Abstract

Sansevieria, a perennial herb known for its ornamental and medicinal value, has many varieties due to its leaf size and stripe color. However, it is very difficult to distinguish them during the seedling stage. In this study, we conducted chloroplast genome sequencing analysis on 10 cultivars of Sansevieria trifasciata. The chloroplast genomes exhibited a typical quadripartite circular structure (154.2–158.7 kb), encoding 113 functional genes with highly conserved gene order. Phylogenetic analysis supported the evolutionary linkage between Sansevieria and Dracaena. Dynamic inverted repeats (IR) boundary expansions/contractions, particularly species-specific patterns in ndhF and rps19 gene distributions across IR junctions, indicating its adaptive divergence. We also discovered the trnT-psbD marker, which is a deletion marker developed from hypervariable regions and can effectively distinguish closely related species. This work provides critical molecular tools and theoretical foundations for germplasm identification, phylogenetic reconstruction, and chloroplast genome evolution in Sansevieria, and also promotes taxonomic revisions in Asparagaceae.

1. Introduction

Sansevieria, native to tropical and subtropical Africa, Madagascar, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, demonstrates remarkable adaptability to a wide range of habitats [1]. Its broad geographic distribution and ecological niche differentiation likely contribute to complex interspecific morphological variation [2]. Valued globally as ornamental and economic plants, Sansevieria species display striking diversity in leaf morphology (sword-shaped, cylindrical), patterning (stripes, margins), and growth forms (clumping, upright) [3,4,5]. Time-calibrated phylogeny demonstrated five Sansevieria clades and dated back their divergence to 5 million years ago [2,6]. However, germplasm identification faces challenges in authenticating these cultivars: phenotypic plasticity, where conspecific individuals vary markedly across environments or developmental stages [7], and extensive artificial hybridization and selective breeding, producing cultivars with ambiguous genetic backgrounds and lacking diagnostic morphological traits [8]. While some studies have reported the chloroplast genome of S. trifasciata var. Laurentii, a comprehensive comparative analysis across multiple cultivars, including investigations into IR boundary dynamics, codon usage bias, and the development of validated molecular markers, remains unclear [9]. This taxonomic ambiguity hinders precise germplasm management, intellectual property protection, and in-depth studies on stress resistance mechanisms or medicinal compound biosynthesis [10]. Consequently, developing high-specificity molecular markers through genomic resources is critical for resolving phylogenetic relationships, authenticating cultivars, and elucidating links between geographic distribution and genetic divergence.

Chloroplasts, semi-autonomous organelles (originating from endosymbiotic events between early eukaryotes and cyanobacteria) responsible for photosynthesis, harbor genomes (cpDNA) which are typically maternally inherited in most angiosperms, contributing to their stability as phylogenetic markers [11]. In plant taxonomy, cpDNA serves as a pivotal molecular resource due to its maternal inheritance (with rare paternal or biparental exceptions), structural conservation, and moderate evolutionary rate [12]. Typical chloroplast genomes are circular double-stranded DNA molecules (120–160 kb), organized into four regions: a large single-copy (LSC), a small single-copy (SSC), and two inverted repeats (IRs). These genomes encode 110–130 functional genes, primarily involved in photosynthesis (psbA, rbcL), transcription-translation (rrn, trn), and chloroplast biogenesis, alongside non-coding regions that accumulate higher variability under relaxed selection, making them ideal targets for molecular marker development [13]. Despite the abundance of Sansevieria (commonly known as tiger orchid due to its striped leaves) germplasm resources, its genomic information has been less studied, especially the chloroplast genomes.

Advancements in next-generation sequencing have propelled cpDNA into the forefront of plant reclassification and evolutionary studies [14]. Conserved gene order facilitates cross-species comparisons, while hypervariable non-coding regions enable the design of species or population level markers. Four hypervariable regions (matK-rps16, ndhC-trnV-UAC, psbE-petL, and rps16-trnQ-UUG) may serve as potential molecular markers to distinguish Scutellaria baicalensis from its adulterants [15]. Multiple highly variable regions (such as petN-psbM, ndhC-trnV) may serve as potential molecular markers for the identification of four wild species of the genus Prunus [16]. It is evident that atpB-rbcL, psaI-accD, ycf2, ycf1, matK, rpoB-trnC, and clpP have been identified as potential highly variable DNA barcodes for mosses [17]. For Sansevieria, however, cpDNA-based marker systems remain unexplored. Developing such markers would not only circumvent the limitations of morphological taxonomy but also clarify evolutionary links to Dracaena [18]. Additionally, SNPs and InDels could precisely distinguish morphologically similar cultivars, offering effective tools for germplasm authentication and breeding innovation [19].

This study sequenced and assembled chloroplast genomes of 10 representative cultivars of Sansevieria trifasciata. The genomes exhibited a conserved circular structure (154.2–158.7 kb), encoding 113 unique genes (79 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNAs, 4 rRNAs), with gene order highly conserved across Asparagaceae. Phylogenetic analysis based on whole cpDNA sequences reconstructed maximum-likelihood trees, revealing monophyletic clustering of Sansevieria with select Dracaena species, supporting taxonomic reclassification. Utilizing these regions, we developed a series of polymorphic markers, with the trnT-psbD marker demonstrating polymorphic bands across all 10 samples, effectively discriminating cryptic species. These findings provide a molecular toolkit for precise germplasm identification and advance understanding of chloroplast genome evolution and Asparagaceae phylogenetics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and DNA Extraction

Ten S. trifasciata cultivars were selected based on their commercial importance (“Hani”, “Heijingang”, “Hehualan”, “Qinghulan”, “Zuanshilan”, “Yinmailan”, “Baiyulan”, “Huerlan”, “Foshou”, and “Bangye”). These cultivars exhibit distinct morphological traits, including variations in plant height and leaf coloration patterns. Fresh leaf tissue was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized using steel beads in a grinder. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Biomed Fast Plant Genomic DNA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were assessed via UV spectrophotometry (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis (1.0%). Only samples with A260/A280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 and high-molecular-weight bands on gels were used for sequencing. High-quality DNA samples were stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Chloroplast Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

Paired end libraries (350 bp inserts) were prepared and sequenced on the Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) NovaSeq 6000 platform (PE150) [20]. Raw reads were assembled into circular chloroplast genomes using GetOrganelle v1.7.5 with default parameters and the—fast to optimize assembly [21]. Genome annotation was performed using CPGAVAS2 [22], followed by manual correction in Apollo v3.0 [23]. tRNA and rRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [24] and BLASTn [25], respectively. Genome maps were visualized with OGDRAW [26].

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

Shared protein-coding genes were extracted from the 10 chloroplast genomes using PhyloSuite [27]. Sequences were aligned with MAFFT v7 using the—auto parameter [28], and maximum-likelihood trees were constructed using IQ-TREE (1000 bootstraps) [29]. Trees were visualized in ITOL [30].

2.4. Nucleotide Diversity Analysis and IR Analysis

Genome sequences were aligned with MAFFT v7 using the—auto parameter [28]. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) was calculated in DnaSP v6.0 [31] using sliding windows (500 bp window, 100 bp step). Sequence similarity was assessed with mVISTA in ShuffleLAGAN mode [32]. IRscope was employed to visualize LSC, SSC, and IR boundaries, along with adjacent gene distributions [33]. Expansion or contraction events were defined as junction shifts of ≥1 bp. Whole-genome alignments were performed using Mauve to evaluate structural conservation and detect rearrangements [34].

2.5. Molecular Marker Development

The polymorphic marker was designed from hypervariable regions using NCBI Primer-BLAST. Primer specificity was validated via PCR amplification using standard protocols (95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min/kb; 72 °C for 10 min) with appropriate negative controls, and Sanger sequencing.

3. Results

3.1. Assembly and Annotation of Chloroplast Genomes

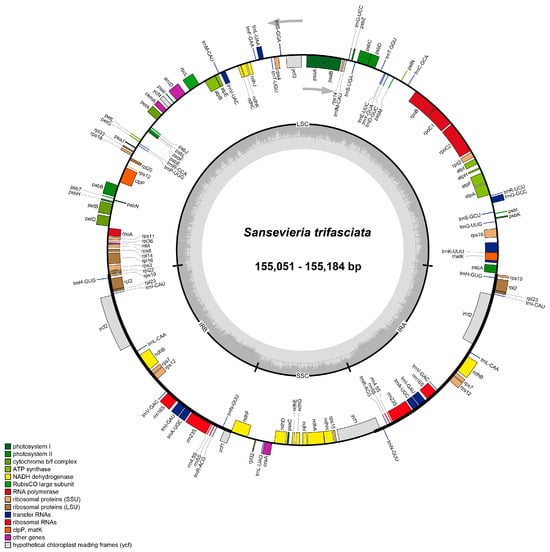

The chloroplast genomes of ten cultivars of S. trifasciata cultivars were successfully assembled into circular double-stranded DNA molecules, exhibiting a conserved quadripartite structure comprising Large Single Copy (LSC), Small Single Copy (SSC), and two Inverted Repeat (IR) regions (Figure 1). Genome annotation was performed using CPGAVAS, with manual correction in Apollo, and gene family assignment followed standard chloroplast gene functional groupings.

Figure 1.

The chloroplast genome maps of 10 cultivars of Sansevieria cultivars.

The circular structure of the chloroplast genome, displaying the typical quadripartite organization with Large Single Copy (LSC), Small Single Copy (SSC), and two Inverted Repeat (IR) regions. Genes are shown as colored blocks on the outer circle, with different colors representing different functional groups.

These genomes clustered into three distinct types based on size and structural features: Type 1 (155,184 bp; GC 37.46%) represented by cultivar ‘Hani’ (hpl-1); Type 2 (155,179 bp; GC 37.46%) encompassing seven cultivars (‘Heijingang’, ‘Hehualan’, ‘Qinghulan’, ‘Zuanshilan’, ‘Yinmailan’, ‘Baiyulan’, ‘Huerlan’); and Type 3 (155,051 bp; GC 37.44%) including ‘Foshou’ and ‘Bangye’ (hpl-11/12). Minor length variations primarily arose from differences in LSC (Type 1: 83,685 bp; Type 3: 83,603 bp) and IR regions (Type 1/2: 26,513 bp; Type 3: 26,492 bp), while SSC remained stable (18,473–18,464 bp) (Table 1 and Table S1).

Table 1.

Chloroplast genome three Sansevieria types.

Annotation revealed identical gene inventories across all types: 113 unique genes (79 protein-coding, 30 tRNA, 4 rRNA), with 16 functional gene families (Table S2). Genes present in multiple copies due to their location in the IR regions were concentrated in IR regions (rps19, rpl2, ndhB), while photosynthesis-related genes (psa, psb, rbcL) dominated LSC/SSC. The genes (ycf1, ndhF) spanned IR-SSC boundaries, and four rRNA genes (rrn4.5S, rrn5S, rrn16S, rrn23S) exhibited two IR copies. Genome maps confirmed structural homogeneity despite size polymorphisms (Figure 1), supporting high conservation in Sansevieria plastomes.

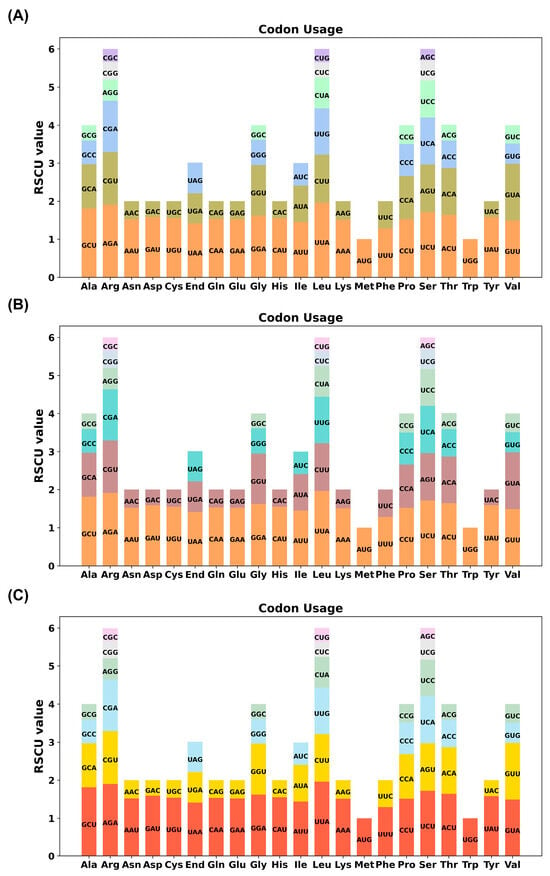

3.2. Codon Usage Bias

Analysis of 79 protein-coding genes (PCGs) identified pronounced synonymous codon bias favoring A/U-ending codons across all cultivars. Leucine exhibited the strongest preference for UUA (RSCU = 1.96), followed by alanine (GCU, RSCU = 1.81) and serine (UCU, RSCU = 1.71). In contrast, codons ending in G/C were underrepresented (GCC-Ala: RSCU = 0.62; GCG-Ala: RSCU = 0.41). Methionine (AUG) and tryptophan (UGG) showed no bias (RSCU = 1) due to single-codon assignment (Figure 2, Table S3).

Figure 2.

Codon preference analysis of the three Sansevieria chloroplast genome types. (A) Type 1; (B) Type 2; (C) Type 3.

Codon families are shown on the x-axis. RSCU values are the number of times a particular codon is observed relative to the number of times that codon would be expected for uniform synonymous codon usage.

This bias strongly correlated with overall AT-rich genomic composition. High RSCU values (>1.5) for phenylalanine (UUU), asparagine (AAU), and lysine (AAA) suggest selection for efficient translation via tRNA abundance or mRNA secondary structure optimization. Strikingly, codon profiles were nearly identical among the three types, indicating conserved translational regulation despite minor genomic divergence.

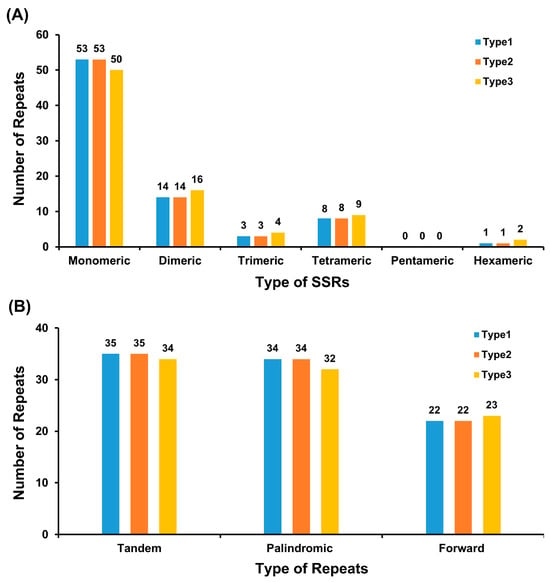

3.3. Repeat Sequence Analysis

Monomeric SSRs are the most abundant, and pentameric SSRs were absent. Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) were abundant, with 79 SSRs in Type 1/2 and 81 in Type 3 genomes (Table S4). Mononucleotide repeats predominated, primarily thymine (T)-homopolymers (Type 1/2: 27 T-repeats; Type 3: 25 A- and 25 T-repeats). Dinucleotide repeats constituted 17.7% (Type 1/2) and 19.8% (Type 3), while pentanucleotides were absent (Figure 3A, Table S5). Tandem repeats (10–32 bp) numbered 35 in Type 1/2 and 34 in Type 3, with sequence similarity >71%. Repeat analysis was performed using MISA for SSRs(https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/, accessed on 7 October 2025) and Tandem Repeats Finder for tandem repeats(https://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html, accessed on 7 October 2024), with minimum repeat units set to 10 for mononucleotides and default parameter for other types.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of repeat sequences in the three Sansevieria chloroplast genome types. (A) The number of SSRs for each repeat type. X-axis: SSR types; Y-axis: Number of repeat units. Colors: Type 1 (blue), Type 2 (orange), Type 3 (yellow). (B) The number of dispersed repeats (≥30 bp) by repeat type. Green: forward repeats; yellow: palindromic repeats; red: complementary repeats; blue: reverse repeats.

Dispersed repeats included palindromic (Type 1/2: 34; Type 3: 32) and direct repeats (Type 1/2: 22; Type 3: 23), ranging from 30 bp to 26.5 kb. The longest palindromic repeats corresponded to full-length IR regions (26,513 bp in Type 1/2; 26,492 bp in Type 3), while direct repeats peaked at 71 bp (Figure 3B, Table S6). These repeats were enriched near gene junctions (ycf1-ndhF), potentially influencing genome stability and recombination.

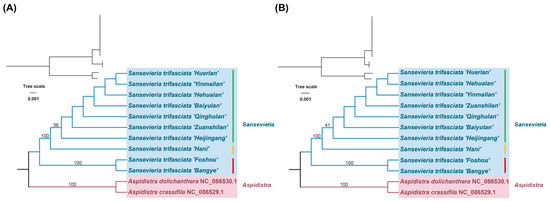

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

Maximum-likelihood trees constructed using whole chloroplast genomes (Figure 4A) and all 79 shared protein-coding genes (CDS) (Figure 4B) yielded congruent topologies. No filtering based on alignment quality or functional relevance was applied beyond the initial MAFFT alignment. All ten cultivars formed a monophyletic clade with 100% bootstrap support, subdivided into two subclades: Subclade I (Type 1 + Type 2 cultivars) and Subclade II (Type 3 cultivars). The sister relationship between Sansevieria and outgroups (Aspidistra crassifila and A. dolichanthera) aligned with Asparagales taxonomy under the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV) system.

Figure 4.

Maximum-likelihood trees based on whole-chloroplast genomes and shared coding sequences (CDS) of the 10 Sansevieria cultivars. (A) Tree constructed using whole chloroplast genomes. (B) Tree constructed using shared CDS. The trees were built with the maximum-likelihood method, and bootstrap values are shown at the nodes. Two Aspidistra species (A. crassifila and A. dolichanthera) were used as outgroups. Cultivars are labeled according to their genome type by green, yellow and red vertical bars, respectively (Type 1, Type 2, Type 3).

Type 2 cultivars formed a polytomy, indicating recent divergence. In contrast, Type 3 cultivars (‘Foshou’ and ‘Bangye’) exhibited longer branches, supporting genetic distinctiveness consistent with their smaller plastome size.

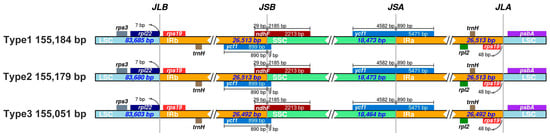

3.5. IR Boundary Expansion/Contraction Analysis

Comparative analysis of LSC/IRb (JLB), IRb/SSC (JSB), SSC/IRa (JSA), and IRa/LSC (JLA) junctions revealed differential boundary shifts (Figure 5). IR boundary analysis was performed using IRscope, and expansion/contraction events were defined as shifts in junction positions of ≥1 bp relative to the reference (Type 1). Genes rps19 and trnH were positioned near JLB in all types, while ycf1 spanned JSB (extending 1023–1042 bp into SSC). The ndhF gene overlapped JSA by 42–45 bp, and rpl2 crossed JLA with 12–15 bp in IRa.

Figure 5.

Comparison of LSC, SSC, and IR boundaries across the three Sansevieria chloroplast genome types. Genes located near the boundaries are shown above or below the main line. JLB, JSB, JSA, and JLA denote the junctions of LSC/IRb, IRb/SSC, SSC/IRa, and IRa/LSC, respectively.

Type 1 and Type 2 shared identical boundary coordinates, with IR regions spanning 83,686–110,198 bp (IRb) and 128,672–155,184 bp (IRa). In Type 3, IR contraction shifted IRb to 83,604–110,095 bp and IRa to 128,560–155,051 bp, reducing IR length by 21 bp. This contraction correlated with a 9 bp truncation in the LSC region (83,603 bp, 83,685 bp in Type 1).

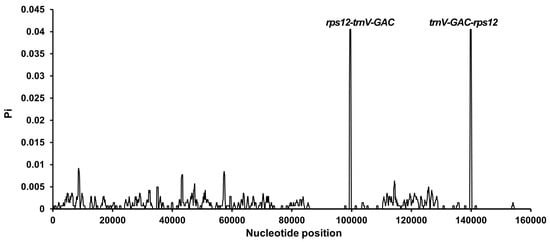

3.6. Nucleotide Diversity (Pi) Analysis

Sliding window analysis (500 bp window, 100 bp step) identified only two hypervariable regions (Pi > 0.02): rps12-trnV-GAC (Pi = 0.024) and trnV-GAC-rps12 (Pi = 0.021), both located within IR regions (Figure 6, Table S7). The majority of the genome exhibited minimal polymorphism (Pi < 0.005), highlighting exceptional sequence conservation.

Figure 6.

Sliding window analysis of nucleotide diversity (Pi) in 10 Sansevieria chloroplast genomes. Each point represents nucleotide diversity calculated per 500 bp window (step size 100 bp). The two hypervariable regions (rps12-trnV-GAC and trnV-GAC-rps12) are annotated.

mVISTA alignment (Type 1 as reference) confirmed >98% sequence similarity, with variations concentrated in intergenic spacers (trnT-UGU-trnL-UAA) rather than coding regions (Figure S1). Mauve alignment detected no large-scale rearrangements (>500 bp) among the three types (Figure S2). Collinear blocks covered 100% of all genomes, with local variations limited to indels <50 bp. Synteny was strongest in IR regions (100% identity), while LSC/SSC showed minor inversions near repeat-rich zones, none disrupting gene order.

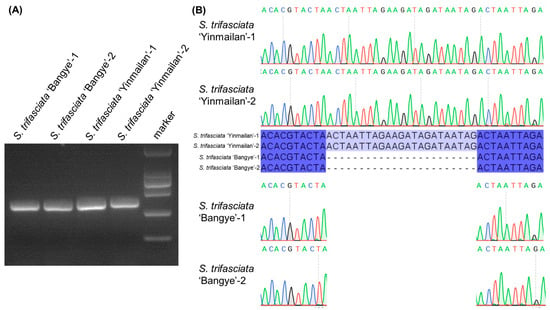

3.7. Molecular Marker Development

Hypervariable non-coding regions (prioritized based on structural variation, specifically the psbA-trnK-UUU region) was prioritized for marker design (Table S8). The PCR amplification of S. trifasciata ‘Yinmailan’ and S. trifasciata ‘Bangye’ resulted in expected specific fragments between 250 bp and 500 bp (Figure 7A). Sanger sequencing of PCR product verified the InDel identified in psbA-trnK-UUU (Figure 7B). PCR validation was successfully performed on relevant cultivars, confirming the marker’s polymorphism and utility for distinguishing the genome types.

Figure 7.

Verification of hypervariable regions as molecular markers in Sansevieria. (A) PCR amplification of two Sansevieria cultivars using primers designed from the hypervariable regions. M: DNA ladder (DL2000). (B) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of a representative PCR product. Blue indicates the consensus sequence; gray indicates specific sequences.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Conservation

The size of type 2 genome of S. trifasciata chloroplast (155,179 bp) is consistent to previously reported ones [9,35].The type 1 genome exhibited slightly bigger chloroplast size (155,184 bp), and type 3 genome exhibited smaller size (155,051 bp) than that of type 2. Few unique genes (113) were annotated in all the three types of this study compared to the previous S. trifasciata chloroplast genome [9]. Sansevieria plastomes are exceptionally well-preserved, spanning 113 genes and retaining their quadripartite structure and 100% collinearity. Despite the overall structural conservation, the 21 bp contraction in the IR regions of Type 3 cultivars (‘Foshou’ and ‘Bangye’) represents a notable genomic divergence. This shift towards a more compact plastome may reflect selective pressures associated with adaptation to specific cultivation environments. Similar patterns of IR contraction have been linked to genomic stability and evolutionary adaptation in other plant families [36,37]. Identifying such structural variations is crucial in providing reliable molecular landmarks for distinguishing between closely related cultivars that are morphologically similar, particularly during the early stages of growth.

4.2. Codon Bias

The pervasive A/U-ending codon preference (Leu-UUA RSCU = 1.96, Ala-GCU RSCU = 1.81) mirrors the plastome’s AT-richness (62.5%) and likely optimizes translational efficiency via tRNA abundance matching (a phenomenon observed in Carica papaya [38]). This A/U-ending codon bias, particularly in photosynthesis (rbcL) and transcription (rpo) genes, may contribute to optimized translational efficiency. We hypothesize that this could be an adaptive feature for Sansevieria, a species that often thrives in the variable light conditions of the understorey [39]. By aligning codon usage with the presumed abundance of the relevant tRNA pools, these plants might rapidly synthesize the photosynthetic apparatus in response to sunflecks, thereby enhancing their fitness in shaded environments. This finding reveals a fundamental aspect of Sansevieria’s molecular physiology and suggests potential genetic engineering targets to improve shade tolerance in other ornamental crops.

4.3. Hypervariable IRs

Contrary to most angiosperms where SSC regions harbor diversity hotspots, we identified two hypervariable loci within IRs (rps12-trnV-GAC and trnV-GAC-rps12, Pi > 0.02; Figure 6). Their stability in typically conserved IRs suggests Sansevieria-specific recombination [40]. These loci are ideal DNA barcodes for cultivar authentication, resolving ambiguities in commercial lineages (‘Yinmailan’ vs. ‘Fo Shou’). Furthermore, SSRs adjacent to these regions could serve as breeding markers-unlike unstable nuclear SSRs, chloroplast SSRs offer maternal inheritance tracing [40].

4.4. Phylogeny and Molecular Marker Development

The monophyly of all cultivars (100% bootstrap) confirms their shared origin from wild S. trifasciata, but deep divergence of Type 3 (Figure 4) supports its classification as a distinct varietal group. The polytomy among Type 2 cultivars (‘Heijingang’ to ‘Huerlan’) suggest recent clonal propagation, consistent with their dominance in mass horticulture. The psbA-trnK-UUU marker combination achieved 100% accuracy in discriminating tested samples, demonstrating the utility of chloroplast markers for cryptic species identification. However, the overall low genetic diversity of Sansevieria chloroplast genomes, compared to high diversity taxa like Orchidaceae, may stem from recent divergence or genetic bottlenecks during domestication. Sole reliance on chloroplast markers may inadequately resolve complex hybridization histories. Nuclear and chloroplast markers is critical for enhancing resolution. Future studies integrating nuclear genomic data will be critical for enhancing phylogenetic resolution. Ycf1, known as a transmembrane subunit of chloroplast TIC (translocon at the inner chloroplast membrane) complex, which transporting cytosolic proteins into chloroplast collaborate with TOC (translocon at the outer chloroplast membrane), was another gene presented boundary spanning [41]. Considering the importance of chloroplast in plant immunity, the functional validation of ycf1’s role in environmental adaptation remains essential [42,43]. In addition, the molecular marker developed in this study perfectly aligned with the morphological traits of different S. trifasciata cultivars at vegetative and later stage, shed light on the marker-assisted selection at seedling stage in S. trifasciata breeding.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes across ten cultivars of S. trifasciata. We identified three distinct plastome types, characterized by structural conservation, codon usage bias, and specific IR boundary contractions. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the monophyly of the cultivars and revealed evolutionary relationships. Notably, we discovered hypervariable regions within the typically conserved IRs and successfully developed and validated the polymorphic psbA-trnK-UUU marker, which effectively distinguishes closely related cultivars. These findings offer valuable molecular tools for germplasm identification, phylogenetic studies, and breeding programs in Sansevieria.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242606/s1, Figure S1: Sequence conservation profiles across the three Sansevieria chloroplast genome types, using Type 1 as the reference; Figure S2: Whole-genome alignments of the three Sansevieria chloroplast genome types using Mauve; Table S1: Genomic characteristics of three Sansevieria chloroplast types; Table S2: Gene composition in the chloroplast genome of Sansevieria; Table S3: Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) of codons for each amino acid in the type 1 and type 2 chloroplast genome; Table S4: SSRs identified in three type Sansevieria plastomes; Table S5:Tandem repeat sequences in the three type Sansevieria plastomes; Table S6: Dispersed repeat sequences in the three type Sansevieria plastomes; Table S7: Nucleotide Diversity Analysis Results of the chloroplast genomes; Table S8: Primers for verifying InDels among papaya varieties for barcodes development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, Z.H.; software, Z.H., H.K. and X.L.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, Z.H., H.K.; investigation, H.K.; resources, J.L. and H.Z.; data curation, Z.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H., H.K. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.D., J.L. and H.Z.; visualization, X.D.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (Grant No. SCKJ-JYRC-2023-72), the Innovational Fund for Scientific and Technological Personnel of Hainan Province (Grant No. KJRC2023D18) and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.324MS088).

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequence is available in nucleotide database of GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/, accessed on 1 December 2025) with accession numbers: PX240012-PX240021. The sequencing reads used for chloroplast genome assembly in this study have been released on the NCBI with those accession numbers: PRJNA1311453 (BioProject); SAMN50838609-SAMN50838618 (BioSample) and SRR35165483-SRR35165492 (SRA).

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank the experimental personnel and bioinformatics analysis at MitoRun research group participated in this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| SSR | Simple sequence repeat |

| ML | Maximum-likelihood |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| PCGs | Protein-coding gene sequences |

References

- Kasmawati, H.; Mustarichie, R.; Halimah, E.; Ruslin, R.; Arfan, A.; Sida, N.A. Unrevealing the Potential of Sansevieria trifasciata Prain Fraction for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia by Inhibiting Androgen Receptors Based on LC-MS/MS Analysis, and In-Silico Studies. Molecules 2022, 27, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleinwee, I.; Larridon, I.; Shah, T.; Bauters, K.; Asselman, P.; Goetghebeur, P.; Leliaert, F.; Veltjen, E. Plastid phylogenomics of the Sansevieria Clade of Dracaena (Asparagaceae) resolves a recent radiation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2022, 169, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hernandez, E.; Loera-Quezada, M.M.; Moran-Velazquez, D.C.; Lopez, M.G.; Chable-Vega, M.A.; Santillan-Fernandez, A.; Zavaleta-Mancera, H.A.; Tang, J.Z.; Azadi, P.; Ibarra-Laclette, E.; et al. Indirect organogenesis for high frequency shoot regeneration of two cultivars of Sansevieria trifasciata Prain differing in fiber production. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewatisari, W.F.; Nugroho, L.H.; Retnaningrum, E.; Purwestri, Y.A. Antibacterial and Anti-biofilm-Forming Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Sansevieria trifasciata Leaves Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Indones. J. Pharm. 2022, 33, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornenborg, C.W.; Qomariyah, N.; Gonzalez-Ponce, H.A.; Van Beek, A.P.; Moshage, H.; Van Dijk, G. Dracaena trifasciata (Prain) Mabb leaf extract protects MIN6 pancreas-derived beta cells against the diabetic toxin streptozotocin: Role of the NF-kappaB pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1485952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallei, T.E.; Rembet, R.E.; Pelealu, J.J.; Kolondam, B.J. Sequence Variation and Phylogenetic Analysis of Sansevieria trifasciata (Asparagaceae). Biosci. Res. 2016, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Khalumba, M.L.; Mbugua, P.K.; Kung’u, J.B. Uses and conservation of some highland species of the genus Sansevieria Thunb in Kenya. In African Crop Science Conference Proceedings; African Crop Science Society (ACSS): Kampala, Uganda, 2005; pp. 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, Y.J.; Zakaria, L.; Mohd, M.H. Identification, pathogenicity and histopathology of Colletotrichum sansevieriae causing anthracnose of Sansevieria trifasciata in Malaysia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, P.; Lei, K.; Ji, L. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Sansevieria trifasciata var. Laurentii. Mitochondrial DNA B 2021, 6, 198–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmawati, H.; Ruslin, R.; Arfan, A.; Sida, N.A.; Saputra, D.I.; Halimah, E.; Mustarichie, R. Antibacterial Potency of an Active Compound from Sansevieria trifasciata Prain: An Integrated In Vitro and In Silico Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hao, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, N.; Wang, K.; Jia, R. Elucidating phylogenetic relationships within the genus Curcuma through the comprehensive analysis of the chloroplast genome of Curcuma viridiflora Roxb. 1810 (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2024, 9, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Qian, Z.; Gichira, A.W.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. Assembly and comparative analysis of the first complete mitochondrial genome of the invasive water hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes. Gene 2024, 914, 148416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, L. Complete mitochondrial genome of Melia azedarach L., reveals two conformations generated by the repeat sequence mediated recombination. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Luo, L.; Li, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of Aglaia odorata, insights into its genomic structure and RNA editing sites. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1362045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Duan, B.; Zhou, Z.; Fang, H.; Yang, M.; Xia, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. Comparative analysis of medicinal plants Scutellaria baicalensis and common adulterants based on chloroplast genome sequencing. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Liu, C.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Jia, K.; Li, W. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Chloroplast Genomes of Four Wild Species of the Genus Prunus. Genes 2025, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, F.; Wang, L.; Dou, J.; Dong, T.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Dong, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Accelerating Moss Identification Through the Development of Specific DNA Barcodes Based on the Whole Chloroplast Genome. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2025, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jin, X.J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Li, P.; Meng, H.H.; Zhang, Y.H. Plastome evolution of Engelhardia facilitates phylogeny of Juglandaceae. BMC Plant. Biol. 2024, 24, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Chen, H.; Xuan, L.; Yang, Y.; Chong, X.; Li, M.; Yu, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang, F. Novel molecular markers for Taxodium breeding from the chloroplast genomes of four artificial Taxodium hybrids. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1193023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, L.; Fokias, K.; Saerens, G.; Bekaert, B. Cost-effective optimisation and validation of the VISAGE enhanced tool assay on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2025, 78, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chen, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Liu, C. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W65–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.E.; Searle, S.M.; Harris, N.; Gibson, M.; Lyer, V.; Richter, J.; Wiel, C.; Bayraktaroglu, L.; Birney, E.; Crosby, M.A.; et al. Apollo: A sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, H82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Lin, B.Y.; Mak, A.J.; Lowe, T.M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: Improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9077–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. High speed BLASTN: An accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 7762–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlic, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sanchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sanchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W273–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiryousefi, A.; Hyvonen, J.; Poczai, P. IRscope: An online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3030–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.C.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steane, D.A.; De Kok, R.P.; Olmstead, R.G. Phylogenetic relationships between Clerodendrum (Lamiaceae) and other Ajugoid genera inferred from nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 32, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.M.; Agarwal, A.; Dev, B.; Kumar, K.; Prakash, O.; Arya, M.C.; Nasim, M. Assessment of photosynthetic potential of indoor plants under cold stress. Photosynthetica 2016, 54, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittipornkul, P.; Treesubsuntorn, C.; Kobthong, S.; Yingchutrakul, Y.; Julpanwattana, P.; Thiravetyan, P. The potential of proline as a key metabolite to design real-time plant water deficit and low-light stress detector in ornamental plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 2024, 31, 36152–36162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, X.; Pan, L.; Huang, Q.; Hao, Z. Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes in Carica species reveals evolutionary relationships of papaya and the development of efficient molecular markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1686914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, R.; Wen, G. Analysis of codon usage patterns in complete plastomes of four medicinal Polygonatum species (Asparagaceae). Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1401013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.X.; Chang, X.; Gao, J.; Wu, X.; Wu, J.; Qi, Z.C.; Wang, R.H.; Yan, X.L.; Li, P. Evolutionary Comparison of the Complete Chloroplast Genomes in Convallaria Species and Phylogenetic Study of Asparagaceae. Genes 2022, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, A.; Rochaix, J.D.; Liu, Z. Architecture of chloroplast TOC-TIC translocon supercomplex. Nature 2023, 615, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gong, P.; Lu, R.; Lozano-Duran, R.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Chloroplast immunity: A cornerstone of plant defense. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Pan, J.; Yang, W. Chloroplast protein translocation complexes and their regulation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).