Abstract

This experiment evaluated the application effects of the dietary substitution of maize silage with mixed silage prepared with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw on fattening lambs. Forty-eight male Hu lambs with similar body weights and ages were randomly divided into four groups. The maize silage in the diet was replaced with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw mixed silage in proportions of 0 (CON), 25% (PR1), 50% (PR2) and 75% (PR3). The average daily gain of the PR3 group was lower (p < 0.05) than that of the other groups. The highest substitution level increased (p < 0.05) ruminal ammonia nitrogen concentration and acetate-to-propionate ratio in lambs compared with the CON and PR1 groups. Moreover, dry matter and neutral detergent fiber digestibility in PR3 lambs were lower (p < 0.05) than in PR1 lambs. Compared with the CON group, the concentrations of serum catalase and total antioxidant capacity were increased (p < 0.05) in the PR2 and PR3 groups. Overall, the dietary substitution of maize silage with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw mixed silage at a 50% level did not show a negative influence on growth performance of fattening lambs but displayed positive effects on their fiber digestibility and antioxidative capacity.

1. Introduction

In ruminant production, the sufficient provision of high-quality roughage is essential to maintaining ruminal function and improving production performance [1,2]. In recent years, a variety of unconventional feeds have been introduced into the roughage system for ruminants, but to a large extent, maize silage is used as the main ingredient in the diet [3]. Nevertheless, the yield of maize is limited in some areas of the world, which restricts the utilization of maize silage in animal farming [4]. The shortage of high-quality roughage has become a restrictive factor in the stable development of the ruminant industry. Thus, exploring new roughage sources that do not have negative effects on the production performance of ruminants has attracted more and more attention.

Plants that can adapt to severe environments, such as those with saline–alkali soil and a lack of water resources, have been increasingly used as feed in the diets of animals [5,6]. Pennisetum giganteum (PG) is a perennial gramineous plant that has an extremely strong tillering ability, high nutritional value and low management costs [7]. According to the statistics of our group, the yield of PG mowed at the elongation stage can reach up to 190 t/hm2 and 26 t/hm2 on the basis of fresh and dry matter (DM) weights, respectively [8]. Compared with some plants, such as maize, PG has lower contents of nitrate and oxalic acid [9]. PG is commonly used to make silage, but the silage quality of PG is relatively low because of its high water concentration (88%), which is not conducive to lactic acid bacteria fermentation [10]. In our previous study, rice straw and PG were used as ensiling materials, and the results showed that the nutritional value, fermentation process and in vitro digestibility were improved after supplementation with lactic acid bacteria and cellulase [11]. In a previous study on goats, dietary supplementation with fermented PG was found to enhance antioxidant ability and regulate gastrointestinal microbial communities to improve immune function, which is helpful for relieving heat stress and promoting growth [12].

Compared with traditional grazing patterns, the moving space and feed type of sheep are changed under the modern intensive system, which causes oxidative stress, ultimately reducing immunity and growth performance [13]. PG contains a variety of trace elements, especially selenium (0.13 mg/kg), which is an important antioxidant trace element and can neutralize free radicals to reduce oxidative damage [9]. In addition, the polyphenol substances of PG, mainly including flavone (300 to 600 mg/kg) and ferulic acid (200 mg/kg), exert antioxidant effects by scavenging free radicals and activating antioxidant enzyme systems, including glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) [9]. Using PG as an ingredient in the diet may be beneficial for enhancing the antioxidative capacity of animals. However, to date, there are no in vivo data on replacing maize silage with mixed PG and rice straw silage in fattening lambs, nor on the consequences for serum immune and antioxidant responses. In this study, we hypothesized that replacing up to 50% of maize silage with PG and rice straw mixed silage would maintain growth performance while improving fiber digestibility, immune status and antioxidant capacity in fattening lambs. Therefore, the current experiment evaluated the influence of different mixed silage ratios to replace maize silage in the diet on weight gain, ruminal fermentation characteristics, apparent digestibility and serum antioxidant indices in fattening lambs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silage Preparation

The maize silage used in this experiment was obtained from a commercial sheep farm, and the whole plant was harvested at the milk stage of maize. During the fermentation process, the lactic acid bacteria and cellulase were used as additives, and detailed information on the additives was shown in our previous study [11]. Additionally, the production process of mixed silage prepared with PG and rice straw was detailedly described in our previous study [11]. In brief, the mixing ratio of PG and rice straw was 73%:27%. The additives used for improving the quality of mixed silage were the same as maize silage, and the ensiling process was finished in a silage silo that lasted for 60 d. The quality of all the silage in this study was high, and the chemical compositions of mixed silage and maize silage are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of silage used in this study (DM basis, %).

2.2. Experimental Animals and Treatments

The animal experiment was carried out from March (2025) to May (2025) and performed at a commercial sheep farm (Changji, China; 87°13′ east longitude and 44°36′ northern latitude). During the feeding trial, the temperature of the sheep barn was ranged from 2 °C to 27 °C. In total, forty-eight healthy male fattening Hu sheep lambs with similar body weights (BW, 22.69 ± 0.68 kg) and ages (3 months old) were utilized as test subjects and randomly divided into four groups with twelve replicates in each group. One group was served as the control, with no mixed silage prepared with PG and rice straw supplementation, and the maize silage in the basal diet of the other 3 groups was replaced with mixed silage in the proportions of 25% (PR1), 50% (PR2) and 75% (PR3).

The lambs in this experiment were placed in individual pens with an area of 2 m × 2 m and fed corresponding diets twice daily at 09:00 and 17:00, permitting approximately 5% refusals with free access to drinking water. Before the experiment, pens with good ventilation were thoroughly disinfected, and all the lambs were dewormed. The experimental diets with a 35:65 roughage-to-concentrate ratio were designed on the basis of standards from the NRC [14]. In order to guarantee isoenergetic and isonitrogenous rations for all the groups, the ingredients of maize, soybean meal, cottonseed meal and wheat bran were slightly changed with the increase in mixed silage. All lambs were fed with the total mixed ration (Kangmu Machinery Co., Ltd., Jining, China). Table 2 presents the feedstuff ingredients and nutritional levels of all diets in this feeding experiment. The length of the adaptive phase was 7 days, and the formal feeding period lasted for 60 days.

Table 2.

Ingredients and nutritional levels of diet used in this study (DM basis).

2.3. Determination of Weight Gain and Feed Intake

On days 0 and 60, prior to the morning feeding, the BW of all experimental animals was recorded by a digital weighing scale (Bot Instrument Co., Ltd., Lianyungang, China). Average daily gain (ADG) was obtained by subtracting the initial BW from the final BW and dividing by the number of feeding days. The dry matter intake (DMI) was calculated from the difference value between the feed provided and refusals. Feed conversion efficiency of lambs was computed by dividing DMI by ADG.

2.4. Analysis of Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics

On the last day of the experiment, ruminal fluid from all fattening lambs was sampled by utilizing a portable gastric tubing device (Huazhi Kaiwu Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) approximately 4 h post-morning feeding. During the collection of ruminal fluid, the first 30 mL of samples obtained from each lamb were discarded to avoid saliva contamination. The pH of freshly collected fluid samples was immediately measured using a handheld pH meter (Leici Instruments and Meters Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China). After filtration with 4 layers of cheesecloth, aliquots of 5 mL of the samples were mixed with 1 mL of 25% metaphosphoric acid. Then, the liquid supernatant was collected from the mixture by centrifuging at 25,131× g for 10 min and was used to determine the concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFAs), including acetate, propionate and butyrate, through a gas chromatograph (GC-2010, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) following the procedures described in our previous study [16]. Additionally, aliquots of 10 mL of the same fluid samples were subjected to centrifugation at 25,131× g for 10 min to separate the liquid supernatant, which was used to analyze the ruminal concentrations of ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) [17] and microbial protein (MCP) [18] with reference to the previous methods.

2.5. Measurement of Nutrient Digestibility

Feces were sampled by utilizing nylon mesh trays placed beneath the individual pen. The fecal leakage board was used as the pen floor of lambs. From day 54 to 59 of the feeding period, all the feces of each lamb were collected and preserved in a plastic bucket with a lid. During the collection of fecal samples, the feed provided and refusals of the corresponding animal were sampled daily. The detailed management processes of feed and feces were described in our previous study [16]. In brief, after the drying and grinding of feed and feces, the contents of crude protein (CP; method 984.13), DM (method 934.01), ether extract (EE; method 954.02) and ash (method 942.05) in these samples were measured following the official procedures of AOAC [19]. The content of organic matter (OM) was calculated from ash. Additionally, the fiber fractions, including acid detergent fiber (ADF) and neutral detergent fiber (NDF), in the feed and fecal samples were analyzed using a fiber analyzer (ANKOM A2000i; Ankom Technology, New York, NY, USA). The apparent digestibility (%) of each nutrient was evaluated by calculating the percentage of ingested nutrients which were not excreted in the feces.

2.6. Assessment of Serum Biochemical, Immune and Antioxidative Parameters

On the last day of the feeding period, blood from all fattening lambs was sampled from the jugular vein by 5 mL vacuum blood collection tubes prior to the morning feeding. After standing for 30 min, blood was subjected to centrifugation at 1509× g for 12 min to separate serum, which was stored in 2 mL centrifugal tubes. The biochemical indicators associated with liver function, energy metabolism and protein turnover, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), triglyceride, non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA), glucose, urea nitrogen (UN), total protein (TP), albumin and globulin, in the serum samples were quantified using an automatic biochemical analyzer (BS-360S, Ali Road Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). Apart from these parameters, the serum concentrations of immune and antioxidative indices, including immunoglobulin A (IgA, H108), IgG (H106), IgM (H109), interleukin-1β (IL-1β, H002), IL-6 (H007), IL-10 (H009), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, H052), GSH-Px (A005), malonaldehyde (MDA, A003), CAT (A007), SOD (A001) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC, A015), were determined using commercial kits purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), following the protocols recommended by the manufacturer. The numbers starting with H and A are the product codes of the kits.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Before analysis, the data were subjected to tests of normality and homogeneity of variances, and results showed that the data were normally distributed. Next, variables of all data, including growth performance, ruminal fermentation, apparent digestibility and serum parameters, were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA methods of SPSS statistical software (version 24.0) on the basis of each fattening lamb serving as an experimental unit. In order to assess the linear and quadratic effects of increase in dietary mixed silage proportions, orthogonal and polynomial contrasts were performed. Tukey’s test was carried out to evaluate the differences among the four treatments. Results are shown with mean values and standard errors of the means. Statistical significance was accepted at a threshold of p < 0.05, while p-values between 0.05 and 0.10 were regarded as tendencies.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance of Lambs

As expected, the final BW and ADG of PR3 lambs were lower (p < 0.05) than those of CON, PR1 and PR2 lambs (Table 3). The ADG and BW of lambs did not show differences (p > 0.05) among the CON, PR1 and PR2 groups. Dietary supplementation of PG and rice straw mixed silage did not affect (p > 0.05) the DMI of lambs. However, there was a tendency (0.05 < p < 0.10) for a higher ratio of DMI to ADG in the PR3 group compared with the CON group.

Table 3.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on the growth performance of fattening lambs.

3.2. Rumen Fermentation in Lambs

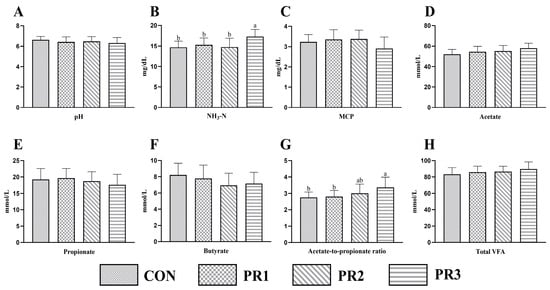

As illustrated in Figure 1A, the ruminal pH did not show significant change after mixed silage supplementation. Likewise, no difference (p > 0.05) in ruminal propionate (Figure 1E), butyrate (Figure 1F) and total VFA (Figure 1H) contents was observed among the four groups. Compared with CON, PR1 and PR2 lambs, in PR3 lambs, the NH3-N concentration (Figure 1B) was increased (p < 0.05). There was a trend (0.05 < p < 0.10) for higher ruminal MCP content (Figure 1C) in the PR1 and PR2 groups compared with the PR3 group. However, the ratio of acetate to propionate (Figure 1G) in the PR3 group was higher (p < 0.05) than that in the CON and PR1 groups. Additionally, the acetate concentration (Figure 1D) of PR3 lambs tended to be increased (0.05 < p < 0.10) by 11.13% compared with CON lambs.

Figure 1.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on the rumen fermentation characteristics of fattening lambs. (A) pH; (B) NH3-N; (C) MCP; (D) acetate; (E) propionate; (F) butyrate; (G) acetate-to-propionate ratio; (H) total VFA. NH3-N, ammonia nitrogen; MCP, microbial protein; VFA, volatile fatty acid. CON, diet without mixed silage; PR1, PR2 and PR3, 25%, 50% and 75% of maize silage in the diet substituted with a corresponding amount of mixed silage, respectively. Different small letters above the columns indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.3. Nutrient Digestibility in Lambs

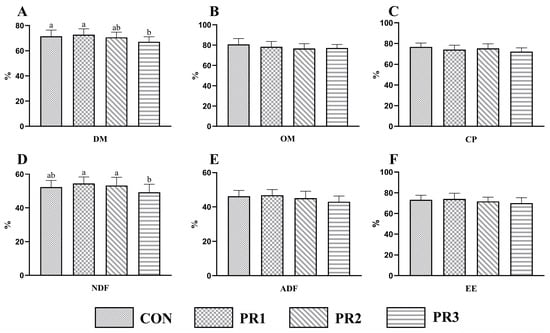

Dietary replacement of maize silage with mixed silage did not have significant effects on OM (Figure 2B) and EE (Figure 2F) digestibility. Compared with the CON and PR1 groups, in the PR3 group, DM digestibility (Figure 2A) was reduced (p < 0.05). There was a tendency (0.05 < p < 0.10) for lower digestibility of CP (Figure 2C) in the PR3 group than in the CON group. Similarly, ADF digestibility (Figure 2E) in the PR3 group tended to be lower (0.05 < p < 0.10) than that in the CON and PR1 groups. In addition, NDF digestibility (Figure 2D) following the PR1 and PR2 treatments was higher (p < 0.05) than after the PR3 treatment, but no difference (p > 0.05) was observed among the CON, PR1 and PR2 groups.

Figure 2.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on nutrient digestibility in fattening lambs. (A) DM; (B) OM; (C) CP; (D) NDF; (E) ADF; (F) EE. DM, dry matter; OM, organic matter; CP, crude protein; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; EE, ether extract. CON, diet without mixed silage; PR1, PR2 and PR3, 25%, 50% and 75% of maize silage in the diet substituted with a corresponding amount of mixed silage, respectively. Different small letters above the columns indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.4. Serum Biochemical Indicators in Lambs

Different levels of mixed silage to replace maize silage in the diet had no significant effects on the serum concentrations of TP, albumin, globulin, NEFA, ALT, AST and ALP in lambs (Table 4). Nevertheless, the serum glucose content in PR3 lamb was lower (p < 0.05) than that in CON and PR1 lambs, while an opposite trend of the UN level (p < 0.01) was found between PR3 and these two groups. Compared with the CON and PR1 groups, the serum triglyceride concentration in the PR3 group tended to be decreased (0.05 < p < 0.10) by 8.98% and 7.26%, respectively. Overall, increasing mixed silage levels decreased glucose and increased UN contents, indicating reduced nitrogen utilization at high replacement levels.

Table 4.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on serum biochemical indicators in fattening lambs.

3.5. Serum Immunoglobulin in Lambs

As shown in Table 5, the serum IgG concentration was not different (p > 0.05) after mixed silage supplementation. In contrast, the PR2 and PR3 treatments showed an increasing trend (0.05 < p < 0.10) in IgA compared with the CON group. Also, the IgM content in the PR2 group tended to be higher (0.05 < p < 0.10) than that in the CON group.

Table 5.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on serum immunoglobulin contents in fattening lambs.

3.6. Serum Cytokine Levels in Lambs

The serum contents of IL-10 and IL-1β were not different (p > 0.05) among all the treatments (Table 6). Compared with CON lambs, the TNF-α concentration in PR1 and PR2 lambs was decreased (p < 0.05). Likewise, the 50% and 75% substitution proportions displayed a decreased tendency (0.05 < p < 0.10) in serum IL-6 content when compared with the CON group.

Table 6.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on serum cytokine contents in fattening lambs.

3.7. Serum Antioxidant Indices in Lambs

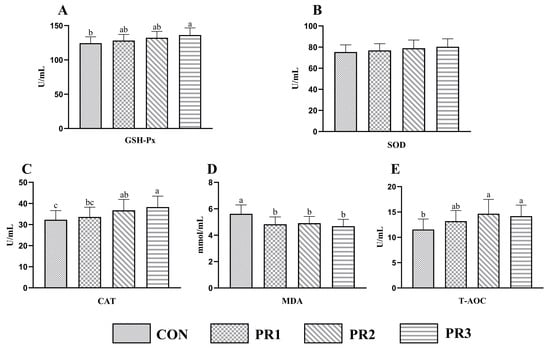

The replacement of maize silage with PG and rice straw mixed silage at the 25%, 50% and 75% levels all decreased (p < 0.05) serum MDA concentration (Figure 3D). The serum activity of CAT (Figure 3C) and T-AOC (Figure 3E) in PR2 and PR3 lambs was increased (p < 0.05) when compared with CON lambs. Furthermore, lambs fed the highest mixed silage level had elevated (p < 0.05) GSH-Px activity (Figure 3A). However, there was no difference (p > 0.05) in SOD content (Figure 3B) among all the groups.

Figure 3.

Effects of substitution of maize silage with mixed silage in the diet on serum antioxidant indices in fattening lambs. (A) GSH-Px; (B) SOD; (C) CAT; (D) MDA; (E) T-AOC. GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity. CON, diet without mixed silage; PR1, PR2 and PR3, 25%, 50% and 75% of maize silage in the diet substituted with a corresponding amount of mixed silage, respectively. Different small letters above the columns indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on the Growth Performance of Lambs

Feed intake determines the growth efficiency of animals, and ADG can be used to reflect the growth performance of animals [2]. Thus, increasing the weight gain of fattening lambs is the important task for promoting the economic benefits of the sheep industry. In the current study, the DMI did not show significant difference among all the treatments. In a previous study in Boer goats, the results showed that adding fermented feed of PG to the diet can reduce feed intake by 46.38% in animals [12], which is inconsistent with our finding. The reason may be that different fermentation processes of PG affect the intake of animals. However, the replacement of maize silage with PG and rice straw mixed silage in the 75% proportion in the diet significantly decreased the final BW and ADG of fattening lambs. A previous experiment observed that utilizing PG silage to replace 100% maize silage in the diet significantly decreased the ADG of mutton sheep [20], indicating that a high proportion of PG silage had a negative effect on the growth performance of animals, which is in accordance with our experiment. The different physical characteristics, including particle size and length, of feed ingredients in the diet affect the growth of ruminants [1]. Therefore, the reduced ADG of PR3 lambs might be associated with high lignin content in rice straw, which reduced nutrient deposition, as further verified by the apparent digestibility results. Our experiment indicated that the 75% replacement level may be too much when substituting maize silage with mixed silage prepared with PG and rice straw in fattening lambs. Based on the findings of the current study, the 50% substitution ratio did not have a negative influence on the growth performance of lambs.

4.2. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on Rumen Fermentation in Lambs

Generally, the rumen fermentation profile is determined by the feed ingredients of the diet to a great extent. The ruminal pH, which normally ranges from 6 to 7, impacts microbial growth and plays a critical role in the regulation of VFA production [5]. In this study, the pH of the rumen did not display significant differences among all the groups and remained within a normal range, suggesting that PG and rice straw mixed silage did not show adverse influence on ruminal fermentation in fattening lambs. As a critical intermediary in nitrogen cycling, ruminal NH3-N content mirrors the dynamic equilibrium between protein catabolism and anabolism, which is influenced by the degradation of dietary protein, MCP synthesis and rumen epithelial absorption [21]. In the current experiment, ruminal NH3-N concentration in PR3 lambs was higher than in other lambs, indicating that nitrogen utilization in PR3 lambs was relatively lower. With the reduction in maize silage levels, the starch content in the diet will be reduced, and CP degradation is fast, but energy degradation is slow. Thus, microorganisms are unable to efficiently utilize NH3-N to synthesize MCP due to the insufficient energy supply, leading to the increase in NH3-N concentration. Interestingly, the ruminal MCP concentration in PR3 lambs was slightly reduced compared with PR1 and PR2 lambs, which is in agreement with to the finding of increased ruminal NH3-N content.

Most energy sources required by ruminants come from VFAs, which are important for maintaining metabolism and productivity [22]. In this research study, we observed that the acetate concentration in the rumen of PR3 lambs tended to be higher than in CON lambs. In general, high-fiber forage feed can increase the ruminal acetate concentration [23], which partly explains why adding PG promotes acetate production. The reason for this result could be attributed to the fact that maize silage contains more fermentable carbohydrates, which might promote the growth of propionate-producing bacteria in the rumen, thus reducing the relative proportion of acetate [24]. In contrast, the mixed silage of PG and rice straw contain more cellulose and hemicellulose, which are degraded by microorganisms during fermentation to produce more acetate [25]. Different fiber physical characteristics between the maize silage and mixed silage might be another reason for the difference of ruminal acetate content. In future study, the effect of PG and rice straw silage on the ruminal microbial community is worthy of in-depth exploration. We also found that the ratio of acetate to propionate was significantly increased in PR3 lambs compared with CON and PR1 lambs, which suggests that the replacement of maize silage with PG and rice straw at high levels altered the rumen fermentation pattern and caused acetate-type fermentation. In ruminant production, ruminal propionate fermentation reflects improved energy utilization of feed [26], which is beneficial for supplying more energy for fattening lambs to improve growth, as seen in the ADG result.

4.3. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on Nutrient Digestibility in Lambs

Apparent digestibility is mainly used to assess the utilization efficiency of nutrients in feed and has important applications in livestock production and nutritional research, which is closely related to the growth performance of animals [27]. Our experiments showed that DM digestibility in the PR3 group was reduced when compared with the CON and PR1 groups, indicating that the lambs of the PR3 group obtained less nutrients and restricted growth, which matched the ADG result. Rice straw usually contains a high percentage of lignin, and lignin is tightly bound to other cell wall components, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, forming a physical barrier that hinders the degradation of carbohydrates by ruminal microbes and enzymes [28,29], thus reducing the digestibility of DM. NDF digestibility in lambs of the PR3 group was reduced compared with the PR1 and PR2 groups; further, PR3 lambs displayed a slight reduction in ADF digestibility compared with CON and PR1 lambs, which might be associated with high fiber content in mixed silage. In contrast, we observed that the 25% and 50% substitution proportions of mixed silage played a positive role in improving NDF digestibility. This improvement in fiber digestibility might be related to the synergistic effects among different silage types, which would promote the growth and proliferation of microorganisms associated with fiber degradation. Similarly, a previous study in dairy cows reported that NDF digestibility was increased after supplementation with two fiber forage resources [5], which is basically consistent with our study. However, the mechanism behind this synergistic effect requires further investigation. In ruminants, feedstuff can be digested by the microbial community in the rumen to produce MCP, which is easily utilized by the small intestine to improve protein digestibility [30]. Interestingly, the 75% substitution ratio slightly reduced CP digestibility in lambs, partially indicating that protein utilization in PR3 lambs was decreased. Overall, the replacement of maize silage with PG and mixed silage at the 50% level did not have a negative influence on nutrient digestibility in lambs but improved their fiber digestibility.

4.4. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on Serum Biochemical Indices in Lambs

Blood biochemical indices can be used to evaluate the health, metabolic status and organ function in ruminants [16]. The levels of ALP, ALT and AST in the serum of lambs can reflect the liver function [16]. Replacement of maize silage with mixed silage at different levels in the diets of all the groups did not significantly change the contents of ALP, ALT and AST in the serum of lambs, which indicates that the addition of mixed silage composed of PG and rice straw to the diets had no negative effect on liver function in lambs. Nevertheless, in the current research study, the serum UN content in PR3 lambs was higher than that in CON and PR1 lambs, suggesting a reduction in nitrogen conversion in fattening lambs fed a high level of mixed silage. This change in nitrogen conversion could be partly attributed to the reduced CP digestibility in PR3 lambs. A previous study in dairy cows reported that the increase in serum UN as well as ruminal NH3-N concentrations indicated a decreased nitrogen utilization rate [31]. In our experiment, considering the increased concentration of NH3-N in the rumen of PR3 lambs, a lower utilization efficiency of nitrogen can be expected, which is not helpful for promoting the growth of lambs. Consistent with our study, the replacement of maize silage by grass silage at a high level increased the serum UN concentration of cattle [32]. Moreover, in fattening animals, excessive nitrogen excretion not only decreases feed efficiency but also causes environmental pollution. In future research, we will collect urinary samples to obtain more information related to the effects of PG silage on nitrogen conversion. Our findings also revealed that the 75% substitution ratio reduced serum glucose, which suggests that energy metabolism in PR3 lambs was weakened. The reason could be attributed to the ruminal acetate-type fermentation induced by the high replacement level of mixed silage. Propionate is converted into oxaloacetate for glucose production [33], and ruminal acetate-type fermentation might reduce the proportion of propionate, thus leading to a reduction in glucose concentration in the serum of lambs. But the specific relationship between the ruminal acetate-type fermentation and glucose utilization still needs to be fully studied.

4.5. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on Serum Immune Response in Lambs

To a certain degree, the levels of immunoglobulins in the serum can be used to reflect the actual immunity of the body, and cytokines can interact with each other to form a signaling network, playing a vital role in affecting the immune level [34]. In the current study, it was found that the serum IgA and IgM concentrations showed an increasing trend in PR2 lambs when compared with CON lambs. In a previous study in lambs, tannin supplementation increased IgA and IgM concentrations in the serum [16]. In addition to conventional nutrients, tannin also plays a significant role in the nutritional value of PG [35]. According to the previous study, tannin content ranges from 8% to 13% in the leaves of PG [35], which might explain this positive influence of mixed silage on immunoglobulins. Tannin can improve antibody production and accelerate leukocyte activity as well as cellular immune response, thereby increasing the IgA and IgM concentrations in the body in lambs. Moreover, serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels were lower in PR2 lambs than in CON lambs, which suggests that moderate amounts of PG and rice straw mixed silage can improve the immune response in fattening lambs, thus reducing the damage of the inflammatory response to the body. A recent research study found that diet supplementation with PG can decrease the levels of pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-6 and IL-1β, and increase the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors, thus improving the immune response in goats [12], which is in accordance with the findings of this experiment. Microorganisms including Lactobacillus and Bacteroidetes can stimulate the activity of dendritic cells and macrophages to regulate the production of inflammatory factors [36]. The improvement in the immune response could be attributed to the effects of mixed silage on the gut microbiota.

4.6. Effects of Maize Silage Replaced with Mixed Silage on Serum Antioxidant Capacity in Lambs

In the modern production of fattening lambs, intensive farming easily leads to oxidative stress and reduces immunity in lambs [13]. Our results indicate that dietary supplementation with PG and rice straw mixed silage can improve antioxidant ability in fattening lambs. Consistent with our findings, a recent research study in goats reported that PG can eliminate reactive oxygen species in the body and increase the serum activity of GSH-Px and CAT, which was conducive to protecting the body from oxidative damage, reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory factors and increasing the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors [12]. The positive effects of PG on antioxidative capacity might be associated with the antioxidant properties of selenium and polyphenol substances naturally found in PG. According to a previous analysis, the selenium content in PG is approximately 0.13 mg/kg, and the flavone and ferulic acid contents are approximately 500 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg, respectively [9]. Selenium can neutralize free radicals to reduce oxidative damage, and polyphenol is an important component in plants that can exert antioxidant effects by scavenging free radicals and activating antioxidant enzyme systems [37]. Dietary supplementation with selenium yeast can increase serum GSH-Px and T-AOC activity, thus improving antioxidant capacity in sheep [38], which is basically consistent with our study. Unfortunately, we did not analyze the selenium and polyphenol contents in PG and rice straw mixed silage. In the future, the accurate contents of these ingredients in PG silage will need to be studied. Additionally, MDA is a critical oxidative stress indicator that can damage the integrity of cells and reflect the degree of damage to cells and tissues [39]. Meat quality, such as meat tenderness and odor, will be reduced in ruminants which are exposed to oxidative stress [40]. Improved antioxidant status in lambs induced by PG and rice straw mixed silage may benefit meat quality, as oxidative stress has been associated with reduced tenderness and off-flavors in lamb meat; however, this warrants direct evaluation in future studies.

5. Conclusions

The findings obtained from this study indicate that replacing maize silage with mixed silage prepared with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw in a 50% proportion in the diet does not have a significant influence on ADG, ruminal fermentation characteristics, apparent digestibility and serum biochemical parameters in fattening lambs. Additionally, the 50% replacement level improves immunity and antioxidant ability in lambs, which is mainly evidenced by increased IgA (trend) and reduced TNF-α, as well as increased CAT and T-AOC and reduced MDA concentrations in the serum. However, the 75% substitution ratio shows decreased ADG, nutrient digestibility and serum GLU concentration and increased ruminal NH3-N and serum UN contents. These findings support our hypothesis that moderate replacement (50%) of maize silage with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw mixed silage can maintain performance and improve antioxidant status in fattening lambs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F., B.W., W.Z. and J.M.; methodology, W.X. and S.W.; software, W.X. and Y.L.; validation, L.L., W.Z. and J.M.; formal analysis, Y.F. and B.W.; investigation, Y.F., B.W., W.X., S.W., L.F., Y.L. and L.L.; resources, W.Z. and J.M.; data curation, Y.F., B.W. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F. and B.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.F., B.W. and J.M.; visualization, Y.F., B.W., W.X., S.W. and L.F.; supervision, W.Z. and J.M.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was funded by the Innovative Training Program for College Students (CXXL2025058), the Program for Scientific Research Start-upfunds of Guangdong Ocean University (060302052318) and the Guangdong Feed Industry Technology System (2024CXTD14).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangdong Ocean University (Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China; Approval Code: SYXK-2024-104).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, R.; Wu, D.; Dai, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Mao, H.; Li, Q. Responses of nutrient utilization, rumen fermentation and microorganisms to different roughage of dairy Buffaloes. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Meng, X.; Zhao, P.; Liu, B.; Xu, H.; Li, F.; Li, F. Dietary Non-forage fiber sources and starch levels: Effects on growth, meat fatty acid composition, and rumen bacterial community of fattening lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 324, 116340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Dong, M.; Wang, J. Effects of substituting sweet sorghum for corn silage in the diet on the growth performance, meat quality, and rumen microorganisms of Boer goats in China. Animals 2025, 15, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorati, L.; Boselli, L.; Pirlo, G.; Moschini, M.; Masoero, F. Corn silage replacement with barley silage in dairy cows’ diet does not change milk quality, cheese quality and yield. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3396–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Fan, X.; Sun, G.; Yin, F.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, Z.; Gan, S. Replacing alfalfa hay with amaranth hay: Effects on production performance, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestibility and antioxidant ability in dairy cow. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, A.M.N.; da Silva, C.S.; Gama, M.A.S.; Soares, L.F.P.; de Souza, A.F.; Siqueira, M.C.B.; de Vasconcelos, E.Q.L.; Galeano, V.J.L.; Mora-Luna, R.E.; Santos, T.V.M.; et al. Feeding cactus (Opuntia stricta [Haw.] Haw.) cladodes as a partial substitute for elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schum.) induces beneficial changes in milk fatty acid composition of dairy goats fed full-fat corn germ. Dairy 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, Q.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, J. Adding rumen microorganisms to improve fermentation quality, enzymatic efficiency, and microbial communities of hybrid Pennisetum silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 410, 131272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Li, R. Effects of different cutting heights on the quality of hay and silage of Pennisetum giganteum. Feed Res. 2016, 5, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, C. Comparative analysis of nutritional components of Pennisetum giganteum at different growth heights in hill regions of central Sichuan. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 33, 5313–5323. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Bao, J.; Zhuo, X.; Li, Y.; Zhan, W.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z. Effects of Lentilactobacillus buchneri and chemical additives on fermentation profile, chemical composition, and nutrient digestibility of high-moisture corn silage. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1296392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lin, L.; Lu, Y.; Weng, B.; Feng, Y.; Du, C.; Wei, C.; Gao, R.; Gan, S. The influence of silage additives supplementation on chemical composition, aerobic stability, and in vitro digestibility in silage mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and rice straw. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhao, H.; He, X.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, F.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q. Effects of fermented feed of Pennisetum giganteum on growth performance, oxidative stress, immunity and gastrointestinal microflora of Boer goats under thermal stress. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1030262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Ren, C.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y. Review of feeding systems affecting production, carcass attributes, and meat quality of ovine and caprine species. Life 2023, 13, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NY/T 816-2021; Nutrient Requirements of Meat-Type Sheep and Goats. China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Lin, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Luo, W.; Li, T.; Cao, G.; Du, C.; Wei, C.; Yin, F.; Gan, S.; et al. The influence of high-concentrate diet supplemented with tannin on growth performance, rumen fermentation, and antioxidant ability of fattening lambs. Animals 2024, 14, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Sharma, O.P.; Dawra, R.K.; Negi, S.S. Simple determination of microbial protein in rumen liquor. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 2170–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official Methods of Analysis; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Feng, H.; Zhou, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, T.; Tang, Z. The effects of replacing whole-crop corn silage with hybrid acacia silage and giant foxtail grass silage on the growth performance and serum biochemical indicators of mutton sheep. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 57, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Huhtanen, P.; Cabezas-García, E.H.; Krizsan, S.J.; Shingfield, K.J. Evaluation of between-cow variation in milk urea and rumen ammonia nitrogen concentrations and the association with nitrogen utilization and diet digestibility in lactating cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 3182–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naji-Zavareh, M.R.; Hashemzadeh, F.; Alikhani, M.; Khorvash, M.; Kahyani, A.; Ahmadi, F. Effects of replacing alfalfa hay with barley silage in high-concentrate diets: Chewing behavior, ruminal fermentation, total-tract digestibility, and milk production of dairy cows in mid-lactation phase. Anim. Res. One Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Ge, G.; Jia, Y.; Du, S. Effects of different forage proportions in fermented total mixed ration on muscle fatty acid profile and rumen microbiota in lambs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1197059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Guo, X.J.; Xu, L.N.; Shao, L.W.; Zhu, B.C.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.J.; Gao, K.Y. Effect of whole-plant corn silage treated with lignocellulose-degrading bacteria on growth performance, rumen fermentation, and rumen microflora in sheep. Animal 2022, 16, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, E.; Chwialkowska, J.; Stodolny, M.; Oleskowicz, P.P. Volatile fatty acids production during mixed culture fermentation—The impact of substrate complexity and PH. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gäbel, G.; Sehested, J. SCFA transport in the forestomach of ruminants. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 1997, 118, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahiha, P.; Mirzaei-Alamouti, H.; Kazemi-Bonchenari, M.; Aschenbach, J.R. Growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and ruminal fermentation of dairy calves fed starter diets with alfalfa hay versus corn silage as forage and soybean oil versus palm fatty acids as fat source. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9597–9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atuhaire, A.M.; Kabi, F.; Okello, S.; Mugerwa, S.; Ebong, C. Optimizing Bio-physical conditions and pre-treatment options for breaking lignin barrier of maize stover feed using white rot Fungi. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Khan, M.; Sufyan, A.; Saeed, A.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Nazar, M.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S. Biotechnological processing of sugarcane bagasse through solid-state fermentation with white rot fungi into nutritionally rich and digestible ruminant feed. Fermentation 2024, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; Hu, R.; Wang, X.; Cao, G.; Zou, H.; Shah, A.M.; Peng, Q.; et al. Glutamine supplementation affected the gut bacterial community and fermentation leading to improved nutrient digestibility in growth-retarded yaks. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fifiab084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousiainen, J.; Shingfield, K.J.; Huhtanen, P. Evaluation of milk urea nitrogen as a diagnostic of protein feeding. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Rouzbehan, Y.; Zahedifar, M.; Fazaeli, H. Effects of dietary substitution of maize silage by amaranth silage on feed intake, digestibility, microbial nitrogen, blood parameters, milk production and nitrogen retention in lactating Holstein cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 202, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, D.; Yao, J.; Cao, Y.; Deng, L. Hepatic gluconeogenesis and regulatorymechanisms in lactating ruminants: A literaturereview. Anim. Res. One Health. 2025, 3, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.S.; Ma, B.Y.; Gao, Z.H.; Wu, Z.L.; Qu, Y.A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, S.Z.; Gui, L.S. Supplementing exogenous xylanase improves the liver antioxidant capacity and immune response of Tibetan sheep fed wheat-based diets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Rao, R.; Huang, W.; Deng, B.; Yang, X. Analysis of nutritional components and tannin content of Pennisetum giganteum at different growth heights. Grain Oil Feed Technol. 2024, 6, 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, M.; Kumar, P.; Laddha, N.C.; Helen, K.E. Induction of regulatory T cells: A role for probiotics and prebiotics to suppress autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities in selected drought-tolerant leafy vegetable amaranth. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Cui, X.; Chang, S.; Xiao, X.; Yan, T.; Wang, H.; Hou, F. Effect of different levels of selenium yeast on the antioxidant status, nutrient digestibility, selenium balances and nitrogen metabolism of Tibetan sheep in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 180, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Qi, M.; Zhou, Y. Chestnut tannin extract modulates growth performance and fatty acid composition in finishing Tan lambs by regulating blood antioxidant capacity, rumen fermentation, and biohydrogenation. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, K.; Mingbin, L.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, B. Effects of chestnut tannins on the meat quality, welfare, and antioxidant status of heat-stressed lambs. Meat Sci. 2016, 116, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.