Abstract

The non-destructive estimation of grain yield could increase the efficiency of soybean breeding through early genotype testing, allowing for more precise selection of superior varieties. High-throughput phenotyping (HTPP) data can be combined with machine learning (ML) to develop accurate prediction models. In this study, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) equipped with a multispectral camera was utilized to collect data on plant density (PD), plant height (PH), canopy cover (CC), biomass (BM), and various vegetation indices (VIs) from different stages of soybean development. These traits were used within random forest (RF) and partial least squares regression (PLSR) algorithms to develop models for soybean yield estimation. The initial RF model produced more accurate results, as it had a smaller error between actual and predicted yield compared with the PLSR model. To increase the efficiency of the RF model and optimize the data collection process, the number of predictors was gradually decreased by eliminating highly correlated VIs and selecting the most important variables. The final prediction was based only on several VIs calculated from a few mid-soybean stages. Although the reduction in the number of predictors increased the yield estimation error to some extent, the R2 in the final model remained high (R2 = 0.79). Therefore, the proposed ML model based on specific HTPP variables represents an optimal balance between efficiency and prediction accuracy for in-season soybean yield estimation.

1. Introduction

Soybean is one of the most important crops worldwide, with an annual global production exceeding 370 million tons in 2023. Over the past decade, the harvested area for this legume increased by 23%, while the average yield has risen by 8%, indicating that expansion to the new fields has a dominant impact on world production [1]. Since cropland is a limited resource, enhancing productivity per unit area is necessary to meet the needs of the growing human population [2]. Breeding high-yielding genotypes represents an effective way to overcome these challenges. So far, new soybean varieties with improved agronomic characteristics have been successfully developed through traditional breeding. Although significant attention is given to secondary traits such as stress tolerance or seed nutritional composition, increasing yield remains the primary goal of most breeding programs [1]. In soybean, cultivar development requires substantial time and resources, as it typically takes 10–12 years from the initial cross to the release of a new variety. One way to enhance the efficiency of current soybean breeding programs could be through early yield testing [3]. Traditional methods for measuring yield are destructive, laborious, and time-consuming, which limits their application in the early stages of soybean breeding, where a large number of genotypes are tested [4]. This issue could be addressed by implementing large-scale high-throughput phenotyping (HTPP) in the process of genotype selection.

The primary advantage of HTPP over traditional phenotyping is that it allows for the screening of numerous genotypes in a short timeframe [5,6]. Various platforms including satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and ground-based systems equipped with optical sensors (RGB, multispectral, hyperspectral, or thermal) capture spatial and temporal information of monitored objects. The acquired data are then used for remote sensing and photogrammetric analyses [7]. Both techniques are non-invasive and sensor-based. However, remote sensing derives information from the light reflected by the target object [8], whereas photogrammetry enables the direct measurement of objects from images [9].

Using plant reflectance data, it is possible to calculate numerous vegetation indices (VIs) based on mathematical combinations of information obtained from different parts of the light spectrum [10]. Many indices showed great potential for HTPP, from weed detection [11] and plant/soil segmentation [12] to canopy cover (CC) [13] and biomass (BM) estimation [14]. Vianna et al. (2025) [15] found a high correlation between soybean yield and four visible-light VIs: red–green–blue vegetation index (RGBVI), green leaf index (GLI), visible atmospheric resistant index (VARI), and normalized green–red difference index (NGRDI) calculated at the seed filling (R5) period. Still, the variability of these indices decreases as the season progresses, which can limit their usability for HTPP. On the other hand, VIs derived from other parts of the light spectrum, like red-edge (RE) and/or near-infrared (NIR) can provide better insights into plant development and allow for more accurate determination of various traits [16]. The most notable example is the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), calculated as the ratio of NIR and red (R) light. The NDVI was successfully used in many previous studies to predict yield of different crops such as wheat [17], potato [18], and maize [19]. Santana et al. (2022) [20] found that NDVI from the flowering stage (R1–R2) can be used to select soybean genotypes with high yield potential. However, the effectiveness of NDVI for crop phenotyping can also be compromised in later stages due to the saturation effect caused by dense canopy [21].

Due to VI limitations, soybean yield prediction based on spectral reflectance can be successful yet a challenging task. The use of additional information such as number of plants/m2 or plant density (PD), plant height (PH), CC, and BM can contribute to more accurate results. The previous studies showed that these traits are closely related to soybean yield. Plant density affects yield through pod [22] and branch number [23]. The CC, defined as the fraction of the soil covered by plants [24], has a positive impact on the amount of intercepted radiation, which increases crop productivity [25]. The total accumulated organic matter can also be a good indicator of radiation use efficiency (RUE) [26]. According to Gajić et al. (2018) [27], genotypes with greater BM achieve higher yields. Plant height does not have a direct impact on soybean yield [28], as it does in other crops such as wheat [29]. However, PH can affect yield indirectly, as a significant number of seeds can be lost due to lodging, which is more pronounced in taller genotypes [30]. Today, PH can be relatively easy estimated using structure from motion (SfM) photogrammetry to analyze images collected with the UAV and digital camera. In brief, the SfM technique uses data from images to create a digital surface model (DSM) and a digital terrain model (DTM), where the DSM represents the elevation of the surface while the DTM indicates the elevation of the bare soil. The difference between the DSM and DTM represents PH. This method has been successfully applied in many previous studies [31,32,33].

To maximize the benefits of the comprehensive, multi-variable approach to soybean yield prediction, it is also important to leverage the power of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). AI and ML enable dealing with big datasets, pattern recognition, and the analysis of multiple variables simultaneously to provide more accurate estimation of important agronomic traits [34]. Artificial neural networks (ANNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and support vector regression (SVR) are more suitable for segmentation, recognition, and object counting in the images [35]. On the other hand, random forest (RF) is an ML algorithm that uses combined data from multiple binary trees to make predictions [36]. Previously, RF has been successfully used to estimate specific crop traits, including leaf area index (LAI) [37], chlorophyll concentration [38], and BM accumulation [39]. RF also provides high accuracy when it comes to yield prediction. In the recent study on maize, RF outperformed other ML and deep learning (DL) algorithms in yield estimation based on spectral and textural indices [40]. Herrero-Huerta et al. (2020) [41] found that RF can be utilized to estimate productivity of the soybean genotypes based on VIs, CC, PH and other UAV data extracted from the images in two mid-stages. Another commonly used ML algorithm in HTPP is partial least squares regression (PLSR). PLSR uses latent components obtained through the transformation of the original variables to estimate the trait of interest [42]. PLSR has proven to be a good choice in dealing with the high-volume inputs and multicollinearity, which are common in remote sensing data. According to earlier findings, PLSR has been successfully used with spectral data to estimate BM [43], LAI [44], and plant nitrogen status [45]. Many previous studies have highlighted the potential of PLSR for yield estimation in crops such as soybean [46], corn [47], and barley [48].

The main goal of this research was to develop an ML model for in-season prediction of soybean yield using temporal UAV data. The study was based on a comprehensive approach that included the use of two ML algorithms (RF and PLSR) and a complex predictor dataset consisting of VIs, PD, CC, PH, and BM assessed at several time points during the growing season. All input variables were obtained through HTPP using previously described methods and utilized as direct predictors within the ML models. Therefore, the specific aim of the present study was to provide a fully digital framework for accurate and reliable estimation of yield as the most important crop trait.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Plant Material

The study was carried out during 2020 and 2021 growing seasons on the experimental fields of Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops in Rimski Šančevi, Novi Sad, Serbia. The plant material consisted of 206 soybean genotypes from different maturity groups. Each cultivar was sown in four rows on 8 m2 individual plots, while some of them were replicated and used as controls. In both years the same set of genotypes was planted on two different soils, chernozem and sandy loess. These soils have contrasting characteristics in terms of mechanical composition, texture, fertility, and water retention (Table A1). Contrasting environments were used to increase the variability in predictor values, thereby contributing to the development of a more robust prediction model. The initial number of soybean plots used within this study was 1120.

2.2. Remote Sensing and Yield Data Acquisition

The images of soybean calibration plots were captured with six (five monochromatic and one RGB) CMOS sensors incorporated in a P4M (DJI, Shenzhen, China) drone. All sensors had a width of 1/2.9″ and effective resolution of 2.08 megapixels. Each monochromatic photodetector covered a specific part of the electromagnetic spectrum: B (450 ± 16 nm), G (560 ± 16 nm), R (650 ± 16 nm), RE (730 ± 16 nm), and NIR (840 ± 26 nm). To ensure data accuracy under different weather conditions, the P4M drone uses a built-in sun sensor to calibrate reflectance based on sunlight exposure. Additionally, during every flight the P4M drone was linked to the real-time kinematic (RTK) system, an external satellite receiver, to secure horizontal and vertical precision for the UAV footage.

In both seasons, UAV images were captured at 12 time points, represented as cumulative growing degree days (GDDs) after emergence. The daily GDDs were calculated using the following formula, adopted from Akyüz and Ransom (2015) [49]:

where and are the daily maximum and minimum temperatures, and is the base temperature, which for soybean is typically 10 °C.

Each year, flights were conducted approximately at 103, 167, 230, 274, 390, 474, 642, 706, 828, 917, 1001, and 1130 GDDs. The flights were conducted using DJI GS PRO software (version 2.0, DJI, Shenzhen, China) on sunny days around local solar noon at 60 m altitude, securing a resolution of 3.17 cm/pixel. During the image acquisition, photographs were captured at equal time intervals, with 80% front and side overlap. At full maturity (R8), soybean genotypes were harvested with a Wintersteiger combine harvester (Wintersteiger AG, Ried, Austria) and the plot yield was adjusted to 14% moisture. Seven plots were lost due to abiotic and biotic factors, which reduced the initial number of calibration parcels from 1120 to 1113.

2.3. Image Analysis and Variable Extraction

After every flight, the Agisoft PhotoScan software (version 1.7.2, Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) was used to generate specific derivates, including dense point clouds, DEMs, and orthomosaics from the UAV photos. Before generating these derivatives, UAV image reflectance was calibrated in Agisoft using the Calibrate Reflectance function and the sun-sensor data recorded during each flight. Following the project generation procedure, necessary variables for yield prediction model were extracted. Subsequent to each of the 12 UAV flights, the digital numbers (DNs) of the R, G, B, RE, and NIR channels were extracted in Fiji Is Just ImageJ (FIJI) software (version 1.51) for the 1113 soybean calibration plots. The DN data was used to calculate 33 different VIs at each time point (Table A2).

For all soybean plots, PD was estimated using RGB images from 230 and 390 GDDs and an ML model, previously developed by Ranđelović et al. (2020) [50]. The CC data assessed at the 12 time points was used to calculate CCmax, defined as the total number of days with CC over 90%. On the other hand, PH and BM were estimated using UAV images from the flights conducted at 230, 274, 390, 642, 706, 917, 1001, and 1130 GDDs in both years. The CC was calculated as the percentage of plant pixels in each calibration plot, while PH was determined based on the difference between DSM and DTM. Finally, BM of each plot was estimated using a previously developed RF model and predictor variables, including PH and two vegetation indices (GCI and TGI). The complete methodology for predicting CC, PH, and BM was based on the findings of Ranđelović et al. (2023) [51].

2.4. Development of Yield Prediction ML Model

The initial prediction of soybean yield was performed with RF and PLSR algorithms in R (version 4.3.1) using the Caret package [52] and train function. The optimal number of trees (ntree) in the RF model was chosen based on the lowest root mean square error (RMSE), while the number of predictors evaluated at each node (mtry) was selected according to the results of cross-validation. For the PLSR model, data scaling was applied to the predictors by setting the scale argument to TRUE. Additionally, the number of latent components (ncomp) in the PLSR model was set to the value that secured the smallest RMSE in yield estimation.

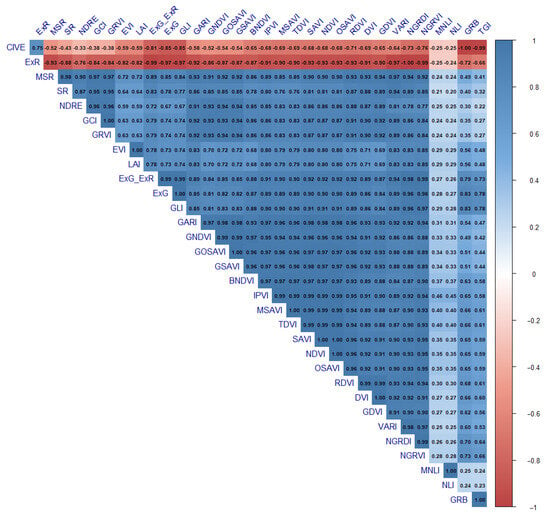

Prior to development of the two ML models, the correlation among VIs was observed through the values of the correlation coefficient (r). Based on the r values, a correlation matrix was created in R using the corrplot function from the corrplot package [53]. The next step was the elimination of highly correlated VIs (r threshold ± 0.8) using the findCorrelation function from the Caret package and mean absolute correlation (MAC) of each index. The MAC value was used to evaluate pairwise correlations among indices and to identify redundant predictors. In comparisons between two correlated VIs, the one with the higher MAC value was eliminated.

The remaining data, including seed yield, non-correlated VIs, PD, CC, PH, and BM obtained from the 1113 soybean calibration plots, was separated into training and test sets (70/30) using leave-group-out cross-validation (LGOCV). This procedure was performed 10 times, and each time data from the calibration plots was split differently. The average results of ten repetitions were used as the final outputs of the model. The performance of the proposed models was evaluated by comparing estimated with real yield. The more accurate ML model was selected based on the values of the coefficient of determination (R2), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE). Additionally, a 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) for RMSE was assessed for the RF and PLSR models.

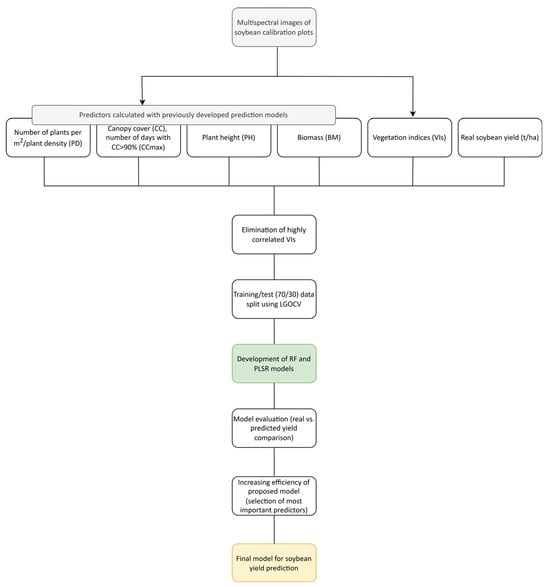

In the RF algorithm, the function rfPermute within the rfPermute package [54] was utilized to obtain information about variable importance. The significance of each predictor was determined at the level of p < 0.01. The remaining variables were used to analyze yield change based on the predictor dynamics. The relationship between seed yield and selected variables was shown with partial dependence plots (PDPs) and individual conditional expectation (ICE) plots [55]. PDPs show the general trend of a trait depending on the dynamic of a predictor, while ICE is used to perceive the change at the plot level [56]. Both graphs were constructed with the iml package [57] in R. A visual summary of the workflow described in the previous section is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the soybean yield prediction model.

3. Results

The complete set of 426 variables, with mtry = 214 and ntree = 500 set as optimal tuning parameters in the RF model, resulted in good accuracy (RMSE = 0.49 t/ha) in soybean yield prediction. Compared to RF, the PLSR model (ncomp = 13) obtained similar results (RMSE = 0.50 t/ha) using the same predictors. In the next step, the number of input variables was reduced through the elimination of highly correlated VIs (Figure A1). The analysis showed that 254 out of 528 correlations between 33 selected VIs were higher than the cut-off value (±0.8). Based on the initially defined criteria, including r and MAC values, the highly correlated indices were excluded, leaving only LAI, NLI, NDRE, and TGI from 12 time points as independent variables. The RF and PLSR models were used to predict soybean yield with the new, reduced dataset, consisting of 78 predictors. This time, the optimal combination of tuning parameters in the RF model was mtry = 26 and ntree = 500, while for PLSR, ncomp was set to 16. The results showed that RF maintained the same accuracy (RMSE = 0.50 t/ha), whereas in PLSR, the reduction in predictor number increased the error (RMSE = 0.54 t/ha) between observed and estimated yield (Table 1).

Table 1.

Different models for soybean yield prediction. RF (random forest), PLSR (partial least squares regression), PD (plant density), VIs (vegetation indices), CC (canopy cover), CCmax (canopy cover max), PH (plant height), BM (biomass).

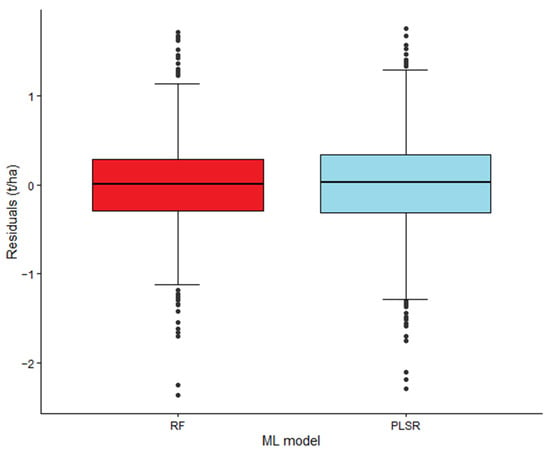

To further evaluate the performance of the two ML models, the residuals (differences between actual and predicted yield) were analyzed (Figure 2). Using the reduced-predictor dataset, the RF model achieved a lower standard deviation of residuals (SD = 0.50 t/ha) compared to PLSR (SD = 0.54 t/ha).

Figure 2.

Box plots of residuals (differences between actual and predicted soybean yield, t/ha) for the random forest (RF) and partial least squares regression (PLSR) models based on the reduced set of predictors. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals, the lines inside the boxes represent the median values, and the points represent outliers.

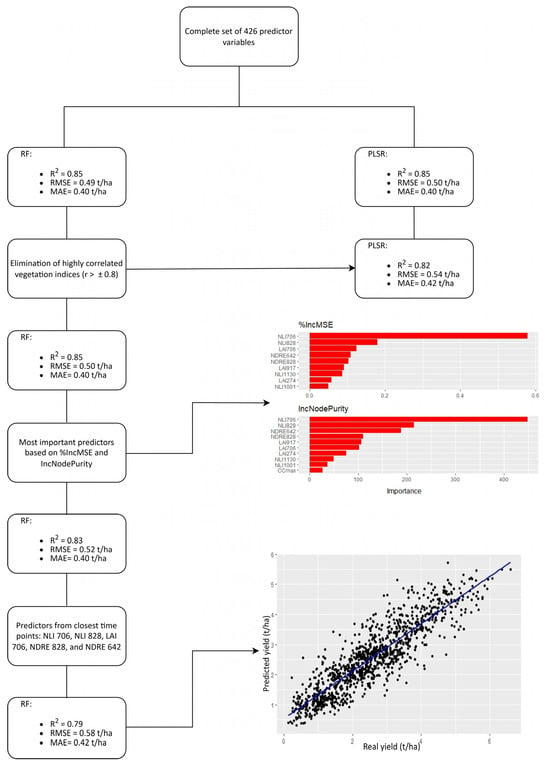

Since the PLSR model was outperformed and subsequently eliminated, the following steps focused on further improving the efficiency of the proposed RF model. The variable importance for the remaining 78 predictors was observed based on two indicators, %IncMSE and IncNodePurity (p < 0.01). It turned out that CCmax and nine VIs, including LAI 274, LAI 390, LAI 706, LAI 917, NLI 706, NLI 828, NLI 1130, NDRE 642, and NDRE 828, were important. A unique set of ten selected variables and the proposed RF model with mtry = 2 and ntree = 500 set as optimal tuning parameters ensured high accuracy in soybean yield prediction (R2 = 0.85). Since the significant reduction in the number of variables (426 → 78 → 10) did not affect the precision, a last stage was initiated to create the most efficient model. This involved selection of only five predictors from three closest time points: NLI 706, NLI 828, LAI 706, NDRE 828, and NDRE 642. The final RF prediction model (mtry = 3 and ntree = 500) secured good results in soybean yield prediction, with RMSE maintained below 0.6 t/ha. The stepwise development of the final soybean yield prediction model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The stepwise variable reduction in the soybean yield prediction model.

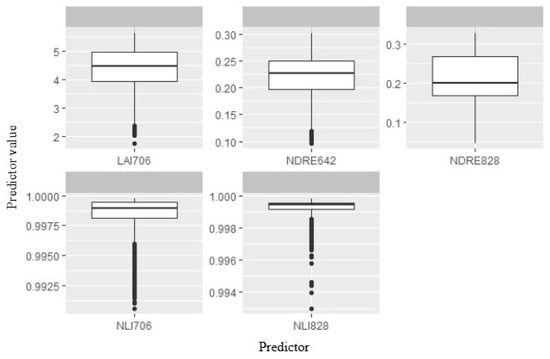

Variability of five selected predictors was analyzed through individual values obtained from the soybean calibration plots (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Value of selected predictors from the proposed RF model for soybean yield prediction. The line in each box plot stands for the median value. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals, and outliers are represented by dots.

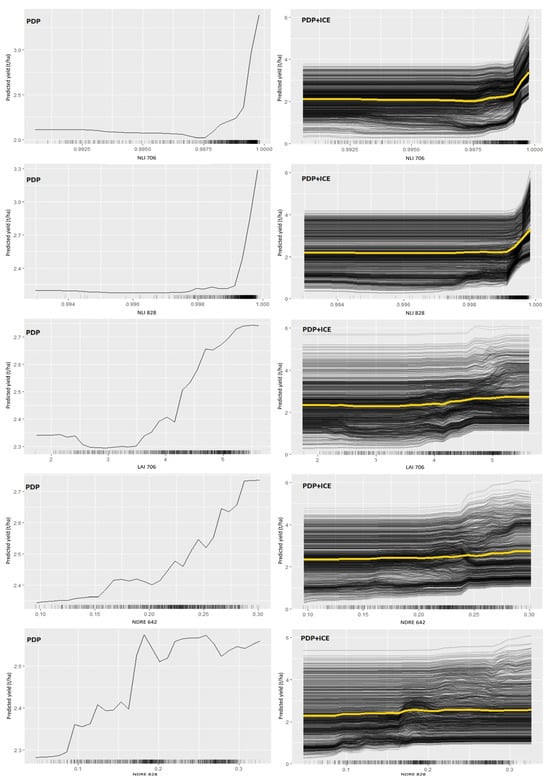

The LAI 706 values were between 1.75 and 5.63, with an average of 4.32. A wide range was observed also for the NDRE 642 and NDRE 828. For the first one, the span was between 0.1 and 0.3, while for the second, the interval was from 0.05 to 0.33. The average value of both VIs was similar (around 0.22), even with the 200 GDDs of time difference between them. Regarding NLI 706 and NLI 828, variation in individual values was small since the difference was observed only at the third or fourth decimal. In all calibration plots, NLI 706 and NLI 828 were over 0.99. The yield dynamic was observed through changes in predictor variables and shown in PDPs and PDP + ICE plots (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The effect of the five selected vegetation indices on soybean yield, predicted with the proposed RF model. The curves represent the partial dependence relationships, while the black dashes below the curves indicate the data distribution.

The summary PDP + ICE graph shows that the break point for NLI 706 was around 0.9975. An increase in seed yield from 2 t/ha to over 3 t/ha was observed when NLI 706 exceeded the critical value. A similar yield dynamic was found for the NLI 828, except in this case, the cut-off was higher than 0.999. When it comes to LAI 706, the soybean yield remained unchanged until the VI reached 3.5. With the further increase in LAI 706 to 5.5, yield increased from 2.3 t/ha to 2.75 t/ha. The last two VIs included in the yield prediction model were NDRE 642 and NDRE 828. The results showed that the yield increased from 2.35 t/ha to 2.75 t/ha when the values of NDRE 642 were higher than 0.15. When it comes to NDRE 828, two critical points were identified for high/low-yield differentiation. The first occurred at 0.09, separating all plots with yields higher than 2.3 t/ha. With a further increase in NDRE 828 to 0.16, the yield rose to 2.4 t/ha. After that, a second spike appeared when the predictor reached a value of 0.18, at which point the yield reached 2.5 t/ha.

4. Discussion

The initial estimation of soybean yield was performed for 1113 calibration plots using 426 predictors (PD, CC, and 33 VIs from 12 time points; CCmax; PH, and BM from 8 time points) in RF and PLSR algorithms. Both models showed high accuracy (R2 = 0.85), with similar errors between observed and predicted yield: RF (RMSE = 0.49 t/ha) and PLSR (RMSE = 0.50 t/ha). These models provided better results than those reported in similar studies. Maimaitijiang et al. (2020) [58] used spectral (VIs), structural (PH and CC), thermal (leaf temperature), and textural (frequency of plant pixels) variables in RF and PLSR models to estimate soybean yield at the R3 (beginning pod) development stage. The two models had good accuracy (R2 = 0.65) when comparing observed and estimated yield. The same authors suggested that the deep neural network (DNN) model performed best, securing more precise results (R2 = 0.72). However, this value is still considerably lower compared to the results obtained in this study. The accuracy of prediction models can be improved by using variables from different stages of plant development. Zhou et al. (2021) [59] achieved better results (R2 = 0.78) in soybean yield prediction with a CNN model based on PH and reflectance data collected at V6 (sixth trifoliolate), R1, and R6 (full seed)–R8 (full maturity). On the other hand, the use of a large number of predictors increases the complexity of the ML model, requiring more time and resources to extract the necessary data. In our study, the efficiency of the final RF model was enhanced through variable reduction performed in several successive stages. At the first stage, highly correlated VIs were eliminated, and only LAI, NLI, NDRE, and TGI from 12 time points were used in RF. Applying the remaining 78 predictors in the proposed ML model did not reduce the model’s accuracy (R2 = 0.85). In the next step, the importance of the remaining predictors was assessed based on two parameters, %IncMSE and IncNodePurity. As a result, ten variables were selected, including LAI 274, LAI 390, LAI 706, LAI 917, NLI 706, NLI 828, NLI 1130, NDRE 642, NDRE 828, and CCmax. Further reduction led to a slight decrease in the model’s precision, as R2 decreased from 0.85 to 0.83 and RMSE increased by 0.03 t/ha. The final dataset contained only a few variables, which ensured maximum efficiency of the proposed RF model. The optimized ML model based on five VIs (NLI 706, NLI 828, LAI 706, NDRE 828, and NDRE 642) from mid-stages of soybean development achieved acceptable accuracy in yield prediction (R2 = 0.79). However, the severe reduction in the number of predictors caused an increase in yield estimation error from the initial RMSE = 0.49 t/ha to RMSE = 0.58 t/ha in the final RF model. This suggests that the excluded variables (PD, PH, CC, BM, and remaining VIs) also had explanatory potential for assessing soybean yield variability. Nevertheless, the proposed ML model represents an acceptable parsimony–precision trade-off, as the reduced dataset secured good accuracy while simultaneously improving efficiency in terms of time and resources.

The predictive model’s selected time points coincide with the stages of development and physiological processes which determine soybean yield. Seed weight and seed number per unit area are key soybean yield components, while final seed number is determined by the crop growth rate from R1–R5 [60].

All indices that were used in our model included the NIR region, which indicates the importance of this part of the light spectrum for yield prediction. The cell structure is the crucial factor for the amount of reflected NIR light [61]. Previous studies found that an increase in the ratio of mesophyll cell area (MCA) to intercellular air cavities (IACs) enhanced NIR reflectance [62]. Since high values of MCA/IACs are also closely related to plant photosynthetic activity and gas exchange [63], it is not surprising that VIs based on NIR reflectance have strong potential for yield prediction [64]. For instance, LAI is directly linked to the amount of intercepted radiation and the photosynthetic activity of plants, which are essential for achieving high productivity [65]. Previous studies have reported a strong relationship between NDRE and various soybean traits, including chlorophyll content and biomass accumulation [66]. These traits serve as important indicators of plant growth and physiological capacity, ultimately driving yield formation [67,68]. Finally, NLI is closely associated with LAI and shows high sensitivity in estimating the fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (fAPAR) [69], which is one of the key factors for achieving the maximum yield potential of crops [70]. Shammi et al. (2024) [71] used 14 different indices to assess soybean productivity during the growing season, and also found that NIR-based VIs had the strongest correlation with seed yield. Nevertheless, the use of RGB indices can be an acceptable option, especially in the absence of more expensive multispectral sensors. For example, Bai et al. (2022) [72] achieved an accuracy of R2 = 0.49–0.64 in soybean yield estimation using visible-light VIs within an ML algorithm. However, many previous studies have emphasized the limitations of RGB indices for yield prediction, particularly later in the season, due to their restricted spectral information compared to NIR-derived VIs [73,74]. Our research indicates that soybean yield is mostly related to VIs calculated at later development stages. This finding is consistent with previous studies like those of Gao et al. (2018) [75] or Joshi et al. (2023) [76], who also concluded that best results in soybean yield prediction were obtained using spectral data from the reproductive period.

In the proposed ML model for soybean yield prediction, the relationship between predictors and the target variable was analyzed using PDP and PDP + ICE plots. These plots provide insights into how the predicted yield changes as the value of each individual VI varies, while all other variables are held constant. Our study showed that higher yields are related to the higher values of five selected VIs. However, this trend is not linear, as each index shows a clear breakpoint which occurs in the mid- and mostly high-value range. Similar findings were reported by Deng et al. (2025) [77], who also reported that the relationship between VIs and predicted yield is not straightforward. The same authors also emphasized that yield improvement is associated with increased reflectance in the RE and NIR spectral regions, the parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that also contribute most significantly to our model.

Given that the proposed ML model for soybean yield prediction was developed using data collected from over 1000 soybean plots grown on different soils (chernozem/loess), it captured high variability in VIs. Therefore, the model is expected to perform accurately even in unseen environments, suggesting it as a promising tool for in-season soybean yield prediction. However, the prediction model exhibited certain discrepancies between real and estimated soybean yield. One possible reason for this could be the accurate determination of VI values, which can be disrupted by weed presence, as weeds alter the reflectance of the plot [78]. Additionally, abiotic factors such as drought can affect biophysical and biochemical plant characteristics, resulting in changes in the spectral response of reflected radiation [79]. This highlights the need for further testing of the proposed model in new environments and on different germplasm to fully evaluate its robustness and generalizability.

5. Conclusions

The HTPP dataset, consisting of various VIs, PD, CC, CCmax, PH, and BM, was derived at different soybean growth stages and applied within RF and PLSR algorithms to estimate grain yield. Using the complete set of predictor variables, both models showed similar accuracy when comparing real and estimated yield (RF: RMSE = 0.49 t/ha; PLSR: RMSE = 0.50 t/ha). In the following step, highly correlated VIs were eliminated and both models were tested with the new dataset. This time the RF model secured lower prediction error (RMSE = 0.49 t/ha) compared to the PLSR (RMSE = 0.54 t/ha). To improve the efficiency of the more accurate ML model, several successive reduction steps were performed. At each stage, the number of variables decreased while the model’s performance was continuously monitored. At the next stage, the ten most important variables were selected based on %IncMSE and IncNodePurity metrics. The RF model maintained high precision even with this substantially reduced dataset. This enabled full optimization of the proposed ML model, leaving only NLI 706, NLI 828, LAI 706, NDRE 828, and NDRE 642 as the necessary variables to ensure good accuracy (R2 = 0.79; RMSE = 0.59 t/ha) in soybean yield prediction. The study further suggests that the values of these selected VIs could serve as early indicators of high-yielding soybean varieties. However, further studies are required to test the model in new environments and across different genotypes to confirm the relationship between yield and VI dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R.; methodology, P.R. and V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević); software, P.R.; validation, V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević), J.M. and M.Ć.; formal analysis, P.R.; investigation, P.R., M.Ć., S.B., and V.Đ. (Vojin Đukić); resources, V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević); data curation, P.R., S.B., M.Ć., and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević), J.M., S.B., M.Ć., and V.Đ. (Vojin Đukić); visualization, P.R.; supervision, V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević) and J.M.; project administration, M.V.; funding acquisition, V.Đ. (Vuk Đorđević). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia through PRISMA project “Soybean Yield Prediction Using Multi-omics Data Integration” (SoyPredict), grant number 6788; the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, grant number 451-03-136/2025-03/200032; and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 project ECOBREED—Increasing the efficiency and competitiveness of organic crop breeding, grant number 771367.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Correlation matrix of vegetation indices used for soybean yield prediction with random forest (RF) and partial least squares regression (PLSR) models.

Table A1.

Mechanical composition, organic matter, and water retention capacity of two soil types (sandy loess and chernozem) used for development of soybean yield prediction model.

Table A1.

Mechanical composition, organic matter, and water retention capacity of two soil types (sandy loess and chernozem) used for development of soybean yield prediction model.

| Category | 2020 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy Loess | Chernozem | Sandy Loess | Chernozem | ||

| Coarse sand (%) 2–0.2 mm | 1.04 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.435 | |

| Fine sand (%) 0.2–0.02 mm | 68.7 | 44.52 | 64.46 | 44.585 | |

| Silt (%) 0.02–0.002 mm | 16.68 | 29.5 | 17.68 | 25.66 | |

| Clay (%) <0.002 mm | 13.58 | 25.06 | 17.12 | 29.32 | |

| Organic matter (%) | 1.165 | 2.65 | 1.63 | 2.56 | |

| Water retention (% vol.) | 0.33 bar | 15.53 | 26.735 | 19.775 | 28.375 |

| 6.25 bar | 8.205 | 15.87 | 10.15 | 17.46 | |

| 15 bar | 7.07 | 14.54 | 8.65 | 15.46 | |

Table A2.

Vegetation indices (VIs) used for prediction of soybean yield. R, G, B, RE, and NIR digital numbers calculated from the individual channels of UAV images.

Table A2.

Vegetation indices (VIs) used for prediction of soybean yield. R, G, B, RE, and NIR digital numbers calculated from the individual channels of UAV images.

| Vegetation Index | Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| TGI | Triangular greenness index | |

| GLI | Green leaf index | |

| VARI | Visible atmospherically resistant index | |

| NGRDI | Normalized green–red difference index | |

| CIVE | Color index of vegetation extraction | |

| ExG * | Excessive green | |

| ExR * | Excessive red | |

| ExG-ExR | Excess green minus excess red index | |

| DVI | Difference vegetation index | |

| GARI | Green atmospherically resistant vegetation index | |

| GCI | Green chlorophyll index | |

| GDVI | Green difference vegetation index | |

| GNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index | |

| GOSAVI | Green optimized soil adjusted vegetation index | |

| GRVI | Green ratio vegetation index | |

| GSAVI | Green soil adjusted vegetation index | |

| IPVI | Infrared percentage vegetation index | |

| MNLI | Modified non-linear vegetation index | |

| MSAVI | Modified soil-adjusted vegetation index | |

| MSR | Modified simple ratio | |

| NLI | Non-linear vegetation index | |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index | |

| OSAVI | Optimized soil-adjusted vegetation index | |

| RDVI | Renormalized difference vegetation index | |

| SAVI | Soil-adjusted vegetation index | |

| SR | Simple ratio index | |

| TDVI | Transformed difference vegetation index | |

| NDRE | Normalized difference red-edge | |

| 2G-R-B | / | |

| NGRVI | New green–red vegetation index | |

| BNDVI | Blue normalized difference vegetation index | |

| EVI | Enhanced vegetation index | |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

* r = R/(R + G + B); b = B/(R + G + B); g = G/(R + G + B).

References

- Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Feng, F.; Tian, Z. Toward a “Green Revolution” for soybean. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; Ren, H.; Sun, R.; Wei, Z.; Hong, H.; Luan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Soybean genetic resources contributing to sustainable protein production. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4095–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.F.; Hearst, A.A.; Cherkauer, K.A.; Rainey, K.M. Improving the efficiency of soybean breeding with high-throughput canopy phenotyping. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Schmidhalter, U.; Reynolds, M.P.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Varshney, R.K.; Yang, T.; Nie, C.; Li, Z.; Ming, B.; et al. High-throughput estimation of crop traits: A review of ground and aerial phenotyping platforms. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2021, 9, 200–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyonje, W.A.; Schafleitner, R.; Abukutsa-Onyango, M.; Yang, R.Y.; Makokha, A.; Owino, W. Precision phenotyping and association between morphological traits and nutritional content in Vegetable Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.). J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.; Gill, S.K.; Saini, D.K.; Chopra, Y.; de Koff, J.P.; Sandhu, K.S. A comprehensive review of high-throughput phenotyping and machine learning for plant stress phenotyping. Phenomics 2022, 2, 156–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Sandhu, K.S.; Kamal, R.; Kaur, K.; Singh, J.; Röder, M.S.; Muqaddasi, Q.H. Omics for the improvement of abiotic, biotic, and agronomic traits in major cereal crops: Applications, challenges, and prospects. Plants 2021, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugapriya, P.; Rathika, S.; Ramesh, T.; Janaki, P. Applications of remote sensing in agriculture-A review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 2270–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Queiroz, R.F.; Neves, M.V.; Rezende, A.V.; De Alencar, P.A. Estimation of aboveground biomass stock in tropical savannas using photogrammetric imaging. Drones 2023, 7, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viña, A.; Gitelson, A.A.; Nguy-Robertson, A.L.; Peng, Y. Comparison of different vegetation indices for the remote assessment of green leaf area index of crops. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 3468–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; López-Granados, F.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; Ramírez, P.; Castillejo-González, I.L.; Castro, A.I.D. Automatic UAV-based detection of Cynodon dactylon for site-specific vineyard management. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehle, D.; Reiser, D.; Griepentrog, H.W. Robust index-based semantic plant/background segmentation for RGB- images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenreiro, T.R.; García-Vila, M.; Gómez, J.A.; Jiménez-Berni, J.A.; Fereres, E. Using NDVI for the assessment of canopy cover in agricultural crops within modelling research. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 182, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Wang, Y.; Chu, N.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, D. Mature rice biomass estimation using UAV-derived RGB vegetation indices and growth parameters. Sensors 2024, 25, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, M.S.; Matias, F.I.; Galli, G.; Martins, E.S.; Oliveira, M.; Pinheiro, J.B. Using red–green–blue vegetation indices to evaluate complex agronomical traits in soybean breeding. Agron. J. 2025, 117, e21723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.H.; Cortes, D.F.; Andrade, L.R.; Gallis, R.B.; Barbosa, R.L.; Oliveira, E.J. High-throughput phenotyping for agronomic traits in cassava using aerial imaging. Plants 2024, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.R.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, A.; Mubeen, M.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M.; Ahmad, S.; Ercisli, S.; Jaafar, H.Z. Normalized difference vegetation index as a tool for wheat yield estimation: A case study from Faisalabad, Pakistan. Sci. World J. 2013, 2014, 725326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswal, P.; Faisal, A.; Swain, D.K.; Bhowmick, G.D.; Mohan, G. NDVI is the best parameter for yield prediction at the peak vegetative stage of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Clim. Smart Agric. 2025, 2, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soccolini, A.; Vizzari, M. Predictive Modelling of Maize Yield Using Sentinel 2 NDVI. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2023 Workshops; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Garau, C., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14107, pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, D.C.; de Oliveira Cunha, M.P.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Cotrim, M.F.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; da Silva Junior, C.A.; Baio, F.H.R.; Teodoro, P.E. High-throughput phenotyping allows the selection of soybean genotypes for earliness and high grain yield. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsebő, S.; Bede, L.; Kukorelli, G.; Kulmány, I.M.; Milics, G.; Stencinger, D.; Teschner, G.; Varga, Z.; Vona, V.; Kovács, A.J. Yield prediction using NDVI values from GreenSeeker and MicaSense cameras at different stages of winter wheat phenology. Drones 2024, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigsby, B.; Board, J.E. Identification of soybean cultivars that yield well at low plant populations. Crop Sci. 2003, 43, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Fan, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Feng, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yong, T.; et al. Auxin-to-gibberellin ratio as a signal for light intensity and quality in regulating soybean growth and matter partitioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdi, K.S.; Sreekanta, S.; Dobbels, A.; Haaning, A.; Jarquin, D.; Stupar, R.M.; Lorenz, A.J.; Muehlbauer, G.J. Branch angle and leaflet shape are associated with canopy coverage in soybean. Plant Genome 2023, 16, e20304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, D.; Khan, S.; Rayburn, A. Soybean yield response to narrow rows is largely due to enhanced early growth. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L. Radiation use efficiency: Evaluation of cropping and management systems. Agron. J. 2014, 106, 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, B.; Kresović, B.; Tapanarova, A.; Životić, L.; Todorović, M. Effect of irrigation regime on yield, harvest index and water productivity of soybean grown under different precipitation conditions in a temperate environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 210, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diondra, W.; Ivey, S.; Washington, E.; Woods, S.; Walker, J.; Krueger, N.; Sahnawaz, M.; Kassem, M.A. Is there a correlation between plant height and yield in soybean? Rev. Biol. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, U.S.; Shrestha, N.; Maharjan, S.; Pratihast, A.K.; Shahnawaz; Shrestha, K.L.; Aryal, J. Correlating the plant height of wheat with above-ground biomass and crop yield using drone imagery and crop surface model, a case study from Nepal. Drones 2020, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, A.; Allen, F.L.; English, B.C. Genetic progress in soybean of the U.S. Midsouth. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, F.H.; Riche, A.B.; Michalski, A.; Castle, M.; Wooster, M.J.; Hawkesford, M.J. High-throughput field phenotyping of wheat plant height and growth rate in field plot trials using UAV based Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Yang, M.; Fu, L.; Rasheed, A.; Zheng, B.; Xia, X.; Xiao, Y.; He, Z. Accuracy assessment of plant height using an unmanned aerial vehicle for quantitative genomic analysis in bread wheat. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, L.; Li, S.; Hui, F.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Ma, Y. Estimation of maize plant height and leaf area index dynamics using an unmanned aerial vehicle with oblique and nadir photography. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.K.; Sarkar, S. Machine learning for high-throughput stress phenotyping in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.L.; Baek, J. Image-based high-throughput phenotyping in horticultural crops. Plants 2023, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Yang, K.; Yuan, N.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Fang, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wu, X.; et al. UAV-based rice aboveground biomass estimation using a random forest model with multi-organ feature selection. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 164, 127529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ye, H.; Xu, Z.; Hu, J.; Shi, X.; Hua, S.; Yue, J.; Yang, G. Estimating maize-leaf coverage in field conditions by applying a machine learning algorithm to UAV remote sensing images. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.; Angel, Y.; Houborg, R.; Ali, S.; McCabe, M.F. A random forest machine learning approach for the retrieval of leaf chlorophyll content in wheat. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Fang, S.; Peng, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Duan, B.; Liu, J. UAV-based biomass estimation for rice-combining spectral, tin-based structural and meteorological features. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Hao, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; De Beurs, K.; He, Y.; Fu, Y.H. Comparison of different machine learning algorithms for predicting maize grain yield using UAV-based hyperspectral images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Huerta, M.; Rodriguez-Gonzalvez, P.; Rainey, K.M. Yield prediction by machine learning from UAS-based multi-sensor data fusion in soybean. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Koehler-Cole, K.; Scoby, D.; Thapa, V.R.; Basche, A.; Ge, Y. Enhancing estimation of cover crop biomass using field-based high-throughput phenotyping and machine learning models. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1277672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.M.; Schjoerring, J.K. Reflectance measurement of canopy biomass and nitrogen status in wheat crops using normalized difference vegetation indices and partial least squares regression. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Luo, J.; Jin, X.; Xu, X.; Song, X.; Yang, G. Exploring the best hyperspectral features for LAI estimation using partial least squares regression. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 6221–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, F.; Shi, B.; Chang, Q. Estimation of winter wheat plant nitrogen concentration from UAV hyperspectral remote sensing combined with machine learning methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, B.S.; Schapaugh, W.T.; An, N.; Price, K.P.; Prasad, V.; Fritz, A.K. Predicting soybean relative maturity and seed yield using canopy reflectance. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, I.; Bdolach, E.; Montekyo, Y.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Townsend, P.A.; Karnieli, A. Assessment of maize yield and phenology by drone-mounted superspectral camera. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmeier, G.; Hofer, K.; Schmidhalter, U. Mid-season prediction of grain yield and protein content of spring barley cultivars using high-throughput spectral sensing. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 90, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, F.A.; Ransom, J.K. Growing degree day calculation method comparison between two methods in the northern edge of the US corn belt. J. Serv. Climatol. 2015, 1–9. Available online: https://stateclimate.org/pdfs/journal-articles/2015_Adnan_et_al.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, P.; Đorđević, V.; Milić, S.; Petrović, K.; Miladinović, J.; Đukić, V. Prediction of soybean plant density using a machine learning model and vegetation indices extracted from RGB images taken with a UAV. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, P.; Đordević, V.; Miladinović, J.; Prodanović, S.; Ćeran, M.; Vollmann, J. High-throughput phenotyping for non-destructive estimation of soybean fresh biomass using a machine learning model and temporal UAV data. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Caret: Classification and Regression Training. R Package 2017, (Version 6.0-76.). Available online: https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/caret/html/00Index.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J.; Freidank, M.; Cai, J.; Protivinsky, T. Corrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. R Package 2013, (Version 0.73). Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Archer, E. rfPermute: Estimate Permutation p-Values for Random Forest Importance Metrics. R Package 2022, (Version 2(5):1). Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rfPermute/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Kapelner, A.; Bleich, J.; Pitkin, E. Peeking inside the black box: Visualizing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2015, 24, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C.; Casalicchio, G.; Bischl, B. iml: An R package for interpretable machine learning. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Hartling, S.; Esposito, F.; Fritschi, F.B. Soybean yield prediction from UAV using multimodal data fusion and deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, J.; Ye, H.; Ali, M.L.; Chen, P.; Nguyen, H.T. Yield estimation of soybean breeding lines under drought stress using unmanned aerial vehicle-based imagery and convolutional neural network. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 204, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.T.; Liu, W.; Olhoft, P.; Crafts-Brandner, S.J.; Pennycooke, J.C.; Christiansen, N. Soybean yield formation physiology-A foundation for precision breeding based improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 719706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gano, B.; Bhadra, S.; Vilbig, J.M.; Ahmed, N.; Sagan, V.; Shakoor, N. Drone-based imaging sensors, techniques, and applications in plant phenotyping for crop breeding: A comprehensive review. Plant Phenome J. 2024, 7, e20100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhova, E.; Zolin, Y.; Grebneva, K.; Berezina, E.; Bondarev, O.; Kior, A.; Popova, A.; Ratnitsyna, D.; Yudina, L.; Sukhov, V. Development of analytical model to describe reflectance spectra in leaves with palisade and spongy mesophyll. Plants 2024, 13, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomeo, N.J.; Rosenthal, D.M. Variable mesophyll conductance among soybean cultivars sets a tradeoff between photosynthesis and water-use-efficiency. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianquinto, G.; Orsini, F.; Fecondini, M.; Mezzetti, M.; Sambo, P.; Bona, S. A methodological approach for defining spectral indices for assessing tomato nitrogen status and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 35, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.R.; Ibitoye, R.G.; He, J.J.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.B. Photosynthetic performance and yield of intercropped maize and soybean are directly opposite under different intercropping ratios and maize planting densities interactions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 7440–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.J.; Schepers, J.S.; Shapiro, C.A.; Arneson, N.J.; Eskridge, K.M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Giesler, L.J. Characterizing soybean vigor and productivity using multiple crop canopy sensor readings. Field Crops Res. 2018, 216, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, G. Estimation of vegetation water content using hyperspectral vegetation indices: A comparison of crop water indicators in response to water stress treatments for summer maize. BMC Ecol. 2019, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanzon, I.M.; Rivera, K.J.S. Enhancing biomass partitioning and yield traits in soybean (Glycine max L.) through Bradyrhizobium sp. and molybdenum fertilization. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.S.; Qin, W. Influences of canopy architecture on relationships between various vegetation indices and LAI and Fpar: A computer simulation. Remote Sens. Rev. 1994, 10, 309–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Rakocevic, M.; Caverzan, A.; Chavarria, G. Grain yield differences of soybean cultivars due to solar radiation interception. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2795–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammi, S.A.; Huang, Y.; Feng, G.; Tewolde, H.; Zhang, X.; Jenkins, J.; Shankle, M. Application of UAV multispectral imaging to monitor soybean growth with yield prediction through machine learning. Agronomy 2024, 14, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Li, D.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Shao, M.; Guo, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; et al. Estimation of soybean yield parameters under lodging conditions using RGB information from unmanned aerial vehicles. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1012293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, H.B.; Xu, X.Q.; He, J.Y.; Ge, X.K.; Yao, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.X.; Tian, Y.C. Predicting grain yield in rice using multi-temporal vegetation indices from UAV-based multispectral and digital imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 130, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.B.M.; Thai, T.T.; Mansoor, S.; Le, A.T.; Baloch, F.S.; Chung, Y.S.; Kim, D.W. The use of RGB vegetation indices to predict the buckwheat yield at the flowering stage. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 28, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Anderson, M.; Daughtry, C.; Johnson, D. Assessing the variability of corn and soybean yields in central Iowa using high spatiotemporal resolution multi-satellite imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.R.; Clay, S.A.; Sharma, P.; Rekabdarkolaee, H.M.; Kharel, T.; Rizzo, D.M.; Thapa, R.; Clay, D.E. Artificial intelligence and satellite-based remote sensing can be used to predict soybean (Glycine Max) yield. Agron. J. 2023, 116, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, J.; Jia, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, W. Sorghum yield prediction using UAV multispectral imaging and stacking ensemble learning in arid regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1636015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, I.; Hall, O.; Jirström, M. Remote sensing of yields: Application of UAV imagery derived NDVI for estimating maize vigor and yields in complex farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Drones 2018, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hendawy, S.; Alotaibi, M.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Al-Gaadi, K.; Hassan, W.; Dewir, Y.H.; Emam, M.A.E.-G.; Elsayed, S.; Schmidhalter, U. Comparative performance of spectral reflectance indices and multivariate modeling for assessing agronomic parameters in advanced spring wheat lines under two contrasting irrigation regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.