Abstract

In the Republic of Moldova, orchard biomass represents an important resource for the production of densified solid biofuels, with peach having the highest sustainable energy potential (33.5 ± 6.54 GJ·ha−1). However, the quality of solid biofuels derived from orchard biomass is often constrained by heterogeneity in moisture content, uneven particle size distribution, and inadequate drying or blending practices along the supply chain. Optimizing the solid biofuel supply chain is therefore essential to minimize feedstock variability, ensure consistent densification quality, and reduce production costs. The aim of this study was to improve the process of producing densified solid biofuels from orchard biomass. Specifically, the study investigated how raw material moisture and particle size influence briquette density and durability, and how ternary mixtures of peach biomass, wheat straw, and sunflower residues can be optimized for enhanced energy performance. All experimental determinations were performed using validated methods and calibrated equipment. The results showed that optimal performance is achieved by shredding the biomass with 4–8 mm sieves and maintaining the moisture content between 6 and 14%, resulting in briquettes with the density of 1.00–1.05 g·cm−3, ash content below 3–5%, and an energy yield of 18.4–19.2 MJ·kg−1. Ternary diagrams confirmed the decisive role of peach lignocellulosic residues in achieving high density, low ash content, and increased energy yield, while wheat straw and sunflower residues can be used in controlled proportions to diversify resources and reduce costs. These findings provide quantitative insights into how mixture formulation and process parameters influence the briquette quality, contributing to the optimization of solid biofuel supply chains for orchard and agricultural residues. Overall, this study demonstrates that competitive solid biofuels can be produced through careful balancing of mixture composition and optimization of technological parameters, offering practical guidelines for sustainable bioenergy development in regions with abundant orchard residues.

1. Introduction

In the context of the worsening global energy crisis, the Republic of Moldova faces an increasingly pressing challenge: ensuring energy security during a period marked by vulnerability due to dependence on external sources, particularly Russian natural gas. This situation assigns a strategic urgency to the commitment toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 7 (ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all) and SDG 13 (taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts) [1].

The implementation of these goals is supported by a series of policies and strategic documents aimed at promoting renewable energy sources in the Republic of Moldova. Among these are the Energy Strategy of the Republic of Moldova until 2030 [2] and the Energy Strategy of the Republic of Moldova until 2050 [3], which prioritize the assurance of energy security, the increase in energy efficiency, and the diversification of energy sources. These strategies emphasize the use of renewable energy and the reduction in import dependence, proposing a transition toward a sustainable energy system.

Thus, the valorization of renewable sources, adapted to the specific conditions of the Republic of Moldova, represents not only an ecological necessity but also a driver of sustainable development, strengthening economic resilience and aligning with European standards [3].

One of the most well-known and long-standing renewable energy sources used by humankind is biomass [4], including agricultural residues [5], which are abundant and environmentally friendly [6], and are capable of reducing dependence on fossil resources and contributing to energy security [7]. In the Republic of Moldova, one of the most accessible biomass sources for the production of densified solid biofuels (DSBF) is orchard biomass, particularly that resulting from the cultivation of fruit trees and shrubs [8,9].

As a rule, the raw material used in producing briquettes from orchard biomass consists of residues from pruning for crown formation and maintenance, annual fruiting pruning, thinning of trees, removal of dry or disease- and pest-affected branches, clearance of trees at the end of their productive cycle [10,11,12], as well as residues from the production of fruit tree seedlings [11].

Orchard residues are distinguished by favorable energy parameters, particularly their high lignocellulosic content and significant calorific value [8,10]. These characteristics provide them with a high potential for energy valorization, making them suitable both for direct use and for conversion into DSBF such as pellets and briquettes [12]. Therefore, orchard biomass represents an accessible and promising resource for diversifying renewable energy sources and enhancing the sustainability of the horticultural sector.

The energy efficiency, sustainability, economic viability, and market accessibility of DSBFs obtained from this biomass largely depend on their quality, which must comply with technical and environmental standards [13,14,15]. In this context, the optimal functioning of each link in the solid biofuels supply chain (SBSC)—defined as the set of processes, material flows, information, and resources involved in the collection, transportation, processing, storage, and distribution of biomass up to its delivery to the final consumer—is essential.

The main links of this chain include: the production and collection of raw materials; transportation and intermediate storage; pre-processing (drying, shredding, sorting); densification (pellet and briquette production); final storage and distribution to end users; and, ultimately, the utilization by the final consumer (heating plants, industrial boilers, households) [16,17]. The entire flow—from biomass harvesting and handling to final use —plays a decisive role in ensuring the quality of the end product [17].

Although numerous studies have examined the production of solid biofuels from various lignocellulosic materials [10,18,19,20,21], including investigations focused on their energy potential [5,11,22], few have addressed the optimization of the SBSC for orchard biomass—particularly peach residues—under real production conditions. Most existing studies analyze isolated stages of the process, such as raw material composition and moisture content [23], or feeding rate and die temperature [24], without proposing an integrated approach that links raw material characteristics, mixture optimization, and technological parameters.

The scientific novelty of this study lies in the development of an integrated framework that connects feedstock properties, ternary mixture optimization, and technological parameters to enhance the production of DSBF from peach pruning residues—a biomass type largely overlooked in previous research. By applying ternary diagrams to determine optimal mixture compositions of peach, wheat straw (WS), and sunflower residues (SFR), and by experimentally establishing the optimal moisture content and particle size ranges for densification, this study provides original quantitative insights that significantly advance the understanding and practical optimization of SBSCs based on orchard biomass.

A well-organized SBSC guarantees not only supply continuity but also uniform quality of the raw material and final product, as well as the technological consistency of biomass conditioning and DSBF production.

At the same time, the quality of biofuels is determined by several factors directly related to SBSC management: origin and characteristics of the raw material; blending; conditioning of raw material before processing; and establishment of technological regimes.

Origin and Characteristics of Raw Material. The logistics of raw material supply represents one of the key links in the solid biofuel supply chain, aiming to ensure efficient and timely deliveries to biomass consumption points [25]. In this context, it is essential to understand the characteristics and energy potential of the biomass available for energy purposes. Among the parameters of major interest for solid biofuel producers are calorific value, moisture content, and ash content.

Different species of orchard biomass show significant variations in moisture, ash content, and calorific value [26], parameters that directly influence the performance of the final product. It is also necessary to take into account the sustainable energy potential available in the areas adjacent to solid biofuel production enterprises [27].

Conditioning of Raw Material Before Processing. The stages of drying, shredding, and homogenization must be organized in such a way as to reduce the variability of the initial biomass parameters and to increase the efficiency of the densification process.

The physical state of vegetal biomass prior to densification is mainly determined by two essential parameters, which are often overlooked by solid biofuel producers, although they exert a major influence on the quality of the final product. These are the particle size of the raw material and its moisture content [28].

Particle size represents a critical characteristic of the raw material, influencing reaction mechanisms, process kinetics, and the formation of intermolecular adhesion bonds between different substances, as well as cohesion between similar particles. All these factors directly limit the quality of briquettes [29] and pellets [30,31,32].

Mixture Formation. For efficient and sustainable production of solid biofuels, the biomass used as raw material must be available and suitable, as well as easy to collect, transport, and store for further processing before densification [33]. Agricultural biomass is one option; however, there are concerns about the potential competitive impact of its use for bioenergy purposes on other applications, such as food and feed production [34]. Reservations have also been raised regarding the direct use of orchard biomass, since in many cases its characteristics do not meet the parameters required by current standards regarding the quality of the final product [35,36,37].

In this context, there is a need for efficient and accessible procedures for solid biofuel producers, capable of ensuring compliance of the final product with the requirements of the SM EN ISO 17225 standard family [38,39,40,41,42]. Optimization of raw material composition is one of the most frequently used and most accessible methods in the densified solid biofuel industry. However, in many cases, producers lack clear recommendations regarding the types of permitted additives and the quality of the final product obtained from biomass mixtures. Another essential aspect is the proportion of the components and, evidently, their availability in the proximity of biofuel production enterprises.

In the Republic of Moldova, almost all economic development regions have significant amounts of WS and SFR [43], which can be efficiently used as raw material for DSBF production.

The integration of straw into raw material mixtures for briquette manufacturing presents both advantages and limitations. On the one hand, straw can be used to obtain DSBF with a high content of volatiles and carbon, and in most cases does not require pre-drying before densification [44]. On the other hand, it produces a considerable amount of ash during combustion, characterized by a relatively low melting temperature, and its chemical composition varies significantly depending on soil type, climatic conditions, and cultivation area [45]. The associated limitations—particularly the high ash content and its low melting temperature—can be compensated by combining it with orchard biomass, which has other advantageous properties.

SFR appear after harvesting the main crop and generally consist of a mixture of stems and fragmented heads. In addition, the oil industry generates a significant number of seed husks. Research on the use of sunflower harvesting residues (heads and stems) as raw material for producing DSBF has shown that they are not recommended for use alone in the manufacture of briquettes and pellets [46,47]. For this reason, data on the valorization of these residues remain modest, and their use in pellet production is almost non-existent. This situation is explained by the high moisture content of the material at harvest, its relatively low calorific value, and the high ash yield during combustion. Nevertheless, given the considerable volume of such residues, their use as an additive in mixtures of orchard and vineyard biomass is justified.

Unlike residues in the form of heads and stems, sunflower seed husks are widely used for both briquette and pellet production. Their extensive use has been reported by numerous authors from Moldova’s neighboring countries, such as Romania [18,48,49] and Ukraine [50,51], who highlight the advantages of sunflower seed husks as a reliable source for densified solid biofuel production.

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that, for efficient DSBF production from orchard residues, the raw material must be not only technically suitable but also available in sufficient quantities, and easy to collect and store. In this context, integrating straw and SFR into mixtures with orchard biomass capitalizes on abundant and accessible agricultural resources and contributes to balancing the properties of the resulting solid fuels, facilitating their compliance with international quality standards.

Establishing Technological Regimes. One of the essential links in the SBSC is the densification conditions, where the matrix temperature and biomass moisture content play a decisive role [28,33]. These factors influence the agglomeration process through the occurrence and intensity of cohesion and adhesion forces between particles [32,52].

Numerous studies highlight that the optimal briquetting temperature is around 120–140 °C, regardless of the biomass type [53,54,55]. However, the values may vary: the temperature can be reduced at high pressures [56], or increased up to 150–250 °C to improve density, calorific value, volatile matter content, and briquette stability [57]. These effects are explained by particle plastification and lignin activation [52,58].

For screw presses, higher temperatures are recommended, without exceeding the thresholds at which biomass degradation occurs [24]. Conversely, for briquettes produced from corn cobs, densification has been reported at very low temperatures (20–80 °C), with the optimal temperature being approximately 80 °C [59].

Based on the previous information, it can be concluded that the literature presents a wide variety of results, with briquetting temperature ranges reported between 20 °C and 250 °C. This variation is due to differences in biomass types, compositional features, and densification technologies used. For these reasons, there is an evident need for in-depth studies to establish optimal technological regimes adapted to each type of biomass and technological context, in order to increase process efficiency and the quality of the final products.

Overall, the analysis of the literature and the specific features of the resources available in the Republic of Moldova reveal that the DSBF supply chain is complex and strongly influenced by multiple variables—from the origin and characteristics of the biomass to the conditions of processing, mixing, and densification. Each stage of this chain directly determines the quality of the final product, energy yield, and the economic competitiveness of the process.

The wide diversity of results reported in international literature, along with the lack of uniform technological recommendations for different types of biomass, justifies the need for systematic and in-depth studies under real production conditions. Special attention must be given to critical stages such as selection and characterization of raw material, optimization of initial conditioning (drying, shredding, sorting), formulation of balanced mixtures from different plant sources, and establishment of technological regimes for densification.

Therefore, the detailed study of each link in the DSBF supply chain represents not only a prerequisite for improving the performance and quality of the biofuels produced but also an essential step toward ensuring energy sustainability and aligning with strategic objectives of the transition to a green and resilient energy system.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to improve the production process of densified solid biofuels derived from orchard biomass. The main objectives were: to determine the potential of orchard plant biomass suitable for producing DSBF under the conditions of the Republic of Moldova; to establish the optimal condition of the biomass prior to processing by analyzing the effect of particle size and moisture content on the densification capacity of DSBF; to investigate possibilities for improving DSBF by formulating mixtures using peach pruning residues in combination with WS and SFR, which are abundant in the Republic of Moldova; and to determine the technological densification regimes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Experimental Design

The study was carried out in several stages, the first of which involved assessing the availability and potential of orchard biomass for the production of DSBF. Biomass samples were collected in accordance with SM EN ISO 18135 [60] from representative residues generated during maintenance pruning of fruit trees, nut trees, and berry shrubs.

The biomass was manually collected immediately after pruning during 2023–2024 from orchards and plantations located in different regions of the Republic of Moldova (LLC DIAMAX-Agro, LLC POMRUBUS, LLC MONSTERAX-GSG, II Vasile Tațu, LLC ECO NUTS ENERGY, as well as individual households from the localities of Trușeni and Todirești).

The mass of the sampled material was measured immediately after collection using an ACEN 50 K balance (measurement range 0.1–50 kg, 10 g division), internally calibrated with certified 200 g and 2 kg weights. Prior to weighing, the biomass was coarsely shredded in the field using a Muréna 1 mobile woodchipper (Bystroň–Integrace Ltd., Valašské Meziříčí, Czech Republic). A portion of samples was stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture exchange and transported to the laboratory for determination of moisture content at collection and for subsequent physical and chemical analyses.

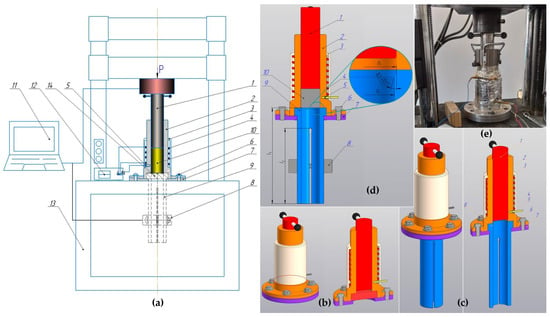

In the second stage, the influence of particle size and raw material moisture on the densification capacity was analyzed. The study was conducted on nine briquette samples, produced with the Briklis hydraulic press model BrikStar CS 25 (manufactured by the Briklis company, Malšice, Czech Republic) equipped with a hydraulic compaction system at the Solid Biofuels Scientific Laboratory of the Technical University of Moldova (SBSL TUM) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequences during briquette production with the Briklis press and monitoring of die temperature using the FLIR TG297 Automotive Diagnostic Thermal Camera (FLIR Systems, Inc., Wilsonville, Oregon, USA).

The raw material consisted of predominantly one- and two-year-old peach branches, naturally dried in the field and subsequently transported to SBSL after coarse grinding. In the laboratory, the material was subjected to the conditioning process according to the randomized three-level (32) multifactorial experimental design presented in Table 1. The experimental results were statistically processed using the STATGRAPHICS Centurion software, version 18. Particle density and briquette durability were considered as response variables.

Table 1.

Experimental set used to evaluate the effect of particle size and moisture content on the density and durability of briquettes produced from peach residues.

In the third stage, the main objective was to improve the quality of briquettes obtained from orchard biomass by optimizing the supply chain. The research focused on forming mixtures from different types of biomass and on optimizing technological regimes.

To study the effects of mixture formation, ten briquette samples were analyzed and tested. The briquettes were produced with the Briklis hydraulic press and were comprised both from mixtures with varying mass proportions of the components and from each component used individually. Peach lignocellulosic biomass (PLCB) was used as the main raw material, while WS and SFR served as secondary materials. The experiments were carried out according to the multifactorial design presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Biomass blend compositions (PLCB, WS, SFR) used in the experiments for evaluating briquette quality.

Each experiment was repeated five times. The quality of the samples was evaluated by determining the following indicators: gross calorific value at constant volume, ash content, particle density, and mechanical durability.

The final, fourth stage focused on investigating the influence of densification regimes on the quality of the briquettes. The technological factors analyzed were the die temperature and the moisture content of the raw material. The need for this study is justified by the intention to clarify certain findings formulated in the second stage, which was carried out on the Briklis hydraulic press used in industrial production and aimed at optimizing the pre-conditioning parameters of the raw material prior to densification—particle size and initial moisture content. These parameters directly affect the quality of the material entering the press and are essential for producers operating commercial briquetting equipment, where the die temperature cannot be adjusted.

The study on the influence of biomass densification regimes was carried out using an original patented laboratory installation (MD 1734 Y 10.01.2023) [61], shown in Figure 2. The device allows briquetting both in a closed cavity and in continuous flow. It is mounted on a hydraulic press and includes a compression piston, a die with two chambers (upper and lower), a heating element with temperature control, and a computer-connected monitoring system.

Figure 2.

General view and schematic diagram of the device used for studying the densification process of plant biomass into briquettes: (a) general scheme; (b) briquetting process in a closed cavity; (c,d) briquetting process in continuous flow; (e) real view photo. 1—piston; 2—upper chamber; 3—die; 4—heating element; 5—thermocouple; 6—fastening screws for attaching the device to the hydraulic press; 7—support plate; 8—limiting ring with strain gauge for pressure measurement; 9—lower chamber; 10—biomass during compaction; 11—computer for recording and managing compaction regimes; 12—temperature monitoring unit; 13—hydraulic press; 14—removable plug.

The upper chamber is heated and equipped with a temperature measurement unit, while the lower chamber has a special geometry consisting of a guiding cone and a calibration element with longitudinal cuts, equipped with a limiting ring and a pressure transducer. Depending on the configuration, compaction is carried out either in a blocked cavity with a removable plug or by continuous extrusion of briquettes.

This design makes it possible to investigate the influence of pressure, temperature, compaction speed, and biomass characteristics on densification.

The experiments were performed using a three-level factorial design of type 32 (Table 3). The influencing factors were the die temperature (T) and the moisture content of the raw material before densification (M).

Table 3.

Experimental set used to assess the effect of die temperature and raw material moisture on the densification of peach biomass.

In this study, the moisture content of the raw material was reintroduced as an influencing factor because it must be assessed in interaction with the die temperature—a decisive parameter for briquetting systems with heated dies (screw presses, electrically heated dies, or induction-heated matrices). The inclusion of moisture content in both the second and fourth stages is not redundant but reflects the distinct roles of this parameter within the process: in the second stage—as an indicator of the raw material condition prior to processing, and in the fourth stage—as a factor governing thermoplastic mechanisms and the formation of inter-particle bonds depending on die temperature.

2.2. Laboratory Analyses

The laboratory analyses were conducted at the Scientific Laboratory of Solid Biofuels, Technical University of Moldova (SLSBF TUM), using validated specific methods, accredited by the National Accreditation Center of the Republic of Moldova (MOLDAC), Decision No. 90 of 27 May 2025 (https://acreditare.md/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/LI-139-Biocombustibili-Solizi-27.05.2025.signed.pdf) (accessed on 2 October 2025).

The combustion properties of the samples were determined through the qV,gr,d, the net calorific value on a dry basis at constant pressure (qp,net,d), and the net calorific value at a given moisture content (qp,net,M). The net calorific value was calculated by subtracting the heat released during phase transitions of vaporization from the gross calorific value, according to the following equation:

where w(H)d, w(O)d, w(N)d, w(N)d are the mass fractions of hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen in the dry state (%).

The net calorific value at a given moisture content was estimated as:

where M is the moisture content (%).

The gross calorific value was measured using an IKA C6000 isoperibolic calorimeter under constant volume conditions. Prior to testing, the samples were ground with a Retsch SM 100 hammer mill fitted with a 1 mm sieve. Sample mass was measured using a RADWAG AS 220/C/2 analytical balance Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Equipment used for biomass testing: (a) biomass samples before shredding; (b) Memmert UNB 500 thermostatic chamber (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany); (c) Retsch SM 100 hammer mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany); (d) RADWAG AS 220/C/2 analytical balance (Redwag, Radom, Poland); (e) milled samples for calorific value determination; (f) IKA C6000 isoperibolic calorimeter (IKA, Staufen, Germany).

All biomass samples used for calorific value determination were oven-dried in a Memmert UNB 500 thermostatically controlled drying chamber. This equipment, including a ventilation system and a temperature monitoring unit, ensured stable conditions within the limits prescribed by the standards.

The methods were selected to ensure a rigorous assessment of both the energetic potential and the physico-chemical properties of the biomass.

Moisture content was determined using the simplified total method with oven drying (SM EN ISO 18134-2:2024) [62] and the general method (SM EN ISO 18134-3:2017) [63]. The first method was primarily applied to assess the moisture content of biomass at the time of collection or prior to processing, while the second method was used for evaluating the quality of final products and for analyzing process factors.

The tests were carried out on samples that had been pre-ground with a Retsch SM 100 hammer mill and pre-dried in a Memmert UNB 500 thermostatically controlled drying oven.

Ash content, expressed on a dry basis, was determined in accordance with SM EN 18122:2023 [64], by the slow ashing of samples in an LAC LH 05/13 electric muffle furnace (LAC, Židlochovice, Czech Republic) at 550 °C for at least 6 h. Samples intended for ash determination were prepared according to SM EN 14780:2017 [65] and had a nominal particle size of ≤1 mm, ensured by sieving through a calibrated screen with 1 mm openings.

Particle density was determined by the stereometric method in compliance with SM EN ISO 18847:2017 [66], while mechanical durability was evaluated in accordance with SM EN ISO 17831-2:2017 [67].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Availability and Potential of Biomass for DSBF Production

Table 4 presents the results of the statistical analysis of orchard biomass samples available for DSBF production under the conditions of the Republic of Moldova using the SLSBF TUM. Some of these were compared with data previously published by our research team [9,13,68,69] to validate and confirm the identified trends. For each fruit species, the mean values and standard deviations were calculated based on at least six different cultivars.

Table 4.

Properties of biomass from fruit tree species and berry shrubs used as raw material for DSBF production.

The table shows the mean values for each analyzed orchard crop cultivar, as well as the corresponding standard deviations. For each fruit species, at least six different cultivars were considered, providing a solid statistical basis and high representativeness of the results.

It was observed that the variation in biomass moisture content was insignificant. For example, fruit trees and shrubs have a stable harvesting moisture content, ranging from 43.2 ± 0.5% (apple) to 47.9 ± 0.12% (gooseberry). This consistency suggests good predictability of their behavior during drying and densification processes. In contrast, almond, with a higher initial moisture content (51.0 ± 5.7%), requires an additional conditioning step to avoid excessive energy consumption during processing.

Based on the results, the ash content varies considerably, from 1.40% (hazelnut) to 5.49% (walnut); similarly, Bilandzija et al., 2012 [70] found variations in ash in thirteen horticultural species studied in Croatia, from 1.52% (apple) to 5.39% (walnut). However, most fruit and shrub species show moderate values (≈2–3%), corresponding to biomass of good energetic quality. The study from Germany [71], focused on characterization of different cultivars of apple, pear and plum, published slightly higher average ash content of 3.48 ± 1.53%. The high ash content of walnut biomass can negatively affect energy yield and combustion behavior, generating deposits and slagging risk. In such cases, blending walnut biomass with other low-ash species (e.g., hazelnut, peach, sea buckthorn) is an effective solution for producing higher-quality solid biofuels.

From an energy perspective, the net calorific value, determined at a reference moisture content of 10%, ranges between 14.95 MJ·kg−1 (black mulberry) and 17.14 MJ·kg−1 (sea buckthorn). Most of the analyzed species showed very similar values and fall within the range of 15.5–16.0 MJ·kg−1, values comparable to those reported even for hardwood biomass, such as beech ≈15.8 MJ·kg−1 [72] or acacia ≈16.8 MJ·kg−1 [73], which are widely used in briquette and pellet production. Other study on orchard wood biomass [70], also found that the net calorific values of the species are relatively similar, varying from 15.60 MJ·kg−1 dry basis (fig) to 17.73 MJ·kg−1 dry basis (peach and nectarine). Species with higher values, such as sea buckthorn or peach, highlight a strong potential for obtaining high-quality solid biofuels, confirming the competitiveness of fruit tree biomass compared to conventional woody energy resources.

Correlating these results with the research objective highlights the fact that the diversity of fruit tree biomass in the Republic of Moldova requires a differentiated approach in the technological flow. Thus:

- for species with high moisture content (e.g., almond), the integration of efficient drying and pre-conditioning stages is indispensable;

- for species with high ash content (e.g., walnut), the use of blending recipes with other types of biomass is recommended in order to obtain biofuels with optimal quality parameters;

- species with high calorific value and low ash content (e.g., sea buckthorn, hazelnut, peach, apricot) can be used as the main raw material for the production of high-quality solid biofuels.

In conclusion, the analysis of fruit tree biomass parameters confirms the importance of optimizing the production flow through appropriate raw material selection, the application of differentiated conditioning strategies, and the establishment of balanced mixtures. These measures contribute to ensuring the quality of solid biofuels and increasing their competitiveness in the energy market.

With regard to the energy potential of fruit tree biomass, our findings are consistent with other studies [70,71], which highlight the existence of a significant fruit tree biomass potential that can be used as raw material for DSBF.

Table 5 presents the energy potential of fruit tree residues in relation to one hectare of orchard. The calculations for the analyzed species were carried out based on the calorific values of the biomass. Both the theoretical energy potential (TEP)—determined as the product of the average biomass obtained from pruning operations and collected per hectare, estimated at a moisture content of 10%, and the net calorific value corresponding to the same moisture level—and the sustainable energy potential (SEP), obtained by adjusting the theoretical values with factors reflecting technical losses, logistical constraints, and ecological limitations, are presented.

Table 5.

Theoretical and sustainable energy potential of biomass derived from fruit tree residues, expressed per hectare.

Table 5 highlights clear differences among the fruit tree species in terms of energy potential. Peach shows the highest values, both for theoretical potential (46.53 ± 9.08 GJ·ha−1) and sustainable potential (33.5 ± 6.54 GJ·ha−1), followed closely by apple and pear. At the opposite end, quince and apricot record the lowest values, which limit their attractiveness as energy resources. Thus, the higher energy level of peach biomass justifies its selection for the case study on optimizing the supply chain of DSBF.

Having established the initial properties of the fruit tree biomass and its energy potential, the next step consisted in optimizing the conditioning process to ensure adequate performance during the densification stage.

3.2. Conditioning of Raw Material Before Processing

The purpose of this stage of the study is to analyze the effect of grinding size and moisture content on the densification capacity of SBF using Nestor-type briquettes, densified from peach biomass grown in the southern area of the Republic of Moldova.

The results below show the interaction between particle size and moisture content of the raw material before the processing, and the densification capacity of the briquettes produced from PLCB.

As a result of the statistical processing of the experimental data, carried out in accordance with the plan presented in Table 1, the following regression equation was obtained:

The equation describes the influence of moisture content (M) and particle size (D) on the particle density of briquettes made from peach biomass (DE). The model includes linear, quadratic, and interaction effects, suggesting a complex dependence between the analyzed variables.

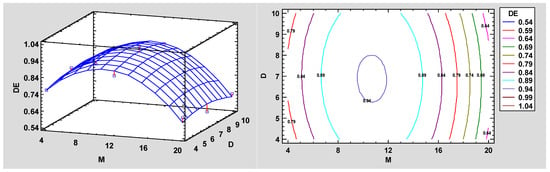

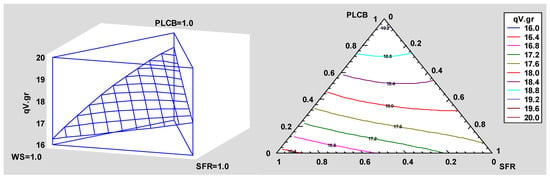

The response surfaces and contour plots (Figure 4) highlight that particle density increases significantly with rising moisture content of the raw material, reaching optimal values within an intermediate range (M ≈ 9–12%). Particle size affects density in a similar but less pronounced way, with maximum values recorded in the range of D ≈ 6–8 mm. At excessive moisture levels (M > 16%) or in the case of oversized particles (D > 10 mm), briquette density decreases, a trend confirmed by the negative coefficients of the squared terms (M2 and D2).

Figure 4.

Estimated response surface and contour plots illustrating the influence of moisture content (M) and particle size (D) on the particle density (DE) of PLCB briquettes. The regression model was statistically significant according to ANOVA (F = 16.30, p = 0.0273; see Table A1).

The variability analysis was performed using ANOVA, a method that employs the F-test and the p-value to assess the statistical significance of factors. According to the criterion p < 0.05, a factor has a significant effect on the outcome, whereas for p ≥ 0.05 the effect is not considered relevant. The statistical model obtained for DE exhibits very high accuracy, explaining 95.8% of the data variability (R2 = 0.958), indicating a very good correspondence between the model and the actual behavior of the densification process.

The ANOVA results show that moisture (A:M) has a significant effect on density (p = 0.0273), while particle size (B:D) does not significantly influence the outcome within the tested range (p = 0.8598). The quadratic term of moisture (AA) is highly significant, indicating the existence of an optimal moisture range prior to densification, outside of which density decreases. The interaction between moisture and particle size is not significant (AB, p = 0.8290), suggesting that the two factors act independently.

The robustness of the model is confirmed by the low standard error (SE = 0.042), the absence of residual autocorrelation according to the Durbin–Watson test (DW = 1.86, p = 0.6123), and the near-zero first-order autocorrelation (lag 1 ≈ 0), demonstrating the random distribution of errors and the statistical validity of the model.

This behavior can be explained by the physico-mechanical mechanisms of the densification process. At moderate moisture values, water acts as a plasticizer, facilitating the migration of lignin and improving the structural cohesion of the particles. At the same time, an optimal particle size allows the formation of effective surface contacts, favoring compaction. Conversely, excessive moisture reduces mechanical strength due to vapor accumulation at the outlet, while overly fine particles may increase friction forces and even cause die blockage, whereas oversized particles generate voids in the briquette structure.

Large particle sizes (D > 10 mm), combined with high moisture content (M > 16%), lead to reduced particle densification, which results in briquettes with low density, porous structure, and discontinuities both inside the briquettes and on their surface.

Very fine particles (D < 4 mm), although they promote uniform compaction, cause a slow increase in particle density and may result in higher energy consumption and agglomeration tendencies, reducing the homogeneity of the briquettes.

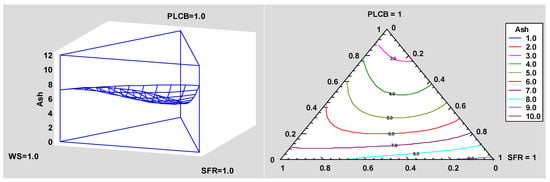

A complex dependence of the mechanical durability (DU) on the investigated technological parameters—moisture content and particle size—is expressed by Equation (4).

The mathematical model shows that DU is positively influenced by a moderate increase in moisture content but decreases with the increase in particle size. The interaction terms (M·D) and the second-order terms (M2 and D2) indicate that the relationship is not linear but exhibits optimal operating regions. The response surface analysis (Figure 5) confirms these trends.

Figure 5.

Estimated response surface and contour plots illustrating the influence of moisture content and particle size on the mechanical durability (DU) of PLCB. The model showed partial statistical significance (F = 0.11, p = 0.7664), with moderate predictive accuracy (R2 adj. = 82.0315%; see Table A2).

Maximum values of mechanical durability are obtained within the relatively wide range of particle sizes of 5–10 mm and at a moderate moisture content (approx. 10–14%) and can exceed 90%. This outcome can be explained by the more efficient compaction of fine particles, which facilitates the formation of mechanical and thermoplastic bonds during the pressing process.

At very low moisture content (<6%), durability decreases significantly, suggesting that the lack of water limits lignin plasticization and the formation of internal bonds, leading to a more fragile briquette structure. At the opposite extreme, at high moisture content (>16%), durability is reduced, most likely due to the increased pressure of vapors and the occurrence of internal cracks during cooling and drying.

In addition, particles with larger dimensions (>10 mm) produce briquettes with lower durability, even under optimal moisture conditions. This confirms that particle size reduction is an essential requirement for achieving a uniform internal density and enhanced resistance to mechanical stress.

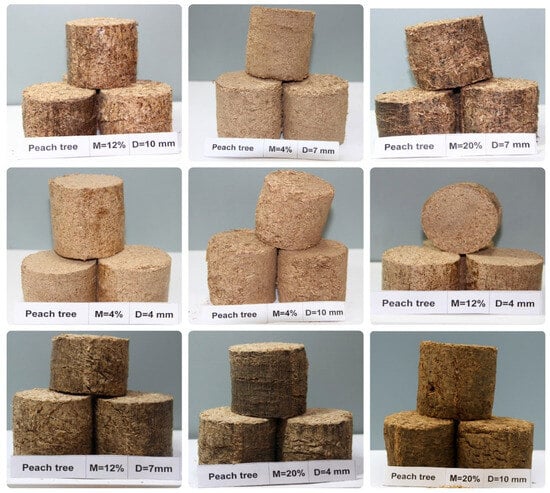

The results of statistical modeling, reflected in Equations (3) and (4) and illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5, are supported by experimental observations of the briquettes.

Figure 6 shows the visual appearance of the tested samples, where differences in structure and homogeneity can be observed as a result of variations in moisture content and particle size. Thus, briquettes produced within the optimal range of technological parameters display a dense and uniform structure, whereas deviations from this range lead to porosity, cracking, and reduced mechanical strength. This representation confirms, in a practical manner, the trends highlighted by the mathematical models and response surfaces.

Figure 6.

Comparison of briquette samples produced according to the parameters in Table 1.

In conclusion, it can be stated that rigorous control of particle size and moisture content of the raw material is an essential condition for obtaining high-quality DSBF. To ensure a stable and compact structure of the briquettes, it is recommended to use sieves with a 4–8 mm mesh during biomass shredding, while maintaining the moisture content within the optimal range of 6–14%.

The results obtained are consistent with the literature, which indicates the existence of an optimal range of moisture content (8–12%) and particle size (below 8 mm) for producing briquettes with high density and durability, such as those from wood and herbaceous biomass [74], sawdust [75], ground sunflower stalks and hazelnut shells [76], energy crops [77], or recycled residues from pruning of Ficus Nitida trees [78]. Therefore, the response surfaces confirm that maximum performance is achieved when a balance between processing parameters is maintained, emphasizing the importance of fine-tuning raw material preparation conditions.

Considering the data obtained in this subsection, and given that, for the efficient use of raw materials available in certain localities, producers most often resort to using various biomass mixtures as primary feedstock, the next step focused on investigating the quality of the final products in the form of briquettes produced from PLCB-based mixtures.

3.3. Formulation of Orchard Biomass-Based Blends: Case Study for Peach Biomass, Wheat Straw, and Sunflower Residues

The main objective of this study was to develop recommendations for solid biofuel producers regarding the formulation of biomass blends based on orchard residues, combined with abundantly available agricultural biomass in the Republic of Moldova, namely WS and SFR. The research was carried out as a case study according to the program presented in Table 2, using the plant residues resulting from peach pruning as the primary raw material.

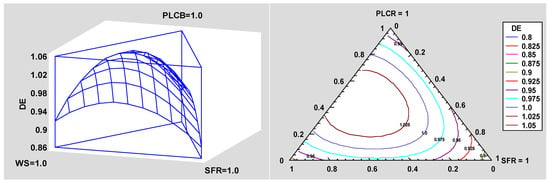

Regression equations were derived and ternary diagrams were constructed, which allow us to monitor the dynamics of quality change in the samples depending on the proportions of the components used in the raw material blends.

The regression model for the qV.gr efficiently quantifies the individual and interaction contributions of the mixture components to the energy content of the produced briquettes:

1 The values for the mass content of the components are expressed in relative coordinates (e.g., 30% ≈ 0.3), and the sum of all components must not exceed 100% ≈ 1.

The magnitude and sign of the coefficients in Equation (5) allow for a well-grounded mechanistic and practical interpretation. Firstly, the significant positive main effect associated with PLCB (19.3381) highlights that woody residues from peach pruning contribute more energy per unit mass than the other two analyzed feedstocks. This finding is consistent with calorific values reported in the literature for peach biomass, which are often comparable to or even higher than typical values for woody biomass. The obtained results are also supported by the data in Table 4, showing that the net calorific value of peach residues, determined at a reference moisture content of 10%, ranges between 15.64 and 16.36 MJ·kg−1. Recalculated for qV.gr, these values correspond to a range of approximately 19–20 MJ·kg−1.

In contrast, WS and SFR exhibit positive but smaller effects (16.261 and 17.491, respectively), with values falling within the typical ranges for WS and sunflower husks (≈15–18 MJ·kg−1, depending on moisture and ash content) [79].

Secondly, the interaction terms reveal non-additive behaviors that are important for mixture formulation. The positive interaction PLCB·WS (+1.3521) indicates a slight synergistic effect, suggesting good compatibility between these two biomasses—likely due to complementary properties that enhance the effective energy value of the mixture. Conversely, the negative coefficient for PLCB·SFR (−0.3579) indicates a mild antagonistic effect, suggesting reduced performance when these two feedstocks are combined. The WS·SFR term is very small and negative (−0.0943), indicating an almost additive effect with a slight adverse tendency.

Thirdly—and most importantly—the positive ternary interaction (+3.8705) demonstrates a significant synergistic effect when all three types of biomass are combined. This term shows that certain balanced mixtures produce qV.gr values higher than those estimated from simple additive or binary effects. The ternary synergy can be explained by particle complementarity (leading to better apparent density), thermal behavior during compaction (more efficient binding of volatile fractions), and mutual dilution of high-ash fractions.

Figure 7 presents the ternary diagram illustrating the variation in the gross calorific value qV.gr (MJ·kg−1) of the briquettes as a function of the mass fractions of PLCB, WS, and SFR. Each point represents a unique composition expressed in relative coordinates (e.g., 0.2 ≈ 20%), with the sum of the three components equal to 1. The fraction of each component is determined by projecting the point along lines drawn parallel to the side opposite the corresponding vertex. The colored regions indicate the estimated qV.gr values, with more intense shades corresponding to higher calorific values.

Figure 7.

Ternary diagram illustrating the variation in the qV.gr (MJ·kg−1), of briquettes as a function of the mass proportions of PLCB, SFR, and WS. The data points are plotted in relative coordinates (e.g., 0.2 ≈ 20%), which correspond to the mass percentage of each biomass component in the mixtures. The special cubic model was statistically significant (F = 9.03, p = 0.0493; see Table A3).

To illustrate how the diagram is interpreted, the composition PLCB = 0.00, WS = 0.793, and SFR = 0.207 (≈79.3% WS and 20.7% SFR) satisfies the model equation for qV.gr ≈ 16.5 MJ·kg−1 and lies on the iso-value contour corresponding to this value. The diagram thus enables the direct identification of mixture compositions that achieve the desired properties. For instance, to obtain a higher qV.gr, the appropriate mixtures should be selected from regions dominated by PLCB, complemented by moderate proportions of WS and SFR. Conversely, if other briquette characteristics are targeted (e.g., ash content or DSBF), the compositions can be chosen from the favorable regions highlighted in their respective ternary diagrams. In this way, the ternary diagrams serve as practical decision-support tools for determining the optimal component proportions according to the desired final performance.

From an applied perspective, the model provides valuable information for the formulation and optimization of biomass mixtures with respect to their energy content. However, it should be emphasized that it is valid only within the analyzed experimental range, and extrapolation beyond the studied interval may be unreliable. Furthermore, for practical application, it is essential to investigate how both the ash content and the DSBF change depending on the composition of the mixtures and the process parameters.

Equation (6) and the ternary diagram (Figure 8) indicate that PLCB plays a key role in reducing ash content, while the additions of WS and SFR lead to higher values.

Figure 8.

Ternary diagram illustrating in relative coordinates the variation in ash content (%) of briquettes depending on the mass proportions of PLCB, SFR and WS. The regression model was not statistically significant (F = 2.28, p = 0.2658) but provides useful trends for practical applications (see Table A4).

The analysis shows that only about 3.9% of the ternary domain corresponds to mixture combinations that can predictably ensure the production of briquettes with an ash content ≤ 3.0%, the threshold set by SM EN ISO 17225-3 [40] for wood briquettes, property class B. In the case of non-woody biomass briquettes, including WS, SFR, as well as mixtures and blends of residues with woody fractions (SM EN ISO 17225-7 [42]), the requirements are more flexible and vary according to the property class: for class A1, an ash content ≤ 3.0% is specified; for class A2, ≤6.0%; and for class B, ≤10.0%.

The results indicate that approximately 43% of the ternary domain corresponds to combinations that result in an ash content > 6%, which places these briquettes within the requirements for non-woody biomass, class A2, according to SM EN ISO 17225-7 [42]. Practically, it is sufficient for the proportion of PLCB to be at least 20%, while the proportions of the other components may vary depending on their local availability. For the production of class B briquettes, virtually any proportion of components can be used, including individual raw materials.

From an applied perspective, maintaining a high content of PLCB and limiting the additions of WS and SFR are essential conditions for ensuring that the final product complies with the quality requirements specified by ISO 17225 standards.

Based on models 5 and 6 and the trends highlighted in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the following recommendations can be made:

- For low-ash briquettes (≤3.0%), corresponding to SM EN ISO 17225-3 [40], property class B, the PLCB fraction should be ≥80%, and the SFR content should not exceed ~10%. For example, the numerically tested combination PLCB 80% + WS 10% + SFR 10% results in an ash content of around 3%. The WS proportion can be increased at the expense of SFR, depending on biomass availability.

- For A2-class briquettes according to SM EN ISO 17225-7 [42] (≤6% ash), a much wider range of mixtures can be used. For instance, a 50/25/25 combination (PLCB/WS/SFR) ensures an ash content of ≈4.1%, placing the product within this quality class.

- High proportions of WS (>50%) cause a significant increase in ash content, making it difficult to produce high-quality briquettes.

- When choosing between WS and SFR as a local additive, the model suggests that SFR in the presence of PLCB may be more favorable than WS (the PLCB × SFR interaction has a negative coefficient). However, using SFR alone generates very high ash content; therefore, moderate use of SFR (10–20%) in combination with a dominant PLCB contribution is recommended.

- The obtained models indicate that when choosing between WS and SFR as a local additive, SFR can be more effective in the presence of PLCB (negative PLCB × SFR interaction); however, using it as the sole major component leads to a very high ash content. Therefore, a moderate inclusion of SFR (10–20%) in a PLCB-dominated blend is recommended. These findings are consistent with the literature, which reports moderate calorific values (≈14.5–17 MJ·kg−1) and high ash content for WS [44,79], whereas sunflower field residues generally exhibit energy values similar to or higher than straw and lower ash levels, although they may accumulate mineral impurities [46,47,48]. Overall, both the data obtained in this study and previously reported results show that blends dominated by PLCB, complemented with moderate proportions of agricultural residues, provide the best compromise between calorific value and ash content.

- The results obtained in this study regarding the gross calorific value and ash content of the analyzed components generally fall within the ranges reported in the scientific literature. The gross calorific value determined in the present study (qV.gr = 19.38 MJ·kg−1) is slightly higher than the upper limits reported internationally. For comparison, studies conducted in Greece and Portugal indicated for peach-wood briquettes a gross calorific value of qV.gr = 18.57 MJ·kg−1 and an ash content of 3.72% [80]. Research from Poland reported qV.gr = 18.38 ± 0.72 MJ·kg−1 and ash content of 2.36% [11], while studies from Italy presented qV.gr = 17.55 ± 0.01 MJ·kg−1 and A = 4.71 ± 0.07% [10]. The ash content determined in this study (3.64%) is close to the values reported in Greece and Portugal and falls within the overall European range, thereby confirming the consistency of the energetic characteristics of the peach biomass used.

ANOVA analysis indicated that the special cubic model was not statistically significant (F = 2.28, p = 0.266; R2 adj. = 46.1%; Table A4), which limits the use of the equation for precise quantitative predictions. Nevertheless, the observed trends remain relevant for practical application and for guiding the mixture formulation process. For this reason, a margin of error of ~1 … 2% is recommended when interpreting the results.

Equation (7) and the ternary diagram (Figure 9) describe the variation in the apparent density (DE) of briquettes depending on the proportions of PLCB, WS, and SFR. From an applied perspective, the DE of briquettes represents a critical indicator for evaluating quality and energy performance, directly influencing both logistical efficiency (transport, storage, handling) and classification according to ISO 17225.

Figure 9.

Ternary diagram illustrating the variation in particle density (g·cm−3) of briquettes depending on the mass proportions of PLCB, SFR, and WS. The model was not statistically significant (F = 1.44, p = 0.4123; see Table A5), although the diagram highlights relevant density patterns in the mixtures.

Standards generally specify that high-quality briquettes should have a density ≥ 1.0 g·cm−3, a threshold associated with property classes A1 and A2 in ISO 17225-3 (wood briquettes), as well as similar classes in ISO 17225-7 (non-woody biomass and mixtures).

The results obtained show that approximately 51.6% of the ternary domain corresponds to mixture combinations that can ensure a density greater than 1.0 g·cm−3, providing producers with considerable flexibility in formulating recipes. The trends of the model and the ternary diagram indicate the following practical aspects:

- To obtain briquettes classifiable in the higher classes (A1, A2), it is recommended to use high proportions of PLCB (≥50%), which ensure densities above the 1.0 g·cm−3 threshold even in combinations with moderate additions of WS and SFR.

- Mixtures with WS > 50% or SFR > 50% frequently result in densities below the 1.0 g·cm−3 threshold, which may limit the product to property class B or even exclude it from the category of standardized solid biofuels.

- Moderate combinations of SFR (10–20%) with a dominant contribution of PLCB are preferable to high additions of WS, as the PLCB × SFR interaction positively contributes to density.

ANOVA analysis showed that the special cubic model was not statistically significant (F = 1.44, p = 0.412; R2 adj. = 22.6%; Table A5), which limits the accuracy of numerical predictions. Nevertheless, the identified trends remain valuable for practical use, and an error margin of 1–2% is recommended for implementation.

Overall, the results confirm that woody residues from PLCB play an important role in ensuring briquette quality, both by providing high energy content and by reducing ash content while increasing density. Additions of WS and sunflower hulls can be used to exploit local resources and reduce costs, but only in controlled proportions to comply with ISO 17225-3 and ISO 17225-7 standards. Only a small portion of the ternary domain (≈3.9%) allows the formulation of mixtures with ash ≤ 3%, corresponding to higher classes, while approximately half of the domain ensures the minimum required density (≥1.0 g·cm−3). Therefore, producing competitive solid biofuels requires a careful balance between components, with PLCB dominance and moderate use of WS and SFR, adapted to local resource availability.

3.4. Determination of Technological Regimes

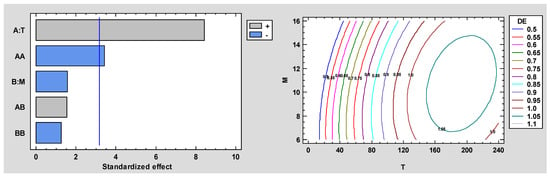

The aim of this study is to establish the effect of matrix temperature and the moisture content of the raw material on the densification capacity of PLCB briquettes. The research was conducted according to the program presented in Table 3.

Equation (8) describes the dependence of particle density (DE) on processing temperature (T) and raw material moisture content (M). A direct influence of temperature (significant positive coefficient) is observed, along with a more complex effect of moisture, where the linear term is positive, but the quadratic term (M2) has a negative effect, indicating the existence of an optimal range. The T·M interaction is present in the model but is not statistically highly significant.

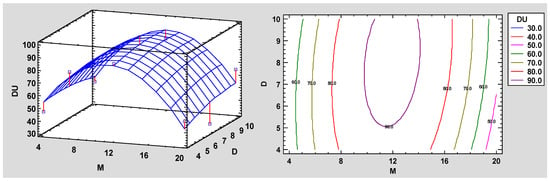

Standardized Pareto charts and response surfaces (Figure 10) clearly highlight the dominant role of temperature in increasing density, as well as the curvilinear effect of moisture. Contour surfaces show that maximum densities are achieved for high temperature values combined with an intermediate moisture level (≈9–12%).

Figure 10.

Standardized Pareto Chart and Contours of Estimated Response Surface illustrating the variation in particle density (g·cm−3) of briquettes depending on processing temperature (T, °C) and moisture content (M, %).

The ANOVA results (Table A6) confirm these observations: the factor T (temperature) is decisive (F = 71.32; p = 0.0035), having a major impact on density. The factor M (moisture) is not significant at the linear level (p = 0.2158); however, the quadratic term M2 is significant (p = 0.0415), which confirms nonlinear behavior and the existence of a technological optimum. Interaction terms are not statistically relevant (p > 0.22). R2 = 96.8% (adjusted R2 = 91.3%) confirms that the model explains the experimental variation very well.

From an applied perspective, these results indicate that a particle density above 1.0 g·cm−3, characteristic of the higher class of solid biofuels according to ISO 17225, can be achieved through strict control of processing temperature and by maintaining moisture within an optimal range. Thus, the model provides a useful tool for the technological regulation of the briquetting process, contributing to obtaining a product with increased density and adequate mechanical durability.

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that model (8) and the associated graphical representations confirm the importance of processing temperature and raw material moisture in determining briquette particle density. Increasing the temperature has a strongly favorable effect, while moisture acts in a nonlinear manner, with an optimal range of values. Practically, these findings highlight that achieving high densities, compatible with the quality class requirements of ISO 17225, depends on maintaining the temperature at an appropriate level and optimizing the biomass moisture content before processing.

The results obtained for peach biomass (particle density above 1.0 g·cm−3, optimal moisture in the range of 9–12%, and an energy potential of 33.5 ± 6.54 GJ·ha−1) show high scalability at the industrial level, since these ranges are commonly encountered under the real supply chain conditions for orchard biomass. The optimal parameters identified experimentally can be achieved using standard technologies for natural drying, shredding with 4–8 mm screens, and minimal conditioning, without requiring significant additional investments. From the perspective of solid biofuel producers, the high density and energy potential translate into increased transport and storage efficiency, reduced costs per unit of useful energy, and improved product competitiveness according to ISO 17225 criteria. Moreover, the constant availability of orchard biomass and the possibility of integrating moderate proportions of agricultural residues contribute to stabilizing raw material costs and diversifying the product portfolio, thereby strengthening the economic feasibility of large-scale production.

4. Conclusions and Future Research Direction

In the Republic of Moldova, orchards are a readily accessible sources of biomass for the production of briquettes and pellets, particularly that derived from the cultivation of fruit trees and shrubs. Efficient utilization of this potential requires concrete measures aimed at ensuring a high-quality final product. In this context, the optimal functioning of each link in the production chain plays a decisive role in guaranteeing the quality of DSBF.

In the present study, we conducted a comprehensive and applied investigation to analyze the most important factors affecting DSBF quality, specific to each stage of the production chain. The study was carried out using briquettes obtained from peach biomass and its mixtures.

The analysis of the availability and potential of orchard biomass for DSBF production revealed that there is a significant potential for plant-based orchard biomass to be used as raw material for pellet and briquette manufacturing in the Republic of Moldova. Among the species analyzed, peach was found to have the highest sustainable energy potential, at approximately 33.5 ± 6.54 GJ·ha−1.

It was also demonstrated that, during the conditioning phase of the raw material prior to densification into briquettes, it is recommended to grind the biomass using sieves with 4–8 mm openings and to maintain the moisture content within the optimal range of 6–14%.

Ternary diagrams obtained through a multifactorial study of mixtures of PLCB, WS, and SFR highlighted composition domains favorable for producing high-quality briquettes. The results confirmed that PLCB plays a decisive role in ensuring high energy input, increased density, and low ash content, while WS and SFR can be used to diversify resources and reduce costs, but only in controlled proportions. It was found that only 3.9% of the ternary domain allows the formulation of mixtures with ash content ≤ 3% (corresponding to the upper classes of SM EN ISO 17225-3 [40] and SM EN ISO 17225-7 [42]), while approximately half of the domain ensures the minimum required density (≥1.0 g·cm−3). Therefore, a careful balance among components, with a predominance of PLCB and moderate addition of WS and SFR, is essential for producing competitive solid biofuels adapted to local conditions and resources.

The study of factors influencing the energy density (DE) of PLCB briquettes showed that increasing the processing temperature has a strongly positive effect, while moisture content acts in a nonlinear manner, with an optimal value range. From a practical perspective, these findings indicate that achieving high densities compatible with the quality class requirements of ISO 17225 depends on maintaining the temperature at an adequate level and optimizing the moisture content of the biomass prior to processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M., A.B. and T.M.; methodology, A.G., B.N., L.M., N.D. and T.M.; software, T.A.I., N.D., A.G., B.N. and T.M.; validation, G.M., T.A.I., B.N., L.M., N.D. and A.P.; formal analysis, G.M., A.B., N.D. and T.M.; investigation, G.M., A.G., B.N., L.M., T.M., A.P. and N.D.; resources, G.M. and A.B.; data curation, G.M. and T.A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M., T.A.I. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, G.M., T.A.I. and T.M.; visualization, G.M., N.D., A.G., B.N., A.P. and T.M.; supervision, G.M. and A.B.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Government of the Republic of Moldova through the National Agency for Research and Development, within the framework of the projects addressing issues of critical interest, under the theme “Resilience of the Republic of Moldova to Crisis Situations”, project no. 23.70105.7007.08, contract no. 7/08R. Additional support was provided through project no. 20.80009.5107.15 “Development and implementation of good practices for sustainable agriculture and climate resilience/GREEN/020407”, which offered technical and logistical assistance.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the “Management of Scientific Research” Directorate of the Technical University of Moldova for providing logistical support in carrying out this study. Special thanks are extended to SC “BASADORO AGROTEH” SRL and “Agrisolution” SRL for their free assistance with the mechanized collection and transportation of vine residues to the analysis site, as well as to all the agricultural enterprises that permitted the collection of vineyard samples used in this study. This research was also conducted thanks to the technical support of the CZECH AID development project “Modernization and raising the prestige of Higher Agricultural Education in Moldova” [N. 25-PKVV-005] and Internal Grant Agency of the Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague [N. 20253121].

Conflicts of Interest

Author Teodor Marian was employed by the company CC “BASADORO AGROTEH” LLC. The authors declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection and preparation of samples; in the analysis or interpretation of results; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSBF | Densified solid biofuels |

| SBSC | Solid biofuels supply chain |

| PLCB | Peach lignocellulosic biomass |

| WS | Wheat straw |

| SFR | Sunflower residues |

| qV.gr | Gross calorific value at constant volume |

| A | Ash content |

| D | Particle size |

| DE | Particle density |

| DU | Mechanical durability |

| M | Moisture content |

| SLSBF | Scientific laboratory of solid biofuels |

| TEP | Theoretical energy potential |

| SEP | Sustainable energy potential |

Appendix A

Table A1.

ANOVA for Experiment—DE (Model 3, Figure 4).

Table A1.

ANOVA for Experiment—DE (Model 3, Figure 4).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A:M | 0.0294 | 1 | 0.0294 | 16.30 | 0.0273 |

| B:D | 0.0000666667 | 1 | 0.0000666667 | 0.04 | 0.8598 |

| AA | 0.0910222 | 1 | 0.0910222 | 50.46 | 0.0057 |

| AB | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.8290 |

| BB | 0.00222222 | 1 | 0.00222222 | 1.23 | 0.3480 |

| Total error | 0.00541111 | 3 | 0.0018037 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 0.128222 | 8 |

R-squared = 95.7799 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 88.7464 percent Standard Error of Est. = 0.04247 Mean absolute error = 0.0202469 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.86396 (p = 0.6123) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = 0.0435775.

Table A2.

ANOVA for Experiment—DU (Model 4, Figure 5).

Table A2.

ANOVA for Experiment—DU (Model 4, Figure 5).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A:M | 24.9288 | 1 | 24.9288 | 0.11 | 0.7664 |

| B:D | 25.5853 | 1 | 25.5853 | 0.11 | 0.7635 |

| AA | 3089.24 | 1 | 3089.24 | 13.10 | 0.0363 |

| AB | 74.2182 | 1 | 74.2182 | 0.31 | 0.6140 |

| BB | 15.9236 | 1 | 15.9236 | 0.07 | 0.8118 |

| Total error | 707.489 | 3 | 235.83 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 3937.39 | 8 |

R-squared = 82.0315 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 52.084 percent Standard Error of Est. = 15.3567 Mean absolute error = 7.75358 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.78247 (p = 0.5376) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = −0.00512898.

Table A3.

ANOVA for qV.gr (Model 5, Figure 7).

Table A3.

ANOVA for qV.gr (Model 5, Figure 7).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Cubic Model | 8.17245 | 6 | 1.36208 | 9.03 | 0.0493 |

| Total error | 0.452438 | 3 | 0.150813 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 8.62489 | 9 |

R-squared = 94.7543 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 84.2628 percent Standard Error of Est. = 0.388346 Mean absolute error = 0.16019 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.47268 (p = 0.2167) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = 0.0375944.

Table A4.

ANOVA for Ash (Model 6, Figure 8).

Table A4.

ANOVA for Ash (Model 6, Figure 8).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Cubic Model | 48.1067 | 6 | 8.01778 | 2.28 | 0.2658 |

| Total error | 10.5309 | 3 | 3.51029 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 58.6376 | 9 |

R-squared = 82.0408 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 46.1223 percent Standard Error of Est. = 1.87358 Mean absolute error = 0.850143 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.36542 (p = 0.1709) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = 0.120206.

Table A5.

ANOVA for DE (Model 7, Figure 9).

Table A5.

ANOVA for DE (Model 7, Figure 9).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Cubic Model | 0.0236233 | 6 | 0.00393722 | 1.44 | 0.4123 |

| Total error | 0.00821667 | 3 | 0.00273889 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 0.03184 | 9 |

R-squared = 74.1939 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 22.5816 percent Standard Error of Est. = 0.0523344 Mean absolute error = 0.0228095 Durbin-Watson statistic = 2.03753 (p = 0.5218) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = −0.241931.

Table A6.

Analysis of Variance for DE (Model 8, Figure 10).

Table A6.

Analysis of Variance for DE (Model 8, Figure 10).

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A:T | 0.30375 | 1 | 0.30375 | 71.32 | 0.0035 |

| B:M | 0.0104167 | 1 | 0.0104167 | 2.45 | 0.2158 |

| AA | 0.0501389 | 1 | 0.0501389 | 11.77 | 0.0415 |

| AB | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 2.35 | 0.2230 |

| BB | 0.00680556 | 1 | 0.00680556 | 1.60 | 0.2955 |

| Total error | 0.0127778 | 3 | 0.00425926 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 0.393889 | 8 |

R-squared = 96.756 percent. R-squared (adjusted for d.f.) = 91.3493 percent Standard Error of Est. = 0.065263 Mean absolute error = 0.0320988 Durbin-Watson statistic = 0.652174 (p = 0.0278) Lag 1 residual autocorrelation = 0.468599.

References

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- GRM Decision No. 102 on the Energy Strategy of the Republic of Moldova Until 2030. Available online: https://www.legis.md/cautare/getResults?doc_id=68103&lang=ro (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- GRM Energy Strategy of the Republic of Moldova Until 2050 (SEM 2050)—Concept. Available online: https://energie.gov.md/sites/default/files/concept_strategia_enenergetica_act._-clean_1.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass Energy and Biofuels: Perspective, Potentials, and Challenges in the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L. The Role of Agricultural Biomass as a Renewable Energy Source in European Union Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikovhi, A.; Motaung, T.E. Technologies and Innovations for Biomass Energy Production. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaloudas, D.; Pavlova, N.; Penchovsky, R. Lignocellulose, Algal Biomass, Biofuels and Biohydrogen: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2809–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolacu, F.; Ianuș, G.; Marian, G.; Munteanu, C.; Paleu, V.; Nazar, B.; Istrate, B.; Gudîma, A.; Daraduda, N. A Qualitative Assessment of the Specific Woody Biomass of Fruit Trees. Forests 2022, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, G.; Banari, A.; Marian, T. Sustainable Utilization of Agricultural Residues from Fruit Shrubs: Energy Potential and Physical-Chemical Properties. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2025, 16, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalaglio, G.; Fabbrizi, G.; Cardelli, F.; Lorenzi, L.; Angrisano, M.; Nicolini, A. Lignocellulosic Residues from Fruit Trees: Availability, Characterization, and Energetic Potential Valorization. Energies 2024, 17, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matłok, N.; Zaguła, G.; Gorzelany, J. Analysis of the Energy Potential of Waste Biomass Generated from Fruit Tree Seedling Production. Energies 2024, 17, 5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaño, M.; Gabaston, J.; Ortiz, V.; Cantos, E. Wood Waste from Fruit Trees: Biomolecules and Their Applications in Agri-Food Industry. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, G.; Gelu, I.; Gudîma, A.; Nazar, B.; Istrate, B.; Banari, A.; Pavlenco, A.; Daraduda, N. Calorific Value of Pellets Produced From Raw Material Collected From Both Sides of the River Prut. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 29, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, G.; De Francesco, C.; Gasperini, T.; Fabrizi, S.; Duca, D.; Ilari, A. Quality Assessment and Classification of Feedstock for Bioenergy Applications Considering ISO 17225 Standard on Solid Biofuels. Resources 2023, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.R.; Rönnqvist, M.; Ouhimmou, M.; Stuart, P. A Systematic Literature Review of the Logistics Planning for Sustainable Bioenergy Based on Forestry, Agricultural, and Municipal Solid Waste Value Chains. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, G. Biocombustibilii Solizi: Producere Şi Proprietăţi; Bons Offices: Chişinău, Moldova, 2016; ISBN 978-9975-87-166-2. [Google Scholar]

- Roudneshin, M.; Sosa, A. Optimising Agricultural Waste Supply Chains for Sustainable Bioenergy Production: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Energies 2024, 17, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgușanu, V.; Lunguleasa, A.; Spîrchez, C. The Briquettes Properties from Seed Sunflower Husk and Wood Larch Shavings. Wood Res. 2021, 66, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burli, P.; Hennig, C.; Hoefnagels, R.; Wild, M.; Majer, S.; Nguyen, Q. Assessment of Successes and Lessons Learned for Biofuels Deployment; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, G.; Ianuș, G.; Istrate, B.; Banari, A.; Nazar, B.; Munteanu, C.; Măluțan, T.; Gudîma, A.; Ciolacu, F.; Daraduda, N.; et al. Evaluation of Agricultural Residues as Organic Green Energy Source Based on Seabuckthorn, Blackberry, and Straw Blends. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarés, J.L.M.; Ortiz, L.; Granada, E.; Viar, F.P. Feasibility Study of Energy Use for Densificated Lignocellulosic Material (Briquettes). Fuel 2000, 79, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertolli, A.; Gabnai, Z.; Lengyel, P.; Bai, A. Biomass Potential and Utilization in Worldwide Research Trends—A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, M.; Gref, R.; Geladi, P.; Dahlqvist, S.A.; Lestander, T. The Influence of Raw Material Characteristics on the Industrial Pelletizing Process and Pellet Quality. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Dittrich, C.; Obi, O.F.; Pecenka, R. Effects of Feeding Speed and Temperature on Properties of Briquettes from Poplar Wood Using a Hydraulic Briquetting Press. Resources 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpinen, O.J.; Aalto, M.; KC, R.; Tokola, T.; Ranta, T. Utilisation of Spatial Data in Energy Biomass Supply Chain Research—A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Roque, Y.; Orantes-Flores, H.J.; López-De-Paz, P.; Pérez-Luna, Y.C.; Canseco-Pérez, M.A.; Zenteno-Carballo, A.G. Biomass Briquettes: Raw Material, Technologies and Densification Parameters, Quality and Future Challenges. Sci. Agropecu. 2025, 16, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bača, P.; Mašán, V.; Vanýsek, P.; Burg, P.; Binar, T.; Suchý, P.; Vaňková, L. Evaluation of the Thermal Energy Potential of Waste Products from Fruit Preparation and Processing Industry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurek, T.; Gendek, A.; Roman, K.; Dąbrowska, M. The Effect of Temperature and Moisture on the Chosen Parameters of Briquettes Made of Shredded Logging Residues. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 130, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Cepeda, C.O.; Goche-Télles, J.R.; Palacios-Mendoza, C.; Moreno-Anguiano, O.; Núñez-Retana, V.D.; Heya, M.N.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Effect of Sawdust Particle Size on Physical, Mechanical, and Energetic Properties of Pinus Durangensis Briquettes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.Y.; Afzal, M.T. Effect of Particle Size on Mechanical Properties of Pellets Made from Biomass Blends. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Desamsetty, T.M.; Rahmanian, N. Unlocking Power: Impact of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Biomass Wood Pellets on Energy Release and Carbon Emissions in Power Sector. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 16, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Tabil, L.G.; Sokhansanj, S. Effects of Compressive Force, Particle Size and Moisture Content on Mechanical Properties of Biomass Pellets from Grasses. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, O.F.; Pecenka, R.; Clifford, M.J. A Review of Biomass Briquette Binders and Quality Parameters. Energies 2022, 15, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]