Abstract

In this work, a complex and eco-friendly biomass raffinose monomer-modified polycarboxylate superplasticizer (RAF-PCE) was designed and synthesized via the free radical polymerization technique to simultaneously improve paste fluidity and delay fluidity loss in concrete applications. The adsorption, fluidity, and early hydration behaviors of cementitious systems after the introduction of RAF-PCE have been systematically investigated. Experimental results demonstrate that the hydroxy group in raffinose promotes the adsorption of RAF-PCE on the cement particles, thereby elevating the dispersion characteristic of cement paste through electrostatic repulsion, enabling excellent initial fluidity (310 mm). Additionally, its steric hindrance effect has also been identified to play a role in improving paste fluidity and reducing the slump loss of cement slurry. Detailed analyses unveil that RAF-PCE can reduce the concentration of free Ca2+ in the pore solution through complexation with Ca2+, which prevents the early precipitation of hydration products and realizes a delayed effect on cement hydration, ultimately evolving into a homogeneous and compact microstructure for superior compressive tensile strength of the cement mortar. The 28-day compressive strength of cement incorporating RAF-PCE reached 79.2 MPa, representing a 5.5% enhancement over conventional PCE systems. Our work provides novel insights into the promotion of innovative and green development in the concrete industry by utilizing renewable biomass resources for high-performance materials.

1. Introduction

Polycarboxylate superplasticizer (PCE) has been regarded as the most extensively utilized admixture for cement and concrete owing to its benefits of high water reduction rate, strong molecular structure design, good adaptability, and environmental friendliness compared to traditional superplasticizers [1]. PCE contains negatively charged (-COO−) groups in its backbone, enabling easy adsorption onto the positively charged cement particle surface. Additionally, its polyethylene glycol (PEG) side chains inhibit cement particle aggregation via steric hindrance [2], thereby significantly enhancing the superplasticizer’s dispersion capacity and water reduction efficiency and the rheological properties of cement slurry [3]. However, super-high-rise pumping and long-term transportation of PCE result in an excessive slump loss in concrete, thereby significantly diminishing the workability of the concrete in real construction engineering [4,5,6].

Recently, tremendous efforts have been made to scrutinize functional monomers for PCE structural design in attempts to address the slump loss of concrete cement [7]. For example, Yang et al. (2024) introduced trimethylolpropane triacrylate as a trifunctional crosslinking agent into PCE to achieve excellent initial fluidity and workability of mortar [8]. Zhang et al. (2026) proposed a controlled-release PCE with high slump retention by introducing unsaturated ester; this design significantly enhances the slow-release slump retention performance of concrete slurry [9]. Despite these successful attempts, excessive addition of PCE containing slow-release components prolongs the setting time [10]. This leads to severe retardation and significantly reduces concrete quality. Furthermore, when employing compound PCE, the time and temperature conditions of use are also pivotal [11] and therefore create a complex fabrication process and high cost, which further reduces the practical applicability of the utilization of PCE [12,13,14,15]. Hence, a rational design of PCE through the straightforward synthetic method to enhance slump retention while simultaneously controlling the setting time and retardation effect is still in high demand in the cement industry [16,17]. Therefore, designing a PCE that can enhance slump retention without excessively delaying setting remains a key challenge.

To better clarify the correlation between the molecular structure and performance of polycarboxylate superplasticizers (PCE), Table 1 summarizes the characteristic groups, water-reducing rate, retarding effect, and compressive strength data of traditional PCEs, with the biomass raffinose modified PCE (RAF-PCE) developed in this paper introduced as a comparison. The data show that polyester/polyether-type PCEs achieve dispersion through carboxyl (-COO−) groups and long polyester/polyether side chains, with water-reducing rates of 25%–35% and 25%–40%, respectively. However, their retarding effect is relatively weak, and polyester-type PCEs have limited later strength development [18,19]. This is because ester bonds undergo alkaline hydrolysis to release carboxyl groups, enhancing initial dispersion but resulting in poor long-term stability. Meanwhile, polyether side chains form a thick hydration layer on cement particle surfaces, effectively preventing particle aggregation. Although ether bonds are stable, they tend to desorb at high temperatures, leading to reduced slump retention. In contrast, amide/imide-type PCEs have advantages in retarding performance and later strength. This is because amide groups (-CONH-) can form coordinate bonds with Ca2+ on cement surfaces, leading to stronger adsorption. However, they have obvious drawbacks: the multi-step synthesis process results in higher costs [20]. Zwitterionic PCEs carry both positive and negative charges, forming an ‘ion pair’ adsorption layer on cement particle surfaces, which enhances adsorption capacity. However, strong electrostatic interactions make molecular structure regulation complex, resulting in only moderate retarding effects. They also face issues of high cost and complex synthesis processes [21,22]. These limitations highlight the bottlenecks of traditional PCEs in the synergistic optimization of dispersibility, retarding performance, and strength development.

Table 1.

Types and key performance characteristics of polycarboxylate superplasticizers.

In order to break through this bottleneck, this study focuses on natural biomass materials with renewable and environmentally friendly properties, selecting them as sustainable functional monomers to modify the molecular structure of PCE for the preparation of high-performance concrete [23]. Raffinose, a functional trisaccharide originating from natural plants, is mainly composed of galactose, fructose, and glucose, which possess an abundance of hydroxyl groups [24,25,26,27]. Leveraging these properties, the RAF-PCE we prepared achieves a balanced performance: it prolongs final setting time by 4.95 h while delivering compressive strengths of 51.9 MPa (3 days), 67.2 MPa (7 days), and 79.2 MPa (28 days). Herein, we clearly state that our work is the first to incorporate raffinose trisaccharide as a functional monomer in PCE synthesis, creating a unique molecular architecture with multiple hydroxyl groups that provide balanced dispersion and retardation properties without compromising early strength development. This specific innovation distinguishes our work from previous studies. Further detailed investigations and in-depth analysis were employed to elucidate the influence of raffinose-incorporated PCE on cement hydration behavior. It is expected that the current work will contribute to the theoretical foundation for innovative structural design and further boost the development of PCE with superior performance.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

The cement used in this study is P.O 42.5 cement as stipulated in GB/T 8076-2008 [28], with A specific surface area of ≥300 m2/kg. The particle size distribution is residue on an 80 μm sieve ≤5%, and the mineral composition distribution is C3A ≤ 8%, SO3 ≤ 3.5%. It was purchased from Changchun Yatai Cement Co., Ltd. (Changchun, China). Isopentenol polyoxyethylene ether (TPEG) with a molecular weight (Mw) of 2400 was provided by Shandong Yousuo Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). Acrylic acid (AA, 99%) and hydrogen peroxide (HP) were purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Ascorbic acid (VC, 98%), 3-mercaptopropionic (MPA, 98%), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%) were bought from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Triethylamine (TEA, 98%) and N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99%) were obtained from Tianjin Xinbote Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Acryloyl chloride (AC, 99%) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Synthesis Process

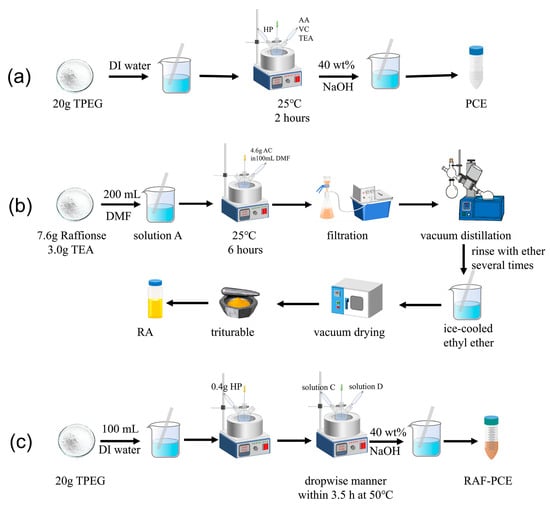

Figure 1 illustrates the synthesis strategies of two polymers and the preparation and transformation process of the key intermediate RA through clear experimental setup diagrams and reaction processes. Part a shows the synthesis process of conventional PCE. It depicts the entire process where TPEG in a 25 °C aqueous solution reacts with HP, AA, VC, and TEA in a three-necked flask for 2 h, and finally PCE is obtained by adjusting the pH to 7 with NaOH. Part b illustrates the preparation of the RA intermediate. It shows that raffinose (RA) intermediate is obtained by dissolving raffinose and TEA in DMF, then adding the AC solution dropwise under ice bath conditions, followed by reaction, filtration, vacuum distillation, ether precipitation, and drying. Part c depicts that TPEG undergoes copolymerization at 50 °C in a three-necked flask with HP, solution C containing RA, and solution D containing VC/MPA, and finally the RAF-PCE product is obtained by adjusting the pH to 7 with 40% NaOH.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis of (a) PCE, (b) RA, (c) RAF-PCE.

2.2.1. Synthesis of PCE

Then, 20 g TPEG was dissolved in deionized water in a three-neck flask under vigorous stirring at 25 °C, followed by adding a few drops of HP. Then, AA, VC, and TEA were slowly added to the above mixture. The obtained solution was further kept at 25 °C for 2 h with stirring. Finally, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 with NaOH (40 wt%) to obtain PCE for further use.

2.2.2. Synthesis of RA

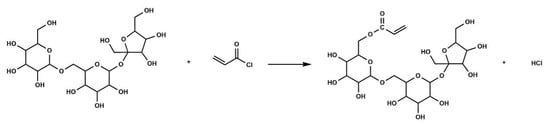

Raffinose (7.6 g) and TEA (3.0 g) were dissolved in DMF (200 mL) at ambient temperature to obtain solution A. Subsequently, AC (4.6 g) in 100 mL DMF was slowly added to solution A within 3 h with an ice water bath under vigorous stirring, followed by further reacting for 6 h at 25 °C. Then, filtration and vacuum distillation were applied to the obtained mixture to remove TEA and DMF. After that, the purified product was added to 150 mL of ice-cooled ethyl ether under vigorous stirring in a dropwise manner. Finally, the obtained yellow viscous liquid was rinsed with ether several times and then dried in a vacuum oven. The dried intermediate was sealed and stored for further use. The schematic diagram of the reaction process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the reaction process for RA.

2.2.3. Synthesis of RAF-PCE

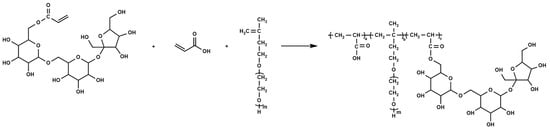

Then, 20 g TPEG was added to a three-neck flask (250 mL) with 100 mL deionized water (DI). Vigorous stirring and heating were applied to dissolve TPEG; at this point, HP (0.4 g) was slowly added within 5 min. Subsequently, solution C (2.4 g AA and 0.5 g RA in 10 mL DI water) and solution D (0.4 g VC and 0.06 g MPA in 10 mL DI water) were simultaneously added in a dropwise manner within 3.5 h at 50 °C. After cooling down to room temperature, the PH was adjusted to 7 with NaOH (40 wt%) to obtain the modified PCE with 40% raffinose. The relevant synthesis reaction was shown in Figure 3 [29].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the reaction process modified RAF-PCE.

2.3. Testing and Characterization

2.3.1. FTIR

FTIR was characterized using a Nicolet 67 (Thermo Nicolet, Madison, WI, USA) spectrometer. The water reducer after dialysis was mixed with KBr and then pressed into flakes. Spectra were recorded over a spectral range from 400 to 4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using 32 scans.

2.3.2. Fluidity Test

The fluidity of the cement slurries was determined in accordance with the GB/T 8077-2023 [30] Concrete Admixture Homogeneity Test Method. The pastes containing 0.16% PCE were prepared by mixing cement with water (w/c ratio of 0.29). The w/c = 0.29 strictly complies with the standard requirements of GB/T 8077-2023, which can effectively distinguish the dispersing performance of different water-reducing agents, ensuring the comparability and authority of the test results. Both the deionized water and the ambient environment were maintained at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C throughout the testing. The fluidity of cement paste was tested at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, respectively. Three parallel measurements according to GB/T 8077-2023.

2.3.3. Water Reduction Rate Test

The water reduction ratios of PCE in mortar were tested according to the national standard GB/T 8077-2023 method. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.3.4. Gel Permeation Chromatography

The molecular weight of hyperbranched PCE was measured using a GPC apparatus (LC-20AD, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.3.5. Adsorption Capacity Test

The adsorption capacity of the water reducer was measured by the depletion method using a total organic carbon (TOC) analyzer (Multi N/C3100, Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). The amount of PCE adsorbed on the cement was calculated based on the difference between the total amount of PCE in the initial solution and the residual amount in the interstitial solution of cement pastes. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.3.6. Zeta-Potential Measurement

Zeta-potential measurements were realized by micro-electrophoresis using Zeta Probe Analyzer TM zeta-potential analyzer (Colloidal Dynamics, Pawtucket, RI, USA).

2.3.7. Hydration Heat Measurement

A TAM AIR-08 multi-channel isothermal calorimeter (Waters Corporation, New Castle, DE, USA) was used to investigate the hydration heat of cement with PCE. The test was conducted under controlled environmental conditions of (20 ± 1) °C and a relative humidity of not less than 90%. Then, 1 g of cement, deionized water (w/c = 0.4), and PCE were mixed and poured into a specific container under stirring. The heat release curve of cement hydration was calculated by a computer.

2.3.8. Flexural Strength and Compressive Strength

The mechanical properties of cement mortar were tested in accordance with the GB/T 17671-2021 [31] standard method using 40 × 40 × 160 mm prismatic mortar specimens, with each group containing 3 specimens. The strengths of cement mortar at 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days are measured.

2.3.9. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

XRD was performed on the D/Max IIIA XRD instrument (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Cu Kα-radiation at a speed of 10°/min and a step of 0.02° in the range from 10 to 70°.

2.3.10. SEM Test

The samples were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (JSM-7610F, Beijing, China).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR Analysis

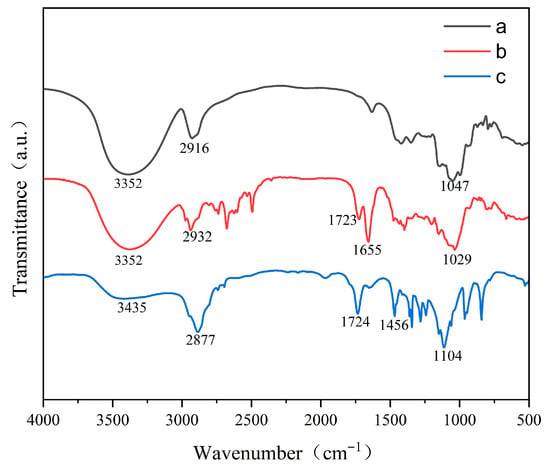

To verify the successful chemical grafting of raffinose onto the polycarboxylate superplasticizer backbone, FTIR spectroscopy was used to characterize the functional groups of monomer a (raffinose), intermediate b (raffinose acrylate), and modified water-reducing agent c (RAF-PCE). As shown in Figure 4, the peaks at 3352, 2916, and 1047 cm−1 could be assigned to the stretching vibration peak of -OH, C-H, and C-O-C in the raffinose monomer, respectively. The characteristic C=O stretching vibration peak of ester carbonyl at 1723 cm−1 and the C=C stretching vibration peak of 1655 cm−1 were also detected in intermediate b, indicating that polymerizable double bonds were successfully introduced into the raffinose structure via an esterification reaction. For RAF-PCE, the peaks at 3435, 2877, 1724, and 1104 cm−1 could be assigned to the stretching of -OH, C-H, C=O, and C-O-C, respectively, representing the combined functional groups from both the polymer backbone and the raffinose side chains. Notably, the 1724 cm−1 peak originates from the ester groups introduced during intermediate b synthesis; the other peaks reflect the complete RAF-PCE molecular structure. More importantly, the disappearance of characteristic peaks of C=C at 1655 cm−1 indicates that RAF-PCE was successfully synthesized and the monomers were completely consumed during polymerization.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectroscopy of monomer (a), intermediate (b), RAF-PCE (c).

3.2. Fluidity of Cement Paste

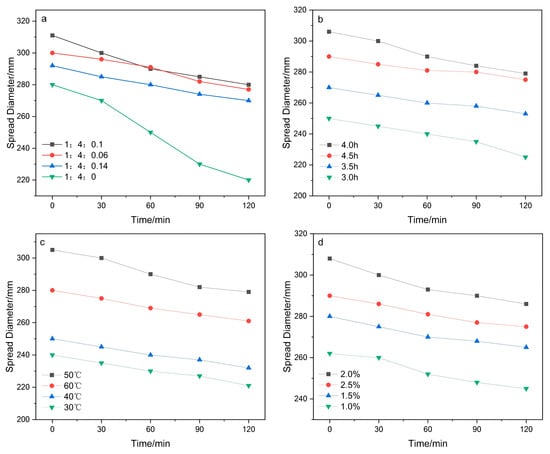

The raffinose acrylate dosage, reaction temperature, reaction time, and initiator dosage were investigated to optimize the synthetic conditions and determine the most significant factors. As indicated in Figure 5, the maximum flowability of cement slurry can reach 305 mm, and the flowability loss of cement slurry is relatively low, almost unchanged within one hour, and slightly decreased after one hour under the conditions of the molar ratio of monomer AA:TPEG:RA at 1:4:0.1; MPA at 0.5%, rection time at 4 h, and reaction temperature 50 °C.

Figure 5.

The influence of different conditions on the fluidity of cement paste ((a) the amount of raffinose acrylate; (b) reaction time; (c) reaction temperature; (d) amount of initiator).

The fluidity of the PCE grafted with acrylic raffinose ester is significantly improved due to the introduction of hydroxyl groups by the raffinose molecule, which makes the surface of cement particles tend to adsorb water molecules through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. This could effectively hinder the aggregation between cement particles and slowly release water locked in the flocculated structure. Hence, the dispersion and slump retention performance of cement paste was improved. In addition, the steric hindrance effect of raffinose molecules significantly prevents cement particles from aggregating, thus contributing to significant improvements in fluidity. Meanwhile, raffinose will be gradually hydrolyzed and provide more carboxylic anion groups, which will produce obvious electrostatic repulsion between cement grains, thus improving the dispersity of cement and preventing slump loss. Benefiting from the continuous hydrolysis process, the retention performance of cement could also be enhanced.

The molecular weight of the polymer superplasticizer molecules can be readily controlled by adjusting the initiator dosage. With the increase in initiator dosage, the molecular weight of RAF-PCE is gradually decreased (Table 2), which probably originates from the high initial concentration-induced acceleration of the polymerization reaction rate and generation of more polymerized fragments. Control experiments unveil that the water reduction rate of RAF-PCE 3 (31%) is obviously higher than that of the superplasticizer.

Table 2.

Molecular weight, water reduction rate, and flowability of cement slurry with a dosage of 0.3% for RAF modified PCE prepared with different initiator dosages.

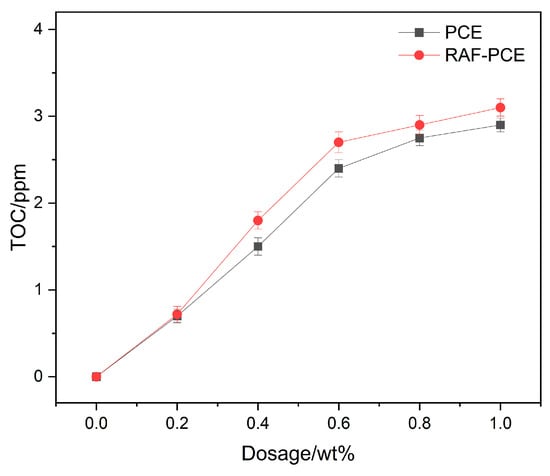

3.3. Adsorption Capacity

The adsorption capacity of polycarboxylate superplasticizers on cement particles directly determines their dispersion performance, as higher adsorption typically leads to stronger electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance, thereby improving cement paste fluidity. The adsorption capacity of PCE of cement particles was explored by the TOC analyzer. As exhibited in Figure 6, the adsorbed amounts of PCE and RAF-PCE increase linearly as a function of water-reducing agent dosage at the initial stage. This is due to the deposition of hydration products on the surface of the cement particle, which decreases the number of water reducer molecules in solution. As the water-reducing agent dosage exceeds 0.6 mg/g, the adsorption amount of PCE and RAF-PCE tends to be stable. It is noted that the adsorption capacity of the RAF-PCE is higher than that of the PCE. This was attributed to the stronger adsorption of hydroxyl groups in the RAF-PCE for cement grains.

Figure 6.

The adsorption capacity of PCE and RAF-PCE.

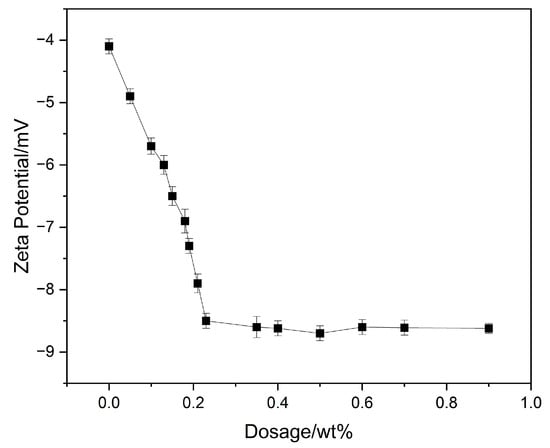

3.4. Zeta-Potential Test

The zeta-potential of cement particles in the presence of polycarboxylate superplasticizers reflects their surface charge status; a more negative zeta-potential indicates stronger electrostatic repulsion between particles, helping prevent aggregation and improve dispersion. To study the influence of RAF-PCE on cementitious systems, the zeta-potential of cement paste with various water reducer dosages was measured. Here, the surface charge property of the cement particle is highly dependent on the anionic groups of the modified water reducer. As indicated in Figure 7, the zeta-potential decreases with the increase in RAF-PCE content when the dosages of superplasticizer are less than 0.2%. This was caused by the adsorption of negative ionization groups on the surface of the cement particle. Once the relevant dosages exceed 0.2%, the surface of cement particles is saturated by superplasticizer; hence, the relevant zeta-potential reaches the plateau region (~8.5 mV), implying the superior adsorption ability of superplasticizer and excellent flowability of cement slurry [32,33].

Figure 7.

The zeta-potential of supernatant under different dosages.

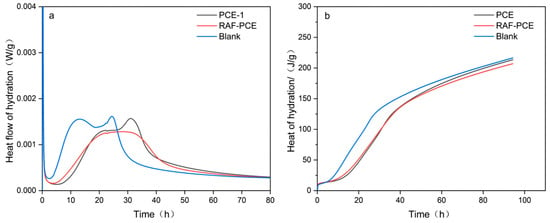

3.5. Hydration Heat Test

Hydration heat is a critical indicator of cement hydration kinetics which directly reflects the timing of hydration exothermic peaks (induction period, acceleration period), the intensity of heat release, and the total heat generated, all of which are closely linked to cement setting time, early strength development, and potential thermal cracking in mass concrete. To systematically investigate the effect of water reducer on the hydration process, the heat flow and heat release were evaluated using a multi-channel isothermal calorimeter. Compared with the blank sample, the hydration exothermic peak of cement pastes with RAF-PCE and PCE reflects different degrees of delay (Figure 8a), indicating that the addition of superplasticizer can prolong the hydration of cement. Interestingly, the hydration heat of cement pastes containing RAF-PCE exhibits a lower and wider peak than that of PCE. The above results are probably attributed to the increase in adhesion of polymer molecules and the dense hydrates generated on the surface of the cement particles, which effectively impede the dissolution rate and delay cement hydration. In addition, the anion functional group of the water reducer could complex with Ca2+ in the cement, and therefore suppresses the nucleation and growth of the hydration mineral [34,35,36], which prolongs the induction period of the cement hydration. Figure 8b is the hydration heat release curve. As indicated, the cement pastes with RAF-PCE exhibit the smallest hydration heat release, which is consistent with the law of hydration heat flow.

Figure 8.

Heat flow and heat release of cement hydration. (a) Hydration heat release rate curve, (b) hydration heat release curve.

3.6. Setting Time

Next, the influence of the RAF-PCE on the setting time of cement paste was studied. The initial and final setting times of the cement paste are defined as the times at the initial solidification and subsequent hardening, respectively [29,37]. As shown in Table 3, the initial and final setting times of cement pastes with RAF-PCE are longer than those of PCE and the blank sample, signifying that RAF-PCE displays a superior retarding effect compared to the others. This result stems from that the hydrophilic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in the modified superplasticizer can not only adsorb on the surface of cement grains and combine with hydration products via hydrogen bond [38,39], but also interact with the Ca2+ in the cement system to form various calcium chelates, reducing hydration reaction rate of cement slurry, thus delaying the setting time [40].

Table 3.

The setting time of cement pastes with blank, PCE, and RAF-PCE.

3.7. Strength of Cement Mortar

It is worth mentioning that according to the national standard GB/T 8077-2023 Test Methods for Homogeneity of Concrete Admixtures, the maximum allowable initial setting extension for retarding superplasticizers is ≤3 h. Our RAF-PCE extends the initial setting time by 2.92 h (from 2.91 h to 5.83 h), which strictly complies with this standard. This retardation effect is particularly suitable for high-rise concrete pumping and long-distance transportation (2–3 h), as it maintains workability without delaying construction schedules. Importantly, early strength development remains uncompromised (3 d compressive strength: 51.9 MPa, accounting for 65.5% of 28 d strength), fully meeting the requirements of precast component production and on-site construction.

The mechanical property of hardened mortar is a crucial reference index for assessing the modified PCE [41]. The flexural strength and compressive strength results of cement mortar with different PCE samples at 3, 7, and 28 days are presented in Table 4. As shown, for all the samples, the mortar strength increased with increasing curing time. Clearly, the compressive strength of cement mortar containing RAF-PCE is higher than that of PCE and the blank sample at different curing times, which is beneficial for prefabricated components requiring strength development. We attribute this result to the excellent dispersion and retention properties of RAF-PCE, which promote the hydration degree and crystal structure formation in the cement system. This will result in the compact structure of cement mortar and therefore ultimately improve the strength of hardened slurry. Regarding flexural strength, the cement mortar with RAF-PCE displays superior flexural strength compared to other samples. This could be ascribed to the dense structure of cement mortar with RAF-PCE, hence resulting in the reduction in cracks and delay of the crack development, which effectively restrains concrete damage and enhances the flexural strength of the hardened mortar.

Table 4.

Flexural strength and compressive strength results.

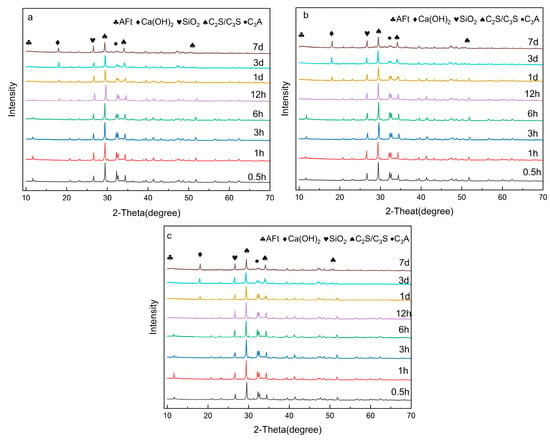

3.8. XRD

The evolution of hydration cement mineral phases with different superplasticizers was determined by XRD. As exhibited in Figure 9, the mineral chemical composition of minerals in the hardened slurry was mainly composed of calcium hydroxide (CH), C-S-H gel, ettringite (AFt), and unhydrated cement phase, including tricalcium silicate (C3S), dicalcium silicate (C2S), tricalcium aluminate (C3A), and tetracalcium ferroaluminate (C4AF). Apparently, no new peak could be observed in the cement slurry with PCE and RAF-PCE, suggesting that the addition of superplasticizers would not change the crystal structure of cement hydration products. From the above diagram, it can be seen that the C3S and other minerals in cement were gradually consumed with the continued hydration process, while the hydration products of CH and the amorphous phase are gradually increased. Compared with the blank sample, the diffraction peak intensities of AFt and CH in cement paste with PCE and RAF-PCE are lower than those of the blank group before 1 d, while the contents of unhydrated minerals such as C3S and C2S are significantly higher than those in the blank group. The results indicate induction period in the cement hydration process would be extended through the introduction of a water reducer, which weakens the cement hydration degree in the initial stage. It is proposed that such a phenomenon could be ascribed to the adsorption of PCE onto the surface of cement grain and the chelation of carboxylate and hydroxy groups with Ca2+, which is well consistent with the results of hydration heat. Additionally, as the hydration time increases to 7 d, the RAF-PCE exhibits the higher intensity peak of CH and a weaker intensity peak of unhydrated minerals such as C3S and C2S than other samples. This indicates that the modified water-reducing agent has minimal influence on the subsequent stage of cement hydration. The incorporation of RAF-PCE improves the dispersion capacity of cement particles and the degree of hydration, which is beneficial for adequate hydration of cement at a later stage.

Figure 9.

The XRD patterns of cement paste with blank (a), PCE (b), and RAF-PCE (c), respectively.

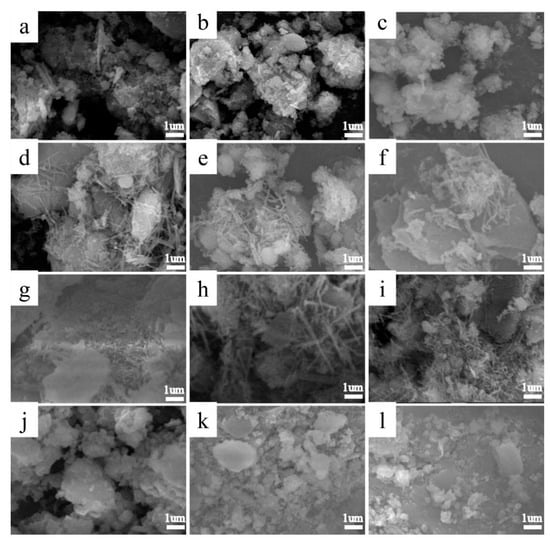

3.9. SEM

The microstructure evolution of the hardened cement-based material during the hydration process was observed by SEM measurements. As shown Figure 10, in the initial hydration stage of 12 h and 1 d (Figure 10a–f), the blank sample (Figure 10a,d) presents numerous acicular ettringite (AFt) crystals and flocculent C-S-H gel, while no apparent hydration products appear for the sample with PCE (Figure 10b,e) and RAF-PCE (Figure 10c,f), verifying the obvious inhibitory effect of water reducer in the induction period of cement hydration. By increasing hydration time to 3 d, the surface of hardened cement particles containing RAF-PCE (Figure 10i) is surrounded by a large number of C-S-H and AFt crystals. After 7 d of hydration, the AFt and C-S-H gel in the blank sample (Figure 10j) evolves into chaotic clusters and forms a loose structure with plenty of holes and cracks. Furthermore, although the relatively dense structure can be observed after the introduction of PCE, holes and cracks in the sample still existed. Interestingly, after the introduction of RAF-PCE, the hydration products become closely overlapped with each other and connect with the plate structures to form a homogeneous and compact microstructure, which facilitates the development of cement paste strength [42,43].

Figure 10.

SEM images of the hardened cement with blank (a,d,g,j), PCE (b,e,h,k), and RAF-PCE (c,f,i,l) after 12 h, 1 d, 3 d, and 7 d.

3.10. Environmental and Sustainability Assessment

- (1)

- Raffinose is extracted from agricultural by-products (such as beet molasses and cottonseed), which reduces reliance on fossil-derived monomers, promotes high-value utilization of waste resources, and reflects the sustainability of raw materials.

- (2)

- The synthesis process of RAF-PCE is green and environmentally friendly. Esterification and free radical polymerization reactions are carried out at low temperatures (≤50 °C) without toxic catalysts. Compared with traditional PCE chemical modification methods, energy consumption can be effectively reduced.

- (3)

- Cement is the cornerstone of buildings and public infrastructure, and its manufacturing process is characterized by energy-intensive and high carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, estimated to account for 7.5% of global emissions [44]. The RAF-PCE in this paper has a high water reduction rate (31%), which can greatly reduce the amount of cement used while ensuring strength. In other words, the use of polycarboxylate superplasticizer with high water reduction rate can indirectly reduce In other words, using polycarboxylate superplasticizers with high water-reducing efficiency can indirectly reduce carbon dioxide emissions by reducing cement consumption, thereby helping to achieve the global “dual carbon” goals.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results and discussions above, the conclusions can be drawn as follows:

- (1)

- A novel biomass-based polycarboxylate superplasticizer (RAF-PCE) was successfully synthesized by incorporating a raffinose-derived monomer. RAF-PCE exhibits superior dispersing ability and significantly improves the fluidity retention of cement paste compared to conventional PCE, effectively addressing the issue of rapid slump loss.

- (2)

- RAF-PCE effectively delays cement hydration, as evidenced by calorimetry and setting time measurements. This retarding effect is attributed to the combined action of the strong adsorption of its hydroxyl groups onto cement particles and the complexation of its functional groups with Ca2+ ions in the pore solution, which inhibits the nucleation and growth of early hydration products.

- (3)

- The incorporation of RAF-PCE promotes the formation of a more homogeneous and compact microstructure in hardened cement paste, with reduced porosity and fewer cracks. This microstructural refinement directly translates to enhanced mechanical properties, resulting in higher compressive and flexural strength at all curing ages. The 28-day compressive strength reaches 79.2 MPa.

- (4)

- This research presents a feasible and eco-friendly strategy for developing high-performance superplasticizers by utilizing renewable biomass resources. RAF-PCE not only delivers excellent comprehensive performance but also paves the way for the green and sustainable development of the concrete industry.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Y.Y., Q.D., and W.D.; writing—review and editing, L.W., S.L., L.K., and L.Z.; supervision, Y.X., L.W., C.W., and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the science and technology development project of Jilin province, China (No. 20230508059RC), and the financial support from the Key Laboratory for Comprehensive Energy Saving of Cold Regions Architecture of the Ministry of Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Baotou Steel North-West Pioneer Construction Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Liping Zhang was employed by the company Baotou Steel North-West Pioneer Construction Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCE | polycarboxylate superplasticizer |

| RAF-PCE | raffinose monomer modified polycarboxylate superplasticizer |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| TPEG | isopentenol polyoxyethylene ether |

| Mw | molecular weight |

| AA | acrylic acid |

| HP | hydrogen peroxide |

| VC | ascorbic acid |

| MPA | 3-mercaptopropionic |

| NaOH | sodium hydroxide |

| TEA | triethylamine |

| DMF | N,N-Dimethylformamide |

| RA | synthesis of raffinose acrylate |

| AC | acryloyl chloride |

| DI | deionized |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| TOC | total organic carbon |

| GPC | gel permeation chromatography |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| CH | calcium hydroxide |

| AFt | ettringite |

| C3S | tricalcium silicate |

| C2S | dicalcium silicate |

| C3A | tricalcium aluminate |

| C4AF | tetracalcium ferroaluminate |

References

- Huang, H.; Qian, C.; Zhao, F.; Qu, J.; Guo, J.; Danzinger, M. Improvement on microstructure of concrete by polycarboxylate superplasticizer (PCE) and its influence on durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutal, A.; Partschefeld, S.; Schneider, J.; Osburg, A. Effects of bio-based plasticizers, made from starch, on the properties of fresh and hardened metakaolin-geopolymer mortar: Basic investigations. Clays Clay Miner. 2020, 68, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Long, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Preparation of Zwitterionic Polycarboxylate Dispersant and its Influence on Rheological Properties and Dispersion Mechanism of Oil Well Cement. Silicon 2025, 17, 3355–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.-L.; Lee, L.-S. Future Research Trends in High-performance Concrete: Cost-effective Considerations. Transp. Res. Rec. 1997, 1574, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.R. High performance concrete for high-rise buildings: Some crucial issues. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2016, 5, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Cui, H.; Xin, T. Comparison of ester-based slow-release polycarboxylate superplasticizers with their polycarboxylate counterparts. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 633, 127878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Sakai, E.; Miao, C.; Yu, C.; Hong, J. Chemical admixtures—Chemistry, applications and their impact on concrete microstructure and durability. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, G.; Yu, X.; Xu, D.; Yong, Q.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Z. Interaction mechanisms between polycarboxylate superplasticizers and cement, and the influence of functional groups on superplasticizer performance: A review. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 10415–10438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, P.; Chan, H.K.; Han, Z.; Liu, B.; Lei, L. Design of a Novel Starch-Modified MPEG PCE for Enhanced Slump Retention in Alkali-Activated Slag Binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2026, 165, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, R.; Shui, Z.; Wang, X.; Qian, D.; Rao, B.; Huang, J.; He, Y. Understanding the porous aggregates carrier effect on reducing autogenous shrinkage of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) based on response surface method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, W.; Zhang, F.; Mi, Y.; Wang, W.; An, Q.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Miao, J.; Hu, Z. Efficient ternary non-fullerene polymer solar cells with PCE of 11.92% and FF of 76.5%. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, R.; Priya, S.; Liu, S. Recent advances in flexible perovskite solar cells: Fabrication and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4466–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.; Qin, Y.; Uhl, A.R.; Vlachopoulos, N.; Yin, M.; Li, D.; Han, X.; Hagfeldt, A. New-generation integrated devices based on dye-sensitized and perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 476–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Klein, T.R.; Kim, D.H.; Yang, M.; Berry, J.J.; Van Hest, M.F.; Zhu, K. Scalable fabrication of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 18017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Li, M.; Siffalovic, P.; Cao, G.; Tian, J. From scalable solution fabrication of perovskite films towards commercialization of solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 518–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Miao, X.; Kong, X.; Zhou, S. Retardation effect of PCE superplasticizers with different architectures and their impacts on early strength of cement mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Cao, Z.; Yong, Q.; Zhao, H. Interaction Between Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer and Clay in Cement and Its Sensitivity Inhibition Mechanism: A Review. Materials. 2025, 18, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzu, S. Organizational commitment turnover intentions and the influence of cultural values. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 76, 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Kong, X.; Su, T.; Wang, D. Comparative study of two PCE superplasticizers with varied charge density in Portland cement and sulfoaluminate cement systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 115, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, H.; Morozowich, R. Bioerodible polyphospha zenes and their medical potential. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, H.; Tsujito, M.; Yamada, T. Intrinsic 31P NMR Chemical Shifts and the Basicities of Phosphate Groups in a Short-Chain Imino Polyphosphate. J. Solut. Chem. 2013, 42, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Ran, Q.; Liu, J.; Mao, Y.; Shang, Y.; Sha, J. New generation amphoteric comb-like copolymer superplasticizer and its properties. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2011, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ma, J.; Feng, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, G.; Liu, X. Advancing aqueous zinc-ion batteries with carbon dots: A comprehensive review. EcoEnergy 2025, 3, 254–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, E.; Soetaert, W. Biotechnical modification of carbohydrates. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 16, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.D.; Lim, C. Introduction to fish nutrition. In Nutrient Requirements and Feeding of Finfish for Aquaculture; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rodén, L. Biosynthesis of acidic glycosaminoglycans (mucopolysaccharides). Metab. Conjug. Metab. Hydrolys. 1970, 2, 345–442. [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth, V. Digestion and nutrition. In The Principles of Insect Physiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1972; pp. 476–552. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 8076-2008; Concrete Admixtures. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Benzaazoua, M.; Fall, M.; Belem, T. A contribution to understanding the hardening process of cemented pastefill. Miner. Eng. 2004, 17, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 8077-2023; Methods for Testing Uniformity of Concrete Admixtures. State Administration for Market Regulation, China National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2023.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Plank, J.; Hirsch, C. Impact of zeta potential of early cement hydration phases on superplasticizer adsorption. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Ran, Q. Preferential adsorption of superplasticizer on cement/silica fume and its effect on rheological properties of UHPC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Lothenbach, B. Cement hydration mechanisms through time—A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 9805–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.; Jeknavorian, A.; Roberts, L.; Silva, D. Impact of admixtures on the hydration kinetics of Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1289–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, J.; Odler, I. Hydration, setting and hardening. In Lea’s Chemistry of Cement and Concrete; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, F. Fundamental aspects of cement solidification and stabilisation. J. Hazard. Mater. 1997, 52, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Wang, M.; Shi, C.; Xiao, Y. Influence of the structures of polycarboxylate superplasticizer on its performance in cement-based materials-A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Ge, C.; Guo, L.; Shu, X.; Liu, J. Synergistic effects of silica nanoparticles/polycarboxylate superplasticizer modified graphene oxide on mechanical behavior and hydration process of cement composites. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 16688–16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, J.; Xu, W.; Yang, J.; Li, M. Synthesis and characterization of SSS/MA/NVCL copolymer as high temperature oil well cement retarder. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel–Aty, Y.Y.; Mahmoud, H.S.; Al-Zahrani, A.A. Experimental evaluation of consolidation techniques of fossiliferous limestone in masonry walls of heritage buildings at historic Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Adv. Res. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 1, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Deng, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zha, F. Strength and micro-structure evolution of compacted soils modified by admixtures of cement and metakaolin. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 127, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balonis, M.; Glasser, F.P. The density of cement phases. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, R.; Ma, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Carbon emission reduction in cement production catalyzed by steel solid waste. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).