding to the anatase phase of TiO2. The peak at 2θ = 33° (211) is also attributed to TiO2 diffraction [27].

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of TiO2, PU, and distinct concentrations of PU/TiO2 coatings.

In contrast, when comparing the XRD patterns of PU/TiO2 coatings, the effect of low TiO2 concentrations can be observed. The PU/TiO2 1% coating exhibits weaker TiO2 peaks superimposed on the amorphous PU background yet still displays sharp reflections that indicate an increase in crystallinity [27,28]. This may reflect a better dispersion of TiO2 particles within the polymer matrix and stronger interactions among the interfaces. This behavior can be attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the –NH groups of the PU and the oxygen atoms of the TiO2 surface [29].

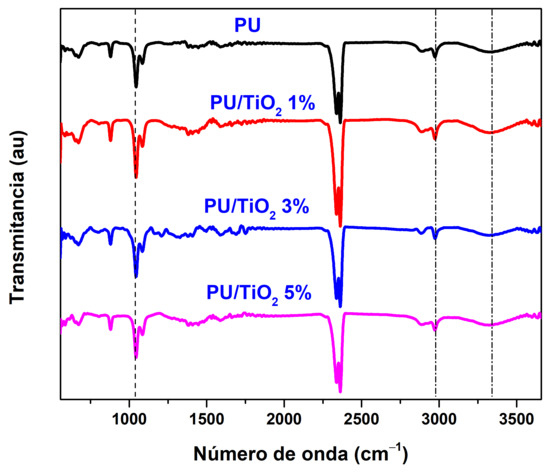

3.2. FTIR Spectroscopy for PU/TiO2

The structural modifications of polyurethane (PU) induced by the incorporation of titanium dioxide (TiO2) were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Figure 5 displays the infrared spectra in the range of 550–3600 cm−1 for the different coatings. The characteristic peaks of PU appear at 3300, 2978, 2364, and 1049 cm−1, corresponding to ν(N–H), ν(C–H), ν(C–H), and ν(C–O), respectively [30,31,32].

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra for distinct concentrations of PU/TiO2.

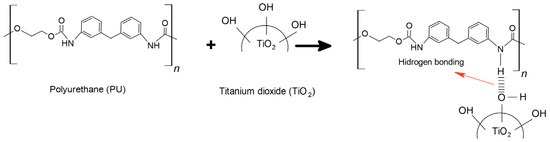

Hydrogen bonding is the main type of interaction between PU and TiO2: (1) in polyurethane, the N–H groups (proton donors) and the oxygen atoms in the C=O and ester groups (proton acceptors) form hydrogen bonds; (2) TiO2 particles play an important role in hydrogen bond formation due to hydroxyl groups on their surface interacting with the N–H groups of the polyurethane (see Figure 6) [29].

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of hydrogen bonding interactions between PU and TiO2 particles.

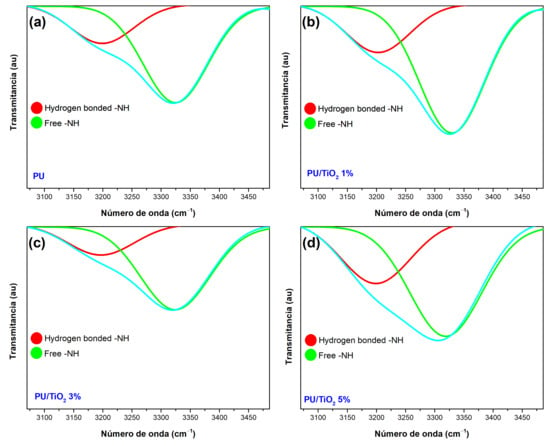

The N–H stretching band is deconvoluted into two peaks at 3325 cm−1 and 3198 cm−1, attributed to free N–H and hydrogen-bonded N–H groups, respectively (Figure 7). Table 1 presents the ratio between hydrogen-bonded and free N–H groups.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra for distinct concentrations of PU/TiO2 coatings. The zoom views of -NH stretching region. (a) for PU, (b) for PU/TiO2 1%, (c) for PU/TiO2 3%, and for (d) PU/TiO2 5%.

Table 1.

Relationship between hydrogen-bonded -NH and free -NH groups.

The neat PU exhibits a high fraction of hydrogen-bonded N–H (~58.8%) due to intrinsic interactions between N–H and C=O groups within the polymer chains (see Figure 7a). When 1 wt% TiO2 is incorporated, the fraction of hydrogen-bonded N-H decreases to ~40.0% (see Figure 7b). At this loading, the TiO2 particles provide only a limited number of surfaces –OH sites available to form hydrogen bonds, and they may partially disrupt existing N–H···C=O hydrogen bonds in the PU matrix.

A markedly different behavior is observed at 3% wt% TiO2, where the hydrogen-bonded N-H fraction increases to ~64.7% (see Figure 7c). This enhancement is attributed to improved particle dispersion and a large effective TiO2 surface area. Which introduces a greater density of -OH groups capable of forming hydrogen bonds with N-H groups in the PU. However, at 5 wt%, the bonded N-H fraction decreases again to ~53.6% (see Figure 7d). This reduction is consistent with the onset of TiO2 agglomeration, which lowers the accessible surface area and limits the number of active -OH sites available to interact with N-H groups. Consequently, the hydrogen-bonding equilibrium shifts back toward lower interfacial interactions [33].

In conclusion, the PU/TiO2 3% coating exhibits the highest hydrogen-bonded N–H fraction (~64.7%), attributed to enhanced interactions between the –OH groups on the TiO2 surface and the N–H groups in the PU. These results highlight the central role of hydrogen bonding in dictating dispersion quality, polymer chain mobility, and ultimately the microstructural cohesion of the PU/TiO2 coatings [34,35].

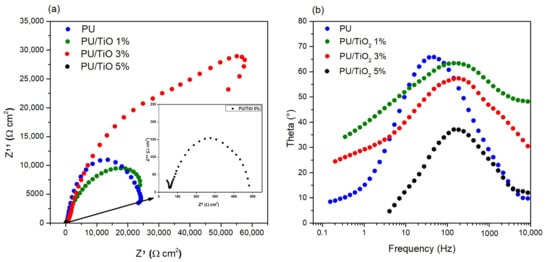

3.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) of PU/TiO2 Coatings

EIS was performed on magnesium substrates coated with polyurethane (PU) containing TiO2 particles at 0 wt%, 1 wt%, 3 wt%, and 5 wt% and evaluated in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for comparative analysis. A 3.5 wt% NaCl solution was used to simulate seawater, as this concentration represents peak corrosiveness for many materials and provides a standardized, reproducible testing environment. Furthermore, 3.5 wt% NaCl is widely adopted because it approximates the most aggressive conditions, making it ideal for simulating offshore turbine environments [30]. The Nyquist plots obtained from EIS are presented in Figure 8a. The composite coating with 3 wt% TiO2 exhibited higher coating resistance values than those with 0, 1, and 5 wt% TiO2, suggesting superior barrier performance due to its higher impedance and, consequently, lower corrosion rate. In contrast, the PU/TiO2 5% coating displayed a smaller semicircle diameter, indicating lower corrosion resistance, likely caused by microdefects from particle agglomeration, which facilitate electrolyte penetration. The bode phase (see Figure 8b) provides a clear interpretation of the electrochemical response of the coating. All PU/TiO2 coatings present a single, well-defined phase peak, indicating the presence of only one dominant time constant. This behavior is characteristic of a moderately degraded barrier-type polymer coating, where corrosion processes are controlled by dielectric properties rather than diffusion or interfacial reactions [36,37].

Figure 8.

(a) Nyquist impedance spectra and (b) Bode phase plots of PU and PU/TiO2 coatings immersed in 3.5 wt % NaCl.

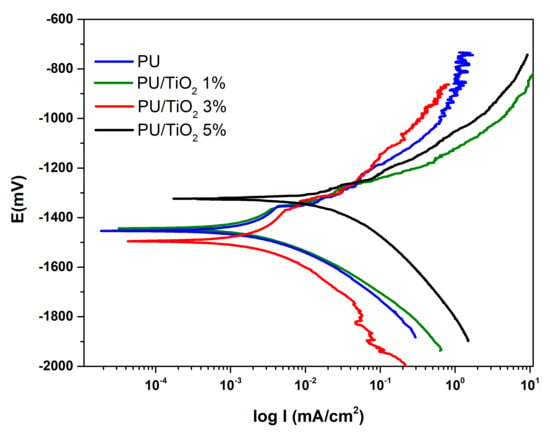

The potentiodynamic polarization curves are given in Figure 9, and the corresponding electrochemical parameters are listed in Table 2. The PU/TiO2 3% coating showed the lowest corrosion current density (Icorr = 8.5 × 10−4 mA/cm2), indicating higher corrosion resistance compared to the other coatings. This improvement is attributed to the uniform dispersion of TiO2 particles within the PU matrix, which results in the formation of a passive and more stable surface that effectively acts as a barrier against corrosive agents [38]. Conversely, in the PU/TiO2 5% coating, the higher particle concentration led to agglomerate formation, creating localized zones of increased corrosive activity (Icorr = 1.7 × 10−2 mA/cm2). As a result, both PU and PU/TiO2 1% coatings exhibited unchanged Icorr values, ranging from 2.2 × 10−3 to 2.0 × 10−3 mA/cm2.

Figure 9.

Potentiodynamic polarization test of TiO2 coatings.

Table 2.

Electrochemical parameter rate of polyurethane coatings containing 0–5 wt% TiO2.

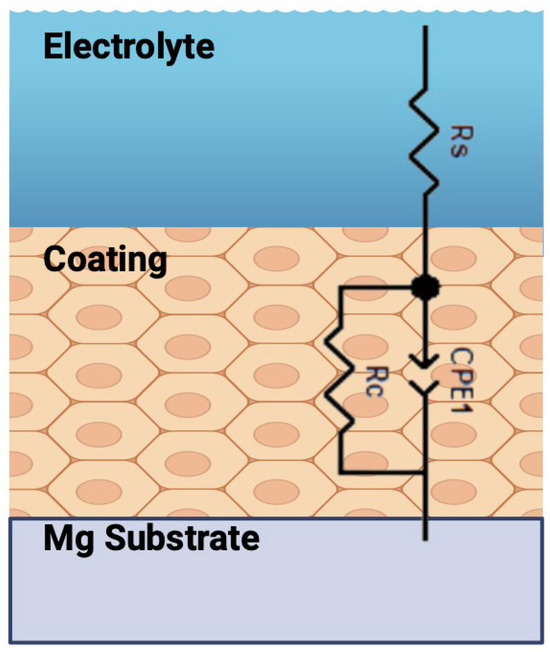

To further explore the corrosion protection mechanism of the PU/TiO2 coatings, the EIS data were fitted utilizing the R(QR) equivalent circuit, as shown in Figure 10. This model es commonly used for intact or moderately degraded barrier-type polymeric coatings that display a single depressed semicircle in the Nyquist plot and a single peak in the bode-phase plot. In our measurements, all coatings exhibited one dominant time constant during the initial immersion period, indicating that the coating film acts primarily as a dielectric barrier. The constant phase element (Q) accounts for the non-linear capacitive behavior caused by coating heterogeneity and particle-polymer interfaces, while Rc corresponds to the ionic resistance of the coating. This circuit consists of Rs, CPE1, and Rac, which correspond to the solution resistance, the constant phase element of the PU/TiO2 coating, and the coating resistance, respectively [39,40]. The fitted parameters are summarized in Table 3. Among the samples, PU/TiO2 3% exhibits the highest Rc, confirming that the incorporation of TiO2 particles significantly improves the corrosion resistance. This improvement can be attributed to a more compact coating structure resulting from a better dispersion of TiO2 nanoparticles. In general, electrolyte penetration into the coating leads to a decrease in Rc and an increase in CPE1. For the PU/TiO2 5% sample, electrolyte diffusion is facilitated, resulting in a very low Rc (4.5 × 101 Ω·cm2) and a high CPE1 (3.23 × 10−5 F·cm−2) [41,42]. In contrast, the PU/TiO2 3% coating exhibits a Rc of 8.8 × 104 Ω·cm2, approximately 240% higher than that of neat PU. Similarly, the PU/TiO2 1% coating shows an increase of ~40% in Rc and ~280% in CPEc compared with neat PU. These results demonstrate that the PU/TiO2 3% coating offers the most effective barrier properties, as electrolyte diffusion into the coating is hindered.

Figure 10.

Equivalent circuit for TiO2 coatings.

Table 3.

The fitting electrochemical values of PU/TiO2 coatings.

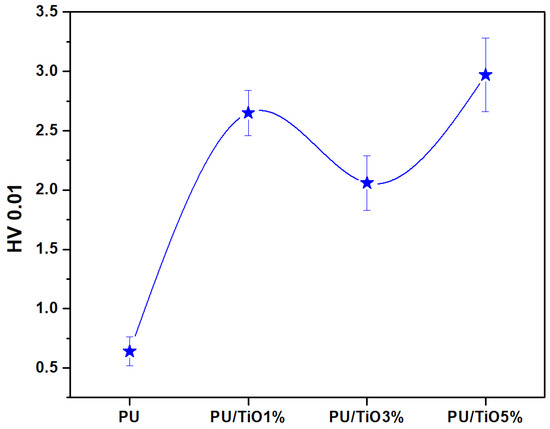

3.4. Hardness Test

The microhardness values of the different coatings are presented in Figure 11. PU/TiO2 1%, PU/TiO2 3%, and PU/TiO2 5% coatings exhibited significantly higher hardness values (2.65, 2.06, and 2.97 HV0.01, respectively) compared to the PU coating, which was notably softer (0.64 HV0.01) [43]. The PU/TiO2 1% coating showed good dispersion of TiO2 particles within the PU matrix, which promoted efficient load transfer and enhanced the mechanical performance of the coating [43]. However, PU/TiO2 3% showed a slight decrease in hardness despite the strong polymer-particle interfacial bonding indicated by FTIR analysis. This behavior can be explained by the formation of isolated micro-scale TiO2 agglomerates, which serve as local stress concentrators and decrease resistance to indentation. The increase in hardness of PU/TiO2 5% coatings is mainly attributed to the rigid TiO2 particle reinforcement, which forms stiff aggregates. Nonetheless, excessive particle loading, as in the PU/TiO2 5% coating, may introduce microdefects and increase the likelihood of crack initiation [44,45].

Figure 11.

Microhardness testing of the PU/TiO2 coatings.

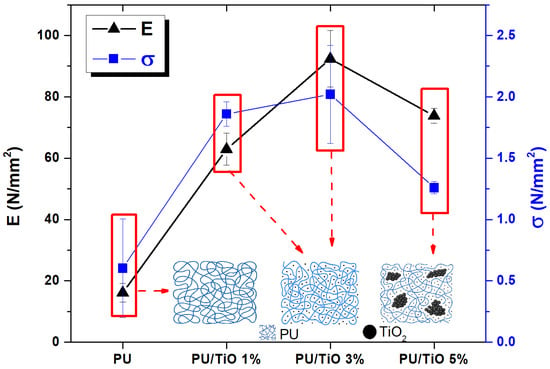

3.5. Tension Test

Figure 12 presents the values of the elastic modulus and yield strength for the different PU/TiO2 coatings. Tensile tests revealed that the incorporation of TiO2 particles increased the yield strength by 310%, 335%, and 210% for PU/TiO2 1%, PU/TiO2 3%, and PU/TiO2 5% films, respectively, compared to the neat PU film [46,47,48]. However, the difference between the PU/TiO2 1% and PU/TiO2 3% coatings was only 8%.

Figure 12.

Tensile tests of the different PU/TiO2 coatings.

The elastic modulus provides an estimate of the stiffness of the PU/TiO2 films. In polymers, crystallinity is associated with higher stiffness; thus, semicrystalline polymers typically exhibit elevated elastic modulus values. The measured values were 16.1, 62.9, 92.4, and 73.8 MPa for PU, PU/TiO2 1%, PU/TiO2 3%, and PU/TiO2 5%, respectively. High TiO2 concentrations (5%) exhibited poor compatibility with the PU matrix, restricting polymer chain mobility. In contrast, at lower concentrations (1% and 3%), TiO2 particles demonstrated good molecular compatibility with the PU, as reflected by the increased elastic modulus and yield strength values [49].

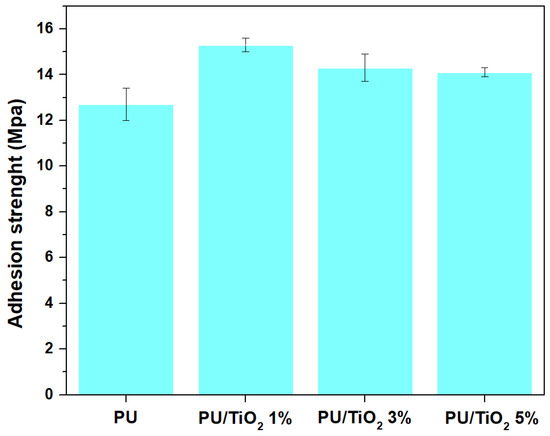

3.6. Adhesion Test

Figure 13 presents the adhesion test findings of polyurethane (PU) coatings with distinct TiO2 concentrations applied on fiberglass substrates. An increase in adhesion strength was observed for all TiO2 containing coatings compared to neat PU. In particular, the PU/TiO2 1% sample exhibited the highest adhesion strength (15.3 MPa), corresponding to a 20.3% improvement relative to neat PU.

Figure 13.

Adhesion tests of PU/TiO2 coatings.

This behavior cannot be attributed solely to better particle dispersion. At low concentrations (1 wt%), the TiO2 particles contribute to moderate surface roughening and enhanced mechanical interlocking, while still maintaining the interaction between the functional groups of the polymer matrix (–NH) and the oxygenated groups on the TiO2 surface, promoting hydrogen bonding and improved mechanical anchoring [29,35]. In contrast, at higher concentrations (3% and 5%), the slight reduction in adhesion strength may be associated with several microstructural effects acting simultaneously: the coating surface becomes less uniform and develops roughness variations that generate localized stress points; the TiO2 particles tend to form small agglomerate, reducing the effective contact between the polyurethane matrix and substrate; the presence of large inclusions introduces rigid defects that act as stress concentrators, facilitating partial debonding [50,51].

In conclusion, the adhesion strength and electrochemical test results revealed a complementary protection mechanism. While the incorporation of TiO2 nanoparticles enhanced adhesion compared to neat PU (from ~12.5 MPa to 14–15 MPa), the optimum corrosion resistance was achieved at 3 wt% TiO2, as supported by the highest impedance values in the Nyquist plots. These findings suggest that adhesion primarily reinforces coating–substrate interfacial stability; however, the barrier performance against electrolyte ingress strongly depends on nanoparticle dispersion and the resulting coating microstructure. At 5 wt%, the IES results indicate that electrolyte transport is still controlled by a single dominant barrier process, as no additional time constant was detected. This demonstrates that the defects present at higher loadings are insufficient to generate a separate electrochemical relaxation mechanism.

PU/TiO2 coatings show significant improvements in mechanical and anticorrosive performance, and this study provides a solid foundation for evaluating their protective behavior. However, long-term environmental durability involves additional degradation mechanisms. Recent studies have demonstrated that different polymeric and hybrid coatings experience different forms of degradation under accelerated UV exposure, salt-spray cycling, and combined UV-saline aging, which more realistically simulate the harsh condition experienced by wind turbine blades [52,53,54]. Other complementary techniques, such as dye ingress crack propagation analysis or periodic EIS monitoring, can also reveal damage that is not captured by short-term test [55]. To extend the present insights toward long-term performance, these accelerated aging protocols may be incorporated in future work. Importantly, they do not replace the present evaluation but rather complement it by simulating extreme service conditions relevant to offshore environments.

4. Conclusions

The polyurethane (PU) coatings modified with TiO2 particles exhibited significant improvements in mechanical and enhanced physicochemical properties, including corrosion resistance, hardness, yield strength, elastic modulus, and adhesion strength. The PU/TiO2 1% and PU/TiO2 3% coatings show an increase of 221% and 165% in hardness, 208% and 234% in yield strength, 291% and 474% in elastic modulus, and 18% and 12% in adhesion strength, respectively, compared with neat PU.

FTIR and XRD analyses evidenced that PU/TiO2 1% and PU/TiO2 3% exhibited better dispersion of TiO2 particles within the PU matrix, which resulted in stronger hydrogen-bonding interactions between TiO2 surface hydroxyl groups and the –NH groups of PU. Furthermore, the PU/TiO2 3% coating significantly reduced the corrosion current density (Icorr) from 2.2 × 10−3 to 8.5 × 10−4 mA/cm2 compared to neat PU, corresponding to an improvement of ~61% in corrosion resistance. The improved impedance values are consistent with a more compact and adherent coating structure, these results indicate that PU/TiO2 1% and PU/TiO2 3% coatings possess enhanced mechanical integrity and barrier performance, making them promising candidates for protective applications in demanding operational environments, including those experienced by wind turbine blades. However, their potential for erosion mitigation must be confirmed through dedicated erosion testing in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and O.X.; methodology, O.X.; software, V.B.-T. and R.C.-A.; validation, V.B.-T. and R.C.-A.; formal analysis, O.G.P. and M.d.P.R.-R.; investigation, O.X. and H.M.; resources, O.X., H.M. and V.B.-T.; data curation, O.G.P., V.B.-T. and R.C.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M., O.X. and M.d.P.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, O.X., H.M. and M.d.P.R.-R.; visualization, M.d.P.R.-R., R.C.-A., V.B.-T. and O.X.; supervision, M.d.P.R.-R., H.M. and O.X.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, O.X. and H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was funded by DGAPA IN-101025 and CONACyT 225991 and 268644.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

O. E. Xosocotla Espejel, with CVU number 801782, shows appreciation to SECIHTI for the doctoral scholarship. M. del P. Rojas Rodriguez, with CVU number 745531, shows appreciation to SECIHTI for the postdoctoral scholarship (project number 6578441). J. Romero-Vergara, H.H. Hinojosa, F. Castillo, and O. Flores are recognized for their specialized assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Cai, A.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W.; Ge, M. Effects of Blade Extension on Power Production and Ultimate Loads of Wind Turbines. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, M.; Siederer, O.; Zekonyte, J.; Barbaros, I.; Wood, R. The effect of temperature on the erosion of polyurethane coatings for wind turbine leading edge protection. Wear 2021, 476, 203720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Sun, H.; Xue, W.; Duan, D.; Chen, G.; Zhou, X.; Sun, J. Preparation of protective coatings for the leading edge of wind turbine blades and investigation of their water droplet erosion behavior. Wear 2024, 558–559, 205568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H. Analysis of the Sand Erosion Effect and Wear Mechanism of Wind Turbine Blade Coating. Energies 2024, 17, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccini, M.; Bautista, L.; Soldi, L.; Escobar, A.M.; Altavilla, M.; Calvet, M.; Domènech, A.; Domínguez, E. Environmentally friendly anticorrosive polymeric coatings. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, P.; Lakshmi, R.V.; Pathak, S.M.; Bonu, V.; Mishnaevsky, L.; Barshilia, H.C. Recent Progress in the Development and Evaluation of Rain and Solid Particle Erosion Resistant Coatings for Leading Edge Protection of Wind Turbine Blades. Polym. Rev. 2023, 64, 639–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.M.; Kumar, V.P.; Bonu, V.; Mishnaevsky, L., Jr.; Lakshmi, R.; Bera, P.; Barshilia, H.C. Enhancing wind turbine blade protection: Solid particle erosion resistant ceramic oxides-reinforced epoxy coatings. Renew. Energy 2024, 238, 121681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelis, A.; Mishnaevsky, L. Coating material loss and surface roughening due to leading edge erosion of wind turbine blades: Probabilistic analysis. Wear 2025, 566–567, 205755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Tempelis, A.; Kuthe, N.; Mahajan, P. Recent developments in the protection of wind turbine blades against leading edge erosion: Materials solutions and predictive modelling. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Q.M.; Sánchez, F.; Mishnaevsky, L.; Young, T.M. Evaluation of offshore wind turbine blades coating thickness effect on leading edge protection system subject to rain erosion. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuthe, N.; Mahajan, P.; Ahmad, S.; Mishnaevsky, L., Jr. Engineered anti-erosion coating for wind turbine blade protection: Computational analysis. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, A.F.; Ramulu, M. The Effectiveness of Graphene and Polyurethane Multilayer Coating on Minimizing the Leading-Edge Erosion of Wind Turbine Blades. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, U.; Teo, J.J.; Chin, C.W.; Yousif, B.F. Review on Erosion Wear Subjected to Different Coating Materials on Leading Edge Protection for Cooling Towers and Wind Turbines. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2025, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Verma, J.; Kumar, D. Mitigation of erosion and corrosion of steel using nano-composite coating: Polyurethane reinforced with SiO2-ZnO core-shell nanoparticles. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Dodla, S.; Gautam, R. Effect of GO, CNTs, and hybrid nanoparticles coated carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composite on erosive wear properties using Taguchi orthogonal array. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budirohmi, A.; Mustari, Y.; Suriani, Y.; Adriana, V.; Natsir, H. The Effect of Concentration of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Their Antibacterial Activity in the Synthesis of Polyurethane Biopolymers. Hydrog. J. Kependidikan Kim. 2023, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Tanasawa, Y.; Shi, J.; Sun, Y. Erosion resistant effects of protective films for wind turbine blades. Adv. Compos. Mater. 2023, 33, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnassir, A.; Albinali, F.; Aljaroudi, F.; Alsaleem, N.; Rehman, S. A comprehensive review of existing erosion protective coatings and practices for wind turbine blade surfaces. FME Trans. 2025, 53, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.M.; Kumar, V.P.; Bonu, V.; Latha, S.; Mishnaevsky, L.; Lakshmi, R.; Bera, P.; Barshilia, H.C. Solid particle erosion studies of ceramic oxides reinforced water-based PU nanocomposite coatings for wind turbine blade protection. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 35788–35798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Palani, G.; Babu, N.K.; Veerasimman, A.P.; Yang, Y.; Shanmugam, V. Solid particle erosion in fibre composites: A review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2024, 44, 2701–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S. Polyurethane-Base Multifunctional Coating for Corrosion Protection of Steel in the Oil & Gas Industry. Master’s Thesis, Qatar University, College of Engineering, Doha, Qatar, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, A.R.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, C.; Mandal, S.K. Erosion Wear Performance of HVOF Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr + 2% TiO2 Coating on SS-409 Using Slurry Jet Erosion Tester. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 16, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, J.; Vasudev, H.; Chohan, J.S.; Akram, S.V. Review on tribo-erosion analysis in Ni, Al2O3, and TiO2 based thermal spray coatings. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3007, 030098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, W.; Du, C.; Kang, Q.; Mao, Z.; Chen, S. A novel noise-reducing and anti-corrosion polyurethane elastomer coating material modified by MXene/porous TiO2. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 48, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xosocotla, O.; Campillo, B.; Martínez, H.; Del Pilar Rodríguez-Rojas, M.; Campos, R.; Bustos-Terrones, V. Modification of Polyurethane/Graphene Oxide with Dielectric Barrier Plasma Treatment for Proper Coating Adhesion on Fiberglass. Coatings 2025, 15, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Varshney, S.; Gupta, M.K. Effect of Fillers on the Performance of Fibre Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2025, 64, 2179–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraraj, S.S.; Xavier, J.R. Electrochemical and mechanical investigation into the effects of polyacrylamide/TiO2 in polyurethane coatings on mild steel structures in chloride media. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 13362–13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liao, W.; Peng, J. Mechanical and electrochemical properties of TiO2 modified polyurethane nanofibers. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, S.; Asefnejad, A.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Jafari, S.H. Improved surface properties in spray-coated PU/TiO2/graphene hybrid nanocomposites through nonsolvent-induced phase separation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 405, 126507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abil, E.; Arefinia, R. The influence of talc particles on corrosion protecting properties of polyurethane coating on carbon steel in 3.5% NaCl solution. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 172, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Afarani, H.T.; Tarashi, Z. Preparation and investigation of the gas separation properties of polyurethane-TiO2 nanocomposite membranes. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 32, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.U.; Khan, M.A.; Waqas, M.; Junaid, T.B.; Siddiqui, W.; Ahmed, A.; Karim, M.R.A. Tape Casting and Characterization of h-BN/PU Composite Coatings for Corrosion Resistance Applications. Digit. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 3, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, D.; Ni, Z.; Qian, S.; Zhao, Y. Improving Corrosion Behavior of Chemically Bonded Phosphate Ceramic Coating Reinforce with GO-TiO2 Hybrid Material. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 121002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, A.K.; Roudini, G.; Barahuie, F.; Masuri, S.U.B. Design of hydrophobic polyurethane–magnetite iron oxide-titanium dioxide nanocomposites for oil-water separation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, M.; Burlanescu, T.; Paraschiv, M.; Lőrinczi, A.; Matei, E.; Ciobanu, R.; Baibarac, M. Optical and Structural Properties of Composites Based on Poly(urethane) and TiO2 Nanowires. Materials 2023, 16, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaliya, J.; Kutcherlapati, S.N.R.; Dhore, N.; Punugupati, N.; Sunkara, K.L.; Misra, S.; Joshi, S.S.K. Soybean Oil-Derived, Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane-TiO2 Nanocomposites with Enhanced Thermal, Mechanical, Hydrophobic and Antimicrobial Properties. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, A.; Pakseresht, A.; Duran, A.; Castro, Y.; Galusek, D. Electrochemical Characterization of Polymeric Coatings for Corrosion Protection: A Review of Advances and Perspectives. Polymers 2022, 14, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Alateyah, A.; Hasan, H.; Matli, P.; Seleman, M.E.; Ahmed, E.; El-Garaihy, W.; Golden, T. Enhanced Corrosion Resistance and Surface Wettability of PVDF/ZnO and PVDF/TiO2 Composite Coatings: A Comparative Study. Coating 2023, 13, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Habib, S.; Shkoor, M.; Kahraman, R.; Khaled, M.; Hussein, I.A.; Dawoud, A.; Shakoor, R. Enhanced steel surface protection using TiO2/MS30 modified polyurethane coatings: Synthesis and performance evaluation. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 417, 126669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Zafar, S.; Shkoor, M.; Khaled, M.; Hussein, I.A.; Ahmed, E.M.; Dawoud, A.; Shakoor, R. Improving corrosion inhibition of steel using polyurethane based composite coatings by incorporating zirconia nanoparticles and novel urea-based inhibitor. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 511, 132316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanović, I.S.; Džunuzović, J.V.; Džunuzović, E.S.; Randjelović, D.V.; Pavlović, V.B.; Basagni, A.; Marega, C. Insight into the Morphology, Hydrophobicity and Swelling Behavior of TiO2-Reinforced Polyurethane. Coatings 2025, 15, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, A.S.; Joseph, A.; Nair, B.G.; Vandana, S. MoS2/Ag-TiO2/Polyurethane Nanocomposite as a Photocatalytic Coating for Antibiofouling Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 19024–19042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, S.M.; Hojjati, M.; Liberati, A.C.; Moreau, C. Erosion resistance enhancement of polymeric composites with air plasma sprayed coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 455, 129211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, G.H.; Abuelenain, D.; Mazhar, J.; Alnowaiser, A.; Aljawi, R.; Hamed, M.T. Maximizing Dental Composite Performance: Strength and Hardness Enhanced by Innovative Polymer-Coated MgO Nanoparticles. J. Dent. 2024, 149, 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaurani, P.; Hindocha, A.D.; Jayasinghe, R.M.; Pai, U.Y.; Batra, K.; Price, C. Effect of addition of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the antimicrobial properties, surface roughness and surface hardness of polymethyl methacrylate: A Systematic Review. F1000Research 2023, 12, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kianpour, G.; Bagheri, R.; Pourjavadi, A.; Ghanbari, H. Synergy of titanium dioxide nanotubes and polyurethane properties for bypass graft application: Excellent flexibility and biocompatibility. Mater. Des. 2022, 215, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pei, F.; Lin, W.; Lei, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y. Oxygen vacancies-rich TiO2−x enhanced composite polyurethane electrolytes for high-voltage solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seenath, A.A.; Baig, M.M.A.; Katiyar, J.K.; Mohammed, A.S. A Comprehensive Review on the Tribological Evaluation of Polyether Ether Ketone Pristine and Composite Coatings. Polymer 2024, 16, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfilas, M.; Torres, G.B.; Lorenzi, R.; Saibene, M.; Mauri, M.; Simonutti, R. Transparent and High-Refractive-Index Titanium Dioxide/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposites. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29339–29349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, T.J., II. Characterization of TiO2/Polyurethane Composite Coatings. Master’s Thesis, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA; OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, 2022. Available online: https://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=miami1650470214460894 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Abdellatif, A.S.; Shahien, M.; El-Saeed, A.M.; Zaki, A.H. Titanate–polyurethane–chitosan ternary nanocomposite as an efficient coating for steel against corrosion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Hu, Q.; Shao, T.; Yang, R.; Wang, B.; Wan, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. Experimental Study on Neutral Salt Spray Accelerated Corrosion of Metal Protective Coatings for Power-Transmission and Transformation Equipment. Coatings 2023, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.A.; Lapierre, Z.; Williams, T.; Hope, C.; Jardin, T.; Rodriguez, R.; Menezes, P.L. Wear- and Corrosion-Resistant Coatings for Extreme Environments: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2025, 15, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Ma, T.; Wei, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, R. Progress of material degradation: Metals and polymers in deep-sea environments. Corros. Rev. 2024, 43, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, O.V.; Koval, T.V.; Veligodsky, I.M.; Dvirnaya, E.V. Long-Term Environmental Aging of Polymer Composite Coatings: Characterization and Evaluation by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).