Abstract

Accurately estimating reference crop evapotranspiration (ET0) is essential for agricultural water-resource management, yet the traditional Penman–Monteith (PM) method requires multiple meteorological variables and is difficult to apply in data-sparse regions. To explore more data-efficient alternatives, this study systematically evaluates several machine-learning (ML) models capable of capturing nonlinear relationships, using daily observations from 698 meteorological stations across China. In addition, we incorporate SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP), a game-theory-based interpretability approach, to quantify the contribution of input variables at both national and regional scales. The results show that the Random Forest (RF) model performs best (coefficient of determination, R2 = 0.957; mean absolute percentage error, MAPE = 9.214%), significantly outperforming multiple linear regression and approaching the accuracy of the PM method. SHAP analysis indicates that maximum temperature, sunshine duration, and month are the most influential factors nationwide. Geographic variables contribute less overall but become important in specific regions, such as Southwest China. The study also reveals pronounced spatial heterogeneity in the drivers of ET0, highlighting the necessity of regionalized interpretations. Furthermore, sensor-reduction experiments demonstrate that reasonable estimation accuracy can be maintained even without radiation or wind-speed observations, offering guidance for low-cost monitoring scenarios. Overall, this study provides transparent model comparisons for ML-based ET0 estimation, uncovers regional differences in controlling factors, and offers practical insights for designing meteorological monitoring strategies in data-limited environments.

1. Introduction

Accurate estimation of reference crop evapotranspiration (ET0) is fundamental to efficient water resource management and the implementation of water-saving irrigation practices in agriculture [1]. As a key indicator of atmospheric evaporative demand, ET0 provides a scientific basis for determining crop water requirements and is widely used in irrigation system design, water allocation, and agro-meteorological services. Endorsed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as the standard method for estimating ET0, the Penman-Monteith (PM) model is widely recognized for its strong physical basis and high accuracy [2]. By integrating key meteorological factors such as air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation, the PM model exhibits strong universality and reliability. However, its requirement for multiple meteorological parameters necessitates a diverse array of sensors, leading to substantial equipment investment and maintenance costs, particularly in frontline agricultural production or remote areas. Consequently, the PM model is often impractical in data-scarce or cost-sensitive contexts, creating a demand for alternative methods with lower data requirements [3].

In contrast to traditional multi-parameter models, machine learning (ML) approaches can autonomously capture complex, nonlinear relationships within data without relying on rigid prior assumptions, often demonstrating superior performance in simulating intricate systems like ET0. With advancements in ML technology, algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are increasingly applied to ET0 estimation, frequently outperforming conventional empirical formulas. For instance, Santos et al. [4] evaluated different station zoning strategies and achieved high estimation accuracy using inputs including longitude, latitude, altitude, month, temperature, and humidity, offering valuable insights for regional water management in Brazil. Ayaz et al. [5] employed Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gradient Boosting, RF, and SVR models in Hyderabad, India, and Waipara, New Zealand, to explore ET0 estimation with limited meteorological data. Sammen et al. [6] compared various ML regression algorithms, including Support Vector Machine (SVM), RF, Bagged Trees, and Boosted Trees, for daily ET0 estimation in the semi-arid regions of Iraq. Sarkar et al. [7] evaluated the predictive capabilities of three deep learning sequence models-LSTM, Neural basis expansion analysis for interpretable time series forecasting (N-BEATS), and the Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)-for daily ET0. Acharki et al. [8] compared eight empirical formulas and four ML models (RF, M5′ model tree (M5P), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)) alongside their weighted ensembles, using Moroccan irrigation districts as a case study.

Recent progress in data-driven hydrological and land-surface modeling further demonstrates the growing capacity of ML to resolve complex environmental processes. Wei et al. [9] showed that sub-daily soil-moisture variations can be reconstructed from sparse measurements, while Chai et al. [10] highlighted vegetation-driven changes in terrestrial water loss that conventional models tend to underestimate. Lei et al. [11] applied interpretable Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models to hyperspectral data, illustrating how transparent ML frameworks can enhance physical understanding in Earth-system applications. In the field of ET0 estimation, a large number of studies have explored ML models under different climatic and data-availability conditions. Recent work has evaluated RF, SVR, ANN, boosted-tree models, LSTM-based deep learning, and hybrid or optimized ensemble methods using limited-input scenarios [4,12,13,14,15]. These studies collectively indicate that ML-based ET0 estimation is becoming increasingly robust across diverse regions, yet challenges remain regarding physical interpretability, cross-regional transferability, and realistic sensor configurations.

Despite these advancements, ML models face the challenge of “black-box” interpretability. While complex ensemble and deep learning models can achieve high predictive accuracy, it remains difficult to intuitively discern the physical influence of individual input features on specific predictions. As model complexity increases, so do the risks of overfitting and reduced interpretability. Traditional feature importance metrics (e.g., permutation importance) typically provide only a global ranking of features and fail to elucidate the direction and magnitude of each feature’s contribution to individual estimates. Therefore, enhancing model transparency and ensuring physical plausibility have become critical research priorities. To address this, researchers have introduced game theory-based explanation methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) [16]. By calculating the Shapley value for each input feature, SHAP decomposes a model’s prediction into a baseline value and the marginal contributions of individual features, enabling both global and local interpretation of the “black-box” model. Ravindran et al. [3] developed a single-parameter Deep Neural Network (DNN)model for ET0 prediction; using SHAP, they identified solar radiation as the most critical feature and demonstrated that the DNN model using only solar radiation achieved excellent performance (R2 = 0.92) across diverse climate zones. Sahoo et al. [17] constructed LSTM and XGBoost models and used SHAP to interpret the best-performing one, confirming solar radiation as the most influential factor and showing significantly better performance than traditional methods. Ahmed et al. [18] developed an interpretable ET prediction model, finding that XGBoost outperformed LSTM, with SHAP analysis confirming net radiation and air temperature as the primary driving variables. Although interpretable ML applications in agriculture are still emerging, existing results underscore its potential to help users understand model logic, validate physical consistency, and optimize decision support.

China’s vast territory encompasses diverse climate types, resulting in significant regional heterogeneity in the dominant drivers of ET0 [19,20]. Research shows that the multi-year average ET0 across most of China ranges between 800 mm and 1100 mm [21]. The highest values occur in the northwestern region, attributable to abundant sunshine, relatively high temperatures, and dry air, which collectively enhance evaporative potential. In contrast, the northeastern region exhibits the lowest ET0, due to lower temperatures and a shorter summer growing season. The North China Plain, situated in a temperate monsoon zone characterized by warm, humid summers and dry, cold winters, displays intermediate ET0 levels. Agriculturally, the northwest primarily engages in dryland and irrigation farming, the northeast focuses on crops like corn and soybeans, and the north employs a wheat-corn rotation system. Variations in irrigation practices and crop coefficients across these regions mean that the sensitivity of ET0 to different meteorological elements also varies spatially. For instance, temperature and sunshine duration may be the primary drivers in arid regions, whereas humidity or wind speed could be more influential in humid areas [22]. This regional heterogeneity necessitates separate analyses of variable importance for ET0 models across different climate zones to develop more accurate, localized estimation tools.

Addressing limitations in model interpretability, unclear sensor configurations, and the lack of cross-regional validation in existing studies, this work advances machine-learning-based ET0 estimation through the following innovations: (1) While previous SHAP-based ET0 studies have mostly focused on a single region or a limited number of stations, this study conducts a systematic interpretability analysis across multiple climate zones using large-scale, long-term observations covering diverse climatic regions of China, thereby extending the spatial scope and depth of regional comparison. (2) By applying SHAP to quantify the marginal contributions of meteorological variables and to reveal their differing roles across climate zones, the study enhances the physical interpretability of machine learning models. (3) A sensor-oriented variable simplification framework is proposed, which evaluates performance changes under various input combinations and provides more practical meteorological observation configurations for data-limited regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

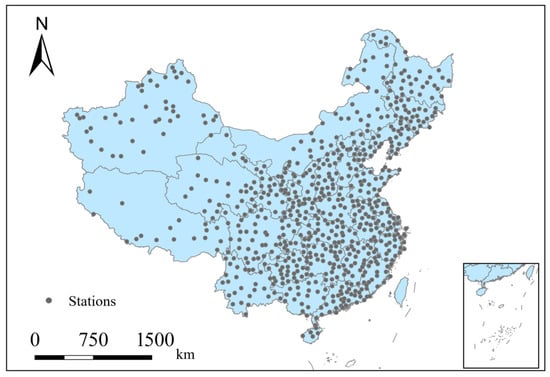

The meteorological data used in this study were obtained from the China Surface Climate Daily Value Dataset (V3.0) provided by the National Meteorological Information Center (NMIC, http://www.nmic.cn/) [23], which includes daily observational records from 698 national meteorological stations for the period 1960–2017. To investigate the spatial heterogeneity in the driving mechanisms of ET0, we adopted the geo-climatic zoning scheme proposed by Li et al. [24], dividing the country into seven regions as an analytical framework: Northeast China, North China, East China, South China, Central China, Northwest China, and Southwest China. This zoning aims to encompass the full climatic gradient of China—from humid monsoon regions to arid inland zones, and from lowland plains to the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau—thereby facilitating the comparison of the relative importance of dominant ET0 drivers under different climatic backgrounds, rather than serving as a formal climate classification based on algorithmic or Köppen criteria. Although this framework may not capture fine—scale climatic variations within each region, it provides a consistent basis for systematically examining large—scale spatial patterns in model performance and key meteorological controls. The geographical distribution of the meteorological stations is shown in Figure 1, ensuring comprehensive spatial coverage and reliable representation of spatiotemporal variability in ET0 across China. The input variables considered in this study included latitude (Lat), longitude (Lon), altitude (Alt), month (Month), daily mean temperature (Tavg), daily maximum temperature (Tmax), daily minimum temperature (Tmin), relative humidity (RH), mean wind speed (Wind), and sunshine duration (Sunhour). These variables were selected based on two primary considerations. First, they correspond to parameters required by the FAO-56 PM equation and are therefore physically relevant for determining reference crop evapotranspiration. Second, they represent meteorological elements that can be routinely measured by standard weather stations or low-cost sensor configurations commonly used in agricultural and environmental monitoring. The geographical variables were included to account for spatial gradients in radiation regimes, elevation-related atmospheric properties, and regional climatic differences.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of meteorological stations across China used in the present study.

2.2. FAO-56 Penman-Monteith Model

In this study, the ET0 values used as the target for model training and evaluation were calculated using the PM equation, which is internationally recognized as the standard method for ET0 estimation. The PM formulation is expressed as [25]:

where is the slope vapor curve (kPa °C−1); is the net radiation of the crop surface (MJ m−2 day−1); is the daily mean air temperature (°C); is the wind speed at 2 m height (m s−1); is the soil heat flux density (MJ m−2 day−1); is the saturation vapor (kPa); is the actual vapor pressure (kPa); and is the psychrometric constant (kPa °C−1).

All required components of the FAO-56 PM formulation—including net radiation (estimated from sunshine duration), saturation and actual vapor pressure, and the psychrometric constant (derived from elevation-based atmospheric pressure)—were calculated strictly following the FAO-56 recommended procedures. All meteorological variables used in the PM computation were obtained directly from the dataset described in Section 2.1. The resulting PM-based ET0 serves as the physical reference value that all machine-learning models aim to reproduce in this study.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

Prior to data analysis, quality control and unit conversion were applied to the raw meteorological observations. First, all fill values (32,766) were replaced with missing values (NaN), and records with missing data in ET0 or key meteorological variables were removed. ET0 ≤ 0 values were excluded to maintain consistency with the FAO-56 reference crop evapotranspiration framework and to ensure numerical stability during model training. Such values typically occur under conditions of extremely weak radiation or very low temperatures, where evaporation processes are minimal and ET0 estimates become highly sensitive to measurement noise. Although non-positive ET0 values may arise under specific physical conditions (e.g., frozen surfaces or condensation), they represent only a very small fraction of the dataset and were therefore not explicitly modeled in this study. After quality control, the dataset was randomly shuffled and split into training and testing subsets at a 4:1 ratio for model development and performance evaluation [26,27]. This partitioning is widely used in hydrological and meteorological machine-learning studies. It provides sufficient training data while ensuring that the test set remains large enough for stable assessment of generalization. Given the substantial size of the dataset in this study, this ratio offers an appropriate balance between model learning and independent validation. Because the objective of this study is to evaluate whether machine-learning models can provide reliable daily ET0 estimates across the full annual cycle while reducing dependence on multiple meteorological sensors, the analysis focuses on general daily-scale estimation rather than long-term forecasting. For this reason, a random split was adopted to ensure that the training set includes the full range of intra-annual meteorological variability. Consequently, model performance may reflect optimistic estimates of generalization under certain conditions, particularly in regions with strong temporal or spatial autocorrelation. Before model training, all continuous variables were standardized using Z-score normalization, as expressed in the following equation:

where is the standardized value, is the original value, represents the mean, and denotes the standard deviation of the dataset.

2.4. Shapely Additive Explanations (SHAP)

SHAP is a game-theory–based interpretability framework that decomposes a model prediction into the additive contributions of each input feature [28]. In this approach, features are treated as “players” in a cooperative game, and the model output is regarded as the “payout” to be fairly allocated among them according to the Shapley value.

In this study, SHAP analysis was conducted using the TreeExplainer implementation for the random forest model. For each sample I and feature , the Shapley value represents the marginal contribution of feature j to the prediction relative to a baseline. To quantify the overall influence of each feature, we computed the mean absolute Shapley value across all samples:

where is the SHAP value of feature j for sample I, and Importance (j) is the average absolute contribution across all samples.

This metric provides a model-agnostic estimate of global feature importance without applying any additional weighting scheme.

In addition to global importance, SHAP values enable examination of local, sample-specific contributions, as well as feature interactions through dependence plots. These visual tools help characterize nonlinear relationships captured by the machine-learning models and offer a unified interpretability framework applicable to complex ensemble algorithms [29]. As a model-agnostic interpretability approach, SHAP is designed to explain feature attributions within the trained model. When strong multicollinearity exists among input variables, SHAP values reflect how correlated predictors share explanatory power in the model, rather than indicating their independent physical effects. Accordingly, SHAP-based rankings provide valuable insight into model behavior but should not be directly interpreted as causal or standalone physical importance.

2.5. Machine Learning Models

In all machine-learning experiments, the PM-derived daily ET0 values obtained in Section 2.2 were used as the supervised learning target, with daily meteorological variables serving as predictors. To evaluate the ability of different algorithms to capture nonlinear meteorological–evaporative relationships, this study employed a diverse set of machine-learning models spanning linear and nonlinear structures, bagging and boosting ensembles, and Bayesian formulations. Hyperparameters for all machine-learning models were selected based on commonly adopted settings in ensemble learning and tree-based regression models. These values were fixed across all experiments to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Specific hyperparameter configurations for each model are provided in Supplementary Table S1. No exhaustive grid search or Bayesian optimization was conducted, as the focus of this study is on comparative model performance and interpretability rather than hyperparameter optimization. All analyses were performed in the Python 3.12.3 environment. Machine-learning models were implemented using scikit-learn (version 1.5.1), and bartpy (version 0.0.2). Model interpretability was conducted using the SHAP library (version 0.46.0).

2.5.1. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

MLR serves as a classical linear benchmark model and assumes an additive relationship between predictors and ET0 [30]. The model is expressed as:

where is the model output for sample , denotes the value of the j-th predictor variable for sample , a is the intercept, is the regression coefficient of predictor j, p is the number of support vectors, and is the random error term.

Parameters are estimated using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method, which yields the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator under classical assumptions. Because ET0 is driven by complex nonlinear interactions among meteorological variables, MLR is included primarily to quantify the improvement achieved by nonlinear machine-learning algorithms.

2.5.2. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR extends support vector machines to regression by searching for a function that deviates from the observed values by no more than an ε-insensitive margin [31]. The regression function can be written as:

where is the input vector for prediction, are the support vectors, is the kernel function, and are the Lagrange multipliers obtained from the dual optimization problem, l is the number of support vectors, and B is the bias term.

By using kernel functions such as linear, polynomial, or radial basis function (RBF): (1) SVR is well suited for capturing nonlinear relationships among meteorological variables and is known for strong generalization performance under limited samples and multicollinearity; (2) while maintaining strong generalization ability even when predictors exhibit multicollinearity. These properties have led to successful SVR applications in many hydrological and agro-meteorological studies.

2.5.3. Random Forest Regression (RF)

RF is a bagging-based ensemble model that constructs multiple decision trees using bootstrapped samples and randomly selected feature subsets. The final prediction is the average of all trees, providing strong robustness to noise and multicollinearity [32].

For the k-th feature, the variable importance measure (VIM) is obtained by quantifying the increase in out-of-bag (OOB) error after permuting that feature:

where is the original OOB error of tree , is the OOB error after permuting feature k, T is the number of support vectors, and SE denotes the standard error across trees.

RF is widely used in hydrological and environmental modeling because of its ability to capture nonlinear patterns and high-order interactions while requiring minimal parameter tuning.

2.5.4. Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT and hGBDT)

GBDT is a boosting framework that builds decision trees sequentially, where each new tree fits the negative gradient (pseudo-residuals) of the loss function from the previous iteration [33]. The model can be expressed as:

where is the updated ensemble model at iteration m, is the model from the previous iteration, is the regression tree added at iteration , is its optimal weight, and is the learning rate.

GBDT effectively reduces model bias and captures intricate variable interactions. The histogram-based variant (hGBDT) accelerates training for large datasets by using discretized feature histograms, making it computationally efficient for nationwide, multi-station ET0 datasets.

2.5.5. Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART)

BART represents the predictive function as a sum of many shallow Bayesian regression trees [34]:

where is the prediction of the j-th regression tree with structure and terminal-node parameters , m is the total number of trees in the ensemble, x is the input predictor vector, ε is the random error term, assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance , and denotes the model output.

The Bayesian regularization imposed on tree depth and terminal-node values enables BART to achieve flexible nonlinear fitting while reducing overfitting. In this study, BART is included as a Bayesian tree-based regression benchmark and is evaluated using point predictions to ensure consistency with other ensemble models. Although BART can be extended to provide full posterior predictive distributions, uncertainty quantification is beyond the scope of the present analysis and is not explored here.

2.5.6. Model Evaluation

For model performance evaluation, four widely adopted statistical metrics were employed as validation indicators: the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE).

R2: This metric quantifies the proportion of variance in observed data explained by the model. An R2 value approaching 1 indicates a strong linear relationship between predicted and actual values, implying that the model captures most of the data variability. Conversely, a value near 0 suggests poor model fit.

The formula for R2 is:

RMSE: This metric measures the average magnitude of prediction errors, with greater weight given to larger deviations due to the squaring operation. It quantifies the absolute difference between predicted and actual values:

MAE: Representing the average of absolute differences between predictions and observations, MAE provides an intuitive linear measure of average error magnitude:

MAPE: This metric expresses accuracy through the percentage of error relative to actual values, assessing relative prediction error:

where denotes the actual observed value, represents the model-predicted value, is the index of the forecast sample , and are the means of actual and predicted values, respectively, is the total number of samples in the test set.

All performance metrics reported in this study were computed using the held-out testing subset; for the Random Forest model, OOB error was used only as an internal training diagnostic and was not employed for model evaluation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Algorithm Accuracy Comparison

When model inputs comprised daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures, wind speed, relative humidity, month, longitude, latitude, altitude, and sunshine duration, the performance of each algorithm on the test set is summarized in Table 1. The results demonstrate that all machine learning models substantially outperformed the conventional MLR approach [35,36,37]. RF model achieved the most accurate performance, with R2 of 0.957, RMSE and MAE of 0.232 mm/d and 0.353 mm/d, respectively, and a MAPE of only 9.214%. These results indicate that the RF model effectively captures the nonlinear relationships between meteorological factors and evapotranspiration.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of machine learning models in daily precipitation prediction using R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE.

Compared with RF, the SVR and hGBDT models exhibited marginally lower but still competitive accuracy (R2 = 0.957 and 0.954; MAPE = 10.422% and 10.783%, respectively), confirming their strong applicability for ET0 estimation. Although the SVR model achieved a comparable R2 to RF, its computational efficiency was considerably lower, requiring several hours of training time versus only a few minutes for RF under identical data conditions.

The BART and GBDT models demonstrated moderate accuracy, with R2 values of 0.944 and 0.941, respectively, and MAPE approximating 13%. In contrast, the conventional MLR model showed the poorest performance, with an R2 of merely 0.818, significantly higher RMSE and MAE values, and a MAPE reaching 29.585%. This substantial performance gap underscores the limitation of linear methods in characterizing the complex nonlinear mechanisms governing ET0.

Considering both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, this study demonstrates the clear advantage of machine learning methods for ET0 estimation. Among the evaluated algorithms, the RF model exhibited the most balanced performance, thereby providing a robust foundation for subsequent SHAP-based interpretability analysis.

3.2. Interpretability Analysis of Machine Learning Models

To elucidate the decision-making process of machine learning models and identify the meteorological factors with the greatest contribution to ET0, this study applied the SHAP interpretability framework based on the optimal RF model [28]. SHAP values quantify feature importance by decomposing model predictions into baseline values and marginal contributions from each input variable. The mean absolute SHAP value serves as a robust indicator of a feature’s overall influence on model outputs, with larger values reflecting greater importance.

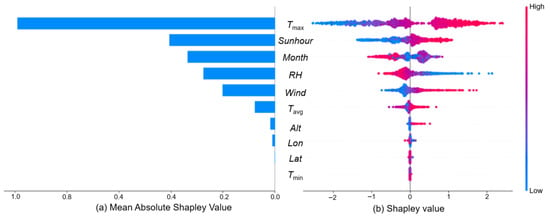

By computing mean absolute SHAP values across all 698 national meteorological stations, we established the global importance ranking of input features for ET0 estimation [38]. Figure 2a presents these values derived from the RF model, revealing the following influence hierarchy after weighted sorting: Tmax > Sunhour > Month > RH > Wind > Tavg > Alt > Lon > Lat > Tmin. Among these features, Tmax demonstrated the highest mean absolute SHAP value (approximately 0.98), establishing it as the most critical parameter—significantly outperforming other factors. This prominence reflects the dominant role of Tmax in the RF model, which is consistent with its well-established influence on saturation vapor pressure and vapor pressure deficit in physical evapotranspiration processes.

Figure 2.

Feature importance and SHAP value distribution for the Random Forest model. (a) Bar chart of mean absolute SHAP values indicating global feature importance across 698 meteorological stations; (b) SHAP summary (beeswarm) plot showing the distribution of Shapley values for each feature, where color represents the feature magnitude (blue = low, red = high).

Sunhour, serving as a proxy for solar radiation and closely correlated with net radiation, directly determines available energy for evapotranspiration, securing the second-highest importance [37]. Month, ranking third, primarily captures annual periodic variations-including solar altitude angle, day length, crop phenology, and seasonal climate patterns-thus reflecting combined seasonal and crop growth effects. RH and Wind showed moderate importance levels with SHAP values of approximately 0.20 and 0.09, respectively. Relative humidity modulates evaporative potential through atmospheric water vapor saturation deficit, while wind speed enhances turbulent exchange to promote evapotranspiration efficiency. Geographical parameters (Alt, Lon, Lat) and Tmin contributed minimally, indicating that dynamic meteorological factors possess substantially greater explanatory power than static spatial variables in daily-scale ET0 prediction. Because the temperature variables are strongly correlated, part of their explanatory power is redistributed among them, which leads SHAP to assign a larger marginal contribution to Tmax while giving a smaller share to Tmin. This statistical allocation reflects the behavior of Shapley values under correlated predictors [39] and does not imply a weak physical influence of Tmin. Geographical factors appear more suitable for characterizing spatial distribution patterns or regional zoning, while their marginal contributions remain limited in daily predictions. Accordingly, the SHAP-based importance ranking should be interpreted as a model-level explanation rather than a direct measure of independent physical dominance.

To further investigate feature impact patterns and their variations across individual samples, we generated SHAP summary plots (bee swarm plots) as shown in Figure 2b. These visualizations display SHAP value distributions at the sample level, revealing correspondences between feature values and their directional contributions to model outputs. Figure 2b demonstrates that Tmax exhibits the widest point cloud span, predominantly in the positive SHAP value region. Sunhour and Month also show generally positive influences, though less pronounced than Tmax. This pattern confirms that elevated temperatures and extended sunshine hours typically enhance ET0, while reduced values suppress it. Month displays distinct clustering, with data points for certain months concentrating in positive influence regions while others cluster in negative regions, validating its effectiveness as a seasonal variation proxy.

Notably, RH and Wind exhibit mixed positive-negative distributions, indicating context-dependent effects where influence direction reverses across different samples-suggesting significant feature interactions. This pattern implies that reduced atmospheric humidity (indicating drier conditions) intensifies evaporative demand, thereby driving ET0 increases. The embedded heatmap reveals that high ET0 events are frequently characterized by synergistic “high-temperature-strong radiation” modes, while compensatory effects among factors emerge in specific instances, demonstrating the model’s capacity to capture complex nonlinear relationships.

To further illustrate the nonlinear and coupled variable relationships that cannot be captured by the PM equation, the Supplementary Materials provide SHAP dependence plots for Tmax and Sunhour (Figures S1 and S2). The nationwide Tmax dependence plot reveals a clearly nonlinear contribution pattern: in the low-temperature range (Tmax < 0 °C), the contribution is negative and remains relatively stable; it increases rapidly within the 0–20 °C interval; and in the high-temperature range (>30 °C), the marginal effect gradually diminishes. Such threshold-type transitions and saturation behaviors are absent from the fixed linear or quasi-linear structure of the PM formulation. The dependence plot for Sunhour similarly exhibits a typical nonlinear radiation response: contributions are weak under low sunshine duration, rise sharply around 5–10 h, and then level off at higher durations. In addition, the color distribution of the points indicates a clear modulation effect of temperature on the radiation contribution-samples with higher temperatures show markedly larger SHAP values than low-temperature samples-demonstrating a synergistic interaction between temperature and radiation.

3.3. Regional Heterogeneity in Interpretability Analysis

Given the correlations among several meteorological variables, regional differences in SHAP rankings reflect relative changes in model attribution patterns rather than isolated physical drivers. Therefore, a spatially explicit SHAP analysis based on geographical zoning was conducted to explore regional heterogeneity in the dominant ET0-related driving mechanisms at the model attribution level. The numerical SHAP values supporting the regional importance rankings are provided in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials.

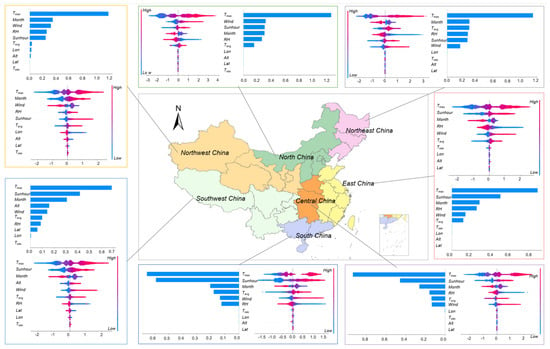

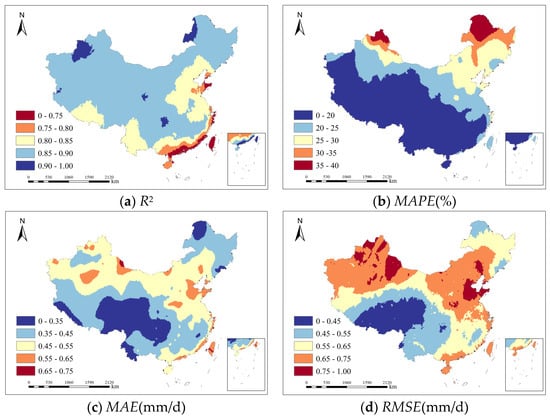

Northeast China—characterized by a cold-temperate and mid-temperate continental monsoon climate—exhibits the following feature importance ranking (Figure 3): Tmax > Month > Sunhour > RH > Wind > Tavg > Lon > Tmin > Lat > Alt. Consistent with the national model, Tmax remains the dominant factor, confirming its universal role as a key energy driver across climate zones. The prominence of Month (ranking second) reflects strong seasonal control, where high-latitude conditions create distinct seasons: prolonged cold winters with frozen ground versus short summers with intense evapotranspiration. The relative decline in Sunhour importance (third) may stem from comparatively lower variability in solar radiation during critical growing seasons. Longitudinal position surpasses latitudinal and altitudinal effects, capturing the climatic gradient from moist coastal areas to arid inland regions.

Figure 3.

Regional patterns of feature importance and SHAP-based variable effects across seven climatic zones in China.

North China—under a temperate monsoon climate—demonstrates a notable shift in feature importance. Wind emerges as the second most important driver, surpassing sunshine duration [40]. This pattern aligns with the region’s characteristic dry springs featuring frequent dust storms and high wind variability [41]. When energy supply (temperature, radiation) is sufficient, wind speed becomes the primary factor reducing aerodynamic resistance and enhancing turbulent exchange. Unlike Northeast China, seasonal freezing is less pronounced, and Month returns to fourth position.

East China—situated in a subtropical monsoon climate—shows a balanced, synergistic driver structure most closely resembling the national model. The consistent top-three ranking (Tmax, Sunhour, Month) suggests that in humid monsoon regions with concurrent heat and moisture availability, ET0 reverts to the classical radiation-driven paradigm. RH maintains stable fourth-place importance, where subtle fluctuations in already-high ambient humidity become relatively more significant in regulating vapor pressure deficit.

South China—encompassing tropical and subtropical monsoon climates—exhibits distinct adaptations to perpetually humid conditions. RH importance drops to sixth place, as near-saturation conditions minimize vapor pressure deficit variability. Conversely, Tavg rises to fourth position, far exceeding its ranking in other regions. The small diurnal temperature range means high Tavg indicates sustained favorable evapotranspiration conditions throughout day and night cycles [42].

Central China—a transitional zone between North and South China—displays driving factors highly consistent with the national model. Notably, the SHAP value distribution for relative humidity is almost entirely concentrated on the negative side, clearly indicating the dominant inhibitory effect of high humidity on ET0 in this region with distinct seasons and abundant precipitation.

Northwest China—characterized by a temperate continental arid/semi-arid climate—shows strong regional characteristics [43]. Month ranks second in importance, reflecting the sharp transition from frozen winters to irrigation-dependent growing seasons. Despite receiving the strongest solar radiation nationwide, Sunhour ranks only fifth, likely because abundant radiation is consistently available year-round, reducing its explanatory power for ET0 variation.

Southwest China—with complex plateau mountain and subtropical monsoon climates—exhibits the most unique driver structure. Alt emerges as the fourth most important factor, reflecting how topographic complexity creates contrasting microclimates where elevation directly modulates temperature and evapotranspiration potential. Meanwhile, relative RH drops to seventh, as highly variable terrain creates diverse microclimates that diminish its regional explanatory power.

3.4. Performance Evaluation of Simplified Meteorological Variable Combinations

Based on the preceding feature importance analysis, this study systematically evaluated model performance under progressively simplified input variable combinations [44]. Considering data acquisition constraints, variables were categorized by accessibility: temperature parameters are most readily available, followed by wind speed (derivable through empirical formulas if unmeasured), while sunshine duration and relative humidity present greater acquisition challenges. Among non-meteorological variables, temporal indicators (month) are easily obtainable, whereas spatial parameters (longitude, latitude, elevation) require specialized measurement.

A baseline model incorporating all candidate variables was established, alongside progressively simplified combinations designed through sequential variable reduction. All combinations were validated using an identical test set, with performance metrics detailed in Table 2. A detailed evaluation of the minimum and maximum ET0 values predicted by each combination is presented in Supplementary Table S3. All combinations produced ET0 ranges within climatologically reasonable limits, indicating that the RF models behave stably and do not generate physically implausible values [25,37]. The most simplified combinations (e.g., Combination 12) showed a reduced upper bound, which is consistent with the removal of key energy-related variables.

Table 2.

RF Model Performance with Different Input Sets.

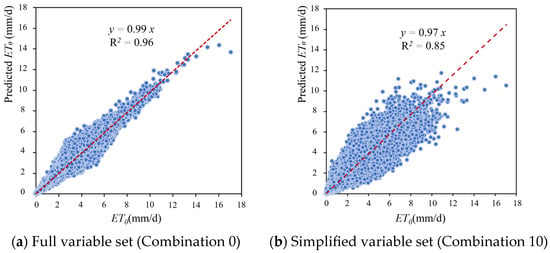

The results demonstrate a consistent pattern: as input variables decrease, model fit (R2) progressively declines while error metrics (MAE, RMSE, MAPE) correspondingly increase. This confirms the necessity of multidimensional meteorological information for accurate ET0 characterization. The full-variable combination (Combination 0) achieved optimal performance (R2 = 0.9707, MAE = 0.2130 mm/d, RMSE = 0.2920 mm/d), though its parameter requirements limit practical application under constrained observational conditions.

Notably, removing static spatial factors (Lon, Lat, Alt; Combination 1) induced negligible performance degradation (ΔR2 = −0.001, ΔMAE/RMSE < 0.005 mm/d), indicating their limited contribution to predictive accuracy at the national scale [45]. Elimination of Tmin and average Tavg (Combination 2) maintained high accuracy (R2 = 0.9698), suggesting effective energy representation by Tmax alone. Simultaneous removal of temperature extremes and spatial factors (Combination 3) caused modest performance decline (R2 = 0.9687), though remaining within acceptable error thresholds. Given the ready availability of spatial coordinates through modern geolocation services and temperature parameters through standard meteorological reports, we recommend retaining these variables for optimal accuracy.

Comparative analysis of Combinations 4–9 reveals distinct sensitivity patterns: individual removal of RH or Wind produced comparably minor impacts, whereas Sunhour elimination caused more pronounced effects. Concurrent removal of RH and Sunhour substantially degraded performance. For scenarios involving significant acquisition constraints for radiation/wind measurements, Combination 10 (retaining only temperature and humidity) achieved an effective balance between simplicity and performance (R2 = 0.8508, MAE = 0.4686 mm/d, RMSE = 0.6583 mm/d). This configuration eliminates requirements for specialized radiation/wind observation equipment while maintaining competent national-scale ET0 estimation capability. The robust performance of severely simplified combinations underscores the fundamental role of temperature in characterizing evaporative potential. In data-scarce regions or monitoring-constrained applications, Combination 10 offers substantial practical value. Thus, RF models utilizing minimal high-correlation meteorological factors can deliver efficient ET0 estimation while maintaining reasonable accuracy, providing simplified yet effective parameterization schemes for national-scale hydro-meteorological applications. Figure 4 illustrates correlation patterns between actual ET0 and predictions from Combination 0 versus Combination 10 models.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predicted versus observed ET0 using (a) the full variable set (Combination 0) and (b) the simplified variable set (Combination 10).

To complement the above performance evaluation, we further clarify the practical relevance of the simplified configurations. A qualitative comparison of typical sensor cost levels is provided in Supplementary Material Table S4. In general, radiation sensors tend to be more expensive and require periodic calibration, whereas temperature, humidity, and wind sensors are relatively low-cost and widely available in standard automatic weather stations. Therefore, relying solely on the combination of these typically measured variables 10 provides a low-cost alternative. Although its accuracy is lower than that of the full-input model, its performance remains acceptable for preliminary water-management applications in data-limited or budget-constrained environments, offering a practical compromise between measurement cost and estimation accuracy.

3.5. Regional Generalization Capacity Assessment

To evaluate the model’s generalization ability across different geographical regions, 20% of the samples from each meteorological station were randomly selected as a test set, and performance metrics were computed at the station level. It should be noted that this random selection approximates independence at the station level but does not fully ensure temporal or spatial independence. Therefore, the results provide an indicative assessment rather than a strict out-of-sample validation. Subsequently, to explore and visualize the nationwide spatial patterns of these station-level performance metrics, Ordinary Kriging interpolation was applied in ArcMap v10.8. This interpolation was used solely as an exploratory visualization tool and does not imply that the underlying performance metrics strictly satisfy spatial autocorrelation assumptions across all terrains [46].

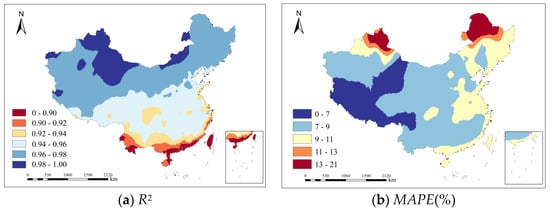

Figure 5 illustrates the generalization performance of the full-variable model (Combination 0). Spatial analysis reveals strong predictive accuracy (R2 > 0.94) across most inland regions, with comparatively diminished performance at coastal stations. Regarding relative error (MAPE), the model maintains high accuracy (MAPE < 11%) throughout most territories, except for certain high-latitude zones. Notably, coastal stations persist in exhibiting larger deviations. Absolute error metrics (MAE, RMSE) demonstrate coherent spatial patterns, with generally elevated values in southeastern China and reduced magnitudes in northwestern regions. These results indicate robust model applicability across most Chinese territories, with exceptions primarily limited to high-latitude (Northeast/Northwest) and coastal areas. Further analysis suggests that elevated MAPE in high-latitude regions may stem from the inherently low ET0 values in these zones, where even modest absolute errors generate large percentage deviations. The degraded coastal performance likely reflects fundamental differences in meteorological regimes-particularly humidity characteristics-between oceanic and continental climates.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of model performance metrics for the full-variable (Combination 0) ET0 prediction model on the test set.

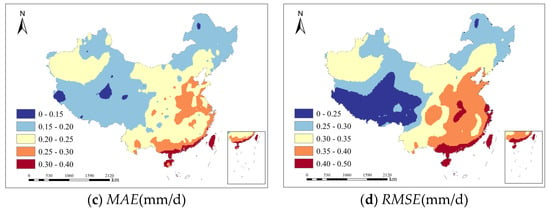

Figure 6 presents the corresponding analysis for the simplified model (Combination 10). This configuration maintains reasonable explanatory power (R2 > 0.8) across most regions, though with visibly reduced spatial consistency. MAPE values demonstrate clear latitudinal stratification, exceeding 20% in Northern, Northeastern, and Northwestern China. Absolute errors (MAE, RMSE) show amplified magnitudes in Northwest and North China, indicating particular sensitivity to the arid/semi-arid conditions prevalent in these regions.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of model performance metrics for the simplified-variable (Combination 10) ET0 prediction model on the test set.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the simplified model (Combination 10) exhibits substantially constrained generalization capacity and elevated error propagation across China’s diverse climates. Consequently, where observational capabilities permit, we recommend employing models with expanded variable inputs (e.g., Combination 6) to ensure robust performance across all geographical contexts.

4. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides a nationwide assessment of machine-learning-based ET0 estimation and sensor-simplification strategies, several limitations remain. First, strong correlations among temperature variables may influence the stability of SHAP importance rankings, particularly the relative redistribution of contributions among Tmin, Tavg, and Tmax. These interpretations should therefore be viewed with caution. Second, non-positive ET0 samples, although physically possible under specific conditions such as frozen or condensation-dominated surfaces, were excluded to maintain methodological consistency and model stability. This simplification may reduce the realism of ET0 representation in high-latitude or high-elevation regions, and future studies should explicitly assess model sensitivity to such conditions. Third, the random train–test split improves the representation of intra-annual variability but does not ensure temporal or spatial independence, potentially leading to an overestimation of true generalization ability. Furthermore, the use of Ordinary Kriging for visualizing spatial patterns assumes a degree of spatial continuity that may not hold in complex terrains like the Tibetan Plateau. To address these limitations, future work will adopt temporally and geographically independent validation schemes to better assess transferability and explore alternative interpolation approaches (e.g., incorporating elevation or non-stationary structures) for performance visualization. Fourth, despite the wide spatial coverage of the 698-station network, representativeness remains limited in areas with complex terrain, such as the Tibetan Plateau, where microclimates exhibit strong heterogeneity. Additional high-resolution observations would help improve model robustness in such regions. Finally, the simplified sensor configurations proposed here have not yet been tested in operational irrigation management, and their applicability under future climate or land-use changes remains uncertain. Field experiments and climate-scenario analyses will be valuable for assessing long-term reliability.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed multiple machine-learning approaches for estimating daily ET0 across China and examined their underlying mechanisms using SHAP interpretability analysis. Among the evaluated models, Random Forest provided the most reliable performance under full meteorological inputs, while other ensemble-based approaches also captured key nonlinearities in the ET0 process. SHAP analysis consistently identified maximum temperature, sunshine duration, and seasonal indicators as dominant national-scale drivers, and revealed region-specific patterns such as the enhanced influence of wind speed in northern China and elevation effects in the southwest. These results highlight the capacity of interpretable ML models to represent complex ET0 dynamics across diverse climatic settings. The variable-simplification experiment demonstrated that acceptable accuracy can still be achieved with reduced input sets, particularly those centered on temperature and humidity. This suggests that practical ET0 estimation in data-limited environments can be supported by prioritizing a small set of readily obtainable measurements, while full meteorological observations remain preferable when high precision is required. The interpretability results further offer guidance for sensor deployment strategies tailored to regional climatic conditions.

Future work should evaluate the proposed models under temporally and spatially independent validation schemes, expand testing in data-sparse mountainous regions, and examine model performance under projected climatic changes. Field-scale experiments and cost-related assessments will also be valuable for validating simplified sensor configurations in operational irrigation and water-management applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010093/s1, Figure S1: SHAP dependence plot of maximum temperature (Tmax); Figure S2: SHAP dependence plot of sunshine duration (Sunhour), colored by mean temperature (Tavg); Table S1: Hyperparameter settings adopted from established literature; Table S2: Regional SHAP Feature Importance Values for ET0 Estimation; Table S3: Predicted ET0 Ranges and Performance Metrics for Different Input Combinations; Table S4: Sensor types and typical cost levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and X.Y.; methodology, Q.Z., X.Y., C.L. and S.D.; software, Q.Z. and C.L.; validation, X.Y., C.D. and W.X.; formal analysis, X.Y.; investigation, S.D.; resources, C.L.; data curation, C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z., X.Y., C.L. and S.D.; visualization, W.X.; supervision, S.D.; project administration, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Project “Research on Citrus Irrigation Water Demand Prediction and Forecasting Based on 3S Technology” funded by the Chongqing Water Conservancy Science and Technology Program (CQSLK-2023021), and the Project “Key Technologies for Precise Water and Fertilizer Management of High-Quality Citrus under Rapid Drought–Flood Transition Conditions and Its Application” funded by the 2025 Chongqing Municipal Finance Special Core Technology Tackling Project (KYLX20250600325).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ET0 | Reference crop evapotranspiration |

| RF | Random forest |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression |

| ML | Machine learning |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

| PM | The Penman-Monteith |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| OLS | The ordinary least squares |

| TCN | The Temporal Convolutional Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| M5P | M5 Model Trees with Pruning |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| N-BEATS | Neural Basis Expansion Analysis for Interpretable Time Series Forecasting |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| OOB | The out-of-bag |

| VIM | The Variable Importance Measure |

| BART | Bayesian additive regression trees |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

References

- Reis, M.M.; da Silva, A.J.; Zullo Junior, J.; Tuffi Santos, L.D.; Azevedo, A.M.; Lopes, É.M.G. Empirical and Learning Machine Approaches to Estimating Reference Evapotranspiration Based on Temperature Data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 165, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Farias, D.B.; Althoff, D.; Rodrigues, L.N.; Filgueiras, R. Performance Evaluation of Numerical and Machine Learning Methods in Estimating Reference Evapotranspiration in a Brazilian Agricultural Frontier. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2020, 142, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, S.M.; Bhaskaran, S.K.M.; Ambat, S.K.N. A Deep Neural Network Architecture to Model Reference Evapotranspiration Using a Single Input Meteorological Parameter. Environ. Process. 2021, 8, 1567–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, P.A.B.; Schwerz, F.; de Carvalho, L.G.; Baptista, V.B.d.S.; Marin, D.B.; Ferraz, G.A.e.S.; Rossi, G.; Conti, L.; Bambi, G. Machine Learning and Conventional Methods for Reference Evapotranspiration Estimation Using Limited-Climatic-Data Scenarios. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, A.; Rajesh, M.; Singh, S.K.; Rehana, S.; Ayaz, A.; Rajesh, M.; Singh, S.K.; Rehana, S. Estimation of Reference Evapotranspiration Using Machine Learning Models with Limited Data. AIMS Geosci. 2021, 7, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammen, S.S.; Kisi, O.; Al-Janabi, A.; Elbeltagi, A.; Zounemat-Kermani, M. Estimation of Reference Evapotranspiration in Semi-Arid Region with Limited Climatic Inputs Using Metaheuristic Regression Methods. Water 2023, 15, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.S.; Bedi, J.; Jain, S. A Deep Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Reference Evapotranspiration Estimation: Evaluating Accuracy and Forecasting Strategies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharki, S.; Raza, A.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Amharref, M.; Bernoussi, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Al-Ansari, N.; Dewidar, A.Z.; Al-Othman, A.A.; Mattar, M.A. Comparative Assessment of Empirical and Hybrid Machine Learning Models for Estimating Daily Reference Evapotranspiration in Sub-Humid and Semi-Arid Climates. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Kou, J.; Miao, L.; Hu, F.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Meng, L. Exploring Diurnal Variation in Soil Moisture via Sub-Daily Estimates Reconstruction. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Miao, C.; Slater, L.; Ciais, P.; Berghuijs, W.R.; Chen, T.; Huntingford, C. Underestimating Global Land Greening: Future Vegetation Changes and Their Impacts on Terrestrial Water Loss. One Earth 2025, 8, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Bao, N.; Yu, M.; Cao, Y. Estimating and Mapping Tailings Properties of the Largest Iron Cluster in China for Resource Potential and Reuse: A New Perspective from Interpretable CNN Model and Proposed Spectral Index Based on Hyperspectral Satellite Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 139, 104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.L.S.; Ng, J.L.; Huang, Y.F.; Ang, C.K. Estimation of Reference Crop Evapotranspiration with Three Different Machine Learning Models and Limited Meteorological Variables. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, R.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Mao, H. Prediction of Reference Crop Evapotranspiration in China’s Climatic Regions Using Optimized Machine Learning Models. Water 2024, 16, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahudin, H.; Shoaib, M.; Albano, R.; Inam, M.A.; Hammad, M.; Raza, A.; Akhtar, A.; Ali, M. Using Ensembles of Machine Learning Techniques to Predict Reference Evapotranspiration (ET0) Using Limited Meteorological Data. Hydrology 2023, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiraga, S.; Peters, R.T.; Molaei, B.; Evett, S.R.; Marek, G. Reference Evapotranspiration Estimation Using Genetic Algorithm-Optimized Machine Learning Models and Standardized Penman–Monteith Equation in a Highly Advective Environment. Water 2024, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batunacun; Wieland, R.; Lakes, T.; Nendel, C. Using Shapley Additive Explanations to Interpret Extreme Gradient Boosting Predictions of Grassland Degradation in Xilingol, China. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 1493–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A. Predictive Modeling of Evapotranspiration Using Long Short-Term Memory and Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Adv. Mod. Agric. 2025, 6, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.M.; Deo, R.C.; Feng, Q.; Ghahramani, A.; Raj, N.; Yin, Z.; Yang, L. Hybrid Deep Learning Method for a Week-Ahead Evapotranspiration Forecasting. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yizhe, L.; Huiliang, W.; Xin, Z.; Chenhao, L.; Zihao, T.; Qiufen, Z.; Xizhi, L.; Tianling, Q. Spatiotemporal Variations and Driving Factors of Reference Evapotranspiration in the Yiluo River Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1048200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tong, L.; Guo, J.; Han, X.; Han, C. Heterogeneity Analysis of Main Driving Factors Affecting Potential Evapotranspiration Changes across Different Climate Regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 912, 168991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ti, J.; Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Liang, J.; Pu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wen, X.; Chen, F. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Meteorological Elements in the North China District of China during 1960–2015. Water 2018, 10, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Li, A.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal Changes and Driving Factors of Reference Evapotranspiration and Crop Evapotranspiration for Cotton Production in China from 1960 to 2019. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1251789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, S. Creation and Verification of a High-Resolution Multi-Parameter Surface Meteorological Assimilation Dataset for the Tibetan Plateau for 2010–2020 Available Online. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Borrelli, P.; Hubacek, K.; Hu, Y.; Xu, B.; Fang, N.; et al. Human-Altered Soil Loss Dominates Nearly Half of Water Erosion in China but Surges in Agriculture-Intensive Areas. One Earth 2024, 7, 2008–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.; Pereira, L.; Raes, D.; Smith, M.; Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Martin, S. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements, FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Imane, E.B.; Aicha, A.E.; Yassine, A.B.; Hicham, M.; Blaid, B. Future Groundwater Drought Analysis under Data Scarcity Using MedCORDEX Regional Climatic Models and Machine Learning: The Case of the Haouz Aquifer. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreido, V.; Gartsman, B.; Solomatine, D.P.; Suchilina, Z. How Well Can Machine Learning Models Perform without Hydrologists? Application of Rational Feature Selection to Improve Hydrological Forecasting. Water 2021, 13, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Feng, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, Q. Bridging the Gap: An Interpretable Coupled Model (SWAT-ELM-SHAP) for Blue-Green Water Simulation in Data-Scarce Basins. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A.S. Influential Observations, High Leverage Points, and Outliers in Linear Regression. Stat. Sci. 1986, 1, 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Smola, A.J.; Schölkopf, B. A Tutorial on Support Vector Regression. Stat. Comput. 2004, 14, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Statist. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Linero, A.; Murray, J. Bayesian Additive Regression Trees: A Review and Look Forward. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2020, 7, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Sun, S. Estimating Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Based on Limited Meteorological Data Using Deep Learning and Classical Machine Learning Methods. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591, 125286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, N.; Gong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L. Evaluation of Random Forests and Generalized Regression Neural Networks for Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Modelling. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 193, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yue, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Xiang, Y. Evaluation of SVM, ELM and Four Tree-Based Ensemble Models for Predicting Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Using Limited Meteorological Data in Different Climates of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 263, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, A.; Srivastava, A.; Cao, X.; Bilali, A.E.; Raza, A.; Khadke, L.; Salem, A. An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach Based on SHAP, Sobol and LIME Values for Precise Estimation of Daily Soybean Crop Coefficients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdinelli, I.; Wasserman, L. Feature Importance: A Closer Look at Shapley Values and LOCO. Stat. Sci. 2023, 39, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinde, A.T.; Emmanuel, I.; Enaboifo, M.A.; Ajayi, T.A.; Pham, Q.B. Spatio-Temporal Calibration of Hargreaves–Samani Model in the Northern Region of Nigeria. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 147, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, T.; Zhou, S.; Chang, F.; Shen, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. Interaction of Vegetation, Climate and Topography on Evapotranspiration Modelling at Different Time Scales within the Budyko Framework. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 275, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, W.; Shi, Z. Estimating Soil Bacterial Abundance and Diversity in the Southeast Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geoderma 2022, 416, 115807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Tian, S. A Novel Potential Cause of Extreme Precipitation in the Northwest China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Akhlaq, M.; Yan, H.; Ni, Y.; Liang, S.; Zhou, J.; Xue, R.; Li, M.; Adnan, R.M.; Li, J. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameter as a Predictor of Tomato Growth and Yield under CO2 Enrichment in Protective Cultivation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 284, 108333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Cao, J.; Xie, R.; Li, S. Integrating Satellite-Derived Climatic and Vegetation Indices to Predict Smallholder Maize Yield Using Deep Learning. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 311, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalder, I.A.; Wein, R.W. Spatial Interpolation of Climatic Normals: Test of a New Method in the Canadian Boreal Forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1998, 92, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.