Abstract

A method for quantifying tebufenpyrad residues in greenhouse sandy loam soils was developed and validated. Given the strong sorption (high Koc) of tebufenpyrad to mineral–organic domains in soils, desorption-limited and partially bound residues may occur, so sample preparation methods should actively promote desorption to minimize underestimation. The QuEChERS extraction procedure was optimized by adjusting pre-wetting volume and aqueous medium to enhance desorption prior to salt-induced acetonitrile partitioning. Pre-wetting volume markedly affected phase separation and recovery: acceptable ranges were 80.2–82.0% at 5–10 mL, 94.6% at 15 mL, and 99.1% at 20 mL, while a supra-quantitative value of 119.6% was observed at 25 mL, likely due to salt-induced contraction of the acetonitrile layer, which artificially concentrates tebufenpyrad. Among pre-wetting reagents, 15 mL of 0.05% HCl yielded the highest desorption in field soil (0.20 mg/kg), compared with distilled water (0.13 mg/kg), formic acid (0.16 mg/kg), and EDTA (0.14–0.17 mg/kg). The final method employed 15 mL of 0.05% HCl for pre-wetting, followed by acetonitrile extraction and MgSO4/NaCl partitioning. Linearity (r2 = 0.9990) was achieved over 1.25 to 100 ng/mL, with an LOQ of 0.005 mg/kg and average recoveries of 86.7%, 99.8%, and 98.5% at 0.01, 0.1, and 30 mg/kg, respectively (RSD ≤ 6.2%), satisfying SANTE criteria. In greenhouse soil, residues declined from 1.9 to 0.3 mg/kg at the recommended rate (1×) and from 4.8 to 0.7 mg/kg at the doubled rate (2×) within 46 d (DT50 ≈ 20 d). This validated QuEChERS method provides a reliable analytical basis for evaluating tebufenpyrad dissipation in soil.

1. Introduction

Agricultural soils are widely recognized as the primary receiving, storage, and transformation compartment for pesticides, governing persistence, mobility, and bioavailability across the landscape [1]. This central role is reflected in regulatory guidance that requires dedicated soil-transformation studies (OECD Test Guideline 307) to inform exposure assessment, since residue behavior in soil drives predicted environmental concentrations and soil-organism risk evaluations [2]. An EU-wide survey of 317 agricultural topsoils detected pesticide residues in 83% of samples; mixtures of two or more residues were present in 58%, indicating that multiresidue contamination is common across European farmland [3]. Global assessments likewise document widespread accumulation of agrochemical residues in soils and other ecosystems [4]. Collectively, these findings underscore why characterizing residue dissipation in soil is foundational to both dietary and environmental exposure evaluations [5].

Once in soil, pesticides are rapidly partitioned to mineral and organic components, where multiple sorption mechanisms operate. The extent and reversibility of this association depend on both soil properties (e.g., texture, organic carbon, mineral oxides) and pesticide chemistry [6]. Over time, “aging” processes strengthen these associations and give rise to non-extractable (bound) residues, rendering a growing fraction less recoverable by mild solvents and lowering apparent bioavailability: these behaviors have been synthesized in the classic review by Gevao et al. (2000), which details how soil–pesticide interactions evolve and why extraction yield and biological availability can diverge in field-aged matrices [7]. In greenhouse soils, exposure to weathering processes such as solar radiation and atmospheric exchange is reduced compared with open-field conditions [8]. Under these conditions, pesticide residues can persist for longer periods, allowing sorbed fractions to age and become increasingly non-extractable [7]. Consequently, desorption-promoting steps are particularly important when developing soil residue methods for greenhouse systems.

Various extraction techniques have been employed for pesticide-residue analysis in soils, including Soxhlet extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasonic solvent extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, solid-phase extraction, solid-phase microextraction, matrix solid-phase dispersion, and accelerated solvent extraction [9]. However, these conventional methods are often labor-intensive, require large solvent volumes, and generate substantial waste [9,10]. In contrast, the Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) approach has emerged as a simpler and greener alternative that provides high-throughput multiresidue capability [11]. Initially developed for fruits and vegetables, this method has been successfully adapted for complex soil matrices [12]. It combines acetonitrile extraction and salt-induced partitioning with dispersive solid-phase clean-up to achieve efficient recovery.

In line with the sorption-and-aging considerations, desorption-promoting pretreatments immediately prior to QuEChERS partitioning have been shown to be useful. Mild acids help control pH and protonate surface sites, while chelating agents sequester exchangeable cations that bridge pesticides to mineral surfaces, both actions favoring release into the extracting phase [13]. Contemporary soil methods commonly pre-hydrate the sample with water and employ acidified conditions during extraction (e.g., acetonitrile with formic or acetic acid) to stabilize phase separation and improve recoveries, as summarized in a recent methodological review and demonstrated in applied studies on soils [14,15]. Moreover, adding EDTA to the QuEChERS workflow has been shown to enhance desorption and improve recoveries for several currently used pesticides in soil, achieving low-nanograms per gram LOQs [16]. In soils, iron and aluminum oxides strongly interact with organic matter to form mineral–organic complexes that provide abundant sorption sites for pesticides. Such mixed domains can immobilize organic contaminants through ligand exchange and electrostatic interactions, leading to reduced extractability [17]. Acid treatment has been shown to induce cationic hydrolysis of amorphous ferrihydrite and disrupt Fe-bound domains, thereby facilitating the separation and removal of associated contaminants from soils [18]. Previous QuEChERS-based soil studies, however, have seldom addressed desorption limitations in aged soils or systematically compared the combined effects of pre-wetting volume and acid/chelation chemistry. Because sorption and desorption behavior depends on soil texture, organic matter, and climatic conditions (e.g., temperature and moisture regimes), extraction protocols need to be designed with desorption processes in mind if they are to be adapted reliably to different soils [19,20]. Collectively, these observations underscore the need for a desorption-oriented extraction strategy that explicitly targets sorbed and aged residue fractions.

Given the structural similarity between metal–ligand and pesticide–oxide complexes, hydrochloric acid is expected to disrupt these Fe-bridged networks in soil, facilitating the release of pesticide residues from mineral surfaces. Accordingly, this study evaluates dilute mineral acid and EDTA solutions as aqueous pre-wetting media prior to salt-induced acetonitrile partitioning, as well as to validate the resulting procedure in accordance with regulatory performance criteria [9].

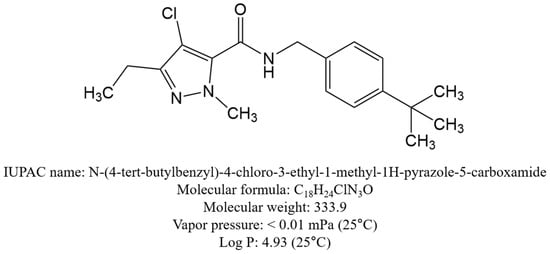

Tebufenpyrad (Figure 1), chemically designated as N-[(4-tert-butylphenyl)methyl]-4-chloro-5-ethyl-2-methylpyrazole-3-carboxamide, is a pyrazole-carboxamide acaricide widely used in commercial greenhouse production for controlling mites and ticks on ornamental and horticultural crops. It belongs to the mitochondrial electron transport inhibitors (METI) classified by the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC, Group 21A) and acts by binding to mitochondrial complex I, thereby interrupting electron flow and ATP synthesis. This ultimately leads to cellular energy depletion and organismal death [21,22]. Beyond its pesticidal activity, in vitro studies have demonstrated that tebufenpyrad rapidly induces mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and bioenergetic collapse in dopaminergic neuronal cells, underscoring a potential to impair mitochondrial integrity beyond target pests [23]. Based on the Stockholm Convention Annex D screening thresholds for persistence (e.g., a soil/sediment half-life of 180 d), tebufenpyrad does not meet the persistence criterion for POP screening [24,25]. From an ecotoxicological perspective, however, it is reported to be highly toxic to fish; Ayari et al. (2022) reported acute and teratogenic effects in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae, with 96 h LC50 values of 25.7 mg/L and concentration-dependent developmental malformations, including pericardial and yolk edema [26].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and physicochemical properties of tebufenpyrad.

Therefore, this study aimed to establish an optimized extraction and analytical procedure for accurately quantifying tebufenpyrad residues in soil, focusing on how pre-wetting volume and the use of acidic or chelating reagents influence desorption efficiency and phase behavior during QuEChERS extraction. The optimized condition was subsequently validated and applied to evaluate the dissipation kinetics of tebufenpyrad under greenhouse soil conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Tebufenpyrad reference material (99.59% purity) was obtained from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsburg, Germany). A commercial 10% emulsifiable concentrate (EC) of tebufenpyrad (Piranika; Syngenta Korea Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea) was procured. HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from Duksan Reagents (Ansan, Republic of Korea). LC–MS-grade methanol and formic acid (FA, 99.0+%) were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), and LC–MS-grade water was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Inorganic salts for extraction and partitioning consisted of anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, ≥ 99%; Daejung Chemicals & Metals, Siheung, Republic of Korea) and sodium chloride (NaCl, ≥ 99.5%; Junsei Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 98.5–102.0%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 35–37%; Samchun Chemicals, Seoul, Republic of Korea) were purchased from the indicated suppliers.

2.2. Greenhouse Field Trial and Soil Sampling

A residue field trial was conducted in a greenhouse in Sancheong, Republic of Korea (35°17′03.8″ N, 127°54′53.0″ E). Treatment plots measured 3 m2 and contained three replicate subplots of 1 m2 each. Tebufenpyrad 10% EC was diluted with water to prepare spray solutions at 2000-fold (1× label rate; recommended) and 1000-fold (2× label rate; doubled) and uniformly applied to the soil surface at 1 L/m2 using a watering can. Soil samples were collected at 0 d (3 h after application) and at 2, 4, 8, 16, 25, 32, 39, and 46 d after application, with triplicate sampling on each date. For each 1 m2 subplot, one surface soil core was collected from 0 to 10 cm depth using a stainless-steel scoop after removing coarse debris, resulting in three independent replicates per treatment. Over the course of the greenhouse trial (27 August–12 October 2024), temperatures ranged from 17.7 to 35.5 °C and relative humidity from 48.6 to 95.0%. During the dissipation trial, irrigation was supplied through a ground-level hose system that wetted only the soil surface, maintaining typical greenhouse moisture conditions. Immediately after collection, soils were sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove debris and coarse aggregates, shade-dried at room temperature for approximately 48 h, and stored at −20 °C until analysis. The greenhouse soil was collected from an actively cultivated plot primarily used for various leafy vegetables, with a history of pesticide applications; however, no residues of the target pesticide were detected in any soil sample before the start of the trial. For site characterization, a composite soil sample from the experimental plot was submitted to the Korea Society of Forest Environment Research (KSFER, Namyangju, Republic of Korea) for routine analysis of texture class, pH, total nitrogen, and exchangeable potassium (K+) (Table 1). According to the USDA soil texture classification system (USDA Soil Texture Triangle), the experimental soil (49.4% sand, 37.8% silt, 12.8% clay) is classified as sandy loam [27].

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the experimental sandy loam soil.

2.3. Preparation of Working Standards and Calibration Solutions

Purity-corrected primary stock solutions of tebufenpyrad were prepared at 1000 mg/L in acetonitrile. Serial dilutions in acetonitrile yielded working standards at 10,000, 5000, 1000, 200, 100, 50, 25, 10, 5, and 2.5 ng/mL. A pesticide-free blank soil sample was extracted using the final optimized preparation. The resulting blank extract was mixed (1:1, v/v) with solvent-based working standards to prepare matrix-matched calibration solutions, yielding final concentrations of 1.25–100 ng/mL (0.005–0.40 mg/kgsoil). Stock, working, and matrix-matched standard solutions were stored at −20 °C in amber glass and brought to room temperature immediately before use.

2.4. LC–MS/MS Analysis

Quantitative analysis of tebufenpyrad was performed on a Shimadzu LCMS-8040 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Nexera UHPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A Halo C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 µm; Advanced Materials Technology, Wilmington, DE, USA) was maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phases were 0.1% (v/v) FA in water (A) and 0.1% (v/v) FA in methanol (B). The flow rate was held at 0.2 mL/min, and the injection volume was 5 µL. At the start of each run (0–0.2 min), the composition was held at 30% B. It was then increased linearly to 85% B by 0.5 min and further to 98% B by 6 min. The system was held at 98% B from 6 to 9 min, then returned to 30% B at 9 min and was re-equilibrated at 30% B until 12.5 min. The flow rate was maintained at 0.2 mL/min, and tebufenpyrad eluted at approximately 4.5 min.

The mass spectrometer was operated in electrospray positive ion mode. Interface parameters were as follows: desolvation line (DL) temperature, 250 °C; heat-block temperature, 400 °C; nebulizing gas flow, 3 L/min; drying gas flow, 15 L/min; and argon (≥99.999%) as the collision gas. Multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) was used for acquisition with the following transitions for tebufenpyrad (precursor m/z 334.4): quantifier, 334.4 → 117.1, and qualifier, 334.4 → 147.2 with collision energies of −39 and −27 V, respectively. Data were collected and processed using Shimadzu LabSolutions software (version 5.120).

2.5. Evaluation of Soil Extraction Preparation

Blank soil test portions (5 g) were fortified to 0.05 mg/kg tebufenpyrad by adding 50 µL of a 5000 ng/mL working standard and gently mixing to distribute the spike. To examine the effect of pre-wetting, aliquots of distilled water (DW; 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 25 mL) were added to separate tubes, which were shaken at 800 rpm for 10 min. Acetonitrile (10 mL) was then introduced, and shaking continued at 800 rpm for 10 min. QuEChERS partitioning salts (4.0 g MgSO4 and 1.0 g NaCl) were added in a single portion, the tubes were shaken again at 1300 rpm for 2 min, and the extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 5 min. An aliquot of the supernatant (300 µL) was combined 1:1 (v/v) with acetonitrile (300 µL) prior to LC–MS/MS, and recoveries were calculated against matrix-matched calibration.

In the second series, the same fortification level (0.05 mg/kg) was used to compare extraction efficiency among aqueous pre-wetting modifiers. Test portions received either 10 or 15 mL of one of the following solutions: FA (0.05% or 1%), EDTA (0.01 M or 0.1 M), or HCl (0.05%). Extraction, partitioning, and matrix-matching were performed as described above, and recoveries and matrix effects were determined.

To evaluate desorption efficiency in field-treated soil, subsamples from different post-application days were pooled to obtain a representative field-aged matrix and to compensate for limited material on some days, and this experiment focused on evaluating average desorption behavior rather than day-specific dissipation patterns. Aliquots (5 g) of the soil were contacted with 15 mL of each aqueous medium (DW; FA 0.05% or 1%; EDTA 0.01 M or 0.1 M; HCl 0.05%), followed by the same preparation described above. The detected amounts of tebufenpyrad in each sample were compared across treatments to evaluate the extent of desorption in the actual samples.

2.6. Established Sample Preparation

Homogenized soil test portions (5 g) were weighed into 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes. An aqueous pre-wetting solution of hydrochloric acid (0.05% in DW, 15 mL) was added, and the tubes were shaken at 800 rpm for 10 min on a 1600 MiniG shaker (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA). Acetonitrile (10 mL) was then added, and shaking was continued at 800 rpm for 10 min. QuEChERS partitioning salts—anhydrous MgSO4 (4.0 g) and NaCl (1.0 g)—were introduced in a single portion, the tubes were shaken at 1300 rpm for 2 min, and the mixtures were clarified by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 5 min using a LABOGENE 1248 centrifuge (Allerød, Denmark). An aliquot of the upper acetonitrile layer (300 µL) was mixed 1:1 (v/v) with acetonitrile (300 µL) for matrix-matching prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

2.7. Analytical Method Validation

The limit of quantitation (LOQ) was established as the lowest concentration that produced a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) exceeding 10 in the chromatogram for the quantifier transition [28]. LOQ was verified in the matrix by injecting low-level matrix-matched standards prepared. Linearity was evaluated using matrix-matched calibration solutions spanning 1.25 to 100 ng/mL. Calibration curves were constructed by linear regression (y = ax + b), and linearity was confirmed by correlation coefficient (r2) values.

Apparent recovery and precision were determined at three fortification levels by spiking blank soil (5 g per replicate; n = 3 at each level), followed by the established extraction and partitioning procedure and matrix-matched quantitation. For the low and mid levels, 0.01 mg/kg was obtained by adding 50 µL of a 1 mg/L standard solution, and 0.1 mg/kg by adding 50 µL of a 10 mg/L standard solution to 5 g of blank soil. For the high level (30 mg/kg), 150 µL of a 1000 mg/L stock solution was added to 5 g of blank soil; the resulting extract was diluted appropriately with blank matrix extract and acetonitrile to fall within the validated calibration range prior to quantitation. Recoveries were calculated from the measured amounts relative to the nominal spike, and precision was expressed as the relative standard deviation across replicates. Additional QA/QC measures, including procedural blanks, calibration verification, retention-time checks, and carryover tests, were implemented throughout the workflow to ensure analytical reliability. Matrix effects were estimated by comparing the slopes of calibration curves prepared in matrix and in solvent, as shown in Equation (1):

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and figure generation were performed in R (version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using RStudio (version 2025.05.1). For each response variable, distributional assumptions were evaluated on model residuals: normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances with Levene’s test. Treatment means were compared by one-way ANOVA; when the omnibus F-test was significant at α = 0.05, pairwise differences were resolved with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) procedure. A t-test was also used where appropriate (α = 0.05). Where relevant in figures, compact letter displays are shown above the plots to denote groups that do not differ significantly.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Pre-Wetting Volume on QuEChERS Extraction from Soil

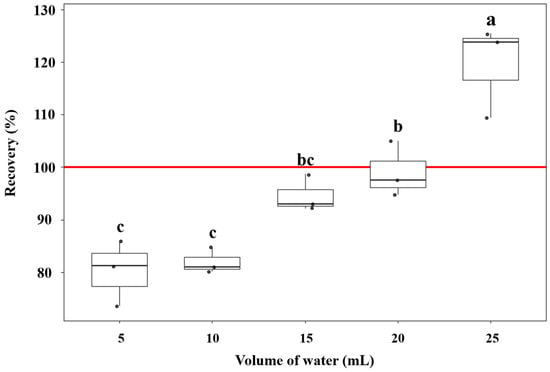

Pre-wetting strongly governed both phase disengagement during QuEChERS partitioning and the measured recovery of tebufenpyrad. When only 2.5 mL of water was added to 5 g of soil, the salt-induced liquid–liquid separation after addition of acetonitrile and MgSO4/NaCl was unstable and incomplete; this condition was therefore not pursued for quantitative comparison. Under the same extraction scheme, recoveries at 5 and 10 mL pre-wetting clustered near 80.2–82.0% and formed the lowest statistical group (Figure 2), indicating that insufficient hydration limited both desorption from soil aggregates and the efficiency of salting-out of the analyte into the acetonitrile layer. Consistent with prior multiresidue evaluations on clay–loam soils, recoveries for tebufenpyrad and many co-analytes were low when no water was added or when soil moisture was minimal and increased as pre-wetting rose to roughly 10–50% [29]. This literature data corroborates our interpretation that inadequate hydration impairs extraction efficiency during salting-out in sandy loam soils.

Figure 2.

Effect of pre-wetting volume on the recovery of tebufenpyrad from soil using the QuEChERS extraction. Different letters (a–c) indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD (p < 0.05). Values represent means of triplicate analyses (n = 3).

Increasing the pre-wetting volume to 15–20 mL produced clear and reproducible phase disengagement and yielded recoveries of 94.6% (15 mL) and 99.1% (20 mL), both close to 100%. Box-and-whisker groupings (letters above the boxes) showed that 15 mL (“bc”) and 20 mL (“b”) were significantly higher than 5–10 mL (“c”), supporting the interpretation that a moderate increase in water promotes analyte desorption and, upon salt addition, drives a more effective salting-out of tebufenpyrad into the organic phase. In addition, using 5 g of soil provided adequate recoveries and reproducibility, indicating that reducing the sample amount did not adversely affect extraction performance in this matrix. In line with this trend, previous optimization work showed that pre-wetting with ≥ 10 mL of water (per 5 g soil) yielded cleaner extracts and ~20% higher signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) than 2 mL [30]. Pre-wetting is considered essential for QuEChERS in low-moisture soils because the original method assumes high-moisture matrices; hydrating the soil maximizes extraction efficiency and helps buffer the heat released by MgSO4 hydration, protecting heat-labile analytes [12].

At 25 mL, apparent recovery rose to 119.6% and formed the highest group (“a”). This inflation is consistent with contraction of the acetonitrile-rich phase during salt-induced liquid–liquid partitioning (SALLE) under a large aqueous load—reducing the final organic-phase volume and concentrating the analyte relative to the nominal 10 mL extract—an effect expected from the phase behavior of water–acetonitrile–salt systems (lever-rule analysis) [31]. The matrix effect was +5.8% in this volume, a level generally regarded as negligible and thus insufficient to account for the > 100% positive bias. Because quantitation was matrix-matched, ionization enhancement alone is unlikely to explain the discrepancy; rather, phase-volume contraction causes overestimation when extract volume is assumed rather than measured, so 25 mL risks biased quantitation despite high absolute signal. Collectively, these results indicate that 15–20 mL of pre-wetting water provides the optimal balance between efficient soil wetting/desorption and unbiased phase volumes for QuEChERS in this matrix.

3.2. Effect of Acidic and Chelating Pre-Wetting Media

Acidic or chelating (EDTA) pre-wetting was used to promote desorption by protonating anionic sites, enhancing salting-out/stability in the solvent, and sequestering soil metals that otherwise mediate sorption. These mechanisms and extraction gains have been reported previously for QuEChERS-type soil analyses [16,32]. Guided by these findings, FA, EDTA, and HCl were selected as representative reagents [16,32,33] and were evaluated at varying concentrations in the pre-wetting step.

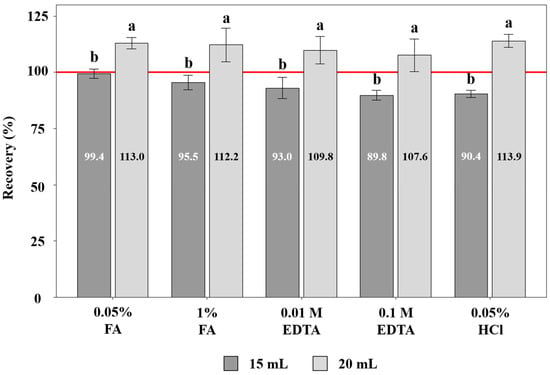

At a 20 mL pre-wetting volume, introduction of reagents led to uniformly inflated recoveries—113.0% with 0.05% FA, 112.2% with 1% FA, 109.8% with 0.01 M EDTA, 107.6% with 0.1 M EDTA, and 113.9% with 0.05% HCl (Figure 3)—all exceeding the 99.1% observed with DW alone at the same volume (Figure 2). At 20 mL, adding reagents introduces extra ions (H+/Cl−, formate, Na+–EDTA) that raise ionic strength and shift the water–acetonitrile–salt equilibrium, lowering the mutual solubility of water and acetonitrile and shrinking the acetonitrile-rich phase during SALLE [31].

Figure 3.

Effect of acidic and chelating pre-wetting media on the recovery of tebufenpyrad from soil. Different letters (a, b) indicate statistically significant differences between the 15 mL and 20 mL pre-wetting conditions (t-test, p < 0.05). Values represent means of triplicate analyses (n = 3).

By contrast, at 15 mL pre-wetting, the recoveries remained in an acceptable 90–100% window—99.4% (0.05% FA), 95.5% (1% FA), 93.0% (0.01 M EDTA), 89.8% (0.1 M EDTA), and 90.4% (0.05% HCl)—with 0.05% FA closest to quantitative recovery (Figure 3). These results indicate that reagent identity exerted a secondary influence compared with volume and that 15 mL provides accurate, unbiased extraction, whereas 20 mL risks systematic overestimation across all media. The non-linear EDTA response likely reflects competing effects: at 0.01 M, EDTA disrupts Fe/Al-oxide–pesticide associations and enhances desorption, whereas at 0.1 M, excessive chelation increases ionic strength and alters aqueous-phase conditions, interfering with efficient salting-out and reducing transfer of the analyte into the acetonitrile phase [16,31,34].

Matrix effects estimated from matrix-matched calibration were small across all pre-wetting media and volumes (Figure S1). For 15 mL, effects ranged from −3% to +8%; for 20 mL, they were within −3% to +5%, and confidence intervals overlapped broadly among reagents. Thus, all conditions fell within the commonly accepted “negligible” band (±20%), and no systematic dependence on reagent identity or volume was evident. In conjunction with matrix-matching, these minor effects indicate that the > 100% apparent recoveries at 20 mL are unlikely to arise from ionization enhancement and instead support the interpretation of phase-volume contraction during partitioning.

3.3. Desorption Efficiency in Field-Treated Soil

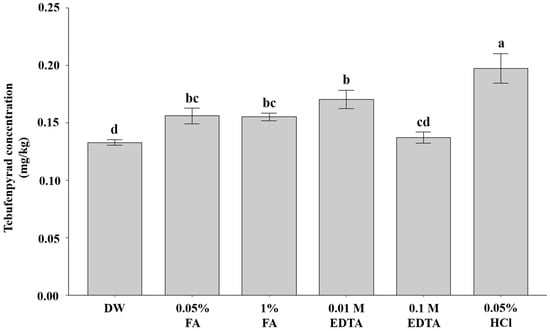

Residue levels in field-treated soil were evaluated under desorption-relevant conditions rather than inferred from spike recoveries, because soil aging diminishes extractability, and extraction outcomes depend strongly on the extraction conditions [35]. In view of sorption–desorption control of pesticide availability and the frequent occurrence of hysteresis, equal soil aliquots were contacted with a fixed 15 mL pre-wetting solution of different chemistries (DW, FA, EDTA, HCl) under identical QuEChERS steps, and the in situ residue concentrations were compared (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of acidic and chelating pre-wetting media on tebufenpyrad desorption efficiency in field-treated soil. Different letters (a–d) indicate statistically significant differences among treatments based on Tukey’s HSD (p < 0.05). Values represent means of triplicate analyses (n = 3).

Relative to DW (0.13 mg/kg), FA in water increased the measured tebufenpyrad concentration to 0.16 mg/kg, and 0.01 M EDTA produced a larger increase to 0.17 mg/kg. FA at 0.05% and 1% did not differ significantly from one another, indicating that mild acidification was sufficient and that stronger acidification did not confer additional benefit. EDTA in water exhibited a non-monotonic response: increasing the concentration to 0.1 M reduced the effect to 0.14 mg/kg, statistically indistinguishable from DW, showing that greater chelation strength did not improve desorption under these conditions. By contrast, 0.05% HCl gave the highest response at 0.20 mg/kg, significantly exceeding DW and all other reagents. Collectively, these results indicate that desorption efficiency was reagent-dependent but not simply concentration-driven, with 0.05% HCl at 15 mL providing the most effective pre-wetting for field soil.

A mechanistic interpretation for the superior desorption with 0.05% HCl is supported by soil chemistry literature. Hydrochloric acid, even at modest strength, promotes cationic hydrolysis and dissolution of Fe (III) (oxyhydr)oxides such as amorphous ferrihydrite, disrupting metal-bridged and surface-complexed domains that retain contaminants; this mechanism was shown directly in soil-washing experiments where HCl enhanced ferrihydrite breakdown and mobilization of sorbed species [18]. Because pesticides are frequently associated with iron (hydr)oxides and organic matter by ligand exchange/charge-transfer interactions, weakening these Fe-oxide scaffolds by acid treatment plausibly increases the fraction that becomes extractable in our matrix [17]. Taken together with the field results, these reports provide a consistent rationale for adopting 0.05% HCl (15 mL) as the pre-wetting step in this soil to maximize desorption without biasing quantitation. This interpretation aligns with prior evidence on Fe-oxide-mediated sorption–desorption processes; however, it should be regarded as a plausible rather than definitive mechanism because the present study did not directly measure soil pH, Fe/Al speciation, or mineralogical changes under 0.05% HCl treatment.

3.4. Method Validation

Matrix-matched calibration was linear across the working range (r2 = 0.9990, exceeding the conventional ≥ 0.99 benchmark), and the LOQ of 0.005 mg/kg met the SANTE/2020/12830 acceptance for soil monitoring (≤0.05 mg/kg) [36], providing sensitivity suitable for tracking time-dependent declines in residues (Table 2). Method trueness and precision were satisfactory at all levels—mean recoveries of 86.7% (RSD 6.2%) at 0.01 mg/kg, 99.8% (0.3%) at 0.1 mg/kg, and 98.5% (1.2%) at 30 mg/kg with no carryover observed—with only a slight low bias at the lowest spike; overall, results fell within the SANTE acceptance window (70–120% with RSD ≤ 20%) [36]. Collectively, these outcomes demonstrate compliance with SANTE criteria and confirm that the method is fit for quantitative determination of tebufenpyrad in soil.

Table 2.

Validation results for the quantitative determination of tebufenpyrad in soil. Values represent means of triplicate analyses (n = 3).

Compared with two recent soil multiresidue methods based on QuEChERS extraction, which reported method LOQs of 0.01 mg/kg and satisfactory recoveries of approximately 80–100% for tebuconazole [37,38], our method achieves a lower LOQ (0.005 mg/kg) and thus greater sensitivity for trace-level monitoring of tebufenpyrad during the late phase of dissipation. In addition, quantitative performance was confirmed not only at regulatory validation levels (0.01–0.1 mg/kg) but also at a very high spike of 30 mg/kg, demonstrating accurate dilution back-calculation, which is important for soils that may temporarily contain ppm-level residues following field application. Unlike generic QuEChERS workflows, in which the soil is pre-hydrated with pure water, the present protocol was specifically designed to address the strong sorption of tebufenpyrad by incorporating a 0.05% HCl pre-wetting step to enhance desorption from mineral–organic domains. As a result, the method complements existing multiresidue QuEChERS approaches by offering improved sensitivity and robustness across a wider concentration range, while more explicitly accounting for sorption-limited residues in greenhouse soils. In view of the robust performance of multiresidue QuEChERS methods in diverse soils, our method is also expected to be adaptable to other soil types beyond sandy loam by adjusting the type or concentration of desorption agents used in the pre-wetting step.

3.5. Residue Dissipation in Soil at the Recommended and Doubled Application Rates

Time-course residues of tebufenpyrad in greenhouse soil were monitored after application at the recommended rate (1×) and at the doubled rate (2×). At day 0, mean residues were 1.9 mg/kg (1×) and 4.8 mg/kg (2×) and declined to 0.3 mg/kg and 0.7 mg/kg, respectively, by day 46 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dissipation kinetics of tebufenpyrad in soil at two application rates. (a) Recommended rate (1×): DT50 = t1/2 = 19.8 d (r2 = 0.9597); (b) Doubled rate (2×): t1/2 = 20.4 d (r2 = 0.9362). All data points represent means of triplicate measurements (n = 3).

Exponential fits to the data followed first-order kinetics, as expressed in Equation (2):

where C0 is the initial residue concentration (mg/kg), Ct is the residue concentration at time t (d), and k is the first-order rate constant (d−1).

The corresponding half-life (DT50) was calculated using Equation (3):

The fitted rate constants were k = 0.035 d−1 (r2 = 0.9597) for 1× and k = 0.034 d−1 (r2 = 0.9362) for 2×, corresponding to t1/2 = 19.8 d and 20.4 d, respectively. Thus, initial residue levels scaled proportionally with application rate, whereas the subsequent decline proceeded at nearly identical rates, consistent with first-order dissipation under uniform greenhouse conditions. Plots of tebufenpyrad residues in soil over time showed a clear log-linear decline without visual irregularities, supporting the adequacy of a first-order kinetic model. In line with the Forum for the Co-ordination of Pesticide Fate Models and their Use (FOCUS) degradation kinetics guidance [39], which recommends retaining single first-order (SFO) kinetics when the x2-based error percentage is ≤ 15% and visual fits are acceptable, the SFO model provided an adequate description of the dissipation data at both application rates.

Groundwater leaching potential was assessed using the groundwater ubiquity score (GUS), an index that combines degradation and sorption behavior. The GUS is defined as

where t1/2 is the soil half-life (d), and Koc is the organic carbon-normalized sorption coefficient (mL/g).

The DT50 values from this greenhouse study (≈20 d), the EFSA laboratory soil study (33.9 d at 20 °C), and the PPDB field study (4.5 d) were combined with the reported Koc of 9310 mL/g to calculate GUS values for tebufenpyrad [24,40]. The resulting scores were consistently low (0.02–0.05; Table S1). In the GUS classification scheme, compounds with scores < 1.8 are categorized as non-leachers, those with scores between 1.8 and 2.8 as transitional, and those with scores > 2.8 as potential leachers [41]. Because the GUS values for tebufenpyrad fall well below the non-leacher threshold of 1.8 proposed by Gustafson, they indicate a very low propensity for non-point leaching to groundwater. The similarity of GUS values across laboratory, greenhouse, and field scales further suggests that strong sorption largely governs the groundwater leaching potential of tebufenpyrad, making its classification as an improbable leacher robust to differences in experimental conditions [42]. Liu et al. (2017) found similar results for chlorpyrifos: even though the half-life was slightly longer under greenhouse conditions than in the open field, the GUS value and its groundwater leaching category remained the same [8].

Compared with other pyrazole-based pesticides, fenpyroximate shows DT50 values of 21.3 d in various soils and high sorption (Koc 45,300–50,000 mL/g) [43], resulting in very low GUS values (−0.93 to −0.87), whereas fipronil (DT50 ≈ 30.1–33.4 d in sandy loam; Koc 1248 mL/g) [44,45] yields a GUS of 1.34–1.38, still within the non-leacher category. Although soil persistence shows some variation among pyrazole pesticides, all of them have GUS values less than 1.8 and are therefore generally biased toward retention in surface soils rather than leaching to groundwater [42]. Consequently, environmental fate and risk assessments for this chemotype should focus mainly on residues in the topsoil and their potential transfer to edible plant parts, while groundwater exposure can be considered a secondary concern except under particularly vulnerable conditions.

Foliar-application studies have reported short biological half-lives of tebufenpyrad in leafy vegetables; for example, half-lives of 3.0–4.2 d in angelica leaves [46] and 3.8–4.2 d in Aster scaber [47], which are shorter than the soil DT50 measured in this study. Unlike in soil, where strong sorption to organic matter can retard degradation, surface residues on leaves are exposed to weathering processes such as photolysis and volatilization, explaining the faster dissipation observed in crops [47]. Because tebufenpyrad shows limited or no systemic movement and is predominantly used as a foliar-applied product, transfer from deeper soil or groundwater into edible plant tissues is expected to be minimal. Considering the low GUS values obtained for tebufenpyrad in soil, these patterns suggest that residues of greatest relevance for risk assessment are associated with treated foliage and the upper soil layer rather than with leached residues [41,48].

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated extraction efficiency and soil dissipation behavior of tebufenpyrad in sandy loam soil and established an optimized QuEChERS-based method suitable for quantitative monitoring. Pre-wetting volume was identified as a critical parameter governing both phase separation and desorption efficiency during extraction. Hydration volumes of 15–20 mL yielded near-quantitative recoveries (94.6–99.1%), ensuring adequate wetting and unbiased salting-out, whereas excessive hydration at 25 mL led to contraction of the acetonitrile-rich phase and apparent overestimation. Among acidic and chelating pre-wetting media, 15 mL of 0.05% HCl afforded the highest desorption efficiency in field-treated soil, consistent with evidence that dilute mineral acids can disrupt Fe-oxide-bound domains and promote release of sorbed residues. The established method achieved linearity (r2 = 0.9990), precision (RSD ≤ 6.2%), and trueness within SANTE acceptance criteria, with an LOQ of 0.005 mg/kg, demonstrating its suitability for soil residue monitoring and dissipation studies in greenhouse sandy loam soils. Under greenhouse conditions, tebufenpyrad dissipation followed first-order kinetics with half-lives (DT50) of 19.8 d (1× rate) and 20.4 d (2× rate), indicating dose-independent behavior. These findings underscore the influence of soil hydration and pre-wetting chemistry on pesticide desorption and confirm the moderate persistence of tebufenpyrad in sandy loam soil, providing a robust analytical basis for future residue monitoring and environmental risk assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010091/s1, Figure S1: Matrix effects under different pre-wetting media and volumes (15 and 20 mL) in the QuEChERS extraction of tebufenpyrad. Values represent means of triplicate analyses (n = 3). Table S1: Soil dissipation DT50, Koc and groundwater ubiquity scores (GUS) for tebufenpyrad (greenhouse, field, and laboratory soils) and related pyrazole pesticides (laboratory sandy loam soils).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, Y.-H.L. and J.-W.B.; software, Y.-W.C. and T.-G.M.; validation, Y.-H.L. and W.-G.O.; formal analysis, Y.-H.L.; investigation, Y.-H.L. and D.-G.L.; resources, T.-G.M. and W.-G.O.; data curation, Y.-W.C. and D.-G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, J.-W.B.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dong-A University research fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarkar, B.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Ramanayaka, S.; Bolan, N.; Ok, Y.S. The role of soils in the disposition, sequestration and decontamination of environmental contaminants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 307: Aerobic and Anaerobic Transformation in Soil; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Mol, H.G.J.; Zomer, P.; Tienstra, M.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils—A hidden reality unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, S.; Rasool, T.; Gani, K.M. A review of interactions of pesticides within various interfaces of intrinsic and organic residue amended soil environment. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh-Zadeh, F.; Abd Wahid, S.; Jalili, B. Sorption, degradation and leaching of pesticides in soils amended with organic matter: A review. Adv. Environ. Technol. 2017, 3, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gevao, B.; Semple, K.T.; Jones, K.C. Bound pesticide residues in soils: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 108, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, D.; Zhang, L.; Jian, M.; Fan, J. Dissipation kinetics of chlorpyrifos in soils of a vegetable cropping system under different cultivation conditions. Agric. Sci. 2017, 8, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Curbelo, M.Á.; Varela-Martínez, D.A.; Riaño-Herrera, D.A. Pesticide-Residue Analysis in Soils by the QuEChERS Method: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanetou, E.N.; Karasali, H. A Comprehensive Review of Organochlorine Pesticide Monitoring in Agricultural Soils: The Silent Threat of a Conventional Agricultural Past. Agriculture 2022, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiades, M.; Lehotay, S.J.; Štajnbaher, D.; Schenck, F.J. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and “dispersive solid-phase extraction” for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łozowicka, B.; Rutkowska, E.; Jankowska, M. Influence of QuEChERS modifications on recovery and matrix effect during the multi-residue pesticide analysis in soil by GC/MS/MS and GC/ECD/NPD. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7124–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadeo, J.L.; Pérez, R.A.; Albero, B.; García-Valcárcel, A.I.; Sánchez-Brunete, C. Review of Sample Preparation Techniques for the Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Soil. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia-Sá, L.; Fernandes, V.C.; Carvalho, M.; Calhau, C.; Domingues, V.F.; Delerue-Matos, C. Optimization of QuEChERS method for the analysis of organochlorine pesticides in soils with diverse organic matter. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicari, M.C.; Facco, J.F.; Peixoto, S.C.; de Carvalho, G.S.; Floriano, L.; Prestes, O.D.; Adaime, M.B.; Zanella, R. Simultaneous Determination of Multiresidues of Pesticides and Veterinary Drugs in Agricultural Soil Using QuEChERS and UHPLC–MS/MS. Separations 2024, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafay, F.; Daniele, G.; Fieu, M.; Pelosi, C.; Fritsch, C.; Vulliet, E. Ultrasound-assisted QuEChERS-based extraction using EDTA for determination of currently-used pesticides at trace levels in soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchańska, H.; Czaplicka, M.; Kyzioł-Komosińska, J. Interaction of selected pesticides with mineral and organic soil components. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2020, 46, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Hwang, J.S.; Choi, S.I. Sequential soil washing techniques using hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide for remediating arsenic-contaminated soils in abandoned iron-ore mines. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonowski, N.D.; Linden, A.; Köppchen, S.; Thiele, B.; Hofmann, D.; Burauel, P. Dry–wet cycles increase pesticide residue release from soil1*. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012, 31, 1941–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalabi, A.M.; Meetani, M.A.; Shabib, A.; Maraqa, M.A. Sorption of pharmaceutically active compounds to soils: A review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, T.B.; Richardson, J.R.; Testa, C.M.; Seo, B.B.; Panov, A.V.; Yagi, T.; Matsuno-Yagi, A.; Miller, G.W.; Greenamyre, J.T. Mechanism of toxicity of pesticides acting at complex I: Relevance to environmental etiologies of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2007, 100, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC). Mode of Action Classification Scheme. Version 11.4. May 2025. Available online: https://irac-online.org/documents/moa-classification/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Charli, A.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Alterations in mitochondrial dynamics induced by tebufenpyrad and pyridaben in a dopaminergic neuronal cell culture model. Neurotoxicology 2016, 53, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Conclusion Regarding the Peer Review of the Pesticide Risk Assessment of the Active Substance Tebufenpyrad; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scheringer, M.; Strempel, S.; Hukari, S.; Ng, C.A.; Blepp, M.; Hungerbuhler, K. How many persistent organic pollutants should we expect? Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2012, 3, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ayari, T.; Mhadhbi, L.; Menif, N.T.E.; Cafsi, M.E. Acute toxicity and teratogenicity of carbaryl (carbamates), tebufenpyrad (pyrazoles), cypermethrin and permethrin (pyrethroids) on the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L., 1758) early life stages. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 66125–66135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Field Book for Describing and Sampling Soils; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Kruve, A.; Rebane, R.; Kipper, K.; Oldekop, M.-L.; Evard, H.; Herodes, K.; Ravio, P.; Leito, I. Tutorial review on validation of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry methods: Part I. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 870, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Dacal, A.; Rial-Berriel, C.; Díaz-Díaz, R.; Bernal Suárez, M.d.M.; Zumbado, M.; Henríquez-Hernández, L.A.; Luzardo, O.P. Supporting dataset on the optimization and validation of a QuEChERS-based method for the determination of 218 pesticide residues in clay loam soil. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Shao, J.; Mei, W.; Wang, L. Development and application of a dispersive solid-phase extraction method for the simultaneous determination of chloroacetamide herbicide residues in soil by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS). Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 99, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhuang, B.; Lu, Y.; An, L.; Wang, Z.-G. Salt-Induced Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation: Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of Water–Acetonitrile–Salt Mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.W.; White, J.L. Review of adsorption and desorption of organic pesticides by soil colloids with implications concerning bioactivity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1964, 12, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, D.; Wang, D.; Tan, M.; Geng, M.; Zhu, C.; Chen, N.; Zhou, D. Extensive production of hydroxyl radicals during oxygenation of anoxic paddy soils: Implications to imidacloprid degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezahegn, T.; Tegegne, B.; Zewge, F.; Chandravanshi, B.S. Salting-out assisted liquid–liquid extraction for the determination of ciprofloxacin residues in water samples by high performance liquid chromatography–diode array detector. BMC Chem. 2019, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Papiernik, S.K.; Koskinen, W.C.; Yates, S.R. Evaluation of Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) for Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 3249–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guidance Document on Pesticide Analytical Methods for Risk Assessment and Post-approval Control and Monitoring Purposes; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Lee, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Jeong, D.; Lee, H. Optimization of soil-based QuEChERS extraction and comparative assessment of analytical efficiency by physicochemical characteristics of pesticides. Ecotox. Environ. Safe 2025, 305, 119280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiantas, P.; Bempelou, E.; Doula, M.; Karasali, H. Validation and Simultaneous Monitoring of 311 Pesticide Residues in Loamy Sand Agricultural Soils by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS, Combined with QuEChERS-Based Extraction. Molecules 2023, 28, 4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focus Degradation Kinetics Workgroup. Generic Guidance for Estimating Persistence and Degradation Kinetics from Environmental Fate Studies on Pesticides in EU Registration; FOCUS (Forum for the Co-Ordination of Pesticide Fate Models and Their Use): Ispra, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- PPDB: Pesticide Properties DataBase—Tebufenpyrad. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/612.htm (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Gustafson, D.I. Groundwater ubiquity score: A simple method for assessing pesticide leachability. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1989, 8, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Kim, T.-K.; Kim, S.-I.; Jeong, W.-T. Influence of Soil Types and Organic Amendment During Persistence, Mobility, and Distribution of Phorate and Terbufos in Soils. Korean J. Pestic. Sci. 2023, 27, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Conclusion Regarding the Peer Review of the Pesticide Risk Assessment of the Active Substance Fenpyroximate; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin, C.D.S. The Pesticide Manual: A World Compendium, 15th ed.; British Crop Production Council: Alton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, K.; Singh, B. Persistence of fipronil and its metabolites in sandy loam and clay loam soils under laboratory conditions. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Jeong, M.-J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Eun, H.-R.; Kim, S.-M.; Baek, J.-W.; Noh, H.H.; Shin, Y.; Choi, H. Comparative Biological Half-Life of Penthiopyrad and Tebufenpyrad in Angelica Leaves and Establishment of Pre-Harvest Residue Limits (PHRLs). Foods 2024, 13, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Shin, Y.; Ko, R.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.; An, D.; Chang, H.-R.; Lee, J.-H. Dissipation Kinetics and Risk Assessment of Spirodiclofen and Tebufenpyrad in Aster scaber Thunb. Foods 2023, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, M.; Onjia, A. Prioritization and Sensitivity of Pesticide Risks from Root and Tuber Vegetables. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.