Selective Excitation of Lanthanide Co-Dopants in Colloidal Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals as a Multilevel Anti-Counterfeiting Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Nanocrystal Synthesis

2.3. Measurements and Characterization

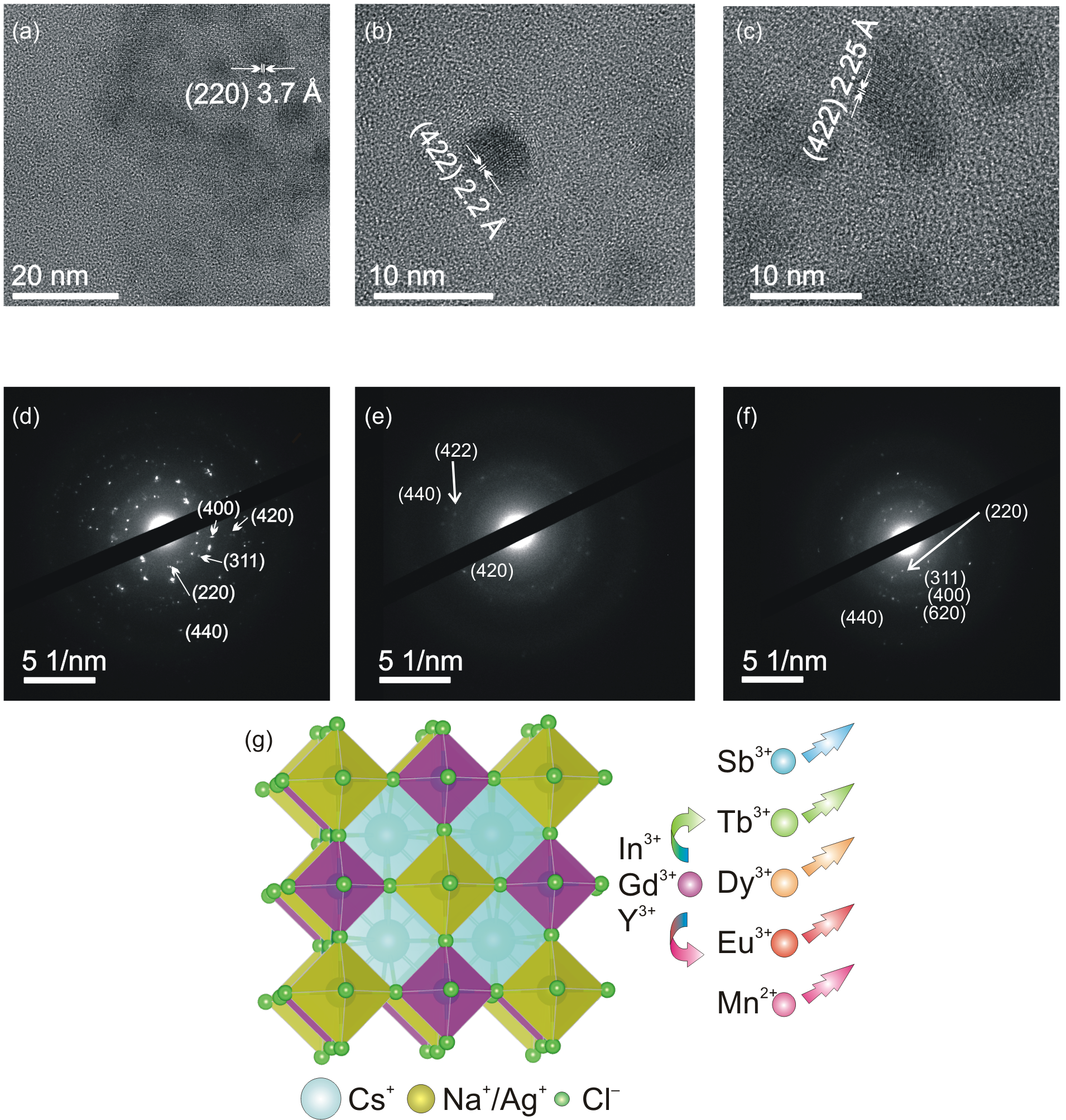

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bünzli, J.-C.G. Lanthanide photonics: Shaping the nanoworld. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.G.; Samuel, A.P.S.; Raymond, K.N. From antenna to assay: Lessons learned in lanthanide luminescence. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, P.; Debnath, G.H.; Waldeck, D.H.; Mukherjee, P. What is beyond charge trapping in semiconductor nanoparticle sensitized dopant photoluminescence? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6191–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Sim, J.M.; Lee, Y.S. Multi-color photoluminescence and persistent luminescence of Eu3+-doped Zn2GeO4 for security applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 180457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pang, R.; Wang, S.; Tan, T.; Su, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H. Bi3+/Eu3+ Co-activated multimode anti-counterfeiting material with white light emission and orange-yellow persistent luminescence. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Debnath, G.H.; Mukherjee, P. How important is the host (semiconductor nanoparticles) identity and absolute band gap in host-sensitized dopant photoluminescence? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 2794–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Men, L.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Mohammed, O.F. Rare earth double perovskites for underwater X-ray imaging applications. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 3469–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghy, P.; Brown, A.M.; Chu, C.; Dube, L.C.; Zheng, W.; Robinson, J.R.; Chen, O. Lanthanide double perovskite nanocrystals with emissions covering the UV-C to NIR spectral range. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2300277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Lee, K.J.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Chen, A.; Guo, C. Advancements in halide perovskite photonics. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2024, 16, 868–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hou, H.; Bai, Y.; Zeng, R. Luminescence regulation of rare-earth based double perovskites by doping and applications. J. Lumin. 2025, 277, 120990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balitskii, O.; Sytnyk, M.; Heiss, W. Recent developments in halide perovskite nanocrystals for indirect X-ray detection. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2400150. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Gong, X. Rare-earth-based lead-free halide double perovskites for light emission: Recent advances and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406424. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Gan, Z.; van Embden, J.; Jia, B.; Wen, X. Photon upconversion in metal halide perovskites. Mater. Today 2025, 86, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Xing, F.; Di, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, F.; Yang, X.; Yang, G.; et al. Five-level anti-counterfeiting based on versatile luminescence of tri-doped double perovskites. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 9971–9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, M.; Zou, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Hu, S.; Lin, J. Construction of energy transfer channels from [SbCl6]3− to Ln3+ (Ln3+ = Ho3+, Er3+) in Cs2NaGdCl6 for advanced anti-counterfeiting materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 12589–12597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zheng, B.; Fang, X.; Sun, X.; Hong, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Visible to near-infrared luminescence and reversible photochromism in Mn2+/Nd3+ co-doped double perovskite for versatile applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402515. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yang, N.; Ding, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, M.; Shi, J. Efficient and tunable white light emitting from Sb3+, Tb3+, and Sm3+ co-doped Cs2NaInCl6 double perovskite via multiple energy transfer processes. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 205, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liang, L.; Bun Pun, E.Y.; Lin, H. Kinetics-tunable photochromic platform in perovskites for advanced dynamic information encryption. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158416. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shang, M. Dual-color emitting in rare-earth based double perovskites Cs2NaLuCl6: Sb3+, Tb3+ for warm WLED and anti-counterfeiting. J. Lumin. 2025, 277, 120909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Lin, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z. Triple-mode fluorescent anti-counterfeiting and temperature sensing properties of lead-free double perovskites Cs2NaErCl6: Yb3+, Bi3+ microcrystals. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1008, 176630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Yang, H.; Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Tunable emission in Cs2NaGdCl6: Sb3+, Sm3+ double perovskite for cool white LEDs and anti-counterfeiting applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1025, 180269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, K.; Pi, X.; Zhou, S. Recent progress and future prospects on halide perovskite nanocrystals for optoelectronics and beyond. iScience 2022, 25, 105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Liisberg, M.B.; Lahtinen, S.; Soukka, T.; Vosch, T. Lanthanide-doped nanoparticles for stimulated emission depletion nanoscopy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 5817–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yin, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. Near-infrared spatiotemporal color vision in humans enabled by upconversion contact lenses. Cell 2025, 188, 3375–3388.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balitskii, O.; Kagabo, W.; Radovanovic, P.V. Composition-dependent Eu3+ emission in colloidal lead-free halide perovskite nanocrystals: Potential for anti-counterfeiting applications. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 6594–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Niu, G.; Yao, L.; Fu, Y.; Gao, L.; Dong, Q.; et al. Efficient and stable emission of warm-white light from lead-free halide double perovskites. Nature 2018, 563, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, W.M.A.; Dirksen, G.J.; Stufkens, D.J. Infrared and raman spectra of the elpasolites Cs2NaSbCl6 and Cs2NaBiCl6: Evidence for a pseudo Jahn-Teller distorted ground state. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1990, 51, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutinaud, P. Revisiting Duffy’s model for Sb3+ and Bi3+ in double halide perovskites: Emergence of a descriptor for machine learning. Opt. Mater. X 2021, 11, 100082. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Mao, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Han, K.; Yang, B. Boosting the self-trapped exciton emission in Cs2NaYCl6 double perovskite single crystals and nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 8613–8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Meng, L.; Yao, H.; Chen, Q.; Sheng, S.; Xiao, J. Realizing high quantum yield green emission of Sb3+, Er3+ co-doped Cs2NaYCl6 via efficient energy transfer. Mater. Lett. 2025, 385, 138208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, V.; Cha, P.-R.; Lee, N. Cs2NaGdCl6:Tb3+─a highly luminescent rare-earth double perovskite scintillator for low-dose X-ray detection and imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 19068–19080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, R.; Zhang, L.; Xue, Y.; Ke, B.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, D.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zou, B. Highly efficient blue emission from self-trapped excitons in stable Sb3+-doped Cs2NaInCl6 double perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroyuk, O.; Raievska, O.; Hauch, J.; Brabec, C.J. Doping/alloying pathways to lead-free halide perovskites with ultimate photoluminescence quantum yields. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202212668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, E.; Yuan, X.; Tang, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Liao, X.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, K.; et al. Eu3+, Tb3+ doping induced tunable luminescence of Cs2AgInCl6 double perovskite nanocrystals and its mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 609, 155472. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, D.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, D.; Sun, S.; Lu, P.; Lu, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Halide double perovskite nanocrystals doped with rare-earth ions for multifunctional applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Dong, B.; Zhou, D.; Bai, X.; Song, H. Multicolor emission from lanthanide ions doped lead-free Cs3Sb2Cl9 perovskite nanocrystals. J. Rare Earths 2024, 42, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhai, Y.; Guan, D.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Fang, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. Tunable multicolor-emission in Eu3+ and Tb3+ codoped Cs2NaInCl6:Sb3+ double perovskite nanocrystals and its dual-model anti-counterfeiting and temperature-sensing applications. J. Lumin. 2024, 274, 120672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Peng, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, L.; Jin, X.; Bai, J.; Li, Q. Incorporating Sb (III) and Bi (III) ions into Cs2AgNaInCl6 perovskite toward efficient white-light emission with high color rendering index. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 155510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, H.; Fu, X.; Yue, H.; Li, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H. Rare earth-based Cs2NaRECl6 (RE = Tb, Eu) halide double perovskite nanocrystals with multicolor emissions for anticounterfeiting and LED applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 11778–11784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, X.; Zou, B.; Zeng, R. Effective energy transfer boosts emission of rare-earth double perovskites: The bridge role of Sb (III) doping. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 7108–7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balitskii, O.; Kagabo, W.; Radovanovic, P.V. Selective Excitation of Lanthanide Co-Dopants in Colloidal Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals as a Multilevel Anti-Counterfeiting Approach. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241838

Balitskii O, Kagabo W, Radovanovic PV. Selective Excitation of Lanthanide Co-Dopants in Colloidal Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals as a Multilevel Anti-Counterfeiting Approach. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241838

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalitskii, Olexiy, Wilson Kagabo, and Pavle V. Radovanovic. 2025. "Selective Excitation of Lanthanide Co-Dopants in Colloidal Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals as a Multilevel Anti-Counterfeiting Approach" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241838

APA StyleBalitskii, O., Kagabo, W., & Radovanovic, P. V. (2025). Selective Excitation of Lanthanide Co-Dopants in Colloidal Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals as a Multilevel Anti-Counterfeiting Approach. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241838