Abstract

This study introduces a novel approach to improving the functional performance of document coatings through the development of a chitosan-modified epoxy-acrylate varnish intended for application on the specialized substrate used in banknotes. In this first phase, the work focuses exclusively on assessing the thermal, mechanical, and optical behavior of the varnish films to establish the technical feasibility of incorporating chitosan into this type of high-security coating. Chemical characterization was conducted via FTIR, while DSC and DMA were used to evaluate the thermal transitions and viscoelastic properties of the cured films at different chitosan concentrations. Gloss measurements were used to quantify the visual impact on the coating. The results reveal a systematic increase in crosslinking and stiffness with higher chitosan content, accompanied by a reduction in gloss. Formulations containing 1% and 5% chitosan emerge as the most technically viable, maintaining adequate mechanical integrity and appearance while enabling future antimicrobial enhancement. The antimicrobial properties of chitosan-based films, central to the next stage of this research, will be reported in subsequent work. This first-stage evaluation provides a solid foundation for integrating biopolymer additives into security and commercial printing technologies, advancing the development of sustainable functional coatings.

1. Introduction

Banknotes issued by central banks are undoubtedly the preferred means of payment for the exchange of goods and services between people around the world, especially in developing countries. During circulation, banknotes are handled and distributed by different people with very different personal hygiene habits and are often stored in adverse hygienic conditions [1,2,3,4]. Although electronic payments and the use of cards have gradually replaced traditional money handling, cash exchanges are still commonly used throughout the country, with banknotes being a means of carrying and proliferating infectious agents (fomites) [5,6,7,8,9].

In addition, it is important to consider that, due to the growing demand for banknotes and coins in 2020 in Mexico, the need to mitigate health risks such as SARS-CoV-2, also called COVID-19, has grown that year [10,11,12]. Therefore, the scientific community and the public expressed their concern about viruses, bacteria, and fungi presents on surfaces, during public transportation, stays in hospitals, offices, schools, or businesses, to name a few [8,10,11,12,13]. Scientists have recently found 3000 different types of bacteria on a single US dollar bill, such as Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, which can cause various diseases [5,9,14]. Therefore, if we consider that, in Mexico, in each of the locations, the use of cash is in many cases a necessity, it is feasible to consider that the microorganisms present on banknotes are a source of contagion between people, when sharing them from hand to hand [12].

1.1. Varnishes

Varnishes are often used to enhance the shine or increase the durability of graphic arts work. They are designed to achieve two objectives: to enhance the result and to protect it from external agents such as water, chemicals, friction, or dirt [13].

Within the current market, there are different options: oxidation-drying varnishes, known for using oils that impart a yellow hue, offer a good shine, and the drying process is slow; then there are evaporation-drying varnishes, which dry faster than the previous ones; finally, UV (Ultra Violet) varnishes, characterized by offering very good shine, great resistance, and almost instant drying. UV varnishes form a film on the surface that is comparable to the lamination process. Most varnishes dry by evaporation or oxidation, as mentioned above, but UV varnish dries through a chemical bonding mechanism. This is achieved by subjecting the varnish to ultraviolet light irradiation [15,16].

The properties of UV varnishes are related to their chemical composition and film formation mechanism. When varnish substances do not receive enough UV light, they remain soft and sticky, giving off a strong odor. Although UV varnishes do not contain toxic substances, heavy metals, pentachlorophenol (PCP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), or N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone (NVP), in some countries they are not accepted in food packaging. UV varnishes have diverse applications and are widely used in the world of wood furniture, protective coatings for plastics, metal, parquet or other flooring of various types, and graphic arts. UV varnish is often used in graphic arts when glossy and elegant surface finishes are desired, as well as being resistant to water, grease, and dirt. It dries quickly after application of UV light, and other processes can then be carried out.

The morphology of the substrate to be coated is important, as UV radiation must reach all points where the varnish has been applied with sufficient intensity. If the radiation does not reach the surface completely or partially, drying is insufficient or lacking. This lack of drying can range from the product remaining sticky to the final coating properties being unsatisfactory compared to those obtained in the area where drying was successful. Therefore, the drying system and machinery (lamps) must be appropriate for the morphology of the piece [17,18].

Thus, mercury (Hg) lamps will be used for drying transparent products. Meanwhile, for drying pigmented products (non-transparent products), gallium (Ga)-doped lamps will additionally be required. These lamps will act prior to the Hg lamps to promote deep drying of the product. This deep curing is hindered by the presence of the pigments themselves, which, being opaque, prevent the passage of UV radiation. Ga lamps operate at a different wavelength than Hg, which allows for such deep drying [19,20].

1.2. Chitosan as an Antimicrobial Agent

Polymeric film has the function of coating materials, and its ability to prevent moisture loss, as well as prevent microbial growth and oxidation, can vary depending on the type of polymer [13,21,22,23,24,25]. Chitosan is widely used in the manufacture of films, since its linear structure allows flexibility and transparency with excellent resistance to fats and oils. However, because the films are made in solutions with acetic acid, they have the characteristics of being permeable to gases such as CO2 and O2 and have lower tensile strength and elongation [26,27,28]. For this reason, attempts have been made to modify or reinforce this polymer with other materials to provide it with greater support and durability, making it a widely used and highly efficient material.

Several studies have used chitosan as a coating for paper and packaging, generally employing aqueous formulations that form a chitosan layer on the substrate and provide antimicrobial and barrier properties [29,30,31]. Furthermore, studies have been published on UV-curable resins incorporating chitosan, primarily in the form of chemically modified photocurable derivatives or hydrogels, for biomedical, water treatment, or textile applications, but not as additives in industrial overprint varnishes [32,33,34].

In addition, current UV-curable antimicrobial coatings for wood, polymers, or even banknote substrates are usually based on small-molecule organic acids, natural extracts, quaternary ammonium systems, or metallic nanoparticles as active agents [35,36,37]. To our knowledge, the direct physical incorporation of chitosan into a UV-curable epoxy-acrylate varnish designed for flexographic application to banknote paper, and the systematic evaluation of its thermal (DSC), mechanical (DMA), and gloss properties as a first step towards antimicrobial security coatings, has not yet been addressed in the literature.

The aim of this work is to incorporate chitosan into an epoxy-acrylate resin to form a UV-curable varnish for coating banknote paper. In this first stage, the study focuses on evaluating the thermal, mechanical, and gloss properties of chitosan-modified films. This evaluation aims to verify that the incorporation of chitosan does not compromise the fundamental functional requirements of these coatings when applied to banknote substrates.

2. Materials and Methods

Reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Gloss 18 UVtec V1-124 varnish (Sánchez, S. A. de C. V., Mexico City, Mexico), was chosen because, in addition to being manufactured mainly from an acrylate epoxy resin, tripropylene glycol diacrylate as a solvent and amines as a photo initiator, it is applied in flexographic printing systems, which facilitates scalable and profitable production [38]. In the case of chitosan, this is a Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) product with a deacetylation degree of 83.2%. Chitosan was solubilized in acetic acid [2,3,4,39,40,41]. To do this, 0.1014 g of chitosan was dissolved in 10 g of 1% v/v acetic acid, using the Hauschild DAC 150.1 FVZ centrifuge (Lyons, IL, USA), FlackTek-Speed Mixer brand (Louisville, CO, USA), at operating conditions of 180 s at 3000 RPM, to obtain a 1.014% w/w solution.

To ensure homogeneous dispersion of chitosan within the varnish, chitosan was first completely solubilized in acetic acid, four mixtures were prepared at different concentrations (1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% w/w) to obtain the varnish mix and then incorporated using controlled centrifugation [42] (Table 1). All the above was mixed at room temperature under operating conditions of 180 s at 3000 RPM.

Table 1.

Formulations for mixed varnish with chitosan.

For film formation, a four-sided (25, 50, 75, and 100 micron) wet-film applicator from Biuged Instruments (Tianhe District, Guangzhou, China) was used. It is designed based on the ASTM D823 standard [43] used in the “Standard Practices for Producing Films of Uniform Thickness of Paint, Coatings, and Related Products on Test Panels.” For its use, a drag bed was improvised by placing a 6 mm commercial glass plate measuring 30 × 10 cm, free of scale, on a cotton cloth (Figure S1a in Supplementary Materials). To begin, the glass surface is cleaned with ethyl alcohol; then a minimal amount of varnish or blended varnish is placed on the top edge of the glass (0.8–1.2 g), ensuring that it is evenly distributed across the width of the glass (Figure S1b in Supplementary Materials). Thereafter, it is dragged along the glass with the help of the applicator, using a firm motion at a speed of 100 to 150 mm/s.

Subsequently, the formed film is cured in the IGT Ak-tiprint UV equipment (Almere, The Netherlands), for which the glass is placed on the equipment’s conveyor belt and the speed is set to 10 units of what the potentiometer indicates (Figure S2a in Supplementary Materials). Once the film is cured, it is removed from the glass with the help of a straight, single-edged blade, positioning said blade at an angle of 30° with respect to the glass and ensuring that the blade never comes off the surface until the film is completely detached from the glass (Figure S2b in Supplementary Materials). Finally, the film is passed through the curing equipment again, ensuring that the side adhered to the glass faces the lamp.

Once the films were fully cured and detached from the glass substrate (Figure S2b), their chemical structure was analyzed using FTIR Spectroscopy. Spectra were obtained on a Varian FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), model 640-IR, operated in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode using a zinc selenide (ZnSe) crystal as the internal reflection element. Each spectrum was recorded in the range of 4000–500 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 accumulated scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Prior to each measurement, the ATR crystal was cleaned with isopropanol to avoid cross-contamination. The obtained spectra were used to confirm chitosan incorporation and to evaluate potential interactions between the polymeric resin and the biopolymer. In addition, a thermal analysis of the films was performed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) in a Q20 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) under the following conditions: Equilibrate at 25.00 °C, isothermal for 2.00 min, ramp 10.00 °C/min to 200.00 °C. A dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was also carried out with a Q800 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). A tension film clamp was chosen for this work, and testing was conducted under the following conditions: Equilibrate at 30.00 °C and ramp strain 0.1000 to 10.00%/min. These parameters were selected to determine the effect of chitosan addition on the mechanical properties of the composite varnish. Additionally, the gloss of the varnish and mixed varnishes were measured using a Neurtek NKG Trio glossmeter (Elbar, Spain) (20°/60°/85°). This measurement was performed on samples printed using the Harper Scientific Handproofer Phantom Flexo UV equipment (Charlotte, NC, USA), following the varnish manufacturer’s recommendations, with an Anilox roll of 200 lines per inch and a volume of 6.8 BCM (Billions of Cubic Microns per inch). The prints were applied onto Gloss Finish Coated Book Printing Ink Drawdown Sheets, Leneta code Form 3NT-31 (Mahwah, NJ, USA), in accordance with the ASTM D 523 standard [44] (Figure S3).

The dispersion of chitosan within the cured varnish films was examined using a JEOL Scanning Electron Microscope JSM-IT100 (Peabody, MA, USA). Samples were mounted on aluminum stubs using conductive carbon tape and analyzed without sputter coating to preserve the native morphology of the organic films. Imaging was performed at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV, using composition backscattered electrons (BSE) to enhance contrast between the epoxy–acrylate matrix and the chitosan-rich domains. A chamber pressure of 40 Pa was employed to minimize charging effects associated with non-conductive samples. Micrographs were acquired at various magnifications (from 500× to 1000×) to assess both large-scale distribution and potential micro-agglomeration of chitosan within the polymer matrix.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization by FTIR Spectroscopy

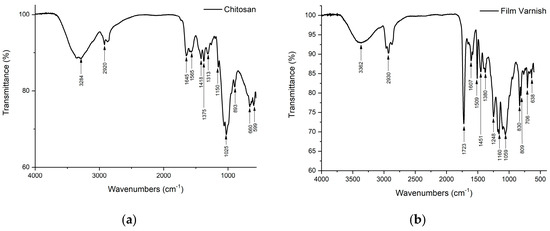

Spectroscopy was performed on chitosan (Figure 1a) and the varnish used for this study (Figure 1b). The FTIR spectrum of chitosan (Figure 1a) shows bands representing the functional groups characteristic of the chitosan molecule. Bands corresponding to the stretching of the O-H and N-H bonds (3100–3500 cm−1) are also visible, characteristic of alcohols, amines, and amides present in the deacetylated structure. This band is centered at 3284 cm−1 due to the overlap of the bands originating from the stretching and tension of the O-H and N-H groups [45,46]. The spectrum also shows bands of C-H stretching at 2920 cm−1 and others originated by C=O and N-H stretching, characteristic of amide groups, between 1645 and 1565 cm−1. The characteristic band at 1645 cm−1 is related to the C=O group present in an amide group (I) and the one assigned at 14,189 cm−1 is due to an amide group (II). The absorption band related to deformations of the amino group is observed at 1565 cm−1, while the band at 1375 cm−1 arises from stretching vibrations of the methyl group (C-H), associated with the incomplete deacetylation of chitin, or O-H groups attached to the rings [45,46]. The absorption bands in the range 1260 to 800 cm−1 are attributed to the glycosidic ring, in particular, the band at 1150 cm−1 corresponds to the glycosidic bond. Regarding the FTIR spectrum of the Brillante 18 UVtec V1-124 varnish (Figure 1b), it presents the characteristic bands of epoxy-acrylates in infrared spectroscopy, mainly in the region of the C=O, C-O and C-H bonds, especially in the unsaturated C=C bonds. Bands related to the epoxy group and to the acrylate groups can also be identified [47,48,49]. An intense band is observed in the region of 1723 cm−1 due to the stretching vibration of the carbon-oxygen (C=O) bond in the carbonyl of the acrylate group, the bands in the region of 1248 cm−1 and 1160 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of the carbon-oxygen (C-O) bond in the ether and ester groups present in the structure, the band in the region of 2800–3000 cm−1 due to the C-H bonds present in the alkyl and aryl groups of the structure. A band is detected in the region of 1600–1640 cm−1 corresponding to the stretching vibration of the carbon-carbon (C=C) double bond present in the acrylate groups. The band at 979 cm−1 can be identified and its intensity is related to the number of epoxy groups. On the other hand, tripropylene glycol diacrylate (TPGDA) is a diacrylate, which means that it has two acrylate groups (CH2=CH-COO-) attached to a tripropylene glycol chain. The characteristic FTIR band is found in the range of 1720–1730 cm−1, corresponding to the C=O stretching vibration of the acrylate group. In addition, bands can be observed in the 1630–1640 cm−1 and 810–815 cm−1 regions due to the stretching and deformation vibrations of the C=C double bond [47,48,49].

Figure 1.

FTIR spectrum of (a) chitosan, (b) Gloss 18 UVtec V1-124 varnish.

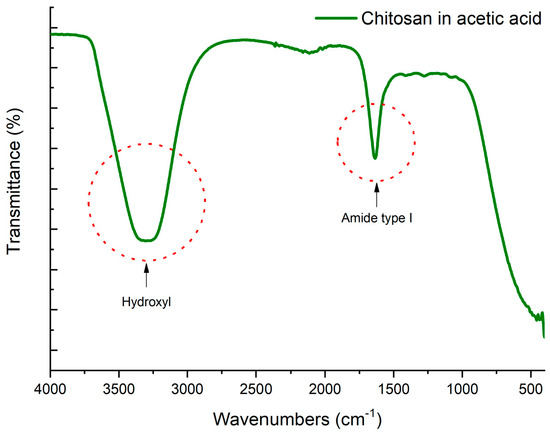

On the other hand, Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectrum of chitosan acetate product of the dissolution in acetic acid where a broad band of alcohols (O-H) is observed in the region of 3200–3600 cm−1, another in the region of 1680–1750 cm−1 indicating the presence of hydroxyl and amide type I, which contributes to the amide stretching vibrations of chitosan as indicated by research works by other authors [50,51]. It has been suggested that primary amine gets regenerated from their protonated form with the evaporation of aqueous acetic acid solution and water. It was also reported that protonated amine of chitosan exists in equilibrium with the acid content present [52]. Studies on the dissolution of chitosan in various carboxylic acids have shown that protonated amine groups are regenerated to their original amine form as the acid solution gets evaporated from the mixture and the regeneration is dependent on the nature of carboxylic acid used. In addition, they observed that this regeneration is more favorable with acetic acid when compared to using other carboxylic acids such as formic, butyric or valeric acids. Formation of stable intermediary compound is also not favored as it may hinder the regeneration of amine groups of chitosan. This is significant especially in case of formic acid where chitosan forms formamide when treated with formic acid. Thus, regenerated primary amine groups from chitosonium acetate will become readily available to crosslink with oxirane groups of resin [52].

Figure 2.

FTIR spectrum of chitosan in acetic acid solution.

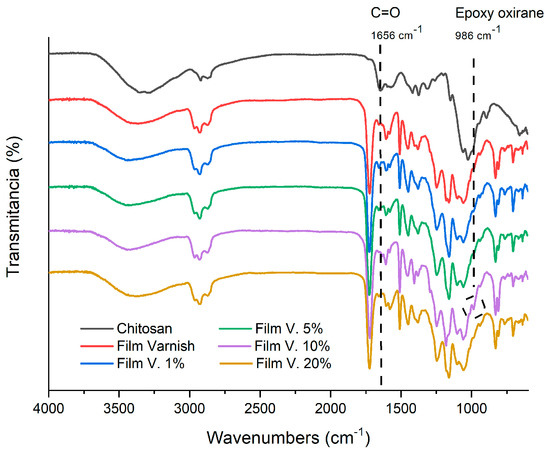

Figure 3 presents the FTIR spectra obtained from the blended varnish at different concentrations after film curing. The chitosan spectrum in Figure 3 shows a band at 1656 cm−1 attributable to the C=O bond of the amide group. It is noteworthy that this band is not seen in the spectrum of the varnish film without chitosan, but it begins to appear in films that do contain the biopolymer, which is evidence of its presence in the cured films. Furthermore, it is important to note that chitosan at low concentrations (1% and 5%) does not interfere with the curing process of epoxy-acrylate resins, since the band at 986 cm−1 attributable to the oxirane group is not observed in the FTIR spectra of these cured films, implying a ring-opening reaction. However, it reappears in the FTIR spectra of films with 10% and 20% chitosan, indicating possible agglomeration of chitosan particles at high concentrations. The presence of a characteristic broad and pronounced band at 3480 cm−1 for the hydroxyl groups, and a band at 1718 cm−1 for the carbonyl group, confirmed the chemical reaction between the epoxy and the acrylate in the resin. The shift in the hydroxyl peaks between a wave number of 3420 cm−1 and 3280 cm−1 suggests a possible increase in the strength of the hydrogen bonding groups.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of chitosan and films made from the blended varnish at different concentrations.

3.2. Morphological Analysis (SEM)

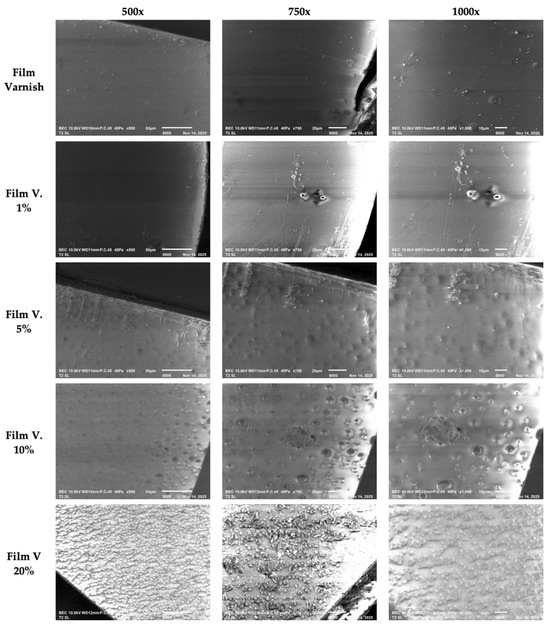

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed immediate and progressive morphological changes in varnish films modified with chitosan (Figure 4). The unmodified formulation exhibited a smooth, homogeneous, and continuous surface with no detectable structural defects, confirming a stable monophasic system. Incorporation of 1% chitosan led to the appearance of isolated microdomains and slight discontinuities, indicating the onset of local incompatibility between the biopolymer and the matrix. Although overall film integrity remained acceptable, this early response highlights the limited miscibility of chitosan even at low concentrations. At 5%, the surface displayed a systematic distribution of microbubbles and more defined domains, characteristic of initial phase-separation phenomena. Surface roughness increased, and the film showed evidence of saturation of the dispersed phase, marking the operational threshold at which the coating ceases to be fully uniform.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the varnish film and films modified with 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% chitosan at 500×, 750×, and 1000× magnification.

Formulations containing 10% and 20% chitosan exhibited severe structural deterioration: large agglomerates, extensive particle coalescence, and a highly rough, irregular texture. The surface lost continuity and adopted an unstable biphasic morphology, incompatible with functional applications requiring uniformity, mechanical integrity, or barrier performance. Taken together, the results indicate that chitosan incorporation is only morphologically viable below 5%. Higher concentrations lead to pronounced phase separation and significant structural degradation of the film.

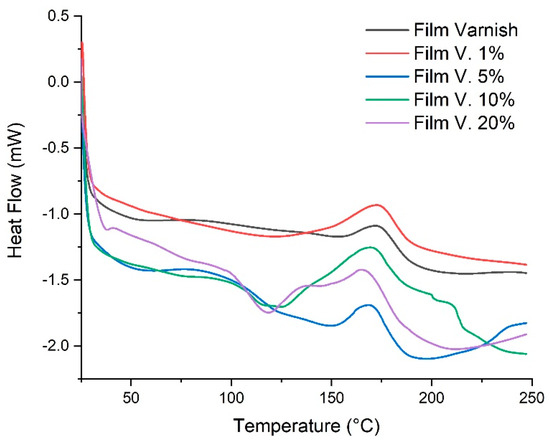

3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC thermograms (Figure 5) show that adding low concentrations of chitosan (1%–5% w/w) increases the degree of cure and enhances resin reactivity at lower temperatures. This behavior is consistent with previous studies reporting that addition of chitosan filler improves the crosslinking effect in the compositions. It is probably connected with the chemical structure of chitosan and a possible reaction between amine groups and epoxy resin [53]. In contrast, the formulation containing 20 wt% chitosan exhibits a broader and less intense exothermic peak, with reduced conversion at lower temperatures. This trend is consistent with previous studies indicating that excessive chitosan loading can lead to particle agglomeration, reduced resin mobility and, consequently, a diffusion-controlled curing regime [54]. The thermal parameters summarized in Table 2 show that Tg increases with chitosan concentration, can be attributed to restricted segmental mobility and a higher effective cross-link density, which has also been observed in polymer systems where chitosan or other polysaccharides form hydrogen-bonded networks with the matrix [55]. These interactions explain why low chitosan loadings (1–5 wt%) improve or maintain the thermomechanical performance of the varnish, whereas higher loadings lead to embrittlement and poorer optical properties.

Figure 5.

DSC thermograms of varnish films with chitosan acetate at different concentrations.

Table 2.

Thermal parameters, (Tg) and (∆Hm) in varnish films with chitosan.

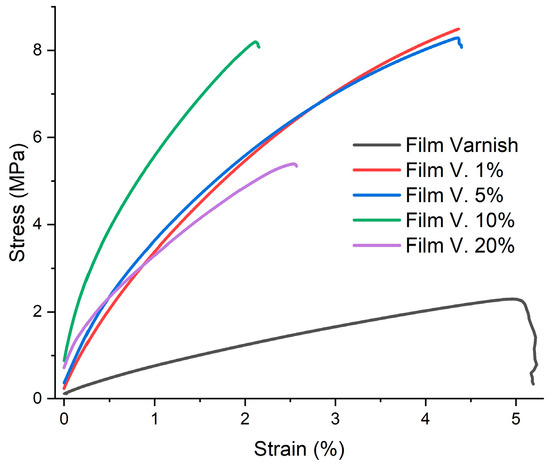

3.4. Dynamic Mechanical Análisis (DMA)

The mechanical strength of the chitosan-based varnish films was evaluated by DMA tensile measurement. The stress–strain curves of the obtained films are shown in Figure 6, while Young’s modulus and other characteristics determined from these curves are shown in Table 3. The presence of chitosan at low concentrations in the films significantly improved their mechanical properties compared to those of the film without chitosan. According to the data obtained in Table 3, the incorporation of chitosan acetate significantly increased the tensile strength and Young’s modulus, as shown by the typical stress–strain curves in Figure 6. It is observed that as the chitosan content in the film increases, Young’s modulus increases, but only up to 10% w/w chitosan, beyond that content the Young’s modulus decreases. This can be attributed to the fact that at low amounts of chitosan, it is better dispersed between the chains, forming hydrogen bonds between the epoxy-acrylate resin and the chitosan acetate due to crosslinking by the curing process.

Figure 6.

Stress–strain curves in DMA tensile tests for film varnish and all film blended varnish. Data obtained with the tension film clamp.

Table 3.

Summary of results for DMA tests.

However, the mechanical properties decreased when the chitosan content exceeded 10% by weight. This could be due to the excessively high chitosan content causing particle agglomeration, which restricted the movement of the polymer chains, resulting in a reduction in the mechanical properties of the epoxy-acrylated coatings. DMA measurements were performed on multiple specimens taken from different regions of each film. The resulting curves showed negligible variation, with overlapping E’, ultimate strength, and fracture values. Since DMA is an intrinsic thermomechanical characterization method with very low sample-to-sample variability under identical curing conditions, statistical spread was below the instrumental resolution, and error bars would have overlapped with the mean curve. Therefore, a representative DMA curve for each formulation is reported.

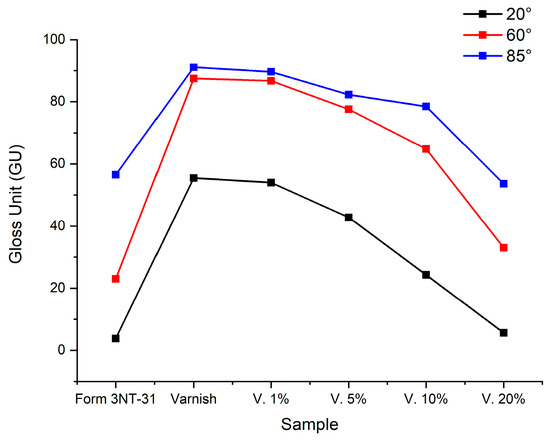

3.5. Gloss Measurement

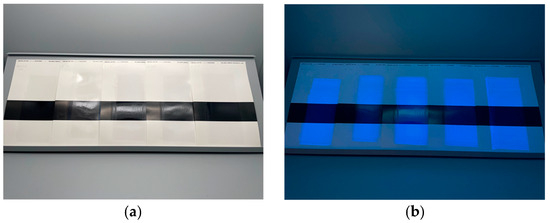

The gloss measurement was performed at three different angles (20°, 60° and 85°) of the varnish and the chitosan varnish printed on a standard substrate (Form 3NT-31) as shown in Figure 7. It is observed that, once the different samples were applied to the substrate, the gloss decreases as the chitosan concentration in the varnish increases, giving the surface a matte appearance at a concentration of 20% w/w. The gloss values obtained according to the criteria of the ASTM D 523 standard are presented in Figure 8 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Determination of gloss value at 20°, 60° and 85° (GU) of the varnish and the chitosan varnish printed on a standard substrate (Form 3NT-31).

Figure 7.

Samples printed with an Anilox roller of 200 lines per inch and a volume of 6.8 BCM under light (a) D65 lamp and (b) UV lamp at 365 nm.

Figure 8.

Gloss value of epoxy-acrylated/chitosan films measured at 20°, 60° and 85° (GU).

At concentrations below 5% by weight, chitosan disperses better in the epoxy-acrylate matrix; the surface remains homogeneous, and the gloss decreases slightly due to small changes in surface tension. At 10% chitosan, microphase separation may occur between the epoxy-acrylate matrix and the chitosan, creating a rougher surface at the microscopic level, which results in a significant decrease in specular gloss. Finally, at concentrations of 20% w/w, chitosan tends to agglomerate and partially migrate to the surface during curing. Visible irregularities and matte areas are formed, causing the specular gloss to drop dramatically, resulting in a satin or matte appearance. As expected, chitosan improves mechanical properties but reduces the gloss finish.

4. Conclusions

Chitosan-modified varnish films were produced at different concentrations and evaluated through DSC, DMA, and gloss measurements. The results indicate that formulations containing 1% and 5% w/w chitosan exhibit improved thermal and mechanical behavior compared to higher concentrations (10% and 20% w/w), showing greater toughness, lower rigidity, and ductility closer to the reference varnish. Their optical appearance was also minimally affected, maintaining translucency and gloss. Therefore, further experimental work will focus on formulations within the 1%–5% w/w range, as these concentrations do not compromise the functional mechanical or surface properties required for banknote coatings. Since this first stage aimed solely at assessing physicochemical feasibility, subsequent phases of the project will incorporate standardized evaluations of antimicrobial activity, as well as durability tests including accelerated aging, abrasion resistance, humidity exposure, adhesion, and UV stability. These forthcoming studies will help determine the full practical applicability of chitosan-containing UV-curable varnishes for secure document coatings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/coatings15121393/s1, Figure S1. For film formation, a four-sided wet-film applicator from Biuged Instruments was used. It is designed based on the ASTM D823 standard used in the "Standard Practices for Producing Films of Uniform Thickness of Paint, Coatings, and Related Products on Test Panels. (a) Drag bed assembly for film preparation, and (b) Assembly prior to dragging the varnish with the applicator. Figure S2. (a) The formed film is cured in the IGT Ak-tiprint UV equipment, for which the glass is placed on the equipment’s conveyor belt and the speed is set to 10 units of what the potentiometer indicates. (b) Once the film is cured, it is removed from the glass with the help of a straight, single-edged blade, positioning said blade at an angle of 30° with respect to the glass and ensuring that the blade never comes off the surface until the film is completely detached from the glass. Figure S3. (a) Measurement was performed on samples printed using the Harper Scientific Handproofer Phantom Flexo UV equipment. (b) the gloss of the varnish and mixed varnishes were measured using a Neurtek NKG Trio glossmeter (20°/60°/85°). Figure S4. FTIR spectrum of (a) varnish and blended varnish at different concentrations, (b) films made from the varnish and blended varnish at different concentrations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.C. and S.B.R.; methodology, G.G.C., S.B.R., G.M.d.O.R., L.C.C.-C., M.D.B.-A. and A.B.-M.d.O.; software, G.G.C. and S.B.R.; validation, G.G.C., S.B.R., G.M.d.O.R. and L.C.C.-C.; formal analysis, G.G.C., M.D.B.-A. and S.B.R.; investigation, G.G.C., S.B.R., G.M.d.O.R. and L.C.C.-C.; resources, G.G.C., S.B.R., M.D.B.-A. and G.M.d.O.R.; data curation, G.G.C. and S.B.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.C., S.B.R. and A.B.-M.d.O.; writing—review and editing, G.G.C., S.B.R., G.M.d.O.R., L.C.C.-C. and A.B.-M.d.O.; visualization, G.G.C., S.B.R., G.M.d.O.R. and L.C.C.-C.; supervision, G.G.C. and S.B.R.; project administration, G.G.C. and S.B.R.; funding acquisition, G.G.C. and S.B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Gerardo Granados Cerecero and Sergio Barrientos Ramírez acknowledges the financial support from Catedra DESC/Universidad Anáhuac México (Proyect N°PI0000334).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edo, G.I.; Ndudi, W.; Ali, A.B.M.; Yousif, E.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Opiti, R.A.; Athan Essaghah, A.E. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties, Solubility, Functional Technologies, Food and Health Applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 550, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Castaño, C.; Bolaños, G. Solubility of Chitosan in Aqueous Acetic Acid and Pressurized Carbon Dioxide-Water: Experimental Equilibrium and Solubilization Kinetics. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 151, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M.; Pavlov, G.; Desbrières, J. Influence of Acetic Acid Concentration on the Solubilization of Chitosan. Polymer 1999, 40, 7029–7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, J.D.; Rivas, B.L. Direct Ionization and Solubility of Chitosan in Aqueous Solutions with Acetic Acid. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 1465–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Z.; Srinivasan, S.; Akter, S. CTX-M-127 with I176F Mutations Found in Bacteria Isolates from Bangladeshi Circulating Banknotes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, T.L.; Kirchhoff, L.; Brüggemann, Y.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, J.; Steinmann, E. Stability of Pathogens on Banknotes and Coins: A Narrative Review. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleboudy, A.A.F.; Elagoz, M.A.; Simonian, G.N.; Hasanin, M. Biological Factors Affecting the Durability, Usability and Chemical Composition of Paper Banknotes in Global Circulation. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 2337–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todt, D.; Meister, T.L.; Tamele, B.; Howes, J.; Paulmann, D.; Becker, B.; Brill, F.H.; Wind, M.; Schijven, J.; Heinen, N. A Realistic Transfer Method Reveals Low Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission via Contaminated Euro Coins and Banknotes. iScience 2021, 24, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S.; Roy, P.C.; Ferdaus, A.; Ibnat, H.; Alam, A.S.M.R.U.; Nigar, S.; Jahid, I.K.; Hossain, M.A. Prevalence and Stability of SARS-CoV-2 RNA on Bangladeshi Banknotes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milosavljevi, M.; Okanovi, M.; Cicvari Kosti, S.; Jovanovi, M.; Radoni, M. COVID-19 and Behavioral Factors of e-Payment Use: Evidence from Serbia. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, S.; Ciric, L.; Cloutman-Green, E. COVID-19 Pandemic -Let’s Not Forget Surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 790–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Gámez, J.; Tejeda-Villarreal, P.N.; Macías-Cárdenas, P.; Canizales-Oviedo, J.; Garza-González, E.; Ramírez-Villarreal, E.G. Microbial Contamination in 20-Peso Banknotes in Monterrey. J. Environ. Health 2012, 75, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Szadkowski, B.; Liwka-Kaszyska, M.; Marzec, A. Bioactive and Biodegradable Cotton Fabrics Produced via Synergic Effect of Plant Extracts and Essential Oils in Chitosan Coating System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Alfadil, N.A.; Suliman Mohamed, M.; Ali, M.M.; El Nima, E.A.I. Characterization of Pathogenic Bacteria Isolated from Sudanese Banknotes and Determination of Their Resistance Profile. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 4375164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, A.A.E.-R.E.; Aydemir, C.; Özsoy, S.A.; Yenidoan, S. Drying Methods of the Printing Inks. J. Graph. Eng. Des. 2021, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossin, R.; Lavoratti, A.; Cercena, R.; Gonçalves Dal-Bó, A.; Zimmermann, M.V.G.; Zattera, A.J. Influence of Different Photoinitiatiors in the UV-LED Curing of Polyester Acrylated Varnishes. J. Coat. Tech. Res. 2023, 20, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnari, I.; Bolana Mirkovi, I.; Golubovi, K. Influence of UV curing varnish coating on surface properties of paper. Teh. Vjesnik 2012, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, C.; Gui, Q. Preparation and Properties of UV Curing Varnish Suited for Various Substrates. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 457, 115864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.I.; Christensen, L.; Baron, E.; Ahmad, S.I. Ed Ultraviolet Light in Human Health, Diseases and Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Borysiuk, P.; Derda, M.; Auriga, R.; Boruszewski, P.; Monder, S. Comparison of Selected Properties of Varnish Coatings Curing with the Use of UV and UV-LED Approach. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. 2015, 92, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Montes De Oca-Vásquez, G.; Esquivel-Alfaro, M.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R.; Jiménez-Villalta, G.; Romero-Arellano, V.H.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B. Development of Nanocomposite Chitosan Films with Antimicrobial Activity from Agave Bagasse and Shrimp Shells. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, M.; Huang, C.-C.; Chang, C.-W.; Lu, K.-H. Trends in Chitosan-Based Films and Coatings: A Systematic Review of the Incorporated Biopreservatives, Biological Properties, and Nanotechnology Applications in Meat Preservation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 42, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Amirabad, L.; Jonoobi, M.; Mousavi, N.S.; Oksman, K.; Kaboorani, A.; Yousefi, H. Improved Antifungal Activity and Stability of Chitosan Nanofibers Using Cellulose Nanocrystal on Banknote Papers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 189, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarayneh, S.; Sepahi, A.A.; Jonoobi, M.; Rasouli, H. Comparative Antibacterial Effects of Cellulose Nanofiber, Chitosan Nanofiber, Chitosan/Cellulose Combination and Chitosan Alone against Bacterial Contamination of Iranian Banknotes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasannamedha, G.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Shivaani, S.; Shankar, V.; Vo, D.-N.; Rangasamy, G. A Critical Review on the Fabrication of Chitosan Films from Marine Wastes. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 7551–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Saini, P.; Iqbal, U.; Sahu, K. Edible Microbial Cellulose-Based Antimicrobial Coatings and Films Containing Clove Extract. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.A.; Le, Y.N.; Pham, N.Q.; Ton-That, P.; Van-Xuan, T.; Ho, T.G.; Nguyen, T.; Phuong, H.H.K. Fabrication of Antimicrobial Edible Films from Chitosan Incorporated with Guava Leaf Extract. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeze, P.; van Gelder, A.T.; De Nederlandsche Bank, N.V. The Effect of Coating on the Durability of Banknotes; De Nederlandsche Bank: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bobu, E.; Nicu, R.; Obrocea, P.; Ardelean, E.; Dunca, S.; Balaes, T. Antimicrobial properties of coatings based on chitosan derivatives for applications in sustainable paper conservation. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Fatmawati, A.; Suseno, N.; Savitri, E.; Masui, G.; Ivony, F. Chitosan-Based Coating Application to Enhance Antimicrobial and Water Vapor Barrier Properties of Industry-Manufactured Paper. J. Kim. Sains Dan. Apl. 2024, 27, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Patel, R.; Padhan, B.; Palimkar, S.; Galgali, P.; Adhikari, A.; Varga, I.; Patel, M. Chitosan Based Biodegradable Composite for Antibacterial Food Packaging Application. Polymers 2023, 15, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noè, C.; Zanon, M.; Arencibia, A.; López-Muñoz, M.; Fernández de Paz, N.; Calza, P.; Sangermano, M. UV-Cured Chitosan and Gelatin Hydrogels for the Removal of As(V) and Pb(II) from Water. Polymers 2022, 14, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Han, G.; Kim, J.; Noh, S.; Lee, J.; Ito, Y.; Son, T. Visible and UV-curable chitosan derivatives for immobilization of biomolecules. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, G. Methacrylated Chitosan Based UV Curable Support for Enzyme Immobilization. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pilch-Pitera, B.; Krawczyk, K.; Kędzierski, M.; Pojnar, K.; Lehmann, H.; Czachor-Jadacka, D.; Bieniek, K.; Hilt, M. Antimicrobial Powder Coatings Based on Environmentally Friendly Biocides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 10325–10339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajczak, E.; Tylkowski, B.; Constantí, M.; Haponska, M.; Trusheva, B.; Malucelli, G.; Giamberini, M. Preparation and Characterization of UV-Curable Acrylic Membranes Embedding Natural Antioxidants. Polymers 2020, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, A.; Wazarkar, K.; Sabnis, A. Antimicrobial UV curable wood coatings based on citric acid. Pigment. Resin. Technol. 2021, 50, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaifan, A.K.; Alfadul, H.; Albuaimi, M.S.; Alrebaish, A.S.; Al-Gawati, M. Scalable Flexographic Printing of Graphite/Carbon Dot Nanobiosensors for Non-Faradaic Electrochemical Quantification of IL-8. Talanta 2025, 295, 128371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hafian, E.A.; Elgannoudi, E.S.; Mainal, A.; Yahaya, A.H.B. Characterization of Chitosan in Acetic Acid: Rheological and Thermal Studies. Turk. J. Chem. 2010, 34, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Amaral Sobral, P.J.; Gebremariam, G.; Drudi, F.; De Aguiar Saldanha Pinheiro, A.C.; Romani, S.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M. Rheological and Viscoelastic Properties of Chitosan Solutions Prepared with Different Chitosan or Acetic Acid Concentrations. Foods 2022, 11, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorski, D.; Gzyra-Jagiea, K.; Draczyski, Z. The Kinetics of Chitosan Degradation in Organic Acid Solutions. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovina, S.Z.; Vikhoreva, G.A. Polysaccharide-based polymer blends: Methods of their production. Glycoconj. J. 2006, 23, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D823-18(2022); Standard Practices for Producing Films of Uniform Thickness of Paint, Coatings and Related Products on Test Panels. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D523-14(2018); Standard Test Method for Specular Gloss. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Macea, R.B.; De Hoyos, C.F.; Montes, Y.G.; Fuentes, E.M.; Ruiz, J.I.R. Síntesis y Propiedades de Filmes Basados En Quitosano/Lactosuero. Polímeros 2015, 5, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hernández Cocoletzi, H.; Águila Almanza, E.; Flores Agustin, O.; Viveros Nava, E.L.; Ramos Cassellis, E. Obtención y caracterización de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón. Superf. Y Vacío 2009, 22, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Ge, Q.; Sun, Z. The Curing Characteristics and Properties of Bisphenol A Epoxy Resin/Maleopimaric Acid Curing System. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.-G.; Wang, Z.-P.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yue, N. Research on Properties of Silicone-Modified Epoxy Resin and 3D Printing Materials. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 23044–23050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczyk, P.; Mozelewska, K.; Nowak, M.; Czech, Z. Photocurable Epoxy Acrylate Coatings Preparation by Dual Cationic and Radical Photocrosslinking. Materials 2023, 14, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout, S.; Pradhan, S.; Mohanty, S. Evaluation of Modified Organic Cotton Fibers Based Absorbent Article Applicable to Feminine Hygiene. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 12814–12828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, T.Y.; El-Soda, M.; Ebrahim, H.S.; Gabr, A.M.M.; Hussein, M.H. Lady Rosetta Potato Farming: In Vitro Exploration of Chitosan and Derivatives for Multiplication, Microtuber Induction, and Somaclonal Variation Detection. Egypt. J. Bot. 2025, 65, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarger-Andre, S.; Domard, A. Chitosan carboxylic acid salts in solution and in the solid state. Carbohydr. Polym. 1994, 23, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fila, K.; Podkościelna, B.; Szymczyk, K. The application of chitosan as an eco-filler of polymeric composites. Adsorption 2024, 30, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesh, B.; Tshai, K.Y.; Warrior, N. Thermal and Morphological Properties of Chitosan Filled Epoxy. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 627, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K.; Maegawa, T.; Takahashi, T. Glass transition temperature of chitosan and miscibility of chitosan/poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) blends. Polymer 2000, 41, 7051–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).