Abstract

A novel two-in-one sensor for both carbon dioxide and hydrogen detection has been obtained based on a hybrid heterostructure. It consists of a 30 nm thick TiO2 nanocrystalline film grown by atomic layer deposition (ALD), thermally annealed at 610 °C, and subsequently coated with bimetallic AgAu nanoparticles and covered with a PV4D4 nanolayer, which was thermally treated at 430 °C. Two types of gas response behaviors have been registered, as n-type for hydrogen gas and p-type semiconductor behavior for carbon dioxide gas detection. The highest response for carbon dioxide has been registered at an operating temperature of 150 °C with a value of 130%, while the highest response for hydrogen gas was registered at 350 °C with a value of 230%, although it also attained a relatively good gas selectivity at 150 °C. It is considered that a thermal annealing temperature of 610 °C is better for the properties of TiO2 nanofilms, since it enhances gas sensor sensitivity too. Polymer coating on top is also believed to contribute to a higher influence on selectivity of the sensor structure. Accordingly, to our previous research where PV4D4 has been annealed at 450 °C, in this research paper, a lower temperature of 430 °C for annealing has been used, and thus another ratio of cyclocages and cyclorings has been obtained. Knowing that the polymer acts like a sieve atop the sensor structure, in this study it offers increased selectivity and sensitivity towards carbon dioxide gas detection, as well as maintaining a relatively increased selectivity for hydrogen gas detection, which works as expected with Ag and Au bimetallic nanoparticles on the surface of the sensing structure. The results obtained are highly important for biomedical and environmental applications, as well as for further development of the sensor industry, considering the high potential of two-in-one sensors. A carbon dioxide detector could be used for assessing respiratory markers in patients and monitoring the quality of the environment, while hydrogen could be used for both monitoring lactose intolerance and concentrations in cases of therapeutic gas, as well as monitoring the safe handling of various concentrations.

Keywords:

polymer coating; PV4D4; TiO2; hydrogen; carbon dioxide; medical applications; thermal annealing 1. Introduction

As the global population continues to grow, so does its demand for energy, transportation and consumables, leading to a significant increase in air pollution and environmental degradation [1,2]. These factors lead to global environmental challenges, which not only affect ecosystems in general but also have a specific impact on human health and behavior [3,4]. To maintain air quality and control emissions effectively, there is a need for systems capable of accurate gas and pollutant detection [1,5,6,7]. To meet these growing demands, gas sensor research increasingly focuses on the interaction of nanostructures with gases and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), as nanostructures exhibit unique properties due to their nanometric dimensions [8], which makes them highly suitable for sensitive gas sensing devices. In particular, the detection of carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen (H2) gases is attracting substantial interest, not only from the scientific community, but also from various industrial fields, including energy, health care and medicine.

Carbon dioxide is a compound that plays a crucial role in a wide range of applications, making its monitoring an important aspect in various areas such as indoor and outdoor air quality monitoring [9,10], fire detection [11] or detection of incipient food spoilage [12,13]. Furthermore, carbon dioxide raises interest even in electrical vehicle safety, as a component found during battery vent-gas thermal runaway [14,15]. In the medical field and social assistance industry, the use of CO2 is also well-established [16,17,18]. It is, for example, used as an indicator for the respiratory and circulatory system in the human body, enabling the efficacy assessment of thrombolytic therapy [19] and even a footprint of anesthesia after different types of surgical operations [20]. However, blood gases such as CO2 are usually measured through blood sampling, which not only requires trained personnel but also poses an infection risk for the patient. Hence, development of a non-invasive monitoring technique, e.g., gas sensors, enabling the analysis of exhaled breath, has been a point of interest for several years, if not decades [16,21]. These interests are further amplified by global population growth and the associated health risks, as well as by recent pandemic crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, accurately monitoring carbon dioxide remains challenging. This has intensified interest in more complex metal oxide systems, such as lanthanum-containing structures [21,22], metal–TiO2–metal meta surfaces [23] and polymer-coated fiber Bragg gratings [22]. Furthermore, methods for CO2 detection using different sensors with liquid or paste-like electrolytes have been developed [24].

Hydrogen gas is widely recognized as a clean energy carrier [13,25]. Due to its high potential as an alternative to fossil fuels [26,27], hydrogen plays an active role in the automotive industry as fuel for electric cells [28], and is also used as fuel in space applications [29]. As such, effective hydrogen detection and monitoring systems are essential for the safe handling and application of hydrogen [13,26,30,31]. Beyond its energy-related applications, hydrogen has found use in various fields, such as the food industry. Here, hydrogen has been researched as a method for reducing natural senescence and microbial spoilage, thereby extending the shelf life of different products [32,33]. On the other hand, hydrogen’s potential has also been studied in the medical field [31]. A recent study investigated H2 as a potential biomarker for inflammatory bowel disease [34]. Other studies have focused on breath tests that link hydrogen with gastrointestinal disorders [35,36], while excessive levels are associated with lactose intolerance [37]. In recent years, hydrogen has been studied even as a preventive and therapeutic medical gas [38], improving the survival rate in zymosan-induced inflammation [39], as a means of alleviating sepsis-induced neuro-inflammation and cognitive impairment [40] and as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent for stress-related diseases [41]. Thus, although there are numerous hydrogen detectors [27], the wide range of application demands constant improvement and further development of new sensors [10].

To address these demands, various sensors have been proposed in recent studies [7,13,26,27]. Different concepts, such as Pd-decorated oxides [10,42], hybrid structures with Au nanoparticles [43,44] or both Pt and Au [45], have been investigated to improve gas sensing properties. In previous studies, we used Au nanoparticles on zinc oxide [44,46], Ag and Pt nanoparticles on titanium oxide [47], polymer coating of PV4D4 [47,48,49] and even a copolymer P(V3D3 + TFE) [50] structure based on PV3D3 [51] and PTFE [52,53] for improving selectivity and sensitivity. Polymer use on top of the sensor structure is also intended to solidify humidity resistance, as it is known that the response of TiO2 structures diminishes at certain relative humidity levels [54].

This study proposes a novel, two-in-one gas sensing device capable of detecting carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas, targeting applications in both the medical and industrial fields. To evaluate its gas sensing properties, similar devices have been tested with several gases and at different operating temperatures. The influence of polymer coating on top of the sensor and its structural changes through thermal annealing has been assessed by both FTIR analysis and experimental data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Fabrication

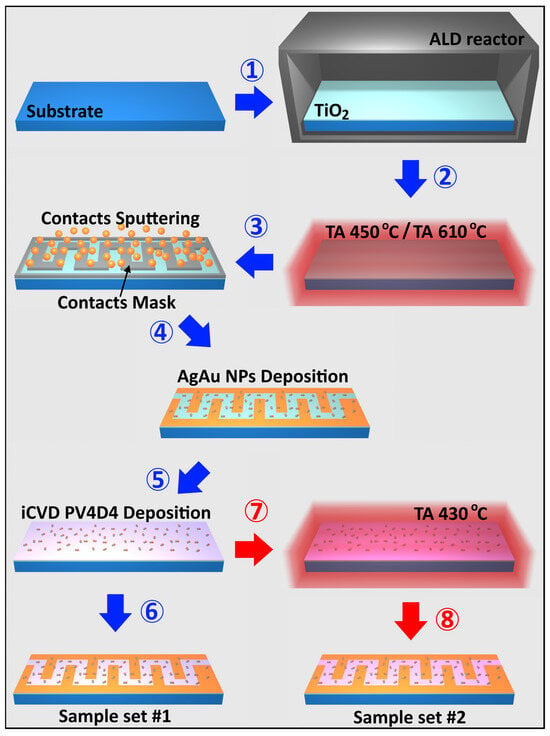

This paper presents gas sensing structures consisting of TiO2 nanolayers that underwent different thermal annealing regimes (450 °C, 610 °C). These nanolayers were subsequently covered with nanodots and coated with a polymeric film. The sample sets were obtained according to the fabrication steps described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fabrication steps for obtaining TiO2-based structures coated with AgAu nanoparticles and PV4D4 films.

The fabrication process is first prepared by cleaning the glass substrates (microscope glass slides of dimensions 76 mm × 25 mm × 1 mm, Thermo Scientific) with acetone, ethanol and a paper towel. TiO2 layers with a thickness of 30 nm were grown by atomic layer deposition (ALD), in a Picosun R-200 series reactor (Figure 1, step 1) [55]. Subsequently, the obtained samples were thermally processed at a temperature of 450 °C (Figure 1, step 2), after which Au contacts were sputtered on top of the structures through a meander-shaped mask (Figure 1, step 3). AgAu nanoparticles, in an atomic ratio of approximately 25% silver and 75% gold, as this ratio showed the best results for gas sensor tuning in previous papers [43,45,56,57], were deposited on the obtained surface using a specialized high-vacuum deposition system equipped with a custom-designed Haberland-type Gas Aggregation Source (GAS) with a custom multicomponent target, as reported in one of our previous works (Figure 1, step 4) [57]. SEM images can be observed in a previous publication, where the precision of manufacturing TiO2:Au has been proven [55]. The obtained sensors were coated with approximately 25 nm poly(1,3,5,7-tetravinyl-1,3,5,7-tetramethylcyclotetrasiloxane) (PV4D4) polymer via initiated chemical vapor deposition (iCVD) using a custom-built reactor (Figure 1, step 5), resulting in sample set #1, which was analyzed without further heat treatment (Figure 1, step 6). Sample set #2, on the other hand, was obtained by thermal heating PV4D4-coated sensors to 430 °C (Figure 1, step 7, TA) to produce heat-treated samples, TA, for further analysis (Figure 1, step 8).

2.2. Sample Characterization

For chemical analysis, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed on approximately 400 nm thick reference samples. FTIR spectra were acquired using a Bruker INVENIO R spectrometer, (Bruker Optik GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). The measurements covered a wavenumber range of 7500 to 370 cm−1, with 32 scans recorded at a resolution of 4 cm−1. For detailed analysis, a narrower range of 4000 to 700 cm−1 was selected.

The recorded FTIR data were processed using Origin (OriginLab 2024), where baseline correction (spline method), atmospheric compensation (CO2), normalization and smoothing (Savitzky–Golay method) were applied.

The gas sensing properties of the two sets of samples were calculated accordingly for the two types of response. As is well-known, electrical charge carriers in semiconductors can be of two types: holes and electrons. Therefore, two types of response have been registered: p-type for sensors where electrical resistance is rising and electrical current decreases to lower levels, and vice versa for n-type behavior, also mentioned in a previous work [58]. For the n-type response, formulas from a previous article have been used [48].

For p-type behavior, calculations are represented in Equation (1), where gas response S has been determined using the ratio of electrical resistances in air (Rair) and during gas exposure (Rgas), respectively.

The gas response of the developed samples was measured by using a custom-built setup and protocol, based on a computer-controlled source meter (Keithley 2400, Keithley, Cleveland, OH, USA), as previously described [59]. During measurements, the samples were heated to different operating temperatures (OPTs), while gases such as hydrogen, n-butanol, 2-propanol, ethanol, acetone, ammonia, carbon dioxide and methane were introduced into the chamber to maintain a gas concentration of 100 ppm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR Characterization

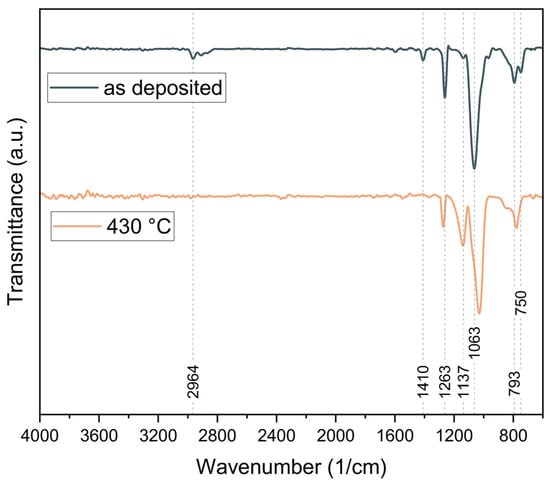

As shown in Figure 2, the FTIR spectrum of the as-deposited PV4D4 film indicates successful polymerization, as there are no significant bands above 3000 cm−1, associated with unreacted vinyl groups. The formation of the polymer backbone through reacted vinyl groups contributes to the C-H stretching band at 2964 cm−1 and lower, associated with sp3-hybridized carbon atoms.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectrum of the as deposited PV4D4 thin film and after thermal annealing at 430 °C.

After thermal annealing at 430 °C, the C-H-associated bands in the FTIR spectrum nearly vanish, indicating a change in the polymer’s structure. This is further supported by the shift in the siloxane ring-associated band to a lower wavenumber (1030 cm−1), as well as by the appearance of a pronounced band at 1137 cm−1.

Additionally, the preservation of the tetrasiloxane ring structure is confirmed by the dominant Si–O–Si asymmetric stretching band at 1063 cm−1. Further bands at 750 cm−1, 1263 cm−1 and 1410 cm−1 can be attributed to Si–CH3 modes, including rocking, bending and deformation of the methyl groups [60].

Additionally, the emergence of a band at 779 cm−1, in combination with the reduction in the asymmetric Si-C stretching (at 750 cm−1) and methyl rocking band (793 cm−1) suggests, according to Trujillo et al. [61], the formation of O3Si(CH3) environments. These spectral changes are consistent with the literature and indicate the conversion of the polymer’s initial siloxane ring structure into a silsesquioxane-cage-like structure, due to thermal treatment [61].

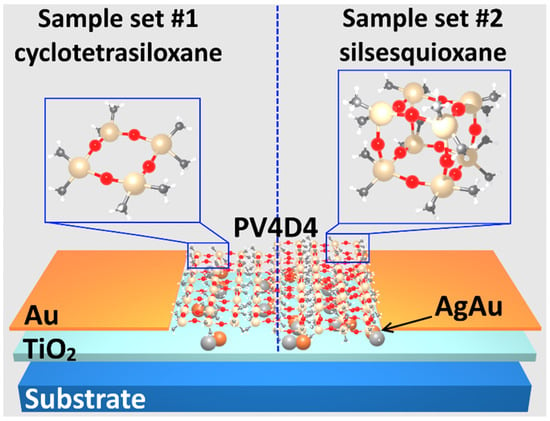

In Figure 3 we propose a conceptual design for the visualization of the obtained samples in a cross-section. As observed, in the first sample set #1, the coated polymer has a cyclo structure, while the second sample set #2 is in cage structure, as a result of thermal annealing at 430 °C.

Figure 3.

Samples representation in cross-section of TiO2 structures coated with PV4D4 before (cyclotetrasiloxane) and after (silsesquioxane) heat treatment.

3.2. Sensory Properties

The gas response of the sample was measured using a custom setup and protocol based on a computer-controlled source-meter (Keithley 2400) described previously, including more detailed parameters such as flow, concentrations and equations for obtaining the performances of the specimens [47,50,59,62].

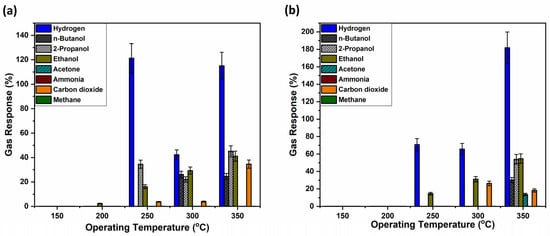

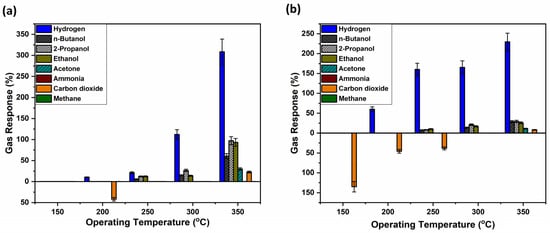

Figure 4a shows that the untreated sample, sample set #1, has high selectivity for hydrogen gas. However, the typical trend in metal oxide-based sensors of increasing gas response with increasing OPT is not observed. The highest gas response was registered at an operating temperature of 250 °C, followed closely by the response at 350 °C, with 120% and 110%, respectively. One possible explanation could be that the polymer structure gradually changes with increasing operating temperature, resulting in a mixture of structural features that could lead to reduced gas permeability and partial blockage of the sensor layer. At even higher operating temperatures, the transformation from the ring to a cage-like structure within the polymer is potentially further advanced, leading to again more accessible gas pathways and higher gas responses. This structural transition could explain the observed gas response. However, this phenomenon requires further investigation.

Figure 4.

Gas response of the hybrid sensors based on TiO2 layers thermally annealed at 450 °C, covered with AgAu nanoparticles and polymers measured for different gases and operation temperatures with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings on top. Samples with untreated polymer coating (a); and with polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C (b).

Apart from hydrogen, other gas responses were also registered for 2-propanol, ethanol, n-butanol and carbon dioxide, with significantly lower gas responses, however. Also, it is important to mention that the complex response in Figure 4a is not a commonly met bell-shaped curve, as usually observed in previous research [48,49,50]. Considering that TiO2 nanostructures can be achieved in different crystalline states, such as anatase and rutile [63], so thermal annealing at 450 °C caused TiO2 to crystallize to anatase [64], which might be the cause between the difference in gas response, as at 610 °C TiO2 is transitioning to the rutile phase [64]. Therefore, TiO2 thermally annealed at 450 °C, in combination with the coated polymer, supposedly showed altered pathways between the gas and the transiting oxygen species [65] from 250 to 300 to 350 °C at the surface of the sensor structure.

Figure 4b, on the other hand, presents the gas responses of a polymer-coated sample that was thermally annealed at 430 °C prior to gas exposure. When comparing both samples, sets #1 and #2, at an operating temperature of 250 °C, it can be observed that hydrogen selectivity increased and response to the 2-propanol and carbon dioxide vanished, yet improvement in sensitivity was not attained. At a higher operating temperature of 350 °C, the annealed sample registered a significantly higher response to hydrogen gas (180%). This indicates that thermal treatment enhances both selectivity and sensitivity, particularly at elevated temperatures, making the sensor more effective for hydrogen gas detection under such conditions.

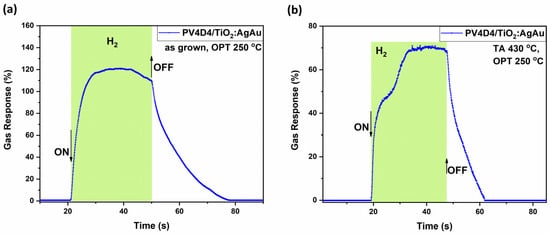

To better understand the key performance characteristics of this sample set, the highest gas responses from both annealed and as-deposited samples were selected for further analysis, focusing specifically on their dynamic response behavior. As shown in Figure 5a, for the sample with untreated polymer operated at 250 °C, a response of approximately 120% is registered. It is a stable response, with low saturation, a response time τres of ~5 s and recovery time τrec of ~20 s. On the other hand, Figure 5b shows the corresponding dynamic response of the annealed sample, which exhibits a lower maximal response, with a peak of 70%, yet demonstrates a faster recovery time (τrec ~ 10 s).

Figure 5.

Dynamic response of the hybrid sensors based on TiO2 layers thermally annealed at 450 °C to hydrogen gas measured at an operating temperature of 250 °C with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings on top. Samples with untreated polymer coating (a); and with polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C, sample set #2 (b).

As shown in Figure 6a, the sample set #1 with the untreated polymer operated at 430 °C registers a response of about 115% at its peak, while it slowly stabilizes itself at about 62%. It is a response with fast saturation, a response time of τres ~ 1.8 s and a recovery time τrec ~ of more than 40 s. On the other hand, the corresponding annealed sample set #2 (Figure 6b) shows a higher response, with a peak at 220%, yet faster saturation, stabilizing itself at about 48%. In comparison with Figure 5a, elevated operation temperatures lead to a decreased response time τres ~ 1.5 s and recovery time τrec ~ 1.8 s. This might occur due to the dependency of surface kinetics on operating temperature; thus, at higher operating temperature, the surface kinetics shows faster reactions [66,67].

Figure 6.

Dynamic response of the hybrid sensors based on TiO2 layers thermally annealed at 450 °C to hydrogen gas measured at an operating temperature of 350 °C with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings. Samples with untreated polymer coating, #1, (a); and # 2 with polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C (b).

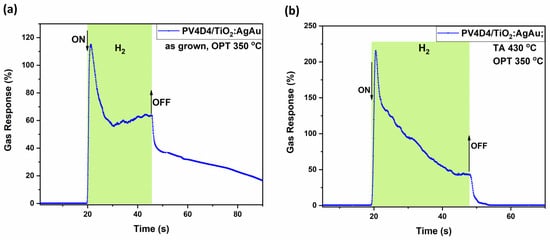

Figure 7 shows another set of samples, where this time 30 nm of TiO2 films, as the base of the sensor, has been thermally annealed at 610 °C in air, a temperature which showed the best performance in the treatment of TiO2 structures for higher gas response, as observed in our previous research works [47,49]. Gas responses have been plotted in both upward and downward directions along the y-axis to distinguish between different types of sensor behavior. The upward responses correspond to n-type behavior, which is characteristic of pristine TiO2-based sensors. In contrast, the downward responses indicate p-type behavior, which is attributed to the influence of Ag–Au bimetallic nanoparticles deposited on the surface of the sensor structure.

Figure 7.

Gas responses of the hybrid sensor structures based on TiO2 films thermally annealed at 610 °C versus different gases and operation temperatures with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings on top. Samples with untreated polymer coating (a); and with polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C (b).

Figure 7a shows that annealing of the sensing structure at 610 °C leads to an increased selectivity for both hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide. However, carbon dioxide promotes a p-type behavior response at an operating temperature of 200 °C, with a gas response of 43%. The highest response to hydrogen gas was registered at an operating temperature of 350 °C, with a response value of 300%, with increased selectivity and sensitivity in comparison with other registered responses for butanol, 2-propanol, ethanol, acetone and carbon dioxide at the same temperature.

More data regarding this exclusive sample can be observed in Figure S1, where various tests at different relative humidity and concentrations have been made regarding the hydrogen response.

On the other hand, Figure 7b shows an even better selectivity for both hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Thermally annealing the polymer-coated sample provided a trade-off between decreased sensitivity and increased selectivity. Thus, although the highest response to hydrogen gas is measured at 350 °C, the value has slightly decreased to 230%. At other operating temperatures, however, the response to hydrogen gas increased compared to the untreated sample. Specifically, responses of 175% at 300 °C, 160% at 250 °C, and 60% at 150 °C were recorded.

Regarding carbon dioxide, its response behavior remained p-type for operating temperatures between 150 °C and 250 °C and shifted to n-type behavior at 350 °C. Other responses were 40% at 200 °C and 35% at 250 °C. As observed, p-type response behavior was registered exclusively for carbon dioxide, indicating high selectivity towards this gas. An interesting transition from p-type to n-type behavior is observed as the operating temperature increases, a phenomenon that requires further investigation. While TiO2 is considered an n-type semiconductor, recent studies, such as this proposed paper, report that it might exhibit both n- and p-type properties [68,69,70] while others have reported various materials having this transitory behavior [71,72]. Among the proposed reasons are either increasing its lattice oxygen activity or the incorporation of acceptor-type ions; in the case of Nowotny et al. [68], chromium was used, while in this study, Ag and Au bimetallic nanoparticles have been used.

At 150 °C, high selectivity for hydrogen gas was achieved; however, it was decided to investigate the dynamic response at 350 °C, as this was the best response.

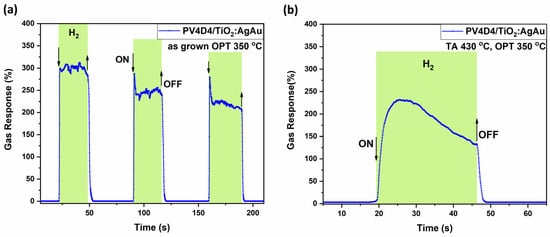

Figure 8 presents the highest gas responses to hydrogen for both thermally treated and untreated polymer coating samples. Figure 8a shows the dynamic response to hydrogen gas of a hybrid sensor with an untreated polymer coating at an operating temperature of 350 °C with a response value of 300%, τres ~ 0.7 s and τrec ~ 1.5 s registered from first pulse, with bias voltage of 1.35 V from the source-meter. In Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials, it can be observed that aging measurements eventually show a decrease in response after more than 900 days.

Figure 8.

Dynamic response of the hybrid sensors based on TiO2 films thermally annealed at 610 °C to hydrogen gas at an operating temperature of 350 °C, with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings on top. Sample sets with untreated polymer coating (a); and with polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C (b).

Figure 8b shows the dynamic response to hydrogen gas for thermally treated polymer coating samples atop the gas sensing structure at an operating temperature of 350 °C. The registered response is 230% with response and recovery times of τres ~ 4 s and τrec ~ 3 s, respectively. While the difference in response magnitude and dynamics is notable, the heat-treated sample offers improved selectivity towards hydrogen at elevated operating temperatures, making it a reasonable trade-off between sensitivity and selectivity.

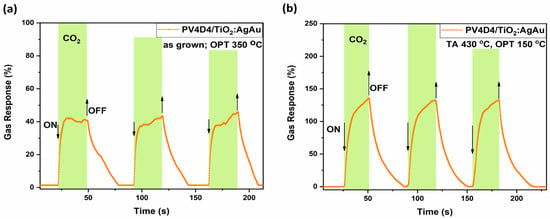

In Figure 9, the highest responses to carbon dioxide have been selected for both thermally treated and untreated polymer coating samples. Figure 9a shows the dynamic response to carbon dioxide of hybrid sensors with untreated polymer coating, with a response of 43%, τres ~ 1.4 s and τrec ~ 23 s registered from first pulse, at an operating temperature of 200 °C. Figure 9b shows the dynamic response to carbon dioxide for thermally treated polymer coating atop a gas sensing structure. The registered response is 130%, with τres ~ 3 s and τrec ~ 22 s.

Figure 9.

Dynamic response of the hybrid sensors based on TiO2 thermally annealed at 610 °C to carbon dioxide at different operating temperatures, with thermally treated and untreated polymer coatings atop. (a) Untreated polymer coating, OPT 200 °C; (b) polymer coating thermally treated at 430 °C, OPT 150 °C.

While the difference is considerable, it can be considered an acceptable trade for securing increased selectivity towards carbon dioxide at relative higher operating temperatures from 150 to 250 °C. This shift, decrease in OPT from 200 °C (untreated polymer) to 150 °C (thermally treated polymer), is highly beneficial for reducing the power consumption of portable sensing devices.

4. Discussion

Understanding the significance of the obtained results is best achieved through comparison with the existing literature. Therefore, a comparative overview has been compiled and organized accordingly. In Table 1, various hydrogen gas sensors are presented, while in Table 2, different carbon dioxide sensors utilizing comparable tuning methods are listed, allowing for a broader evaluation of performance across different material systems and sensor architectures.

Table 1.

Hydrogen detectors tuned by nanoparticles NPs and polymer coatings on top.

Table 2.

Carbon dioxide detectors tuned by nanoparticles NPs and polymer coatings.

Table 3 provides a small comparison of different studies where Ag and Au nanoparticles have been used for gas sensing. This comparison shows that the intended results, such as increased selectivity, can be tuned by functionalization. Thus, in this work, Au nanoparticles have the purpose of increasing CO2 detection.

Table 3.

Ag and Au NP influence on the performance of various metal oxides.

As observed, in the case of the proposed study, Ag and Au nanoparticles offer increased selectivity towards H2 and CO2, while in other research, the main focus is on 2-propanol and n-butanol. Furthermore, it can be observed that there are faster response and recovery times compared to other papers, and in the case of CO2 detection, there is also a lower operating temperature.

Based on the data presented in this study and taking into account previously published results [49], a gas detection mechanism for the developed sensor structures is proposed. For H2, a similar detection mechanisms has been proposed in a previous paper [49], involving a n-type response with electrons (e−). The notable distinction in this work lies in the addition of Ag and Au nanoparticles on the surface of the TiO2 sensing layer and their influence on the detection mechanism.

A mechanism for CO2 gas detection was proposed, based on the p-type response behavior of the sensor, involving a positive hole (p+). According to a previous study [82], different concentrations of holes manifest a resistance change in the sensor. The following formulas are proposed:

In Equation (2), k1 is reducing carbon dioxide in carbon monoxide.

In Equation (3) k2 is forming carbon dioxide.

In case of the metal oxide-based sensor, it is known that there are several oxygen species at the surface of sensing structure, dependent on various operating temperatures, as stated in different papers [49,83,84,85]. In this paper, for CO2, the operating temperatures presented were 150 °C and 350 °C, as shown in Figure 9; therefore, the oxygen species at the surface are, respectively, 2O− and O2−. Thus, the following equations are proposed as the gas sensing mechanism of CO2 for the proposed samples, according to this Equations (4)–(9) stated in [86].

Equation (8) represents the CO2 detection at 350 °C, while Equation (9) represents the detection at 150 °C. It is necessary to mention that the proposed mechanism is for gas molecules that pass through the polymer; therefore, it provides a rough idea for the adsorption process.

Taking into account the information published in a previous work regarding cyclo cage structures [47], as well as the current study, it can be concluded that the chosen annealing temperatures influence the degree of transition from a ring to a cage structure of the polymer. FTIR analysis indicates that annealing at 430 °C, as performed in this study, yields a lower distribution of cyclo cages relative to cyclo rings compared to the 450 °C used in previous studies.

This paper provides new insights into how polymer ultra-thin layers can be manipulated, thereby changing gas sensor properties. The novelty of this sensor is that it proposes new physical parameters for similar sensors based on TiO2; however, it has improved selectivity and sensitivity towards certain gases. In comparison with previous papers [47,48,49,50], in this work, the TiO2 base is thicker, with a rutile phase more sensitive to H2 detection, boosted with doped AgAu nanoparticles for CO2 detection. It was coated in PV4D4, which showed a different ratio of cyclo ring and cyclo cage pores, dependent on the thermal annealing of the polymer, for humidity resistance and better gas sensing properties. The ratio of ring and cage pores shows a severe impact on gas performance; as in previous work [47], the presence of a cage layer was found to influence selectivity and sensitivity, resulting in higher response levels towards hydrogen and acting as a molecular sieve for various gases. In contrast, this study shows that a lower distribution of cage structures within the polymer enables the tuning of selectivity towards CO2 with a p-type behavior response at 150 °C, while maintaining selectivity towards H2 for higher temperatures, ranging up to 350 °C.

Biomedical applications of this sensor include using it as an integrated component for capnometry. As mentioned in a recent article [87], the CO2 concentrations of one exhale is about 4% by volume, which corresponds to 40,000 ppm. Deviating data from this point could indicate either hypocapnia or hypercapnia in patients, caused by various factors such as panic attacks, respiratory failures, asthma, etc. [88]. Hydrogen, on the other hand, is found in lower concentrations. A recent study [89] showed there is a small variation in the H2 baseline range from 4 to 9 ppm regarding age, while it can be up to 20 ppm in the morning and 10 ppm later in the day. For the case of lactose intolerance, it is considered that an increase of 20 ppm above the base level shows a positive lactose test [90]. Another paper [91] showed that irritable bowel syndrome also shows an increase of 20 ppm above the baseline, as a result of fructose malabsorption.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel two-in-one sensor capable of detecting both hydrogen and carbon dioxide gas. Among the four investigated samples, the best-performing sensor was based on a TiO2 film, thermally annealed at 610 °C in air and functionalized with Ag Au bimetallic nanoparticles. The sensor was subsequently coated with a PV4D4 layer and annealed at 430 °C. For hydrogen gas, this sensor demonstrated n-type behavior, while for carbon dioxide, p-type behavior was observed. In addition, it showed a fast response and relatively fast recovery time, which was believed to be caused by a different ratio of cyclo cages and cyclo rings of PV4D4 formed on top of the sensor after thermal annealing.

It is strongly believed that precise thermal annealing of the PV4D4 in a specific temperature range allows for control of the ratio of cage to ring structures within the polymer. This enables tuning of the sensor’s selectivity and sensitivity through controlled changes in the sieve structures covering the underlying sensing layer. Furthermore, a decrease in operating temperature from 200 °C for the untreated polymer-coated sample to OPT of 150 °C for the thermally treated polymer-based sample set, is extremely beneficial for reducing the power consumption of portable sensing devices.

Due to these specific characteristics, it is possible to use the obtained sensor in environments where monitoring both of these gases is of interest. It can be even further tuned by simply thermally annealing at a certain temperature for a specific target gas.

The detection of hydrogen gas is important in the growing green energy industry and in biomedical diagnosis, as it has the potential to be a biomarker for various gastric diseases. Similarly, carbon dioxide is important as an industrial and medical gas used in various processes, as well as being a biomarker used in capnometry. Consequently, using one sensor type to measure both of these gases, as developed in this study, would be beneficial not only for the biomedical but also for the industrial sectors. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to better understand the underlying mechanisms and to determine its benefit for the detection of various targeted gases and their corresponding application niches. This type of two-in-one sensor opens up numerous possibilities for both research and practical use.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bios16010005/s1, Figure S1. Dynamic response of gas sensor to hydrogen of various concentrations (50, 100, 1000 ppm) at an operating temperature of 350 °C and to different relative humidity: (a) 17%; (b) 67%. Figure S2. Linear representation of Figure S1. Figure S3. Aging measurements of TiO2-based gas sensor, thermally annealed at 610° C, doped with AgAu nanoparticles and coated with a thin layer of PV4D4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., S.S. and O.L.; methodology, M.B. and L.S.; software, S.S., C.L., N.M. and N.A.; validation, F.F., A.V., S.S. and O.L.; formal analysis, C.L., N.M., M.C. and S.S.; investigation, M.B., C.L., L.S., N.M., M.C. and S.S.; resources, N.A. and F.F.; data curation, F.F., A.V., S.S., N.A. and O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., C.L., L.S. and S.S.; resources, N.A. and F.F.; writing—review and editing, M.B., C.L., L.S., O.L., A.V., F.F. and S.S.; visualization, M.B., C.L., M.C. and L.S.; supervision, N.A. and O.L.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported partially by the National AGENCY FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT through the Project «Hydrogen and optical wideband detectors based on semiconductor nano oxides» No. 24.80012.5007.15TC at the Technical University of Moldova.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nazpal, R.; Chiriac, M.; Sugihara, M.; Litra, D.; Ababii, N.; Magariu, N.; Lupan, C.; Zinicovschi, V.; Ameloot, R.; Lupan, O. Sensory Properties of CuO/Cu2O Nanostructures Coated with Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. In Proceedings of the 2024 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 14–15 November 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Deng, H.; Wu, X. The Negative Effect of Air Pollution on People’s pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Something in the Air: Pollution and the Demand for Health Insurance. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2018, 85, 1609–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Schröder, S.; Abdollahifar, M.; Magariu, N.; Offermann, J.; Schwäke, L.; Brinza, M.; Zimoch, L.; Tugulea, V.; Strunskus, T.; et al. Polymer-Coated Cd-Doped ZnO Nanostructures for Dual Sensing of Volatile Organic Compounds and Battery Vapours. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Nanotechnologies and Biomedical Engineering. (ICNBME 2025), Chisinau, Moldova, 7–10 October 2025; Sontea, V., Tiginyanu, I., Railean, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 284–300. ISBN 978-3-032-06494-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litra, D.; Chiriac, M.; Ababii, N.; Lupan, O. Acetone Sensors Based on Al-Coated and Ni-Doped Copper Oxide Nanocrystalline Thin Films. Sensors 2024, 24, 6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupan, O.; Nagpal, R.; Litra, D.; Brinza, M.; Sugihara, M.; Ameloot, R.; Railean, S.; Ameri, T.; Adelung, R.; Schröder, S.; et al. Hybrid Nanomaterials for Biomedical Sensors. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Nanotechnologies and Biomedical Engineering. (ICNBME 2025), Chisinau, Moldova, 7–10 October 2025; Sontea, V., Tiginyanu, I., Railean, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 162–176. ISBN 978-3-032-06494-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Brinza, M.; Schröder, S.; Ababii, N.; Strunskus, T.; Viana, B.; Pauporté, T.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F. Sensors Based on Hybrid Materials for Environmental, Industrial and Biomedical Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 14th International Conference Nanomaterials: Applications and Properties (NAP), Riga, Latvia, 8–13 September 2024. pp. MTFC09-1/MTFC09-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Lupan, C.; Bîrnaz, A.; Sereacov, A.; Greve, E.; Gronenberg, M.; Siebert, L.; Adelung, R.; Lupan, O. Multifunctional Three-in-One Sensor on t-ZnO for Ultraviolet and VOC Sensing for Bioengineering Applications. Biosensors 2024, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Leishman, M.; Bagnall, D.; Nasiri, N. Nanostructured Gas Sensors: From Air Quality and Environmental Monitoring to Healthcare and Medical Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Lupan, C.; Buzdugan, A.; Ghenea, V.; Lupan, O. Effect of Pd Functionalization on Optical and Hydrogen Sensing Properties of ZnO: Eu Films. Optik 2025, 325, 172247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohle, R.; Simon, E.; Schneider, R.; Fleischer, M.; Sollacher, R.; Gao, H.; Müller, K.; Jauch, P.; Loepfe, M.; Frerichs, H.-P.; et al. Fire Detection with Low Power Fet Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 120, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Jayas, D.S.; Sadistap, S. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Sensors for the Agri-Food Industry—A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009, 2, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, C.; Kohlmann, N.; Petersen, D.; Bodduluri, M.T.; Buzdugan, A.; Jetter, J.; Quandt, E.; Kienle, L.; Adelung, R.; Lupan, O. Hydrogen Nanosensors Based on Core/Shell ZnO/Al2O3 and ZnO/ZnAl2O4 Single Nanowires. Mater. Today Nano 2025, 29, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Stefanopoulou, A.G.; Siegel, J.B. Early Detection for Li-Ion Batteries Thermal Runaway Based on Gas Sensing. ECS Trans. 2019, 89, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Valecha, P.; Tran, V.; Engle, B.; Stefanopoulou, A.; Siegel, J. Detection of Li-Ion Battery Failure and Venting with Carbon Dioxide Sensors. eTransportation 2021, 7, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervieux, E.; Théron, M.; Uhring, W. Carbon Dioxide Sensing—Biomedical Applications to Human Subjects. Sensors 2021, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.; van der Linden, J. The Potential Use of Carbon Dioxide as a Carrier Gas for Drug Delivery into Open Wounds. Med. Hypotheses 2009, 72, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Betany, A.M.M.; Behiry, E.M.; Gumbleton, M.; Harding, K.G. Humidified Warmed CO2 Treatment Therapy Strategies Can Save Lives With Mitigation and Suppression of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: An Evidence Review. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 594295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, U.K.H.; Kurowski, V.; Giannitsis, E.; Katus, H.A.; Djonlagic, H. Effectiveness of End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide Tension for Monitoring of Thrombolytic Therapy in Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 3588–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGain, F.; Sheridan, N.; Wickramarachchi, K.; Yates, S.; Chan, B.; McAlister, S. Carbon Footprint of General, Regional, and Combined Anesthesia for Total Knee Replacements. Anesthesiology 2021, 135, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttmann, S.E.; Windisch, W.; Storre, J.H. Techniques for the Measurement and Monitoring of Carbon Dioxide in the Blood. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.Y.; Qiao, C.; Jia, Y. Carbon Dioxide Detection Using Polymer-Coated Fiber Bragg Grating Based on Volume Dilation Mechanism and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 584, 152616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Zhou, R.; Du, Z.; Ling, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Shao, J.; Luo, S.; Chen, D. A Dual-Band Carbon Dioxide Sensor Based on Metal–TiO2–Metal Metasurface Covered by Functional Material. Photonics 2022, 9, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.; Oelßner, W.; Zosel, J. Electrochemical CO2 Sensors with Liquid or Pasty Electrolyte. In Carbon Dioxide Sensing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, J.M.M.; Santos, D.M.F. The Hydrogen Color Spectrum: Techno-Economic Analysis of the Available Technologies for Hydrogen Production. Gases 2023, 3, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, W.J.; Post, M.B.; Burgess, R.; Rivkin, C. An Overview of Hydrogen Safety Sensors and Requirements. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchap, M.; Hashtroudi, H.; Thathsara, T.; Harrison, C.J.; Kingshott, P.; Kandjani, A.E.; Trinchi, A.; Shafiei, M. Exploring the Promise of One-Dimensional Nanostructures: A Review of Hydrogen Gas Sensors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1443–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurz, M.; Baltacioglu, E.; Hames, Y.; Kaya, K. The Meeting of Hydrogen and Automotive: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 23334–23346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R. An Overview of Industrial Uses of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1998, 23, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, C.; Mishra, A.K.; Wolff, N.; Drewes, J.; Krüger, H.; Vahl, A.; Lupan, O.; Pauporté, T.; Viana, B.; Kienle, L.; et al. Nanosensors Based on a Single ZnO:Eu Nanowire for Hydrogen Gas Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 41196–41207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Litra, D.; Mishra, A.K.; Lupan, C.; Nagpal, R.; Mishra, S.; Qiu, H.; Railean, S.; Lupan, O.; de Leeuw, N.H.; et al. Ultra-Selective Hydrogen Sensors Based on CuO-ZnO Hetero-Structures Grown by Surface Conversion. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.; Nenov, A.; Hancock, J.T. How Hydrogen (H2) Can Support Food Security: From Farm to Fork. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Santos-Carballal, D.; Magariu, N.; Mishra, A.K.; Ababii, N.; Krüger, H.; Wolff, N.; Vahl, A.; Bodduluri, M.T.; Kohlmann, N.; et al. Al2O3/ZnO Heterostructure-Based Sensors for Volatile Organic Compounds in Safety Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 29331–29344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Yakabe, K.; Seki, N.; Akiyama, M.; Uchida, K.; Kim, Y.-G. Hydrogen Gas and the Gut Microbiota Are Potential Biomarkers for the Development of Experimental Colitis in Mice. Gut Microbiome 2024, 5, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, J.J.; Pitcher, C.K.; Ferrandino, G.; Hobson, A.R.; Pappan, K.L.; Lawson, J.L.D. Breathing New Life into Clinical Testing and Diagnostics: Perspectives on Volatile Biomarkers from Breath. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2022, 59, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, K.; Wolfhagen, F.; Castel, R.; van de Werken, M.; Klerks, J.; Verheijen, F.; Vermeer, H.J. Testing for Lactase Non-Persistence in a Dutch Population: Genotyping versus the Hydrogen Breath Test. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Lab. Med. 2023, 60, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, S. Molecular Hydrogen as a Preventive and Therapeutic Medical Gas: Initiation, Development and Potential of Hydrogen Medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, K.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Pei, Y.; Xiong, L.; Hou, L.; Wang, G. Hydrogen Gas Improves Survival Rate and Organ Damage in Zymosan-Induced Generalized Inflammation Model. Shock 2010, 34, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Qin, C.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Xie, K.; et al. Hydrogen Gas Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Impairment through Regulation of DNMT1 and DNMT3a-Mediated BDNF Promoter IV Methylation in Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 95, 107583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Bajgai, J.; Fadriquela, A.; Sharma, S.; Trinh Thi, T.; Akter, R.; Goh, S.H.; Kim, C.-S.; Lee, K.-J. Redox Effects of Molecular Hydrogen and Its Therapeutic Efficacy in the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Processes 2021, 9, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Hung, C.M.; Ngoc, T.M.; Thanh Le, D.T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Nguyen Van, D.; Nguyen Van, H. Low-Temperature Prototype Hydrogen Sensors Using Pd-Decorated SnO2 Nanowires for Exhaled Breath Applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 253, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.G.; Vishnuraj, R.; Pullithadathil, B. Integrated Co-Axial Electrospinning for a Single-Step Production of 1D Aligned Bimetallic Carbon Fibers@AuNPs–PtNPs/NiNPs–PtNPs towards H2 Detection. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Postica, V.; Pauporté, T.; Hoppe, M.; Adelung, R. UV Nanophotodetectors: A Case Study of Individual Au-Modified ZnO Nanowires. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 296, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Hong, R.; Deng, X.; Tang, P.; Li, D. Hydrogen Sensing Properties of Pt-Au Bimetallic Nanoparticles Loaded on ZnO Nanorods. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Postica, V.; Wolff, N.; Su, J.; Labat, F.; Ciofini, I.; Cavers, H.; Adelung, R.; Polonskyi, O.; Faupel, F.; et al. Low-Temperature Solution Synthesis of Au-Modified ZnO Nanowires for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Nanosensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32115–32126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Brinza, M.; Piehl, J.; Ababii, N.; Magariu, N.; Zimoch, L.; Strunskus, T.; Pauporte, T.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F.; et al. Influence of Silsesquioxane-Containing Ultra-Thin Polymer Films on Metal Oxide Gas Sensor Performance for the Tunable Detection of Biomarkers. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.; Ababii, N.; Brînză, M.; Magariu, N.; Zimoch, L.; Bodduluri, M.T.; Strunskus, T.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F.; Lupan, O. Tuning the Selectivity of Metal Oxide Gas Sensors with Vapor Phase Deposited Ultrathin Polymer Thin Films. Polymers 2023, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinza, M.; Schröder, S.; Ababii, N.; Gronenberg, M.; Strunskus, T.; Pauporte, T.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F.; Lupan, O. Two-in-One Sensor Based on PV4D4-Coated TiO2 Films for Food Spoilage Detection and as a Breath Marker for Several Diseases. Biosensors 2023, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinza, M.; Schwäke, L.; Zimoch, L.; Strunskus, T.; Pauporté, T.; Viana, B.; Ameri, T.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F.; Schröder, S.; et al. Influence of P(V3D3-Co-TFE) Copolymer Coverage on Hydrogen Detection Performance of a TiO2 Sensor at Different Relative Humidity for Industrial and Biomedical Applications. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.; Ababii, N.; Lupan, O.; Drewes, J.; Magariu, N.; Krüger, H.; Strunskus, T.; Adelung, R.; Hansen, S.; Faupel, F. Sensing Performance of CuO/Cu2O/ZnO:Fe Heterostructure Coated with Thermally Stable Ultrathin Hydrophobic PV3D3 Polymer Layer for Battery Application. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 23, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brînză, M.; Lupan, C.; Schwäke, L.; Ababii, N.; Zimoch, L.; Sereacov, A.; Pauporté, T.; Schröder, S.; Adelung, R.; Faupel, F.; et al. Effect of PTFE Thickness on Gas Sensing Properties of TiO2/Pd-Doped ZnO Nanostructures. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Nanotechnologies and Biomedical Engineering. (ICNBME 2025), Chisinau, Moldova, 7–10 October 2025; Sontea, V., Tiginyanu, I., Railean, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switerland, 2025; pp. 275–283. ISBN 978-3-032-06494-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.; Brinza, M.; Cretu, V.; Zimoch, L.; Gronenberg, M.; Ababii, N.; Railean, S.; Strunskus, T.; Pauporte, T.; Adelung, R.; et al. A New Approach in Detection of Biomarker 2-Propanol with PTFE-Coated TiO2 Nanostructured Films. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Nanotechnologies and Biomedical Engineering. (ICNBME 2023), Chisinau, Moldova, 20–23 September 2023; Sontea, V., Tiginyanu, I., Railean, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtari, M.; Salehi, A.; Vollebregt, S. Effect of Temperature and Humidity on the Sensing Performance of TiO2 Nanowire-Based Ethanol Vapor Sensors. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 325501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupan, O.; Postica, V.; Ababii, N.; Reimer, T.; Shree, S.; Hoppe, M.; Polonskyi, O.; Sontea, V.; Chemnitz, S.; Faupel, F.; et al. Ultra-Thin TiO2 Films by Atomic Layer Deposition and Surface Functionalization with Au Nanodots for Sensing Applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2018, 87, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postica, V.; Vahl, A.; Magariu, N.; Terasa, M.-I.; Hoppe, M.; Viana, B.; Aschehoug, P.; Pauporte, T.; Tiginyanu, I.; Polonskyi, O.; et al. Enhancement in UV Sensing Properties of Zno:Ag Nanostructured Films by Surface Functionalization with Noble Metalic and Bimetallic Nanoparticles. J. Eng. Sci. 2018, 25, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahl, A.; Lupan, O.; Santos-Carballal, D.; Postica, V.; Hansen, S.; Cavers, H.; Wolff, N.; Terasa, M.-I.M.-I.; Hoppe, M.; Cadi-Essadek, A.; et al. Surface Functionalization of ZnO:Ag Columnar Thin Films with AgAu and AgPt Bimetallic Alloy Nanoparticles as an Efficient Pathway for Highly Sensitive Gas Discrimination and Early Hazard Detection in Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 16246–16264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, K.; Liu, K.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z. Metal Oxide Resistive Sensors for Carbon Dioxide Detection. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 472, 214758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Santos-Carballal, D.; Ababii, N.; Magariu, N.; Hansen, S.; Vahl, A.; Zimoch, L.; Hoppe, M.; Pauporté, T.; Galstyan, V.; et al. TiO2/Cu2O/CuO Multi-Nanolayers as Sensors for H2 and Volatile Organic Compounds: An Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 32363–32380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-471-85298-8. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, N.J.; Wu, Q.; Gleason, K.K. Ultralow Dielectric Constant Tetravinyltetramethylcyclotetrasiloxane Films Deposited by Initiated Chemical Vapor Deposition (ICVD). Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupan, O.; Ababii, N.; Mishra, A.K.; Bodduluri, M.T.; Magariu, N.; Vahl, A.; Krüger, H.; Wagner, B.; Faupel, F.; Adelung, R.; et al. Heterostructure-Based Devices with Enhanced Humidity Stability for H2 Gas Sensing Applications in Breath Tests and Portable Batteries. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 329, 112804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, Z.P.; Motaung, D.E.; Swart, H.C. Structural Transformation and Enhanced Gas Sensing Characteristics of TiO2 Nanostructures Induced by Annealing. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2018, 535, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokeser, E.A.; Esturk, U.; Kurnaz, S.; Ozturk, O. Revival of Quantum Confinement Effect and Stabilization of Tetragonal Phase in TiO2 Nanopowders with Annealing Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftyurek, E.; Li, Z.; Schierbaum, K. Adsorbed Oxygen Ions and Oxygen Vacancies: Their Concentration and Distribution in Metal Oxide Chemical Sensors and Influencing Role in Sensitivity and Sensing Mechanisms. Sensors 2022, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Liang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, K.; Yang, L.; Lou, X. From the Surface Reaction Control to Gas-Diffusion Control: The Synthesis of Hierarchical Porous SnO2 Microspheres and Their Gas-Sensing Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 15963–15976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, N.A.; Pikaar, I.; Biskos, G. Metal Oxide Semiconducting Nanomaterials for Air Quality Gas Sensors: Operating Principles, Performance, and Synthesis Techniques. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, J.; Macyk, W.; Wachsman, E.; Rahman, K.A. Effect of Oxygen Activity on the n–p Transition for Pure and Cr-Doped TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 3221–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Haidry, A.; Sun, L.; Saruhan, B.; Plecenik, A.; Plecenik, T.; Shen, H.; Yao, Z. Cost-Effective Fabrication of Polycrystalline TiO2 with Tunable n/p Response for Selective Hydrogen Monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 274, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosc, I.; Hotovy, I.; Rehacek, V.; Griesseler, R.; Predanocy, M.; Wilke, M.; Spiess, L. Sputtered TiO2 Thin Films with NiO Additives for Hydrogen Detection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 269, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.E. Semiconducting Oxides as Gas-Sensitive Resistors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1999, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurlo, A.; Sahm, M.; Oprea, A.; Barsan, N.; Weimar, U. A P- to n-Transition on α-Fe2O3-Based Thick Film Sensors Studied by Conductance and Work Function Change Measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 102, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Mao, P.; Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Han, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Han, M.; Liu, J.-M.; Wang, G. Pd Nanoparticle Film on a Polymer Substrate for Transparent and Flexible Hydrogen Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 44603–44613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.; Pyo, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, T. A Highly Sensitive Hydrogen Sensor with Gas Selectivity Using a PMMA Membrane-Coated Pd Nanoparticle/Single-Layer Graphene Hybrid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3554–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Mao, P.; Qin, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, B.; Wang, X.; Han, D.; Wang, G.; Song, F.; Han, M.; et al. Response Characteristics of Hydrogen Sensors Based on PMMA-Membrane-Coated Palladium Nanoparticle Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 27193–27201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Choi, S.-J.; Swager, T.M.; Walsh, G.F. Switchable Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube–Polymer Composites for CO2 Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 33373–33379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, W.-T.; Kim, Y.; Savagatrup, S.; Yoon, B.; Jeon, I.; Choi, S.-J.; Kim, I.-D.; Swager, T.M. Porous Ion Exchange Polymer Matrix for Ultrasmall Au Nanoparticle-Decorated Carbon Nanotube Chemiresistors. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 5413–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, H.; Heli, B.; Ajji, A. Cellulose Nanopaper Cross-Linked Amino Graphene/Polyaniline Sensors to Detect CO2 Gas at Room Temperature. Sensors 2019, 19, 5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willa, C.; Yuan, J.; Niederberger, M.; Koziej, D. When Nanoparticles Meet Poly(Ionic Liquid)s: Chemoresistive CO2 Sensing at Room Temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 2537–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, M.; Litra, D.; Lupan, C.; Lupan, O. Propanol Detection Device for the Purpose of Monitoring the Quality of the Environment. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 31, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupan, O.; Ababii, N.; Santos-Carballal, D.; Terasa, M.-I.M.-I.; Magariu, N.; Zappa, D.; Comini, E.; Pauporté, T.; Siebert, L.; Faupel, F.; et al. Tailoring the Selectivity of Ultralow-Power Heterojunction Gas Sensors by Noble Metal Nanoparticle Functionalization. Nano Energy 2021, 88, 106241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, G.F.; Cavanagh, L.M.; Afonja, A.; Binions, R. Metal Oxide Semi-Conductor Gas Sensors in Environmental Monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 5469–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Singh, M.; Comini, E. One-Dimensional Nanostructured Oxide Chemoresistive Sensors. Langmuir 2020, 36, 6326–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ogbeide, O.; Macadam, N.; Sun, Q.; Yu, W.; Li, Y.; Su, B.-L.; Hasan, T.; Huang, X.; Huang, W. Printed Gas Sensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1756–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Sinha, S.K. Studies on Nanomaterial-Based p-Type Semiconductor Gas Sensors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 24975–24986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.; Rayappan, J.B.B. Gas Sensing Mechanism of Metal Oxides: The Role of Ambient Atmosphere, Type of Semiconductor and Gases—A Review. Sci. Lett. 2015, 4, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, B.; Archer, J.; Orton, C.M.; Symons, H.E.; Watson, N.A.; Saccente-Kennedy, B.; Philip, K.E.J.; Hull, J.H.; Costello, D.; Calder, J.D.; et al. Relationship between Exhaled Aerosol and Carbon Dioxide Emission Across Respiratory Activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 15120–15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, F.; Volpe, C.; Gargaruti, R.; Poscia, A.; Di Donato, M.; Grieco, G.; Moscato, U. Effects of Acute Hypoventilation and Hyperventilation on Exhaled Carbon Monoxide Measurement in Healthy Volunteers. BMC Pulm. Med. 2009, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, E.; Sandúa, A.; Calleja, S.; Deza, S.; González, Á. Modification of Baseline Status to Improve Breath Tests Performance. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C. How to Interpret Hydrogen Breath Tests. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 17, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior, C.; Gourcerol, G.; Déchelotte, P.; Leroi, A.-M.; Ducrotté, P. Symptomatic Fructose Malabsorption in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Prospective Study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2014, 2, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.