Abstract

The combined application of straw biochar and nitrogen fertilizer is an increasingly studied strategy to enhance soil fertility and crop yield. Optimizing the biochar-nitrogen interaction could be a choice for increasing nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and reducing nitrogen loss in dryland agriculture. However, the mechanisms by which it regulates nitrogen allocation and absorption in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) are still limited in terms of mechanical understanding. Based on preliminary experiments, the optimal biochar-nitrogen interaction for soil nutrient absorption was identified. A field experiment was conducted with six treatments in an arid region of northwestern China: N1C1 (N1: 130 kg ha−1 + C1: 100 kg ha−1, control group), N2C4 (N2: 195 kg ha−1 + C4: 250 kg ha−1), N3C1 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C1: 100 kg ha−1), N3C2 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C2: 150 kg ha−1), N3C3 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C3: 200 kg ha−1), and N3C4 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C4: 250 kg ha−1). The results demonstrated that the biochar–nitrogen ratio significantly influenced topsoil total nitrogen, microbial biomass carbon (SMBC), and microbial biomass nitrogen (SMBN). All biochar-to-nitrogen combinations sharply increased soil total nitrogen by 133.11–151.52% compared to pre-sowing levels, providing a fundamental base for microbial-driven nitrogen transformation. Low nitrogen addition is more conducive to biomass accumulation, with N2C4 significantly increasing by 62.82%. Although a high biochar-to-nitrogen ratio reduced leaf relative chlorophyll content (SPAD) by 5.72–16.18% and net photosynthetic rate (Pn) by 16.09–52.65% at the heading stage, these did not compromise final yield. Importantly, N2C4, N3C1, and N3C4 significantly increased spike 15N abundance by 71.45%, 13.21%, and 19.43%, respectively. N2C4 grain production increases by 53.77–110.57% in two years and was positively correlated with spike 15N abundance, reflecting high nitrogen partial factor productivity. In conclusion, a reasonable biochar-nitrogen interaction enhances nitrogen allocation and grain yield by stimulating microbial activity and strengthening soil–plant synergy, the certified strategy effectively supports sustainable dryland agriculture by simultaneously increasing productivity and improving soil health.

1. Introduction

As social development progresses and the demand for high-quality grains continues to grow, sustaining the functionality of agricultural ecosystems and ensuring food security are increasingly important. The foundation of agricultural development lies in enhancing the sustainable productivity of soil [1,2,3]. Farmland management measures have been shown to improve the soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties, promote its nutrient-supplying capacity, and mitigate degradation [4,5,6]. Among the mineral nutrients required by plants, nitrogen is needed in the greatest quantities and is pivotal for maintaining global crop yields [7]. However, excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers in agricultural ecosystems leads to nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas, through nitrate leaching, runoff, and volatilization, adversely affecting the environment through eutrophication of surface waters, nitrate pollution of groundwater, acid rain and soil acidification, greenhouse gas emissions, and other forms of air pollution. This substantially diminishes nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and reduces economic returns for farmers [8,9,10]. Improving NUE is therefore critical to addressing food security, environmental degradation, and climate change and is a prerequisite for green agricultural development [11].

Biochar is a highly aromatic and chemically stable solid material produced from the pyrolysis of agricultural and forestry biomass under oxygen-limited conditions [12,13]. Straw biochar embodies the circular principle of being “derived from agriculture and used in agriculture” [14,15,16,17]. Biochar possesses a highly porous structure and, as a soil amendment, enhances soil physicochemical properties. By increasing CEC and pH, it improves the soil’s ability to adsorb and retain nutrients like ammonium nitrogen, thereby providing a more synchronized and sustainable supply for crops. These improvements, coupled with stimulated microbial activity, retard nutrient release and reduce leaching losses, thereby effectively increasing crop yields [18,19,20]. These characteristics make it an ideal amendment for agricultural applications. While appropriate nitrogen application enhances crop dry matter accumulation, yield, and quality, excessive fertilization increases production costs, reduces NUE, and can lead to soil pollution and suppressed microbial activity. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) is highly sensitive to nitrogen deficiency during growth, and inadequate nitrogen supply severely restricts plant development. The application of farmyard manure or biochar in combination with nitrogen has been shown to mitigate the negative effects of excessive nitrogen fertilizer use and enhance soil microbial activity [21,22]. For instance, the combined application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer has been demonstrated to enhance wheat and rice yield and significantly reduce nitrogen fertilizer loss [22,23,24]. Optimizing the biochar-to-nitrogen ratio can improve the source-sink relationship, promote dry matter accumulation, and facilitate the translocation of available nitrogen to grains, providing an effective strategy for increasing crop productivity [25,26]. While achieving high yields and efficient nutrient use is critical, it is equally important to ensure long-term soil sustainability. Soil microbial biomass carbon (SMBC) and nitrogen (SMBN), which represent the total carbon and nitrogen contained within the living microbial fraction of the soil, serve as key indicators of microbial activity and metabolic potential. The absolute values and ratios of these parameters are widely used to evaluate soil health, fertility status, and organic matter management efficacy. Elevated SMBC/SMBN ratios generally suggest more active microbial communities and improved soil quality. Recent studies [27,28,29] further demonstrate that, compared to the sole application of either component, co-application of nitrogen fertilizer and biochar significantly enhances soil nutrient availability and exhibits stronger synergistic effects on soil properties and crop performance.

Current research on the synergistic application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer has well established its benefits for enhancing crop yield and improving soil nutrient status. However, the optimal biochar-to-nitrogen ratio for increasing foxtail millet yield, reducing nitrogen fertilizer application, and enhancing soil health in drylands requires further investigation. Therefore, this study focuses on the dryland region of northern Shaanxi, an area characterized by distinctive soil texture, low vegetation coverage, and heightened susceptibility to nutrient loss. Based on a two-year field experiment, we aim to elucidate the mechanisms of nitrogen distribution in the aboveground organs of foxtail millet under different biochar-to-nitrogen ratios. Preliminary results confirm that the carbon–nitrogen interaction positively influences soil health. By determining a reasonable application ratio, this study seeks to provide a scientific basis for enhancing nitrogen use efficiency, reducing nutrient loss, and establishing sustainable and fertilizer-saving agricultural practices in dryland agroecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Soil Condition

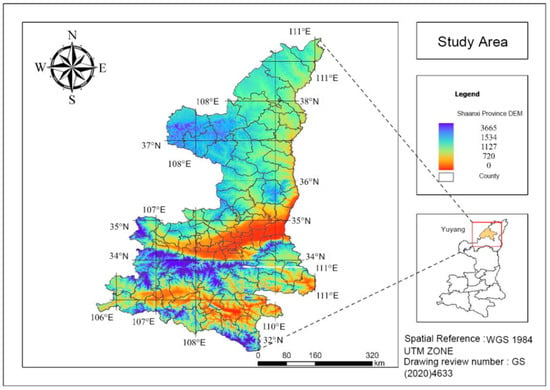

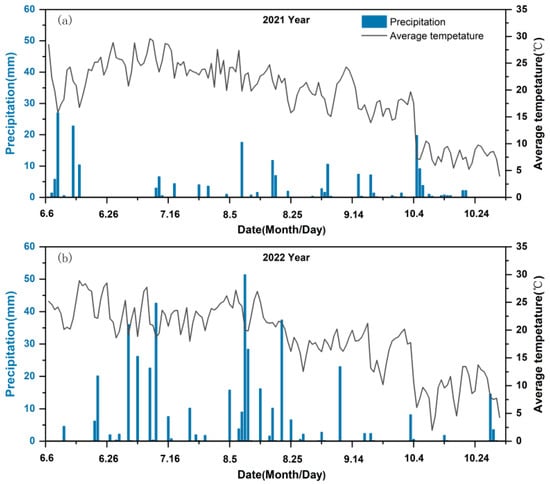

The field experiment was conducted from May to October 2021–2022, with preliminary trials carried out simultaneously in 2021. The site is located in Qingyun Town, Yuyang District, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province (38°26′17″ N, 109°84′11″ E) (Figure 1). This region has an elevation of 1136 m and exhibits a typical arid to semi-arid continental monsoon climate. The annual average precipitation ranges from 410.0 to 446.8 mm, with uneven seasonal distribution, and the annual average temperature ranges from 8.3 °C to 10.5 °C, with significant diurnal fluctuations. The annual sunshine duration is 2644 h, and the evaporation rate is 1211 mm. The soil is identified as a loessal soil, derived from wind-blown silt deposits. According to the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB). Prior to planting, the soil (0–30 cm depth) contained an organic carbon content of 0.99 g kg−1, a total nitrogen content of 0.32 g kg−1, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen of 18.9 mg kg−1, available potassium of 148.0 mg kg−1, and available phosphorus of 6.5 mg kg−1. The rainfall and average temperature during the crop-growing seasons of 2021 and 2022 are presented in (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The experimental site is located in Yuyang District.

Figure 2.

Average temperature and precipitation during the two experimental years in 2021 (a) and 2022 (b).

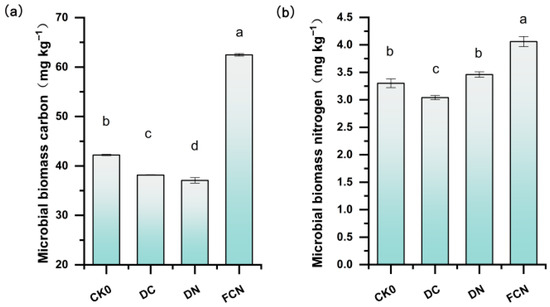

2.2. Materials

The drought-tolerant foxtail millet variety “Jingu 21” from the Loess Plateau was used as the experimental material. The experiment employed a randomized block design, with sites selected on typical dryland agricultural fields of the Loess Plateau that were flat and had a slope of <3°. The fertilizers applied were urea (containing 46% nitrogen) and straw biochar. The experimental plots were arranged in a split-plot design. The preliminary experiment comprised four treatments with three replicates: CK0 (control group), DC (biochar 200 kg ha−1), DN (nitrogen fertilizer 90 kg ha−1), and FCN (biochar 200 kg ha−1 + nitrogen fertilizer 90 kg ha−1). Based on the preliminary results, the combined application of biochar and nitrogen significantly increased SMBC and SMBN. Consequently, the formal experiment focused on C/N-regulated treatments, with the following levels: N1C1 (N1: 130 kg ha−1 + C1: 100 kg ha−1, control group), N2C4 (N2: 195 kg ha−1 + C4: 250 kg ha−1), N3C1 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C1: 100 kg ha−1), N3C2 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C2: 150 kg ha−1), N3C3 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C3: 200 kg ha−1), and N3C4 (N3: 260 kg ha−1 + C4: 250 kg ha−1). A total of six treatments were established, each with three replicates. The plot area was 20 m2, with a row spacing of 50 cm and a seeding density of 300,000 plants ha2. A 50 cm protective row was maintained between plots. For the isotope trial, one plot was randomly selected from each treatment, and a bottomless PVC frame was buried to a depth of 50 cm. Within this frame, a 1 m2 microplot was selected at the center, characterized by flat terrain, uniform plant growth, and consistent density, for the 15N isotope tracer experiment.

2.3. Measurement Methods and Indicators

2.3.1. Above-Ground Biomass and Dry Matter Accumulation Rate

During the critical growth period of foxtail millet, three representative plants were collected from each plot. The stems, leaves, and spikes of each plant were separated and initially dried in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min. Then dry these separated plant parts to constant weight at 75 °C. The biomass of stems, leaves, and spikes is determined by weighing each part separately. The dry matter accumulation rate for each period was calculated based on the measured dry matter weight, where M1 is the dry matter weight at the first sampling (g), M2 is the dry matter weight at the second sampling (g), t1 is the time of the first sampling, and t2 is the time of the second sampling. The calculation uses the following formula:

2.3.2. 15N Isotope Tracing and Calculation Method

At the mature stage, stem, leaf, and spike samples were collected from plots treated with 15N-labeled fertilizer. The samples were separately dried to constant weight and finely ground. The total 15N atom% of each sample was determined using isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS). Using the combustion method to measure gases in an elemental analyzer (EA) (Elementar GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). The measurements are based on isotope enrichment analysis. Consequently, the 15N atom% excess (APE) was calculated as the difference in 15N atom% between the labeled samples (stems, leaves, and spikes) and their corresponding unlabeled (control) counterparts. It was calculated as follows:

2.3.3. Determination of Soil Organic Carbon, Total Nitrogen, Alkali-Hydrolyzable Nitrogen, Microbial Biomass Carbon and Nitrogen, and Available Phosphorus and Potassium

Prior to sowing and during the critical growth period, soil samples (0–30 cm tillage layer) were collected. The samples were air-dried naturally for the determination of total nitrogen content using the fully automatic Kjeldahl method. Soil organic carbon was determined by the Walkley-Black wet oxidation method (potassium dichromate oxidation) and titrated using a digital burette (Knick GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen was extracted and quantified using the alkali diffusion method (1.8 mol·L−1 NaOH hydrolysis) with boric acid absorption and titration. Available phosphorus was extracted with a double acid solution (0.05 mol·L−1 HCl + 0.025 mol·L−1 H2SO4) and determined colorimetrically by the molybdenum-antimony anti-spectrophotometric method. Available potassium was extracted with 1 mol·L−1 neutral ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) and measured using a flame photometer (Jenway, Staffordshire, UK). The conversion factor for instrumental analysis of microbial biomass carbon is 0.45, while the conversion factor for microbial biomass nitrogen analysis is 0.25.

2.3.4. Measurement of Chlorophyll and Photosynthesis

During the critical growth period, measurements were conducted on a sunny day. At 10:00 AM, the net photosynthesis rate (Pn) and SPAD of mature flag leaves were measured on three representative plants using an SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan) and a Li-6400 portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), respectively. When measuring photosynthesis, the environmental conditions inside the leaf chamber are controlled as follows: the light intensity is 1000 μmol m−2 s−1, the flow rate is set to 500, the CO2 concentration is 455–456 ppm, and the data of each leaf is recorded after it stabilizes.

2.3.5. Yield Measurement

At maturity, a 2 m × 2 m area was selected from the center of each plot. All effective spikes from this area were harvested, dried, threshed, and weighed. Grain yield was adjusted to a moisture content of approximately 13% and expressed per unit area.

2.3.6. Nitrogen Partial Factor Productivity

The yield was calculated based on the post-harvest measurement of each plot. The nitrogen partial factor productivity was calculated using the following formula (note: this metric reflects partial factor productivity):

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2010. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Significant differences between treatment means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT), at a significance level of p < 0.05. Figures were plotted using Origin 2021.

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of Biochar and Nitrogen Fertilizer on Microbial Carbon and Microbial Nitrogen Contents in Soil and Total Nitrogen

3.1.1. Preliminary Experiment: Influence of Microbial Carbon and Microbial Nitrogen Contents in Soil

Compared with CK0, FCN significantly increased soil MBC by 48% (p < 0.05), while DC and DN decreased it by 9.59% and 12.15%, respectively (Figure 3a). DN and FCN increased soil MBN by 4.85% and 23.03%, respectively, compared to CK0 (Figure 3b), whereas DC decreased it by 7.88% compared to CK0. Compared with the application of nitrogen fertilizer or biochar alone, the combined application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer significantly enhanced the soil microbial activity of foxtail millet and demonstrated a stronger potential for synergistic effects.

Figure 3.

Changes in soil microbial carbon (a) and microbial nitrogen contents (b) at different stages of maturity under different treatments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

3.1.2. Comparison of Soil Total Nitrogen Content

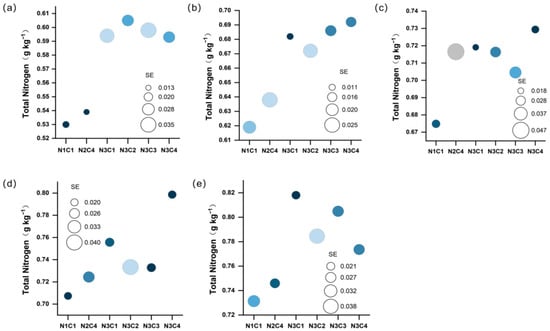

Soil total nitrogen is a critical indicator of soil fertility. The total nitrogen content before sowing was 0.32 g kg−1. Under various biochar-to-nitrogen ratio gradients, total nitrogen content showed a gradual increasing trend as the growth stage progressed. The low biochar-to-nitrogen ratio was significantly lower than the other treatments at all growth stages (Figure 4a–e). At the seedling stage, the total nitrogen content of each treatment increased by 65.63–87.50% compared with that before sowing. At the jointing stage, the other five treatments increased by 3.07–11.79% compared with the control group. During the booting stage, with the increase in biochar-to-nitrogen ratio, total nitrogen in N3C3 and N3C4 increased by 4.40% and 8.08%, respectively. At the heading stage, the N3C4 treatment exhibited the highest content, followed by N3C1; these values represented significant increases of 12.92% and 6.85%, respectively, compared to the control group (p < 0.05). At maturity, the high biochar-to-nitrogen ratio treatments resulted in an increase of 2% to 10.05% compared to the control group. More notably, at maturity, all treatments showed an increase of 133.11% to 151.52% compared to the pre-sowing level. These results indicate that the combined application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer can significantly promote the accumulation of total nitrogen in the soil.

Figure 4.

Distribution of total soil nitrogen across different carbon-nitrogen gradients during the seedling stage (a), jointing stage (b), booting stage (c), heading stage (d), and maturity stage (e), respectively. The size of the circle is related to the standard error (SE).

3.2. Comparison of Biomass and Dry Matter and Accumulation Rate

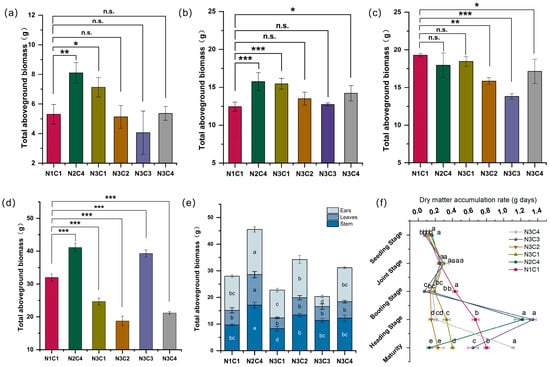

As shown in (Figure 5a–d), with the progression of the growth period, biomass accumulation under the N2C4 treatment was particularly prominent. During the seedling and jointing stages, above-ground biomass was higher in the control group and under N2C4, indicating that a moderate addition of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer during the early growth stages can enhance biomass accumulation in millet. At the seedling stage, N2C4 and N3C1 increased by 52.81% and 34.40%, respectively, compared to the control group, while N3C2 and N3C3 showed no significant differences from the control group. At the jointing stage, N2C4, N3C1, and N3C4 significantly increased above-ground biomass by 26.67%, 24.30%, and 14.26%, respectively, compared to the control group (p < 0.05). During the booting stage, biomass under the other five treatments decreased by 4.39% to 28.40% compared to the control group. At the heading stage, N2C4 increased by 28.65% compared to the control group. At maturity, total biomass under N2C4, N3C2, and N3C4 was higher than under the other treatments (Figure 5e), increasing by 62.82%, 22.44%, and 11.39%, respectively, compared to the control group. In contrast, N3C1 and N3C3 decreased significantly by 18.73% and 27.18%, respectively, compared to the control group. For spike biomass, N2C4 was clearly higher than the other treatments at 16.97 g. Leaf biomass under N2C4 was also the highest, significantly exceeding that of the other treatments. Stem biomass under N3C1 was the smallest, while N2C4, N3C2, N3C3, and N3C4 increased by 17.75% to 76.65% compared to the control group. These results indicate that the biochar-to-nitrogen ratio played a significant role at different growth stages of foxtail millet. However, either low or excessively high application rates of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer were detrimental to biomass accumulation.

Figure 5.

Accumulation of aboveground biomass during the seedling stage (a), jointing stage (b), booting stage (c), and heading stage (d), under different biochar-to-nitrogen gradients; biomass accumulation of stem, leaf, and spike organs at maturity stage (e) (Note: The units of figures (a–e) are g plants−1); dry matter accumulation rate (f) (Note: The unit of figure (f) is g plant−1 day−1). *, **, and *** indicate significance at p < 0.1, p < 0.05, and p < 0.01, respectively; different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between biochar and nitrogen gradients; n.s., no significant difference.

Under N2C4 at the seedling stage, the dry matter accumulation rate was the highest, increasing by 48.45% compared to the control group (Figure 5f). At the jointing stage, the dry matter accumulation rate increased with the biochar-to-nitrogen ratio gradient. Compared with the control group, the increase in dry matter accumulation rate under other treatments ranged from 6.73% to 22.94%. During the booting stage, the dry matter accumulation rate exhibited varying degrees of decline compared to the control group, with other treatments decreasing by 56.25% to 83.60%. At the heading stage, the dry matter accumulation rate under N3C3 reached its peak, with an average daily increase of 1.33 g, which was 100.99% higher than that of the control group. N2C4 also showed a sharp increase, representing an 82.99% gain compared to the control group. At maturity, the control group and N3C4 maintained a high dry matter accumulation rate. These results indicate that the gradient of biochar and nitrogen application significantly affected the dry matter accumulation rate at different growth stages.

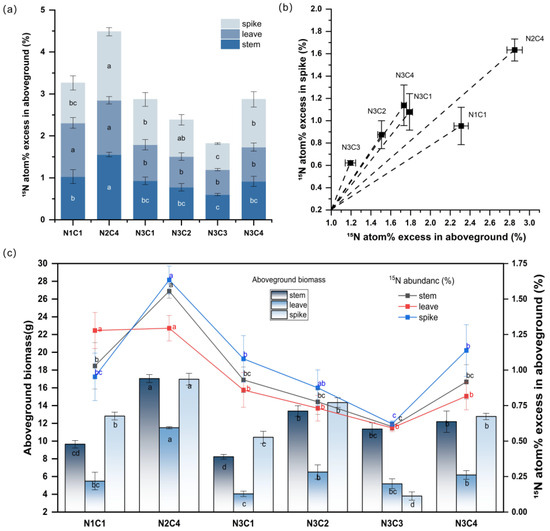

3.3. Comparison of Nutrients and 15N Abundance in Reproductive Organs of Foxtail Millet

At maturity, under low biochar-to-nitrogen ratio conditions, the 15N abundance of foxtail millet was relatively high. Under the N3 gradient, as the biochar gradient increased, the 15N abundance initially declined and then increased (Figure 6a). The 15N abundance of N2C4 was significantly higher than that of other treatments, representing an increase of 37.49% compared to the control, indicating that an appropriate proportional gradient improved nitrogen fertilizer utilization efficiency. Under the N3 gradient, N3C1, N3C2, N3C3, and N3C4 resulted in significant reductions of 12.05%, 26.86%, 44.23%, and 12.05%, respectively (p < 0.05). These results demonstrate that increasing nitrogen fertilizer application does not necessarily lead to higher 15N abundance in aboveground tissues; instead, moderate low nitrogen combined with biochar can stimulate nitrogen uptake. Furthermore, an appropriate biochar-to-nitrogen ratio significantly improved nitrogen transport within the aboveground organs of foxtail millet.

Figure 6.

Distribution of 15N abundance in stem, leaf, and spike under different biochar and nitrogen application gradients (a), the ratio of 15N abundance between aboveground plant parts and spike (b), and the relationship between 15N abundance in stems, leaves, and spike and dry weight (c). The data values used in the image are listed in (Table 1) below. The data here are means ± standard errors (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) at p < 0.05.

A low nitrogen fertilizer gradient clearly enhanced nitrogen use efficiency in the aboveground parts of foxtail millet, leading to a marked increase in dry matter accumulation (Figure 6c). The aboveground stems, leaves, and spikes exhibited different responses under different biochar-to-nitrogen ratios. The 15N abundance in N2C4 stems showed significant differences compared to other treatments, with a 51.09% increase relative to the control group. Under the N3 gradient, the four treatments decreased by 9.57–41.51% compared to the control group. Stem biomass under N2C4 and the N3 gradient significantly increased by 76.65% and 17.75–38.65%, respectively, compared to the control group. There was no significant difference in 15N abundance in leaves between the control group and N2C4, while under the N3 gradient, the four treatments decreased by 32.76–53.62% compared to the control group. However, leaf biomass underwent significant changes; compared to the control group, leaf biomass in N2C4 increased by 109.47%, indicating that N2C4 substantially promoted leaf growth. Leaves are primarily responsible for photosynthesis and the synthesis of organic matter.

The foxtail millet spike is the core yield organ, and its nitrogen absorption and distribution efficiency (especially 15N) significantly contribute to final yield formation. The 15N abundance in N2C4, N3C1, and N3C4 spikes increased by 71.45%, 13.21%, and 19.43%, respectively, compared to the control group, while N3C2 and N3C3 decreased by 8.18% and 34.78%, respectively. In terms of spike biomass, N2C4 and N3C2 increased by 32.41% and 11.89%, respectively, compared to the control group; N3C1, N3C3, and N3C4 decreased by 18.63%, 70.29%, and 0.28%, respectively. As illustrated in (Figure 6c), under the N2C4 treatment, the spike exhibited the strongest nitrogen accumulation capacity, whereas a high biochar-to-nitrogen ratio was not conducive to nitrogen transport and biomass accumulation.

The transport and distribution efficiency of nitrogen from aboveground parts to the spike was highest under N2C4, with N3C3 ranking lowest (Figure 6b). In the figure, N2C4 exhibits a higher proportion of 15N in the spike relative to the aboveground of 15N (15N atom% excess in aboveground), indicating a strong preferential allocation of the labeled nitrogen to the reproductive sink. This suggests that during foxtail millet development, nitrogen allocation shifts from an initial xylem-dominated distribution toward efficient phloem-mediated remobilization from source organs to the reproductive sink. In contrast, treatments such as N3C3 appear lower on the plot, reflecting a larger retention of absorbed 15N in stems and leaves; consequently, lower phloem transfer efficiency to the spike. Under the optimal N2C4 treatment, the maximum isotope ratio between the spike and aboveground parts is close to 1, indicating that the peak reaches a value close to the maximum 15N abundance. An appropriate carbon/nitrogen ratio is an efficient way to promote nitrogen absorption to yield formation.

Table 1.

15N atom% excess (APE) in stems, leaves, and spikes of foxtail millet under different treatments.

Table 1.

15N atom% excess (APE) in stems, leaves, and spikes of foxtail millet under different treatments.

| Treatment | Stem (15N Atom% Excess) | Leaf (15N Atom% Excess) | Spike (15N Atom% Excess) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1C1 | 1.03 ± 0.16 b | 1.28 ± 0.13 a | 0.95 ± 0.17 bc |

| N2C4 | 1.56 ± 0.05 a | 1.30 ± 0.09 a | 1.63 ± 0.1 a |

| N3C1 | 0.93 ± 0.09 bc | 0.86 ± 0.12 b | 1.08 ± 0.16 b |

| N3C2 | 0.78 ± 0.09 bc | 0.73 ± 0.09 b | 0.86 ± 0.13 ab |

| N3C3 | 0.60 ± 0.03 c | 0.59 ± 0.03 b | 0.62 ± 0.02 c |

| N3C4 | 0.92 ± 0.12 bc | 0.82 ± 0.10 b | 1.14 ± 0.18 b |

Values are mean ± standard deviation. Different lowercase letters within a column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

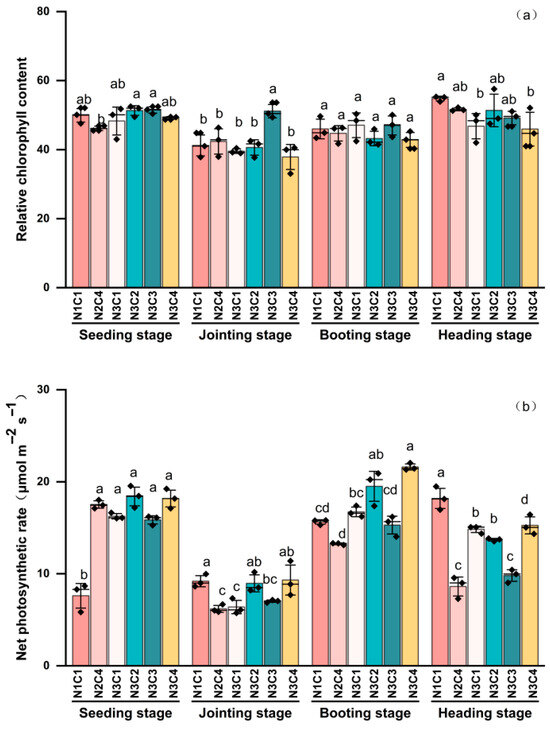

3.4. Comparison of Leaf Photosynthetic Parameters

SPAD exhibited different trends across varying biochar-to-nitrogen gradients (Figure 7a). The control group, N2C4, N3C2, N3C3, and N3C4, showed an initial decrease followed by a gradual increase throughout the growth cycle. Unlike the other treatments, N3C1 exhibited an initial decline followed by a more pronounced increase. Initial SPAD values were similar at the seedling stage, as treatment effects had not yet fully manifested. Compared to the seedling stage, the significant decrease in SPAD across all treatments during the jointing stage may have been due to rapid growth; nitrogen was preferentially allocated for stem elongation, potentially leading to a “dilution” of SPAD. At the jointing stage, except for N3C3, SPAD in all other treatments decreased significantly, coinciding with a shift in the plant’s growth focus. Nitrogen and photosynthetic products were preferentially utilized for stem elongation, likely influencing SPAD levels.

Figure 7.

Effect of different biochar-to-nitrogen application gradients on SPAD (a) and Pn (b). Data are presented as means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

The booting stage represents the early reproductive growth stage of foxtail millet, where nitrogen demand increases; however, no significant differences were observed between treatments. By the heading stage, SPAD showed an overall upward trend. The control group and N2C4 plants had relatively high SPAD content, although the value for N2C4 was 5.72% lower than that of the control group. The four treatments under the N3 gradient decreased by 2.27% to 16.18% compared to the control group. These results suggest that a moderate nitrogen addition can promote SPAD accumulation in the later growth stages.

Pn is an important indicator of plant photosynthetic efficiency and growth potential, playing a vital role in dry matter accumulation and environmental adaptation. During the early growth stage of foxtail millet, Pn in the control group was significantly lower than in the other treatments; however, it increased gradually as the growth period progressed. In contrast, the other five treatments exhibited an initial decrease, followed by a mid-growth increase, and a subsequent decline (Figure 7b). At the seedling stage, these treatments showed a significant increase of 108.41% to 141.79% compared to the control group, indicating that a higher biochar-to-nitrogen ratio during early growth was more conducive to enhancing Pn. Pn in all treatments decreased during the jointing stage, reaching the lowest values observed throughout the growth period. Notably, the control group was significantly higher at this stage. The other five treatments decreased by 2.19% to 35.07% compared to the control group (p < 0.05), indicating that high biochar-to-nitrogen ratios inhibited Pn at this stage. The increase in Pn during the booting stage may have been due to increased demand for photosynthetic products for grain development, prompting plants to upregulate photosynthetic capacity. Pn decreased significantly by 15.25% and 2.17%, respectively (p < 0.05), in some treatments, while N3C1, N3C2, and N3C4 increased by 6.90%, 24.73%, and 38.19%, respectively. By the heading stage, the control group reached its peak Pn, whereas the other treatments decreased by 16.09% to 52.65%, suggesting that high biochar-to-nitrogen ratios may have variably inhibited Pn.

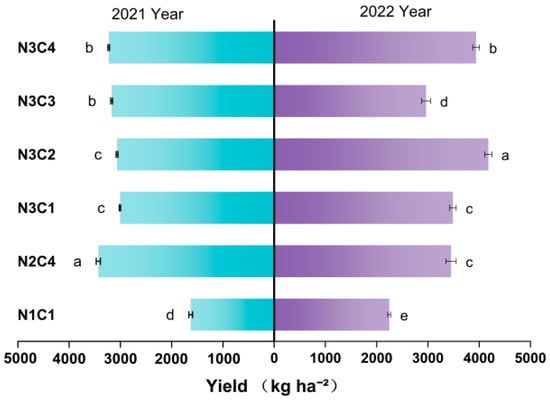

3.5. Comparison Between Yield

As shown in Figure 8, foxtail millet yield over the two-year study period did not exhibit a positive correlation with an increasing biochar-to-nitrogen ratio gradient. The four treatments under the N3 gradient (N3C1, N3C2, N3C3, N3C4) showed increases ranging from 55.36 to 84.67%, 86.11 to 88.22%, 32.09 to 94.64%, and 75.50 to 98.12%, respectively, over the two years. Compared to other gradients, the N2C4 treatment exhibited significant advantages in yield. Compared to the control group, the N2C4 treatment yielded the highest production in both years, with increases of 110.57% and 53.77%, respectively. The application of a moderate amount of biochar combined with nitrogen fertilizer enhanced foxtail millet production. Yields in 2022 were significantly higher than in 2021, a difference that may have been influenced by rainfall.

Figure 8.

Effect of different biochar-nitrogen application gradients on yield. Data are presented as means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

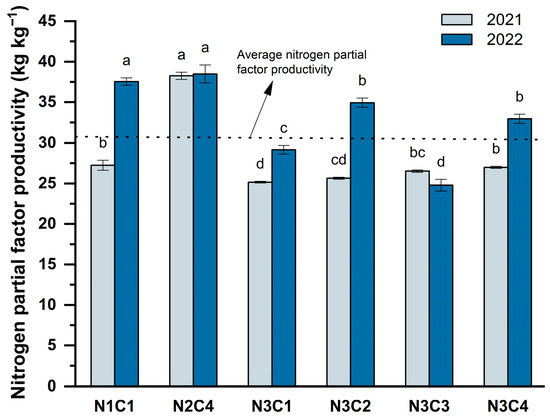

3.6. Comparison of Nitrogen Partial Factor Productivity

As presented in Figure 9, nitrogen application significantly enhanced nitrogen partial factor productivity within an appropriate dosage range, with statistically significant differences observed among the treatments (p < 0.05). Over the two-year study period, nitrogen partial factor productivity in the N2C4 treatment remained relatively stable, ranging from 38.25 to 38.49 kg. At an equivalent nitrogen application rate, the variation in nitrogen partial factor productivity was minimal in N3C1 and N3C3. Conversely, excessive nitrogen fertilization resulted in a marked decline in nitrogen use efficiency, an effect that was particularly pronounced in sandy soils with limited nutrient retention capacity.

Figure 9.

Effect of different biochar-to-nitrogen application gradients on nitrogen partial factor productivity. Data are presented as means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

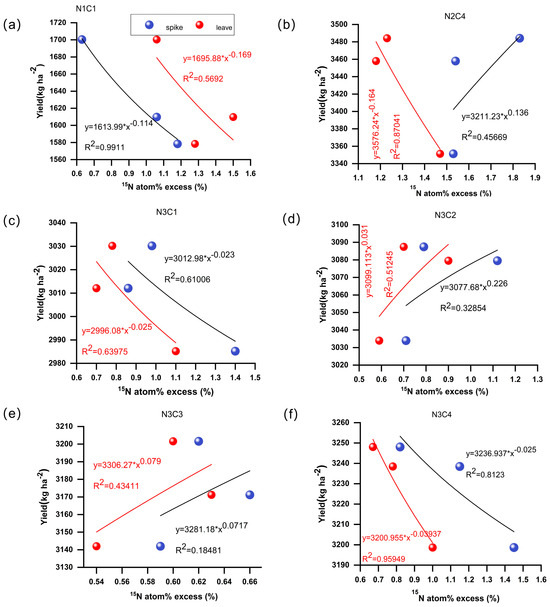

3.7. Fitting Curves of the Correlation Between Yield and 15N Abundance

A significant correlation was observed between aboveground nitrogen isotopes of abundance and their contribution to yield formation. The fitting curves for the correlation between 15N abundance in spikes and leaves at harvest and yield exhibited distinct trends among the treatments (Figure 10). Except for N2C4, where yield decreased as leaf 15N abundance decreased, all other treatments exhibited a consistent positive or negative correlation between leaf 15N abundance and yield. The relationship between spike 15N abundance and yield for N2C4, N3C2, and N3C3 showed a positive trend, with the highest R2 of 0.45669 observed for N2C4. For N3C2, yield increased with increasing leaf 15N abundance, resulting in an R2 of 0.51245.

Figure 10.

Correlation between 15N abundance in mature spike and yield. Figures (a–f) represent different treatments, respectively. N1C1 (a), N2C4 (b), N3C1 (c), N3C2 (d), N3C3 (e), N3C4 (f).

4. Discussion

The changes in soil carbon and nitrogen play an important role in agricultural ecosystems. Soil organic carbon and organic nitrogen are important combinations that affect soil nitrogen supply capacity, and their content directly determines the level of soil nitrogen supply capacity [30]. Soil total nitrogen is the primary source of nitrogen for plants, directly influencing crop growth, development, and yield formation [31]. As a crucial mineral nutrient, nitrogen plays a vital role in crop growth. The addition of straw biochar can increase soil total nitrogen content by enhancing the soil’s nitrogen retention capacity [32,33]. Biochar, when applied in combination with nitrogen fertilizers, can significantly enhance soil nutrient availability. Nitrogen fertilizers are susceptible to losses through processes such as ammonia volatilization and leaching [34]; however, biochar can mitigate these losses by directly adsorbing ammonium, reducing leaching, and improving soil water retention, thereby attenuating strong leaching events [35]. Previous studies have shown that the combined application of biochar and nitrogen can increase soil cation exchange capacity and surface area, thereby enhancing soil nutrient availability [36,37]. In this study, the results indicated that different biochar and nitrogen fertilizer gradients had varying enhancing effects on soil total nitrogen across all growth stages (Figure 4). At maturity, the high biochar-to-nitrogen ratio treatments showed an increase ranging from 2% to 10.05% compared to the control group. The application of high biochar-to-nitrogen ratios significantly maintained and enhanced soil total nitrogen content, thereby contributing to the preservation of soil fertility and sustainable land productivity. Other studies have corroborated that the beneficial regulation of nitrogen is not attributable to biochar alone but arises from its synergistic interaction with nitrogen fertilizer [38]. Similarly, Refs. [39,40] reported that biochar can effectively reduce the leaching of aluminum, iron, manganese, and NH4+, with particularly pronounced improvements in nutrient adsorption capacity in sandy soils.

Moderate nitrogen fertilizer application enhances nitrate transport capacity, promoting foxtail millet growth [41], whereas application rates below the recommended level slow crop growth and development [42]. Conversely, excessive nitrogen application does not enhance plant nitrogen uptake capacity and fails to produce agronomic benefits [43]. In this study, the results indicated that the N2C4 treatment facilitated more effective nitrogen absorption in aboveground tissues, resulting in prominent nitrogen accumulation. This aligns with the principle that the combined application of biochar and nitrogen reduces the risk of nitrogen loss due to the strong adsorption capacity of biochar, thereby increasing the UNH4 (uptake rate)/INH4 (immobilization rate) ratio, a phenomenon supported by findings that plants significantly stimulate gross N mineralization and nitrification while competitively acquiring NH4+, leading to higher plant uptake relative to microbial immobilization [44]. As nitrogen absorption and translocation play a critical role in determining final yield [36], the observed nitrogen isotope signatures suggested that the N2C4 treatment promoted the preferential translocation of limited nitrogen to the spike (Figure 6a), demonstrating superior nitrogen absorption. Furthermore, N2C4 consistently produced the highest yield over two consecutive years (Figure 8). Conversely, high nitrogen application hindered nitrogen absorption and transport in stems, leaves, and spikes. This was possibly due to an increase in soil active matter from high biochar-to-nitrogen ratios, which impaired nitrogen availability. The introduction of active substances via a high C/N ratio can stimulate microbial fixation of soil mineral nitrogen, thereby reducing its availability. Adding biochar to the soil can contribute to the maintenance of TOC, thereby reducing carbon losses in the form of CO2 and altering soil microbial activity and diversity [45]. Overall, nitrogen fertilizer application rates significantly influence nitrogen absorption and transport within foxtail millet plants, which is consistent with the findings from a meta-analysis by [46]. Nitrogen is not the only factor limiting yield (Figure 10), and the application of other elements (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) can fully reflect the nitrogen fertilizer effect. Climate and variety factors also have an impact on yield. Finally, absorption preference may also be influenced by different nitrogen forms, such as ammonium and nitrate nitrogen [47].

Nitrogen fertilizer plays a key role in the synthesis of Rubisco enzymes during foxtail millet growth, and these enzymes contribute to chlorophyll synthesis in the chloroplasts of foxtail millet leaves [48]. The results of this study indicated that the application rate of biochar within a certain range significantly affected SPAD and Pn in foxtail millet (Figure 7). While excessive nitrogen uptake may impair chlorophyll decomposition, resulting in delayed maturity or premature senescence due to insufficient photosynthesis [49], this study found that SPAD increased throughout the growth period across all treatments (Figure 7a). However, at the critical heading stage, compared with the control group, the other five treatments showed decreases in SPAD ranging from 5.72% to 16.18% (Figure 7b). Photosynthetic capacity is a critical determinant of crop growth, development, and yield formation [50]. Enhancing Pn in crop leaves promotes the accumulation and translocation of photosynthetic products, thereby increasing yield [51]. This process is supported by nitrogen, an essential constituent of key photosynthetic components such as chlorophyll, proteins, and nucleic acids [52]. Furthermore, sufficient nitrogen supply promotes leaf expansion and enhances photosynthetic performance [48], while biochar application can improve canopy light penetration and thus enhance light energy utilization [53]. In contrast, high biochar-to-nitrogen ratio treatments in this study significantly reduced the Pn at the heading stage compared to the control group, with decreases ranging from 16.09% to 52.65%. We hypothesize that this suppression occurred because excessively high nitrogen levels can lead to excessive plant growth [54], resulting in dense foliage and poor light conditions within the canopy, thereby reducing Pn. This mechanism may also explain why the Pn of the control group was relatively high in our experiment.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that applying an appropriate proportion of straw biochar significantly enhances the efficiency of nitrogen fertilizer. The biochar-to-nitrogen combination exerts a significant impact on soil comprehensive indicators, biomass accumulation, and physiological properties of foxtail millet. In arid regions characterized by fragile ecosystems and low soil fertility, the combined application of straw biochar and nitrogen fertilizer is essential for harmonizing soil environmental sustainability with fertilization efficacy. The results showed that an optimal biochar-to-nitrogen fertilizer ratio promotes soil microbial activity and nutrient storage, enhances foxtail millet’s absorption of soil nutrients, stabilizes soil nitrogen transformation, and improves the output efficiency of photosynthetic products in aboveground organs, while maintaining a stable range of nitrogen fertilizer partial productivity. Consequently, the biochar-to-nitrogen combination facilitates the rational allocation of foxtail millet aboveground biomass. Through the strategic combination of straw biochar and nitrogen fertilizer, along with effective utilization of natural precipitation, foxtail millet yield increased by 32.09% to 110.57% over the two experimental years. Furthermore, this biochar and nitrogen application strategy avoids excessive nitrogen input in dryland millet cultivation systems while improving the soil carbon-nitrogen interaction mechanism, representing a reasonable approach that balances economic returns, resource use efficiency, and ecological benefits. This provides robust support for achieving the integrated goals of yield increase, quality improvement, and soil conservation in dryland agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: J.B., F.G., Q.J.; Investigation (Material preparation, data collection): J.B., F.G., Q.J.; Formal analysis (Data analysis): Z.C., J.B., F.G., Q.J.; Writing—original draft: Z.C.; Writing—review and editing: X.W., P.Z.; Supervision (Research guidance): X.W., X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers [41967013]); Industry-Academia Research Collaboration Project of Yulin Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant numbers [CXY-2022-70] and [2023-CXY-172]); Central Government Guidance Fund for the Local Science and Technology Development of Shaanxi Provincial Engineering Technology Research Center Project (Grant numbers [2022ZY2-GCZX-05]); National Natural Science Foundation of China Joint Fund Key Project (Grant number U25A20758). Grant 41967013 mainly supports biochar research and potential excavated, while grant U25A20758 focuses on soil microbiology analysis and identify.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be provided by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMBC | Soil microbial biomass carbon |

| SMBN | Soil microbial biomass nitrogen |

| Pn | Net photosynthesis rate |

| SPAD | Relative chlorophyll content |

| NUE | nitrogen use efficiency |

References

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Cui, S.; Jagadamma, S.; Zhang, Q. Residue retention and minimum tillage improve physical environment of the soil in croplands: A global meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wu, M.; Che, S.; Yuan, S.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Tian, P.; Wu, L.; Yang, M.; Wu, Z. Effects of continuous straw returning on soil functional microorganisms and microbial communities. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunchariyakun, K.; Sukmak, P.; Sukmak, G.; Phunpeng, V.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Arulrajah, A.; Zhou, A. Mechanical and microstructural properties of cement-stabilized soft clay improved by sand replacement and biochar additive for subgrade applications. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 20, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xing, B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Jiang, Z.; Deng, F.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. KOH-activated porous biochar with high specific surface area for adsorptive removal of chromium (VI) and naphthalene from water: Affecting factors, mechanisms and reusability exploration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, H.; Papari, S.; Lazarovits, G.; Berruti, F. Soil amendments for sustainable agriculture: Microbial organic fertilizers. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Guan, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B.; Ma, M.; Qin, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Shen, D. Influence of 34-years of fertilization on bacterial communities in an intensively cultivated black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.; Wu, R.; Selles, F.; Harker, K.; Clayton, G.; Bittman, S.; Zebarth, B.; Lupwayi, N. Crop yield and nitrogen concentration with controlled release urea and split applications of nitrogen as compared to non-coated urea applied at seeding. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-S.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z.-H. Effects of excessive nitrogen fertilization on soil organic carbon and nitrogen and nitrogen supply capacity in dryland. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2015, 21, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: Recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Searchinger, T.D.; Dumas, P.; Shen, Y. Managing nitrogen for sustainable development. Nature 2015, 528, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, S.; Banik, C.; Rathke, S.J.; Laird, D.A. Arsenic sorption on zero-valent iron-biochar complexes. Water Res. 2018, 137, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzediegwu, C.; Naeth, M.A.; Chang, S.X. Lead (II) adsorption on microwave-pyrolyzed biochars and hydrochars depends on feedstock type and production temperature. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Gao, F.; Mosa, A. Sorption of heavy metal ions onto crayfish shell biochar: Effect of pyrolysis temperature, pH and ionic strength. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Whalen, J.K.; Thomas, B.W.; Sachdeva, V.; Deng, H. Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: Mechanisms and future directions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 206, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Lin, C.L.; Zeng Jie, Z.J.; Xu DaPing, X.D.; Zhao ZhiGang, Z.Z.; Guo JunJie, G.J.; Lin KaiQin, L.K.; Sha Er, S.E. Effects of exponential nitrogen loading on growth and foliar nutrient status of Betula alnoides seedlings. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2010, 46, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, S.; Ahmed, S.; Joshi, S.J.; Sarma, H. Biochar as a Soil amendment: Implications for soil health, carbon sequestration, and climate resilience. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.-T.; Xing, G.-X.; Chen, X.-P.; Zhang, S.-L.; Zhang, L.-J.; Liu, X.-J.; Cui, Z.-L.; Yin, B.; Christie, P.; Zhu, Z.-L. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3041–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Han, W.; Zhang, W.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.; Vitousek, P.; Zhang, F. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P. Biochar, soil fertility, and environment. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 50, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, F.; Lu, S. The effects of manure and nitrogen fertilizer applications on soil organic carbon and nitrogen in a high-input cropping system. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Zhu, X.; Song, X. Beneficial effects of biochar application with nitrogen fertilizer on soil nitrogen retention, absorption and utilization in maize production. Agronomy 2022, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yang, L.; Qin, H.; Jiang, L.; Zou, Y. Fertilizer nitrogen uptake by rice increased by biochar application. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 50, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Xie, Y.; Hu, L.; Feng, B.; Li, S. Remobilization of vegetative nitrogen to developing grain in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Field Crops Res. 2016, 196, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, P.; Randall, P.; DeMarco, D. The response of dryland canola to nitrogen fertilizer: Partitioning and mobilization of dry matter and nitrogen, and nitrogen effects on yield components. Field Crops Res. 1997, 54, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-m.; Luo, W.-h.; Liu, P.-z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Li, J. Regulation effects of water saving and nitrogen reduction on dry matter and nitrogen accumulation, transportation and yield of summer maize. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2021, 54, 3183–3197. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.A.; Khan, K.S.; Khalid, R.; Shabaan, M.; Alghamdi, A.G.; Alasmary, Z.; Majrashi, M.A. Integrated application of biochar and chemical fertilizers improves wheat (Triticum aestivum) productivity by enhancing soil microbial activities. Plant Soil 2024, 502, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Ma, H.; Yan, W.; Shangguan, Z.; Zhong, Y. Effects of co-application of biochar and nitrogen fertilizer on soil profile carbon and nitrogen stocks and their fractions in wheat field. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Ren, W.; Tao, H.; Tao, B.; Lindsey, L.E. Impact of biochar amendment on soil microbial biomass carbon enhancement under field experiments: A meta-analysis. Biochar 2025, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejon, D.P.; Chaussod, R.; Ranger, J.; Ranjard, L. Microbial community structure and density under different tree species in an acid forest soil (Morvan, France). Microb. Ecol. 2005, 50, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghari, S.J.; Wahocho, N.A.; Laghari, G.M.; HafeezLaghari, A.; MustafaBhabhan, G.; HussainTalpur, K.; Bhutto, T.A.; Wahocho, S.A.; Lashari, A.A. Role of nitrogen for plant growth and development: A review. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016, 10, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-P.; Shao, M.-A.; Wang, Y.-Q. Spatial patterns of soil total nitrogen and soil total phosphorus across the entire Loess Plateau region of China. Geoderma 2013, 197, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-Z.; Pan, Y.-L.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Ao, G.-M.; Yu, J.-J. Culturing of immature inflorescences and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 16466–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Lu, H.; Chu, L.; Shao, H.; Shi, W. Biochar applied with appropriate rates can reduce N leaching, keep N retention and not increase NH3 volatilization in a coastal saline soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Herbert, S.; Xing, B. Impacts of adding biochar on nitrogen retention and bioavailability in agricultural soil. Geoderma 2013, 206, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chakraborty, D.; Garg, R.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, U. Effect of different water regimes and nitrogen application on growth, yield, water use and nitrogen uptake by pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 80, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-García, B.; Guillén, M.; Quílez, D. Response of paddy rice to fertilisation with pig slurry in northeast Spain: Strategies to optimise nitrogen use efficiency. Field Crops Res. 2017, 208, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Leghari, S.J.; Wu, J.; Wang, N.; Pang, M.; Jin, L. Interactive effects of biochar and chemical fertilizer on water and nitrogen dynamics, soil properties and maize yield under different irrigation methods. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1230023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Phan, B.T.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, V.N.; Van Tran, T.; Bach, Q.-V. Contrastive nutrient leaching from two differently textured paddy soils as influenced by biochar addition. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jílková, V.; Angst, G. Biochar and compost amendments to a coarse-textured temperate agricultural soil lead to nutrient leaching. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 173, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Bell, P.; Caldwell, D.; Habetz, B.; Rabb, J.; Alison, M. Nitrogen application and critical shoot nitrogen concentration for optimum grain and seed protein yield of pearl millet. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hussain, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, P.; Javed, T.; Dessoky, E.S.; Ren, X.; Chen, X. Effects of nitrogen application rate under straw incorporation on photosynthesis, productivity and nitrogen use efficiency in winter wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 862088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chang, X.; Li, J. Effects of Recommended Fertilizer Application Strategies Based on Yield Goal and Nutrient Requirements on Drip-Irrigated Spring Wheat Yield and Nutrient Uptake. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chi, Q.; Cai, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Müller, C. 15N tracing studies including plant N uptake processes provide new insights on gross N transformations in soil-plant systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 141, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.M.G.; Mota, M.F.C.; dos Santos Júnior, J.M.; Reis, M.M.; Frazão, L.A.; Fernandes, L.A. Biochar alters the soil microbiological activity of sugarcane fields over time. Sci. Agric. 2024, 81, e20230289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.N.; Xu, C.-Y.; Tahmasbian, I.; Che, R.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wallace, H.M.; Bai, S.H. Effects of biochar on soil available inorganic nitrogen: A review and meta-analysis. Geoderma 2017, 288, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Macko, S.A. Constrained Preferences in Nitrogen Uptake across Plant Species and Environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-H.; Xu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, L.-T. Effects of nitrogen deficiency on the photosynthesis, chlorophyll a fluorescence, antioxidant system, and sulfur compounds in Oryza sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Dolgikh, E.; Vikhnina, M.; Frolov, A.; Medvedev, S. Genetic and hormonal regulation of chlorophyll degradation during maturation of seeds with green embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Yang, D.S.; Li, X.X.; Peng, S.B.; Wang, F. Coordination of high grain yield and high nitrogen use efficiency through large sink size and high post-heading source capacity in rice. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.P. Photosynthesis engineered to increase rice yield. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohyama, T. Nitrogen as a major essential element of plants. Nitrogen Assim. Plants 2010, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Chang, T.; Shaghaleh, H.; Hamoud, Y.A. Improvement of photosynthesis by biochar and vermicompost to enhance tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) yield under greenhouse conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayissaa, T.; Kebedeb, F. Effect of nitrogenous fertilizer on the growth and yield of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) varieties in middle Awash, Ethiopia. J. Drylands 2011, 4, 248–258. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.