Abstract

Conducting a safety simulation assessment of gas release from the vent mast during the design stage holds significant importance for ship design and system operation safety on LNG-powered vessels. Based on a large-scale practical LNG-powered vessel, this paper employs the CFD method to carry out a safety assessment of the natural gas dispersion, and proposes an optimization design method to address the issue where the vent mast height of large-scale LNG-powered vessels fails to meet specifications. The influencing factors of gas dispersion are discussed. The simulation results indicate that the vent mast height, wind direction, and wind velocity significantly affect the gas dispersion behavior. A lower vent mast height results in a greater risk of flammable gas clouds accumulating on the deck surface. Hazards analysis of the 6 m vent mast condition with windless suggests that a cryogenic explosion hazard zone is formed on the deck centered around the mast position, with the maximum gas concentration reaching 30% and the minimum temperature below −55 °C. The gas cloud spreads along the wind direction, and the extension distance is positively correlated with wind speed. With the increase in wind velocity, the height and volume of flammable gas clouds decrease. When the wind speed is 15 m/s, the volume of the flammable gas cloud is less than half of that at 5 m/s and less than one-tenth of that at 0 m/s. Higher wind velocity can notably promote gas diffusion.

1. Introduction

The escalating global energy consumption and the carbon reduction requirements emphasize the imperative of renewable alternative energy sources [1]. With the annual increase of carbon emissions in the marine industry, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) [2] issued a strategy to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from ships in 2023, and proposed the standards for carbon emissions and taxation in 2025. In addition, the IMO has been stipulating increasingly stringent requirements on the pollutant emissions from ships, including SOx [3]. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is regarded as a clean energy with high calorific value and high combustion efficiency [4]. Carbon emissions of LNG fuel are at least 20 percent lower than those of petroleum fuels, while LNG fuel exhibits nearly negligible sulfide emissions [5]. Due to complete regulations and well-developed infrastructure, the number of LNG-powered vessels is increasing, constituting one-third of the new build orders [6,7,8]. However, LNG exhibits a flammable and explosive characteristic, resulting in frequent explosion-related injuries with personal casualties and economic losses [9]. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct a safety assessment of the gas dispersion on LNG-powered ships, preferably during the design phase.

Since the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation method can be adopted to analyze accident hazards under complex conditions [10,11,12,13,14,15], it is utilized to conduct the safety analysis of gas leakage and dispersion on LNG-powered vessels. Liu [16] studied the leakage and diffusion of LNG storage tanks on a container ship under extremely adverse conditions through the CFD model, calculated the safe zone, and provided safety management recommendations. Nubli [17] applied CFD to evaluate the cryogenic hazards of LNG leakage during LNG bunkering, while Wang [18] carried out the safety analysis of the fuel gas preparation hold of an LNG-powered vessel during LNG leakage. Duong [19] analyzed the vapor cloud diffusion of marine fuels, such as LNG or liquid ammonia, when they accidentally leaked from the hose, thereby establishing a safety zone during the bunkering. Zhang [20] adopted a two-phase model to simulate the dispersion process of natural gas clouds, and analyzed the influence of relative humidity on the gas dispersion. Full-scale CFD simulations were conducted, and the results indicated that heat transfer and turbulence affect combustible clouds [21]. With the development trend of large-scale LNG-powered ships, the design of vent masts often fails to meet the specification requirements and needs to be optimized. However, there are few studies on the optimization of the design of the vent mast height on LNG-powered ships, which is a key design parameter and crucial for the system operation and vessel safety.

On the basis of the practical design of a large-scale LNG-powered vessel, this article conducts a safety analysis of gas dispersion during release from the vent mast using the CFD method, and proposes an optimization design method to address the problem where the height of the vent mast on the large LNG-powered vessel fails to meet the specifications. This method takes into account the actual specifications and constraints for the large-scale LNG-powered ship design, providing a solution that can be approved by the competent authorities. The influencing factors of gas dispersion from the vent mast are discussed. Safety simulation assessments of gas dispersion from the vent mast under varying mast heights, wind directions, and wind speeds are evaluated, which is of great significance for ship design, system operation, and crew safety.

2. Principle

2.1. Relevant Regulation Analysis

The International Safety Code for Ships Using Gas or Other Low Flash Point Fuels (IGF Code), adopted by the IMO, has established safety standards for ships operating with gas or low-flashpoint liquids as fuel, among which LNG is the most commonly used fuel. The vent mast is a vertically upward tubular structure on LNG-powered vessels, discharging natural gas (NG) into the atmosphere from the LNG storage, all pipes, and processing equipment.

The IGF Code delineates the requirements regarding the arrangement and height of the vent mast. The height of the mast shall be at least 6 m or B/3 (where B represents the beam of the ship), whichever is the greater value. It can be speculated that the vent mast height has an impact on the safety of gas release from the vent mast. In light of the height limitations in the sea areas, particularly for large-scale LNG-powered vessels, it is arduous to fulfill the requirements of the IGF code regarding the height of the vent mast. The specification allows for the optimization of the design of the vent mast through equivalent proof methods. With the authorization of the competent authorities, the vent mast height can be reduced by conducting a safety simulation analysis of the gas dispersion from the vent mast. Therefore, a method for optimizing and alternative designs of the vent mast height is researched in this paper, and the influencing factors of gas release from the vent mast are explored. Additionally, the IGF code delineates that the vent mast shall be situated at least 10 m from air intake, air outlet, opening, service spaces, and control stations. Further analysis reveals that the scenario of safety simulation analysis of vent mast gas release should consider its impact on the above-mentioned sensitive areas.

The safety assessment of gas dispersion necessitates corresponding indicators. As per ISO18683 [22], “Guidelines for Safety and risk assessment of LNG fuel bunkering operations”, the safe distance of gas diffusion is contingent upon the influence scope of the lower flammable limit (LFL). Consequently, we evaluate the risk of gas release from the vent mast by considering the scope of LFL. To further guarantee the reliability of safety simulation analysis, regions where the gas concentration is below half of the lower flammable limit, namely 50%LFL, are considered as safe zones, devoid of the combustion and explosion risk [23]. In conclusion, the potential hazards of gas dispersion from the vent mast in LNG-powered vessels are evaluated based on the distribution range of the flammable gas cloud with a gas concentration greater than 50%LFL (i.e., 2.5% volume concentration) in this article.

2.2. Methodology and Model

The NG dispersion safety simulation performs the continuity equation, momentum equation, energy equation, and transport equation, ignoring the heat transmission and alteration of atmospheric pressure, structure, and fluid itself. The fluid satisfies continuity Equation (1), momentum (Navier–Stokes) Equation (2), and energy Equation (3):

where u denotes the eulerian velocity, measured in m/s, while p signifies the pressure, measured in Pa; stands for the density, kg/m3, and denotes the kinetic viscosity, Pa·s; x represents the direction, measured in m; e represents internal energy, J; K is the thermal conductivity, W/(m·K); J is the diffusion flux, s·m2; S is chemical reaction heat, J; while h is the enthalpy, J.

The standard k-ε and k-ω turbulence models are typically utilized to solve the complex turbulent flow problem in various engineering scenarios [24,25]. In this study, the shear stress transport (SST) turbulence model is employed for more precise calculation, which adopts the k-ε turbulence model in the main flow field and the k-ω turbulence model in the boundary layer. The k-ω turbulence model, which is extensively employed in industrial CFD analysis for handling the turbulent boundary layer, demonstrates higher accuracy in analyzing the boundary layer with a steep velocity gradient than the k-ε turbulence model [26]. Additionally, the k-ω turbulence model applies a scalable wall function, in contrast to the standard wall function used in the k-ε turbulence model. Furthermore, in the pursuit of more precise analysis, a greater number of mesh elements were generated in the boundary layer adjacent to the wall.

2.3. Calculation of Gas Release Flow

When accidents, such as fires or system failures, occur on the LNG-powered vessel, the pressure of the LNG storage tank may abnormally increase. When the pressure of the LNG tank exceeds the maximum pressure limited by the safety valve on the LNG storage tank, the safety valve automatically opens to release the boil-off gas (BOG) inside the tank, thereby providing protection for systems and preventing more serious accidents. When the safety valve opens automatically, the BOG in the tank is directly discharged into the venting system, eventually reaching the vent mast for release into the atmosphere. The primary sources of gas release from the vent mast include ventilation of the LNG storage tank, high-pressure buffer tank, low-pressure buffer tank, BOG compressor system, and refueling station. Among these gas release sources, only the LNG storage tank features a large storage capacity, a substantial venting volume, and a long venting duration, while the other facilities have a short venting time and a small venting volume. Consequently, the boundary condition calculation for the gas release from the vent mast mainly takes into account the safety valve tripping release during over-pressurization of the LNG storage tank.

Based on the IGF specification, the release flow of the LNG storage tank safety valve under emergency release conditions, such as fire exposure, is calculated as follows [27]:

where Q represents the release rate at standard conditions of 273 K and 0.1013 MPa, m3/s; F is the fire exposure coefficient applicable to different types of storage tank layout, as follows:

For non-insulated storage tanks located on the deck, the value of F is 1.0;

For storage tanks above the deck with an insulation layer approved by the classification, the value of F is 0.5;

For uninsulated independent storage tanks inside the cabin, the value of F is 0.5;

For insulated independent storage tanks inside the cabin, the value of F is 0.2;

For inert gas-protected, insulated independent storage tanks inside the cabin, the value of F is 0.1.

G is the gas influencing factor, which is determined by the physical properties of the gas. A represents the external area of the storage tank, m2.

3. Simulation Method

3.1. 3d Modeling Establishment

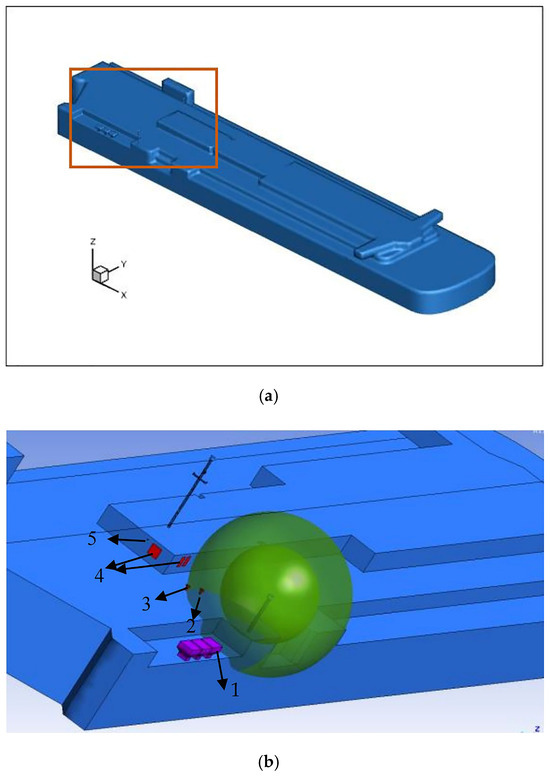

A large-scale LNG-powered ship is selected as the research object, whose dimension parameters are displayed in Table 1. The layout of complex equipment and structure on the deck of the vessel exerts a notable influence on the dispersion behavior of natural gas. Consequently, it is essential to conduct three-dimensional (3D) modeling of devices on deck for numerical analysis. Drawing on the actual design of the large LNG-powered vessel, a 3D model of the vessel was constructed in accordance with physical dimensions based on the general layout plan (Figure 1a). In the course of the modeling process, precedence was accorded to the structure that might affect gas dispersion behavior, including large-scale buildings and residential areas. The small-scale equipment and detailed structure, which impose a substantial computational load yet exert a negligible influence on dispersion phenomena, were streamlined and omitted from the modeling. Concurrently, the sensitive areas near the vent mast should be given priority consideration and modeled in detail, as mentioned in Section 2.1, including air intakes, air outlets, openings, service spaces, and control stations.

Table 1.

Dimension parameters of the LNG-powered vessel.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a 3D model of the LNG-powered vessel. (a) Complete model of the entire ship. (b) Details of the sensitive area near the vent mast are in the box of (a). (1—Fan room; 2—Exhaust vent of the ladder way; 3—Air intake of the ladder way; 4—Emergency power generator room ventilation louver; 5—Exhaust pipe of the Emergency power generator room).

Figure 1b shows the modeling of sensitive areas near the vent mast. In Figure 1b, the 10 m radius area centered on the vent mast outlet is represented by the green sphere, while the air intake and exhaust vent of the ladder way, and one fan room are situated within the hazardous area. Furthermore, for safety considerations, the project also encompasses the exhaust pipe and ventilation louvers of the emergency generator room (12–14 m away from the vent mast outlet). The calculation domain of vent mast gas dispersion analysis ought to incorporate both the vessel and the surrounding wind field environment.

3.2. Grid Generation

The number of grid cells for the calculation domain is 3,405,368. The locally encrypting the mesh method is adopted, which improves the calculation accuracy but increases the number of grids slightly [28]. Grid encryption is applied to the boundaries of the calculation domain, the sensitive area, and the periphery of the vent mast outlet. The grid division and simulation solution are implemented using the software StarCCM+ 13.3 To balance the consumed time and accuracy of the computation [29], we conducted a grid independence analysis, and the results are shown in Table 2. When the number of grid cells reaches 3,405,368, the mesh meets the calculation accuracy requirements.

Table 2.

The grid independence analysis results.

3.3. Simulation Scenario and Boundary Conditions

This article explores the influencing factors on the gas dispersion behavior from the vent mast, considering the vent mast height, wind direction, and wind velocity.

- (1)

- Vent mast height. As described in Section 2.1, the vent mast height has an impact on the safety of gas release from the vent mast. In line with the IGF code, the height of the mast should be at least 6 m or one—third of the ship beam, whichever is the greater value. This study conducts a comparison of the gas release risk from the vent mast with two designed heights, namely 6 m and 15 m (one-third of the ship beam). Meanwhile, an optimized design of the vent mast height is implemented to determine the minimum height that satisfies the safety requirements.

- (2)

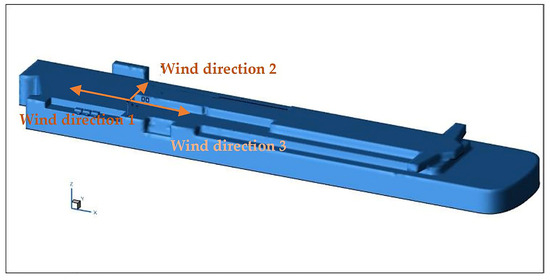

- Wind direction. As depicted in Figure 2, various wind directions are considered to evaluate the influence of gas release from the vent mast on the surrounding sensitive areas. Specifically, we considered the wind blowing towards the stern direction (wind direction 1), port-side direction (wind direction 2), and bow direction (wind direction 3), respectively.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the simulation wind direction.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the simulation wind direction. - (3)

- Wind velocity. In this project, the vessel navigation velocity under the navigation condition is 14.5 knots, and the wind velocity during simulation is the synthesized wind velocity derived from fitting the navigation velocity and ambient wind velocity. Four wind velocities were selected for the gas dispersion simulation: 0 m/s, 5 m/s, 10 m/s, and 15 m/s.

The boundary conditions of the simulation analysis are listed in Table 3. The simulation calculation process is considered to be a transient state using the SST model. The gas release flow rate is calculated as the release flow of the safety valve on the LNG storage tank, according to Equation (4). The design pressure of the LNG fuel tank is 4 barg. The safety valve opens to discharge natural gas when the pressure within the LNG tank reaches the design pressure, and closes when the pressure attains the reseating pressure of the safety valve, 90 percent of the design pressure. The gas release duration was determined by the time interval from the opening to the reseating of the safety valve. This article discusses the most severe operating conditions, where the BOG content in the LNG storage tank is the highest and the time for the safety valve to reseat is the longest. At this time, the gas release time is 15 s. Considering the impact of gravity on gas diffusion, the gravitational acceleration along the z direction is set to—9.81 m/s2. The natural gas is simulated as a mixture by adopting the component transportation model, and the composition and volume fraction are set according to the actual ship project fuel, listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Boundary conditions for the simulation analysis.

Table 4.

Parameters of natural gas composition and volume fraction for the simulation analysis.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Vent Mast Height

4.1.1. Vent Mast Height of 6 m and B/3

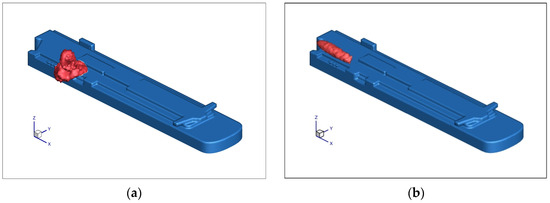

The literature [30] indicates that the gas deposition behavior is associated with relative wind speed. A higher wind velocity leads to a more rapid cryogenic gas dispersion and weaker accumulation and deposition phenomena. This section examines the influence of the vent mast height on gas dispersion behavior and the associated hazards with an inadequate height of the vent mast. Consequently, this section primarily focuses on the gas release from the vent mast under the windless condition with a wind speed of 0 m/s during the ship mooring, which represents the working condition most prone to gas deposition. When the height of the vent mast is 6 m and 15 m, the simulation results of the flammable gas cloud are displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

Figure 3.

Flammable gas cloud (concentration greater than 50%LFL) diagram of natural gas dispersion from a 6 m vent mast at different wind speeds. (a) Wind speed of 0 m/s. (b) Wind speed of 10 m/s.

Figure 4.

Gas cloud (concentration greater than 50%LFL) diagram of natural gas dispersion from a 15 m vent mast at different wind speeds. (a) Wind speed of 0 m/s. (b) Wind speed of 10 m/s.

As depicted in Figure 4, when the height of the vent mast reaches 15 m (B/3), the flammable gas cloud does not spread to the deck, ensuring that the deck area remains within the safety range. Nevertheless, with a height of 6 m in Figure 3, the flammable gas cloud accumulates on the deck surface. At this height, the working area for the crew and the sensitive areas around the fan and air outlets are within the gas explosion range, presenting substantial risks. Therefore, the vent mast height has a significant impact on the gas dispersion behavior. A greater height of the vent mast leads to a more favorable upward diffusion trend of the natural gas and a lower risk of gas sedimentation on the deck. When the height is inadequate, there exists a tendency for the flammable gas to deposit on the deck, posing a substantial risk. When the height of the vent mast is relatively high, the flammable gas has not deposited in the vicinity of the deck and remains unaffected by the layout on the deck until the gas release concludes. After the gas release from the vent mast ceases, the gas mass undergoes heating in the atmosphere, causing it to exhibit an upward movement tendency.

Furthermore, comparative analysis was conducted on simulation results obtained under a wind velocity of 10 m/s (wind direction 3) in Figure 3b and Figure 4b. At this wind velocity, the flammable gas cloud from the 6 m-high vent mast exhibits no observable descent to the deck, thereby providing empirical validation for the above-mentioned hypothesis. Maximum gas deposition propensity was observed under the windless condition with a wind speed of 0 m/s.

4.1.2. Gas Dispersion Hazards from 6-m High Vent Mast

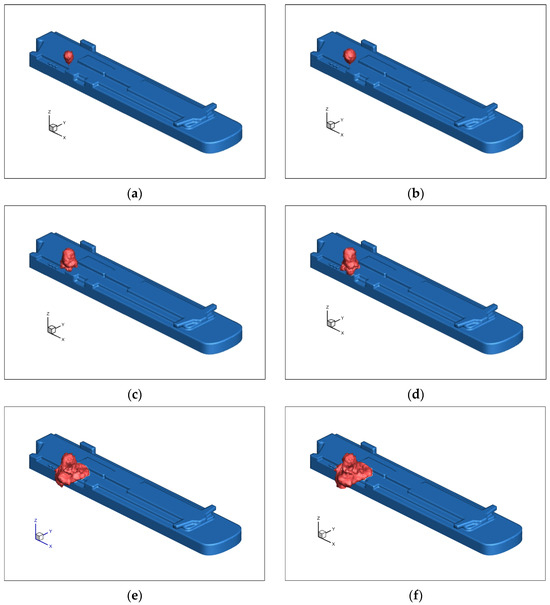

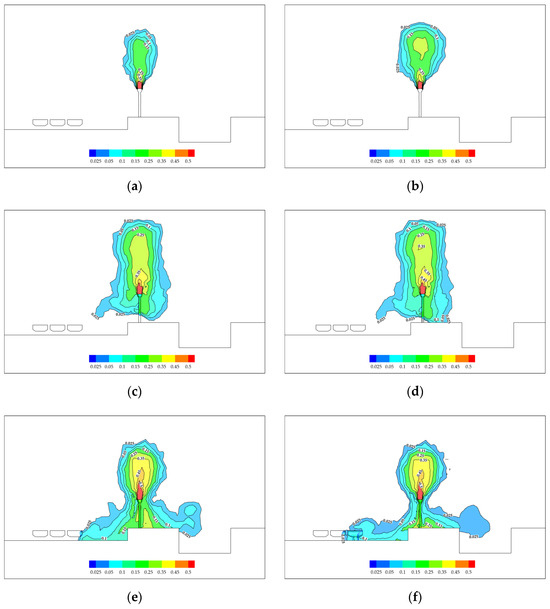

Previously, an investigation was conducted on the gas dispersion hazard from the vent mast on the LNG-powered vessel, and this section further expands upon the previous work [31]. Figure 5 depicts the temporal variations in the flammable gas cloud. As presented in the figure, at the beginning of gas release, the flammable gas cloud rises and expands rapidly, dispersing outward from the outlet of the vent mast. It can be observed that with the increase in gas release duration, the volume of the flammable gas cloud gradually expands. At 9 s, owing to the effect of gravity, the outer periphery of the flammable gas cloud demonstrates a slight downward tendency, gradually descending and spreading outward. A total of 12 s after the gas release, the flammable gas cloud makes contact with the deck and continues to spread radially along the deck surface. As the flammable gas cloud spread further, the working areas of the crew and the air outlets on the deck around the vent mast are all within the scope of gas combustion and explosion, posing a high level of hazard. Following a duration of 15 s, the gas release terminates. The volume of the flammable gas cloud continues to expand further and reaches its maximum at 20 s. The concentration distribution within the flammable gas cloud over the gas release time is shown in Appendix A.

Figure 5.

Flammable gas cloud diagram (concentration greater than 50%LFL) of the natural gas dispersion from a 6 m vent mast over the gas release time. (a) 3 s; (b) 6 s; (c) 9 s; (d) 12 s; (e) 16 s; (f) 20 s.

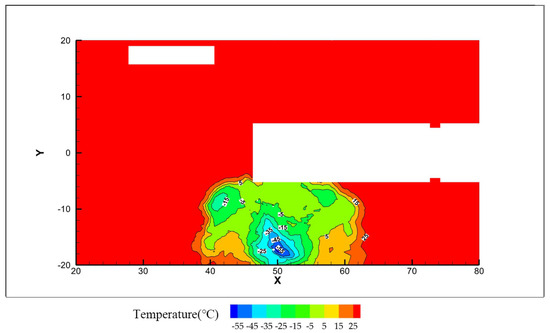

Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the schematic diagrams of the gas concentration distribution and temperature distribution on the deck, respectively. At 20 s after the gas release from the vent mast, it can be observed from Figure 6 that an area within approximately 10 m from the vent mast falls within the flammable gas region. Furthermore, the emergency power generation room is also located within the flammable gas cloud. The gas concentration decreases outward from the vent mast position, and the gas concentration at the center of the gas cloud reaches as high as 30%. When the area with a gas concentration from 2.5% to 15% forms around the vent mast, it creates a core danger zone. At this juncture, the fan, the air inlet and outlet of the ladder way, and even the inlets of the emergency power generation room are all within the range of flammable gas diffusion, posing a highly serious hazard.

Figure 6.

Natural gas concentration distribution on the deck at 20 s after release.

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution on the deck at 20 s after release.

Since the released natural gas is cryogenic, during the release process from the vent mast, it exchanges heat with the environment, resulting in a sharp decline in the temperature of the surrounding environment. Consequently, the gas release has the potential to cause frostbite to the surrounding personnel, steel plate, and equipment [32]. When the gas temperature drops below −25 °C, the probability of personnel frostbite and hull damage is relatively high, and this area is identified as a cryogenic hazard area. As shown in Figure 7, the deck temperature radiates outward from the low-temperature center at the vent mast position, and there exists a certain range of cryogenic hazard area on the deck. The temperature in the cryogenic hazard zone adjacent to the vent mast is below −55 °C, which poses a significant risk of cryogenic injuries to the hull and personnel. The deck material is AH36 steel, which is suitable for temperature scenarios above −20 °C. The cryogenic hazard zone formed on the deck due to gas release will cause the steel structure on the deck to become brittle, which increases the risk of structural damage. In conclusion, when the height of the vent mast on the LNG-powered vessel is not high enough, significant safety risks exist during the gas release process, including gas combustion, gas explosion, and cryogenic injuries.

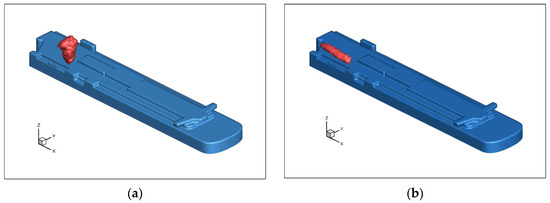

4.1.3. Optimized Design of Vent Mast Height

Given that the maximum trend of gas deposition onto the deck occurs under the windless condition, the optimization design of vent mast height is carried out based on the simulation results depicted in Figure 8. Figure 8 presents the flammable gas cloud range from the vent mast with different heights of 6 m, 10 m, 12.5 m, and 15 m at a wind speed of 0 m/s. When the vent mast height reaches at least 12.5 m, the entire deck surface, including the surrounding fans, air vents of the room, and ladder way, remains outside the flammable gas cloud area, eliminating fire and explosion risks. To further validate the safety of the optimization design, we conduct the safety simulation analysis under varying wind direction and wind speed conditions with a vent mast height of 12.5 m, which is shown in Section 4.2.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of flammable gas cloud (concentration greater than 50%LFL) range from the vent mast under the windless condition with different heights. (a) 6 m; (b) 10 m; (c) 12.5 m; (d) 15 m.

4.2. Wind Direction

Figure 9 displays the flammable gas cloud from the 12.5 m-high vent mast under different wind conditions. As shown in Figure 9, the wind direction significantly influences the gas dispersion behavior from the vent mast. Higher wind speed extends the natural gas to travel farther distances, resulting in the formation of a longer flammable gas cloud. Figure 9 demonstrates that when the vent mast height is 12.5 m, the flammable gas cloud never reaches the deck during gas release with varying wind directions toward sensitive areas. The working area for the crew, the surrounding fan, and critical air outlets remain outside the flammable gas range without combustion and explosion hazards. Therefore, an optimized design of the vent mast height can be implemented for this LNG-powered vessel, reducing it to 12.5 m. This approach proves widely applicable for large dual-fuel Pure Car and Truck Carrier (PCTC) vessels and container-powered ships where excessive ship height necessitates alternative vent mast designs.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of flammable gas cloud (concentration greater than 50%LFL) from the 12.5 m-high vent mast under different wind conditions. (a) Wind direction 1, wind speed 5 m/s; (b) Wind direction 1, wind speed 15 m/s; (c) Wind direction 2, wind speed 5 m/s; (d) Wind direction 2, wind speed 15 m/s; (e) Wind direction 3, wind speed 5 m/s; (f) Wind direction 3, wind speed 15 m/s.

4.3. Wind Velocity

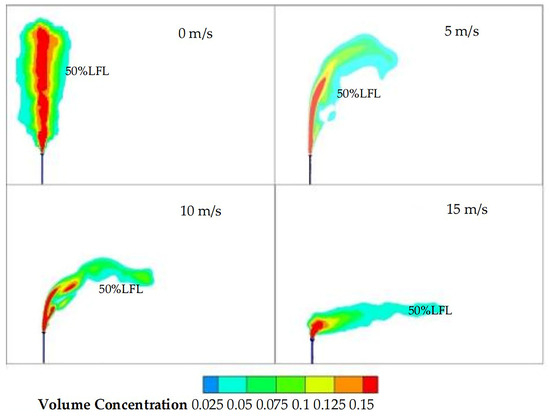

This section further explores the influence of wind velocity on the gas release from the vent mast in detail, and analyzes the dispersion simulation results of gas release under various wind speed conditions of 0 m/s, 5 m/s, 10 m/s, and 15 m/s. The concentration distribution of the flammable gas from the vent mast at different wind speeds is presented in Figure 10. As displayed in Figure 10, the natural gas concentration diminishes from the top of the vent mast towards the periphery while the flammable gas cloud diffuses in the direction of the wind. As the wind speed increases, the concentration distribution extends along the wind direction, and the gas diffusion distance increases in the wind direction. It can be observed from Figure 10 that the height attainable by the combustible gas cloud diminishes, and currently, the size of the flammable gas cloud also reduces with the increase in wind speed.

Figure 10.

The concentration distribution diagram of flammable gas from the vent mast at different wind speeds along the wind direction 3 towards the bow.

Table 5 lists the simulation results of gas volumes under different wind speed conditions. Under wind speeds of 0 m/s, 5 m/s, 10 m/s, and 15 m/s, the maximum volumes of the flammable gas during the gas release are 1737 m3, 400 m3, 357 m3, and 152 m3, respectively. Under the wind speed of 0 m/s, the maximum gas volume is reached at 20 s after gas release, which is 11.4 times that of the condition with a speed of 15 m/s.

Table 5.

Simulation results of gas volumes under different wind speed conditions.

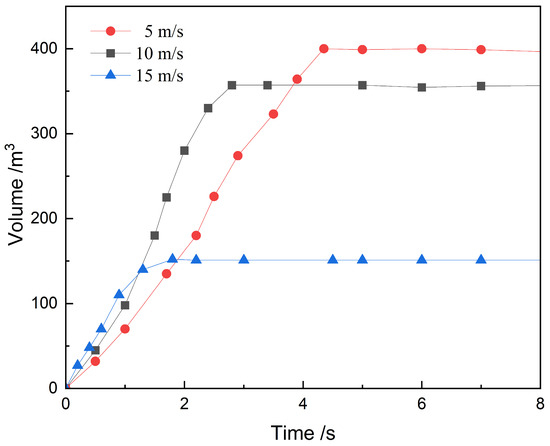

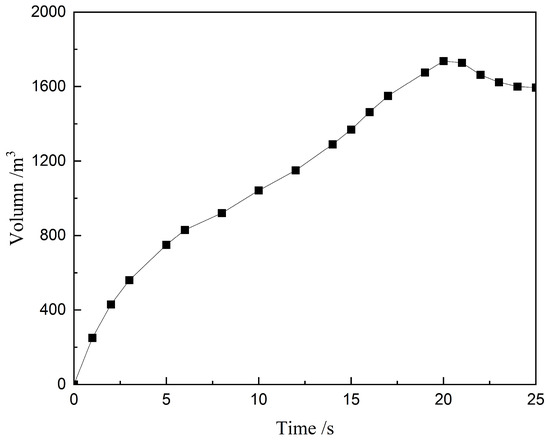

As elaborated in Section 2.1, regions where the gas concentration reaches 2.5% are classified as hazardous areas on LNG-powered vessels. A statistical analysis was carried out on the volume of this hazardous area, that is, the volume of the flammable gas cloud within the 2.5% equal concentration plane. Based on the statistical calculations, the variation in the gas cloud volume with a gas concentration exceeding 2.5% in relation to the gas release time under different wind speed conditions is shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

The gas cloud volume variation with a gas concentration exceeding 2.5% in relation to the gas release time under different wind speed conditions.

Figure 12.

The gas cloud volume variation with a gas concentration exceeding 2.5% in relation to the gas release time under the windless condition at the wind speed of 0 m/s.

As displayed in Figure 11, the volume variation in the flammable gas cloud with the gas release time at the wind velocities of 5 m/s, 10 m/s, and 15 m/s exhibits similar trends. In Figure 11, the volume of the flammable gas cloud increases rapidly subsequent to the commencement of natural gas release from the vent mast. After reaching the maximum, the gas volume tends to stabilize. The maximum volume of the flammable gas cloud decreases notably with the increase in wind velocity. As the wind velocity increases, the rate of gas expansion accelerates while the time to reach the maximum volume of the flammable gas cloud shortens. When the wind velocity is 15 m/s, the volume of the flammable gas cloud is less than half of that at a wind velocity of 5 m/s. Within 2 s of gas release from the vent mast, the volume of the flammable gas cloud reaches a stable peak, which confirms that wind velocity can significantly facilitate gas diffusion.

The windless condition is depicted in Figure 12, where the variation tendency of the volume of the flammable gas cloud with respect to the gas release time from the vent mast exhibits a certain degree of difference compared with that under other conditions in Figure 11. From the initiation to the termination of gas release, the volume of the flammable gas cloud continuously increases at a relatively rapid rate. After the gas release stops at the 15th second, the flammable gas cloud further expands, and its volume further augments, reaching the maximum at 20 s, which is in consonance with the simulation results presented in Section 4.1.2. Subsequently, as the gas diffuses in the atmosphere, the volume of the flammable gas cloud diminishes. At a wind speed of 0 m/s, the maximum volume of the flammable cloud is approximately tenfold larger than that at a wind speed of 15 m/s. Higher wind speeds lead to a shorter duration required for the formation of a stable gas cloud.

4.4. Discussions

The IGF specification allows for alternative designs through equivalent proof methods. As the release of the safety valve on the storage does not permit experiments, the authorization generally recognizes the optimized design of the vent mast through the natural gas release safety analysis. To ensure the accuracy of the simulation, we carry out the sensitivity analysis. Grid independence tests were conducted in Table 2 in Section 3.2 to ensure numerical stability, with mesh refinement beyond 3 million cells showing negligible changes (<0.1%) in output variables. Turbulence model sensitivity was also assessed, with the SST model selected for its balance between computational efficiency and accuracy in recirculating flows. However, this method lacks verification from real-scale ship experimental data. In the subsequent research, we will focus on addressing the issue that regulations and maritime authorities do not allow gas release experiments, and further verify the reliability of the model.

Our optimization design aims to confirm the safety of gas dispersion from the vent mast, which is in line with the overall goal of the IGF Code. In the actual design and construction process of an LNG-powered vessel in a certain large-scale shipyard, such an optimization design method for the vent mast has been applied many times and has been recognized. This approach can be widely applied to meet the design requirements for substituting the vent mast height in large PCTC and container LNG-powered vessels with excessive ship heights, and the target audience includes marine engineers, classification society auditors, and researchers in alternative fuel propulsion systems.

5. Conclusions

The safety analysis of gas dispersion from the vent mast in LNG-powered vessels holds importance for the ship design and the safety operations of crews. Based on the practical ship designs of the LNG-powered vessel, this study employs CFD simulation to analyze the gas dispersion safety behavior during the natural gas release from the vent mast. The research explores the influences of factors on gas dispersion, including vent mast height, wind direction, and wind velocity, and presents an optimization design method to address the issue that the vent mast height on the large LNG-powered ships fails to meet the specifications. The results indicate the following:

- (1)

- The height of the vent mast affects the gas dispersion behavior. A greater height of the vent mast leads to a more favorable upward diffusion trend of the natural gas and a lower risk of gas sedimentation on the deck. When the height of the vent mast reaches 15 m (B/3), the range of the flammable gas cloud does not spread to the deck surface, and the deck area remains within the safe range. When the vent mast height is 6 m, the flammable gas cloud will accumulate on the deck surface under windless conditions, covering the sensitive areas and posing a substantial risk. An explosion and cryogenic hazard area on the deck is formed with the vent mast position as the center, where the gas concentration reaches a maximum of 30% and the minimum temperature is below −55 °C.

- (2)

- The wind direction exerts a significant influence on the gas dispersion behavior from the vent mast. The flammable gas cloud spreads along the wind direction, while the extension distance is positively correlated with the wind speed. A higher wind speed enables natural gas to disperse a greater distance, resulting in the formation of a longer flammable gas cloud. Given that wind direction affects the direction and scope of gas dispersion, during the optimization design of the vent mast height, the wind direction conditions blowing towards surrounding sensitive areas, such as fans, air outlets, and personnel activity areas, should be taken into account to assess the influence of the gas release from the vent mast on the surrounding sensitive areas.

- (3)

- For further exploring the influence of wind velocity on the gas release from the vent mast, the flammable gas cloud volume with a gas concentration exceeding 2.5% over gas release time under varying wind velocity, including 0 m/s, 5 m/s, 10 m/s, and 15 m/s, is computed by the simulation. With the wind velocity increasing, the height attainable by the flammable gas cloud diminishes, while the volume of the stable flammable gas cloud reduces. With the increase in wind speed, the maximum volume of the flammable gas cloud decreases notably, while the time to reach the maximum volume of the flammable gas cloud advances. When the wind speed is 15 m/s, the volume of the flammable gas cloud is less than half of that at a wind speed of 5 m/s and less than one-tenth of that at a wind speed of 0 m/s. Higher wind speed can notably facilitate gas diffusion.

- (4)

- This research outlines a method based on gas dispersion safety simulation for optimizing the vent mast height. Through the optimization design, when the vent mast height is not less than 12.5 m, the flammable cloud remains above deck level in all simulated scenarios, guaranteeing that the surrounding fans and critical air vents remain outside the flammable zone. In the actual design and construction process of the LNG-powered vessel in a certain large-scale shipyard, such an optimization design method for the vent mast has been applied many times and has been recognized. This approach can be widely applied to meet the design requirements for substituting the vent mast height in large PCTC and container LNG-powered vessels with excessive ship heights, and the target audience includes marine engineers, classification society auditors, and researchers in alternative fuel propulsion systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang); methodology, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang); software, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang); validation, Z.W. (Zhangjian Wang); formal analysis, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang) and Z.W. (Zhangjian Wang); investigation, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang); resources, G.C.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W. (Zhaowen Wang); writing—review and editing, Z.W. (Zhangjian Wang); visualization, G.C.; supervision, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by High-tech vessels of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (No. MC2017D01), the Shanghai Post-doctoral Excellence Program (No. 2022498), and the Haibo Program for Innovative and Entrepreneurial Young Talents special support.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhaowen Wang, Zhangjian Wang and Gang Chen are employed by the company Shanghai Waigaoqiao Shipbuilding Co., Ltd.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IGF Code | International Safety Code for Ships Using Gas or Other Low Flash Point Fuels |

| NG | Natural Gas |

| BOG | Boil Off Gas |

| B | Beam of ship |

| LFL | Lower Flammable Limit |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport |

| PCTC | Pure Car and Truck Carrier |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Nomenclature.

Table A1.

Nomenclature.

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| u | Eulerian velocity | m/s |

| p | Pressure | Pa |

| Kinetic viscosity | Pa·s | |

| x | Direction | m |

| e | Internal energy | J |

| K | Thermal conductivity | W/(m·K) |

| J | Diffusion flux | s·m2 |

| S | Chemical reaction heat | J |

| h | Enthalpy | J |

| Q | Release rate at standard condition | m3/s |

| F | Fire exposure coefficient applicable | / |

| G | Gas influencing factor | / |

| A | External area of the storage tank | m2 |

Figure A1.

The concentration distribution diagram of flammable gas from a 6 m vent mast over the gas release time. (a) 3 s; (b) 6 s; (c) 9 s; (d) 12 s; (e) 16 s; (f) 20 s.

References

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Luo, J. Experimental study of the pore structure during coal and biomass ash sintering based X-ray CT technology. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 2098–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankahaluge, A.S.; Graham, T.; Wang, H.; Bashir, M.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Wang, J. Formal Safety Assessment for Ammonia Fuel Storage Onboard Ships Using Bayesian Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhao, X.Z.; Zuo, T.L.; Wang, W.Y.; Song, X.Q. A systematic literature review on port LNG bunkering station. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 91, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlado, V. LNG export diversification and demand security: A comparative study of major exporters. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Bai, Y. Safety design analysis of a vent mast on a LNG powered ship during a low-temperature combustible gas leakage accident. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2021, 7, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LNG-Powered Fleet Will Reach More Than 2000 Vessels as Demand Grows. Available online: https://www.offshore-energy.biz/sea-lng-lng-powered-fleet-will-reach-more-than-2000-vessels-as-demand-grows/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Yarlagadda, B.; Iyer, G.; Binsted, M.; Patel, P.; Wise, M.; McLeod, J. The future evolution of global natural gas trade. iScience 2024, 27, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ju, Y.L.; Fu, Y.Z. Comparative life cycle cost analysis of low pressure fuel gas supply systems for LNG fueled ships. Energy 2021, 218, 119541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gz, A.; Xg, A.; Yan, Y.A.; Wei, T.A.; Chao, J. Experiment and simulation research of evolution process for LNG leakage and diffusion. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 64, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbec, M.; Vidmar, P.; Pio, G.; Salzano, E. A comparison of dispersion models for the LNG dispersion at port of Koper, Slovenia. Safety Sci. 2021, 144, 105467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qu, S.; Zang, Q.; Dong, C.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Z. Leakage failure analysis of a 60 m3 LNG storage tank. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 153, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Murray, R.O.; Fredriksson, S.; Maskell, J.; de Fockert, A.; Neill, S.P.; Robins, P.E. A standardised tidal-stream power curve, optimised for the global resource. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 1308–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofalos, C.; Jeong, B.; Jang, H. Safety comparison analysis between LNG/LH2 for bunkering operation. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Environ. Aff. Shipp. 2020, 4, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannissi, S.G.; Venetsanos, A.G. A comparative CFD assessment study of cryogenic hydrogen and LNG dispersion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9018–9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Q.; Zhao, W.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Jiang, H.L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.Y. Study on the diffusion law of heavy gas leakage in complex scenarios based on scaled-down experiments. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Qu, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S. Simulation of LNG tank container leakage and dispersion on anchoring inland carrying vessel. J. Loss Prevent. Proc. 2024, 92, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubli, H.; Jung, D.; Kim, S.; Sohn, J.M. Structural impact under accidental LNG release on the LNG bunkering ship: Implementation of advanced cryogenic risk analysis. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2024, 186, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, J. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of cryogenic safety analysis in an liquefied natural gas powered ship during liquefied natural gas leakage. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1015904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.A.; Ryu, B.R.; Jung, J.; Kang, H. Comparative analysis on vapor cloud dispersion between LNG/liquid NH3 leakage on the ship to ship bunkering for establishing safety zones. J. Loss Prevent. Proc. 2023, 85, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.F.; Zhou, X.Y.; Cong, B.H. The effect of relative humidity on vapor dispersion of liquefied natural gas: A CFD simulation using three phase change models. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerod. 2022, 230, 105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, M.; Pio, G.; Vianello, C.; Mocellin, P.; Maschio, G.; Salzano, E. Numerical simulation of LNG dispersion in harbours: A comparison of flammable and visible cloud. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 90, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 18683:2021; Guidelines for Safety and Risk Assessment of LNG Fuel Bunkering Operations. ISO Copyright Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Kang, H.K. An Examination on the Dispersion Characteristics of Boil-Off Gas in Vent Mast Exit of Membrane Type LNG Carriers. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. 2013, 19, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaheed, R.; Mohammadian, A.; Shaheed, A.M. Numerical Simulation of Turbulent Flow in River Bends and Confluences Using the k-ω SST Turbulence Model and Comparison with Standard and Realizable k-ε Models. Hydrology 2025, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.; James, G.M.; Shaheed, A.M. Hyperbolic equivalent k-ϵ and k-ω turbulence models for moment-closure Hydrology. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 476, 111881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Xu, C. Simulation and assessment of gas dispersion above sea from a subsea release: A CFD-based approach. Int. J. Nav. Ocean Eng. 2019, 11, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Code of Safety for Ships Using Gases or other Low-Flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code); Resolution MSC.428(98); International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sone, C.; Dong, J.; Zheng, H. An efficient encryption method for smart grid data based on improved CBC mode. J. King Saud. Univ-Com. 2023, 35, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, G.; Choi, W.; Yun, H.; Do, Y.; Kim, K.; Shi, W.; Dai, S.; Kim, D.; Song, S. Evaluation of Free-Surface Exposure Effects on Tidal Turbine Performance Using CFD. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.A. Forced Dispersion of Liquefied Natural Gas Vapor Clouds with Water Spray Curtain Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; He, H.; Gao, A.; Cheng, S.; Gang, C. Study on hazard analysis of gas dispersion from vent mast on dual-fuel PCTC ship. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1–6 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nubli, H.; Sohn, J.M. CFD-based simulation of accidental fuel release from LNG-fuelled ships. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020, 17, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).