Abstract

To enhance the autonomous operation capability of deep-sea mining vehicle formations, this study addresses the issues of slow convergence in formation path planning and insufficient obstacle avoidance flexibility under complex environments by investigating a global path planning and local obstacle avoidance strategy based on an improved RRT algorithm*. Through dynamic elliptical sampling, adaptive goal-biased sampling, safe distance detection, and path smoothing optimization, the efficiency and passability of path planning are improved. For the obstacle avoidance of formation members, a priority determination model incorporating local obstacle avoidance, formation contraction, and transformation is designed, and methods such as Gaussian distribution fan-shaped sampling and trajectory backtracking are proposed to optimize the local planning effect. Simulation results show that this method can effectively improve the path planning quality and obstacle avoidance performance of mining vehicle formations in complex environments. Specifically, when in a longitudinal formation, the maximum inter-vehicle error is approximately 15.1%, and the average error is controlled within 3.5%; when in a triangular formation, the maximum inter-vehicle error is approximately 20%, and the average error is controlled within 4.2%, indicating promising application prospects.

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of global demand for the development of deep-sea mineral resources, deep-sea mining technology has become a crucial research direction in the fields of marine engineering and resource development [1,2,3]. In recent years, the formation mode using multiple deep-sea mining vehicles for collaborative operations has been widely applied in large-scale development operations in deep-sea mining areas due to its high efficiency and reliability. However, a single mining vehicle has limitations in terms of operational load capacity and environmental perception range, making it difficult to undertake large-scale and highly complex deep-sea mining tasks. Thus, formation operations have become an important approach to improve the overall performance of the system [4]. During the operation of deep-sea mining vehicle formations, path planning and obstacle avoidance capabilities are among the core technologies for achieving autonomous operations. Since 2020, sampling-based path planning methods have made a series of progresses in improving sampling efficiency and path quality. Gammell [5] et al. pointed out that methods such as RRT and PRM are still limited by low sampling efficiency and insufficient dynamic response capabilities. Subsequently, the Daniel Rakita team proposed a method that introduces potential regions for priority sampling. This method uses historical collision states as sampling guidance and combines with a local minimum sample elimination mechanism to improve sampling efficiency [6]. However, it fails to consider issues such as path length and path smoothness that may not conform to the kinematic model. The Qi Jie [7] team introduced path reconstruction and smoothing mechanisms into RRT, taking both length and smoothness into account. In 2022, the Meng Qinghu team built a deep neural network model. By inputting historical trajectories to train the model, they successfully predicted high-potential sampling regions, thereby guiding non-uniform sampling to converge to the optimal path more efficiently and improving overall planning efficiency [8]. Nevertheless, it still has shortcomings in terms of parameter sensitivity, adaptability to geometric constraints, high-dimensional scalability, dynamic environment handling capabilities, and comprehensiveness of experimental verification. In 2023, the Chen Yuan [9] team enhanced the search effect through columnar sampling regions and a hierarchical heuristic strategy; the Xie Haibo [10] team adopted elliptical connection and interpolation methods to improve kinematic feasibility. By 2024, the Chai Runqi [11] team proposed a sampling-trajectory hierarchical optimization framework to enhance control adaptability; the Huang Yuan [12] team combined elliptical sampling with a tree evaluation mechanism in narrow environments to optimize path accessibility. Overall, most studies improve algorithm performance through non-uniform sampling, learning guidance, and trajectory optimization. However, adaptation to dynamic environments and handling of complex constraints remain key focuses for future research.

To address key challenges in multi-agent formation control, including pose maintenance, formation scheduling, obstacle avoidance and path tracking, researchers have proposed numerous targeted control strategies. Mainstream approaches are primarily categorized into three types: (1) Virtual structure method: This approach treats the formation as an integrated rigid structure, with its core being the establishment of a virtual formation skeleton. Guided by this skeleton, members maintain fixed geometric relationships for coordinated motion, which enhances overall stability while simplifying individual local control. Extensive fruitful achievements have been attained in relevant research [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. (2) Leader-follower method: This strategy designates one robot as the leader that determines the formation’s overall motion characteristics and direction, while the remaining robots serve as followers tasked with maintaining a desired relative pose to the leader. Widely adopted for its simple structure and good scalability, this method exhibits high leader dependence and thus poor fault tolerance, as leader malfunctions are prone to compromising the entire formation [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. (3) Distributed control method: This method dispenses with a central information processing node, and each member achieves coordinated control solely through information interaction with adjacent agents. Featuring simple implementation and strong robustness, it has been extensively applied across multiple fields [29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

To address the core issues of slow convergence speed in path planning and insufficient obstacle avoidance flexibility of deep-sea mining vehicle formations in complex seabed environments, this paper selects the RRT algorithm framework for systematic improvement. This selection is mainly based on the following considerations: Compared with algorithms such as Probabilistic Roadmap (PRM) that require the construction of a global roadmap, RRT, as a tree-based incremental search algorithm, does not need to pre-construct a complete graph structure. It is more suitable for high-dimensional and dynamically changing complex environments, and its single-query characteristic has real-time potential in deep-sea operations with limited computing resources. Compared with the basic RRT algorithm, RRT* possesses asymptotic optimality through the “parent re-selection” and “rewiring” mechanisms, which can ensure that the path cost converges to the global optimum, better meeting the requirements of deep-sea mining for economy and stability. In addition, RRT* is more suitable for motion planning in continuous spaces. Compared with local planning methods such as the artificial potential field method, its random sampling mechanism has stronger global exploration capabilities and is less likely to fall into local minima. Of course, the traditional RRT* algorithm still has defects in formation path planning, such as uneven sampling distribution, insufficient path smoothness, and failure to consider formation geometric constraints. Therefore, this paper focuses on conducting targeted improvements around the above bottlenecks.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows: At the level of leader vehicle global path planning, a dynamic elliptical sampling region and an adaptive goal-biased sampling strategy are proposed, combined with safe distance detection and a multi-index path evaluation function, which significantly improves the convergence speed, smoothness of the path, and formation passage safety. At the level of follower vehicle local obstacle avoidance, a local planning method based on Gaussian distribution fan-shaped sampling is designed, and a multi-mode obstacle avoidance decision-making mechanism integrating local re-planning, formation contraction, and formation transformation is constructed, which effectively enhances the adaptability and coordination of the formation in dynamic obstacle environments.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the limitations of the traditional RRT algorithm in formation path planning; Section 3 elaborates on the improved RRT algorithm for the leader vehicle, including sampling strategies, safety detection, and path optimization methods; Section 4 presents the local obstacle avoidance strategy for follower vehicles, covering fan-shaped sampling design, behavior decision-making, and trajectory generation; Section 5 verifies the superiority of the proposed algorithm in terms of path quality and obstacle avoidance performance through multiple sets of simulation experiments; Section 6 discusses the research constraints and limitations of this study; finally, Section 7 summarizes the research findings and prospects future research directions.

2. Formation Applicability Analysis of the Traditional RRT* Algorithm

2.1. Traditional RRT*

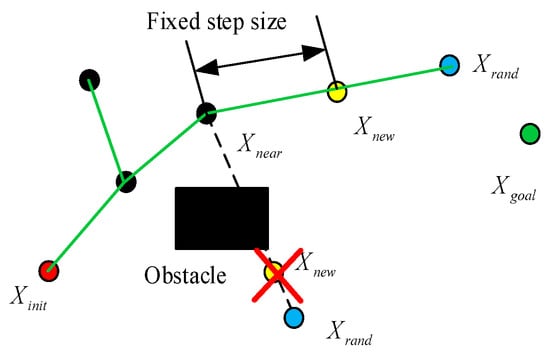

The traditional RRT* algorithm is improved on the basis of the RRT algorithm, and the purpose is to introduce the optimization strategy of new node reselection of parent node and node reconnection, so as to obtain the global path tends to be optimal. The search process of the RRT algorithm is shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of RRT algorithm search.

As can be seen from Figure 1, the search process of the RRT algorithm mainly includes the following six steps:

The first step is random sampling, and a point is randomly generated in the search space; The second step is to find the nearest node, and find the node closest to in the currently generated tree structure, which is denoted as ; The third step is to expand the tree and expand a new node from to in a fixed step. The fourth step is collision detection, check whether the path from to touches an obstacle, if there is no collision, add to the tree as a new exploration point, if falls into an obstacle, discard the point and continue random sampling; The fifth step is to repeat the expansion, repeating steps 1 to 4 until a path is found to connect to the target point Xgoal; The sixth step is path generation, once the target point is explored, you can backtrack backwards from the target point Xgoal to the starting point through backtracking, and form the final path.

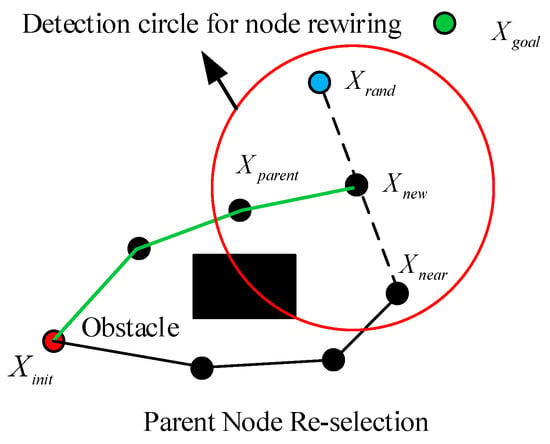

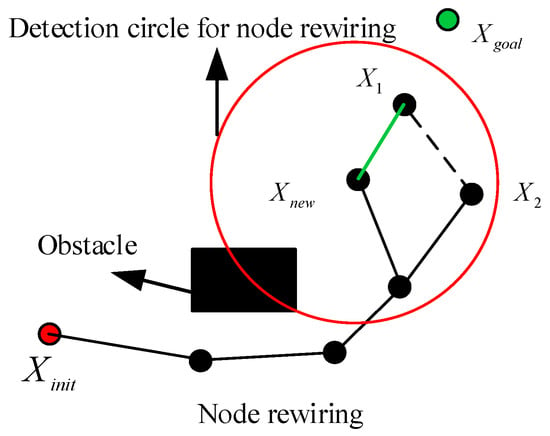

In order to further improve the quality of the planning path, an RRT* algorithm was derived. During the path search process, the RRT* algorithm not only searches for new path nodes, but also gradually converges to the global optimal solution by reconnecting the tree structure and optimizing the path costs of neighboring nodes, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Parent node re-selection in the RRT* algorithm.

Figure 3.

Node rewiring mechanism in the RRT* algorithm.

2.2. Formation Applicability Analysis

Analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of the above two algorithms, the RRT* algorithm is more suitable for path planning in complex road conditions, but it still has limitations when used in deep-sea mining vehicle formation path planning scenarios:

- (1)

- The distribution of sampling points is uneven. The traditional RRT* adopts global random sampling, which is prone to uneven distribution of sampling points, resulting in large differences in the length of path segments, affecting the synchronous following and motion fluency between formation vehicles, and increasing the difficulty of path tracking control.

- (2)

- Insufficient path smoothness. Although RRT* optimizes the path length through the path reconnection mechanism, the generated trajectory is still discrete and the curvature changes are discontinuous, which is difficult to meet the high requirements of smoothness and controllability of formation trajectory tracking.

- (3)

- Vehicle size constraints are not considered. In the process of sampling and feasibility testing, RRT* usually only focuses on the accessibility of sampling points, and does not fully consider the external dimensions of vehicles, which is easy to generate areas with insufficient path space, which limits the passability of bicycles, and it is more difficult to ensure the overall passability and safety of the entire formation.

In summary, although the RRT* algorithm has good global planning capabilities, it still needs to be improved in the application of deep-sea mining vehicle formation path planning to improve the formation adaptability and meet the needs of formation autonomous operation in complex environments.

3. Formation Constraint-Based RRT* Algorithm for Leader Vehicle

3.1. Improved Goal-Biased Sampling Strategy

However, in different planning stages, this static strategy cannot adapt to the needs of path search, which may lead to over-focusing of the algorithm in the early stage, limit the global exploration, and may lead to slow convergence of the algorithm and increase the search redundancy in the later stage. Therefore, an improved target bias sampling model is constructed [36], where Pk represents the iterative-driven bias sampling function; Pd denotes a distance-driven biased probability function.

In the formulation, k denotes the current iteration count, α serves as an adjustment coefficient, and d represents the current distance measurement, where the predefined maximum distance dmax is taken as the Euclidean distance between the start and end points. The fusion coefficient λ ∈ [0,1] balances the relative influence of iteration count and distance metrics on the biased sampling process, with λ empirically set to 0.5 in this study. The target point and random sampling point are denoted by Xgoal l and Xrand, respectively, while U(free) characterizes the feasible sampling region.

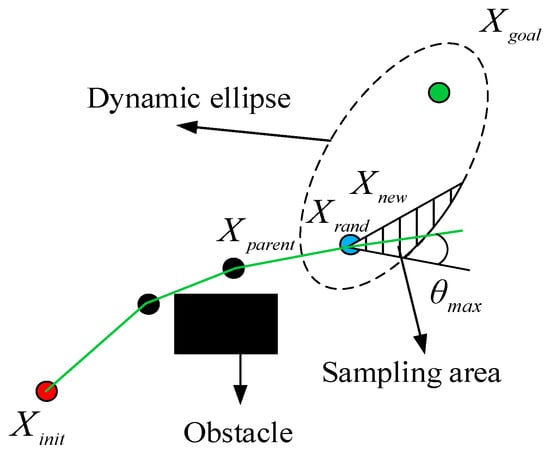

3.2. Determination of the Sampling Region Under Dual Constraints

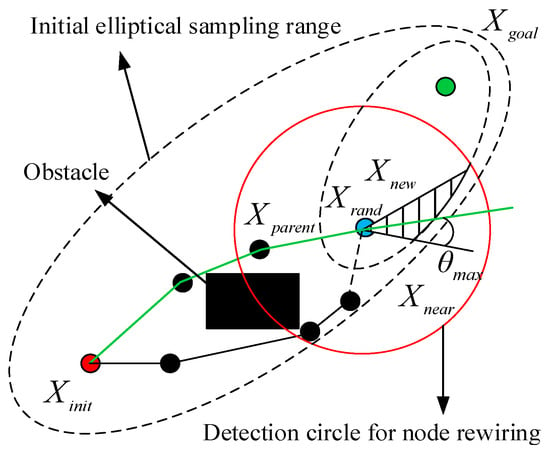

In spatial sampling-based path planning algorithms, the indirect factor reducing search efficiency is the excessive dispersion of random samples, while the direct cause is an overly large sampling space, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Sampling region under dual constraints of the improved RRT* algorithm.

Therefore, to reduce the sampling space size and improve the algorithm’s convergence rate, this section introduces dual constraints on the sampling region by incorporating both the curvature constraints from the vehicle kinematics model and the dynamic ellipse strategy. Specifically, the sampling area is confined to the intersection region defined by these two factors.

3.3. Design of Safety Distance Checking for Sampling Points Under Formation Constraints

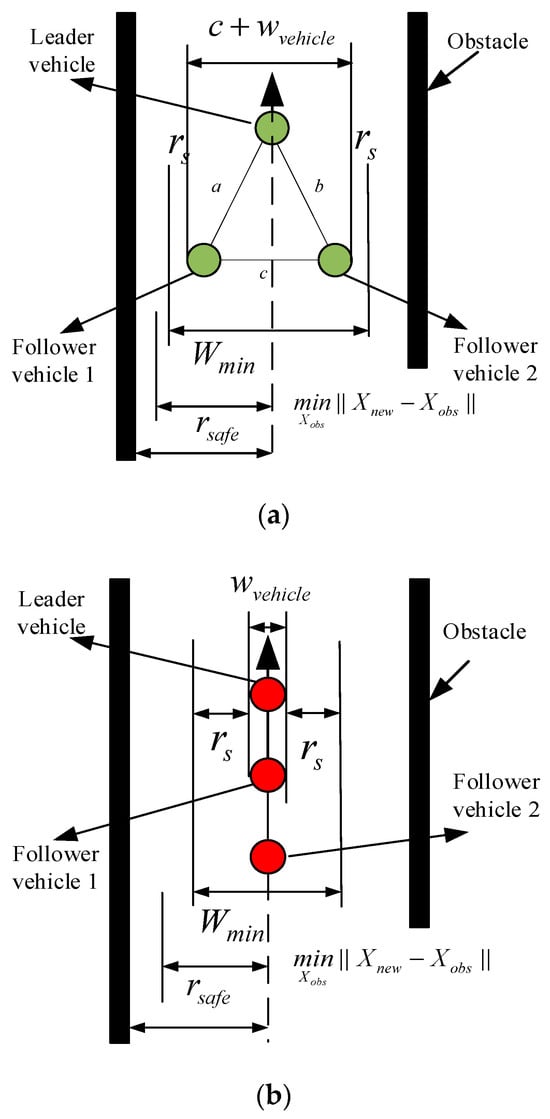

To ensure that the vicinity of sampled points meets the safety requirements for either formation navigation or individual vehicle passage, this section establishes a safety zone with radius rsafe around each new candidate node Xnew [37], as shown in Figure 5. If any obstacle is detected within this region satisfying Equation (4), the node Xnew is discarded and resampling is performed.

Figure 5.

Minimum passage size for formation. (a) Minimum passage size for triangular formation. (b) Minimum passage size for longitudinal formation.

In the formulation: Xobs denotes the obstacle position; Xnew represents the position of the new node; rsafe indicates the safety radius centered at Xnew, which must satisfy the minimum passage width constraint Wmin < 2rsafe.

The minimum passage width Wmin for triangular formations can be determined by the following equation:

In the formulation, c represents the inter-vehicle following distance, rs denotes the safety margin (i.e., the safe distance between formation vehicles), and wvehicle is the vehicle body width. This study sets the safety margin rs to 0.2 times the vehicle width. The minimum passage width Wmin for longitudinal vehicle formations can be expressed by the following equation:

In the formulation, wvehicle represents the vehicle body width, and rs denotes the safety margin, which is set to 0.2 times the vehicle width in this study.

3.4. Design of Path Evaluation Function

The improved RRT* algorithm proposed in this study generates multiple candidate paths that satisfy feasibility constraints during the planning process. These paths differ in length, smoothness, safety, and operational cost. Relying solely on “passability” as the selection criterion cannot guarantee higher-quality paths. Therefore, a comprehensive path evaluation function was designed to quantitatively assess all candidates, enabling more informed path selection and optimization.

The evaluation function incorporates five key metrics: path length (L), average curvature (), maximum curvature (), operational cost (C), and safety distance (D) [38].

To integrate these five evaluation metrics into a unified scoring value, this paper proposes a weighted normalization model, with the comprehensive Score function formulated as follows:

The formulation uses normalized metrics , , , and to represent path length, average curvature, maximum curvature, operational cost, and safety distance, respectively. The corresponding weights , , , , are assigned values of 0.3, 0.3, 0.1, 0.1, and 0.2. In this study, valid path planning solutions must achieve a comprehensive Score greater than 0.5.

3.5. Procedure of the Improved RRT* Algorithm

The workflow of our enhanced RRT* algorithm for path planning consists of the following steps:

- (1)

- Initialization Phase

The algorithm initializes with start node Xinit (containing pose information) and goal node Xgoal. Key parameters are configured: sampling range (set to grid map dimensions), goal-biased probability Pgoal, extension step size (distance between sampled point and nearest node Xnear), maximum steering angle θmax, and dynamic ellipse foci(Xinit, Xgoal). The search tree T is initialized with Xinit as root node.

- (2)

- Iterative Expansion Loop

The algorithm iterates until finding a feasible path or reaching maximum iterations:

(1) Sampling:

Generates Xrand through biased sampling. When Pgoal ≤ ϵ, it performs goal-biased sampling (Xrand = Xgoal); otherwise, random sampling occurs in the intersection of elliptical and sector regions (initial ellipse defined by Xinit and Xgoal).

(2) Nearest Node Selection:

Identifies Xnear in tree T closest to Xrand.

(3) Node Expansion:

Extends toward Xrand from Xnear with maximum step size Δq to create Xnew.

(4) Collision Checking:

Verifies both path clearance between Xnew and Xnear, and obstacle-free safety radius rsafe around Xnew. Collided nodes are discarded.

(5) Optimal Parent Selection:

Within Xnew’s neighborhood, identifies optimal parent Xparent minimizing path cost (satisfying Equation (8)), then rewires the tree.

(6) Local Rewiring:

The algorithm performs neighborhood optimization by re-examining all nodes near Xnew. If any node’s path cost can be reduced by using Xnew as a relay point, its parent node is updated accordingly.

(7) Dynamic Ellipse Update:

The elliptical sampling region is adaptively updated using Xnew and Xgoal as the new pair of focal points.

(8) Goal Check:

If Xnew enters the neighborhood of Xgoal, the algorithm attempts direct connection to finalize the complete path.

- (3)

- Termination Conditions

(1) Path Found:

When Xgoal is successfully added to tree T, the algorithm verifies whether the path satisfies all evaluation metrics. Qualified solutions are output as final results.

(2) Iteration Limit:

The search terminates if no valid path is found after maximum iterations, returning a failure status, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the improved RRT* algorithm search process.

4. Formation Behavior-Based Obstacle Avoidance RRT* Algorithm for Follower Vehicles

4.1. Sector Sampling Region Design Based on Gaussian Distribution

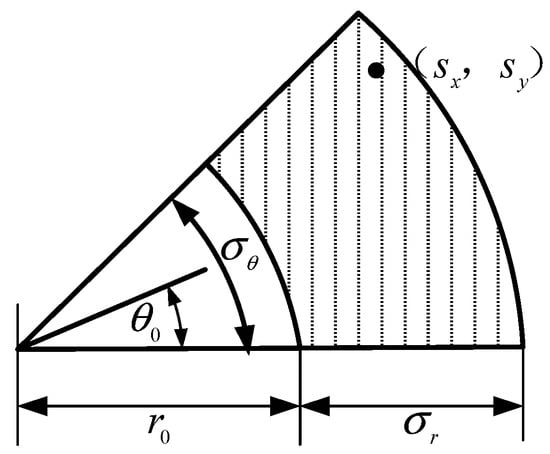

The sampling process utilizes a Gaussian distribution whose exploration breadth can be precisely tuned through the standard deviation , offering strong directional guidance and focused sampling characteristics.

To enhance convergence efficiency, we integrate this Gaussian sampling strategy with sector-based region constraints. The resulting hybrid sampling space, combining the probabilistic properties of Gaussian distribution with geometric constraints of sector sampling, is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Sampling fan-shaped region.

To effectively integrate the Gaussian distribution function with the sector sampling region, the sampling point calculation formula is designed as follows:

The coordinates of the reference sampling point are denoted by x0 (horizontal) and y0 (vertical), while sx and sy represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the generated sampling point, respectively. The relative distance and angle between the sampling point and reference point are characterized by r and θ correspondingly, whose mathematical formulations are presented below:

The compensation values for the reference point coordinates are denoted as , corresponding to the mean values in the Gaussian distribution, while represent the standard deviations of the Gaussian distribution, and are the random variables.

4.2. Formation Local Obstacle Avoidance Planning Strategy

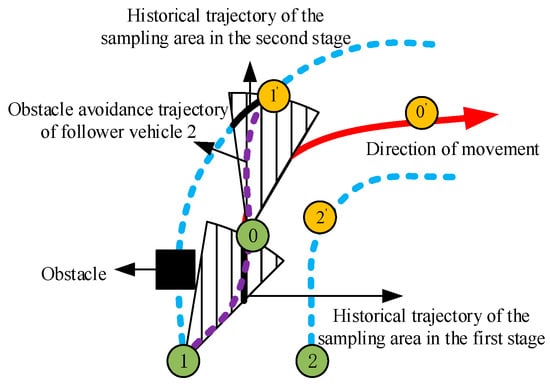

During local obstacle avoidance, the rational design of sampling regions critically impacts both path planning efficiency and obstacle avoidance performance. This paper proposes a segmented sampling region strategy that dynamically adjusts the sampling area by incorporating formation structure characteristics and vehicle kinematic constraints, thereby enhancing planning effectiveness.

At the current time step, the follower vehicle obtains obstacle position information ahead via sensors. In this phase, the leader vehicle’s current position is set as the path planning goal, while the follower’s current position serves as the starting point. A sector-shaped sampling region is constructed with the line connecting the two vehicles as the central axis. This region effectively constrains the sampling space, focusing sampling points within a feasible reachable area and avoiding numerous invalid samples. As shown in Figure 8, the green markers 0, 1, and 2 correspond to the initial positions of the leader vehicle and the two follower vehicles, respectively, while the yellow markers indicate their desired positions. The sector region is dynamically updated during the formation movement.

Figure 8.

Local obstacle avoidance planning strategy for formation.

In the second sampling phase, once the follower vehicle completes trajectory tracking to its current target position (the leader’s previous timestep position) via the MPC control algorithm, the sampling region is redefined. This updated sector-shaped region originates from the follower’s current position, with the ideal formation position—calculated based on the leader’s current location—as the new path planning target, thereby enhancing the efficiency of sampling for formation maintenance and obstacle avoidance.

Despite the effective reduction in sampling space through segmented sampling region design, insufficient sampling point validity remains a critical factor compromising planning efficiency.

In the formulation, Xgoal denotes the target point, Xrand represents the sampling point, and defines the set of historical trajectory points. The probability parameters and are set to 0.25 and 0.75, respectively, in this study, while U(free) characterizes the feasible sampling region.

To further enhance sampling quality and search efficiency, this paper introduces a historical-trajectory-biased sampling strategy. Within the constrained sampling region, trajectory points from historical paths are prioritized as candidate sampling points, guiding the sampling process toward previously feasible trajectory areas to improve search convergence. The mathematical model for biased sampling is presented in Equation (11).

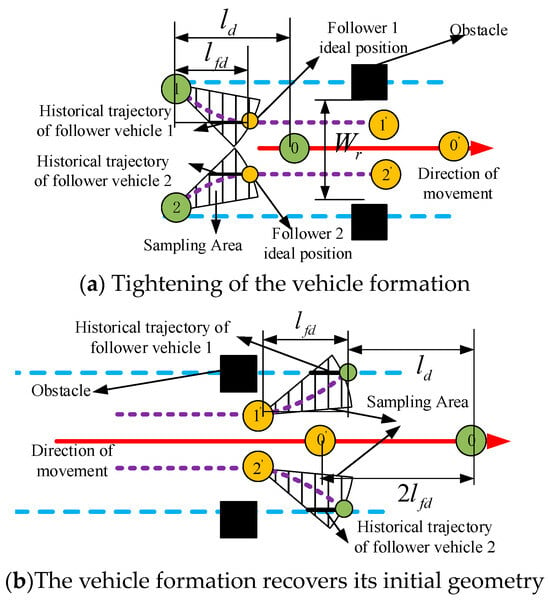

4.3. Formation Contraction Obstacle Avoidance Planning Strategy

The computational model for determining the contracted formation size is presented in Equation (12). Once the contracted formation dimension Dnew is obtained, the ideal formation positions are calculated by integrating both the formation geometry and the angle-distance model, serving as target points for subsequent obstacle-avoidance path planning.

In the formulation, Dnew represents the contracted formation size, defined as the distance between the centroids of the two follower vehicles after contraction, denotes the contraction coefficient (set to 0.65 in this study), and indicates the minimum distance between obstacles.

During formation contraction, once the ideal positions of the follower vehicles are determined, the obstacle-avoidance path planning sampling region is subsequently established, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Formation contraction obstacle avoidance planning strategy.

The methodology employed here follows a similar approach to the sampling point selection for local formation obstacle avoidance, and thus will not be reiterated. Historical trajectory references for sampling points are illustrated in Figure 9, while the mathematical model for biased sampling is provided in Equation (11), with parameter configurations identical to those used in local formation obstacle avoidance.

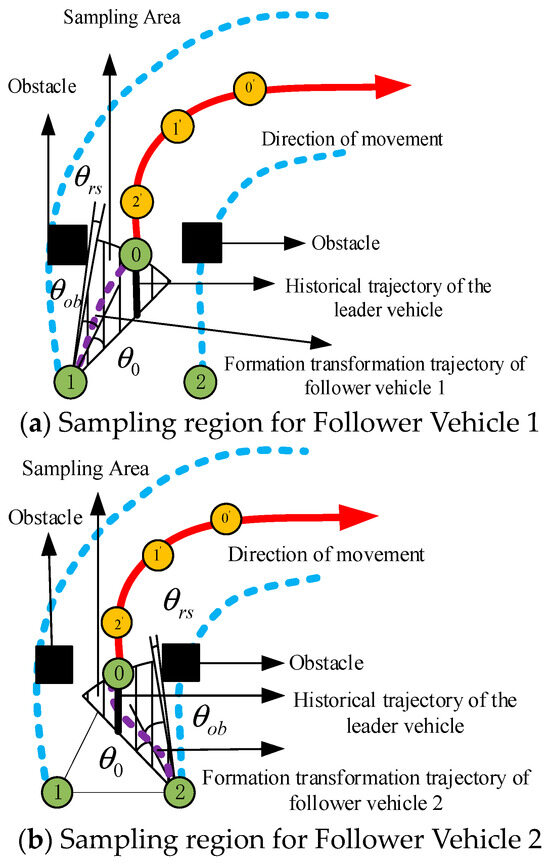

4.4. Formation Transformation Obstacle Avoidance Planning Strategy

Formation transformation differs from other obstacle avoidance methods because the simultaneous adjustment of relative positions among formation members can introduce collision risks, thereby affecting the safety of formation navigation. To mitigate this issue, this section implements a sequential transformation strategy, where follower vehicles reconfigure in ascending order according to their assigned numbers, proceeding step-by-step until the entire formation completes its transformation.

The path planning sampling region for Follower 1′s formation transformation is defined as a sector centered at its current position, with an arc boundary determined by the leader vehicle’s current location. This sector preserves the same safety margins along its edges as those applied in the local formation obstacle avoidance strategy, and its angular span strictly complies with the vehicle’s kinematic curvature constraints. The sampling region for Follower 2 is established using an identical approach and thus will not be described redundantly here.

The method employed here follows a similar approach to the sampling point selection for local formation obstacle avoidance, and therefore will not be elaborated further. Historical trajectory references for sampling points are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Formation transformation and obstacle avoidance.

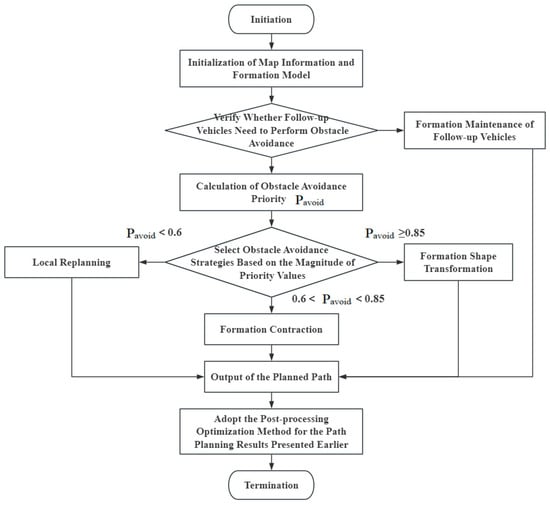

4.5. Formation Obstacle Avoidance Workflow

The workflow for formation obstacle avoidance path planning is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of formation obstacle avoidance path planning.

5. Simulation Verification and Data Analysis

To validate the proposed formation path planning method, experiments were conducted in a 2D grid map environment under Ubuntu 20.04, verifying the effectiveness of both the formation path planning approach and obstacle avoidance strategy.

5.1. Simulation in an Obstacle-Free Environment

This section configures the parameters of the improved RRT* path planning algorithm, with detailed settings provided in Table 1. To ensure fair and scientific algorithm comparison, both the enhanced RRT* and conventional RRT* algorithms maintain identical sampling and expansion parameters within the same map environment. Furthermore, multiple independent simulation tests were conducted under each experimental condition, with the average values adopted as final evaluation metrics.

Table 1.

Parameters of the improved RRT* algorithm.

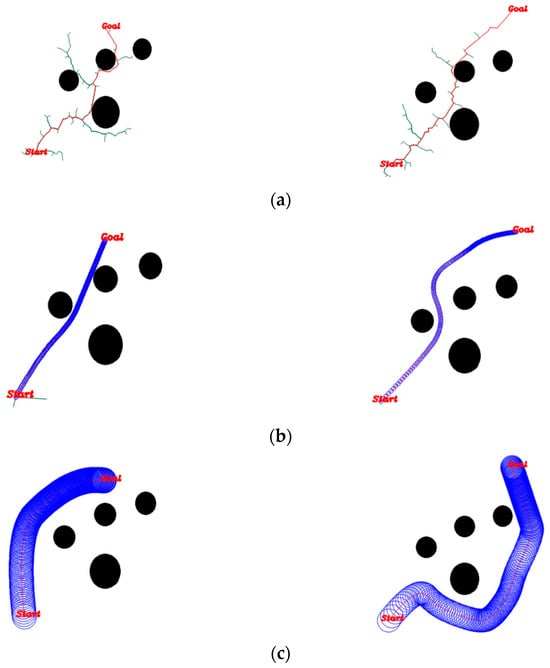

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improved RRT* algorithm, comparative path planning experiments were conducted in both Group A and Group B test environments. The evaluation compared the proposed method against conventional RRT* and deep reinforcement learning approaches, with performance metrics including three key indicators: path length, average curvature, and maximum curvature. Visualized results are presented in Figure 12, while quantitative data are detailed in Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 12.

Visualization of results. (a) Traditional RRT* planning algorithm. (b) Improved RRT* algorithm under a passage size of 10. (c) Improved RRT* algorithm under a passage size of 60.

Table 2.

Comparison of path planning data of different algorithms in Group A.

Table 3.

Comparison of path planning data of different algorithms in Group B.

As illustrated in the figure, the proposed algorithm demonstrates superior performance compared to the traditional RRT* algorithm in terms of path smoothness, obstacle avoidance capability, and adaptability to varying passage constraints, making it well-suited for formation systems.

As shown in the table below, in groups A and B, when the passage constraint is set to 10 pixels, the improved RRT* algorithm outperforms the traditional RRT* algorithm in terms of path length, average curvature, and maximum curvature, all of which are lower in value. When the passage constraint increases to 60 pixels, the improved RRT* algorithm in group B yields a slightly longer path length compared to the traditional RRT* algorithm, while still achieving lower values in both average curvature and maximum curvature.

Overall, the proposed algorithm demonstrates more comprehensive data and superior performance in terms of path smoothness and curvature control, highlighting its stronger engineering applicability in terms of overall controllability and drivability.

5.2. Simulation in an Environment with Obstacles

To further verify the performance of the proposed formation obstacle avoidance strategy based on formation behaviors, the traditional RRT and traditional RRT* algorithms are introduced as comparison benchmarks, as shown in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Algorithm results comparison for local replanning behavior.

Table 5.

Algorithm results comparison for formation transformation behavior.

Table 6.

Comparison of algorithm results for formation contraction behavior.

A triangular formation is configured in the experiment, with the initial vehicle poses consistent with those in an obstacle-free environment. The maximum number of sampling iterations for all three algorithms is set to 50.

Evaluation metrics for the comparative analysis include the number of iterations, number of nodes, path length, and path curvature. The final comparison results are obtained by averaging each metric over 50 simulation runs to ensure fairness in algorithm comparison.

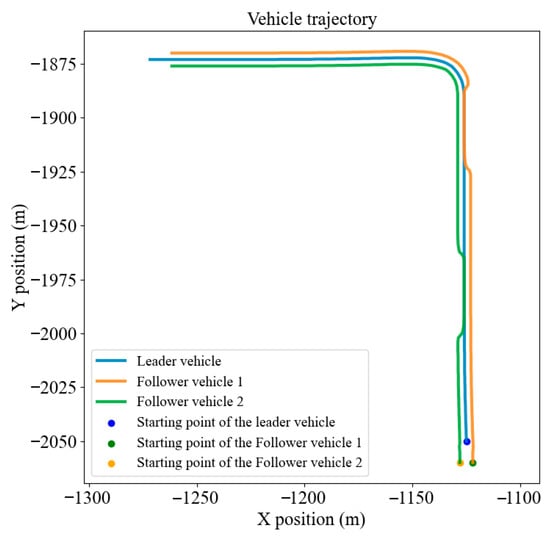

The results of the local re-planning obstacle avoidance experiment are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Local replanning obstacle avoidance path planning results.

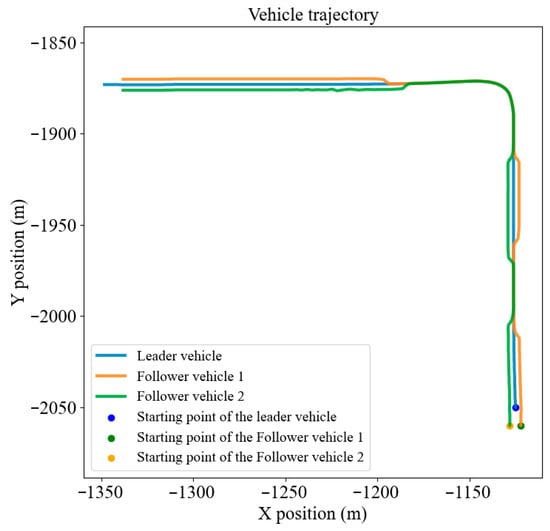

The results of the formation transformation and obstacle avoidance experiment are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Formation transformation obstacle avoidance path planning results.

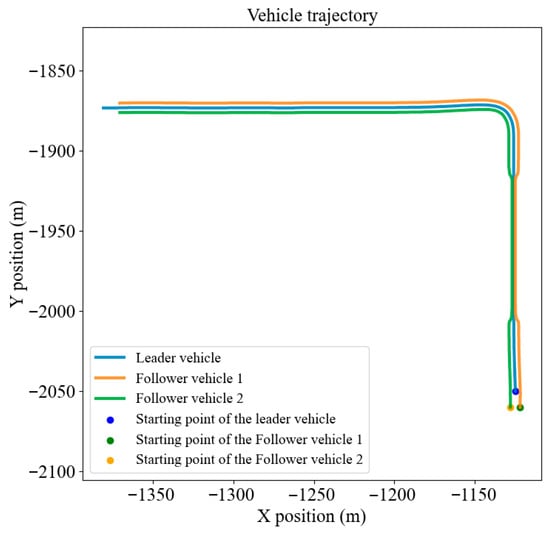

The results of the formation contraction obstacle avoidance experiment are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Formation contraction obstacle avoidance path planning results.

Based on the comprehensive simulation results, the Improved RRT* algorithm demonstrates significantly better path planning performance compared to the traditional RRT and RRT* algorithms. Specifically, the paths generated by the proposed method are shorter and smoother, enabling vehicles to efficiently and stably maintain the predefined formation while navigating through obstacle regions.

6. Research Limitations and Constraints

In this study, effective improved algorithms and strategies are proposed for the path planning problem of deep-sea mining vehicle formations, with their validity verified through simulations. However, constrained by current research conditions and methodologies, this study still has the following limitations:

Firstly, at the algorithm model level, there exists a discrepancy between the environmental modeling in this study and real-world scenarios. The simulation experiments are based on 2D static grid maps, failing to fully simulate the irregularities and dynamic changes in actual 3D deep-sea terrain. Meanwhile, the obstacle avoidance strategy primarily targets static obstacles, and in-depth discussions on real-time avoidance of dynamic obstacles as well as the impact of formation communication delays during this process are still lacking.

Secondly, at the experimental verification level, the validity of the research relies on the preconditions of simulations. Further testing is required to determine whether the computational complexity of the algorithm can still meet real-time requirements in more extreme large-scale environments or larger formations. Additionally, the vehicle model simplifies dynamic characteristics, without considering the specific impacts of complex seabed adhesion and water current interference on trajectory tracking accuracy, which may cause the average error of 3.5–4.2% observed in simulations to vary in practical applications.

Finally, at the system application level, this study assumes idealized sensor perception capabilities. In actual deep-sea environments, sensors suffer from issues such as limited detection range and data noise; integrating perception uncertainty into planning decisions remains a key challenge for future research. Moreover, the current strategy is designed for three-vehicle formations, and its scalability and stability in larger-scale formations need to be verified in subsequent studies.

The above limitations also point out directions for future research, including but not limited to: developing more accurate 3D environmental dynamic models, investigating robust formation control algorithms under constrained communication, and conducting semi-physical simulations or physical experiments to verify the actual performance of the algorithms.

7. Conclusions

This study focuses on the formation operation of deep-sea mining vehicles and proposes an efficient path planning method tailored for formation systems to meet their operational requirements. For the path planning of the lead vehicle, a global RRT* algorithm incorporating formation constraints is designed, addressing the limitations of traditional methods in terms of convergence speed, kinematic constraints, and formation maintenance, while adapting to complex seabed terrains. To solve the coordination challenges of follower vehicles during obstacle avoidance, a local RRT* path planning method based on a formation behavior model is proposed, enabling safe and stable navigation in environments with complex obstacles. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed methods exhibit strong path planning capability and environmental adaptability. Compared with existing approaches, the proposed strategy offers significant advantages in path smoothness, formation coordination, and system robustness, making it well-suited for multi-vehicle cooperative operations such as deep-sea mining. Nevertheless, the algorithm’s adaptability in dynamic ocean environments and variable terrains still requires improvement, and future work may focus on integrating real-time perception and control strategies for further optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and H.W.; Methodology, J.L. and Y.W.; Software, J.L. and H.L.; Validation, Y.W., H.L. and P.H.; Formal analysis, Y.W. and P.H.; Investigation, Y.W. and H.L.; Resources, H.L., B.L. and H.W.; Data curation, Y.W. and P.H.; Writing—original draft, J.L.; Writing—review & editing, P.H., B.L., H.W. and S.Y.; Visualization, H.L.; Supervision, B.L., H.W. and S.Y.; Project administration, B.L. and H.W.; Funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the Collaborative Innovation Research Institute of Ocean Engineering for its valuable academic support and excellent research environment, which were instrumental to the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Du, K.; Xi, W.-Q.; Huang, S.; Zhou, J. Deep-sea Mineral Resource Mining: A Historical Review, Developmental Progress, and Insights. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-G.; Ma, Z.; Lv, R.; Wei, C.; Ma, K. Deep-sea rock mechanics and mining technology: State of the art and perspectives. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1083–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-H.; Yang, J.-M.; Wei, H.-D.; Lu, H.; Tian, X.; Li, X. A localization algorithm based on pose graph using Forward-looking sonar for deep-sea mining vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2023, 284, 114968. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-H.; Yang, J.-M.; Lyu, H.; Sun, P. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of deep-sea mining vehicles on the discharge plumes. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 033358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammell, J.D.; Strub, M.P. Asymptotically Optimal Sampling-Based Motion Planning Methods. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2009.10484v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakita, D.; Mutlu, B.; Gleicher, M. Single-query Path Planning Using Sample-Efficient Probability Informed Trees. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4624–4631. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.-M.; Chen, X.; Liang, X. UAV trajectory planning based on bi-directional APF-RRT* algorithm with goal-biased. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-K.; Jia, X.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Ma, N.; Meng, M.Q.-H. Deep Neural Network Enhanced Sampling-Based Path Planning in 3D Space. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 3434–3443. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.-J.; Shang, H.-Q.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. An efficient RRT-based motion planning algorithm for autonomous underwater vehicles under cylindrical sampling constraints. Auton. Robot. 2023, 47, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.-C.; Xie, H.-B.; Wang, C.; Yang, H. E-RRT*: Path Planning for Hyper-Redundant Manipulators. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 8128–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-D.; Chai, R.-Q.; Chai, S.-C.; Xia, Y.; Tsourdos, A. Design and Practical Implementation of a High Efficiency Two-Layer Trajectory Planning Method for AGV. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Lee, H.H. Adaptive Informed RRT*: Asymptotically Optimal Path Planning with Elliptical Sampling Pools in Narrow Passages. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2024, 22, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-Y.; Wang, Y.-J.; Lu, Y.-F. Formation Control for UAVs based on the Virtual Structure Idea and Nonlinear Guidance Logic. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Automation, Control and Robotics Engineering (CACRE), Dalian, China, 15–17 July 2021; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Jiang, D.-P.; Miao, R.-L.; Li, Y. Formation Control and Obstacle Avoidance Algorithm of a Multi-USV System Based on Virtual Structure and Artificial Potential Field. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Rong, J.-W.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, H.; Duan, S. Spatial-Temporal Fusion Based Path Planning for Source Seeking in Wireless Sensor Network. Int. J. Wirel. Inf. Netw. 2022, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Q.-Z.; Wan, L.; Li, Y.-L.; Jiang, D. Formation control of a multi-AUVs system based on virtual structure and artificial potential field on SE(3). Ocean Eng. 2022, 253, 111148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.-Y.; Peeta, S.; Yang, M.-L.; Wang, J. Cooperative signal-free intersection control using virtual platooning and traffic flow regulation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 138, 103610. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.-D.; Liu, Z.-G.; Song, Y.-G.; Yang, C.; Liang, C. Research on Multi-UAV Formation and Semi-Physical Simulation with Virtual Structure. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 126027–126039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-P.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wang, J. Virtual Streamline Traction: Formation Cooperative Obstacle Avoidance Based on Dynamical Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpin, S.; Parker, L.E. Cooperative leader following in a distributed multi-robot system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat No02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 2993, pp. 2994–3001. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Y.B.; Lim, Y.H.; Ahn, H.S. Distributed Robust Adaptive Gradient Controller in Distance-Based Formation Control with Exogenous Disturbance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 2868–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.-H.; Peng, Z.-H.; Wang, H.-L.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Li, T. Extended-state-observer-based distributed model predictive formation control of under-actuated unmanned surface vehicles with collision avoidance. Ocean Eng. 2021, 238, 109587. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.-Y.; Ma, Y.-J.; Jiang, B.; Mao, Z. Distributed adaptive fault-tolerant formation control for heterogeneous multiagent systems under switching directed topologies. J. Frankl. Inst. Eng. Appl. Math. 2022, 359, 3366–3388. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.-J.; Wen, G.-H.; Yu, X.-H.; Wu, Z.-G. Distributed Formation Navigation of Constrained Second-Order Multiagent Systems with Collision Avoidance and Connectivity Maintenance. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.N.; Zhu, F.L.; Xu, D.Z. Event-Triggered Bipartite Time-Varying Formation Control for Multiagent Systems with Unknown Inputs. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 5904–5917. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-F.; Wu, X.-X.; Xie, Y.-F.; Guo, B.; Yan, J. Fully distributed adaptive time-varying formation control of singular multiagent systems. Neurocomputing 2023, 516, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Xie, L.H.; Li, X.L. Integrated Relative-Measurement-Based Network Localization and Formation Maneuver Control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.-K.; Li, S.-L.; Guo, G.; Yuan, P.; Bai, J. Formation control of UAV-USV based on distributed event-triggered adaptive MPC with virtual trajectory restriction. Ocean Eng. 2024, 294, 116850. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Wang, N.-Y. Current status and prospects of forestry and grassland special robot swarm technology. For. Mach. Woodwork. Equip. 2023, 51, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, G.-P.; Zhang, D.-W. A leader-follower formation strategy for networked multi-agent systems based on the PI predictive control method. In Proceedings of the 2021 40th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 4763–4768. [Google Scholar]

- Lagunas-Avila, J.; Castro-Linares, R.; Alvarez-Gallegos, J. Obstacle avoidance in leader-follower formation using artificial potential field algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 18th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computing Science and Automatic Control (CCE 2021), Mexico City, Mexico, 10–12 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.-L.; He, S.-D.; Cai, H.; Yang, C. Adaptive Leader-Follower Formation Control of Underactuated Surface Vehicles with Guaranteed Performance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 1997–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.-N.; Li, Q.; Song, R.-Z.; Zhang, Z. Leader-follower time-varying output formation control of heterogeneous systems under cyber attack with active leader. Inf. Sci. 2022, 585, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.H.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, M.; Park, J.-I.; Kim, K.-S. The Leader-Follower Formation Control of Nonholonomic Vehicle with Follower- Stabilizing Strategy. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-Z.; Yang, Q.-K.; Xiao, F.; Fang, H.; Chen, J. Linear formation control of multi-agent systems. Automatica 2025, 171, 111935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Q.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, K.; Deng, C.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Z. Motion Planning of 6R Manipulator with Improved RRT* Algorithm. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 43, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, F.; Wu, Y.; Han, B.; Luo, L.; Biancardo, S.A. MFMDepth: MetaFormer-based monocular metric depth estimation for distance measurement in ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 207, 111325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, C.; Fan, T.; Lau, H.C.; Yan, X. Predictive modelling for vessel traffic flow: A comprehensive survey from statistics to AI. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2025, 7, tdaf022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.Q. Research on Path Planning and Formation Control of Unmanned Vehicles in Forest Environment. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.