Biosensors for Detection of Labile Heme in Biological Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biological Functions of Heme

2.1. Heme Interaction with Proteins

2.2. Heme-Mediated Oxygen Transport: Hemoglobin

3. Heme-Related Blood Disorders

4. Heme Biosensing in Bacteria

4.1. HsmR

4.2. HatR and the Hat Efflux System in Clostridioides Difficile

4.3. PefR and Pef Efflux Transport

4.4. Heme Biosensors Regulating HrtBA Heme Efflux Transporter

4.4.1. HrtR (Heme-Regulated Transport Regulator) in Lactococcus lactis

4.4.2. FhtR (Faecalis heme Transport Regulator) in Enterococcus faecalis

4.4.3. HssS in S. aureus

5. Diagnostic Methods

5.1. Instrument-Based Methods for Heme Detection

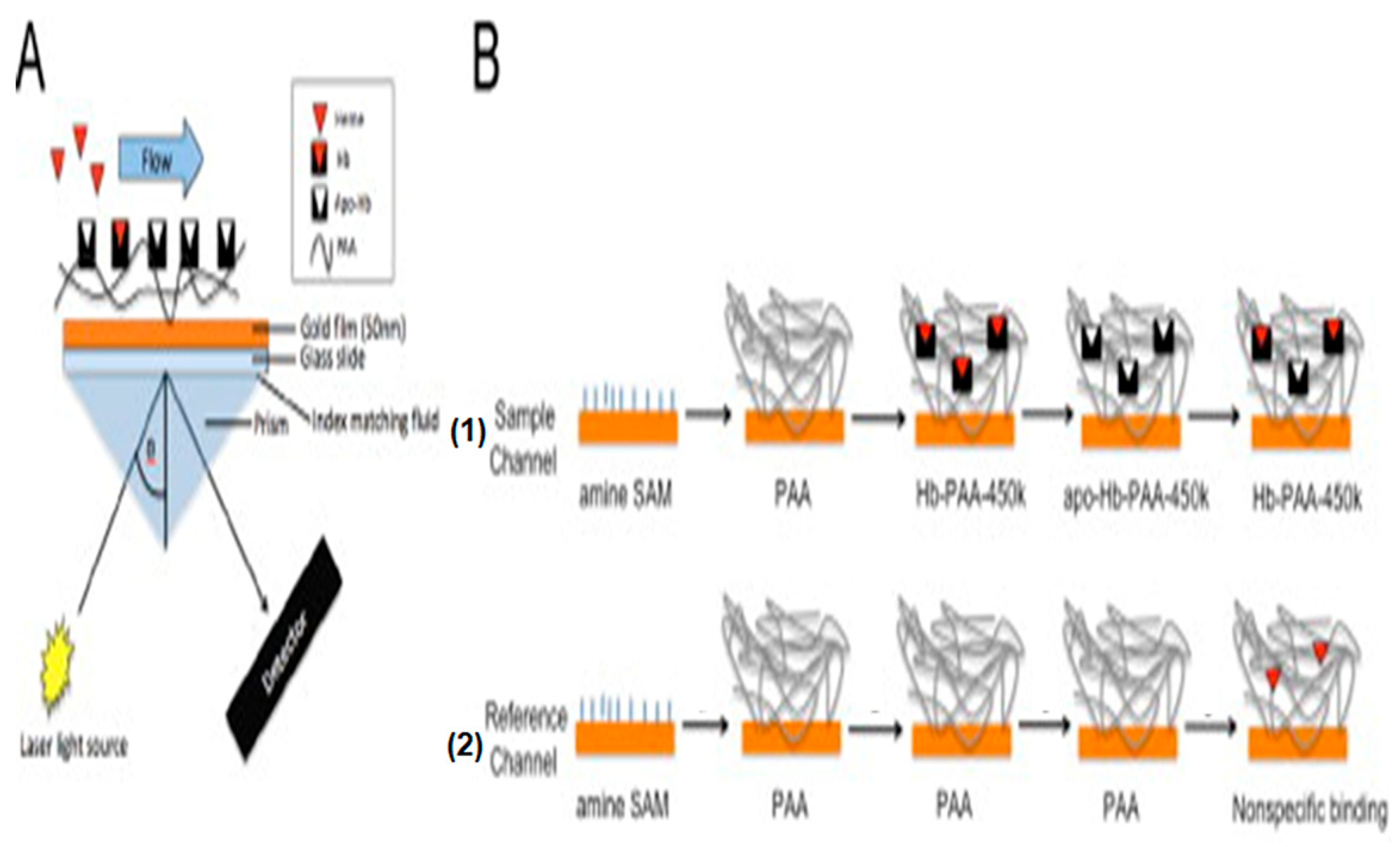

5.2. Optical Biosensors for Heme Detection

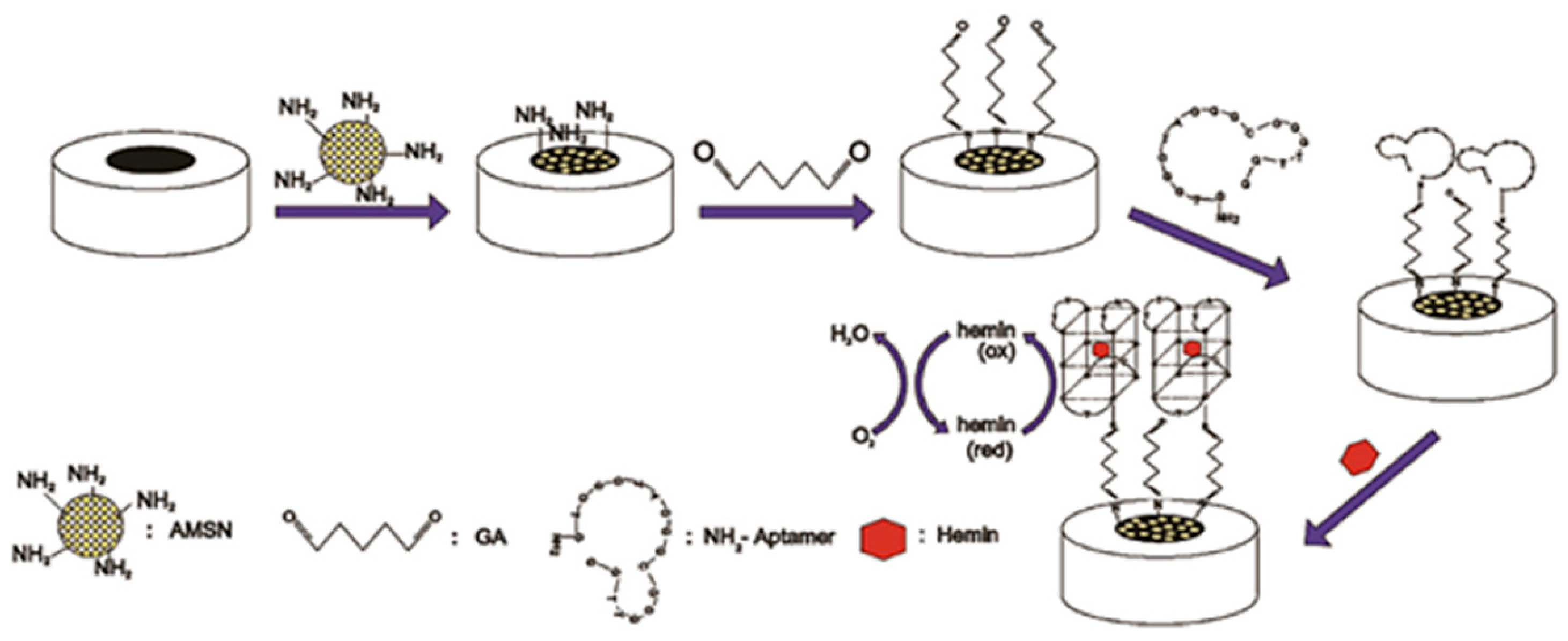

5.3. Electrochemical Biosensors for Heme Detection

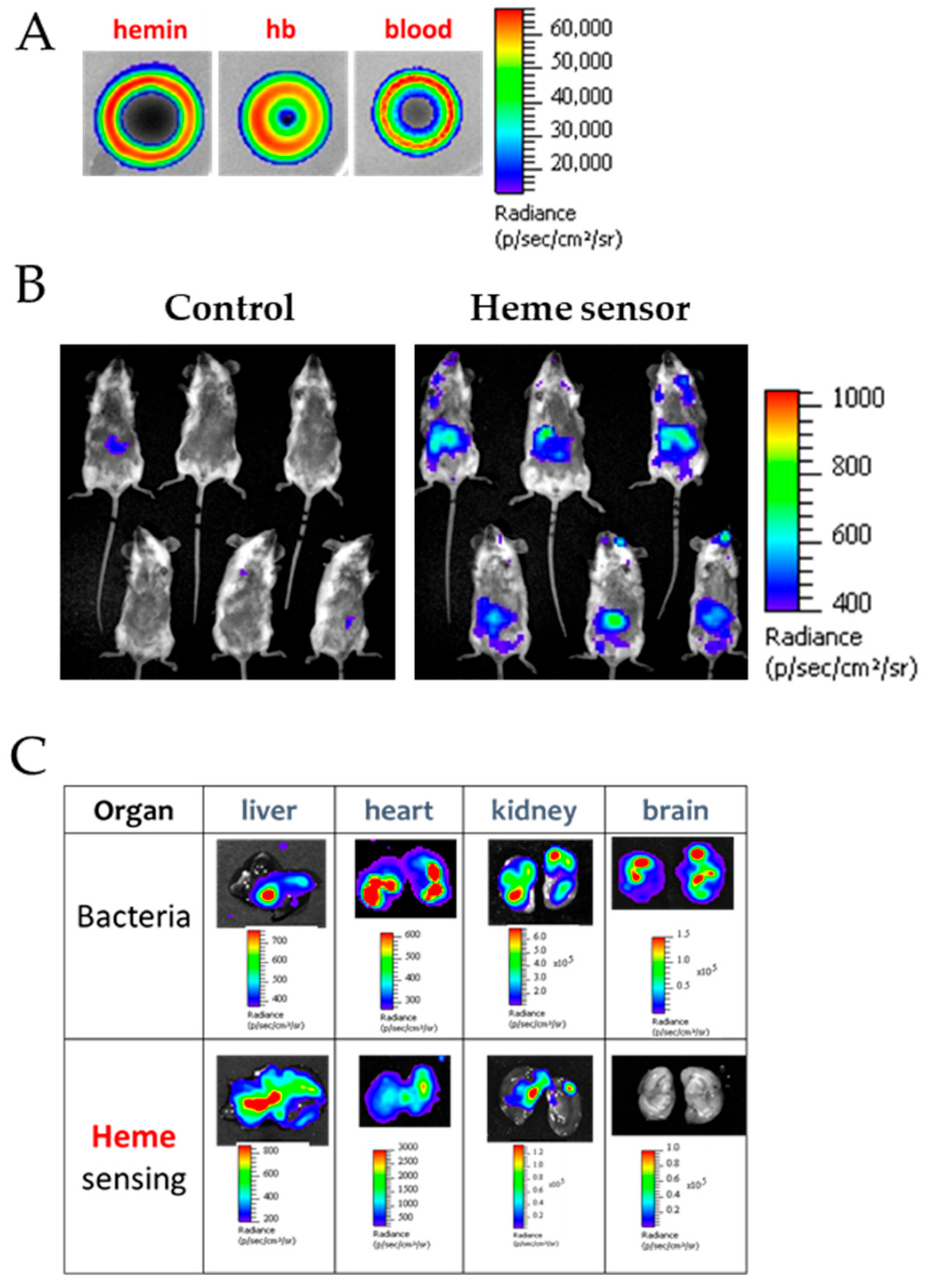

5.4. Cell-Based Biosensors for Heme Detection

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

| Methods | Molecule Quantified | Sensitivity | Matrix | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOBT a | Heme | Not determined | Feces | Colorimetric test based on heme peroxidase activity | [109] |

| iFOBT b | Hemoglobin | ≥10 μg/g | Feces | Quantitative test using hemoglobin antibodies fixed on latex beads | [110] |

| Urine test strips | Heme | 0.15–0.45 mg/L | Urine | Colorimetric test based on heme peroxidase activity | [111] |

| Fluorescent probe | Labile heme | Not determined | Cells and mouse | Artemisinin fluorophore | [105] |

| FRET c | Labile heme | 10 nM | Buffer | Fluorescence of Cytochrome b-GFP decreases upon binding heme | [112] |

| FRET c | Labile heme | Not determined | Buffer | Fluorescently labeled HO-1 was used as a recognition element | [87] |

| FRET c | Labile heme | Not determined | Buffer | Peptide derived from hemoproteins was used as a fluorescent probe | [113] |

| RP–HPLC d | Hemoprotein | Not determined | Urine, feces and blood | Detection of the porphyrin’s fluorescence at 600–630 nm | [114] |

| DWF–HPLC e | Porphyrins | 25 µM | Bood | [115] | |

| ELISA | Hemoproteins | >0.15 µM | Plasma (mouse) HeLa Cells | Single domain antibodies (sdAbs) coupled with ELISA | [101] |

| Pyridine hemochromogen test | Hemoproteins | 1 µM | Alkaline medium | Heme titration with pyridine used as a ligand | [116] |

| QuantiChrom assay Kit | Hemoproteins | 0.5 nM | Buffer | Colorimetric test | [74] |

| Cysteine probe | Labile heme | 0.5 µM | Plasma/human serum | Method distinguished between hemoglobin and free heme | [76] |

| Spectral deconvolution | Labile and bound heme | 2 µM | Plasma | Spectrum decomposition to distinguish between oxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin and free heme | [117,118] |

| TA Microscopy f | Hemoproteins | 9.2 µM | C. elegans and mammalian cell lines | Visualization of heme uptake and subcellular localization of heme | [119] |

| rRaman g | Hemoproteins | 5 µM | HEK293 Cells | Patch-clamp system | [82] |

| SERS h | Labile heme and its degradation products | 20–100 µM | Buffer | Molecule excitation at several wavelengths to compare obtained data to a standard curve | [83] |

| SPR i | Labile heme | 2 µM | Buffer | Ligand-receptor measurement: apo-hemoglobin immobilization to a matrix | [88] |

| MALDI TOF–MS j | Labile heme | 400 nM | Blood Agar medium | MS techniques are very specific but are more efficient for heme detection than heme quantification | [120] |

| ESI–MS k | Hemozoin (heme aggregate)/labile heme | 100 nM | P. falciparum extract | [121] | |

| HPLC-MS/MS l | Labile heme/porphyrins | 0.2 pM | Biological media and E. coli | HPLC optimization | [77] |

| RP–HPLC d/UV-visible | Labile heme/porphyrins | Not determined | Biological medium and tissues | Chromatograms comparison between the sample and the standard | [122] |

| UPLC m | Heme/hemozoin | Not determined | Spinal fluid, mouse tissue and P. falciparum extract | Simplest HPLC optimization | [123] [124] |

| IMBED n | Labile heme | 32.5 ppm | Biological sample | Bacterial biosensor coupled to an electronic system | [106] |

| HRP peroxidase activity method | Hemoproteins | 5.6 nM–0.2 µM | Urine | Method using capillary electrophoresis coupled with chemiluminescence | [125] |

| HRP activity method | Labile heme | 20 pM | Cellular medium | Measurement of the HRP allo-enzyme luminescence | [126] |

| 0.65 pM | Optimization | [75] | |||

| HemoQuant (HRP activity method) | Labile heme | >1 nM | Biological sample | Heme porphyrin excitation (λex = 400 nm et λem = 662 nm) | [127] |

| Electrochemical | Heme and Hb | 7.5 × 10−20 M heme 6.5 × 10−20 M Hb | Blood samples | G-quadruplex aptamer used as a sensing element | [96] |

| Electrochemical | Heme | 0.9 μg/mL | Blood sample | FhtR as a sensing element | [89] |

| Electrochemical | Hemin | 0.64 nM | Serum | G-quadruplex aptamer employed | [128] |

| Colorimetric | Hemin | 0.1 nM | Serum and environmental water | Non-G-quadruplex aptamer was optimized | [99] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Amino Acid |

| ALA | AminoLevulinic Acid |

| ALAS | AminoLevulinic Acid Synthase |

| CHY | α-Chymotrypsin |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DAMPs | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DHp | Dimerization histidine phosphotransfer |

| DNA | DeoxyRibonucleic Acid |

| DWF | Dual Wavelength Fluorescence |

| FhtR | Faecalis heme transport Regulator |

| FOBT | Fecal Occult Blood Test |

| FRET | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

| HAMP | Histidine kinase, Adenylate cyclase, Methyl-accepting protein and Phosphatase domain |

| HatR | Heme-activated transporter Regulator |

| hatRT | Heme-activated transporter Regulator/ Transporter operon |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| Hp | Haptoglobin |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HO-1 | Heme-Oxygenase 1 |

| HRP | HorseRadish Peroxidase |

| HrtBA | Heme-regulated transporter |

| HrtR | Heme-regulated transcriptional Regulator |

| HsmR | Heme-sensing membrane Regulator |

| hsmRA | Heme-sensing membrane protein system |

| HssS | Heme sensor system Sensor |

| HssR | Heme sensor system Regulator |

| Hx | Hemopexin |

| iFOBT | Immunological Fecal Occult Blood Test |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IMBED | Ingestible Micro-Bio-Electronic Device |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight |

| MarR | Multiple antibiotic resistance Regulator |

| MFS | Major Facilitator Superfamily |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| NFkB | Nuclear Factor-kappa B |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| O2 | Dioxygen |

| PAA | PolyAcrylic Acid |

| PCT | Porphyria Cutanea Tarda |

| Pef | Porphyrin efflux |

| PefAB | Porphyrin efflux transporter AB |

| PefCD | Porphyrin efflux transporter CD |

| PefR | Porphyrin efflux Regulator |

| PBG | Porphobilinogen |

| PPIX | Protoporphyrin IX |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCD | Sickle Cell Disease |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| SERS | Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering |

| TA Microscopy | Transient Absorption Microscopy |

| TetR | Tetracycline Repressor |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse Phase-High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| UPLC | Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography |

References

- Shimizu, T.; Lengalova, A.; Martínek, V.; Martínková, M. Heme: Emergent roles of heme in signal transduction, functional regulation and as catalytic centres. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 5624–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, T.L. Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3919–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Groves, J.T. Oxygen activation and radical transformations in heme proteins and metalloporphyrins. Chem. Rev. 2017, 118, 2491–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mense, S.M.; Zhang, L. Heme: A versatile signaling molecule controlling the activities of diverse regulators ranging from transcription factors to MAP kinases. Cell Res. 2006, 16, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T.B. Molecular mechanisms of iron and heme metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiftsoglou, A.S.; Tsamadou, A.I.; Papadopoulou, L.C. Heme as key regulator of major mammalian cellular functions: Molecular, cellular, and pharmacological aspects. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 111, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Wei, J.; Wu, H. Heme induces intestinal epithelial cell ferroptosis via mitochondrial dysfunction in transfusion-associated necrotizing enterocolitis. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; DelCimmuto, N.R.; Flack, K.D.; Stec, D.E.; Hinds, T.D., Jr. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants as immunomodulators in exercise: Implications for heme oxygenase and bilirubin. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, R.; Chakraborti, A.S. Major heme proteins hemoglobin and myoglobin with respect to their roles in oxidative stress–a brief review. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1543455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 157, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higdon, A.N.; Benavides, G.A.; Chacko, B.K.; Ouyang, X.; Johnson, M.S.; Landar, A.; Zhang, J.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Hemin causes mitochondrial dysfunction in endothelial cells through promoting lipid peroxidation: The protective role of autophagy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H1394–H1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeman, C.A.; Hammer, N.D.; Stauff, D.L.; Attia, A.S.; Anzaldi, L.L.; Dikalov, S.I.; Calcutt, M.W.; Skaar, E.P. Menaquinone biosynthesis potentiates haem toxicity in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 86, 1376–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubert, L.; Derré-Bobillot, A.; Gaudu, P.; Gruss, A.; Lechardeur, D. HrtBA and menaquinones control haem homeostasis in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 93, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryter, S.W. Significance of heme and heme degradation in the pathogenesis of acute lung and inflammatory disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, A.; Egoshi, R. Heme Trafficking and the Importance of Handling Nature’s Most Versatile Cofactor. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 11358–11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z. Microbial synthesis of heme b: Biosynthetic pathways, current strategies, detection, and future prospects. Molecules 2023, 28, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.R.; Rivera, M. Heme uptake and metabolism in bacteria. Met. Cell 2013, 12, 279–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kleingardner, J.G.; Bren, K.L. Biological significance and applications of heme c proteins and peptides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, S.; Palmer, D.J.; Schroeder, S.; Ferguson, S.J.; Warren, M.J. Recent advances in the biosynthesis of modified tetrapyrroles: The discovery of an alternative pathway for the formation of heme and heme d 1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2837–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layer, G. Heme biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, N.A.; Gallio, A.E.; Mandal, S.K.; Laskowski, R.A.; Raven, E.L. In silico prediction of heme binding in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewitz, H.H.; Hagelueken, G.; Imhof, D. Structural and functional diversity of transient heme binding to bacterial proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Marles-Wright, J.; Sharp, K.H.; Paoli, M. Diversity and conservation of interactions for binding heme in b-type heme proteins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M.; Villamil Franco, C.; Ramodiharilafy, R.; Liebl, U.; Vos, M.H. Interaction of the full-length heme-based CO sensor protein RcoM-2 with ligands. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 4028–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldo, S.; Castiglione, N.; Giardina, G.; Caruso, M.; Arcovito, A.; Longa, S.D.; d’Angelo, P.; Cutruzzola, F. Unusual heme binding properties of the dissimilative nitrate respiration regulator, a bacterial nitric oxide sensor. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhana, A.; Saini, V.; Kumar, A.; Lancaster, J.R., Jr.; Steyn, A.J. Environmental heme-based sensor proteins: Implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 1232–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Zarandi, M.A.; Zhou, X.; Jayawickramarajah, J. Synthesis and applications of porphyrin-biomacromolecule conjugates. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 764137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.P.; Meissner, A.; Boknik, P.; Hartlage, M.G.; Möllhoff, T.; Van Aken, H.; Rolf, N. Hemin, inducer of heme-oxygenase 1, improves functional recovery from myocardial stunning in conscious dogs. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2001, 15, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzi, P.; Bocedi, A.; Visca, P.; Altruda, F.; Tolosano, E.; Beringhelli, T.; Fasano, M. Hemoglobin and heme scavenging. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belot, A.; Puy, H.; Hamza, I.; Bonkovsky, H.L. Update on heme biosynthesis, tissue-specific regulation, heme transport, relation to iron metabolism and cellular energy. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 2235–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellelli, A.; Brunori, M. Hemoglobin allostery: Variations on the theme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shimizu, T.; Huang, D.; Yan, F.; Stranava, M.; Bartosova, M.; Fojtíková, V.; Martínková, M. Gaseous O2, NO, and CO in signal transduction: Structure and function relationships of heme-based gas sensors and heme-redox sensors. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6491–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallelian, F.; Buehler, P.W.; Schaer, D.J. Hemolysis, free hemoglobin toxicity, and scavenger protein therapeutics. Blood 2022, 140, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandow, A.; Liem, R. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of sickle cell disease. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orf, K.; Cunnington, A.J. Infection-related hemolysis and susceptibility to Gram-negative bacterial co-infection. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáll, T.; Balla, G.; Balla, J. Heme, heme oxygenase, and endoplasmic reticulum stress—A new insight into the pathophysiology of vascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J.; Shiva, S.; Gladwin, M.T. Sources of vascular nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species and their regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 311–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, E.; Romana, M.; Connes, P. The Red Blood Cell-Inflammation Vicious Circle in Sickle Cell Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, M. Biophysical chemistry behind sickle cell anemia and the mechanism of voxelotor action. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Alakwe-Ojimba, C.E.; Elendu, T.C.; Elendu, R.C.; Ayabazu, C.P.; Aina, T.O.; Aborisade, O.; Adenikinju, J.S. Understanding sickle cell disease: Causes, symptoms, and treatment options. Medicine 2023, 102, e35237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Villalobos, M.; Blanquer, M.; Moraleda, J.M.; Salido, E.J.; Perez-Oliva, A.B. New insights into pathophysiology of β-thalassemia. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 880752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivella, S. β-thalassemias: Paradigmatic diseases for scientific discoveries and development of innovative therapies. Haematologica 2015, 100, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, R.K.; Dickey, A.K. Porphyria cutanea tarda: A unique iron-related disorder. Hematology 2024, 2024, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K. Porphyria cutanea tarda: Recent update. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 128, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerchberger, V.E.; Ware, L.B. The role of circulating cell-free hemoglobin in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2020, 40, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iba, T.; Umemura, Y.; Watanabe, E.; Wada, T.; Hayashida, K.; Kushimoto, S. Japanese Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline Working Group for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Diagnosis of sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation and coagulopathy. Acute Med. Surg. 2019, 6, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakdi, S.; Bayley, H.; Valeva, A.; Walev, I.; Walker, B.; Weller, U.; Kehoe, M.; Palmer, M. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin, streptolysin-O, and Escherichia coli hemolysin: Prototypes of pore-forming bacterial cytolysins. Arch. Microbiol. 1996, 165, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.P.; Green, B.J.; Beezhold, D.H. Fungal hemolysins. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.J. Anaemia and malaria. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, B.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X. Global, regional, and national trends in colorectal cancer burden from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2040. Front. Oncol. 2025, 14, 1466159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Rabu, R.; Abidi, H.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Acuna, J.M.; Adhikari, S.; Advani, S.M.; Afzal, M.S.; Meybodi, M.A.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, K.P.; Skaar, E.P. A battle for iron: Host sequestration and Staphylococcus aureus acquisition. Microbes Infect. 2012, 14, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pishchany, G.; Skaar, E.P. Taste for blood: Hemoglobin as a nutrient source for pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruss, A.; Borezée-Durant, E.; Lechardeur, D. Environmental heme utilization by heme-auxotrophic bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2012, 61, 69–124. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson, D.N.; Lemos, J.A. Heme utilization by the enterococci. FEMS Microbes 2024, 5, xtae019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, N.; Buisson, C.; Gohar, M.; Vidic, J.; Bierne, H.; Kallassy, M.; Lereclus, D.; Nielsen-LeRoux, C. IlsA, a unique surface protein of Bacillus cereus required for iron acquisition from heme, hemoglobin and ferritin. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léguillier, V.; Pinamonti, D.; Chang, C.-M.; Gunjan; Mukherjee, R.; Himanshu; Cossetini, A.; Manzano, M.; Anba-Mondoloni, J.; Malet-Villemagne, J.; et al. A review and meta-analysis of Staphylococcus aureus prevalence in foods. Microbe 2024, 4, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Skaar, E.P. Heme in Bacterial Pathogenesis and as an Antimicrobial Target. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 11120–11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, E.; Hejmadi, V.; Ryter, S.; Pourzand, C.; Tyrrell, R.M. Heme oxygenase activity causes transient hypersensitivity to oxidative ultraviolet A radiation that depends on release of iron from heme. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoubrey, W.K., Jr.; Huang, T.; Maines, M.D. Heme oxygenase-2 is a hemoprotein and binds heme through heme regulatory motifs that are not involved in heme catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12568–12574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryter, S.W.; Tyrrell, R.M. The heme synthesis and degradation pathways: Role in oxidant sensitivity: Heme oxygenase has both pro-and antioxidant properties. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryter, S.W.; Kvam, E.; Tyrrell, R.M. Heme oxygenase activity current methods and applications. Stress Response Methods Protoc. 2000, 99, 369–391. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, A.; Lechardeur, D.; Derre-Bobillot, A.; Couve, E.; Gaudu, P.; Gruss, A. Two coregulated efflux transporters modulate intracellular heme and protoporphyrin IX availability in Streptococcus agalactiae. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechardeur, D.; Cesselin, B.; Liebl, U.; Vos, M.H.; Fernandez, A.; Brun, C.; Gruss, A.; Gaudu, P. Discovery of intracellular heme-binding protein HrtR, which controls heme efflux by the conserved HrtB-HrtA transporter in Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 4752–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saillant, V.; Lipuma, D.; Ostyn, E.; Joubert, L.; Boussac, A.; Guerin, H.; Brandelet, G.; Arnoux, P.; Lechardeur, D. A novel Enterococcus faecalis heme transport regulator (FhtR) senses host heme to control its intracellular homeostasis. MBio 2021, 12, e03392–e03420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saillant, V.; Morey, L.; Lipuma, D.; Boëton, P.; Siponen, M.; Arnoux, P.; Lechardeur, D. HssS activation by membrane heme defines a paradigm for two-component system signaling in Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 2024, 15, e00230–00224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippel, R.J.; Wexler, A.G.; Miller, J.M.; Beavers, W.N.; Weiss, A.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Edmonds, K.A.; Giedroc, D.P.; Skaar, E.P. Clostridioides difficile senses and hijacks host heme for incorporation into an oxidative stress defense system. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 411–421.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippel, R.J.; Zackular, J.P.; Moore, J.L.; Celis, A.I.; Weiss, A.; Washington, M.K.; DuBois, J.L.; Caprioli, R.M.; Skaar, E.P. Heme sensing and detoxification by HatRT contributes to pathogenesis during Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachla, A.J.; Ouattara, M.; Romero, E.; Agniswamy, J.; Weber, I.T.; Gadda, G.; Eichenbaum, Z. In vitro heme biotransformation by the HupZ enzyme from Group A streptococcus. Biometals 2016, 29, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibb, L.A.; Schmitt, M.P. The ABC transporter HrtAB confers resistance to hemin toxicity and is regulated in a hemin-dependent manner by the ChrAS two-component system in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 4606–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauff, D.L.; Skaar, E.P. The heme sensor system of Staphylococcus aureus. Contrib. Microbiol. 2009, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sawai, H.; Yamanaka, M.; Sugimoto, H.; Shiro, Y.; Aono, S. Structural basis for the transcriptional regulation of heme homeostasis in Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 30755–30768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flink, E.B.; Watson, C.J. A method for the quantitative determination of hemoglobin and related heme pigments in feces, urine, and blood plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 1942, 146, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, N.T.; Uyen, D.T.; Sasai, M.; Harada, S.; Kamei, K. An improved colorimetric method for quantitation of heme using tetramethylbenzidine as substrate. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 344, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamna, H.; Brahmbhatt, M.; Atamna, W.; Shanower, G.A.; Dhahbi, J.M. ApoHRP-based assay to measure intracellular regulatory heme. Metallomics 2015, 7, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.; Bozinovic, N.; Lecerf, M.; Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Dimitrov, J.D. Use of cysteine as a spectroscopic probe for determination of heme-scavenging capacity of serum proteins and whole human serum. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 172, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyrestam, J.; Östman, C. Determination of heme in microorganisms using HPLC-MS/MS and cobalt (III) protoporphyrin IX inhibition of heme acquisition in Escherichia coli. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 6999–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, A.; Szczesny-Malysiak, E.; Dybas, J. Tracking heme biology with resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2025, 1873, 141065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, U.; Rösch, P.; Popp, J. Raman spectroscopy towards clinical application: Drug monitoring and pathogen identification. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajda, A.; Dybas, J.; Kachamakova-Trojanowska, N.; Pacia, M.Z.; Wilkosz, N.; Bułat, K.; Chwiej, J.; Marzec, K.M. Raman imaging unveils heme uptake in endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybas, J.; Grosicki, M.; Baranska, M.; Marzec, K.M. Raman imaging of heme metabolism in situ in macrophages and Kupffer cells. Analyst 2018, 143, 3489–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugebauer, U.; Heinemann, S.H.; Schmitt, M.; Popp, J. Combination of patch clamp and Raman spectroscopy for single-cell analysis. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugebauer, U.; März, A.; Henkel, T.; Schmitt, M.; Popp, J. Spectroscopic detection and quantification of heme and heme degradation products. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 404, 2819–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbinot, S.; Srivastav, A.M.; Vidic, J.; Abdulhalim, I.; Manzano, M. Plasmonic biosensors for food control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidic, J.; Manzano, M.; Chang, C.-M.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Advanced biosensors for detection of pathogens related to livestock and poultry. Vet. Res. 2017, 48, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, V.; Scaramozzino, N.; Vidic, J.; Buhot, A.; Mathey, R.; Chaix, C.; Hou, Y. Recent advances on peptide-based biosensors and electronic noses for foodborne pathogen detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, S.; Yoshihara, S.; Bando, H.; Yamasaki, K.; Higashimoto, Y.; Noguchi, M.; Sueda, S.; Komatsu, H.; Sakamoto, H. Development of a heme sensor using fluorescently labeled heme oxygenase-1. Anal. Biochem. 2013, 433, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, V.A.; Thilakarathne, V.; Kasi, R.M.; Kumar, C.V. Novel surface plasmon resonance sensor for the detection of heme at biological levels via highly selective recognition by apo-hemoglobin. Talanta 2012, 99, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Li, Z.; Kong, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.-n.; Zhou, E.; Fan, Y.; Xu, D.; Gu, T. Label-free detection of heme in electroactive microbes using a probe-typed optical fiber SPR sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 288, 117797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travascio, P.; Li, Y.; Sen, D. DNA-enhanced peroxidase activity of a DNA aptamer-hemin complex. Chem. Biol. 1998, 5, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosman, J.; Juskowiak, B. Peroxidase-mimicking DNAzymes for biosensing applications: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 707, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Takahira, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Di, Y.; Shibata, T.; Tai, H.; Suzuki, A.; Neya, S. Characterization of heme-DNA complexes composed of some chemically modified hemes and parallel G-quadruplex DNAs. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 7168–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léguillier, V.; Heddi, B.; Vidic, J. Recent advances in aptamer-based biosensors for bacterial detection. Biosensors 2024, 14, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidic, J.; Manzano, M. Electrochemical biosensors for rapid pathogen detection. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 29, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Nakayama, Y.; Katahira, Y.; Tai, H.; Moritaka, Y.; Nakano, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Characterization of the interaction between heme and a parallel G-quadruplex DNA formed from d (TTGAGG). Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekari, Z.; Zare, H.R.; Falahati, A. An ultrasensitive aptasensor for hemin and hemoglobin based on signal amplification via electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 518, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukakoshi, K.; Yamagishi, Y.; Kanazashi, M.; Nakama, K.; Oshikawa, D.; Savory, N.; Matsugami, A.; Hayashi, F.; Lee, J.; Saito, T.; et al. G-quadruplex-forming aptamer enhances the peroxidase activity of myoglobin against luminol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6069–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzotto, F.; Khalife, M.; Hou, Y.; Chaix, C.; Lagarde, F.; Scaramozzino, N.; Vidic, J. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors for food control. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Wu, T. Application of Non-G-Quadruplex Hemin Aptamers to Hemin Detection and Heme Oxygenase 1 Activity Evaluation via Spatial Conformational Constraint. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 13542–13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajunwa, O.M.; Minero, G.A.S.; Jensen, S.D.; Meyer, R.L. Hemin-binding DNA structures on the surface of bacteria promote extracellular electron transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, Z.; Carlos, A.R.; Yuan, X.; Aires-da-Silva, F.; Stocker, R.; Maghzal, G.J.; Leal, S.S.; Gomes, C.M.; Todorovic, S.; Iranzo, O.; et al. Characterization of plasma labile heme in hemolytic conditions. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 3278–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abshire, J.R.; Rowlands, C.J.; Ganesan, S.M.; So, P.T.; Niles, J.C. Quantification of labile heme in live malaria parasites using a genetically encoded biosensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2068–E2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combrinck, J.M.; Mabotha, T.E.; Ncokazi, K.K.; Ambele, M.A.; Taylor, D.; Smith, P.J.; Hoppe, H.C.; Egan, T.J. Insights into the role of heme in the mechanism of action of antimalarials. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.; Yuan, X.; Schmidt, P.J.; Bresciani, E.; Samuel, T.K.; Campagna, D.; Hall, C.; Bishop, K.; Calicchio, M.L.; Lapierre, A.; et al. HRG1 is essential for heme transport from the phagolysosome of macrophages during erythrophagocytosis. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, H.-W.; Chen, L.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Teng, L.; Huan, S.-Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, X.-B.; Tan, W. Learning from artemisinin: Bioinspired design of a reaction-based fluorescent probe for the selective sensing of labile heme in complex biosystems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimee, M.; Nadeau, P.; Hayward, A.; Carim, S.; Flanagan, S.; Jerger, L.; Collins, J.; McDonnell, S.; Swartwout, R.; Citorik, R.J.; et al. An ingestible bacterial-electronic system to monitor gastrointestinal health. Science 2018, 360, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, P.A.; Monk, I.R.; Corr, S.C.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G. Novel luciferase reporter system for in vitro and organ-specific monitoring of differential gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2876–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, L.; Dagieu, J.B.; Fernandez, A.; Derre-Bobillot, A.; Borezee-Durant, E.; Fleurot, I.; Gruss, A.; Lechardeur, D. Visualization of the role of host heme on the virulence of the heme auxotroph Streptococcus agalactiae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertsen, V.A.; McHugh, R.; Schuman, L.; Williams, S.E. The earlier detection of colorectal cancers. A preliminary report of the results of the occult blood study. Cancer 1980, 45, 2899–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott, C.; Carroll, M.R.; John, C.; O’Driscoll, S.; Benton, S.C. Analytical evaluation of four faecal immunochemistry tests for haemoglobin. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2021, 59, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, H.M.; Free, A.H.; Giordano, A. Studies with a simple test for the detection of occult blood in urine. J. Urol. 1956, 75, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, J.A.; Czapinska, H.; Piasecka, A.; Edwards, W.R.; Barker, P.; Gajda, M.J.; Bochtler, M.; Jones, D.D. Structural basis for efficient chromophore communication and energy transfer in a constructed didomain protein scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13632–13640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, L.D.; Pascu, S.I.; Tyrrell, R.M.; Eggleston, I.M. Development of a peptide-based fluorescent probe for biological heme monitoring. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.S.; Simmonds, P.L. HPLC methods for analysis of porphyrins in biological media. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2001, 7, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, G.; Gruber, C.; Vogeser, M.; Stepp, H.; Dittmar, S.; Sroka, R.; Brittenham, G.M. Dual-wavelength excitation for fluorescence-based quantification of zinc protoporphyrin IX and protoporphyrin IX in whole blood. Wiley Online Libr. 2014, 7, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, W.; Elliott, W. The formation of pyridine haemochromogen. Biochem. J. 1965, 97, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.; Oh, J.-Y.; Lebensburger, J.D.; Patel, R.P. Simultaneous determination of free heme and free hemoglobin in biological samples by spectral deconvolution. Blood 2014, 124, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-Y.; Hamm, J.; Xu, X.; Genschmer, K.; Zhong, M.; Lebensburger, J.; Marques, M.B.; Kerby, J.D.; Pittet, J.-F.; Gaggar, A.; et al. Absorbance and redox based approaches for measuring free heme and free hemoglobin in biological matrices. Redox Biol. 2016, 9, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.J.; Yuan, X.; Li, J.; Dong, P.; Hamza, I.; Cheng, J.-X. Label-free imaging of heme dynamics in living organisms by transient absorption microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3395–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteaker, J.R.; Fenselau, C.C.; Fetterolf, D.; Steele, D.; Wilson, D. Quantitative determination of heme for forensic characterization of Bacillus spores using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 2836–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.E.; Roepe, P.D. Quantification of free ferriprotoporphyrin IX heme and hemozoin for artemisinin sensitive versus delayed clearance phenotype Plasmodium falciparum malarial parasites. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 6927–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Alayash, A.I. Determination of extinction coefficients of human hemoglobin in various redox states. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 521, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, R.H.; Yuan, X.; Rietzschel, N.; Zhang, J.; Jackson, L.; Nishibori, E.; Ribeiro, A.; Simmons, W.; Jagadeesh, J.; Sugimoto, H.; et al. Hemozoin produced by mammals confers heme tolerance. eLife 2019, 8, e49503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, P.; Durnford, A.J.; Okemefuna, A.I.; Dunbar, J.; Nicoll, J.A.; Galea, J.; Boche, D.; Bulters, D.O.; Galea, I. Heme–hemopexin scavenging is active in the brain and associates with outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2016, 47, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sun, X.; Lin, Y.; Chen, G. Highly sensitive analysis of four hemeproteins by dynamically-coated capillary electrophoresis with chemiluminescence detector using an off-column coaxial flow interface. Analyst 2013, 138, 2269–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, T.; Takahashi, S. Chemiluminescent-based method for heme determination by reconstitution with horseradish peroxidase apo-enzyme. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 355, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.; Dahl, J.; Ellefson, M.; Ahlquist, D. The “HemoQuant” test: A specific and quantitative determination of heme (hemoglobin) in feces and other materials. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, B.; Yang, X. A carboxylated graphene and aptamer nanocomposite-based aptasensor for sensitive and specific detection of hemin. Talanta 2015, 132, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dobill, K.; Lechardeur, D.; Vidic, J. Biosensors for Detection of Labile Heme in Biological Samples. Biosensors 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010004

Dobill K, Lechardeur D, Vidic J. Biosensors for Detection of Labile Heme in Biological Samples. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobill, Krysta, Delphine Lechardeur, and Jasmina Vidic. 2026. "Biosensors for Detection of Labile Heme in Biological Samples" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010004

APA StyleDobill, K., Lechardeur, D., & Vidic, J. (2026). Biosensors for Detection of Labile Heme in Biological Samples. Biosensors, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010004