Microtopography-Driven Soil Loss in Loess Slopes Based on Surface Heterogeneity with BPNN Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

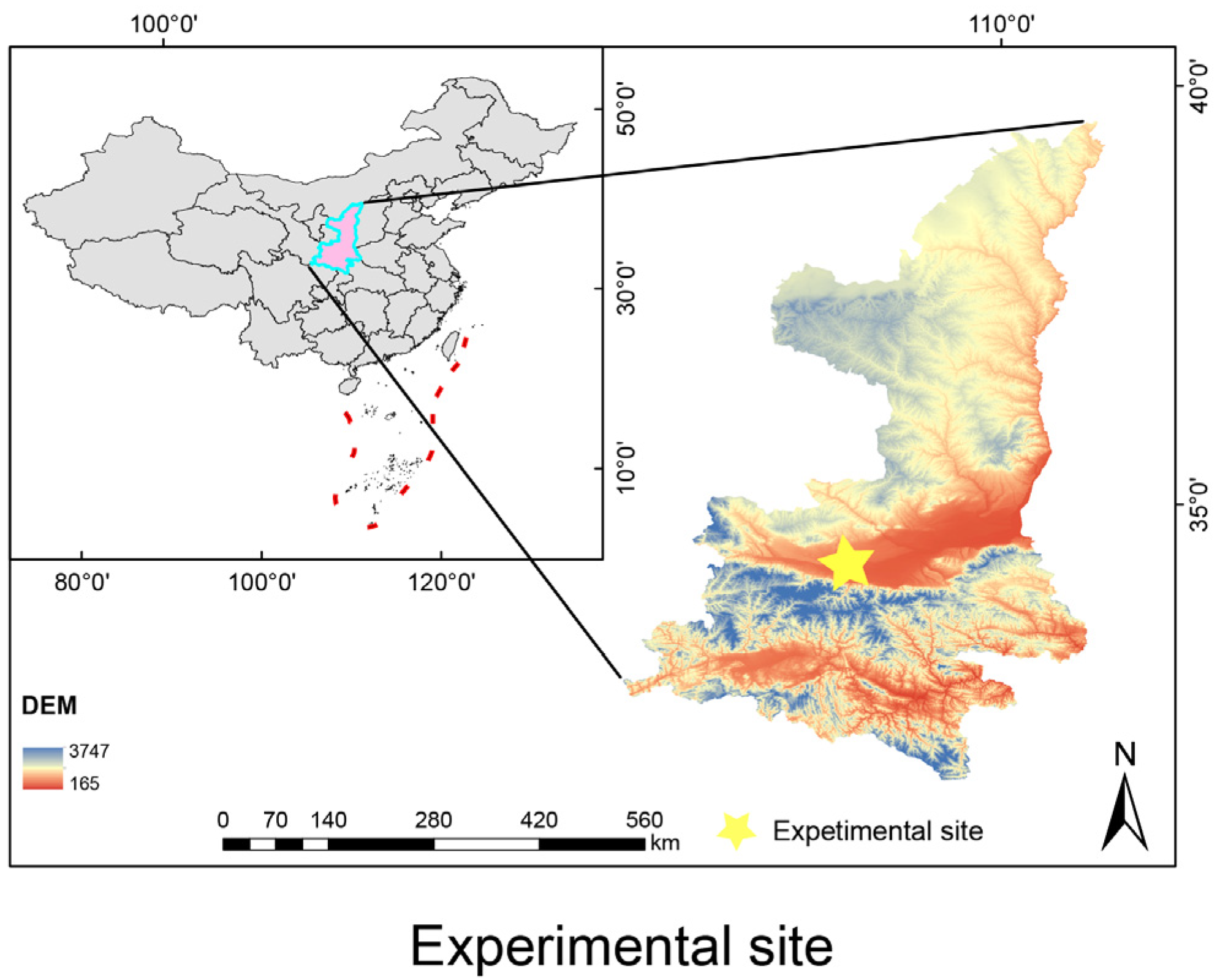

2.1.1. Experimental Area and Soil

2.1.2. Experimental Device

2.2. Methods

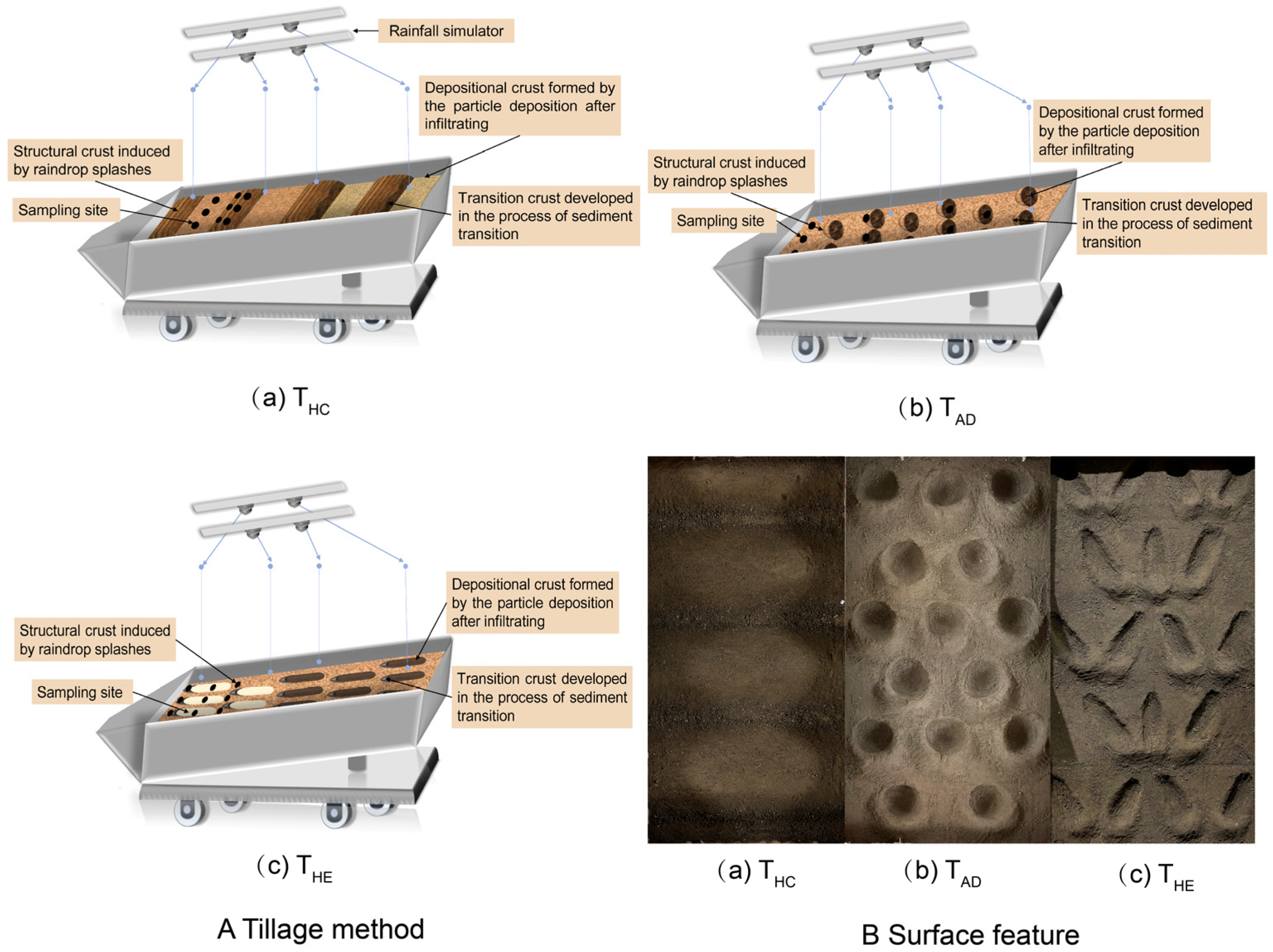

2.2.1. Experimental Design

2.2.2. Measurements and Data Processing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Surface Heterogeneity Under Diverse Erosion Processes

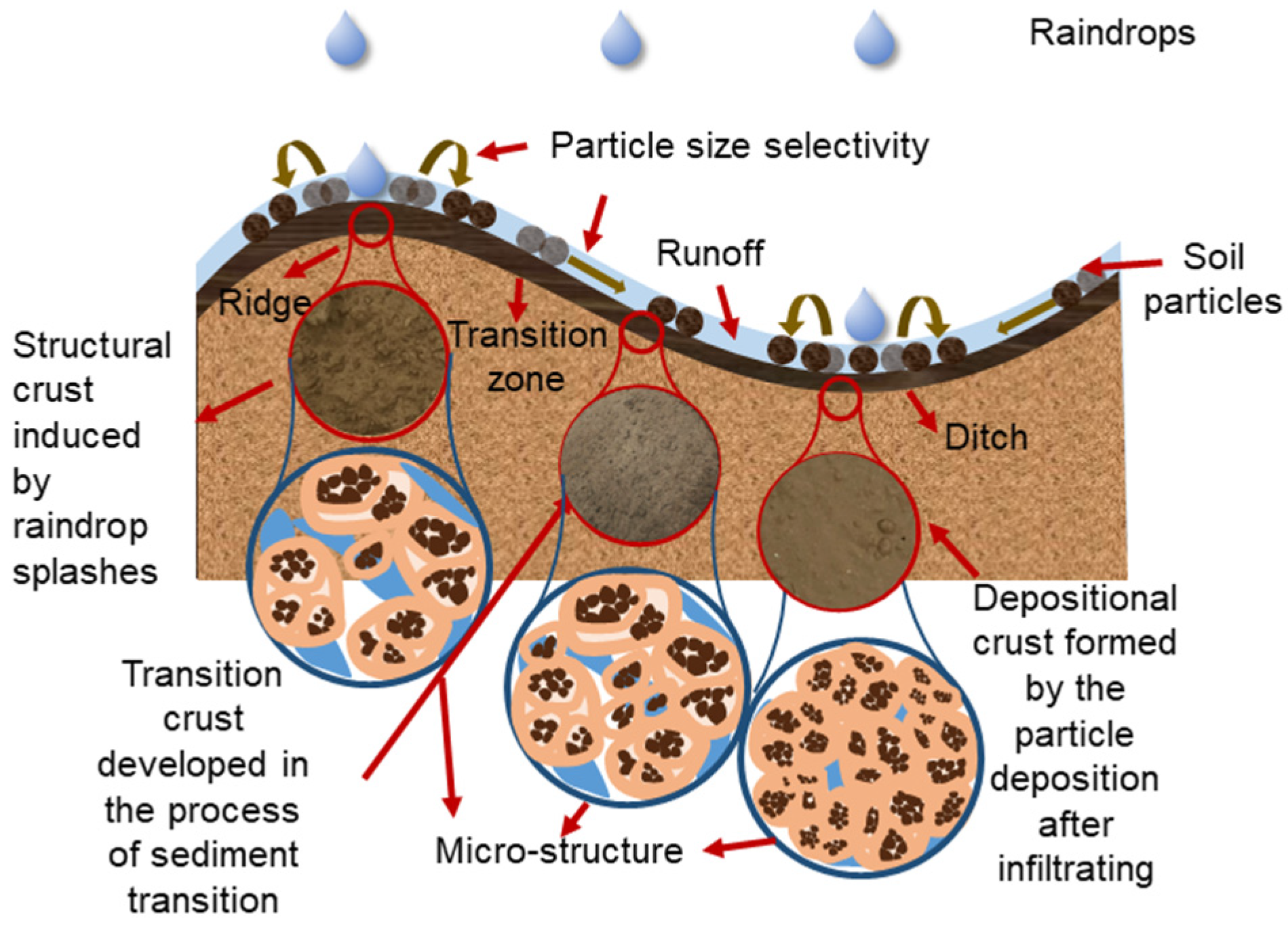

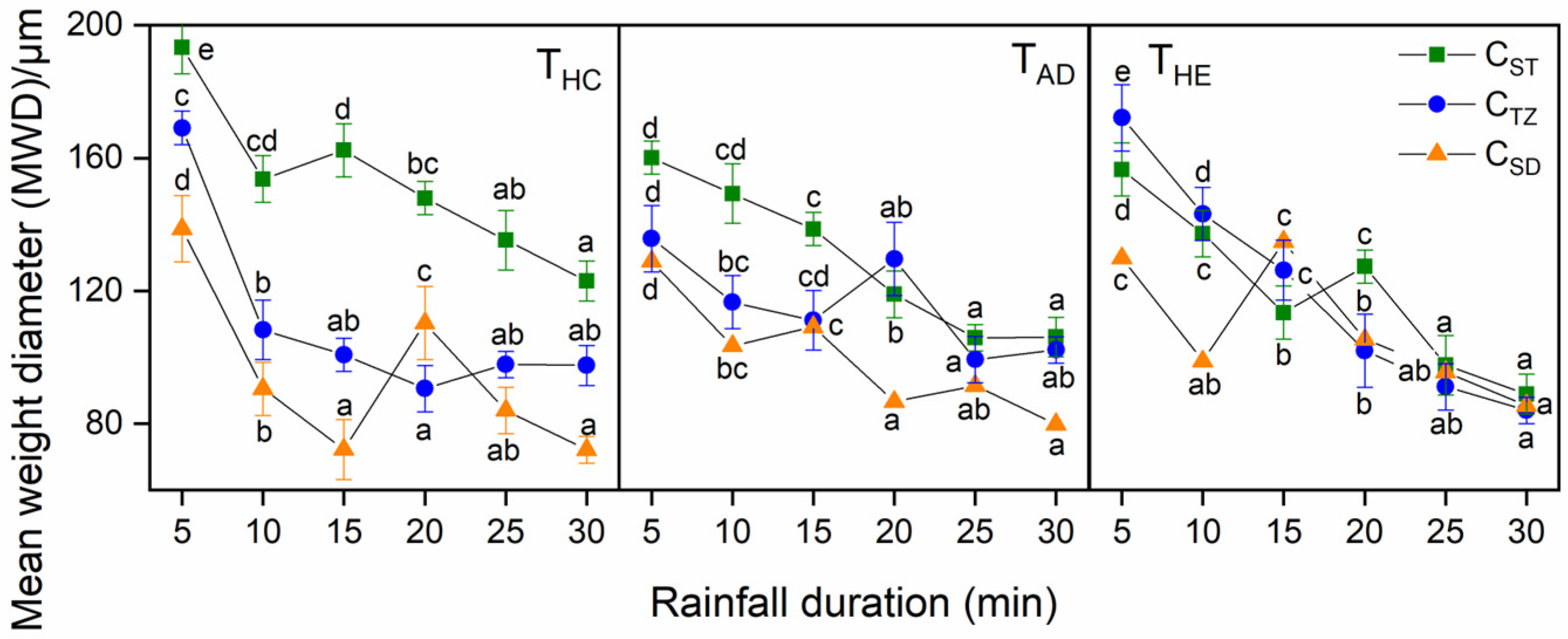

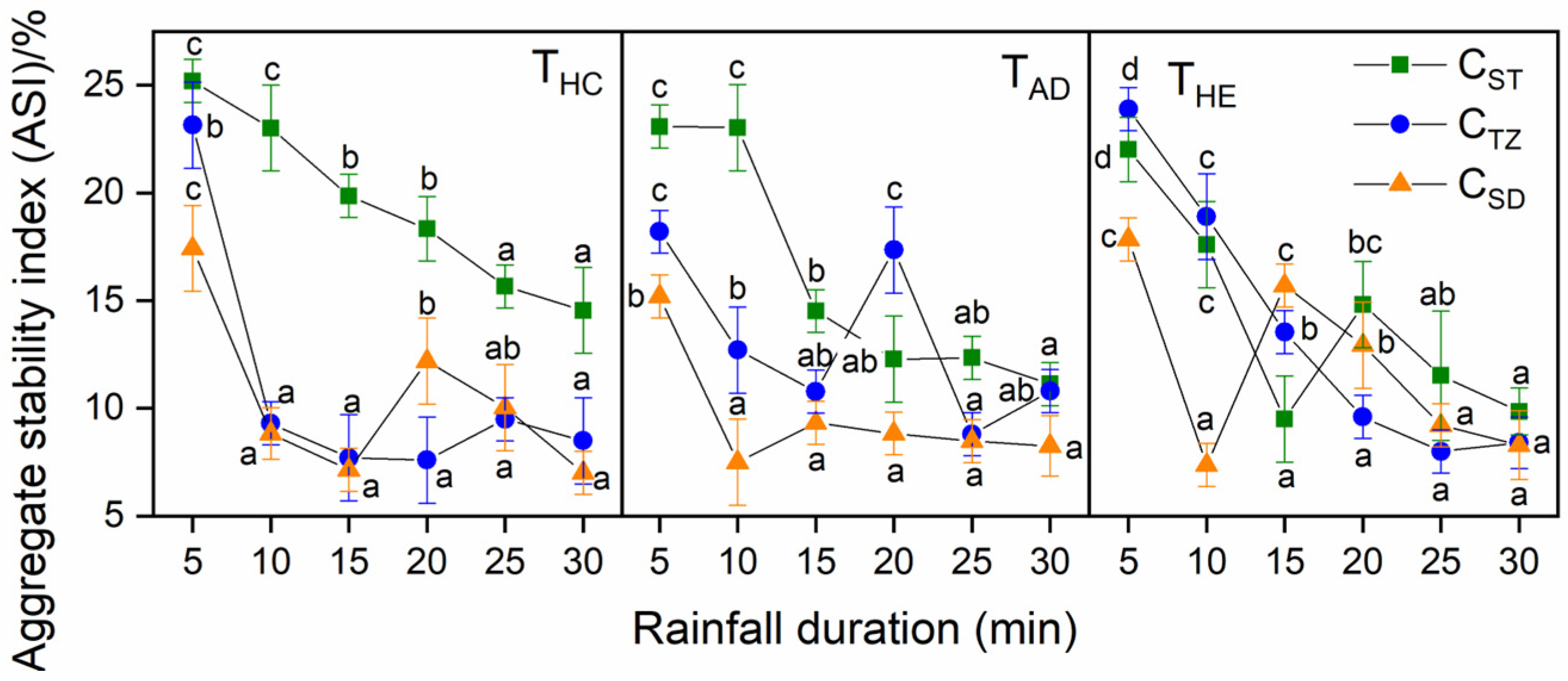

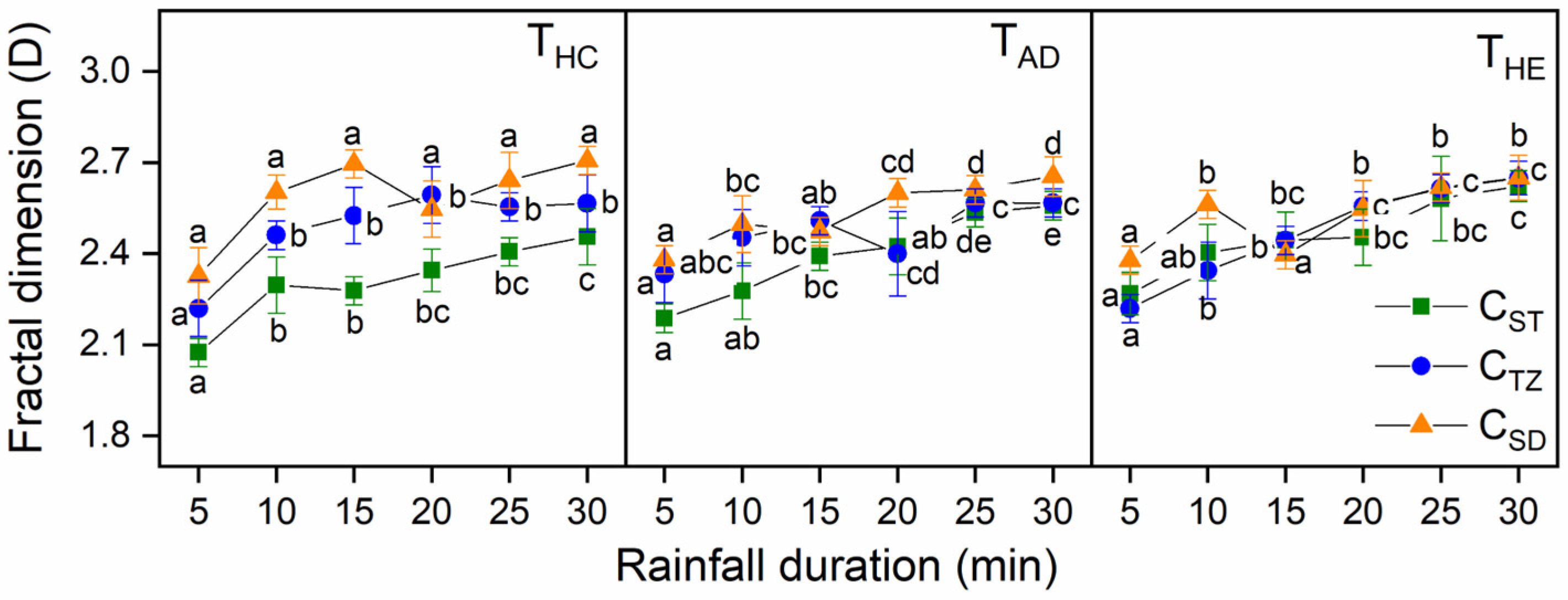

3.1.1. Surface Microstructure and Stability

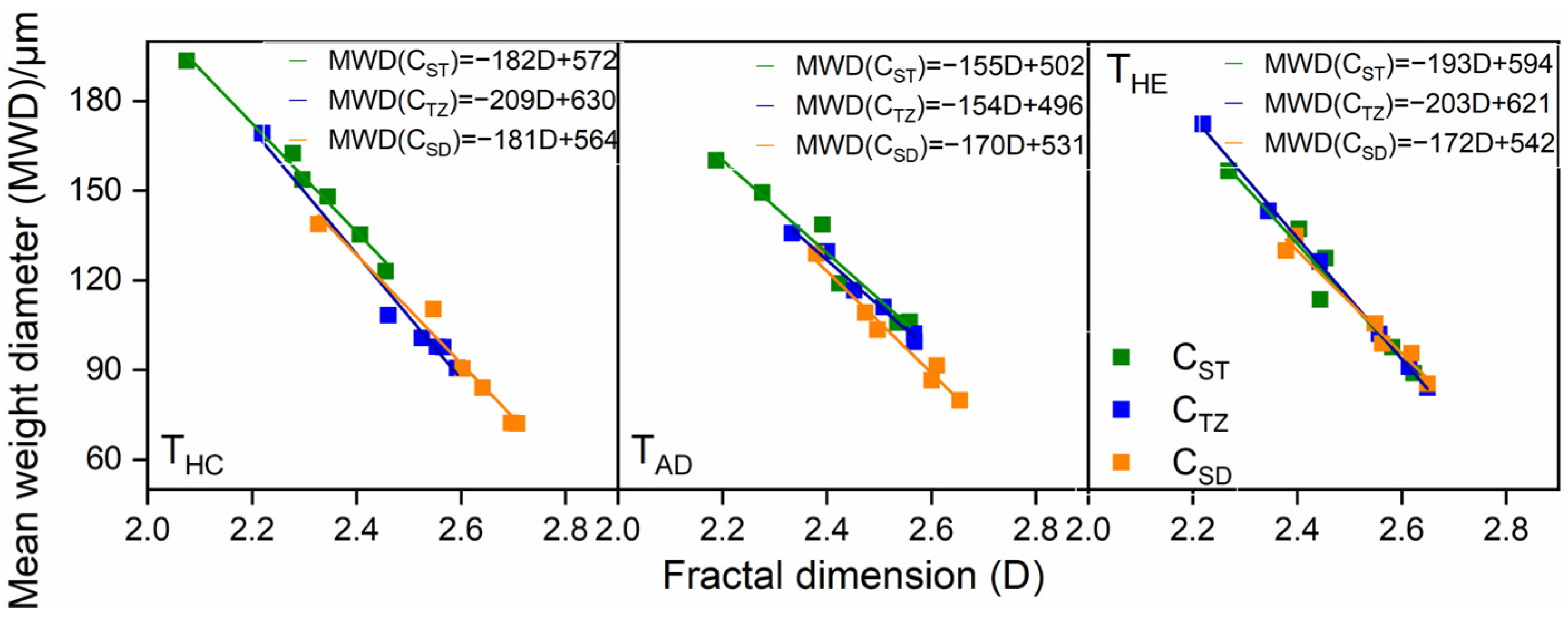

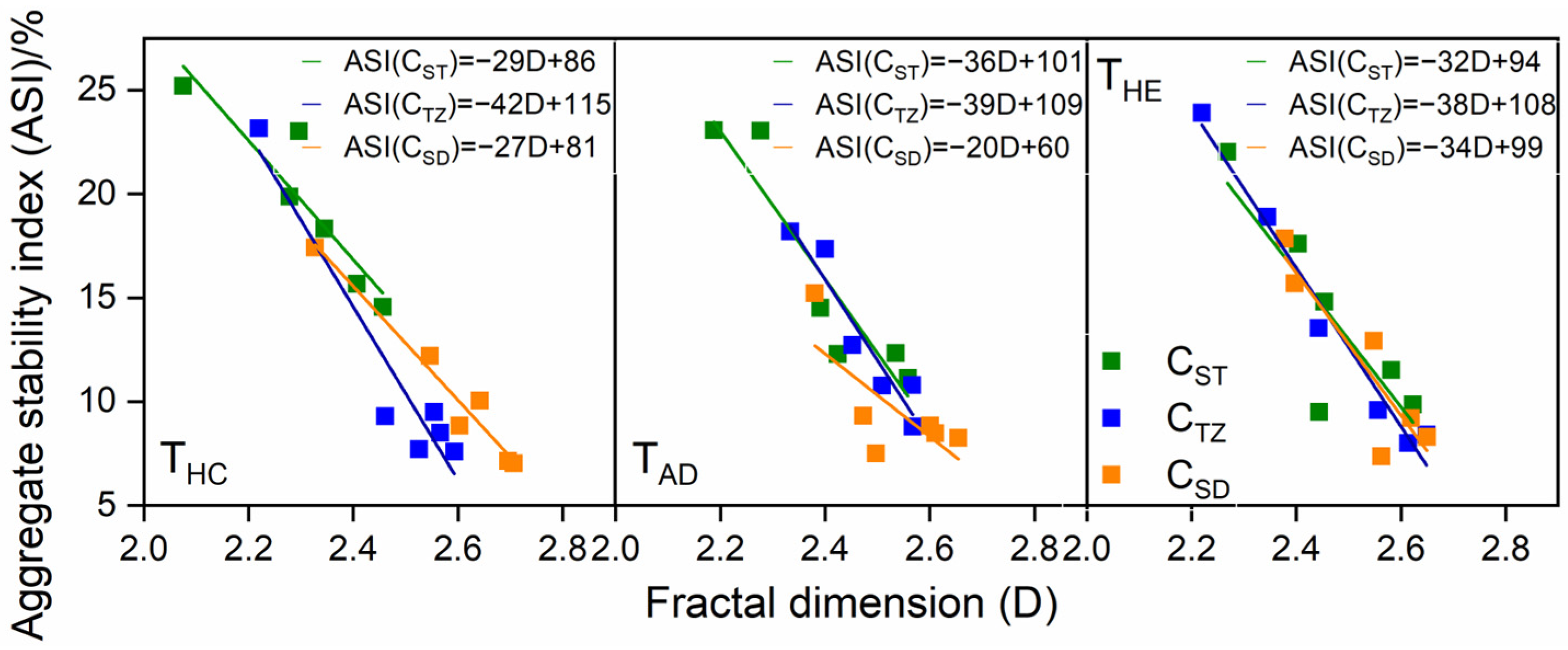

3.1.2. Fracture Feature of Surface Aggregates

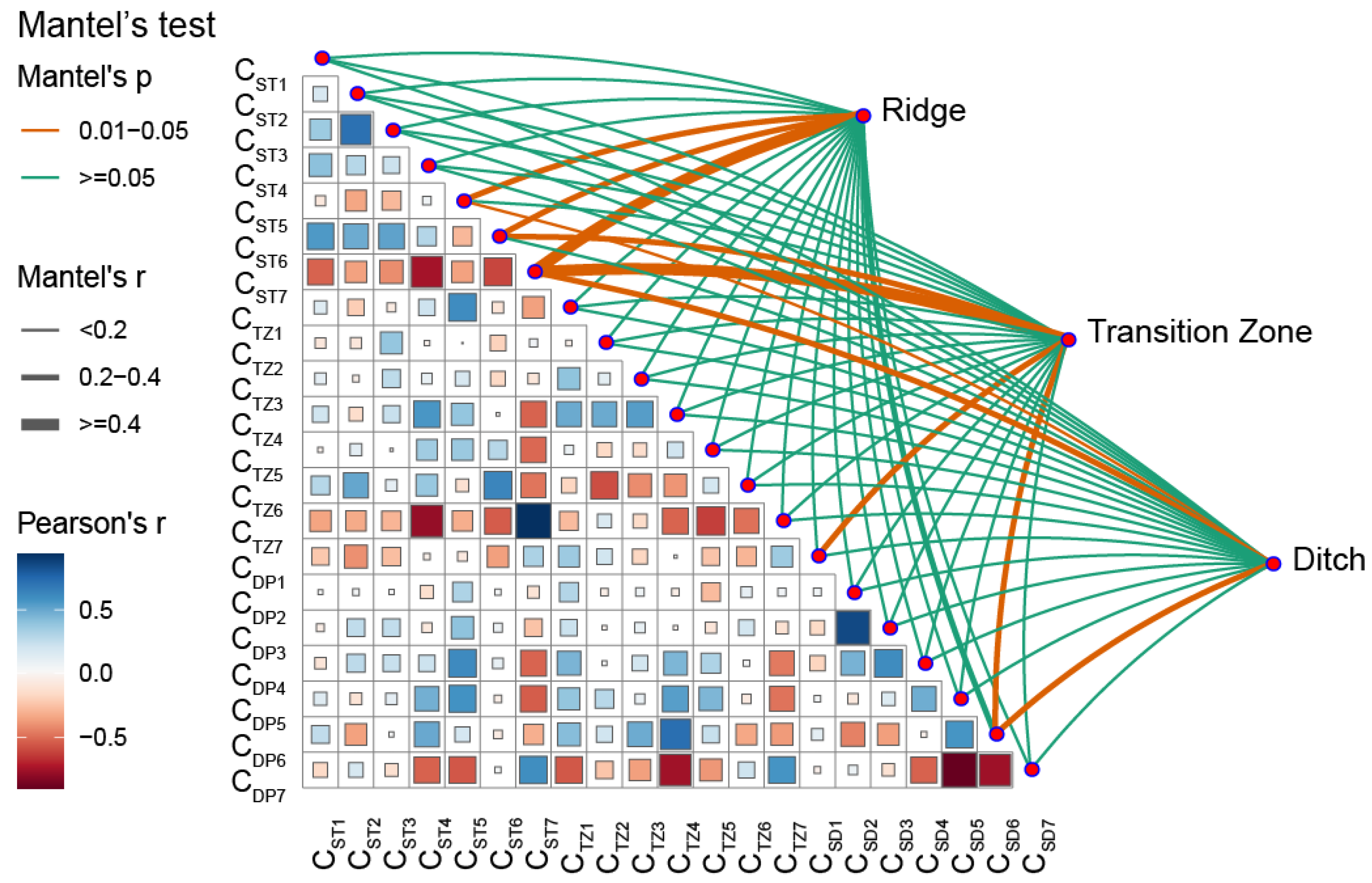

3.2. Impact of Micro-Terrain on Surface Heterogeneity

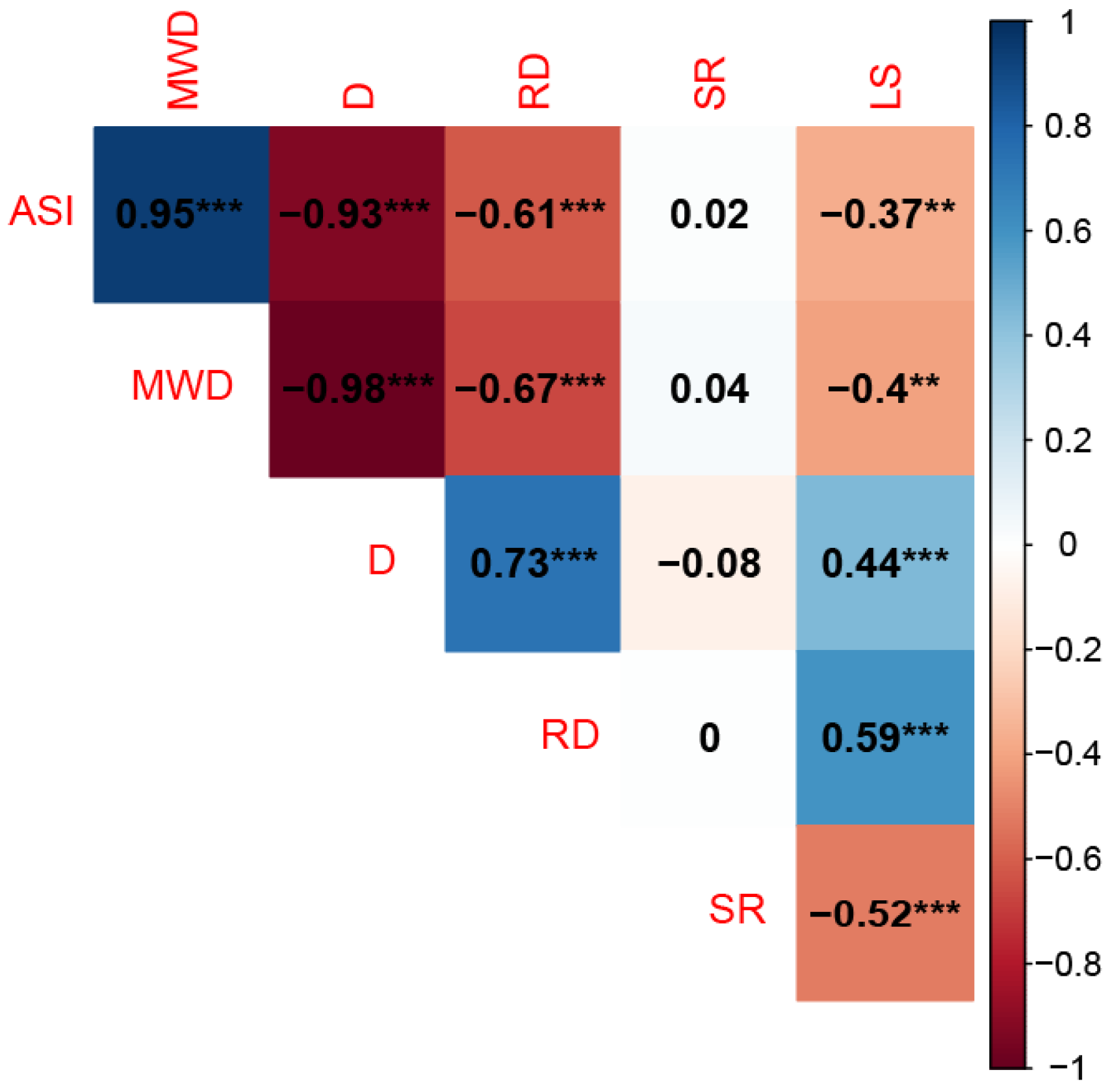

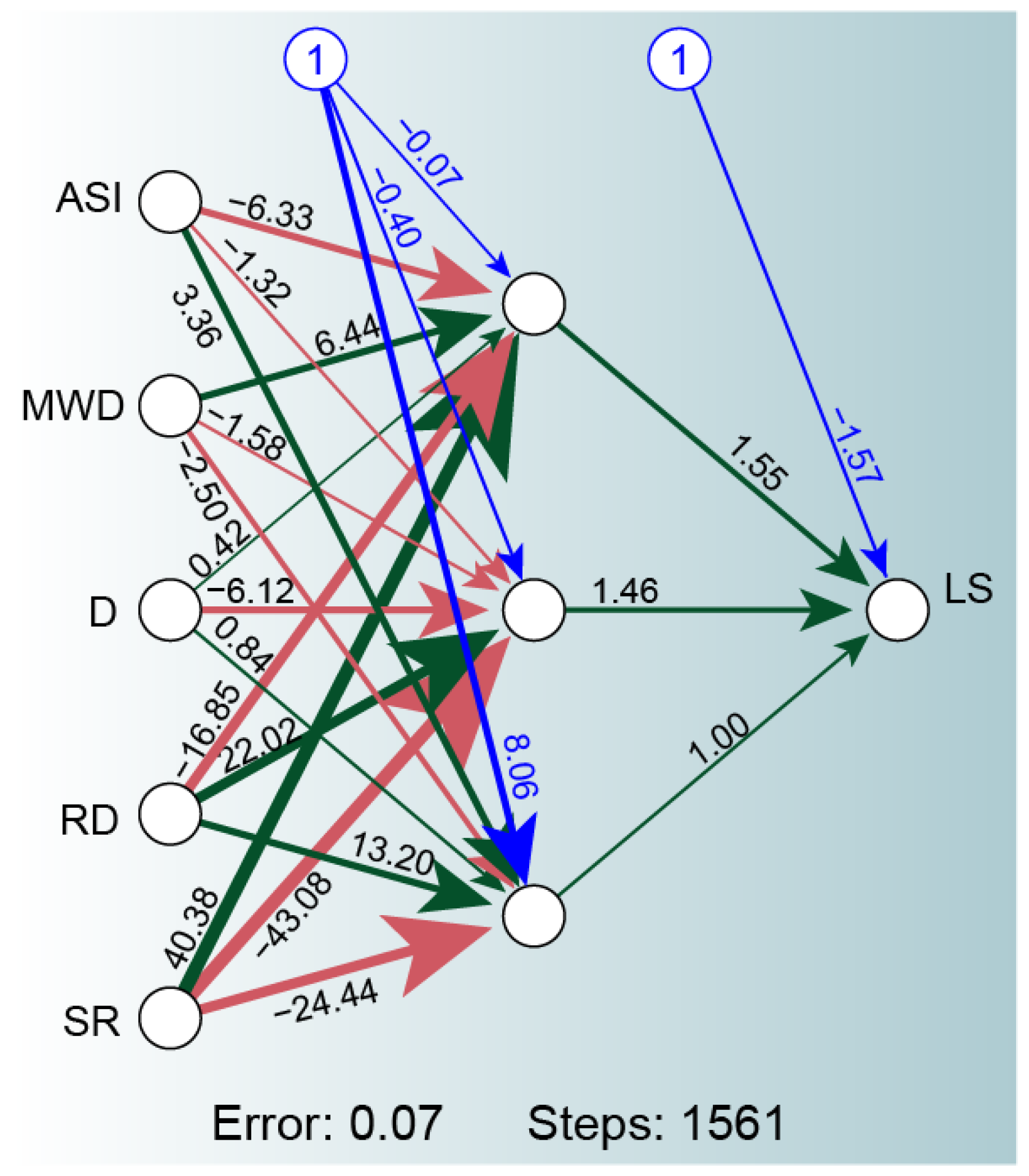

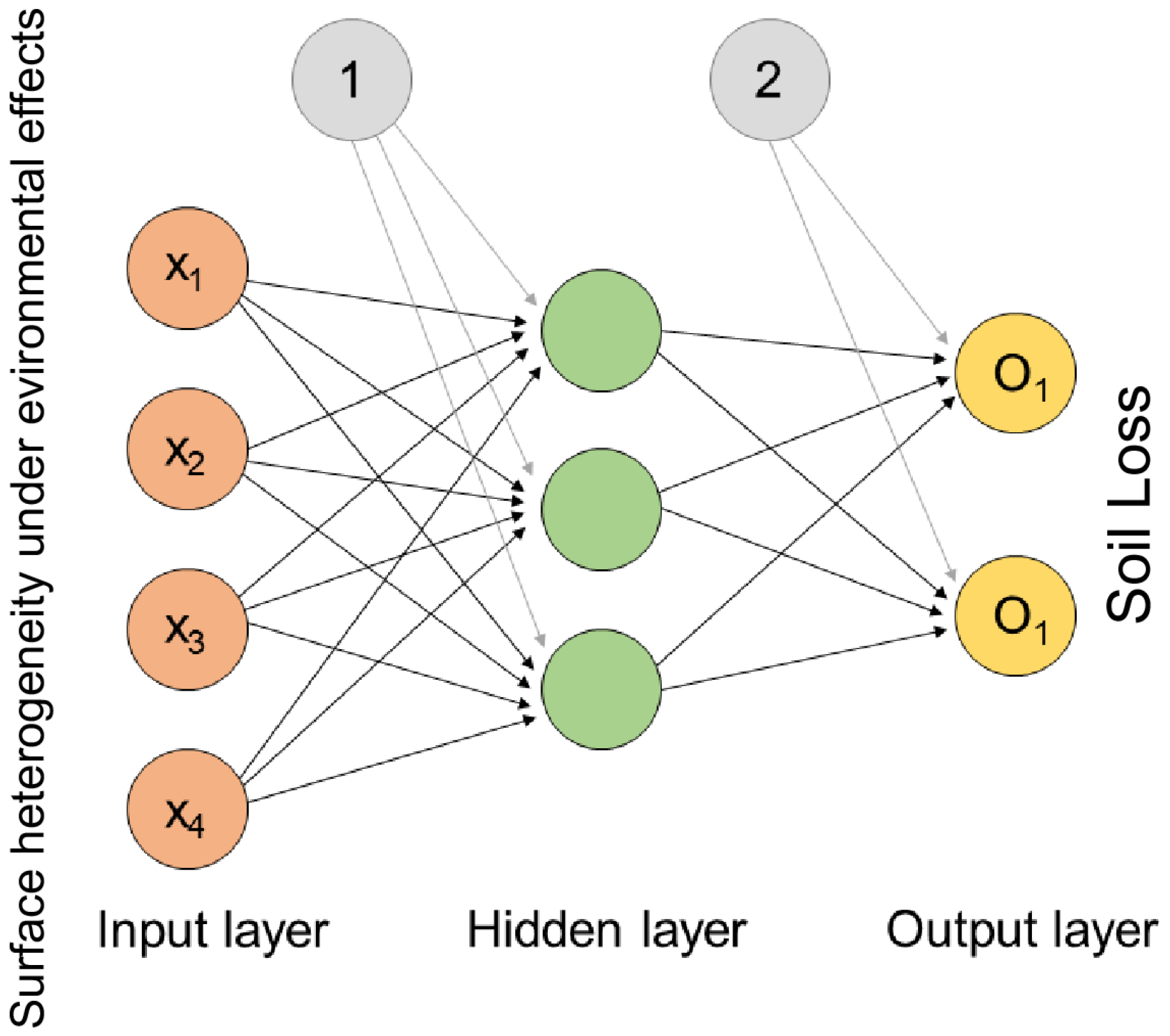

3.3. Response of Soil Loss of Spatial Heterogeneity Under BPNN

4. Discussion

4.1. Surface Heterogeneity Evolution Under Microtopography

4.2. Response of Soil Loss to Surface Spatial Heterogeneity

4.3. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RD | Rainfall Duration |

| SR | Surface Roughness |

| ADS | Average Depression Storage |

| THC | Horizontal Cultivation |

| THE | Hoeing Cultivation |

| TAD | Artificial Digging |

| CST | Structural Crust |

| CSD | Depositional Crust |

| CTZ | Transition Crust |

| LS | Soil Loss |

| ASI | Aggregate Stability Index |

| MWD | Mean Weight Diameter |

| D | Fractal Dimension |

| BPNN | Backpropagation Neural Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| Cv | Coefficient of Variation |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| MVS | Multi-View Stereo |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

References

- He, T.; Yang, Y.; Peng, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B. The role of straw mulching in shaping rills and stabilizing rill network under simulated extreme rainfall. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 229, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Wang, B.; Duan, X.W.; Yang, Y.F.; Liu, G.B. Seasonal variation in soil erosion resistance to overland flow in gully-filled farmland on the Loess Plateau, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 218, 105297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puustinen, M.; Koskiaho, J.; Peltonen, K. Influence of cultivation methods on suspended solids and phosphorus concentrations in surface runoff on clayey sloped fields in boreal climate. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.Y.; Peng, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.G.; Cai, C.F. Splash erosion-induced soil aggregate turnover and associated organic carbon dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zheng, Z.; Li, T.; He, S.; Wang, Y.D. Quantifying the contributions of soil surface microtopography and sediment concentration to rill erosion. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, F.; Kisic, I.; Mesic, M.; Nestroy, O.; Butorac, A. Tillage and crop management effects on soil erosion in central Croatia. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 78, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.C.; He, S.Q.; Wu, F.Q. Changes of soil surface roughness under water erosion process. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 3919–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.N.; Xu, C.Y.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; He, X. Particles interaction forces and their effects on soil aggregates breakdown. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 147, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Chen, L.; Li, J.C.; Singh, V.P. Two-dimensional kinematic wave model of overland-flow. J. Hydrol. 2004, 291, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.J.; Zhang, J.H. Variation of chemical properties as affected by soil erosion on hillslopes and terraces. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.F.; Wu, F.Q. Runoff, erosion, and sediment particle size from smooth and rough soil surfaces under steady rainfall-runoff conditions. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2014, 64, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Shen, N.; Ke, Z.; Tian, N.; Wu, B.; Liu, J. Size-selective characteristics of splash-detached sediments and their responses to related parameters on steep slopes in Chinese loessial region. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 198, 104539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, Q.W.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Lu, C.; Wu, F.Q. Effects of tillage microrelief units on splash erosion: A case study from the Loess Plateau, in China. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 238, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenise, E.; Simmons, R.W.; Ahn, S.; Garbout, A.; Doerr, S.H.; Mooney, S.J.; Sturrock, C.J.; Ritz, K. Soil seal development under simulated rainfall: Structural, physical and hydrological dynamics. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, S. Rainfall-induced soil surface sealing: A critical review of observations, conceptual models, and solutions. Vadose Zone J. 2004, 3, 570–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, X.J.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Z.B.; Dong, Y.; Peng, X.H. Drying-wetting cycles affect soil structure by impacting soil aggregate transformations and soil organic carbon fractions. Catena 2024, 243, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, E.M.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil aggregate isolation method affects measures of intra-aggregate extracellular enzyme activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 69, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolo, C.C.; Gebresamuel, G.; Zenebe, A.; Haile, M.; Eze, P.N. Accumulation of organic carbon in various soil aggregate sizes under different land use systems in a semi-arid environment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 297, 106924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikha, M.M.; Green, T.R.; Untiedt, T.J.; Hergret, G.W. Land management affects soil structural stability: Multi-index principal component analyses of treatment interactions. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikha, M.M.; Hergert, G.W.; Benjamin, J.G.; Jabro, J.D.; Nielsen, R.A. Long-term manure impacts on soil aggregates and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremenfeld, S.; Fiener, P.; Govers, G. Effects of interrill erosion, soil crusting and soil aggregate breakdown on in situ CO effluxes. Catena 2013, 104, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseiny, A.M.; Salem, H.M.S. Soil surface seal induced by rainfall and its effect on properties of soil of the northwestern coast of Egypt. Ann. Agric. Sci. Moshtohor 2018, 56, 1105. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Xie, X.L.; Wang, L.H.; Wu, F.Q. Effects of different spatial distributions of physical soil crusts on runoff and erosion on the loess plateau in China. Earth Surf. Proc. Land 2017, 42, 2082–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, C.; Bresson, L.M. Morphology, genesis, and classification of surface crusts in loamy and sandy soils. Geoderma 1992, 55, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, W. Soil organic carbon and soil aggregate stability associated with aggregate fractions in a chronosequence of citrus orchards plantations. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, H.M. Application of fractal theory in quantifying soil aggregate stability as influenced by varying tillage practices and cover crops in northern guinea savanna, Nigeria. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2022, 25, #025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, G.; Zheng, T.; Li, B.; Zhang, T. Impact of raindrop characteristics on the selective detachment and transport of aggregate fragments in the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2016, 80, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.T.; Xu, Q.; Wu, F.Q.; Li, T.T. Effects of wheat in regulating runoff and sediment on different slope gradients and under different rainfall intensities. Catena 2019, 183, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserloh, T.; Ries, J.; Cerdà, A.; Echeverría, M.; Fister, W.; Geißler, C.; Kuhn, N.; León, F.; Peters, P.; Schindewolf, M.; et al. Comparative measurements with seven rainfall simulators on uniform bare fallow land. Z. Geomorphol. 2012, 57, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphorst, E.C.; Jetten, V.; Guérif, J.; Pitkänen, J.; Iversen, B.V.; Douglas, J.T.; Paz, A. Predicting depressional storage from soil surface roughness. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, R.E. A direct method of aggregate analysis of soils and a study of the physical nature of erosion losses. J. Am. Soc. Agron. 1936, 28, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Loss, A.; Piccolo, M.d.C.; Girotto, E.; Ludwig, M.P.; Decarli, J.; Torres, J.L.R.; Brunetto, G. Aggregation index and carbon and nitrogen contents in aggregates of pasture soils under successive applications of pig slurry in southern Brazil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagar, A.A.; Adamowski, J.; Memon, M.S.; Do, M.C.; Mashori, A.S.; Soomro, A.S.; Bhayo, W.A. Soil fragmentation and aggregate stability as affected by conventional tillage implements and relations with fractal dimensions. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gryze, S.; Six, J.; Merckx, R. Quantifying water-stable soil aggregate turnover and its implication for soil organic matter dynamics in a model study. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2006, 57, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsone, G.; Bonifacio, E.; Zanini, E. Structure development in aggregates of poorly developed soils through the analysis of the pore system. Catena 2012, 95, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Wan, F.T.; Hong, Q.H.; Chong, F.C.; Ming, K.W. Distribution of organic matter in aggregates of eroded Ultisols, Central China. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 108, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinska, E.; Wetzel, H.; Baumgartl, T.; Horn, R. Heterogeneity of physico-chemical properties in structured soils and its consequences. Pedosphere 2006, 16, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legout, C.; Leguedois, S.; Le Bissonnais, Y. Aggregate breakdown dynamics under rainfall compared with aggregate stability measurements. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2005, 56, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Thorlacius, S.; Keller, T.; Schulin, R. Soil aggregate breakdown in a field experiment with different rainfall intensities and initial soil water contents. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinia, M.; Saleh, F.N.; Asadi, H. Effects of rainfall patterns on runoff and rainfall-induced erosion. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 34, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Zara, R.; Abadi, V.A.J.M. Application of fractal theory to quantify structure from some soil orders in Fars Province. J. Water Soil Sci. 2017, 31, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Hairsine, P.B.; Rose, C.W. Modeling water erosion due to overland flow using physical principles: 1 Sheet flow. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliho, M.; Nouira, A.; Benmansour, M.; Boulmane, M.; Benkdad, A. Assessment of soil erosion rates in a Mediterranean cultivated and uncultivated soils using fallout 137Cs. J. Environ. Radioact. 2019, 208, 106021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, O.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Govers, G.; Lecomte, V.; Oost, K.V.; Couturier, A.; King, C.; Dubreuil, N. Scale effect on runoff from experimental plots to catchments in agricultural areas in Normandy. J. Hydrol. 2004, 299, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darboux, F.; Huang, C. Does soil surface roughness increase or decrease water and particle transfers? Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, W.; Klik, A. Soil surface roughness measurement—Methods, applicability, and surface representation. Catena 2005, 64, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, G.; Takken, I.; Helming, K. Soil roughness and overland flow. Agronomie 2000, 20, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampurlanes, J.; Cantero-Martinez, C. Hydraulic conductivity, residue cover and soil surface roughness under different tillage systems in semiarid conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 85, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, A.N.; Abban, B.K.; Dermisis, D.C.; Giannopoulos, C.P.; Flanagan, D.C.; Frankenberger, J.R.; Wacha, K.M. Flow resistance interactions on hillslopes with heterogeneous attributes: Effects on runoff hydrograph characteristics. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J.A.; Hodgkinson, R.A.; Bates, A.; Withers, C.L. Soil cultivation effects on sediment and phosphorus mobilization on surface runoff for three contrasting soil types in England. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 93, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronick, C.J.; Lal, R. Manuring and rotation effects on soil organic carbon concentration for different aggregate size fractions on two soils in northeastern Ohio, USA. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 81, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Woodun, J.K. An experimental study of crust development on chalk downland soils and their impact on runoff and erosion. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2008, 59, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, G.H.; Zhang, X.C.; Li, Z.W.; Su, Z.L.; Yi, T.; Shi, Y.Y. Effects of Near Soil Surface Characteristics on Soil Detachment by Overland Flow in a Natural Succession Grassland. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, D.N.; Mamedov, A.I.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Levy, G.J. Primary particle size distribution of eroded material affected by degree of aggregate slaking and seal development. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Anderson, K.; Brazier, R.E.; Kuhn, N.J. Modeling fine-scale soil surface structure using geostatistics. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 1858–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciizah, A.D.; Wakindiki, I.I.C. Soil sealing and crusting effects on infiltration rate: A critical review of shortfalls in prediction models and solutions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2015, 61, 1211–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liang, X.; Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Bol, R. Enhanced soil aggregate stability limits colloidal phosphorus loss potentials in agricultural systems. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tillage Method | Formula | R2 | Formula | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THC | ASI = −33.4D + 95.7 | 0.89 | MWD = −200.6D + 612.9 | 0.98 |

| TAD | ASI = −35.3D + 100.0 | 0.83 | MWD = −171.1D + 537.4 | 0.96 |

| THE | ASI = −35.7D + 102.0 | 0.97 | MWD = −193.1D + 596.2 | 0.98 |

| Tillage Method | SR | SD | Cv | ADS (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THC | 1.76 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 2.34 × 10−2 |

| TAD | 1.66 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 2.77 × 10−3 |

| THE | 1.47 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 3.23 × 10−4 |

| Model | MSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) | 0.07 | 0.89 |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.12 | 0.81 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.15 | 0.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Song, Y.; Lin, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, J. Microtopography-Driven Soil Loss in Loess Slopes Based on Surface Heterogeneity with BPNN Prediction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242602

Chen L, Song Y, Lin J, Meng Q, Wang J. Microtopography-Driven Soil Loss in Loess Slopes Based on Surface Heterogeneity with BPNN Prediction. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242602

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lin, Yiting Song, Jie Lin, Qinqian Meng, and Jian Wang. 2025. "Microtopography-Driven Soil Loss in Loess Slopes Based on Surface Heterogeneity with BPNN Prediction" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242602

APA StyleChen, L., Song, Y., Lin, J., Meng, Q., & Wang, J. (2025). Microtopography-Driven Soil Loss in Loess Slopes Based on Surface Heterogeneity with BPNN Prediction. Agriculture, 15(24), 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242602