Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition of Q235B Steel in Sulfuric Acid by a Novel Hybrid Film Derived from L-Aspartic Acid β-Methyl Ester and Glutaraldehyde

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

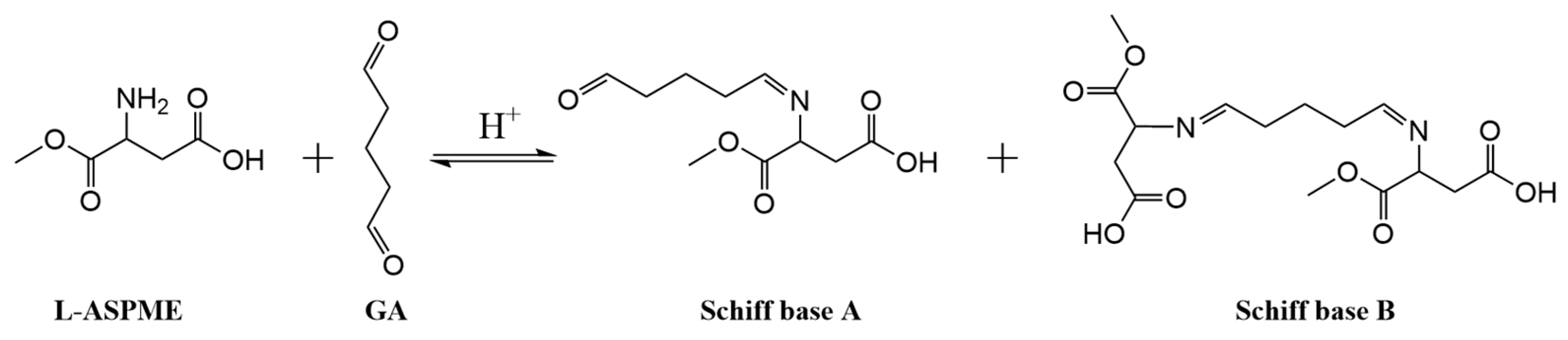

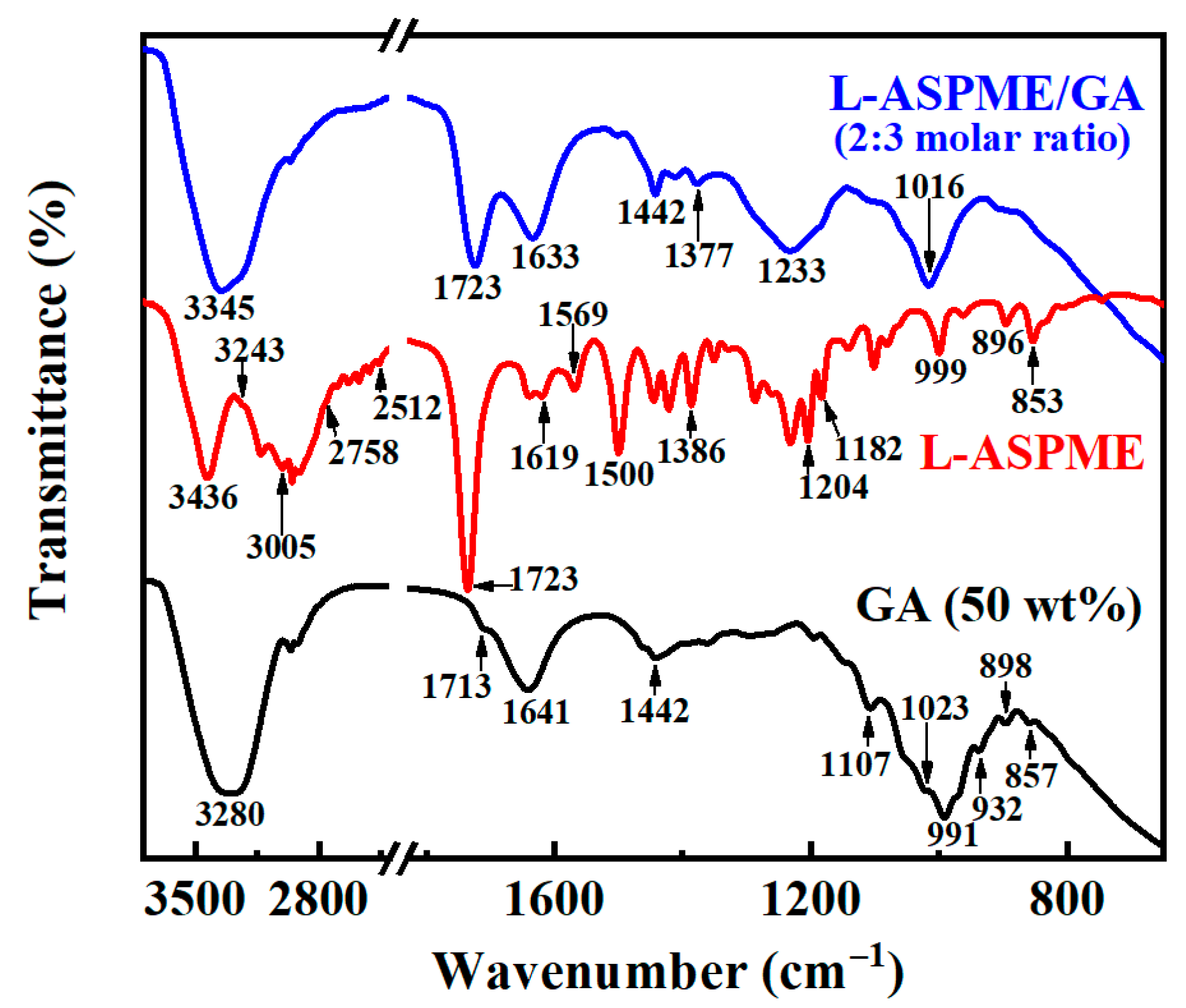

3.1. Preparation of Hybrid Inhibitors

3.2. Corrosion Inhibition Performance

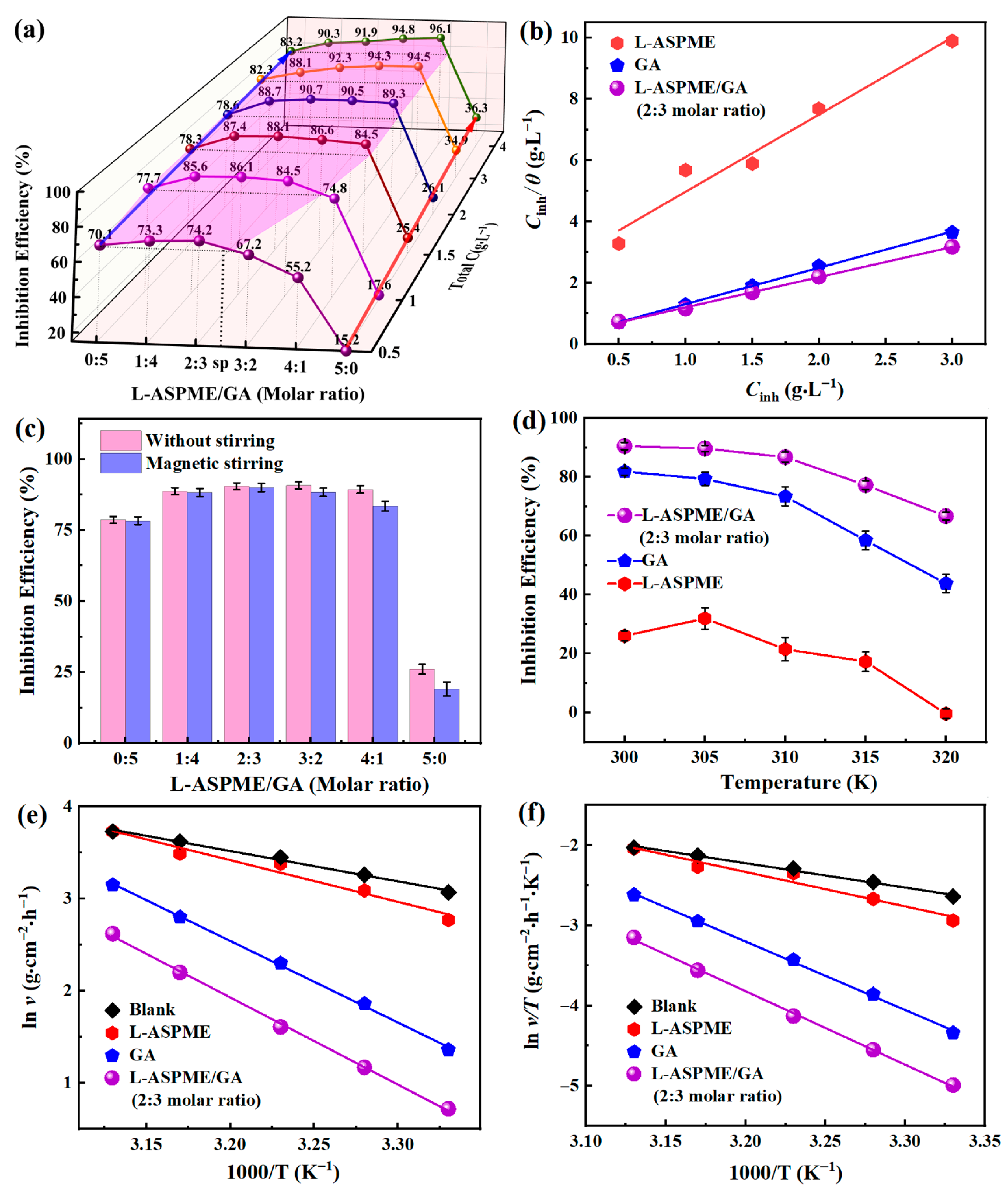

3.2.1. Weight Loss Measurements

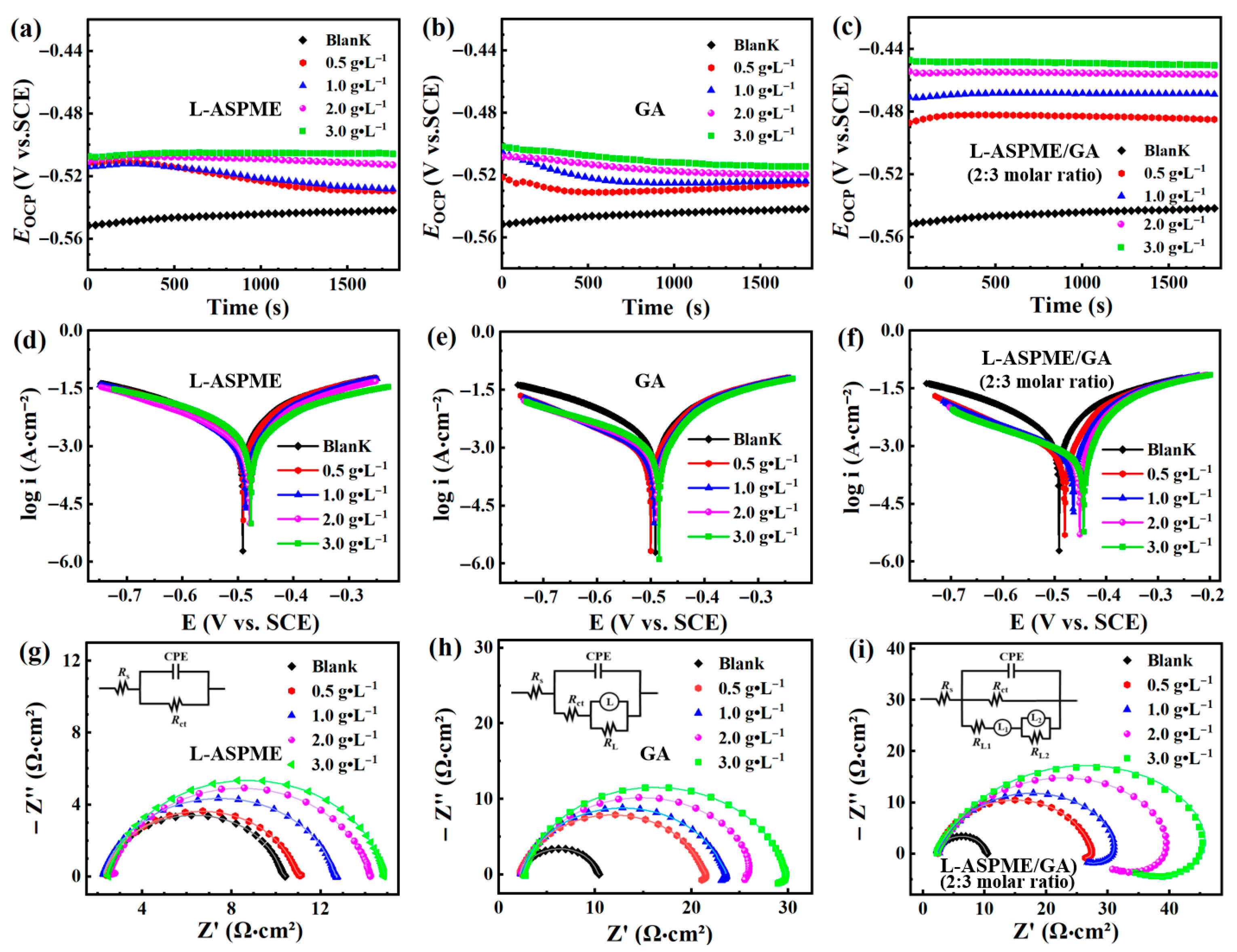

3.2.2. Electrochemical Performance

3.3. Steel Surface Analysis

3.4. Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alipanah, N.; Yari, H.; Mahdavian, M.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Bahlakeh, G. MIL-88A (Fe) filler with duplicate corrosion inhibitive barrier effect for epoxy coatings: Electrochemical, molecular simulation, and cathodic delamination studies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 97, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ituen, E.; Ekemini, E.; Lin, Y.; Li, R.; Singh, A. Mitigation of microbial biodeterioration and acid corrosion of pipework. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 149, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhu, L.; Kaya, S.; Sun, R.; Ritacca, A.G.; Wang, K.; Chang, J. Electrochemical and surface investigations of N, S codoped carbon dots as effective corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic solution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, H.U.; Akpan, E.D.; Olasunkanmi, L.O.; Verma, C.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M.; Al Farraj, D.A.; Ebenso, E.E. N-substituted carbazoles as corrosion inhibitors in microbiologically influenced and acidic corrosion of mild steel: Gravimetric, electrochemical, surface and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1223, 129328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kiey, S.A.; El-Sayed, A.A.; Khalil, A.M. Controlling corrosion protection of mild steel in acidic environment via environmentally benign organic inhibitor. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 683, 133089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathipa, V.; Raja, A.S.; Prabha, S.S. An efficient water soluble inhibitor for corrosion of carbon steel in aqueous media. Int. J. Chem. Mater. Environ. Res. 2016, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mpelwa, M.; Tang, S.F. State of the art of synthetic threshold scale inhibitors for mineral scaling in the petroleum industry: A review. Pet. Sci. 2019, 16, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Moinpour, M.; Rawat, A.; Kim, P.J.; Podlaha, E.J.; Seo, J. Molecular interactions of amino acids for corrosion control in molybdenum CMP through bridging experimental insights and DFT simulations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 698, 163046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubaaqa, M.; Ouakki, M.; Rbaa, M.; Abousalem, A.S.; Maatallah, M.; Benhiba, F.; Jarid, A.; Touhami, M.E.; Zarrouk, A. Insight into the corrosion inhibition of new amino-acids as efficient inhibitors for mild steel in HCl solution: Experimental studies and theoretical calculations. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthy, P.; Rajendran, S.; Joany, R.M.; Maheswari, T.U.; Pandiarajan, M. Influence of a biocide on the corrosion inhibition efficiency of aspartic acid Zn2+ system. Int. J. Nano Corros. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2, 2395. [Google Scholar]

- Morsi, M.S.; Barakat, Y.F.; El-Sheikh, R.; Hassan, A.M.; Baraka, D.A. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by amphoteric surfactants derived from aspartic acid. Mater. Corros. 1993, 44, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurt, A.; Bereket, G.; Ogretir, C. Quantum chemical studies on inhibition effect of amino acids and hydroxy carboxylic acids on pitting corrosion of aluminium alloy 7075 in NaCl solution. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 2005, 725, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masroor, S.; Mobin, M.; Singh, A.K.; Rao, R.A.K.; Shoeb, M.; Alam, M.J. Aspartic di-dodecyl ester hydrochloride acid and its ZnO-NPs derivative, as ingenious green corrosion defiance for carbon steel through theoretical and experimental access. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.R.; Nandi, M.M. Inhibition effect of amino acid derivatives on the corrosion of brass in 0.6 M aqueous sodium chloride solution. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2010, 17, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, M.S. Effective inhibition of T95 steel corrosion in 15 wt% HCl solution by aspartame, potassium iodide, and sodium dodecyl sulphate mixture. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Wang, J.; Zheng, M.; Hou, B. Synergistic effect of polyaspartic acid and iodide ion on corrosion inhibition of mild steel in H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 2013, 75, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Pan, L. Effect of glutaraldehyde on corrosion of X80 pipeline steel. Coatings 2021, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijkla, P.; Wang, D.; Mohamed, M.E.; Saleh, M.A.; Kumseranee, S.; Punpruk, S.; Gu, T. Efficacy of glutaraldehyde enhancement by d-limonene in the mitigation of biocorrosion of carbon steel by an oilfield biofilm consortium. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, Q.; Peng, C.; Wei, B.; Qin, Q.; Gao, L.; Bai, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, C. Effect of glutaraldehyde as a biocide against the microbiologically influenced corrosion of X80 steel pipeline. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2022, 13, 04022014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Schiff bases bearing amino acids for selective detection of Pb2+ ions in aqueous medium. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 788, 139280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bsharat, I.; Abdalla, L.; Sawafta, A.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Al-Nuri, M.A. Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial and anticancer activities of some heterocyclic imine compounds. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1289, 135789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.H.A.; ElRab, E.K.M.G.; Kamel, R.M.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M. Cost-effective removal of toxic methylene blue dye from textile effluents by new integrated crosslinked chitosan aspartic acid hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Danaee, I.; Eskandari, H.; Rashvandavei, M. Combined computational and experimental study on the adsorption and inhibition effects of N2O2 Schiff Base on the corrosion of API 5L grade B steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Purohit, A.K.; Mahakur, G.; Dash, S.; Kar, P.K. Verification of corrosion inhibition of mild steel by some 4-Aminoantipyrine-based Schiff bases-impact of adsorbate substituent and cross-conjugation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 333, 115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazya, M.A.; Hasan, A.M.; Emara, M.M.; Bakr, M.F.; Youssef, A.H. Evaluating four synthesized Schiff bases as corrosion inhibitors on the carbon. Corros. Sci. 2012, 65, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Chang, W.; Cao, J.; Hu, L.; Lu, M.; Zhang, L. Performance evaluation of a novel and effective water-soluble aldehydes as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in aggressive hydrochloric medium. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 301–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabbouha, T.; Siniti, M.; Byadi, S.; Chefira, K.; Attari, H.E.; Barhoumi, A.; Chafi, M.; Chibi, F.; Rchid, H.; Rachid, N. Insight into corrosion inhibition mechanism of carbon steel in 2 M HCl electrolyte by eco-friendly based pharmaceutical drugs. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 1535–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramotowska, S.; Zarzeczańska, D.; Dąbkowska, I.; Wcisło, A.; Niedziałkowski, P.; Czaczyk, E.; Grobelna, B.; Ossowski, T. Hydrogen bonding and protonation effects in amino acids’ anthraquinone derivatives: Spectroscopic and electrochemical studies. Spectrochim. Acta A 2019, 222, 117226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, F.; Li, C. Improved corrosion resistance of carbon steel in soft water with dendritic-polymer corrosion inhibitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K.R.; Quraishi, M.A.; Singh, A. Schiff’s base of pyridyl substituted triazoles as new and effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2014, 79, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.Y.; Mohamad, A.B.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Takriff, M.S.; Tien, L.T. Synergistic effect of potassium iodide with phthalazone on the corrosion. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 3672–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Hou, B.S.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhu, G.Y.; Liu, H.F.; Zhang, G.A. Two novel chitosan derivatives as high efficient eco-friendly inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in acidic solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 164, 108346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H.; Keles, M.; Sayın, K. Experimental and theoretical investigation of inhibition behavior of 2-((4-(dimethylamino)benzylidene)amino)benzenethiol for carbon steel in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2021, 184, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.A. On the theory of electron-transfer reactions. VI. Unified treatment for homogeneous and electrode reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1965, 43, 679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, A.; Graziano, G. Remarks on the hydration entropy of polar and nonpolar species. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, A.; Behzadi, H.; Farahati, R. DFT study of aqueous-phase adsorption of cysteine and penicillamine on Fe (110): Role of bond-breaking upon adsorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 514, 145896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Sun, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, G.; Xu, Y.; Ren, Z. The corrosion inhibition performance and mechanism of α-benzoin oxime on copper: A comprehensive study of experiments and DFT calculations. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 700, 134832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giselle, G.S.; Octavio, O.X.; Natalya, V.L.; Paulina, A.L.; Irina, V.L.; Víctor, D.J.; Diego, G.L.; Janette, A.M. Inhibition mechanism of some vinylalkylimidazolium-based polymeric ionic liquids against acid corrosion of API 5L X60 steel: Electrochemical and surface studies. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 37807−37824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, R.; Yadav, S.; Pundeer, R.; Sharma, D.K.; Mangla, B. Synthesis of novel thiazole derivatives and their assessment as efficient corrosion inhibitors on mild steel in acidic medium. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 203, 109156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y. Cysteamine modified polyaspartic acid as a new class of green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in sulfuric acid medium. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 129, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Xu, Y.H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L. Dopamine-modified polyaspartic acid as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acid solution. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 137, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Pan, S.; Ma, A.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Mamba, B.B.; Gui, J. Polymeric carboxylic acid functionalized ionic liquid as a green corrosion inhibitor: Insights into the synergistic effect with KI. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; He, L.; Xiong, P.; Lin, H.; Lai, W.; Yang, X.; Xiao, F.; Sun, X.; Qian, Q.; Liu, S.; et al. Adaptive ionization-induced tunable electric double layer for practical Zn metal batteries over wide pH and temperature ranges. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 23181−23193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Deng, S.; Li, X. Synergistic corrosion inhibition of rubber seed extract with KI on cold rolled steel in sulfuric acid solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. 2024, 161, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.M.; Schwertmann, U. Influence of organic anions on the crystallization of ferrihydrite. Clays Clay Miner. 1979, 27, 402−410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehvar, F.; Sarraf, S.; Soltanieh, M.; Seyedein, S.H. Improving bioactivity of anodic titanium oxide (ATO) layers with chlorine ion addition in electrolytes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 3493–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayoglu, Y.E.; Toomey, R.G.; Crane, N.B.; Gallant, N.D. Laser machined micropatterns, as corrosion protection of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic magnesium. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 125, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Wei, G.; Qiu, L.; Deng, S. Amphoteric surfactant of dodecyl dimethyl betaine as an efficient inhibitor for the corrosion of steel in H2SO4 solution Experimental studies and theoretical calculations. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 718, 136894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Chen, Z.L.; Tang, J.; Chen, L.; Xie, W.J.; Sun, M.X.; Huang, X.J. Study on the superhydrophilic modification and enhanced corrosion resistance method of aluminum alloy distillation desalination tubes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 446, 128770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, S.; Peng, Y.; Sang, T.; Cui, C.; Ma, H.; Dai, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, J. An extensive analysis of isoindigotin derivatives as effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic corrosive environments: An electrochemical and theoretical investigation. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 200, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrousse, N.; Salim, R.; Kaddouri, Y.; Zarrouk, A.; Zahri, D.; Hajjaji, F.; Touzani, R.; Tale, M.; Jodeh, S. The inhibition behavior of two pyrimidine-pyrazole derivatives against corrosion in hydrochloric solution: Experimental, surface analysis and in silico approach studies. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5949–5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Deng, S.; Xu, J.; Xu, D.; Shao, D.; Qu, Q.; Li, X. Invasive weed of mikania micrantha extract as a novel efficient inhibitor for the corrosion of aluminum in HNO3 solution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inhibitor (Molar Ratio) | R2 | Slope | Intercept | Kads (L·g−1) | −ΔGads (kJ·mol −1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-ASPME | 0.9652 | 2.5174 | 2.4588 | 0.4067 | −14.9854 |

| L-ASPME/GA (4:1) | 0.9996 | 0.9082 | 0.4344 | 2.3020 | −19.3090 |

| L-ASPME/GA (3:2) | 0.9992 | 0.9856 | 0.2204 | 4.5372 | −21.0013 |

| L-ASPME/GA (2:3) | 1.0000 | 1.0305 | 0.1564 | 6.3939 | −21.8569 |

| L-ASPME/GA (1:4) | 0.9991 | 1.0940 | 0.0964 | 10.3734 | −23.0639 |

| GA | 0.9991 | 1.1826 | 0.1313 | 7.6161 | −22.2932 |

| Inhibitor (Molar Ratio) | Ea (kJ·mol−1) | ΔHa* (kJ·mol−1) | ΔSa* (J·mol−1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 27.40 | 25.28 | −135.14 |

| L-ASPME | 37.61 | 35.65 | −102.86 |

| L-ASPME/GA (2:3) | 78.70 | 76.08 | 14.16 |

| GA | 73.66 | 70.90 | 2.72 |

| Composition of Inhibitor (Molar Ratio) | Concentration (g·L−1) | −Ecorr (mV vs. SCE) | ba (mV dec−1) | −bc (mV dec−1) | Icorr (μA cm−2) | ηPDP (%) | θPDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0 | 518.00 | 229.64 | 267.18 | 6138 | - | - |

| L-ASPME | 0.5 | 508.92 | 221.07 | 266.35 | 5222 | 14.9 | 0.15 |

| 1.0 | 515.66 | 220.43 | 262.23 | 5112 | 16.7 | 0.17 | |

| 2.0 | 518.11 | 214.06 | 256.90 | 4465 | 27.2 | 0.27 | |

| 3.0 | 469.79 | 104.99 | 122.36 | 3962 | 35.4 | 0.35 | |

| L-ASPME/GA (2:3) | 0.5 | 529.89 | 136.19 | 171.06 | 1291 | 79.0 | 0.79 |

| 1.0 | 497.07 | 95.45 | 178.77 | 813 | 86.8 | 0.87 | |

| 2.0 | 462.34 | 60.24 | 200.45 | 568 | 90.7 | 0.91 | |

| 3.0 | 436.90 | 29.00 | 205.50 | 439 | 92.9 | 0.93 | |

| GA | 0.5 | 541.73 | 143.57 | 175.17 | 1622 | 73.6 | 0.74 |

| 1.0 | 528.27 | 131.66 | 183.05 | 1399 | 77.2 | 0.77 | |

| 2.0 | 500.55 | 103.71 | 217.64 | 1315 | 78.6 | 0.79 | |

| 3.0 | 466.63 | 55.57 | 238.11 | 1180 | 80.8 | 0.81 |

| Composition of Inhibitor (Molar Ratio) | Concentration (g·L−1) | RS (Ω·cm2) | n | Rct (Ω·cm2) | χ2 × 10−3 | ηEIS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0.0 | 2.29 | 0.89 | 8.07 | 0.54 | - |

| L-ASPME | 0.5 | 2.31 | 0.88 | 8.71 | 0.28 | 7.4 |

| 1.0 | 2.24 | 0.88 | 10.45 | 0.21 | 22.7 | |

| 2.0 | 2.51 | 0.88 | 11.75 | 0.33 | 31.2 | |

| 3.0 | 2.43 | 0.89 | 12.50 | 0.24 | 35.4 | |

| L-ASPME/GA (2:3) | 0.5 | 2.30 | 0.86 | 27.61 | 0.06 | 70.7 |

| 1.0 | 2.33 | 0.86 | 31.35 | 0.30 | 74.2 | |

| 2.0 | 2.24 | 0.86 | 41.88 | 0.25 | 80.7 | |

| 3.0 | 2.09 | 0.86 | 48.95 | 0.20 | 83.5 | |

| GA | 0.5 | 2.16 | 0.84 | 19.32 | 0.09 | 58.18 |

| 1.0 | 2.27 | 0.85 | 21.32 | 0.04 | 62.10 | |

| 2.0 | 2.36 | 0.84 | 24.81 | 0.19 | 67.40 | |

| 3.0 | 2.51 | 0.86 | 27.39 | 0.18 | 70.50 |

| Atomic (%) | Fe | C | N | O | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 10.69 | 37.50 | 0 | 49.84 | 1.97 |

| L-ASPME | 12.91 | 27.88 | 2.40 | 54.35 | 2.46 |

| L-ASPME/GA (2:3 molar ratio) | 10.59 | 25.07 | 3.78 | 59.93 | 0.64 |

| GA | 11.81 | 43.61 | 0 | 42.63 | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, R.; Chen, W.; Jiang, X.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ding, C.; Weng, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; et al. Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition of Q235B Steel in Sulfuric Acid by a Novel Hybrid Film Derived from L-Aspartic Acid β-Methyl Ester and Glutaraldehyde. Coatings 2025, 15, 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121460

Chen R, Chen W, Jiang X, Lin L, Zhang Z, Chen Y, Ding C, Weng R, Wang Y, Xu M, et al. Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition of Q235B Steel in Sulfuric Acid by a Novel Hybrid Film Derived from L-Aspartic Acid β-Methyl Ester and Glutaraldehyde. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121460

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Rongguo, Weichang Chen, Xiaoyu Jiang, Lang Lin, Zhigang Zhang, Yilan Chen, Cuicui Ding, Rengui Weng, Yijing Wang, Mingdi Xu, and et al. 2025. "Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition of Q235B Steel in Sulfuric Acid by a Novel Hybrid Film Derived from L-Aspartic Acid β-Methyl Ester and Glutaraldehyde" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121460

APA StyleChen, R., Chen, W., Jiang, X., Lin, L., Zhang, Z., Chen, Y., Ding, C., Weng, R., Wang, Y., Xu, M., & Yu, J. (2025). Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition of Q235B Steel in Sulfuric Acid by a Novel Hybrid Film Derived from L-Aspartic Acid β-Methyl Ester and Glutaraldehyde. Coatings, 15(12), 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121460