Abstract

One of the main factors influencing wheat productivity is nitrogen (N) management. This study examined the impact of varying N-fertilizer rates on spring wheat yield and N use efficiency by adjusting the “source-sink” relationship between assimilates and N accumulation and transport. The objective was to identify the optimal N rate for the region. The field experiment included five N-fertilizer rates: 0 kg ha−1 (N1), 52.5 kg ha−1 (N2), 105.0 kg ha−1 (N3), 157.5 kg ha−1 (N4), and 210.0 kg ha−1 (N5). Results indicated that the yield response was not proportional to N-fertilizer rates, with maximum biomass (6029 kg ha−1) and grain yield (2625 kg ha−1) achieved under N3. N fertilization primarily increased yield by regulating pre-anthesis translocation of assimilate and N. Assimilate translocation peaked at 105 kg N ha−1, increasing by 8.5–133.7% compared to other treatments. With increasing N input, N absorption efficiency and N partial factor productivity declined. The highest N agronomic use efficiency was observed under N3, which was 19.5–176.34% higher than other treatments. Overall, moderate N input (≈105 kg ha−1) optimizes yield and N-use efficiency, offering guidance for sustainable N management in dryland spring wheat production.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is a crucial macronutrient for crop growth, often referred to as the “food of food” [1]. It directly affects the buildup of aboveground assimilate, photosynthetic properties, physiological metabolism, and grain yield of crops [1,2]. Excessive N fertilization has grown in popularity in recent years in an effort to maximize crop productivity [3]. In China, only about 35% of the N fertilizer applied in agriculture is effectively absorbed by crops, with most losses occurring through ammonia volatilization, leaching, nitrification-denitrification, and runoff [4]. In addition to increasing the expense of agricultural production, this causes ecological problems such as soil biodiversity, groundwater pollution, increased soil acidity, and elevated greenhouse gas emissions [5,6].

As the three primary staple food crops globally, the yields of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), and maize (Zea mays L.) are crucial for ensuring food security [7,8,9]. Numerous studies have explored the impact of N fertilizer on these crops, revealing both common and distinct patterns. For rice, research focuses on reducing N loss from surface water and improving N use efficiency (NUE) during the tillering stage by optimizing N management [10]. For maize, studies often emphasize the precise application of ear fertilizer and flowering grain fertilizer to balance the relationship between its significant “sink” (grain) and “source” (photosynthetic products) [8]. In contrast, studies on wheat pay more attention to the effects of N rates on grain yield, protein content, processing quality, and N absorption efficiency at various growth stages, such as jointing and booting stages [11]. The relationship between source and sink directly impacts crop yield and N use efficiency. The results indicate that N-fertilizer rate significantly influences the development and function of source and sink organs in wheat [12]. Appropriate N fertilization can promote leaf area expansion, extend the functional period of leaves, enhance photosynthetic capacity, facilitate ear differentiation, and increase sink capacity and activity [13]. In the semi-arid Loess Plateau, Khakbazan et al. [14,15,16] have reported the overall response of wheat to N under specific water constraints. However, the impact of N application rates on N accumulation, translocation, and redistribution in spring wheat post-anthesis, as well as the physiological mechanisms of yield formation through regulating the source-sink relationship, remains to be further studied.

Wheat grain yield is influenced not only by the redistribution of assimilate and N stored pre-anthesis but also by the accumulation of assimilate and N post-anthesis [17,18,19]. The transfer of stored assimilates from pre-anthesis nutritional organs to grains can be significantly improved by appropriate N fertilization, thereby increasing grain yield [20,21]. Research shows that approximately 65% of N in wheat grains is derived from the re-translocation of N stored in nutrient organs pre-anthesis, while the remaining 35% is derived from N absorption post-anthesis [22]. Applying an appropriate amount of N fertilizer can promote the translocation of N from nutrient organs to grains, improve pre-anthesis N accumulation, extend the growth period, and facilitate the transfer of post-anthesis assimilate, thereby contributing to grain yield [23,24]. Conversely, excessive N fertilizer application may result in retention in stems and leaves, reducing N use efficiency [25].

N-use efficiency, which is closely related to the financial gains from agricultural production and ecological environmental safety, is a crucial indicator for evaluating N absorption efficiency [26,27,28]. Determining N-fertilizer rates based on the real N requirement of crops is crucial to advancing the “Second Green Revolution” and increasing the efficiency of N fertilizer consumption [29]. NUE is a complex characteristic that is controlled by a number of interrelated variables and impacted by aspects including migration, assimilation, translocation, and N absorption [30]. Thus, rational N fertilization and crop N fertilizer management optimization are essential in agricultural research.

We hypothesize that N fertilization controls wheat’s assimilation and N translocation, which in turn affects yield and N-use efficiency. By optimizing N-fertilizer rate, we can enhance NUE. Investigating the mode of assimilate translocation in wheat, characterizing N absorption, translocation, and redistribution, and clarifying the mechanisms underlying NUE of spring wheat under varying N fertilizer rates in the region are the main goals of this study. In addition, we aim to determine the optimal N fertilizer application rate for spring wheat in rainfed agriculture, providing a theoretical basis for sustainable wheat production in semi-arid areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

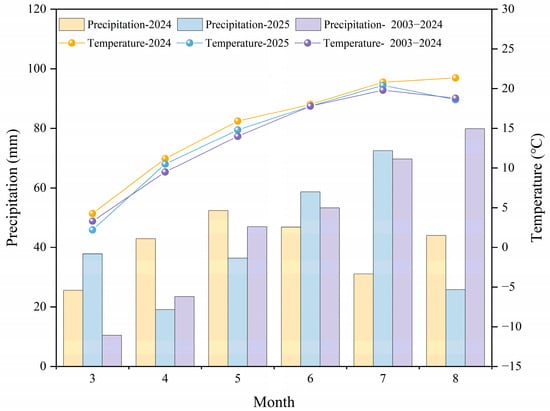

This study established a field experimental base in 2003 in the Anding District of Dingxi City, central Gansu Province, China (35°28′ N, 104°44′ E). This experiment was conducted continuously for 22 years. The data collection for this paper’s experiment was carried out in 2024 and 2025. The experimental area, at an altitude of 1971 m, is a typical semi-arid rain-fed agricultural region. The soil type is Calcaric Cambisol [31], commonly referred to as Huangmian. The soil at the site is of medium fertility, with key physicochemical properties in the 0–30 cm soil layer detailed in Table 1. The region receives an annual precipitation of 390.7 mm and has an evaporation rate of at 1531 mm, resulting in a coefficient of variation (CV) of 24.3%. The total annual solar radiation is 5930 MJ m−2, with a sunshine duration of 2480 h. The average annual temperature is 6.4 °C, with an accumulated temperature of ≥10 °C reaching 2240 °C and a frost-free period lasting 140 days. Meteorological data for the wheat growth period in 2024 and 2025 are reported in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Basic Physical and Chemical Properties of Soil in the Experimental Area (0–30 cm).

Figure 1.

Rainfall and temperature.

2.2. Experimental Design

The long-term study on N-fertilizer rates experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications. The field was divided into blocks, and within each block, all treatments were included and randomly assigned to individual plots. Each plot measured 30 m2 (3 m × 10 m). The experiment included five N-fertilizer rates: 0 kg N ha−1 (N1), 52.5 kg N ha−1 (N2), 105 kg N ha−1 (N3), 157.5 kg N ha−1 (N4), and 210 kg N ha−1 (N5). The N fertilizer used was urea (with a N content of 46%). The application of P was 105 kg ha−1 as superphosphate (with a P content of 16%). Before sowing, spreading times of both urea and superphosphate were 22 March and 25 March in 2024 and 2025, respectively. Fertilizers were evenly spread over the plot and incorporated into the 0–20 cm soil layer using a rotary tiller. Potassium (K) was not applied as the regional K content was sufficient to support crop growth.

The high-yielding, high-protein, and disease-resistant spring wheat variety “Dingxi 40”, widely cultivated locally, was selected as the test crop. It was sown on 22 March 2024 and 25 March 2025 at a seeding rate of 187.5 kg ha−1 (564 seeds per m2) with a row spacing of 20 cm. The wheat was harvested on 18 July 2024 and 27 July 2025, excluding 0.5 cm of the border rows. Tillage and soil preparation were carried out within one week after harvest. Weeds were manually controlled throughout the growing season, and a 10% glyphosate solution was sprayed as needed during the fallow phase post-harvest. Pest and disease populations were monitored and managed according to regional agricultural standards.

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

Plant samples were collected from 20 uniformly growing spring wheat plants in each plot at both anthesis and maturity. At anthesis, samples were separated into leaves, stems, and ears. At maturity, they were divided into leaves, stems, chaff, and grains. Root samples were taken from a depth of 0–60 cm using a root drill with an internal diameter of 10 cm. Two sampling points were selected in each sampling area: one located on the wheat growth line and the other between the wheat rows, ensuring sample integrity and representativeness. Each process was repeated three times. After being killed by heating in a 105 °C constant temperature oven for 30 min, the samples were dried at 70 °C for more than 48 h until completely dry. The dry matter (assimilate) was weighed and measured, and its N concentration was determined after being crushed and sieved (<2 mm).

During the physiological maturity stage of wheat, the 0.5 m marginal effect area around each experimental plot was removed, leaving the core experimental area. Manual cutting was performed at the base of the plants, 5 cm above ground level. The plants were bundled separately according to experimental units and tagged with serial numbers. After natural dehydration, a thresher (TF-550; Qingdao thresher factory, Qingdao, Shandong) was used to complete threshing, and the grain yield was accurately measured. Simultaneously, 20 representative individual plant samples were randomly selected from each plot to measure the effective ear number per unit area, grain weight per ear, and 1000-grain weight (TGW). The N concentration in various wheat organs was determined using a fully automatic carbon and N analyzer (VARIO MACRO CUBE CNS; Germany ELEMENTAR company, Langenselbold, Germany) [32].

The N accumulation amount is calculated by multiplying the assimilate accumulation amount by the N content. The following formulas are used for:

Pre-anthesis N transport in vegetative organs (NTV, kg ha−1) [33]:

Contribution of pre-anthesis N transport to grains (NTG, %) [33]:

Post-anthesis N accumulation in plants (NAP, kg ha−1) [33]:

Contribution rate of post-anthesis N accumulation to grains (NAG, %) [33]:

N absorption efficiency (NAE, kg kg−1) [34]:

N harvest index (NHI) [34]:

N use efficiency (NUE, kg kg−1) [34]:

N partial factor productivity (NPFP, kg kg−1) [34]:

N agronomic use efficiency (NAUE, kg kg−1) [34]:

Pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT, kg ha−1) [35]:

Contribution rate of pre-anthesis assimilate transport to grains (ATG, %) [35]:

Post-anthesis assimilate accumulation (PAA, kg ha−1) [35]:

Contribution rate of post-anthesis assimilate accumulation to grains (PAAG, %) [35]:

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA in SPSS (Version 27.0, Chicago, IL, USA) to determine significant differences between treatments and years. The Duncan Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was used to analyze treatment differences (p < 0.05). Pearson correlation analysis examined the relationships among assimilate accumulation, assimilate translocation, N accumulation, N translocation, and yield. Data visualization was performed using Origin 2021 to create biologically meaningful charts based on the analysis results.

3. Results

3.1. Assimilate Accumulation and Translocation

3.1.1. Assimilate Accumulation

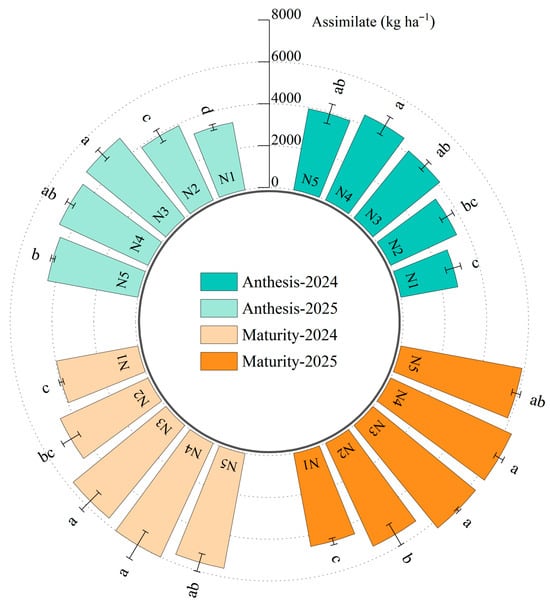

As wheat growth progressed, assimilate accumulation showed a significant upward trend (Figure 2). Over the two experimental years, the total assimilate accumulation followed the order: N4 ≈ N3 > N5 > N2 > N1. This indicates that as the N-fertilizer rate increased, assimilate accumulation initially rose and then declined. Specifically, in 2024, the N4 treatment resulted in the highest assimilate accumulation at anthesis (4755 kg·ha−1), showing significant increases of 57.9%, 26.1%, and 12.4% compared to the N1, N2, and N5 treatments, respectively. At maturity, the N4 treatment also recorded the highest accumulation (6254 kg·ha−1), with increases of 50.8%, 29.1%, and 10.3% compared to the N1, N2, and N5 treatments. In 2025, the N3 treatment achieved the highest assimilate accumulation at both anthesis (5141 kg·ha−1) and maturity (6585 kg·ha−1), with increases of 47.5% and 42.4%, respectively. The N5 treatment was significantly lower than N3 and N4 in both years.

Figure 2.

Accumulation of assimilates in 2024 and 2025 in wheat under varying N-fertilizer rates: N1 (0 kg N ha−1), N2 (52.5 kg N ha−1), N3 (105.0 kg N ha−1), N4 (157.5 kg N ha−1), and N5 (210.0 kg N ha−1). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between treatments within the same time frame (p < 0.05).

3.1.2. Assimilate Translocation

The pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT) initially increased and then decreased with the rise in N application rate (Table 2). On average, the AT for the N3 treatment peaked at 1150 kg·ha−1, which was significantly higher than that of the N1 and N2 treatments. No significant difference was observed between the N4 and N3 treatments, while the N5 significantly decreased. The trend in the contribution rate of pre-anthesis assimilate transport to grains (ATG) mirrored that of AT, with the highest ATG value of 46.8% for the N3 treatment in 2025, indicating that an appropriate N rate can enhance the transport ratio of pre-anthesis reserves to grain. The variance analysis results indicated that neither the effect of the years on these four parameters nor the interaction between treatments and years (T × Y) was significant.

Table 2.

Pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT, kg ha−1), contribution rate of pre-anthesis assimilate transport to grains (ATG, %), post-anthesis assimilate accumulation (PAA, kg ha−1), and contribution rate of post-anthesis assimilate accumulation to grains (PAAG, %) in wheat.

The post-anthesis assimilate accumulation (PAA) also showed significant differences among the treatments. However, when the N-fertilizer rate exceeded 105 kg N ha−1 (N3), PAA did not increase significantly. As the N-fertilizer rates increased, contribution rate of post-anthesis assimilate accumulation to grains (PAAG) showed a downward trend, indicating that high N treatments relied more on pre-anthesis storage, while low N rates depended more on post-anthesis photosynthetic product accumulation. The T × Y did not significantly affect these four parameters.

3.2. Nitrogen Accumulation and Translocation

3.2.1. Nitrogen Concentration

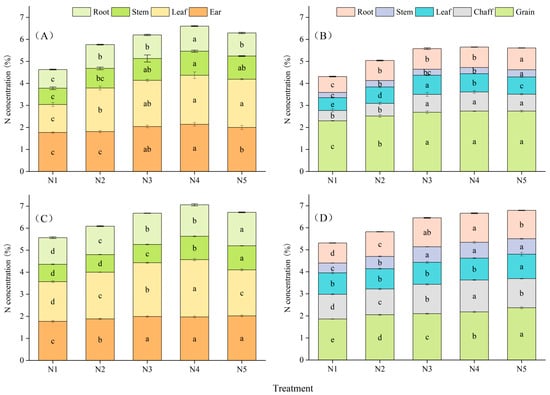

Different N-fertilizer rates significantly influenced the N concentration in various wheat plant organs at anthesis and maturity (Figure 3). Over the two growing seasons, the N concentration of the whole plant initially increased and then decreased at anthesis. Under the N4 treatment, the N concentration of the whole plant (1.71%) and leaves (2.42%) peaked, showing increases of 4.9–33.6% and 6.6–58.2%, respectively, compared to other treatments. The N concentration varied among different organs; in ears, it did not significantly increase beyond a N rate of 105 kg N ha−1 (N3). Under the N3 treatment, the N concentration in ears increased by 14.1% and 9.2% compared to the N1 and N2 treatments, respectively. N concentrations in stems and roots did not increase significantly beyond a N-fertilizer rate of 157.5 kg N ha−1 (N4). The N concentration in stems under the N4 treatment increased by 40.3%, 27.1%, and 18.7% compared to the N1, N2, and N3 treatments, respectively, while the N concentration in roots increased by 25.2%, 8.4%, and 4.0% compared to the N1, N2, and N3 treatments, respectively. In summary, excessive N application did not further enhance N accumulation in wheat organs at anthesis. Comparing the N concentration of organs at anthesis, ears and leaves had relatively high N concentrations, whereas stems and roots had relatively low N concentrations.

Figure 3.

N concentration at anthesis in 2024 (A) and 2025 (C), and at maturity in 2024 (B) and 2025 (D) in wheat. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between treatments within the same time frame (p < 0.05).

Throughout the two growing seasons, the N concentration in the entire plant at maturity exhibited an increasing trend with higher N application rates. However, when the N rate exceeded 157.5 kg N ha−1 (N4), this increase was not significant. Specifically, the N concentration in the entire plant under the N4 treatment was 28.1%, 12.8%, and 2.5% higher than under the N1, N2, and N3 treatments, respectively. At maturity, the N concentration in grains was the highest, followed by leaves, husks, and roots, with stems having the lowest concentration. The N concentration in leaves and roots did not increase significantly beyond a N-fertilizer rate of 105 kg N ha−1 (N3). Compared to the N1 and N2 treatments, the N3 treatment resulted in a 20.5% and 11.9% increase in leaf N concentration, respectively, and a 37.8% and 10.8% increase in root N concentration, respectively. Under the N4 treatment, the N concentration was 42.9%, 19.0%, and 2.0% higher than in the N1, N2, and N3 treatments, respectively. The highest N concentration in husks was observed under the N4 treatment, which increased by 8.4–45.0% compared to other treatments. Grain N concentration was highest under the N5 treatment, significantly increasing by 4.1–23.1% compared to other treatments.

Furthermore, the N concentration in 2025 was generally higher than in 2024, particularly in leaves and stems at maturity, which may be attributed to differences in annual weather or soil N background. Nevertheless, the trend among the treatments remained consistent. In most organs, the N1 and N2 treatments had significantly lower N concentrations compared to medium and high N treatments, while there was no significant difference among the N3, N4, and N5 treatments in some organs.

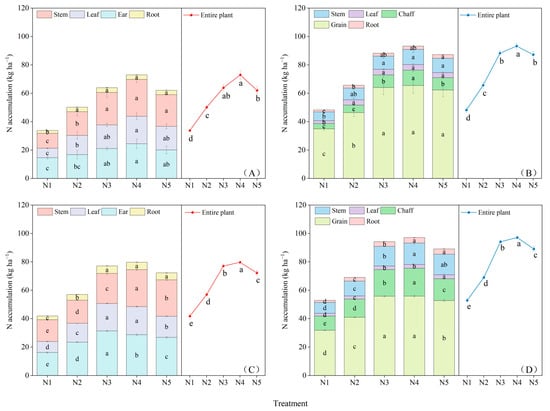

3.2.2. Nitrogen Accumulation

N-fertilizer rates significantly influenced N accumulation in the whole plant and various organs (Figure 4). As N-fertilizer rates increased, N accumulation in wheat organs followed an upward trend, with variations among different organs. Comparing N accumulation in various organs at anthesis across two growing seasons revealed that total N accumulation in the whole plant initially increased and then decreased. Under the N4 treatment, total N accumulation reached its highest at 76.3 kg ha−1, showing a significant increase of 8.2% to 101.9% compared to other treatments. N accumulation in individual organs showed that the stem and ear were the primary N distribution sites, followed by the leaves, with the root having the lowest N accumulation. When N-fertilizer rates were increased to 105 kg N ha−1 (N3), N accumulation in leaves, roots, and ears peaked at anthesis, surpassing N1 by 105.66%, 82.96%, and 70.03%, respectively. Under the N4 treatment, N accumulation in stems significantly increased by 101.74% compared to N1. Notably, there was no significant difference in N accumulation between the N3 and N4 treatments.

Figure 4.

N accumulation at anthesis in 2024 (A) and in 2025 (C) and at maturity in 2024 (B) and in 2025 (D). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between treatments within the same time frame (p < 0.05).

At maturity across the two growing seasons, N accumulation in the entire plant initially increased, followed by a decline. Under N4 treatment, N accumulation significantly increased by 4.34% to 88.17%. Further analysis revealed significant changes in N distribution among various organs. The grain became the main sink organ, followed by the stem and chaff, while N accumulation in leaves and roots was the least. When N-fertilizer rates were increased to the 105 kg ha−1, N accumulation in the stem and grain significantly increased by 67.12% and 79.82%, respectively, compared to N1. Under the N4 treatment, N accumulation in chaff and root significantly increased by 120.44% and 115.75%, respectively, compared to N1. While N accumulation in leaves only showed significant differences between fertilized and unfertilized treatments. These results indicate that high N treatment promotes temporary N storage in non-grain organs. In vegetative organs, N accumulation in leaves tended to stabilize under N3 and higher treatments, and a similar trend was observed in stems and roots. In 2025, N accumulation was generally higher than in 2024, particularly in stems and roots at anthesis. Nevertheless, the sorting trends among treatments were largely consistent. In most organs, N1 and N2 treatments were significantly lower than medium and high N treatments, while N3, N4, and N5 treatments showed no significant difference in some organs.

3.2.3. Nitrogen Translocation and Its Contribution to Grain Yield

Pre-anthesis N transport in vegetative organs (NTV) also exhibited an initial increase, followed by a decrease with the rise in N application rate (Table 3). The two-year average data indicated that the N treatment N4 yielded the highest net production value (41.8 kg·ha−1), showing significant enhancements of 102.9%, 39.8%, and 14.8% compared to treatments N1, N2, and N5, respectively, while no significant difference was observed in relation to treatment N3. Significant differences were also noted in the contribution rate of pre-anthesis N transport to grains (NTG) among various treatments. The NTG for the N2, N3, and N4 treatments was higher, with increases of 10.8%, 6.1%, and 11.3% compared to the N1 treatment, respectively. Additionally, the year (Y) significantly affected these four parameters. The T × Y significantly impacted the NTG and NAG.

Table 3.

Pre-anthesis N transport in vegetative organs (NTV, kg ha−1), contribution rate of pre-anthesis N transport to grains (NTG, %), post-anthesis N accumulation in plants (NAP, kg ha−1), and contribution rate of post-anthesis N accumulation to grains (NAG, %) in wheat.

Post-anthesis N accumulation in plants (NAP) did not significantly increase when the N-fertilizer rate exceeded 105 kg N ha−1 (N3), which was 61.7% and 51.1% higher than the N1 and N2 treatments, respectively. Conversely, the contribution rate of post-anthesis N accumulation to grains (NAG) decreased with higher N-fertilizer rates. The NAG for the N1 treatment was the highest (38.1%), whereas the NAG for the N2 and N4 treatments was the lowest (approximately 31%). The T × Y did not significantly affect these four parameters.

3.3. Yield and N-Use Efficiency

3.3.1. Yield and Its Components

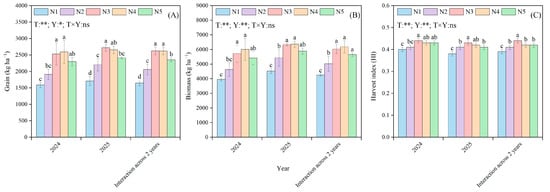

N-fertilizer rates had a significant impact on wheat grain yield, biomass production, and harvest index (HI) (Figure 5). In 2024, the N3 and N4 treatments demonstrated significantly elevated grain yields compared to other treatments, with increases of 59.4% and 63.2%, respectively, relative to the N1 treatment. In 2025, the N3 treatment achieved the peak grain yield of 2720 kg ha−1, representing a 59.2% increase over the N1 treatment. On average, the N3 and N4 treatments produced grain yields that were 59.3% and 59.1% higher, respectively, than the N1 treatment.

Figure 5.

Wheat grain yield in 2024, 2025, and average (A), biomass yield in 2024, 2025, and average (B), and harvest index (HI) in 2024, 2025, and average index (C). At each level, interactions (Y × T), year, or treatment denoted by different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to the Duncan Multiple Range Test. “ns” represents non-significance at p > 0.05, while “*” and “**” indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively, as determined by ANOVA. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between treatments within the same time frame (p < 0.05).

The N4 treatment had the highest biomass yield in 2024 at 6002 kg ha−1, while the N3 treatment had the highest yield in 2025 at 6336 kg ha−1. The two-year average biomass yield of the N4 treatment was the highest at 6184 kg ha−1, 45.7% higher than that of the N1 treatment. Both the N3 and N4 treatments showed significantly higher biomass and grain yields compared to the N1 and N2 treatments, with no significant differences observed between N3 and N4 for either grain or biomass yield. The HI for the N3 treatment was the highest (0.44 in 2024 and 0.43 in 2025), with the two-year average being 12.8% higher than that of the N1 treatment. Additionally, the year (Y) significantly affected these three parameters, while the interaction between treatment and year (T × Y) did not.

Further analysis revealed that N-fertilizer rates significantly affected the grain number per ear (GNS) and TGW but had no significant effect on the number of ears (Table 4). The GNS increased significantly with higher N application rates in both years. In 2024, the N3 and N4 treatments exhibited the highest GNS, with increases of 84.2% and 76.0% compared to N1. In 2025, the GNS in the N3 and N4 treatments remained the highest, showing increases of 83.2% and 75.2% over the N1 treatment. The average GNS in the N3 treatment was the highest overall (30.6), representing an 83.2% increase compared to the N1 treatment. Concerning TGW, the N2, N3, N4, and N5 treatments showed significantly higher weights than the N1 treatment, with average increases of 5.8%, 8.3%, 9.6%, and 9.3% over two years, respectively. However, no significant differences were observed among the N2, N3, N4 and N5 treatments. Additionally, the year (Y) significantly affected the ear number and GNS. The T × Y significantly impacted the GNS.

Table 4.

Grain agronomic traits of wheat as affected by N-fertilizer rate.

3.3.2. Nitrogen-Use Efficiency

N-fertilizer rates significantly impacted all N efficiency indices (Table 5). N absorption efficiency (NAE) decreased significantly with increasing N application rates across two growing seasons. With a 52.5 kg ha−1 increase in N application, NAE gradually decreased by 32.3% (N1), 53.2% (N4), and 67.7% (N5). The N harvest index (NHI) did not significantly differ across N treatments, but it was generally lower in 2025 than in 2024. N use efficiency (NUE) decreased as N application rates increased, with the N5 treatment showing a 12.3% reduction compared to the N2 treatment. The N partial factor productivity (NPFP) followed a pattern similar to NAE, decreasing by 36.2% (N3), 57.4% (N4), and 71.4% (N5) with a 52.5 kg ha−1 increase in N application. The N agronomic use efficiency (NAUE) in the N3 treatment was the highest (average 9.31 kg kg−1), significantly surpassing that in the N4 and N5 treatments, suggesting that a moderate increase in N (N3) can maintain high agronomic efficiency at a higher yield. The T × Y did not significantly affect these five parameters.

Table 5.

N absorption efficiency (NAE, kg kg−1), N harvest index (NHI), N use efficiency (NUE, kg kg−1), N partial factor productivity (NPFP, kg kg−1), and N agronomic use efficiency (NAUE, kg kg−1).

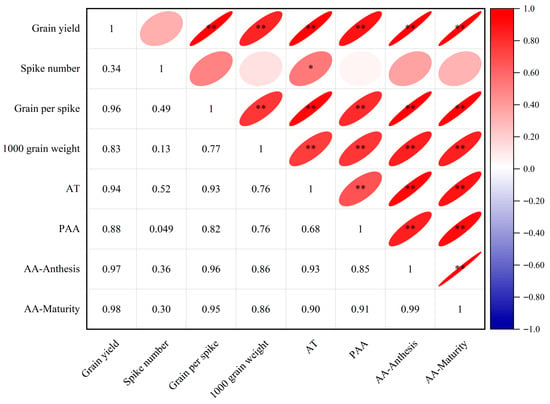

3.4. Relationship Between Assimilate, N, and Grain Yield

The results showed a significant positive correlation between grain yield and both the GNS (r = 0.956, p < 0.01) and the TGW (r = 0.828, p < 0.01), while no significant correlation was observed with the number of ears (r = 0.339) (Figure 6). In terms of assimilate accumulation and distribution, grain yield showed a significantly strong positive correlation with several factors: pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT) (r = 0.941, p < 0.01), PAA (r = 0.881, p < 0.01), assimilate accumulation at anthesis (AA-Anthesis) (r = 0.973, p < 0.01), and assimilate accumulation at maturity (AA-Maturity) (r = 0.978, p < 0.01). Further analysis revealed that the GNS was significantly positively correlated with AT (r = 0.93, p < 0.01) and AA-Anthesis (r = 0.958, p < 0.01). The TGW was significantly positively correlated with PAA (r = 0.761, p < 0.01) and AA-Maturity (r = 0.859, p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

Relationship between assimilate accumulation at anthesis (AA-Anthesis, kg ha−1) and at maturity (AA-Maturity, kg ha−1), pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT, kg ha−1), post-anthesis assimilate accumulation (PAA, kg ha−1), and wheat yield; “**”and “*” indicate significance (p < 0.01) (p < 0.05). The size of the ellipse is inversely correlated with the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. The flatter and smaller the ellipse, the closer the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is to 1, indicating a stronger correlation between the two variables, and vice versa.

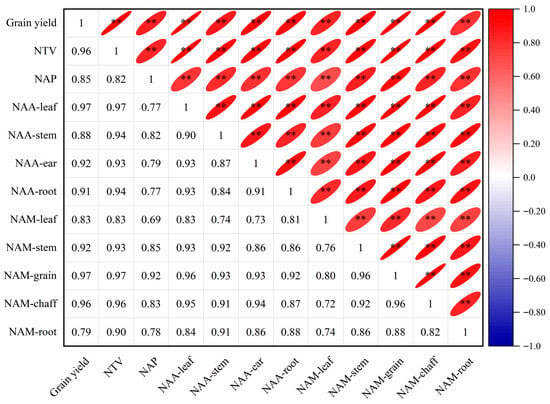

Grain yield was significantly positively correlated with all N accumulation and transport indicators (p < 0.01) (Figure 7). Notably, the highest correlation was observed between grain yield and N accumulation at anthesis in leaves (NAA-Leaf) (r = 0.974) and maturity in grains (NAM-Grain) (r = 0.973). Pre-anthesis N transport (NTV) was significantly correlated with grain yield (r = 0.960) and N accumulation in organs (leaves, stems, ears, and roots) at anthesis (r > 0.928). Post-anthesis N accumulation (NAP) was also significantly correlated with grain yield (r = 0.847) and grain N accumulation at maturity (NAM-Grain) (r = 0.917). Among the different organs, N accumulation in leaves (r = 0.974) and ears (r = 0.922) at anthesis was most significantly positively correlated with grain yield, while N accumulation in stems (r = 0.925) and glumes (r = 0.963) at maturity was also significantly positively correlated with grain yield.

Figure 7.

Relationship between N accumulation at anthesis in leaf (NAA-leaf), stem (NAA-stem), ear (NAA-ear) and root (NAA-root), and at maturity in grain (NAM-grain), stem (NAM-stem), chaff (NAM-chaff), leaf (NAM-leaf), and root (NAM-root), pre-anthesis N transport (NTV, kg ha−1), post-anthesis N accumulation (NAP, kg ha−1), and wheat grain yield; “**” indicates significance (p < 0.01). The size of the ellipse is inversely correlated with the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. The flatter and smaller the ellipse, the closer the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is to 1, indicating a stronger correlation between the two variables, and vice versa.

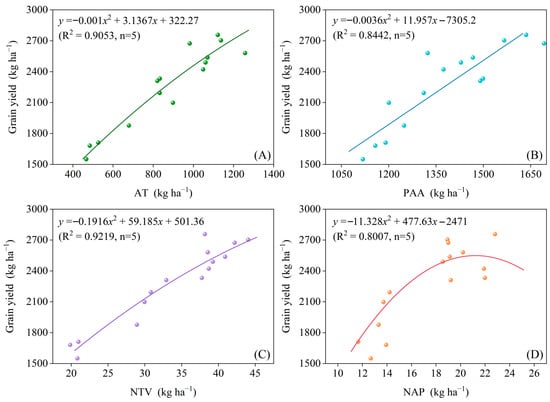

With the increase in production, AT showed an increasing trend, ranging from 63.11% to 133.51% (Figure 8A). However, when the yield decreased to 2355.09 kg ha−1, it decreased by 21.67% compared with the N3 treatment. according to the fitting equation, when it reached 1568 kg ha−1, the grain yield peaked at 2781.99 kg ha−1. Compared with the actual yield data, the grain yield of the N3 treatment (2625 ± 117 kg ha−1) was close to the peak yield.

Figure 8.

Relationship between pre-anthesis assimilate transport (AT) and grain yield (A), post-anthesis assimilate accumulation (PAA) and grain yield (B), pre-anthesis N transport in vegetative organs (NTV) and grain yield (C), post-anthesis N accumulation in plants (NAP) and grain yield (D); The dots represent the grain yield under various variable, while the lines depict the fitted equation curve.

With the increase in production, PAA showed an increasing trend, ranging from 8.50% to 35.24% (Figure 8B). However, under medium and high N rates (N3–N5), the change in PAA was not significant, indicating that assimilates after anthesis also played an important role in supporting grain development, but reached the threshold range under high N rates. According to the fitting equation, when assimilate accumulation after anthesis reached 1660.69 kg ha−1, the grain yield peaked at 2623.26 kg ha−1. Compared with the field measurement results, under N3 and N4 treatments, assimilate transport after anthesis reached a high level, and grain yield also peaked.

With the increase in production, NTV showed an increasing trend, ranging from 45.42% to 103.41% (Figure 8C). However, at the N5, the yield of NTV decreased by 12.85% compared with the N4, indicating that NTV also had a corresponding increase in high-yield fields, but excessively high N RATEs would reduce the absorption and transport of N post-anthesis. According to the fitting equation, when NTV reached 154.45 kg ha−1, the grain yield would peak at 5071.90 kg ha−1. Compared with the actual measured data, there is still a large room for improvement in N accumulation pre-anthesis, and improving N accumulation pre-anthesis is crucial for enhancing grain yield in this area.

With the increase in production, NAP showed an increasing trend, ranging from 7.77% to 62.31% (Figure 8D). However, under medium and high N rates (N3, N4, and N5), the change in NAP was not significant, indicating that under medium and high N rates, N transport after anthesis has reached the threshold range. According to the fitting equation, when N transport after anthesis reached 21.08 kg ha−1, grain yield peaked at 2563.66 kg ha−1. Compared with the actual measured data, grain yield has reached the peak at the N3.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Nitrogen in Coordinating Reserve Mobilization and Post-Anthesis Assimilation for High Wheat Yield

Crop assimilate accumulation is closely linked to yield formation [36]. Within certain limits, increasing assimilate accumulation can enhance crop yield and the HI [37]. Similar results were obtained in the study that assimilates accumulation at anthesis and maturity exhibited a quadratic response to increased N application rate, with N3 and N4 treatments producing the highest biomass. This non-linear response aligns with the classic concept of diminishing returns in crop physiology. When the optimal N-fertilizer rate is exceeded, additional N input cannot increase the proportion of biomass [38,39]. Under N5 treatment, the accumulation of assimilates decreased significantly, highlighting the low efficiency of excessive N application. This reduction may be attributed to the “green greed” of vegetative growth induced by high N rates, which led the plant to preferentially allocate assimilates to the growing stems and leaves [40]. Consequently, this competitive allocation weakened the nutrient supply to economically important organs such as ears and grains [41,42].

The process of wheat yield formation fundamentally involves the production, translocation, and assimilation of photosynthate [43]. Our results revealed a significant shift in the distribution of assimilates before and after anthesis under different N application conditions. In the N3 treatment, the transportation of assimilates pre-anthesis and the ATG reached the highest level, indicating that appropriate N application optimized the reuse of storage reserves for grain development [42]. This finding is consistent with the discovery that N enhances the activity of carbohydrate hydrolase and promotes the decomposition of temporary storage compounds in the stem, thereby improving the mobilization of assimilates to the sink [44]. Conversely, under high-N rates (N4–N5), the PAAG decreased, indicating a strategic change in plant resource allocation. Under sufficient N supply, wheat plants were more dependent on pre-anthesis storage, while N-deficient plants (N1–N2) relied more on photosynthesis during the grain-filling stage. The compensation mechanism between assimilate sources before and after anthesis has also been observed in other cereals, where N-mediated source-sink regulation helps maintain yield stability under different nutritional conditions [45]. Among the ATG and PAAG indexes, the superior performance of the N3 treatment showed that it achieved the best balance between reserve mobilization and continuous photosynthesis. This balance is essential to minimize the risks associated with source or reservoir constraints during the critical grain-filling stage [42].

4.2. Nitrogen Application Regulates Source-Sink Relationships by Orchestrating Pre-Anthesis Nitrogen Translocation and Remobilization in Wheat

The coordinated regulation of N accumulation, distribution, and translocation in wheat is essential for enhancing crop yield, with a primary focus on the “source-sink” balance of N distribution. Applying an appropriate N-fertilizer rate can increase N accumulation in crop nutrient organs and grains, thereby facilitating N transfer to the grains [37,46,47]. As the N rate increased from N1 to N4, there was a significant increase in N concentration and accumulation across the entire wheat plant, including leaves, stems, roots, and grains at both anthesis and maturity (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This finding aligns with previous studies, indicating that N supply is the primary factor driving N assimilation and accumulation in plants [48]. Particularly in vegetative organs, this increase in N content reflects the plant’s strong N capture and storage capacity during the vegetative growth stage, providing an essential N pool for grain filling after anthesis [49]. However, when the N rate reached N5, the N concentration in some organs, such as the stem at anthesis in 2024, decreased or stagnated. This phenomenon is typically caused by excessive N metabolism, which competitively consumes the carbon skeletons needed for synthesizing structural substances during the process of N-induced “green lust” [40,50]. If the N concentration in the stem does not increase simultaneously to enhance its mechanical toughness, and assimilates are relatively insufficient, this will result in stem wall thinning, internode elongation, and a significant decline in mechanical strength. Consequently, the risk of lodging and disease infection in the later stages will greatly increase, ultimately threatening yield [51]. This observation aligns with the conclusion of yield decline found in this study (Figure 5).

Efficient N transport from vegetative organs to grains is crucial for determining grain yield and protein [52]. In this study, the NTV of vegetative organs pre-anthesis significantly increased with higher N application rates (Table 3). This indicates that higher N fertilizer rates promoted N content in leaves and stems pre-anthesis, thereby providing a more sufficient substrate for post-anthesis transport. This finding aligns with Madhan et al. [53], who state that improving N status pre-anthesis can enhance the N sink intensity of vegetative organs, thereby improving transport potential [54].

Interestingly, although NTV increased with higher N rates, the NTG peaked in the N2 and N4 treatments (68.6% and 68.9% on average), while the NAG decreased after anthesis. This indicates that, under optimal N-fertilizer rates, grain N relies more on the mobilization of pre-anthesis reserves than on direct absorption from the soil after anthesis. This strategy is crucial when soil N supply may be limited during grain filling to ensure yield [55]. Under the N5 treatment, NTG decreased, while NAP and NAG increased, suggesting that excessive N application may delay plant senescence and the N transport process, resulting in an increased relative contribution of post-anthesis absorption. However, this did not significantly benefit grain N accumulation and may have an adverse impact on yield due to late ripening [56].

This study demonstrated that T and Y significantly affected NTV, NTG, NAP, and NAG, with a significant T × Y interaction effect on NTG and NAG (Table 3). The results indicated that the impact of different N treatments on N transport and distribution in wheat is regulated by annual environmental conditions. The underlying mechanism may be linked to variations in weather factors, soil N supply capacity, and plant physiological responses across different years [52,57]. Consequently, a fixed recommended N application rate may not be optimal. Future efforts should focus on precision agriculture strategies based on soil N testing and plant N nutrition diagnosis to achieve the synergy of high yield, high efficiency, and environmental protection [58].

4.3. How Optimal Nitrogen Rates Enhance Both Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Improving Internal Nitrogen Allocation

The results demonstrated that grain yield exhibited a secondary response to N application and did not show a significant T × Y interaction (Figure 5). This indicated that within the range of N-fertilizer rates set in this study, the yield performance order of different treatments was highly consistent across different years. For example, the N3 and N4 treatments showed the highest yields in both experimental years. This stability has important agronomic significance, indicating that there is a relatively robust N fertilizer optimization interval (N3–N4 in this study) within a certain range of environmental variation. Fertilization within this range can achieve predictable and efficient yield returns and reduce the production risk caused by uncertain conditions [38,59]. The excellent performance of the N3 and N4 treatments can be attributed to their optimal effects on yield components, particularly the GNS and the TGW. There was a significant positive correlation between grain yield and GNS (r = 0.956), indicating that yield components play a key role in determining final productivity. This finding supports previous studies that N application at key growth stages can enhance floret initiation and survival, thereby increasing the GNS [60]. Similarly, the significant correlation between yield and TGW (r = 0.828) emphasized the importance of N in supporting grain filling, which may be achieved by improving the supply of assimilates and prolonging the function of flag leaves [61]. Grain yield showed a significant correlation with assimilate (r = 0.973–0.978) and N accumulation (r = 0.970–0.974) at critical growth stages, revealing the comprehensive nature of carbon and N metabolism during yield formation. Our results indicate that the N3 treatment achieves the best balance between pre-anthesis reserve mobilization and post-anthesis assimilation, which is essential for maximizing grain yield [62]. The differential effects of N rate on yield components provide valuable insights into the source-sink relationship. Although the ear number was not significantly affected by N rates, their effect on GNS and grain yield was substantial, indicating that sink capacity rather than source availability was the main limiting factor in this system [63]. The significant T × Y interaction indicates that the effect of N-fertilizer rate on GNS is highly dependent on weather conditions. Under favorable conditions, N promotes panicle differentiation and reduces floret abortion, thereby increasing grain number. This model contrasts with N-limiting environments, where N source capacity generally limits yield [64].

Under N3 treatment, although the NAE was moderate, the higher NUE indicated that the optimal N-fertilizer rate promoted more effective internal N utilization rather than merely maximizing N absorption. This finding aligns with research suggesting that moderate N application enhances the transfer of N from vegetative organs to growing grains [65]. At higher rates of N application (N4–N5), the decline in most N efficiency parameters demonstrated that when N supply exceeded plant demand, the capacity for N utilization was physiologically restricted [66]. Under optimal N rates (N3–N4), the higher NHI indicated improved N distribution to grains, which is crucial for productivity and grain quality. At moderate N rates, this efficient N transfer from vegetative organs to grains is associated with better coordination between N metabolism and carbon assimilation [67]. Our results reinforce the concept of precise N management. A moderate application rate can achieve high yields and improve N use efficiency simultaneously [66]. This approach is particularly important in the context of sustainable intensification, as the goal is to maximize productivity while minimizing environmental impact [68].

5. Conclusions

The results indicated that a moderate N application rate significantly enhances the translocation of assimilates and N to the grains, leading to improved yield and NUE. The primary effect of N fertilizer on yield is achieved by facilitating the translocation of pre-anthesis assimilates and N, which is a key “source” process. This optimized translocation was closely linked to the establishment of a stronger “sink,” as evidenced by a significant increase in GNS. A moderate N rate strategy, centered around 105 kg ha−1, effectively coordinated the “source-sink” relationship. This strategy ensured an adequate supply of “sources” to fill the established “sinks,” thereby maximizing productivity by improving NUE. It provided a specific and sustainable N management practice for wheat production in similar semi-arid regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.X.; data curation, X.W. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, A.X. and L.L.; funding acquisition, A.X.; investigation, N.L. and P.L.; methodology, A.X. and L.L.; project administration, A.X. and Y.C.; resources, L.L.; supervision, L.L.; writing—original draft, Y.C. and A.X.; writing—review and editing, K.S.K. and Z.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Gansu Agricultural University—Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project for Public Recruitment (GAU-KYQD-2021-17), the Research and Application Project on Key Technologies for Fully Biodegradable Mulching Films in Gansu Province 2025 (QDHY-BM-2024), the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Gansu Agricultural University—Youth Tutor Support Fund (GAU-QDFC-2024-08), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160525 and 32460550), Gansu Provincial Department of Education—Outstanding Graduate Student “Innovation Star” (2025CXZX-756).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Navarro, B.B.; Machado, M.J.; Figueira, A. Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Agriculture: Integrating Biotechnology, Microbiology, and Novel Delivery Systems for Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 2974–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Guo, L.; Lin, E.; Han, X. Effects of different nitrogen fertilizer management practices on wheat yields and N2O emissions from wheat fields in North China. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yan, J. Sustainable agriculture in the era of omics: Knowledge-driven crop breeding. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Arenas, R.; Dhakal, S.; Ullah, H.; Agarwal, A.; Datta, A. Seeding, nitrogen and irrigation management optimize rice water and nitrogen use efficiency. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2021, 120, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Peng, M.; Ru, S.; Hou, Z.; Li, J. A suitable organic fertilizer substitution ratio could improve maize yield and soil fertility with low pollution risk. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 988663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Effah, Z.; Li, L.; Xie, J.; Liu, C.; Anwar, S. Does Nitrogen Fertilization Improve Nitrogen-Use Efficiency in Spring Wheat? Agronomy 2024, 14, 2049–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, S.N.; Fathima, P.S.; Yogananda, S.B.; Suma, R.; Shivakumar, K.V.; Sowmyalatha, B.S.; Gowda, P.T.; Halli, H.M.; Sannagoudar, M.S.; Senthamil, E. Trade-offs between global warming potential, eco-efficiency and water use efficiency under different establishment methods and nitrogen management strategies for sustainable rice production. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1004, 180759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Yuan, L. Spatial divergence of nitrogen fate in China’s wheat systems: A meta-analysis and machine-learning roadmap for region-specific management. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 22, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Ying, F.; Zhu, M.; Fan, Z.; Lakshmanan, P.; Zhang, F.; Cong, W.F. Subsurface fertilization geometry synergies enhanced grain yield, nitrogen use efficiency and reduced greenhouse gas emissions: A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2026, 336, 110203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Jia, Z.; Mo, F. Reducing nitrogen application through deep placement to optimize the nitrogen balance in a dryland maize cropping system. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 528, 146712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaju, O.; Allard, V.; Martre, P.; Le Gouis, J.; Moreau, D.; Bogard, M.; Hubbart, S.; Foulkes, M.J. Nitrogen partitioning and remobilization in relation to leaf senescence, grain yield and grain nitrogen concentration in wheat cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2014, 155, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ata-Ul-Karim, S.T.; Lemaire, G.; Duan, A.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Qin, A.; Ning, D.; Liu, Z. Exploring the nitrogen source-sink ratio to quantify ear nitrogen accumulation in maize and wheat using critical nitrogen dilution curve. Field Crops Res. 2021, 274, 108332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.; Saleem, M.F.; Anwar, A.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, B.; Shahid, M.; Hashem, A.; Kumar, A.; Abd-Allah, E.F. Exogenous Zinc Alleviates Post-Anthesis Heat Stress by Improving the Defense Mechanism and Leaf Physiology of Bread Wheat. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 6029–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakbazan, M.; Liu, K.; Entz, M.H.; Chau, H.W.; Kubota, H.; Tidemann, B.D.; Peng, G.; Lokuruge, P. Comparing economics and nitrogen fertilizer costs between diversified and intensified cropping systems in western Canada. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2025, 105, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Khan, K.S.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Effah, Z.; Li, L. Fertilizer nitrogen use efficiency and its fate in the spring wheat-soil system under varying N-fertilizer rates: A two-year field study using 15N tracer. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 252, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Noor, F.; Liang, L.T.; Ding, P.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Nitrogen fertilization and precipitation affected Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in dryland the Loess Plateau of South Shanxi, China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Xie, Y.; Hu, L.; Feng, B.; Li, S. Remobilization of vegetative nitrogen to developing grain in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Field Crops Res. 2016, 196, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ali, M.F.; Ye, Y.; Huang, X.; Peng, Z.; Naseer, M.A.; Wang, R.; Wang, D. Irrigation and Nitrogen Management Determine Dry Matter Accumulation and Yield of Winter Wheat Under Dryland Conditions. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210, e12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tian, Z.; Qi, Z.; Han, J.; Zhao, X.; Xue, J. Effect of N-fertilizer rate on Grain Yield, Dry Matter and Nitrogen Accumulation and Remobilization in a Winter Wheat-Fresh Maize Cropping System. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 11, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Deng, X.P.; Eneji, A.E.; Wang, L.L.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.J. Dry-Matter Partitioning across Parts of the Wheat Internode during the Grain Filling Period as Influenced by Fertilizer and Tillage Treatments. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2014, 45, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, A.; Abad, H.H.; Sarvestani, Z.T.; Moafpourian, G.H.; Band, A.A. Remobilization of dry matter in wheat: Effects of nitrogen application and post-anthesis water deficit during grain filling. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2011, 39, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Serret, M.D.; Pie, J.B.; Shah, S.S.; Li, Z. Relative Contribution of Nitrogen Absorption, Remobilization, and Partitioning to the Ear During Grain Filling in Chinese Winter Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Shao, Y.; He, L.; Li, X.; Hou, G.; Li, S.; Feng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y. Optimizing nitrogen management to achieve high yield, high nitrogen efficiency and low nitrogen emission in winter wheat. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y.; Yan, S.; Wu, Y. Maize yield, rainwater and nitrogen use efficiency as affected by maize genotypes and nitrogen rates on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, L.; Tang, L.; Cao, W.; Zhu, Y. Effects of water-nitrogen interactions on the fate of nitrogen fertilizer in a wheat-soil system. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 136, 126507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.S.; Cui, Z.L.; Zhang, W.F. Managing nutrient for both food security and environmental sustainability in China: An experiment for the world. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2014, 1, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, S.S.; Soon, Y.K.; Grant, C.A.; Lemke, R.; Lupwayi, N. Influence of controlled-release urea on seed yield and N concentration, and N use efficiency of small grain crops grown on Dark Gray Luvisols. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2010, 90, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Kaur, G.; Asthir, B. Biochemical aspects of nitrogen use efficiency: An overview. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, R.; Gao, W.; You, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Kamran, M.; Yang, X. Optimizing the N-fertilizer rate and planting density to improve dry matter yield, water productivity and N-use efficiency of forage maize in a rainfed region. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food and Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.D. Analysis of Soil Agro-Chemistry; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Schierenbeck, M.; Fleitas, M.C.; Cortese, F.; Golik, S.I.; Simón, M.R. Nitrogen accumulation in grains, remobilization and post-anthesis uptake under tan spot and leaf rust infections on wheat. Field Crops Res. 2019, 235, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Xie, C.; Yu, J.; Bai, W.; Pei, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Fan, J.; Yin, F. Effects of irrigation and nitrogen levels on yield and water-nitrogen-radiation use efficiency of drip-fertigated cotton in south Xinjiang of China. Field Crops Res. 2024, 308, 109280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Han, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, W.; Han, W.; Liu, B.; Bai, W. Effect of chemical regulators on the recovery of leaf physiology, dry matter accumulation and translocation, and yield-related characteristics in winter wheat following dry-hot wind. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, L.; Siosemar deh, A.; Sohrabi, Y.; Bahramnejad, B.; Hosseinpanahi, F. Dry matter remobilization and associated traits, grain yield stability, N utilization, and grain protein concentration in wheat cultivars under supplemental irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 263, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Q.; Zou, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Pursuing sustainable high-yield winter wheat via preanthesis dry matter and nitrogen accumulation by optimizing nitrogen management. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Rufty, T.W. Nitrogen and water resources commonly limit crop yield increases, not necessarily plant genetics. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Han, R.F.; Lin, X.; Wang, D. Controlled-release nitrogen combined with ordinary nitrogen fertilizer improved nitrogen uptake and productivity of winter wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1504083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Liao, F.; Verma, K.K.; Sarwar, M.A.; Mahmood, A.; Chen, Z.L.; Li, Q.; Zeng, X.P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.R. Fate of nitrogen in agriculture and environment: Agronomic, eco-physiological and molecular approaches to improve nitrogen use efficiency. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzei, J. Nitrogen rate applied affects dry matter translocation and performance attributes of wheat under deficit irrigation. J. Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Hussain, S.; Yang, L.; Gao, S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Ren, X. Reduced nitrogen rate improves post-anthesis assimilate to grain and ameliorates grain-filling characteristics of winter wheat in dry land. Plant Soil 2024, 499, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaju, O.; Allard, V.; Martre, P.; Snape, J.W.; Heumez, E.; LeGouis, J.; Moreau, D.; Bogard, M.; Griffiths, S.; Orford, S.; et al. Identification of traits to improve the nitrogen-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Field Crops Res. 2011, 123, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wu, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Guo, J.; Zheng, J.; Wu, L. Optimization of drip irrigation and fertilization regimes to enhance winter wheat grain yield by improving post-anthesis dry matter accumulation and translocation in northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 271, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Jiang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, R. Effect of nitrogen reduction on the remobilization of post-anthesis assimilate to grain and grain-filling characteristics in a drip-irrigated spring wheat system. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, T.; Foulkes, M.J.; Orford, S.; Singh, A.M.; Wingen, L.U.; Karnam, V.; Nair, L.S.; Mandal, P.K.; Griffiths, S.; et al. Nitrogen uptake and remobilization from pre- and post-anthesis stages contribute towards grain yield and grain protein concentration in wheat grown in limited nitrogen conditions. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2023, 4, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, R.; Yang, H.; Zheng, T.; Huang, X.; Fan, G. The Impacts of Nitrogen Accumulation, Translocation, and Photosynthesis on Simultaneous Improvements in the Grain Yield and Gluten Quality of Dryland Wheat. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1283–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Quan, X.Q.; Li, X.Y.; Cheng, C.; Yu, J.X.; Tang, X.H.; Wu, P.F.; Ma, X.Q.; Yan, X.L. Integrated morphological and physiological plasticity of root for improved seedling growth in Cunninghamia lanceolata and Schima superba under nitrogen deficiency and different NH4+-N to NO3−-N ratio. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1673572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.S.; Nawaz, F.; Shehzad, M.A. Contributions of nitrogen metabolic enzymes in storage protein assimilation and mineral accumulation regulated by nitrogen and selenium in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Q.; Song, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. N addition rebalances the carbon and nitrogen metabolisms of Leymus chinensis through leaf N investment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 185, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Nitrogen regulates stem lodging resistance by breaking the balance of photosynthetic carbon allocation in wheat. Field Crops Res. 2023, 296, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Dai, D.; Cao, Y.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, M.; Ding, J.; Li, C.; Guo, W.; Zhou, G.; et al. Optimal N management affects the fate of urea-15N and improves N uptake and utilization of wheat in different rotation systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1438215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhan, K.; Velu, G.; Subramanian, M.; Pandian, K.; Arunachalam, L.; Golla, G.; Ganeshan, S.; Rajasekaran, R.; Nallusamy, S.; Mustaffa, M.R.A.F. 15N-isotope tracing reveals enhanced nitrogen uptake, assimilation and physiological response from Nano urea in maize. NanoImpact 2025, 40, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soofizada, Q.; Pescatore, A.; Orlandini, S.; Napoli, M. A multidimensional analytical framework for the selection of soft wheat varieties for dryland environments based on agronomic productivity, stability, nitrogen use efficiency and economic parameters. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 171, 127786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Fan, M.; Vitousek, P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Producing more grain with lower environmental costs. Nature 2014, 514, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, K. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on dry matter accumulation and yield in wheat/maize/soybean intercropping systems. Acta Pratacult. Sin. 2014, 23, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Tang, Y.; Mo, F.; Nangia, V.; Liu, Y. Responses of wheat nitrogen uptake and utilization, rhizosphere bacterial composition and nitrogen-cycling functional genes to nitrogen application rate, planting density and their interactions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 193, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Karakas, E.; Fernie, A.R. Adjustments of plant primary metabolism in the face of climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 4804–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, J.; Gaba, S.; Gautier, J.L.; Leluc, A.; Bretagnolle, V. Economic viability of reduced agricultural inputs in farmer-co-designed large-scale experimental trials in western France. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yan, J. Contribution of green organs to grain weight in dryland wheat from the 1940s to the 2010s in Shaanxi Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3377–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ding, Y.; Li, F.; Wu, P.; Zhu, M.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Guo, W. Promoting pre-anthesis nitrogen accumulation in wheat to achieve high yield and nitrogen-use efficiency through agronomic measures. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 44, 2640–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Khan, S.; Sun, M.; Yu, S.; Ren, A.; Yang, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Z. Effect of different sowing methods and nitrogen rates on yield and quality of winter wheat in Loess Plateau of China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020, 18, 5701–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, W. High nitrogen application rate and planting density reduce wheat grain yield by reducing filling rate of inferior grain in middle spikelets. Crop J. 2021, 9, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, X.; Li, C.; Li, M.; Xiong, T.; Tang, Y. Dry matter and nitrogen accumulation, partitioning, and translocation in synthetic-derived wheat cultivars under nitrogen deficiency at the post-jointing stage. Field Crops Res. 2020, 248, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Hou, P. Optimal nitrogen distribution in maize canopy can synergistically improve maize yield and nitrogen utilization efficiency while reduce environmental risks. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 383, 109540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ren, C.; Wang, C.; Duan, J.; Reis, S.; Gu, B. Driving forces of nitrogen use efficiency in Chinese croplands on county scale. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, X.; Lam, S.; Yu, Y.; van Grinsven, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Wang, S.; Duan, J.; et al. Mitigating nitrogen pollution from global croplands with cost-effective measures. Nature 2021, 613, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinderpal-Singh; Kaur, S.; Singh, J.; Kaur, A.; Gupta, R.K. Rescheduling fertilizer nitrogen topdressing timings for improving productivity and mitigating N2O emissions in timely and late sown irrigated wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).