Abstract

This study presents the synthesis and comprehensive characterization of tin dioxide nanoparticles (SnO2NPs). SnO2NPs were obtained using a conventional wet-chemistry route and an environmentally friendly green-chemistry approach employing plant extracts from rooibos leaves (Aspalathus linearis), pomegranate seeds (Punica granatum), and kiwifruit peels (family Actinidiaceae). The thermal stability and decomposition profiles were analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), while their structural and physicochemical properties were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering (DLS), Raman spectroscopy, and attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the nanoscale morphology and uniformity of the obtained particles. The photocatalytic activity of SnO2NPs was evaluated via the degradation of methyl orange (MeO) under UV irradiation, revealing that nanoparticles synthesized using rooibos extract exhibited the highest efficiency (68% degradation within 180 min). Furthermore, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) spectroscopy was employed to study the adsorption behavior of L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) on the SnO2NP surface. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the use of pure SnO2 nanoparticles as SERS substrates for biologically active, low-symmetry molecules. The calculated enhancement factor (EF) reached up to two orders of magnitude (102), comparable to other transition metal-based nanostructures. These findings highlight the potential of SnO2NPs as multifunctional materials for biomedical and sensing applications, bridging nanotechnology and regenerative medicine.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, tin dioxide nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) have attracted considerable attention due to their unique physical properties, including high chemical stability and sensitivity, favorable mechanical properties, optical characteristics, and atmosphere-dependent electrical conductivity (under both oxidizing and reducing conditions) [1,2,3,4]. Their large surface-to-volume ratio enhances their chemical and biological activity, making them promising candidates for use as radical scavengers [5,6,7]. Furthermore, they are inexpensive and readily available. Consequently, SnO2NPs are widely used in gas sensors [8], supercapacitors [9], solar cells [10], rechargeable lithium-ion batteries [11] and other functional materials. More recently, their potential biomedical applications have been recognized. SnO2NPs exhibit notable antioxidants and antibacterial activities. For instance, they have been shown to inhibit the growth of both Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis) and Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli) [12,13,14]. This antibacterial activity is attributed to their ability to penetrate bacterial membranes and inhibit cell proliferation, either by disrupting the cell wall via the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the decomposition or through electrostatic interactions with the cell membrane [15,16]. In addition, several studies have demonstrated the potential of SnO2NPs in bone regeneration and repair [16,17,18,19]. The increasing clinical use of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering raises concerns regarding osseointegration and postoperative bacterial infections. Commonly used polymers, such as poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), as well as ceramics (hydroxyapatite, HA) and metals (e.g., titanium), may be colonized by bacteria and are generally bioinert. In this context, SnO2NPs have been shown to modulate cellular behavior through electronic and chemical signaling [17,20,21,22]. Furthermore, SnO2NPs have demonstrated therapeutic potential against various cancer cell lines, including ovarian cancer, MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, U-2 OS human osteosarcoma cells, leukemia K562 cells, and cervical carcinoma cells [23,24,25,26,27,28].

Bulk SnO2 is a transparent n-type semiconductor (approximately 97% transparent across the visible spectrum) with a band gap of 3.6 eV (344 nm) at 300 K [29]. Upon heating, SnO2 undergoes oxidation, resulting in the formation of tin cations with unsaturated coordination (four instead of six). This transformation leads to the formation of a non-stoichiometric oxide. Thermal excitation of this oxide can produce paramagnetic species, such as VO+ (F-center) and Sn3+ [30]. In the absence of degeneracy, enhanced absorption at longer wavelengths is observed, allowing for the detection of surface species [31]. However, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy encounters challenges associated with free carriers (intraband transitions) and electron/hole donor transitions involving localized states. The concentration of these species depends on atmospheric conditions and temperature [30].

Various physical and chemical methods have been developed for the synthesis of SnO2NPs, including rapid tin oxidation [32], etching [33], hydrothermal synthesis, thermal decomposition [34], chemical vapor deposition [35], and sol–gel processing [36]. Many of these methods require surfactants or combustion aids, which may pose health risks and contribute to environmental contamination. Additionally, these methods often involve complex procedures or costly instrumentation. Therefore, there is a growing need to develop simple, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly synthesis routes capable of producing highly crystalline nanostructures with tunable properties and narrow particle size distributions. Plant-mediated green synthesis has emerged as a sustainable alternative that meets these requirements. Furthermore, such approaches align with the European Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC) and the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), which oblige EU member states to reduce biodegradable waste destined for landfills, including peels and seeds [37,38]. Industrial reuse of this waste can enable the production of natural additives, such as metal oxides, through environmentally benign routes.

In this study, SnO2 NPs were synthesized using both conventional wet chemical and green chemistry methods employing plant extracts derived from three sources: rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) leaves, pomegranate (Punica granatum) seeds, and kiwifruit (Actinidiaceae family) peels (Figure 1). These plants contain phytochemicals such as phenolic compounds, flavonoids, ellagitannins, and proanthocyanidins, which act as reducing and stabilizing agents during nanoparticle formation. The synthesized nanoparticles were characterized using various spectroscopic and microscopic techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), UV–Vis spectroscopy, and transmission electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM-EDS).

Figure 1.

Plants readily available and used as reducing agents for the green synthesis of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs).

The photocatalytic performance of the SnO2NPs was assessed through the degradation of methyl orange (MO) at room temperature, and their recyclability was evaluated over multiple cycles. Additionally, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) spectroscopy was employed to investigate adsorption phenomena on the nanoparticle surfaces. The results were compared to identify the most efficient synthesis method for SnO2NPs, intended for use as additives in 3D-printed bone scaffolds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Plant extracts were obtained from rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) leaves, pomegranate (Punica granatum) seeds, and kiwifruit (Actinidiaceae family) peels (Figure 1). Tin(II) chloride dihydrate (SnCl2·2H2O), tin(IV) chloride pentahydrate (SnCl4·5H2O), concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), ammonia solution (NH4OH), methyl orange (MeO), and L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) were purchased from Merck (Poznań, Poland). All reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis SnO2 Nanoparticles

- Wet chemical synthesis

An ultrasonic cleaner was used to dissolve 25 g of SnCl2·2H2O in 20 mL of concentrated HCl and 10 mL of distilled water [39]. Ammonia solution (1:1, v/v) was then added until the pH reached 1.0, and the mixture was stirred for 10 min. Subsequently, a 2 M ammonia solution was added to adjust the pH to 2.5. The resulting precipitate was filtered, washed with distilled water, and dried at 120 °C for 12 h, followed by an additional 1 h at 180 °C.

- Green synthesis

A green chemistry approach was employed using extracts from rooibos leaves, pomegranate seeds, and kiwifruit peels.

Kiwifruit extract: Peels were mixed with distilled water at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v) and heated to 60 °C for 60 min. The solution was then cooled and filtered. A 5 mL portion of the extract was added to 10 mM aqueous SnCl4 solution and stirred for 1.5 h at 100 °C. The obtained precipitate was filtered, washed with distilled water, and air-dried.

Pomegranate seed extract: 1 mL of fresh juice from crushed seeds was diluted to 50 mL with deionized water and filtered. Five milliliters of the filtrate were added to 20 mL of a 0.1 M aqueous SnCl4 solution. The mixture was stirred for 5 min at room temperature. The resulting precipitate was centrifuged, washed with distilled water, and dried at room temperature.

Rooibos extract: 8 g of powdered rooibos leaves were added to 450 mL of distilled water and left to stand for 48 h. The mixture was then filtered, and 4 g of SnCl4·5H2O was dissolved in 400 mL of the filtrate. After 10 min, the precipitate was filtered, washed with distilled water, and air-dried.

2.3. Spectroscopic Characterization of SnO2 Nanoparticles

- Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

TGA was performed using a Mettler Toledo TGA/SDTA 851e instrument (Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland). Measurements were carried out under an air flow of 80 cm3 min−1 within a temperature range of 25–1000 °C and at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

- Calcination

Calcination was conducted in a muffle furnace under controlled airflow. Based on TGA results, SnO2NPs synthesized from rooibos, pomegranate, and kiwifruit extracts were calcined at 700 °C, 600 °C, and 500 °C, respectively. Samples were heated at a rate of 5 °C min−1, maintained at the target temperature for 6 h, and then cooled to room temperature.

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and EDS

TEM images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) data were obtained using a Tecnai G2 transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operating at 200 kV. The microscope was equipped with an EDX microanalyzer and a high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector. Observations were carried out in bright-field (BF), selected-area electron diffraction (SAED), high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) modes.

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Particle size distribution was determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The analyzer was equipped with an avalanche photodiode detector with >50% quantum efficiency at 633 nm and operated at 25 °C. A 0.1 wt% suspension of SnO2 NPs in distilled water was sonicated for 15 min at 20 W (continuous mode) using a Branson SFX250 ultrasonic homogenizer before measurement.

- UV–Vis spectroscopy

UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded using a Lambda 25 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Inc., Shelton, CT, USA).

- X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Powder XRD patterns were obtained using an Aeris diffractometer (PANalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands) with Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Measurements were performed over an angular range of 10–80° (2θ).

- Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were collected using an InVia Raman spectrometer (Renishaw, Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, UK) equipped with a Leica microscope (50× objective) and an air-cooled CCD detector. A diode laser emitting at 785 nm (10 mW output power) was used as the excitation source. Four accumulations were collected for each spectrum with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1.

- ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a diamond ATR accessory. Measurements were performed at 4 cm−1 resolution with 500 scans per spectrum.

2.4. Photocatalytic Activity of SnO2 Nanoparticles

Photocatalytic activity was evaluated in a quartz cell containing an aqueous mixture of SnO2NPs, MeO, and distilled water in a molar ratio of approximately 1:4.5:8. The suspension (1 mL) was kept in the dark for 30 min to reach adsorption–desorption equilibrium before irradiation. Then, suspension was irradiated with 365 nm UV light (UV lamp model LP2536UV, Kamush UV Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China, intensity 0.8 mW/cm2) for up to 180 min in 30 min intervals. Absorbance changes were monitored using a Lambda 25 UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

2.5. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Measurements

L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) was dissolved in deionized water (conductivity = 0.08 μS cm−1) to prepare a 10−3 mol L−1 solution. The SnO2NP suspension was mixed with the L-Phe solution and incubated for 24 h prior to measurement.

SERS spectra (spectral resolution = 4 cm−1) were recorded using an InVia Raman spectrometer (Renishaw) equipped with a Leica microscope (50× objective) and an air-cooled CCD detector. Excitation was provided by a 785 nm diode laser (10 mW output power, 40 s exposure per accumulation). Spectra were collected at three different locations on three separate drops of the SnO2 NP/L-Phe mixture (nine spectra in total). No spectral changes indicative of sample degradation were observed.

2.6. Spectral Analysis

Spectral data were analyzed using SpectraGryph software (version 1.2.15, Dr. Friedrich Menges, Oberstdorf, Germany, 2016–2020).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spectroscopic Characterization

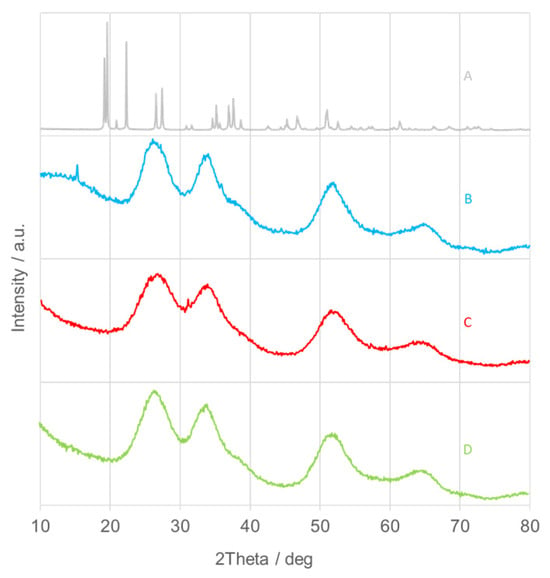

Crystalline materials, characterized by a regular and periodic atomic arrangement, exhibit sharp and well-defined diffraction peaks in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. In contrast, amorphous or poorly crystalline substances display broad and diffuse halos instead of sharp reflections. In this study, the XRD patterns of the as-synthesized SnO2NPs (Figure 2, traces B–D) indicate a low degree of crystallinity or an amorphous nature. The reduced crystallinity of the samples synthesized using plant extracts may result from local temperature increases during the exothermic hydrolysis of tin salts under alkaline conditions [40]. Trace A in Figure 2 corresponds to tin(II) hydroxychloride (Sn(OH)Cl) [39]. Accordingly, all samples were subjected to calcination for further structural investigation.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of as-prepared SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via (A) the wet-chemistry method and the green synthesis method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

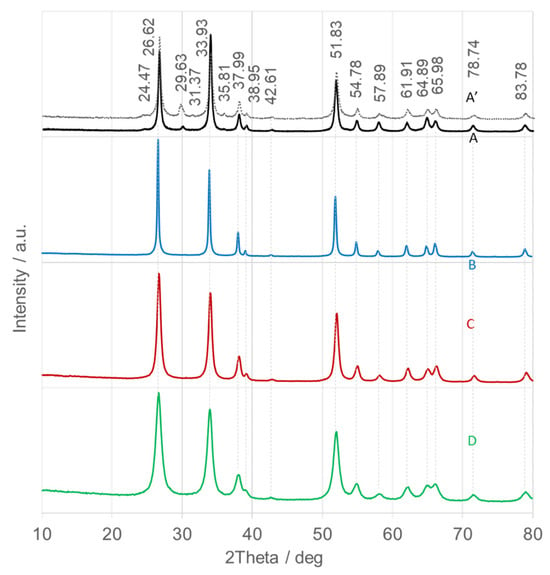

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed to determine the optimal calcination temperature. Figure 3 shows the TGA curves for all examined oxides. The SnO2NPs-A sample, synthesized via the wet chemical route, exhibits a distinct thermal decomposition profile compared with samples B–D, obtained through green synthesis using extracts from rooibos leaves (B), pomegranate seeds (C), and kiwifruit peels (D). Samples B–D show gradual three-step weight losses, while sample A undergoes a rapid mass reduction between 350–375 °C. An 18% weight loss in this region corresponds to the volatilization of tin as Sn2+ (Sn(OH)Cl) and formation of SnO2 [41]. A slight 1% increase in mass between 400–600 °C is attributed to oxidation processes, followed by a further 2% weight loss above 600 °C. Consequently, SnO2NPs-A were calcined at 400 °C (sample A’) and 600 °C (sample A).

Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of as-prepared SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via (A) the wet-chemistry method and the green synthesis method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

For samples B–D, stage I (~150 °C) is associated with dehydration, resulting in minor mass losses of 4% (SnO2NPs-B), 6% (SnO2NPs-C), and 6% (SnO2NPs-D). Stage II corresponds to gradual dehydroxylation occurring between 150–700 °C (SnO2NPs-B), 150–600 °C (SnO2NPs-C), and 150–500 °C (SnO2NPs-D), accompanied by oxidation of organic residues from the plant extracts, producing CO2 and H2O. The associated weight losses are 37%, 12%, and 16%, respectively. Stage III, beginning between 500–700 °C, involves less than 2% weight loss, indicating stabilization of the crystalline oxide phases. Based on these results, the calcination temperatures were set at 700 °C for SnO2NPs-B, 600 °C for SnO2NPs-A and SnO2NPs-C, and 500 °C for SnO2NPs-D. The corresponding diffraction patterns are presented in Figure 4.

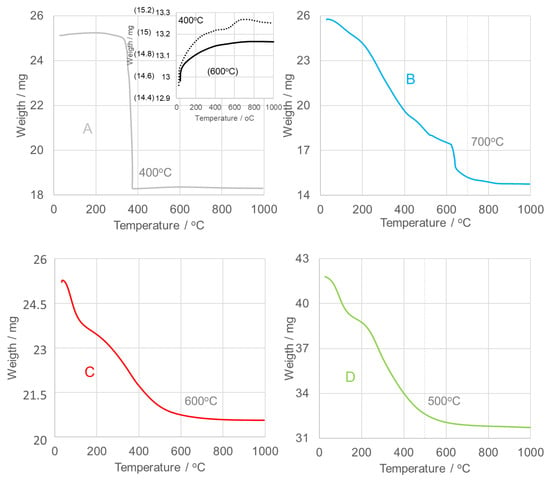

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via the wet-chemistry method (A, calcined at 400 °C and A’, at 600 °C), and via the green chemistry method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

Figure 4 displays the XRD patterns of the calcined SnO2NPs, which match the tetragonal rutile-type SnO2 phase (space group P42/mnm; JCPDS No. 41-1445), with lattice parameters a = b = 4.738 Å and c = 3.187 Å. The main diffraction peaks correspond to the following Miller indices: 26.6° (110), 33.9° (101), 38.0° (200), 51.8° (211), 54.8° (220), 57.9° (002), 61.9° (310), 64.9° (112), 66.0° (301), 78.7° (202), and 83.8° (321) [42]. The absence of peaks from other tin oxides or metallic tin confirms the high phase purity of the synthesized SnO2NPs. The high intensity and narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the reflections indicate well-crystallized materials. The FWHM values increase slightly in the following order: SnO2NPs-B (calcined at 700 °C, Figure 4, trace B) < SnO2NPs-A (600 °C, Figure 4, trace A) < SnO2NPs-A’ (400 °C, Figure 4, trace A’) < SnO2NPs-C (600 °C, Figure 4, trace C) < SnO2NPs-D (500 °C, Figure 4, trace D), implying a gradual decrease in crystallite size.

For SnO2NPs-A calcined at 600 °C (Figure 4, trace A), the (101) diffraction is approximately 25% more intense than the (110) reflection, suggesting preferential growth along the (101) direction. In contrast, SnO2NPs-A’ (400 °C) and all green-synthesized samples, show dominant (110) reflection, indicating preferential exposure of the (110) surface. Crystallite sizes were estimated using the Debye–Scherrer equation, and the results are summarized in Table 1. As expected, crystallite size decreases gradually with decreasing calcination temperature [43].

Table 1.

Surface analysis results of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs).

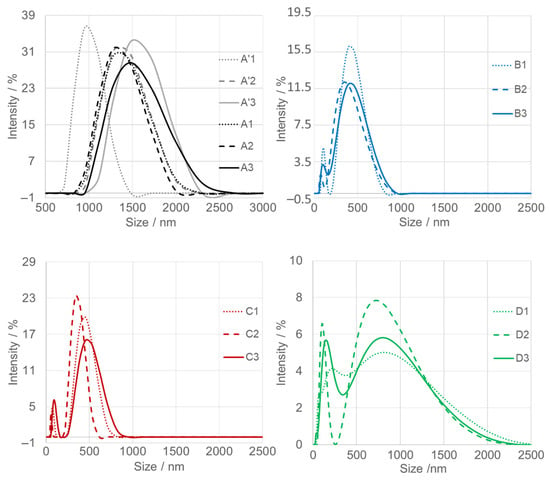

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis (Figure 5) was conducted in triplicate for each SnO2NPs suspension (dotted, dashed, and solid traces) to ensure the reproducibility of the particle size distribution profiles. Prior to measurement, all aqueous suspensions were sonicated; however, dispersions exhibited limited stability, leading to gradual sedimentation. Slight variations were observed between consecutive measurements. The first measurement, representing the “largest population,” is denoted as “1.” Over time, in stages two and three, the nanoparticles underwent gravitational settling, which resulted in a decrease in apparent hydrodynamic diameter. The average particle sizes estimated from DLS are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via the wet-chemistry method (A, calcined at 400 °C and A’, at 600 °C), and via the green chemistry method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

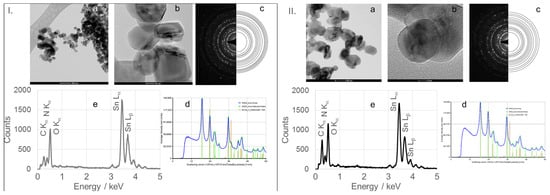

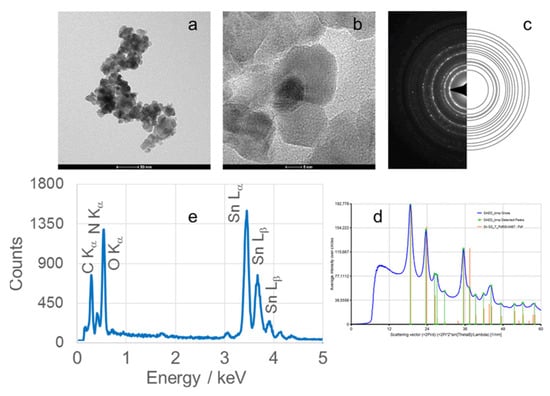

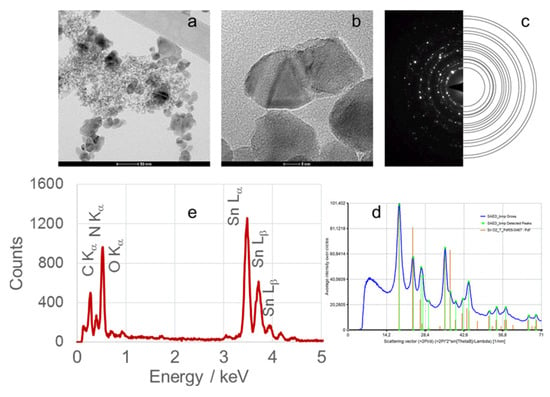

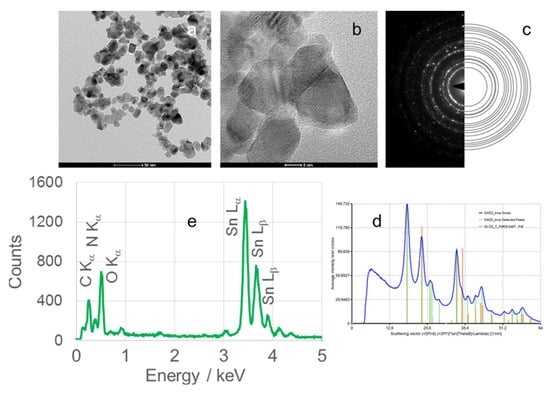

TEM micrographs, obtained at magnifications of 50 or 100 nm, of calcined SnO2NPs synthesized via the wet chemical route and green synthesis using rooibos leaves, pomegranate seeds, and kiwifruit peel extracts are shown in Figure 6 (images Ia and IIa), Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 (images a), respectively. These images reveal predominantly spherical nanoparticles, homogeneously distributed and forming agglomerates. Such aggregation is attributed to attractive van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions (especially in high-ionic-strength or extreme pH environments) [44], and Ostwald ripening phenomena [45].

Figure 6.

(a) TEM image, (b) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image, (c) selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, (d) circularly averaged intensity from SAED as a function of the scattering vector, and (e) EDS analysis of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via the wet-chemistry method and calcined at 400 °C (I) and at 600 °C (II).

Figure 7.

(a) TEM image, (b) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image, (c) selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, (d) circularly averaged intensity from SAED as a function of the scattering vector, and (e) EDS analysis of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized using rooibos leaf extract and calcined at 700 °C.

Figure 8.

(a) TEM image, (b) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image, (c) selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, (d) circularly averaged intensity from SAED as a function of the scattering vector, and (e) EDS analysis of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized using pomegranate seed extract and calcined at 600 °C.

Figure 9.

(a) TEM image, (b) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image, (c) selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, (d) circularly averaged intensity from SAED as a function of the scattering vector, and (e) EDS analysis of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized using kiwifruit peel extract and calcined at 500 °C.

High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images (Figure 6(Ib,IIb), Figure 7b, Figure 8b and Figure 9b) confirm the formation of well-defined spherical crystallites with clear lattice fringes, indicative of high crystallinity. The measured d-spacings between adjacent lattice planes were 0.26, 0.19, 0.17, 0.12, and 0.12 nm for SnO2NPs synthesized via the wet chemistry method (calcined at 400 °C and 600 °C) and with extracts from rooibos, pomegranate, and kiwifruit, respectively.

The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (Figure 6(Ic,IIc), Figure 7c, Figure 8c and Figure 9c) display continuous concentric rings, confirming the polycrystalline nature of the SnO2NPs. SAED patterns were converted into radial diffraction profiles (Figure 6(Id,IId), Figure 7d, Figure 8d and Figure 9d) using software that represents the circularly averaged diffraction intensity as a function of the scattering vector. Analysis of the intensity maxima corresponding to diffraction spots allowed for the calculation of d-spacing values, summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

d-spacing values of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) determined from circularly averaged intensity in SAED as a function of the scattering vector length.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) profiles (Figure 6(Ie,IIe), Figure 7e, Figure 8e and Figure 9e) provide additional confirmation of SnO2 formation. All spectra exhibit four characteristic peaks in the 0.5–4.0 keV range [46]. Table 1 lists the corresponding energies for each oxide. Small peaks at approximately 0.26 keV (C Kα) and 0.39 keV (N Kα) were observed in all samples, attributed to residual gases (CO and N2) in the TEM chamber [47]. No additional peaks were detected, confirming the phase purity of the SnO2NPs.

The Sn and O atomic percentages reported in Table 1 show clear deviations from the ideal SnO2 stoichiometry (O:Sn = 2:1). Specifically, the measured values are: O = 48.22 at.%/Sn = 30.46 at.%, O = 42.99 at.%/Sn = 36.84 at.%, O = 57.33 at.%/Sn = 22.52 at.%, O = 54.75 at.%/Sn = 28.01 at.%, and O = 42.81 at.%/Sn = 39.87 at.%. These deviations are consistent with literature-reported atomic percentages obtained from EDS analyses of SnO2, which typically show a broad range depending on synthesis method, sample preparation, and measurement conditions. In particular, oxygen content in EDS studies can vary from ~50 to 81 at.% and tin from ~7 to 33 at.% [48,49,50,51], although highly stoichiometric commercial powders often exhibit O ≈ 80 at.% and Sn ≈ 19–20 at.% [48,49,50,51]. The discrepancies observed in Table 1 can therefore be attributed to factors such as the lower sensitivity of EDS to oxygen, the presence of surface contaminants or substrate effects, differences in quantification algorithms, and the limited probing depth of EDS compared to surface-sensitive techniques such as XPS. Consequently, deviations from the ideal O/Sn ratio of 2:1 are frequently reported and should be considered typical for EDS characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles.

Growing evidence indicates that the synthesis route plays a decisive role in determining the degree of non-stoichiometry in SnO2. In particular, green chemistry approaches—employing plant extracts as reducing, capping, and complexing agents—often produce materials that are more oxygen-deficient (SnO2−x) than those obtained by conventional routes. Plant extracts contain polyphenols, sugars, proteins, and other phytochemicals, which create locally oxygen-deficient environments during nucleation and crystallization. This promotes the formation of oxygen vacancies and partial reduction of Sn4+ to Sn2+, both of which are well-established indicators of non-stoichiometry [52,53]. Green-synthesized SnO2 nanoparticles frequently exhibit spectral signatures of vacancy-related defects (PL, EPR), mixed Sn4+/Sn2+ chemical states in XPS, and visible color tints associated with oxygen deficiency, which are often more pronounced than in conventionally synthesized reference materials [54,55,56]. Importantly, low-temperature wet-chemical methods (<150–200 °C)—including sol–gel and biosynthesis—do not provide sufficient thermal energy or oxygen mobility to fully oxidize tin to Sn4+, further stabilizing oxygen-deficient SnO2−x phases [57].

At the same time, the extent of non-stoichiometry in SnO2 is not dictated solely by the synthesis route, but also by factors such as oxygen partial pressure, temperature, presence of reducing species, and post-treatment conditions. High-temperature treatments (>500–600 °C) in oxygen-rich atmospheres promote re-oxidation and vacancy annihilation, shifting the material toward stoichiometric SnO2, whereas low-temperature synthesis (≤100 °C) under limited oxygen availability favors stabilization of oxygen-deficient SnO2−x [57,58,59]. Therefore, green-synthesized SnO2 nanoparticles and low-temperature wet-chemical routes converge mechanistically toward the same outcome: increased oxygen deficiency and higher deviation from ideal stoichiometry, driven by limited oxidation potential and restricted defect annealing—a trend consistently observed across studies on SnO2 defect chemistry [58,59].

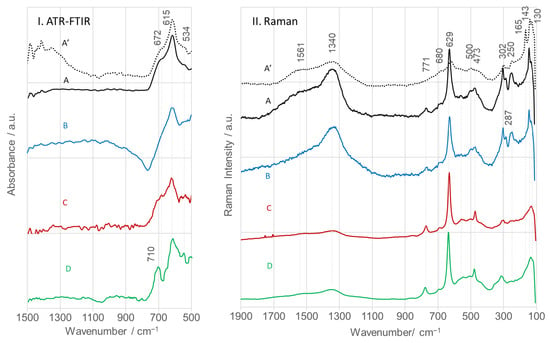

ATR-FTIR spectra of calcined SnO2NPs (Figure 10I) exhibit characteristic bands at 672, 615, and 534 cm−1, assigned to ν(O–Sn–O), ν(Sn–O), and ν(Sn–O, TO) modes, respectively [31]. Y. Zhang et al. alternatively assigned the 615 and 534 cm−1 bands to antisymmetric (Eu, TO) and symmetric (A2u, TO) Sn–O–Sn vibrations [60]. The observed deviations in wavenumbers relative to literature values (618 and 477 cm−1) can be attributed to differences in particle size and morphology. All spectral features observed are consistent with IR bands reported for SnO2 synthesized via wet chemistry and calcined at 500 °C [30]. Discrepancies reported in other studies [61,62] likely result from differences in phase composition (monocrystal, powder, sol), defect density, stoichiometry, and morphology [63,64,65,66].

Figure 10.

ATR-FTIR (I) and Raman (II) spectra of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via (A, calcined at 400 °C and A’, at 600 °C) the wet-chemistry method and the green chemistry method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

SnO2 with a tetragonal rutile structure (point group D4h14, space group P42/mnm) contains two Sn4+ cations (coordination number 6) and four O2− anions (coordination number 3) per unit cell [67]. Group theory predicts the following vibrational modes at the Γ point of the Brillouin zone: Γ = Γ+1(A1g) + Γ+2(A2g) + Γ+3(B1g) + Γ+4(B2g) + 2Γ−5(Eg) + 2Γ−1(A2u) + 2Γ−4(B1u) + 4Γ+5(Eu). Among these, B1g, Eg, A1g, and B2g are Raman active [43,68].

Raman spectra (Figure 10II) display distinct peaks at 143, 473, 629, and 771 cm−1, corresponding to these modes [69]. The 629 and 771 cm−1 bands arise from Sn–O stretching vibrations. In the A1g mode, two bonds shorten while the remaining four expand, whereas in the B2g mode, all six Sn–O bonds vibrate in phase. The 629 cm−1 feature is intense in highly crystalline nanoparticles (>75–100 nm) but broadens and downshifts as particle size decreases [69]. In contrast, the 473 and 771 cm−1 bands increase in relative intensity with decreasing particle size, consistent with the present data.

Additional Raman bands at 143 (A2g) and 165 cm−1 (B1g) were observed for SnO2NPs synthesized by the wet chemistry route and with rooibos extract. These are attributed to displacement of O2− ions from the diagonal plane, likely caused by rotation of the O–Sn–O bond around the Sn4+ axis. The 165 cm−1 mode, detected only in SnO2NPs-A calcined at 400 °C, is associated with oxygen vacancies and local disorder in the (200) planes [65]. An additional IR-active band at 302 cm−1 was detected in all spectra [29]. The SnO2NPs-A and SnO2NPs-B samples exhibited medium-intensity 302 cm−1 bands, while weaker responses were noted in the other samples. The presence of this feature confirms reduced nanoparticle size and surface defects, such as oxygen vacancies, which significantly influence their electronic and catalytic properties [70].

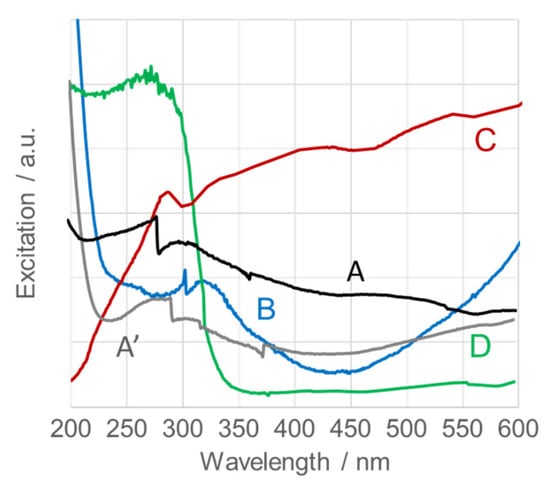

Figure 11 shows the UV–Vis spectra of calcined SnO2NPs in the 200–600 nm range. The absorption edge, corresponding to bandgap transitions, appears in the UV region. The absorption maxima and corresponding bandgap energies, calculated using Tauc’s relation, are summarized in Table 1 [71]. The observed bandgaps exhibit a blue shift compared to the theoretical value for bulk tetragonal rutile SnO2 (Eg = 3.64 eV) and previously reported 2D nanosheets (λabs = 280 nm) and SnO2 nanoparticles (λabs = 260–285 nm, 2–5 nm in diameter) synthesized by solvothermal processes [57,72]. A red shift relative to hydrothermally prepared SnO2NPs (λabs = 370 nm, 11–12 nm) [73] is also evident. These results agree well with reported data for SnO2 (λabs ≈ 325 nm, 10–15 nm) [74]. The observed blue shift with decreasing nanoparticle size confirms the quantum confinement effect, demonstrating that the bandgap energy of calcined SnO2NPs increases inversely with particle size.

Figure 11.

UV-Vis spectra of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via (A, calcined at 400 °C and A’, at 600 °C) the wet-chemistry method and the green chemistry method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

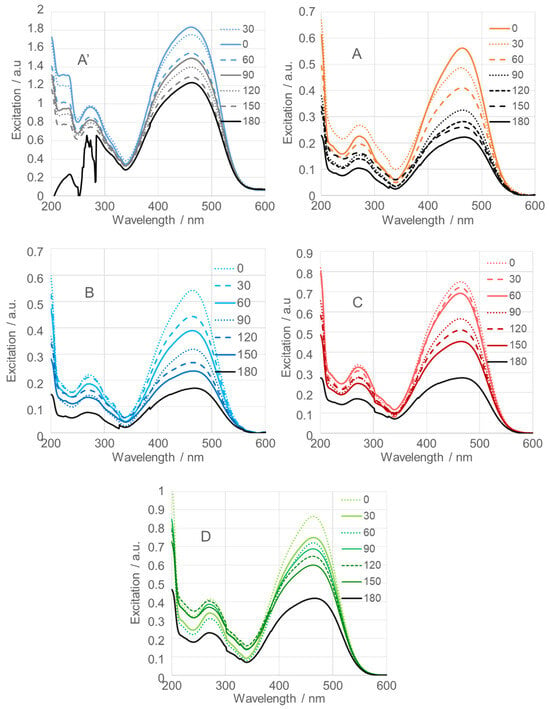

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity

Figure 12 presents the time-dependent excitation spectra of methyl orange (MeO), a common synthetic azo dye. MeO was used to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of SnO2NPs under 365 nm light irradiation. A mixture containing SnO2NPs, MeO, and distilled water in a molar ratio of approximately 1:4.5:8 was irradiated. Spectra were recorded every 30 min over a 180 min irradiation period, starting immediately after mixing (0 min).

Figure 12.

Photodegradation efficiency of calcined SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized via the wet-chemistry method (A, calcined at 400 °C and A’, at 600 °C) and the green chemistry method using extracts from (B) rooibos leaves, (C) pomegranate seeds, and (D) kiwifruit peels.

As shown in the figure, SnO2NPs obtained using rooibos leaf extract (Figure 12B), with an average crystallite size of 71.1 nm, exhibited the highest photocatalytic efficiency, degrading 68% of MeO within 180 min. In contrast, SnO2NPs synthesized using kiwifruit extract, with a crystallite size of 18.2 nm, achieved a degradation efficiency of 52% (Figure 12D), while those prepared from pomegranate seed extract, with a crystallite size of 27.9 nm, showed a 63% degradation efficiency (Figure 12C).

SnO2NPs prepared by the wet chemical method (Figure 12A, calcined at 600 °C, and Figure 12A’, calcined at 400 °C) displayed degradation efficiencies of 60% and 33%, respectively, corresponding to crystallite sizes of 43.6 and 37.4 nm. Table 1 summarizes the photocatalytic efficiencies of all investigated SnO2NPs.

3.3. Adsorption Monitored by SERS

Tin (Sn) is generally considered an inactive transition metal in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). To effectively amplify the Raman signal on Sn and SnO2 nanostructures, SERS experiments typically require ultraviolet excitation or Sn/SnO2 nanostructures coated or doped by noble metals. This approach exploits the enhanced electromagnetic field at the rough nanoscale surface of noble metals. The enhanced field of the noble metal surface penetrates the interface between the transition metal and the surrounding medium, where SERS excitation occurs.

Previous studies have employed gold-coated SnO2 nanoparticles to monitor the adsorption of ciprofloxacin [75] and pyridine [76]; Cu-doped SnO2–NiO heterostructures have been used to detect volatile organic compounds [77]; and Ag-coated SnO2NPs have been applied for rhodamine 6G sensing [78]. In contrast, two reports demonstrated the use of pure SnO2 nanoparticles as SERS-active substrates. Jiang et al. showed that octahedral SnO2 nanoparticles effectively monitored 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA) and 4-nitrobenzenethiol (4-NBT) adsorbed on their surfaces [79], while Hou et al. employed sol-hydrothermally prepared SnO2 nanoparticles as SERS substrates for 4-MBA detection [80]. Notably, both 4-MBA and 4-NBT are high-symmetry aromatic molecules containing lone-pair-rich functional groups, which exhibit strong affinity toward metallic surfaces. The present study represents the third reported example of using SnO2NPs as a SERS substrate, but the first involving biologically active, low-symmetry molecules.

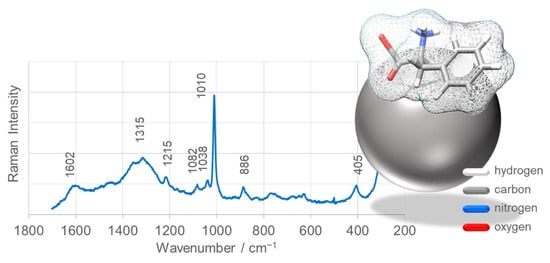

Figure 13 presents the SERS spectrum of L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) adsorbed onto SnO2NPs-B, synthesized using rooibos leaf extract and calcined at 700 °C. These nanoparticles were selected due to their superior photocatalytic efficiency in methyl orange degradation. The spectrum displays enhanced bands at 1602 (ν8a and ν8b), 1315 (ν14), 1215 (ν7a), 1082 (ν18b), 1038 (ν18a), 1010 (ν12), and 886 cm−1 (ν10a), corresponding to characteristic vibrations of the aromatic ring of L-Phe [81,82,83]. These results indicate that L-Phe predominantly interacts with the SnO2NP surface via its phenyl ring.

Figure 13.

SERS spectra of L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) adsorbed on the surface of SnO2 nanoparticles (SnO2NPs) synthesized using rooibos leaf extract. Insets: Proposed adsorption geometry of L-Phe on the SnO2NP surface.

Detailed analysis of band intensities, wavenumbers, and full width at half maximum (FWHM), particularly the ν12 mode, provides insights into the orientation of the aromatic ring on the nanoparticle surface. The ν12 band is shifted to lower frequencies by 8 cm−1, broadened (ΔFWHM = +4 cm−1), and less enhanced compared with the corresponding Raman band, suggesting a tilted orientation of the phenyl ring relative to the SnO2NP surface. Additionally, a broad feature with two maxima at 1315 and 1360 cm−1 is observed, corresponding to ν(CH2) and νs(COO2) vibrations, further supporting a tilted ring configuration in which the aliphatic fragment and carboxyl group are directed toward the SnO2NP surface (Figure 13).

These observations reinforce the concept that the adsorption behavior and molecular orientation on a nanoparticle surface are strongly substrate-dependent. For instance, on Zn and ZnO nanoparticles, L-phenylalanine interacts primarily via its aromatic ring [84]; on AgNPs, both the aromatic ring and carboxyl group participate [82]; on MgO nanoparticles, the aromatic ring and amino group are involved [85]; and on AuNPs or iron oxide nanoparticles (α-Fe and γ-Fe2O3), simultaneous coordination via the aromatic ring, amino, and carboxyl groups has been reported [86,87].

The SERS enhancement factor (EF), quantifying the substrate’s effectiveness, was calculated for the SnO2NPs and compared with previously reported values for other SERS-active materials. The EF for SnO2NPs reached up to 102, comparable to MgO, Zn, Pt, and Fe substrates, yet lower than those for AgNPs and Au@SiO2 (106), AuNPs (105), Cu and Ti (104), and ZnO-, CuO-, Cu2O-, TiO2-, and γ-Fe2O3-based nanostructures (103) [82,84,85,86,87,88,89].

4. Conclusions

This study reports the synthesis, structural characterization, and functional evaluation of four types of tin dioxide nanoparticles (SnO2NPs). One sample was obtained using a conventional chemical method, while the other three were synthesized via an environmentally friendly green chemistry approach employing reducing agents naturally present in plant extracts. Three easily accessible plants—pomegranate seeds, rooibos leaves, and kiwi fruit peels—were selected as sources of phytochemicals responsible for nanoparticle formation.

The crystalline nature of SnO2NPs plays a decisive role in determining their stability, cytotoxicity, and biocompatibility—parameters that are crucial for biomedical applications. Therefore, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was employed to determine the crystalline structure of the as-prepared nanoparticles. The results indicated that the non-calcined SnO2NPs were predominantly amorphous, which necessitated thermal treatment. The calcination temperature for each sample was selected based on thermogravimetric (TGA) analysis. XRD patterns obtained after calcination revealed the preferred crystallite growth orientations: (110) for SnO2NPs-A synthesized by the wet-chemical method and calcined at 600 °C, and (101) for SnO2NPs-A’ calcined at 400 °C, as well as for samples synthesized using plant extracts. The average crystallite size ranged from 18.2 to 71.1 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses showed a relatively homogeneous morphology consisting of agglomerated spherical particles and a controlled size distribution, with the mean particle size variation in suspension not exceeding 19% (SnO2NPs-A’), 13% (SnO2NPs-B), 9% (SnO2NPs-C), and 3% (SnO2NPs-A and SnO2NPs-D). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed the elemental composition and the absence of toxic impurities, further supporting their potential biocompatibility.

UV–Vis spectra revealed that the synthesized SnO2NPs exhibit reduced optical bandgap values (3.81–4.59 eV) compared to bulk SnO2, which enhances their surface reactivity and potential osseointegration. Raman and ATR-FTIR analyses confirmed the formation of non-stoichiometric oxides containing oxygen vacancy defects, which may contribute to their photocatalytic and sensing performance.

Photocatalytic tests demonstrated that SnO2NPs synthesized using rooibos extract (SnO2NPs-B) showed the highest activity, degrading 68% of methyl orange under UV irradiation within 180 min. Owing to their superior photocatalytic efficiency, SnO2NPs-B were further employed as a SERS-active substrate for studying the adsorption of L-phenylalanine (L-Phe). The obtained SERS spectra confirmed the sensitivity of these nanoparticles toward biologically active molecules and their ability to probe molecular interactions at the surface of bone scaffold materials.

Overall, this work provides the third reported example of using pure SnO2 nanoparticles as a SERS substrate, and the first demonstration of their applicability for biologically active compounds and molecules of low symmetry. The findings highlight the potential of green-synthesized SnO2NPs as multifunctional materials—combining photocatalytic, sensing, and biocompatible properties—which can be further developed for biomedical and environmental applications.

Author Contributions

E.P.: funding acquisition, research concept and design, synthesis using the wet-chemistry method, ATR-FTIR, Raman, SERS, UV–Vis, and catalytic activity measurements, data analysis and interpretation, figure preparation, manuscript drafting, and correspondence with reviewers. M.G.: TEM and EDS measurements. O.S. and M.M.: TGA, XRD, and DLS measurements, and thermal treatment of the samples. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Center (Poland) under Grant No. 2023/49/B/ST4/00077 awarded to Edyta Proniewicz, and by the AGH University of Krakow (Subsidy No. 16.16.170.654).

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request (proniewi@agh.edu.pl).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to student Wiktor Głąb for performing the synthesis of nanoparticles using extracts from rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) leaves, pomegranate (Punica granatum) seeds, and kiwifruit (Actinidiaceae family) peels.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karmaoui, M.; Jorge, A.B.; McMillan, P.F.; Aliev, A.E.; Pullar, R.C.; Labrincha, J.A.; Tobaldi, D.M. One-Step Synthesis, Structure, and Band Gap Properties of SnO2 Nanoparticles Made by a Low Temperature Nonaqueous Sol–Gel Technique. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13227–13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Wang, S.F.; Lu, M.K.; Zhou, G.J.; Xu, D.; Yuan, D.R. Photoluminescence Properties of SnO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Sol-Gel Method. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 8119–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbanda, J.; Priya, R. Synthesis and Applications of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: An Overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 68, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. Optical Properties of Tin Oxide Nanomaterials. In Tin Oxide Materials: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications; Orlandi, M.O., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; Chapter 4; pp. 61–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Su, P.; Chen, H.; Qiao, M.; Yang, B.; Zhao, X. Impact of Reactive Oxygen Species on Cell Activity and Structural Integrity of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria in Electrochemical Disinfection System. Chem. Eng. 2023, 452, 138879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridasappa, A.; Shareef, M.I.; Gopinath, S.M.; Rangappa, D.; Shivaramu, P.; Sabbanahalli, C. Synthesis, Antioxidant, Bactericidal and Antihemolytic Activity of Al2O3 and SnO2 Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 93, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, K.; Mozgawa, B.; Kusior, A.; Pietrzyk, P.; Sojka, Z.; Radecka, M. Tunable Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species in SnO2/SnS2 Nanostructures: Mechanistic Insights into Indigo Carmine Photodegradation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 128, 5011–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y. Recent Advances in SnO2 Nanostructure Based Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 364, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, M.A.; Neelamegan, H.; Priyadharshini, V.J.; Ahamed, S.R.; Arularasan, P.; Mishra, M.; Rather, A.A. Enhancing Superca-pacitor, Photovoltaic and Magnetic Properties of SnO2 Nanoparticles Doped with Cu and Zn Ions. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2024, 47, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.G.; Di Mario, L.; Yan, F.; Ibarra-Barreno, C.M.; Mutalik, S.; Protesescu, L.; Rudolf, P.; Loi, M.A. Understanding the Surface Chemistry of SnO2 Nanoparticles for High Performance and Stable Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2307958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Q. Preparation and Performance of SnO2 Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Carbon Nanofibers as Anodes for Lithium-Ion Battery. Mater. Lett. 2023, 352, 135076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, S.U.; Kiani, S.H.; Haq, S.; Ahmad, P.; Khandaker, M.U.; Faruque, M.R.I.; Idris, A.M.; Sayyed, M.I. Bio-Synthesized Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: Structural, Optical, and Biological Studies. Crystals 2022, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Asiri, S.M.; Khan, F.A.; Jermy, B.R.; Khan, H.; Akhtar, S.; Jindan, R.A.; Khan, K.M.; Qurashi, A. Biocompatible Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Antibacterial, Anticandidal and Cytotoxic Activities. Chem. Select 2019, 4, 44013–44017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.G.S.V.; Phani, A.R.; Rao, K.N.; Kumar, R.R.; Prasad, S.; Prabhakara, G.; Sheeja, M.S.; Salins, C.P.; Endrino, J.L.; Raju, D.B. Biocompatible and Antibacterial SnO2 Nanowire Films Synthesized by E-Beam Evaporation Method. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 11, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, V.B.; Thetiot, F.; Ritz, S.; Putz, S.; Choritz, L.; Lappas, A.; Forch, R.; Landfester, K.; Jonas, U. Antibacterial Surface Coatings from Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Embedded in Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel Surface Layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 2376–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagadevan, S.; Lett, J.A.; Fatimah, I.; Lokanathan, Y.; Léonard, E.; Oh, W.C.; Hossain, M.A.M.; Johan, M.R. Current Trends in the Green Syntheses of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 082001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Li, Y.L.; Li, M.; Cao, J.; Cheng, J.; Wei, D.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Jia, D.; Jiang, B.; et al. Electrical Responsive Coating with a Multilayered TiO2–SnO2–RuO2 Heterostructure on Ti for Controlling Antibacterial Ability and Improving Osseointegration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 39064–39078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-H.; Liao, H.-T.; Chen, R.-S.; Chiu, S.-C.; Tsai, F.-Y.; Lee, M.S.; Hu, C.-Y.; Tseng, W.-Y. The Influence on Surface Characteristic and Biocompatibility of Nano-SnO2–Modified Titanium Implant Material Using Atomic Layer Deposition Technique. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2023, 122, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Díez-Vicente, A. Antibacterial SnO2 Nanorods as Efficient Fillers of Poly(Propylene Fumarate-Co-Ethylene Glycol) Biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 1, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhria, A.; Behrouzb, S. Synthesis, Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Properties of SnO2, SnS2 and SnO2/SnS2 Nanostructure. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 149, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dai, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B. Antibacterial Activity of SnO2 in Visible Light Enhanced by Erbium–Cobalt Co-Doping. Colloids Surf. A 2023, 676, 132257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamagous, G.A.; Ibrahim, I.A.A.; Alzahrani, A.R.; Shahid, I.; Shahzad, N.; Falemban, A.H.; Alanazi, I.M.M.; Hussein-Al-Ali, S.H.; Arulselvan, P.; Thangavelu, I. Multifunctional SnO2–Chitosan–D-Carvone Nanocomposite: A Promising Antimicrobial, Anticancer, and Antioxidant Agent for Biomedical Applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 3111–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Qian, B. Exploring the Anticancer Effects of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized by Pulsed Laser Ablation Technique against Breast Cancer Cell Line Through Downregulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Chen, R.; Yu, H. Synthesized Tin Oxide Nanoparticles Promote Apoptosis in Human Osteosarcoma Cells. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, D.H.; Saad, G. Induction of Mitochondria Mediated Apoptosis in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells by Folic Acid Coated Tin Oxide Nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamed, M.; Akhtar, M.J.; Majeed Khan, M.A.; Alhadlaq, H.A. Oxidative Stress Mediated Cytotoxicity of Tin (IV) Oxide (SnO2) Nanoparticles in Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cells. Colloids Surf. B 2018, 172, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadabada, L.E.; Kalantaria, F.S.; Liu, H.; Hasan, A.; Gamasaee, N.A.; Edis, Z.; Attar, F.; Ale-Ebrahim, M.; Rouholla, F.; Babadaei, M.M.N.; et al. Hydrothermal Method-Based Synthesized Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: Albumin Binding and Antiproliferative Activity Against K562 Cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Yang, G. Synthesis of L. Acidissima Mediated Tin Oxide Nanoparticles for Cervical Car-cinoma Treatment in Nursing Care. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, H. 2D SnO2 Nanosheets: Synthesis, Characterization, Structures, and Excellent Sensing Performance to Ethylene Glycol. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalric-Popescu, D.; Bozon-Verduraz, F. Infrared Studies on SnO2 and Pd/SnO. Catal. Today 2001, 70, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiotti, G.; Chiorino, A.; Boccuzzi, F. Infrared study of surface chemistry and electronic effects of different atmospheres on SnO2. Sens. Actuators B 1989, 19, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.L. Growth mode of the SnO2 nanobelts synthesized by rapid oxidation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 376, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Yuan, S.; Cao, B.; Yu, J. SnO2 nanotube arrays grown via an in situ template-etching strategy for effective and stable perovskite solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 325, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, R.; Xiu, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zha, G. Growth of SnO2 nanoparticles via thermal evaporation method. Superlattices Microstruct. 2011, 50, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-B.; Wang, X.-W.; Shen, Q.; Zheng, J.; Liu, W.-H.; Zhao, H.; Yang, F.; Yang, H.-Q. Controllable Low-Temperature Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth and Morphology Dependent Field Emission Property of SnO2 Nanocone Arrays with Different Mor-phologies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 3033–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, G.H.; Chakia, S.H.; Kannaujiya, R.M.; Parekh, Z.R.; Hirpara, A.B.; Khimani, A.J.; Deshpande, M.P. Sol–gel synthesis and thermal characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles. Phys. B 2021, 613, 412987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 on the Landfill of Waste. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1999/31/oj?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Waste Framework Directive legislation. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/pl/wfd-legislation?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Marakatti, V.S.; Shanbhag, G.V.; Halgeri, A.B. Condensation reactions assisted by acidic hydrogen bonded hydroxyl groups in solid tin(II) hydroxychloride. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 10795–10800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocafia, M.; Serna, C.J.; Matijevic, E. Formation of “monodispersed” SnO2 powders of various morphologies. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 1995, 273, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séby, F.; Potin-Gautier, M.; Giffaut, E.; Donard, O.F.X. A critical review of thermodynamic data for inorganic tin species. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2001, 65, 3041–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.E.; Kajale, D.D.; Gaikwad, V.B.; Jain, G.H. Preparation and characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles by hydrothermal route. Int. Nano Lett. 2012, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, J.; Hasan, R.; Biswas, B.; Ahmed, F.; Mostofa, S.; Akhtar, U.S.; Hossain, K.; Quddus, S.; Ahmed, S.; Sharmin, N.; et al. Effect of low temperature calcination on microstructure of hematite nanoparticles synthesized from waste iron source. Heliyon 2024, 10, e411030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalousha, M. Aggregation and disaggregation of iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of particle concentration, pH and natural organic matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.A.; Franzén, A.; Carlert, S.; Skantze, U.; Lindfors, L.; Olsson, U. On the Ostwald ripening of crystalline and amorphous nanoparticles. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubi, Y.; Hartiti, B.; Batan, A.; Siadat, M.; Labrim, H.; Tahiri, M.; Kotbi, A.; Thevenin, P.; Jouiad, M. Controlled SnO2 nanostructures for enhanced sensing of hydrogen sulfide and nitrogen dioxide. Sens. Actuators B 2025, 440, 137878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettler, S.; Dries, M.; Hermann, P.; Obermair, M.; Gerthsen, D.; Malac, M. Carbon contamination in scanning transmission electron microscopy and its impact on phase-plate applications. Micron 2017, 96, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, W.; Izydorczyk, J. Structure, Surface Morphology, Chemical Composition, and Sensing Properties of SnO2 Thin Films in an Oxidizing Atmosphere. Sensors 2021, 21, 5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Optimization of Deposition Parameters of SnO2 Particles on Tubular Alumina Substrate for H2 Gas Sensing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.d.T.; Ahmed, Z.; Islam, M.d.J.; Kamaruzzaman; Khatun, M.d.T.; Gafur, M.d.A.; Bashar, M.d.S.; Alam, M.d.M. Comparative Study of Structural, Optical and Electrical Properties of SnO2 Thin Film Growth via CBD, Drop-Cast and Dip-Coating Methods. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjula, N.; Selvan, G.; Perumalsamy, R.; Thirumamagal, R.; Ayeshamariam, A.; Jayachandran, M. Synthesis, Structural and Electrical Characterizations of SnO2 Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2016, 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gebreslassie, Y.T.; Gebretnsae, H.G. Green and Cost-Effective Synthesis of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review on the Synthesis Methodologies, Mechanism of Formation, and Their Potential Applications. Nano Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero González, E.; Lugo Medina, E.; Quevedo Robles, R.V.; Garrafa Gálvez, H.E.; Baez Lopez, Y.A.; Vargas Viveros, E.; Aguilera Molina, F.; Vilchis Nestor, A.R.; Luque Morales, P.A. A Study of the Optical and Structural Properties of SnO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized with Tilia cordata Applied in Methylene Blue Degradation. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasisa, Y.E.; Sarma, T.K.; Sahu, T.K.; Sahu, T.K.; Krishnaraj, R. Phytosynthesis and characterization of tin-oxide nanoparticles (SnO2-NPs) from Croton macrostachyus leaf extract and its application under visible light photocatalytic activities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-S.; Yoon, S.O.; Park, H.J. Characteristics of SnO2 Annealed in Reducing Atmosphere. Ceram. Internat. 2005, 31, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, F.; Vosqa, U.t.; Khan, F.; Haleem, A.; Shaik, M.R.; Siddiqui, M.R.H.; Khan, M. Light-Driven Catalytic Activity of Green-Synthesized SnO2/WO3−x Hetero-Nanostructures. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 20042–20055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuntokun, J.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ebenso, E.E. Biosynthesis and Photocatalytic Properties of SnO2 Nanoparticles Prepared Using Aqueous Extract of Cauliflower. J. Clust. Sci. 2017, 28, 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagdal, I.A.; West, A.R. Oxygen Non-Stoichiometry, Conductivity and Gas Sensor Response of SnO2 Pellets. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 18119–18127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.W.; Seo, H.B.; Choi, J.; Bae, B.S.; Yun, E.-J. Effects of Process Parameters on the Properties of Sputter-Deposited Tin Oxide Thin Films. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, E.; Li, G. Two-Step Grain-Growth Kinetics of Sub-7 nm SnO2 Nanocrystals under Hydrothermal Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 19505–19512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridas, D.; Chowdhuri, A.; Sreenivas, K.; Gupta, V. Effect of Thickness of Platinum Catalyst Clusters on Response of SnO2 Thin Film Sensor for LPG. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 153, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliasih, N.; Buchari; Noviandri, I. Application of SnO2 Nanoparticle as Sulfide Gas Sensor Using UV/VIS/NIR Spectrophotometer. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 188, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, P. The Influence of Surface Defects on the Infrared Spectra of Adsorbed Species. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1992, 16, 51–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genzel, L.; Martin, T.P. Infrared Absorption by Surface Phonons and Surface Plasmons in Small Crystals. Surf. Sci. 1973, 34, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Investigation of Raman Spectrum for Nano-SnO2. Sci. China A 1997, 40, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ayoub, I.; Sharma, V.; Swart, H.C. (Eds.) Optical Properties of Metal Oxide Nanostructures; Springer: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 9789819956425. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, D.; Mo, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y. Enhanced Photocatalytic Properties of SnO2 Nanocrystals with Decreased Size for ppb-Level Acetaldehyde Decomposition. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Valmalette, J.C.; Kuruma, K.; Abe, H.; Takarada, T. Hydrothermal Growth of Tailored SnO2 Nanocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, P.; Sasirekha, V.; Ramakrishnan, V. Micro-Raman Investigation of Tin Dioxide Nanostructured Material Based on Annealing Effect. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011, 42, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tameh, M.S.; Gladfelter, W.L.; Goodpaster, J.D. Unraveling Surface Chemistry of SnO2 Through Formation of Charged Oxygen Species and Oxygen Vacancies. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2025, 125, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauc, J. Optical Properties and Electronic Structure of Amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 1968, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, K.; Rajendran, V. Size Controlled Synthesis of SnO2 Nanoparticles: Facile Solvothermal Process. J. Non-Oxide Glas. 2010, 2, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mayandi, J.; Marikkannan, M.; Ragavendran, V.; Jayabal, P. Hydrothermally Synthesized Sb- and Zn-Doped SnO2 Nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 2, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Godlaveeti, S.K.; Somala, A.R.; Sana, S.S.; Ouladsmane, M.; Ghfar, A.A.; Nagireddy, R. Evaluation of pH Effect of Tin Oxide (SnO2) Nanoparticles on Photocatalytic Degradation, Dielectric and Supercapacitor Applications. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 33, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Pei, J.; Yu, X.; Tian, Z.; Xu, H. Au–SnO2 Resonator for SERS Detection of Ciprofloxacin. Microchem. J. 2024, 203, 110830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Vidal, J.; Gómez-Marín, A.M.; Jones, L.A.H.; Yen, C.-H.; Veal, T.D.; Dhanak, V.R.; Hu, C.-C.; Hardwick, L.J. Long-Life and pH-Stable SnO2-Coated Au Nanoparticles for SHINERS. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 12074–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Gu, Q.; Qiu, T.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Qi, R.; Huang, R.; Zheng, T.; Tian, Y. Ultrasensitive Sensing of Volatile Organic Compounds Using a Cu-Doped SnO2–NiO p–n Heterostructure That Shows Significant Raman Enhancement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 26260–26267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.Y.; Zhang, W.; Lv, H.M.; Zhang, D.; Gong, X. Novel Ag-Decorated Biomorphic SnO2 Inspired by Natural 3D Nanostructures as SERS Substrates. Mater. Lett. 2012, 74, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yin, P.; You, T.; Wang, H.; Lang, X.; Guo, L.; Yang, S. Highly Reproducible Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectra on Semiconductor SnO2 Octahedral Nanoparticles. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13, 3932–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.L.; Jia, F.X.; Xue, X.X.; Chen, L.; Song, W.; Xu, W.Q.; Zhao, B. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering of Molecules Adsorbed on SnO2 Nanoparticles. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2012, 33, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawka, E.; Kudelski, A.; Proniewicz, L.M. Adsorption Mechanism of Physiologically Active L-Phenylalanine Phosphonodipeptide Analogues: Comparison of Colloidal Silver and Macroscopic Silver Substrates. Surf. Sci. 2007, 601, 4971–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawka, E.; Ozaki, Y.; Proniewicz, L.M. Part I: Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Investigation of Amino Acids and Their Homodipeptides Adsorbed on Colloidal Silver. Appl. Spectrosc. 2004, 58, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawka, E.; Borszowska, R.; Grabowska, M.; Drąg, M.; Kafarski, P.; Proniewicz, L.M. Investigation of Molecular Structure and Adsorption Mechanism of Phosphonodipeptides by Infrared, Raman, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. 2005, 599, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proniewicz, E.; Tąta, A.; Starowicz, M.; Wójcik, A.; Pacek, J.; Molenda, M. Is the Electrochemical or the Green Chemistry Method the Optimal Method for the Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles for Applications to Biological Material? Characterization and SERS on ZnO. Colloids Surf. A 2021, 609, 125771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proniewicz, E.; Vijayan, A.M.; Surma, O.; Szkudlarek, A.; Molenda, M. Plant-Assisted Green Synthesis of MgO Nanoparticles as a Sustainable Material for Bone Regeneration: Spectroscopic Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proniewicz, E.; Tąta, A.; Szkudlarek, A.; Świder, J.; Molenda, M.; Starowicz, M.; Ozaki, Y. Electrochemically Synthesized γ-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles as Peptide Carriers and Sensitive and Reproducible SERS Biosensors: Comparison of Adsorption on γ-Fe2O3 versus Fe. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 495, 143578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podstawka, E.; Ozaki, Y.; Proniewicz, L.M. Part III: Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering of Amino Acids and Their Homodipeptide Monolayers Deposited onto Colloidal Gold Surface. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005, 59, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tąta, A.; Szkudlarek, A.; Pacek, J.; Molenda, M.; Proniewicz, E. Peptides of Human Body Fluids as Sensors of Corrosion of Titanium to Titanium Dioxide: SERS Application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 473, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tąta, A.; Szkudlarek, A.; Kim, Y.; Proniewicz, E. Interaction of bombesin and its fragments with gold nanoparticles analyzed using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A 2017, 173, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).