Abstract

The Strait of Gibraltar (SG) is a key biogeographic and ecological corridor connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, enabling the seasonal migrations of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus). The objective of this study was to characterize, for the first time, the spatial and temporal exposure of the species to maritime traffic during its migration through the SG, quantifying movement patterns, individual composition, and collision risk to identify critical areas for conservation. Validated observations collected between April 2016 and October 2024, with additional records in January and March 2025, were integrated with EMODnet vessel density layers to assess monthly distributions of sightings, individuals, calves, migration patterns, and behavior. A total of 347 sightings comprising 692 individuals were recorded, revealing predominantly westward movements between June and August. Spatial overlap analyses indicated that the highest exposure occurred both near the Bay of Algeciras/Gibraltar and in the northern half of the Central SG, where cargo ship and tanker traffic coincides with dense migration routes and where injuries have been documented in the field. These findings delineate high-risk areas for fin whales throughout the SG and provide an empirical basis for spatial management measures, including speed reduction zones, adaptive route planning, and the possible designation of the area as a cetacean migration corridor. The proposed measures aim to mitigate collision risk and ensure long-term ecological connectivity between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), classified as an endangered species and legally protected in many regions, is the second largest animal on the planet after the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) [1,2]. As a keystone species from both an evolutionary and ecological perspective, it plays an important role in marine ecosystems and warrants detailed research to improve understanding of its migratory behavior and exposure to human pressures.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are one of the main tools for cetacean conservation, but their effectiveness can be limited by the extensive movements of migratory species such as large whales [3,4]. Fin whales undertake long-distance seasonal migrations between high-latitude feeding grounds and temperate or subtropical breeding grounds [5,6,7]. These migrations promote genetic exchange and population resilience [8] and are primarily driven by the spatial and seasonal availability of prey [9].

In the North Atlantic, fin whales feed during the summer in highly productive regions such as the Gulf of Maine and Icelandic waters [10,11]. In the Mediterranean, the species is the largest and most frequently observed mysticete [12], represented by a predominantly resident population that makes seasonal movements between the Ligurian-Provençal basin and southern wintering grounds [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Genetic and isotopic analyses have demonstrated limited connectivity between the Northeast Atlantic North (NENA) and Mediterranean populations [20].

However, a small fraction of the NENA population migrates seasonally through the Strait of Gibraltar (SG) to the Alboran Sea [21], and further north to the Catalan coast [22] and the Balearic Islands [23]. In these areas, individuals from the NENA migratory population and the resident Mediterranean population may overlap geographically during the spring, although there is no evidence of demographic or genetic exchange. This overlap most likely reflects temporary ecological coexistence, consistent with the distinctive ecological and spatial characteristics of the Mediterranean population, which are determined by regional oceanographic dynamics and localized feeding habitats [24,25].

From these areas, some individuals move northeast toward the Ligurian Sea [22], while others travel southwest along the Iberian coast, from El Garraf (41.25° N, 1.88° E; southwestern coast of Barcelona, Catalonia) and Dénia (38.8° N, 0.1° E; northern coast of Alicante, Spain)—back toward the SG, completing this transit in approximately 73.5 h [26]. The subsequent return migration during the summer takes individuals to the North Atlantic, including the Azores and the northwest coast of Spain, as demonstrated by stable isotope data [27]. Recent photo-identification and satellite tracking studies have confirmed recurring connections between key feeding areas, such as El Garraf and northwestern Spain, demonstrating that the SG functions as a critical migratory bottleneck linking both basins [28,29].

1.2. Anthropogenic Pressures and Ship-Strike Risk in the Strait of Gibraltar

Mediterranean fin whales are subject to multiple anthropogenic pressures that compromise their conservation, including the depletion of their prey due to ocean warming, habitat degradation, underwater noise, interactions with fishing, and exposure to pollutants and heavy metals [16,17,30,31,32,33]. Among these factors, collisions with boats represent the main cause of human-induced mortality, especially in continental shelf waters [19,30,34,35,36,37,38,39].

The risk of collision has been widely documented throughout the northern Mediterranean [40,41,42,43]. Conversely, recent research in the SG has revealed that comparable pressures also occur in this region, where intense maritime traffic overlaps with critical habitats for cetaceans [44]. Within the northern basin, high-density shipping corridors and feeding areas, such as the Pelagos Sanctuary, have shown substantial collision risks [45]. For example, in 2018, 24 of the 58 recorded strandings showed evidence of fatal collisions with ships [41,46]. Along El Garraf coast, another key feeding area, cargo ships have been identified as the category of vessels posing the highest collision risk [42]. During the summer, when prey availability and warmer waters attract whales to localized feeding areas [12,18,47], increased maritime traffic further amplifies the likelihood of collisions [30].

Occasional strandings and necropsy records along the Andalusian coast between 2007 and 2024 provide evidence of recurrent incidents of ship strikes affecting fin whales [48,49,50,51]. However, studies addressing these interactions in the southern basin, remain scarce despite intense maritime activity [19,21,49].

The SG is one of the world’s most important shipping corridors, connecting the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. It supports intense international shipping, with an estimated annual traffic of between 110,000 and 120,000 vessels, equivalent to approximately 10% of global maritime trade ([52,53,54]; Salvamento Marítimo, VTS Tarifa Traffic, 2018–2019 in [44]). This passage hosts a continuous flow of merchants, passenger, fishing, and recreational vessels, with an average of 5.8 transits per hour, or more than 140 per day. This density makes the SG one of the most congested maritime corridors in the world and highlights its ecological sensitivity as a critical area where maritime activity and cetacean migration routes overlap.

Ferry and merchant shipping routes between Spain and North Africa, combined with recreational and fishing activities, contribute to the continuous presence of vessels and high levels of underwater noise [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The SG overlaps with the feeding and migration habitats of several cetacean species [63,64] and serves as a seasonal transit route for fin whales [21,44]. Consequently, migratory routes in this region are likely to intersect with major shipping lanes and other human activities, increasing the risk of vessel collisions, entanglement, and acoustic disturbance [55,57,60]. Recent analyses indicate that the migration corridors of large whales may overlap with major shipping routes by up to 91.5% [65], highlighting the need for a quantitative assessment of the spatiotemporal overlap between whales and shipping traffic, a central objective of this study [19,42].

Given these patterns of overlap between migration routes and maritime activity, it is essential to assess the spatial and temporal exposure of fin whales in the SG to guide evidence-based mitigation and management strategies.

1.3. Conservation and Legal Context

The fundamental ecological function of the SG is reflected in the conservation status of the fin whale and the protection frameworks established for its populations. The Mediterranean population of Balaenoptera physalus is listed as Endangered, and the Northeast North Atlantic population as Vulnerable, by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [1,2]. At the European level, the species is protected under the Habitats Directive (Annex IV) and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Furthermore, international agreements such as the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Eastern Mediterranean Sea and the Adriatic Sea (ACCOBAMS) emphasize the necessity of coordinated conservation actions across the Mediterranean and Atlantic basins. In the context of Spanish waters, the regulatory framework is further reinforced by Royal Decree 1727/2007, which establishes protective zones surrounding cetaceans, and

Royal Decree 139/2011, which classifies the fin whale as both threatened and vulnerable. Across the Mediterranean, several Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have been designated for cetaceans, with some of these explicitly targeting fin whales [19]. Within the SG, there are multiple protected zones under the jurisdiction of both Spain and the United Kingdom, each with varying levels of protection. This legal framework underscores the recognized conservation importance of the SG and supports the implementation of spatially explicit management measures to mitigate anthropogenic pressures such as ship strikes and underwater noise.

1.4. Aims of the Study

The present study characterizes for the first time the spatial and temporal exposure of fin whales during their migration through the SG, integrating nine years of opportunistic and dedicated vessel-based observations [29]. Through a combined analysis of whale sightings and maritime traffic density, the study assesses the species’ exposure to different types of vessels and identifies priority areas for collision-risk management and conservation.

The main objective is to characterize the spatial and temporal exposure of the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) during its migration through the SG, integrating biological and maritime traffic data to identify critical areas of risk and relevance for conservation.

Specific objectives:

- Quantify and georeference fin whale sightings, identifying seasonal patterns of presence and movement.

- Evaluate the directionality and behavioral patterns (feeding, transiting, or stationary) of fin whales during migratory periods.

- Develop a spatial collision-risk map to identify priority areas for maritime-traffic management and species conservation.

This framework provides an evidence-based foundation for delineating ecological corridors and prioritizing management measures aimed at mitigating anthropogenic pressures on fin whales and maintaining the functional connectivity of the SG ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: The Strait of Gibraltar

The SG is the natural connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and represents a region of exceptional biological and oceanographic importance. At its narrowest point (14.4 km between Punta de Tarifa, Spain, and Punta Cires, Morocco), the SG comprises two sectors: a deeper, narrower eastern channel and a wider, shallower western basin (Figure 1). This constriction regulates the exchange of water masses between both basins [66,67,68,69,70]. At the surface, an eastward inflow of Atlantic origin—composed mainly of Surface Atlantic Water (SAW) and North Atlantic Central Water (NACW)—enters the Mediterranean as the Atlantic Jet (AJ), with typical core velocities of 1.0–1.2 m s−1 and peaks exceeding 2.0 m s−1 during easterly (Levante) wind events or tidal amplification [71]. A compensatory westward deep outflow transports denser, cooler, and saltier Mediterranean water toward the Atlantic, maintaining the basin’s negative water balance [72,73,74,75].

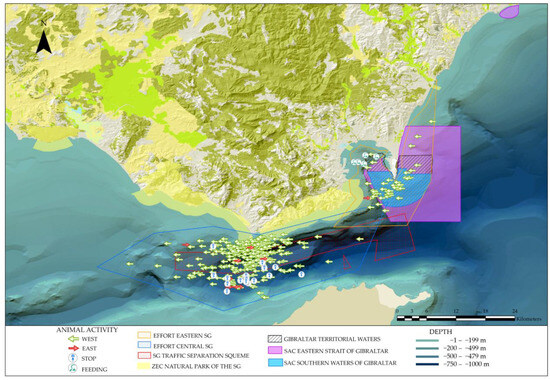

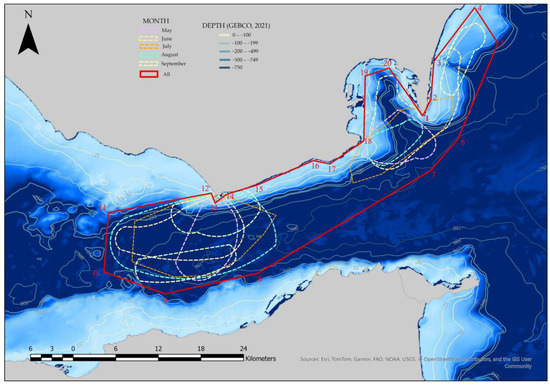

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution and activity of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) recorded in the SG (2016–2025). Arrows indicate migratory direction (westward or eastward), while circles represent stationary or feeding-compatible behavior. Polygons denote survey effort areas and existing marine protected zones. Bathymetry from [76].

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected by two independent entities. The first Turmares Tarifa (Tarifa, Spain), conducted opportunistic whale-watching operations in the Central Strait of Gibraltar (Central SG), using two vessels measuring 19 m and 17 m in length, which operated between April 2016 and October 2024. The second dataset was collected by Ecolocaliza (La Línea de la Concepción, Spain) though non-systematic surveys conducted in the Eastern Strait of Gibraltar (Eastern SG), departing from La Línea de la Concepción and Sotogrande (Cádiz, Spain), using an 8 m motor vessel (200 hp) and a 14 m sailboat (70 hp). These surveys were conducted between May 2016 and October 2024, with one additional sighting recorded in January 2025 and two in March 2025. In both cases, two trained ob servers equipped with binoculars Fujinon 7 × 50 (Fujifilm Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) were positioned on the vessel bridge, continuously scanning to port (360–180°) and starboard (0–180°) whenever sea-state conditions were Beaufort 4 or lower. In the eastern SG, data were logged using Logger software, version 2010 (International Fund for Animal Welfare—IFAW, Yarmouth Port, MA, USA), whereas in the central SG, data were recorded manually without systematic effort information.

For each sighting, both entities recorded the following parameters: contact time, geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) at the beginning and end of the sighting, wind speed and direction, sea state, number of individuals, group composition, behavioral state, animal heading, and photographs.

The resulting dataset comprised georeferenced observations of fin whale groups, including behavioral and environmental variables. These biological data provided the empirical foundation for modeling whale movement routes and quantifying their spatial overlap with maritime traffic in subsequent analyses.

2.3. Maritime Traffic and Data Analysis

Vessel density maps were obtained from the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) Human Activities Data Portal [77] (Cogea srl, Rome, Italy; funded by the European Commission’s Directorate–General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE); available online: www.emodnet-humanactivities.eu, accessed on 21 March 2025). These maps describe the spatial distribution of maritime traffic derived from Automatic Identification System (AIS) data collected by terrestrial and satellite receivers [78]. AIS is mandatory for passenger vessels and for cargo ships ≥ 500 gross tons (GT) on domestic routes and ≥300 GT on international voyages, as established under Spanish Royal Decree 210/2004 [79].

Monthly raster layers (1 km2 resolution) representing vessel density for six activity types—tanker, cargo, passenger, high-speed craft, pleasure, and fishing—were extracted from EMODnet for May to September (2017–2023) [80]. Raster processing and averaging were conducted in R version 4.5.0 [81] (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), using the raster package.

The migration routes of fin whales reconstructed from field observations were used to quantify exposure to maritime traffic within the SG. Straight-line routes were generated between the start and end positions of each sighting in ArcGIS Pro version 3.4.3 [82] (Esri Inc., Redlands, CA, USA), with 1 km buffers applied around each track to account for potential navigation deviations [83,84]. Mean vessel density per grid cell, excluding port areas, was extracted using the “Zonal Statistics as Table” tool in ArcGIS Pro, version 3.4.3 (Esri Inc., Redlands, CA, USA).

Given the difference in survey effort between the eastern (49 routes) and central (298 routes) datasets, a correction factor (CF) was applied following previous methodologies [85,86]:

where is the distance traveled alongside fin whales (from first contact to end of sighting) and is the total distance surveyed in subarea .

The Corrected Density by Area () was calculated as:

where is the original vessel density, is the fragment area (km2), and is the correction factor.

Finally, the Estimated Total Exposure (ETE) was obtained as:

Accordingly, exposure was quantified as a function of maritime traffic intensity—represented by the density values of the EMODnet raster layers—combined with the spatial extent of route–traffic overlap and normalized by survey effort across the study grid. Because the EMODnet rasters do not provide information on the mean operating speed of each vessel class, representative speed estimates were derived from a targeted literature review and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average speed of vessel types analyzed in this study.

It is imperative to acknowledge the profound implications of maritime traffic on cetacean conservation, particularly in regions characterized by intense vessel activity, such as the SG. This issue assumes particular significance for large cetaceans, including fin whales, as they are highly susceptible to the adverse effects of such activities. In order to maintain analytical consistency despite the differences in survey effort between the datasets, only sightings in which whales exhibited migratory behavior—characterized by consistent eastward or westward headings—were selected for analysis. Fin whales typically follow linear, directed migratory paths [92,93], which increases their likelihood of interacting with vessels in high-traffic areas [92]. For each sighting, a straight-line route was drawn between the initial and final positions, and the distance traveled by individuals during the encounter was calculated.

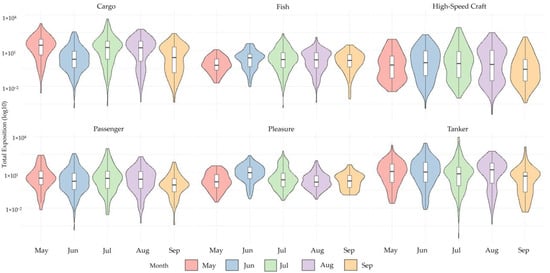

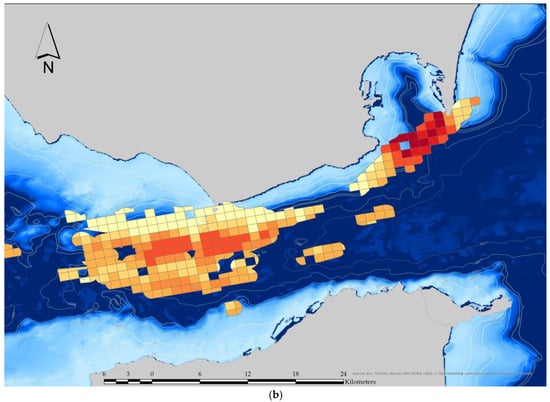

Subsequently, patterns of spatial and temporal exposure across vessel categories and months were examined using violin plots on a logarithmic scale, thereby enhancing the visualization of distributional differences. Statistical comparisons among vessel types were performed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise contrasts when significant. Adjusted p-values were computed using the Bonferroni correction to control Type I error. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.5.0 [81] with Dunn. Test package [94].

3. Results

A total of 26,179.7 km was surveyed in the Eastern SG, where 49 sightings comprising 110 individuals were recorded. In the Central SG, 9358 sightings were conducted, of which 298 corresponded to fin whales (582 individuals). Surveys covered the period April–October (2016–2024), with one additional sighting in January 2025 and two in March 2025.

To visualize the spatial coverage and fin whale distribution, two polygons were generated—one centered on the recorded survey routes in the Eastern SG and another encompassing all multi-species sightings in the Central SG. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of fin whale sightings, migratory directions, and behavioral classifications (feeding, stationary, or migrating), together with the survey areas and main protected zones in the region.

Out of a total of 692 fin whale individuals recorded during the study period, 10 (1.4%) were observed migrating eastward, 660 (95.4%) westward, 17 remained stationary or moved slowly without a defined heading, and five exhibited feeding-compatible behavior—specifically lunge feeding, characterized by the engulfment of large volumes of water subsequently filtered through the baleen plates [95,96,97]. Additionally, zigzag diving movements within a 1–2 km radius were documented, a pattern previously described for this species during foraging events [98]. Two whales were re-sighted during consecutive observations in August 2021 and March 2025, indicating repeated use of the same area. The main protected areas represented in Figure 1 include the Spanish Eastern SG Special Area of Conservation (Eastern SG SAC) [99], the Southern Waters of Gibraltar SAC [100], and the Natural Park of the Strait [101].

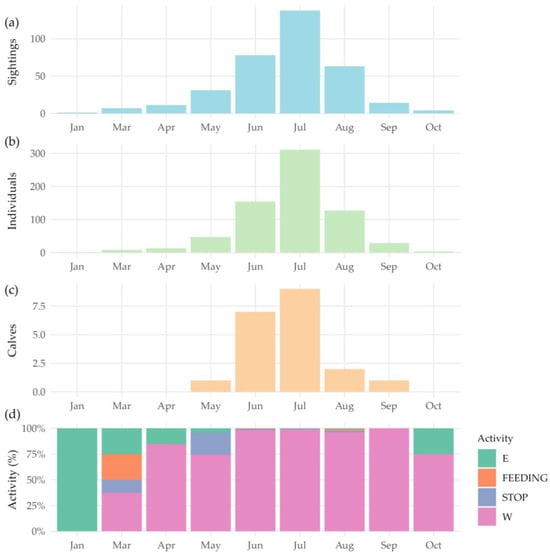

Sightings were classified by month, including all months studied except February, November, and December, which were not sampled. A steady westward migration was observed between April and October, with a pronounced peak between June and August, in groups of between 1 and 7 individuals, 19 of which included calves (Figure 2a–c). Movements towards the east, towards the Mediterranean, were recorded in small numbers throughout the months monitored, either in the form of solitary individuals or in pairs, with no calves observed (Figure 2d). In January, only one sighting was recorded, corresponding to an individual moving eastward.

Figure 2.

Monthly distribution of sightings and characteristics of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) recorded in the SG during the study period. (a) Monthly distribution of the number of sightings, (b) Monthly distribution of the total number of individuals observed, (c) Monthly distribution of recorded calves, (d) Monthly proportion of activity types (westward movement, eastward movement, stationary behavior, and feeding). February, November, and December were not surveyed. In January, only one eastward-moving individual was recorded. The predominance of westward movements reflects the concentration of survey effort during spring and summer, while the main eastward migration into the Mediterranean likely occurs in the unsampled winter months.

In some cases, individuals were observed stationary on the surface without a defined course or showing changes in direction within the same location, which made it impossible to confirm their feeding behavior. This stationary behavior, although infrequent, was recorded most often in May (Figure 2d). Throughout the study period, most individuals were recorded moving towards the Atlantic, with the highest presence of adults, juveniles, and calves (Figure 2c,d).

The predominance of westward movements probably reflects the period in which the study was conducted, which focused mainly on the spring-summer period, when fin whales return to the North Atlantic, while the main migration from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean occurs during the winter months, which were not included in the study. The lack of winter data, with only one record in January, is due to the temporary cessation of whale watching operations by SG Central and adverse weather conditions during that period. In addition, fin whales entering the Mediterranean during the winter are less likely to be detected, as they tend to cross the strait across its entire width rather than close to the coast. Therefore, the apparent imbalance in directional records is better explained by the temporal and spatial limitations of the study’s coverage than by an inherent asymmetry in the migratory behavior of fin whales.

As shown in Figure 3, both the distance traveled by fin whales and the number of recorded encounters increased markedly from April, peaking in July. During this month, routes effort exceeded 400 km, while sightings surpassed 150 records, reflecting a high density of fin whales within the study area. Most movement trajectories were concentrated between June and August, with distances traveled consistently exceeding the number of encounters, suggesting prolonged individual presence or extended monitoring periods during these months. Following this peak, both parameters gradually declined, returning to baseline levels by September and October, similar to those observed at the beginning of the year.

Figure 3.

Monthly distribution of survey effort in kilometers recorded during sightings (blue bars) and the number of sightings recorded (red bars) throughout the year during fin whale migration in the SG.

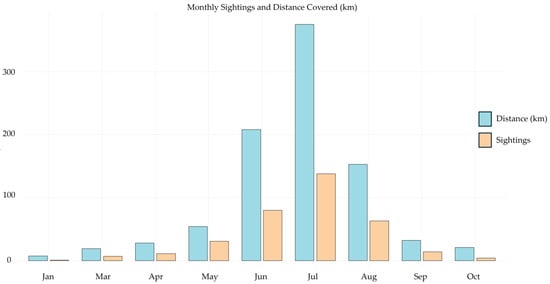

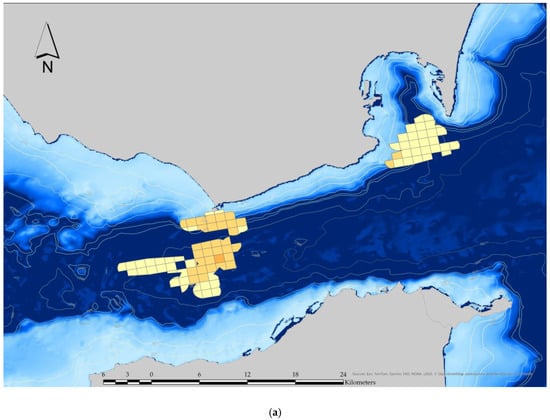

The spatial integration of whale sighting routes with EMODnet vessel-density data revealed high exposure areas in the northern and eastern sectors of the Strait, particularly near the Bay of Algeciras/Gibraltar and along the Spanish coast (Figure 4). These zones coincide with intense cargo and tanker vessel traffic, as confirmed by the exposure analysis.

Figure 4.

Monthly maps of fin whale exposure to maritime traffic (May to September) by vessel type (passenger, tanker, pleasure, fishing, cargo, high-speed craft). Note the differences in the scales.

Total exposure values exhibit a strongly skewed distribution, with a high concentration of low values and the presence of extreme outliers. Representing these values on a linear scale compress most of the data toward the lower range, limiting the ability to visualize and compare meaningful variations. To overcome this limitation, a violin plot was created using a base-10 logarithmic transformation (log10) of the exposure values prior to plotting. This transformation reduces the disproportionate influence of extreme values while expanding the scale for low and medium values, allowing for better discrimination and visualization of variability in exposure (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Violin plot showing total exposure distribution by vessel type and month (log scale).

To highlight the months and vessel types associated with the lowest and highest total exposure, fishing activity was depicted as the example of minimal exposure (Figure 6a), whereas cargo vessel activity in July was shown as the example of maximal exposure (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Months and vessel type: (a) lowest total exposure (fishing in May) and (b) highest total exposure (cargo in July).

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed highly significant differences across all months (KW May = 355.196, KW June = 148.315, KW July = 140.305, KW August = 128.730, KW September = 37.400; p < 0.001), which justifies the application of the Dunn post hoc test to evaluate pairwise comparisons between vessel types (Table 2). Significant temporal and inter-type differences in exposure were detected. In May, cargo vessels exhibited statistically significant higher exposure compared to other types of vessels, with the greatest contrast observed in relation to high-speed craft vessels (mean difference = 16.14; p < 0.001), followed by fishing (9.67; p < 0.001), passenger, and pleasure vessels. No significant difference was found with tanker vessels. In June, pleasure vessels showed significantly higher exposure compared to the remaining vessel types (mean difference = 3.64; p < 0.019). In July, cargo vessels again displayed significantly elevated exposure relative to all other types. During August, cargo vessels maintained significant differences with most types of vessels, except tankers, where differences were non-significant. Finally, in September, pleasure vessels exhibited significantly higher exposure compared to high-speed craft and passenger vessels.

Table 2.

Dunn post hoc test results from May to September. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

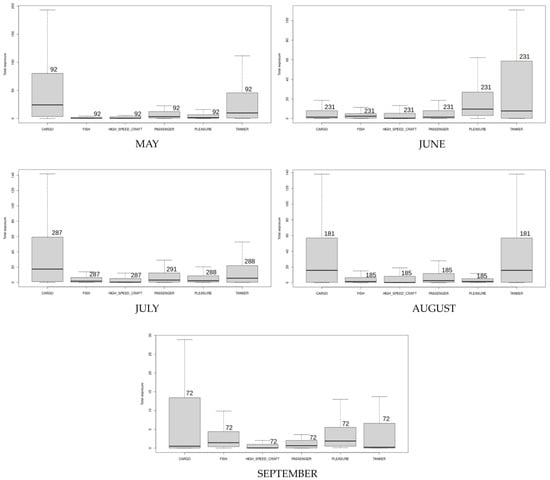

Boxplots of total exposure by vessel type from May to September are presented in Figure 7. In May, cargo and tanker vessels exhibited the highest total exposure, followed by pleasure and passenger vessels. In June, tanker and pleasure vessels showed the greatest exposure, followed by cargo and passenger vessels. In July, cargo vessels again stood out, followed by tankers and passenger vessels. In August, cargo and tanker vessels showed the highest exposure, followed by passenger and high-speed craft. In September, pleasure vessels displayed the highest total exposure values.

Figure 7.

Boxplots of total exposure by vessel type for the months of May to September.

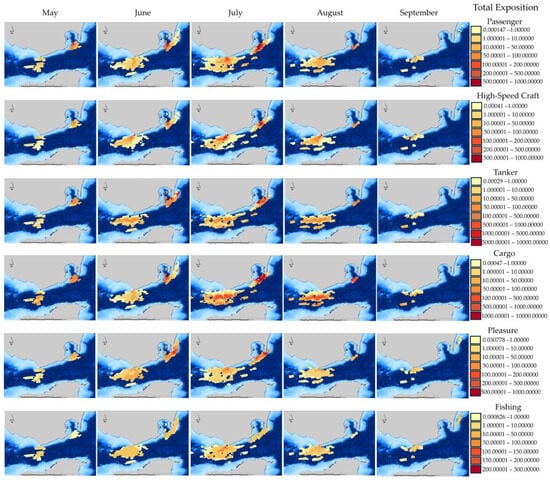

Proposal for a High-Risk Collision Area for Large Merchant Vessels and Ferries

Building on the results outlined above—particularly the spatial distribution of fin whale sightings and the navigation routes of large vessels within the EG—we recommend the formal designation of a Critical Collision Risk Area. Such a designation would allow the competent Environmental Authorities, under the oversight of the SG Maritime Authorities, to require that large vessels station a trained lookout on the bow, equipped with appropriate binoculars and capable of detecting whale blows. Upon identification of a potential collision risk while transiting the designated area, the lookout shall promptly notify the bridge, initiating an immediate reduction in vessel speed and, where practicable, the implementation of measures to mitigate underwater noise.

We therefore propose an irregular polygon encompassing an area of 502.22 km2 (Figure 8), defined by the following geographic coordinates: 1 (36.1101° N; 5.3449° W), 2 (36.1412° N, 5.3347° W); 3 (36.1817° N; 5.3308° W), 4 (36.2355° N; 5.2739° W), 5 (36.2026° N; 5.2565° W), 6 (36.0816° N; 5.3103° W), 7 (36.0376° N; 5.3429° W), 8 (35.9120° N; 5.5631° W), 9 (35.8884° N; 5.6778° W), 10 (35.9154° N; 5.7482° W), 11 (35.9849° N; 5.7414° W), 12 (36.0115° N; 5.6143° W), 13 (36.0012° N; 5.6015° W), 14 (36.0077° N; 5.6029° W), 15 (36.0173° N; 5.5616° W), 16 (36.0467° N; 5.4882° W), 17 (36.0504° N; 5.4262° W), 18 (36.0761° N; 5.4268° W), 19 (36.1637° N; 5.4104° W), 20 (36.1637° N; 5.3773° W). This measure will enhance the management, environmental surveillance, protection, and conservation of the species during its passage through the EG—a critical bottleneck characterized by exceptionally dense maritime traffic and a heightened risk of vessel collisions.

Figure 8.

Map of areas of high maritime traffic exposure by month.

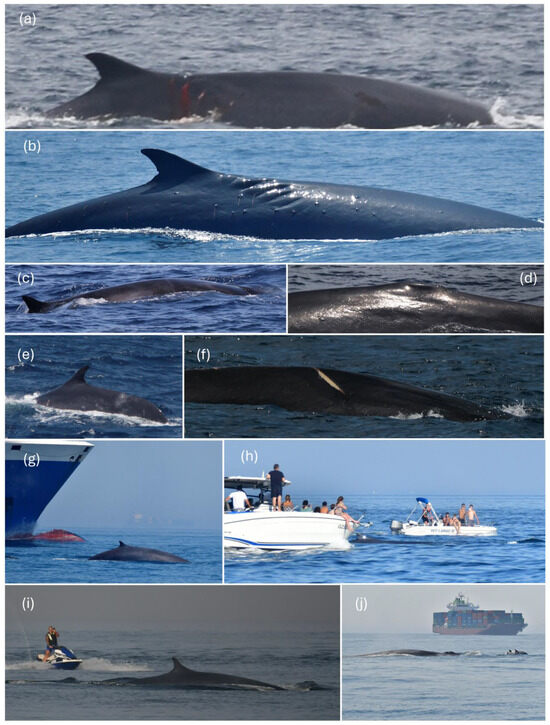

Throughout the study period, a substantial exposure of fin whales to maritime traffic within the SG has been documented, particularly during the summer months, when the intensity of cargo, tanker, pleasure, and passenger vessel traffic reaches its peak. This spatial and temporal overlap with major navigation routes and anchorage zones—especially along the northern coast of the Strait, including the Eastern SG SAC and adjacent areas—markedly increases the risk of adverse interactions. Indeed, several individuals have been observed bearing fresh lacerations or healed linear scars on the dorsal surface and caudal peduncle, as well as mutilations consistent with collisions involving propellers or hull structures, in addition to multiple instances of harassment and near-collision trajectories by vessels (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) Fresh parallel lacerations; (b) subsequent scar formation in the same individual; (c) fin whale calf entangled in a fishing line; (d) dorsal fin mutilation; (e) single scar on the caudal peduncle; (f) simple cut and abrasion on the dorsal surface; (g) near-miss event involving a ferry; (h) harassment by recreational vessels; (i) jet-ski disturbance; (j) collision course with a container ship. All images were captured during the study period in the SG.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first spatially explicit quantification of the exposure of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) to different categories of vessels in the SG, an important migratory bottleneck connecting the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Exposure patterns showed pronounced seasonal and spatial variability (Figure 4), with maximum values between June and September, coinciding with the peak westward migration (Figure 8). These results indicate that fin whales experience the highest cumulative risk from shipping traffic during their return to the North Atlantic, where groups are largest and calves are present.

The highest average exposure occurred along the northern and central sectors of the SG, where cargo and tanker routes run parallel to the coast and overlap with the main migration corridor, substantially increasing the probability of collision. High exposure was also detected at the entrance to the Bay of Algeciras/Gibraltar, an area characterized by dense ship maneuvering associated with port operations and ferry traffic. Together, these sectors represent critical areas of spatial overlap between the movements of fin whales and major shipping routes, covering both deep-water shipping lanes and high-frequency crossings between Algeciras, Tarifa, and Tangier. This configuration highlights the cumulative nature of anthropogenic pressures within the SG and underscores the need for site-specific management measures focused on dynamic speed regulation, route optimization, and real-time monitoring within high-exposure areas, particularly within and around the eastern SG SAC and the southern waters of Gibraltar.

Cargo ships and tankers dominated the total exposure due to their continuous presence and extensive routes, but passenger ships and high-speed craft, although spatially more limited, created localized high-risk areas near port entrances and the eastern sector. Reduced reaction time at high speeds (>15 knots) significantly increases the likelihood of fatal encounters, as detection and evasion capabilities decrease dramatically [34,102,103]. A 50% reduction in lethality has been reported at 8.8 knots [103,104]. Large vessels can cause fatal injuries at any speed [103,105], while the risk posed by medium-sized vessels depends on hull design and mass [106]. Whales typically exhibit avoidance behavior below 10 knots (~18 km h−1), which is considered a critical threshold for effective evasion and risk reduction [107]. Furthermore, avoidance effectiveness improves at speeds <5 knots and on steady courses, minimizing acoustic stress and the probability of impact [108]. These empirical thresholds highlight the need for dynamic speed management in areas of seasonal whale aggregation.

The intensity of noise generated by ships, which is directly related to their speed, represents an additional cumulative stress factor [109]. Anthropogenic noise can alter the migratory behavior of whales by disrupting communication between conspecifics and reducing navigation efficiency through the mechanisms described by the “many-misses principle” [110,111,112]. Fin whales and other baleen whales produce low-frequency, high-intensity calls that propagate over hundreds of kilometers, enabling long-distance coordination and contact between migrating individuals [113,114,115]. Elevated noise levels can mask or degrade these signals [116,117,118], reducing cohesion and increasing energy costs. When critical thresholds are exceeded, whales may actively avoid noise sources (negative phonotaxis), resulting in route deviations or interruption of migration [119]. In the GS, recent measurements have recorded underwater noise levels exceeding 120 dB re 1 µPa [120,121], surpassing the behavioral disturbance thresholds identified in other baleen whales [122,123]. Furthermore, Ref. [16] documented a decrease in the presence of fin whale songs under high noise conditions, supporting the hypothesis of chronic acoustic interference during migration. Therefore, it is likely that the combination of intense shipping traffic and sustained acoustic pressure impairs orientation, communication, and energy efficiency throughout the corridor.

Recreational and small-scale fishing vessels add even more pressure, especially in June and September, when both whale abundance and leisure activities peak. The highest concentrations were recorded in Bay of Algeciras/Gibraltar and in the Eastern SG SAC/Southern Gibraltar Waters SAC, where whale watching, tuna fishing, and coastal navigation overlap [124]. The regional nautical infrastructure includes approximately 4000 moorings distributed among nearby marinas [57]. Most recreational and artisanal vessels (<15 m) lack AIS tracking [125], resulting in underrepresentation in official density layers and an underestimation of their true impact. Observed cases of harassment and close approaches (Figure 9h,i) are consistent with previous reports of behavioral disturbances in local dolphin populations [60,61,126,127]. Fishing activity was low in summer but increased in September [128]; however, two entanglements of calves in trolling and bottom long line gear (Figure 9c) illustrate the incidental threats from small-scale fishing [129,130].

The spatial coincidence between high fin whale density and intense vessel activity confirms that the risk of collision in the SG is mainly seasonal and concentrated along the main migration corridor. A similar spatial coupling has been documented in the Pelagos Sanctuary [45], but exposure levels in the SG appear higher due to continuous, bidirectional traffic and limited opportunities for lateral avoidance. Unlike the northwestern Mediterranean, where Pelagos, the Cetacean Migration Corridor, and the IMO-designated PSSA for 2023, together with the enforcement of mandatory speed limits [30,131,132,133,134,135,136], have already established protection frameworks, the SG remains an unprotected but functionally critical gateway linking the two basins.

Given the high exposure detected, mitigation strategies adapted to local conditions are urgently needed. Seasonal speed restriction zones (<10 knots) could halve the risk of mortality [102,103], while diversion measures could reduce the spatial overlap between deep-draft shipping routes and whale corridors [30,137]. Real-time monitoring systems, combining coastal cameras or hydrophones with alert platforms such as AVISO [138,139], would enable early detection and communication with vessels, improving avoidance capacity. The SG meets the ecological and regulatory criteria to be designated a Cetacean Migration Corridor, Marine Protected Area, or PSSA under the Barcelona Convention and IMO guidelines. Extending formal protection to this access route would harmonize the conservation of fin whales throughout their migration area and benefit other vulnerable megafauna—sperm whales, orcas, sea turtles, and resident dolphins—reinforcing the strategic role of the SG as the main ecological bridge between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

Policy Relevance

The results presented here provide quantitative evidence of a critical overlap between maritime traffic and fin whale migration in the SG, identifying specific areas of high exposure where mitigation would be most effective. These findings directly support the implementation of dynamic, evidence-based management tools—speed regulation, route optimization, and real-time tracking—that have already been adopted in other parts of the Mediterranean but have not yet been implemented in this key transit area. The integration of the SG into the existing Mediterranean network of protected migration corridors would represent a cost-effective and regionally coherent step towards reducing vessel collision mortality and achieving international conservation objectives under the Barcelona Convention and the IMO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E. and J.C.G.-G.; methodology, R.E.; software, D.P.D.; validation, R.E., P.G.-V., I.A.F. and L.O.-P.; formal analysis, D.P.D.; investigation, R.E., P.G.-V., I.A.F. and E.M.-M.; resources, E.M.-M. and J.C.G.-G.; data curation, P.G.-V., I.A.F. and L.O.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.; writing—review and editing, R.E. and E.M.-M.; visualization, R.E.; supervision, J.C.G.-G. and D.P.D.; project administration, L.O.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Spanish legislation (Real Decreto 1727/2007) and the Marine Regulations 2014 of Gibraltar and was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Education, Heritage, Environment, Energy and Climate Change in Gibraltar. All observations were strictly non-invasive and did not involve capture, handling, or disturbance of whales.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are not publicly available, as they form part of an ongoing research project. Requests for access to the data should be directed to rocioespada80@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the crew of Turmares Tarifa for their essential support, which enabled the successful execution of this project. We also extend our sincere thanks to Luisa Haasova, Carolina Segovia Smith, Maria del Carmen Benítez Sody, Mario and Fico Jiménez Galeote, all participants in the PRCEO project, and Alessia Scuderi and Dolphin Adventure Gibraltar for their invaluable assistance and collaboration in data collection. We are particularly grateful to the Department of Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change and Heritage of Gibraltar for their technical support and facilitation. This study was carried out within the framework of scientific projects funded by the FIUS (Foundation for Research at the University of Seville), with additional support from the Port Authority of the Bay of Algeciras (APBA), the CEPSA Foundation, Red Eléctrica de España (REE), ACERINOX, the Provincial Council of Cádiz, Alcaidesa Marina, and Club Marítimo Linense.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Paco Gil Vera and Iris Anfruns Fernández were employed by the company Turmares Tarifa. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SG | Strait of Gibraltar |

| Eastern SG | Eastern Strait of Gibraltar |

| Central SG | Central Strait of Gibraltar |

| SAC | Special Area of Conservation |

References

- Cooke, J.G. Balaenoptera physalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018, p. e.T2478A50349982. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/2478/50349982 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Panigada, S.; Gauffier, P.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. Balaenoptera physalus (Mediterranean Subpopulation). 2021, p. e.T16208224A50387979. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/16208224/50387979 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Geijer, C.K.A.; Jones, P.J.S. A network approach to migratory whale conservation: Are MPAs the way forward or do all roads lead to the IMO? Mar. Pol. 2015, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Carroll, E.L.; Constantine, R.; Andrews-Goff, V.; Childerhouse, S.; Cole, R.; Goetz, K.T.; Meyer, C.; Ogle, M.; Harcourt, R.; et al. Effectiveness of marine protected areas in safeguarding important migratory megafauna habitat. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérubé, M.; Aguilar, A.; Dendanto, D.; Larsen, F.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Sears, R.; Sigurjónsson, J.; Urban-Ramírez, J.; Palsbøll, P.J. Population genetic structure of North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea and Sea of Cortez fin whales, Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus 1758): Analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear loci. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.A.; Prieto, R.; Jonsen, I.; Baumgartner, M.F.; Santos, R.S. North Atlantic Blue and Fin Whales Suspend Their Spring Migration to Forage in Middle Latitudes: Building up Energy Reserves for the Journey? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, A.; García-Vernet, R. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus). In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3rd ed.; Würsig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., Kovacs, K.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, M.C.C.; Cheeseman, T.; Jackson, J.A.; Friedlaender, A.S.; Pallin, L.; Olio, M.; Wedekin, L.L.; Daura-Jorge, F.G.; Cardoso, J.; Santos, J.D.F.; et al. The Southern Ocean Exchange: Porous Boundaries between Humpback Whale Breeding Populations in Southern Polar Waters. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.; García-Cegarra, A.M.; Docmac, F.; Ñacari, L.A.; Harrod, C. Multiple Stable Isotopes (C, N & S) Provide Evidence for Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Trophic Ecology and Movements in the Humboldt Current System of Northern Chile. Mar. Environ. Res. 2023, 192, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.F.; Hall, C.; Moore, T.J.; Sheredy, C.; Redfern, J.V. Global Distribution of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Post-Whaling Era (1980–2012). Mamm. Rev. 2015, 45, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulich, A.; McCauley, R.; Miller, S.; Samaran, F.; Giorli, G.; Saunders, P.; Erbe, C. Seasonal Distribution of the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in Antarctic and Australian Waters Based on Passive Acoustics. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 864153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Castellote, M.; Druon, J.-N.; Panigada, S. Fin Whales, Balaenoptera physalus. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2016, 75, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, L. Some Notes on the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Western Mediterranean Sea. In Proceedings of the Whales: Biology–Threats–Conservation, Brussels, Belgium, 5–7 June 1991; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G.; Zanardelli, M.; Jahoda, M.; Panigada, S.; Airoldi, S. The Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus (L. 1758) in the Mediterranean Sea. Mammal Rev. 2003, 33, 105–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canese, S.; Cardinali, A.; Fortuna, C.M.; Giusti, M.; Lauriano, G.; Salvati, E.; Greco, S. The First Identified Winter-Feeding Ground of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2006, 86, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellote, M.; Clark, C.W.; Lammers, M.O. Acoustic and Behavioural Changes by Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in Response to Shipping and Airgun Noise. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 147, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellote, M.; Clark, C.W.; Lammers, M.O. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Population Identity in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2012, 28, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijer, C.K.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Panigada, S. Mysticete Migration Revisited: Are Mediterranean Fin Whales an Anomaly? Mammal Rev. 2016, 46, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, R.; Camacho-Sánchez, A.; Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Martín-Moreno, E.; Patón, D.; García-Gómez, J.C. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Historical Sightings and Strandings, Ship Strikes, Breeding Areas and Other Threats in the Mediterranean Sea: A Review (1624–2023). Environments 2024, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsbøll, P.J.; Bérubé, M.; Aguilar, A.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Nielsen, R. Discerning between Recurrent Gene Flow and Recent Divergence under a Finite-Site Mutation Model Applied to North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Populations. Evolution 2004, 58, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauffier, P.; Verborgh, P.; Giménez, J.; Esteban, R.; Salazar-Sierra, J.M.; De Stephanis, R. Contemporary Migration of Fin Whales through the Strait of Gibraltar. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 588, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmaktub Asociación. Proyecto Rorcual y Biodiversidad en la Costa Catalana—Informe 2024: Proyecto Rorcual a lo Largo de la Costa Catalana: Campañas de Foto Identificación, Etiquetado Satelital y Seguimiento; Edmaktub Asociación: Barcelona, Spain, 2024; Informe técnico. [Google Scholar]

- Panigada, V.; Bodey, T.W.; Friedlaender, A.; Druon, J.N.; Huckstädt, L.A.; Pierantonio, N.; Degollada, E.; Tort, B.; Panigada, S. Targeting Fin Whale Conservation in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea: Insights on Movements and Behaviour from Biologging and Habitat Modelling. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotté, C.; d’Ovidio, F.; Chaigneau, A.; Lévy, M.; Taupier-Letage, I.; Mate, B.; Guinet, C. Scale-Dependent Interactions of Mediterranean Whales with Marine Dynamics. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011, 56, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Fromentin, J.; Demarcq, H.; Brisset, B.; Bonhommeau, S. Co-Occurrence and Habitat Use of Fin Whales, Striped Dolphins and Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, R.; Degollada, E.; Belda, E.J.; Feliu-Tena, B.; Martín-Moreno, E.; Tort, B.; Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Anfruns, I.; Gallego, V.; Gil, P.; et al. Match the Whale: Monitoring Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Migration between the Western Mediterranean Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar. In Proceedings of the Poster presented at the 36th Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 14–16 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gauffier, P.; Borrell, A.; Silva, M.A.; Víkingsson, G.A.; López, A.; Giménez, J.; Colaço, A.; Halldórsson, S.D.; Vighi, M.; Prieto, R.; et al. Wait Your Turn, North Atlantic Fin Whales Share a Common Feeding Ground Sequentially. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 155, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort, B.; Mészáros, D.; Belda, E.J.; Feliu-Tena, B.; Gallego, V.; Saavedra, C.; Degollada, E. From the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean: Fin Whale Migration between Two Feeding Grounds. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 14–16 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, D.; Reisinger, R.; Friedlaender, A.; Zerbini, A.; Prieto, R.; De Silva, M.; Ferguson, S.; Panigada, S.; Lydersen, C.; Vermeulen, E.; et al. Protecting Blue Corridors Dataset. 2025. Available online: https://bluecorridors.org (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Panigada, S.; Pesante, G.; Zanardelli, M.; Capoulade, F.; Gannier, A.; Weinrich, M.T. Mediterranean Fin Whales at Risk from Fatal Ship Strikes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Wright, A.J.; Ashe, E.; Blight, L.K.; Bruintjes, R.; Canessa, R.; Clark, C.W.; Cullis-Suzuki, S.; Dakin, D.T.; Erbe, C.; et al. Impacts of Anthropogenic Noise on Marine Life: Publication Patterns, New Discoveries, and Future Directions in Research and Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 115, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weelden, C.; Towers, J.R.; Bosker, T. Impacts of Climate Change on Cetacean Distribution, Habitat and Migration. Clim. Change Ecol. 2021, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, B.; Garcia-Garin, O.; Borrell, A.; Aguilar, A.; Víkingsson, G.A.; Eljarrat, E. Transplacental Transfer of Plasticizers and Flame Retardants in Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) from the North Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laist, D.W.; Knowlton, A.R.; Mead, J.G.; Collet, A.S.; Podestà, M. Collisions between Ships and Whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2001, 17, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, T.; Druon, J.N. Mapping of Potential Risk of Ship Strike with Fin Whales in the Western Mediterranean Sea: A Scientific and Technical Review Using the Potential Habitat of Fin Whales and the Effective Vessel Density; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di-Meglio, N.; David, L.; Monestiez, P. Sperm Whale Ship Strikes in the Pelagos Sanctuary and Adjacent Waters: Assessing and Mapping Collision Risks in Summer. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2018, 18, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzis, A.; Leaper, R.; Alexiadou, P.; Prospathopoulos, A.; Lekkas, D. Shipping Routes through Core Habitat of Endangered Sperm Whales along the Hellenic Trench, Greece: Can We Reduce Collision Risks? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, R.P.; Patterson-Abrolat, C.; Plön, S. A Global Review of Vessel Collisions with Marine Animals. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, C.; Panigada, S.; Murphy, S.; Ritter, F. Global Numbers of Ship Strikes: An Assessment of Collisions between Vessels and Cetaceans Using Available Data in the IWC Ship Strike Database. IWC B 2020, 68, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, F.; Lahaye, E.; Moulins, A.; Borroni, A.; Rosso, M.; Tepsich, P. Locating Ship Strike Risk Hotspots for Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) along Main Shipping Lanes in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Arcangeli, A.; Tepsich, P.; Di-Meglio, N.; Roul, M.; Campana, I.; Gregorietti, M.; Moulins, A.; Rosso, M.; Crosti, R. Computing Ship Strikes and Near Miss Events of Fin Whales along the Main Ferry Routes in the Pelagos Sanctuary and Adjacent West Area, in Summer. Aquat. Conserv. 2022, 32, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort, B.; González, R.; O’Callaghan, S.; Rein-Loring, P.; Bastos, E. Ship Strike Risk for Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) off the Garraf Coast, Northwest Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 867287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sèbe, M.; David, L.; Dhermain, F.; Gourguet, S.; Madon, B.; Ody, D.; Panigada, S.; Peltier, H.; Pendleton, L. Estimating the Impact of Ship Strikes on the Mediterranean Fin Whale Subpopulation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 237, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, A.; Campana, I.; Gregorietti, M.; Moreno, E.M.; García Sanabria, J.; Arcangeli, A. Tying up Loose Ends Together: Cetaceans, Maritime Traffic and Spatial Management Tools in the Strait of Gibraltar. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 2024, 34, e4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Alleaume, S.; Guinet, C. Evaluation of the Potential of Collision between Fin Whales and Maritime Traffic in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea in Summer, and Mitigation Solutions. JMATE 2011, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna, C.; Sánchez-Espinosa, A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D.; Malak, A.; Podestà, D.; Panigada, M. Pathways to Coexistence between Large Cetaceans and Maritime Transport in the North-Western Mediterranean Region: Collision Risk Between Ships and Whales within the Proposed North-Western Mediterranean Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA), Including the Pelagos Sanctuary. 2022. Available online: https://planbleu.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Pathways-to-coexistence-between-largecetaceans-and-maritime-transport-in-the-north-western-Mediterranean-region.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Panigada, S.; Donovan, G.P.; Druon, J.-N.; Lauriano, G.; Pierantonio, N.; Pirotta, E.; Zanardelli, M.; Zerbini, A.N.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. Satellite tagging of Mediterranean fin whales: Working towards the identification of critical habitats and the focusing of mitigation measures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, C.; Arbelo, M.; Fernández, A.; Díaz, J.; Bernaldo, Y.; De la Fuente, J.; Arregui, M.; Sierra, E. Ship Strikes: Two Cases of Fin Whales Stranded on the South Atlantic Spanish Coast. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, O’Grove, Spain, 18–20 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rediam. Serie Histórica de Varamientos y Hallazgos de Fauna Marina en el Litoral Andaluz (2007–2024) [Dataset]; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Desarrollo Sostenible: Andalucía, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://portalrediam.cica.es (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- de Stephanis, R.; Urquiola, E. Collisions between Ships and Cetaceans in Spain. In Scientific Committee Report SC/58/BC5; International Whaling Commission: Impington, UK; Gobierno de Canarias: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2009; Available online: https://docplayer.net/25356858-Collisions-between-ships-and-cetaceans-in-spain.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Fernández-Maldonado, C. Patología y Causas de Muerte de Cetáceos Varados en Andalucía (2011–2014). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Montewka, J.; Rasero Balón, J.C.; Endrina, N. Risk Analysis for Maritime Traffic in the Strait of Gibraltar. In Maritime Transport and Harvesting of Sea Resources; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cepillo Galvín, M.A. The Control of Maritime Traffic in the Strait of Gibraltar. Span. Yearb. Int. Law 2014, 18, 73–104. Available online: https://www.sybil.es/sybil/article/view/1513 (accessed on 24 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mavor, J.W., Jr. Ship Traffic through Gibraltar Strait. J. Navig. 1980, 33, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenan, S.; Hernández, N.; Fearnbach, H.; de Stephanis, R.; Verborgh, P.; Oro, D. Impact of Maritime Traffic and Whale-Watching on Apparent Survival of Bottlenose Dolphins in the Strait of Gibraltar. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 2020, 30, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Interior. La Operación Paso del Estrecho 2025 Finaliza con Récord de Vehículos y Pasajeros Embarcados. 2025. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/eu/detalle/articulo/La-Operacion-Paso-del-Estrecho-2025-finaliza-con-record-de-vehiculos-y-pasajeros-embarcados/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Espada, R.; Martín, L.; Haasova, L.; Olaya-Ponzone, L.; García-Gómez, J.C. Presencia permanente del delfín común en la bahía de Algeciras: Hacia un plan de gestión, vigilancia y conservación de la especie. Almoraima Rev. Estud. Campogibraltareños 2018, 49, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, J.; Abaunza, P. The Present State of Traps and Fisheries Research in the Strait of Gibraltar. In The Bluefin Tuna Fishery in the Bay of Biscay; Springer Briefs in Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.; Camiñas, J.A.; Molina, M.; Cavallé, M. Interaction Between Cetaceans and Small-Scale Fisheries in the Mediterranean. Low Impact Fish. Eur. 2020, 81, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Espada, R.; Moreno, E.M.; Marcial, I.C.; García-Gómez, J.C. Injuries, Healing and Management of Common Dolphins (Delphinus delphis) in Human-Impacted Waters in the South Iberian Peninsula. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2020, 100, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Ruíz, R.E.; Domínguez, D.P.; Moreno, E.M.; Marcial, I.C.; Santiago, J.S.; García-Gómez, J.C. Sport Fishing and Vessel Pressure on the Endangered Cetacean Delphinus delphis: Towards an International Agreement of Micro-Sanctuary for Its Conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Cerban, M.D.M. Bunkering Competition and Competitiveness at the Ports of the Gibraltar Strait. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; De Stephanis, R.; Verborgh, P.; Sánchez, A.; Guinet, C. Distribución Espacial de Cetáceos en el Estrecho de Gibraltar Durante la Época Estival. Almoraima. Rev. Estud. Campogibraltareños 2007, 35, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- de Stephanis, R.; Cornulier, T.; Verborgh, P.; Salazar-Sierra, J.; Pérez-Gimeno, N.; Guinet, C. Summer Spatial Distribution of Cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar in Relation to the Oceanographic Context. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 353, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisi, A.C.; Welch, H.; Brodie, S.; Leiphardt, C.; Rhodes, R.; Hazen, E.L.; Redfern, J.V.; Branch, T.A.; Barreto, A.S.; Calambokidis, J.; et al. Ship Collision Risk Threatens Whales Across the World’s Oceans. Science 2024, 386, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armi, L.; Farmer, D. The Internal Hydraulics of the Strait of Gibraltar and Associated Sills and Narrows. Oceanol. Acta 1985, 8, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden, H.L.; Kinder, T.H. Recent Progress in Strait Dynamics. Rev. Geophys. 1991, 29 (Suppl. S2), 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Lafuente, J.G.; Vargas, J.M. A Simple Model for Submaximal Exchange Through the Strait of Gibraltar. Sci. Mar. 2001, 65, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, J.G.; Vargas, J.M.; Plaza, F.; Sarhan, T.; Candela, J.; Bascheck, B. Tide at the Eastern Section of the Strait of Gibraltar. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2000, 105, 14197–14213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado Aldeanueva, F.; García Lafuente, J.; Sánchez Garrido, J.C.; Baquerizo, A.; Sannino, G. Time-Spatial Variability Observed in Velocity of Propagation of the Internal Bore in the Strait of Gibraltar. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, C07034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, P.; Piedracoba, S.; Sotillo, M.G.; Álvarez Fanjul, E. Long-Term Monitoring of the Atlantic Jet through the Strait of Gibraltar with HF Radar Observations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stommel, H.; Farmer, H.G. Classic article: Control of salinity in an estuary by a transition. J. Mar. Res. 2021, 79, 91–98. Available online: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/505 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, H.; Richez, C. The regime of the Strait of Gibraltar. In Hydrodynamics of Semi-Enclosed Seas; Nihoul, J.C.J., Ed.; Elsevier Oceanography Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; Volume 34, pp. 13–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, D.M.; Armi, L. Maximal two-layer exchange over a sill and through the Strait of Gibraltar. Prog. Oceanogr. 1986, 164, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A. Estudio del Flujo Baroclínico en el Estrecho de Gibraltar Mediante Observaciones y Modelización Numérica. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GEBCO Compilation Group. GEBCO 2021 Grid; British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC): Liverpool, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMODnet Human Activities. Vessel Density Maps (2017–2023); European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet); Version 10. 2023. Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/human-activities/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- EMODnet. Vessel Density Map—Detailed Methodology; European Marine Observation and Data Network. 2023. Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/sites/emodnet.ec.europa.eu/files/public/HumanActivities_20231101_VesselDensityMethod.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Spain. Royal Decree 210/2004 of 6 February, Establishing a Monitoring and Information System on Maritime Traffic in Waters under Spanish Jurisdiction. Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), No. 35, 11 February 2004. 2004. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2004/02/06/210/con (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Falco, L.; Pititto, A.; Adnams, W.; Earwaker, N.; Greidanus, H. EU Vessel Density Map—Detailed Method; EMODnet Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Pro, Version 3.4.3. GIS Software. Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Hauser, D.D.W.; Laidre, K.L.; Stern, H.L. Vulnerability of Arctic marine mammals to vessel traffic in the increasingly ice-free Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9983–9988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardin, R.H.; Chun, Y.; Jenkins, C.N.; Maciel, I.S.; Simão, S.M.; Alves, M.A.S. Environment and anthropogenic activities influence cetacean habitat use in southeastern Brazil. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 616, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, J.V.; Ferguson, M.C.; Becker, E.A.; Hyrenbach, K.D.; Good, C.; Barlow, J.; Kaschner, K.; Baumgartner, M.F.; Forney, K.A.; Ballance, L.T.; et al. Techniques for Cetacean Habitat Modeling. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 310, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicacha-Parada, J.; Steinsland, I.; Cretois, B.; Borgelt, J. Accounting for spatial varying sampling effort due to accessibility in Citizen Science data: A case study of moose in Norway. Spat. Stat. 2021, 40, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMODnet. New insights from European Maritime Traffic—EMODnet Vessel Density Maps. 2023. Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/new-insights-european-maritime-traffic-emodnet-vessel-density-maps (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Pirotta, V.; Grech, A.; Jonsen, I.D.; Laurance, W.F.; Harcourt, R.G. Consequences of global shipping traffic for marine giants. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS). AIS Data for Maritime Surveillance and Modeling. Copernicus Marine Service Information. 2022. Available online: https://marine.copernicus.eu (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA). AIS Monitoring of Fishing Activities in European Waters. EFCA Publications. 2022. Available online: https://www.efca.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-06/EFCA%20Annual%20Report%202022.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- MarineTraffic. Global Ship Tracking Intelligence. 2023. Available online: https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/data/?asset_type=vessels (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Panigada, S.; Zanardelli, M.; MacKenzie, M.; Donovan, C.; Mélin, F.; Hammond, P.S. Modelling Habitat Preferences for Fin Whales and Striped Dolphins in the Pelagos Sanctuary (Western Mediterranean Sea) with Physiographic and Remote Sensing Variables. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3400–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, G.K.; Slutsky, J.; Bettridge, S. Hydrodynamics of a ship/whale collision. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 391, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinno, A. Dunn’s Test of Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. R Package Version 1.3.6. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dunn.test (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Pivorunas, A. The fibrocartilage skeleton and related structures of ventral pouch of balaenopterid whales. J. Morphol. 1977, 151, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, P.F. Noise generated by the jaw actions of feeding fin whales. Can. J. Zool. 1993, 71, 2546–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, A.J. Models of hydrodynamic flow in the bowhead whale filter feeding apparatus. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 3569–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbogen, J.A.; Calambokidis, J.; Shadwick, R.E.; Oleson, E.M.; McDonald, M.A.; Hildebrand, J.A. Kinematics of foraging dives and lunge-feeding in fin whales. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Real Decreto 1620/2012, por el que se Declara Zona Especial de Conservación (ZEC) el Lugar de Importancia Comunitaria ES6120032 Estrecho Oriental y se Aprueban las Correspondientes Medidas de Conservación; BOE núm. 289, de 1 de Diciembre de 2012. 2012. Available online: https://www.boe.es/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Government of Gibraltar. Designation of Special Areas of Conservation (Southern Waters of Gibraltar) Order 2011 (LN 2011/019). Nature Protection Act 1991. 2011. Available online: https://www.gibraltarlaws.gov.gi/legislations/designation-of-special-areas-of-conservation-southern-waters-of-gibraltar-order-2011-2674/download (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Junta de Andalucía (Consejería de Medio Ambiente). Decreto 57/2003, de 4 de Marzo, de Declaración del Parque Natural del Estrecho; BOJA. 2003. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2003/54/4 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Gende, S.M.; Hendrix, A.N.; Harris, K.R.; Eichenlaub, B.; Nielsen, J.; Pyare, S. A Bayesian approach for understanding the role of ship speed in whale-ship encounters. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 2232–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conn, P.B.; Silber, G.K. Vessel speed restrictions reduce risk of collision-related mortality for North Atlantic right whales. Ecosphere 2013, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlaan, A.S.M.; Taggart, C.T. Vessel collisions with whales: The probability of lethal injury based on vessel speed. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2007, 23, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.E.; Vlasic, J.P.; Brillant, S.W. Assessing the lethality of ship strikes on whales using simple biophysical models. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2021, 37, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, L.P.; Lisi, N.E.; Gahm, M.; Patterson, E.M.; Blondin, H.; Good, C.P. The effects of vessel speed and size on the lethality of strikes of large whales in US waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1467387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacek, D.P.; Thorne, L.H.; Johnston, D.W.; Tyack, P.L. Responses of cetaceans to anthropogenic noise. Mammal Rev. 2007, 37, 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.H.; Bejder, L.; Wahlberg, M.; Madsen, P.T. Noise levels and masking potential of small whale-watching boats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 395, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshwaran, A.; Deo, I.K.; Jelovica, J.; Jaiman, R.K. A multi-objective optimization framework for reducing the impact of ship noise on marine mammals. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, A.M. Many wrongs: The advantage of group navigation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codling, E.A.; Pitchford, J.W.; Simpson, S.D. Group navigation and the “many-wrongs principle” in models of animal movement. Ecology 2007, 88, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.T.; Painter, K.J. Modelling collective navigation via non-local communication. J. R. Soc. Interface 2021, 18, 20210383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.; Webb, D. Orientation by means of long-range acoustic signalling in baleen whales. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1971, 188, 110–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.W.; Gagnon, G.J. Baleen whale acoustic ethology. In Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Mysticetes; Clark, C.W., Garland, E.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tyack, P.L. Social organization of baleen whales. In Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Mysticetes; Clark, C.W., Garland, E.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.L. Studying how cetaceans use sound to explore their environment. In Communication (Perspectives in Ethology); Owings, D.H., Beecher, M.D., Thompson, N.S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 12, pp. 251–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mate, B.R.; Urbán-Ramírez, J. A note on the route and speed of a gray whale on its northern migration from Mexico to central California, tracked by satellite-monitored radio tag. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2003, 5, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zapetis, M.; Szesciorka, A. Cetacean navigation. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.T.; Painter, K.J. Avoidance, confusion or solitude? Modelling how noise pollution affects whale migration. Mov. Ecol. 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras Merida, M.R.; Merchant, N.D.; Warr, S.; Dissanayake, A. Underwater noise in the Bay of Gibraltar. SSRN Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Tadeo, M.P.; O’Brien, J. Underwater noise levels in the Strait of Gibraltar and surrounding waters: Findings from the AMIGOS survey. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1655366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.J.; Greene, C.R., Jr.; Malme, C.I.; Thomson, D.H. Marine Mammals and Noise; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Southall, B.L.; Bowles, A.E.; Ellison, W.T.; Finneran, J.J.; Gentry, R.L.; Greene, C.R., Jr.; Kastak, D.; Ketten, D.R.; Miller, J.H.; Nachtigall, P.E.; et al. Marine mammal noise-exposure criteria: Initial scientific recommendations. Bioacoustics 2008, 17, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf, S. Introduction. In Tuna Wars; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- European Union. Directive 2011/15/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2011 on the compulsory use of the Automatic Identification System (AIS) for fishing vessels of 15 meters in length and above. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, L62, 1–7. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32011L0015 (accessed on 25 August 2025).[Green Version]

- Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Espada Ruíz, R.; Martín Moreno, E.; Patón Domínguez, D.; García-Gómez, J.C. Effects of vessels on common dolphin activity patterns in a critical area for the species. Conservation implications. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 207, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Espada Ruíz, R.; Martín Moreno, E.; Patón Domínguez, D.; García-Gómez, J.C. Vessel-induced behavioural changes in striped and bottlenose dolphins in southern Spain. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2025, 35, e70183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, A. Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management of Areas Hosting Marine Mammals: A Case Study in the Strait of Gibraltar. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2023. Available online: https://rodin.uca.es/handle/10498/29223 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- He, P.; Chopin, F.; Suuronen, P.; Ferro, R.S.T.; Lansley, J. Classification and illustrated definition of fishing gears. In FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 672; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero Ramírez, A.P. Competencia Entre Orcas y Pescadores de la Piedra por el Atún Rojo en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Master’s Thesis, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G.; Agardy, T.; Hyrenbach, D.; Scovazzi, T.; Van Klaveren, P. The Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean marine mammals. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2007, 18, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Declaración del Corredor de Migración de Cetáceos del Mediterráneo como Zona Especialmente Protegida de Importancia para el Mediterráneo (ZEPIM/SPAMI). Boletín Oficial del Estado 2019, 197, 74101–74103. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2019-10189 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Resolution MEPC.380(80): Designation of the North-Western Mediterranean Sea as a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area. Marine Environment Protection Committee 2023, 80th session. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MEPCDocuments/MEPC.380(80).pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Laist, D.W.; Knowlton, A.R.; Pendleton, D. Effectiveness of mandatory vessel speed limits for protecting North Atlantic right whales. Endanger. Species Res. 2014, 23, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Particularly Sensitive Sea Area: Strait of Bonifacio. Resolution MEPC.204(62); Marine Environment Protection Committee. 2011. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MEPCDocuments/MEPC.204(62).pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- IUCN-MMPATF. Northwest Mediterranean Sea, Slope and Canyon System IMMA Factsheet. IUCN Joint SSC/WCPA Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force. 2017. Available online: https://www.marinemammalhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/imma-factsheets/Mediterranean/North-Western-Mediterranean-Sea-Slope-and-Canyon-System-Mediterranean.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Parrott, L.; Chion, C.; Turgeon, S.; Ménard, N.; Cantin, G.; Michaud, R. Slow down and save the whales. Solutions 2016, 6, 40–47. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292695424_Slow_down_and_save_the_whales (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- International Whaling Commission. Report of the Joint IWC-SPAW Workshop to Address Collisions Between Marine Mammals and Ships With a Focus on the Wider Caribbean. Report IWC/65/CCrep01 Discussed at the 14th Meeting of the Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel; International Whaling Commission: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Available online: https://archive.iwc.int/?r=567 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Identification and Protection of Special Areas and PSSAs: Information on Recent Outcomes Regarding Minimizing Ship Strikes to Cetaceans. Int. Marit. Organ. Mar. Environ. Prot. Comm. Doc. MEPC 69/10/3; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://iwc.int/public/documents/meEX2/MEPC_69_10_3_Information_on_recent_outcomes_regarding_minimizing_ship_strikes_to_cetaceans_International_Whaling_Com..._002_.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).