1. A Medieval Synagogue in Portugal

Tomar is small city in the Portugal mainland. Tourists can visit the Convent of Christ, an extensive, well-renovated medieval castle and monastery on a hilltop that is thought to have been built by the Order of the Temple, a celebrated Christian military order banned by the Pope in the fourteenth century. This national monument and its status as a UNESCO heritage site attract as many as 300,000 tourists annually because of its diverse architectural styles that range from the late Middle Ages to the eighteenth century.

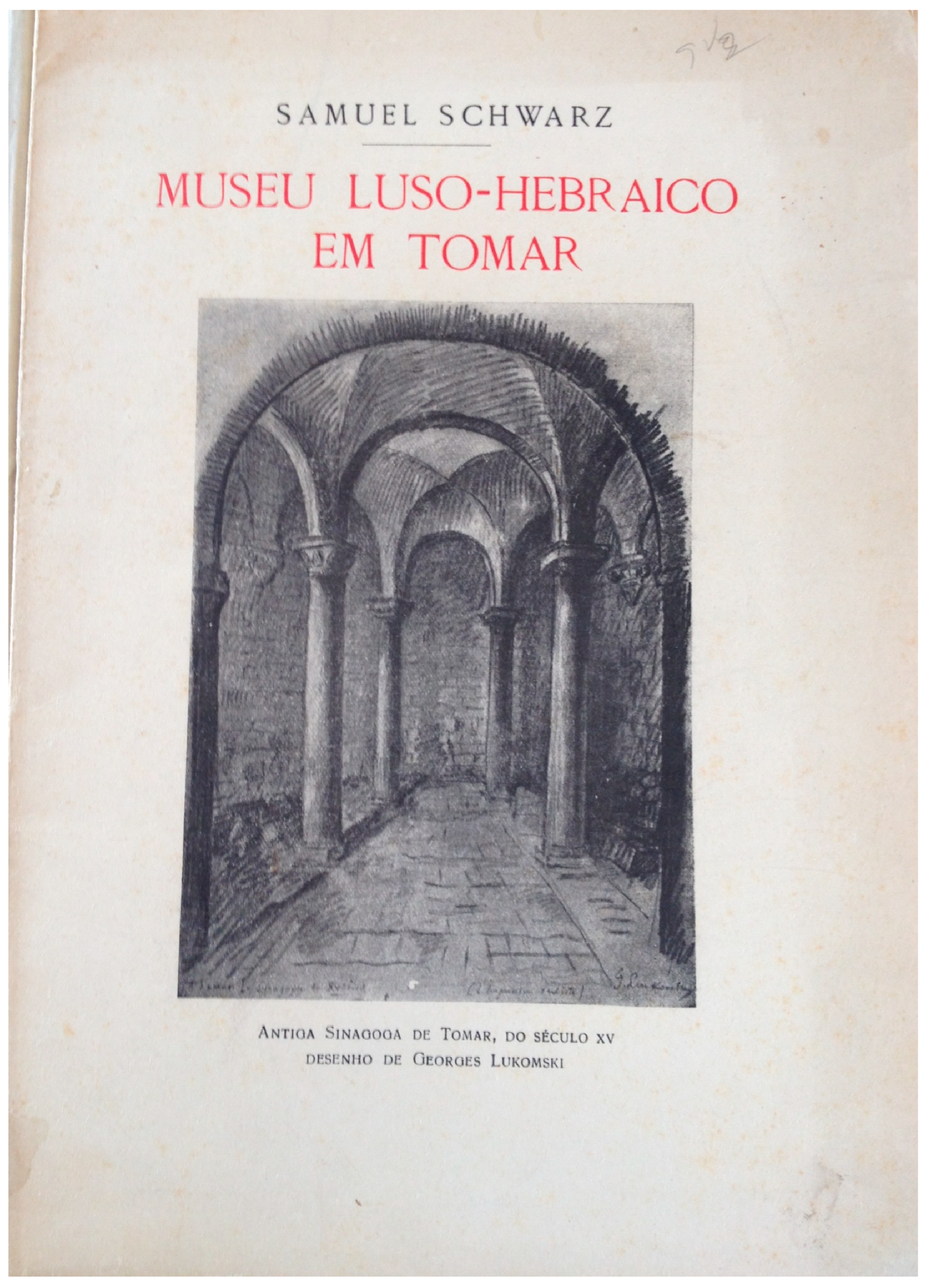

1 In a street in the old city not far from the former cathedral, a medieval synagogue is also open to tourists (

Figure 1). At the time of my fieldwork in about 2015, an older woman wearing a large Star of David welcomed visitors, whom she informed that the synagogue was the only remaining medieval Jewish place of worship in Portugal. In the late fifteenth century, Jews were forced to convert to Catholicism (

Martins 2013). As in Spain, the Portuguese Inquisition condemned those who refused, and religious and political prosecution drove thousands of Jews into exile. Portuguese and Spanish Jews subsequently moved to the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and the new World in what is called the Sephardi diaspora (

Kaplan 2000).

Five centuries later, descendants of these displaced people return to the Iberian Peninsula in search of traces of their ancestors (for Spain, see

Krakover 2013; for Portugal,

Leite 2007). The woman in charge of the Tomar synagogue, a volunteer, recalls that although relatively few Jews live in modern-day Portugal, she receives numerous Jewish visitors from Israel, Northern Europe, Latin America, and the United States. Jews from abroad travel to Tomar to visit this unusual site, a medieval synagogue that dates from a fabled era of serene coexistence between Jews, Muslims, and Christians, often called

convivencia (

Cohen 1994;

Menocal 2002). In addition to the building’s architecture, visitors can examine a series of stones bearing Hebrew script, most of them tombstones rescued from archaeological sites and local museum collections throughout Portugal. The epigraphic collection testimonies to the Jewish presence in Portugal since early medieval times. Groups of Jewish tourists occasionally pray inside the synagogue, although it is primarily viewed as a historic landmark for Jewish roots tourism or for visitors in search of significant sites in the city. The Tomar synagogue thus functions primarily as a place of memory (

Nora 1989) recalling the Sephardic past and as a key element of Jewish heritage and cultural tourism in contemporary Portugal, but only rarely as a place of worship.

This article focuses on the Hebraic epigraphy displayed in the context of the Tomar synagogue and two-fold function of these inscribed stones as both religious and heritage objects. The remains of the Portuguese Jewish past have a long history, and the way in which they were collected, valued, and transformed into heritage artifacts reveals a complex and contested social and cultural process. At the crossroads between material religion (

Meyer et al. 2010) and religious museum studies (

Paine 2013), the article illustrates how the interweaving of religious materiality as a heritage object and/or as a ritual spiritual device transpires in the context of a monument such as the Tomar synagogue. With Nathalie Cerezales, we proposed to call such an entanglement the religious heritage complex, “the continuity between the

habitus of conservation of the past within religious traditions and a conscious

policy regarding the care of past in heritage contexts” (

Isnart and Cerezales 2020, p. 6). These two systems sometimes merge, opening the religious/secular divide to more subtle, blurred interpretations. To what extent—and through what mechanisms—do Hebraic religious inscriptions displayed in an ancient synagogue transmit the intellectual and factual history of a minority religion, while also perpetuating rituals, canons, and religious knowledge beyond the devotional context? How do such engraved letters, as material artifacts, contribute to the cultural renewal of the history of a religious minority? Does this focus on letters frame the heritage-making of the Jewish past in Portugal as culturally specific? Finally, what does this process tell us about the history of Portuguese Jews within the context of the country’s history and culture?

I contend that the scholarly focus on archaeological materiality does not imply the concealment of religious or devotional uses of these artifacts. The religious heritage complex of the Tomar synagogue is made possible by oversight of the site’s erudite managers, consequently contributing to the ritual transmission of Judaism in Portugal. Combining archival work about the synagogue with ethnographic study of the space, I attempt to elucidate the status of these material vestiges of Jewish culture in Portugal and their transformation into cultural heritage. Indeed, as the framework of material religion suggests, it is vital to understand the significance of concrete aspects of religion in addition to examining its ideological and intangible dimensions.

2. Discovering the Tomar Synagogue

In 1920, Francisco Garcês Teixeira and Samuel Schwarz (

Medina 2020), both of whom lived in Lisbon and were impassioned by archaeology, linguistics, history, and monumental architecture, traveled to Tomar to visit the celebrated Convent of Christ and other monuments of the city (

Figure 2). Locals mentioned to them that there was also a synagogue in the town, used as a storage building used by a neighborhood grocer. They entered only to discover four finely decorated columns, a high ceiling, and a hall that could hold at least one hundred people. After careful study, they concluded that the warehouse was in fact the medieval synagogue of Tomar. The archaeologists’ local informants had been correct, revealing a nearly intact medieval synagogue that had survived four hundred years of concealment of the Jewish legacy in Portugal. It was a monumental discovery. Soon afterwards, Francisco Garcês Teixeira gave a talk to the Portuguese Architects’ Association, which was responsible for designating national monuments. In 1921, the synagogue became part of the Portuguese heritage list, and in 1925, Garcês Teixeira published a complete architectural and historical study demonstrating the religious and Jewish nature of the building. Samuel Schwarz, himself a Jew from Poland who had settled in Portugal in the late 1910s, purchased the synagogue and joined Garcês Teixeira in ensuring its role as an acknowledged vestige of the Portuguese Jewish history. Both men considered the discovery of the synagogue as an excellent opportunity for the Portuguese government to recognize the role of Jewish people in the nation’s history, while also underscoring the synagogue’s potential as a touristic and economic asset for the Tomar region.

During the same period, Schwarz was working on other vestiges of Portuguese Judaism, including medieval Hebrew epigraphy that he tracked down throughout the country (

Schwarz 1923), manuscripts, and incunabula dealing with Portuguese Jews (

Andrade and Caramelo 2018). He also documented the religious survival of the Marranos (or Crypto-Jews), whose traces he discovered over four centuries after their forced conversion in the fifteenth century (

Schwarz 1925). In the late 1920s, the fourfold unearthing of the Jewish past was launched from one end of the country to the other, bringing a number of religious artifacts into the scientific, cultural, and political spotlight. Findings included medieval lapidary fragments, books and manuscripts in Hebrew, and rites and traditions of the secret Jews in the Beira Baixa, as well as the Tomar synagogue, an extraordinarily well-preserved medieval place of worship in the middle of the country.

This reawakening of the Jewish presence and heritage in the early 20th century coincided with the return from Morocco and Europe of some Sephardic Jews, who settled in the south of the country (

Clarence-Smith 2020). It also coincided with the conversion of Crypto-Jews to standard Judaism, particularly in the region of Oporto under the leadership of Bastos (

Azevedo Mea and Steinhardt 1997). Their return and conversion have been discrete, and statistics as scarce, but it was encouraged in the early 1910s by the First Republic of Portugal. The Republic established the legal separation between Church and State and promoted religious diversity, although this policy was inconsistently applied to religious minorities heritage. The Tomar synagogue remains the sole Jewish asset on the national list of monuments, amid dozens of Catholic buildings and medieval castles (

Neto 2001). Despite—or because of—the lasting negative image of Jews as an oppressed minority in Portugal over four centuries, the cultural recognition of the Tomar synagogue in the early twentieth century is an exceptional—if ambiguous—event in the national history of the period.

3. A Proposed Jewish Museum in Portugal

A few years after the synagogue’s discovery, the Portuguese State came under the rule of António de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970), an authoritarian figure who reinforced the centrality of the Catholic Church. The government forbade or limited all other denominations and did not encourage the Jewish museum project in Tomar. In 1939, in the face of official silence and inaction and to protect his family from Nazi extermination, Samuel Schwarz applied for Portuguese nationality and donated the synagogue to the State.

He drafted a proposal for a national Luso-Jewish museum (

Schwarz 1939,

Figure 3), and a commission was created to pursue the project. As a public museum that would represent the past of a silenced religious minority, the group faced a number of challenges. Under the leadership of João Miguel dos Santos Simões (1907–1972), a young intellectual from Tomar, the commission included members of the State administration and the Jewish community of Lisbon, as well as scholars and representatives of the Tomar municipal government.

2 The commission enabled Schwarz and Garcês Teixeira to promote the project as consistent with the authoritarian regime’s cultural and ideological priorities and the social dynamics of the Jewish community in Portugal. The working group successfully combined the heritage, political, and religious priorities of these various constituencies. By linking religious and heritage features, the museum project permitted stakeholders to present the Portuguese Luso-Jewish Museum as a multi-purpose heritage facility. In that sense, their project can be considered a prime example of the religious heritage complex.

Despite its strategic composition, the commission’s most significant problem was the collection of artifacts. Although the synagogue was an architectural masterpiece and a recognized national monument, Schwarz and Santos Simões also planned to display a collection of heritage objects. The collection would help tell Portuguese Jewish history, educating museum visitors and enhancing their experience. The objects were expected to offer archaeological evidence for the presence of the Jews in Portugal, as well as information about the beliefs and practices of the medieval Jewish community.

Schwarz believed that the collection ought to feature three categories of objects: medieval stones engraved in Hebrew, books in Hebrew or about Jewish history from private and public libraries, including ancient, decorated Bibles, and a series of scholarly publications by members of the museum commission.

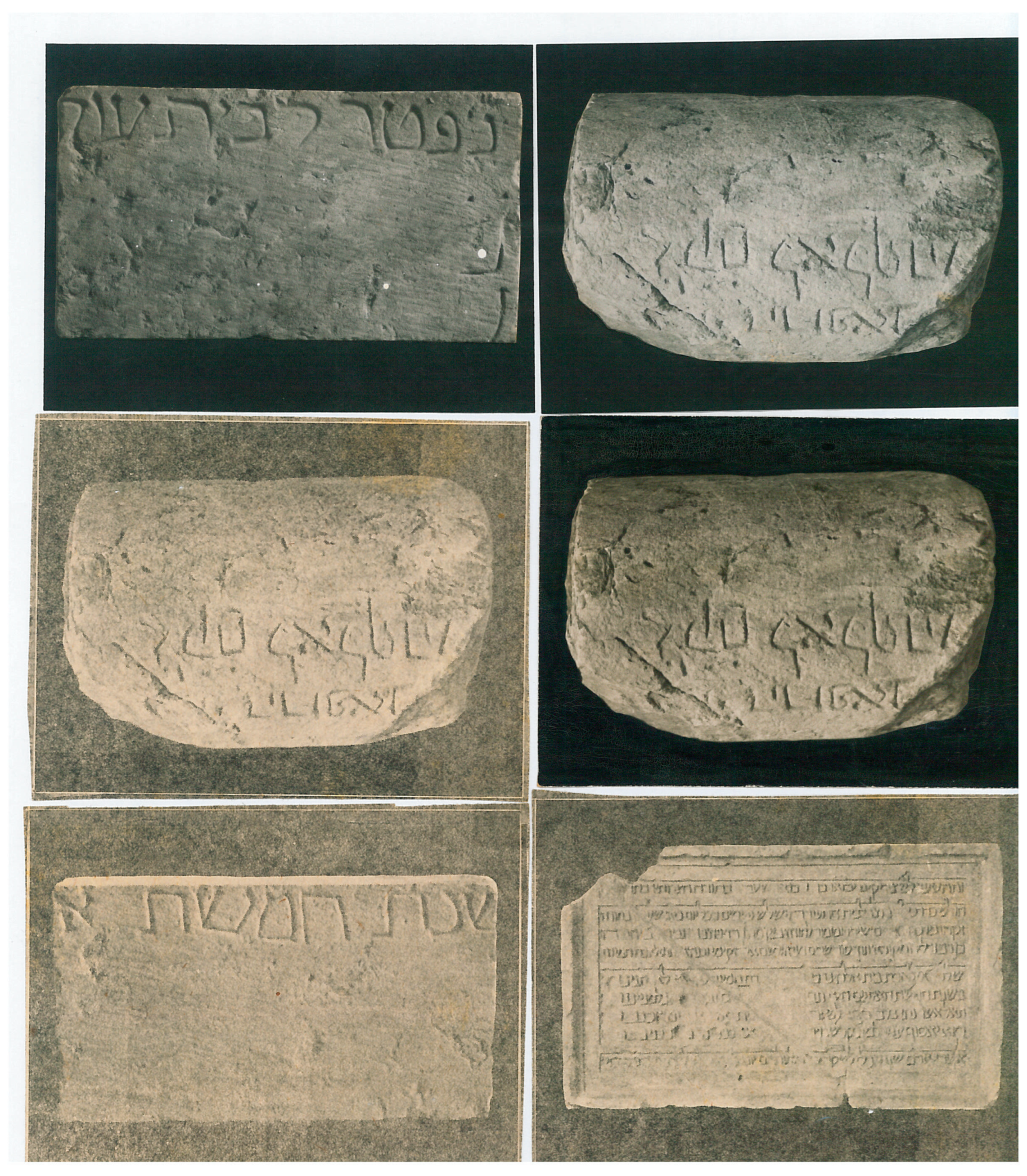

The first category consisted of the Hebrew-inscribed stones that Schwarz located, studied, and studiously catalogued (

Figure 4). He also launched a collection of approximately 10,000 Hebraic books and studies of the Jewish past in Europe that would be made available to the public in the museum’s library. The museum also financed the publication of historical studies of Tomar and Jews in Portugal (

Schwarz 1942;

Santos Simões 1943). In sum, the museum of Portuguese Jewish history was planned as a site for the collection and display of Hebrew-language inscriptions and the transmission of Jewish history through Hebrew letters. The commission decided to situate the reading and interpretation of physical Hebrew writing at the core of the visitor’s experience.

The commission was unfortunately unable to unite every category of written vestiges that they had planned to exhibit. Furthermore, the anticipated historical works never reached Tomar, and the museum printed only two new publications. Santos Simões nevertheless collected Hebrew inscriptions and partly succeeded in achieving the museum planned by the commission.

4. Displaying Hebrew Inscriptions

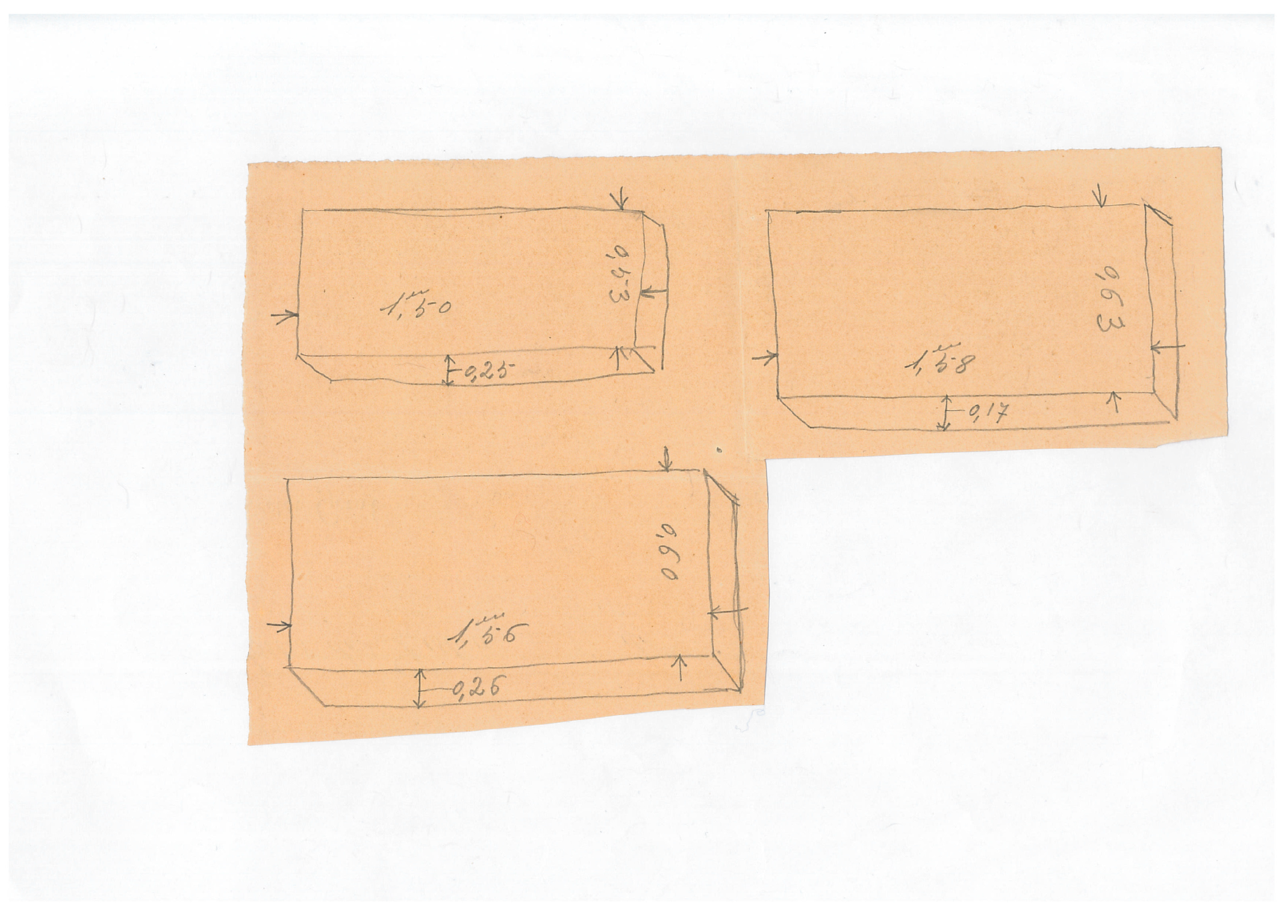

Schwarz and Santos Simões planned for reading and understanding of the ritual functions of the inscribed stones to constitute the core of the visitor experience. To this end, and in the name of consistency with what they called “contemporary museum principles”,

3 the stone collection was separated into two categories that would be displayed according to their devotional purposes: tombstones would be arranged horizontally on wooden pedestals (

Figure 5), like in a cemetery, and dedicatory inscriptions would be attached to the synagogue’s walls, as they would be in a Jewish place of worship.

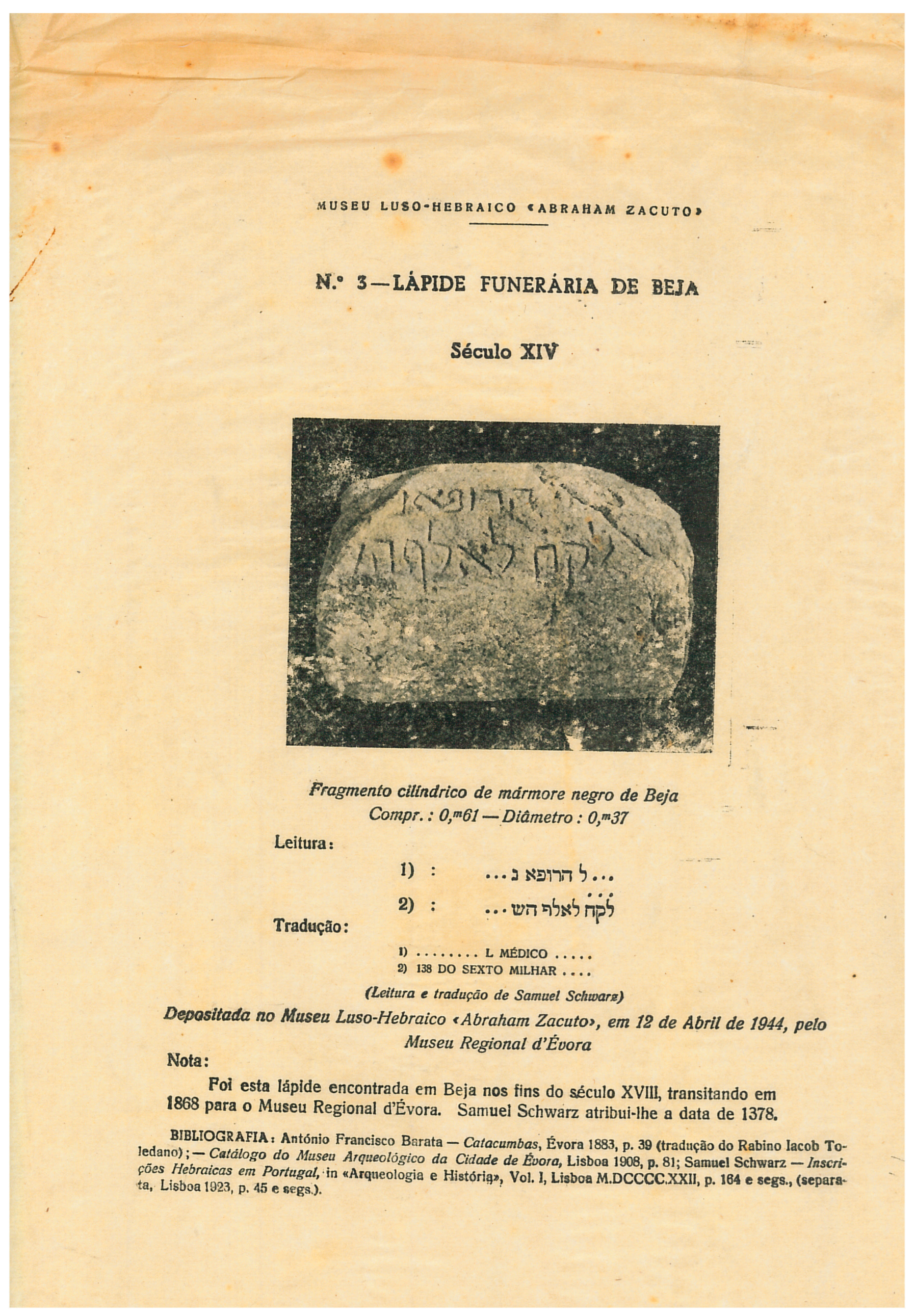

For esthetic as well as scholarly reasons, Schwarz and Santos Simões wanted to help visitors read the inscriptions by accompanying each stone with a sheet presenting the information that Schwarz had assembled for his publication on Portuguese Hebraic stones. Schwarz followed classic epigraphic methodology, which involves a material description of the support (type of mineral, dimensions, state of conservation), the history of an object’s discovery, and where it is preserved, as well as bibliographical references, an attempted transcription, a translation into contemporary characters, and dating (

Figure 6). Consistent with these modern ambitions, Schwarz and Santos Simões included a high-quality photographic reproduction with each sheet.

They also acquired a set of Hebrew printing press letters to allow local printers to produce documents for the museum (

Figure 7). In short, these sheets empowered synagogue visitors to read Hebrew epigraphy in its ritual configuration.

The material presence of these textual traces of Portuguese Jewish history—sequences of letters engraved on stones—became the center of the collection and of the museum project as a whole. The campaign to collect the stones that Schwarz had studied began with a series letters to directors of regional museums, presidents of municipalities, and the General Directorate of the of the Ministry of Higher Education and Fine Arts who were responsible for local and national archaeological collections. The operation was assisted by João Pereira Dias (1894–1960), professor of Mathematics at the University of Coimbra and, at the time, acting director general of the Ministry of Higher Education and Fine Arts. The project necessitated transporting inscribed stones to the Tomar museum from around the country, and by the late 1940s, the synagogue had received eight epigraphic pieces, including three plaster casts, from Lisbon, Faro, Espiche, Évora, and Castelo Branco that had originated in the Algarve, Porto, and the Beira Baixa.

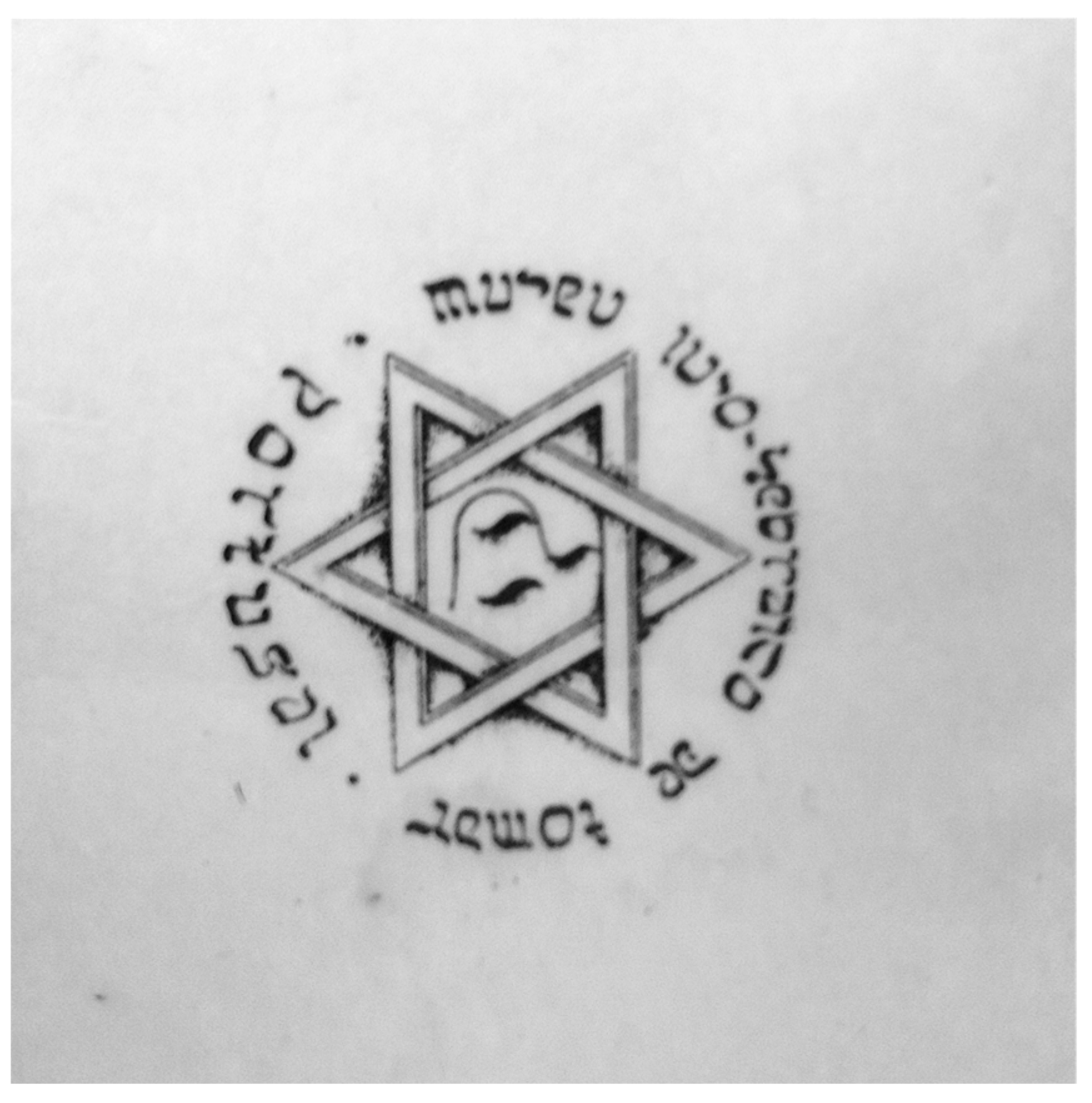

After identifying a letter that recurred on several of the stones but is not part of the Hebrew alphabet, the museum team developed an additional strategy to highlight the inscribed letters. Schwarz interpreted this enigmatic character as a representation of the unspeakable name of God in the Jewish Portuguese tradition, and it was rapidly chosen as the museum logo (

Figure 8) and was reproduced on publications and promotional documents. Santos Simões contacted the director of medieval synagogues in the Spanish city of Toledo,

4 which had similarly been transformed into national monuments and museums in the early twentieth century (see

Flesler and Melgosa 2020, pp. 141–96). The director informed him that the mysterious ideogram had also been found in Spain, further evidence that it had served as a respectful reference to God in the wider Sephardi community.

By assembling books, manuscripts, stones, translations, and the Sephardi letter representing God’s name, the museum planned by Schwarz and Santos Simões had conceptualized a museum that centered on inscribed Hebrew letters and symbolized the Portuguese Jewish past and religious practices. Although they partly achieved their objective of presenting a diversity of texts and scripts, the museum team believed that the letters themselves bore vital witness to Jewish culture in Portugal. The materiality of Hebrew-language inscriptions was indeed the only heritage asset that their museum was able to exhibit, and they planned their collection of feature engraved stones, accompanied by printed information sheets. Given the crucial role of writing, reading, and cabalistic interpretation in the Jewish religious tradition, it is unsurprising that these highly lettered men founded a museum of Jewish letters. They certainly regarded written remains as heritage assets, but also considered them as religious testimonies of Jewish faith. Nonetheless, there is something radical in their choice. In reality, their focus on letters stood in sharp contrast with other museums and exhibitions about the Jewish past, architecture, or physical artifacts from the same period.

5. Variations on Jewish Heritage

In a seminal chapter in

Destination Culture (

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, pp. 79–128), Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett examined early attempts to display Jewish religious materiality. Reviewing a series of pre-Shoah international exhibitions from 1887 to 1939, she describes the elements of Jewish culture that were featured in these highly politicized, nationalized representational projects, which included textiles, devotional items, musical instruments, furniture, local architecture, and foods. Jewish religious objects, sometimes categorized by geographical origin or as ethnographic collections, were intended to support a wide range of discourses and political leanings: nationalistic views of certain countries, the foundational role of Judaism in the history of religion, ideological dogmas promoting religious diversity and freedom, evocation of Biblical times, or even multiculturalism in America. Jewish displays at international fairs at the turn of the 20th century clearly shared a number of features and preconceptions of this specific orientation. They inserted religious materiality into the global ideological landscape, although without focusing on writing practice and Hebrew letters as was conducted in the Portuguese context. They unquestionably exemplify the global circulation of museum patterns and official uses of heritage to a greater extent than local, identity-based practices and cultural policies. As Kirshenblatt-Gimblett argues in the chapter conclusion, however, international exhibitions were created not merely to present Jewish culture—in line with Edward Said’s orientalist impulse, an idealized, partially fabricated image—but they also served as performances of Jewishness as a social, historical, cultural, and religious reality.

Indeed, a parallel can be drawn between the international Jewish “agency of display” (id.: 123) and the Portuguese museum project in Tomar. In seeking to transform visitors into readers of Hebrew inscriptions, Schwarz and Santos Simões were not endeavoring to “represent” Medieval Jews as another category of the Portuguese population, but to reinsert Sephardic experience and culture into Portuguese history through veritable encounters with medieval Jewishness, similar to the performative force of international Jewish fairs. The heritage and display experience that they imagined in the late 1940s, however, was far from an ethnographic performance in a new, global exhibit space. The fact that the inscribed Portuguese stones were intended to be read inside the only medieval synagogue in the country—unlike an international fair—underscores the uniqueness of their project which simultaneously merges national heritage and minority religious transmission.

In a recent monograph, Flesler and Pérez Melgosa describe the cultural and political fates of the synagogue in the Spanish city of Toledo (

Flesler and Melgosa 2020, pp. 141–96). Built in the second half of the fourteenth century by a Jewish member of the royal administrative elite and transformed into a church, the synagogue subsequently became a museum and national monument under the name

Sinagoga del Tránsito. The building thus became a Catholic structure that never abandoned its Jewish origins. The name thus links the Jewish word for a place of worship with the Christian term

Tránsito, which refers to the moment of the Virgin Mary’s death, depicted in a painting that was commissioned for the church. Flesler and Pérez Melgosa offer an interesting interpretation of this ambiguous building, suggesting that the synagogue could be considered as a symbol that represents

los conversos, converted Spanish Jews. Toledo’s synagogue/church is thus the equivalent of Jews who became Catholics while discretely retaining their Jewish identity (ib.: 148, 155). Despite efforts to remove the traits that recalled the building’s original religious function, Jewish traces sustain the monument’s ambiguity. Declared a national monument in 1877, the Toledo synagogue only officially became the Sephardic museum in the 1960s, after Franco proclaimed a policy of recognition towards the Jews. In addition to featuring its rich original décor, the museum, which actually opened only in 1994, promotes a narrative that explicitly emphasizes the inclusion of the Jews in Spanish history, while also exoticizing the objects, practices, and itineraries on display. The museum thereby reduces Spanish Jews to a strange, remote minority within the contemporary population.

The establishment of a museum of the Jewish past in Toledo produced an effect of temporal distancing by reducing the image of Jewish heritage to an ethnography based on ethnic difference. Toledo’s Sephardic museum, however, is based on the ethnographic model, whereas the Tomar museum invented a more innovative and original heritage apparatus by locating the reading of the Hebrew letter at the core of the visitor’s experience. Comparing the history of these two institutions also shows that the coexistence of intellectual and religious motivations in the sites does not necessarily obey similar rules. In Toledo, the religious elements that are featured are ultimately relegated to the rank of beliefs and exoticism, whereas the learned originators of the Tomar project proposed using Hebrew letters and objects to immerse visitors in medieval Portugal. These Iberian variations on the role of religion in minority heritage institutions illustrate very well the diverse expressions of the religious heritage complex, examples of which can also be found elsewhere in Europe.

The acting director of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam recently wrote an extensive review article on the specific role of Jewish places of worship in the heritagization of Judaism (

Ariese 2022). Comparing a vast body of heritage studies, Judaism studies, and literature regarding Jewish heritage and musealized synagogues, Ariese points out—among other future research topics—that analyses of the link between religion and heritage should take into account “the spatial, tangible, sensory and temporal dimensions of practices of meaning-making” (id.: 12). This concern with the sensorial and contextual contiguity of religious and heritage engagements in a single site—a synagogue—represents a potentially innovative direction for future investigations of religious heritage in general, and Jewish heritage in particular. Moreover, as the anthropology of space has long demonstrated (

De Certeau 1980, pp. 171–76), a place becomes a space only when it is inhabited by people, traversed by the circulation of objects and persons, and valued by social actors. A building, or an assemblage of physical objects, must be populated in order for relationships between space, actors, and objects to produce emotions, meanings, and a sense of temporality. Under these conditions, and because they are reciprocal dimensions of each other, religious and heritage knowledge and experiences are then able to merge and interact. Their interactions give birth to the religious heritage complex, a materiality–heritage–religion system that blurs the boundaries between religion performances and curatorial practices.

In the case of Tomar, the conservation and display of physical objects ensures the cultural return of the past of a religious minority through a specific heritage element—Hebrew letters—that provides both a heritage and religious experience for visitors. As Schwarz and Santos Simões intended, the Tomar synagogue and the engraved Portuguese stones illustrate how the religious transmission of Jewish letters and the intellectual and historical background of the exhibition’s designers overlap. Despite the fact that the literature on religious heritage reflects the conflictual and occasionally obfuscating effects of heritagization over spiritual places, devotional objects, or religious practices, under certain circumstances and in particular social configurations, the religious heritage complex can generate religious and heritage transmission, paving the way for an unexpected new presence for the most remote, marginalized spiritual legacy, including the Portuguese Jewish legacy in the twentieth century.

6. Epilogue

The Portuguese government abandoned the Luso-Hebraic museum after the epigraphic collection was installed, however. In 1957, Santos Simões left his position as director of the Tomar museum for the newly founded National Museum of the Azulejos in Lisbon. In the end, the Tomar synagogue operated as a museum for only a short period between the late 1940s and the early 1950s. The sheets describing the inscriptions were printed only once, and the much-anticipated tourists never had the good fortune of becoming—as Santos Simões and Schwarz dreamt—curious Hebraist epigraphists for a day at the ancient Portuguese Jewish temple.

The synagogue remained closed and its collection inaccessible to the public until the 1970s, when a different but equally impassioned group of individuals decided to reopen it. Tomar residents, first an elderly bachelor and then Teresa and Luís Vasco, a fiftyish couple, became local guides. Teresa Vasco, the woman with the Star of David mentioned in the introduction to this article, then joined the effort with her husband as guardians of the synagogue and the inscriptions collection. The original amateur scholars collected, interpreted, and transformed the collection into the key feature of a visit to the synagogue, whereas nearly nothing was said about it by the volunteer guides after the 1970s. Visitors were touched by the history of the synagogue and its museum (

Leite 2007;

Isnart 20225), but the stones were no longer at the center of their experience. Instead of encountering medieval Jewish letters as Schwarz and Santos Simões had planned, visitors met the local couple. Tourists were profoundly affected by the historical narrative of Jews in Portugal and the couple’s endeavor to preserve the synagogue. Between the 1970s and the 2010s, the collection of stones, although still in place, was gradually replaced by objects sent from the entire world by visitors grateful to Teresa and Luís Vasco. They received for instance rituals instruments, photographs of Jerusalem, everyday domestic Jewish objects, or books on European Jewish communities (for the analysis of these donations, see

Leite 2007). During that period, the museum thus functioned less as a place for the religious display of Hebrew letters, and more as a place of encounter with the guardians themselves. At this moment, the modalities of the religious heritage complex shifted from the erudite collection of inscriptions to a more emotional and individual materiality displayed as the symbol of Portuguese Jewishness. However, the two categories of religious objects and their heritage uses bring to light a way in which “religious actors perform their doctrinal beliefs, their commitment to supernatural entities, and their inscription within an ancient spiritual genealogy” (

Isnart and Cerezales 2020, p. 213).

By 2023, though, the Vasco couple, who breathed life into the synagogue for nearly thirty years, are no longer, and the synagogue has entered a new phase. Renovated and cleared of the items donated to the Vascos, the synagogue now showcases the epigraphic collection without any explanation. It is endowed with a museographical space that presents the economic role, persecution, and sad fate of Tomar’s Jewish population during the Middle Ages. However, in the absence of the volunteer guardians who gave a unique flavor to the site, and the erudite scholars who celebrated Hebrew letters, the Tomar synagogue and its inscriptions are henceforth included in the Portuguese national heritage and tourist network of judarias. It is described as an important stop on the circuit of Israeli, Brazilian, and European groups who follow traces of Portuguese Jews.

The utopia of a museum of Hebrew letters created by a pair of learned early twentieth-century scholars lasted only a few decades, and despite their enormous achievement in assembling a significant collection of medieval Jewish epigraphy in Tomar, it would surely have been a bittersweet experience for its discoverers to witness how the synagogue has subsequently evolved.