Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett Monolayers from 20 nm Sized Crystals of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Cr)

Highlights

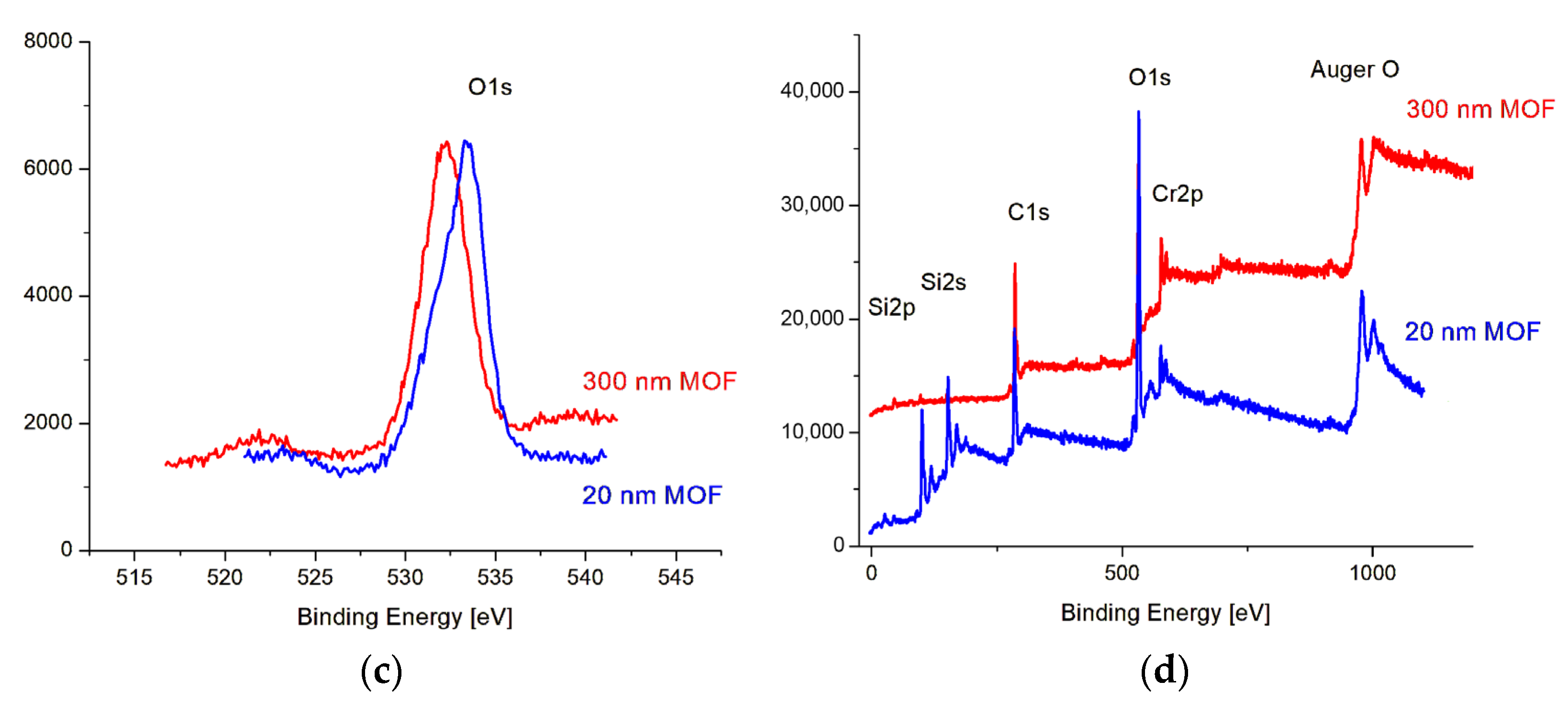

- A metal–organic Framework (MOF) MIL-101(Cr) with crystal sizes around 20 nm was synthesized and the results were compared to a 300 nm crystal-sized commercially available material.

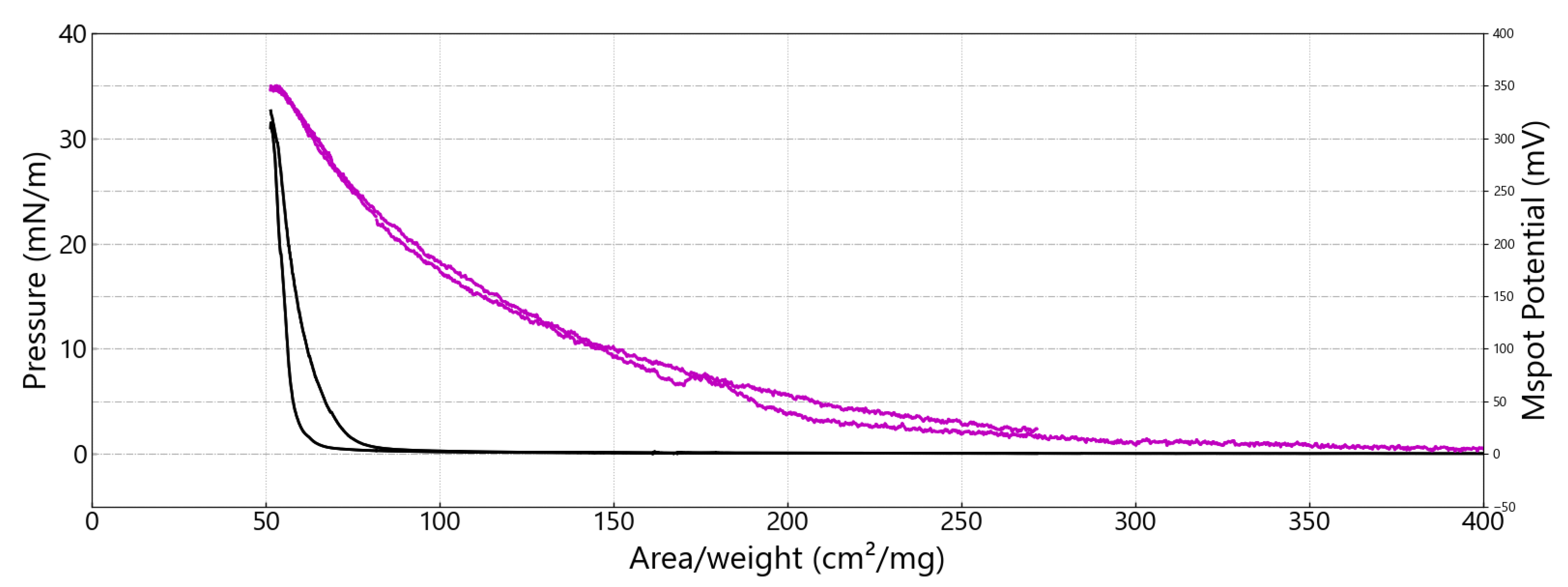

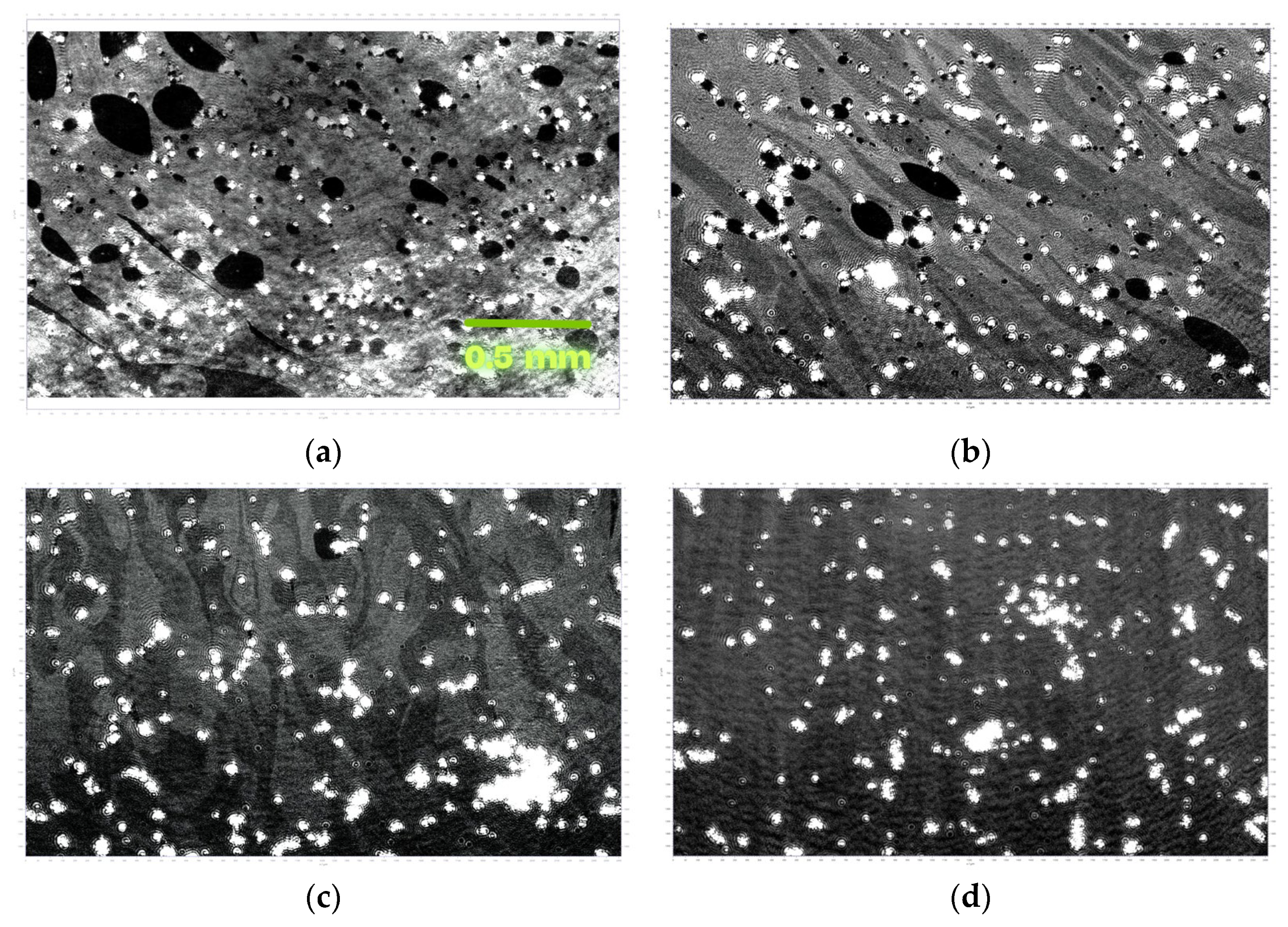

- Smaller-sized MIL-101(Cr) crystals form a stable insoluble monolayer at the air–water interface with denser, more homogeneous water coverage and packing upon compression, and no visible micrometer-sized aggregates.

- Langmuir-Blodgett monolayers from the 20 nm MOF show six times lower surface roughness.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Dispersion Preparation

2.3. Investigations at the Air–Water Interface and the LB Film Preparation

2.4. Other Instruments Used

3. Results and Discussion

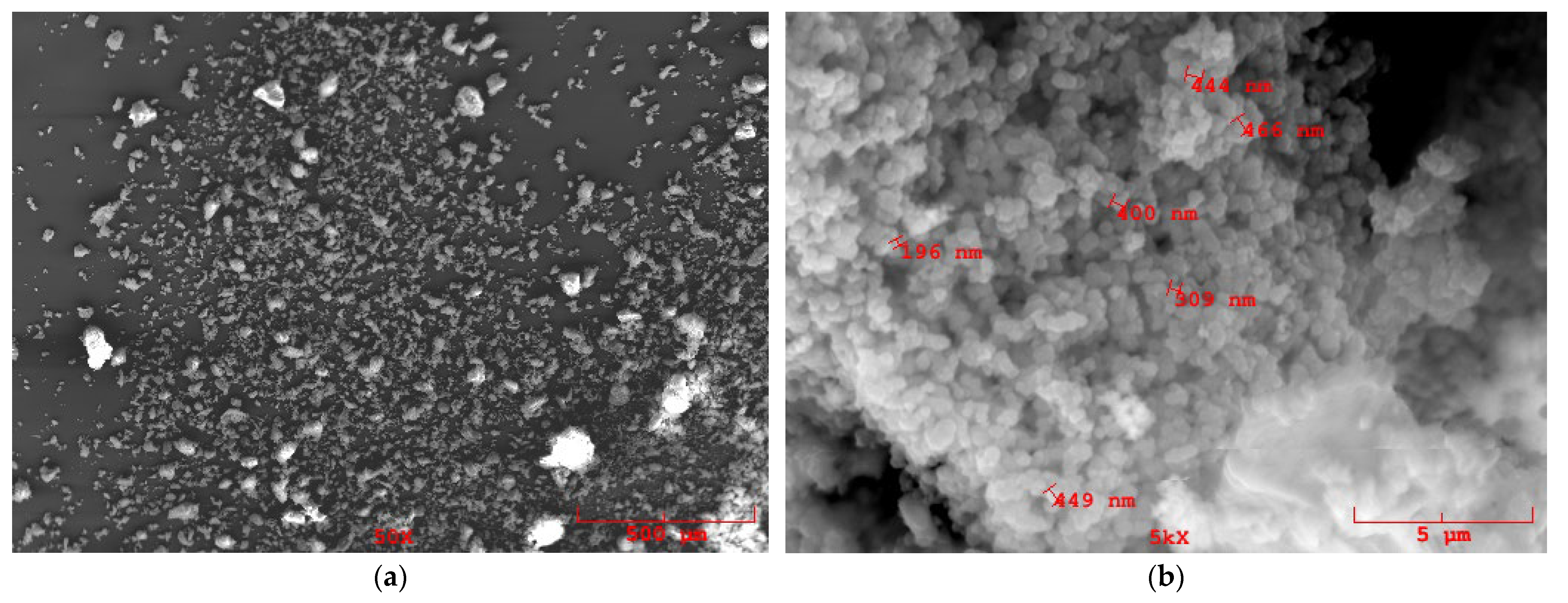

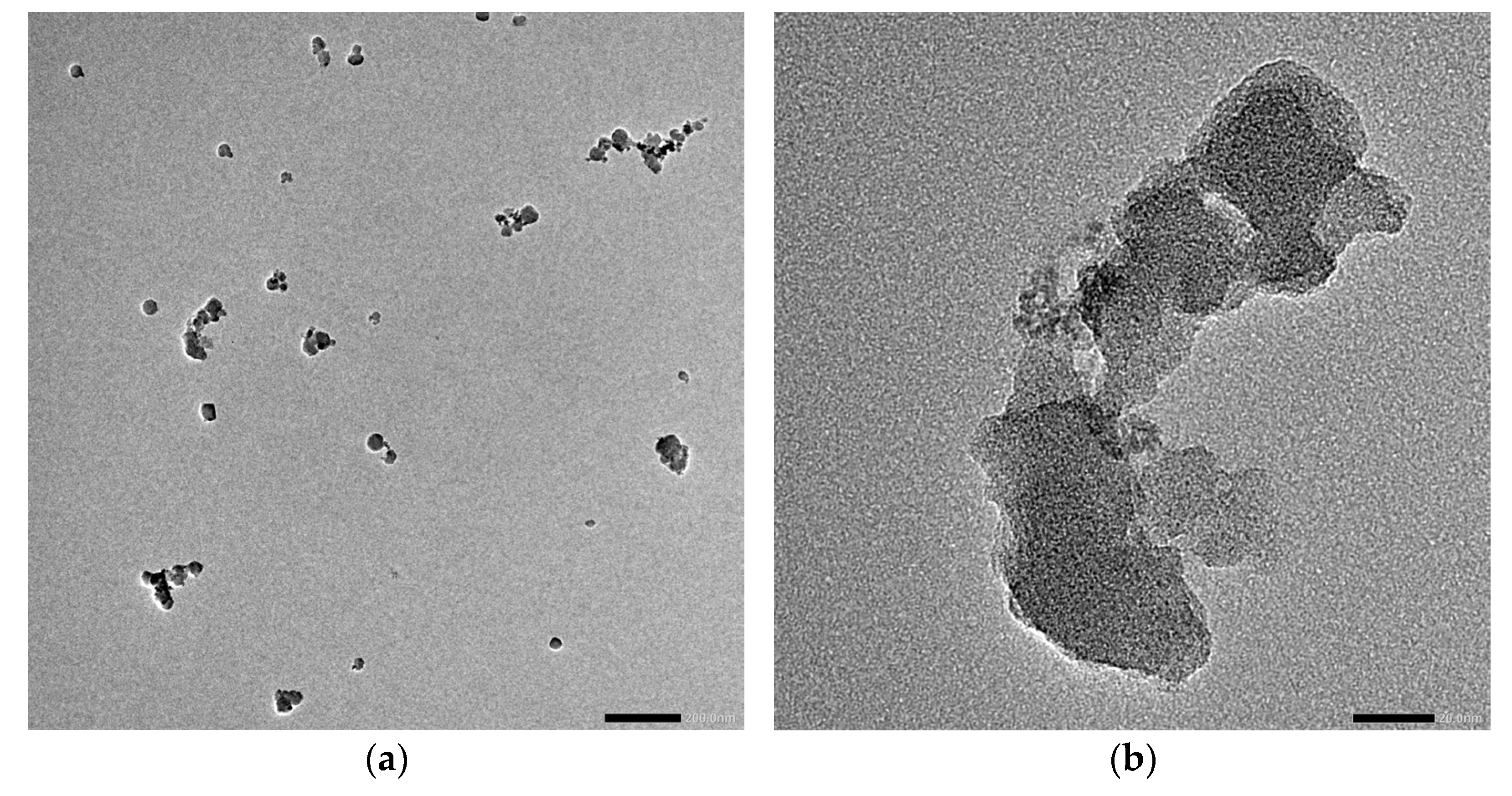

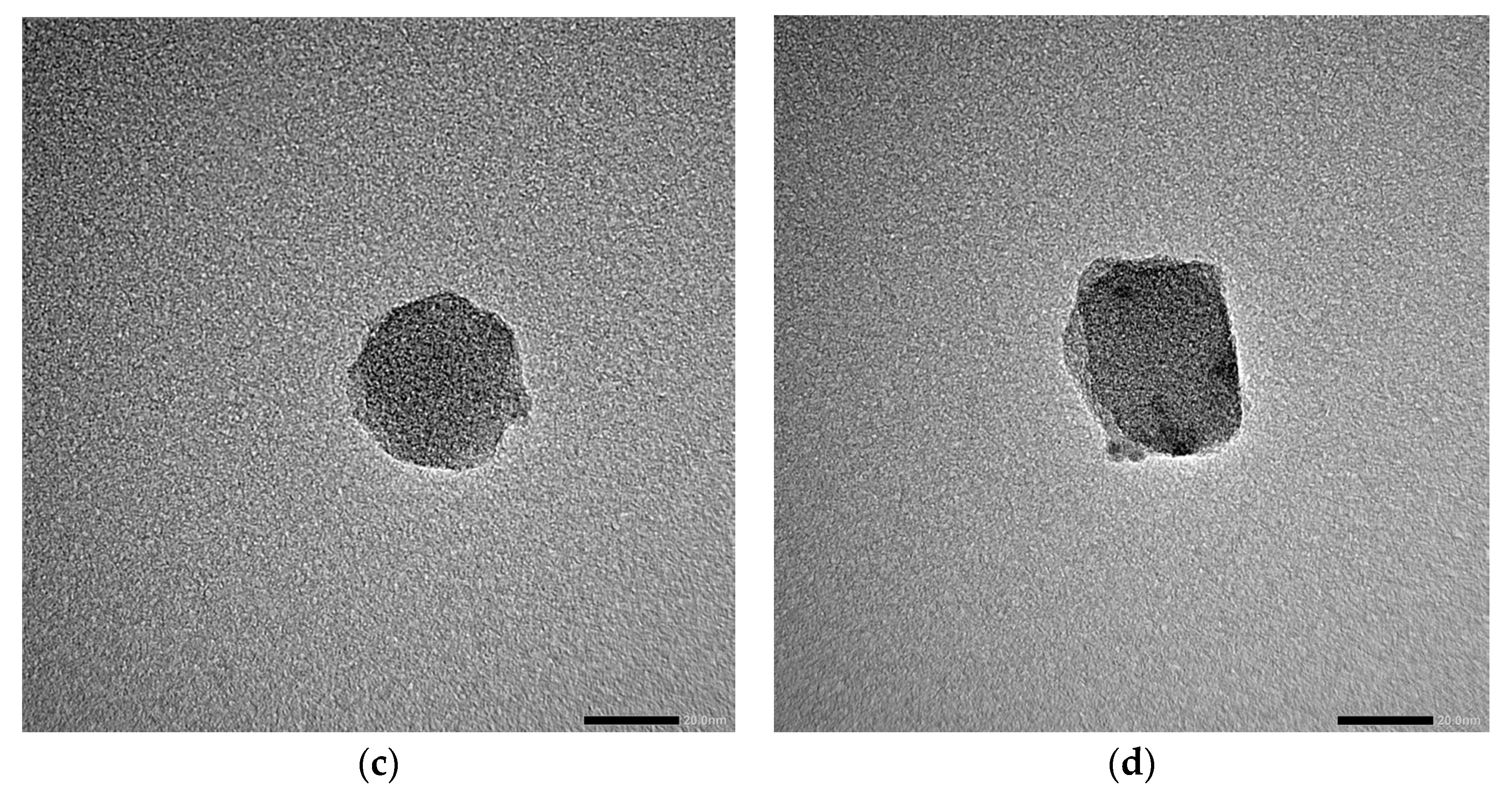

3.1. MOF Characterization

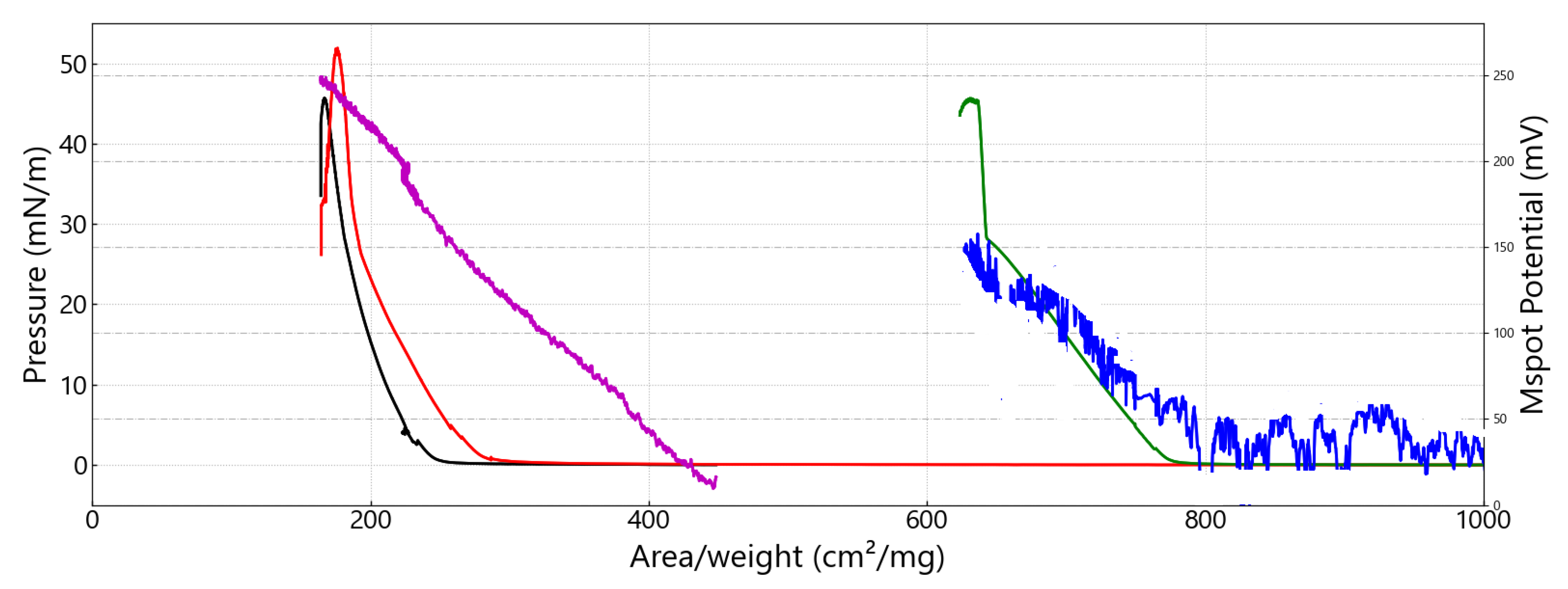

3.2. Investigations at the Air–Water Interface

3.3. LB Film Monolayers on Solid Support

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shams, M.; Niazi, Z.; Saeb, M.R.; Moghadam, S.M.; Mohammadi, A.K.; Fattahi, M. Tailoring the topology of ZIF-67 metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) adsorbents to capture humic acids. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115854–115866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Ma, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Yang, H. Three different configurations of MOFs constructed from 2,5-diketopiperazine-N, N’-diacetic acid for activating peroxymonosulfate (PMS) to degrade dyes and application in electrocatalysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1336, 142140–142151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-T.; Fan, X.-D.; Lu, J.-L.; Yang, Z.-H.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Wu, Y.-L.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Y. A novel porous Zn-MOF based on binuclear metal clusters for fluorescence detection of Cr(VI) and adsorption of dyes. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1322 Pt 3, 140553–140561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press Release: Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025. Nobel Prize Outreach; The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. 8 October 2025. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/press-release/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Makiura, R.; Konovalov, O. Interfacial growth of large-area single-layer metal–organic framework nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Walter, L.S.; Wang, M.; Petkov, P.S.; Liang, B.; Qi, H.; Nguyen, N.N.; Hambsch, M.; Zhong, H.; Wang, M.; et al. Interfacial synthesis of layer-oriented 2D conjugated metal–organic framework films toward directional charge transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13624–13632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bétard, A.; Fischer, R.A. Metal–organic framework thin films: From fundamentals to applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1055–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, J.; Sorribas, S.; Lucas, I.; Coronas, J.; Gascon, I. Langmuir–Blodgett films of the metal–organic framework MIL-101(Cr): Preparation, characterization, and CO2 adsorption study using a QCM-based setup. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 16486–16492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, J.; Fenero, M.; Sorribas, S.; Zornoza, B.; Msayib, K.J.; McKeown, N.B.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J.; Gascón, I. Fabrication of ultrathin films containing the metal organic framework Fe-MIL-88B-NH2 by the Langmuir–Blodgett technique. Coll. Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2015, 470, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, G.R.; Venelinov, T.; Marinov, Y.G.; Hadjichristov, G.B.; Terfort, A.; David, M.; Florescu, M.; Karakuş, S. First direct gravimetric detection of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) water contaminants, combination with electrical measurements on the same device—Proof of concepts. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.G. Langmuir–Blodgett Films; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4899-3718-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, M.C. Molecular Electronics: From Principles to Practice; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-470-72389-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, T.; Radev, D.; Ivanov, G.; Antonov, D.; Petrov, A.G. Hydrophobic Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis and LB Film Preparation. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2007, 9, 424–426. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbachev, I.A.; Smirnov, A.V.; Glukhovskoy, E.G.; Kolesov, V.V.; Ivanov, G.R.; Kuznetsova, I.E. Morphology of Mixed Langmuir and Langmuir–Schaefer Monolayers with Covered CdSe/CdS/ZnS Quantum Dots and Arachidic Acid. Langmuir 2021, 37, 14105–14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbachev, I.A.; Smirnov, A.V.; Ivanov, G.R.; Venelinov, T.I.; Amova, A.A.; Datsuk, E.V.; Anisimkin, V.I.; Kuznetsova, I.E.; Kolesov, V.V. Langmuir–Blodgett Films with Immobilized Glucose Oxidase Enzyme Molecules for Acoustic Glucose Sensor Application. Sensors 2023, 23, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Tang, M.; Nie, S.; Xiao, P.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y. Synthesis Methods, Performance Optimization, and Application Progress of Metal–Organic Framework Material MIL-101(Cr). Chemistry 2025, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabudeen, H.; Dong, R.; Feng, X. Interfacial Synthesis of Structurally Defined Organic Two-Dimensional Materials: Progress and Perspectives. Chimia 2019, 73, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuhadiya, S.; Himanshu; Suthar, D.; Patel, S.L.; Dhaka, M.S. Metal organic frameworks as hybrid porous materials for energy storage and conversion devices: A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214115–214140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; Kan, L.; Liu, Y. A three-dimensional Cu-MOF with strong π-π interactions exhibiting high water and chemical stability. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 99, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Dong, M.; Zhao, T. Advances in Metal–Organic Frameworks MIL-101(Cr). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, E.; Zeinali, S. Nanoporous MIL-101(Cr) as a Sensing Layer Coated on a Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Nanosensor to Detect Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 24103–24112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, E.; Zeinali, S. Formaldehyde Detection Using Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Nanosensor Coated by Nanoporous MIL-101(Cr) Film. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 300, 110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Metal-organic frameworks for QCM-based gas sensors: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 307, 111984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, A.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Viñas, P.; López-García, I.; Campillo, N. Advanced materials for magnetic solid-phase extraction of mycotoxins: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 178, 117826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ji, Y.; He, B.; Wang, M. Fabrication of novel mixed matrix composite membranes with polyethyleneimine-modified MIL-101 for CO2/CH4 separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 518, 164526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D.; Garai, B.; Reinsch, H.; Li, W.; Dissegna, S.; Bon, V.; Senkovska, I.; Kaskel, S.; Janiak, C.; Stock, N.; et al. Metal–organic frameworks in Germany: From synthesis to function. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 380, 378–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenmann, J.; Henninger, S.K.; Janiak, C. Water adsorption characteristics of MIL-101 for heat-transformation applications of MOFs. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 4, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Ding, X.; Hua, K.; Sun, A.; Hu, X.; Nie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; et al. Progress and Opportunities for Metal–Organic Framework Composites in Electrochemical Sensors. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 15442–15461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, G.; Song, Y. TPN-COF@Fe-MIL-100 Composite Used as an Electrochemical Aptasensor for Detection of Trace Tetracycline Residues. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 28148–28157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benseghir, Y.; Tsang, M.Y.; Schöfbeck, F.; Hetey, D.; Kitao, T.; Uemura, T.; Shiozawa, H.; Reithofer, M.R.; Chin, J.M. Electric-Field Assisted Spatioselective Deposition of MIL-101(Cr)/PEDOT to Enhance Electrical Conductivity and Humidity Sensing Performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 678, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Lv, D.; Guan, Y.; Yu, S. Post-Synthesis Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Xin, R.; Wang, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, R.; Liu, W. Machine learning: An accelerator for the exploration and application of advanced metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Deng, C.; Wu, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Machine Learning-Driven Sensor Array Based on Luminescent Metal–Organic Frameworks for Simultaneous Discrimination of Multiple Anions. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption. Official Journal of the European Union, L 435, 23 December 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS. United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 15 June 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/drinking-water-health-advisories-pfoa-and-pfos (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Yuan, M.; Ge, C.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Yin, C. Enhanced CO2 adsorption performance of amino-modified MIL-101(Cr–Al) materials: Synthesis, characterization, and mechanistic insights. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 64, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Luo, J.; Zhang, S.; Luo, X. Hierarchically mesostructured MIL-101 metal–organic frameworks with different mineralizing agents for adsorptive removal of methyl orange and methylene blue from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Kazemeini, M.; Mohammadi, A. A dual-functional Ni–MCr LDH nanostructure utilized for degradation of meropenem antibiotic pollutant: Synthesis and physicochemical characterizations toward development of a novel chemical mechanism. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férey, G.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Serre, C.; Millange, F.; Dutour, J.; Surblé, S.; Margiolaki, I. A chromium terephthalate-based solid with unusually large pore volumes and surface area. Science 2005, 309, 2040–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parak, P.; Nikseresht, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Emaminia, M.S. Application of MIL-101(Cr) for biofuel dehydration and process optimization using the central composite design method. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4625–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Tang, Y.; Liang, X.; Deng, T.; Peng, H.; Tian, J.; Du, J. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by Fe–TiO2/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposites under visible light. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zha, Q.; Zeng, L.; Zhu, M. Surfactant-assisted Cr–metal–organic framework for the detection of bisphenol A in dust from e-waste recycling area. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1146, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.K.; Kim, J.-H.; Kwon, H.T.; Kim, J. Cost-effective and eco-friendly synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) from waste hexavalent chromium and its application for carbon monoxide separation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 80, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, G.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Efficient treatment of smelting wastewater: 3D nickel foam @MOF shatters the previous limitation, enabling high-throughput selective capture of arsenic to form non-homogeneous nuclei. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 124927–124945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Albadarin, A.B.; Guo, C.; Annath, H.; Mangwandi, C. Solubility enhancement of BCS class II drugs via in-situ loading onto MIL-101(Cr) in a green solvent system. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2026, 380, 135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, I.D.; Ivanov, G.R. Layer by Layer Optimization of Langmuir–Blodgett Films for Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) Based Sensors for Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) Detection. Coatings 2022, 12, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Roughness from Scan Size 5 × 5 µm [rms] | Roughness from Scan Size 20 × 20 µm [rms] |

|---|---|---|

| Si69 | 110.9 nm | 603.7 nm |

| Si71 | 257.2 nm | 686.9 nm |

| Si72 | 88.7 nm | 123.4 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimov, A.; Ivanov, G.R.; Keil, L.; Terfort, A.; Liu, J.; Strijkova, V. Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett Monolayers from 20 nm Sized Crystals of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Cr). Coatings 2025, 15, 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121449

Dimov A, Ivanov GR, Keil L, Terfort A, Liu J, Strijkova V. Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett Monolayers from 20 nm Sized Crystals of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Cr). Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121449

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimov, Asen, George R. Ivanov, Leonard Keil, Andreas Terfort, Jinxuan Liu, and Velichka Strijkova. 2025. "Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett Monolayers from 20 nm Sized Crystals of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Cr)" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121449

APA StyleDimov, A., Ivanov, G. R., Keil, L., Terfort, A., Liu, J., & Strijkova, V. (2025). Langmuir and Langmuir–Blodgett Monolayers from 20 nm Sized Crystals of the Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Cr). Coatings, 15(12), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121449