Experimental Investigation of a Novel Single-Shank Drag Anchor Design

Abstract

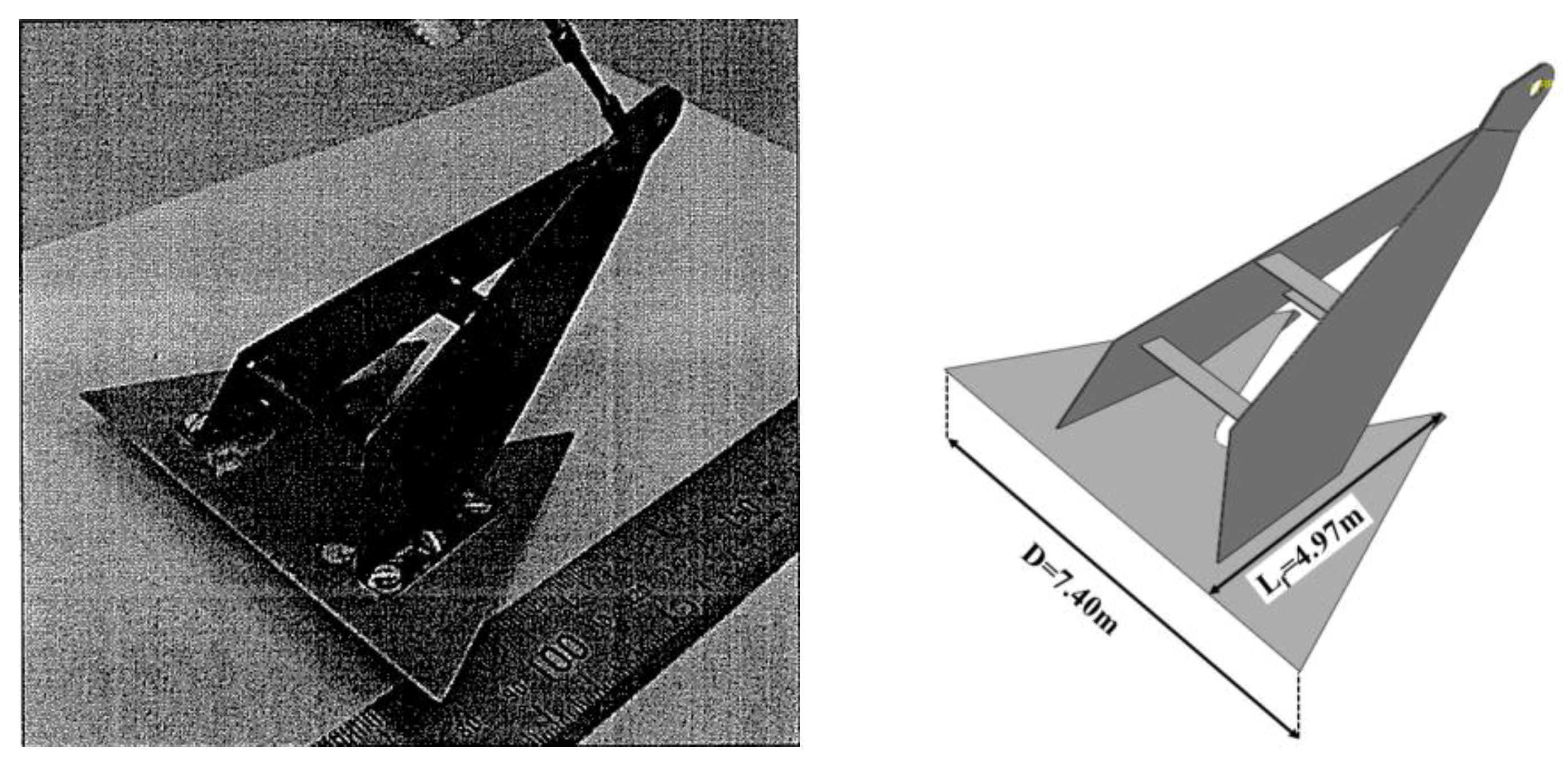

1. Introduction

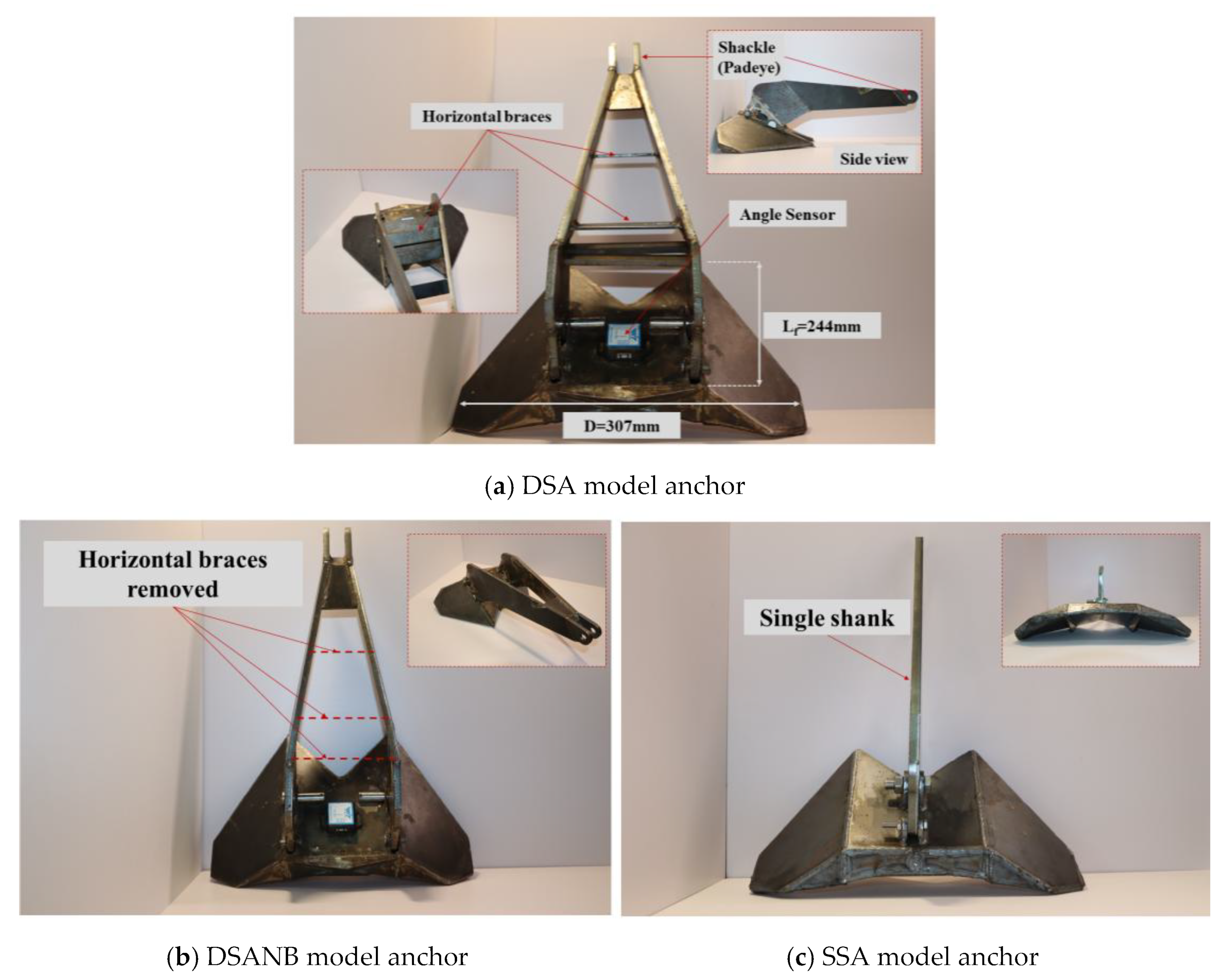

2. Methodology

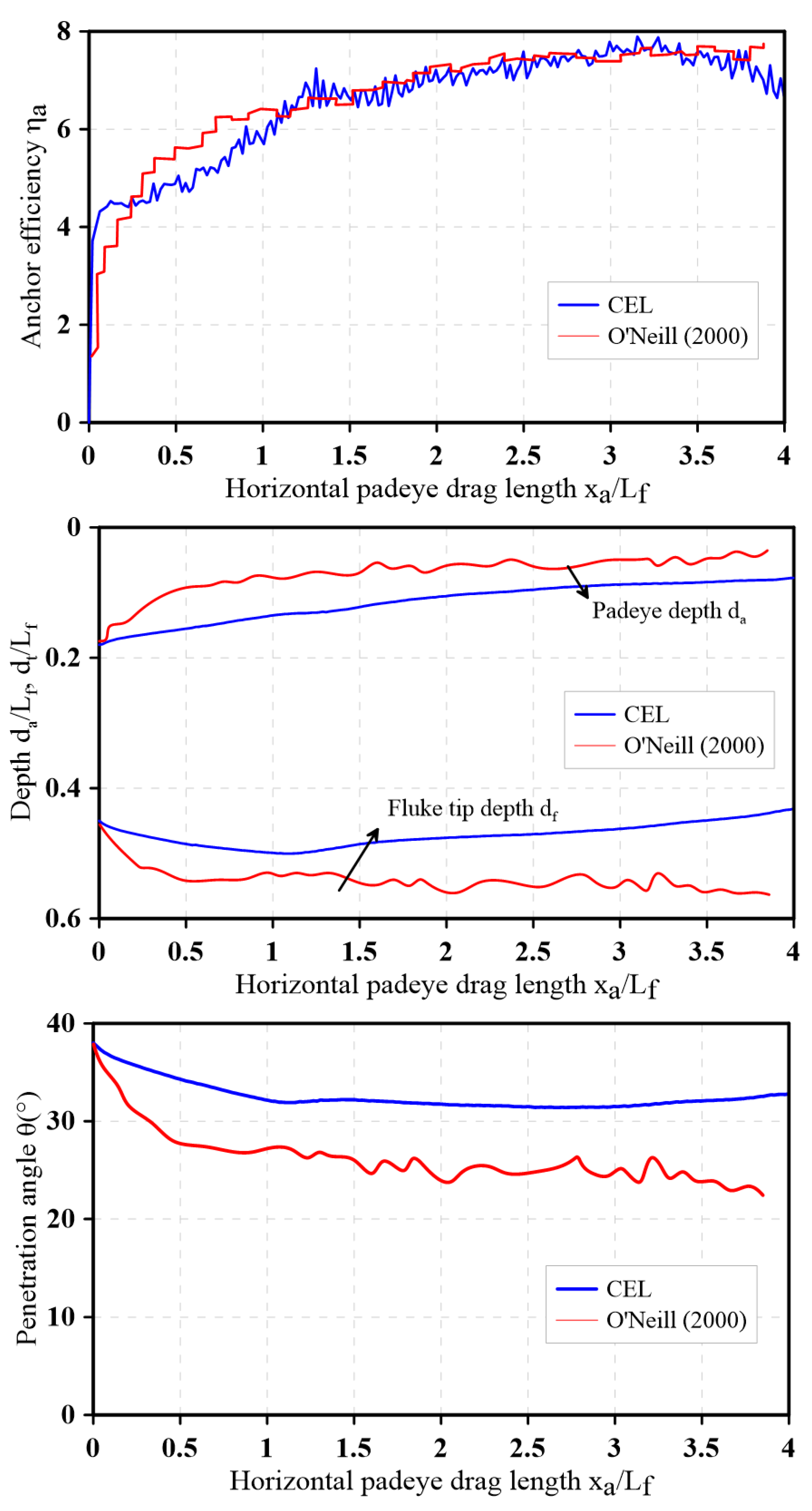

2.1. Coupled Eulerian–Lagrangian Method

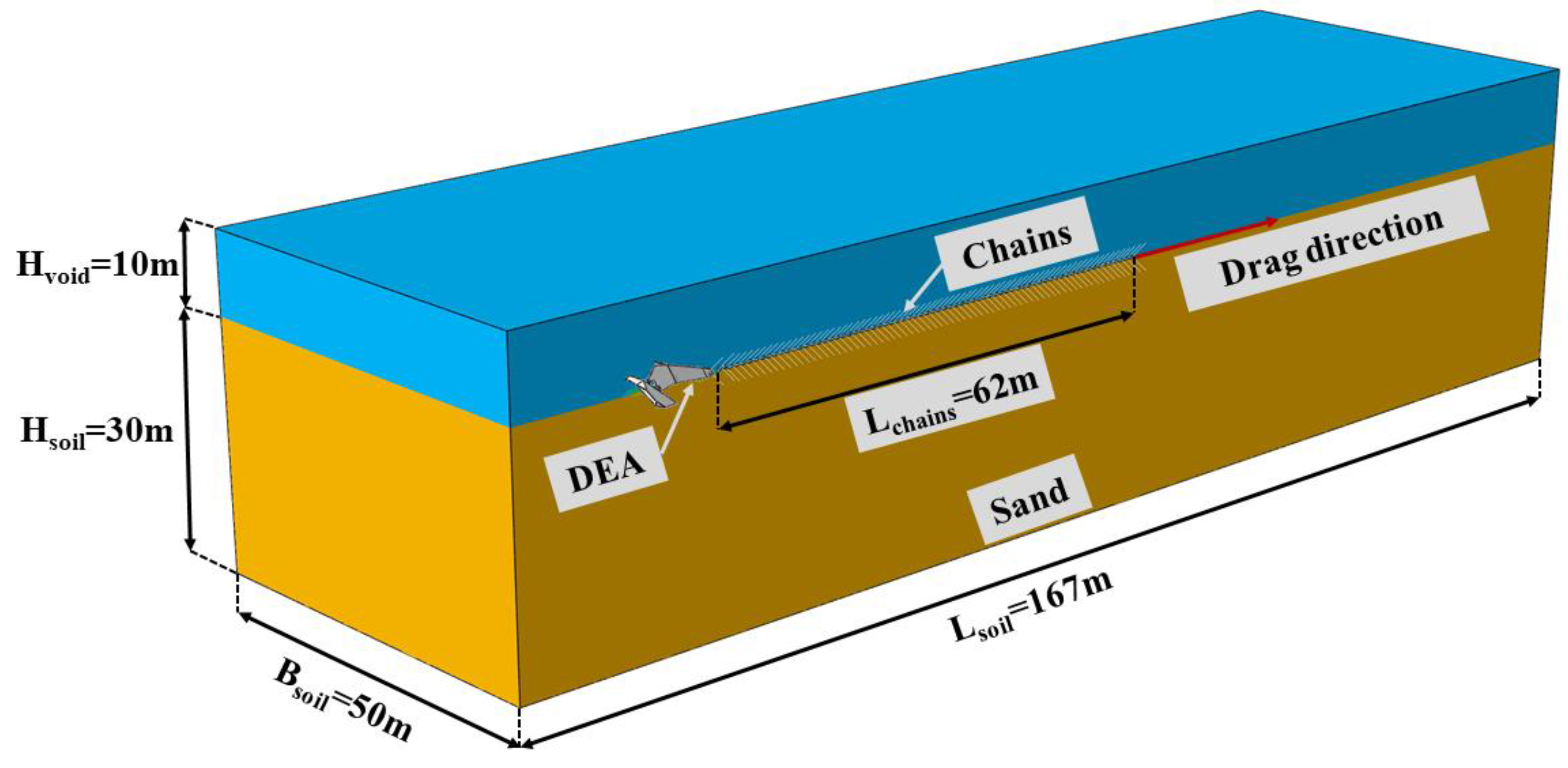

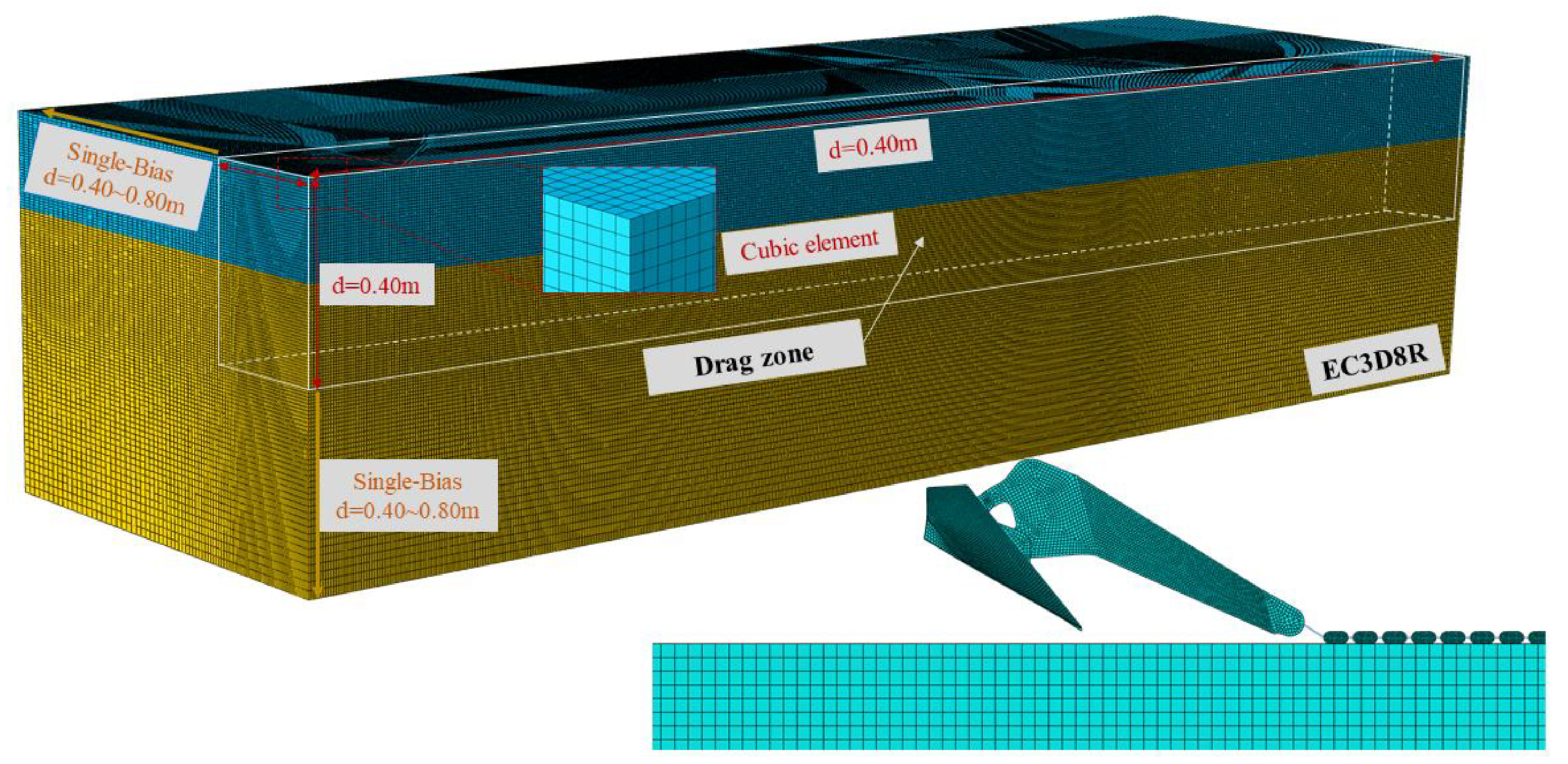

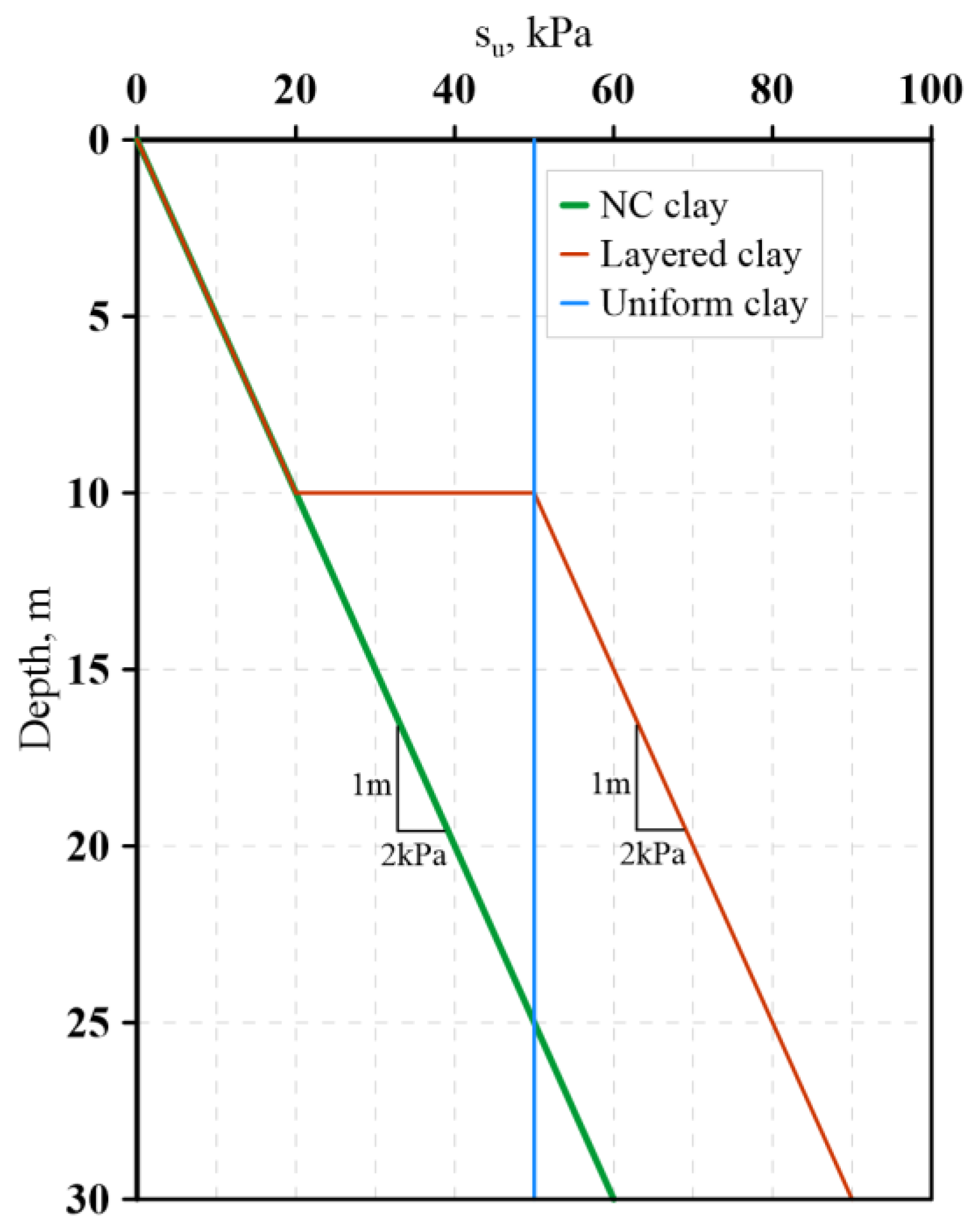

2.2. Simulation of the Drag Anchor and the Seabed Soil

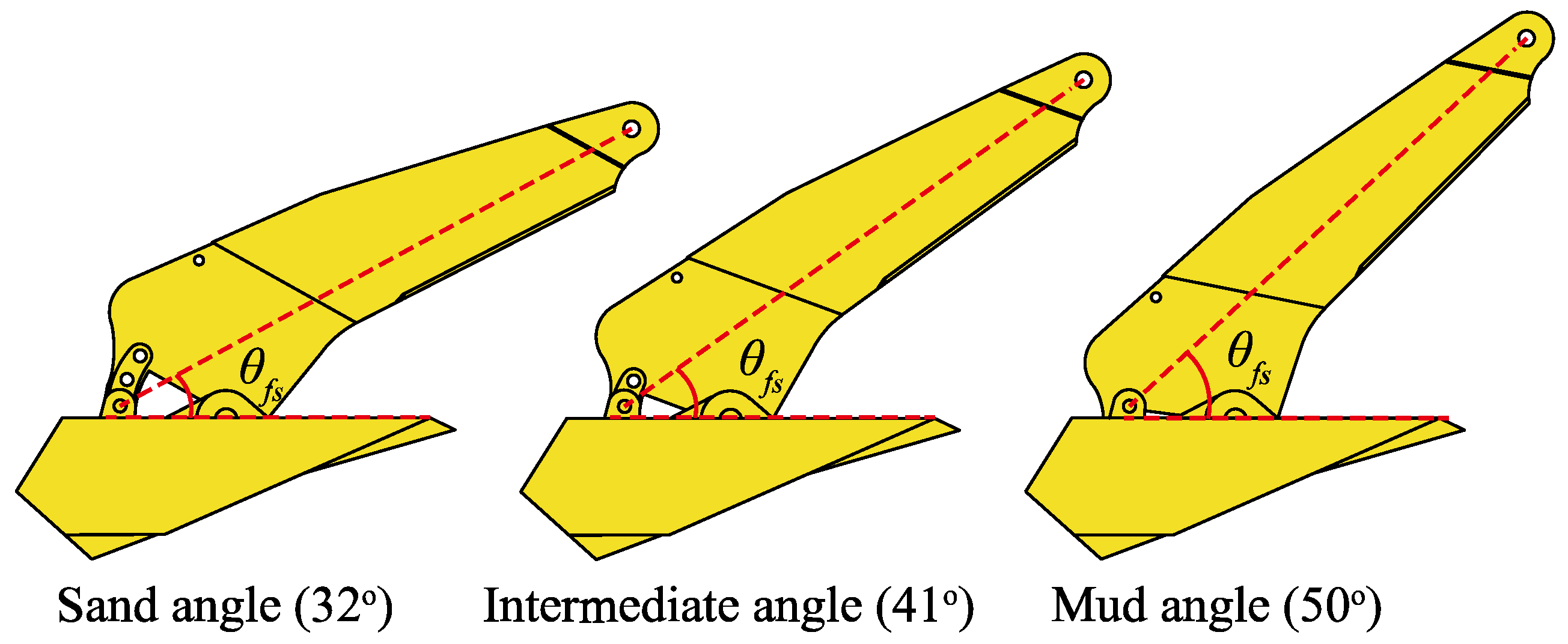

- θfs = 32°: in sand and medium to hard clays;

- θfs = 41°: in layered or complex soil conditions;

- θfs = 50°: in soft clay.

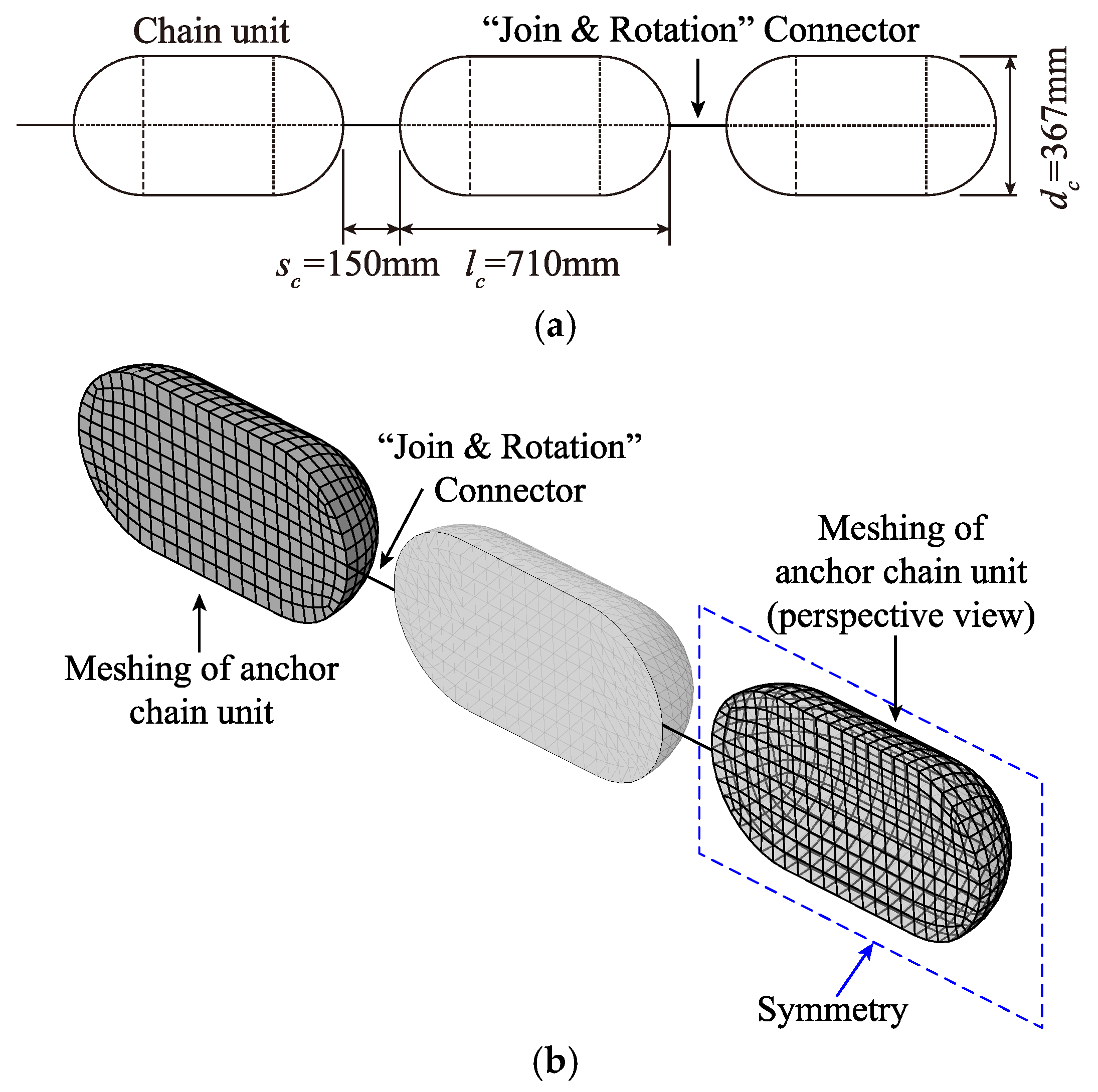

2.3. Simulation of the Chain

2.4. Analysis Steps and Boundary Conditions

- (1)

- The “geostatic” step. The purpose of this step is to generate the initial stress field within the soil domain.

- (2)

- The “initialization” step. Gravity is activated on the anchor and the chains in this step, and the anchor achieves a small initial penetration due to its weight.

- (3)

- The “drag” step. A horizontal pulling velocity is applied to the last chain unit, and the anchor penetrates the seabed under the pulling motion.

- For the Eulerian domain, side boundaries (including the bottom of the soil) are prescribed with a zero-velocity boundary condition normal to the surfaces.

- A Eulerian outflow boundary with a “no reflection” option is applied on the side boundaries of the Eulerian domain (except the bottom of the soil). This is essential for modeling infinite domains.

- The vertical symmetry plane of the model is assigned a symmetry boundary condition.

- A constant drag velocity is prescribed at the reference point (RP) of the last chain unit, which aims to simulate the dragging of the anchor-holding vehicle in practical engineering.

- The contact between the DEA and the soil, and the chain units and the soil, is defined using “general contact”. The tangential behavior follows the Coulomb friction law, with a friction coefficient of 0.5. The normal behavior is defined as “hard contact, allow separation after contact”.

2.5. Verification of the CEL Method Against Centrifuge Test

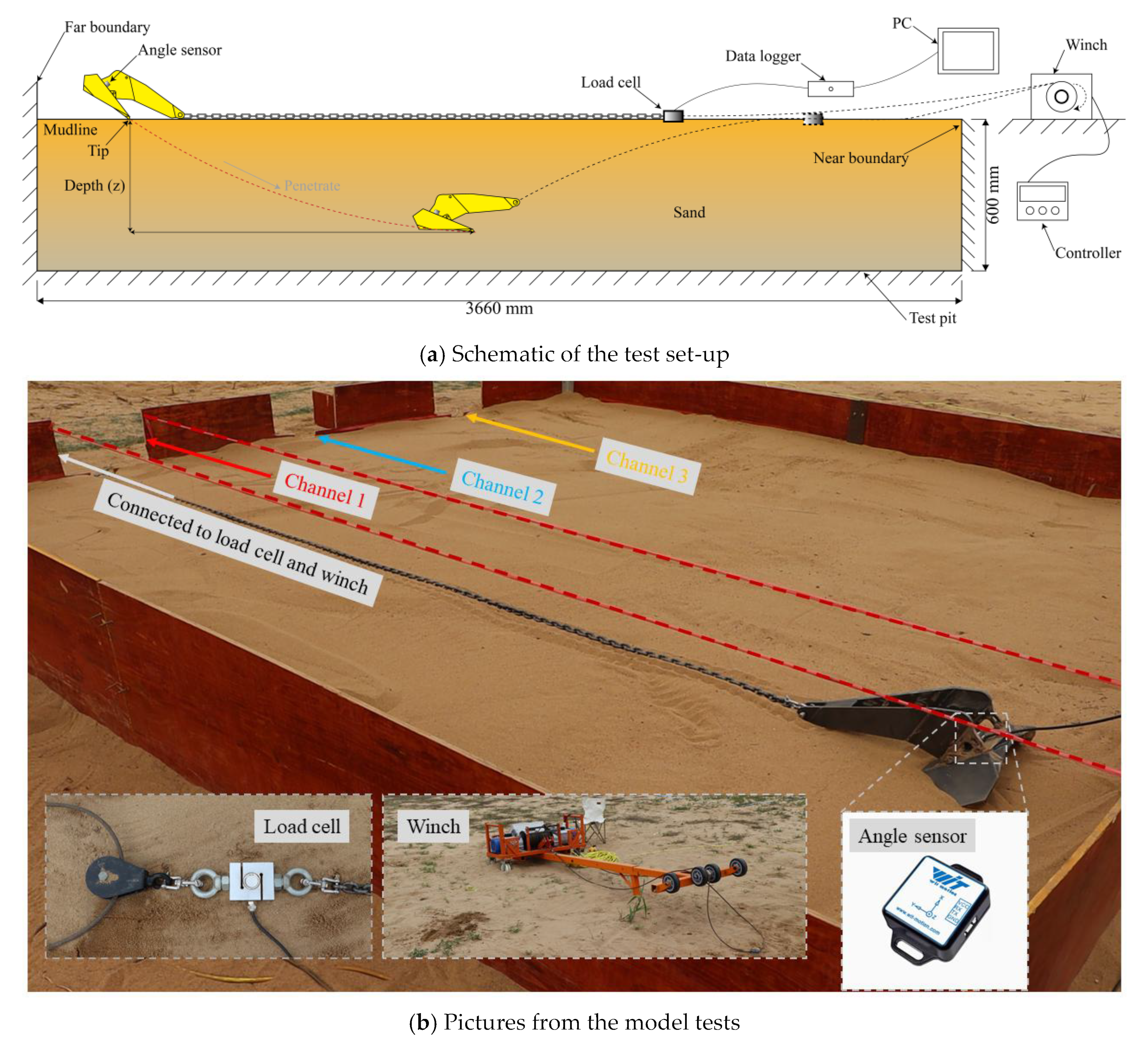

2.6. Set-Up of Model Tests in Sand

3. Results and Discussions

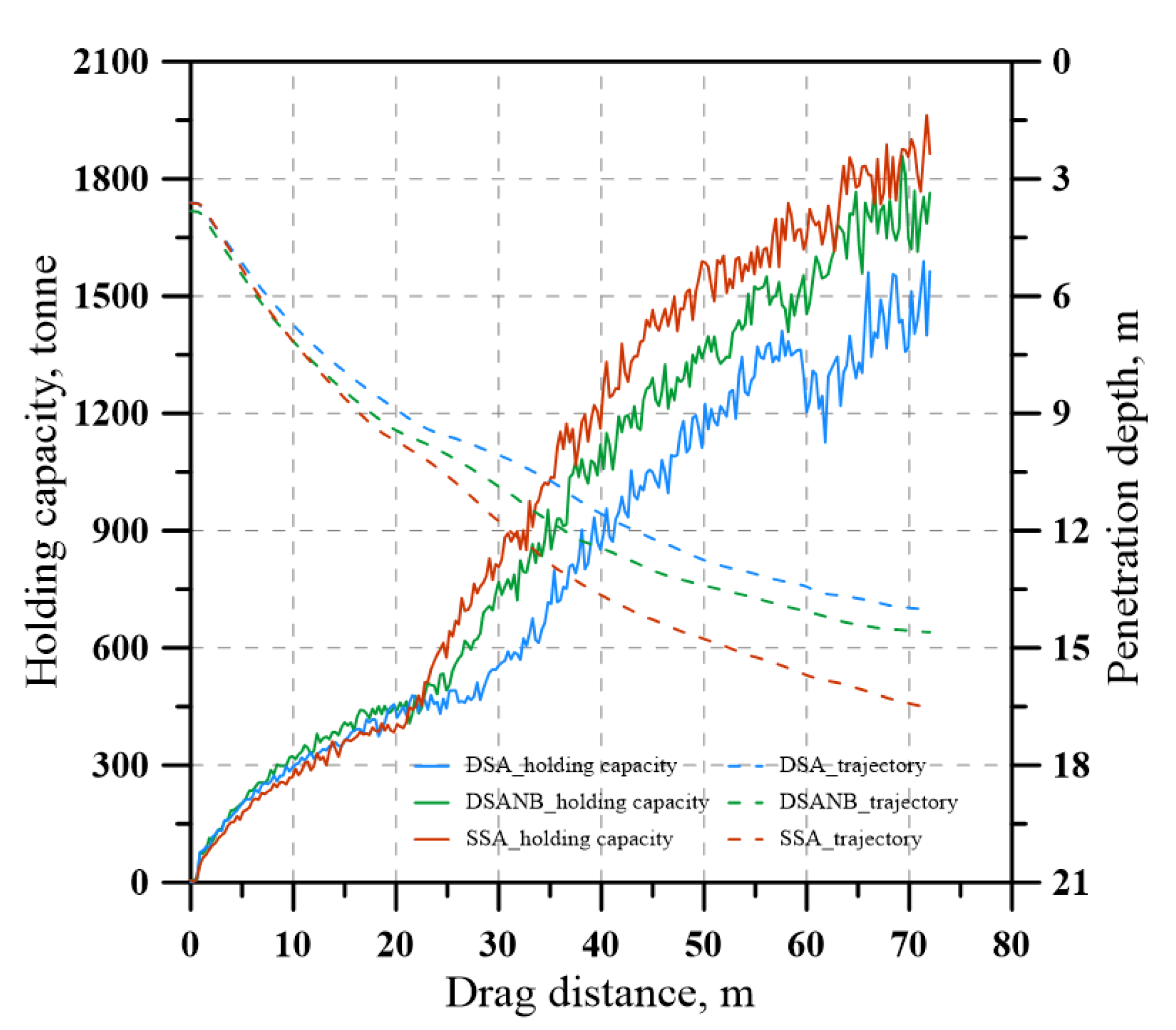

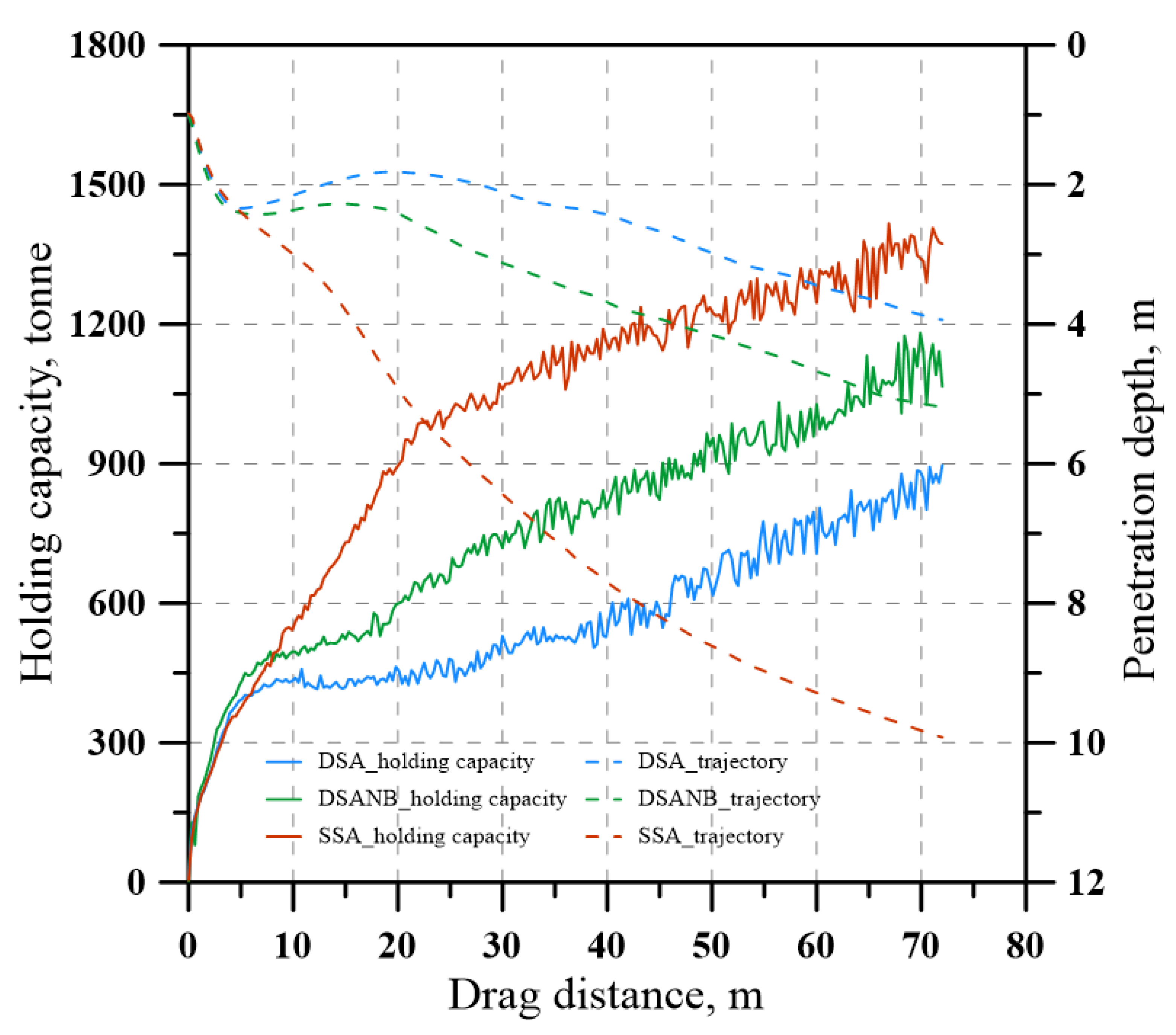

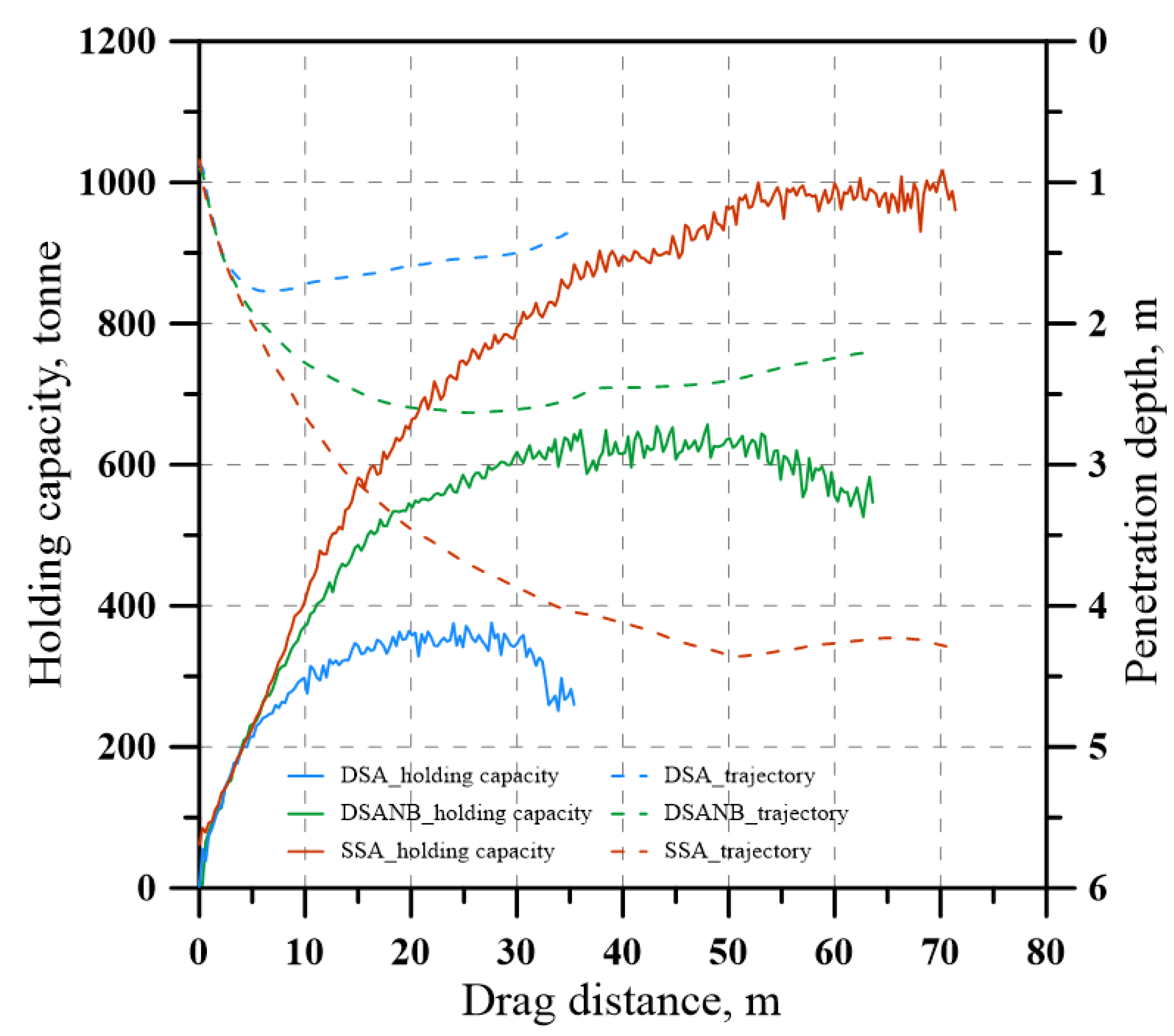

3.1. Results of Numerical Studies

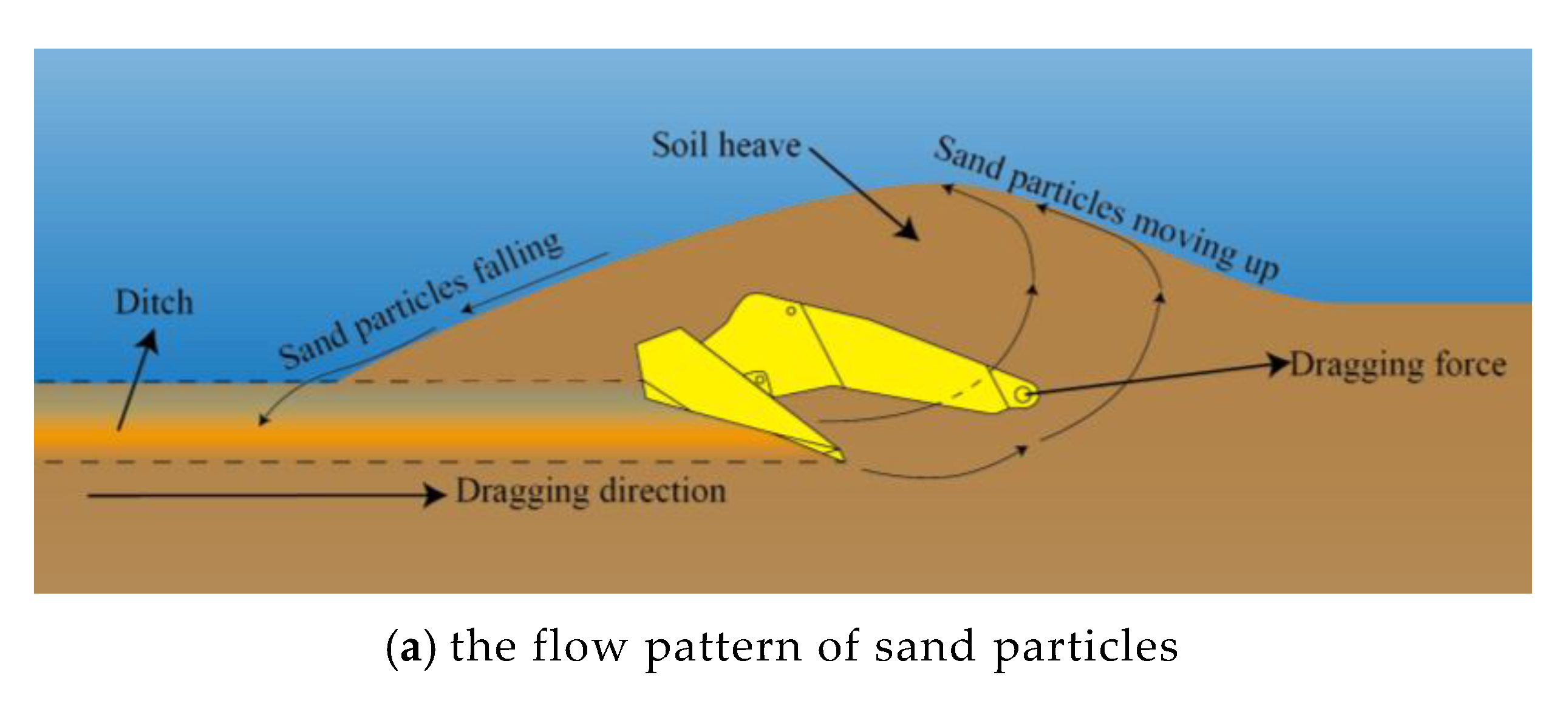

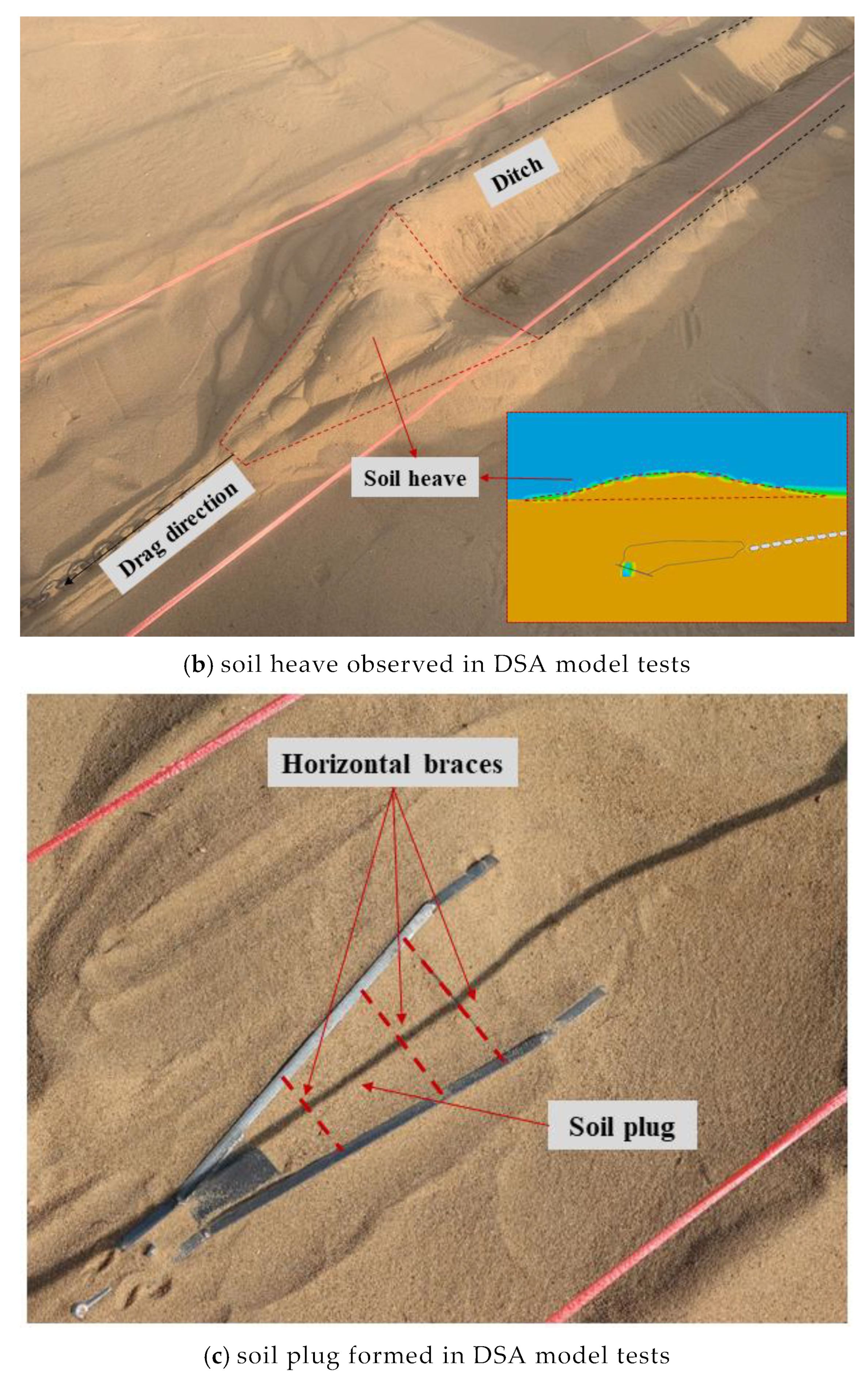

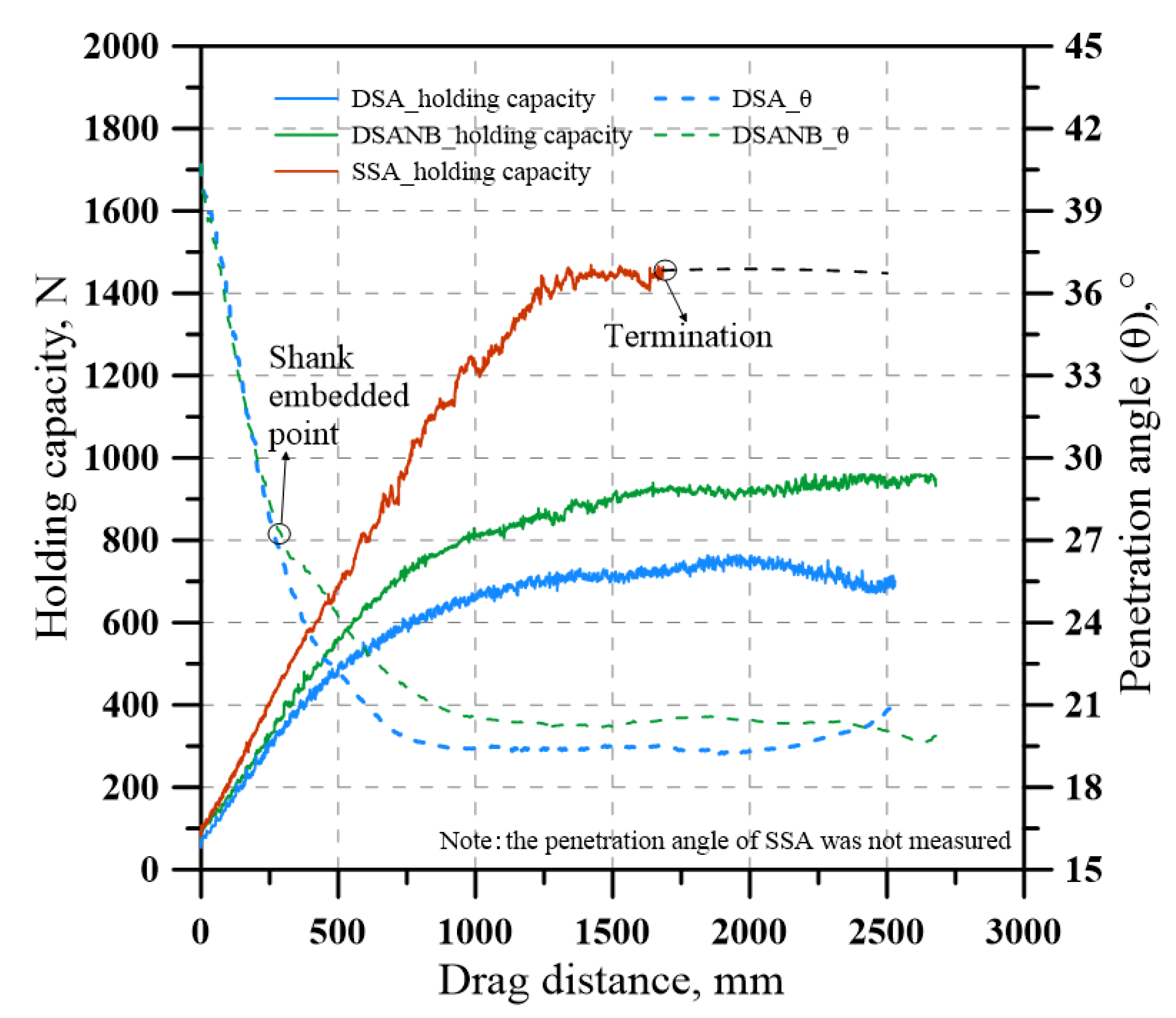

3.2. Results of the Physical Model Tests

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rui, S.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, Z.; Jostad, H.P.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Guo, Z. A review on mooring lines and anchors of floating marine structures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Rui, S.; Shen, K.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H.; Teng, L. Shared mooring systems for offshore floating wind farms: A review. Energy Rev. 2024, 3, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV-RP-E301; Design and Installation of Fluke Anchors. DNV: Høvik, Norway, 2021.

- Cerfontaine, B.; White, D.; Kwa, K.; Gourvenec, S.; Knappett, J.; Brown, M. Anchor geotechnics for floating offshore wind: Current technologies and future innovations. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubecker, S.R.; Randolph, M.F. The kinematic behaviour of drag anchors in sand. Can. Geotech. J. 1996, 33, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubecker, S.R.; Randolph, M.F. The static equilibrium of drag anchors in sand. Can. Geotech. J. 1996, 33, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.P. The Behaviour of Drag Anchors in Layered Soils. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C. Experimental investigation on the penetration mechanism and kinematic behavior of drag anchors. Appl. Ocean Res. 2010, 32, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Z. A novel kinematic model for drag anchors in seabed soils. Ocean Eng. 2012, 49, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bienen, B.; Nazem, M.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, J.; Pucker, T.; Randolph, M.F. Large deformation finite element analyses in geotechnical engineering. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 65, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vryhof Manual. In The Guide to Anchoring; Vryhof: Schiedam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-90-9028801-7.

- Dassault Systemes. Abaqus/CAE User’s Guide; Dassault Systemes: Waltham, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, W.F. CEL: A Time-Dependent, Two-Space-Dimensional, Coupled Eulerian-Lagrange Code (No. UCRL-7463, 4621975); University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.J. Computational methods in Lagrangian and Eulerian hydrocodes. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1992, 99, 235–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.J.; Okazawa, S. Contact in a multi-material Eulerian finite element formulation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2004, 193, 4277–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Zhao, P.; Peng, X.; Wang, S. Numerical modeling of large deformation and nonlinear frictional contact of excavation boundary of deep soft rock tunnel. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 3, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tho, K.K.; Leung, C.F.; Chow, Y.K.; Swaddiwudhipong, S. Eulerian finite element simulation of spudcan–pile interaction. Can. Geotech. J. 2013, 50, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tho, K.K.; Leung, C.F.; Chow, Y.K.; Swaddiwudhipong, S. Eulerian Finite-Element Technique for Analysis of Jack-Up Spudcan Penetration. Int. J. Geomech. 2012, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, J.; Qiu, G.; Wu, L. Numerical simulation of the penetration process of ship anchors in sand. Geotechnik 2015, 38, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, K.; Li, L.; Guo, Z. Integrated analysis of drag embedment anchor installation. Ocean Eng. 2014, 88, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, P.; Lei, D. Numerical Investigation of the Installation Process of Drag Anchors in Sand. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Feng, X.; Neubecker, S.R.; Bransby, M.F.; Gourvenec, S.; Randolph, M.F. Numerical Study of Mobilized Friction along Embedded Catenary Mooring Chains. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubeny, C.; Gilbert, R.; Randall, R.; Zimmerman, E.; McCarthy, K.; Chen, C.-H. The Performance of Drag Embedment Anchors (DEA); Texas A & M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Heurlin, K.; Rességuier, S.; Melin, D.; Nilsen, K. Comparison between FEM analyses and full-scale tests of fluke anchor behavior in silty sand. In Frontiers in Offshore Geotechnics III; Meyer, V., Ed.; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 875–880. [Google Scholar]

| d10 mm | d50 mm | Dry Density γd, (g·cm−3) | Water Content w, % | Relative Density Dr, % | Internal Friction Angle φ, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.13 | 0.30 | 1.473 | 0.93 | 33 | 35.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, C.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lei, D. Experimental Investigation of a Novel Single-Shank Drag Anchor Design. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112157

Wu C, Guo P, Zhang Y, Wang X, Lei D. Experimental Investigation of a Novel Single-Shank Drag Anchor Design. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112157

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chuheng, Peng Guo, Youhu Zhang, Xiangyu Wang, and Di Lei. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of a Novel Single-Shank Drag Anchor Design" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112157

APA StyleWu, C., Guo, P., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., & Lei, D. (2025). Experimental Investigation of a Novel Single-Shank Drag Anchor Design. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112157