Abstract

Soil salinization, characterized by complex ionic compositions, threatens global wheat production. Current research often focuses on single salts, leaving a gap in systematic comparisons of specific salt effects. This study comprehensively evaluated six prevalent salts (NaCl, Na2SO4, KCl, NaHCO3, MgSO4, and MgCl2) across concentrations (10–200 mmol/L) during wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germination. By integrating ten physiological indicators with principal component analysis (PCA), membership function evaluation, and median lethal concentration (LC50) calculation, we identified distinct salt-specific toxicities. Results established a clear toxicity hierarchy: MgCl2 was consistently most toxic (LC50 = 32.92 mmol/L), indicating Mg2+/Cl− synergy, while KCl was least inhibitory (LC50 = 159.66 mmol/L). PCA simplified the 10-trait dataset, extracting 1 principal component (PC, 89.29–92.35% contribution) for most salts (fresh weight as key loading, reflecting growth) and 2 PCs (95.65% cumulative contribution) for MgSO4 (separating root-growth and germination-vigor responses), thus identifying salt-specific key evaluation traits. Building on this PCA-derived trait screening, this analysis further revealed fresh weight (FW), germination rate (GR), shoot length (SL), and simple vigor index (SVI) as core evaluation indicators, and identified distinct mechanistic pathways: while most salts caused a generalized growth inhibition reflected in biomass reduction, MgCl2 exerted a more specific and severe inhibitory effect on shoot elongation. MgSO4 uniquely employed dual pathways, separately affecting root and germination traits. An innovative aspect of this work is the synergistic application of three synergistic evaluation methodologies with multi-physiological parameters, which allows for the rigorous quantitative characterization of distinct salt-specific effects on both early germination and seedling growth in wheat. This laboratory-based study provides a theoretical framework and practical indicators for salt damage risk assessment and preliminary screening of salt-tolerant wheat germplasm and lays a foundation for field validation and targeted management strategies for specific saline–alkali soils.

1. Introduction

Approximately 8 × 338 ha of arable land worldwide (accounting for about 6% of the total land area) has been affected by salinization [1]. This poses a severe challenge to the sustainability of crop production and global food security [2,3]. Salinization is driven by both natural factors (e.g., sea-level rise, increased evaporation intensity) and human activities (e.g., irrational irrigation, land use changes). It is particularly prominent in regions such as central California (USA) [4], western Australia [5], Pakistan [6], and the Yellow River Delta (China) [7,8].

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important staple foods globally, with an annual output of approximately 8.27 × 108 t [9], accounting for more than 20% of the world’s total cereal production [10]. Although wheat has higher salt tolerance than rice, it is still significantly lower than sorghum and barley [11,12]. Global wheat production is currently under severe threat from soil salinization [13]. Improving wheat salt tolerance has become a research focus for global food security. However, most current salt tolerance screening studies rely on single NaCl treatment, which cannot be directly extrapolated to the complex stress environment with multiple coexisting salts in actual saline–alkali soils [14,15]. Exploring the effects of different types of salt stress on plant growth is helpful for the screening of salt-tolerant crop varieties and the formulation of salt-tolerant cultivation strategies in different types of salinized areas.

Seed germination is the initial stage of the plant life cycle and is particularly sensitive to salt stress. Its performance directly determines plant morphogenesis and yield [16,17,18,19]. At present, studies on evaluating salt tolerance of wheat and other crops during the germination stage mostly focus on single-salt (NaCl) or simple mixed-salt (NaCl + Na2SO4) treatments [15,19,20,21,22,23]. In contrast, systematic single-salt comparison studies on multiple typical salts commonly present in global saline–alkali soils (e.g., NaCl, Na2SO4, KCl, NaHCO3, MgSO4, MgCl2) are relatively scarce. In maize, Kalhori et al. (2018) compared the effects of four salt types (NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, and MgSO4) on the germination and early growth of the MR219 variety [24]. In two important ethnomedicinal shrubs of North Africa and the Mediterranean basin (Ballota hirsuta and Myrtus communis), the effects of different chloride salts and sulfate salts on the seed germination and early seedling growth were evaluated [25]. However, similar research on wheat is still lacking. Furthermore, due to differences in the physicochemical properties and stress mechanisms of different salts, there are significant variations in their critical and LC50 ranges for inhibiting germination. Therefore, clarifying the LC50s of different salts is a primary prerequisite for constructing scientific stress gradients and achieving accurate phenotypic identification. Currently, a comprehensive and unified reference standard for such concentrations in wheat is less elucidated.

In the evaluation of salt tolerance during the germination stage, common morphological indicators including GR, germination energy (GE), germination index (GI), as well as seedling early growth parameters such as SL, root length (RL), total root number (TRN), stem width (SW), and FW has been well utilized in many plants [21]. Physiological indicators such as Soil Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) value (relative chlorophyll content) can indirectly reflect photosynthetic capacity [26,27]. However, a unified standard for the multi-indicator comprehensive evaluation system of wheat during the germination stage has not yet been well established. In particular, studies that combine morphological and physiological indicators and integrate quantitative models of principal component analysis (PCA), membership function, and LC50 calculation to adapt to the stress characteristics of different salts remain limited.

In this study, Yannong 301—a new winter wheat variety that is being widely promoted in northern China—was selected as the test material. Six types of single salts were treated independently (each salt was cultured separately) under five concentration gradients (10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 mmol/L), and ten key morphological and physiological indicators were systematically measured. Key salt tolerance factors were screened via PCA, and the membership function was used to quantitatively evaluate the comprehensive salt tolerance of different salts. Subsequently, quadratic curve regression was applied to calculate the LC50 of each salt.

Therefore, this study was designed to systematically accomplish three key tasks: (1) a comparative analysis of six predominant salts under single-salt gradient treatments; (2) a multi-dimensional assessment of ten physiological indicators; and (3) the construction of a comprehensive salt tolerance evaluation model by integrating PCA and membership function analysis, which provided a systematic quantification and direct comparison of the LC50 thresholds for all six salts. Our purpose is to provide a robust scientific basis for understanding the differential effects of various salts on wheat, to offer a standardized method for evaluating salt tolerance, and to generate highly comparable data that can be directly applied to wheat salt tolerance screening, salt damage risk assessment, and the breeding of salt-tolerant wheat varieties in global saline–alkali regions. The results provide highly comparable experimental references for wheat salt tolerance screening, salt damage risk assessment, and salt-tolerant variety breeding in global saline–alkali regions, and thus have significant reference value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Yannong 301, an elite winter wheat cultivar independently bred by our research team and newly granted official authorization, was selected as the experimental material. This cultivar features high yield and superior agronomic performance. Moreover, it exhibits remarkable salt tolerance in preliminary salinity identification assays [15]. It is currently being prioritized as a core cultivar for extension in saline–alkali soils.

Seeds of the Yannong 301 cultivar were provided by the Institute of Agricultural Biotechnology, Yantai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yantai, Shandong Province, China.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Salt Type and Concentration Setup

Six types of salts, namely KCl, NaCl, MgSO4, MgCl2, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4, (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) were selected for the experiment, as these salts cover the majority of ions present in saline soils. A total of five salt concentration gradients (0 (CK), 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 mmol/L) were set for each salt. All solutions were prepared with distilled water and sterilized before use. The 200 mmol/L concentration was designated as the upper limit, since most seeds failed to germinate or exhibited negligible post-germination growth across all six salt treatments at this concentration.

This experiment was conducted in 2024 at the Yantai Key Laboratory of Precise Evaluation and Molecular Breeding of Wheat Resources, Yantai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yantai, China (37.5° N, 121.29° E).

2.2.2. Germination Experiment

Plump, undamaged wheat seeds of uniform size were selected for the experiment. The seeds were rinsed with distilled water 2–3 times, then soaked in 1.50% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min for disinfection. After disinfection, the seeds were rinsed again with distilled water 3 times, and the surface moisture of the seeds was blotted dry with filter paper.

Subsequently, the wheat seeds were placed in Petri dishes with a diameter of 9 cm, each lined with two layers of filter paper. Thirty seeds were placed in each Petri dish, and each treatment was set with 3 replicates. Distilled water was used as the control treatment. Each Petri dish was added with 10 mL of distilled water or salt treatment solution, and the treatment solution was replaced daily starting from the 3rd day to maintain a consistent salt concentration and ensure sufficient moisture.

Germination was conducted in a walk-in climate chamber maintained at 23 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 2% relative humidity, under a 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod with a light intensity of 400 μmol·m−2·s−1.

2.2.3. Determination of Germination

Seeds were considered germinated when the plumule length exceeded 1/2 of the seed length, and the root length was equal to the seed length. The number of germinated seeds was counted daily. Germination energy (GE) was calculated as the percentage of the total number of germinated seeds on the 3rd day relative to the total number of seeds. Germination rate (GR) was calculated as the percentage of the total number of germinated seeds on the 7th day relative to the total number of seeds.

2.2.4. Determination of Growth

On the 7th day, we measured the following wheat growth indicators: shoot length (SL), root length (RL), total root number (TRN; considering roots longer than 50% of the seed length as effective), stem width (SW), fresh weight (FW), and SPAD value. SL, RL, and SW were measured using a millimeter-graduated ruler. FW was determined with a high-precision electronic analytical balance (0.0001 g; Shanghai Mettler-Toledo Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). SPAD values were obtained using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to measurement, the instrument was calibrated using the manufacturer’s standard reference plate. For each seedling, we took three readings from the central area of a fully expanded primary leaf, avoiding veins and edges, and used the mean value as the representative SPAD. All measurements were performed with five technical replicates per plant and three biological replicates.

2.2.5. Data Analysis

Microsoft Excel 2023 and SPSS Statistics 27 software were used for statistical analysis, including the calculation of mean values, salt tolerance coefficients, variances, and significance (ANOVA, t < 0.05), as well as multivariate analyses such as principal component analysis, membership function analysis, and stepwise regression. OriginPro 2025 software was used for visualization.

During the data analysis process, the value of each morphological indicator was first converted into the salt tolerance index of that indicator. The relevant calculation formulas are as follows:

where DG = daily germination count (mean number of germinated seeds per day); DT = corresponding daily germination days (mean number of days corresponding to each DG value); GR = mean germination rate; SL = mean shoot length; = mean germination rate under control treatment; = mean germination rate under salt treatment; Xij = principal component score of the j-th indicator under the i-th treatment; Xjmax = maximum principal component score of the j-th indicator; Xjmin = minimum principal component score of the j-th indicator. The RSIR algorithm refer to the method reported by Li et al. (2025) [28].

3. Results

Wheat exhibited diverse phenotypic changes under different salt types and concentrations (Figure 1). To further analyze these effects, we quantified germination parameters and traits of 7-day-old seedlings and calculated the median lethal concentration (LC50) for each salt type.

Figure 1.

Wheat phenotypes under different salt types and concentrations.

3.1. Germination Characteristics of Wheat Under Different Types of Salt Stress

To quantify how the timing and synchrony of wheat seed germination are modulated by salt type and concentration, a daily germination count was performed over seven days under salt stress.

Under salt treatments with concentrations of 50 mmol/L and lower, the germination peak of wheat seeds occurred on the 2nd day across all salt types, and the germination trends were relatively consistent (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Germination curves of wheat under different types of salt treatments.

At the concentration of 100 mmol/L, the germination peak of wheat seeds still appeared on the 2nd day under KCl, NaCl, and MgSO4 treatments. In contrast, under Na2SO4 treatment, the germination peak of wheat seeds was delayed until the 3rd day, with an additional germination peak observed on the 6th day. Only a few seeds germinated under NaHCO3 treatment. No seed germination was observed under MgCl2 treatment (Figure 2).

At the concentration of 200 mmol/L, the occurrence time of the germination peak was delayed for wheat seeds under KCl and NaCl treatments. Specifically, seeds germinated continuously under KCl treatment, reaching the germination peak on the 6th day, while no germination occurred in the early stage under NaCl treatment, with the germination peak appearing on the 6th day. No seed germination was observed under MgSO4, MgCl2, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4 treatments (Figure 2).

3.2. Effects of Different Types of Salt Stress on Wheat Germination Indicators

Based on the above data, germination indices were calculated to compare how different salt types and ionic compositions affect wheat germination and to rank their toxicity across concentrations.

With the increase in salt concentration, wheat GR and GE showed an overall decreasing trend (Figure 3A,B): GR and GE began to decrease relative to the control group at 200 mmol/L under KCl and NaCl treatments, at 100 mmol/L under MgSO4, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4 treatments (with GE specifically decreasing at 50 mmol/L under Na2SO4 treatment), and at 50 mmol/L under MgCl2 treatment. At 200 mmol/L, GR and GE decreased significantly under all salt treatments compared with the control—by 17.78% and 87.64% under KCl, 33.33% and 96.63% under NaCl, 97.78% and 97.75% under MgSO4, respectively—and no germination was observed under MgCl2, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4 treatments, indicating that high-concentration salt treatments strongly inhibit wheat seed germination.

Figure 3.

Germination indices of wheat under different types of salt treatments: germination rate (A); germination energy (B); relative salt injury rate (C); germination index (D); simple vigor index (E). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Among the salts tested at equal concentration, NaHCO3 and NaCl were, respectively, the strongest and weakest inhibitors of wheat germination for Na+-containing salts, whereas MgCl2 and KCl showed the same contrast for Cl−-containing salts. Overall, MgCl2 was the most inhibitory, and KCl the least.

At 10 mmol/L, the relative salt injury rate was 0 for all salt treatments except MgCl2, showing no impact on wheat germination (Figure 3C); at 200 mmol/L, the relative salt injury rate was 17.78% and 33.33% (slight impact) under KCl and NaCl, 97.78% (only a few seeds germinated) under MgSO4, and 100 (no germination) under MgCl2, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4. Using relative salt injury rate as the evaluation index, wheat salt tolerance followed the order KCl = NaCl = Na2SO4 > MgSO4 > NaHCO3 > MgCl2 under low-concentration treatments (10 and 25 mmol/L), NaCl = NaHCO3 > KCl > MgSO4 > Na2SO4 > MgCl2 under medium-concentration treatment (50 mmol/L), and KCl > NaCl > MgSO4 > Na2SO4 > NaHCO3 > MgCl2 under high-concentration treatments (100 and 200 mmol/L); the salt type to which wheat showed the strongest tolerance varied slightly across concentrations, but MgCl2 consistently remained the salt to which wheat was most sensitive (i.e., weakest tolerance).

3.3. Effects of Different Types of Salt Stress on Wheat Germination Index and Simple Vigor Index

To compare how different salts affect germination vigor and early seedling growth, GI and SVI were analyzed across salt types and concentrations.

Under various salt treatments, wheat GI and SVI both exhibited a concentration-dependent decrease (Figure 3D,E). The earlier decline in SVI compared to GI revealed that early seedling growth was more vulnerable to salt stress than germination. Specifically, GI suppression commenced at 50 mmol/L for MgCl2 and Na2SO4, highlighting their strong impact on germination vigor, whereas for NaCl, a notable decrease was only observed at 200 mmol/L, underscoring its minimal impact. For SVI, all salt treatments except KCl (which only affected wheat at 100 mmol/L) began to exert effects at 25 mmol/L, demonstrating that KCl had the smallest impact on wheat growth during the germination stage.

3.4. Effects of Different Types of Salt Stress on Wheat Growth Indicators

To dissect the dose- and ion-specific effects of salinity on early seedling vigor, we conducted a comprehensive growth-response analysis examining SL, RL, TRN, SW, biomass, and SPAD value across six salt types and four concentrations.

Wheat SL decreased progressively with increasing salt concentration (Figure 4A). At 100 mmol/L, SL was reduced by 32.12% and 44.82% under KCl and NaCl treatments, respectively, compared to the control. Under other salts, the reduction exceeded 80%, resulting in barely any seedling growth. At 200 mmol/L, reductions exceeded 90% under KCl, NaCl, and Na2SO4, with seedlings again showing negligible growth. No measurable shoot growth occurred under Na2SO4, NaHCO3, or MgCl2 at this concentration.

Figure 4.

Growth Parameters of wheat under different types of salt treatments: shoot length (A); root length (B); total root number (C); stem width (D); fresh weight (E); SPAD (F). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Under low-to-medium salt concentrations, MgCl2 exerted the strongest inhibitory effect on SL, with decreases of 35.20% (25 mmol/L) and 85.33% (50 mmol/L) vs. control; in contrast, SL increased by 11.03%, 14.98%, and 8.50% under KCl treatments at 10–50 mmol/L (vs. control), and by 7.15% (NaCl) and 9.93% (NaHCO3) at 10 mmol/L (vs. control), indicating a slight but non-significant promoting effect of these three salts on SL at low concentrations.

Similar to SL, wheat RL decreased with increasing salt concentration, but the inhibition was more severe for RL than for SL (Figure 4B). Furthermore, RL suppression occurred at lower concentrations. No growth promotion was observed at any concentration. Significant inhibition of RL was detected at 10 mmol/L for KCl, Na2SO4, MgCl2, and Na2SO4 (with reductions of 42.86%, 21.22%, 32.48%, and 24.30%, respectively), and at 25 mmol/L for NaCl and NaHCO3 (reductions of 22.23% and 66.21%). At 200 mmol/L, root growth was virtually absent under MgCl2, Na2SO4, and NaHCO3 treatments.

Salt treatments had a relatively minor impact on the TRN of wheat compared to other growth parameters (Figure 4C). Significant inhibition of TRN began at 10 mmol/L for MgSO4 and MgCl2, whereas for the other salts, significant reduction only occurred at 100 mmol/L or higher. The extent of inhibition on TRN by all salts increased gradually with concentration.

For other physiological parameters (SW, FW, and SPAD value), the inhibitory profiles varied (Figure 4D–F). MgCl2 exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect on both shoot weight (SW) and fresh weight (FW), whereas KCl showed the least. Significant inhibition of FW and SW by KCl was only detected at 100 mmol/L. In contrast, MgCl2 caused significant reductions at much lower concentrations: 10 mmol/L for FW and 25 mmol/L for SW. The other salts showed intermediate toxicity thresholds. For FW, significant inhibition occurred at 10 mmol/L for MgSO4, 25 mmol/L for NaHCO3 and Na2SO4, and 50 mmol/L for NaCl. For SW, the corresponding thresholds were higher: 50 mmol/L for NaHCO3 and Na2SO4, and 100 mmol/L for NaCl and MgSO4. Regarding the SPAD value, MgSO4 and MgCl2 exerted the strongest suppressive effect, while KCl and NaCl had the weakest. The concentration threshold for causing a significant reduction in SPAD value was 100 mmol/L for both KCl and NaCl. In contrast, a significant reduction was observed at a much lower concentration of 25 mmol/L for both MgSO4 and MgCl2. For NaHCO3 and Na2SO4, the threshold was intermediate at 50 mmol/L.

3.5. LC50s of Different Salt Stresses on Wheat During the Germination Stage

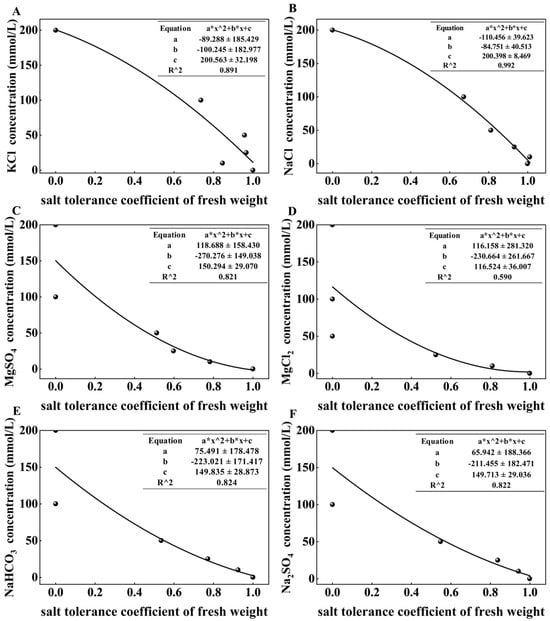

To quantify the intrinsic phytotoxicity of different salts and rank their toxicity, we performed a quadratic regression analysis to determine the LC50 values for key growth indicators, thereby providing a reference for selecting concentrations in follow-up studies. The analysis was based on regression models with the STC (from PCA) as the dependent variable and salt concentration as the independent variable, where a lower LC50 indicates greater sensitivity.

The results (Table 1) revealed distinct patterns from both indicator and salt perspectives. Among the indicators, SL was highly sensitive, with its LC50 below the average under all salt treatments except MgSO4. Similarly, the TRN and the SVI consistently exhibited LC50 values below the average across all treatments, confirming their roles as the most salt-sensitive indicators. In contrast, the LC50 for FW varied markedly depending on the salt type, highlighting the ion-specific nature of its impact on biomass accumulation.

Table 1.

Regression analysis of wheat salt tolerance coefficients (STCs) under different salt treatments.

The average LC50s values varied substantially among the salt treatments, revealing a clear phytotoxicity gradient. KCl and NaCl exhibited the highest LC50s values (both >100 mmol/L), indicating the lowest toxicity. In contrast, the average LC50s of MgSO4, MgCl2, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4 were all below 60 mmol/L, signifying a significantly stronger inhibitory effect on wheat germination. Among all salts, MgCl2 was the most toxic, as evidenced by its lowest average LC50s (32.92 mmol/L). This finding is consistent with the results of the relative salt injury rate analysis. Representative regression curves illustrating these relationships are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Relationship between STC and salt concentration in wheat. Regression curve for fresh weight: KCL (A); NaCl (B); MgSO4 (C); MgCl2 (D); NaHCO3 (E); Na2SO4 (F). In the formulas shown in each figure, the asterisk (*) denotes multiplication, and the caret followed by 2 (^2) indicates squaring (i.e., raising to the power of 2).

3.6. Principal Component Analysis

PCA was performed on the 10 wheat trait indicators to identify key dimensions summarizing salt-response patterns, using an eigenvalue > 1 as the extraction criterion (Table 2). The analysis revealed that the response to most salts (KCl, NaCl, NaHCO3, and Na2SO4) was captured by a single principal component, which was predominantly loaded with FW, explaining 89.565% to 92.350% of the variance. This indicates a consistent growth-inhibition response pattern. Divergent patterns were observed for magnesium salts. For MgCl2, the principal component was defined by SL and the simple vigor index SVI. In contrast, MgSO4 required two components, separating root-related traits (F1, 82.857%) from germination traits (F2, 12.795%), demonstrating a uniquely complex mechanism of action. TRN, reflecting growth-related traits, and the second principal component (F2) had a contribution rate of 12.795%, with the maximum load values for GR and GI, reflecting germination and seed vigor-related traits.

Table 2.

PCA of salt tolerance evaluation indexes.

3.7. Comprehensive Analysis Using Membership Function

To overcome the limitations of single-indicator evaluations, we employed membership function analysis to integrate multiple indicators for a more comprehensive and objective assessment of wheat salt tolerance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quantitative indices and comprehensive assessment of wheat salt tolerance under different salinity treatments.

The results demonstrated that the 10 mmol/L treatments of NaCl and NaHCO3 had a slight growth-promoting effect, ranking first and second, respectively, followed by the control (CK). All other treatments were inhibitory. The ranking of salt tolerance was concentration-dependent: at low concentrations (10, 25 mmol/L), the order was NaCl > KCl > NaHCO3 > Na2SO4 > MgSO4 > MgCl2; at medium concentration (50 mmol/L), it shifted to KCl > NaCl > MgSO4 > NaHCO3 > Na2SO4 > MgCl2; and at high concentrations (100, 200 mmol/L), it was KCl > NaCl > MgSO4 > Na2SO4 > NaHCO3 > MgCl2. Critically, this comprehensive evaluation corroborated the findings from the relative salt injury rate and LC50 analyses: while the most tolerated salt varied slightly with concentration, MgCl2 was consistently the most inhibitory.

4. Discussion

Salt stress is a key abiotic stress limiting plant growth, and its inhibitory degree is jointly regulated by plant species, developmental stage, salt concentration, and salt type [29,30]. Currently, significant progress has been made in research on salt tolerance of staple food crops such as wheat and rice [20,21,27,31,32,33], but most experiments only adopt a single NaCl treatment. Natural saline–alkali soils often contain multiple other salts such as Na2SO4, KCl, NaHCO3, MgSO4, and MgCl2 in addition to NaCl. Experiments with NaCl alone cannot fully reflect the actual stress scenario. Therefore, based on NaCl, this study added five typical salts (KCl, Na2SO4, NaHCO3, MgSO4, and MgCl2) to construct a multi-salt gradient treatment system, aiming to provide a scientific basis closer to the saline–alkali environment for analyzing wheat salt tolerance.

The germination stage is a key initial phase for wheat to successfully establish seedlings in saline–alkali soils. High-quality germination and early seedling growth directly determine the subsequent plant density and yield [34]. This stage is particularly sensitive to salt stress, often manifested as decreased vigor, reduced germination rate, and even seed inactivation under severe conditions [35,36]. In many coastal or inland saline–alkali areas, the multi-salt environment hinders wheat germination and seedling establishment, becoming a key bottleneck limiting the local wheat planting range and yield. Thus, conducting research on different salt stresses during the germination stage is a critical step for accurately evaluating wheat tolerance to various salts. The results of this study showed that all salt stresses reduced GE and GR, but the inhibitory degree varied with salt type. NaHCO3, MgCl2, and Na2SO4 exhibited the most prominent inhibitory effects, with almost complete seed inactivation at 200 mmol/L. In contrast, KCl and NaCl had milder inhibition at the same concentration, retaining approximately 60% germination rate at 200 mmol/L. This phenomenon is consistent with previous research conclusions [34], which can be attributed to the synergistic effect of osmotic stress and ion toxicity. Ions such as Na+, Cl−, and SO42− easily induce lipid peroxidation of the seed coat cell membrane, damage membrane structural integrity, and interfere with cell division and metabolism. Furthermore, SO42− can inhibit the uptake of other ions (e.g., Ca2+), leading to ionic imbalance [37,38]. Meanwhile, these ions reduce seed coat permeability, hindering water penetration into cotyledons and hypocotyls and thereby decreasing the germination rate [12,30,39,40].

Beyond these inhibitory effects at high concentrations, our study also revealed a biphasic response, where low concentrations of some salts could be stimulatory. Our results found that at low salt concentrations, certain salt treatments (e.g., NaCl and KCl) exerted a mild promotive effect on wheat germination and growth. This could be attributed to the fact that Na+ can partially substitute for K+ in mediating cellular osmotic adjustment at low levels, thereby reducing potassium consumption in wheat and conserving energy for growth and development [41]. In addition, an appropriate concentration of K+ can supplement potassium nutrition in wheat seedlings, which in turn accelerates plant height and biomass accumulation [42].

In the present study, the germination rate and germination energy of wheat seeds under the 200 mmol·L−1 KCl treatment decreased by 17.78% and 87.64%, respectively, compared with the control group, representing a considerable discrepancy. Given that germination energy reflects early germination dynamics and germination rate represents final germination capacity, this phenomenon might be explained by the acute inhibitory effect of excess Cl− on early seed germination, while the essential nutrient function of K+ partially alleviates the reduction in final germination rate [42].

Notably, MgCl2 had the strongest inhibitory effect on wheat germination. High concentrations of Mg2+ may competitively inhibit Ca2+ absorption, disrupting the Ca2+/Mg2+ balance in plants [43,44]. Additionally, the high Cl− content in MgCl2 further exacerbates cytotoxicity, leading to cell membrane damage and decreased seed coat permeability [40,43], forming a dual stress effect of “ion imbalance + membrane damage”. This result indicates that if the content of MgCl2 in saline–alkali soils is relatively high, it may cause more severe negative impacts on wheat sowing and seedling emergence, requiring focused monitoring and corresponding improvement measures before planting.

Regarding the early growth of seedlings after germination, the effects of different salts and concentrations also showed significant differences. Low-concentration treatments (10–50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L NaHCO3) had a slight promoting effect on wheat plant height (SL), which is consistent with previous reports [23]. At medium to high concentrations, the inhibitory effects of the six salts significantly intensified, and MgCl2 still had the strongest inhibitory effect—highly consistent with the results of the germination stage. This further confirms the strong stress characteristic of MgCl2 on wheat during the germination stage.

Combined with the actual conditions of saline–alkali areas, this finding can provide references for salt regulation during wheat sowing: if the proportion of low-concentration growth-promoting salts in the soil is high, their slight promoting effect can be moderately utilized; if the content of medium to high-concentration salts (especially MgCl2) is high, the salt content should be reduced through improvement measures before sowing to ensure the normal growth of seedlings.

Salt concentration selection is a core prerequisite for crop salt tolerance identification. The LC50 has been proven to be the optimal concentration basis for salt tolerance identification of crops such as soybean and wheat [44,45]. Through quadratic curve regression analysis, this study determined the LC50 values of the six salts for wheat during the germination stage, in the following order: KCl 159.66 mmol/L, NaCl 135.35 mmol/L, Na2SO4 55.95 mmol/L, MgSO4 52.36 mmol/L, NaHCO3 45.70 mmol/L, and MgCl2 32.92 mmol/L. Among these, the LC50 of plant height was lower than the average LC50 of each salt, suggesting that salt stress had a more significant impact on the early growth of wheat. The LC50 of NaCl (135.35 mmol/L) was similar to previous studies [44], while MgCl2 had the lowest LC50 and KCl/NaCl had the highest—directly confirming the conclusion from our results that KCl and NaCl had the weakest inhibitory effects on wheat during the germination stage, while MgCl2 had the strongest.

The above LC50 values can serve as threshold references for screening salt-tolerant wheat varieties in different saline–alkali areas. Screening varieties that can germinate normally under the corresponding salt concentration can effectively improve the adaptability of varieties to local soil salt conditions and alleviate the problem of “difficulty in growing wheat in saline–alkali soils”.

Salt tolerance is a complex quantitative trait jointly regulated by genetic and non-genetic factors, and a single indicator cannot accurately evaluate it. PCA and membership function methods are reliable stress resistance evaluation tools, which have been widely used in crops such as wheat and rice [15,21,32,46,47].

The PCA results of this study showed that FW, GR, SL, and SVI were the core indicators for evaluating wheat salt tolerance during the germination stage (with FW and GI making particularly prominent contributions), which is consistent with previous conclusions [15,46]. Subsequent comprehensive evaluation using the membership function further verified that 10 mmol/L NaCl and 10 mmol/L NaHCO3 had a slight promoting effect on wheat during the germination stage and early growth. Overall, NaCl and KCl had the weakest inhibitory effects, while MgCl2 had the strongest. This comprehensive evaluation result is well-aligned with the characteristics of multi-salt coexistence in saline–alkali areas. The screened core indicators have important reference significance for the rapid identification of salt-tolerant wheat varieties in saline–alkali soils, reducing screening costs, and improving breeding efficiency.

It is worth noting that this study only used a single wheat variety for the experiment. Varieties with different genetic backgrounds may exhibit differences in ion uptake and osmotic regulation. Therefore, for specific applications, it is recommended to conduct preliminary experiments and make slight optimizations based on the results of this study. Furthermore, the integrated salt tolerance evaluation method and the LC50-based analysis framework proposed herein could serve as a valuable reference for subsequent related experiments.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that different salts have distinct effects on wheat, challenging the idea of a universal “one-size-fits-all” salt stress. Through experiments with six salts, we confirmed that toxicity is ion-specific. We determined the unique LC50 (lethal concentration) for each salt, revealing MgCl2 as the most toxic and KCl as the least. Furthermore, we found that different salts damage wheat in different ways; for instance, MgCl2 primarily inhibits shoot growth, whereas MgSO4 independently impairs root development and germination. These findings confirm that salt stress mechanisms are dependent on specific ions. While our study was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, the methods and thresholds we established may serve as a valuable reference. The LC50 values proposed in this study could provide a reference and theoretical framework for selecting appropriate concentrations for evaluating wheat salt tolerance under different salt treatments. They could potentially assist in risk prediction for saline soils and inform the selection of wheat genotypes with enhanced tolerance for targeted breeding efforts.

For future work, we will verify the universality of these findings through parallel experiments with multiple varieties and carry out tests under field or semi-field conditions with in situ soil to evaluate the reliability of the laboratory results in practical applications. Meanwhile, we are conducting salt stress experiments covering the tillering, heading, and maturity stages, aiming to establish a comprehensive salt tolerance evaluation system from the germination stage to the whole growth period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D. and X.S.; methodology, J.W. and Y.W.; software, J.W., Y.W. and X.H.; validation, X.Y.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, J.W., X.D. and H.Y.; resources, X.S. and Y.Y.; data curation, J.W. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and X.D.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., Y.Y. and J.Z.; visualization, J.W. and X.D.; supervision, X.S. and T.Y.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Biological Breeding—National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2023ZD04026); the Key Research and Development Project of Shandong Province (the Agricultural Variety Improvement Project) (Grant No. 2023LZGC002); Yantai Science and Technology Development Program (Grant No. 2024ZDCX022); Institute of Hefei Artificial Intelligence Breeding Accelerator Co., Ltd. (Grant No. GS2025ZX007); National Key Laboratory of Wheat Improvement (Grant No. WIKF202411); and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. ZR2025MS472).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GE | Germination Energy |

| GR | Germination Rate |

| TRN | Total Root Number |

| RL | Root Length |

| SL | Shoot Length |

| SW | Stem Width |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

| GI | Germination Index |

| SVI | Simple Vigor Index |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| LC50 | Median Lethal Concentration |

| SPAD | Soil Plant Analysis Development |

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Tian, C.; Mai, W. Progress of Euhalophyte Adaptation to Arid Areas to Remediate Salinized Soil. Agriculture 2023, 13, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xia, G. The landscape of molecular mechanisms for salt tolerance in wheat. Crop J. 2018, 6, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, K.; Wick, A.F.; DeSutter, T.; Chatterjee, A.; Harmon, J. Soil Salinity: A Threat to Global Food Security. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 2189–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gies, E. In California, salt taints soil, threatening food security. Environmental Health News, 27 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, D.J.; George, R.J.; Caccetta, P.A. The extent and potential area of salt-affected land in Western Australia estimated using remote sensing and digital terrain models. In Proceedings of the 1st National Salinity Engineering Conference, Perth, Australia, 9–12 November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Improving Salinity and Agricultural Water Management in the Indus Basin, Pakistan: Issues, Management and Opportunities: A Synthesis from a Desk-Top Literature Review; February 2018 (republished August 2023); Gulbali Institute, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2023; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Gao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Guo, X.; Lv, Q.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Meng, Q. Biochar improves soil quality and wheat yield in saline-alkali soils beyond organic fertilizer in a 3-year field trial. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 19097–19110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Huang, L. Detection of soil salinity distribution and its change in the Yellow River Delta comparing 2006 and 2022. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 4288–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). World Food Situation: FAO Cereal Supply and Demand Brief; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/csdb/en/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Arzani, A.; Ashraf, M. Cultivated Ancient Wheats (Triticum spp.): A Potential Source of Health-Beneficial Food Products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharabsheh, H.M.; Seleiman, M.F.; Hewedy, O.A.; Battaglia, M.L.; Jalal, R.S.; Alhammad, B.A.; Schillaci, C.; Ali, N.; Al-Doss, A. Field Crop Responses and Management Strategies to Mitigate Soil Salinity in Modern Agriculture: A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.-K.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of Plant Responses and Adaptation to Soil Salinity. Innovation 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, J.; Qin, L.; Shi, W.; Xia, G.; Liu, S. TaCYP81D5, one member in a wheat cytochrome P450 gene cluster, confers salinity tolerance via reactive oxygen species scavenging. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 18, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghhenabi, F.; Hadi, H.; Khodaverdiloo, H.; van Genuchten, M.T. Seed priming alleviated salinity stress during germination and emergence of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Weng, X.; Jiang, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, K.; Li, K.; Guo, X.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, G. Screening and Evaluation of Salt-Tolerant Wheat Germplasm Based on the Main Morphological Indices at the Germination and Seedling Stages. Plants 2024, 13, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.K.; Ali, A.S.; Hasan, H.H.; Ghal, R.H. Salt Tolerance Study of Six Cultivars of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) During Germination and Early Seedling Growth. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardarin, A.; Coste, F.; Wagner, M.-H.; Dürr, C. How do seed and seedling traits influence germination and emergence parameters in crop species? A comparative analysis. Seed Sci. Res. 2016, 26, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, M.J.; Sweat, J.K. Germination, Emergence, and Seedling Establishment of Buffalo Gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima). Weed Sci. 2017, 42, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiremit, M.S.; Arslan, H.; Sezer, İ.; Akay, H. Evaluating and Modeling of the Seedling Growth Ability of Wheat Seeds as Affected by Shallow-Saline Groundwater Conditions. Gesunde Pflanz. 2022, 74, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Huang, X.; Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ai, X.; Wang, Y. Salt tolerance evaluation and key salt-tolerant traits at germination stage of upland cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1489380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ge, L.; Fei, L.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, L. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Soybean Germplasm Resources for Salt Tolerance During Germination. Plants 2025, 14, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xiang, L.; Lei, Z.; Huang, Q.; Li, T.; Shen, F.; Cheng, Q. A Salt Tolerance Evaluation Method for Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) at the Seed Germination Stage. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, B. An Effective Screening Method and a Reliable Screening Trait for Salt Tolerance of Brassica napus at the Germination Stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhori, N.; Ying, T.; Nulit, R.; Sahebi, M.; Abiri, R.; Atabaki, N. Effect of Four Different Salts on Seed Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Oryza sativa L. cv. MR219. Int. J. Adv. Res. Bot. 2018, 4, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadach, M.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Bhatt, A.; Radicetti, E.; Mancinelli, R. Effects of Chloride and Sulfate Salts on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Ballota hirsuta Benth. and Myrtus communis L. Plants 2023, 12, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Li, W.; Hu, P.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, Q.; Li, H.; Li, Z. An Integrated Method for Evaluation of Salt Tolerance in a Tall Wheatgrass Breeding Program. Plants 2025, 14, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ashkar, I.; Alderfasi, A.; Ben Romdhane, W.; Seleiman, M.F.; El-Said, R.A.; Al-Doss, A. Morphological and Genetic Diversity within Salt Tolerance Detection in Eighteen Wheat Genotypes. Plants 2020, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Han, X.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Y. Comparative Analysis of Salt Tolerance and Transcriptomics in Two Varieties of Agropyron desertorum at Different Developmental Stages. Genes 2025, 16, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Sarkhosh, A.; Khan, N.; Balal, R.M.; Ali, S.; Rossi, L.; Gómez, C.; Mattson, N.; Nasim, W.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Insights into the Physiological and Biochemical Impacts of Salt Stress on Plant Growth and Development. Agronomy 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wang, G.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guan, C.; Luo, Z.B. Assessing alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) tolerance to salinity at seedling stage and screening of the salinity tolerance traits. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunthaburee, S.; Dongsansuk, A.; Sanitchon, J.; Pattanagul, W.; Theerakulpisut, P. Physiological and biochemical parameters for evaluation and clustering of rice cultivars differing in salt tolerance at seedling stage. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 23, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.u.D.; Masarmi, A.G.; Solouki, M.; Fakheri, B.; Kalaji, H.M.; Mahgdingad, N.; Golkari, S.; Telesiński, A.; Lamlom, S.F.; Kociel, H.; et al. Comparing the salinity tolerance of twenty different wheat genotypes on the basis of their physiological and biochemical parameters under NaCl stress. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.E.H.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, G.; Nimir, N.E.A. Comparison of Germination and Seedling Characteristics of Wheat Varieties from China and Sudan under Salt Stress. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, T.J.; Munns, R.; Colmer, T.D. Sodium chloride toxicity and the cellular basis of salt tolerance in halophytes. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeh-Hosseini, M.; Powell, A.A.; Bingham, I.J. The interaction between salinity stress and seed vigour during germination of soyabean seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2003, 31, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Rahman, A.; Anee, T.I.; Alam, M.U.; Bhuiyan, T.F.; Oku, H.; Fujita, M. Approaches to Enhance Salt Stress Tolerance in Wheat. In Wheat Improvement, Management and Utilization; InTech: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 2017, 217, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant salt response: Perception, signaling, and tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1053699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. The regulation of plant cell wall organisation under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornburg, T.E.; Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Xue, H.; Wang, G.; Li, L.; Fontana, J.E.; Davis, K.E.; Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; et al. Potassium Deficiency Significantly Affected Plant Growth and Development as Well as microRNA-Mediated Mechanism in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almodares, A.; Hadi, M.R.; Dosti, B. Effects of Salt Stress on Germination Percentage and Seedling Growth in Sweet Sorghum Cultivars. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 7, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Kaur, N.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, A. Evaluation and screening of elite wheat germplasm for salinity stress at the seedling phase. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyanagoudar, H.S.; Hatiya, S.T.; Guhey, A.; Dharmappa, P.M.; Seetharamaiah, S.K. A comprehensive approach for evaluating salinity stress tolerance in brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) germplasm using membership function value. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.-X.; Bai, R.; Nan, M.; Ren, W.; Wang, C.-M.; Shabala, S.; Zhang, J.-L. Evaluation of salt tolerance of oat cultivars and the mechanism of adaptation to salinity. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 273, 153708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baksh, S.K.Y.; Donde, R.; Kumar, J.; Mukherjee, M.; Meher, J.; Behera, L.; Dash, S.K. Genetic relationship, population structure analysis and pheno-molecular characterization of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars for bacterial leaf blight resistance and submergence tolerance using trait specific STS markers. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.