In Situ Characterization of the Growth of Passivation Films by Electrochemical-Synchrotron Radiation Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Characterization

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experiment

2.2.1. Pre-Processing Experiments

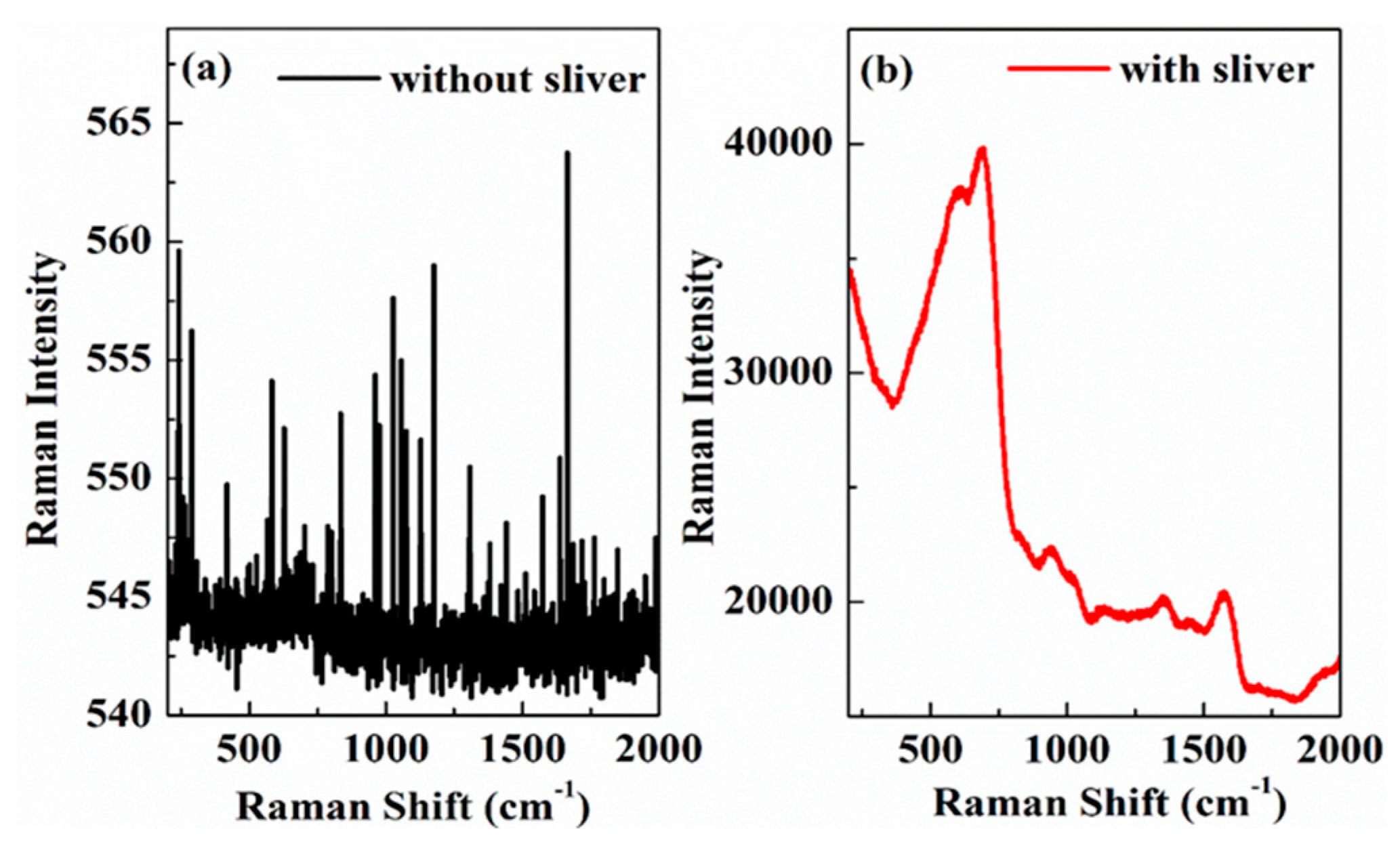

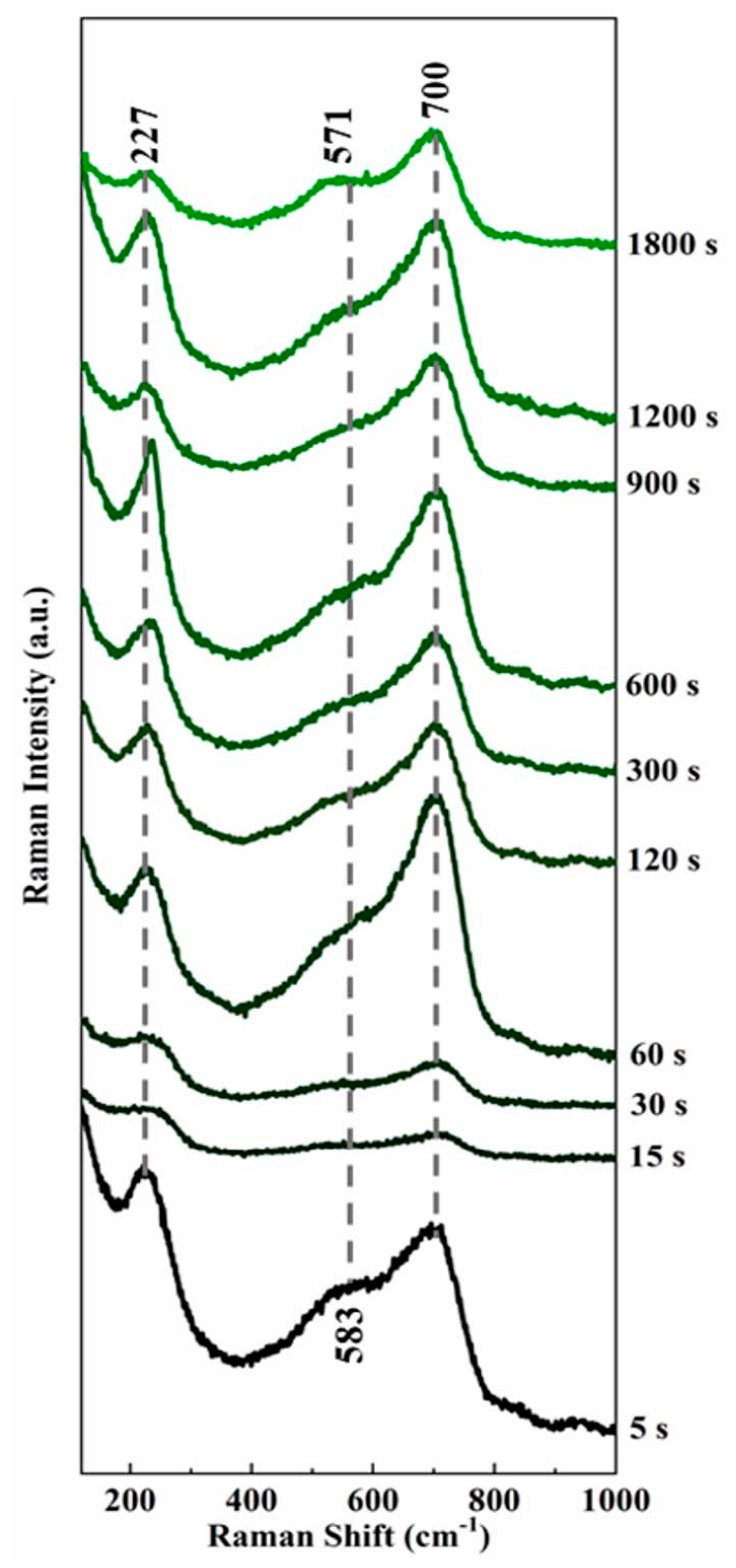

2.2.2. In Situ Electrochemistry—Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy-Coupled Experiment

2.2.3. In Situ Electrochemical-Synchrotron Grazing-Incidence X-Ray Diffraction Coupling Experiments

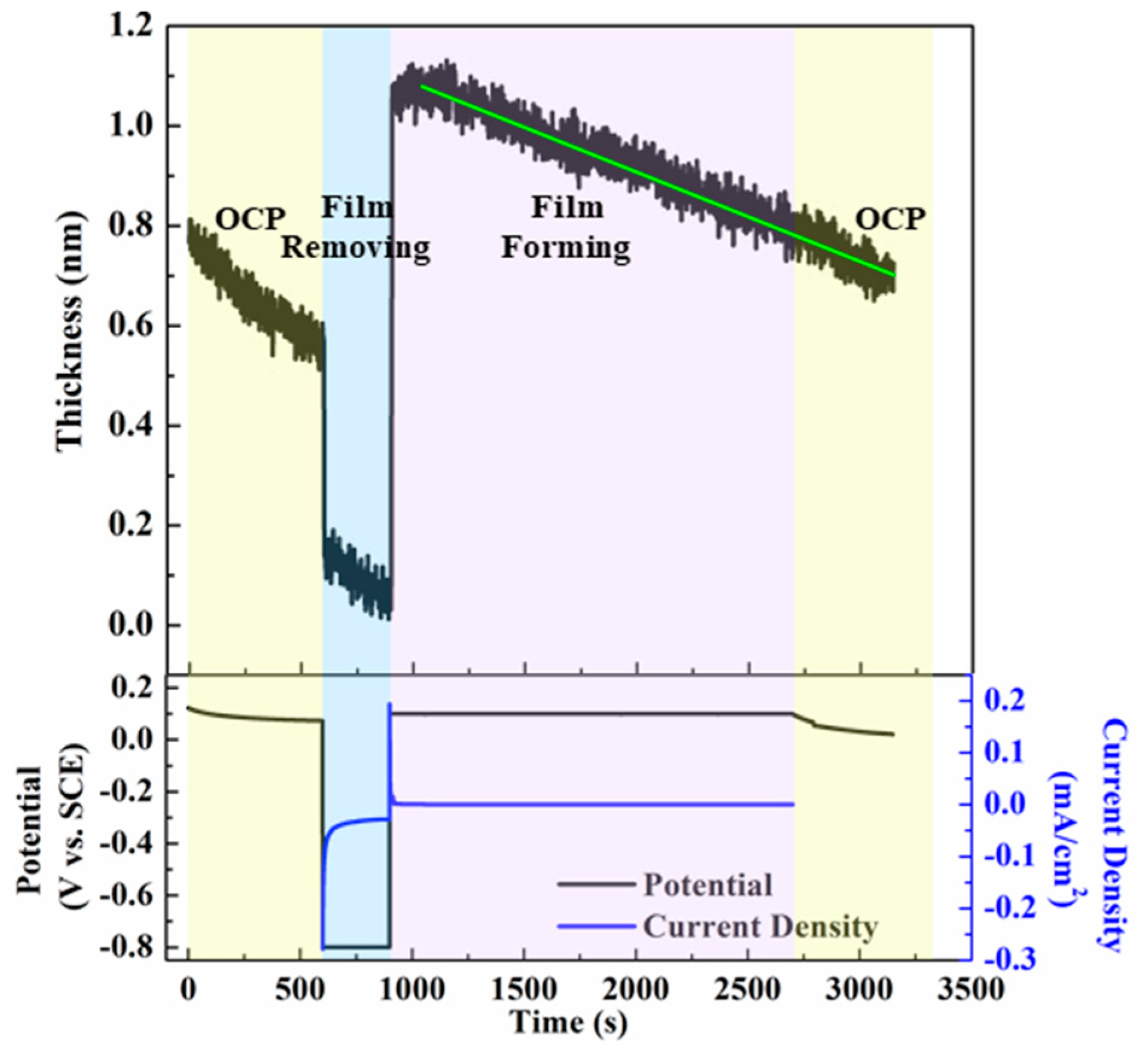

2.2.4. The Passivation Film Potential

3. Results and Discussion

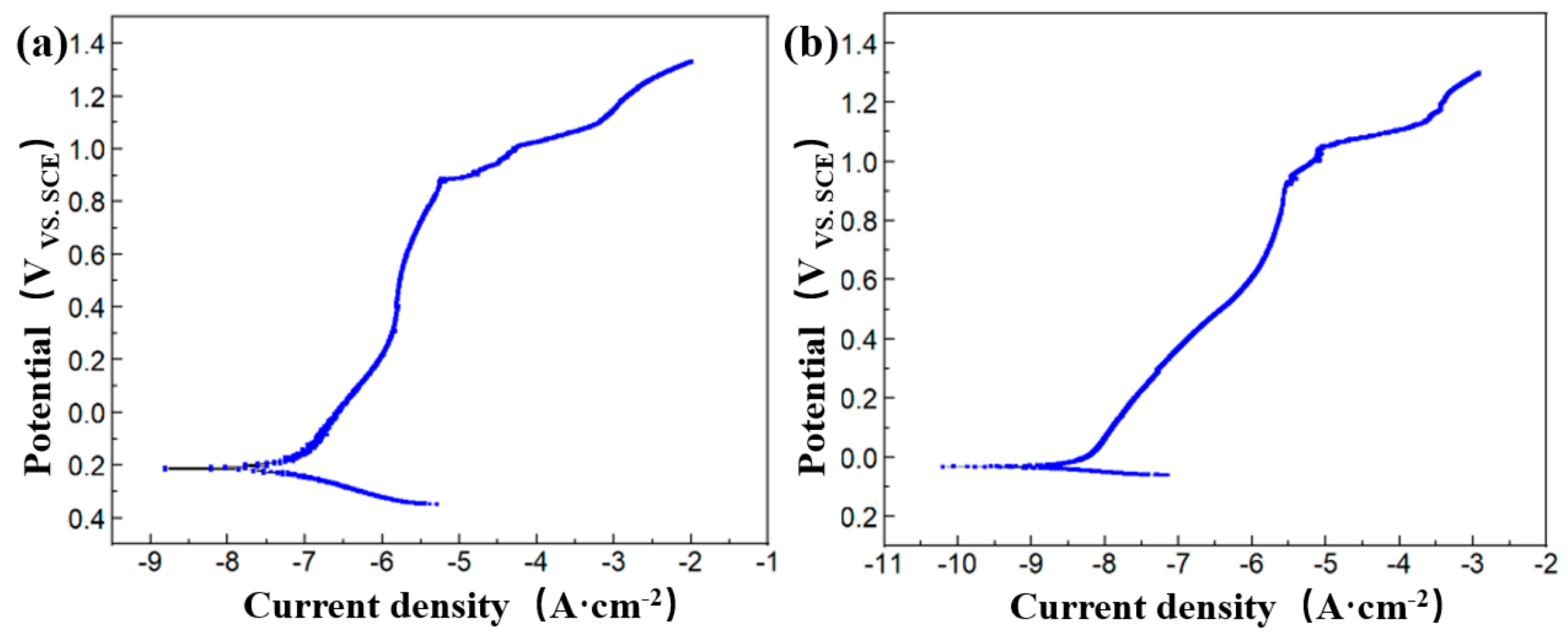

3.1. The Evolution Law of Passivation Film Electrochemical Properties

3.2. The Evolutionary Rules of Passivation Film Molecular Structure

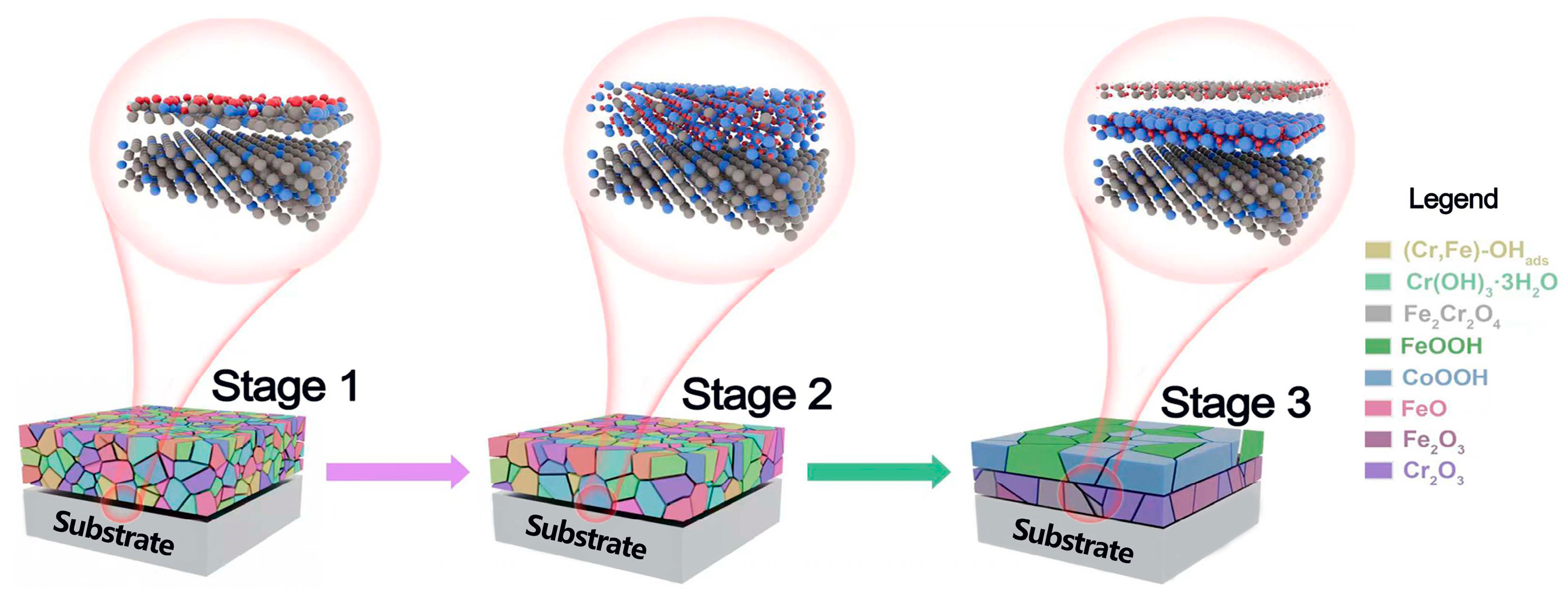

3.3. The Evolution Law of Passivation Film Phase and Crystal Structure

3.4. The Evolution Laws of in Situ Surface Passive Flim Morphology-Performance Relationships

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, Y.; Mei, J.; Peng, Q.; Han, E.H.; Ke, W. Effect of electropolishing on corrosion of nuclear grade 316L stainless steel in deaerated high temperature water. Corros. Sci. 2016, 112, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorang, G.; Da Cunha Belo, M.; Langeron, J.P. Sputter profiling of passivation films in Fe–Cr alloys: A quantitative approach by Auger electron spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1987, 5, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotta, C.; De Cristofano, N.; Salvarezza, R.C.; Arvia, A. The influence of temperature and the role of chromium in the passive layer in relation to pitting corrosion of 316 stainless steel in NaCl solution. Electrochim. Acta 1986, 31, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Cui, Z. Characterization of the passive properties of 254SMO stainless steel in simulated desulfurized flue gas condensates by electrochemical analysis, XPS and ToF-SIMS. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Macdonald, D.D.; Dong, C. Passivation film on 2205 duplex stainless steel studied by photo-electrochemistry and ARXPS methods. Corros. Sci. 2019, 146, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Fujimoto, S.; Chihara, O.; Shibata, T. Semiconductive behavior of passivation films formed on pure Cr and Fe–Cr alloys in sulfuric acid solution. Electrochim. Acta 2002, 47, 4357–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Di-Franco, F.; Seyeux, A.; Zanna, S.; Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Passivation-induced physicochemical alterations of the native surface oxide film on 316L austenitic stainless steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C3376–C3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.R.; Clayton, C.R.; Doss, K.; Lu, Y.C. On the role of Cr in the passivity of stainless steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1986, 133, 2459–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Guo, X.W.; Wang, Y.J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.C.; Du, K.; Oguzie, E.E.; Ma, X.L. Unmasking chloride attack on the passivation film of metals. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, V.; Yang, W.P.; Marcus, P. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Scanning Tunneling Microscopy Study of Passivation Films Formed on (100) Fe–18Cr–13Ni Single-Crystal Surfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblonsky, L.J.; Devine, T.M. A surface enhanced Raman spectroscopic study of the passivation films formed in borate buffer on iron, nickel, chromium and stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 1995, 37, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, G.; Cruz, V.; Bhat, N.; Birbilis, N. On the in-situ characterisation of metastable pitting using 316L stainless steel as a case study. Corros. Sci. 2020, 177, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Collins, L.; Balke, N.; Liaw, P.K.; Yang, B. In-situ electrochemical-AFM study of localized corrosion of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys in chloride solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Nanda, D.G.K.; Mudali, U.K. In-situ Raman and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies on the pitting corrosion of modified 9Cr–1Mo steel in neutral chloride solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.M.; Wang, J.Q.; Qing, Q. Chinese high energy photon source and the test facility. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 2014, 44, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Qiao, L.; Sun, D. In-situ XAFS and SERS study of self-healing of passivation film on Ti in Hank’s physiological solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 496, 143657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Sun, D. Quantitative analysis of local fine structure on diffusion of point defects in passivation film on Ti. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 314, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Chen, J.; Borondics, F.; Glans, P.-A.; West, M.W.; Chang, C.-L.; Salmeron, M.; Guo, J. In situ soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigation of electrochemical corrosion of copper in aqueous NaHCO3 solution. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkar, M.; Robinson, J.; Forty, A. In situ structural studies of the passivation film on iron and iron/chromium alloys using X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1990, 89, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzler, N.; Schutter, J.; Wagner, R.; Dimper, M.; Lützenkirchen-Hecht, D.; Ozcan, O. Trained to corrode: Cultivation in the presence of Fe(III) increases the electrochemical activity of iron reducing bacteria—An in situ electrochemical XANES study. Electrochem. Commun. 2020, 112, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

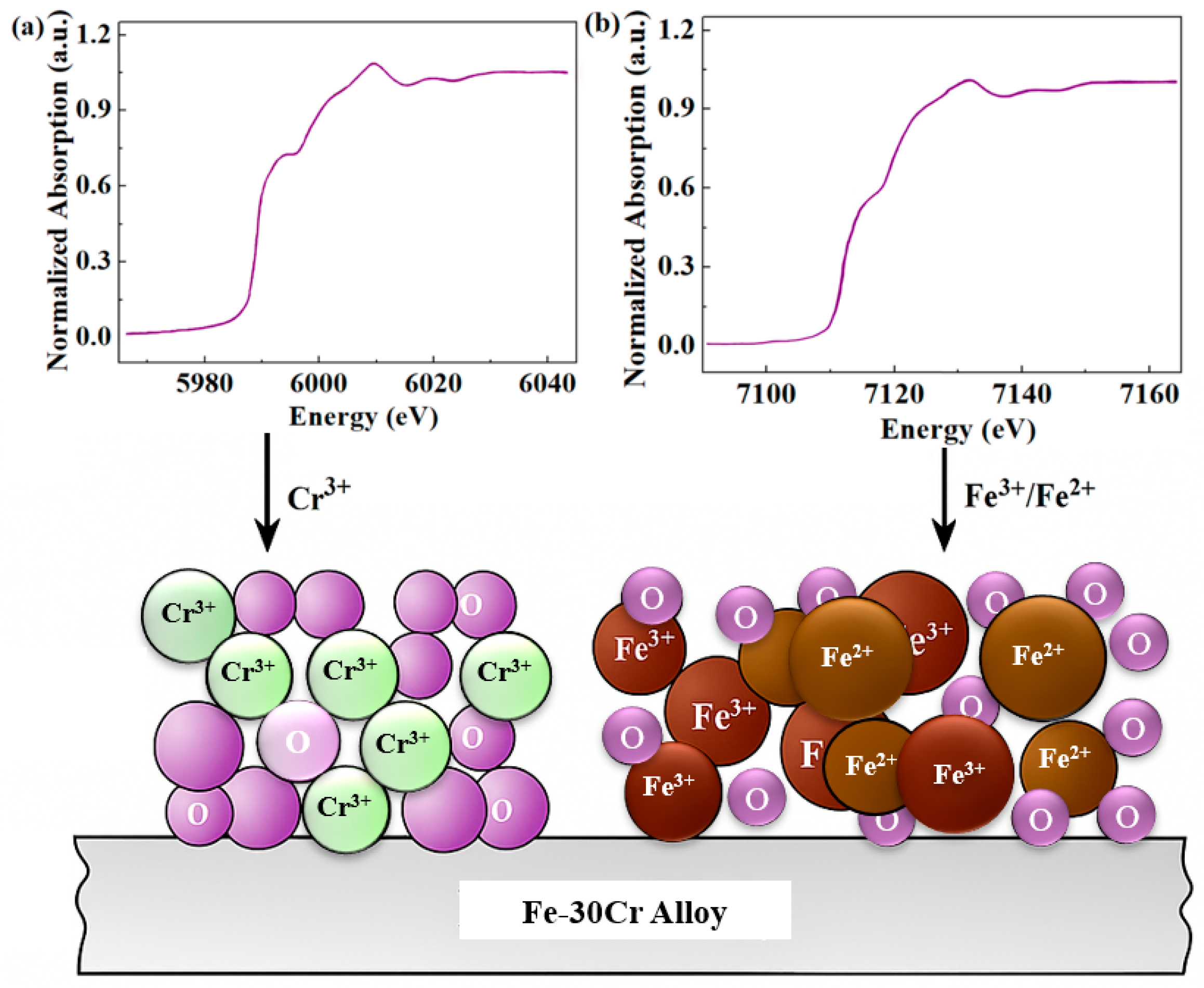

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Sun, D. Structure-activity relationship of the passivation film on Fe-xCr alloys under the interaction of corrosion and biofouling revealed by synchrotron radiation. Solid State Ion. 2022, 388, 116078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Cui, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, D. Operando characterization of Cr-containing alloy passivation film by synchrotron radiation. Corros. Sci. 2024, 236, 112233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogieglo, W.; Wormeester, H.; Eichhorn, K.; Wessling, M.; Benes, N.E. In situ ellipsometry studies on swelling of thin polymer films: A review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 42, 42–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wei, X.X.; Ma, X.L. New understanding on the critical factors determining stability of passivation film on Fe-Cr alloy based on aberration-corrected TEM study. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2024, 71, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Heard, P.J.; Greenwell, S.J.; Flewitt, P.E.J. A study of breakaway oxidation of 9Cr–1Mo steel in a Hot CO2 atmosphere using Raman spectroscopy. Mater. High Temp. 2018, 35, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, M.; Jia, J.; Cheng, X.; Pei, Z.; Li, Q.; Xu, D.; Xiao, K.; Li, X. A new understanding of the effect of Cr on the corrosion resistance evolution of weathering steel based on big data technology. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 104, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refait, P.; Jeannin, M.; Urios, T.; Fagot, A.; Sabot, R. Corrosion of low alloy steel in stagnant artificial or stirred natural seawater: The role of Al and Cr. Mater. Corros. 2019, 70, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtani, H.K.; Khan, M.I.; Jaya, B.N.; Parida, S.; Prasad, M.J.N.V.; Samajdar, I. The oxidation behavior of iron-chromium alloys: The defining role of substrate chemistry on kinetics, microstructure and mechanical properties of the oxide scale. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 871, 159583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidhar, K.N.; Khanchandani, H.; Zhang, S.; da Silva, A.K.; Scheu, C.; Gault, B.; Ponge, D.; Raabe, D. Understanding the protective ability of the native oxide on an Fe-13 at% Cr alloy at the atomic scale: A combined atom probe and electron microscopy study. Corros. Sci. 2023, 211, 110848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, S.A.; Moulin, J.; Tromp, M.; Reid, G.; Dent, A.J.; Cibin, G.; McGuinness, D.S.; Evans, J. Activation of [CrCl3{R-SN(H)SR}] catalysts for selective trimerization of ethene: A freeze-quench Cr K-edge XAFS study. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 4201–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvin, S. XAFS for Everyone; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.T.; Hsu, C.W.; Lee, J.F.; Pao, C.W.; Hsu, I.J. Theoretical analysis of Fe K-edge XANES on iron pentacarbonyl. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 4991–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, M.; Bohnenkamp, K.; Engell, H.J. An electrochemical study of phase-transitions in rust layers. Corros. Sci. 1983, 23, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Gao, K. Understanding the general and localized corrosion mechanisms of Cr-containing steels in supercritical CO2-saturated aqueous environments. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 792, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hao, S.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Di, X.; Huang, Y. Direct evidence of passivation film growth on 316 stainless steel in alkaline solution. Mater. Charact. 2017, 131, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, D.; Solokha, V.; Wilson, A.; Carlomagno, I.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, M.; Reddy, V.R.; Meneghini, C.; Carla, F.; Morawe, C.; et al. Studying the onset of galvanic steel corrosion in situ using thin films: Film preparation, characterization and application to pitting. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2021, 33, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Yonezawa, T.; Shobu, T.; Shoji, T. Measurement methods for surface oxides on SUS 316L in simulated light water reactor coolant environments using synchrotron XRD and XRF. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 434, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time of Film-Forming | 2-Theta (°) | d (A) | Height (%) | FWHM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 s | 13.684 | 6.4659 | 100 | 0.138 |

| 20.003 | 4.4352 | 70.3 | 0.259 | |

| 27.312 | 3.2626 | 9 | 0.221 | |

| 15 s | 13.698 | 6.4594 | 100 | 0.137 |

| 19.879 | 4.4625 | 47.1 | 0.152 | |

| 27.269 | 3.2677 | 8.8 | 0.233 | |

| 30 s | 13.697 | 6.4595 | 100 | 0.133 |

| 20.003 | 4.4352 | 65 | 0.068 | |

| 27.314 | 3.2624 | 18.9 | 0.133 | |

| 60 s | 13.684 | 6.4657 | 100 | 0.137 |

| 20.017 | 4.4321 | 82.5 | 0.159 | |

| 27.298 | 3.2642 | 9.8 | 0.214 | |

| 120 s | 13.684 | 6.4657 | 100 | 0.139 |

| 20.005 | 4.4349 | 83.1 | 0.175 | |

| 27.312 | 3.2626 | 10.5 | 0.206 | |

| 300 s | 13.697 | 6.4596 | 100 | 0.135 |

| 19.998 | 4.4363 | 40.9 | 0.079 | |

| 27.313 | 3.2625 | 14 | 0.156 | |

| 600 s | 13.697 | 6.4596 | 100 | 0.131 |

| 19.988 | 4.4384 | 40.7 | 0.095 | |

| 27.313 | 3.2625 | 13.9 | 0.152 | |

| 900 s | 13.697 | 6.4595 | 100 | 0.131 |

| 19.988 | 4.4385 | 40.5 | 0.284 | |

| 27.313 | 3.2625 | 14.2 | 0.153 | |

| 1200 s | 13.697 | 6.4595 | 100 | 0.137 |

| 20.017 | 4.4321 | 68.8 | 0.283 | |

| 27.314 | 3.2624 | 21.5 | 0.13 | |

| 1800 s | 13.685 | 6.4655 | 100 | 0.136 |

| 20.017 | 4.432 | 65.8 | 0.292 | |

| 27.314 | 3.2624 | 21.6 | 0.129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, L. In Situ Characterization of the Growth of Passivation Films by Electrochemical-Synchrotron Radiation Methods. Coatings 2025, 15, 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121477

Li Z, Zhou Z, Zhao W, Liu X, Wang Y, Wen L. In Situ Characterization of the Growth of Passivation Films by Electrochemical-Synchrotron Radiation Methods. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121477

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhengyi, Zhiping Zhou, Wen Zhao, Xiaoming Liu, Yuhang Wang, and Lei Wen. 2025. "In Situ Characterization of the Growth of Passivation Films by Electrochemical-Synchrotron Radiation Methods" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121477

APA StyleLi, Z., Zhou, Z., Zhao, W., Liu, X., Wang, Y., & Wen, L. (2025). In Situ Characterization of the Growth of Passivation Films by Electrochemical-Synchrotron Radiation Methods. Coatings, 15(12), 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121477