1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Globally, the frequency and intensity of heat waves are increasing, owing to global warming and climate change. Moreover, average temperatures also show a gradual upward trend [

1,

2,

3]. In South Korea, the number of heat wave days and their intensities have increased since the 1980s, accompanied by long-term rising trends in climate patterns [

4]. Heat waves directly affect crop growth, leading to reduced yields, degraded quality, and supply instability, which can pose a serious threat to food security and extend beyond agricultural losses [

5,

6,

7]. In particular, long-term climate crises have exacerbated seasonal supply imbalances and price volatility, underscoring the need for strategic responses to maintain a stable food production system [

8,

9]. Against this backdrop, the importance of controlled environmental horticulture, which can better adapt to external environmental changes than open-field cultivation, has been highlighted. Moreover, it has become a key alternative to ensure stable crop productivity and quality [

10,

11].

However, with the continued increase in the frequency and intensity of heat waves, existing controlled-environment greenhouses are not entirely free from high-temperature stress during the summer months [

12,

13,

14]. Particularly during summer, the frequency of air-conditioning system operation increases sharply, causing cooling loads to increase rapidly. Some studies have reported that cooling loads in summer are several times higher than heating loads in winter [

15,

16].

In South Korea, Venlo-type multi-span greenhouses have been widely adopted, particularly for year-round production of high-value fruit vegetables such as paprika and tomatoes, and are used as representative structures in large commercial complexes and experimental facilities. These greenhouses are equipped with continuous ventilation windows on their roofs, which facilitate heat dissipation through natural ventilation, and are known for their relatively good insulation performance and cooling effectiveness under summer conditions [

17,

18,

19].

Recently, owing to the increased frequency and intensity of high temperatures caused by climate change, the need to explore diverse structural approaches beyond existing designs has been growing [

20,

21]. Accordingly, the Rural Development Administration (RDA) of South Korea is currently developing a high-height wide-type greenhouse that is structurally different from the Venlo-type greenhouse, aiming to achieve stable crop growth under high temperatures and reduced cooling energy consumption.

The structure of the high-height wide-type greenhouse has higher sidewalls than conventional greenhouses, maximizing the temperature and pressure differences between the interior and exterior of the greenhouse, enhancing buoyancy-driven natural ventilation. Moreover, the wide-type structure helps maintain uniform airflow inside the greenhouse, reduces spatial variations in temperature and humidity distribution, and contributes to improved homogeneity in the crop growth environment. These structural characteristics improve the natural ventilation performance and reduce the dependency on cooling systems, providing potential advantages in terms of heat wave response and energy-efficient operation.

However, greenhouses are still in the early development stages, making empirical validation difficult. Structural improvements in greenhouses carry high failure costs and are challenging to recover after installation, making pre-construction performance evaluations crucial. Most previous CFD studies have therefore examined conventional greenhouses with lower heights and narrower spans, which differ from the high-height wide-type greenhouse recently developed by the Rural Development Administration (RDA) and not yet widely adopted in private farms. As a result, the thermal and ventilation performance of this RDA high-height wide-type greenhouse under heat-wave conditions remains insufficiently documented. This pre-evaluation can predict and quantify the structural characteristics and thermal environmental responses through computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, which can help derive an optimal design before empirical testing. CFD is a tool that precisely simulates various environmental and structural conditions to analyze fluid and thermal behaviors and has recently become a key tool for feasibility studies and performance predictions in agricultural facility design [

22,

23,

24].

Thus, to improve greenhouse structures to cope with high temperatures, CFD-based preconstruction performance evaluation can serve as a critical strategy for increasing decision-making precision during the early stages of structural design and enhancing structural integrity before the empirical testing phase. In this context, this study aims to preemptively analyze the thermal environmental performance of a high-height wide-type greenhouse under development by the RDA to assess its effectiveness in high-temperature response.

1.2. Literature Review

In designing complex environmental systems, such as controlled-environment horticulture, pre-assessment of structural feasibility and thermal environmental performance is recognized as a necessary process to be conducted before empirical experiments. Particularly, in the case of greenhouse structural improvements, physical experiments alone pose significant temporal and economic constraints, leading to the increasing use of simulation-based prediction techniques from the early stages of design. Among these, CFD is a representative method that can quantitatively analyze the internal flow fields and thermal distribution characteristics owing to changes in structural shapes. It is actively used as a pre-performance prediction tool for various structural design scenarios. CFD-based analysis is gaining attention because of its ability to secure design feasibility before the installation of a structure and provide scientific evidence for structural decision-making processes.

Akrami et al. [

25] simulated various ventilation scenarios with different vent configurations and layouts in a greenhouse using CFD and quantitatively analyzed the differences in the internal temperature and flow distribution, allowing them to evaluate the impact of structural adjustments on the ventilation efficiency and thermal environment in advance. Similarly, Pierart et al. [

26] implemented various greenhouse entrance and ventilation conditions using CFD to analyze temperature and humidity changes and growth suitability across different scenarios. Their results demonstrated that these outcomes could be utilized to derive the structural criteria and input variables to be considered in the control system design. Furthermore, Ghibeche et al. [

27] compared and analyzed different structural design scenarios for closed-type greenhouses using CFD and preemptively derived structural differences in the high-temperature response efficiency based on internal heat flow characteristics and cooling load variations. These studies demonstrate that CFD is an effective tool for providing direction in greenhouse structural design and enabling quantitative comparisons during the pre-empirical stage.

Moreover, previous studies have validated the precision and reliability of CFD-based design predictions by comparing simulation results with actual measurements from greenhouse environments. Kibwika et al. [

28] developed a CFD model to design a large-scale Venlo-type greenhouse complex and analyzed the ventilation performance under various structural conditions. Their results exhibited a high correlation with the actual measurement data (R

2 = 0.968), confirming the validity of CFD as a pre-prediction tool. Similarly, Li et al. [

29] simulated the ventilation strategy of an arch-type greenhouse using CFD and found that the average error with actual temperatures was within 0.7 °C, providing practical design improvement directions. Wei et al. [

30] pre-evaluated ventilation structures in hot and humid regions using CFD and validated the prediction reliability of CFD by confirming the error with actual measurements to be within 0.11 °C.

Thus, CFD is a reliable means of assessing the feasibility of greenhouse structures and environmental control systems without physical experimentation and allows for the quantitative comparison of various design options. This pre-assessment-based structural design approach has emerged as a strategic method capable of ensuring technical precision and economic efficiency, particularly in the context of the increasing frequency and intensity of heat waves due to climate change.

Nevertheless, several research gaps remain in the application of CFD to greenhouse design under emerging climatic and structural conditions. Most previous studies have focused on conventional greenhouse configurations with relatively low ridge and sidewall heights and moderate spans and have mainly considered typical summer conditions rather than extreme heat-wave scenarios in which outdoor temperatures exceed 35–40 °C. In addition, there is limited CFD-based research on newly developed large-space greenhouse concepts, such as high-height wide-type structures that create substantially larger enclosed air volumes and distinct vertical stratification of the thermal environment. Furthermore, many existing studies have examined either natural ventilation or a single cooling technique (e.g., fogging or pad-and-fan) in isolation, whereas systematic comparisons of combined or hybrid cooling strategies in such large-space greenhouses are still scarce. These gaps highlight the need for CFD-based pre-evaluation of high-height wide-type greenhouses specifically designed for heat-wave resilience and for comparative analysis of multiple cooling scenarios, which is the focus of the present study.

1.3. Research Scope and Goals

This study aims to preemptively evaluate the thermal environmental performance of a high-height wide-type greenhouse, which is currently being developed by the Rural Development Administration (RDA) as part of a structural improvement to address high-temperature problems during summer. To this end, CFD simulations were conducted for the high-height wide-type and conventional Venlo-type greenhouses under various cooling operation conditions, including natural ventilation, fogging systems, fan coil unit (FCU) systems, and hybrid systems, and the resulting thermal environmental responses were quantitatively compared and analyzed.

The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- (1)

To quantitatively compare the differences in ventilation performance and air and root-zone temperature distributions between the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses under natural ventilation conditions.

- (2)

To evaluate the effectiveness of different active cooling systems (fogging and FCU) in reducing internal and root-zone temperatures and improving thermal uniformity under extreme summer conditions.

- (3)

To assess the performance of a hybrid cooling configuration combining fogging and FCU operation and to identify thermally effective operating conditions for mitigating heat stress in both greenhouse types.

- (4)

To provide quantitative design-stage information that supports the evaluation of structural applicability and operational feasibility of high-height wide-type greenhouses for high-temperature response, thereby offering foundational data for future empirical experiments and on-site applications.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed CFD simulations, conducted in 2023–2025, to perform a preliminary evaluation of the thermal performance of a high-height wide-type greenhouse under high-temperature conditions. Focus was placed on the effects of different ventilation and cooling strategies. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, detailed 3D models of the high-height wide-type and widely adopted Venlo-type greenhouses were constructed based on actual structural specifications. The two greenhouse types were compared under identical simulation conditions to assess the thermal environment and cooling performance differences attributable to the structural design.

Internationally validated CFD modeling techniques and numerical methods were employed. The mesh configuration was determined based on resolution criteria reported in previously validated greenhouse CFD studies. Subsequently, the mesh was further refined in critical thermal regions, such as FCUs, fogging zones, and crop canopy areas, to ensure sufficient accuracy in key flow paths. The boundary conditions, solver settings, and turbulence models were selected following established modeling practices to enhance reliability and reproducibility. Various operational and environmental scenarios were simulated, including external temperatures, roof-vent opening ratios, as well as the use of fogging, FCU, and hybrid cooling systems. An overview of the simulation workflow is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Target Facility

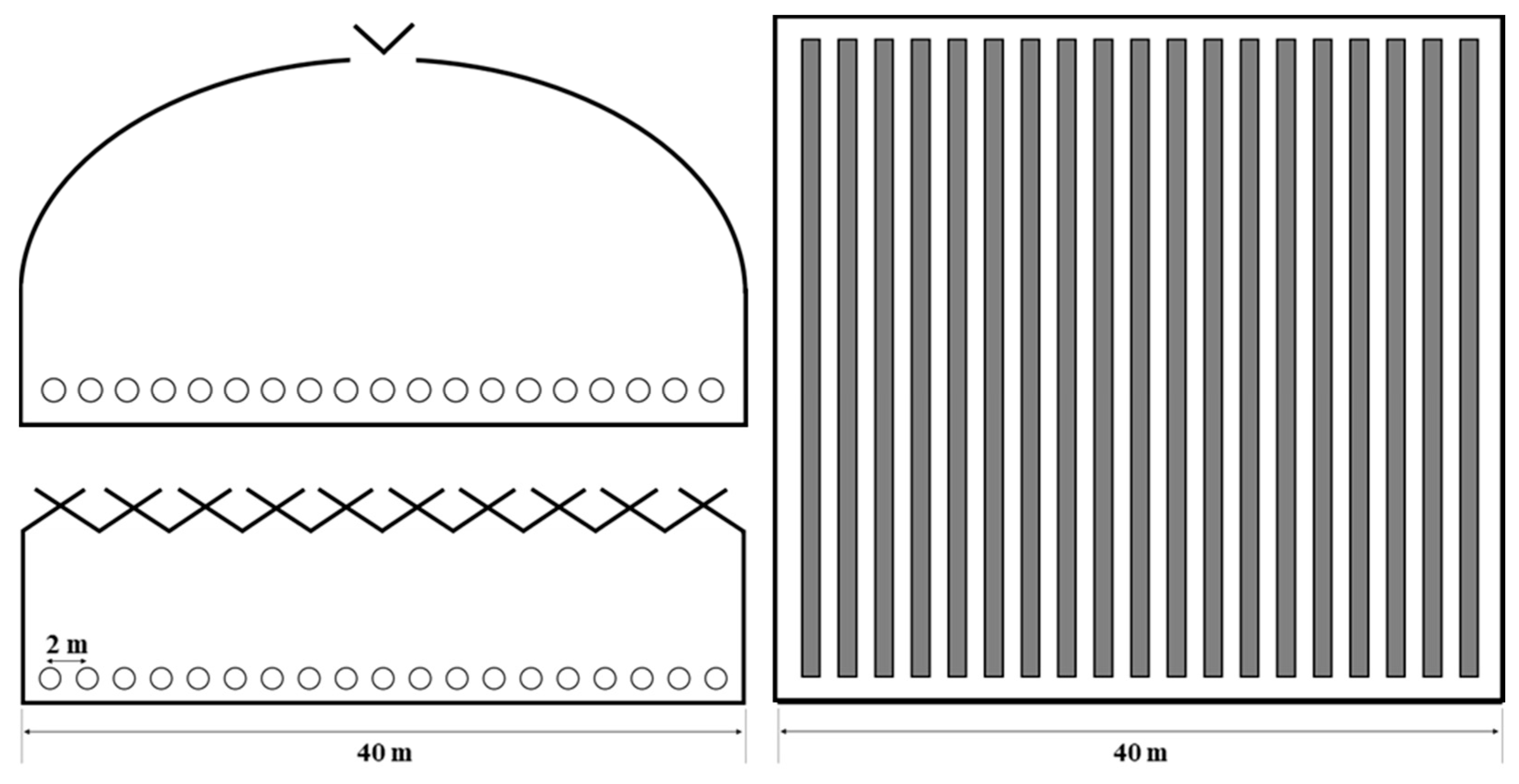

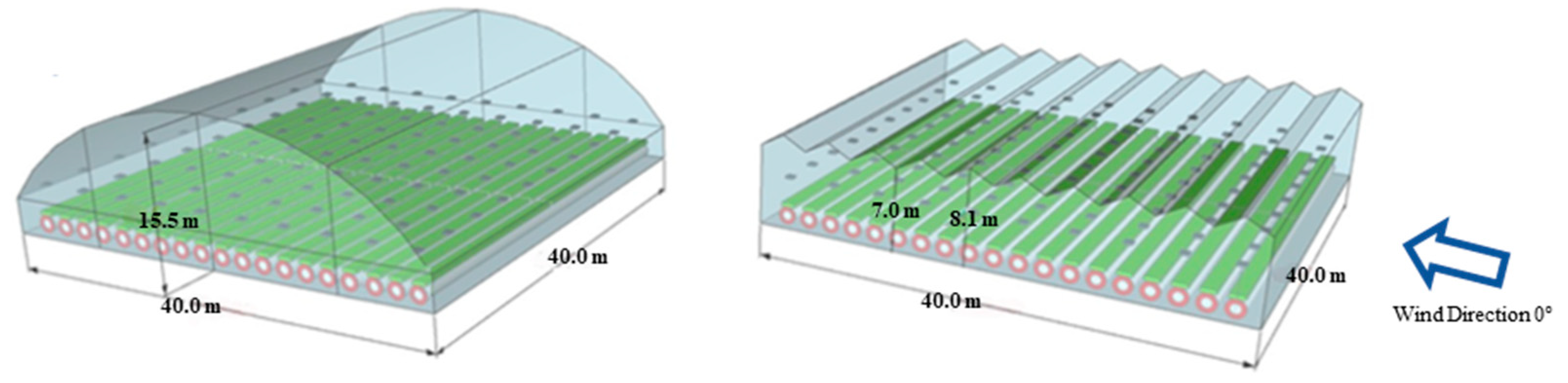

The structural configurations and dimensions of the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses are shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 1. The high-height wide-type greenhouse exhibits an overall ridge height of 15.5 m, a sidewall height of 3.8 m, a width of 52 m, and a length of 84 m. It is designed with an elevated sidewall height compared with conventional greenhouses to enhance buoyancy-driven ventilation, reduce temperature accumulation above the crop canopy, and improve temperature uniformity for stable crop production under high-temperature conditions.

A high-height wide-type greenhouse has multiple climate control systems, including a fog cooling system, shading curtains, and FCUs to maintain the internal temperature and humidity. Side and roof vents are installed to facilitate natural ventilation and increase the inflow of outdoor air. The side vents are positioned at a height of 1.8 m above ground level, with individual vent heights of 1.2 m arranged continuously along the greenhouse sidewalls. The roof vents are symmetrically configured on both sides of the central ridge and opened to a width of 0.85 m each. These vents can be operated manually or automatically, and additional large exhaust fans are installed below the roof vents to remove the heat accumulated in the upper zone of the greenhouse owing to its high-roof structure.

In contrast, the Venlo-type greenhouse is a single-span structure with a ridge height of 8.1 m, a sidewall height of 7.0 m, a width of 8.0 m, and a length of 40.0 m. Originating in Europe—particularly the Netherlands—this type of greenhouse is characterized by its sawtooth-shaped roof design, rather than an arched form, enabling continuous roof vents. The high sidewalls and multiple ventilation openings distributed along the roof facilitate the effective discharge of accumulated heat from the upper zone, enhancing the natural ventilation performance.

Because of these structural features, Venlo-type greenhouses offer excellent thermal buffering capacities and are suitable for crop cultivation under high-temperature conditions. Various climate control systems are applied for internal temperature regulation. Similarly to the high-height wide-type greenhouse, the Venlo-type structure is equipped with a fog cooling system and an FCU system, and is designed to enable hybrid cooling operation by integrating roof and side vents for natural ventilation.

2.2. Thermal Environment Modeling of Greenhouses Using Cfd

2.2.1. Design of Geometries for CFD Simulation

To conduct a preliminary evaluation of the thermal environment of the high-height wide-type greenhouse under high-temperature conditions, the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses were modeled in three dimensions with identical floor areas of 40 m × 40 m (1600 m2). The ridge and sidewall heights of each greenhouse were kept consistent with their actual structural specifications, whereas only the floor area was standardized. This common floor area was selected to enable a direct comparison of the internal flow and thermal fields between the two structures under identical external loading, without the confounding effect of different plan areas. Although the overall floor area and aspect ratio can influence buoyancy-driven ventilation, a square domain of approximately 1600 m2 falls within the typical size range of commercial greenhouses, and previous CFD studies have reported that, within this range, the qualitative flow and temperature patterns are more strongly governed by structural configuration and opening conditions than by moderate changes in floor area. At the same time, the differences in ridge and sidewall heights, and consequently in enclosed air volume, were intentionally preserved to represent the actual structural concepts of the two greenhouse types. The larger air volume of the high-height wide-type greenhouse can moderate the rate of indoor temperature rise and enhance buoyancy-driven airflow, and is therefore regarded as an intrinsic component of the structural performance being evaluated in this comparative study. Thus, the present modeling setup is considered appropriate to represent realistic installation conditions while highlighting the relative performance differences between the two greenhouse types. Nevertheless, this configuration also represents an idealized footprint compared with many commercial multi-span greenhouse layouts, and the results should therefore be interpreted as describing relative differences in ventilation and thermal behavior under a representative plan area rather than reproducing any specific existing facility. Three configurations were created for the Venlo-type greenhouse based on the roof vent opening ratios of 100%, 50%, and 10%.

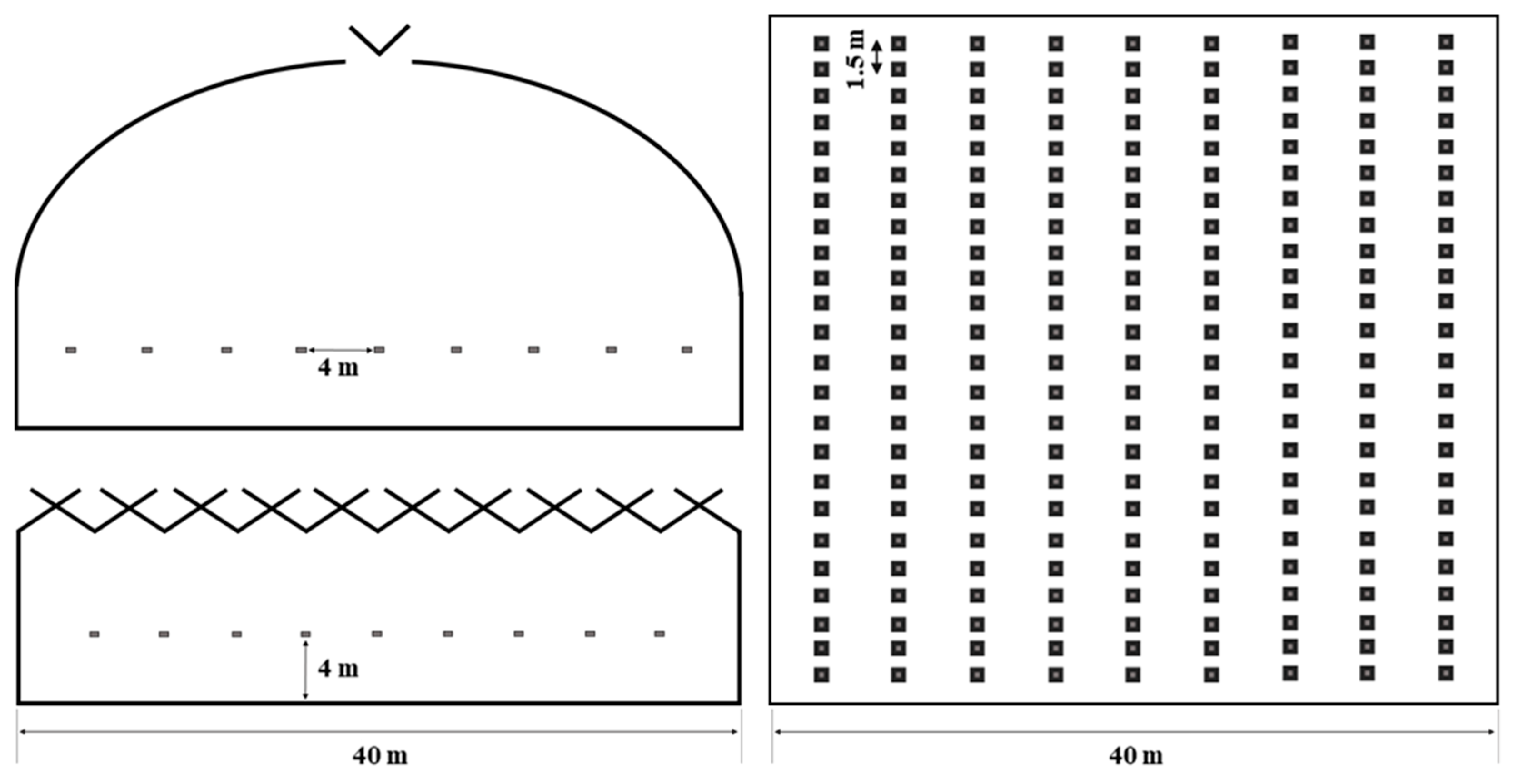

To quantitatively compare the cooling performance, both greenhouse models were equipped with an equal number and distribution of fogging and FCU systems based on real-world installation cases and relevant design standards [

31]. As shown in

Figure 3, 19 FCUs were arranged along the greenhouse width at 2 m intervals. The fogging system, illustrated in

Figure 4, was configured with one pipe every 4 m along the width and nozzles spaced at 1.5 m intervals. These settings were derived from practical installation guidelines and prior literature, and were applied equally to both greenhouses to ensure fair simulation conditions.

In CFD simulations, crop canopies consist of complex geometries, including stems, leaves, and branches, significantly influencing airflow and heat transfer. Therefore, modeling an entire crop canopy with detailed geometric fidelity is computationally inefficient. To address this, the tomato plants in this study were simplified as rectangular blocks with a width of 0.6 m and a height of 2.0 m. These dimensions were selected to represent a typical single-row canopy width and trained plant height used in commercial greenhouse tomato cultivation during the summer season, where within-row spacings of approximately 0.4–0.6 m and plant heights of about 1.8–2.5 m under trellis systems are commonly adopted. Thus, the modeled plant size and arrangement density fall within a representative range of practical cultivation patterns. The aerodynamic resistance and heat exchange associated with transpiration were incorporated using a porous media model based on the parameters derived from previous studies [

32,

33,

34].

The porous media model integrates crop porosity, flow resistance coefficients, and latent heat release due to transpiration, allowing the crop zone to be treated as a medium that impedes airflow, while enabling simultaneous heat and mass transfer [

35]. This modeling approach enables the quantitative representation of physical interactions between crops and airflow, and has been widely validated and adopted in previous CFD studies of greenhouse environments. Moreover, it enables the accurate reproduction of key thermal and fluid dynamic characteristics without explicitly resolving individual plant structures [

36].

2.2.2. Mesh Generation and Quality Evaluation

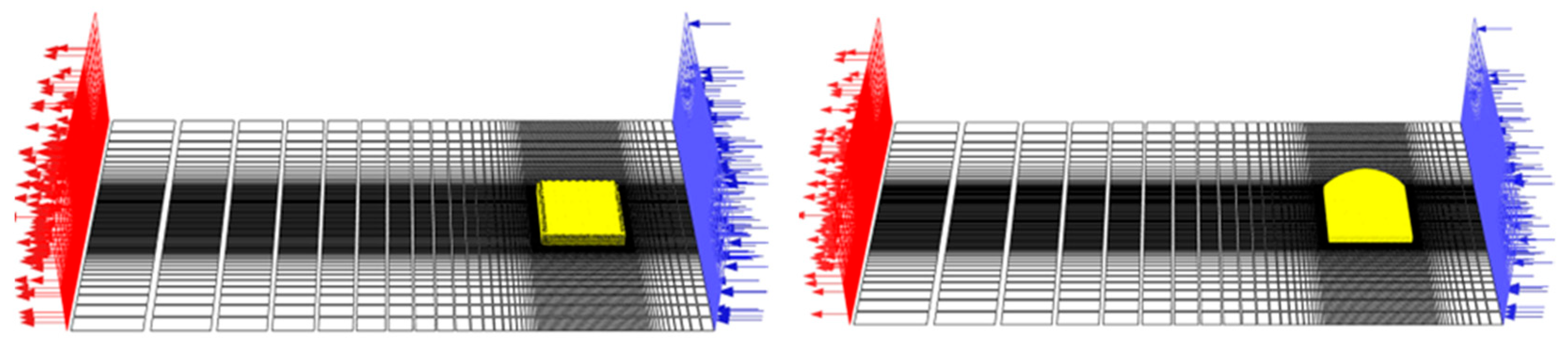

As shown in

Figure 5, the structured computational meshes were developed for both greenhouse types. The external computational domain was defined based on previous studies that analyzed wind loads on greenhouse structures [

37,

38]. For the internal region, local mesh refinement was applied near the crop canopy, fogging lines, and FCUs, where thermal and airflow interactions were the most critical.

The final mesh comprised approximately 6.5 million cells. The mesh quality evaluation yielded an orthogonal quality of 0.91 and a skewness of 0.12, which are well within the generally accepted ranges for CFD simulations (skewness < 0.5, orthogonal quality > 0.7), ensuring reliable and stable numerical performance.

The mesh resolution strategy, including the base density and refinement zones, was designed with reference to validated greenhouse CFD studies Akrami et al. [

25] and Pierart et al. [

26], which reported cell counts in the range of 4–7 million to be sufficient for thermal accuracy and convergence. The proposed model is configured according to this benchmark to ensure numerical reliability. Each simulation case required approximately 100 min of computational time, and multiple operating conditions were evaluated. Therefore, a full formal mesh-independence study with several additional mesh levels was not carried out within the scope of this work.

2.2.3. Boundary Conditions and Input Parameters

The boundary conditions, material properties, and numerical settings must be defined in CFD simulations to ensure model accuracy. The boundary conditions used in this study are listed in

Table 2. To simulate the internal temperature of the greenhouse under high-temperature conditions, heat flux was applied as a boundary condition to the exterior ground surface and the greenhouse floor using the external air temperature as a reference [

38].

Three external air temperature scenarios were considered (35, 40, and 45 °C), and corresponding uniform heat fluxes of 270, 290, and 310 W·m−2, respectively, were imposed on both the exterior ground and the greenhouse floor. These heat-flux values were determined empirically so that the quasi steady-state indoor air temperature of the reference greenhouse matched the target external temperature scenarios (35, 40, and 45 °C) while remaining within a realistic range for summer greenhouse conditions, rather than being derived from a detailed radiation model. The same heat-flux–temperature combinations were consistently applied to all simulations for each external temperature scenario.

External air temperatures were set to 35, 40, and 45 °C to represent extreme summer conditions typical in South Korea. A reference wind speed of 2.0 m·s

−1 was imposed at the inlet to represent a moderate breeze condition frequently observed during summer afternoons in Korean greenhouse-producing regions and to be consistent with representative design wind speeds adopted in previous greenhouse ventilation studies. As shown in

Figure 6, a wind direction of 0° (perpendicular to the greenhouse sidewalls), which is known to strongly affect wind-driven natural ventilation in multi-span greenhouses, was used as the prevailing wind condition. Under this boundary condition, the predicted ventilation rates and temperature distributions should be interpreted as corresponding to a representative moderate-wind case, providing a consistent basis for comparing the two greenhouse types.

Sensible and latent heat transfer models for tomato crops were defined with reference to previous studies on evapotranspiration in warm, humid climates and CFD analyses of controlled-environment plant production systems [

39]. For porous media modeling, sensible and latent heat terms were applied as internal volumetric heat sources, whereas the airflow resistance within the crop canopy was represented by viscous and inertial resistance coefficients. Based on aerodynamic drag data reported for greenhouse crops in the literature, the viscous and inertial resistance coefficients were set to 2.53 m

−2 and 1.60 m

−1, respectively. The latent heat release due to transpiration was defined as −41.80 W·m

−3, chosen so that the resulting evapotranspiration rate falls within the range reported for summer greenhouse conditions in warm, humid regions.

For the fogging system, the spray rates were determined by converting the recommended values per unit area from the RDA to match the area of the high-height wide-type greenhouse. Therefore, the selected spray rates were 27 and 35 L·min

−1, and the corresponding latent heat of water evaporation was calculated and applied as a source term in the simulation [

40]. In the CFD model, the fogging system was represented as a distributed latent-heat cooling source rather than by explicitly tracking individual droplets. The spray was assumed to be generated by high-pressure nozzles producing fine droplets with a characteristic diameter on the order of several tens of micrometers, and, under the high-temperature and relatively low humidity summer conditions considered in this study, the water was assumed to evaporate completely within the greenhouse air volume. Accordingly, an evaporation efficiency of 100% was applied so that the entire water mass flow rate contributed to the latent-heat sink term, and droplet inertia and liquid water films on surfaces were neglected. This idealized representation focuses on the bulk cooling effect of fogging and was applied consistently to all greenhouse types and operating scenarios.

The airflow rate for the FCU system was set to 200 m

3·min

−1 based on previous studies, and the discharge temperature was defined as 20 °C according to RDA guidelines and an additional 15 °C to reflect more extreme thermal conditions [

41].

2.2.4. Definition of CFD Simulation Case

The CFD simulation cases designed to evaluate the applicability of the high-height wide-type greenhouse under high-temperature conditions are summarized in

Figure 7 and

Table 3. A total of 78 simulation cases were categorized into natural and forced ventilation conditions. For natural ventilation, six cases considered only the external wind effects, whereas 24 cases involved fogging system operations. Under forced ventilation, 24 cases applied the FCU system alone, and 24 additional cases employed a hybrid cooling strategy combining fogging and FCU systems.

The average internal air temperature and crop canopy temperature were analyzed to compare the thermal characteristics of the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses using CFD simulations. As shown in

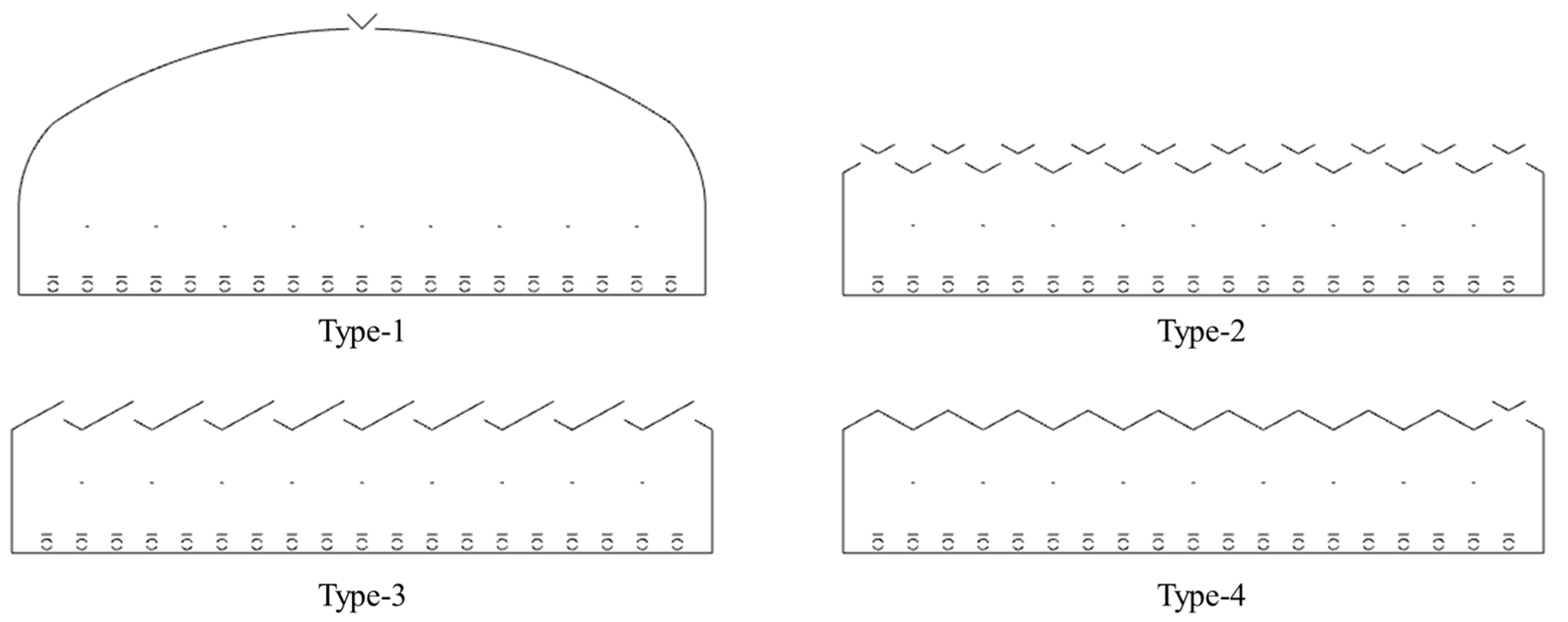

Figure 8, the high-height wide-type greenhouse was defined as Type-1, whereas the Venlo-type greenhouse was classified into three configurations, Type-2, Type-3, and Type-4, based on the roof vent opening ratios of 100%, 50%, and 10%, respectively, to evaluate the thermal environment under different ventilation strategies.

To account for the geometric symmetry of the greenhouse, a virtual vertical cross-sectional plane was defined along the center of the greenhouse width. This plane represents a vertical slice through the midline of the structure, capturing the representative internal airflow and thermal behavior. All subsequent analyses of the temperature and flow distributions were based on this reference section.

2.2.5. CFD Numerical Method and Solver Settings

In this study, three-dimensional CFD simulations were conducted using the commercial software ANSYS Fluent (ver. 21.0, ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA) to evaluate the thermal environment and ventilation performance of a greenhouse with high-temperature resistance. A pressure-based solver within the finite volume method (FVM) framework was employed, and the flow was assumed incompressible throughout the domain. The simulations were conducted under steady-state conditions using the realizable k-ε turbulence model. This turbulence model is well-suited for complex internal flow fields, such as those found in greenhouse environments, owing to its improved prediction of turbulent viscosity and shear stress behavior [

42]. A gravitational acceleration of 9.81 m·s

−2 was applied uniformly across the computational domain.

The thermophysical properties of air were defined by assuming ideal gas behavior, with a constant dynamic viscosity of 1.7894 × 10

−5 kg·m

−1·s

−1. The governing equations of mass, momentum, and energy conservation were discretized in a conservative form according to the FVM. Assuming incompressible flow, the continuity equation is formulated as shown in Equation (1).

The momentum equation was applied in the conservative form given by Equation (2).

In addition, when considering energy transfer, a thermal flow analysis is performed based on the energy equation described in Equation (3).

Here, ui represents the velocity components (m·s−1), ρ denotes the density (kg·m−3), p denotes the pressure (Pa), τij denotes the viscous stress tensor (Pa), e0 denotes the total energy per unit mass (J·kg−1), qj denotes the heat flux (W·m−2), xi and xj are the spatial coordinates (m), and t denotes time (s). The indices i and j follow the Einstein notation, implying a summation over the repeated indices.

The coupling between pressure and velocity was resolved using the semi-implicit method for pressure-linked equations (SIMPLE) algorithm. Spatial discretization was performed using a second-order upwind scheme, whereas pressure interpolation was conducted using the pressure-staggering option (PRESTO!) scheme. All governing equations were iteratively solved until the residuals were below 10−5, ensuring numerical stability and convergence.

2.3. Estimation of Greenhouse Ventilation Rate

First, the ventilation rates of the high-height, wide, and Venlo-type greenhouses must be analyzed to evaluate the thermal environment under natural ventilation conditions. Representative methods for quantitatively estimating the amount of internal air replacement under various ventilation conditions include the mass flow rate (MFR) method and tracer gas decay (TGD) methods. In this study, Equations (4) and (5) were applied for the analysis [

43]. In Equation (4), AER

MFR represents air exchange by mass flow rate (AER min

−1), whereas AER

TGD in Equation (5) represents air exchange by tracer gas decay. Furthermore, V is the volume of the greenhouse (m

3), v

i and v

o are the inlet and outlet air velocities (m·s

−1), respectively, A

i and A

o are the inlet and outlet ventilation areas (m

2), respectively, and C

o and C

t are the tracer gas concentrations (ppm) over time.

The MFR method evaluates the average ventilation rate of the entire greenhouse space, allowing the calculation of the number of air exchanges per unit time, regardless of the spatial position. In contrast, the TGD method enables the localized measurement of actual ventilation rates, offering higher accuracy for specific regions [

44]. In this study, to conduct a natural ventilation analysis based on the CFD model, the MFR method was adopted for its suitability in comparing the overall ventilation characteristics between the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses Under Natural Ventilation

3.1.1. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses According to Roof Vent Opening Ratios

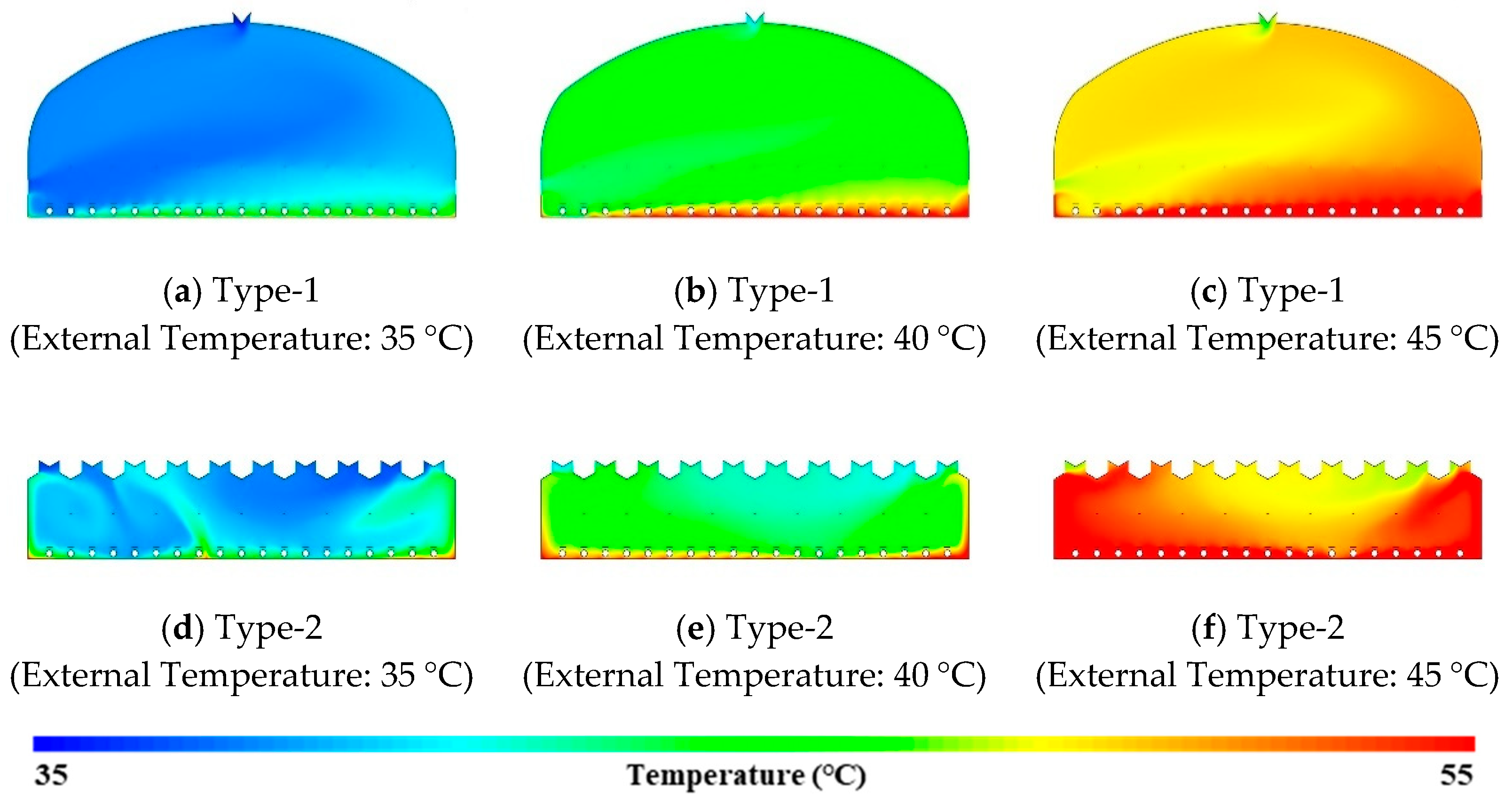

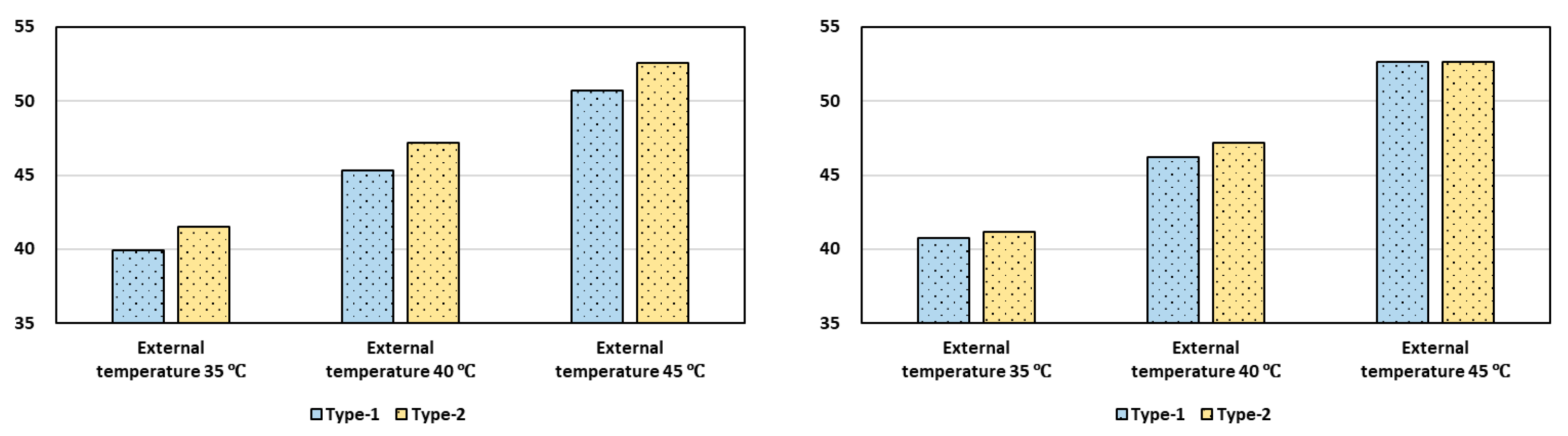

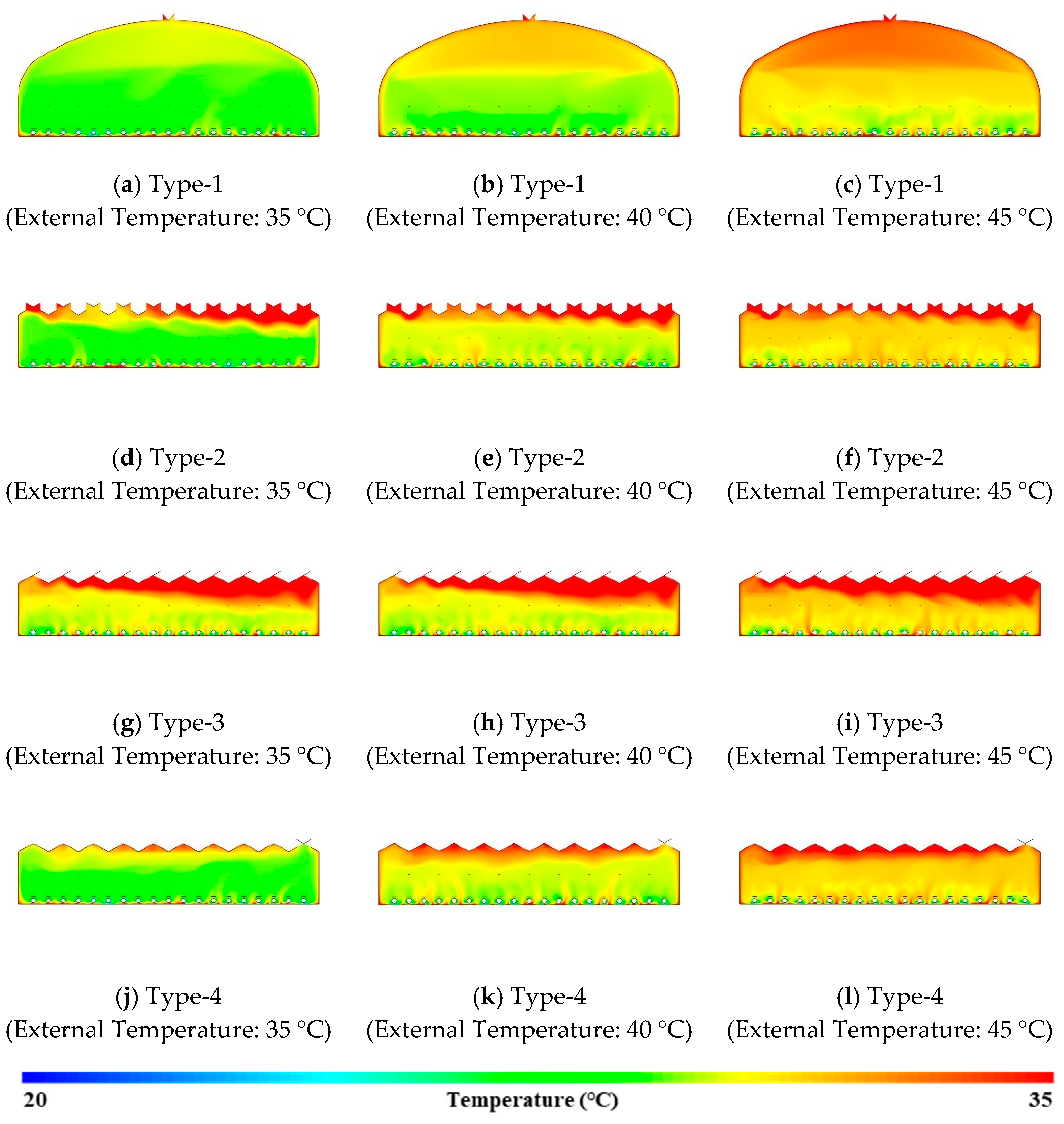

The thermal environmental characteristics of the high-height wide-type greenhouse (Type-1) and Venlo-type greenhouse (Type-2) under natural ventilation conditions were analyzed using CFD, and the results are presented in

Figure 9,

Figure 10, and

Table 4. Only the condition of fully open ventilation windows for Type-2 was considered in this analysis.

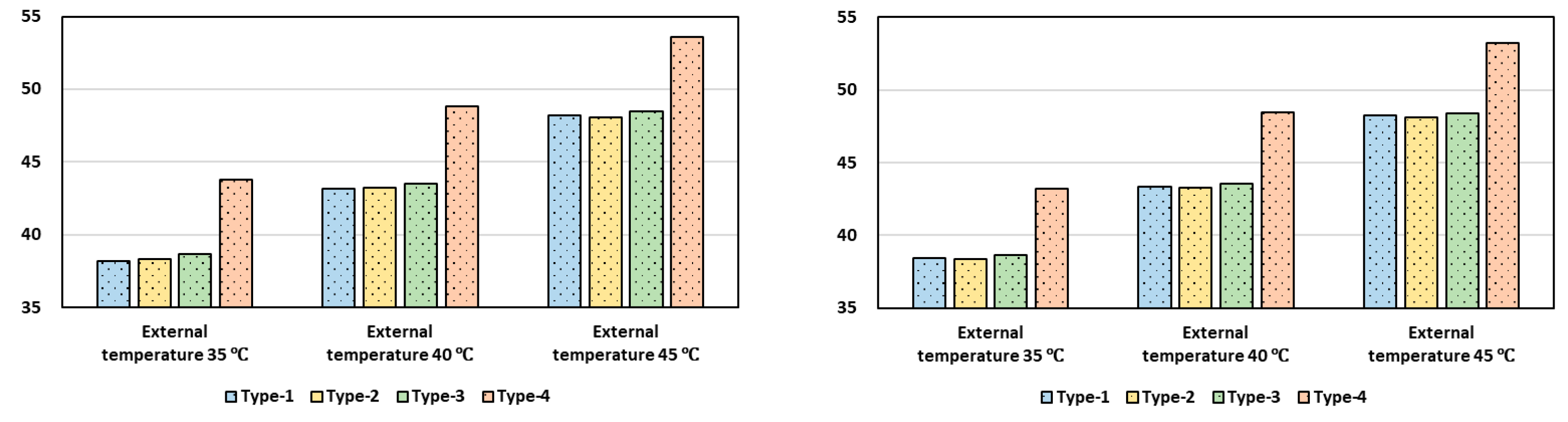

The simulation results indicated that the calculated ventilation rate was 0.45 cycles per min for Type-1 and 0.30 cycles per min for Type-2, confirming that the high-height wide type structure had a relatively better natural ventilation performance. As the outdoor temperature increased by 5 °C, the average internal temperature in both greenhouses remained approximately 5 °C higher than the outdoor temperature, with Type-1 showing an average temperature of 1.5 °C lower than that of Type-2.

To further interpret the difference in ventilation rate, the key structural features affecting natural ventilation were examined. Compared with Type-2, Type-1 has a higher ridge and a larger vertical distance between the side openings and the roof exhaust opening, which enhances the buoyancy-driven pressure difference along the main ventilation path. Type-1 also uses a continuous ridge vent located near the highest point of the roof, whereas Type-2 has multiple vents along a lower roof profile, creating a more fragmented exhaust area. As illustrated by the streamline patterns in

Figure 9, these geometric features in Type-1 reduce flow resistance and promote a coherent upward plume that more effectively removes warm air from the crop zone, explaining the higher air-exchange rate of 0.45 min

−1 compared with 0.30 min

−1 for Type-2 under the same external wind conditions.

For the average root zone temperature, Type-1 tended to be approximately 1–2 °C higher than the internal average temperature, which can be attributed to the direct influx of hot outdoor air through side windows, causing the lower part of the plants to be more affected by the outdoor temperature. In contrast, Type-2, with its relatively lower ventilation rate and limited outdoor air infiltration, resulted in a root zone temperature similar to or even lower than the internal average temperature. This was likely due to the latent heat effect of plant transpiration.

However, in both greenhouse types, the internal temperature exceeded the optimal growth temperature range for tomatoes (17–27 °C) regardless of changes in outdoor temperature, confirming that natural ventilation alone is insufficient to maintain a suitable thermal environment for crop growth under high-temperature summer conditions.

Nevertheless, the high-height wide-type greenhouse demonstrated higher ventilation rates and lower average internal temperatures than the Venlo-type greenhouse, indicating its structural advantage in responding to high-temperature environments. This is attributed to the strong buoyancy-driven ventilation effect formed by the high-height structure and the uniform temperature distribution between the top and bottom of the greenhouse.

These results can serve as fundamental data to quantitatively validate the structural characteristics and natural ventilation performance of high-height, wide-type greenhouses. Under the highest external temperature scenario, the simulated indoor air temperature locally reached approximately 40–52 °C, which is far above the upper temperature limit for safe tomato production. At such extreme temperatures, tomato plants are expected to experience severe heat stress, including strong reductions in photosynthetic activity, impaired pollen viability and fruit set, and a high risk of irreversible tissue damage. From an operational point of view, these extreme conditions also increase heat-stress risk for workers and substantially constrain the feasible working hours inside the greenhouse. Therefore, the natural-ventilation-only scenarios analyzed in this section should be interpreted as worst-case thermal conditions, highlighting the need for additional mitigation strategies such as shading, active cooling, or adjustment of the cropping period to avoid the most extreme summer conditions. In this context, the subsequent analyses of FCU-based cooling, fogging systems, and the hybrid cooling configuration provide practical options to reduce the indoor temperature to levels that are more compatible with safe tomato cultivation.

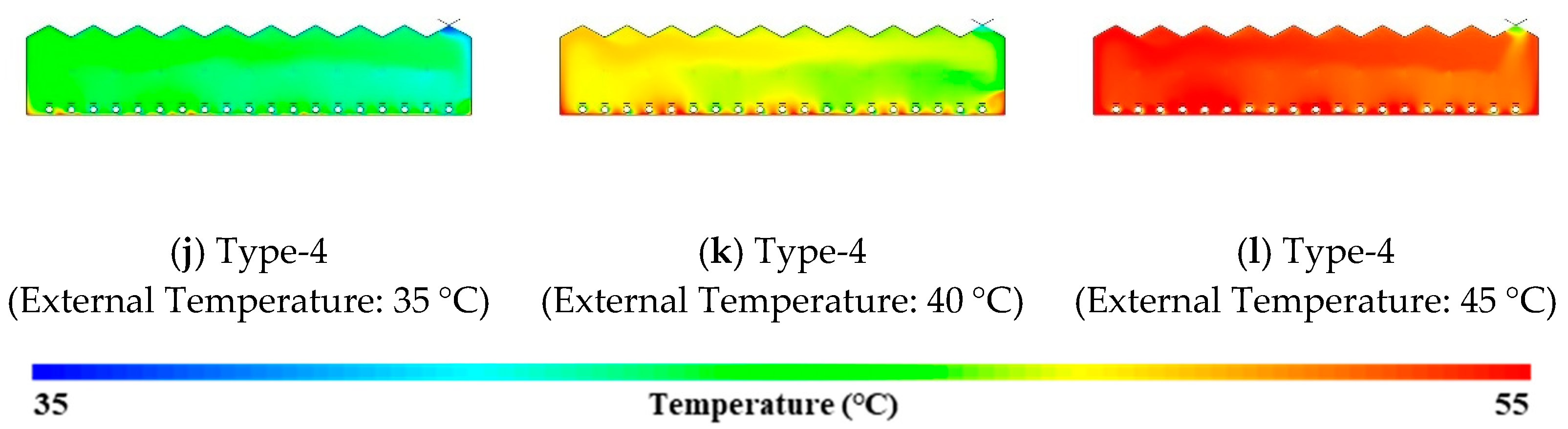

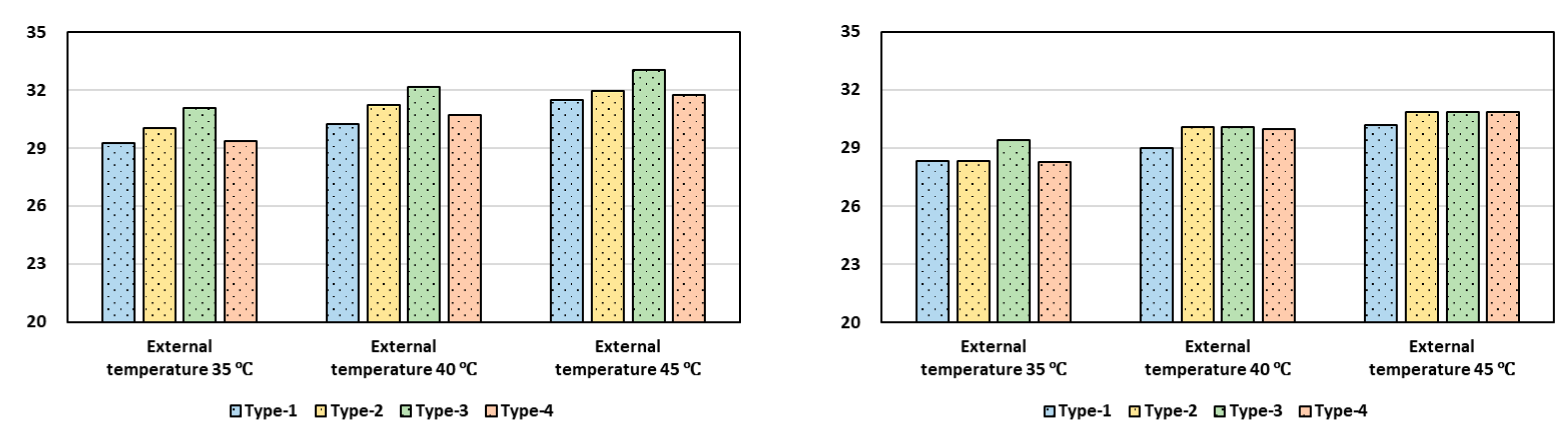

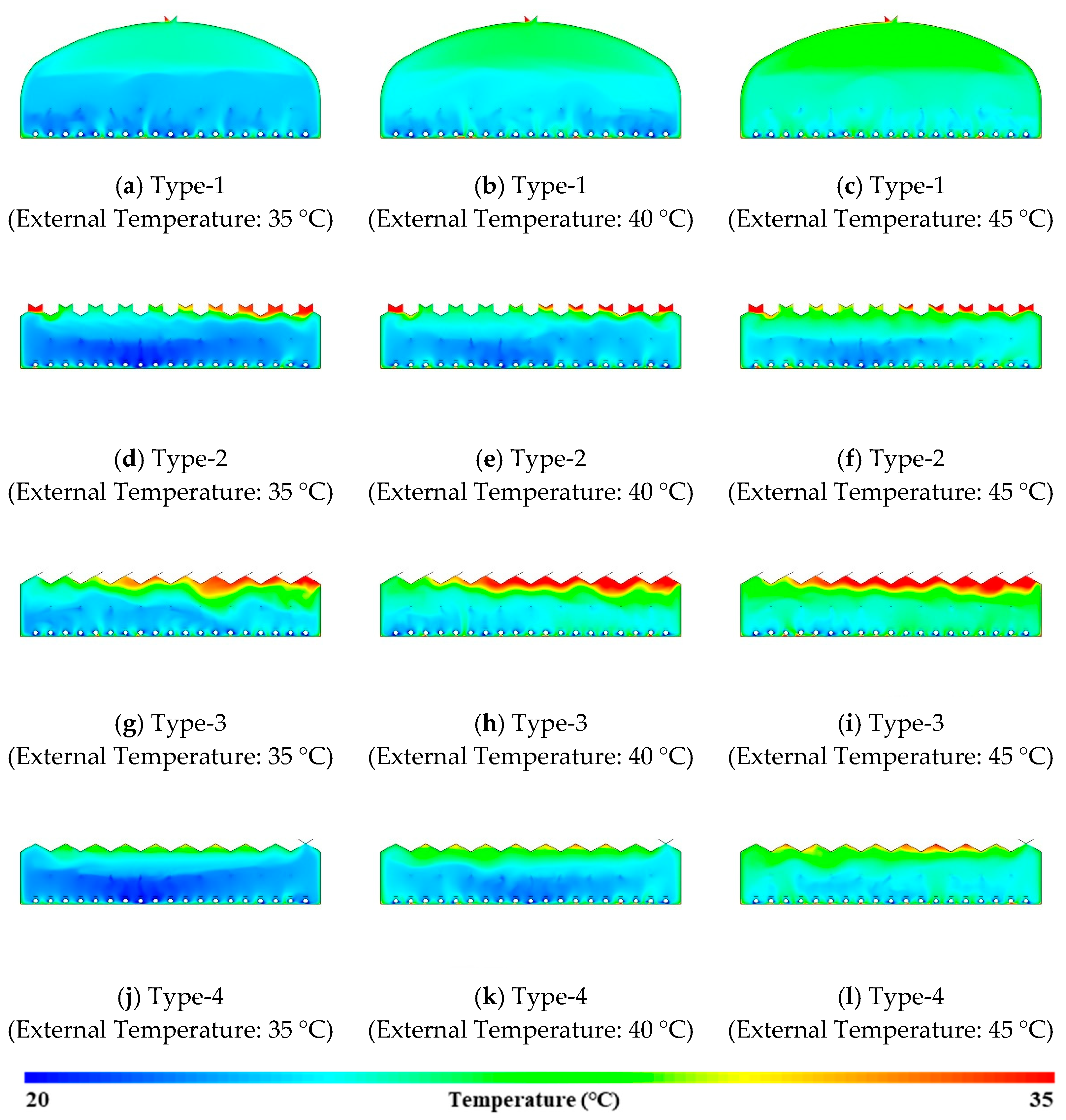

3.1.2. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses Under Fogging System Operation

The thermal environmental response characteristics of the high-height wide-type (Type-1) and Venlo-type greenhouses (Type-2, Type-3, and Type-4) with the application of a fogging system were compared and analyzed. The spray amounts were set at 27 and 35 L·min

−1, and CFD simulations were conducted. The main results are presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

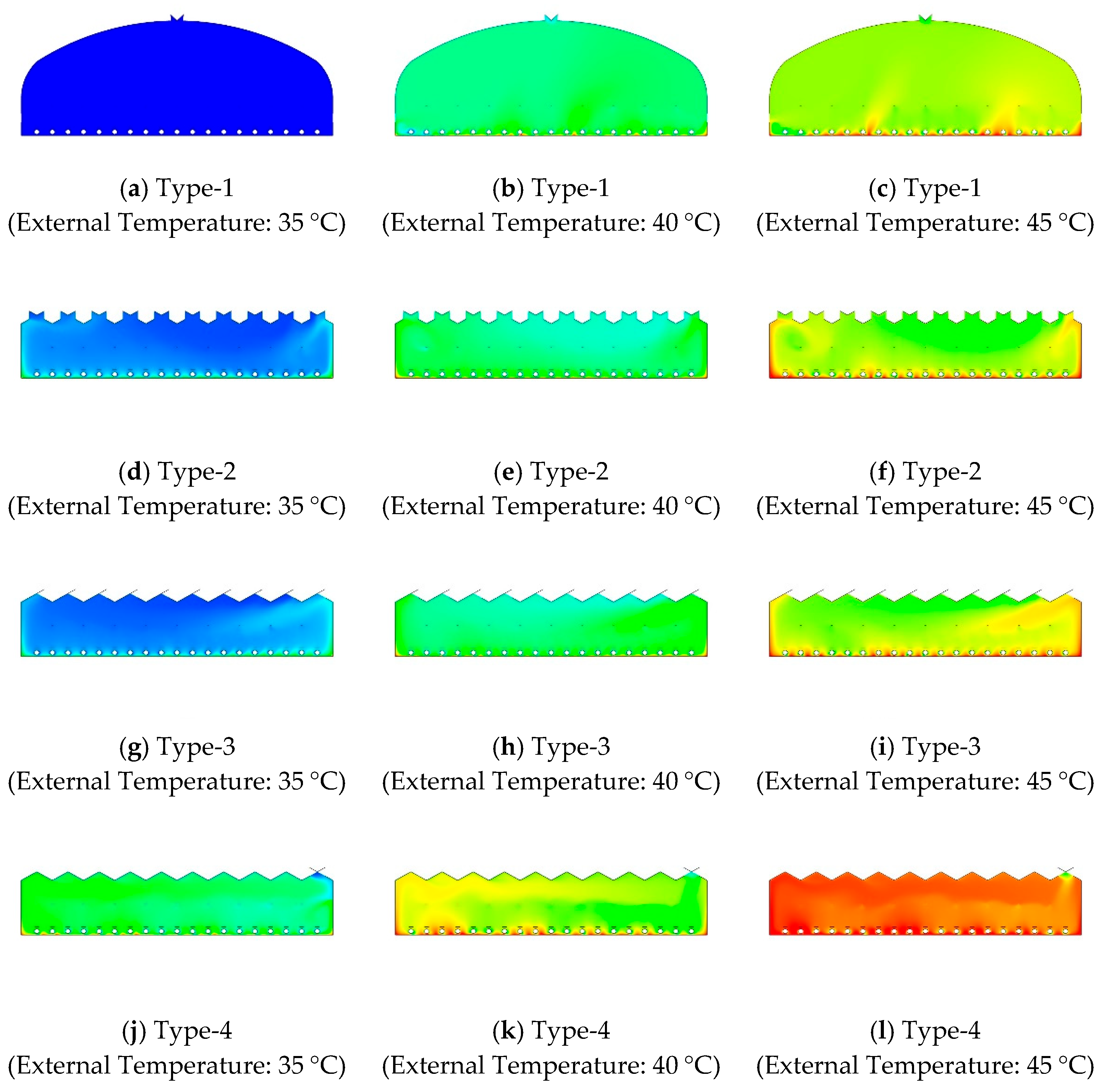

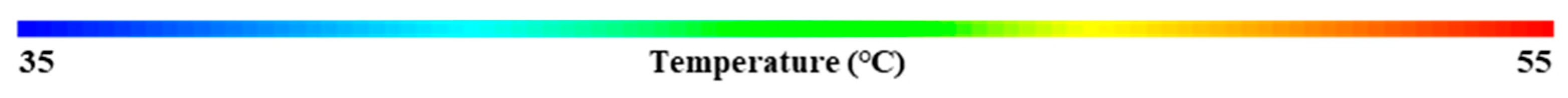

The analysis showed that the difference in the average internal and root zone temperatures due to the increase in spray amount was less than 1 °C, indicating that the cooling effect from changes in the spray amount was limited. From an energy-balance perspective, the additional latent cooling associated with increasing the spray rate from 27 to 35 L·min−1 is relatively small compared with the combined solar and convective heat gains entering the greenhouse, so that the average air and root-zone temperatures remain primarily governed by the overall ventilation-driven heat removal. In all greenhouse types, the fogging system alone was insufficient to reach the optimal growth temperature range for tomatoes (17–27 °C). However, the high-height wide-type greenhouse consistently maintained lower average internal and root zone temperatures than the Venlo-type greenhouse.

In particular, the high-height wide-type greenhouse exhibited a relatively higher uniformity in heat distribution, which can be attributed to the effective dissipation of internal heat owing to the buoyancy-driven ventilation effect from its high sidewalls and skylight structure. When the fogging system was operated, all greenhouse types showed an average temperature reduction of approximately 3 °C compared to the conditions with open ventilation windows, and the spatial variation in the temperature distribution also tended to decrease.

In contrast, under the Type-4 conditions, the rate of increase in the internal temperature was the highest as the outdoor temperature increased. This is believed to be due to the relatively low ventilation rate, which prevents effective dissipation of the accumulated heat inside.

For the Venlo-type greenhouses, a skylight opening rate of at least 50–100% must be maintained during fogging system operation to ensure sufficient ventilation. Increasing the ventilation window area in the high-height wide-type greenhouse is expected to contribute to higher air intake, providing additional temperature reduction effects.

Ultimately, using a fogging system alone has limitations in maintaining the optimal temperature for crop growth in high-temperature environments and necessitates a more complex cooling strategy. Nevertheless, the high-height, wide-type greenhouse showed structural advantages in terms of thermal environmental control, suggesting that this structure can be applied as a high-temperature-responsive greenhouse in the future. Although humidity and condensation were not explicitly simulated in this study, it should be noted that increased fogging rates in practice are likely to raise indoor relative humidity and condensation risk, potentially enhancing disease pressure and operational constraints. Therefore, the practical use of fogging systems should balance the benefit of temperature reduction against these humidity-related side effects and be combined with sufficient ventilation and, when necessary, complementary measures such as shading or additional cooling.

3.2. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses Under Forced Ventilation

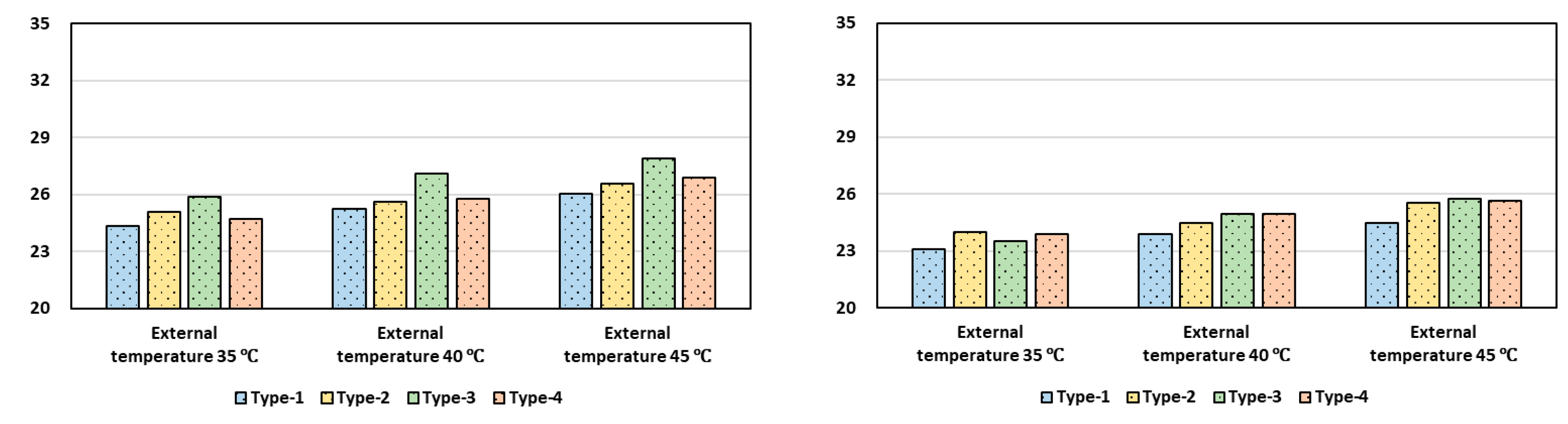

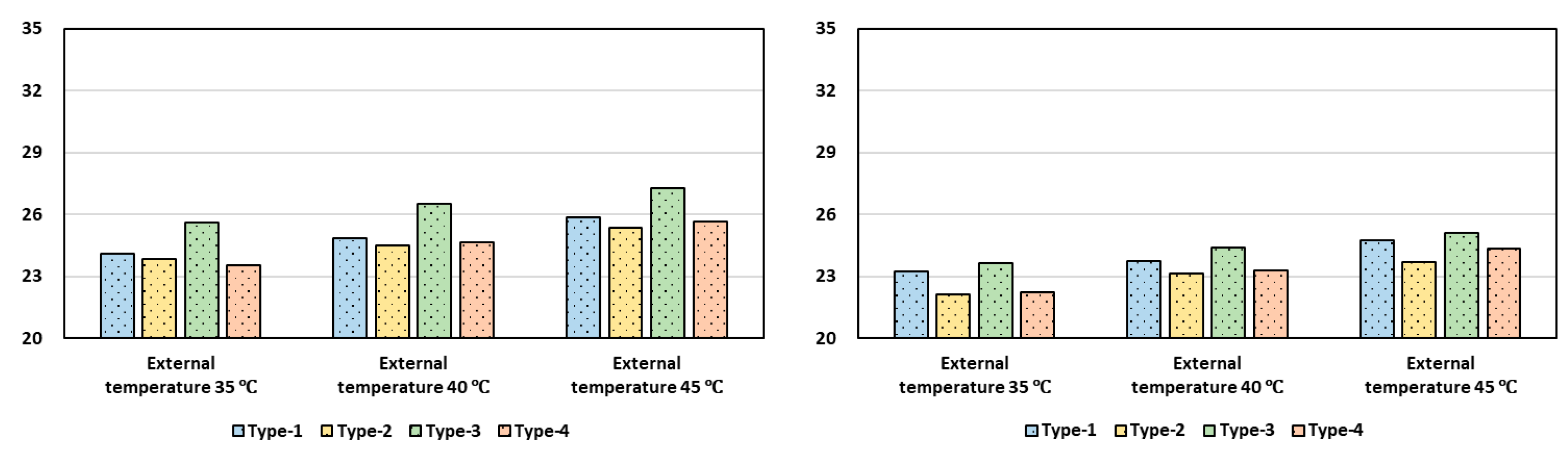

3.2.1. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses Using the FCU System

The thermal environmental responses of the high-height wide-type (Type-1) and Venlo-type greenhouses (Type-2, Type-3, and Type-4) under the application of an FCU system were compared and analyzed. Simulations were performed with FCU discharge temperatures set at 15 and 20 °C, and the main results are presented in

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18.

In the high-height wide-type greenhouse, when the FCU discharge temperature was set to 20 °C, the average internal and root zone temperatures approached the optimal growth range for tomatoes (17–27 °C) but did not fully meet the target. However, when the discharge temperature was lowered to 15 °C, the average internal and root zone temperatures remained stable within the optimal range, regardless of the outdoor temperature.

For the Venlo-type greenhouses, under the 20 °C FCU discharge temperature condition, all three types exhibited average temperatures of 29–30 °C, exceeding the optimal growth temperature. When the discharge temperature was lowered to 15 °C, the root zone temperature reached the optimal growth range; however, the average internal temperature remained relatively high. Notably, Type-3 exhibited an internal average temperature of approximately 27.90 °C under the outdoor temperature condition of 45 °C, with the greatest unevenness in temperature distribution observed. This was attributed to the turbulence formed when hot outdoor air collided with the closed side windows on the windward side and entered through the leeward-side windows, causing heat accumulation.

These results suggest that when operating the FCU system in a Venlo-type greenhouse, localized heat accumulation may occur owing to structural constraints, and ensuring minimal ventilation could help improve the cooling efficiency. In contrast, the high-height wide-type greenhouse maintained the lowest and most uniform temperature distribution under the 15 °C FCU discharge condition, demonstrating its structural advantage in coping with high-temperature environments.

This analysis is significant for identifying the limitations of thermal environmental control when using the FCU system alone. It provides foundational data for the potential application of high-height wide-type greenhouses. For Venlo-type greenhouses, the results also suggest several possible structural and operational optimization measures, such as maintaining a minimum opening on the windward-side windows even during FCU operation to reduce recirculation, increasing or repositioning roof vents above zones of heat accumulation, and, if necessary, installing simple baffles or deflectors to guide the FCU discharge air toward stagnant regions. These options could be considered in future design and retrofitting efforts to alleviate local heat build-up and enhance the overall cooling performance. In the future, integrating FCU systems with supplementary cooling systems (e.g., fogging or natural ventilation) will highlight the need for a composite cooling strategy to achieve energy efficiency and growth stability.

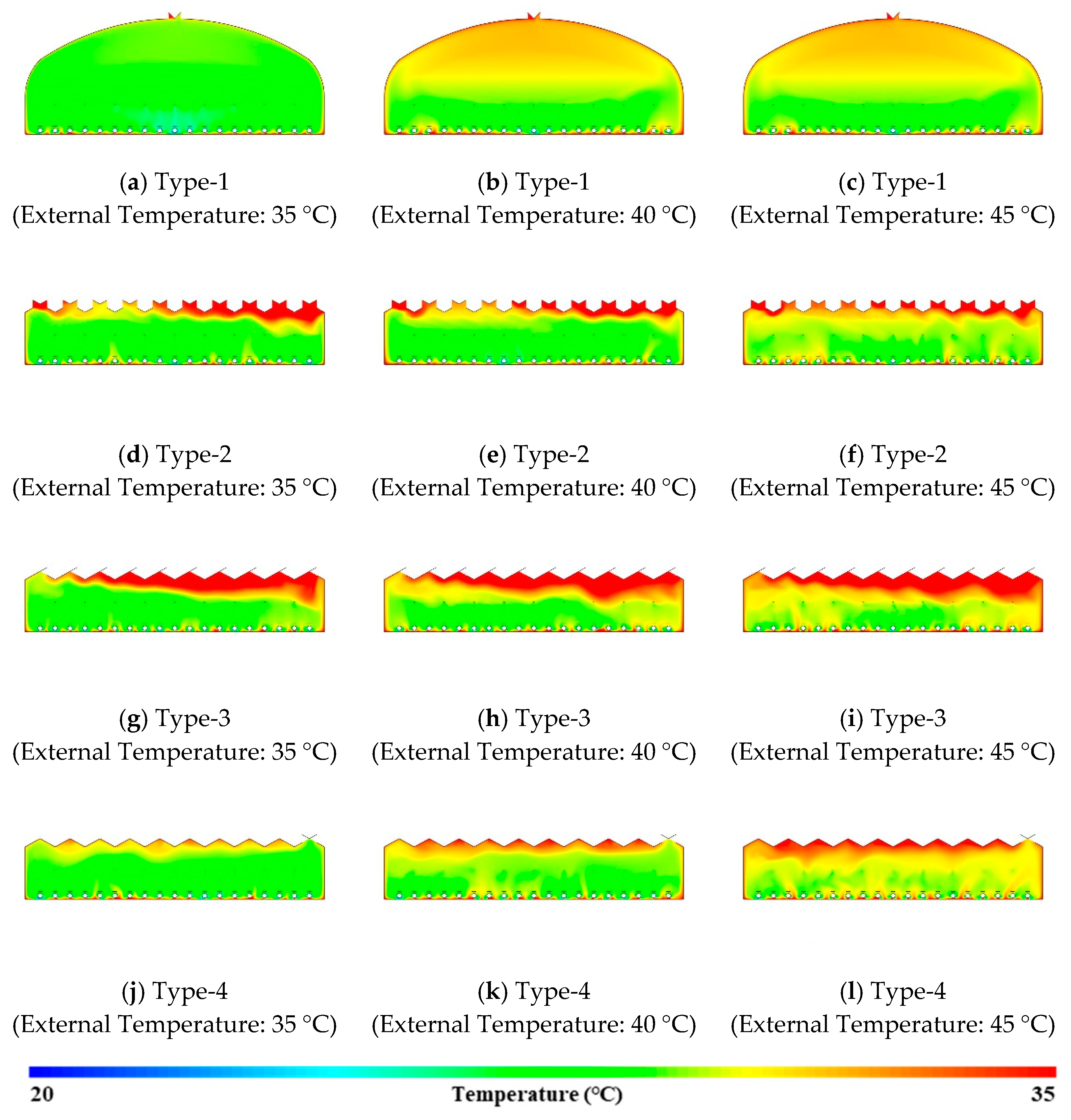

3.2.2. Thermal Environment Analysis of High-Height Wide-Type and Venlo-Type Greenhouses Using a Hybrid Cooling System

To analyze the thermal environmental response under hybrid cooling conditions, CFD simulations were conducted for the high-height wide-type (Type-1) and Venlo-type greenhouses (Type-2, Type-3, Type-4), combining a fogging system (spray rate of 35 L·min

−1) and an FCU system (discharge temperatures of 15 and 20 °C). The results of this analysis are shown in

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

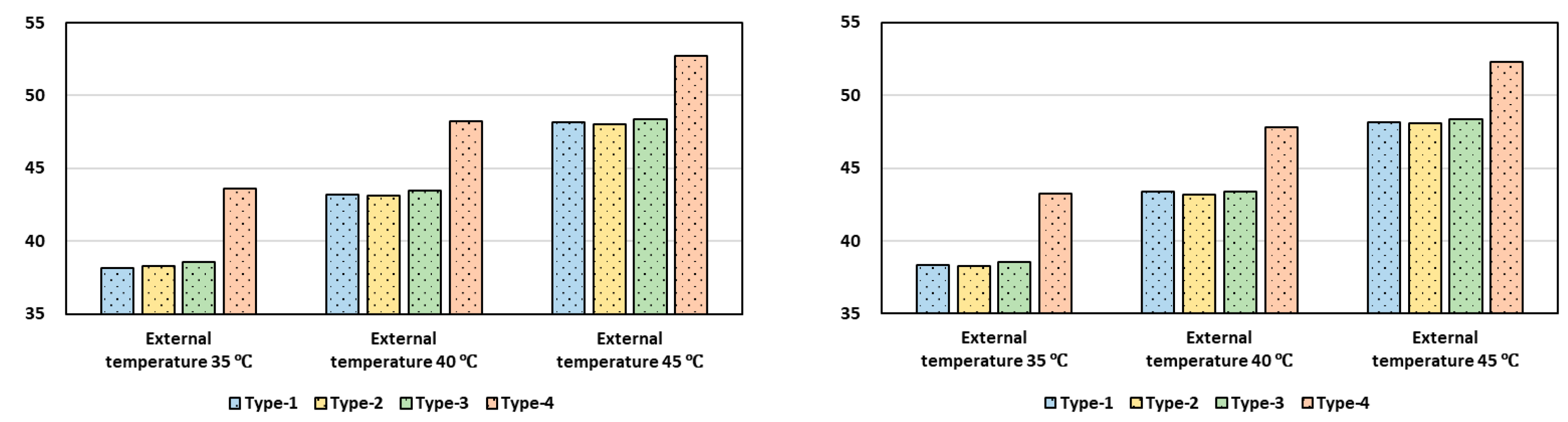

Under the condition of an FCU discharge temperature of 20 °C, the hybrid system resulted in a decrease of approximately 1 °C in the average internal and root zone temperatures across all greenhouse types compared to the operation of the FCU alone. Additionally, the spatial uniformity of heat distribution exhibited an increasing trend. However, even under this condition, the optimal growth temperature range for tomatoes (17–27 °C) was not fully satisfied across all greenhouse types.

The high-height wide-type greenhouse exhibited the highest uniformity in internal temperature distribution when the hybrid system was applied, which can be attributed to the efficient distribution of fogging and FCU-cooling air throughout the upper layers owing to its high sidewalls and open structure. Among the Venlo-type greenhouses, Type-4 exhibited the lowest average internal and root zone temperatures, which is believed to result from the restricted outdoor air infiltration structure, favoring heat removal from the interior.

Furthermore, when the FCU discharge temperature was lowered to 15 °C, the cooling effect of the hybrid system became more prominent. The internal average temperature and root zone temperature decreased by more than 4 °C across all greenhouse types compared to the operation of the FCU alone, and the uniformity of the temperature distribution also exhibited clear improvement. Notably, the high-height wide-type greenhouse maintained the most stable and uniform thermal environment under all outdoor temperature conditions.

For Type-3, because only the leeward side windows were open, the outdoor air intake was concentrated in a vortex pattern, leading to local heat accumulation. Consequently, the internal average temperature was relatively high at 27.29 °C. However, the root zone average temperature was analyzed to be 25.11 °C, remaining stable within the optimal growth range.

These results suggest that a single cooling system alone is insufficient to effectively control the internal temperature of the greenhouse under high-temperature conditions, and that applying a hybrid system can significantly improve the cooling efficiency and ensure temperature uniformity. In particular, the high-height wide-type greenhouse exhibited the most uniform and lowest temperature distribution when the hybrid system was used, presenting itself as a structurally optimal alternative for high-temperature responses.

The findings of this study provide quantitative data on the thermal environmental response of a high-height wide-type greenhouse under hybrid cooling conditions before empirical testing. From an energy perspective, however, maintaining an FCU discharge temperature of 15 °C is expected to require substantially higher cooling energy than operation at 20 °C, because the coefficient of performance of chillers or heat pumps generally decreases as the temperature lift increases. HVAC energy guidelines indicate that increasing the chilled-water supply temperature by about 1 °C can reduce chiller input energy by roughly 3–4%, implying that lowering the supply or discharge temperature from 20 to 15 °C could increase cooling energy demand on the order of 15–20% for the same cooling load [

45]. Accordingly, the 15 °C discharge cases should be interpreted as thermally favorable but energetically more demanding operating scenarios rather than as a universal design condition. In the future, these results could be used as foundational data for the design of high-temperature-responsive greenhouses, in conjunction with empirical experiments and detailed energy analyses.

4. Discussion

This study quantitatively evaluated the thermal environmental performance of a high-height wide-type greenhouse, a new greenhouse structure designed to effectively respond to high-temperature conditions during summer owing to climate change. Using computational fluid dynamics prior to empirical testing, a comparative analysis was performed with an existing Venlo-type greenhouse by analyzing the internal thermal response under different structural configurations and cooling scenarios.

Under natural ventilation conditions, the high-height wide-type greenhouse exhibited higher ventilation rates and lower average internal temperatures than the Venlo-type greenhouse; however, as outdoor temperature increased, both greenhouses exceeded the optimal growth temperature range for tomatoes (17–27 °C), confirming that natural ventilation alone is insufficient to cope with high-temperature summer conditions. When a fogging system was operated, the overall temperature reduction was modest, but the high-height wide-type greenhouse maintained lower average temperatures and a more uniform heat distribution than the Venlo-type configurations. Under FCU and hybrid cooling scenarios, the internal average and root zone temperatures reached or approached the optimal growth range only when the FCU discharge temperature was set to 15 °C, and the hybrid system achieved the largest temperature reduction (approximately 4–5 °C) and the highest spatial uniformity. Across all cooling scenarios, the high-height wide-type greenhouse consistently performed better than the Venlo-type greenhouse under the simulated conditions in terms of ventilation performance, cooling effectiveness, and temperature distribution uniformity, suggesting potential structural advantages for maintaining a more stable thermal environment under high-temperature conditions.

At the same time, it should be emphasized that the present study relies entirely on CFD simulations performed prior to full-scale experimental testing, and direct model validation against measured data for the high-height wide-type greenhouse was not yet possible. The numerical setup adopted in this work (turbulence modeling, boundary conditions, crop porous-media representation, and cooling-system implementation) follows approaches that have been used and validated in previous greenhouse CFD studies; however, the results reported here should still be interpreted as a preliminary design-stage assessment.

In addition, both the crop canopy and the fogging system were represented in an idealized manner: the tomato plants were modeled as a homogeneous porous medium with constant aerodynamic and heat-transfer parameters, and the fogging system was implemented as a distributed cooling and latent heat source without explicitly resolving droplet-scale spray and evaporation processes. These simplifications may cause discrepancies in local temperature and humidity fields, particularly near the plants and nozzles, and the absolute values of the predicted variables should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, because the same modeling assumptions were consistently applied to all greenhouse types and cooling scenarios, the comparative trends in ventilation performance, cooling effectiveness, and temperature distribution uniformity between the high-height wide-type and Venlo-type greenhouses are expected to remain robust. Furthermore, the present simulations were performed under steady-state boundary conditions with fixed extreme summer temperatures and wind forcing, and did not resolve diurnal variations in solar radiation, outdoor temperature, or dynamic control responses; consequently, the results should be interpreted as quasi-equilibrium snapshots of peak heat-wave conditions rather than as a full representation of day-long greenhouse operation.

In future work, model validation based on monitored temperature distributions and airflow measurements in full-scale high-height wide-type greenhouses, together with energy consumption analyses for different cooling-system combinations, will be essential to confirm and refine the present findings and to more precisely evaluate the practical applicability and operational efficiency of this structural concept. Such validation studies could, for example, employ on-site sensor networks that record air temperature, humidity, and air velocity at multiple heights from the root zone to the upper air space along the windward–leeward direction, while the energy performance of the cooling systems is evaluated using indicators such as cooling energy consumption per unit floor area or per unit marketable yield.

5. Conclusions

This study used CFD simulations to pre-evaluate the thermal environmental performance of a high-height wide-type greenhouse recently developed to cope with summer heat stress and to compare it with a conventional Venlo-type structure under extreme summer conditions in South Korea. The main findings under the simulated conditions can be summarized as follows:

Under natural ventilation, the high-height wide-type greenhouse achieved higher ventilation rates and lower average internal temperatures than the Venlo-type greenhouse. However, as outdoor temperature increased from 35 to 45 °C, the internal temperatures in both structures exceeded the optimal growth range for tomatoes (17–27 °C), indicating that natural ventilation alone is insufficient to maintain suitable thermal conditions during severe heat waves.

When a fogging system was applied, all greenhouse types exhibited an average temperature reduction of approximately 3 °C compared with natural ventilation, and temperature uniformity improved. The additional cooling gained by increasing the spray rate from 27 to 35 L·min−1 was limited (<1 °C), reflecting the relatively small incremental latent cooling compared with the combined solar and convective heat gains. Even so, the high-height wide-type greenhouse consistently maintained lower average internal and root-zone temperatures and more uniform heat distributions than the Venlo-type configurations.

Under FCU operation, the average internal and root-zone temperatures in the high-height wide-type greenhouse approached or entered the optimal tomato growth range only when the FCU discharge temperature was set to 15 °C, and the temperature distribution remained comparatively uniform. In the Venlo-type greenhouses, local heat accumulation and non-uniformity were more pronounced, particularly in configurations with restricted ventilation paths, suggesting that structural and operational modifications are required to avoid stagnant hot zones during FCU-based cooling.

The hybrid cooling scenarios, combining FCU operation with fogging, produced the largest temperature reductions (approximately 4–5 °C) and the highest degree of thermal uniformity among all tested cases. Across all cooling scenarios, the high-height wide-type greenhouse performed better than the Venlo-type greenhouse under the simulated conditions in terms of ventilation performance, cooling effectiveness, and temperature distribution uniformity, suggesting that it is a promising structural option for high-temperature-responsive greenhouse design when coupled with appropriately configured cooling systems.

Overall, the results indicate that high-height wide-type greenhouses, especially when integrated with hybrid cooling strategies, have strong potential to mitigate heat stress and stabilize the thermal environment under extreme summer conditions. The findings provide quantitative design-stage information that can support structural selection and cooling-system configuration prior to empirical testing and can serve as foundational data for subsequent validation experiments and detailed energy and economic analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K. and C.K.; methodology, C.K.; software, C.K.; validation, C.K., R.K., H.S. and J.K.; formal analysis, C.K.; investigation, C.K. and H.S.; resources, R.K. and J.K.; data curation, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, R.K., H.S. and J.K.; visualization, C.K.; supervision, R.K.; project administration, R.K.; funding acquisition, R.K. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by an Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP)—ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (IITP-2025-RS-2024-00438335) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00352168).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| FCU | Fan Coil Unit |

References

- Chapman, S.C.; Watkins, N.; Stainforth, D.A. Warming trends in summer heatwaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 1634–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Lewis, S.C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Xu, W.; Shi, P. Mapping global population exposure to heatwaves. In Atlas of Global Change Risk of Population and Economic Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Cha, D.H.; Lee, M.I.; Min, K.H.; Kim, J.; Jun, S.Y.; Choi, Y. Recent changes in heatwave characteristics over Korea. Clim. Dyn. 2020, 55, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabaev, A.; Kerr, R.B.; Hasegawa, T.; Pradhan, P.; Wreford, A.; Pahlen, M.C.; Gurney-Smith, H. Severe climate change risks to food security and nutrition. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 39, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, C. Heat is associated with short-term increases in household food insecurity in 150 countries and this is mediated by income. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.L.; Tseng, W.C.; Chen, C.C. Climate change impacts on crop yields across temperature rise thresholds and climate zones. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchonkouang, R.D.; Onyeaka, H.; Nkoutchou, H. Assessing the Vulnerability of Food Supply Chains to Climate Change-Induced Disruptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 171047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Randall, M.; Lewis, A. Factors Affecting Crop Prices in the Context of Climate Change—A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamuah, S.; Kiran, N.D.; Amin, M.; Sultana, N.; Hansda, N.M.H.; Noopur, K. Protected vegetable crop production for long-term sustainable food security. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2024, 30, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Singh, L.; Sharma, D.; Singh, K.; Sudan, S.; Koul, V. Trends in greenhouse production technology with special reference to protected cultivation of horticultural crops. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 26549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI). Current Status and Countermeasures for Heat Wave Damage in Rural Areas (KREI Issue Analysis No. 53); Korea Rural Economic Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018; Available online: https://www.krei.re.kr (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Yamanaka, R.; Kawashima, H. Development of cooling techniques for small-scale protected horticulture in mountainous areas in Japan. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2021, 55, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, H. Study on heating and cooling performance of air-to-water heat pump system for protected horticulture. Energies 2022, 15, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Moon, J.P.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, S.H. Development of fog cooling control system and cooling effect in greenhouse. Prot. Hortic. Plant Fact. 2020, 29, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banakar, A.; Montazeri, M.; Ghobadian, B.; Pasdarshahri, H.; Kamrani, F. Energy analysis and assessing heating and cooling demands of closed greenhouse in Iran. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 25, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-H.; Min, D.-H.; Yum, S.-H.; Won, Y.-S. Numerical study on ventilation performance for a Venlo-type greenhouse. J. Comput. Fluids Eng. 2021, 26, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, I.-B.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-G.; Choi, Y.-B.; Decano-Valentin, C.; Cho, J.-H.; Jeong, H.-H.; Yeo, U.-H. Numerical analysis of ventilation efficiency of a Korean Venlo-type greenhouse with continuous roof vents. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Choi, M.K.; Cho, M.W.; Kim, J.H.; Seo, T.C.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, S.Y. Structural Performance Evaluation of a Multi-span Greenhouse with Venlo-type Roof According to Bracing Installation. J. Bio-Environ. Control 2022, 31, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiu, A.; Adesanya, M.A.; Na, W.H.; Ogunlowo, Q.O.; Akpenpuun, T.D.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, H.W. Thermal performance and energy cost of Korean multispan greenhouse energy-saving screens. Energy 2023, 285, 129514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, M.R.O.; Abbas, A.; Wang, X.; Elahi, E. Thermo-Environmental Assessment of a Heated Venlo-Type Greenhouse in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.W.; Lee, I.B.; Kwon, K.S. Evaluation of wind pressure acting on multi-span greenhouses using CFD technique, Part 1: Development of the CFD model. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 164, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrán, E.A.; Baeza, E.J.; Bojacía, C.R. Transient CFD analysis of the natural ventilation of three types of green-houses used for agricultural production in a tropical mountain climate. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 188, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, I.B.; Yeo, U.H.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, R.W.; Kwon, K.S. Dynamic energy model of a naturally ventilated duck house and comparative analysis of energy loads according to ventilation type. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 219, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrami, M.; Mutlum, C.D.; Javadi, A.A.; Salah, A.H.; Fath, H.E.S.; Dibaj, M.; Farmani, R.; Mohammed, R.H.; Negm, A. Analysis of inlet configurations on the microclimate conditions of a novel standalone agricultural greenhouse for Egypt using CFD. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierart, A.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Boulard, T. CFD Model Verification and Aerodynamic Analysis in Large-Scaled Venlo Greenhouse Complex for Tomato Cultivation. Preprints 2022, 2023070899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghibeche, I.; Nourani, A.; Naas, T.T.; Benziouche, S.E.; Buchholz, M.; Buchholz, R. A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling in a new design of closed greenhouse. Stud. Eng. Exact. Sci. 2024, 5, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibwika, A.; Seo, H.-J.; Seo, I.-H. CFD Model Verification and Aerodynamic Analysis in Large Scaled Venlo Greenhouse for Tomato Cultivation. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 1395–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Yue, X.; Liu, X.; Tian, S.; Li, T. Evaluation of airflow pattern and thermal behavior of the arched green-houses with designed roof ventilation scenarios using CFD simulation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Li, B.; Lu, H.; Guo, J.; Dong, Z.; Yang, F.; Lü, E.; Liu, Y. Optimization of Greenhouse Structure Parameters Based on CFD Simulation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.W.; Choi, M.K.; Kim, H.N.; Kang, D.; Lee, S.; Son, J.; Yoon, Y.C. Estimation of the required number of fan coil unit for surplus solar energy recovery of greenhouse. J. Bio-Environ. Control 2016, 25, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.B.; Yun, N.K. Development of an aerodynamic simulation for studying microclimate of plant canopy in greenhouse. J. Bio-Environ. Control 2006, 15, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fatnassi, H.; Boulard, T.; Demrati, H. Use of computational fluid dynamic tools to model the coupling of greenhouse climate with crop canopy. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 230, 388–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazgaou, A.; Fatnassi, H.; Bouharroud, R.; Tiskatine, R.; Wifaya, A.; Demrati, H.; Bammou, L.; Aharoune, A.; Bouirden, L. CFD modeling of the microclimate in a green house using a rock bed thermal storage heating system. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, M.; Al-Rikabi, S.; Santolini, E.; Pulvirenti, B.; Barbaresi, A.; Torreggiani, D.; Tassinari, P. Definition of thermal comfort of crops within naturally ventilated greenhouses. J. Agric. Eng. 2023, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Liu, Q.; Gao, L.; Liu, K.; Shi, R.; Ta, N. CFD-based simulation of crop canopy temperature and humidity in double-film solar greenhouse. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 8874468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, I.B.; Kim, R.W. Evaluation of wind-driven natural ventilation of single-span greenhouses built on reclaimed coastal land. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 171, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, H.; He, X.; Zong, C.; Song, W.; Zhao, S. CFD Simulation and Uniformity Optimization of the Airflow Field in Chinese Solar Greenhouses Using the Multifunctional Fan–Coil Unit System. Agronomy 2023, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambelluca, T.W.; Shuai, X.; Barnes, M.L.; Alliss, R.J.; Longman, R.J.; Miura, T.; Businger, A.D. Evapotranspiration of Hawai ‘i. Final Report Submitted to the US Army Corps of Engineers—Honolulu District, and the Commission on Water Resource Management, State of Hawai ‘I; Ecohydrology Lab: Vancouver, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S.; Seo, D.; Shin, H. Empirical analysis on the cooling load and evaporation efficiency of fogging system in greenhouses. Prot. Hortic. Plant Fact. 2015, 24, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Y. Simulation and analysis on thermal comfort of air-conditioned room with different air supply temperature and velocity. In The International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.C.; Ferng, Y.M.; Shih, C.K. CFD evaluation of turbulence models for flow simulation of the fuel rod bundle with a spacer assembly. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 40, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitel, M.; Wenger, E. Air exchange and ventilation efficiencies of a monospan greenhouse with one inflow and one outflow through longitudinal side openings. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 119, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H.; Jung, S.W.; Kwon, S.G.; Park, J.M.; Choi, W.S.; Kim, J.S. Comparative study on efficiencies of naturally ven-tilated multi-span greenhouses in Korea. Korean Soc. Inf. Control 2017, 20, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Systems and Equipment, 1996 ed.; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the CFD simulation process used to pre-evaluate the thermal environment of a high-height wide-type greenhouse.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the CFD simulation process used to pre-evaluate the thermal environment of a high-height wide-type greenhouse.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse.

Figure 3.

Schematic layout of the fan coil unit (FCU) system configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse (FCU length = 38 m; spacing: 2 m).

Figure 3.

Schematic layout of the fan coil unit (FCU) system configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse (FCU length = 38 m; spacing: 2 m).

Figure 4.

Schematic layout of the fog system configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse (pipe spacing: 4 m; nozzle spacing: 1.5 m).

Figure 4.

Schematic layout of the fog system configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse (pipe spacing: 4 m; nozzle spacing: 1.5 m).

Figure 5.

CFD mesh configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse. The red surface indicates the pressure outlet, the blue surface indicates the velocity inlet, and the yellow region indicates the wall.

Figure 5.

CFD mesh configuration for the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse. The red surface indicates the pressure outlet, the blue surface indicates the velocity inlet, and the yellow region indicates the wall.

Figure 6.

Simulation setup of the external wind environment for CFD analysis (wind direction: 0°).

Figure 6.

Simulation setup of the external wind environment for CFD analysis (wind direction: 0°).

Figure 7.

Classification of CFD simulation case by ventilation strategy and cooling system configuration.

Figure 7.

Classification of CFD simulation case by ventilation strategy and cooling system configuration.

Figure 8.

Type setting according to greenhouse type.

Figure 8.

Type setting according to greenhouse type.

Figure 9.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; Unit: °C).

Figure 9.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; Unit: °C).

Figure 10.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (left and right, respectively; Unit: °C).

Figure 10.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (left and right, respectively; Unit: °C).

Figure 11.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 27 L·min−1; Unit: °C).

Figure 11.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 27 L·min−1; Unit: °C).

Figure 12.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (27 L·min−1 fogging; Unit: °C).

Figure 12.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (27 L·min−1 fogging; Unit: °C).

Figure 13.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; Unit: °C).

Figure 13.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; Unit: °C).

Figure 14.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (35 L·min−1 fogging; Unit: °C).

Figure 14.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (35 L·min−1 fogging; Unit: °C).

Figure 15.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; FCU: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 15.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; FCU: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 16.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (FCU discharge temperature: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 16.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (FCU discharge temperature: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 17.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; FCU: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 17.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; FCU: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 18.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (FCU discharge temperature: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 18.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (FCU discharge temperature: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 19.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; FCU: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 19.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; FCU: 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 20.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (Fog + FCU 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 20.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (Fog + FCU 20 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 21.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; FCU: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 21.

Air temperature contour (wind: 2 m·s−1, 0°; fog: 35 L·min−1; FCU: 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 22.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (Fog + FCU 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Figure 22.

Comparison of average greenhouse air and crop canopy/root zone temperatures (Fog + FCU 15 °C; Unit: °C).

Table 1.

Specifications of the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse.

Table 1.

Specifications of the high-height wide-type greenhouse and the Venlo-type greenhouse.

| Type | High-Height Wide-Type

Greenhouse | Venlo-Type

Greenhouse |

|---|

| Scale | Roof height | 3.8 m | 7 m |

| Eave height | 15.5 m | 8.1 m |

| Width | 52 m | 8 m |

| Length | 84 m | 40 m |

| Floor Area | 4368 m2 | 320 m2 |

Table 2.

Boundary conditions applied in the CFD simulation.

Table 2.

Boundary conditions applied in the CFD simulation.

| Type | Values |

|---|

| Outdoor air temperature (°C) | 35, 40, 45 |

| External wind conditions | Wind speed (m·s−1) | 2.0 |

| Wind direction (°) | 0 |

| Tomato crop | Latent energy sources (W·m−3) | −41.81 |

| Viscous resistance (m−2) | 2.53 |

| Inertial resistance (m−1) | 1.60 |

| FCU system | Discharge temperature (°C) | 15, 20 |

| Airflow rate (m3·min−1) | 200 |

| Fog system | Spray volume (L·min−1) | 27, 35 |

| Source term (W·m−3) | −211.88, −274.68 |

| Heat flux | Inside greenhouse (W·m−2) | 270, 290, 310 |

| External domain (W·m−2) |

Table 3.

Configuration of CFD simulation scenarios by external air temperature, greenhouse structure, and cooling system operation.

Table 3.

Configuration of CFD simulation scenarios by external air temperature, greenhouse structure, and cooling system operation.

| External Temperature | Greenhouse

Type | Cooling Method | Variable

Type | Variable

Value | No. of

Cases |

|---|

| 35, 40, 45 °C | 2

(Type-1, 2) | Natural

ventilation | - | - | 6 |

| 35, 40, 45 °C | 4

(Type-1, 2, 3, 4) | Fogging

system | Spray volume (L·min−1) | 27, 35 | 24 |

| 35, 40, 45 °C | 4

(Type-1, 2, 3, 4) | FCU

system | Discharge temperature (°C) | 15, 20 | 24 |

| 35, 40, 45 °C | 4

(Type-1, 2, 3, 4) | Hybrid

(Fog + FCU) | Temperature + Spray | 15, 20 °C

(35 L·min−1) | 24 |

| Total | 78 |

Table 4.

Comparison of greenhouse and crop temperatures under different external temperatures and ventilation efficiencies.

Table 4.

Comparison of greenhouse and crop temperatures under different external temperatures and ventilation efficiencies.

| Greenhouse Type | External

Temperature (°C) | Average Greenhouse Air Temperature (°C) | Average Crop Canopy Temperature (°C) | Air

Exchange Rate

(min−1) |

|---|

| Type-1 | 35 | 39.93 | 40.77 | 0.45 |

| 40 | 45.32 | 46.21 |

| 45 | 50.69 | 52.61 |

| Type-2 | 35 | 41.48 | 41.14 | 0.2 |

| 40 | 47.15 | 47.19 |

| 45 | 52.60 | 52.62 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).