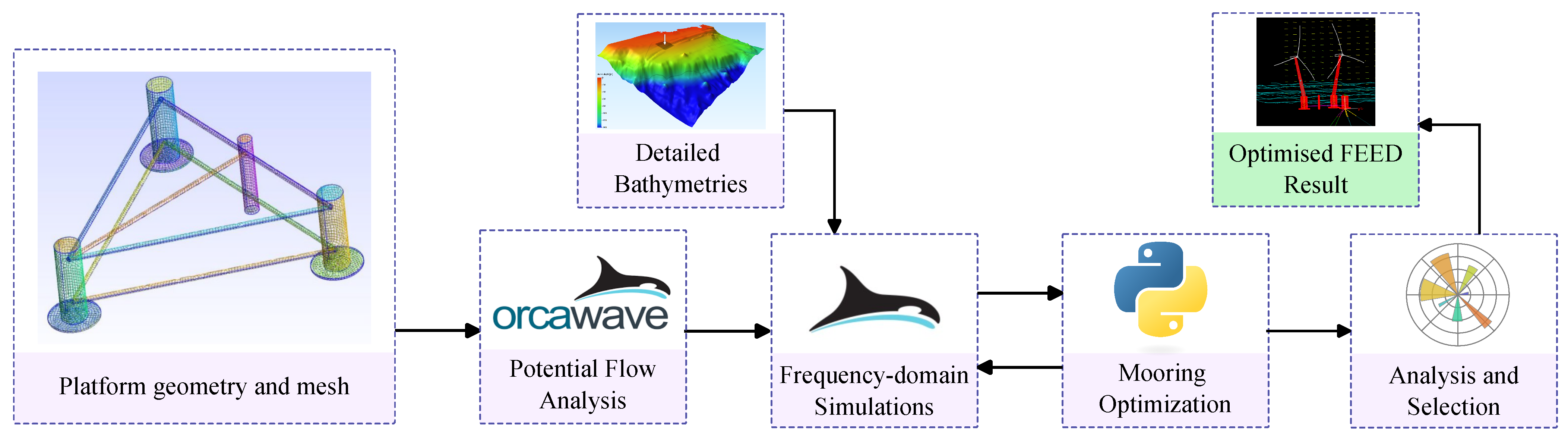

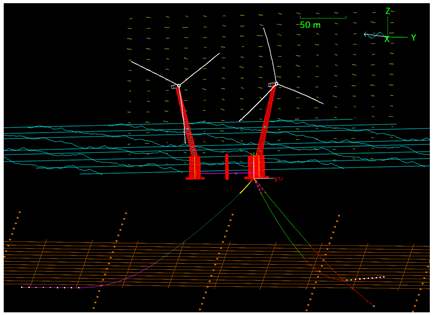

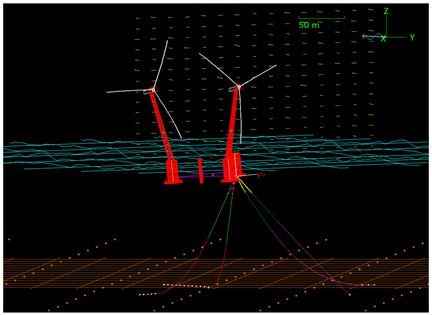

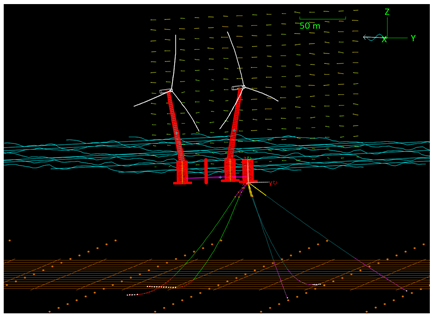

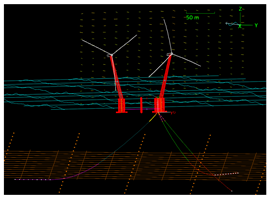

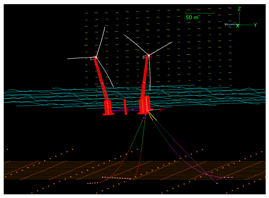

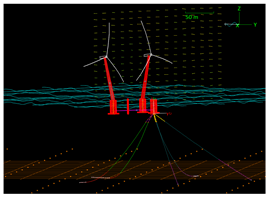

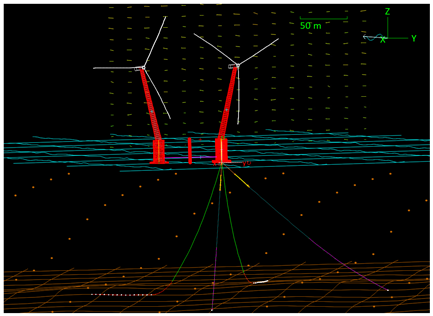

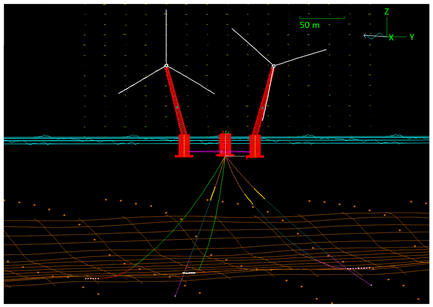

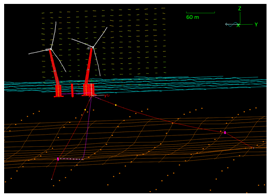

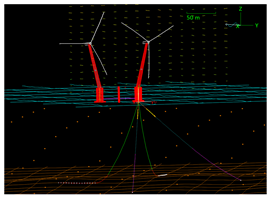

To streamline the presentation of the results, a common structure is adopted for all case studies. The results are obtained exclusively with the previously described tools: OrcaFlex for the structural modeling of the FOWT and Python to interface OrcaFlex with the optimization routine. For clarity, the results are organized into two subsections, one per site-specific case study. For each site, a first table provides images of the final optimal mooring layouts and the corresponding mooring line characteristics for the 3-, 4-, and 5-line solutions. A second table then reports the total costs of the resulting configurations, highlighting the best-performing, lowest-cost designs.

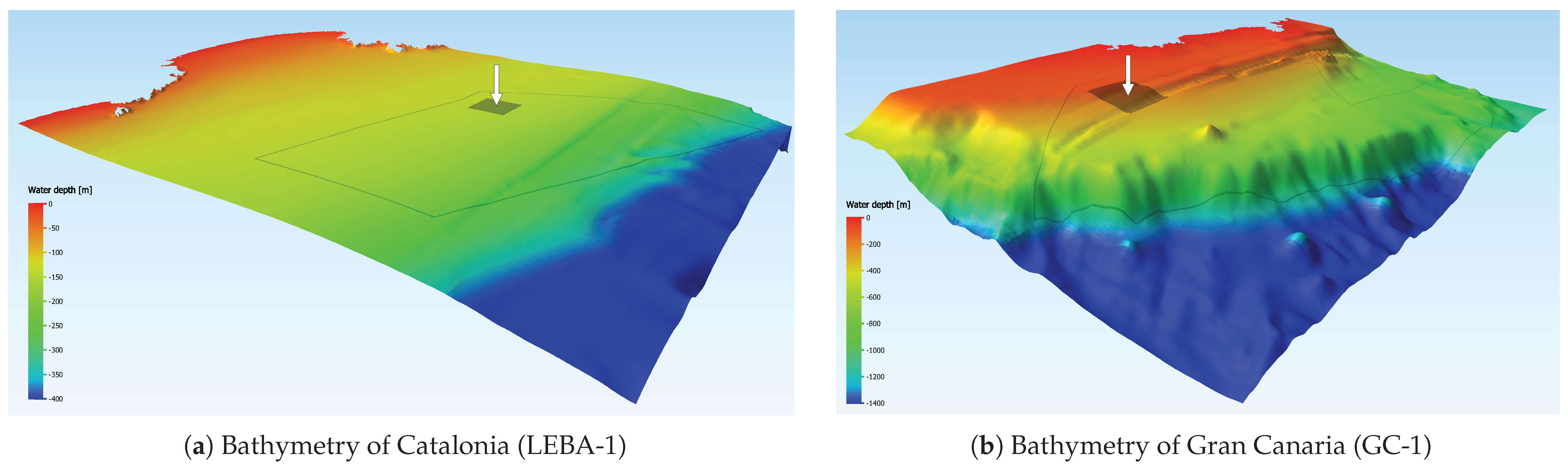

3.1. Mediterranean Site: Catalonia (Gulf of Roses, LEBA-1)

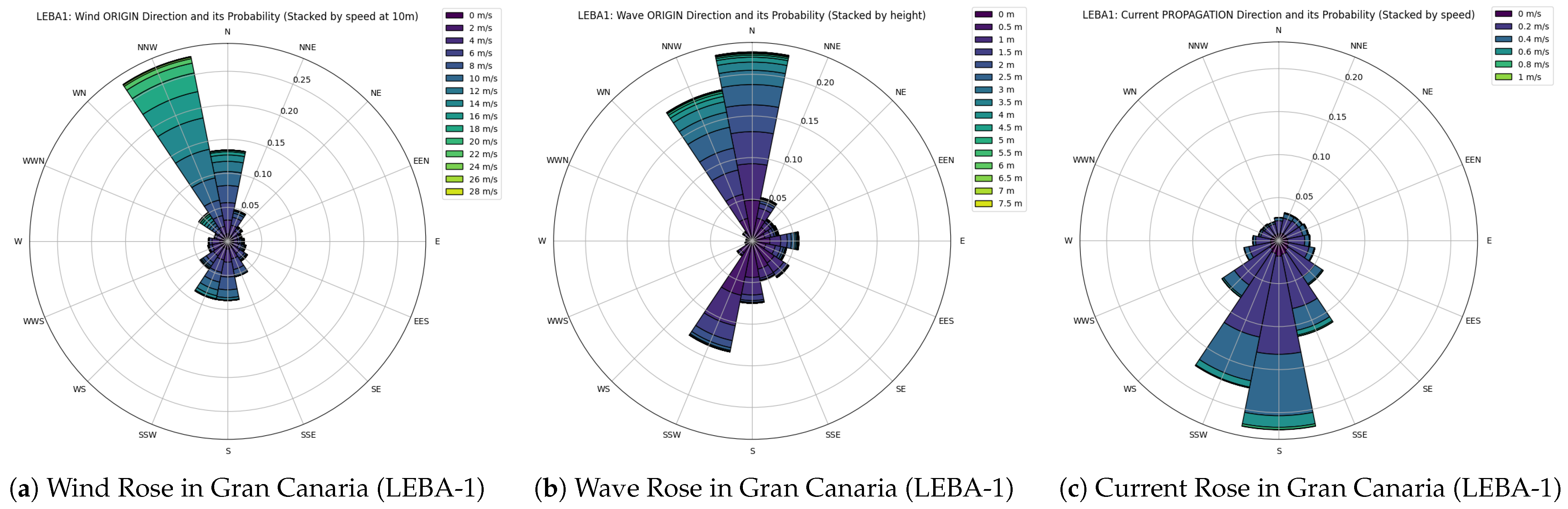

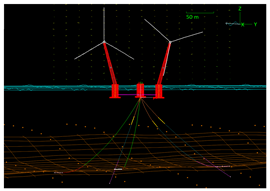

Environmental conditions at the LEBA-1 site do not indicate a prevailing upwind direction. Hence, the mooring system is designed to resist loads from any direction. All lines are configured identically and connected to the turret of the upwind column, which allows the twin-turbine platform to weathervane. Due to the sandy/muddy seabed, the optimization considers suction anchors and/or drag-embedded anchors as possible anchoring solutions. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

The solutions use suction anchors arranged radially around the connection point and consist of chain–wire composite lines without auxiliary clump weights or buoyancy modules.

In the three-line configuration, each line follows a catenary profile without prestretch. The suction anchors are positioned on a circle of 259 m radius. Each line includes a 154 m bottom chain (BC) with a diameter of 102 mm, grade ORQ, connected to a 116 m wire section of 82 mm diameter and a short fairlead chain (FC) of 6 m length, 100 mm diameter, grade 3. The system is supported by three load-reduction devices (LRDs) with a nominal capacity of 2000 kN.

The four-line configuration adopts a catenary layout with a catenary of 11% and no prestretch. The anchor radius is reduced to 163 m. The BC length is 142 m with a diameter of 95 mm, grade ORQ, followed by a shorter 56 m wire section of 82 mm diameter. The FC length decreases to only 2 m with a diameter of 87 mm, grade 4. The LRD capacity is increased to 3000 kN to reflect the higher pretension.

The five-line configuration is a fully taut arrangement and introduces a small prestretch of 3%. The suction anchors remain at a radius of 163 m. The BC is shortened to 69 m with a diameter of 76 mm, grade 6. The wire section is lengthened to 116 m with a diameter of 82 mm, and the FC consists of only 2 m of chain with a diameter of 87 mm, grade 5S. The LRDs are again rated at 3000 kN.

Increasing the number of lines from three to four (and to five) allows a substantial reduction of the anchor radius from 259 m to 163 m. This means that moving from three to at least four lines reduces the seabed area requirement by approximately 60% while retaining suction anchors. This inward relocation is physically consistent with load sharing: with more lines, the needed horizontal restoring force per line is reduced, and anchors can be pulled closer to the floater without compromising ultimate limit state (ULS) margins.

Comparing the cases, we can see that as the line count increases, the design systematically shortens and slims the steel chain sections. The bottom chain (BC) length per line reduces from 154 m (3 lines) to 142 m (4 lines, −8%) and to 69 m (5 lines, −55%). The BC diameter similarly reduces from 102 mm to 95 mm (−7%) and to 76 mm (−25%), while the chain grade increases from ORQ (3–4 lines) to Grade 6 (5 lines). The fairlead chain (FC) follows the same trend: its length reduces from 6 m to 2 m (−67%) and its diameter from 100 mm to 87 mm (−13%), with the grade increasing from 3 to 4 and then to 5S. These coordinated choices with shorter lengths and smaller diameters, paired with higher grades, are physically coherent. Higher-strength steels allow smaller diameters without sacrificing minimum breaking load, and the aggregate suspended steel mass near the floater is reduced, improving the vertical center of gravity and decreasing wave-induced inertia loads.

This is reflected in the material allocation, which shifts markedly as line count increases. Using a simple chain tonnage proxy proportional to length times diameter squared, the combined (bottom- plus fairlead-chain) index is about 4.99 for the three-line layout system, rises slightly to 5.19 for the system with four lines, and then drops sharply to 2.07 for the five-line system. In relative terms, the four-line case uses roughly 4% more “chain steel proxy” than the three-line solution, whereas the five-line layout achieves a 59% reduction.

Rope usage follows the opposite trend, signaling a change in the global stiffness strategy. With a diameter held at 82 mm, the total rope length is 348 m in the three-line case (116 m per line), decreases to 224 m in the four-line case (56 m per line), and then increases substantially to 580 m in the five-line case (116 m per line). Only the five-line solution introduces a 3% prestretch. Together, the long, prestretched rope and short, high-grade chains, as well as the 0% catenary form, indicate a fully-taut configuration in which axial elasticity provides the primary restoring mechanism.

Device-assisted load moderation scales with line count as well. The total installed LRD capacity increases from 18 MN in the three-line case (3 × 2000 kN per line across three lines) to 36 MN for four lines and 45 MN for five lines (3 × 3000 kN per line). This progression is consistent with the observed move toward higher axial stiffness and lower catenary damping.

The presented configurations are designed to fulfill the constraints outlawed in

Section 2.3. We summarize dynamic responses and governing limits as utilization percentages of the allowable limits (100% uses the full limit). For the 3-, 4-, 5-line solutions, platform offset utilization is 72%, 92%, 41%, respectively. This shows that the 5-line layout roughly halves the used offset margin relative to 4 lines and is markedly tighter than 3 lines. The airgap remains well within limits at 39–44% of the allowed sea surface clearance across all cases. Pitch is stable and similar (46%, 40%, 40% of allowed limits), and yaw is negligible (≈1%). The anchor ultimate holding capacity utilizations are 79%, 82%, 78% (all comfortably below 100%). The bottom chain (BC) reaches 100% utilization in all cases, indicating it is a governing component sized to its minimum breaking load (MBL). Rope usage is 98%, 90%, 96% of the MBL, showing that the 4-line case carries the lowest rope-tension demands, while the 3- and 5-line cases approach but remain below MBL. Fairlead chain (FC) MBL utilization is 80%, 97%, 81%, indicating that the 4-line design is locally most demanding at the fairlead but still acceptable. The LRD target-load utilization is 134%, 90%, 88%, indicating that with only 3 lines, the selected devices exceed their nominal target. Although they pass all constraints, the LRDs may require upsizing to further enhance system behavior. Both 4- and 5-line systems keep the selected LRDs within their target loads. Fatigue (FLS) was screened using the set-out frequency-domain checks, and all reported solutions passed the adopted fatigue criteria.

The cost of the optimized mooring solutions is summarized in

Table 5. The table provides the unit cost for each line and anchor, and the total system cost is the aggregated cost of all lines and anchors. The reported costs confirm that, for otherwise comparable component choices, total mooring expenditure scales essentially linearly with the number of lines and anchors. The three-line system totals EUR 1.33 M, the four-line system EUR 1.65 M (+24% versus three lines), and the five-line system EUR 2.12 M (+28% versus four lines; +59% versus three lines). Notably, the per-line cost drops from EUR 0.16 M in the three- and four-line designs to EUR 0.14 M in the five-line optimum, reflecting the shift to shorter, smaller-diameter chain segments and a more rope-dominated, near-taut architecture. Per-anchor cost is lowest in the four-line case at EUR 0.25 M, compared with EUR 0.28 M for three- and five-line cases. Given that the optimized anchor radius is 259 m for three lines and 163 m for both four and five lines, the reduction from three to four lines delivers footprint contraction at a modest incremental cost, whereas adding a fifth line raises the anchor count and total cost without further shrinking the radius. Looking at the dynamics, the 5-line design provides the best stability margins (lowest offset utilization and within the target loads of the LRDs) at the expense of higher CAPEX, while 4 lines offer a balanced compromise with tight but acceptable margins and reduced cost.

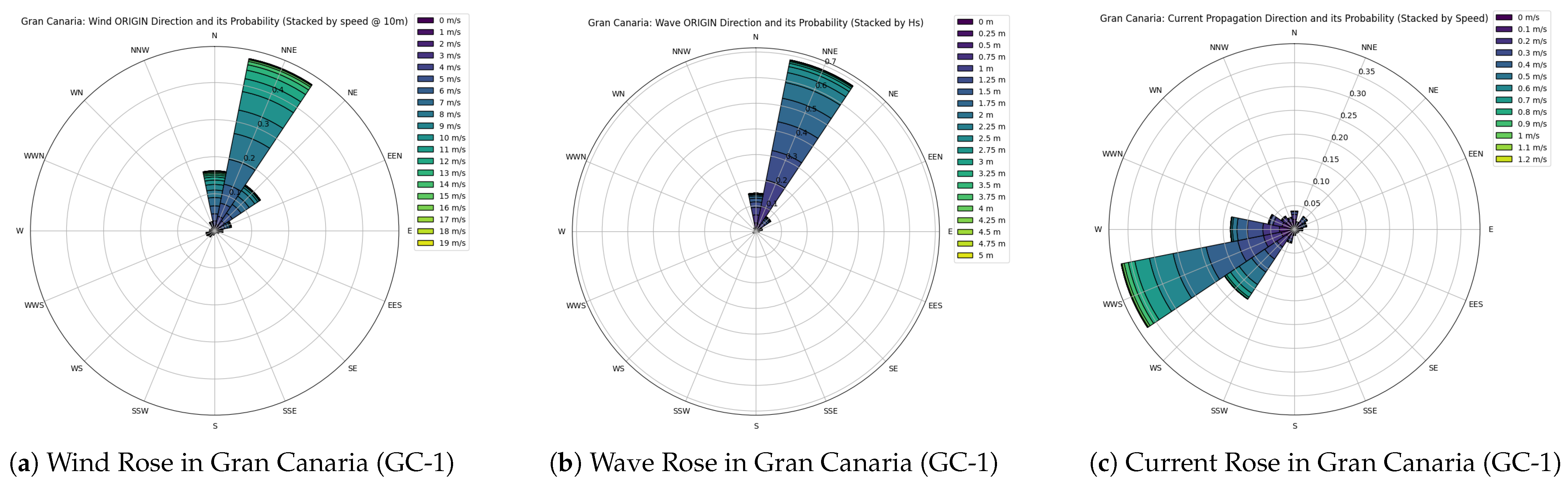

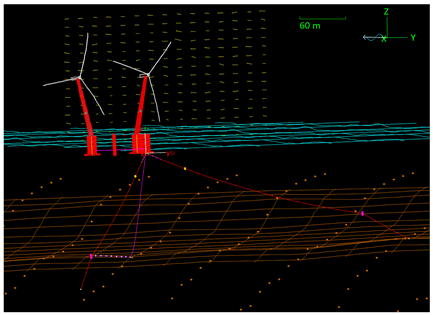

3.2. Atlantic Site: Gran Canaria (Tirajana, GC-1)

Environmental conditions at GC-1 consistently act from a range from N-E towards S-W, which leads to a clear design choice of distinct upwind and downwind mooring lines. In this case, we will consider mooring systems evenly spaced around the floater, while the upwind group always holds the same or more lines than the downwind to distribute the loads more evenly as proposed in [

25]. Due to the volcanic/rocky seabed which may be impenetrable we limit the anchor choice to gravity anchors. The upwind lines carry the governing environmental loads and therefore adopt higher diameters, grades, and device assistance. Downwind lines are lighter and sometimes slightly more catenary to contribute restoring force mainly in moderate offsets.

Table 6 highlights the design choices.

In the three-line configuration, the system is chain-dominated and near-taut with no rope segments. Upwind lines use 342 m × 81 mm ORQ bottom chain plus 4 m × 76 mm grade-6 fairlead chain. The downwind line uses 224 m × 76 mm ORQ bottom chain and 2 m × 81 mm ORQ fairlead chain. Catenary is 0% in both groups, indicating that restoring comes from axial tension and geometry rather than seabed lay-down. A 3 t clump weight near the floater lowers the fairlead angle and adds local compliance. Two 9 t buoys placed close to the anchor lift the final span and increase the padeye uplift angle. This is adverse for gravity anchors that rely on weight and friction. To preserve anchor capacity, this extra uplift must be countered by higher anchor mass, greater anchor radius, and/or peak-load reduction. Reflecting this, anchor radii are large and asymmetric: 314 m upwind and 180 m downwind. Load-reduction devices are installed only upwind (three per line at 1000 kN each), giving 6 MN system capacity. System totals are 908 m of bottom chain and 10 m of fairlead chain, with a combined chain-steel proxy of 5.84. Overall, the layout secures station-keeping through heavy chain and attachments but at the cost of a large upwind footprint and increased anchor uplift due to buoy placement, making it less material- and footprint-efficient than the higher line-count optima for this unidirectional, gravity-anchored site.

The four-line configuration marks a decisive architectural shift. Wire rope is introduced in both groups (upwind 84 m × 82 mm with 4% prestretch; downwind 135 m × 76 mm with no prestretch), and the anchor radii collapse to 160 m in both sectors, effectively halving the upwind radius relative to the three-line case. Upwind bottom chain shortens drastically to 102 m but grows to 120 mm (grade 4), and the fairlead chain becomes longer and stronger at 18 m × 87 mm (grade 6), reflecting higher local tensions and wear near the fairlead in a more axial system. Downwind bottom chain is 92 m × 76 mm (ORQ) with a very short fairlead chain of 2 m × 76 mm (grade 3). The downwind group alone retains a small catenary component (3%), consistent with its secondary role. System-level totals are 388 m of bottom chain, 40 m of fairlead chain, and 438 m of rope. The chain proxy falls to 4.30, a 26% reduction versus three lines, while installed LRD capacity rises sharply to 18 MN (three devices per upwind line at 3000 kN each). Load sharing across four lines and limited but larger wire rope elasticity, plus the upwind LRD capacity rise, allows for a compact footprint with much less bottom chain, while the longer, high-grade fairlead chain on the upwind lines protects the interface where tensions and bending cycles concentrate.

The five-line configuration reinforces the near-taut, elasticity-driven strategy and rebalances material away from the bottom chains. The bottom chains are reduced further to 71 m × 87 mm (grade 6), and downwind to 57 m × 76 mm (ORQ). Wire rope segments lengthen again (upwind 106 m × 90 mm with 7% prestretch; downwind 154 m × 76 mm with 4% prestretch). The upwind fairlead chain becomes very substantial at 53 m × 90 mm (grade 6) and while also increasing slightly on the downwind side to 9 m × 76 mm (grade 6). Both groups show no catenary from. The anchor footprint remains compact but grows relative to four lines, governed by an upwind radius of 198 m (downwind 160 m), which is still far smaller than the three-line case. Whole-system totals are 327 m of bottom chain, 177 m of fairlead chain, and 626 m of rope. Despite the large fairlead segment, the overall chain proxy drops again to 3.66, 37% below the three-line solution and 15% below the four-line solution. LRDs remain upwind-only (three per line at 2000 kN), summing again to a total of 18 MN. The pattern reveals a deliberate push toward axial stiffness and device-assisted load management, with rope elasticity and fairlead chain absorbing dynamics while the bottom chain is minimized to reduce seabed interaction and anchor demands.

For the Gran Canaria site, a similar system behavior can be observed as for the Catalonia systems, as the responses tighten with increasing line count. The allowed offset utilization drops from 96% (3 lines) to 58% (4 lines) and 34% (5 lines). The airgap usage remains modest at 24–27%, and pitch reduces from 40% to 31–30% of its limit. Yaw motion reaches ≈ 1–2% degrees of its allowance in all cases and is negligible. The utilization of the upwind anchor is 99%, 40% and 71% of the ultimate holding capacity for the 3/4/5-line designs, with negligible downwind demands (≤5%). Bottom-chain MBL usage (upwind) trends 100%, 50%, 91%, indicating the 3-line layout sizes the upwind BC to its limit, while the 4-line configuration shows reduced relative demand. Rope MBL usage is much higher in the upwind than for the downwind groups (upwind ≈ 90%, downwind 5–7%). Forerunner chains (upwind) are loaded with 70–90% of their design limit, downwind ≤10%. LRD target-load utilization (upwind) is 269%, 102%, and 126%, indicating that the nominal target load in the 3-line case is clearly exceeded and would require upsizing for more favorable system responses. In the 5-line case, the system behavior exceeds the target load but is still in a favorable low-stiffness zone. The 4-line configuration indicates an ideal working behavior of the applied LRD.

Table 7 mirrors the cost of the case study. Total mooring cost increases with line count, even as unit costs per line decline. System totals are 1.35 M€ (3 lines), 1.80 M€ (4 lines; +33% vs. 3 lines), and 2.12 M€ (5 lines; +18% vs. 4 lines; +57% vs. 3 lines). Upwind per-line cost decreases from 0.27 M€ (3 lines) to 0.21 M€ (4 lines) and 0.17 M€ (5 lines), while downwind per-line cost drops from 0.07 M€ to 0.04 M€. These unit-cost reductions reflect the progressive shift from long, heavy bottom chains to wire-rope segments with calibrated prestretch. Upwind per-anchor cost is lowest at 0.29 M€ (3 lines), peaks at 0.48 M€ (4 lines), then falls to 0.40 M€ (5 lines), whereas downwind anchors remain at 0.16 M€ across all cases. The upwind peak at four lines coincides with the strong footprint contraction (the anchor radius collapsing to 160 m) and the associated increase in vertical load component on gravity anchors. This requires a greater gravity anchor mass to preserve capacity. In the five-line optimal, the upwind radius relaxes to 198 m, reducing uplift and lowering per-anchor cost relative to the four-line case. Overall, the four-line layout offers a balanced compromise: it halves the upwind footprint relative to three lines and keeps total cost at 1.80 M€, while substantially reducing chain tonnage via rope introduction and device assistance. The five-line option further reduces per-line costs and chain usage, but total cost rises to 2.12 M€ because the additional line and anchor count outweigh unit savings. Operationally, a four-line layout offers the most balanced compromise between footprint and cost, whereas a five-line scheme is warranted when minimizing chain, tightening dynamic response, or increasing redundancy is paramount, and the higher upwind-anchor outlay is acceptable.

3.3. Algorithm Stability and Computational Footprint

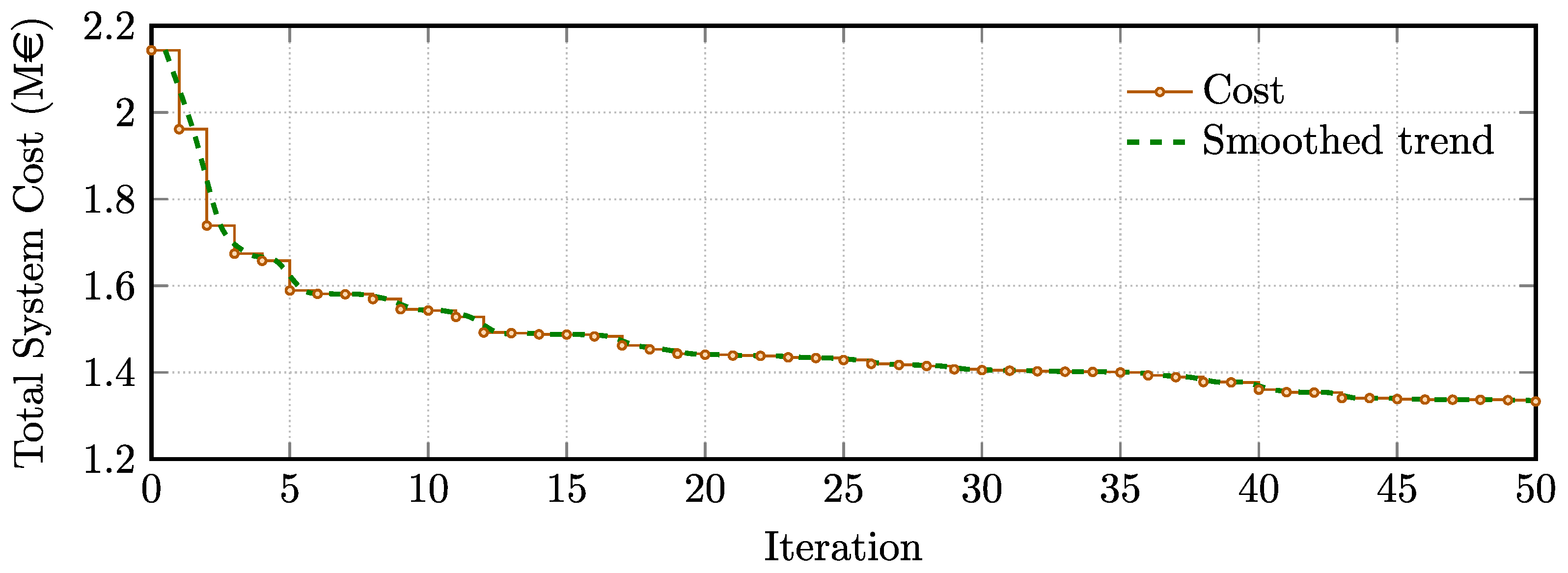

To illustrate the algorithm’s stability, a representative trace for the Catalonia 3-line case is reported. For each iteration, we record the minimum total system cost among feasible evaluations and plot the best-so-far value as a step curve (

Figure 5). This feasible-only trace summarizes progress toward cheaper, valid designs while avoiding penalized infeasible evaluations.

Across 50 iterations, the best-so-far total system cost decreases from 2.14 M€ to 1.33 M€ (−37.8%), with 18 improvements and the last improvement at iteration 44. In the early phase of the optimization, larger improvements emphasize the importance of global exploration of the search space, while the smaller improvements towards the end indicate the benefit of local exploitation of known solutions.

After iteration 44, the best-so-far value remains constant, indicating a stable plateau with no late drift in the objective. This confirms that the optimizer reaches stable performance before termination for the reported case.

The executed the optimization workflow described in [

25] on a virtual machine with 12 vCPUs and 12 GB RAM (Windows 11; Python 3.12; OrcaFlex 11.5c). A single particle evaluation that reaches a statically stable configuration in all load cases typically requires 10–15 s wall time. If static stability is not reached, the evaluation is aborted, and the assessment terminates sooner. The upper example with 100 particles assessed over 50 iterations (5000 evaluations) corresponds to the following serial compute time:

Assuming concurrent execution over 12 cores with parallel efficiency

, the estimated wall-clock time for a full execution is as follows:

It should be noted that many infeasible particles exit early (especially in the early stages of the optimization), which makes observed wall-clock times for the final reported designs fall within or below this bound.

Because compute cost is not the focus of this study and depends on implementation details (e.g., parallel strategy, caching, and stopping criteria), we report these values as order-of-magnitude estimates rather than precise benchmarks.