Abstract

Improving the interfacial stability of graphite anodes remains a major challenge for extending the lifetime of lithium-ion batteries. In this study, ultrananocrystalline diamond (UNCD) and nitrogen-incorporated UNCD (N-UNCD) coatings were employed as protective layers to enhance the electrochemical and mechanical robustness of graphite electrodes. Half-cells were cycled for 60 charge–discharge cycles, and their behavior was examined through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT), and Equivalent Circuit Modeling (ECM) to disentangle the characteristic relaxation processes. The potential–capacity profiles exhibited the typical LiC12–LiC6 transition plateaus without any additional features for the coated electrodes, confirming that the UNCD and N-UNCD films do not participate in lithium storage but serve as chemically inert and electrically stable interlayers. In contrast, the uncoated reference graphite anodes showed greater capacity fluctuations and increasing interfacial impedance. DRT and ECM analyses revealed four consistent relaxation processes—electronic transport (τ1), ionic transport through the electrolyte (τ2), Solid Electrolyte Interface (SEI) response (τ3), and lithium intercalation (τ4). The τ2 process remained invariant, whereas τ3 and τ4 were markedly stabilized by the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings. UNCD exhibited the lowest SEI-related resistance and the most stable charge-transfer kinetics, while N-UNCD displayed an initially higher τ3 resistance followed by progressive self-stabilization after 20 charge/discharge cycles, linked to reorganization of nitrogen-rich grain boundaries. Overall, polycrystalline diamond coatings—particularly UNCD—proved to be highly effective in suppressing SEI layer growth, minimizing impedance rise, and preserving lithium intercalation efficiency, leading to enhanced long-term electrochemical performance. These findings highlight the potential of diamond-based protective layers as a durable and scalable strategy for next-generation graphite anodes.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have revolutionized energy storage, powering applications ranging from portable electronics to electric vehicles and stationary energy storage systems. However, their lifespan and stability remain key challenges, primarily limited by electrode degradation and the formation of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) [1,2]. During charge and discharge cycles, the SEI evolves uncontrollably, increasing internal impedance and reducing battery capacity over time [3].

Several coating strategies have been developed to improve the interfacial stability of graphite anodes, including transition-metal oxides such as MoO2 and Fe3O4, which can suppress parasitic reactions but often introduce significant resistive growth during charge/discharge cycling [4,5]. Ceramic coatings, including antimony-doped tin oxide (ATO) and TiO2, have also been employed to enhance structural stability and mitigate SEI degradation, although they may suffer from limited ionic conductivity [6,7]. Carbon-based interlayers such as amorphous carbon and graphene have been shown to buffer the interface and reduce electrolyte decomposition, yet their permeability to electrolyte species can still permit unstable SEI formation [8,9]. Beyond these traditional strategies, UNCD and N-UNCD coatings offers a distinct approach due to its chemical inertness, mechanical robustness, and electronically conductive grain boundaries, providing a highly stable and dense sp3-rich barrier at the electrode–electrolyte interface. Motivated by these unique attributes, the research described in this article focused specifically on evaluating how UNCD/N-UNCD coatings influence SEI evolution, interfacial transport, and electrochemical stability in graphite anodes, rather than conducting a broad comparison across all coating chemistries. Therefore, this research focused specifically on evaluating the interfacial and impedance effects introduced by UNCD and N-UNCD coatings [10], with the smallest grain boundaries (5–10 nm), combining high electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and mechanical strength [11]. Recent studies suggest that UNCD coating can inhibit uncontrolled SEI growth, reduce anode degradation, and enhance long-term performance [12]. However, it is not well known how stable the different processes are that occur in the battery, besides the observable capacity.

In this study, with the aim of tracking the changes in the velocity of the different processes occurring in Li ion batteries with graphite anodes covered with UNCD with different chemical characteristics, a comparative analysis of the electrochemical properties of anodes with and without UNCD or N-UNCD (nitrogen-incorporated UNCD) coatings was conducted. For this purpose, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed, and these were interpreted with the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) model and compared with the Equivalent Circuit Modeling (ECM). The DRT technique is based on the probability that a process occurs at a given time constant (τ) and is used to analyze and characterize the behavior of lithium-ion cells under different lithiation and delithiation conditions. Additionally, it is important to note that the time constants (τ) depend on the active material present, making them a key factor when analyzing and comparing the results of different half-cells.

DRT analysis provides crucial insights into electrochemical processes, including those that may overlap within lithium-ion cells. This is particularly useful for half-cell analysis as it enables a better understanding of performance, potentially leading to design optimizations [1]. Furthermore, relaxation time distribution curves represent the deconvolution of the impedance spectrum in the time domain, allowing for the differentiation of polarization effects that typically overlap in the frequency domain. These polarization effects are characterized by peaks of varying magnitudes and time constants (τ), which can be associated with distinct physical processes [1,13].

The analysis of results reveals how the presence of polycrystalline diamond coatings influences impedance, charge/discharge cycle stability, and SEI evolution over time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Morphological and Structural Characterization of UNCD and N-UNCD Coatings

The UNCD and N-UNCD films were grown using a Blue Wave Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition (HFCVD) system on commercial, double-sided graphite-coated Cu foils from MTI Corporation (Richmond, CA, USA) cut into 7 × 7 cm2 pieces. The commercial graphite/Cu electrodes (MTI Corporation) consist of a double-sided slurry-cast graphite coating deposited on a 9 μm copper foil. According to the supplier’s technical sheet, the graphite layer contains ~80 wt.% natural graphite, ~10 wt.% conductive carbon (acetylene black), and ~10 wt.% PVDF binder, with a typical active-layer thickness of 35–45 μm per side and an area loading of ~4–5 mg·cm−2. These values are consistent with the masses determined experimentally in this work (Table 1), confirming the nominal composition of the graphite coating.

Table 1.

Active material for each half-cell.

Nanodiamond seeds were deposited on the graphite/Cu surface by submerging the samples in a methanol-diluted nanodiamond blue seed solution acquired from Adamas nanotechnology, Raleigh, NC, USA. During seeding process, it was key to keep the level of the diamond solution and solvents as low as possible to reduce the amount of graphite lost due to the ultrasonic agitation [8]. Subsequently, UNCD and N-UNCD films were grown using a Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition (HFCVD) System. The gas flows were set as follows: H2 4.0 sccm, CH4 1.0 sccm, Ar 5.0 sccm for the UNCD film and H2 4.0 sccm, CH4 1.0 sccm, Ar 5.0 sccm and N2 6.0 sccm for the N-UNCD film. The process pressure was set at 5.0 Torr. The samples were kept at 3.0 cm from filaments. The substrate temperature was kept at 650 °C according to previous calibration [14]. The UNCD and N-UNCD coatings deposited by HFCVD had a nominal thickness of ~70 nm, which is within the range typically reported for UNCD films grown under similar conditions. It is important to note that this study did not aim to identify a critical or optimal coating thickness, and no systematic variation in thickness was performed. Instead, a single well-established thickness was selected to enable a controlled comparison between uncoated graphite, UNCD-coated graphite, and N-UNCD-coated graphite. As such, the results and conclusions refer to the behavior of electrodes coated with this nominal 70 nm layer. The chemical bonding in the electrodes was analyzed via visible Raman spectroscopy using a Thermo DXR Raman spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), with a 532 nm wavelength laser beam. The coating thickness and morphology were characterized using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-7800F, Akishima, Tokio, Japan), and High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) was performed using an HRTEM (JEOL ARM200F, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) system, operated at 200 keV. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) diffraction from the HRTEM images was performed with the Digital Micrograph software 3.62.4983.0 from the Gatan Microscopy Suite (GMS-3, Pleasanton, CA, USA). X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained with a Rigaku Ultima III X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) using the CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) and an angular region of 2θ = 10–100° with step-scanning of 0.05°. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed on electrodes from a dis- assembled half-cell using a Versa Probe II (VPII) XPS apparatus from Physical Electronics, Chanhassen, MN, USA, at a base pressure of 4 × 10−8 Pa. The e-beam neutralization was enabled, and the sputtering was performed with a beam of Ar+ ions at 1 KeV 0 × 0 power for 30 sec per step. Data were collected with a pass energy of 1.175 eV, while structural confirmation was performed via Raman Spectroscopy (Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution, 532 nm excitation laser).

To investigate the effect of UNCD and N-UNCD films grown on lithium-ion battery Natural Graphite (NG)/Cu anodes, half-cells were fabricated and electrochemically characterized. The anodes consisted of three different configurations: reference Natural Graphite (NG) on copper (NG/Cu), UNCD-coated NG/Cu (UNCD/NG/Cu), and N-UNCD/NG/Cu. These anodes were paired with metallic lithium (Li) counter electrodes (cathodes), and all half-cells were assembled inside an Argon gas-filled glovebox (MBraun LABstar, Garching, Munich, Germany) to prevent reaction with moisture or oxygen. The electrolyte used was 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (EC:DMC, 1:1 v/v), and a Celgard 2400 polypropylene separator was placed between the electrodes.

2.2. Lithiation and Delithiation Cycles

Lithiation (discharge) and delithiation (charge) cycles were conducted under constant-current (galvanostatic) conditions using a multichannel battery analyzer from MTI Corp (Richmond, CA, USA) to evaluate the performance of the half-cells with (NG/Cu, UNCD/NG/Cu, and N-UNCD/NG/Cu) anodes and Li cathodes, a Celgard 2400 polypropylene separator, and 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (EC:DMC = 1:1 v/v) as the electrolyte.

The first five charge/discharge cycles were intentionally performed under mild, low-current conditions to promote the controlled formation of the SEI layer and to stabilize the electrode–electrolyte interface before long-term charge/discharge cycling. This preconditioning stage ensured that subsequent capacity and impedance measurements reflected the steady-state behavior of the cells rather than transient effects associated with SEI nucleation and mechanical relaxation. Similar low-rate pre-conditioning protocols have been employed in lithium half-cells to achieve reproducible electrochemical performance and reliable kinetic analysis [15,16,17]. A low current intensity of 200 μA was therefore selected to allow the gradual establishment of equilibrium within the electrodes and the electrolyte, enabling a clear observation of the characteristic lithiation and delithiation plateaus in the potential–capacity profiles. Once this initial stabilization period was completed, the specific capacity (C-rate, in mAh/g) of each half-cell was determined and used to define the constant current for subsequent C/10 cycling. This approach minimized degradation during the early stages and ensured consistent electrochemical conditions across all tested configurations. The cells were cycled between 0.01 V and 1.2 V at a controlled temperature of 18 °C. The calculated C/10 current values for each configuration are summarized in Table 1. These parameters were subsequently applied in all following galvanostatic cycles to ensure comparability between the NG/Cu, UNCD-coated/NG/Cu, and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes. Using a normalized C-rate rather than a fixed current allowed the electrochemical response to be directly correlated with the actual amount of active material in each anode, enabling a fair evaluation of the coating effects on capacity retention and impedance evolution. Additionally, this allows stable cycling and minimizes degradation. The selected C/10 currents are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Calculated C/10 current values for each half-cell configuration.

After establishing these parameters, the same CC–CV protocol was applied for all subsequent charge/discharge cycles. Although testing was typically extended to 60 cycles, several half-cells began to exhibit performance degradation or failure beyond that point. Consequently, all comparative analyses were normalized to 60 cycles to ensure consistency across samples. While the exact cause of the early failures was not verified, imperfections in material handling or minor inconsistencies during manual cell assembly may have contributed to the limited cycling capability observed in some units. It is important to note that, due to fabrication constraints of the HFCVD system and the limited availability of NG/Cu substrates with identical specifications, each configuration (NG, UNCD, N-UNCD) was evaluated using one representative half-cell. Although replicate fabrication was not feasible during this study, the electrode preparation and UNCD/ N-UNCD films growth protocols have been standardized in our laboratory and have shown excellent reproducibility in previous works involving UNCD film growth on graphite and Si substrates. As such, the present study focuses on comparative trends rather than statistical dispersion, which constitutes a limitation and is acknowledged accordingly [14].

2.3. Determination of Active Material in Anodes

To estimate the amount of active material in each anode, the mass of the copper (Cu) current collector was first determined experimentally by weighing ten circular foil samples (16 mm in diameter) cut from the bare edges of the commercial graphite-coated sheets and calculating the average. To validate this experimental measurement, a theoretical value was also computed using the copper density (ρ = 8.94 g/cm3) and the nominal thickness provided in the datasheet (h = 9.00 × 10−4 cm), assuming a circular geometry with a diameter of 1.60 cm. The copper mass () was determined according to Equation (1):

The active material mass () was then obtained by subtracting from the total electrode mass () which was measured directly in an analytical digital balance:

These values were used to calculate the specific capacity of each anode (mAh/g) during both lithiation and delithiation processes. The corresponding data are presented in Table 2.

To complement the analysis, the Coulombic efficiency () was calculated as the ratio between delithiation and lithiation specific capacities for each charge/discharge Testscycle:

These values were plotted versus charge/discharge cycle number to evaluate electrochemical reversibility and efficiency over time.

2.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Tests

Electrochemical characterization was performed using a CHI660E Electrochemical Workstation (CH Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Before each EIS test, the Open Circuit Potential Time (OCPT) of the half-cells was measured and used as the operation potential.

Impedance spectra were collected using an amplitude of 10 mV in the 1 Hz–500 kHz frequency range, with 25 points per decade, at 18 °C. These conditions avoided high- frequency inductive and low-frequency diffusive electrochemical processes. Measurements were carried out every 10 cycles after the discharge (lithiation) stage to monitor the internal evolution of each half-cell up to the 60th charge/discharge cycle.

The resulting Nyquist plots were analyzed to extract resistive and capacitive contributions associated with electrochemical processes by Equivalent Circuit Modeling (ECM). These spectra also served as input for the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT).

2.5. Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT)

The DRT technique was applied using DRT tools, a Python-based graphical interface developed by Ciucci and Chen [18]. The impedance spectra (1 Hz–500 kHz) were fitted using Tikhonov regularization, adopting the Gaussian discretization method (second-orderegularization) and a regularization parameter of 10−3, following recommendations by Ciucci and Chen [18].

Each DRT was calculated using 100,000 samples, with a Bayesian approach to estimate 95% confidence intervals for the relaxation time distribution. For each half-cell (NG, UNCD, N-UNCD), the DRT spectra were compared across charge/discharge cycles to identify peak shifts and intensity variations associated with specific electrochemical processes.

2.6. Equivalent Circuit Modeling (ECM)

Equivalent circuit fitting was performed using EC-Lab v11.50 (BioLogic Science Instruments, France). Impedance spectra in the range of 1 Hz–500 kHz were analyzed visually to identify semicircular features representing electrochemical processes modeled as RQ elements. The semicircle diameter along the real axis was used as an initial approximation of the resistance (R) for each RQ element [19].

The spectra were fitted using the “Randomize + Simplex” algorithm with 100,000 iterations and Monte Carlo simulations (1000 iterations) to ensure reproducibility. The number of RQ elements was defined according to the observed number of semicircles in the Nyquist plots.

Once the general shape was matched, fine-tuning was performed using the Simplex optimization method, adjusting the resistance (R) and phase coefficient (a) of each Q element. The parameter a was constrained within 0.5 ≤ a ≤ 1 to preserve the capacitive behavior of Q. The corresponding pseudo-capacitances (C) were then computed to construct equivalent electrical circuit models for each half-cell [20].

2.7. Internal Resistance Modeling and Analysis

To correlate the DRT and ECM results, a unified model of internal resistance evolution was proposed. The impedance spectra of all half-cells were analyzed to determine the contribution of each physical process to the total resistance.

For each process, the time constant (τ) and internal resistance () were determined by integrating the corresponding DRT peak area within the range [].

DRT is a peak-based representation of impedance with intensity of g(τ) that helps to discriminate among overlapping processes. Each peak, with a characteristic relaxation time, could be associated with a defined physical phenomenon (e.g., electron transport, ionic transport, SEI behavior, Li+ intercalation). These analyses were carried out using OriginPro 9.0 (“Peaks and Baselines–Integrate Peaks” function).

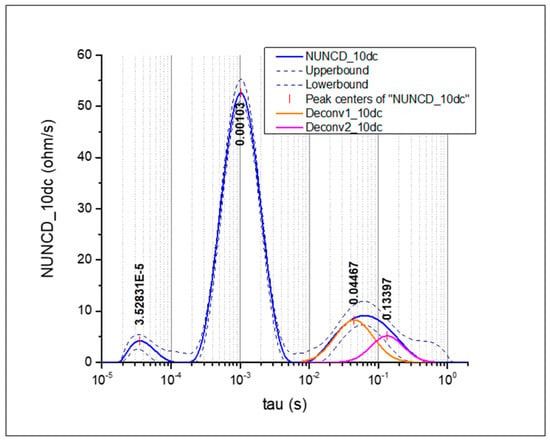

When overlapping peaks were observed, the DRT spectrum was deconvoluted into Gaussian contributions, as illustrated in Figure 1, to discriminate the different electrochemical processes and quantify their individual resistances [21].

Figure 1.

Deconvoluted DRT with two Gaussian contributions.

3. Results and Discussion

The results are organized into three main parts. Section 3.1 presents the structural and morphological characterization of the electrodes, supported by SEM, HRTEM, XRD, XPS, and Raman analyses, confirming the successful deposition and integrity of UNCD and N-UNCD films on NG/Cu substrates. Section 3.2 examines the electrochemical charge–discharge behavior, comparing the capacity retention and Coulombic efficiency of coated and uncoated NG/Cu anodes. Finally, Section 3.3 focuses on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis, including DRT and ECM analyses, to elucidate the distinct relaxation processes and interfacial stability mechanisms introduced by the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings.

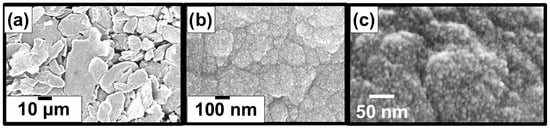

3.1. Analysis of N-UNCD Coating Surface Morphology and Structure

SEM micrographs of a N-UNCD film (Figure 2) show the surface morphology of the coating at three magnifications, highlighting that a continuous N-UNCD layer is indeed coating the surface of a NG/Cu anode. Figure 2a shows a large area at microscale, revealing a uniform film coverage across the surface. The morphology of the observed grains actually comes from the graphite and carbon black grains. N-UNCD covers the grains. Figure 2b reveals that the surface of the grains has a dense, coalesced nano- crystalline texture, which is characteristic of N-UNCD, with closely packed nodules and no obvious pinholes at this scale. Figure 2c reveals the ultrafine, “cauliflower-like” morphology at the tens-of-nanometers scale, consistent with the characteristic N-UNCD surface morphology characterized in extensive prior research related to N-UNCD coating of NG/Cu anodes and other substrate materials [12,14,22].

Figure 2.

(a) Low-magnification, (b) medium-magnification and (c) high-magnification Scanning Electron Microscope images of N-UNCD on NG/Cu anode.

The SEM images in Figure 2 confirm conformal coverage and continuity of the N-UNCD coating on NG/Cu anode, supporting the diamond phase identification obtained from XRD and Raman analyses.

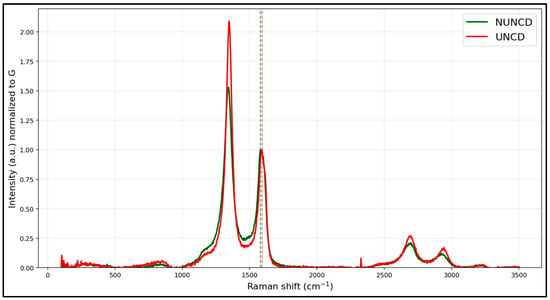

Figure 3 shows Raman spectra of NG/Cu anodes coated with N-UNCD and UNCD films. After normalizing both spectra to the G band, vertical lines on the graph (~1580 cm−1), the Raman results show that the response is dominated by graphitic sp2 bonded C atoms—with the characteristic D (~1350 cm−1) and G (~1580 cm−1) peaks present in both samples—while a discernible shoulder/peak near 1332 cm−1 evidences measurable sp3-bonded C atoms characteristic of a diamond structure attributable to the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings. Grown on top of the graphite layer, relative to the G band, the UNCD spectrum exhibits a stronger D component and more pronounced 2D/overtone features (≈2700–3000 cm−1), consistent with nanodiamond grains embedded in a sp2 matrix, whereas the spectrum for N-UNCD coating shows a comparable, sometimes slightly sharper, signature at ~1332 cm−1 together with nitrogen-related disorder in the sp2 network. Taken together, these trends confirm the coexistence of graphite and UNCD and N-UNCD phases on the NG/Cu anodes and align with the established interpretation of D–G diamond deconvolution in carbon systems [23,24].

Figure 3.

Raman spectra from analysis of UNCD and N-UNCD coatings on NG/Cu anodes.

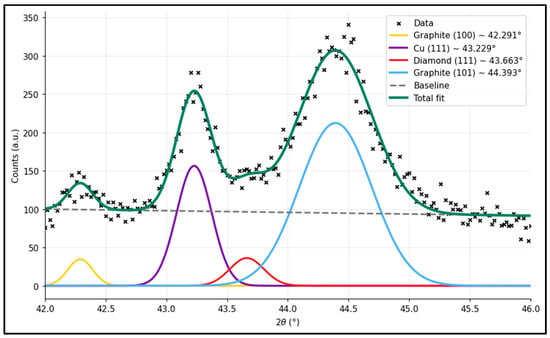

Figure 4 shows the 42–46° spectra of the XRD pattern. In the 42–46° window, the reflections near 42.3° and 44.4° correspond to the graphite (100) and (101) planes, consistent with Boehm [25]. The strong peak at ~43.3° arises from the Cu (111) substrate as described by Cullity and Stock [26]. The shoulder at ~43.7–43.9° matches the diamond (111) reflection reported for UNCD films [27], and the additional broadening observed in the N-UNCD samples is in line with the nitrogen incorporation effects described by Sumant et al. [28]. Its presence—once the overlapping contributions are separated—confirms that a diamond phase (consistent with UNCD and N-UNCD) is present on top of the NG/Cu stack.

Figure 4.

XRD spectra for a N-UNCD coating grown on NG/Cu anode.

Peak deconvolution was performed using Gaussian line shapes, and the fitted parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

XRD peak fitting results showing the contribution of graphite, copper, and diamond phases identified in the N-UNCD/Graphite/Cu electrode after deconvolution.

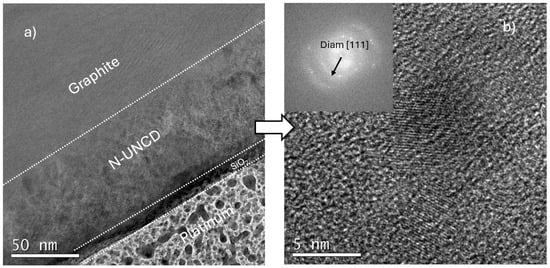

Figure 5a shows a cross-sectional HRTEM image of the multilayer structure of the N-UNCD/NG/Cu anode. As can be observed the N-UNCD coating forms a continuous, uniform film on a graphite grain, with a clearly defined and conformal interface. The micrograph of the film exhibits bright and dark regions, presumably indicating N-UNCD grains and their interphases. The platinum layer was deposited during FIB sample preparation to protect the underlying structure from ion beam damage. The intermediate SiO2 layer visible beneath the coating is an artifact of the protective lamella preparation and does not belong to the original electrode stack. Figure 5b shows a high-resolution image of the N-UNCD region revealing the nanocrystalline diamond lattice fringes with interplanar spacing consistent with the (111) planes of diamond. The inset is a selected-area fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern, exhibiting a ring with a diameter that corresponds to the diamond {111} lattice. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to determine the chemical bonding states and elemental composition of the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings, providing insight into the degree of nitrogen incorporation, surface termination, and the relative fractions of sp2 and sp3 carbon bonds. While techniques such as XRD and Raman spectroscopy confirm the crystalline phase and bonding structure at the bulk and grain-scale levels, XPS uniquely probes the surface and near-surface chemistry (≈5–10 nm depth)—the region that directly interacts with the electrolyte during battery operation. The XPS depth profile analysis was performed on a N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode that had been cycled for 20 charge–discharge cycles under standard conditions. Prior to introduction into the analysis chamber, the anode was exposed to ambient air for approximately 10 min, which likely led to partial surface oxidation and adsorption of adventitious carbon species. This short exposure was unavoidable due to sample transfer constraints but is relevant for interpreting the surface oxygen- and carbon-containing components detected in the initial spectra.

Figure 5.

HRTEM images: (a) Image showing graphite/N-UNCD/SiO2/Pt layers (the Pt layer used to protect all other layers from ion impact during focused ion beam fabrication of cross-section sample). (b) HRTEM image showing the characteristic N-UNCD structure.

Nitrogen was not analyzed in this series despite the N-UNCD nature of the coating. The decision was intentional, as the N 1s signal is expected to be very weak due to both its low atomic concentration in the film and the low relative sensitivity factor (RSF) for nitrogen in XPS measurements. Acquiring statistically meaningful N 1s data would have required prohibitively long acquisition times and increased beam exposure, potentially leading to charging or sputtering artifacts. Therefore, the focus was placed on the major electrochemically relevant elements (C, O, F, P, and Li) that dominate the surface chemistry and SEI evolution.

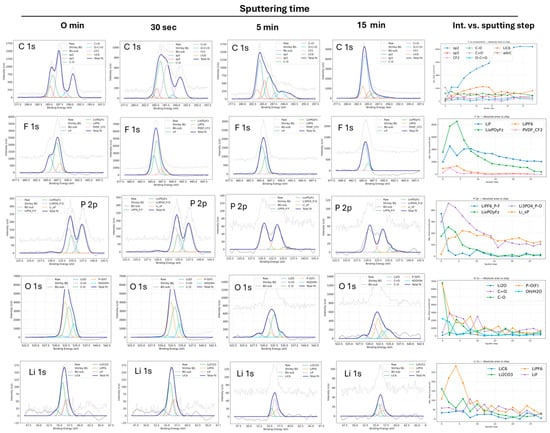

The depth-resolved XPS analysis, as it can be seen in Figure 6, reveals a clear transition from a surface dominated by organic and polymeric species to a progressively more inorganic and graphitic bulk, consistent with the expected evolution of the solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) on graphitic electrodes cycled in LiPF6-based electrolytes and coated with UNCD.

Figure 6.

XPS depth-profiling analysis of the N-UNCD/graphite anode after charge/dischcycling, showing core-level spectra (C 1s, F 1s, P 2p, O 1s, and Li 1s) at different sputtering times. The rightmost plots display the corresponding evolution of peak intensities versus sputtering time for depth profiliing.

At the surface (0–30 s sputtering), the spectra are dominated by C 1s sp3, C–O, and O–C=O components, accompanied by strong F 1s peaks corresponding to PVDF (–CF2–) and LiPF6. The P 2p region shows LiPF6 and partially hydrolyzed LixPOyFz, while O 1s exhibits broad signals attributed to carbonates and alkoxides. This topmost layer thus corrsponds to the polymeric and organic SEI phase.

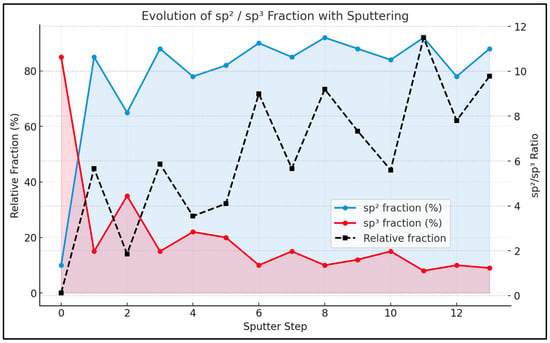

After 5 min of sputtering, the C 1s spectra show a rapid increase in the sp2 fraction, while sp3 and oxygenated species decline, indicating the partial removal of the UNCD-derived interfacial carbon and SEI matrix. This is clearly indicated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the sp2/sp3 carbon fraction during sputtering of the cycled N-UNCD-coated NG anode. The plot shows the relative fractions of sp2 (blue) and sp3 (red) carbon components obtained from the deconvolution of the C 1s XPS spectra as a function of sputtering depth, together with the calculated sp2/sp3 ratio (black dashed line).

To strengthen the interpretation of the depth-dependent chemical evolution, Table 4 reports the atomic percentages of C, O, Li, F and P at seven sputtering times (0 s, 30 s, 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, 30 min and 40 min). At the surface (0 s), the electrode is dominated by oxygen-rich organic SEI species (36.5 at.% O). After 30 s of sputtering, the composition shifts toward an inorganic SEI enriched in Li and F (27.8 and 19.2 at.%, respectively), consistent with the formation of LiF and LixPOyFz.

Table 4.

Atomic % vs. sputtering time.

Between 5 and 10 min of sputtering, the surface becomes carbon-dominated (59–64 at.% C), reflecting the progressive removal of the SEI and partial exposure of the coating and underlying graphite. At 20–30 min, carbon further increases to 75–78.5 at.% with O and F below 7 at.%, indicating near-complete removal of SEI species. At 40 min, carbon reaches 86.3 at.% with minimal contributions of O, F and P (<4 at.%), confirming full exposure of the graphite bulk and the disappearance of SEI and coating remnants.

This quantitative depth profile aligns with the evolution observed in the C 1s spectra. Simultaneously, F 1s becomes dominated by LiF (~685 eV), and P 2p reveals the formation of Li3PO4 (~134 eV) and the disappearance of fluorinated species, while the O 1s and Li 1s spectra confirm the transition from carbonates and LiPF6 to Li2O, Li3PO4 and residual LiF—signatures of the inorganic SEI [29]. At longer sputtering times (≥10–14 min), the C 1s signal is governed by sp2 carbon (~284.5 eV), indicating exposure of the underlying graphite, whereas Li 1s becomes dominated by LiC6 (~54.7 eV), confirming that both the SEI and the coating have been removed and that the intercalated graphite bulk is reached.

The overall chemical sequence LiPF6 → LixPOyFz → LiF/Li3PO4 → LiC6, coupled with the structural transition sp3 → sp2, is consistent with the transformation from a UNCD-protected, SEI-rich interface toward the electrochemically active graphite phase [10,11,30]. The persistence of LiF and phosphate residues indicates the stability of the inorganic SEI components formed upon electrolyte decomposition and coating interaction.

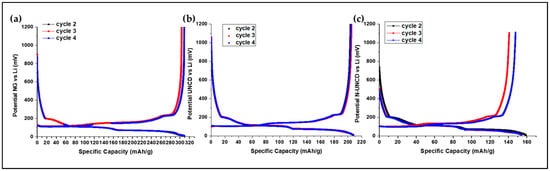

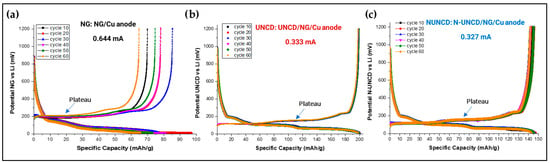

3.2. LIB Charge/Discharge Tests

To better understand the early interfacial behavior, Figure 8 shows the charge– discharge voltage profiles recorded between cycles 2 and 4 for the reference (NG/Cu), UNCD/NG/Cu, and N-UNCD/NG/Cu anodes in the half-cells LIBs. All three configurations exhibit the characteristic potential plateaus near 0.1 V and 0.2 V associated with the LiC12 → LiC6 phase transition, confirming the typical lithium intercalation mechanism within graphite.

Figure 8.

Charge and discharge plots from cycle 2 to cycle 4 for (a) reference NG/Cu anode, consisting of Natural Graphite on Cu (b) UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode, (c) N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode.

The UNCD and N-UNCD-coated anodes display smoother voltage profiles and reduced hysteresis compared with the uncoated NG/Cureference, indicating a more stable anode–electrolyte interface during the early formation of the SEI layer. Notably, the potential curves of the coated samples show negligible deviation in plateau potential, which demonstrates that the UNCD and N-UNCD layers do not contribute to lithium storage but instead function as chemically inert and electrically conductive interfacial barriers that mitigate parasitic reactions during the initial charge/discharge cycles.

These observations are consistent with the results shown in Figure 9, where the same UNCD and N-UNCD-coated anodes maintain enhanced stability and capacity retention after extended charge/discharge cycling. Overall, the early-cycle analysis confirms that UNCD and N-UNCD coatings promote a uniform SEI formation process, providing mechanical and electrochemical stabilization from the onset of charge/discharge cycling.

Figure 9.

Charge and discharge plots from cycle 10 to cycle 60 for LIB with (a) Ng/Cu anode; (b) UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode, and (c) N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode.

Figure 9 presents the charge (delithiation) and discharge (lithiation) capacity evolution of the half-cells LIBs with NG/Cu (Reference) anode, UNCD-coated NG/Cu, and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode, from charge/discharge cycle 10 to 60, using a C/10 current. The deposition of a UNCD and N-UNCD layers on natural graphite reduces the amount of active material in the anode, as reported by Villarreal et al. [14].

For the LIB with NG/Cu anode the discharge capacity shown in Figure 9a, increases progressively from cycle 10 (black) to cycle 20 (red) and cycle 30 (blue), followed by a slight decrease at cycle 40 (magenta). This behavior suggests that capacity degradation does not occur during early-stage cycling, indicating that SEI instability is not the dominant degradation mechanism at this stage. Instead, the variations observed may arise from inhomogeneous slurry dispersion or partial loss of electrical contact with the current collector—both potential effects of manual anode preparation. Despite these artifacts, the NG.Cu anode provides a valid baseline to assess the stabilizing influence of the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings on NG/Cu anodes, as shown in Figure 9b,c.

It is important to note that the reduced reversible capacity observed for LIBs with the UNCD- and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes does not originate from the mass of the UNCD or N-UNCD films, which represents <0.5 wt% of the total anode. Instead, the capacity decrease is consistent with transport limitations imposed by the UNCD and N-UNCD layers, which act as a dense, sp3-rich interfacial barrier that partially restricts Li+ diffusion and increases interfacial resistance. Similar effects have been reported in Si-based anodes, where surface coatings or rigid interfacial layers lead to apparent capacity losses not due to active-material weight but due to impeded ionic transport or constrained volume changes [31,32]. In those studies, coatings altered the interfacial transport kinetics and mechanical freedom of the anode, affecting the accessible capacity while simultaneously improving structural stability. Likewise, the objective of the present research was not to maximize specific capacity but to investigate the interfacial stability, SEI evolution, and impedance behavior induced by the ultrathin UNCD and N-UNCD coatings.

In contrast, the UNCD- and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes demonstrate superior capacity retention and more stable charge–discharge profiles over prolonged cycling. This improvement indicates that the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings contribute to surface stabilization, mitigating interfacial degradation and suppressing uncontrolled SEI growth.

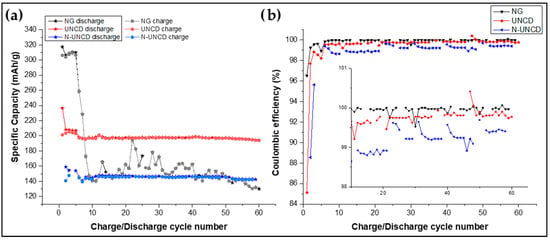

Figure 10a shows the specific capacity as a function of the number of charge/discharge cycles during the first five cycles, involving formation of the SEI layer, enabling stabilization of the anode.

Figure 10.

(a) Specific capacity and (b) Coulombic efficiency for LIBs with NG/Cu and UNCD and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes.

After cycle 5, the charge current was calculated based on the full-charge capacity within one hour (C-rate), and, for the remainder of the cycling process, the current was maintained at C/10 to ensure cycling under controlled conditions.

The half-cells LIBs with UNCD and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes demonstrate greater capacity retention and stability compared to the LIBs with NG/Cu anode. The LIB with UNCD/NG/Cu anode and Li cathode exhibits the highest specific capacity, averaging around 195 mAh/g. The LIB with N-UNCD/NG/Cu anode and Li cathode follows with a capacity of approximately 145 mAh/g. In contrast, the LIB with NG/Cu anode and Li cathode exhibits a sharp capacity drop at cycle 5, followed by fluctuations between 140 mAh/g and 195 mAh/g after cycle 10, indicating instability in capacity retention.

Figure 10b displays the Coulombic efficiency of the LIB cells. While all three LIB cells exhibit efficiency values ranging between 98.5% and 100%, the LIB half-cell with N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode shows a cyclic dependency in its efficiency. This behavior is attributed to the testing protocol, where the cells were periodically removed for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements every 10 cycles. Interestingly, this cyclic variation is not observed in the LIB half-cells with NG/Cu or UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes, suggesting that the presence of nitrogen in N-UNCD may be influencing this behavior.

The Coulombic efficiency (CE) of the UNCD- and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes remains comparable to that of bare NG/Cu anodes throughout charge/discharge cycling, indicating that the UNCD and N-UNCD films do not introduce parasitic reactions with Li+. The voltage profiles of the coated anodes exhibit only the characteristic lithiation/delithiation plateaus of graphite, with no additional redox features. These observations confirm that the UNCD and N-UNCD layers are electrochemically inert within the operating potential window and primarily act as mechanically and chemically stabilizing interfacial barriers rather than participating in Faradaic processes.

While this study provides clear comparative evidence of stabilization effects introduced by the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings, we acknowledge that the analysis is based on single representative half-cells per configuration. The absence of replicate cells prevents formal statistical treatment of variance. Future work will incorporate full statistical replicates to quantify variability and confidence intervals.

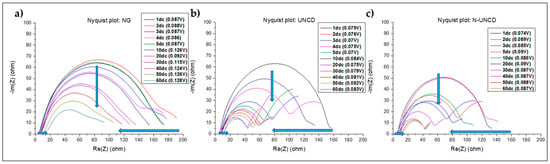

3.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Analysis

EIS is widely used in the study of batteries among other fields because it measures the internal behavior of the charges in a large range of frequencies, allowing for the deconvolution of physical-chemical behavior in different time scales [18].

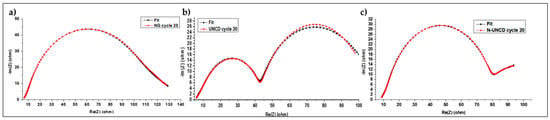

Electrochemical impedance spectra were collected for all LIBs with samples after every 10 cycles. Figure 11 shows the corresponding plots for each sample, and, as can be seen from the arrows, all the samples show an increase in contact ohmic resistance (small arrow to the right on the x-axis), decrease in overall impedance (vertical arrow on the Y-axis) and decrease in overall impedance (long arrow on the x-axis). For sample NG the drop is not continuous but irregular. The methodology employed to interpret the EIS data was the Distribution Relaxation Time and corroborated the Electric Circuit Model.

Figure 11.

Electrochemical impedance spectrum at several discharge cycles (dc) for (a) LIB with NG/Cu anode, (b) LIB with UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode, and (c) LIB with N-UNCD-coatex NG//Cu anode.

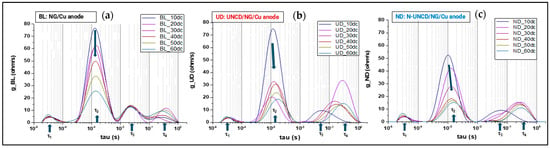

3.4. Distribution Relaxation Time (DRT) Measurements

This technique utilizes electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) as input and calculates the probability of a dominant process occurring at a specific frequency. This approach helps to better understand the contributions of each anode and the electrolyte, particularly in relation to the Nyquist plot arcs in an EIS spectrum [1,33,34].

The impedance data measured in the frequency domain are deconvoluted to fit the following equation:

where is the Ohmic resistance, is the relaxation time distribution function, is the imaginary unit, is the frequency, and is the time constant. The relationship between and is given by the following:

Impedance data are typically acquired on a logarithmic scale, leading to the following expression [18,35]:

where , making an alternative representation of the relaxation time distribution function.

Once has been determined, the distribution function can be used to interpret various phenomena associated with the inherent electrochemical processes in lithium-ion cells, including the number of processes involved and their variations over time [36].

The peak-based representation of enables the differentiation of distinct processes occurring at various time constant values () [37]. Consequently, the area under each specific peak corresponds to the impedance contribution of the underlying process [36], determined by integrating within a specific time constant range [τinitial, τfinal] as shown in Equation (4).

The DRT peak contributions are critical for identifying the primary electrochemical processes and degradation mechanisms occurring within the cells [13]. Additionally, DRT profiles provide valuable insights into anode behavior and their impact on overall cell performance.

The DRT spectra for all three half-cell configurations, Figure 12, —NG, UNCD, and N-UNCD—show four main relaxation regions, corresponding to the characteristic time constants τ1 through τ4. These peaks represent, respectively, electronic transport (τ1), ionic transport in the electrolyte (τ2), SEI-related processes (τ3), and lithium intercalation into graphite (τ4). While the overall spectral structure remains consistent across samples, the evolution of peak amplitude and position throughout the 10–60 charge/discharge cycle range reveals distinct stability trends associated with each anode configuration.

Figure 12.

Shows the DRT plots for (a) reference NG, (b) UNCD and (c) N-UNCD samples, each for charge/discharge cycles 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60.

For the reference NG/Cu, the DRT profiles evolve noticeably with cycling: the τ3 peak broadens and shifts toward longer relaxation times, while the τ4 peak becomes less defined after 40 cycles. This behavior reflects the progressive increase in interfacial resistance and the degradation of the anode–electrolyte interface, consistent with SEI thickening and non-uniform charge transport during extended operation [10,38,39].

In contrast, the UNCD-coated NG/Cu exhibits narrower and more stable peaks throughout all measured charge/discharge cycles. The τ3 contribution remains constant in position and intensity, indicating that the UNCD coating effectively suppresses SEI growth and preserves interfacial uniformity. The τ4 peak also remains stable, suggesting sustained lithium intercalation kinetics and a uniform charge-transfer environment. These results support the notion that the UNCD layer acts as a chemically inert and mechanically robust barrier that enhances electrochemical stability.

The N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode shows an intermediate behavior. During the initial cycles, the τ3 peak appears at slightly longer relaxation times with higher intensity, implying greater interfacial resistance likely associated with nitrogen-induced structural disorder. However, from cycle 20 onward, both the τ3 and τ4 peaks gradually converge toward the stable profiles observed for the LIB with UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode. This behavior indicates that the N-UNCD coating undergoes electrochemical self-stabilization, where initial heterogeneities reorganize into a more conductive and stable interface [15,22].

Although the coated anodes exhibit no additional peaks, the partial overlap between τ3 and τ4 required Gaussian deconvolution to resolve their individual contributions accurately, as described by Equation (4). This analysis confirmed that the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings significantly reduce the SEI-related resistance component (τ3) while maintaining similar lithium intercalation characteristics (τ4) to those of the uncoated NG/Cu anodes.

Overall, the DRT results presented in Figure 12 confirm that the diamond coatings preserve the fundamental electrochemical architecture of the system while improving interfacial stability. The consistent number of relaxation peaks and the reduced variation in τ3 and τ4 over time demonstrate that UNCD and N-UNCD coatings effectively suppress SEI growth, stabilize charge-transfer pathways, and maintain the characteristic relaxation behavior of the graphite–electrolyte system, thereby enhancing the long-term electrochemical performance of the anode.

3.5. Electric Circuit Model (ECM)

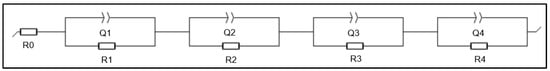

The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of the three half-cells were fitted using an equivalent circuit model (ECM) comprising four RQ elements connected in parallel, each representing a distinct electrochemical process, in series with a resistive element (R0) corresponding to the uncompensated ohmic resistance. The proposed model, shown in Figure 13, effectively reproduces the experimental Nyquist responses of all LIBs half-cells.

Figure 13.

Model of equivalent electrical circuits for all half-cells.

Fitting was performed using EC-Lab v11.50 (Bio-Logic, Claix, France) (Figure 14), and the corresponding parameters were extracted for each RQ element, including the phase constant (a) (Table 5). The time constants (τ = RC) derived from these parameters were then analyzed and compared among the NG, UNCD, and N-UNCD configurations.

Figure 14.

Equivalent electrecial circuit fit of Nyquist data for (a) NG, (b) UNCD and (c) N-UNCD electrodes after 20 charge–discharge cycles.

Table 5.

Equivalent electrical circuit fits for all half-cells LIBs.

Representative ECM fitting results for cycle 20 are summarized below, highlighting characteristic resistances and capacitances for each process:

The ECM results confirm the presence of four distinct electrochemical processes across all half-cells LIBs, with characteristic time constants on the order of 10−5 s, 10−3 s, 10−2 s, and 10−1 s. These processes correspond, respectively, to electronic transport within the anode, ionic migration through the electrolyte, solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) dynamics, and lithium-ion intercalation into graphite. The model thus provides quantitative validation of the DRT-derived analysis and reinforces the physical interpretation of the time-constant (τ) distributions obtained from impedance deconvolution. It is just important to consider that the values differ up to one order of magnitude, due to the nature of the techniques [38].

3.6. Internal Resistance Modeling and Analysis

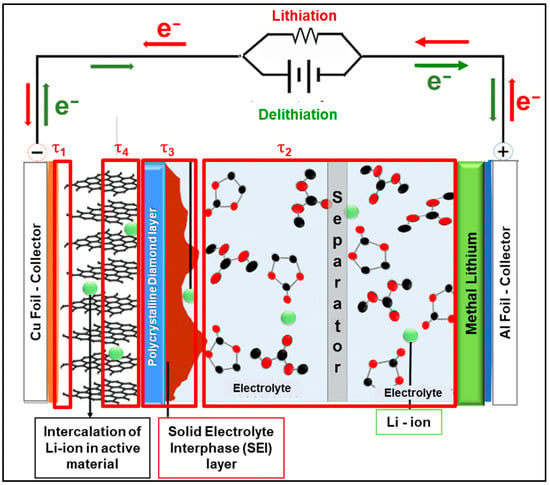

To interpret the plots, it is important to present a model based on the physical properties of the cell corroborated by the literature.

To facilitate the discussion by having a graphical support, Figure 15 shows a generic representation of the half-cell used for this study. The first section (with time constant τ1) depicts the area for electronic transport, which occurs from the current collector (copper foil) passing through the anode paste (80% natural graphite, 10% Acetylene Black and 10% pdf binder). This section also has dielectric properties, causing a capacitive response. The second section (with time constant τ4) depicts the area of ionic intercalation of the Li+ in graphite. The third section (with time constant τ3) is the area of SEI formation, which combines with UNCD or N-UNCD. The fourth section (with time constant τ2) is the area of ionic transport of Li+ through the electrolyte, which has resistive and capacitive characteristics. It is assumed that Li+ comes from Li metal.

Figure 15.

Physical model of the internal composition of the half-cell LIB as hypothesized.

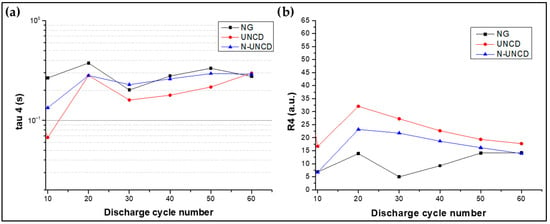

3.6.1. Tau 1—Electronic Transport in the Anode

The first relaxation time constant, τ1, corresponds to electronic transport processes occurring at the anode and current collector interface. As shown in Figure 16a, τ1 remains nearly constant across cycles for all samples, with values around 4 × 10−5 s. According to the literature [13,33,40], this time scale is typically associated with electronic conduction through the copper current collector and the conductive carbon network within the anode. Figure 16a shows the extracted characteristics time for tau 1 vs. discharge cycle for all the all the anodes.

Figure 16.

(a) Tau 1 vs. cycle for all the samples (b) corresponding resistance (Equation (4)).

As illustrated in Figure 16a,b, all samples exhibit a similar trend with slight decrease in resistance with increasing discharge cycle numbers. N-UNCD exhibits a modest downward trend relative to NG and UNCD; however, in the absence of replicate cells and formal uncertainty analysis, we consider this difference suggestive rather than statistically significant.

3.6.2. Tau 2—Ionic Transport Through the Electrolyte

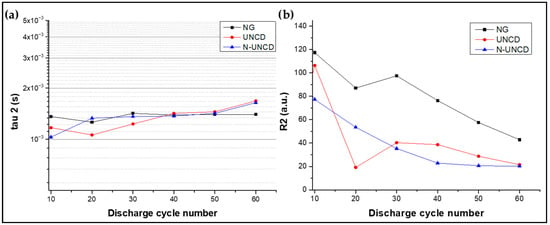

Figure 17a shows the charge-transfer resistance (Rₜ) values extracted from equivalent circuit fitting of the impedance spectra, while Figure 17b presents the total resistance (R_DRT) obtained by integrating the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) related to tau 2.

Figure 17.

(a) Tau 2 vs. cycle for all the samples, (b) corresponding resistance (Equation (4)).

The characteristic time constant τ2 corresponds to the ionic transport within the electrolyte, particularly through the separator region connecting the graphite-based working anode and the metallic lithium counter electrode (cathode. This process governs the migration of Li+ between both electrodes and typically manifests within the 10−3–10−2 s range in the DRT spectra, representing the intermediate frequency regime of the impedance response [38,39].

It is important to point out that this time constant does not arise from a double-layer capacitance at the electrode–electrolyte interface but instead originates from the bulk electrolyte. Within the electrochemical cell, two electrodes—the graphite anode and the lithium counter electrode (cathode)—define a confined ionic region filled by an electrolyte that possesses both a characteristic dielectric constant (ε) and a non-ohmic resistive response. Thus, the τ2 relaxation time reflects the dielectric relaxation and ion mobility phenomena occurring inside the electrolyte volume, rather than surface charge accumulation at the electrode interfaces.

This interpretation is consistent with previous studies reporting that the intermediate relaxation regime in lithium-ion systems primarily arises from bulk electrolyte polarization and displacement processes, rather than purely interfacial double-layer effects [13,39,41]. Accordingly, τ2 captures the collective response of Li+ oscillating under the alternating electric field applied during electrochemical impedance measurements, a behavior governed by the intrinsic ionic conductivity, viscosity, and dielectric properties of the electrolyte medium.

Throughout the cycling sequence (10–60 cycles), τ2 exhibited a gradual decrease in both magnitude and integrated resistance (Rᵢ), indicating a possible change in the effective ionic conduction pathway. Such variations may be attributed to morphological modifications or the onset of dendritic growth at the lithium counter electrode, which effectively shortens the ionic path length or locally alters the electric field distribution within the cell. Since this trend was consistently observed across all three configurations—reference (NG), UNCD-coated NG/Cu, and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu—it can be concluded that the τ2 process is primarily dictated by the electrolyte’s inherent physical properties, remaining largely unaffected by surface modifications on the graphite layer introduced by the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings.

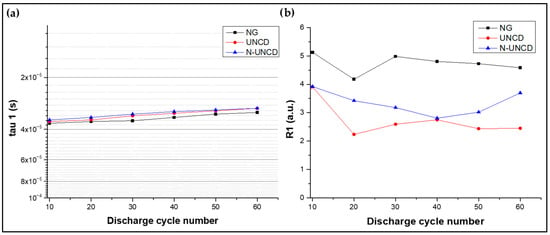

3.6.3. Tau 3—Electrical Properties of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI)

Figure 18a shows the charge-transfer resistance (Rₜ) values extracted from equivalent circuit fitting of the impedance spectra, while Figure 18b shows the total resistance (R_DRT) obtained by integrating the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) related to τ3.

Figure 18.

(a) Tau 3 vs. cycle, (b) calculated resistance vs. cycle (Equation (4)).

The time constant τ3 is directly associated with the electrical properties of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), a nanometric layer that forms at the anode–electrolyte interface during the initial charge–discharge cycles of a lithium-ion cell. The SEI plays a dual role: it stabilizes the anode surface by preventing continuous electrolyte decomposition, yet it also consumes active lithium and electrolyte, contributing to irreversible capacity loss. In the analyzed cells, τ3 consistently appeared within the 10−2–10−1 s range, corresponding to characteristic SEI formation and evolution processes [13,21,39].

Notably, the τ3 peak intensity and its integrated resistance (Ri) were significantly reduced for both UNCD- and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes in the LIB half-cells compared to the reference NG/Cu anode, indicating that the presence of the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings modifies the interfacial dynamics of SEI formation. This trend suggests that the coatings suppress or stabilize SEI growth, potentially by creating a more uniform and chemically inert interface. Such behavior is consistent with the literature reports where nanostructured or carbon-based protective layers effectively reduce interfacial impedance and improve long-term cycle stability [13,21].

Importantly, the τ3 trends for the UNCD and N-UNCD coated anodes diverge from those of the NG/Cu anode performance, reflecting a distinct interfacial response. These results confirm that the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings do not act as active lithium storage media—the lithium intercalation process occurs exclusively within the NG component. Instead, the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings primarily enhance electrical contact stability and improve the mechanical integrity of the anode–collector interface, minimizing degradation under repeated charge/discharge cycling.

This interpretation is supported by the voltage versus specific capacity profiles shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, where no additional plateaus are observed for the UNCD- or N-UNCD-coated anodes in half-cells LIBs. The absence of such features indicates that no secondary lithiation process is associated with the UNCD or N-UNCD layer, confirming that the observed electrochemical effects are purely interfacial rather than bulk storage phenomena. Furthermore, this conclusion is corroborated by the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) analysis (Figure 12), where it is evident that the addition of UNCD or N-UNCD layers does not result in an extra peak corresponding to an additional interface, thus confirming the absence of another electrochemical process beyond the intrinsic responses of the graphite–electrolyte system. The physical (capacitive and resistive) properties of the diamond coatings are in parallel with those of the SEI, as found out with the XPS analysis.

Additionally, while both UNCD and N-UN CD coated NG/Cu anodes exhibit lower τ3-associated resistances than the uncoated NG/Cu anode, the N-UNCD coating, initially induces a higher τ3 resistance, which progressively decreases with charge/discharge cycling. This behavior may result from nitrogen incorporation into the grain boundaries, introducing sp2-rich conductive regions that initially interfere with uniform SEI formation but eventually stabilize as the interface reorganizes over successive cycles [14,21,22]. The presence of the UNCD and N-UNCD coating does not mechanically hinder the electrochemical behavior of the NG/Cu anode. The NG layer experiences only marginal volume changes upon lithiation (≈8–10%), unlike Si-based materials that undergo changes in several hundred percent. Consequently, the ultrathin (~70 nm) UN CD and N-UNCD layers do not constrain the structural breathing of the graphite, and no signs of mechanical trapping, layer delamination or capacity fading associated with volumetric restriction were observed. Similar considerations have been reported by Sattari et al. and Quiroga et al. [31,32] for Si wires coated with rigid layers, where coatings can impede expansion and reduce capacity; however, this effect is absent in graphite due to its intrinsically low volumetric strain. The role of the UNCD and N-UNCD layers is therefore interfacial stabilization rather than mechanical confinement.

3.6.4. Tau 4—Lithium Intercalation into Graphite

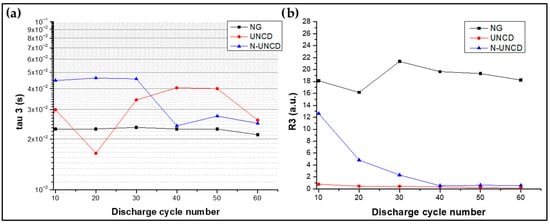

Figure 19a shows the charge-transfer resistance (Rₜ) values extracted from equivalent circuit fitting of the impedance spectra, while Figure 19b presents the total resistance (R_DRT) obtained by integrating the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) related to τ4. The time constant τ4 corresponds to the charge-transfer and lithium intercalation process within the graphite structure, representing the slowest and most kinetically dominant step in the electrochemical response of the half-cell. This relaxation regime typically appears at low frequencies, within the 10−1–100 s range, and occurs previous to the diffusion of Li+ across the graphite galleries and the subsequent formation of staged graphite–lithium compounds (LiC6–LiC12) [13,39].

Figure 19.

(a) Tau 4 vs. cycle, (b) calculated resistance vs. cycle (Equation (4)).

For the reference NG/Cu anode, the DRT spectra show a pronounced τ4 peak whose magnitude increases progressively with charge/discharge cycling, accompanied by a shift toward longer relaxation times. This trend reflects a decrease in lithium diffusivity and an increase in charge-transfer resistance at the anode–electrolyte interface. Such behavior can be attributed to the thickening of the SEI and the gradual loss of electronic connectivity between graphite particles after multiple lithiation/delithiation cycles, as reported in similar systems [21,39].

In contrast, the UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode exhibits a significantly smaller τ4 peak and a stable relaxation time throughout all tested cycles. The constancy of this response indicates that the UNCD layer promotes efficient electron transport and uniform Li+ diffusion into the underlying graphite structure. The chemical inertness and high sp3-bonded density of the UNCD film likely reduce parasitic reactions at the surface, preventing localized polarization and thereby sustaining the electrode’s kinetic uniformity over prolonged operation.

The N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode initially presents a slightly higher τ4 resistance compared to UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode, likely due to nitrogen-induced grain boundary disorder and localized variations in electronic conductivity. However, this behavior gradually stabilizes after approximately 20 cycles, as evidenced by the reduced τ4 peak intensity and its convergence toward the UNCD profile. This evolution suggests a self-healing or stabilization process of the nitrogen-incorporated grain boundaries, where sp2-enriched domains reorganize into continuous conductive pathways that facilitate charge transfer and Li+ insertion [15,22].

When comparing all three anode configurations, it becomes evident that the UNCD and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode exhibit slower degradation of τ4 with cycling, demonstrating that both coatings preserve the electrochemical accessibility of the graphite domains. Moreover, the absence of any additional peaks in the DRT spectra (as shown in Figure 12) reinforces that neither coating introduces new interfacial reactions or secondary storage mechanisms; instead, their effect is limited to improving the structural and electronic stability of the active electrode surface.

In summary, τ4 reflects the fundamental lithium intercalation kinetics within graphite, and its evolution across cycles serves as a sensitive indicator of anode stability. The reduced τ4 resistance and stable relaxation profile observed for the UNCD and N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anodes confirm that the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings enhance charge-transfer uniformity, suppress degradation of diffusion pathways, and maintain the long-term electrochemical integrity of the graphite anode.

This behavior is consistent with the interfacial stability reported for UNCD coatings, which remain chemically inert, mechanically robust, and strongly adherent under repeated cycling, preventing SEI disruption and surface degradation [12].

A limitation of this study is the use of single half-cells per experimental condition. Although fabrication of additional UNCD- and N-UNCD-coated cathodes was not feasible due to equipment constraints, the fabrication protocol has demonstrated high reproducibility in previous works from our group. Consequently, the conclusions emphasize comparative behavior rather than statistical dispersion. Future studies will expand this dataset to include replicates and error-quantified measurements.

4. Conclusions

The research described in this article demonstrated an evaluation of the effect of UNCD and N-UNCD coatings on the electrochemical performance of NG/Cu anodes for lithium-ion batteries. The results obtained from charge–discharge cycling, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT), and Equivalent Circuit Modeling (ECM) collectively demonstrate that the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings effectively enhance the stability and interfacial performance of the NG/Cu anodes.

The Potential-Specific capacity curves exhibited the typical plateaus associated with the LiC12 and LiC6 phase transitions, indicating normal lithium intercalation into graphite. Importantly, the UNCD and N-UNCD coated NG/Cu anodes in half-cells LIBs showed no additional plateaus, confirming that the coatings do not contribute to lithium storage but act as electrically and chemically inert protective layers. The coated NG/Cu anodes also exhibited smoother and more reproducible potential profiles even in the early formation during charge/discharge cycles (see Figure 8), confirming improved interfacial stability from the initial SEI development stage. After 60 cycles, the UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode exhibited the most stable performance, with a specific capacity of ~195 mAh/g and Coulombic efficiency close to 100%, while the N-UNCD-coated NG/Cu anode maintained ~145 mAh/g with similar efficiency. In contrast, the uncoated NG/Cu anode displayed greater capacity fluctuation and interfacial instability (140–195 mAh/g), attributed to the absence of surface passivation.

The DRT and ECM analyses confirmed four consistent relaxation processes: electronic transport (τ1), ionic transport through the electrolyte (τ2), SEI-related impedance (τ3), and lithium intercalation (τ4). The τ2 process remained nearly constant across all electrodes, confirming that the coatings did not modify bulk ionic transport. However, the τ3 and τ4 regions displayed distinct improvements for the coated samples. Both UNCD and N-UNCD coatings reduced SEI-related resistance (τ3) and stabilized charge-transfer kinetics (τ4), leading to lower impedance growth and enhanced electrochemical uniformity over cycling.

The UNCD coating demonstrated the most stable impedance evolution, with minimal change in τ3 and τ4 over 60 cycles, indicating superior suppression of SEI thickening and preservation of lithium diffusion pathways. The N-UNCD coating initially presented higher τ3 resistance, likely due to nitrogen-induced grain boundary disorder, but progressively self-stabilized after the first 20 cycles as the interface reorganized, improving electrical conductivity and SEI uniformity.

The DRT spectra (Figure 9) revealed no additional peaks for the UNCD and N-UNCD coated anodes, confirming that neither UNCD nor N-UNCD introduced extra electrochemical interfaces. Instead, the coatings stabilized existing processes by acting as chemically inert, mechanically robust interlayers. ECM fitting supported these observations, showing reduced overall resistance (RSEI + Rct) and consistent time constants for the coated electrodes compared to the uncoated reference.

Overall, the UNCD and N-UNCD coatings on NG/Cu anodes, particularly UNCD, significantly enhanced the electrochemical stability of graphite anodes. The coatings improved electrical contact between the active material and the current collector, limited SEI growth, reduced interfacial resistance and maintained efficient lithium intercalation behavior during extended cycling.

In conclusion, UNCD and N-UNCD coatings act as passive yet highly effective stabilizing layers, extending the operational life of NG/Cu anodes, currently used in most commercial LIBS, without altering their intrinsic electrochemical characteristics. The combined DRT–ECM approach proved essential in quantifying and isolating each interfacial process, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding and designing durable electrode–coating systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.-R., O.A. and E.d.O.; methodology, J.S.-R., E.Q.-G., O.A., D.V. and E.d.O.; software, J.S.-R.; validation, J.S.-R., and E.Q.-G.; formal analysis, J.S.-R., E.Q.-G. and E.d.O.; investigation, J.S.-R., E.d.O. and D.V.; resources, O.A., E.Q.-G. and E.d.O.; data curation, J.S.-R., E.Q.-G. and E.d.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.-R. and E.d.O.; writing—review and editing, D.V., E.Q.-G. and O.A.; visualization, J.S.-R. and E.d.O.; supervision, O.A., E.Q.-G. and E.d.O.; project administration, O.A.; funding acquisition, O.A. and E.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SENACYT (Panamá): grant number FID22-78, SNI funds for EdeO and a Master Scholarship for J.S.-R. O.A. acknowledges the support of the University of Texas through the Endowment chair.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Josefina Arellano, as well as the support of the personnel of the Laboratorio Pierre y Marie Curie at the Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mateos, M. Estudio del Efecto de los Microciclos en la Degradación de las Baterías de Iones de Litio; Universidad Pública de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peled, E.; Menkin, S. Review—SEI: Past, Present and Future. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A1703–A1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.; Carney, T.J.; Grimaud, A.; Giordano, L.; Pour, N.; Chang, H.-H.; Fenning, D.P.; Lux, S.F.; Paschos, O.; Bauer, C.; et al. Electrode—Electrolyte Interface in Li-Ion Batteries: Current Understanding and New Insights. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4653–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodenough, J.B.; Kim, Y. Challenges for Rechargeable Li Batteries. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. Electrochemical Performance of Porous Carbon/Tin Composite Anodes for Sodium-Ion and Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nie, P.; Ding, B.; Dong, S.; Hao, X.; Dou, H.; Zhang, X. Conductive ATO Nanocoatings Improving Stability and Rate Capability of Graphite Anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 16150–16158. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Lou, X.W. Metal Oxide Hollow Nanostructures for Lithium-ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S. A review on electrolyte additives for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2006, 162, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nie, P.; Ding, B.; Dong, S.; Hao, X.; Dou, H.; Zhang, X. Biomass Derived Carbon for Energy Storage Devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2411–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Pandey, R.K.; Li, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-H.; Peng, B.-L.; Huang, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-P. Nano Energy Conducting nitrogen-incorporated ultrananocrystalline diamond coating for highly structural stable anode materials in lithium ion battery. Nano Energy 2020, 74, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auciello, O.; Sumant, A.V. Diamond & Related Materials Status review of the science and technology of ultrananocrystalline diamond (UNCD TM) fi lms and application to multifunctional devices. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2010, 19, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-W.; Lin, C.; Chu, Y.; Abouimrane, A.; Chen, Z.; Ren, Y.; Liu, C.; Tzeng, Y.; Auciello, O. Electrically Conductive Ultrananocrystalline Diamond-Coated Natural Graphite-Copper Anode for New Long Life Lithium-Ion Battery. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3724–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Brivio, C.; Wood, V. Detection of Lithium-Ion Cells’ Degradation through Deconvolution of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy with Distribution of Relaxation Time. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2200547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, D.; Sharma, J.; Arellano-Jimenez, M.J.; Auciello, O.; de Obaldía, E. Growth of Nitrogen Incorporated Ultrananocrystalline Diamond Coating on Graphite by Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition. Materials 2022, 15, 6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kumtepeli, V.; Ludwig, S.; Jossen, A. Investigation of the distribution of relaxation times of a porous electrode using a physics-based impedance model. J. Power Sources 2022, 530, 231250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-gonzález, E.; Carstensen, J.; Föll, H. Structural and Electrochemical Investigation during the First Charging Cycles of Silicon Microwire Array Anodes for High Capacity Lithium Ion Batteries. Materials 2013, 6, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarascon, J.-M.; Armand, M. Issues and Challenges Facing Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, F.; Chen, C. Analysis of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data using the distribution of relaxation times: A Bayesian and hierarchical Bayesian approach. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 167, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, F.; De Angelis, A.; Moschitta, A.; Carbone, P.; Galeotti, M.; Cinà, L.; Giammanco, C.; Di Carlo, A. A guide to equivalent circuit fitting for impedance analysis and battery state estimation. J. Energy Storage 2024, 82, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Shin, H.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, J.; Yoon, W. Modeling and Applications of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Lithium-ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Parameter Estimation of Lithium-ion Batteries Using Distribution of Relaxation Times. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal, D.; Wittel, F.P.; Rajan, A.; Wittel, P.; Alcantar-Pena, J.; Auciello, O.; de Obaldia, E. Effect of nitrogen flow on the growth of nitrogen ultrananocrystalline diamond (N-UNCD) films on Si/SiO2/HfO2 substrate. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Engineering, Sciences and Technology Conference (IESTEC 2019), Panama City, Panama, 9–11 October 2019; pp. 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Ajikumar, P.K.; Srivastava, S.K.; Magudapathy, P. Structural, Raman and Photoluminescence Studies on Nanocrystalline Diamond Films: Effects of Ammonia in Feedstock. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.02664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 14095–14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, H.P. Surface oxides on carbon and their analysis: A critical assessment. Carbon 2002, 40, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.D.; Stock, S.R. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Cortés, D.; Janssens, S.D.; Fried, E. Controlling the Morphology of Polycrystalline Diamond Films via Seed Density: Influence on Grain Size and Film Texture. Carbon 2024, 228, 119298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulisch, W.; Petkov, C.; Petkov, E.; Popov, C.; Gibson, P.N.; Veres, M.; Merz, R.; Merz, B.; Reithmaier, J.P. Low Temperature Growth of Nanocrystalline and Ultrananocrystalline Diamond Films: A Comparison. Phys. Status Solidi A 2012, 209, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.N.; Steirer, K.X.; Hafner, S.E.; Ban, C.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Teeter, G. Operando X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of solid electrolyte interphase formation and evolution in Li2S-P2S5 solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.; Ghazvini, A.A.S.; Shahalizade, T.; Gaho, M.A.; Mumtaz, A.; Javanmardi, S.; Riahifar, R.; Meng, X.-M.; Jin, Z.; Ge, Q. A review of nitrogen-doped carbon materials for lithium-ion battery anodes. New Carbon Mater. 2023, 38, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Shree, S.; Neubüser, G.; Cardenasen, J.; Kienle, L.; Adelung, R. Corset-Like Solid Electrolyte Interface for Fast Charging of Silicon Wire Anodes. J. Power Sources 2018, 384, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-González, M.; Hansen, S. Si Microwire Anode with Enhanced Conductivity through Decoration with Cu Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Res. Rev. 2018, 1, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, T.S.; Kurra, N.; Wang, X.; Pinto, D.; Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Energy Storage Data Reporting in Perspective—Guidelines for Interpreting the Performance of Electrochemical Energy Storage Systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1902007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazem, M.E. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: The journey to physical understanding. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 2151–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, T.; Saccoccio, M.; Chen, C.; Ciucci, F. Electrochimica Acta In fl uence of the Discretization Methods on the Distribution of Relaxation Times Deconvolution: Implementing Radial Basis Functions with DRTtools. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 184, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.; Schindler, S.; Triebs, L.C.; Danzer, M.A. Optimized process parameters for a reproducible distribution of relaxation times analysis of electrochemical systems. Batteries 2019, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Brivio, C.; Carrillo, R.E.; Wood, V. Physics-Based SoH Estimation for Li-Ion Cells. Batteries 2022, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, J.; Novák, P.; Wagner, M.R.; Veit, C.; Möller, K.-C.; Besenhard, J.O.; Winter, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Vogler, C.; Hammouche, A. Ageing Mechanisms in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2005, 147, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, M.; Risse, S.; Wagner, N.; Friedrich, K.A. Investigation of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase Formation at Graphite Anodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries with Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 228, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzer, M.A. Generalized distribution of relaxation times analysis for the characterization of impedance spectra. Batteries 2019, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquert, J. Theory of the Impedance of Electron Diffusion and Recombination in a Thin Layer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 106, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).