Abstract

Ceramic bond grinding wheels were prepared and their performance in grinding Ni-based alloys was evaluated and compared in this study. Ceramic bond grinding wheels with excellent performance were successfully produced by optimizing the preparation process. Ceramic bond grinding wheels and conventional grinding wheels were used to grind Ni-based alloys, and the differences between the two were compared in terms of the surface quality of the workpieces after grinding. The results show that the ceramic bond grinding wheels exhibit significant advantages in improving the grinding surface quality, reducing the generation of grinding heat and extending the service life of the grinding wheels. In addition, the study also compares the differences in grinding force between the two grinding wheels and finds that the ceramic bond grinding wheel can significantly reduce the grinding force under the same processing conditions, thus improving the grinding efficiency and stability. Through systematic analysis, this paper determines the optimal processing parameters of ceramic bond grinding wheels in the process of grinding Ni-based alloys, which provides a theoretical basis and technical support for its application in actual processing.

1. Introduction

Ceramic bond CBN grinding wheels have a high chemical stability, good corrosion resistance, a high grinding accuracy, good self-sharpening of the grinding tool, a wide range of grinding adaptability, a high recycling rate after dressing, good maintenance of the shape of the grinding tool, and can meet the needs of most difficult-to-machine materials and general materials for high-precision grinding. The research, development, and application of ceramic bond grinding wheels have been receiving extensive attention in the world [1,2,3].

Wang et al. [4] introduced a laser fusion remelting technique to fabricate structured CBN grinding wheels. The impact-free trajectory was designed on the grinding wheel substrate, which can reduce the fluid friction in the channel and increase the fluid pressure at the outlet. The temperature and velocity fields of the grinding process were simulated to theoretically verify the feasibility of the designed structure. Wang et al. [5] designed an electroplated CBN grinding wheel and conducted abrasive grain size selection experiments and CBN wheel wear experiments on powder metallurgy superalloy FGH96 in sequence. The influence of the abrasive grain size of CBN grinding wheels and the wear state of the wheels on the surface morphology was investigated, respectively. The feasibility of grinding FGH96 with small-sized CBN grinding wheels is proved. Wang et al. [6] considered the bond rotational effect of the bond-based peridynamic method in order to study the progressive fracture evolution, stress characteristics, and fracture modes of CBN grains during this process. The peridynamic method has great potential in predicting the fracture mechanism of CBN grains during honing and wheel dressing processes. Vidal et al. [7] investigated the wheel morphology and wheel performance in the CFG process of electroplated silicon carbide (CBN) grinding wheels, detected the main types of wear, and proposed a method of measurement, followed by analyzing the effect of the conditioning process on the morphology change and power consumption during grinding before and after conditioning. Zhao et al. [8] prepared aggregated cubic boron nitride (cBN) abrasive grains using a high-temperature liquid phase sintering process and then performed single-grain scratch tests in order to investigate the abrasive wear behavior and material removal properties. The wear evolution of aggregated and single-grain cBN abrasive grains and the associated surface scratches were characterized, respectively. Lee et al. [9] prepared three silicon nitride specimens and two grinding wheels with boron carbide and diamond abrasives. The #325 cBN wheel showed excellent performance during rough grinding, while the #2000 diamond wheel exhibited efficient surface finishing performance, suggesting that the combination of these two abrasives can be effectively used for efficient and high-precision nano-surface machining of silicon nitride ceramics. Xu et al. [10] prepared specimens of glass-bonded cubic boron nitride (CBN) grinding wheels with controllable porosity by adjusting the content of the pore-forming agent dextrin and varying the forming pressure to investigate their performance in grinding camshafts. Dai et al. [11] illustrated the ultrasonic roller dressing mechanism of glass-bonded cubic boron nitride (VCBN) grinding wheels, and based on the geometrical and kinematic analyses, they established the number of collisions between the diamond dressers, and the CBN grit was modeled based on geometric and kinematic analysis. The effect of each dressing parameter on the collision number is analyzed and discussed. Ding et al. [12] also characterized the pore structure and tool wear morphology during the grinding of Ti-6Al-4V alloys. The grinding performance including grinding force and force ratio, tool wear evolution, and machined surface quality were discussed in detail. The results show that the open-hole cBN grinding wheels have desirable flexural strength and excellent chip storage space after optimizing the pore size of 0.6–0.8 mm and 40% of the design porosity.

Alloys have a wide range of applications in the manufacture of aviation jet engines and hot end components for various industrial gas turbines. Among them, nickel-based alloys are more widely used. Nickel-based alloys have excellent mechanical properties, but, in the process of grinding, processing brings certain difficulties. High grinding force, high grinding temperature, surface quality, and grinding accuracy are difficult to ensure [13,14,15].

Kon et al. [16] proposed a stable method for detecting the deterioration of cubic boron nitride (CBN) grinding wheels during cylindrical grinding using AE. The AE signal characteristics for CBN variation on the grinding wheel surface are used to estimate the surface roughness of the workpiece during the grinding process. Jiang et al. [17] comprehensively analyzed the grinding forces, surface morphology, and surface roughness when grinding 17CrNi2MoVNb alloy using an alumina grinding wheel and CBN grinding wheel. Ullah et al. [18] described the grinding performance of glass workpiece surfaces. The grinding wheel used consisted of cBN abrasive grains. It was confirmed that there is a large amount of randomness in the grinding mechanism, and the complexity of the workpiece surface increases gradually with the number of grinding cycles. Liu et al. [19] established a CBN wheel wear model for TC4 titanium alloy in longitudinal torsion ultrasonically assisted grinding, in order to explore the wheel wear law of TC4 titanium alloy in LTUAG and to improve the grinding efficiency and wheel life of TC4 titanium alloy. Vu et al. [20] investigated the effect of cutting parameters, including depth of cut, feed rate, and grinding wheel speed on grinding time when a cubic boron nitride wheel was used to grind a flake punch on a numerically controlled milling machine. Yin and Chen [21] conducted creep feed grinding tests on high-strength steels using SG and CBN grinding wheels. The grindability of high-strength steels was investigated in terms of grinding force, machining temperature, and specific energy of grinding. The excellent hardness and thermal conductivity of CBN abrasives are more effective than the high self-sharpening properties of SG abrasives in suppressing grinding burns and achieving a more favorable machining response. Zhang et al. [22] used CBN grinding wheels to characterize the grinding performance of laser-textured Ti-6Al-4V surfaces. The analysis included surface morphology and chemistry, grinding force, grinding force ratio, surface roughness, grinding temperature, and wheel wear. Naik et al. [23] investigated the wear of a single-layer plated cubic boron nitride grinding wheel while grinding Inconel 718 superalloy and reported the effect of the wear process on the wheel morphology. The radial wear of the grinding wheels was characterized by an early transient state, followed by a steady state of wear, and finally by a steel increase in the wear rate. Macerol et al. [24] explored the effect of CBN grit shape on the grindability of low-alloy chromium steel 100Cr6. A simple wheel–workpiece interaction model was introduced to study the grinding response. The model takes into account the overall grinding forces and includes all the properties of the grinding wheel acting at the interface. The research report by Ma et al. [25,26,27] investigated the mechanism of laser-assisted processing technology to improve the machinability of zirconia ceramics. The absorption rate of fiber laser energy by zirconia ceramics was obtained by a combination of experiments and simulations. This evidence and these studies can clearly explain the mechanism of laser-assisted polishing technology to improve the machinability of zirconia ceramics. Dai et al. [28] introduced surface topography measurement and modeling methods. Specific grinding forces and energies were modeled. The effect of thickness inhomogeneity of undeformed chips was investigated by grinding experiments. It was found that the specific grinding force increased as the mean value increased, the standard deviation (or coefficient of variation) decreased, and the percentage of active grains increased.

A number of researchers have conducted extensive studies on the preparation methods of grinding wheels, mainly focusing on the manufacturing process of conventional grinding wheels, covering methods such as metal-bonded grinding wheels, resin-bonded grinding wheels, and other common types of grinding wheel preparation methods. However, the scope of these studies is mainly limited to the traditional wheel preparation process, and the research on ceramic bond grinding wheels is relatively small. Ceramic bond grinding wheels have gradually become an important direction in the field of grinding processing due to their high hardness, thermal stability, and grinding efficiency, but the current research on the preparation process, performance optimization, and application of ceramic bond grinding wheels is still insufficient.

In order to solve this research gap, this paper discusses in depth the preparation method of ceramic bond grinding wheels and adopts an appropriate process route to improve the performance of the wheels, especially the advantages in grinding efficiency and durability, with respect to the characteristics of ceramic materials. In addition, this paper also compares and analyzes the performance differences between ceramic bond grinding wheels and conventional grinding wheels in the grinding process, focusing on their performance in terms of grinding force, grinding accuracy, and wear behavior under different processing conditions. Through systematic experimental research and data analysis, the potential of ceramic bond grinding wheels in efficient grinding and long service life is further revealed, providing a theoretical basis and technical support for their promotion in industrial applications.

Most previous studies on CBN grinding wheels have focused on wheel wear behavior, special wheel structures, or the grinding of other difficult-to-cut materials such as titanium alloys, high-strength steels or ceramics, and only limited work has been reported on nano-ceramic bond CBN wheels for nickel-based superalloys. In particular, systematic comparisons between nano-ceramic bond CBN wheels and conventional vitrified CBN wheels under identical grinding conditions for GH4169 are still scarce. Therefore, the present work aims to clarify the grinding performance of a nano-ceramic bond CBN wheel when machining GH4169 and to compare it directly with a conventional vitrified CBN wheel in terms of grinding forces, surface roughness, and microscopic surface integrity.

2. Grinding Wheel Preparation

Combined with the previous research of the research group, this study still adopts boron-aluminum silicate with excellent performance as the basic ceramic bond system, which is the SiO2-Al2O3-B2O3-R2O system. By constantly adjusting the proportion of nanomaterials in each substance in the formula and comparing the performance, we aim to obtain a high-performance nano-ceramic bond formula and lay a good foundation for the next step of grinding experiments. A ceramic bond with low refractoriness, high strength, and large porosity has been a difficulty of wheel preparation technology, but these conditions are the key to the wheel suitable for grinding nickel-based alloys, and our aim is to find a suitable method to improve the grinding quality.

After analyzing the properties of each substance in the boron-aluminum-silicate system. The nano-ceramic bond used in this work is based on a SiO2-Al2O3-B2O3-R2O glass system, which has been optimized in our previous studies and related literature to provide a suitable softening temperature, wettability, and mechanical properties for CBN abrasive grains [29]. The basic chemical composition of the ceramic bond (mass fraction, %) is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic chemical composition of the ceramic bond. (%, mass fraction) [30].

As shown in Table 2, the various major instruments and equipment used in the experiments for this project and their models are listed below:

Table 2.

Experimental apparatus and equipment.

The steps for ceramic bond preparation are as follows:

- (1)

- Bonding agent weighing and proportioning

According to the formulation of the ceramic bonding agent formula for the weighing of chemical reagents, the weighing process should be careful not to cause reagent contamination; excess reagents cannot be put back into the original reagent bottle. Note that after a large number of experiments, we concluded that due to this weighing ratio, we will only carry out the mixing of SiO2, Al2O3, and B2O3. This is because in the subsequent test, we will use the wet milling method for mixing. If Na2CO3 and Li2CO3 are introduced at the same time to achieve the final purpose of mixing, the drying process of these two substances will be precipitated in the form of large crystals. The final purpose of mixing would not be achieved.

- (2)

- Mixing

The purpose of ball milling is to ensure that all the chemical reagents can be evenly mixed. For the three substances in the binding agent, wet grinding will be used for ball milling, mixing the prepared materials with deionized water and corundum balls according to a certain ratio, and putting them into the ball milling tank for ball milling. The inert corundum balls used in this experiment have higher strength and better stability, and they are first cleaned with deionized water before use to prevent impurities from entering the ingredients and affecting the experimental results. In order to make the ball milling process more effective, the corundum balls selected are both big and small, so that the chemical reagent is milled more finely. Ball milling will occur for 12 h, with a material, deionized water, and corundum ball mass ratio of 1:2:4.

- (3)

- Pressing and molding

This experiment is carried out using a press bar machine for pressing. To ensure that the grinding tool is clean before pressing, each time 2.5 g of powder will be placed into the press bar grinding tool. With 60 kN pressure for pressing and a holding time of 60 s, the material will be pressed into a number of 37 × 5 × 6 rectangular pieces to be used for subsequent experiments. Another approximately 1.2 g of powder is put into a cylindrical mold, pressed with 30 kN pressure, with a holding time of 60 s, and pressed into a number of φ12 × 8 cylinders for subsequent measurement experiments.

- (4)

- Sintering molding

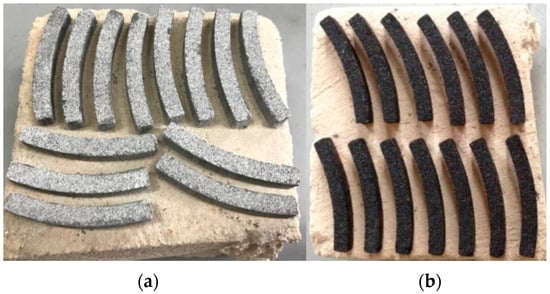

Sintering is a very important step in making ceramic tools. It enables the mechanical properties of the tool to be improved as well. In the sintering process, there will be a solid phase to the liquid phase, and then from the liquid phase to the solid phase of the transformation. This process will make the density of the material, the size of the grains and pores, and the distribution of pores and so on change, thus affecting the entire performance of the tool. The grinding wheel is sintered for 6 h in this study. The sintered specimens are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Grinding wheel strip after pressing; (b) sintered grinding wheel strips.

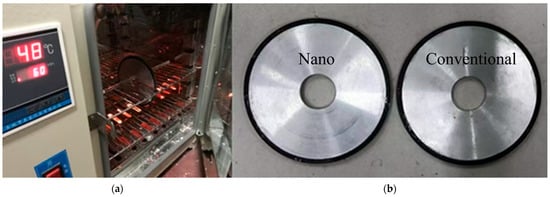

In the preparation of ceramic bond grinding wheels, the first step is to trim the ends of the sample strip. When trimming the diamond grinding wheel on the edge of each sample strip, grind until the two end surfaces are flat. Afterwards, the inner side of the sample patch is polished with sandpaper to remove the burrs produced during the sintering process and the particles left on the sample by the refractory bricks during the sintering process. Afterwards, the two kinds of AB adhesive are mixed in a ratio of 2:1. Because the curing speed of the binder is fast, it should be used in time after the binder is mixed. In addition, in order to improve the bonding accuracy and quality, the bonding is performed by placing the wheel substrate on a horizontal glass plate and then applying the binder to bond the patch to the substrate. Normal preparation of the sample patch is 36°, with the need for 10 patches to meet the demand, but, due to patch trimming and sintering shrinkage and other effects, the actual need is for more than 10. To be bonded on the glass plate after a period of time, after the wheel is suspended in the drying oven to accelerate the solidification rate, set the temperature to 60 °C, and a solidification time of 6 h. Figure 2a shows the drying box solidification state, and Figure 2b shows the preparation of the grinding wheel.

Figure 2.

(a) Drying box condensation state; (b) finished conventional and bonded grinding wheels.

3. Research on Grinding Surface Performance

A typical representative GH4169 nickel-based alloy is used for subsequent grinding experiments to analyze and discuss the performance of nano-ceramic bond grinding wheels in grinding nickel-based alloys.

In the experiment, a multi-purpose grinder model 2M9120 is used, which combines the functions of a universal cylindrical grinder and a universal tool grinder, and can grind all kinds of external cylinders, internal holes, internal and external cones, flat surfaces, and beveled surfaces with high quality. The worktable utilizes hydraulic automatic reciprocation and infinitely variable speed regulation. Its performance parameters are shown in Table 3 below. As the influence of different speeds on grinding quality and temperature should be considered in this experiment, in order to enable the grinder to produce different speeds, we adopt the method of installing a frequency converter to realize the change in the grinding speed of the grinder by controlling the frequency of the power supply. The grinding machine parameters listed in Table 3, such as motor speed, maximum workpiece size, table travel, and total motor power, correspond to the nameplate data and recommended operating conditions provided by the manufacturer of the 2M9120 multifunction grinder. These parameters ensure sufficient machine rigidity and stable operation under continuous grinding of GH4169. In the present experiments, these values are kept constant throughout all tests in order to avoid machine-related variations and to isolate the effects of the grinding process parameters (wheel speed, feed speed, and depth of cut) on the grinding performance. The different wheel speeds required in this work are obtained by using a frequency converter, while all other parameters in Table 3 remained at their standard recommended settings.

Table 3.

Grinding machine parameters.

According to the table loading size of the test grinder, we select an 80 × 30 × 15 mm size GH4169 nickel-based alloy specimen, due to the grinding process belongs to the finishing process. Before the experiment, to ensure that the specimen has a certain degree of flatness, the poor surface quality of the specimen can be used for a first milling for roughing. The schematic diagram of the workpiece is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The size of the 80 × 30 × 15 mm GH4169 nickel-based alloy workpiece.

In order to be able to optimize the grinding parameters while making a comprehensive comparison of the grinding performance of the two grinding wheels, we adopted the three-factor, three-level orthogonal test method in the experimental design. This method can systematically examine the influence of multiple variables in the grinding process on the grinding effect and ensure the scientificity and reliability of the experimental results through reasonable experimental arrangements. In the experiment, we selected three main factors affecting the grinding performance and set three different levels for each factor. Through the design of an orthogonal test, we were not only able to comprehensively analyze the influence of each factor in a short period of time, but also effectively find out the optimal combination of grinding parameters to ensure the comparability and representativeness of the experimental results. Finally, through the statistical analysis of the experimental data, we arrived at a set of optimal parameters that can significantly improve the grinding efficiency and quality, thus providing a scientific basis for the comparison of the performance of the two grinding wheels and guidance for the optimization of the grinding process in practical applications. The grinding experimental conditions in Table 4 were selected by considering three main factors: (i) the capability and safe operating limits of the grinding machine and the CBN grinding wheels, (ii) typical process parameter ranges reported in the literature for grinding GH4169 and similar nickel-based superalloys, and (iii) preliminary trial tests conducted in this work. The lower bounds of wheel speed, feed speed, and depth of cut were chosen to ensure stable material removal without grinding burn, whereas the upper bounds were limited by the onset of thermal damage and excessive wheel wear observed in the preliminary tests. The selected levels cover a range that is representative of practical industrial applications while still allowing the influence of each parameter on grinding force and surface quality to be clearly identified.

Table 4.

Grinding experimental conditions.

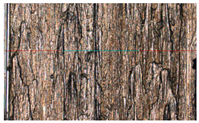

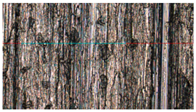

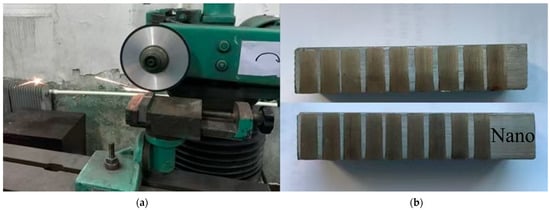

The experimental diagram of the grinding equipment and the macroscopic appearance of the finished workpiece are shown in Figure 4. The diagram shows the grinding equipment used in the experiment and the appearance of the workpiece after processing. By comparing the grinding effect of different grinding wheels, the different surface morphology produced by the two types of grinding wheels in the processing can be observed intuitively. At the macroscopic level, Figure 4 clearly shows the overall appearance of the workpiece after grinding, which can reflect key features such as the roughness and surface uniformity during the grinding process.

Figure 4.

(a) Grinding equipment machining process; (b) the result of the workpiece after machining.

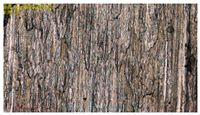

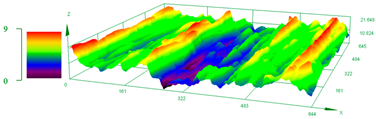

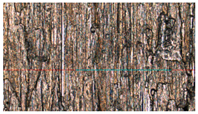

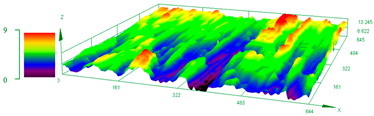

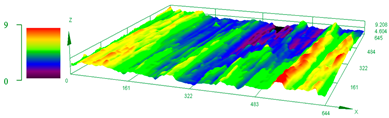

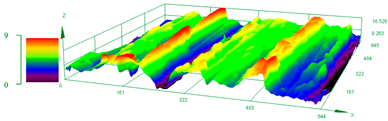

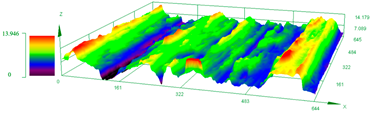

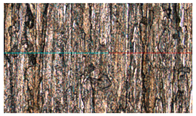

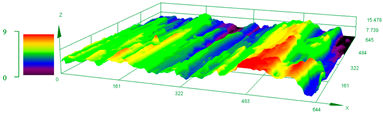

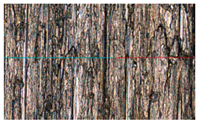

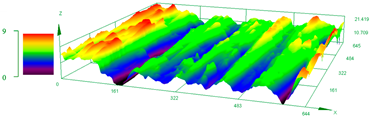

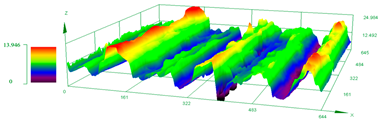

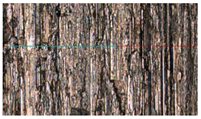

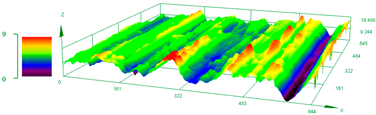

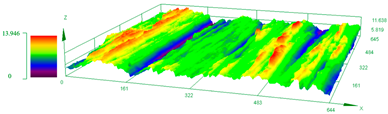

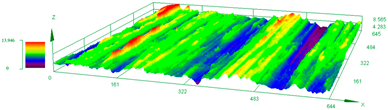

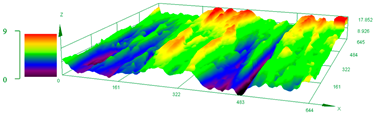

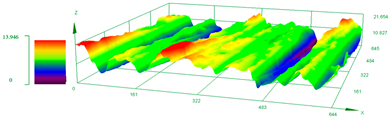

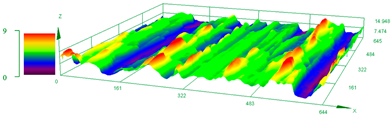

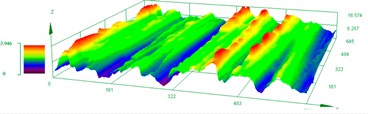

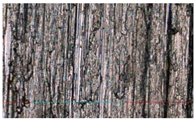

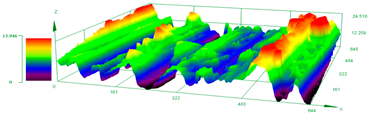

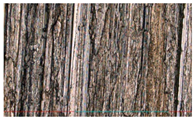

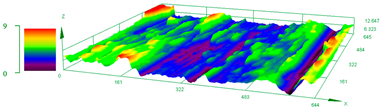

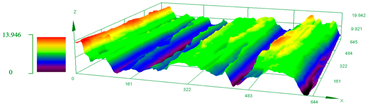

In order to further study the grinding effect, we also analyzed the grinding area in more detail. By using a three-dimensional laser microscope to observe the surface of the ground area, microscopic morphology maps were obtained. These high-resolution microscopic images can accurately reflect the changes in surface morphology during the grinding process of the grinding wheel, including microscopic scratches, surface roughness, wear marks, and the surface microstructure of the grinding wheel after contact with the workpiece. By comparing the microscopic morphology maps of different grinding wheels after processing, we can visualize the influence of the two grinding wheels on the surface quality of the workpiece at the microscopic level.

In addition, the Ra value, a parameter of the machined surface that quantifies the surface quality, was measured during the experiment. The differences in the machined surface quality of different grinding wheels were further verified by measuring and comparing the Ra values of two different grinding wheels after machining. The results show that different grinding wheels produce different surface roughness in the grinding process, and the change in Ra value can effectively reflect the influence of the grinding wheel on the surface machining accuracy of the workpiece, thus providing an important basis for selecting the appropriate grinding wheel and optimizing the grinding parameters.

The microscopic observations of the ground surfaces are consistent with the measured surface roughness values in Table 5 and Table 6. For the nano-ceramic bond CBN wheel, specimens with lower Ra (approximately 1.1–1.3 μm) exhibit relatively uniform and shallow parallel grinding marks, with only a small amount of adhered chips and limited plastic flow on the surface. As the roughness increases (Ra > 2 μm), the surface shows deeper grooves, local micro-fracture pits, and more obvious material smearing, indicating stronger plowing and more severe plastic deformation. Compared with the conventional vitrified CBN wheel under similar process conditions, the nano-ceramic bond wheel generally produces finer and more regular scratches and fewer surface defects. This confirms that the nano-ceramic bond is beneficial for maintaining sharp cutting edges and improving the surface integrity of GH4169 during grinding.

Table 5.

Experimental analysis of nano-bonded grinding wheel grinding.

Table 6.

Experimental analysis of conventional ceramic bond grinding.

For each grinding condition listed in Table 5 and Table 6, three repeated tests were carried out under identical process parameters. The mean values and standard deviations of the surface roughness were calculated, and the results presented with error rate can be found in Table 5 and Table 6. The relatively small standard deviations indicate good repeatability of the grinding process and confirm the reliability of the observed trends for both the nano-ceramic bond CBN wheel and the conventional vitrified CBN wheel.

In the orthogonal experimental design, we input the measurement results of different grinding dosages into the orthogonal experimental table, and through scientific and reasonable experimental design, we can efficiently analyze the influence of each factor on the grinding effect and find out the optimal combination of grinding parameters. The orthogonal experimental method can not only help us screen out the key factors affecting surface roughness, but also clarify the interaction relationship between different factors, thus revealing the specific influence of each grinding dosage on the surface quality trend.

Table 7 and Table 8 present the trend of the influence of each grinding dosage on the change in the arithmetic mean deviation (Sa value) of the surface profile. By analyzing the data in Table 5 and Table 6, we are able to clearly see the extent and direction of the influence of different grinding dosages on the surface roughness of workpieces under different conditions. For example, certain grinding dosages may be able to effectively reduce the surface roughness within a certain range, while the roughness may instead increase when the range is exceeded. In this way, we can not only identify the most suitable grinding parameters but also provide a strong theoretical basis for the optimization of the grinding process in actual production.

Table 7.

Experimental analysis of orthogonal grinding with nano-ceramic bond grinding wheels.

Table 8.

Experimental analysis of orthogonal grinding of conventional ceramic bond grinding wheels.

Range is an important parameter in the results of orthogonal analysis, and the range can indicate the degree of influence of changing the level of each factor on the experimental results. Comparing the two experiments, it can be seen that the grinding wheel speed has a much greater effect on the surface roughness of the workpiece than the other two factors among the three factors in the two experiments. In addition, among the three mean values corresponding to a certain factor, the one with the smallest mean value represents the smallest surface roughness under this kind of processing parameter, which is the processing parameter that should be used in the grinding process.

In Table 7, under the factor of wheel speed: mean 3 > mean 2 > mean 1; under the factor of feed speed: mean 2 > mean 1 > mean 3; under the factor of depth of cut: mean 3 > mean 1 > mean 2. Therefore, for the ceramic bond grinding wheel, the optimum can be achieved by adopting a cutting speed of 20 m/s, a feed speed of 1.2 m/min, and a depth of cut of 40 μm; however, this kind of parameter does not does not belong to the experiment under the nine parameters, which is one of the characteristics of orthogonal experiments. By the same token, for the conventional ceramic bond grinding wheel, the optimal parameters are 20 m/s cutting speed, 1 m/min feed speed, 40 μm depth of cut to reach the optimal state.

According to the experimental data, with the increase in grinding wheel speed, the surface roughness value of the workpiece processed by the two kinds of grinding wheels shows a decreasing trend, which indicates that the use of high speed for GH4169 alloy can improve the processing surface quality. Analysis from the perspective of the grinding removal mechanism, the increase in grinding speed can make the single chip formation time become shorter, and the time will be shorter under high-speed grinding conditions. High-speed grinding makes the workpiece surface plastic deformation weakened, a single abrasive grain scratching the formation of the plastic bulge height of the material is reduced, while the grinding process of the plowing and the sliding and rubbing stage of the distance becomes shorter, the workpiece plastic deformation of the material is reduced, and thus the surface hardening and residual stresses are also reduced. At the same time, the plastic deformation of the workpiece material is reduced, so the surface hardening and residual stress tend to weaken, and higher surface quality can be obtained. With the increase in grinding wheel speed, the surface roughness of GH4169 decreases for both the nano-ceramic bond CBN wheel and the conventional vitrified CBN wheel. This trend can be explained by the change in the material removal mechanism at higher wheel speeds. When the wheel speed increases, the interaction time between each abrasive grain and the workpiece is shortened, and the undeformed chip thickness as well as the effective cutting depth per grain are reduced. As a result, the cutting force acting on a single grain decreases, the plowing and sliding stages are weakened, and the extent of plastic deformation and surface hardening is reduced. Consequently, the grinding grooves on the workpiece surface become shallower and the plastic bulges are less pronounced, leading to a lower surface roughness value (Ra). This mechanism applies similarly to both grinding wheels, which explains the consistent decreasing trend of surface roughness with increasing wheel speed observed in this study.

Under the condition of the same grinding depth, the grinding performance of the nano-ceramic bond grinding wheel is superior, and the roughness of the grinding surface is also lower. When changing the grinding feed speed, an ordinary ceramic bond grinding wheel showed a different trend, which may be due to the selection of the feed speed. It seems that the feed impact on the surface roughness has the smallest impact. There may be some experimental error caused as the two show a different trend.

According to the grinding depth, under the same working conditions, both grinding wheels show the trend of decreasing and then increasing, and the surface roughness value is the smallest when the cutting depth is equal to 40 μm. After the depth of cut increases, the grinding thickness of a single grit increases, the degree of grit scribing on the surface of the workpiece increases, the size of the grit cutting trajectory increases, and thus the roughness value increases; in addition, by the theory of indentation fracture, the depth of grind increases, i.e., the depth of a single grit is pressed into the material, the material undergoes an increased load, and microcracks are more likely to be generated and expanded, which results in a larger Ra. In addition, if the grinding depth is too small, it will lead to a great reduction in the effective contact between the grinding wheel grits and the workpiece, which will also make the surface roughness of the workpiece larger, so the trend of the data in the experiments is in line with the analysis of the microscopic theory.

4. Research on Grinding Force

Due to the friction, cutting, and adhesion phenomena that exist in the grinding process, the generation of these phenomena will lead to the emergence of the grinding force. In the grinding process, the abrasive grain and material cutting surface will cause sliding friction plow, and the material deformation force and friction of the two aspects of the role will lead to a single abrasive grain; when the abrasive grains produce cutting action, they will be cut away from the abrasive chip due to strong deformation and will produce deformation resistance to the abrasive grain. The friction between the surface of the abrasive grain, the machined surface of the workpiece, and the abrasive chips also generates friction resistance. In addition to the abrasive grains, the bond in the contact zone also generates friction with the workpiece due to extrusion and high-speed movement. Therefore, the grinding force is mainly composed of two parts, the cutting force and the friction force, which originates from the elastic deformation, plastic deformation, chip formation, and the friction between the abrasive grains, the bond, the surface of the workpiece caused by the contact between the workpiece and the grinding wheel.

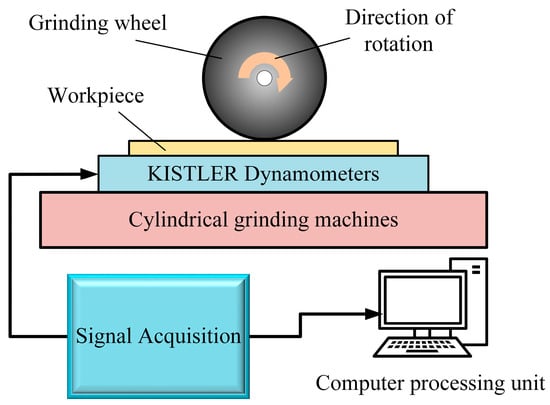

The grinding force is closely related to the material removal mechanism and is also a basic feature of the grinding process. The durability of the grinding wheel and the quality of the grinding surface are directly related to the size of the grinding force, which is easy to measure and controllable, and can be used not only to diagnose the state of the grinding, but also to assess the grindability of the material. In this experiment, a KISTLER three-phase piezoelectric crystal force gauge was used to measure the grinding force during the grinding process. The principle is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of grinding force measurement.

In the experiment, the dynamic grinding force signal components in the three directions of Fx, Fy, and Fz can be obtained from the force measuring instrument. The piezoelectric crystal sensor can output a weak charge signal of about 10–12 coulomb level, the signal is amplified and converted into a voltage signal through the charge amplifier, and then the three-channel signals are mixed by the hub to be converted into a digital signal by the A/D data acquisition card, and, finally, countless grinding force data points can be stored on the computer in the form of *.ASC or *.TST data files, and then analyzed and processed accordingly. *.ASC or *.TST data files are stored on the computer and then analyzed and processed accordingly. Before conducting the experiment, the force gauge should first be calibrated, the weights increased one by one and then reduced one by one, and, finally, the image obtained can be the same as the loaded weight of the load, and the force gauge is accurate. Figure 6 shows the process of using the experimental dynamometer.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic installation of force measurement instrument; (b) dynamometer testing process.

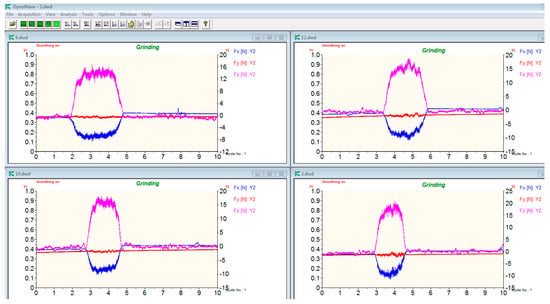

Open the image signal processing software, in the editing options only choose to retain the Fx, Fy, Fz three channels, which means that it will only show the force measuring instrument measured Fx, Fy, Fz three directions of the data, respectively, corresponding to the grinding process of tangential force, axial force, and normal force. Then, the filtering process is carried out, and the value of 500 is set in the window size option, and some data graphs are obtained as follows.

During grinding, the dynamometer continuously records the grinding forces, and the resulting data are stored on the computer in the form of *.ASC or *.TST files. These files are then imported into MATLAB (R2025a) for subsequent analysis and processing, including filtering and calculation of the normal and tangential grinding force components. Figure 7 illustrates a representative grinding force signal in the x-, y-, and z-directions before and after filtering. The raw force signals contain high-frequency noise originating from the machine vibration and electrical interference. To obtain a smoother signal that reflects the actual evolution of grinding forces, a moving-window filter (window size of 500 sampling points) was applied using the data processing software. In Figure 7, the horizontal axis denotes the sampling index (time), and the vertical axis denotes the grinding force. The filtered curves clearly remove the high-frequency fluctuations while preserving the low-frequency trend of the grinding forces, and these filtered signals were used for subsequent quantitative analysis.

Figure 7.

Grinding force signal filtering processing.

In order to study the influence of different polishing parameters on grinding force, this paper designed a one-factor experiment to examine the specific role of different process parameters on grinding force. Through this experimental method, we can have a clearer understanding of the contribution of each polishing parameter to the grinding force and provide a theoretical basis for optimizing the polishing process. In the experiment, several common polishing process parameters were selected, such as polishing speed, abrasive granularity, and applied pressure. Each parameter was adjusted within a certain range, so as to observe the change in its influence on the grinding force. In the single-factor grinding force experiments, each process parameter was varied within a defined range while the other parameters were kept constant. Specifically, the grinding wheel speed was set to 10 m/s, 15 m/s, and 20 m/s; the feed speed was chosen as 1 m/min, and the grinding depth was adjusted to 20 μm, 40 μm, and 60 μm. These ranges were determined based on machine capability, preliminary trials, and typical values used in practice for GH4169. For each parameter level, the resulting normal and tangential grinding forces were recorded and compared to reveal the influence of that particular parameter on the grinding force.

The specific experimental process parameter settings are shown in Table 9, including the value range of each parameter and a detailed description of the experimental conditions. Through this series of experiments, the aim is to reveal the change in the rule of the grinding force under different parameter combinations and explore the mechanism behind it. The experimental results will provide important data support and a theoretical basis for subsequent polishing process optimization and efficiency improvement.

Table 9.

Parameter setting of grinding force experiment.

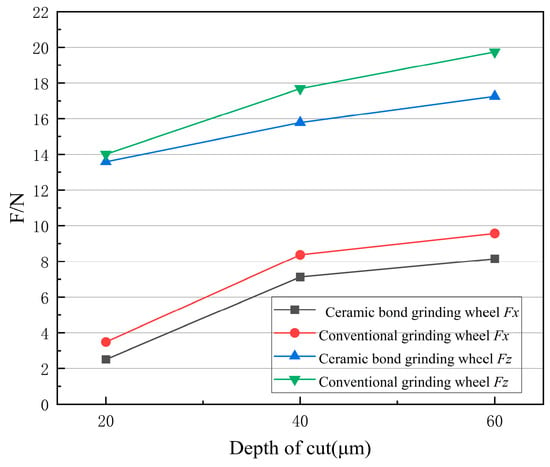

The results of the first three groups of experiments are shown in Table 9. The data summary statistics and obtained line graphs are shown in Figure 8, and can be more intuitively analyzed in the rotational speed and feed rate under the same conditions, and the different depths of cut on the grinding force.

Figure 8.

Effect of depth of cut on grinding forces.

According to the experimental results, it can be found that the normal grinding force and tangential grinding force will show an increasing trend with the increase in the grinding depth, and the influence of the grinding depth on the grinding force can be analyzed from the following four aspects. First, when other conditions are set to quantitatively not change, the increase in grinding depth leads to an increase in the undeformed grinding thickness of individual grains, which inevitably results in an increase in grinding force. Secondly, the increase in grinding depth also makes the contact arc between the grinding wheel and the workpiece longer, and at the same time, the number of abrasive grains involved in grinding increases, so that the total grinding force becomes larger. Third, the contact arc becomes larger and the discharge path of the abrasive chips becomes longer. Due to the strong friction and extrusion deformation, it is very easy for the abrasive chips in the high temperature environment of the contact area of the grinding wheel workpiece to bond with the grinding wheel, which seriously reduces the cutting performance of the grinding wheel, resulting in an increase in the grinding force. Finally, the increase in grinding depth will lead to an increase in the grinding temperature of the contact area, and the yield strength of the workpiece material on the contact surface decreases, thus reducing the grinding force. However, the grinding speed used in this experiment is relatively low, the grinding temperature does not have much influence on the yield strength of the workpiece, and the increase in grinding force is much larger than its reduction, resulting in a significant increase in grinding force with the increase in grinding depth. This increasing trend of normal and tangential grinding forces with depth of cut is consistent with classical grinding theory and has been widely reported in the literature for various workpiece materials, including nickel-based superalloys, when using CBN wheels [17,31,32,33].

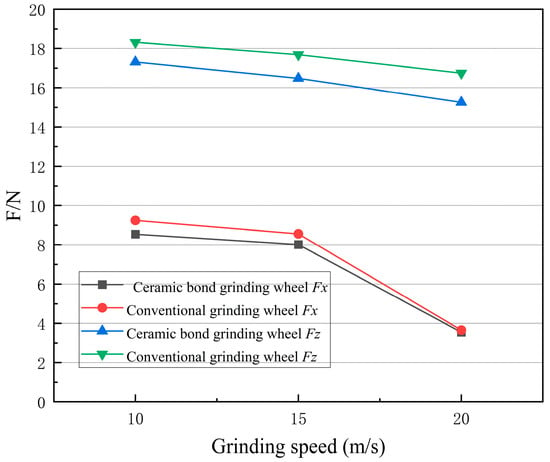

Data summary statistics of the results of the last three groups of experiments, in Table 9, show the same trend. According to the experimental data, the effect of different cutting speeds is the same on the grinding force under the same conditions of depth of cut and feed rate.

Analysis from a microscopic point of view of the grinding process, with the abrasive cutting edge gradually contacting the surface of the workpiece, reveals the workpiece first undergoes elastic deformation. With the abrasive grains further pressed into the workpiece, the workpiece continues to deform, and the tangential force and the normal force gradually become larger. If the normal stress exceeds the yield stress of the material, the abrasive grain will cause workpiece material extrusion to the abrasive grain on both sides, causing the formation of a concave and convex scratch surface, that is, the plow effect. If the bump created by the plow hits the next grit, the material is removed, and abrasive chips are formed. If the grinding wheel is worn and the abrasive grains are dulled, the increase in the contact area between the grinding wheel and the surface of the workpiece, where continuous friction occurs, increases the extent to which friction influences the overall grinding force.

According to the results shown in Figure 9, with the increase in grinding speed, the grinding force tends to decrease. This is because the removal of the same material at high speed is equivalent to an increase in the number of cuts; that is, the number of cuts per cut is reduced, so that the grinding force will be reduced accordingly. From this, we infer that in high-speed and ultra-high-speed grinding, the excellent performance of ceramic bond CBN grinding wheels will be better reflected.

Figure 9.

Effect of grinding speed on grinding force.

Combining the data from the two experiments shows that under the same experimental conditions, in both sets of experiments, the nano-ceramic bond grinding wheels are shown to have a smaller grinding force, which also verifies the conjecture in the previous section in the grinding temperature measurement experiments. This phenomenon is due to the nano-ceramic bond grinding wheel with nanomaterials to enhance the toughness, and effectively reduce the combination of the refractoriness, so that the performance of the CBN abrasive grain is not affected by the high temperature of sintering. In the continuous grinding process, the cutting edge is not easy to blunt, and remains sharp for a long time, effectively reducing the contact area of individual abrasive grains with the workpiece, which improves the mechanical and thermal performance of the abrasive tool. The mechanical and thermal properties of the grinding tool are improved, which makes the nano-ceramic bond grinding wheel surpass the common ceramic bond grinding wheel in terms of the comprehensive performance of the bond.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Within the tested range of process parameters, the nano-ceramic bond CBN grinding wheel produces lower grinding forces and better surface roughness than the conventional vitrified CBN grinding wheel when grinding GH4169. This advantage is particularly evident at higher wheel speeds, where the nano-ceramic bond wheel maintains sharper cutting edges and generates more uniform and shallower grinding marks with fewer surface defects.

- (2)

- For both grinding wheels, the surface roughness of GH4169 decreases with increasing grinding wheel speed, while the normal and tangential grinding forces increase with grinding depth. These trends are attributed to the reduction in undeformed chip thickness and shortening of the chip-formation time per abrasive grain at higher wheel speeds, and to the enlargement of the contact area and higher material removal per grain at larger depths of cut. The experimental results are in good agreement with classical grinding theory and previously reported data for CBN grinding of nickel-based superalloys.

- (3)

- The orthogonal experimental design and single-factor grinding force tests carried out in this work provide reasonable parameter windows for high-speed and high-efficiency grinding of GH4169 with nano-ceramic bond CBN wheels. The recommended process conditions and the observed relationships between grinding parameters, grinding forces, and surface roughness can serve as a reference for the optimization of grinding processes in industrial production.

Future work could focus on several aspects. First, the long-term wear behavior and dressing characteristics of the nano-ceramic bond CBN wheel during extended grinding of GH4169 should be investigated to evaluate its service life and economic performance. Second, the influence of different cooling and lubrication strategies, such as minimum quantity lubrication or high-pressure cooling, on grinding forces, temperature, and surface integrity could be systematically studied in combination with the nano-ceramic bond wheel. Third, numerical or analytical models that couple grinding forces, temperature, and wheel wear could be developed and calibrated using the present experimental data in order to optimize process parameters and further extend the application of nano-ceramic bond CBN wheels to other difficult-to-cut materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.X., Y.Z. and W.Y.; methodology, S.X. and K.H.; software, S.X. and Y.Y.; validation, S.X., Y.Z. and W.Y.; formal analysis, S.X. and L.W.; investigation, S.X., Z.H. and C.C.; resources, S.X., J.K. and J.L.; data curation, S.X. and K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and W.Y.; visualization, Y.Y. and L.W.; supervision, Y.Z. and W.Y.; project administration, S.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number (52305453), Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (E2025501027), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N2423023).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Pan, X.; Chen, C. Effect of Cu-Sn-Ti solder alloy on morphology, bonding interface, and mechanical properties of cBN grits. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 147, 111290. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Fang, L.; Yang, W. Enhanced compressive strength by Ti-Cr coating on cBN particle surface using vacuum vapor deposition. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 151, 111762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Liang, G.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, M.; Yang, S.; Lv, M. Effect of addition on microstructures and mechanical properties of cBN/Cu-Zn-Ti composites via the pulse electric current sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L.; Lv, J.; Yu, T.; Zhao, J. No-impact trajectory design and fabrication of surface structured CBN grinding wheel by laser cladding remelting method. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, R. Influence of Electroplated CBN Wheel Wear on Grinding Surface Morphology of Powder Metallurgy Superalloy FGH96. Materials 2020, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Su, J.; Liu, L. Peridynamic Simulation to Fracture Mechanism of CBN Grain in the Honing Wheel Dressing Process. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G.; Ortega, N.; Bravo, H.; Dubar, M.; González, H. An Analysis of Electroplated cBN Grinding Wheel Wear and Conditioning during Creep Feed Grinding of Aeronautical Alloys. Metals 2018, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ding, W.; Xiao, G.; Cai, K.; Li, Z.; Pu, C. Micro-fracture behavior of a single-aggregated cBN grain and its relation to material removal in high-speed grinding of Ti–6Al–4V alloys. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 79, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M.; Kim, H.-N.; Ko, J.-W.; Kwak, T.-S. Experimental Study on ELID Grinding of Silicon Nitride Ceramics for G5 Class Bearing Balls. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wu, H.; Sun, L.; Shi, X.; Li, G. Study on Preparation and Grinding Performance of Vitrified Bond CBN Grinding Wheel with Controllable Porosity. Micromachines 2022, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Xiang, D. The mechanism investigation of ultrasonic roller dressing vitrified bonded CBN grinding wheel. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 24421–24430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Y. Fabrication and wear characteristics of open-porous cBN abrasive wheels in grinding of Ti–6Al–4V alloys. Wear 2021, 477, 203786. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Sun, K.; Ren, W.; Zhang, J.; Han, Z. Synergistic improvement of grinding fluid utilization and workpiece surface quality using combinatorial bionic structured grinding wheels. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 130, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. Identification of grinding wheel wear states using AE monitoring and HHT-RF method. Wear 2025, 562–563, 205668. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, G. Thermal defects generation mechanism in laser precision dressing of metal-bonded micro-groove diamond wheel and their influence on grinding silicon wafer. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 182, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, T.; Mano, H.; Iwai, H.; Ando, Y.; Korenaga, A.; Ohana, T.; Ashida, K.; Wakazono, Y. Effect of Acoustic Emission Sensor Location on the Detection of Grinding Wheel Deterioration in Cylindrical Grinding. Lubricants 2024, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, K.; Si, M.; Li, M.; Gong, P. Grinding Force and Surface Formation Mechanisms of 17CrNi2MoVNb Alloy When Grinding with CBN and Alumina Wheels. Materials 2023, 16, 1720. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.S.; Caggiano, A.; Kubo, A.; Chowdhury, M.A.K. Elucidating Grinding Mechanism by Theoretical and Experimental Investigations. Materials 2018, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X. Study on the CBN Wheel Wear Mechanism of Longitudinal-Torsional Ultrasonic-Assisted Grinding Applied to TC4 Titanium Alloy. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, N.-P.; Nguyen, Q.-T.; Tran, T.-H.; Le, H.-K.; Nguyen, A.-T.; Luu, A.-T.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Le, X.-H. Optimization of Grinding Parameters for Minimum Grinding Time When Grinding Tablet Punches by CBN Wheel on CNC Milling Machine. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, M. Analysis of Grindability and Surface Integrity in Creep-Feed Grinding of High-Strength Steels. Materials 2024, 17, 1784. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, S.; Wen, D. Laser textured Ti-6Al-4V surfaces and grinding performance evaluation using CBN grinding wheels. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 109, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, D.N.; Mathew, N.T.; Vijayaraghavan, L. Wear of Electroplated Super Abrasive CBN Wheel during Grinding of Inconel 718 Super Alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macerol, N.; Franca, L.F.P.; Krajnik, P. Effect of the grit shape on the performance of vitrified-bonded CBN grinding wheel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 277, 116453. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T.; Liu, C. The mechanism and machinability of laser-assisted machining zirconia ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 16971–16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Qu, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. A grinding force predictive model and experimental validation for the laser-assisted grinding (LAG) process of zirconia ceramic. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 302, 117492. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Meng, F.; Chen, X.; Qu, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Surface prediction in laser-assisted grinding process considering temperature-dependent mechanical properties of zirconia ceramic. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C.; Yin, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhu, Y. Grinding force and energy modeling of textured monolayer CBN wheels considering undeformed chip thickness nonuniformity. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 157–158, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S. Experimental Study of Nano-ceramic Bond Based on Super High-speed CBN Grinding Wheel. China Mech. Eng. 2014, 25, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Pang, Z.R.; Yu, T.B.; Wang, W.S. Experiment Study Based on Nano-Ceramic Grinding Wheel Bond. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 299–300, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, S.; Guo, C. Grinding Technology: Theory and Application of Machining with Abrasives, 2nd ed.; Industrial Press: South Norwalk, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y.; Xu, J.-H.; Fu, Y.C.; Tian, L. Grinding force and specific grinding energy of nickel based superalloy during high speed grinding with CBN wheel. Diam. Abras. Eng. 2011, 31, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Elfizy, A.; St-Pierre, B.; Attia, H. Grinding characteristics of a nickel-based alloy using vitrified CBN wheels. Int. J. Abras. Technol. 2012, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).