Abstract

Automated berthing remains a critical challenge for autonomous surface vessels (ASVs), necessitating precise berthing state estimation as a fundamental prerequisite. In this paper, we present a novel berthing state estimation method tailored for ASVs and based on 3D LiDAR technology. Firstly, a berthing plane acquisition scheme based on point cloud plane fitting is proposed; the feasibility of the scheme was verified by experiments. The point cloud registration algorithm was used to realize the ship pose estimation. Before registration, the preprocessing technology was used to filter out the noise and outliers in the point cloud data to improve the accuracy of pose estimation. A detailed method for calculating the berthing state information is proposed. This method considers the influence of ship roll, pitch, and yaw during berthing, and ensures the accuracy of the obtained state information. Finally, a real-time ship berthing perception framework was constructed using the Robot Operating System (ROS), enabling the continuous output of vital berthing state information, including berthing distance, velocity, approaching angle, and yaw rate, at a frequency of 10 Hz. To validate the effectiveness of our algorithm, extensive real ship experiments were conducted, yielding highly promising results. The average angle error was found to be less than 0.26°, with an average distance error below 0.023 m.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Maritime transport carries 90% of the volume of world trade, and ships play an important role as a tool for maritime transport. However, marine transportation often faces complex and dangerous environments, and any accident may cause serious economic losses and environmental pollution. Studies have shown that more than 75% of maritime accidents can be attributed to human error [1]. Aiming at this problem, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) proposed the concept of intelligent ships, that is, ships that can operate independently and interact with humans to varying degrees [2]. In addition, compared with conventional ships or fully manned ships, autonomous surface vessels (ASVs) show many advantages, such as improving shipping safety, reducing environmental pollution, and saving transportation costs [3,4,5].

To achieve real autonomous navigation at sea, ASVs require many key technological problems to be solved, and automatic berthing is one of them [6]. The berthing task of a ship is complex; it is easy to collide with other ships and port facilities due to the limitation of port space [7,8]. In addition, when the ship is close to the berth, it is difficult to predict the ship’s motion due to the influence of wind, waves, current, shallow water, and bank effects [9,10]. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately estimate the berthing state of a ship during the berthing process to provide a reference for the control module.

1.2. Related Work

To address the aforementioned challenge, extensive research has been conducted by experts and scholars in the field. Initially, the measurement of ship position and speed relied predominantly on global positioning system (GPS) or differential global positioning system (DGPS) sensors, while angle information, such as ship heading, was obtained using magnetic or electric compasses. However, it has been demonstrated that these conventional sensors fail to meet the precision requirements for ship berthing [11,12]. In recent years, novel sensors have emerged as valuable aids in the process, including sonar, cameras, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), radar, LiDAR, and more. Sakakibara and Kubo used shore-based sonar to measure the distance and speed of a ship from a berth [13]. Ref. [14] used two stereo cameras to measure the berthing distance of ships. Ref. [15] estimated the distance between the ship and the wharf based on cameras, a DGPS, and an IMU. Ref. [16] used a microwave radar array to detect the distance from the ship to shore.

Although these approaches provide berthing perception information, they are constrained by the inherent limitations of the sensors. Cameras are sensitive to illumination and weather conditions, often leading to substantial measurement errors [17]. Low-resolution sonar and radar can reduce estimation accuracy [18], while IMUs accumulate drift over time, compromising long-term reliability [19]. Moreover, advanced data processing techniques, such as ensemble learning, have shown significant potential in enhancing recognition accuracy in related motion perception tasks, including highway merging scenarios [20].

In contrast to the aforementioned sensors, LiDAR has gained significant prominence in berthing state estimation in recent years. This can be attributed to LiDAR’s ability to furnish more dependable and precise distance measurements compared to the aforementioned sensors. It is important to note that LiDAR sensors are unsuitable for inclement weather conditions such as rain, snow, and heavy fog. Nevertheless, in such harsh weather conditions, ships usually do not engage in berthing operations, thereby mitigating the impact of this limitation on berthing status estimation.

Research on LiDAR-aided autonomous ship berthing primarily falls into two distinct paradigms, distinguished by the deployment location of the sensor: shore-based systems and ship-based systems. In shore-based systems, the LiDAR is fixed on the quay wall, providing a stable reference frame for measuring the relative distance, velocity, and attitude between the berth and the approaching vessel. This configuration is particularly suited for port infrastructure integration. For example, ref. [21] developed a support system that integrates laser rangefinders with marine hydrometeorological sensors, whereby distance measurements are complemented by real-time wind and wave data to enhance situational awareness. Similarly, aiming to improve port efficiency and safety, ref. [22] described a laser docking system for container terminals designed to deliver high-precision berthing information to pilots. Further advancing the capabilities of shore-based sensing, ref. [23] proposed a novel computational method for extracting multi-point motion pose information, enabling the derivation of a vessel’s speed, distance, and heading to assist in complex maneuvers such as parallel berthing.

Compared with the shore-based LiDAR fixed berthing system, the ship-based LiDAR berthing system has a wider coverage and is more flexible. Ref. [24] combined sensor 3D LiDAR, IMU, and GPS data to build a situational awareness system that extracts the geometric features of the floating platform and estimates the position and direction of the ASV relative to the berthing facility. Based on map, LiDAR, and ultrasonic distance sensors data, ref. [25] developed an algorithm to calculate safe operating areas to assist ship berthing. The sensor data can deal with objects such as inaccurate maps and undrawn berthing ships on the map. Ref. [26] proposed a method for calculating ship berthing parameters by combining multi-solid LiDAR point cloud and millimeter wave radar data, and they verified the algorithm using real ship experiments. Ref. [27] proposed a ship-berthing state perception framework based on 3D LiDAR. The framework needs to be based on a shoreline GPS position prior to obtaining more accurate berthing status information. Furthermore, accurately estimating a vessel’s orientation is critical, as evidenced by advances in deep learning for ship detection, where rotation feature decoupling techniques enable precise orientation awareness [28].

From the analysis above, we can see that, although some successful schemes for the research of ship-borne LiDAR berthing state estimation exist, these schemes either require a combination of multiple sensors, are complex, or require prior port GPS positioning, resulting in measurement errors. This paper proposes a new ship-borne 3D LiDAR berthing state estimation scheme for ASVs. The implementation of this scheme only needs a LiDAR sensor, which has high accuracy and can output berthing state information with a frequency of 10 Hz in real time. The proposed method takes into account the roll, pitch, and yaw of the ship and does not require GPS position prior to this.

1.3. Contributions

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- Our foremost contribution is the proposition of a novel method that directly utilizes point cloud data to calculate berthing state information. By extracting a berthing plane from point clouds, we eliminate the need for prior shoreline GPS positions, and more accurate state estimation is achieved.

- (2)

- We introduce a detailed methodology for calculating berthing state information solely based on point cloud data. These parameters encompass berthing distance, berthing angle, berthing speed, and yaw rate. Importantly, our approach accounts for the dynamic changes in ship pose during berthing, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of state estimation.

- (3)

- To facilitate seamless integration and real-time calculations, we construct a berthing state perception framework based on the renowned point cloud library (PCL) and the versatile Robot Operating System (ROS). This framework empowers ASVs with the capability to continuously compute four essential types of berthing state information in real time.

- (4)

- Our proposed algorithm underwent rigorous verification through real ship experiments, meticulously evaluating its performance and accuracy. The evaluation results affirm the real-time performance and accuracy of our berthing state estimation framework.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the principle of the plane fitting algorithm and the berthing state estimation algorithm. The real ship experiment is covered in Section 3, including the experimental environment and equipment, experimental design, experimental results, and results evaluation. Section 4 discusses the advantages and disadvantages of the plane fitting algorithm and the advantages and limitations of the berthing state estimation scheme. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of this research and future work.

2. Plane Fitting Methods and Berthing State Estimation

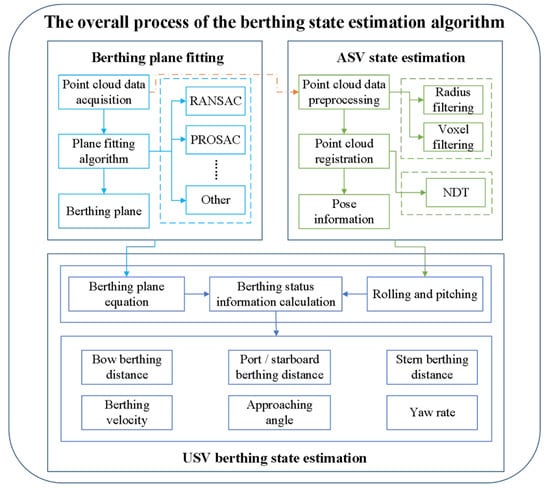

Figure 1 presents the overall workflow of the berthing state estimation algorithm. The algorithm is composed of three main modules: berthing plane fitting based on 3D LiDAR, the estimation of a ship’s own state, and the estimation of a ship’s state relative to the berth. First, the berthing plane is extracted from the LiDAR point cloud by applying a plane fitting algorithm, and the corresponding plane equation is derived. Subsequently, the point cloud is preprocessed through radius filtering and voxel filtering, and the ship’s pose is obtained using a point cloud registration algorithm. Finally, by combining the berthing plane equation with the estimated ship pose, key berthing parameters are computed through the berthing state estimation algorithm, including berthing distance, berthing angle, berthing speed, and yaw rate.

Figure 1.

Flow box diagram of the berthing state estimation algorithm.

2.1. Berthing Plane Fitting Methods

Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) [29] and its variants, least squares (LS) [30,31], Least Median of Squares (LMedS) [32], and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [33] are common plane fitting methods. The RANSAC algorithm and its variants’ processes are similar. Therefore, this part only introduces the four algorithms of RANSAC, LS, LMedS, and PCA to fit the berthing plane process.

2.1.1. RANSAC

RANSAC is a random parameter-estimation algorithm. RANSAC divides data points into inner points and outer points. The ultimate goal is to eliminate the outer points as much as possible and retain the inner points as much as possible. Unlike other algorithms, the RANSAC algorithm does not use all the initial data to obtain an initial solution and then eliminate invalid data. Instead, it uses as few initial data points as possible to meet feasible conditions and uses a consistent data set to expand it. This idea is about finding models to fit data and has a wide range of applications in the field of computer vision [34].

The RANSAC algorithm can be summarized into two steps: first, a minimum sample subset that meets the conditions is randomly selected from the existing data samples, and then the corresponding model parameter values are calculated using the initial subset; finally, the deviation between all sample data and this model is calculated. A pre-set threshold is used to compare with this deviation. When the deviation is less than the threshold, the point is determined to be an inner point; otherwise, the outer point is removed. The number of inner points is recorded during the determination process, and this process is repeated until the end of all point cloud determination. In this way, an iteration is completed, and the total number of interior points and the parameter values of the model are recorded at the end of each iteration. After the whole iteration, the calculated optimal model parameters are the final model parameter estimators. The process of plane fitting using RANSAC combined with the eigenvalue algorithm is as follows:

- (1)

- Three points were randomly selected to calculate the model parameters according to the plane equation ax + by + cz + d = 0.

- (2)

- Calculate the distance from the remaining point to the plane equation, and compare the distance with the set threshold. If it is less than the threshold, the point is the interior point; otherwise, it is the outer point. Count the number of interior points under the parameter model.

- (3)

- Continue to perform the above two steps. If the number of interior points of the current model is greater than the maximum number of interior points that have been saved, the new model parameters are changed, and the model parameters are always those with the largest number of interior points.

- (4)

- Repeat the above three steps, iterate until the iteration threshold is reached, find the model parameters with the largest number of interior points, and finally, use the interior points to estimate the model parameters again to obtain the final model parameters.

2.1.2. Least Squares

The least square method is used to find the best function matching regarding data by minimizing the sum of squared errors, which is often used in a straight line, curve fitting, plane fitting, and so on. In the case of fitting a plane, the goal is to find a plane that minimizes the sum of Euclidean distances between the plane and all data points.

Assuming that there is a discrete point cloud , in the space, plane fitting is performed. The plane equation is

where a, b, c, and d are the parameters. Suppose ; then,

where , , and . According to the principle of least squares, the sum of squared errors is minimized, namely

The partial derivatives of , , and are derived, and the derivative is 0. A simplified version can be obtained:

2.1.3. LMedS

Like the RANSAC algorithm, the LMedS algorithm can estimate the parameters of the mathematical model iteratively from a set of observation data sets containing outliers. The algorithm was first proposed by Rousseeuw in 1984. Its basic idea is given by Equation (5). It is a random parameter estimation algorithm, and it is robust against noise and abnormal data.

where is the median of the residual squares of each subset and all other samples in the sample set, and the one with the smallest median of the residual square corresponding to all subsets is selected as the model to be estimated. Subsequently, adaptive discrimination between inliers and outliers is achieved by calculating weights for each data point based on a robust standard deviation, as defined in Equation (6):

represents the robust standard deviation, n is the total number of samples, and p represents the minimum number of samples required to calculate the model parameters. The final classification is performed using the screening criterion specified in Equation (7):

is the weight of the ith sample, the weight of 1 is the internal point, and the weight of 0 is the external point; represents the residual between the ith sample and the estimated model. Furthermore, the number of iterations, k, for this algorithm can be determined using Equation (8).

where j represents the minimum number of samples required to compute the model parameters; q denotes the probability of obtaining at least one good sample subset, typically set between 0.95 and 0.99; and is the inlier ratio, defined as the proportion of inliers within the total sample set. It should be noted that LMedS can estimate the sample set containing 50% noise at most, without affecting the reliability of the results.

2.1.4. PCA

PCA is a common data analysis method that is often used for the dimensionality reduction of high-dimensional data, and it can be used to extract the main feature components of data. PCA minimizes the variance of the data by subtracting the mean from the corresponding variables and then performs eigenvalue decomposition (EVD) on the covariance matrix. Since the covariance matrix is symmetric, its eigenvalues and eigenvectors can be directly obtained through EVD, which yields the required number of principal components.

The plane equation is shown in Equation (1), and the observed covariance matrix is

where represents the i-th 3D point as a column vector, denotes the barycenter value of the observed data, and the eigenvalues are solved by the covariance matrix. The minimum three eigenvalues are , , and . The corresponding eigenvectors are , , and , respectively. Then, corresponds to the plane normal vector . Using the mean value of the x, y, and z directions of the point cloud, the parameter d can be obtained from Equation (11):

Bring a, b, c, and d into Equation (1) to get the fitted plane equation.

2.2. ASV State Estimation Method

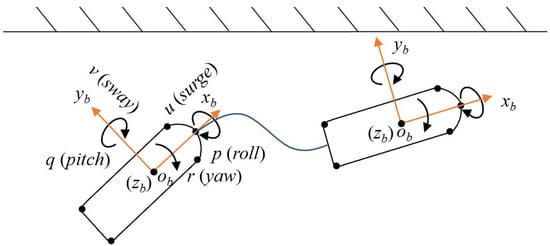

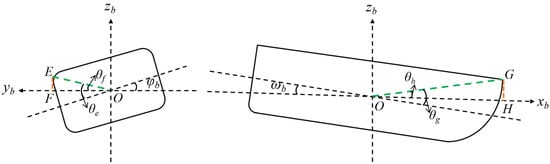

Figure 2 depicts a schematic of the ship’s motion during the berthing process. As illustrated in the figure, the ship’s motion encompasses both translational motion along the coordinate axis and rotational motion around the axis. Throughout the berthing procedure, real-time data from the surrounding environment is collected via a LiDAR sensor, enabling the acquisition of the ship’s current motion state. This is accomplished by leveraging the point cloud data from the current frame, as well as the local map point cloud data, through the utilization of a point cloud registration algorithm. It is worth noting that the original point cloud data is prone to containing numerous noise elements and outliers. Incorporating the original point cloud data directly into the registration process would adversely impact both the speed and accuracy of the registration. Consequently, it is customary to preprocess the original point cloud data prior to registration, with the goal of reducing the quantity of point clouds and eliminating outliers. By adopting this approach, real-time and accurate registration can be achieved.

Figure 2.

Ship motion diagram.

2.2.1. Point Cloud Preprocessing

In this paper, we employ radius filtering and voxel filtering techniques for preprocessing point cloud data. Radius filtering involves determining the number of neighboring points within a specified radius for each point. Points with a count of neighboring points below a threshold are filtered out. This approach effectively eliminates noise and outliers from the data.

On the other hand, voxel filtering entails the creation of a three-dimensional voxel grid for the input point cloud data. Within each voxel, the center of gravity of all points contained within it is calculated, serving as an approximate representation of the other points within the voxel. By utilizing this method, all points within a voxel are effectively represented by a single center of gravity point. The voxel filtering technique enables downsampling while preserving the underlying geometric structure of the point cloud itself.

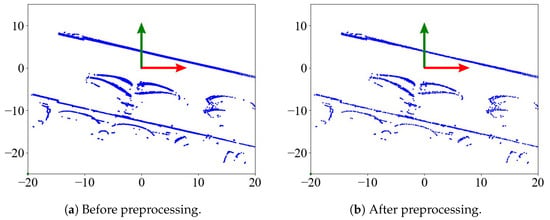

In Figure 3a, we present the point cloud diagram before preprocessing during berthing, with the red and green arrows indicating the bow and port directions, respectively. Figure 3b depicts a schematic diagram of the point cloud after preprocessing. As observed from the figure, the number of point clouds is significantly reduced after preprocessing, while the geometric structure remains unchanged.

Figure 3.

Point cloud preprocessing.

2.2.2. Point Cloud Registration

This paper implements point cloud registration based on the normal distribution transformation (NDT) algorithm. The basic process is as follows: given the source point cloud and the target point cloud , we have . Firstly, the space covered by the target point cloud is divided into voxels. For the j-th voxel, let the set of points contained in it be . Then, the mean and covariance matrix of the points in voxel are computed as

The probability density function for approximating the distribution of points inside voxel is

where D represents the dimension. The total likelihood of the transformed source point cloud in the corresponding distributions of all voxels is maximized, and the optimal transformation matrix is

Finally, the Newton iteration method is used to optimize the parameters and complete point cloud registration.

2.3. Berthing State Estimation Method

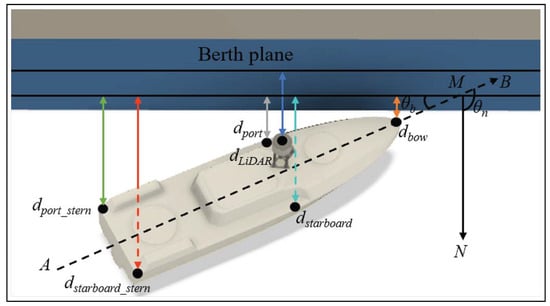

The parameters a, b, c, and d of the berthing plane equation can be obtained by the plane fitting algorithm. Figure 4 is a schematic diagram of ship berthing, in which the two-way arrow is the distance from each point on the ship to the berthing plane, is the angle between the bow and stern line of the ship and the berthing plane, and is the plane normal. Figure 5 shows a sketch of ship roll and pitch, respectively, where is the roll angle, and is the pitch angle. The specific values of the two can be obtained by the NDT algorithm. Suppose that the coordinates of a point on the ship are (, , ). When the roll and pitch of the ship are not considered, the distance from the point to the plane can be obtained by the following formula:

Figure 4.

Ship berthing state diagram.

Figure 5.

Roll and pitch.

The length of the ship is , the width of the ship is , and the height of the ship is . If roll and pitch are considered, it can be seen from Figure 5 that when the ship berths on both sides, the distance from the ship sides to the berthing plane is reduced by . Similarly, when the ship berths, the distance from the bow and stern to the berth is reduced by . According to Figure 5,

Therefore,

Similarly,

Therefore, the berthing distance is

Remark 1.

The three formulas in Equation (23) correspond to the berthing distance of two sides of a berthing, bow and stern berthing, and other forms of berthing.

It can be seen from Figure 4 that the approaching angle = − , is the angle between the ship’s bow and stern line and the plane normal vector ; then,

Figure 6 shows the berthing distance and angle. The partial components , , and of the berthing speed can be expressed by Equation (25), and the yaw rate is estimated by Equation (26).

Figure 6.

Berthing distance and angle.

In addition to the speed calculated by the above berthing distance, the berthing speed also includes the speed component generated by the yaw rate, as depicted in Figure 7. The overall berthing speed, denoted as , , , can be expressed using the following formula.

Figure 7.

Berthing velocity.

3. Experiment

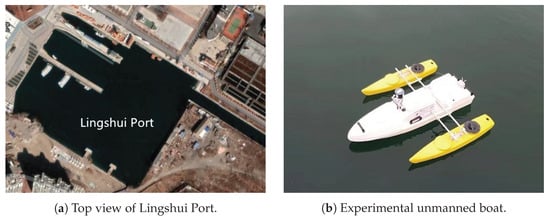

The experimental site is “Lingshui Port” in Dalian, China, as shown in Figure 8a. The experimental ship is “Zhilong 1”, an unmanned boat with double propellers and double rudders.

Figure 8.

Port and unmanned boat.

The basic parameters of the USV are summarized as follows: the overall length is 175 cm, the beam is 50 cm, the height is 13.5 cm, and the mass is approximately 40 kg. The vessel is equipped with two propellers and two rudders, with a propeller diameter of 8 cm, and a rudder height of 8 cm. An anti-rolling device is also installed, as shown in Figure 8b. The USV is further equipped with an R-Fans 16-line mechanical LiDAR and a binocular camera. The R-Fans sensor provides a suitable balance between vertical resolution, detection range, and cost, which is especially important for near-field perception in berthing operations. Its 30° vertical field of view and 0.2° angular resolution enable reliable detection of quay walls and mooring structures at close range (within 50–80 m), which meets the requirements of typical berthing scenarios. The detailed parameters of the 3D LiDAR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

LiDAR data specifications.

3.1. Berthing Plane Fitting Experiment

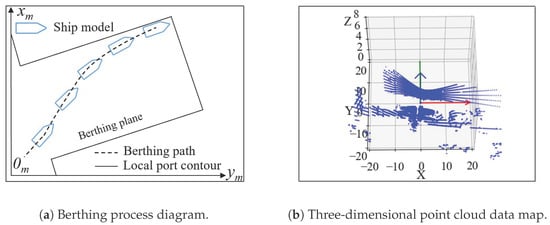

A berthing process diagram and a single-frame point cloud data map of the ship near the berth are shown in Figure 9. Nine frames of point cloud data from the berthing process were chosen for the berthing plane fitting experiment. The berthing plane was fitted using nine different plane fitting algorithms. The algorithms include RANSAC, M-estimator Sample Consensus (MSAC) [35], Maximum Likelihood Estimator Sample Consensus (MLESAC) [36], Progressive Sample Consensus (PROSAC) [37], Randomized Random Sample Consensus (RRANSAC) [38], Randomized M-estimator Sample Consensus (RMSAC) [34], LS, LMedS, and PCA.

Figure 9.

Berthing process diagram and point cloud data map.

For RANSAC, MSAC, MLESAC, PROSAC, RRANSAC, RMSAC, and LMedS, the distance threshold was set to 0.01, the maximum number of iterations was 100, and the other parameter settings were recommended by PCL. The fitting speed of RRANSAC and RMSAC is slow when the proportion of outliers is large. Therefore, the data is filtered before algorithm fitting; that is, the port berthing filters the point cloud of the ship’s right side, and the starboard berthing filters the point cloud of the ship’s left side to improve the fitting speed of the two algorithms.

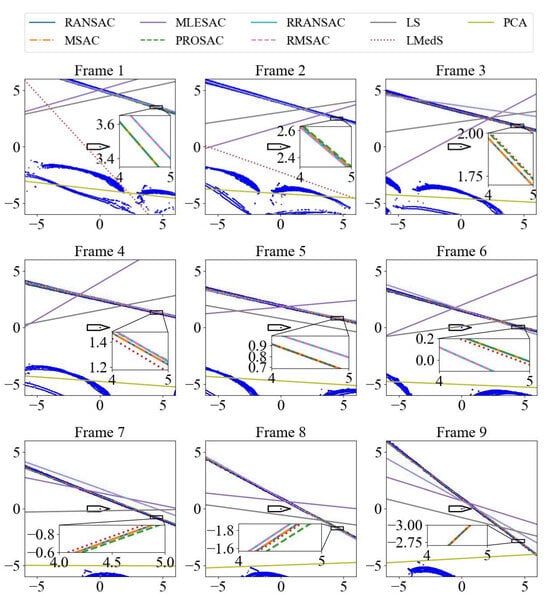

The results of each algorithm’s plane fitting are shown in Figure 10. The blue irregular points in the figure are the two-dimensional projection of the point cloud. The solid line and the dotted line are the intersection of the algorithm fitting plane and the z-value zero plane. It can be seen from the figure that the MLESAC, LS, and PCA fitting planes are quite different from the berthing plane. The fitting results of RRANSAC and RMSAC are better than the first three algorithms, but the fitting results of these two algorithms are not stable, and the fitting results of some frames are poor. The fitting results of the LMedS algorithm in the first two frames are poor, and the fitting plane in the last seven frames is similar to the berthing plane. The poor fitting in the first two frames is due to the fact that when the ship is far from the shore, the number of laser points in the berthing plane is smaller than when it is closer to the shore, and the proportion of noise points exceeds 50%, leading to reduced reliability for algorithm fitting. The fitting results of the algorithm are not reliable. The fitting results of RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC are good, and the fitting plane is close to the berthing plane.

Figure 10.

Each algorithm plane fitting 2D projection map.

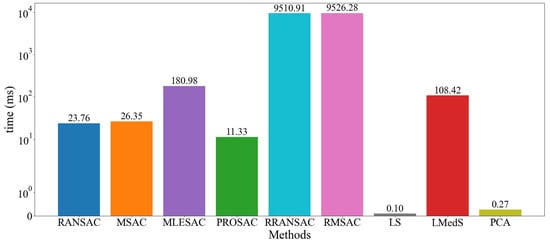

Figure 11 is a comparison of the average berthing plane fitting time (measured in milliseconds) for each algorithm employed. In ascending order, the algorithms are listed as follows: LS, PCA, PROSAC, RANSAC, MSAC, LMedS, MLESAC, RRANSAC, and RMASC. Notably, the plane fitting times for the initial five algorithms are all below the 100 ms threshold, thus demonstrating their suitability for real-time execution.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the average berthing plane fitting time for each algorithm.

In summary, the accuracy and speed of the MLESAC algorithm do not meet the requirements. The LS and PCA plane fitting speeds are fast, but the results are quite different from the real value. LMedS has high accuracy at close distances, but the long-distance fitting result is poor, and the fitting time is slow. RRANSAC and RMASC have accuracy and time bidirectional instability. RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC have higher fitting accuracy and faster speed.

3.2. Berthing State Estimation Experiment

RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC achieve higher fitting accuracy and faster speed on the berthing plane fitting experiment. To further test the state estimation accuracy of the three algorithms in the process of ship berthing, continuous frame experiments were carried out on the three algorithms. The continuous frame experiment is a plane fitting algorithm that is used to fit the berthing plane in real time and calculate the state of the ship relative to the berth during the whole berthing process.

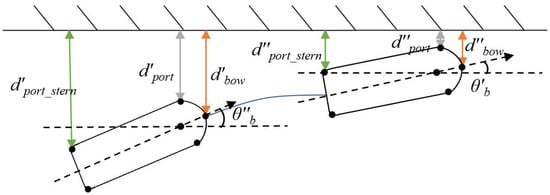

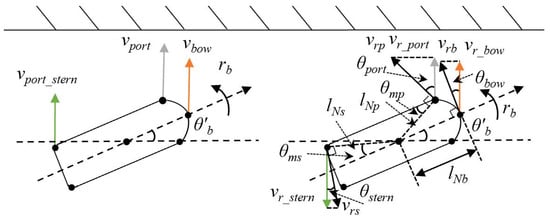

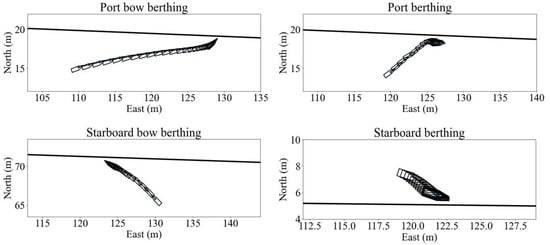

As shown in Figure 12, four different berthing experiments were designed to verify the performance of the algorithm: port bow berthing, port berthing, starboard bow berthing, and starboard berthing.

Figure 12.

Berthing experiment diagram.

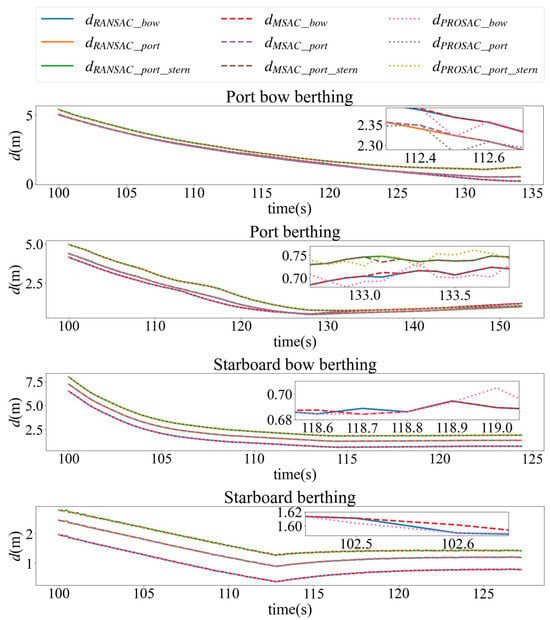

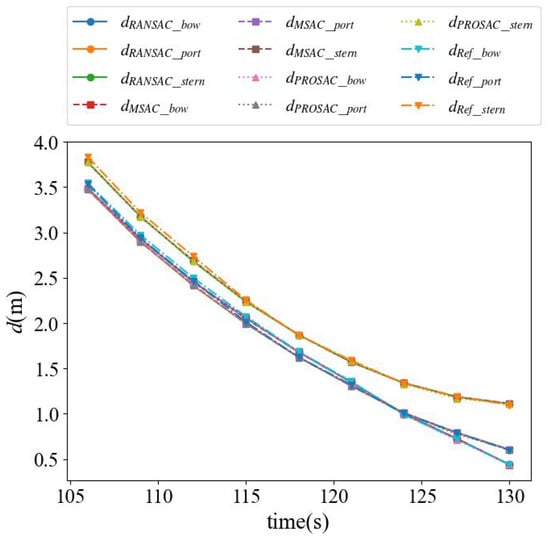

In the four berthing trials, the curve of the distance between the ship and the berth with time is shown in Figure 13, illustrating the composition of the berthing distance. For port side berthing, the distances are defined as those from the bow, port side, and port side stern to the berth, whereas for starboard side berthing, they are defined as the distances from the bow, starboard side, and starboard side stern to the berth. It can be observed that the berthing distance varies significantly during the initial stage and gradually becomes smoother thereafter. While the overall variation trends obtained by the three algorithms are largely consistent, the locally magnified view reveals discernible differences in detail. In the case of port side bow berthing, the final berthing distances are reduced in the order of port side stern, port side, and bow, which is consistent with the actual situation. The results obtained from the other three experimental groups also validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Figure 13.

The distance of the vessel relative to the berth.

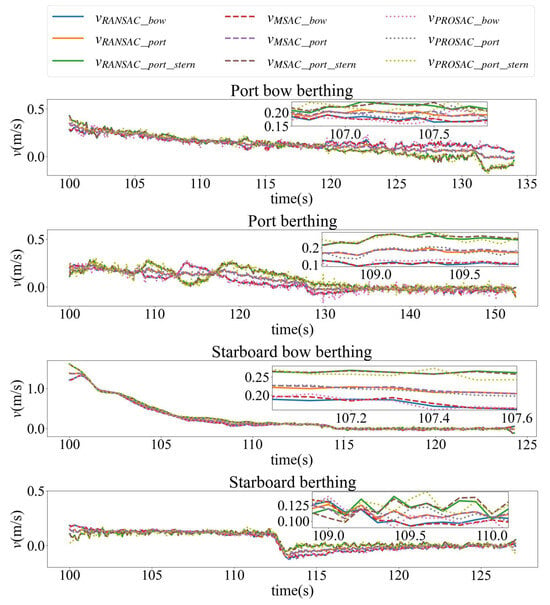

Figure 14 is the curve of the speed of the three algorithms with time during the berthing process, where , , and are the relative berth speed changes for the bow, port, and port stern obtained by the RANSAC plane fitting algorithm. The speed of the ship is relatively slow during berthing, and finally tends to 0 after a small increase and decrease.

Figure 14.

The velocity of the vessel relative to the berth.

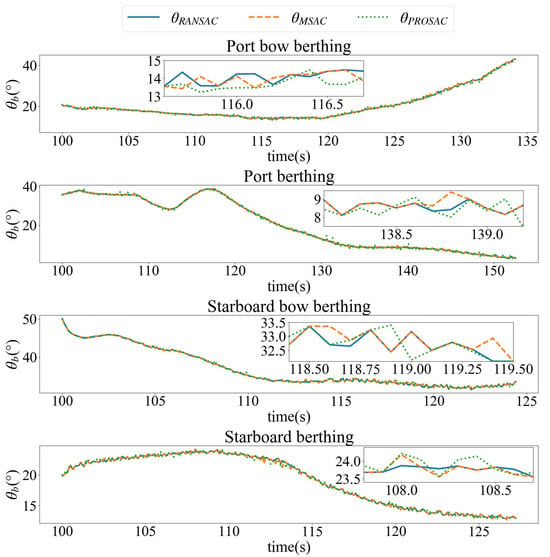

Figure 15 illustrates the variation of the ship’s approaching angle during the berthing process. The approaching angle ranges from 0° to 90°. In the case of port side bow berthing, the ship initially approaches the berth at a relatively small angle. During this process, the bow gradually rotates toward the berth, while the stern swings outward, until the entire vessel comes closer to the berth. In contrast, during starboard side bow berthing, the ship approaches the berth at a larger angle, and the approaching angle gradually decreases as the vessel aligns with the berth. Despite the differences in initial angles, both port side and starboard side berthing follow a similar pattern: the vessel approaches the berth at an angle, and as it nears the berth, it rotates until its longitudinal axis becomes nearly aligned with the berth. The curve shown in Figure 15 is consistent with this description, thereby validating the correctness of the proposed algorithm.

Figure 15.

Vessel-approaching angle to the berth.

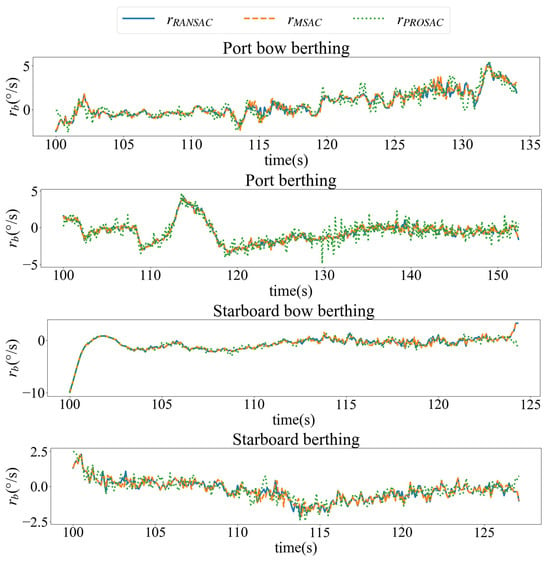

The variation in yaw rate during berthing is illustrated in Figure 16. For clarity, the curves are smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay filter with a window length of 15 and a polynomial fitting order of 3. In this context, a positive yaw rate indicates a rotation toward the berth, while a negative yaw rate corresponds to a rotation away from the berth. The fluctuations observed in the yaw rate curves are attributed to manual remote control of the unmanned boat during the berthing experiments, where local sharp changes in yaw rate are considered normal.

Figure 16.

Vessel angular velocity of yaw when berthing.

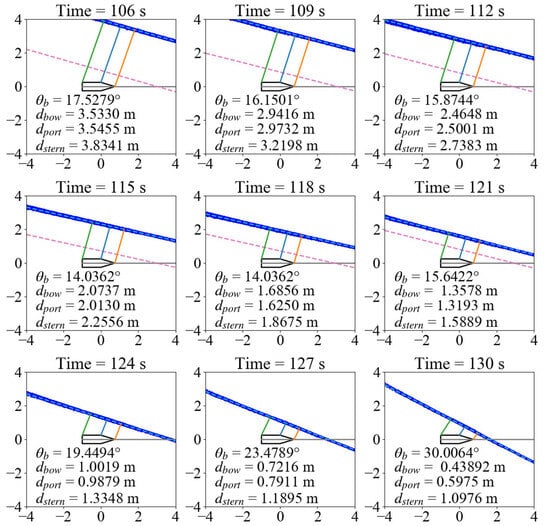

The above analysis verifies the feasibility of each algorithm. In order to further analyze the performance of each algorithm, nine frames of data during the bow berthing of the port side are selected at equal intervals. The two-dimensional image is shown in Figure 17, where the blue irregular points are the two-dimensional projection of the point cloud, and the light blue dotted line is the artificial fitting line as the reference value of the berthing plane. Specifically, quay boundary points were manually identified from the LiDAR point clouds by two independent operators with experience in marine data interpretation. A least-squares linear regression was subsequently applied to these boundary points to construct a reference berthing plane, hereafter referred to as the artificially fitted line. This reference line was employed to compute the berthing distance and approach angle for ground truth generation. To ensure the reliability of the annotated reference data, cross-validation was performed by comparing the independent annotations of the two operators, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. To facilitate the observation of the approaching angle, the fitted line was translated, as indicated by the light pink dashed line in the figure. The angle and distance values in the diagram are the ground truth values of the state estimation, which are the angle between the ship’s center line and the fitted straight line and the distance from the bow, port, and port stern to the fitted straight line. Figure 18 is the image data of the UAV’s perspective during the berthing process, corresponding to Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Top view of vessel point cloud at the end of the berthing stage. The light blue dashed line represents the manually fitted berth line, the light pink dashed line is the shifted fitted line for clarity, and the orange, blue, and green solid lines indicate the berthing distances of the bow, port side, and stern, respectively.

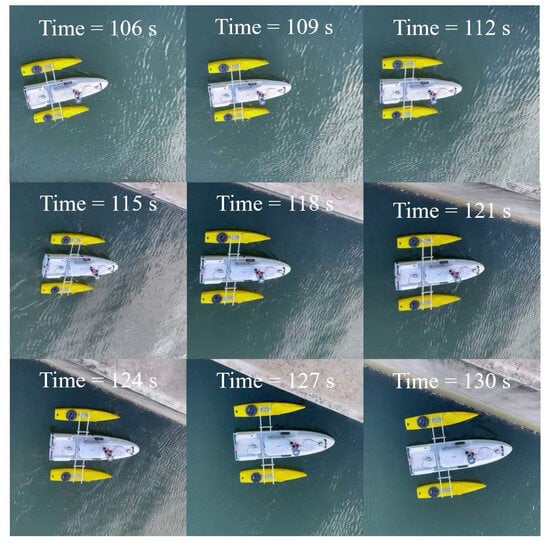

Figure 18.

Top view of vessel images at the end of the berthing stage.

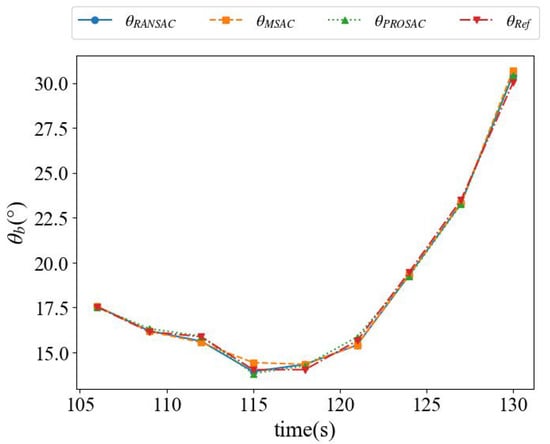

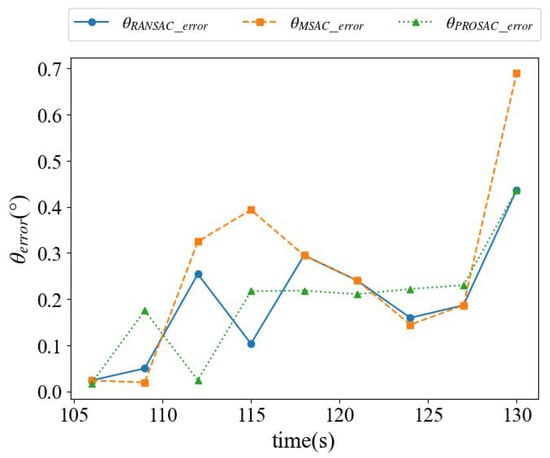

Figure 19 and Figure 20 illustrate the temporal variations of the vessel approaching angle and the associated errors from 106 s to 130 s. The curves in Figure 20 represent the absolute errors, calculated as the modulus of the difference between the estimated approaching angle and the reference value. Analysis shows that the approaching angles obtained by the RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC algorithms closely follow the reference values. The absolute errors range from 0° to 0.7°. Specifically, for the berthing angle, the RANSAC algorithm exhibits a maximum error of 0.4368° and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.1944°; the MSAC algorithm shows a maximum error of 0.6905° and a MAE of 0.2576°; and the PROSAC algorithm reaches a maximum error of 0.4368° and a MAE of 0.1947°. The errors of RANSAC and PROSAC are comparable, while MSAC shows slightly larger deviations.

Figure 19.

Variation process of vessel-approaching angle.

Figure 20.

Variation process of vessel approaching angle error.

To assess potential bias, the algebraic errors (signed differences) were also examined. The distribution of these signed errors indicates that the estimators do not exhibit significant systematic bias, as positive and negative deviations are roughly balanced over time.

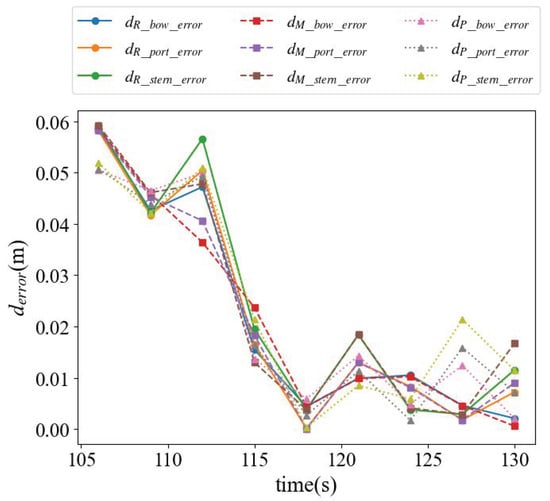

Figure 21 and Figure 22 present the berthing distances and their corresponding absolute errors, including distances from the bow, port midsection, and port stern to the berthing plane. The absolute errors, again, are defined as the modulus of the algebraic errors and range from 0 to 0.06 m. The maximum errors for RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC are 0.0592 m, 0.0592 m, and 0.0519 m, respectively, while the MAEs are 0.0226 m, 0.0222 m, and 0.0227 m. Analysis of the algebraic errors confirms that the berthing distance estimates are unbiased.

Figure 21.

Berthing distance change process.

Figure 22.

Berthing distance error change process.

Comparing the absolute error of the approaching angle with that of the berthing distance, we observe relatively stable results obtained by the algorithms. When compared with the results of the manual fitting reference value and the 3D LiDAR algorithm, it is evident that 3D LiDAR can be effectively employed for calculating both the berthing distance and angle. Consequently, the proposed 3D LiDAR berthing state estimation scheme outlined in this paper is deemed accurate and reasonable.

4. Discussion

4.1. Accuracy and Real-Time Performance of Algorithm

This paper presents a comprehensive investigation of nine algorithms, testing their performance in terms of accuracy and real-time performance. An examination of Figure 11 reveals that the algorithms RANSAC, MSAC, PROSAC, LS, and PCA exhibit real-time performance. Additionally, the data illustrated in Figure 10 highlights the superior accuracy of RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC. To gain further insights, we conducted a detailed analysis of the berthing state estimation experiment, focusing specifically on the RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC algorithms. The experimental outcomes validate the precision of the estimated parameters, such as berthing distance, approaching angle, berthing speed, and yaw rate, as they align closely with the actual values. In the process of evaluating the results, it is noteworthy that the three algorithms demonstrate an average angle error of less than 0.3°, a distance error of fewer than 0.03 m, and a remarkably high level of state estimation accuracy.

4.2. Limitations and Improvement of the Plane Fitting Algorithm

Based on the aforementioned analysis, it becomes evident that RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC have exhibited commendable performance in terms of both accuracy and speed among the nine algorithms considered. Conversely, the remaining six algorithms have demonstrated subpar performance. Although LS and PCA yielded unsatisfactory results in terms of plane fitting, their computational efficiency is noteworthy, with a processing time of less than 1 ms per frame. These algorithms may be a preferable choice for systems with limited computational resources or scenarios that demand real-time processing. Further analysis and refinement of these two algorithms would prove advantageous. Experimental observations have indicated that the reliability of the LMedS algorithm diminishes when the noise level exceeds 50%. Hence, it can be improved by filtering out the point cloud on the opposite side of the berthing plane. This improvement can also improve the speed of the algorithm. The three algorithms of MLESAC, RRANSAC, and RMSAC are suitable for dealing with a situation where the proportion of local points in the data points is large. The reason why the three algorithms have poor results in the experiment is that the proportion of local points is small. The three algorithms can also be improved by filtering algorithms.

4.3. Limitations and Improvement of Berthing State Estimation Based on Plane Fitting

This paper introduces a novel ASV berthing state estimation scheme based on plane fitting, substantiated by the reliability and accuracy demonstrated through real ship experiments. However, the scheme may exhibit some limitations. Specifically, when the LiDAR’s height exceeds the height of the port by a significant amount, resulting in an increased scan of laser points above the port plane, more laser points are projected to the plane above the port, and fewer laser points are projected to the berthing plane. At this time, the fitting plane of the algorithm may be the ground above the port, not the berthing plane. To address this issue, the water surface height relative to the ground above the port is estimated using tidal data during berthing. Points above the estimated berthing plane are filtered out, followed by execution of the plane fitting algorithm. Additionally, alternative strategies can be employed: (1) sensor fusion with barometric altimetry to dynamically estimate water surface height; (2) adaptive plane fitting that accounts for variations in point cloud distribution and water level; and (3) linear fitting of the intersection between the port plane and the ground plane, representing the shoreline. These approaches offer practical guidance for implementation and enhance the reliability and completeness of ASV berthing state estimation in future applications.

5. Conclusions

This paper mainly investigates ship berthing state estimation based on 3D LiDAR and proposes a berthing state estimation algorithm based on plane fitting. Firstly, nine common plane fitting algorithms were implemented, including RANSAC, MSAC, MLESAC, PROSAC, RRANSAC, RMSAC, LS, LMedS, and PCA. These algorithms were used to fit the berthing plane, and their performance was evaluated in terms of both accuracy and computational speed. Secondly, a ship berthing state estimation framework based on plane fitting was built, which can output berthing distance, berthing speed, approaching angle, and yaw rate information in real time. Finally, the algorithm was validated through a small unmanned ship berthing experiment.

The plane fitting results indicate that RANSAC, MSAC, and PROSAC achieve the highest accuracy with fast fitting speed. The average berthing angle error of the proposed algorithm is below 0.26°, and the average berthing distance error is below 0.023 m, consistent with the results reported in the abstract. This demonstrates that the proposed berthing state estimation algorithm achieves high accuracy (centimeter level) and can output real-time information at a 10 Hz frequency, fulfilling both accuracy and real-time requirements.

Although the algorithm provides highly accurate berthing state information, some limitations remain. For example, when the ship is large or during high tide, the plane fitting algorithm may struggle to accurately fit the berthing plane. Improving the robustness and stability of the algorithm is the focus of future work.

Author Contributions

H.W.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Y.Y.: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Q.J.: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Resources, Software, Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition. C.-L.Z.: Resources, Software, Investigation, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52071049; National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4300803, 2022YFB4301402); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 3132023139, and the 2022 Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Plan (Key) Project: R&D and Application of Autonomous Navigation System for Smart Ships in Complex Waters, grant number 2022JH1/10800096.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and security restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

The following vessel berthing parameters are used in this manuscript:

| Berthing distance | |

| The distance from the ship’s bow to the berth | |

| The distance from the ship’s LiDAR to the berth | |

| The distance from the ship’s port side to the berth | |

| Approaching angle | |

| Berthing velocity | |

| The velocity of the bow relative to the berth | |

| The velocity of the port side relative to the berth | |

| Yaw rate | |

| The absolute error of the berthing distance | |

| The reference value of the berthing distance | |

| The distance from the ship’s bow to the berth obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The distance from the ship’s port side to the berth obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The distance from the ship’s port side stern to the berth obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The absolute error of the berthing distance obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The absolute error of the bow berthing distance obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The absolute error of the stern berthing distance obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The velocity from the ship’s bow to the berth obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The absolute error of the approaching angle | |

| The reference value of the approaching angle | |

| The approaching angle obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The absolute error of the approaching angle obtained by the RANSAC algorithm | |

| The Yaw rate obtained by the RANSAC algorithm |

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASV | Autonomous surface vessel |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| DGPS | differential global positioning system |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Units |

| PCL | Point cloud library |

| RANSAC | Random Sample Consensus |

| LS | Least Squares |

| LMedS | Least Median of Squares |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| EVD | Eigenvalue decomposition |

| NDT | Normal distribution transformation |

| MSAC | M-estimator Sample Consensus |

| MLESAC | Maximum Likelihood Estimator Sample Consensus |

| PROSAC | Progressive Sample Consensus |

| RRANSAC | Randomized Random Sample Consensus |

| RMSAC | Randomized M-estimator Sample Consensus |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

References

- Guedes Soares, C.; Teixeira, A.; Antão, P. Accounting for human factors in the analysis of maritime accidents. Foresight Precaut. 2000, 1, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), 98th Session. 2017. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/meetingsummaries/pages/msc-98th-session.aspx (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Zhu, M.; Sun, W.; Hahn, A.; Wen, Y.; Xiao, C.; Tao, W. Adaptive modeling of maritime autonomous surface ships with uncertainty using a weighted LS-SVR robust to outliers. Ocean Eng. 2020, 200, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; An, L.; Yang, R. Collision-avoidance navigation systems for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: A state of the art survey. Ocean Eng. 2021, 235, 109380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubowicz, T.; Armiński, K.; Witkowska, A.; Śmierzchalski, R. Marine autonomous surface ship-control system configuration. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Z.; Guo, C.; Sun, S. Research into the automatic berthing of underactuated unmanned ships under wind loads based on experiment and numerical analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Li, G.; Cheng, X.; Skulstad, R.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H. An efficient neural-network based approach to automatic ship docking. Ocean Eng. 2019, 191, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokukcu, M.; Sakar, C. Risk analysis of collision accidents during underway STS berthing maneuver through integrating fault tree analysis (FTA) into Bayesian network (BN). Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 126, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.k.; Im, N.k. Ship nonlinear-feedback course keeping algorithm based on MMG model driven by bipolar sigmoid function for berthing. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2017, 9, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Jia, Q.; Li, Y. Layered berthing method and experiment of unmanned surface vehicle based on multiple constraints analysis. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 86, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Marais, J.; Bétaille, D.; Berbineau, M. GNSS position integrity in urban environments: A review of literature. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 2762–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouybari, A.; Amiri, H.; Ardalan, A.A.; Zahraee, N.K. Methods comparison for attitude determination of a lightweight buoy by raw data of IMU. Measurement 2019, 135, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, S.; Kubo, M. Ship berthing and mooring monitoring system by pneumatic-type fenders. Ocean Eng. 2007, 34, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Choi, Y.W.; Kim, Y.B. Implementation of Tracking-Learning-Detection for improving of a Stereo-Camera-based marker-less distance measurement system for vessel berthing. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th IEEE International Colloquium on Signal Processing & Its Applications (CSPA), Langkawi, Malaysia, 28–29 February 2020; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Park, B.; Lee, S.M. Artificial intelligence vision-based monitoring system for ship berthing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 227014–227023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yu, J.; Tu, Y.; Pan, L.; Zhu, Q.; Mou, J. Research on data driven adaptive berthing method and technology. Ocean Eng. 2021, 222, 108620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dai, B.; Wu, T. Vision-based precision vehicle localization in urban environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 Chinese Automation Congress, Changsha, China, 7–8 November 2013; pp. 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Vivet, D.; Gérossier, F.; Checchin, P.; Trassoudaine, L.; Chapuis, R. Mobile ground-based radar sensor for localization and mapping: An evaluation of two approaches. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Borno, M.; O’Day, J.; Ibarra, V.; Dunne, J.; Seth, A.; Habib, A.; Ong, C.; Hicks, J.; Uhlrich, S.; Delp, S. OpenSense: An open-source toolbox for inertial-measurement-unit-based measurement of lower extremity kinematics over long durations. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, T.; Wang, S. A manoeuvre indicator and ensemble learning-based risky driver recognition approach for highway merging areas. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2024, 6, tdae015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhu, H.; Yang, L. Berthing support system using laser and marine hydrometeorological sensors. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 3rd Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC), Chongqing, China, 3–5 October 2017; pp. 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Perkovic, M.; Gucma, M.; Luin, B.; Gucma, L.; Brcko, T. Accommodating larger container vessels using an integrated laser system for approach and berthing. Microprocess Microsyst. 2017, 52, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, Y. Motion pose estimation of inshore ships based on point cloud. Measurement 2022, 205, 112189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.; Silva, R.; Matos, A.; Pinto, A.M. An hierarchical architecture for docking autonomous surface vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International conference on autonomous robot systems and competitions (ICARSC), Porto, Portugal, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, A.B.; Bitar, G.; Lekkas, A.M.; Gros, S. Optimization-based automatic docking and berthing of ASVs using exteroceptive sensors: Theory and experiments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 204974–204986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Estimation of ship berthing parameters based on Multi-LiDAR and MMW radar data fusion. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, X.; Jing, Q.; Lyu, H.; Yin, Y. Estimation of berthing state of maritime autonomous surface ships based on 3D LiDAR. Ocean Eng. 2022, 251, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Han, B.; Liu, W.; Montewka, J.; Liu, R.W. Orientation-aware ship detection via a rotation feature decoupling supported deep learning approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, H.; DeRose, T.; Duchamp, T.; McDonald, J.; Stuetzle, W. Surface reconstruction from unorganized points. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–31 July 1992; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shakarji, C.M. Least-squares fitting algorithms of the NIST algorithm testing system. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 1998, 103, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Least median of squares regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1984, 79, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. London, Edinburgh, Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.; Wahl, R.; Klein, R. Efficient RANSAC for point-cloud shape detection. Comput. Graph. Forum 2007, 26, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torr, P.; Zisserman, A. Robust computation and parametrization of multiple view relations. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Computer Vision (IEEE Cat. No. 98CH36271), Bombay, India, 7 January 1998; pp. 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Torr, P.H.; Zisserman, A. MLESAC: A new robust estimator with application to estimating image geometry. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2000, 78, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, O.; Matas, J. Matching with PROSAC-progressive sample consensus. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Matas, J.; Chum, O. Randomized RANSAC with Td, d test. Image Vis. Comput. 2004, 22, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).