Abstract

The ramifications of climate change, which are projected to lead to increased drought, desertification, and water scarcity, are expected to have a significant impact on the agricultural sector of Türkiye, particularly in the Mediterranean coastal regions. This study presents an extensive evaluation of potential agricultural drought conditions in southwestern Türkiye, using a high-resolution, convection-permitting (0.025°) modeling approach. We employ a single, physically consistent model chain, dynamically downscaling the CMIP6 MPI-ESM-HR Earth System Model with the COSMO-CLM regional climate model at a convection-permitting (CP) resolution (0.025°) under IPCC Shared Socioeconomic Pathways SSP3-7.0, reflecting a high-emission scenario with regional socioeconomic challenges. Southwestern Türkiye, situated at the intersection of the Mediterranean and continental climates, hosts rare climatic and ecological conditions that sustain a highly productive and diverse agricultural system. This region forms the backbone of Türkiye’s agricultural economy but is increasingly vulnerable to climate variability and fluctuations that threaten its agricultural stability and resilience. Our study employs a novel approach that utilizes multivariate assessment of agricultural drought in the Mediterranean Region by integrating precipitation, soil moisture, and temperature variables from 2.5 km resolution climate simulations. Agricultural drought conditions were evaluated using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), the Standardized Soil Moisture Index (SSI), and the Standardized Temperature Index (STI), derived by normalizing respective climate variables from climate simulations spanning from 1995 to 2014 for the historical period, from 2040 to 2049 and from 2070 to 2079 for future projections. CP climate simulations (CPCSs) exhibit a modest warm and dry bias during all seasons but slightly wetter conditions during summer when compared with station observations. Correlations between indices indicate that soil moisture variations in the future will become more sensitive to changes in temperature rather than precipitation. Results from this specific model chain reveal that the probability of compound events where precipitation and soil moisture deficits coincide with anomalously high temperatures will rise for all threshold levels under the SSP3-7.0 scenario towards the end of the century. For the most severe conditions (|Z| > 1.2), the compound likelihood increases to about 3%, highlighting the enhanced occurrence of rare events in a changing climate. These findings, conditional on the model and scenario used, provide a high-resolution, physically grounded perspective on the potential intensification of agricultural drought regimes.

1. Introduction

Drought is among the most intricate and widespread natural disasters, exerting a substantial impact on water supplies, ecosystems, agriculture, and global economy. Drought is classified under four main categories: meteorological, hydrological, agricultural, and socioeconomic [1,2]. Meteorological drought arises from a scarcity of precipitation, hydrological drought from reduced surface and groundwater reserves, agricultural drought from insufficient moisture for crops, and socioeconomic drought when water demand exceeds supply. In recent years, the depletion of groundwater resources has prompted the proposal of “groundwater drought” as a fifth category [3]. In order to measure and track features under various meteorological and hydrological situations, drought indices are crucial instruments. The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), one of the first and most popular drought indices, was proposed to quantify the combined impact of temperature and precipitation on soil moisture balance [4]. In order to measure climatic droughts using precipitation data over various time scales, the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) was subsequently established [5]. Furthermore, in order to better reflect the effects of climate change on drought, the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), which is multiscalar drought index used to assess meteorological drought by considering both precipitation and temperature through potential evapotranspiration. It is one of the most popular drought indices, and a relatively recent development based on the SPI [6,7,8].

In recent decades, global temperature rises and precipitation regime changes have increased climatic variability and unpredictability, amplifying hydrometeorological extremes. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human-induced climate change has enhanced atmospheric evaporation demand, resulting in more frequent and severe agricultural and ecological droughts in many places, including the Mediterranean [9,10]. The Mediterranean Basin is widely recognized as a climate change hotspot and is experiencing amplified warming and multiple compounding climate hazards [10]. Since the 1980s, the temperature in the Mediterranean Basin has increased faster than the global average, and future warming over Mediterranean land areas is projected to exceed the global mean [10]. At the same time, precipitation across the Mediterranean basin exhibits pronounced spatiotemporal variability, primarily modulated by large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns [10,11]. Observations within the last couple of decades and climate projections reveal shifts in precipitation patterns, resulting overall decrease in precipitation. These combined trends of intensified heat and drying have already increased the frequency and severity of droughts over the basin. Projections indicate that the frequency of extreme agricultural droughts in substantial regions of the Mediterranean is anticipated to escalate by 150% to 200% if global temperatures rise by 2 °C, and by more than 200% in the case of 4 °C [12].

Türkiye is situated at the eastern boundary of the Mediterranean Basin, which is recognized as one of the most vulnerable and climatologically complex subregions within this climate change hotspot. This region is already exhibiting significant impact of climate change and is projected to face further intensification in climate driven risks, particularly in the form of rising temperatures, increasing aridity, and more frequent and severe extreme events [13,14,15]. This alteration in the climate dynamics exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in agricultural and ecological systems, particularly, rendering drought risk management more crucial than ever before.

Southern Türkiye is expected to be greatly impacted by climate change, especially along the Mediterranean coast, where precipitation may drop by as much as 30% by the middle of the century. The most severe warming is predicted to occur during the summer months, reaching 5–6 °C across the Aegean region under severe climate scenarios. Other seasons experience temperature increases of 3–4 °C, while winter is predicted to see the least amount of warming, at 2–3 °C. Regional drought conditions are expected to worsen as a result of these changes [16,17,18]. Turunçoğlu et al. [19] found that future soil moisture reductions will be much stronger along the Taurus Mountain range compared to the surrounding region, and the southwestern, southeastern and central parts of Türkiye under the SRES emission scenarios (A1FI and A2) through the end of twenty-first century. Similarly, Kelebek et al. [20] showed, through their modified Climate Extremes Index (mCEI) approach, that western Türkiye is located in a hotspot of the European–Mediterranean region affected by compound climate extremes. Beside these, Yeşilköy and Şaylan [21] indicated that drought occurrences in northwestern Türkiye will increase by 47–41% for the period between 2051 and 2099 under RCP8.5 scenario. Türkiye’s agricultural industry is seriously threatened by climate change, particularly in light of the growing drought, desertification, and water shortage in dry and semi-arid areas. Reduced agricultural production is likely to result from these changes, and farmers will be required to adjust by switching to more drought-resistant crops [22].

Indexes like the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) have been widely used to assess meteorological and agricultural drought across different temporal scales in Türkiye [21,23,24,25,26,27,28]. For instance, Tanrıkulu et al. [29] used the SPI to evaluate drought variability in the Aegean region and revealed that inland provinces such as Denizli were more vulnerable to drought, while İzmir had experienced comparatively more frequent wet years. Additionally, Poyraz [30] evaluated projected SPI-based drought trends in Türkiye’s Mediterranean climate zones using CORDEX regional climate model outputs, revealing a notable amplification of drought, particularly in Muğla and western Antalya. Furthermore, Öz et al. [31] examined drought conditions throughout Türkiye employing SPI, SPEI, and Reconnaissance Drought Index (RDI) utilizing data from 219 meteorological stations between 1991 and 2022. The study demonstrated that the country, particularly in areas within the Mediterranean basin, has experienced growing degree of drought as a result of increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation.

Although indices such as the SPI and the SPEI are valuable in drought assessment, drought is driven by multiple interconnected factors, including precipitation, soil moisture, and runoff, that do not always vary at the same timescales. The IPCC first defined these events as compound event, which is when two or more events happen at the same time, sequentially, or in different regions at the same time [32,33,34,35]. For example, agricultural drought may not necessarily follow meteorological drought in areas that typically receive heavy rainfall, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on precipitation-based indices [36]. In order to overcome this constraint, Hao and AghaKouchak [36] introduced the Multivariate Standardized Drought Index (MSDI), which combines the SPI and the Standardized Soil Moisture Index (SSI) utilizing a copula-based methodology. This approach enables the joint characterization of agricultural and meteorological drought conditions by improving the determination of drought onset and duration relative to univariate indices. Extending this methodology, Hao et al. [37] presented a multivariate statistical framework to assess compound extreme events by combining several climate variables such as monthly precipitation, soil moisture, and temperature derived from the NLDAS-2 dataset. Compared to traditional univariate approaches, their meta-Gaussian model-based methodology provides a more improved comprehension of climate risks by enabling a probabilistic assessment of joint extremes. Therefore, this multivariate framework offers a more robust understanding of compound climate risks.

This study aims to advance drought characterization in Türkiye by implementing both univariate and multivariate drought analyses with state-of-the-art convective-permitting climate simulations. A multivariate framework jointly analyzing precipitation, soil moisture, and temperature anomalies is employed to assess agricultural drought, offering a novel perspective in regional drought diagnostics. High-resolution cloud-resolving simulations with the COSMO-CLM regional climate model at a spatial resolution of 0.025° form the foundation of this approach, enabling an explicit representation of convective processes, a detailed evaluation of local-scale climate dynamics and their influence on the evolution and intensification of agricultural droughts under changing climatic conditions. This unique high-resolution approach provides an unprecedented level of detail for assessing how small-scale processes shape drought evolution under both historical (1995–2014) and future (2040–2049, 2070–2079) under high-emission SSP3-7.0 scenario.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Domain

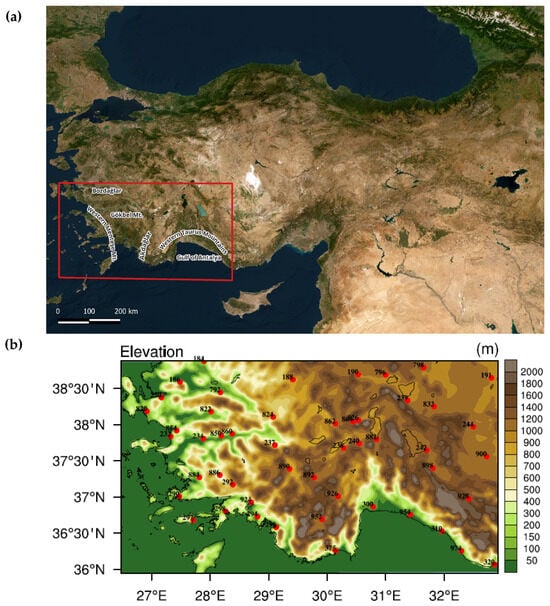

The geographical area of southwestern Türkiye is situated between longitudes 27–34° east and latitudes 36–39° north and is bordered by the Aegean Sea to the west and the Mediterranean Sea to the south, as shown in Figure 1. This region includes the entirety of the Eastern Mediterranean, Antalya, Burdur Lakes, Western Mediterranean, Büyük Menderes, Küçük Menderes, Konya, and Afyon-Akarçay basins, as well as smaller portions of the Northern Aegean, Susurluk, Sakarya, and Kızılırmak basins.

Figure 1.

(a) Model domains at 0.11° and 0.025° resolutions. Inner red box shows study domain with terrain and names of prominent features. (b) Model topography at 0.025° resolution. Red dots show the locations of TSMS stations with last 3-digit of station numbers.

Topographically, the western and southern parts of the study area feature low-altitude river valleys and plains (0–500 m), while moving inland, elevations gradually increase, forming plateaus at 1500–2000 m and mountainous ranges that can exceed 3000 m in elevation. Beyond these mountain ranges, elevations decrease again, forming plateaus between 1000 and 1500 m. This altitudinal variation, combined with complex physiographic structures, results in a high level of ecological and climatic diversity across the study area [38].

Southwestern Türkiye is characterized by the coexistence of two distinct climate zones: the Mediterranean climate prevalent along the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts, and the continental climate observed in the interior regions. The Mediterranean climate, dominant up to elevations of 800–1000 m on the seaward slopes of the Taurus Mountains, exhibits hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. In this climate zone, average temperatures range from 6.4 °C in January to 26.8 °C in July [39]. In higher elevations, a specific variant known as the Mediterranean mountain climate is observed. Along the northern parts of the Aegean coast, transitional variations in the Mediterranean climate are seen due to increasing latitude and topographic influences. Conversely, the continental climate, particularly prevalent in the eastern portions of the study area, is characterized by cold winters and moderately warm summers. January is typically the coldest month, with an average temperature of −0.7 °C, while July is the warmest at 22 °C. The annual average precipitation is approximately 413.8 mm, and the mean annual temperature is 10.8 °C. Precipitation is unevenly distributed, with 14.7% occurring in summer and the majority in spring. The mean annual relative humidity is about 63.7% [40].

This climatic diversity is mirrored in the region’s vegetation. The dominant natural vegetation in Mediterranean zones includes Pinus brutia (Turkish red pine) forests, which, in degraded areas at lower elevations (0–800 m), transition into maquis communities composed of drought-tolerant, evergreen shrubs. Common species include laurel (Laurus nobilis), cypress (Cupressus sempervirens), and oak (Quercus spp.). In addition to wild vegetation, economically important fruit trees such as olive (Olea europaea), fig (Ficus carica), walnut (Juglans regia), and grapevine (Vitis vinifera) are extensively cultivated. The region also supports the growth of cotton, sesame, flax, and various citrus fruits, which are key agricultural products [41]. In contrast, the natural vegetation of the continental climate zones is predominantly steppe at lower altitudes, while drought-tolerant oak forests appear at higher elevations with increased precipitation. Cereal crops, particularly wheat and barley, dominate agricultural practices. In irrigated areas, sugar beet cultivation is widespread [42].

Southwestern Türkiye, located near the subtropical climate zone and hosting transitional zones between Mediterranean and continental climates, possesses a globally rare combination of climatic and ecological conditions. This unique climate structure supports a rich and diverse agricultural production system and plays a strategic role in Türkiye’s agricultural economy. The region’s geographic proximity to Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa further enhances its significance by facilitating efficient export logistics for high-value crops. The study area represents a biogeographically and economically critical zone for understanding the interactions between climate, vegetation, and agricultural land use [43,44].

However, this climatic and agricultural richness also makes the region acutely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly soil moisture changes and increased drought frequency. Understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of drought in this region is therefore essential not only for agricultural and water resource planning, but also for ecosystem conservation and climate adaptation strategies. Thus, robust drought assessments in this region are necessary to elaborate future risks.

2.2. Convection-Permitting Climate Simulations

We performed high-resolution climate simulations using COSMO-CLM [45,46] (version 6.0) with a resolution of 0.025° (approximately 2.5 km) over a domain (shown with red box in Figure 1). Simulations were conducted for the historical period (1995 to 2014), and for two decadal future periods (2040–2049, 2070–2079), under the SSP3-7.0 scenario from the new Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) scenarios developed for the IPCC 6th Assessment Report (AR6). The SSP3-7.0 scenario, along with SSP5-8.5, represents one of the highest radiative forcing pathways within the current scenario architecture, projecting an additional radiative forcing of 7 W/m2 by the year 2100 [47]. SSP3-7.0 entails high challenges to both mitigation and adaptation making it a useful worst-case scenario for studying climate impacts and regional vulnerabilities. It eases the exploration of worst-case climate outcomes and enables identification where adaptation needs are greatest, especially, at regional levels where local factors dominate [10]. Moreover, the high-end scenarios RCP8.5 or SSP5-8.5 have recently been argued to be implausible to unfold in light of recent developments in the energy sector [48].

The performance of MPI-ESM-HR from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Version 6 (CMIP6) over Türkiye has been evaluated as one of the most reliable among earth system models, according to comparative assessments [49]. Hence, in this study, COSMO-CLM regional climate model was driven by the earth system model (ESM) of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, MPI-ESM-HR, to downscale the large-scale signal to the regional scale. Since MPI-ESM-HR resolution is around 100 km, we follow dynamical downscaling approach and gradually increase the resolution. Firstly, the outputs of MPI-ESM-HR were downscaled to coarse resolution (0.11°) over mother domain, which covers Türkiye and its vicinity as shown in Figure 1. Then, the outputs of 12 km resolutions were utilized as initial and boundary condition for convection-permitting simulations.

The main distinction between the configurations employed for the CPCS (0.025° resolution) and the non-CPCS (0.11° resolution) simulations pertains primarily to the treatment of microphysical and convection parameterizations. The deep convection parameterization [50] is deactivated in the CPCSs, but the scheme for shallow convection is enabled. The microphysics scheme has undergone a transformation from a two-category ice to a more complex, three-category ice scheme. This enhanced scheme incorporates graupel, thereby facilitating a more accurate simulation of mixed-phase processes. The vertical atmospheric resolution is also enhanced by increasing the number of model levels from 40 to 50. NASA/GISS aerosol climatology data, and FAO-DSMW (Digital Soil Map of the World) soil characteristic data are utilized to produce the external parameter file. The soil is uniformly configured with nine vertical levels across all nested domains. Additionally, GLOBECOVER land cover data, which is created using the fine resolution (300 m) source data from MERIS sensor on board the ENVISAT satellite mission [51] is preferred. Land use and land-cover (LULC) changes are an important component of the land–atmosphere interactions and can influence regional climate and agricultural drought processes. Available LULC projections within the SSP framework are provided at much coarser resolution than our 2.5 km convection-permitting grid [52] and are highly uncertain at basin and sub-basin scales. Consistent with many regional climate and hydrological impact studies, including CORDEX experiments and convection-permitting COSMO-CLM applications, we therefore adopt a fixed present-day land use in order to focus on the response to large-scale climate forcing, by assuming that uncertainties from land-cover datasets in regional mean temperature tend to be smaller than those from the climate projections themselves, even though local effects (e.g., urbanization) can be substantial.

Mother domain climate simulations were initialized two years prior to the reference period, and extended through 2100 with the boundary forcing data post-2014 derived from the corresponding high-emission pathway SSP3-7.0. Subsequently, convection permitting model simulations were conducted for tree distinct time slices: 1994–2014 (historical), 2039–49 (mid-century), and 2069–79 (late-century). For each simulation period, the first year was treated as a spin-up time to allow soil moisture and related land-surface variables to converge towards equilibrium with atmospheric conditions. Although a 6-month spin-up duration is recommended as a general guideline for RCM applications to ensure stabilization of both atmospheric and soil processes [53], for assessing optimal model performance across both atmospheric and soil conditions, a full year was adopted in this study to enhance consistency and reduce initialization biases, particularly in high-resolution land–atmosphere coupling.

2.3. Bias Correction

The temperature and precipitation simulations of COSMO-CLM model were corrected according to the domain averaged annual bias of the model for the reference period with respect to Turkish State Meteorological Service (TSMS) stations using delta change/mean value methodology due to the unavailability of gridded observational datasets at such spatial resolution over the study area. The use of interpolated low-resolution data for the bias corrections hinders variability in atmospheric variables by smoothing out the physical and dynamical signals arising from interactions between atmospheric flow and better represented surface characteristics, such as topography, coastlines, and land–sea contrasts.

In delta change approach, corrected future time series of temperature field are computed by subtracting annual bias obtained for the reference period from the model simulations for future periods. A total of 58 meteorological stations, which are fairly well distributed over the study area, were used for the bias calculation. Similarly, the new future time series for precipitation is derived from multiplication of unbiased future simulations with relative present-day model bias that keeps mean and variance ratio constant [54]. Moreover, seasonal biases of temperature and precipitation values are discussed in “Model Verification” (Section 3.1).

2.4. Drought Analysis

Drought identification is a highly intricate process, and it cannot be accurately determined using just one meteorological variable, such as precipitation. Instead, the use of multiple meteorological variables such as precipitation, temperature, soil moisture provides a more effective approach for identifying drought events [55]. In this study, instead of univariate drought analysis, multivariate drought analysis was performed by using the Standardized Precipitation Index [5], the Standardized Soil Moisture Index [36,37] and the Standardized Temperature Index-STI [37,56]. Current climatic conditions and future projections under SSP3-7.0 were examined in terms of agricultural drought over the study area.

The SPI is a widely used statistical drought assessment tool, originally developed by McKee et al. [5], designed to quantify precipitation deficits or surpluses at various temporal scales by fitting a probability distribution function (commonly the gamma distribution) to long-term precipitation records. The fitted distribution is then transformed into a standard normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This standardization process allows SPI to consistently classify both wet and dry periods across different regions and climatic regimes [57,58,59]. Despite being based primarily on precipitation, SPI has also been adapted for other variables such as soil moisture and streamflow, thereby expanding its applicability in both meteorological and hydrological drought assessments [8]. In practical terms, SPI values within ±1 standard deviation represent approximately 68% of the data distribution, while ±2 standard deviations cover about 95%. This allows the probability of a precipitation total for a specific time period to be identified with a corresponding SPI value, enabling comparison of drought frequencies, intensities, and durations across space and time [60,61].

In this study, the SPI at a 3-month timescale (SPI-3) was chosen since it is proven in its effectiveness in detecting short-term meteorological droughts that closely align with agricultural drought. SPI variants like SPI-3 and SPI-6, are better suited for identifying agricultural droughts as they capture sub-seasonal precipitation deficits that directly impact topsoil moisture dynamics. These time scales coinciding to critical phenological stages of crop development make them highly useful for analyzing drought-induced impact on agricultural productivity [61,62,63].

To complement the precipitation-based analysis, both the SSI and STI were computed utilizing a 1-month period in order to account for transient variations in soil moisture and temperature, which may have an immediate physiological stress on vegetation, especially during the early growing season or heat-sensitive phenological phases. This approach is based on the methodology used by Hao et al. [37] and is further supported by a growing body of research emphasizing the usefulness of short-term soil moisture indicators for characterizing onset of droughts and heat stress conditions [64,65]. Additionally, SPI and SSI indices were computed using the SPEI package in R [66]. This multivariate approach, combining SPI-3 with short-term SSI and STI indicators, allows a multidimensional analysis of drought/wetness conditions by incorporating not only meteorological anomalies, but also soil–plant–atmosphere interactions defining the onset, intensity, and persistence of agricultural drought.

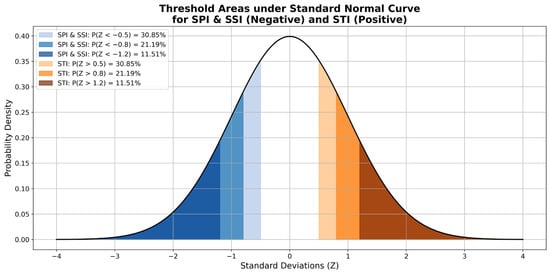

In order to evaluate the behavior of drought indicators under varying conditions, areas under the standard normal distribution curve were examined for four distinct screening thresholds. Thresholds for STI were based on positive deviations (Z > 0.5, Z > 0.8, Z > 1.2), whereas thresholds for SPI and SSI were defined using negative deviations (Z < −0.5, Z < −0.8, Z < −1.2). These thresholds are particularly useful for identifying severe and frequent events associated with agricultural drought. The efficiency of the indicators in detecting severe conditions is shown by the probability area that corresponds to each threshold value under the standard normal distribution given in Figure 2. For instance, a threshold of Z < −1.2 indicates an 11.51% chance for SPI and SSI, whereas a threshold of Z > 1.2 shows positive temperature anomalies for STI. These distributions make it possible to compare indicators in terms of both intensity and frequency.

Figure 2.

Areas under the standard normal curve corresponding to the SPI, SSI (negative) and STI (positive) thresholds.

We employed a non-parametric empirical counting method to calculate joint probabilities of normalized precipitation (SPI), soil moisture (SSI), and temperature (STI). At each grid point across the spatial domain, we characterized the probability distribution of each climate variable such as precipitation, soil moisture, and temperature by systematically exploring candidate distribution functions. For precipitation and soil moisture, which typically exhibit bounded and skewed behaviors, we evaluated Gamma, Weibull, and Log-Normal distributions, while for temperature we assessed Gaussian and Generalized Extreme Value distributions. This grid-specific approach ensured that our normalization procedure respected the unique statistical characteristics of each variable across diverse climatic regions, providing a robust foundation for subsequent joint probability analysis of compound extremes. During normalization, we used distribution-specific transformations with parameters fixed from the 1995–2014 reference period: Gamma distribution for precipitation and soil moisture, and Gaussian distribution for temperature. These same reference period parameters were applied to normalize future projections for two decadal periods (2040–2049 and 2070–2079), ensuring consistent extreme event definition across temporal comparisons. After normalization, joint probabilities were directly estimated as the proportion of observations satisfying concurrent threshold conditions: P(SPI < SSItreshold, SSI < SSItreshold, STI > STItreshold) = (number of favorable cases)/(total number of cases). This empirical approach preserves the observed dependence structure among climate variables without requiring parametric models. The fixed-parameter approach ensures that changes in joint probabilities reflect genuine shifts in compound event frequency rather than methodological inconsistencies.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Verification

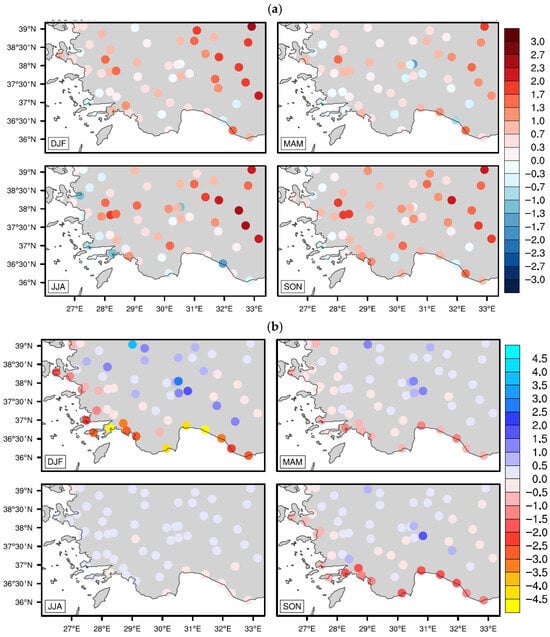

The performance of the COSMO-CLM model at convection-permitting resolution was evaluated through a comparative analysis with temperature (Figure 3a) and precipitation (Figure 3b) measurements obtained from meteorological station networks of TSMS. This approach enabled a point-based validation of the model’s ability to reproduce key climate variables, allowing for an evaluation of the skill of the COSMO-CLM driven by MPI-ESM-HR in reproducing observed climatic variability at regional scale. Nonetheless, the observational network exhibits limited representation of high-altitude zones, which may compromise the accuracy of the analysis in mountainous regions. The limited representation of the analysis in mountainous regions has an indirect impact on agricultural ecosystems. The impact on agricultural ecosystems is related to the supply of water used for irrigation from basins such as lakes, ponds, and dams.

Figure 3.

Seasonal (a) mean temperature (°C) and (b) total precipitation (mm/day) differences between CCLM and TSMS station observations during the reference period of 1995–2014.

Figure 3a indicates that COSMO-CLM driven by MPI-ESM-HR exhibits a warm bias throughout the year, with an average annual deviation of 0.6 °C. This is consistent with the comparison of CMIP6 EC-Earth3-Veg-driven COSMO-CLM model against ERA5-Land reanalysis over Türkiye for the same reference period [67]. However, Sonuç et al. [68] found warmer conditions in winter and spring, but cooler conditions in summer using CMIP5 MPI-ESM-LR driven COSMO-CLM for the reference period of 1991–2005. Nevertheless, they also ascertained that the winter season exhibited the most significant bias, with an average of 2.3 °C over northwestern Türkiye. In contrast, our findings differ in that the lowest bias is obtained in the southwestern region of Türkiye, reaching only 0.4 °C in spring and 0.5 °C in summer, which is inconsistent with the findings of Unal et al. [67]. Along the Aegean coast, where the elevation is low but the terrain is highly indented, the model generally displays consistent performance across seasons, with the exception of summer months. This can be attributed to the model’s ability to adequately resolve the complex topography, facilitated by its high resolution.

The spatial averages of the seasonal differences in Figure 3b indicate that the model produces 0.2 mm/day less precipitation than the observed amounts in autumn, which is consistent with the findings of Sonuç et al. [68]. However, CCLM shows slightly wet (negative) bias with 0.1 (−0.5) mm/day in summer (winter) season. In almost all seasons, the model generally produces less precipitation than observations along the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts of the study area. Results clearly demonstrate the added value of the CPM simulations which account the interactions of atmospheric flow field with the topography and land use since the convection is implicitly solved.

Direct validation of simulated soil moisture is not possible, because long, homogeneous and spatially representative in situ soil moisture observations are not available for the study area. Existing measurements are restricted to a few experimental sites with short records and limited metadata, which are not suitable for evaluating multi-decadal, regional-scale simulations at the model grid spacing. Instead, we only evaluate the main atmospheric drivers of soil moisture (precipitation and near-surface temperature) against station observations.

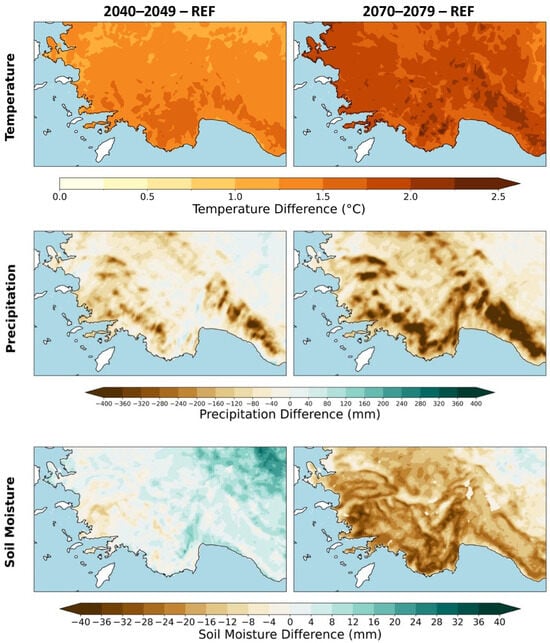

3.2. Climate Projections Under SSP3-7.0

The annual changes in mean temperature, total precipitation, and soil moisture with respect to the reference period (1995–2014) under the SSP3-7.0 scenario has been analyzed for 2040–2049 and 2070–2079 in southwestern Türkiye, as depicted in Figure 4. Projection results reveal that uniform warming is evident over almost all elevations, with intensification toward the far future. The temperature increase is significant across the southwest part of Türkiye, particularly over the inland basins around Central Anatolia and the inner Aegean valleys and elevated topographical regions. This increase is particularly pronounced in the southern latitudes and is consistent with the COSMO-CLM projections of Unal et al. [67] at 0.11° resolution driven by a different ESM of EC-Earth3-Veg with the same scenario. Coastal regions are moderated by the sea, while inland areas lack this buffering. Elevated plateaus and mountainous regions, though cooler in absolute terms, exhibit enhanced warming because of drying soils, and stronger land–atmosphere coupling. The temperature difference is expected to range from nearly 1.0 to 2.0 °C in most regions during the 2040–2049 period (Table 1). However, the increase is expected to exceed 2.5 °C in the second projection period.

Figure 4.

Differences in annual temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture between future (2040–2049 and 2070–2079) and reference (1995–2014) periods from COSMO-CLM simulations at a resolution of 0.025°.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of domain averaged changes in annual temperature (°C), precipitation (mm) and soil moisture (mm) relative to the reference climatology for 2040–2049 and 2070–2079, from COSMO-CLM 0.025° simulations.

Increases in average temperatures for the years in Table 1 will impact plant phenological growth. This will cause plants to develop more quickly, shortening yield-determining periods such as grain size. Significant yield reductions can be expected for cool-climate crops (wheat, barley, poppy). Warm-climate crops (cotton, corn, olives, vineyards) may initially be positively affected. However, with rising temperatures towards the 2070s, flowering stress and quality loss will become more pronounced. Furthermore, higher altitudes may become more suitable for crops such as viticulture and olive cultivation.

The spatial distribution of precipitation differences suggests a widespread decrease over much of the domain especially during the future periods. Orographically influenced coastal and mountain zones such as the western Anatolian mountains, Taurus Mountains and their foothill show pronounced drying and become stronger through 2070s. However, this signal in the near future period is spatially heterogeneous, with a modest increase in inland plateau of the Central Anatolia region encircled by mountain belts, aligning with Unal et al. [67]. Projections demonstrate a decline in annual precipitation over the southwestern Türkiye, with an estimated decrease of approximately 51 mm for the 2040–2049 period, and a more pronounced decrease of around 116 mm for the 2070–2079 period (Table 1). These patterns suggest that climate change induced circulation changes may weaken moist advection and storm activity, reducing precipitation in mountain regions. Önol and Ünal [18] indicated that the most statistically significant precipitation decrease is expected to occur (34%) in winter over Mediterranean region according to SRES A2 scenario. As in the period 2040–2049, the fact that the values predicted for the period 2070–2079 range from −847.32 mm to +57.88 mm clearly demonstrates the existence of significant and widespread geographical differences across the study area. The overall declining tendency is supported by the negative median values of −33.56 mm and −87.22 mm for the respective periods. These reductions being broadly consistent with those reported by Önol and Ünal [18] under the SRES A2 scenario, indicate that the projections are robust and consistent with earlier studies.

An examination of soil moisture reveals an average increase of 4% (approximately +5.67 mm) in the 2040–2049 period compared to the 1995–2014 reference period (Table 1). Spatial variability of the changes is considerable, ranging from −15.53 mm to +37.50 mm. The decline in precipitation will be particularly critical for crops dependent on spring rainfall. Decreasing precipitation and rising temperatures accelerate evaporation, increasing drought severity. Irregular rainfall patterns (sudden downpours, prolonged dry spells) create erosion and soil moisture imbalances. Irrigation water demand will increase, and competition for water will intensify, particularly in the Gediz, Küçük Menderes, and Büyük Menderes basins. As depicted in Figure 4, the largest increases are concentrated in inland basins such as Central Anatolia and inner valleys, with particularly maximum increases in the Cihanbeyli Plateau and its surroundings. This pattern likely reflects a warming induced shift from snow to rainfall which enhances direct soil recharge, while enclosed basins with low runoff efficiency and modest precipitation increases help to sustain higher soil moisture.

Conversely, decreases are anticipated in the coastal Aegean region, notably in the vicinity of Muğla province, where the Gökbel and Western Menteşe Mountains are located. Orographically influenced zones tend to dry out under reduced moisture advection, reduced orographic precipitation and enhanced drainage accelerating water loss.

In the long term (2070–2079), projections indicate an average decrease of 9% (equivalent to 12.37 mm) in soil moisture, with a range of change from −39.75 mm to +20.68 mm. While some short-term increases in soil moisture are projected in the 2040s, soil moisture declines significantly by the 2070s. This results in yield reductions, plant water stress, and premature ripening, particularly in rain-dependent agricultural areas (dryland farming). Cracking, crusting, and reduced biological activity may be observed in areas with low soil organic matter.

The declines will increase significantly in regions that were already drying out in the first period (2040–2049), such as Muğla, and extend to the province of Antalya, particularly in the regions encompassing the Akdağlar and Western Taurus Mountains. By the late 21st century, rising evaporative demand from warming outweighs local moisture retention, resulting in basin-wide drying. The findings of drying trend pronounced along major mountain ranges, such as Taurus Mountains, are consistent with the findings of the earlier studies [18,19,67].

3.3. Evolution of Correlations (STI–SPI3–SSI) from Historical Period to Future Decades

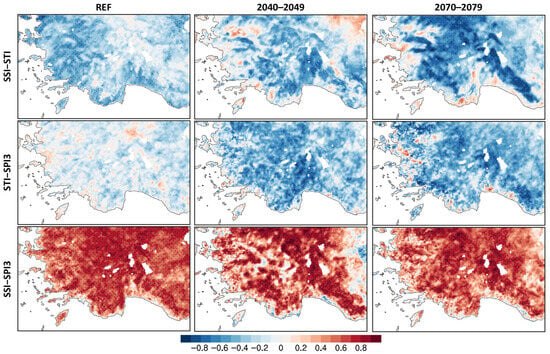

The annual correlations among temperature (STI), precipitation (SPI3), and soil moisture (SSI) were determined by Pearson correlation analysis using COSMO-CLM model outputs at a horizontal resolution of 0.025°. In the correlation analysis, we explicitly account for temporal autocorrelation in both variables. For each grid point, we estimate an effective sample size based on the lag-1 autocorrelation coefficients of the two time-series, following a standard lag-1 autocorrelation approach, following Von Storch and Zwiers [69]. The significance of the correlation coefficients is then assessed using a two-sided Student’s t-test with degrees of freedom adjusted to this effective sample size rather than the nominal sample size, providing a more conservative and statistically robust evaluation of correlation significance. Their spatial distributions of the Pearson correlation coefficients for the reference period 1995–2014 as well as the projected periods 2040–2049 and 2070–2079 are shown in Figure 5 while the statistics for each period based on spatial averages are given in Table 2.

Figure 5.

The spatial distributions of the Pearson correlation coefficients of the SSI, SPI3 and STI indices for the reference period of 1995–2014 and the future periods of 2040–2049 and 2070–2079. Significant correlations are shown with dots at a confidence level of 95%.

Table 2.

The spatial averages of the Pearson correlation coefficients of the SSI, SPI3 and STI indices for the reference period of 1995–2014 and the future periods of 2040–2049 and 2070–2079.

During the reference period, the STI exhibits the weakest correlations among the three indices within the inland lowlands. Across the study area, STI demonstrates a negative correlation with both SSI (−0.30) and SPI3 (−0.11). This reflects the physical link between temperature and evaporation: as temperatures increase, evaporative demand increases, leading to reduced soil moisture availability. Similarly, the negative STI and SPI3 association indicates that warmer temperature exacerbates precipitation deficits, thereby worsening drought conditions. Conversely, SSI and SPI3 are strongly and positively correlated (0.60), notably indicating precipitation variability as the dominant driver of soil moisture. A high degree of correlation, reaching 0.9, in the southern mountainous regions of Türkiye accentuates the strong influence of orographic precipitation on soil water recharge. Hao et al. [37] also determined that the correlation between SPI and SSI during the August months of 1979–2014 is positive in all regions of the US. Our results are broadly consistent with Hao et al. [37], we also find a basin-wide positive SSI-SPI3 relationship during August for the 1995–2014 period since agricultural drought, represented by soil moisture, is predominantly driven by precipitation variability. However, we see exceptions over certain coastal areas, indicating maritime moderation which can weaken the SSI-SPI3 coupling. Moreover, our seasonal analysis suggests emerging two features: negative STI-SPI3 (or SSI-STI) correlations peak in April and June as springtime warming elevates evaporative demand, partially decoupling soil moisture from short-term precipitation anomalies. By contrast SSI-SPI3 coupling strengthens toward an annual maximum in December (0.8), when lower temperatures suppress evapotranspiration and precipitation becomes the primary driver of water accumulation in the soil.

From 2040 to 2049, the correlation structure changed notably, with temperature-based indicators strengthening at comparable levels. The SSI and SPI3 continue to have a positive association with a domain mean near 0.5, although the minimum correlation value falls near zero in some regions, suggesting indicating partial decoupling of soil moisture from precipitation. In contrast the SSI–STI correlation becomes more negative, particularly in high elevated areas where evaporative demand is accelerates soil drying under elevated temperatures. Despite the persistent negative correlation between SSI and STI (−0.25) during 2040–2049 period, the pronounced positive correlations are observed in some low elevated areas around coastal regions such as Marmaris and İzmir, and in inland plateaus (e.g., Haymana, Cihanbeyli) and semi-closed basins, such as Central Anatolia, exhibiting a reversing relationship compared to the reference period. The correlation between SPI3 and STI is negative with an average value of −0.37 and increases its strength throughout the future periods. The negative dependence between SPI3 and STI reflects land–surface feedbacks: reduced soil water lowers latent heat flux while boosting sensible heat, resulting in hotter conditions. Slightly stronger negative relationships appear along orographic belts (e.g., Aegean ranges, Taurus foothills), where land–atmosphere interactions are strong. These results underscore the notion that, by the mid-21st century, temperature exerts a more dominant control on soil moisture variability than precipitation across most regions of the domain.

Meanwhile, a more perceptible change between 2070 and 2079 emerges when examining the relationships between temperature, soil moisture, and precipitation based on spatial averages. The mean SPI3-SSI correlation remains strongly positive over inland regions of Türkiye, confirming the central role of precipitation in shaping soil moisture variability. This sensitivity becomes most evident in mountainous regions and inland plateaus, where precipitation anomalies directly translate into soil recharge differences due to high topographic control on infiltration and limited outflow pathways. However, the minimum value is anticipated to decline from −0.45 to −0.70, indicating that in certain regions, increased precipitation may no longer yield the anticipated positive effect on soil moisture storage, and the inverse relationship may likely intensify over time. This emerging inverse relationship implies that the hydrological response to rainfall becomes increasingly constrained under elevated temperatures and enhanced evapotranspiration. On the other hand, SSI and STI correlation intensifies relative to both reference and mid-century periods, with increases in both its magnitude and spatial coherence. These situations reveal that factors such as rising temperatures in these regions may exert a more substantial influence on soil moisture than precipitation. Additionally, the correlation between SPI3 and STI is projected to reach an average value of −0.39. This is the strongest negative correlation observed among all periods, suggesting that the impact of rising temperatures on precipitation will amplify over time. However, from the reference period until the late 1970s, a gradual increase in the positive correlation is expected in regions such as the southeast and west coasts.

Regionally, a gradual rise in positive correlations is still apparent along the southeast and western coastal regions, contrasting with the deepening negative relationships in central and elevated areas. Comparatively, while the reference period exhibited a precipitation-driven regime and 2040–2049 signaled transitional behavior, the 2070–2079 decade reveals a climate increasingly dominated by temperature–soil moisture feedbacks.

In this case, the most significant change is the decrease in soil moisture during warm periods and the increased dependence on winter rainfall. This will increase summer drought in the long term, exacerbating moisture deficits. While a modest yield loss is expected in production models entirely dependent on rainfall, such as cereals, due to early maturation face in the future. For more perennial crops, a decline in quality and lower protein/oil/water ratios will inevitably occur. This transition marks a shift from precipitation-controlled to temperature-controlled drought regimes across most of Türkiye. These projections are consistent with evidence that strong temperature–soil moisture coupling and more frequent droughts can cause grain yield losses exceeding 40%, increase yield instability, and lead to 20–60% yield reductions in drought-prone regions by late century [70,71,72,73,74].

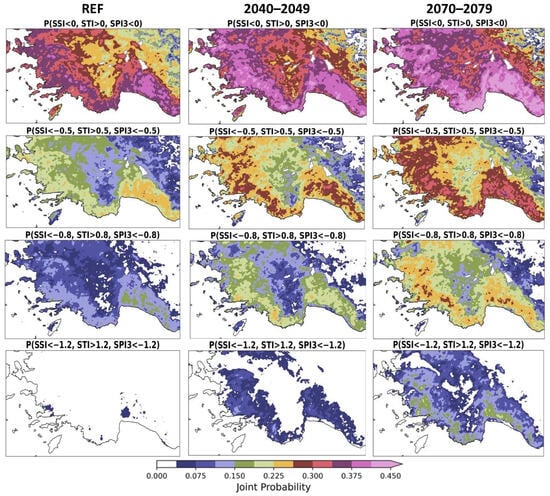

3.4. Transition in the Probability Regime of Compound Drought-Heat Events

The likelihood of concurrent dry and hot conditions under various combinations was quantified for the reference period (1995–2014) and two future projection periods (2040–2049 and 2070–2079) according to the SSP3-7.0 scenario. For each combination are illustrated in each row of Figure 6. Dryness classes follow the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM): abnormally dry, moderate drought, and severe drought at SPI3 thresholds of −0.5, −0.8, and −1.2, respectively [75].

Figure 6.

The probability of the compound extreme of low SPI/SSI and high STI with threshold values 0, −0.5, −0.8 and −1.2 for the SPI/SSI and 0, 0.5, 0.8 for the STI for the future periods (2040–2049 and 2070–2079) compared to the reference period (1995–2014), based on COSMO-CLM simulations at a resolution of 0.025°.

It can be inferred from Figure 6 that compound events with threshold values (SSI < 0, STI > 0, SPI3 < 0) already occur with a frequency that cannot be disregarded during the reference period, particularly in coastal regions where the maximum joint probability reaches 0.42 (Table 3). The probability of concurrent dry and hot conditions appears to decrease as thresholds shifts toward more severe combinations during the reference period. For instance, the average probability drops drastically to 0.04 under moderate drought conditions (Z < −0.8 and Z > 0.8), and approaches zero for the most severe thresholds (Z < −1.2 and Z > 1.2), suggesting that such triple extremes were virtually non-existent in the reference period. Albeit, only isolated occurrences with a notably low probability are found in some districts of Antalya and Muğla cities as a result of local feedbacks between radiation, soil moisture, and temperature. Consequently, a high probability of compound drought and heat extremes is evident in regions where SPI3 (or SSI) and STI exhibit a significant negative correlation, consistent with the findings of Hao et al. [37]. This phenomenon is presumably attributable to the interaction between the moisture deficit and the high temperatures in this region, confirming land–atmosphere feedbacks.

Table 3.

The spatial minimum, maximum and average values of the probabilities shown in Figure 6.

The projected increase in both the probability and persistence of these events points to a strengthening of land–atmosphere feedbacks under continued warming. Reduced soil moisture suppresses evapotranspiration and raises the Bowen ratio [76,77], shifting the surface energy balance toward sensible heating. This leads to higher near-surface air temperatures and vapor pressure deficit, which in turn accelerates soil-moisture loss [37,78,79,80]. The resulting positive feedback loop amplifies both heat and drought stress, enhancing the likelihood of simultaneous extremes and their temporal clustering. Consequently, the transfer of sensible heat flux is augmented to further enhance air temperature anomalies [81,82,83]. Similar mechanisms have been documented in other transitional climate regimes, such as northeast–southwest China, where the severity of compound dry-hot events is closely linked to soil moisture along semi-humid and semi-arid boundaries [78].

At the same time, the findings are consistent with evidence that compound dry–hot events can attain high intensity even in relatively humid regions when soil moisture, atmospheric humidity, and local energy balance interact in specific ways [84]. The spread of compound extremes into mountainous and coastal terrain reveals a key topographic control: steep slopes accelerate runoff, limiting soil-water storage and depleting the natural buffer against drought. This process effectively primes these landscapes for prolonged episodes of concurrent heat and aridity.

During 2040–2049 future period, the likelihood of compound events is expected to increase across all threshold values under the SSP3-7.0 scenario. Both the mean and maximum joint probabilities exhibit noticeable extension, indicating a spatially coherent intensification of concurrent soil-moisture, precipitation, and temperature anomalies. The largest relative change in probability compared to the reference period is occurred in moderate events (SSI < −0.8, STI > 0.8, SPI3 < −0.8), whose mean probability rises from 0.04 to 0.06, representing approximately a 50% increase. Similarly, the probability of occurrence of mild compound events (SSI < 0, STI > 0, SPI3 < 0) is anticipated to reach 17%, suggesting such co-occurrences becoming a regular feature of the regional climate. Spatially, these increases are concentrated in regions that already exhibited higher joint probabilities during the reference period, particularly over western and southern part of the study domain. Moreover, severe compound events (SSI < −1.2, STI > 1.2, SPI3 < −1.2) which were almost absent in the reference period begin to spread to the mountainous regions around Antalya and Muğla provinces where the probability of occurrence was negligible. This spatial expansion toward orographically complex terrain points to enhanced sensitivity of these areas to warming-induced moisture stress.

Under late-century warming (2070–2079), the intensification of compound events becomes considerably more pronounced. Both the frequency and spatial extent of co-occurrences increase nonlinearly, with strong and severe events approximately doubling relative to mid-century. Furthermore, under the most severe conditions (SSI < −1.2, STI > 1.2, SPI3 < −1.2), likelihood of the most extreme triple anomalies approaches 3%, which was essentially zero in the reference period. Spatial maxima rise, reaching 0.31 for strong events and 0.48 for mild combinations, suggests a regime shift toward frequent and spatially extensive compound drought–heat conditions. Collectively, these patterns indicate that occurrences previously deemed exceptional are becoming increasingly likely, reflecting a transition from precipitation-limited to energy-limited drought dynamics across much of the domain.

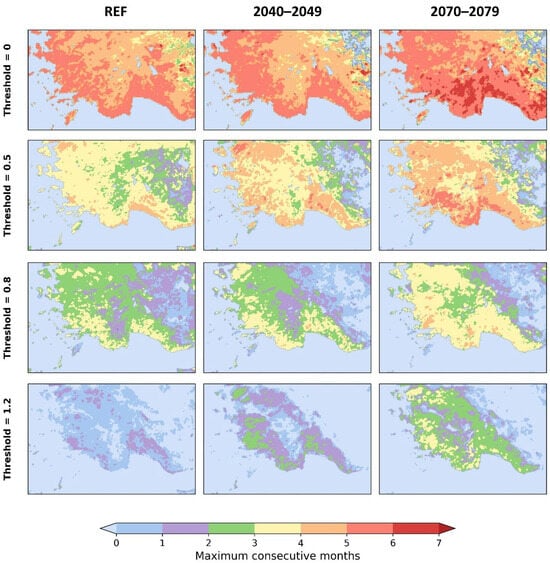

3.5. Persistence of Compound Events

Figure 7 illustrates the spatial distribution of maximum number of consecutive months with concurrent dry and hot conditions during the reference and future periods, evaluated for the four distinct thresholds given in Figure 6. In accordance with the results of the probability analysis, as the threshold values undergo a shift toward more severe combinations in the reference period, the duration of concurrent dry-hot events decreases gradually, suggesting that higher thresholds are satisfied with diminished persistence on space and time. For instance, the maximum number of consecutive months decreases to 2–3 under moderate drought conditions for the threshold 0.8, and approaches zero at the most severe thresholds of 1.2. This indicates that such triple extreme events did not persist for an extended period during the 20-year reference period. Additionally, the maximum number of consecutive months is generally higher in regions where the probabilities are also high. In other words, areas with higher frequency of the compound events coincide with greater temporal persistence. The maximum persistence of a 0.5 dryness threshold, which is approximately 5 months in 20 years, occurs on the slopes of the Taurus Mountains facing the Gulf of Antalya, and the probability of these conditions prevailing in this region is also higher (>22%) than in the rest of the study area. On steep slopes, runoff is high; some of the precipitation is rapidly removed from the surface, leading to a rapid decrease in soil moisture. While the oak forests within these regions exhibit resilience to drought, their capacity to effectively store or maintain surface moisture over extended periods is limited. This, in turn, enhances the persistence of dry anomalies.

Figure 7.

The maximum number of consecutive months satisfying compound extreme threshold values of 0, −0.5, −0.8 and−1.2 (given in Figure 6) for the reference (1995–2014) and the future periods (2040–2049 and 2070–2079) based on COSMO-CLM simulations at a resolution of 0.025°.

Under SSP3-7.0, the maximum consecutive duration of compound hot–dry months increases from the reference period to the 2040s and further into the 2070s across all thresholds. In the reference period, persistence already reaches 5–7 months for 0 threshold but becomes patchy and shorter at higher threshold values. On the other hand, these become longer and more spatially coherent by 2040s, and 4–7-month sequences become widespread, especially at moderate–strong thresholds of 0.5–0.8 by 2070s.

A slight decrease in the persistence of dry conditions is projected for each threshold value in some inland and western parts of the study region during 2040–2049 period. On the contrary, particularly the coastal orographic belts become hotspots with the most persistent sequences, advancing inland and upslope toward the 2070s. It is noteworthy that in the period 2070–2079, no matter how high the threshold is (even for 1.2), the number of consecutive months can reach up to 4 months in some regions. This progression from short, irregular events to multi-month sequences is consistent with stronger evaporative demand and reduced soil-moisture buffering. Such consecutive severe drought conditions lasting for long periods of 3–4 months significantly increase the risk of fire in forested areas.

The projected decline in soil moisture during warm periods, combined with greater reliance on winter rainfall, is expected to intensify summer droughts and moisture deficits. These conditions pose a serious threat to rain-fed agriculture and the potential for significant yield reduction is strongly indicated by established research. The combined temperature and precipitation decreases described in this study align with hydroclimatic stresses that have been shown to cause substantial losses, for instance, historical droughts and heatwaves have reduced global cereal production by 9–10% on average, with losses exceeding 40% in extreme events [70]. The warming-induced soil moisture depletion is a primary driver of yield loss in semiarid regions [71], and our scenario for the 2070s falls within the range of models projecting yield declines of 20–60% in Mediterranean climates [72]. The mechanism of increased evaporative demand highlighted in our findings is similarly identified as a key factor significantly raising the risk of crop failure in Southern Europe [73]. Therefore, the yield losses and quality declines for perennial crops are a plausible consequence of the intensifying temperature-soil moisture coupling and drought conditions documented in the literature [74].

In this case, the probability of drought increases across all levels. This indicates that in crop production in Western Anatolia, leading to yield fluctuations and potentially significant losses in some years. Especially in the long term (2070–2079), the probability of severe and very severe droughts nearly doubles. This makes drought-resistant crop and irrigation strategies crucial, as well as agricultural adaptation strategies. Moreover, these conditions impede the plants’ access to water, leading to premature wilting and crop failure, particularly in areas where precipitation is a primary source of hydration.

4. Conclusions

This is the inaugural study in Türkiye to employ a multivariate approach to comprehensively analyze historical and future drought conditions using COSMO-CLM (CCLM) simulations at convection-permitting scale. In doing so, we assess the impact of large-scale climate change (under SSP3-7.0) on hydroclimatic extremes and agricultural drought indices conditional on present-day land-surface characteristics. Because the regional climate model employs a fixed LULC map for all simulations, the projected changes in drought and extremes should therefore be interpreted as the response to climate forcing under constant land management, rather than as the full combined effect of climate change and plausible future land use trajectories. The objective of this study is to capture the complex interplay between various climate factors in southwestern Türkiye, which is critical in assessing impacts on agriculture. The projections are shown in two time slices of 10 years, 2040–2049, and 2070–2079. Our results, based on a single model chain (MPI-ESM-HR driven COSMO-CLM under the SSP3-7.0 scenario) suggest that CPM simulations over the land areas of the domain produce a slightly warmer and drier climate in the spring, and a slightly warmer and wetter climate in the summer, which in turn modulates soil-moisture and temperature anomalies and their co-variability.

The results indicate that compound drought–heat events are already an integral component of the present-day climate in western and southwestern Türkiye, particularly along coastal and orographic transition zones. These hotspots coincide with regions where SPI3 (or SSI) and STI exhibit strong negative correlation, reinforcing the notion that soil-moisture–temperature coupling is a key driver of compound extremes.

Correlation analysis reveals soil moisture as a critical mediator between temperature and precipitation. Topography strongly shapes these interactions: coastal and lowland zones amplify the negative SSI–STI coupling due to intense evaporative losses, while mountainous and plateau regions enhance the positive SSI–SPI3 coupling through orographic precipitation and basin hydrology. These results suggest that a gradual transformation of Türkiye’s drought regime from one primarily constrained by precipitation to one increasingly dictated by atmospheric energy availability and evaporative demand. However, future soil moisture variability particularly in topographically exposed lowlands, still controlled by precipitation anomalies, while warming acts as a secondary but amplifying stressor.

The joint probability analysis of soil moisture (SSI), temperature (STI), and precipitation (SPI3) anomalies reveals a pronounced intensification and spatial expansion of compound hot–dry events across southwest Türkiye throughout the 21st century. Mild compound anomalies are already a recurrent feature in the reference period, particularly along coastal and orographic transition zones, where strong negative SSI–STI correlations indicate robust land–atmosphere coupling. Under SSP3-7.0, both the frequency and spatial extent of moderate and severe compound events increase nonlinearly, and by 2070–2079 even the most extreme thresholds attain probabilities that were essentially zero historically. In parallel, as time progresses, especially during the period from 2070 to 2079, the area of the maximum number of consecutive months clearly expands especially along coastal orographic belts and adjacent mountain slopes, indicating an increase in both the duration and prevalence of these extreme events.

The combined analysis will provide enhanced insights into the evolution of agricultural drought under future climate scenarios, thereby yielding valuable information for adaptation strategies within the region. While these projections offer a physically consistent and detailed view of potential hydroclimatic changes, it is crucial to interpret them as conditional on the specific model and scenario employed. A primary limitation of this study is that the simulations rely on a single Earth System Model and a single emission scenario (SSP3-7.0), with only one set of initial and boundary conditions, which limits the representation of internal variability in the climate system, thereby, part of the projection uncertainty remains tied to the specific choice of forcing and model configuration, underscoring the need for future studies to extend this framework to multi-model, multi-scenario ensembles. The static LULC assumption is also constrains the scope of our experimental design. Nevertheless, treating land use as fixed provides a controlled framework to isolate and quantify the climate-driven component of future agricultural drought risk. A natural next step is to incorporate transient, scenario-consistent LULC projections in order to assess the combined effects of climate and land use change, and to evaluate the sensitivity of our results to alternative representations of land management in future model development and scenario analysis. Furthermore, the use of decadal slices, necessitated by the computational expense of convection-permitting modeling, provides a snapshot of potential future states rather than a continuous assessment of change.

Despite these constraints, the findings yield valuable, high-resolution information to develop a general approach to interpreting plant growth cycles and phenological changes, assessing their potential impacts on yield and product quality, and the implications of these effects for plant production. Development of specific plant patterns may be the subject of future studies.

The projected changes we report are supported by coherent spatial patterns, agreement across multiple drought indices, and consistency with current process-based understanding of hydroclimatic change in the Mediterranean, while we acknowledge that other models or scenarios might yield different magnitudes or details. The detailed insights into local-scale processes and compound event dynamics provide an essential foundation for future impact studies. Subsequent research should aim to embed such high-resolution dynamical downscaling within a multi-model ensemble approach to better quantify the uncertainties around the drought regime shift identified here, thereby strengthening the evidence base for regional climate resilience planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Ü.; methodology, Y.Ü. and C.Y.S.; software, C.Y.S., N.Y., B.K. and N.K.; validation, C.Y.S.; formal analysis, C.Y.S. and N.Y.; investigation, C.Y.S. and N.Y.; resources, C.Y.S. and N.Y.; data curation, C.Y.S., N.Y. and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.S., N.Y., L.B. and Y.Ü.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.S., N.K. and Y.Ü.; visualization, C.Y.S. and N.Y.; supervision, Y.Ü.; project administration, Y.Ü.; funding acquisition, Y.Ü. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by ACLIFS project number “TR2017 ESOP MI A3 04/CCAGP/206”, under the Climate Change Adaptation Grant Program (CCAGP).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to legal restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The computational resources and services used in this work were provided by Eduline and the National Center for High-Performance Computing (UHeM). We would like to express our profound gratitude to the Turkish State Meteorological Service for providing access to the observational data used in this study, and to CLM-Community and the German Weather Service (DWD) for the model and data provision. Their support was essential for conducting the analyses presented herein. This publication was produced within the scope of the project titled “ACLIFS—Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Food Safety and Enhancing the Resilience of Rural Communities” implemented under the “Climate Change Adaptation Grant Program (CCAGP)” with the financial support of the European Union and the Republic of Türkiye. The Directorate of Climate Change of the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change (MoEUCC) is responsible for the coordination of the technical implementation of the grant program and the Directorate General of European Union and Foreign Relations, Department of European Union Investments of the MoEUCC is the Contracting Authority of the Grant Program.” Contents of publication are the sole responsibility of Istanbul Technical University and Isparta University of Applied Sciences. It does not necessarily reflect the views of the Republic of Türkiye and the European Union.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wilhite, D.A.; Glantz, M.H. Understanding the drought phenomenon: The role of definitions. Water Int. 1985, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Meteorological Society. Statement on Meteorological Drought. American Meteorological Society. Available online: https://www.ametsoc.org/ams/index.cfm/about-ams/ams-statements/statements-of-the-ams-in-force/drought (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, W.C. Meteorological Drought (Research Paper No. 45); U.S. Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; Volume 17, pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Reig, F.; Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: Parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 3001–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungul, V.; Nowbuth, M.D. Comparative study of SPI and SPEI drought indices for meteorological drought assessment in Mauritius. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2025, 17, a1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskander, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. (Eds.) Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Tramblay, Y.; Reig, F.; González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Beguería, S.; Brunetti, M.; Kalin, K.C.; Patalen, L.; Kržič, A.; Lionello, P.; et al. High temporal variability not trend dominates Mediterranean precipitation. Nature 2025, 639, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, İ. Orta Doğu’da Su Sorunları ve Türkiye; Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu: Ankara, Türkiye, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Change 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, U.; Lionello, P.; Belušić, D.; Jacobeit, J.; Knippertz, P.; Kuglitsch, F.G.; Leckebusch, G.C.; Luterbacher, J.; Maugeri, M.; Maheras, P.; et al. 5-Climate of the Mediterranean: Synoptic Patterns, Temperature, Precipitation, Winds, and Their Extremes. In The Climate of the Mediterranean Region; Lionello, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 301–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, Ö.L.; Bozkurt, D.; Göktürk, O.M.; Dündar, B.; Altürk, B. Türkiye’de iklim değişikliği ve olası etkileri. Taşkın Sempozyumu 2013, 29, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Önol, B.; Ünal, Y.S.; Dalfes, H.N. İklim değişimi senaryosunun Türkiye üzerindeki etkilerinin modellenmesi. İTÜDERGİSİ/d 2009, 8, 169–177. Available online: https://search.trdizin.gov.tr/en/yayin/detay/93806/iklim-degisimi-senaryosunun-turkiye-uzerindeki-etkilerinin-modellenmesi (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Önol, B.; Unal, Y.S. Assessment of climate change simulations over climate zones of Turkey. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 1921–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunçoğlu, U.U.; Türkeş, M.; Bozkurt, D.; Önol, B.; Şen, Ö.L.; Dalfes, H.N. Climate. In The Soils of Turkey; World Soils Book Series; Kapur, S., Akça, E., Günal, H., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, M.B.; Batibeniz, F.; Önol, B. Exposure assessment of climate extremes over the Europe-Mediterranean region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilköy, S.; Şaylan, L. Spatial and temporal drought projections of northwestern Turkey. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 149, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraç, S.; Doğan, M. İklim değişikliğinin Türkiye tarımı üzerindeki etkileri: Çiftçi algıları ve uyum stratejileri. Ege Üniv. Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2016, 53, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Danandeh Mehr, A.; Vaheddoost, B. Identification of the trends associated with the SPI and SPEI indices across Ankara, Turkey. Theor Appl Climatol. 2020, 139, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapan, N. Assesment of Drought in a Future Climate over Turkey with COSMO-CLM. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Serkendiz, H.; Tatli, H.; Kılıç, A.; Çetin, M.; Sungur, A. Analysis of drought intensity, frequency and trends using the spei in Turkey. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 2997–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soydan Oksal, E. Drought assessment using SPI and SPEI indices in the Mediterranean Basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Türkeş, M.; Tatlı, H. Türkiye’de meteorolojik kuraklıkların mekânsal ve zamansal değişimi. Türk Coğraf. Derg. 2009, 53, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yerdelen, C.; Abdelkader, M.; Eris, E. Assessment of drought in SPI series using continuous wavelet analysis for Gediz Basin, Turkey. Atmos. Res. 2021, 260, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıkulu, A.; Guner, U.; Bahar, E. The assessment of precipitation and droughts in the Aegean region using stochastic time series and standardized precipitation index. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyraz, A.Y. Drought Analysis Using CORDEX Simulations over the Mediterranean Climate Regions of Turkey. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Öz, F.Y.; Özelkan, E.; Tatlı, H. Comparative analysis of SPI, SPEI, and RDI indices for assessing spatio-temporal variation of drought in Türkiye. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 4473–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Nicholls, N.; Easterling, D.; Goodess, C.M.; Kanae, S.; Kossin, J.; Luo, Y.; Marengo, J.; McInnes, K.; Rahimi, M.; et al. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2012, 3, 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zou, Y.; Yao, R.; Ma, Z.; Bian, Y.; Ge, C.; Lv, Y. Compound and successive events of extreme precipitation and extreme runoff under heatwaves based on CMIP6 models. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 162980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpuri, M.; Das, J.; Umamahesh, N.V. Spatio-temporal compounding of connected extreme events: Projection and hotspot identification. Environ. Res. 2023, 235, 116615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Y.; Forzieri, G. Projected increase in global compound agricultural drought and hot events under climate change. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 253, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; AghaKouchak, A. Multivariate standardized drought index: A parametric multi-index model. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 57, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Hao, F.; Singh, V.P.; Xia, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhang, X. A multivariate approach for statistical assessments of compound extremes. J. Hydrol. 2018, 565, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, İ. Türkiye’nin Ekolojik Bölgeleri; Ege Üniversitesi Yayınları: Izmir, Türkiye, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Eken, G.; Bozdoğan, M.; İsfendiyaroğlu, S.; Kılıç, D.T.; Lise, Y. Türkiye’nin Önemli Doğa Alanları; Doğa Derneği: Ankara, Türkiye, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MGM. Türkiye İklim Verileri; Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Geobotanical Foundations of the Middle East; Gustav Fischer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Erinç, S.; Tunçdilek, N. Türkiye’nin İklim Özellikleri; İstanbul Üniversitesi Coğrafya Enstitüsü Yayınları: Istanbul, Türkiye, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Agro-Ecological Zones; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, Y. Ekolojik Coğrafya ve Türkiye Vejetasyon Bölgeleri; Palme Yayıncılık: Ankara, Türkiye, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, U.; Kücken, M.; Ahrens, W.; Block, A.; Hauffe, D.; Keuler, K.; Rockel, B.; Will, A. CLM—The climate version of LM: Brief description and long-term applications. COSMO Newsl. 2006, 6, 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rockel, B.; Will, A.; Hense, A. The Regional Climate Model COSMO-CLM (CCLM). Meteorol. Z. 2008, 17, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Tebaldi, C.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Eyring, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hurtt, G.; Knutti, R.; Kriegler, E.; Lamarque, J.F.; Lowe, J.; et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 3461–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausfather, Z.; Peters, G.P. RCP8.5 is a problematic scenario for near-term emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27791–27792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağçaci, S.Ç.; Yücel, İ.; Düzenli, E.; Yilmaz, M.T. Intercomparison of the expected change in the temperature and the precipitation retrieved from CMIP6 and CMIP5 climate projections: A Mediterranean hot spot case, Turkey. Atmos. Res. 2021, 256, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedtke, M. A Comprehensive Mass Flux Scheme for Cumulus Parameterization in Large-Scale Models. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1989, 117, 1779–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]