Abstract

Storytelling content is where the facts are conveyed by emotion and that make people more engaged and want to take action or change their surroundings. Stories fascinate people and can easily be remembered compared to the facts alone. The much-hyped feature “stories” of Instagram, a trendy social media platform, has become a game-changer for influencer marketing. The present study extends reactance theory in the context of Instagram’s millennial users. Previous researchers have tested the effectiveness of the stories feature of this particular social media platform. Therefore, in line with the earlier studies, we propose a sequential mediation model that investigates the effect of storytelling content (made by Instagram Influencers) on audience engagement using two sequential mediation mechanisms of relatability and trust. Data were obtained using a cross-sectional study design from 273 millennial users of Instagram. Our results justify the direct and indirect hypothesized relationship through Process Macros. We found that relatability and trust play a significant role in building a strong relationship between storytelling content and audience engagement. Ultimately, the research findings suggest that professionals should be more creative while making the content on Instagram to engage the millennial market. Moreover, this research has tried to fill the gap in the literature on Instagram “stories” as an advertising platform.

1. Introduction

Individuals spend more of their time on Instagram compared to other social media platforms [1]. Instagram is one of the fastest-growing social media networks where users share life experiences in videos or still posts. The “stories” feature launched in 2016 has gained significant popularity. That allows the digital influencers or users to upload photos and videos and do live talks with the audience, which remains for 24 h only [2]. However, the academic research on this subject, particularly studies in digital storytelling, is limited [3]. Due to Instagram, influencer marketing has been growing by leaps and bounds in the past few years. For every dollar businesses spend on this field, they generate more than USD 5 in profits, and 59% of marketers said they intended to expand their influencer budget next year [4].

Digital influencers are now considered more credible than traditional media [5]. The new “stories” feature helps an influencer communicate with their audience by making a short clip of their work and updating them about their daily routine. The results of previous studies have revealed that the video ads presented on social media have influenced the consumer’s attitude towards the ad, and Instagram stories have higher ad effectiveness compared to still posts [2]. Keeping this contention in mind, the primary aim of this research is to develop the mechanism connecting the storytelling content of an influencer and the audience’s engagement with the storytelling content.

Trust is essential in developing relations with someone, as it improves efficiency, increases flexibility, and helps in a long-term relationship between the two parties [6,7]. According to the model presented by Morgan and Hunt (1994), the interaction between the seller and the buyer influences trust due to shared values. The previous research shows that communication through stories enables the customer to engage and connect with the salesperson [8]. Thus, this study examines trust’s role in storytelling content and audience engagement.

The researchers [9] suggested five main antecedents of trust, but relatability was not one of them. Relatability is a non-linguistic concept [10]. The self-determination theory proposes that humans have three basic fundamental and universal psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (i.e., relatability), that help humans grow and their optimal functioning [11]. There is a fundamental need for belongingness in people [12]. This study also investigates the mediating role of relatability between storytelling content and audience engagement.

Based on previous research, such as reactance theory, we propose that Instagram users may have increased motivation to process ephemeral content (i.e., storytelling content) that allows them to interact with the influencer freely, resulting in more engagement. Thus, this study examines the impact of storytelling content created by Instagram influencers on audience engagement, explicitly focusing on the millennial market. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to empirically examine the relationship between storytelling content and audience engagement with the presence of two mediators; relatability and trust. This study will assist marketers interested in increasing their horizons to draw the consumers’ attention toward influencer marketing.

This paper is structured as follows. First, the existing literature is reviewed. The main effect hypothesis of storytelling content influences audience engagement and relatability and the mediating role of relatability and trust are deduced. Furthermore, the data collection process is discussed. Third, factor analysis, correlation analysis, and regression analysis are conducted on the data to test the research hypotheses. Fourth, based on the results of the empirical test, the contribution is discussed in the domains of influencer marketing and helps the social media influencers understand how the millennial segment can be reached more effectively, states the study’s shortcomings, and provides practical implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Influencers

Social media influencers are those people who have built a handsome social network of people following them on their social media accounts [13]. They are seen as trusted tastemakers and are approached by different brands to endorse their products. They also build their following by engaging the audience in their daily routine. We all know that traditional marketing has been pushed back due to several factors; more importance has recently been given to digital influencers due to their higher credibility and authenticity [14]. Additionally, digital influencers are more affordable, and their reach is tremendous. Previous studies show that the amount of followers an influencer has on Instagram affects consumers’ attitudes towards them [15]. So, it will be correct to say that we as users rely more on digital influencers because we know them more than any celebrity.

2.2. Emergence of Influencer Marketing

It has been observed in the world of consumer behavior and marketing literature that electronic word of mouth or the information one obtains from someone who has personally used a product has a more substantial impact on consumer decision-making compared to traditional marketing [16]. One tends to buy a product that is being recommended by a relative or someone close to them. The power of eWOM has been accelerated by the internet. Through social media platforms like Instagram, people started showing their daily routines to their followers through the help of feature “stories” introduced by Instagram in 2016. Snapchat, another social media platform, initially started this. Then, the ordinary people felt they could influence their followers by posting a story of the products they were using or how they behaved. Hence, their social media activities could affect the attitudes and behaviors of their followers [17]. That is how they became digital influencers and how influencer marketing started. Through vlogging, blogging, and short content, they interact with their followers and give insights into their personal lives. Unlike celebrities, influencers are thought to be more reachable, relatable, and believable [10]. Studies have shown that one in every five Instagram accounts reacted to the introduction of the “stories” feature in 2017. Instagram stories have surpassed Snapchat’s 150 million DAUs in 8 months, reaching almost 500 million daily users [18].

2.3. The Feature “Stories” on Instagram

In influencer marketing, feature “stories” has significantly boosted digital influencers’ followers. So this section explains what this feature is, how it works, and how it has helped the influencers increase their followers. Instagram influencers or any Instagram user put up a story as a video or a still post on their account, which stays for 24 h. The followers can see the story and interact with the person who has posted it. Users can add different colors to the videos they post, and the communication can be text-based too [19]. The feature right after 2016 became so popular that whatever happened, people would say, “Put it in your story”. We all know that we are associated with different stories ever since the day we were born. Any content created as a story helps us understand things more clearly. So, these digital influencers make content in the form of a story, share it on their account, and sometimes respond to queries of their followers. The content can be advice, opinions, experiences, photos, videos, etc. However, posting personal videos on this platform helps the followers relate to the Instagram influencer. They are approachable as well as relatable.

2.4. Storytelling Content

Storytelling has been a part of everyone’s lives for ages [20]. Storytelling content (STC) is defined as “the facts conveyed by emotion that make people more engaged and want to take action or change their surroundings” [21]. Storytelling always has a beginning, a middle, and an ending plot (Escalas, 2004). The feature “stories” of Instagram, introduced in 2016, is now being used as a marketing tool. Instagram influencers make different videos and put them on their “stories” to engage them. Initially, the researcher [22] came up with the circle of trust concerning digital storytelling, where he highlighted that storytelling gives an in-the-moment experience to the audience. Lambert has also worked with many communities and organizations to create story-based programs worldwide since the 1990s. Lambert’s publications have popularized that digital storytelling (DST) is about making short video clips to produce personal stories [23]. The content shown in a story form is pleasurable for the audience because they enjoy it as a protagonist and the audience [24]. Based on the reactance theory (Brehm, 1966), users’ reaction to video storytelling content is more engaging than static posts. Likewise, researchers [25] also referred to Brehm’s theory as part of their study on Instagram content. One of the earliest supporters of applying digital storytelling was Gubrim [23]. The researcher in [26] referred to Lambert’s work, but his focus was more on photovoice in storytelling.

2.5. Audience Engagement and Storytelling Content

Audience engagement refers to how the audience faces emotional, cognitive, or affective experiences with media content [27]; this phenomenon can result in higher interaction with the content or more news consumption [28]. Social media influencers are the opinion leaders who communicate with a specific audience’s social networks following them [13]. The main objective is to increase the number of followers by making some engaging content for their blog. According to previous studies, the micro-influencers with less than ten thousand followers on Instagram are thought to attain a more desirable form of engagement compared to macro-influencers, the reason being having fewer followers and a higher interaction rate resulting in a higher conversion rate [29]. In our study, we have taken audience engagement as a psychological state. Prior studies explained how a visual interaction could result in higher audience engagement. Additionally, digital storytelling can increase audience engagement [30].

The proposed theory of audience engagement [31] states that a user’s engagement is a multidimensional phenomenon with emotional and behavioral dimensions. The users interpret the news and invest their energies in relating to the knowledge given. The degree of involvement with the news may vary from audience to audience; some may absorb the story, some may interact with the news, or some may participate in it [27]. Decades ago, it was observed that society now depends more on visual images [32]. Previous research shows that visual communication is becoming a dominant communication method [33].

The ‘Narrative Paradigm’ positioned storytelling as the foundational form of human communication [34]. The researcher further argued that narrative (i.e., storytelling content) is wired into the human psyche. The narrative can be videos or images [35]. A story nowadays is produced to engage and attract the audience in many revolutionary ways [36]. Due to the rapid increase in the types of content, the biggest challenge is keeping the audience engaged [36]. Drawing on the reactance theory [37]. We propose that storytelling content will likely help the audience engage with the brief content. Hence, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1

. Storytelling content has a positive influence on audience engagement.

2.6. Storytelling Content and Relatability

In recent times, the new “buzzword” for social marketing is ‘relatability’, a non-linguistic concept [10]. Relatability is a situation where an ordinary person might see themself reflected [38]. There is a fundamental need for a sense of belonging in people [39]. The self-determination theory proposes that humans have three basic fundamental and universal psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (i.e., relatability) that helps humans grow and optimal functioning [11]. According to a researcher [40], digital celebrity groups, such as vloggers, bloggers, and ‘Instafamous’ personalities, appeal to common reference groups. A group of people is defined as a reference group that shapes the values and attitudes of an individual as a reference and helps the consumers make their purchase decisions [41]. A report on Forbes regarding influencers stated that relatability had become a critical factor in making an influencer successful [42]. Influencers update their private lives on Instagram and share their personal opinions [43,44]. This kind of communication makes the viewers more open to influencers.

The content displayed by the social media influencers is preferred more than their advertisements as the content is unbiased [45]. The content is considered relatable if easily understood and jargon-free [45]. Until the source (i.e., content) is relevant, there stays a bond between a source provider and the viewer [46]. According to researchers [13,47], a constant update of private life is the central aspect of relatability. Due to the rapid increase in the types of content produced, the biggest challenge is keeping the audience engaged [36]. Through storytelling, relationships are built between the participants (Kim, 2013). The audience not just sees the story but interprets it according to their prior knowledge, personality, and demographics [48].

According to [49], generation Z has an attention span of 8 s towards any content, so it must be very relatable to them to keep them hooked. Additionally, the sense of narrative (storytelling content) has a very high level of interactivity [50]. Based on the reactance theory, we propose that users feel more related to the ephemeral content, allowing them to freely interact with the influencer and the storytelling content they make. Therefore, it is not surprising that we identified relatability as a phenomenon that is an antecedent of storytelling content. Hence, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2.

Storytelling content has a positive impact on relatability.

2.7. Storytelling Content and Audience Engagement: Relatability as a Mediator

Based on the discussion, we presume that the relatability of an influencer mediates the relationship between storytelling content and audience engagement. Hypothesis 2 proposes a positive relationship between storytelling content and relatability, whereas hypothesis 1 proposes an influence of storytelling content on the audience. Mutually these two hypotheses contribute to developing a model in which storytelling content indirectly augments audience engagement with the help of relatability, which works as a mediator in this model. It is predicted that a feeling of relatability with an influencer will help mediate the relationship between storytelling content and audience engagement.

A man is known to be a ‘storytelling animal’ [51]. The human experience becomes meaningful [52]. The narrative spread on Instagram consists of short stories or photos [53]. Previous studies show that sharing experiences affects people’s beliefs, attitudes, and behavior [54]. Researchers have linked the stories to persuasion [55]. The shared stories about particular things or events are a collective source of knowledge and information [55]. Stories (i.e., storytelling content) build a potential sharing network amongst the individuals. Storytelling content works for a brand to help build awareness, empathy, comprehension, recall, and recognition and provides meaning [56]. Understanding how storytelling works in marketing is essential to understanding how the audience processes information in a story format. Past studies suggest that audiences think in narrative rather than argumentative terms [57]. Given previous research, it can be argued that the execution-style of content in the form of a story may bring out more favorable changes in the attitude of the audience.

Following the same approach as the context, we can say that storytelling content creates a connection between the source and the listener. According to researcher [55], the narratives of Instagram that are turned into stories make a memorable experience for the audience; the word memorable here means storing, keeping, and recalling the information provided in the story. He further added that this information is then shared with other individuals. So we can say that this way of representing the content in a story helps the audience relate themselves to the influencer. Based on this theoretical grounding, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Relatability plays a mediating role between storytelling content and audience engagement.

2.8. Relatability and Trust

Trust refers to a general expectation and belief that most others have warm intentions and can also be relied upon [58]. Trust has been seen in many dimensions of prosocial behavior, including civic engagement, collaboration, and volunteering [59]. The influencers need to develop a sense of trust with their followers in influencer marketing. A brand message through an influencer is more effective than a message directly given by a brand [13,47]. Trustworthiness has previously been proved to affect brand equity [60] significantly. Any consumer, online or offline, wants to develop trust with their potential dealer first [61]. A previous study found that if consumers do not find trustworthy content in an online store, they will not consider it [59]. Instagram influencers now have started to try the products on themselves first, and during that, they make live videos of it. This visual depiction of the product helps in gaining trust. We know that the user’s attitude towards the content changes according to the trust he/she has in the source [62]. An influencer’s expertise and trustworthiness have been proved to influence brand equity [60]. Trustworthiness is closely associated with honesty, which means if the follower is confident enough in the influencer [63,64,65]. Trust is essential in relations with someone, as it improves efficiency, increases flexibility, and helps long-term relationships between the two parties [6,7]. Based on the above theoretical grounding, we suggest that feeling related to the influencer will build more trust between the influencer and its audience. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4.

Relatability is positively associated with trust.

2.9. Storytelling Content and Audience Engagement: Trust as a Mediator

According to Henry Jenkins, an American scholar, storytelling is a new way of presenting stories using different methods, media, and viewpoints [66]. In prior studies [67], most of the content a human sees is stored in their consciousness, mainly associated with short stories. The emotional areas of a human body activate when something verbally is described [68]. Whereas, the content created visually grabs more attention [66]. The consumers (i.e., audience in our case) expect a company or the source to tell clear and concise information regarding a brand; they also expect that it should be honest [66]. Previous research on the effectiveness of storytelling has shown that narrative advertising generates higher awareness, higher commitment to the content, and higher purchase intention [69,70,71]. While developing the storytelling cycle of trust, it was suggested that the storyteller should genuinely represent the stakeholders [72]. Initially, Lambert (2006) came up with the circle of trust concerning digital storytelling, where he highlighted that storytelling gives an in-the-moment experience to the audience.

Further, he added that a story circle provides a safe space for people. Trust between two parties epitomizes the overall feelings, attitudes, and evaluations of each individual involved in the relationship [73]. The prior study suggested that customer engagement helps build a relationship of trust and commitment between a seller and the buyer [73]. There will be more customer (i.e., audience) engagement if there is higher attachment. Thus, based on this, it is anticipated that with trust between two parties (an influencer and the audience), the relationship between storytelling content and audience engagement is mediated. This relationship has been developed through the help of commitment trust theory [74] which states that trust plays a vital role in an ongoing relationship as it develops a cooperative environment between the two parties (influencer and Instagram user). So, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5.

Trust mediates between storytelling content and audience engagement.

2.10. Trust and Audience Engagement

The audience is increasingly skeptical about advertising and other communications methods [75]. Influencers now look for ways that can engage the maximum audience. Content marketing fosters engagement, brand awareness, and trust [76]. Previous studies highlighted that engagement was initially the concept of human resource management that was used to enhance employee loyalty [77]. However, researchers have now started to take this concept of customer (i.e., audience) engagement into the marketing context [73]. A study [78] stated that trust could be an antecedent of consumer (i.e., audience) engagement. The social exchange theory explains that a trust relationship develops over time when two parties exchange favorable experiences [77,78]. Concerning marketing literature, it has been proposed that the positive interactions between two parties build trust [79,80]. Prior studies have found that trust is an essential mediator between loyalty and customer engagement in hospitality [79]. In earlier studies, we have seen that trust has played a significant role in representing consumer engagement in many different fields. Still, we, in the context of influencer marketing, propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6.

Trust is positively associated with audience engagement.

2.11. Storytelling Content and Audience Engagement via Relatability and Trust

According to [81], the psychological connection lets the audience engage with the source, and then they become loyal to the brand/source. Researchers [82] state that one of the purposes of storytelling is to develop trust and engage the customers [83]. The prior study explains that it is essential to integrate customer resources to develop customer (i.e., audience in our case) engagement [84]. Digital platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook, have shown a positive effect on audience engagement due to deeper cognitive processing, interactivity, and the longer attention given by the consumers to the content [85]. The engagement of audiences occurs when a relationship is formed based on commitment and trust [86]. While selling something, there has to be a proper process of developing the message with the stories that show how the brand connects with the consumer in an authentic, relatable, and engaging way [87].

Since millennials have the highest levels of contribution on social media platforms and while creating content, it was suggested that millennials prefer storytelling over the straight-sell method. We presume that through the storytelling content, the audience (millennials) can relate more to the influencer, which helps build the trust between the two parties. Further, it improves audience engagement.

So we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 7.

Relatability and trust mediate between storytelling content and customer engagement.

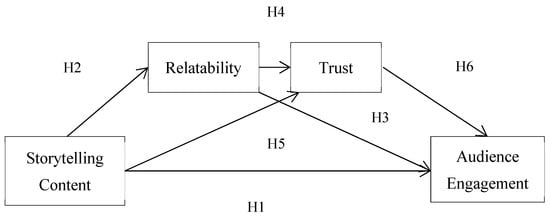

According to [88], the framework is a conceptual model that details the relationship between different theories. This study aimed to analyze the impact of STC on AE via relatability and trust. In this research, there are four variables studied as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Conceptual Definitions of Study Variables

Audience engagement is the dependent variable in our current study. It is defined as “the extent to which the audience faces emotional, cognitive or affective experiences with the media content” [27]. Storytelling content is the independent variable in the present study. It is “the facts conveyed by emotion that make people more engaged and want to take action or change their surroundings” [21]. It can also be referred to as any story containing “a beginning, a middle and an ending plot” [89]. In our study, relatability and trust both play the role of mediators. Relatability links the independent variable (storytelling content) with the dependent variable (audience engagement). Relatability is “the extent to which a person feels that one is connected to others, has caring relationships, and belongs to a community” [90]. Trust is the second mediator in our sequential model, which refers to “a general expectation and belief that most others have warm intentions for you and can also be relied upon [91].

3.2. Participants and Procedure

The questions were developed on a 5-point Likert scale which ranged from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). The questionnaires are more convenient than the interviews (Bryman and Bell, 2015). Hence, a questionnaire was designed and included the items to measure storytelling content, relatability, trust, and audience engagement. We chose closed questions for survey because coding is more accessible than open-ended ones [91]. The unit of analysis was Instagram users born after the 1980s who use Instagram daily. This study was conducted to determine the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable, the storytelling content (X), on audience engagement (Y) via relatability (Mediator 1), and trust (Mediator 2). Then, the time horizon is used in cross-sectional because the data have been collected at one point in time. A cross-sectional study is relatively quick to conduct. y. The unit of analysis was the regular users of Instagram, a social media platform.

Our present study adopts a non-experimental, quantitative, and correlational design to meet the research objectives. For this study, a convenience non-probability sampling technique was used. We recruited 350 millennial Instagram users through direct links. The questionnaires were presented in Google Forms and distributed in some universities. There was no interference from the researcher besides clarifying items for the respondents. The study purpose was also explained to the respondents in the beginning. So, it would be correct to say that the study was utterly non-contrived as the responses were taken in a routine. This study is cross-sectional because the data have been collected at one point in time. Additionally, we can research multiple outcomes at once. The unit of analysis was the regular users of Instagram, a social media platform.

Scholars [92] claim a sampling size should be made before collecting the data. Kline [93] and Field [94] suggested that there should be 10 respondents against each item in the questionnaire (that means; the No. of items in the questionnaire multiplied by 10 respondents from the targeted population). Our survey had 18 items, so the sample size of 180 participants was sufficient. However, we distributed around 350 questionnaires, out of which 273 were completed, and the rest had missing data.

The questionnaire was in English, and all questions were closed questions. The first section comprises personal information, including age, education, and gender. The second section contained 3 items of storytelling content. The third section consisted of 3 items related to relatability. The third section also included 4 items. Furthermore, the last section covered 3 items on audience engagement.

A questionnaire is defined as “a formalized set of questions for obtaining information from respondents” [95]. The primary data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire from Instagram users aged below 40. The questionnaires were made in Google Forms and Microsoft Word and distributed through social media sites, such as Instagram and Facebook. The questionnaires were also distributed in person too in different colleges. Due to the closed questions, it became easier to code the responses.

As soon as the data were collected, it was input into an Excel sheet. It is important to code the responses [92]. Researcher [95] emphasized that assigning a code to each possible answer is essential. The participants were already told about the objectives of this study, and they was assured that this information would stay confidential and only be used for academic and research purposes.

3.3. Measurement and Scales

3.3.1. Storytelling Content

A five-point scale was employed for measuring storytelling content, which had an internal consistency of 0.76 [96]. In the items, “stories” were replaced by “storytelling content”; for example: “storytelling content caught my attention” and “The storytelling content creates insights/new ideas for me today”. The participants indicated their desire using a five-point Likert scale, with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. The scale is reported in Appendix A

3.3.2. Relatability

A five-item scale was used to measure how relatable users of Instagram feel to storytelling content created by influencers [97]. For example, “I think that constant updates about the influencer’s life on his or her social media channels are important” and “I feel like I know the influencer well.” The scale is reported in Appendix A. The participants indicated their desire using a five-point Likert scale with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. The internal consistency for the measure was 0.71.

3.3.3. Trust

The Trust scale was adopted from researchers [97] and measured with a five-Likert scale. The items included, “I think the influencer shares their honest opinion”, “I trust the influencer’s messages more than one coming directly from a brand.” The scale is reported in Appendix A. The participants indicated their desire using a five-point Likert scale with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. The internal consistency for the me7sure was 0.85.

3.3.4. Audience Engagement

The audience engagement scale was adopted and modified [98,99] and and measured with a five-point Likert scale. For example, “Any storytelling content grabs my attention” and “When interacting with the content, it is difficult to detach myself.” The scale is reported in Appendix A. The participants indicated their desire using a five-point Likert scale with 5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. The internal consistency for the measure was 0.74.

3.3.5. Control Variables

The controlled variable included: gender (female = 1, male = 2), education level (1 = matric/O level, 2 = Intermediate/A level, 3 = Baccalaureate, 4 = Masters and 5= PhD), and age (1 = 15–20 years, 2 = 21–25 years, 3 = 26–30 years, 4 = 31–34, and 5 = 35–40 years). Since the questionnaires were to be filled by the millennials, we had to ensure that age was controlled. It was also important to keep gender as a control variable because our study wanted to know if the responses of males were different from the females. Lastly, collecting education data was important as each educational level exhibits different attitudes and behaviors.

4. Results

This section covers the results, statistical analyses, interpretations, and explanations of the relationship between study variables. The analysis was conducted on SPSS Statistics (version 24.0 IBM® Corp). Both descriptive and inferential statistics are used to explain the findings. This study’s main objective was to determine the impact of storytelling content (IV) on audience engagement (DV). To mediate these two variables, we anticipated that relatability and trust could play a role in influencing our dependent and independent variables. Hence, there are seven main findings of the present research.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Participants’ Characteristics

A total of 273 millennial Instagram users participated in the survey. In total, 300 participants took part in the survey, but 27 of the responses had some missing data. The findings demonstrated that the majority of the respondents were females, with a percentage of 91.6%. In contrast, approximately one-eighth of the participants were males (8.4%). About 49.5% of them were aged between 21 and 25; 13.6% of the participants were aged between 15 and 20; 17.6% came were aged between 26 and 30; and 13.2% of the respondents were between the age of 31 and 34. The majority of the participants were graduates, i.e., 48.4%.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Variables

The five-point Likert scale was used to assess the variables. The findings show that all the studied variables have a minimum range of responses, i.e., between 1.00 to 1.6 whereas the maximum value is 5.00. The mean value ranged from 3.24 to 3.68, while the standard deviations of responses lie between 0.69 and 0.83. Storytelling content had a mean = 3.68 and SD = 0.69, implying that Instagram users do find storytelling content engaging. Relatability items resulted in mean = 3.33 and SD = 0.73, proposing that study participants feel more relatable with the content and eventually gain trust and become more engaged. Furthermore, Trust items produced mean = 3.24 and SD = 0.83, which shows that the users trust the storytelling content and become engaged with the content shown. Finally, Audience Engagement items reported mean = 3.46 and SD = 0.71, exhibiting that users become more invested due to the storytelling content produced.

4.3. Measurement Validation

To check internal consistency and reliability between items of each construct, we computed Cronbach’s alpha values. An alpha value is considered “very good” if it is near 0.80, whereas a 0.70 is considered adequate [93]. The results have shown that all the variables have internal consistency of 71% to 85%. Hence, there’s no reliability issue in our data.

Table 1 shows the reliability test results for the present study, and Cronbach’s α for all variables’ scales has met the threshold value, ranging from 0.71 to 0.85.

Table 1.

Reliability of scales.

4.4. Correlation Matrix

Before testing the hypotheses, a correlation analysis of our study variables was performed. Since all our variables are nominal, the most suitable correlation model for the examination is Spearman’s correlation coefficient, which shows the statistical dependence between the ranking of two variables. This is also known as bivariate correlation. Table 2 displays the mean, standard deviation (SD), Cronbach alpha’s, and correlation values. The results show that items of each variable are positively correlated and support our study hypotheses. The result exhibits that Storytelling Content has a significant and positive relationship with Audience Engagement (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), according to our H1.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviations, and correlations for the study.

Furthermore, Storytelling Content and Relatability results are also positively associated with each other (r = 0.27, p< 0.01), which supports H2. The relationship between Relatability and Trust shows a positive correlation with a significant value of <0.05, and Trust and Audience Engagement have a positive and significant relationship (r = 0.55, p < 0.01). Both these outcomes are in accordance with H3 and H4.

4.5. Exploratory Factor Analysis

EFA and CFA are the tests used to identify variables’ data patterns and factor structure. Before conducting CFA, we ran EFA using SPSS Statistics 24 to see the structure of factors. The Kaiser–Meye–Olkin (KMO) gave a statistical value of 0.85, indicating the appropriateness of the factor analysis for the data. The value of 0.85 confirms that the sample taken was enough for the factor analysis. The acceptable value of KMO is 0.6 and above (Kaiser, 1970, 1974). The Barlett’s test of sphericity shows a significance value < 0.05, which indicates that the correlations were of a large number for EFA. The commonalities explain the amount of variance a variable has with all other study variables. All the communalities range from 0.60 to 0.70, confirming that each item shared some common variance with other items (see Table 3). All the above indices supported the inclusion of 13 items in factor analysis.

Table 3.

Rotated component matrix.

The initial Eigenvalues Results showed that the first of the four factors had an Eigenvalue above 1, and they account for 38.38%, 11.54%, 10.72%, and 8.02% of the total variance, respectively. The 5th onwards until the 13th component had eigenvalue below one, and all explained variance less than 5%. All the items in this analysis had fair loadings above the absolute value of 0.60. The first of the 4 items were loaded on the first factor, which represents Trust; the following 3 items were loaded on the second factor, which means Storytelling Content; then the following 3 items were loaded on the third factor, which represents Audience Engagement; and the last 3 items were loaded on the fourth factor, which represents Relatability. The results demonstrate that each item is linked to the expected factor structure. Table 3 shows the factor loading matrix for the final solution.

4.6. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed on all the items. The overall CFA measurement showed a satisfactory model fit to the data. At first, the four-factor measurement model was examined. To fulfill this purpose, we drew all the items related to the four study variables in AMOS 24 and then allowed the items to correlate freely to their respective factors. The results of Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) were all >0.90; TLI = 0.94, IFI = 0.96, and CFI = 0.96, whereas AGFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.056; all of these indices fall within a satisfactory limit.

Furthermore, construct validity was evaluated with the help of convergent and discriminant validity. For convergent validity factor loadings, composite reliability and average variance need to be assessed. Table 4 shows the factor loadings.

Table 4.

Factor loadings.

The results indicated that all the factor loadings for all the variables were greater than 0.60. Moreover, all values have CR greater than 0.7. Researchers [100] argue that AVE is often too strict, and reliability alone can be established through CR. Therefore, the results are fulfilling the criteria for convergent validity.

Finally, discriminant validity was also assessed by the Fornell and Larcker approach [101], which declared that the square root of AVE of each construct should be greater than the correlations of this construct to all other constructs. Table 5 demonstrates the square root of AVE in bold and diagonal elements.

Table 5.

Overall reliability and validity of the constructs.

4.7. Hypotheses Testing

The study hypotheses were tested through a sequential mediation model. We used SPSS Process (model 6). Bootstrap was performed for resampling, which was 5000 in number. The total effect of STC on AE was positive and significant (β = 0.46, t = 8.78, p < 0.001), providing support for our hypothesis 1, as shown in Table 6. The results of model 1 indicate that relatability and storytelling content are significantly related (β = 0.25, p = 0.000, LLCI = 0.146, ULCI = 0.357). In the second model, the impact of two predictors was seen as significant on trust. The significance value for both was p = 0.000, which shows that the relationships were significant, as shown in Table 6. Finally, Table 7 shows that all the indirect paths are also significant as LLCI and ULCI do not contain zero. Hence, all the hypotheses are empirically supported in this study (see Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 6.

Results of sequential mediation regressing relatability and trust as mediation.

Table 7.

Indirect effect of X(STC) on Y(AE).

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

As social media progresses and almost everything has become digital, millennials depend on social media platforms, such as Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, etc. Before buying anything for themselves, they see the views given by digital influencers on their Instagram blogs. Some influencers post an advertisement in a still post, while others make content in the form of a story. This study’s main objective was to determine the impact of storytelling content (IV) on audience engagement (DV). To mediate these two variables, we anticipated that relatability and trust could play a role in influencing our dependent and independent variables. Hence, there are seven main findings of the present research. The discussion of our results is as follows:

In Hypothesis 1, our results positively influenced our dependent (Audience Engagement) and independent variables (Storytelling Content). Storytelling Content is an exclusively human activity that is often used to stimulate memory and imagination in people [102]. Consequently, anything shared in the form of a story simplifies the complexity of the content [103], resulting in a more engaged audience. Hypothesis 2 disclosed that Storytelling Content has a positive impact on Relatability. Previous studies have explained that digital storytelling builds strong consumer relationship experiences [104].

According to [49], generation Z has an 8 s attention span towards any content, so the content must be very relatable to them to experience a positive outcome. Our results show that millennials feel relatable when they see storytelling content. Supporting hypothesis 3, the results indicated that Relatability mediates the relationship between Storytelling Content and Audience Engagement. The content is considered relatable if it is easily understood and jargon-free [45]. When the source (i.e., Storytelling Content) is relevant, there is a bond between a source provider and the viewer [46].

The result of hypothesis 4 disclosed that Relatability positively impacts Trust. It was found that millennials are prone to value someone else’s opinion who is more credible [105]. It was found that this generation pushes their boundaries to seek a connection with someone. So the results align with the previous findings linking Relatability and Trust positively. In Hypothesis 5, the results demonstrated that Trust mediates the relationship between Storytelling Content and Audience Engagement. According to commitment–trust theory, companies or brands hire influencers to promote their products to build positive relationships of trust by fostering customer engagement [76]. Moreover, content in the form of a story creates a positive consumer attitude [106]. Therefore, trust can be regarded as the mediator between the independent and dependent variables.

In line with Hypothesis 6, our current study found a positive influence of Trust on Audience Engagement. The results suggested that if there is a relationship of trust between the influencer and the Instagram user (millennial), they (the audience) will be more engaged in the content. Lastly, our findings favor the serial mediation model (hypothesis 7), showing that the indirect impact of Storytelling Content on Audience Engagement through Relatability and Trust exists. Storytelling Content is more relatable and develops Trust between the influencer and the follower, resulting in more Audience Engagement.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This research contributes to the academic field by adding a newer concept to the current work. Influencer marketing is currently a much-hyped concept [107]. Previous research has shown that Facebook wall posts are less effective than Instagram stories’ in promoting something [2]. Very few studies have explored the impact of storytelling content on the audience with a target market of millennials only. This study investigates whether storytelling content is an essential antecedent of audience engagement to address this gap. This study is among the first to explore this relationship. Hence, our study broadens the research on audience engagement and storytelling content.

Our study shows that storytelling content is closely associated with relatability, trust, and audience engagement. So the influencers and the brands should make sure that the content they are making for the consumers should be a story because this helps the millennials relate to the content and the influencer and builds a trust relationship, which results in a higher audience engagement. Our study extends the existing audience engagement literature by including relatability and trust as essential conditions. Previous studies have seen the aspects of audience engagement with an entertainment piece [108]. In our research, audience engagement has been seen from a different dimension.

Our study also extends the existing storytelling literature by including relatability and trust as mediators in the model to impact audience engagement. Drawing on our findings, it can be deduced that relatability and trust between the influencers and their followers can increase audience engagement. This suggests that the strong positive association between storytelling content and audience engagement through the mediators, i.e., relatability and trust, can positively change influencer marketing. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first one to find the mentioned relationships empirically.

5.3. Practical Implications

Since the first online ad appeared, online advertising has taken many steps forward to more interactive and new formats while considering individuals’ preferences. A considerable number of advertising options have declined, and social media platforms have been booming. In this context, our study can help firms, advertisers, digital influencers, and community managers succeed on Instagram’s most important social media platform.

First, our results show that storytelling content on Instagram helps engage with the Instagram audience. Professionals should record that users exposed to the content presented as a story tend to generate a positive outcome from the audience. The ephemeral, interactive, and dynamic Instagram storytelling content could be very effective when looking for sales, or some issue needs to be addressed. Our studies show that users find the STC made by the influencers attractive hence it can help achieve the objectives of the influencers and the brands/firms. Previous research has shown that Instagram stories are more popular than Facebook’s wall posts [2] so we can say that our study is in line with the previous findings. Therefore, when planning to promote their products or services, professionals should remember that influencers’ content is more relatable and is trusted by the audience than by promoting it through TV ads and celebrities. Our study also highlights the power of influencer marketing as an inspirational and informational source for marketing planning. Celebrity endorsement can still be a reliable strategy to promote products and services. However, to reach out to millennials who prefer to engage with the brand on Instagram, the digital influencers should start working more on their stories’ content.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Studies

Regardless of the novel contribution of this current study, it has a few limitations that open up new paths for future research. Firstly, our research design does not control a specific type of storytelling content on Instagram. Although the results showed that this type of content is thought to be relatable to the millennial, if a few more dimensions were added, the results could have been affected by additional factors, such as focusing on the types of storytelling content. Furthermore, research should be replicated in lab settings and with a probabilistic sample design. Second, we have just studied the Instagram platform, the most popular social media platform among millennials. Adding more platforms could help corroborate our hypotheses in different circumstances. Undoubtedly, further measures should be integrated to understand better which platform is most effective when an advertiser has to advertise something or when an influencer has to make content. Thirdly, more detailed research can be conducted into Instagram users’ profile characteristics, which might help advertisers examine the demographic factors presented in this study and other personal factors. Fourth, these are not generalized results as most of the respondents were females unintentionally. Future research can keep a quote for both males and females to eliminate response biases. The present study may be subject to common method biases as data were collected at one point in time. Future studies may use the time-lagged study design to elevate the common method biases. Finally, a longitudinal study can be designed to examine the evolution of storytelling content on Instagram, which might help researchers and academics better understand how changes in the content can affect the audience’s engagement.

5.5. Conclusions

This research concludes that if the content (an advertisement, self-promotion, paid promotion, etc.) is created in the form of a story with the help of the “stories” feature of Instagram, the millennial audience will be more engaged. Any issue, any brand, any sort of awareness, topics such as human rights and women empowerment, sustainability issues, green marketing, etc., can be promoted through storytelling content made by Instagram influencers. Our results confirm that the more dynamic social media formats (i.e., Instagram stories) enhance users’ attitudes towards that content. This result is consistent with the previous studies that associate creative strategies with audience engagement, precisely dynamic visual messaging. In addition, this outcome is in line with our assumption about relatability and trust factors, which helps users to show favorable attitudes towards the content. Our research found that STC positively impacts relatability and trust, which means that the millennial user feels more relatable to the content made through the “stories” feature, which helps them to trust. We all know that influencer marketing has evolved in the past few years. So, our empirical findings will help develop this field more. STC can offer a competitive advantage in influencer marketing, primarily as the concern has grown globally for sustainable development in society, economies, and the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and G.A.; methodology, M.A. and G.A.; software, M.A.; validation, G.A., A.A. and M.F.I.; formal analysis, M.A.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A. and G.A.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, G.A., A.A. and M.F.I.; visualization, A.A. and M.F.I.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, M.A., G.A., A.A. and M.F.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Questionnaire |

| Storytelling Content |

| Storytelling content catches my attention |

| I believe I will remember some of these content |

| The storytelling content created new ideas for me |

| Relatability |

| I think it is important that the influencer interacts with their followers |

| I think the influencer’s opinions are similar to mine |

| I feel like I know the influencer well |

| Trust |

| I trust the influencer’s opinion |

| I think the influencer shares his/her honest opinion |

| I trust the influencer’s knowledge about the product/service he/she endorses |

| I trust the influencer’s messages more than one coming from a brand |

| Audience Engagement |

| Any storytelling content grabs my attention |

| In general, I thoroughly enjoy exchanging ideas with other users |

| When interacting with the content, it is difficult for me to detach myself |

References

- Laor, T. My social network: Group differences in frequency of use, active use, and interactive use on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Cenjor, I.; Pérez-Rueda, A. Instagram stories versus Facebook wall: An advertising effectiveness analysis. Span. J. Mark. 2019, 3, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Bryant, K. Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoson. Available online: https://www.tomoson.com/blog/influencer-marketing-study/ (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Shareef, M.A.; Mukerji, B.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Islam, R. Social media marketing: Comparative effect of advertisement sources. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.C.; Dhillon, G.S. Interpreting Dimensions of Consumer Trust in E-Commerce. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2003, 4, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B.; Six, F. The Trust Process in Organizations: Empirical Studies of the Determinants and the Process of Trust Development; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, L.D. Story-selling: Creating and sharing authentic stories that persuade. J. Adv. Mark. Educ. 2018, 26, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Nath, P. Role of electronic trust in online retailing: A re-examination of the commitment-trust theory. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 1173–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. “Aren’t These Just Young, Rich Women Doing Vain Things Online?”: Influencer Selfies as Subversive Frivolity. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leeflang, P.S.H.; de Vries, L.; Gensler, S. Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quercia, D.; Ellis, J.; Capra, L.; Crowcroft, J. In the mood for being influential on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Social Computing, Boston, MA, USA, 9–11 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Clark, R.A. An analysis of factors affecting fashion opinion leadership and fashion opinion seeking. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2008, 12, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P.S.; Watts, D.J. Influentials, networks, and public opinion formation. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B. Instagram Demographic Statistics: How Many People Use Instagram in 2022? Available online: https://backlinko.com/instagram-users (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Miller, H.J.; Thebault-Spieker, J.; Chang, S.; Johnson, I.; Terveen, L.; Hecht, B. “Blissfully Happy” or “Ready to Fight”: Varying Interpretations of Emoji. In Proceedings of the Tenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cologne, Germany, 17–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herskovitz, S.; Crystal, M. The essential brand persona: Storytelling and branding. J. Bus. Strategy 2010, 31, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickman, R. The four elements of every successful story. Reflect.-Soc. Organ. Learn. 2003, 4, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. Digital Storytelling: Capturing Lives, Creating Community, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.; Sage, M. A narrative review of digital storytelling for social work practice. J. Soc. Work Pr. 2019, 35, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coker, K.K.; Flight, R.L.; Baima, D.M. Skip it or view it: The role of video storytelling in social media marketing. Mark. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Jones, V.K. How Instagram Content Affects Brand Attitudes and Behavior. Fac. Publ. Coll. J. Mass Commun. 2017, 5, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium, A. Digital storytelling: An emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 10, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broersma, M. Audience Engagement. In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies; Vos, T.P., Hanusch, F., Dimitrakopoulou, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté Gauxachs, A.; Micó Sanz, J.L.; Díez Bosch, M. Is the New New Digital Journalism a Type of Activism? An analysis of Jot Down, Gatopardo and The New Yorker. Commun. Soc. 2019, 32, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coss, Y. Micro vs macro influencers: ¿Cuál es el más indicado? Available online: https://blog.digimind.com/es/insight-driven-marketing/micro-vs-macro-influencers-cual-es-el-mas-indicado (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Choo, Y.B.; Abdullah, T.; Nawi, A.M. Digital storytelling vs. Oral storytelling: An analysis of the art of telling stories now and then. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, S.; Ferrer-Conill, R.; Peters, C. Against a theory of audience engagement with news. J. Stud. 2020, 21, 1662–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.C. Sports photographs and sexual difference: Images of women and men in the 1984 and 1988 Olympic games. Sociol. Sport J. 1990, 7, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielson, M. Why Visual Communication Is Taking Over the World. Available online: https://www.gliffy.com/blog/2016/07/27/why-visual-communication-is-taking-over-the-world/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Fisher, W. Narration as human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Commun. Monogr. 1984, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.G.; Romney, M. Life in black and white: Racial framing by sports networks on Instagram. J. Sports Media 2018, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzara, E.; Kotsakis, R.; Tsipas, N.; Vrysis, L.; Dimoulas, C. Machine-Assisted Learning in Highly-Interdisciplinary Media Fields: A Multimedia Guide on Modern Art. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brehm, J.W. A Theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, R. The Scourge of Relatability. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/scourge-relatability (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Leary, M.R.; Baumeister, R.F. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 32, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chahal, M. Marketing Week. Available online: https://www.marketingweek.com/four-trends-that-will-shape-media-in-2016/ (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Leon, G.; Schiffman, K.L. Consumer Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.; Inthorn, S.; Wahl-Jorgensen, K. Citizens or Consumers?: What the Media Tell Us about Political Participation; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, J.; Schramm, H.; Schallhorn, C.; Wynistorf, S. Good guy vs. bad guy: The influence of parasocial interactions with media characters on brand placement effects. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 720–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Hudders, L.; De Jans, S.; De Veirman, M. The value of influencer marketing for business: A bibliometric analysis and managerial implications. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandagiri, V. The impact of influencers from Instagram and Youtube on their. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Moderen Educ. 2018, 4, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Processes of opinion change. Public Opin. Q. 1961, 25, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Coste-Manière, I.; Stankeviciute, R. Can fashion blogs function as a marketing tool to influence consumer behavior? Evidence from Norway. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2013, 4, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Yzer, M.C. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun. Theory 2003, 13, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausby, A. Microsoft Attention Spans Research Report. Available online: https://dl.motamem.org/microsoft-attention-spans-research-report.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Ursu, M.F.; Zsombori, V.; Wyver, J.; Conrad, L.; Kegel, I.C.; Williams, D.L. Interactive documentaries: A Golden Age. Comput. Entertain. 2009, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretchmar, R.S. Sport, fiction, and the stories they tell. J. Philos. Sport. 2017, 44, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, S. Öykü ve Söylem Filmde ve Kurmacada Anlatı Yapıs; Translated by Özgür Yaren; De ki Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.C.; Clark, J.L. Transportation into narrative worlds: Implications for entertainment media influences on tobacco use. Addiction 2013, 108, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, M. Instagram stories from the perspective of narrative transportation theory. Turk. Online J. Des. Art Commun. 2017, 7, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sonnenburg, S. Brand performances in social media. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodside, A.G.; Sood, S.; Miller, K.E. When consumers and brands talk: Storytelling theory and research in psychology and marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 97–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust 1. J. Personal. 1967, 35, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Kou, Y.; Liu, B. Linking self-compassion and prosocial behavior in adolescents: The mediating roles of relatedness and trust. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spry, A.; Pappu, R.; Cornwell, B.T. Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 882–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, B.; Gordon, B. Offline and Online brand trust models: Their Relevance to Social Media. J. Bus. Econ. 2015, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zainal, N.T.A.; Harun, A.; Lily, J. Examining the mediating effect of attitude towards electronic words-of mouth (eWOM) on the relation between the trust in eWOM source and intention to follow eWOM among Malaysian travellers. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seno, D.; Lukas, B.A. The equity effect of product endorsement by celebrities: A conceptual framework from a co-branding perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.M.; Lam, N.H. The effects of celebrity endorsement on customer’s attitude toward brand and purchase intention. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 9, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatwarnicka-Madura, B.; Nowacki, R. Storytelling and its impact on effectiveness of advertising. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Management, Czestochowa, Poland, 7–8 June 2018; p. 694. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, C.H.; Byueong-hyun, M.; Young, K.J. Analysis on Consumer Behavior Model for Storytelling Advertising of High-Tech Products: Focusing on Identification and Empathic Response. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wallentin, M.; Nielsen, A.H.; Vuust, P.; Dohn, A.; Roepstorff, A.; Lund, T.E. Amygdala and heart rate variability responses from listening to emotionally intense parts of a story. NeuroImage 2011, 58, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajdas, M. Storytelling—Nowa koncepcja budowania wizerunku marki w epoce kreatywnej. Współczesne Zarządzanie 2011, 1, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Matilla, A.S. The Role of Narratives in the Advertising of Experiential Services. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyorat, K.; Alden, D.L.; Kim, E.S. Impact of Narrative versus Factual Print Ad Copy on Product Evaluation: The Mediating Role of Ad Message Involvement. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Campbell, M.; Copeland, L.; Craig, P.; Movsisyan, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Evans, R. Adapting interventions to new contexts—The ADAPT guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Consequences of Consumer Engagement in Service Marketing: An Empirical Exploration. J. Glob. Mark. 2019, 32, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, J. Content Not Converting? Start with Your Buyer’s Journey. Available online: https://www.authorityfactory.net/buyer-journey/ (accessed on 3 April 2017).

- Holliman, G.; Rowley, J. Business to Business Digital Content Marketing: Marketers’ Perceptions of Best Practice. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2014, 8, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.; Wang, Y. The role of customer engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. J. Travel Res. 2014, 55, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C.M. Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hapsari, R.; Clemes, M.D.; Dean, D. The impact of service quality, customer engagement and selected marketing constructs on airline passenger loyalty. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2017, 9, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiady, N.D.; Windasari, N.A.; Nita, A. Customer engagement in online social crowdfunding: The influence of storytelling technique on donation performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 38, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linda, D.; Hollebeek, K.; Macky, D. Content Marketing’s Role in Fostering Consumer Engagement, Trust, and Value: Framework, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Nebhinani, N.; Viswanathan, A.; Kirubakaran, R. Atomoxetine for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V. Sustainability as corporate culture of a brand for superior performance. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyne, K. How brands can create a compelling sales proposition through storytelling. J. Brand Strat. 2018, 7, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Saunders, A. Wired for Innovation: How Information Technology is Reshaping the Economy; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, B. Narrative Dynamics: Essays on Time, Plot, Closure, and Frames; Phalen, J., Rabinowitz, P., Eds.; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F.; Riekki, T.J. Autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: A multicultural comparison of the four pathways to meaningful work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koran, J. Preliminary proactive sample size determination for confirmatory factor analysis models. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2016, 49, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, J.E. An Analysis of the Effectiveness of Storytelling with Adult Learners in Supervisory Management. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, WI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, L.; Folkestad, A.; Postnikova, A. Maybe Influencers Are Not Worth The Hype: An Explanatory Study on Influencers’ Characteristics with Perceived Quality and Brand Loyalty. Bachelor’s Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R.A.; Sharma, J. Customer engagement for evaluating customer relationships in hotel industry. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.A. Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Dash, S. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 6th ed.; Dorling Kindersley Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arrigo, F.P.; Robini, E.; Larentis, F.; Camargo, M.E.; Schmiedgen, P.; Garavan, T. Storytelling and innovative behavior: An empirical study in a Brazilian group. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, T.L. The Strategic Use of Stories in Organizational Communication and Learning; ME Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pera, R.; Viglia, G. Exploring how video digital storytelling builds relationship experiences. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Dey, D.K.; Balaji, M.S. Drivers of brand credibility in consumer evaluation of global brands and domestic brands in an emerging market context. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne-Manero, C.; Marzo-Navarro, M. Exploring how influencer and relationship marketing serve corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.; Sheena, K. Impact of Influencers in Consumer Decision Process: The Fashion Industry. SCMS J. Indian Manag. 2017, 14, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; Craig-Lees, M. Audience Engagement and its Effects on Product Placement Recognition. J. Promot. Manag. 2010, 16, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).