Abstract

Climate change exacerbates soil moisture deficits, necessitating efficient water retention strategies. Superabsorbent polymers (SAPs) offer a potential solution to enhance water availability for crops during dry periods. Faba bean (Vicia faba L.) and pea (Pisum sativum L.) were selected as model legumes due to their high nutritional value, agricultural importance in temperate regions, and sensitivity to drought stress This study evaluated the effects of different SAP application rates on the yield and physiological performance of two legume species: faba bean (cv. Granit) and pea (cv. Batuta). The two-year (2017–2018) field experiments employed a randomized block design with four replicates. Treatments included three SAP doses: 0 (control, SAP0), 20 (SAP20) and 30 (SAP30) kg·ha−1. The study was conducted over two years with contrasting weather: 2017 was wetter but had uneven rainfall distribution, while 2018 was drier and characterized by moisture deficits during critical growth stages. SAP application significantly increased seed yield in faba bean and pea, with the most favorable effect observed at 20 kg ha (average yield increase of 23.6% and 17.3%, respectively). SAP did not affect yield components in faba bean. However, in peas, an increase in pod number and seed number per plant was observed with the SAP30 dose compared to the SAP20 dose. Application of superabsorbent at a dose of 20 kg ha−1 significantly increased photosynthesis rate in faba bean, the Fv/Fm index in the tested species, and the PI in peas compared to the control. However, the superabsorbent did not affect transpiration rate or the WUE coefficient in the tested legume species. Significantly higher yields in faba bean and pea and all tested plant structure parameters in pea were recorded in 2018 compared to 2017. The tested parameters of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence were higher in pea in 2018 (except for transpiration intensity) and in faba bean in 2017. The findings suggest that SAPs can be a useful tool to mitigate water stress effects in legumes, although their effectiveness depends on environmental conditions. Therefore, SAP application may be a promising agronomic strategy in regions prone to irregular rainfall or moderate drought.

1. Introduction

Plant production, as the first level of agricultural activity, provides raw materials not only for direct consumption but also for the production of animal feed. In the face of a growing population, changing climatic conditions and limited natural resources, ensuring stable sources of protein is becoming one of the most important challenges of modern agriculture [1].

Legumes play an important role in food and agricultural systems. Their seeds are high in protein, making them a valuable component of both human and animal diets. In addition, these plants have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen through symbiosis with nodule bacteria, which improves soil fertility and reduces the need for mineral nitrogen [2,3]. In the context of feed protein deficits in European Union countries, including Poland, legumes are a potential alternative to imported soybean meal, more than 90% of which comes from genetically modified plants [4]. Increasing the productivity and stability of local protein crops such as pea and faba bean is of strategic importance. Identifying agronomic practices, such as the application of superabsorbent polymers, that enhance yield under water-limited conditions supports the effort to reduce dependence on imports and improve feed protein self-sufficiency.

Despite their high utility value, legumes exhibit high yield variability, which results from their sensitivity to weather factors, especially water deficit which can significantly reduce their productivity. As climate-related drought events become more frequent, water availability has become a key constraint in legume production [5]. Soil water deficiency causes disturbances in basic physiological processes, changes in metabolism and nutrient distribution, and reduced biomass production [6]. The main mechanism of plant growth is photosynthesis, which is inhibited and disrupted as a result of drought [7,8]. Proper photosynthesis and the transport and distribution of assimilates determine plant growth and agricultural yield, which is the end result of the processes occurring in the plant. Under conditions of water deficit, plant cells do not elongate naturally and terminate their growth prematurely. In the initial stage of drought, plants activate defense mechanisms by closing their stomata, which reduces transpiration but also limits CO2 uptake, thereby inhibiting photosynthesis. However, under conditions of prolonged stress, more serious disturbances in cellular metabolism occur, although the response of individual plant species to stress is not uniform. This depends on the degree of protoplast shrinkage during cell dehydration and the ability to efficiently and reversibly rehydrate, which we observe in drought-resistant plants [9].

The inhibition and disruption of photosynthesis causes plant dysfunction, which is of great diagnostic value and can be one of the ways to assess a plant’s response to stress. Since water deficit is a primary factor affecting photosynthetic efficiency, understanding and managing water use becomes critical. Therefore, optimizing water use is a key factor in achieving productivity goals within sustainable production systems [1].

During water stress, the photosystem may be damaged, especially photosystem II (PSII), and cause changes in chlorophyll a fluorescence [9,10]. According to Kalaji et al. [11], chlorophyll fluorescence is a measure of the state and condition of the photosynthetic apparatus. Chlorophyll a fluorescence is emitted from healthy leaves and comes almost exclusively from chlorophyll a molecules located mainly in photosystem II (PSII), and is therefore an indicator of its function [12]. The measurement of chlorophyll a fluorescence can therefore be a good indicator of the impact of stress factors on the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus and the health and vitality of the plant [13]. The use of fluorometric methods allows recording very early changes occurring in PSII in response to a stress factor, often even before other symptoms appear [14].

One promising solution for limiting the effects of drought in legume cultivation is the use of superabsorbents (SAPs). These are polymers with a high-water retention capacity which, when introduced into the soil, improve its water capacity, reduce moisture loss and improve water availability for plants [1,6]. Studies show that SAPs can significantly improve photosynthesis parameters, chlorophyll content and water use efficiency in legumes under water stress conditions [15,16]. For instance, in drought-stressed common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), SAP application in dose 75 kg ha−1 increased net photosynthetic rate by 42%, stomatal conductance by 55%, and SPAD chlorophyll content by 17% [15]. These findings demonstrate the physiological relevance of SAP under water-limited conditions in legumes. Their use supports the functioning of PSII, stabilizes cellular metabolism and increases plant resistance to drought, which translates into higher yields and better-quality raw materials. However, results remain inconsistent and highly dependent on environmental conditions, crop species, and application rates.

Despite numerous studies confirming the general benefits of SAPs under drought conditions, there remains a limited understanding of how different doses of SAPs affect yield and physiological responses in legumes under field conditions.

Due to their high protein content, favorable amino acid composition, and considerable feed value, faba bean and pea are important legume crops in temperate agriculture. However, their susceptibility to drought often leads to yield instability under unfavorable conditions, making them suitable model species for evaluating the effectiveness of superabsorbent under variable moisture regimes. Therefore, the aim of the study was to determine the effects of various doses of superabsorbent on yield performance and physiological traits of peas and faba bean under different environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Soil Properties

The research was conducted on the basis of two field experiments carried out at the Agricultural Experimental Station belonging to the Institute of Soil Science and Plant Cultivation—State Research Institute in Puławy, located in Grabów nad Wisłą (Masovian voivodeship). The experiments were conducted on loamy soil, formed on light clay—class IIIb, IVa. The soil pHKCl ranged between 5.3 and 6.0. The content of available forms of macronutrients ranged as follows (mg·100 g−1 soil): P—12.9–19.3; K—10.6–13.4; Mg—4.7–9.8. The organic carbon content was 0.76–0.80%. The experiment was conducted over two years in different locations but on a single experimental field. The plots were located close to each other, eliminating the influence of different soil conditions on the parameters studied.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

The two-year experiments were set up in a randomized block design, with 4 replicates. The experimental factor was the rate of hydrogel, also known as superabsorbent—0-control treatment (SAP0), 20 kg·ha−1 (SAP20) and 30 kg·ha−1 (SAP30). In the first experiment, the crop species was Vicia faba L. cultivar Granit, and in the second experiment, Pisum sativum L. cultivar Batuta (narrow-leaved). The pea seeds came from DANKO-plant breeding and the faba bean seeds from Strzelce-plant breeding. The area of the experimental units was 30 m2 (3 × 10 m).

2.3. Crop Management

The preceding crop for all species was spring barley. Pre-sowing phosphorus and potassium fertilization was applied in the form of triple superphosphate (40% P2O5, 10% CaO) at a dose of 125 kg∙ha−1 and potassium salt (60% K2O) at a dose of 150 kg∙ha−1. Nitrogen fertilization was not applied. Potassium-based cross-linked acrylic polymer ‘Terra hydrogel Aqua’ (SAP) was used (with the parameters presented in Table 1), which was mixed with the soil using a passive cultivation unit to a depth of 15 cm. SAP sowing was carried out each year immediately before sowing the seeds. Before sowing, the seeds were treated with a fungicide (Funaben T—200 g·100 kg−1 of seeds). Seeds were sown at a depth of 8–10 cm for faba bean and 5–8 cm for peas, with a spacing of 24 cm. Sowing of pea and faba bean seeds in the first year was carried out on 5 April 2017, and in the second year on 20 April 2018.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the superabsorbent Terra hydrogel Aqua.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Yield and Yield Components

Before harvesting (BBCH 89), 10 plants were randomly selected from each treatment to determine the biometric characteristics of the plants, which included the following: number of pods per plant, number of seeds per plant, seed weight per plant (g), thousand seed weight TSW (g).

Seed yield (t·ha−1) was determined at full maturity, at 14% seed moisture content. Seed moisture content was determined using Seed Moisture Meters—SM 10 (FOSS, Hilleroed, Denmark).

2.4.2. Plant Density and Weather Data

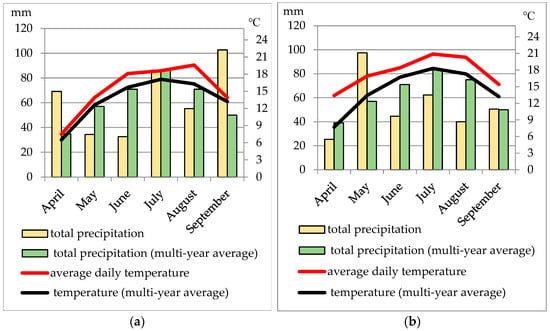

Weather conditions varied during the years (2017–2018) of the study (Figure 1). Comparing the thermal conditions during the years of the experiment, it was found that the average monthly temperature during the growing season was higher in 2018 than in 2017. The average monthly air temperature during this period in 2017 and 2018 was higher, compared to the long-term averages (1871–2000). The total precipitation during the growing season in 2017 was 380.6 mm, being the closest to the long-term average (376 mm). The year 2018 was deficient in terms of precipitation (320.1 mm).

Figure 1.

Weather conditions during the study years (a) 2017 and (b) 2018 (data origin: IUNG-PIB experimental station in Grabów).

The characteristics of thermal and precipitation conditions in the two analyzed growing seasons were described using Selianinov’s Hydrothermal Coefficient [17], also known as the water security coefficient or conventional moisture balance (Table 2). The index (k) defines the ratio of total precipitation to the sum of average daily air temperatures in a given period.

where

k = (10∙P)/(∑t)

Table 2.

Characteristics of three growing seasons based on Selianinov’s hydrothermal index (k).

P—monthly total precipitation (mm),

Ʃt—sum of average daily temperatures in a given month > 0 °C.

After the plants emerged, the plant density (plants per m−1) was calculated for each treatment, which averaged over the years for faba bean as follows: SAP0—35.5, SAP20—45.7, SAP30—46.2. For peas, the values are as follows: SAP0—63.9, SAP20—68.8, SAP30—57.7.

2.4.3. Physiological Measurements

During the growing season, observations of the developmental stages of individual legume species were carried out according to Bleiholder et al. [18]. In selected developmental stages (BBCH—Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt i Chemical Industry), measurements were taken of the intensity of basic gas exchange processes (photosynthesis, transpiration), chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm, PI) and leaf greenness index (SPAD) were measured. In faba beans, measurements were carried out in BBCH stages: 60—first flowers open; 65—full flowering, flowers open on 5 inflorescence racemes; 70—first pods reach typical length; 75—50% of pods reach typical length; 82—20% of ripe and dark pods. In peas, measurements were carried out in BBCH stages, 51—the beginning of the first flower bud is visible outside the leaves, 67—final flowering stage, most of the petals have fallen and dried, 75—50% of the pods have reached their typical length, 82—20% of the pods are mature, seeds are of typical color, dry and hard. The measurements were taken on the second fully developed leaf, in the middle part of the leaf blade.

The photosynthetic efficiency of pea and faba bean leaves was assessed on the basis of measurements of net photosynthesis (PN) [μmol CO2 m−2·s−1] and transpiration intensity (E) [mmol H2O m−2·s−1], performed with a portable CIRAS-2 device (PP-Systems Company, Amesbury, MA, USA). The measurements were performed in four replicates, at constant PAR radiation intensity parameters—1200 µmol·m−2·s−1, CO2—390 ppm (µmol CO2·mol−1) of air) and a temperature ranging from 20 to 27 °C. Based on the instantaneous values of photosynthesis and transpiration, the photosynthetic water use efficiency (WUE) was calculated according to the formula WUE = PN/E [19,20].

Direct chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements were performed using a non-invasive (in vivo) method with a PocketPEA fluorometer (Hansatech Instruments—WB, King’s Lynn, Norfolk, UK). Two indicators were assessed: Fv/Fm (maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II) and PI (photosystem II performance index). Chlorophyll fluorescence indices were used to determine the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and to assess the physiological state of plants. The measurements were carried out after 20 min of leaf adaptation in the dark, in 9 repetitions.

Leaf greenness index (SPAD) measurements were performed using a chlorophyll meter. The result is given in digital form, in so-called SPAD (soil and plant analysis development) units, ranging from 0 to 800 (N-Tester units). The value of the reading is proportional to the chlorophyll content in the tested leaf area (6 mm2). The measurements were performed in 4 repetitions (one repetition as the average of 30 measurements).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The collected research results were statistically analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the Statgraphics Centurion XVI program (version 16.1.11). To compare the differences between the means for the factors, a multiple confidence interval test (Tukey’s test) was used at a significance level of α = 0.05. For the parameters of gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and SPAD index, the mean of all measurements in the developmental phases in individual years was presented. Correlations between yield and gas exchange indices, chlorophyll fluorescence and SPAD index were sought and presented in the form of simple correlation coefficients (Pearson’s coefficient).

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Photosynthetic Efficiency in Peas

The results of the study showed that the SAP dose significantly affected the pea seed yield (Table 3). A significantly higher number of pods and seeds per plant was recorded on the SAP30 treatment compared to SAP20 but did not differ significantly compared to the control. Taking into account the average values, the use of superabsorbent significantly increased the pea yield by approximately 17% at the SAP20 treatment and by 20% at the SAP30 treatment compared to the control. The examined yield and plant structure characteristics varied significantly over the years of the study. All the examined parameters of the yield and structure of peas were significantly higher in 2018. No interaction between the experimental factors and their effect on the examined yield and structure traits was found.

Table 3.

Pea yield and its structure depending on the SAP dose and year of study.

The SAP dose differentiated the rate of photosynthesis and the maximum photosystem II efficiency index (Fv/Fm) in pea (Table 4). The rate of photosynthesis was significantly lower at the SAP20 treatment compared to the other treatments, while the Fv/Fm index was significantly higher at the SAP20 treatment compared to the control and the SAP30 treatment.

Table 4.

Gas exchange indices in peas depending on the SAP dose and year of study.

The parameters studied varied between the years of the study (except for the SPAD index). Transpiration rate was significantly higher in 2017 than in the following year (by 50%). Photosynthesis rate, WUE, Fv/Fm and PI indices were significantly higher in the second year of the study (by 28, 97, 4 and 52%, respectively), compared to 2017.

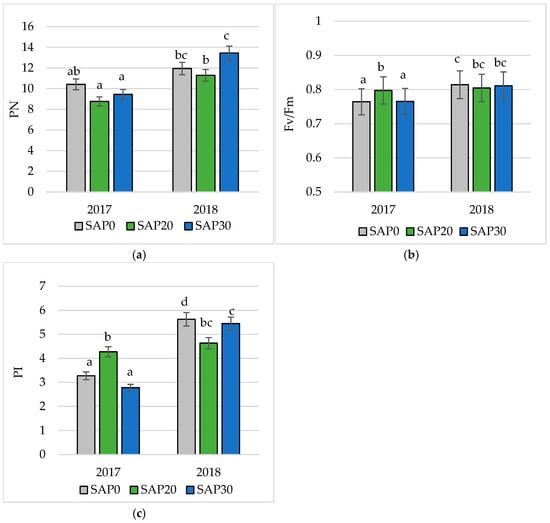

Interactions between experimental factors and their impact on photosynthesis rate and chlorophyll fluorescence indices were also demonstrated (Figure 2). The application of hydrogel at the SAP30 treatment in 2018 significantly increased photosynthetic rate compared to the SAP20 treatment. The PSII maximum efficiency index (Fv/Fm) was significantly higher at the SAP20 treatment in 2017 compared to the control treatment and the SAP30 treatment. In contrast, the photosystem II performance index (PI) in 2017 was significantly higher on the SAP20 treatment compared to the SAP0 and SAP30 treatments. In the following year, a significantly higher value of this parameter was recorded on the control treatment compared to the treatments where superabsorbent was applied.

Figure 2.

Interaction of experimental factors and its effect on photosynthesis intensity (μmol CO2 m−2·s−1) (a) and chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm—(b), PI—(c)) in peas (means followed by different letters are significantly different).

Highly significant positive correlations were found between yield and photosynthesis rate, WUE coefficient, chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm and PI), and weak significant correlations between yield and the number of pods per plant and seed weight per plant in peas (Table 5). A strong, negative correlation was found between yield and transpiration rate. Significant correlations were found between yield components and gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence indices. The number of pods per plant and seed weight per plant were weakly and significantly correlated with the WUE coefficient and the Fv/Fm index, and the seed weight per plant also correlated with the PI. A weak significant negative relationship was demonstrated between transpiration rate and the number of pods and seed weight per plant. Significant relationships were demonstrated between TSW and transpiration rate and the chlorophyll fluorescence indices Fv/Fm and PI.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between the physiological characteristics of peas and yield and its structure.

3.2. Yield and Photosynthetic Efficiency in Faba Bean

The results of the study showed that the SAP dose and the year of the study did not significantly affect the studied yield structure parameters, i.e., the number of pods per plant, the number of seeds per plant, the weight of seeds and thousand seed weight in faba bean (Table 6). However, a significant increase in the yield of faba bean was observed after the application of the superabsorbent. On the SAP20 and SAP30 treatments, the yield increased by 24% and 30%, respectively, compared to the control treatment. The year of the study also significantly modified the faba bean seed yield. Significantly higher yields (by about 60%) were recorded in 2018. No interaction between the experimental factors and their impact on the studied yield characteristics and structure was found.

Table 6.

Faba bean yield and its structure depending on SAP dose and year of study.

The SAP dose significantly affected the parameters of photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in faba bean (Table 7). When SAP was applied at a dose of 20 kg ha−1, the rate of photosynthesis and the chlorophyll fluorescence indices Fv/Fm and PI were significantly higher compared to the control and SAP30.

Table 7.

Gas exchange indices in faba beans depending on the SAP dose and year of study.

The year of research significantly differentiated almost all parameters studied (except for WUE). In 2017, photosynthesis and transpiration rate, as well as Fv/Fm and PI indices, were significantly higher compared to 2018. In contrast, the opposite was found for the SPAD index. Significantly higher SPAD values were recorded in 2018 compared to 2017. No interaction between the experimental factors and their effect on the studied parameters of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence was found.

The analysis of the interdependence between the studied characteristics of faba bean is presented in Table 8. A significant positive correlation was found between yield and the WUE coefficient and the SPAD index, and a negative correlation was found between yield and transpiration rate and the chlorophyll fluorescence indices Fv/Fm and PI. The correlations between yield components and gas exchange indices (photosynthesis and transpiration rates), chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm and PI), and leaf greenness index (SPAD) were statistically insignificant.

Table 8.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between the physiological characteristics of faba bean plants and yield and its structure.

4. Discussion

4.1. Yield Responses to SAP and Environmental Modulation

The weather conditions during the 2017–2018 growing seasons were varied and had a significant impact on plant productivity. During the growing seasons in which the research was conducted, rainfall was very irregular. Often, there was heavy rainfall (even up to around 50.0 mm) lasting 2–3 days in a single decade, but the excess water did not seep into the soil profile and instead ran off the fields. As a result, there was a water shortage, which was more related to the uneven distribution of rainfall than to the total rainfall during the growing season. According to the Selianinov index (Table 1), May 2017 was dry and June was very dry, while April 2018 was very dry and June was dry. Thus, during the months when legumes are at their most critical stage in terms of water demand, there was a drought.

Significantly higher yields of faba bean and pea (by 60.1% and 37.7%, respectively) and all tested plant structure parameters in pea were recorded in 2018 compared to 2017. The tested parameters of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence were higher in pea in 2018 (except for transpiration rate) and in faba bean in 2017.

The reduction in seed yield due to soil water deficiency depends on the intensity and duration of stress, as well as the plant species and its growth stage [21]. The use of superabsorbent improves soil moisture conditions by supplying stored water to plants during dry periods, thus reducing the risk of drought stress, which can affect crop yields. However, for the hydrogel to be effective, regular rainfall is required to allow water to be absorbed and then made available to plants. The results of our own research showed a significant impact of the use of superabsorbent on the yield of the tested species. In faba bean and pea, an increase in seed yield was observed after the application of hydrogel, with the most beneficial being the use of SAP at a dose of 20 kg ha−1 (average yield increase of 23.6% and 17.3%, respectively). The hydrogel rates used did not differentiate the elements shaping the seed yield in faba beans. In pea, however, an increase in the number of pods and seeds per plant was observed when using the SAP30 dose compared to the SAP20 dose (by 18.3% and 25.9%, respectively). Significantly lower yields and yield structure parameters in peas in 2017 may have been influenced by rainfall deficits in May and June, which were lower than the long-term average, by 40% and 54%, respectively. Adequate soil moisture during these months is crucial for legumes, and despite higher rainfall during the 2017 growing season, yield levels were determined by the distribution of rainfall during specific stages of development. The increase in yield on the treatments where SAP was applied was probably related to the plant density, which was higher on the SAP20 and SAP30 treatments (by 29% and 30%, respectively) compared to the control. According to Mandić et al. [22], water deficit during the pod formation and seed production stages causes a greater yield decline than water shortage during the flowering stage. Furthermore, applying SAP to heavy soils increases and facilitates air access to roots. It also improves nutrient utilization by reducing nutrient leaching. As a result, plants experience more favorable growth conditions and are less susceptible to environmental stress, which could have influenced the growth of the studied traits after SAP application. Various authors report a positive effect of hydrogel on legume seed yield. Shankarappa et al. [23] obtained an increase in lentil (Lens culinaris) seed yield of over 50% compared to the control after applying hydrogel at a rate of 5 kg·ha−1. Pouresmaeil et al. [24] showed that the application of a superabsorbent in an amount of 7.5% of soil weight increased the yield of red beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) by 38.5% compared to the control, where no hydrogel was used. In a pot experiment conducted by Księżak [25], the use of hydrogel resulted in a significant increase in the weight of faba bean seeds (by 14.1% on average) and the weight of thousand seeds compared to the control. In turn, field studies conducted in India on the use of superabsorbent in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) cultivation showed a significant increase in seed yield after the application of SAP at a dose of 7.5 and 10 kg·ha−1, by 34.3 and 33.6%, respectively, compared to the control [26]. Yazdani et al. [27] obtained 31.7% higher soybean seed yields, but after applying superabsorbent in a very high dose (225 kg·ha−1) compared to the control. However, these results are not confirmed by the studies of Panasiewicz et al. [28]. These authors found that the application of hydrogel at a rate of 30 and 60 kg·ha−1 had no significant effect on the yield of peas. No significant effect of SAP on selected parameters of sowing value and vigor of pea seeds was demonstrated either. In studies by Faligowska and Szukała [29,30], the use of polymer did not increase soybean yields, despite a significant increase in the number of pods per plant compared to the control where SAP was not used. They also found no significant effect of varying rates of SAP on pea seed yields. In contrast, in the studies by Pouresmaeil et al. [24], the use of superabsorbent in an amount of 0.7% of soil mass increased the weight of thousand red bean seeds by 21.2% compared to the control, where no hydrogel was used. The varying research results regarding the effect of SAP on plant yield growth and improved plant structure can be difficult to clearly explain, as they depend on numerous environmental and soil factors. The effectiveness of polymers depends on many factors, including the amount and distribution of rainfall, soil type, its nutrient content, and the plant species. In practice, SAP can improve water retention and nutrient availability, but other factors can mask this effect. Therefore, field study results are often varied and do not always allow for a straightforward interpretation of SAP’s impact on yield.

4.2. Physiological Mechanisms: Divergent Pathways in Pea and Faba Bean

Basic physiological processes such as photosynthesis, transpiration and chlorophyll fluorescence have a decisive influence on crop yields. Disturbances in the course of these processes in individual species can help determine the extent to which a stress factor has limited the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus. Proper plant growth and development is possible thanks to the availability of water and carbon dioxide, which are substrates in the process of photosynthesis. Therefore, photosynthesis and transpiration are important processes that have a direct impact on biomass growth and, consequently, on the productivity of crops [31]. The Fv/Fm index determines the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II and allows for the detection of PSII damage and possible photoinhibition [32]. According to DeEll et al. [33], the Fv/Fm ratio should be in the range of 0.75–0.85, and a decrease in this ratio may indicate damage and limitations in PSII function. Another important chlorophyll fluorescence index that describes the amount of effective energy converted by photosystem II is the PSII performance index (PI). This index expresses the plant’s ability to defend itself against stress [11].

In our own studies, gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in faba beans were significantly higher in 2017 compared to 2018, while in pea, photosynthesis rate, water use efficiency (WUE) and Fv/Fm and PI indices were significantly higher in 2018, which also correlated with higher seed yield in that year. Interpreting the impact of drought on photosynthesis and transpiration rates is difficult because plant responses are complex and dependent on numerous factors. Drought affects not only water availability but also the opening and closing of stomata, the activity of photosynthetic enzymes, and leaf structure. Faba beans and peas respond differently to drought because of their distinct species characteristics and physiology. Faba beans have deeper and more extensive root systems, allowing them to better utilize water from deeper soil layers and maintain photosynthetic activity for longer. Peas, on the other hand, have shallower roots, which means they experience water stress more quickly and reduce transpiration and photosynthesis more quickly. Furthermore, the two species differ in leaf structure and stomatal regulation mechanisms, which causes their responses to water stress to differ and leads to varying results in studies. The application of hydrogel at a dose of 20 kg ha−1 increased the photosynthetic rate in faba bean by 18.5% compared to the control object, while pea reacted in the opposite way and, at the same rate, the photosynthetic rate was significantly lower compared to the other treatments. However, the superabsorbent did not affect the transpiration rate and WUE coefficient of the legume species studied. The application of superabsorbent at a dose of 20 kg ha−1 significantly increased the Fv/Fm index in the species studied and the PI in pea compared to the control. Similar results were observed by Pereira et al. [34], who also obtained varied results regarding the use of the polymer in field cultivation of soybeans. In one year of research, the authors noted reductions in photosynthesis and transpiration rate after the application of SAP, and in the following year, a positive effect of the polymer on these parameters. According to the authors, the use of superabsorbent under conditions of severe stress has no effect on the yield and efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus of soybeans, and its use is only justified under conditions of moderate stress and uniform rainfall. In our own studies, rainfall distribution was irregular; therefore, the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and plant productivity were more dependent on climatic and soil conditions than on the superabsorbent used. Taking into account the interactions of the experimental factors and their impact on chlorophyll fluorescence indices and photosynthesis rate, it was shown that chlorophyll fluorescence in peas in 2017 was highest at the SAP20 treatment, which indicates good PSII condition, while photosynthetic intensity at this treatment was the lowest, which may indicate lower photosynthetic efficiency caused by stomatal closure rather than damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, as also reported by Rehman et al. [35].

4.3. Chlorophyll Content and Comparison with Previous Studies

Plants respond to drought stress by changing the content of photosynthetic pigments [36]. Water deficit inhibits the synthesis of chlorophyll a and b and reduces the content of proteins responsible for its binding [37]. Our own research did not show a significant effect of superabsorbent on the leaf greenness index (SPAD) in faba bean and pea. Significantly higher values of this parameter were recorded in faba beans only in 2018 compared to 2017. These results may have been caused by irregular rainfall distribution and low hydrogel efficiency, as most results confirm that SAP effectively supports the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus by increasing leaf greenness index under water stress conditions. Youssef et al. [16] showed a significant increase in the greenness index of pea (Pisum sativum L.) leaves on treatments where hydrogel was applied at 0.7% of soil weight compared to treatments without hydrogel, both on treatments with optimal moisture and under water deficit conditions. Also, in studies conducted by Ahmed et al. [38], the application of superabsorbent to sandy soil significantly increased the SPAD index in green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) leaves compared to the control where no hydrogel was applied. The relative chlorophyll content in bean leaves increased with increasing SAP doses (from 0.1 to 0.9% of soil weight). In studies by Alotaibi et al. [39], the application of superabsorbent at a rate of 3 g/plant increased the chlorophyll content in green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv Bronco) leaves.

The results demonstrate that legume responses were strongly shaped by environmental conditions, particularly the distribution of rainfall during critical growth stages. Higher yields of both pea and faba bean in 2018 were associated with more favorable physiological performance, reflected in increased photosynthetic activity and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, especially in pea. The application of SAP improved selected physiological indicators, although its effects were species-specific and not consistent in years. In faba bean, SAP-induced yield increases occurred without clear changes in yield structure, suggesting that probably better rooting of the canopy played a greater role than changes in individual yield components. In contrast, in peas, under the influence of SAP there were increases in pod and seed number, indicating improved soil water availability in the reproductive phase. These findings imply that SAP can support legume production under conditions of irregular rainfall, but its practical effectiveness depends on species traits, environmental conditions, and severity of water stress, highlighting the need for further research.

5. Conclusions

The study showed that the yield and physiological activity of pea and faba bean varied significantly depending on the superabsorbent dose and weather conditions during the study years. The most beneficial application of SAP at a dose of 20 kg ha−1 significantly increased yield and the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II in pea and faba bean, the photosynthetic rate in faba bean, and the PI in pea. The superabsorbent did not affect transpiration rate, WUE, or SPAD in the studied legume species. Overall, the findings indicate that SAP primarily supports yield formation by improving early crop establishment and buffering plants against irregular water availability rather than by directly enhancing physiological efficiency. Therefore, the effectiveness of SAP in legume production should be considered context-dependent and closely related to environmental conditions, species characteristics, and initial plant density.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C. and M.S.; methodology, K.C. and M.S.; investigation, K.C.; resources, K.C.; data curation, K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; writing—review and editing, K.C. and M.S.; visualization, K.C.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Jerzy Księżak for providing access to the experimental site where the research was conducted. This support and the opportunity to use the experimental facilities significantly contributed to the completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| E | transpiration intensity |

| PN | photosynthesis intensity |

| Fv/Fm | maximum quantum efficiency of PSII |

| PI | PSII Performance Index |

| SY | seed yield |

| NP | number of pods per plant |

| NS | number of seeds per plant |

| WS | weight of seeds per plant |

| TSW | thousand seed weight |

References

- Adireddy, R.G.; Manna, S.; Patanjali, N.; Singh, A.; Dass, A.; Mahanta, D.; Singh, V.K. Unveiling Superabsorbent Hydrogels Efficacy Through Modified Agronomic Practices in Soybean–Wheat System Under Semi-Arid Regions of South Asia. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210, e12730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Li, J.; Yahya, M.; Sher, A.; Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, L. Research progress and perspective on drought stress in legumes: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawaha, A.R.M.; Alatrash, H.; Jabbour, Y.; Al-Tawaha, A.R.; Qaisi, A.M.; Jammal, R.; Karnwal, A.; Shatnawi, M.; Saranraj, P.; Rammal, J. Drought stress and sustainable legume production. In Marker-Assisted Breeding in Legumes for Drought Tolerance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, G.V.; Epure, L.I.; Toader, M.; Lombardi, A.R. Grain legumes—Main source of vegetal proteins for European consumption. Agrolife Sci. J. 2016, 5, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Florek, J.; Czerwińska-Kayzer, D.; Jerzak, M. Current state of production and use of leguminous crops. Fragm. Agron. 2012, 29, 45–55. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A. Effect of soil water deficit on growth and development of plants: A review. In Soil Water Deficit and Physiological Issues in Plants; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 393–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, B.; Ji, J. Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence images of soybean (Glycine max L.) seedlings. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniak, M.; Bojarszczuk, J.; Księżak, J. Changes in yield and gas exchange parameters in Festulolium and alfalfa grown in pure sowing and in mixture under drought stress. Acta Agric. Scand. 2018, 68, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, Z.; Chołuj, D.; Niemyska, B. Physiological Responses of Plants to Unfavorable Environmental Factors; Publisher SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 1995; pp. 27–47. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska, M. Reaction of selected meadow fescue and Timothy cultivars to water stress. Acta Sci. Pol. Agric. 2003, 2, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Jajoo, A.; Oukarroum, A.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M.; Samborska, I.A.; Cetner, M.D.; Łukasik, I.; Goltsev, V.; Ladle, R.J. Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Wi, S.; Chung, H.; Lee, H. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging for environmental stress diagnosis in crops. Sensors 2024, 24, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šesták, Z.; Šiffel, P. Leaf-age related differences in chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynthetica 1997, 33, 347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, A.I.; Zeller, A.K.; Pfündel, E.E.; Gerhards, R. Features and applications of a field imaging chlorophyll fluorometer to measure stress in agricultural plants. Precision Agric. 2021, 22, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkari, A. Effect of superabsorbent polymer on photosynthetic traits, chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence indices of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under drought stress. J. Plant Environ. Physiol. 2022, 17, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, S.; Riad, G.; Abu El-Azm, N.A.I.; Ahmed, E. Amending sandy soil with biochar or/and superabsorbent polymer mitigates the adverse effects of drought stress on green pea. Egypt. J. Hort. 2018, 45, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowera, B. Changes in hydrothermal conditions in Poland (1971–2010). Fragm. Agron. 2014, 31, 74–87. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bleiholder, H.; Buhr, L.; Feller, C.; Hack, H.; Hess, M.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Stauss, R.; van den Boom, T.; Weber, E.; et al. Compendium of growth stage identification keys for mono- and dicotyledonous plants. BASF 2011, 31–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Jiao, X.; Xu, J. Responses of rice yield, irrigation water requirement and water use efficiency to climate change in China: Historical simulation and future projections. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 146, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.; Qiao, Y.; Baodi, D.; Shi, C.; Liu, M. Effect of water stress on leaf level gas exchange capacity and water-use efficiency of wheat cultivars. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 21, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwarappa, S.G.; Salimath, P.M. Field screening of chickpea genotypes for drought resistance. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 21, 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mandić, V.; Krnjaja, V.; Tomić, Z.; Bijelić, Z.; Simić, A.; Đorđević, S.; Stanojković, A.; Gogić, M. Effect of water stress on soybean production. In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress “New Perspectives and Challenges of Sustainable Livestock Production”, Belgrade, Serbia, 7–9 October 2015; pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Shankarappa, S.K.; Muniyandi, S.J.; Chandrasheka, A.B.; Singh, A.K.; Nagabhushanaradhya, P.; Shivashankar, B.; El-Ansary, D.O.; Wani, S.H.; Elansary, H.O. Standardizing the hydrogel application rates and foliar nutrition for enhancing yield of lentil (Lens culinaris). Processes 2020, 8, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaeil, P.; Habibi, D.; Boojar, M.M.A. Yield and yield component quality of red bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars in response to water stress and super absorbent polymer application. Ann. Biol. Res. 2012, 3, 5701–5704. [Google Scholar]

- Księżak, J. Evaluation of faba bean productivity depending on hydrogel rate and humidity soil level. Fragm. Agron. 2018, 35, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Q.; Geetha, K.N.; Hashimi, R.; Atif, R.; Habimana, S. Growth and yield of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] as influenced by organic manures and superabsorbent polymers. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2020, 42, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, F.; Allahdadi, I.; Akbari, G.A. Impact of superabsorbent polymer on yield and growth analysis of soybean (Glycine max L.) under drought stress condition. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 4190–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panasiewicz, K.; Faligowska, A.; Szymańska, G.; Szukała, J.; Koziara, W.; Ratajczak, K. The effects of using hydrogel in pea cultivation (Pisum sativum L.). Biul. Inst. Hod. Aklim. Rośl. 2019, 285, 235–236. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Faligowska, A.; Szukała, J. Influence of irrigation, soil tillage systems and polymer on yielding and sowing value of pea. Fragm. Agron. 2011, 28, 15–22. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Faligowska, A.; Szukała, J. Influence of organic polymer on yield components and seed yield of soybean. Nauka Przyr. Technol. 2014, 8, 9. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Arve, L.; Torre, S.; Olsen, J.; Tanino, K. Stomatal responses to drought stress and air humidity. In Abiotic Stress in Plants—Mechanisms and Adaptations; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nawata, E.; Hosokawa, M.; Domae, Y.; Sakuratani, T. Alterations in photosynthesis and some antioxidant enzymatic activities of mungbean subjected to waterlogging. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeEll, J.R.; Van Kooten, O.; Prange, R.K.; Murr, D.P. Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence techniques in postharvest physiology. In Horticultural Reviews; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; Volume 23, pp. 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.F.; Ribeiro Júnior, W.Q.; Ramos, M.L.G.; Soares, G.F.; de Lima Guimarães, C.A.; da Silva Neto, S.P.; Williams, T.C.R. The impact of polymer on the productivity and photosynthesis of soybean under different water levels. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ahmad, R.; Safdar, M. Effect of hydrogel on the performance of aerobic rice sown under different techniques. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant drought stress: Effects, mechanisms and management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, O.H. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool in cereal crop research. Photosynthetica 2003, 41, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M.; El-Tohamy, W.A.; El-Abagy, H.M.H.; Aggor, F.S.; Nada, S.S. Response of snap bean plants to super absorbent hydrogel treatments under drought stress conditions. Curr. Sci. Int. 2015, 4, 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, M.M.; Alharbi, B.M.; Alzahrani, Y.M.; Alghamdi, A.G.; Alzahrani, M.M. Influence of super-absorbent polymer on growth and productivity of green bean under drought conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.