Abstract

Conventional harvesters usually depend on the operator’s expertise to manually manage the power allocation between the harvesting and traveling system, which results in problems like high subjectivity, labor intensity, and sensitivity to terrain. To overcome issues such as inadequate power and power mismatches between harvesting and traveling on gentle slopes, this study introduces a hydrostatic four-wheel-drive system featuring a single variable pump paired with two variable motors, improving the vehicle’s capability to handle complex terrains. Building on this system, an adaptive power allocation method for traveling is proposed. This method dynamically adjusts the power distribution between traveling and harvesting according to changing terrain conditions, giving priority to harvesting power while controlling vehicle and engine speeds to avoid engine stalls, thereby enhancing operational quality and efficiency. A model of the full vehicle system is created using Amesim 2410, and a comparation of adaptive control and constant speed control is modeled under a hardware-in-the-loop environment. The simulation results show that the proposed control approach effectively manages power distribution across different slopes and speeds, and avoids engine stalling, providing valuable technical guidance for power coordination control in harvesters working on gentle slopes.

1. Introduction

When operating on gentle slope farmland, harvesters must overcome additional slope resistance compared to operations on flat terrain, which affects the power distribution between harvesting and traveling systems. Conventional large harvesters are typically designed according to flatland operation standards, and often face issues of insufficient power and misalignment between harvesting and traveling power when deployed on gentle slopes. An excessive proportion of traveling power can lead to inadequate harvesting power, resulting in clogged conveyors. Conversely, insufficient traveling power can cause reduced vehicle speed, adversely affecting operational efficiency. Thus, the rational allocation of traveling power and harvesting power is essential for improving the adaptability of large harvesters in gentle slope farmland.

Hydrostatic transmission technology is currently extensively employed in harvesters to improve equipment adaptability on gentle slope farmland. Liu Z. et al. designed a hydrostatic drive system for hillside crawler tractors. They matched the system parameters based on a force analysis and verified the performance through a test bench. The results confirm that the system provides sufficient traction and maintains speed consistency, meeting the requirements for heavy-duty slope operations [1]. Paoluzzi R. and Zarotti L. investigated three hydrostatic transmission system configurations: a single-pump single-motor with a series gearbox, a single-pump with one fixed-displacement motor and one variable-displacement motor, and a single-pump with dual variable-displacement motors. They outlined the constraints on size, setting, and speed of the main hydraulic units imposed by each of the configurations and discussed their design rules in detail [2]. Dasgupta K. et al. conducted a theoretical analysis of the steady-state characteristics of a single-pump dual-motor drive system, followed by comparative experiments assessing the efficiency of single-motor versus dual-motor drive systems under varying load torques and speeds. The results demonstrated that the dual-motor hydrostatic transmission system exhibited higher efficiency under high load torque conditions [3]. Chen H. et al. presented a hydrostatic transmission for high-power cotton pickers that combines one variable-displacement pump with two variable-displacement motors. Through simulations and experimental validation, they confirmed the feasibility of the transmission scheme [4]. Guo X. et al. proposed an innovative design methodology for hydrostatic transmission systems. Departing from the conventional approach that prioritized the maximum power point, their method focused on maximizing efficiency at the system’s most frequent operating condition. They devised three distinct system configurations, which demonstrated a significant reduction in energy consumption [5]. Manring N. et al. presented a method for generating efficiency maps of hydrostatic transmission systems by developing mathematical models for pump and motor efficiency, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for system matching [6]. Wang H. et al. proposed an energy-saving adaptive speed control strategy based on power-tracking. This approach employs a loss model to calculate pump and motor efficiencies in real time, enabling precise adjustment of motor displacement. Additionally, it prevents engine overload stall and excessive system pressure by dynamically constraining pump and motor displacements according to system load, thereby substantially enhancing the system’s automatic adaptability to variable loads [7]. Hu K.et al. designed a hydrostatic transmission system for hilly tractors and verified the reliability of the design through simulation [8]. Ni X. improved the transmission system of the 4YZ-4B harvester by transitioning from front-wheel drive to four-wheel drive, simulation and experimental verification confirmed the feasibility of this modification [9]. Xu L. et al. developed the hydrostatic transmission system for the 4YZ-4G2 corn harvester and analyzed its transmission characteristics via simulation [10]. Chen H. et al. enhanced the traveling system of the Jiang C-2 combine harvester by replacing the original belt drive with a hydrostatic transmission, validating and optimizing the modification through simulation techniques [11]. Zhang L. et al. developed a hydrostatic transmission system for a domestic cotton picker, with field experiments confirming that all performance indicators met the design specifications [12].

Traditional harvesters typically adopted engine constant speed control [13], in which the operator preset the engine’s operating speed prior to operation, and the engine control unit (ECU) maintained this set speed to ensure stable operation. This method offered advantages such as straightforward control logic, high reliability, low cost, and easy implementation, but it lacked the capability to dynamically optimize power distribution between the traveling and harvesting systems. Another commonly used control strategy is the power tracking control; it first estimates the system’s required power through sensors, and then adjusts the engine speed accordingly to keep the engine operating within its high-efficiency range [14]. Although this adaptive power control ensured efficient engine performance, it still lacked active regulation of power allocation between the traveling and harvesting functions. As a result, conventional harvesters often depend on the operator’s expertise to manually allocate power between harvesting and traveling—an approach that remains subjective, labor-intensive, and vulnerable to variations in terrain.

This paper introduces a four-wheel-drive hydrostatic transmission system for harvesters. The system employs a single-variable displacement pump paired with two variable displacement motors, which are installed on the front and rear axles, respectively. This configuration improves the vehicle’s adaptability to complex terrain conditions. Building upon an existing electronically controlled pump, an adaptive traveling power control strategy has been developed. This strategy dynamically allocates power between traveling and harvesting operations according to terrain conditions, prioritizing harvesting performance. It adjusts engine speed and vehicle velocity to prevent engine stalling and enhances both operational efficiency and work quality. A full vehicle system model is constructed using Amesim, and a comparation of adaptive control (ADC) and constant speed control (CSC) is modeled under hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) environment. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed strategy facilitates rational power distribution across various slopes and operating speeds and avoids engine stalling. This study offers valuable technical insights for power coordination in harvesters operating on gentle slopes.

2. Chassis Design

2.1. Transmission System Scheme Design

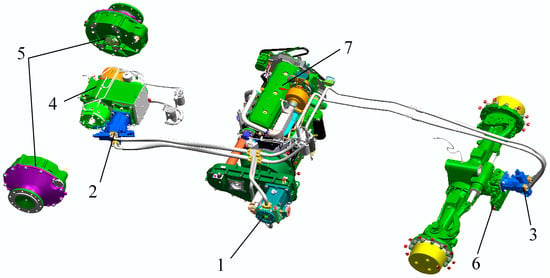

Taking into account the topographical features of gentle slope farmland and the working conditions of harvesters, a hydrostatic four-wheel transmission system is proposed. Compared to conventional mechanical transmission systems, the hydrostatic transmission presents several advantages: (1) By adjusting the swash plate angle of the closed-circuit pump, the direction and speed of the vehicle can be precisely controlled, enabling continuous, stepless speed variation. In contrast, operators of traditional mechanical transmission systems must divide their attention between harvesting tasks and managing gear shifts and directional changes. The hydrostatic transmission allows the operators to concentrate exclusively on harvesting, thereby simplifying operation and significantly reducing the workload. (2) The hydrostatic system itself can achieve vehicle braking without the need for an additional braking system. (3) The design obviates the need for drive shafts between the front and rear axles, which reduces the overall weight of the machine and increases ground clearance, thereby improving the harvester’s passability. The hydrostatic four-wheel-drive transmission system for the harvester is shown in Figure 1. It comprises two hydraulic motors that drive the front and rear axles, respectively, with a closed-circuit pump connected to both hydraulic motors through pipelines. Since 70% of the harvester’s weight is supported by the front axle, a two-speed planetary gearbox is installed on the front axle, wheel hub reducers are mounted on the front wheels, and a fixed-ratio gearbox is installed on the rear axle.

Figure 1.

Harvester Hydrostatic 4WD Transmission Scheme. (1. closed-circuit pump; 2. front axle motor; 3. rear axle motor; 4. transmission gearbox; 5. wheel hub reducer; 6. gearbox; 7. diesel engine).

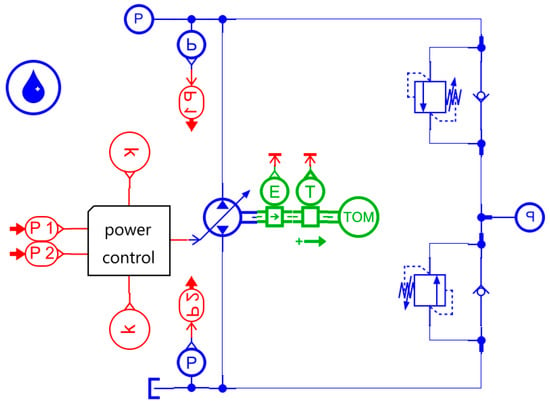

2.2. Hydraulic System Scheme Design

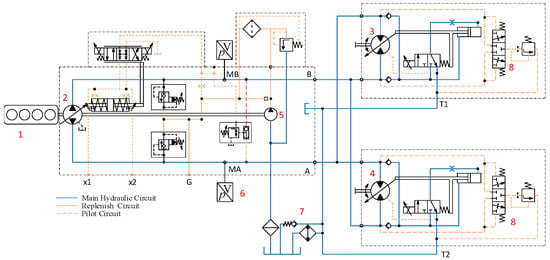

The schematic diagram of the hydrostatic transmission system is shown in Figure 2. The diesel engine (1) supplies power to the hydraulic system, while the electronically controlled closed-circuit pump (2) converts the mechanical energy from the diesel engine into hydraulic pressure. The pump’s displacement is adjusted through electrical signals from the controller. The closed-circuit pump is connected to the front and rear axle drive motors (3 and 4) via pipelines. Motors (3 and 4) are also electronically controlled, allowing their displacement to be adjusted by electrical signals from the controller.

Figure 2.

Harvester Hydrostatic Drive System Schematic Diagram. (1. engine; 2. closed-circuit pump; 3. front axle motor; 4. rear axle motor; 5. charge pump; 6. pressure sensor; 7. cooling circuit; 8. flushing valve).

In conditions such as climbing or harvesting, where greater traction force is required, motors (3 and 4) maintain maximum displacement. During transport operations, higher traveling speeds are necessary. Once the pump reaches its maximum displacement, speed can be further increased by reducing the displacement of the motors (3 and 4). The charge pump (5) is integrated into the closed-circuit pump (2) and serves to replenish the system with oil while also providing pilot oil pressure for the displacement mechanism. Due to the significant heat generated by the hydrostatic transmission, a separate cooling circuit (7) is required to cool the hot oil discharged from the flushing valve (8), ensuring system operates properly [15]. Detailed parameters are provided in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Main parameters of hydrostatic harvester chassis.

Table 2.

Variable pump and motor main parameter.

3. Controller Design

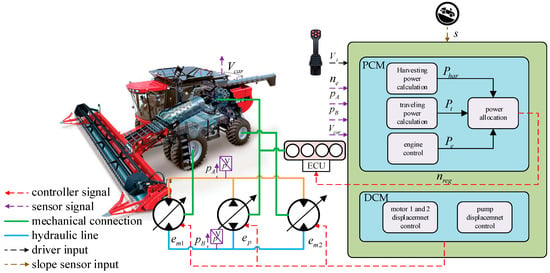

To ensure the quality of the harvesting operation, the harvester needs to dynamically adjust the power distribution between the traveling and harvesting system according to changing terrain conditions. The structural diagram of the controller is shown in Figure 3. The controller mainly consists of two parts: the displacement control module (DCM) and the power control module (PCM). The inputs of the controller are the target speed , pump port A and B pressure and , vehicle actual speed , engine speed and the slope s. The outputs of the controller are the pump, motor 1, motor 2 displacement control signals and engine-regulated speed .

Figure 3.

Harvester traveling system controller schematic diagram.

3.1. Displacement Control Module (DCM)

The primary function of the displacement control module is to regulate the displacement of the pump and motors according to the target speed and engine speed. During harvesting operations, the combine harvester operates at a speed between 4 and 6 km/h, requiring the traveling system to provide high traction output while the transmission remains in low gear.

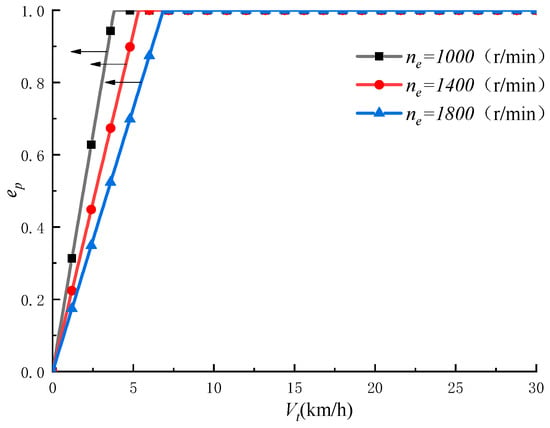

First, the displacement of the hydraulic pump gradually increases from zero, while both hydraulic motors maintain the maximum displacement. According to the flow continuity equation, the displacement ratio of the pump and motors varies with the vehicle speed and engine speed, as shown in Equations (1) and (2).

where: is the target vehicle speed, is the front axle ratio, is the first gear ratio of the front axle transmission, is the rear axle ratio, , , and are the maximum displacements of motor 1, motor 2, and the pump, respectively, and , , and are the displacement control signals for motor 1, motor 2, and the pump, respectively.

When the displacement of the hydraulic pump reaches its maximum, to further increase the traveling speed of the harvester, the displacement of the two hydraulic motors needs to be synchronously reduced. The variation pattern of the displacement control signals between the pump and the motors with respect to vehicle speed and engine speed are shown in Equations (3) and (4).

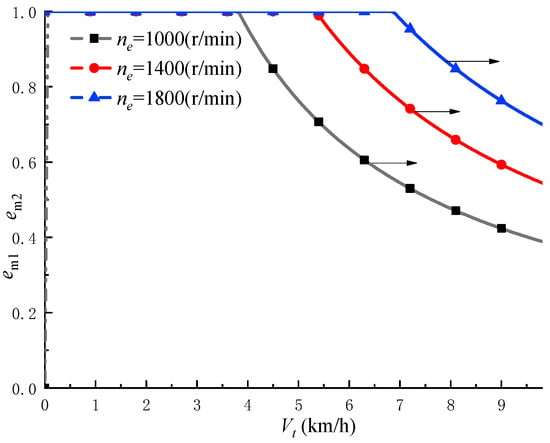

The variation pattern of the displacement ratios of the pump and motors with changes in vehicle speed and engine speed are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

The variation pattern of the pump displacement ratio with vehicle speed and number of revolutions of the engine.

Figure 5.

The variation pattern of the displacement ratio of dual motors with vehicle speed and number of revolutions of the engine.

3.2. Power Control Module (PCM)

The primary function of the power control module is to calculate the power requirements for harvesting and traveling system, and then allocate the available engine power accordingly.

3.2.1. Harvesting Power Calculation

The total harvesting power comprises six core components: the header, conveyor, threshing drum, cleaning device, shredding device, and grain auger.

The power demand of each component includes a base idling friction requirement plus an operational load that depends primarily on the crop feeding rate. The feeding rate is directly determined by vehicle speed , crop density , and header width , as expressed in the following formula:

In summary, a direct functional relationship exists between the vehicle’s speed and the total harvesting power required, since the speed determines the feed rate, which, in turn, drives the operational load of each subsystem. Thus, the harvester’s traveling speed is a key variable influencing the overall harvesting power demand, as expressed in the following formula:

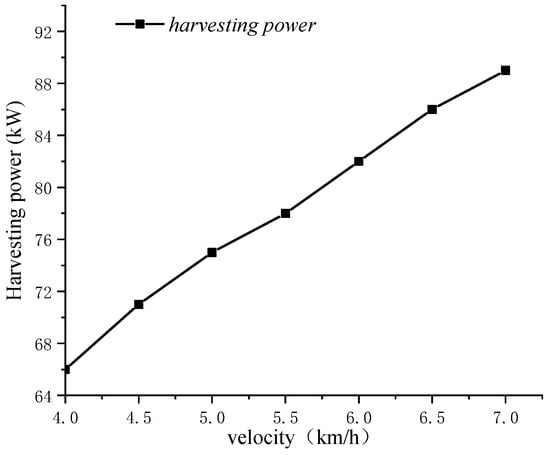

Based on the harvesting power calculation method described in the literature [16], the relationship between vehicle speed and harvesting power is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The relationship between vehicle velocity and harvested power.

3.2.2. Traveling Power Calculation

Using the target vehicle speed , the pressure difference between the hydraulic motor’s inlet and outlet, the transmission and final drive ratios of the front and rear axles , , , along with the mechanical efficiencies of the motor and , the power requirement of the traveling system can be calculated as follows:

3.2.3. Engine Control Unit (ECU)

The primary function of the engine control unit is to regulate the engine’s speed based on the driver’s settings. Since ECU manages engine speed through closed-loop control, the engine speed can be continuously modified by adjusting the command. Disregarding the influence of control errors and engine droop, the engine’s speed control behavior can be represented as follows:

The output power of the engine can be determined by its rotational speed and the throttle position .

The output power of the engine is mainly allocated to the traveling system, the harvesting system, and auxiliary system, as shown in Equation (10).

where: represents the power requirement of other auxiliary systems (cooling, lubrication, etc.). Based on empirical data, auxiliary systems typically consume only 10% of the total power. Therefore, in this paper, this is accounted for by deducting that power, with 90% of the engine’s maximum power considered as the upper limit of available power.

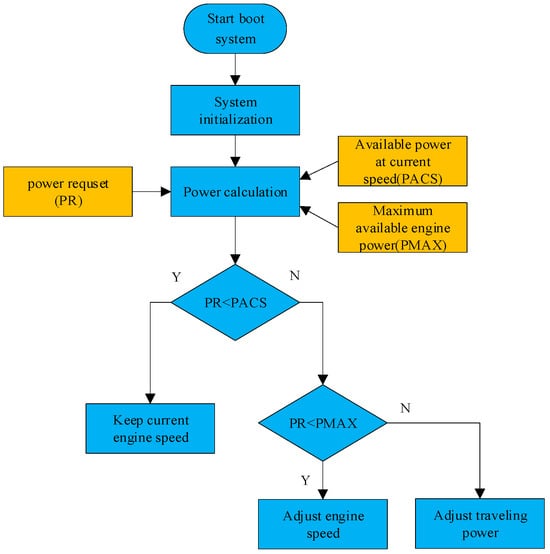

3.2.4. Power Allocation Control Strategy

The controller regulates both engine speed and vehicle speed based on the engine power available at the current speed (PACS) and the power requirement (PR) for traveling and harvesting, distributing power between these two functions accordingly. If the total power requirement is less than or equal to the available engine power at the current engine speed, the ECU keeps the engine speed unchanged. When the total power requirement exceeds the available power at the current engine speed but is still below the engine’s maximum power available power (PMAX), the ECU modifies the engine speed to match the total power requirement. If the total power requirement goes beyond the engine’s maximum available power, priority is given to fulfilling the harvesting power requirement, and the traveling power is adjusted accordingly. The maximum traveling power allowed is calculated by subtracting the harvesting power requirement from the available engine power. The process for adjusting traveling power is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Traveling power adjustment methodology schematic.

4. Traveling Power Control Implementation Method

There are two approaches to achieving constant power control in hydrostatic systems. The first is mechanical, which entails fitting a constant power valve [17,18] or DA valves within the hydraulic pump [19]. This technique is straightforward and effective but responds slowly. Moreover, adding these valves raises costs, and the speed adjustment process becomes relatively complicated. The second approach is electronic control, which integrates a constant power control program into the controller of an electronically controlled closed-circuit pump. This method provides greater flexibility, quicker response times, and easier adjustment of power control settings. Since this project uses the A4VGEP series of electronically controlled closed-circuit pumps, the electronic constant power control method is more suitable.

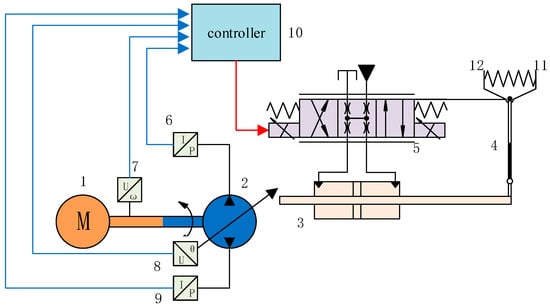

4.1. Constant Power Control Implementation

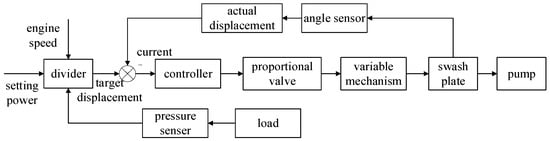

The electronically controlled closed-circuit pump A4VGEP mainly consists of a controller, a proportional valve, a variable displacement cylinder, and a feedback lever, a pump body, an angle sensor, a speed sensor, a pressure sensor, and additional components [20], as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The composition of A4VG electrohydraulic variable displacement pump. (1. engine; 2. pump body; 3. variable cylinder; 4. feedback lever; 5. proportional valve; 6. pressure senor; 7. speed sensor; 8. angle sensor; 9. pressure sensor; 10. pump controller; 11. right fork; 12. left fork).

When the electromagnetic coil on the left side of the proportional valve is energized, the proportional solenoid generates a corresponding electromagnetic force based on the current. The proportional valve spool moves to the right under the electromagnetic force, pushing the right fork, which overcomes the spring force and opens to the right. At the same time, the left position of the proportional valve operates, allowing pressurized oil into the left chamber of the variable piston while the right chamber drains oil. The variable piston moves to the right, pushing the left fork open through the feedback lever, further stretching the spring. When the spring force exceeds the electromagnetic force, the right fork pushes the valve spool to the left, continuously reducing the valve opening until it balances with the electromagnetic force and the valve closes. At this point, the variable piston remains in the corresponding intermediate position [21,22]. It can be seen that when the input current is fixed, the pump displacement is also correspondingly determined.

In a hydraulic system, power is the product of the pump’s output flow rate and output pressure. Constant power control requires ensuring that the product of the pump’s output flow rate and output pressure remains constant. Since the pump’s output pressure is determined by the external load, constant power control essentially achieves this by controlling the pump’s displacement [23].

In the controller (10), the control power is set. Pressure sensors (6 and 9) collect the system pressure, and speed sensor (7) collects the pump’s rotational speed, enabling the calculation of the target displacement corresponding to the current set power. Then, the angle sensor (8) collects the swashplate angle of the pump, which is converted into the actual displacement of the pump. When the actual displacement of the pump is less than the target displacement, controller (10) calculates the displacement difference and, based on its internal calculation program, outputs a control current. This causes the electromagnetic force to exceed the spring force, making the proportional valve (5) operate in the right position. High-pressure oil enters the left chamber of the variable piston, and the right chamber is connected to low-pressure oil. The variable cylinder (3) moves to the right, increasing the pump displacement and thus increasing the pump’s output power. When the pump’s output displacement exceeds the target displacement, controller (10) reduces the output current, causing the electromagnetic force to be less than the spring force. The proportional valve (5) then operates in the left position, allowing high-pressure oil into the right chamber of the variable cylinder (3) and connecting the left chamber to low-pressure oil. The pump displacement decreases, reducing the pump’s output flow. The entire control process is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Flowchart of the A4VG power control process.

4.2. Simulation Verification of Constant Power Control of Electric Control Pump

To verify the feasibility of the constant power control strategy, an electro-hydraulic closed-loop pump and the corresponding constant power control model were built in Amesim [24,25].

First, two pressure sensors, A and B, are installed at ports A and B of the closed-circuit hydraulic pump to measure the pressures at these ports, denoted as and , respectively. Based on the torque calculation formula for the hydraulic pump, the maximum torque required to drive the closed-circuit hydraulic pump is given by:

where is the maximum torque, is the maximum displacement of the closed-circuit hydraulic pump, is the mechanical efficiency of the pump, then the pump speed is obtained through a speed sensor, and the corresponding torque is calculated based on the preset power , to compute the control ratio for the displacement.

Then, convert into a current input for the closed-loop pump, which outputs the corresponding displacement. The model is built as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Simulation model of the electrohydraulic pump power control.

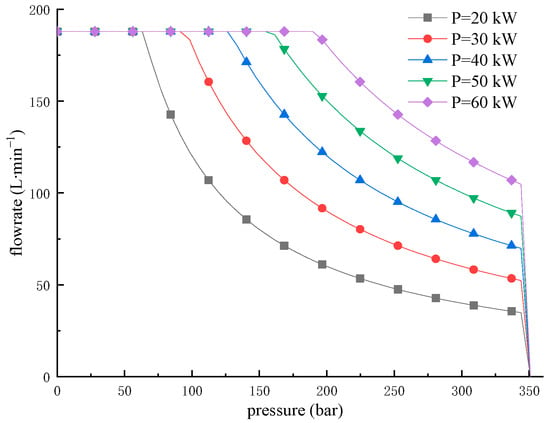

The hydraulic pump drive speed was set to 1300 r/min, with the pressure at port A maintained at 20 bar. As the pressure at port B gradually increased, the pump’s setting power was sequentially adjusted to 20 kW, 30 kW, 40 kW, 50 kW, and 60 kW. The constant power control characteristic curves of the hydraulic pump under these different power settings are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Constant power control characteristics of the hydraulic pump under different power settings.

From the simulation results, when the pressure is low, the pump maintains its maximum flow output. As the pressure gradually increases and reaches the constant power control point, the relationship between pressure and flow follows a hyperbolic curve. When the pressure reaches the maximum set value of 350 bar, the pump flow rapidly drops to zero. The simulation analysis preliminarily verifies the feasibility of closed-loop constant power control for the electronically controlled pump.

5. Vehicle System Simulation Modeling and Result Analysis

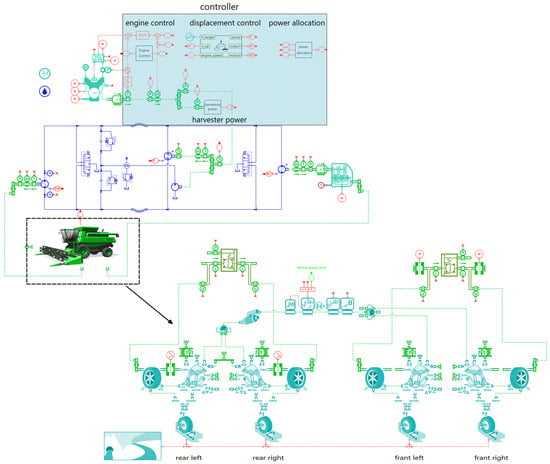

5.1. Full Vehicle System Modeling

The harvester’s full vehicle system consists of a hydraulic system, engine, control system, transmission system, harvesting system and chassis system. In modeling the hydraulic system, the dynamic response of the variable mechanism is ignored because its response time is much faster than that of the vehicle. For the engine model, a lookup table approach is used by directly loading the brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) curve. The tire model is based on a soft soil model. Since this study concentrates on power control of the traveling system, it assumes standardized farmland with uniform crop growth. The power consumption of the harvesting system is simulated by applying an equivalent load torque, as depicted in Figure 6 and loaded into the model. When modeling the transmission system, the rotational inertia is disregarded, focusing only on the speed ratio and efficiency. By inputting the parameters from Table 1 into the model, the harvester’s traveling system model is obtained, as shown in Figure 12 [26].

Figure 12.

Harvester system modeling in Amesim.

5.2. Simulation Result Analysis

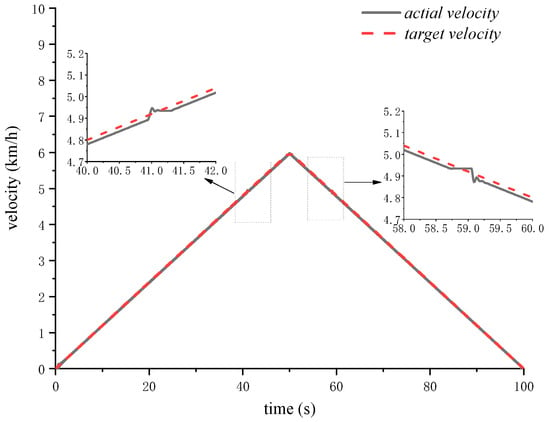

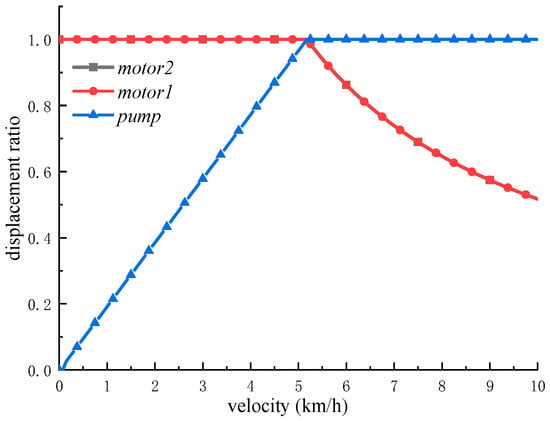

Set the vehicle speed to accelerate uniformly from 0 to 6 km/h, then decelerate uniformly back to 0. The resulting vehicle speed, the pump’s and the two motors’ displacement ratio are shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Target speed vs. actual speed.

Figure 14.

Variation in Pump and Motor Displacement Ratio with Vehicle Speed.

The simulation results show that the actual vehicle speed closely matches the target speed, though small fluctuations occur at 41 s and 59 s. These fluctuations happen because the pump displacement hits its maximum at those times. To increase speed further, the motor must decrease its displacement. Due to a delay in the controller, the motor reacts slightly slower, causing minor speed variations. When the vehicle speed is between 0 and 5 km/h, it operates in low gear with motors displacement ratio of 1. As the speed increases, the pump displacement ratio rises. Once the vehicle reaches 5 km/h, the pump displacement is at its maximum; so, to continue accelerating, the motors displacement ratio must be lowered.

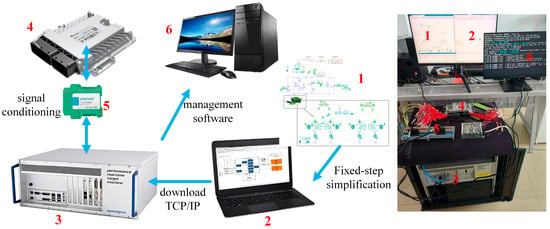

6. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation

To further confirm the practicality of the traveling power adaptive control strategy, Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) technology is utilized for validation. HIL is a method that combines real hardware components with computer simulation models to perform testing and verification within a closed-loop system [27]. The purpose of using HIL technology is to assess the feasibility and dependability of the control strategy in a testing environment that closely mimics real-world conditions, thereby reducing the expenses and risks linked to actual vehicle testing. This technique allows for the integration of real controllers with virtual controlled elements, enabling precise and efficient testing of complex systems. It is particularly well-suited for systems with intricate dynamic behaviors, such as hydrostatic transmissions, ensuring the control algorithms remain stable in real-world applications.

The previously described traveling power adaptive control strategy was implemented using the CODESYS 64 3.5.19.70 platform and uploaded to a C380 controller which is equipped with an angle sensor based on the MEMS architecture, it can measure pitch and roll angles within a range of ±90°. The full vehicle system model, after being processed with fixed steps, is transferred to a real-time machine through a host computer. The controller and the controlled system model communicate via hardware I/O boards. The real-time machine sends data such as hydraulic system pressure and engine speed to the controller through the I/O boards after signal modulation. Likewise, the controller processes this information and sends back control signals for pump and motor displacements, as well as engine speed adjustments, to the real-time machine via the I/O boards following modulation. The complete hardware-in-the-loop setup is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Physical diagram of a hardware-in-the-loop simulation system. (1. harvester traveling system model; 2. host computer; 3. Speed Goat real-time target machine; 4. ECU; 5. I/O signal condition-ing; 6. monitor).

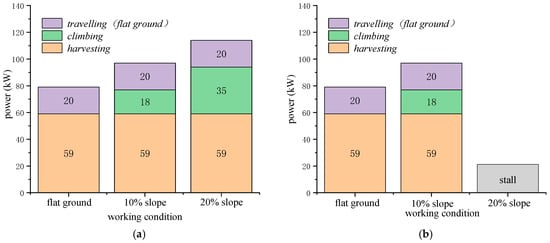

Compare the differences between the ADC and CSC control methods, and upload the corresponding code for each strategy into the controller. In the simulation model, the engine speed was set at 1300 r/min (economic speed), and the vehicle was set to travel uphill at speeds of 4 km/h, 5 km/h, and 6 km/h on three types of slopes: flat ground, a 10% slope, and a 20% slope, so as to simulate the working states of the two control strategies under different vehicle speeds and slopes.

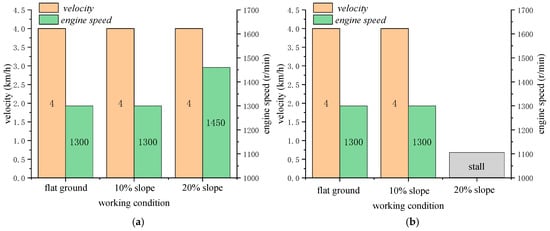

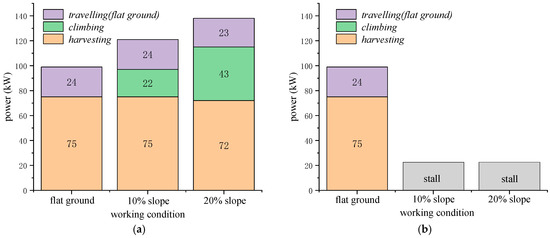

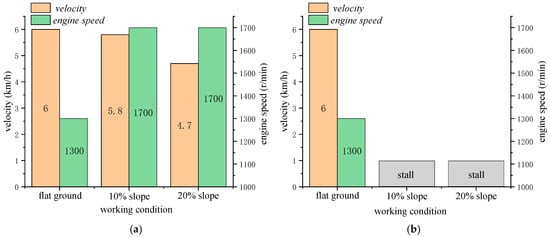

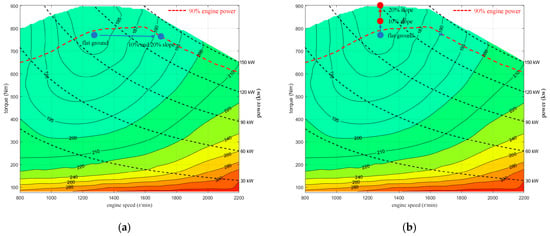

Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 present the simulation results of the harvester operating at 4 km/h under flat, 10% slope, and 20% slope conditions, under two control strategies: ADC and CSC. As shown in Figure 16, the required harvesting power is 59 kW, while the traveling power on flat ground is 20 kW. The total power demand remains within the engine’s capacity at 1300 r/min on flat ground and on the 10% slope, where an additional 18 kW is needed for climbing. Therefore, under these conditions, no engine speed adjustment is required, and both control strategies yield identical power distribution results.

Figure 16.

Power Distribution Comparison between ADC and CSC at 4 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Power Distribution of ADC; (b) Power Distribution of CSC.

Figure 17.

Vehicle Speed and Engine speed Comparison between ADC and CSC at 4 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of ADC; (b) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of CSC.

Figure 18.

Engine Operating Point Comparison between ADC and CSC at 4 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Engine Operating Point of ADC; (b) Engine Operating Point of CSC.

However, on a 20% slope, the total power demand exceeds the available power at 1300 r/min. The ADC controller increases the engine speed by approximately 11.5%, from 1300 to 1450 r/min, to meet the higher power requirement and prevent engine stall. In contrast, the CSC strategy maintains a fixed engine speed regardless of the slope, which leads to insufficient power and results in engine stall. Additionally, as shown by the engine operating points in Figure 18, the engine efficiency under the ADC strategy increases from 43.2% on flat ground to 44.7% on a 10% slope, and further to 44.9% on a 20% slope, as determined from the BSFC map.

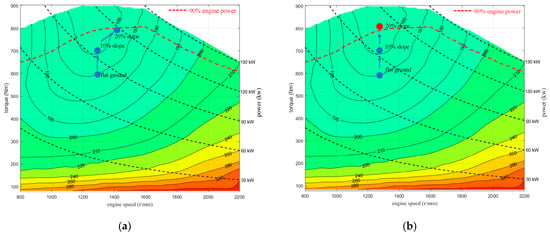

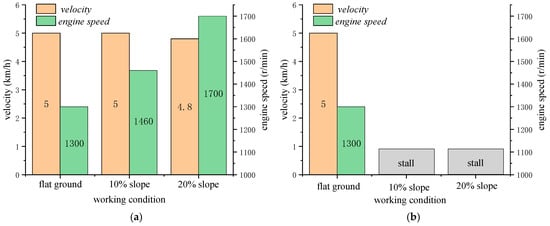

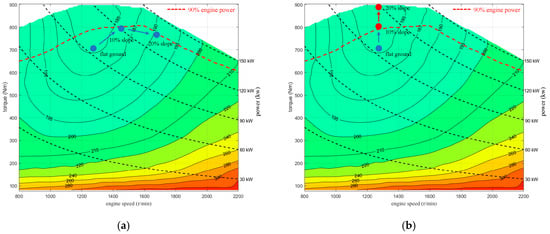

Figure 19, Figure 20 and Figure 21 present the simulation results for the harvester operating at 5 km/h under flat, 10% slope, and 20% slope conditions, under two control strategies: ADC and CSC. As illustrated in Figure 19, the required harvesting power is 75 kW, while the traveling power on flat ground is 24 kW. The total power demand remains within the engine’s capacity at 1300 r/min on flat ground; so, no speed adjustment occurs. On a 10% slope, the ADC controller raises the engine speed to 1460 r/min to satisfy the increased power need. However, on a 20% slope, the total power requirement exceeds the engine’s maximum output; thus, the ADC strategy reduces the vehicle speed to 4.8 km/h, thereby lowering traveling power to 23 kW and harvesting power to 72 kW to avoid engine stall.

Figure 19.

Power Distribution Comparison between ADC and CSC at 5 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Power Distribution of ADC; (b) Power Distribution of CSC.

Figure 20.

Vehicle Speed and Engine speed Comparison between ADC and CSC at 5 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of ADC; (b) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of CSC.

Figure 21.

Engine Operating Point Comparison between ADC and CSC at 5 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Engine Operating Point of ADC; (b) Engine Operating Point of CSC.

In contrast, the CSC strategy maintains a fixed engine speed across all slopes, which results in insufficient power on steeper gradients, causing the engine to stall. Additionally, Figure 21 illustrates the engine operating points derived from the BSFC map. The engine efficiency under the ADC strategy decreases from 44.7% on flat terrain to 44.2% on a 10% slope, and further declines to 43.1% on a 20% slope.

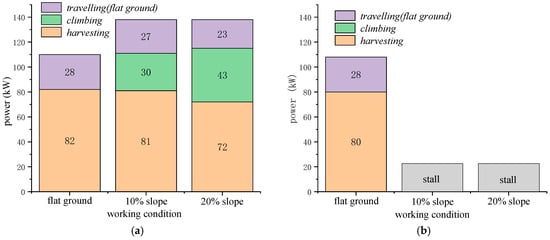

Figure 22, Figure 23 and Figure 24 illustrate the simulation results for the harvester operating at 6 km/h under flat, 10% slope, and 20% slope conditions, under two control strategies: ADC and CSC. According to Figure 22, the harvesting power required is 82 kW, with an additional 28 kW needed for travel on flat ground. The total power demand remains within the engine’s capacity at 1300 r/min on flat terrain; so, both strategies maintain a constant engine speed. However, on slopes of 10% and 20%, the total power required exceeds the engine’s available output. Using the ADC strategy, the controller allows the engine to operate at the maximum power point and reduces the vehicle speed to 5.8 km/h on a 10% slope and to 4.7 km/h on a 20% slope. This lowers the traveling power to 27 kW and 23 kW, respectively, and reduces the harvesting power to 81 kW and 72 kW, thereby preventing engine overload. In contrast, the CSC strategy keeps the engine speed fixed regardless of the slope, which results in insufficient power and causes the engine to stall. Figure 23 shows these changes in velocity and engine speed under the two control strategies.

Figure 22.

Power Distribution Comparison between ADC and CSC at 6 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Power Distribution of ADC; (b) Power Distribution of CSC.

Figure 23.

Vehicle Speed and Engine speed Comparison between ADC and CSC at 6 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of ADC; (b) Vehicle Speed and Engine speed of CSC.

Figure 24.

Engine Operating Point Comparison between ADC and CSC at 6 km/h on Different Slopes. (a) Engine Operating Point of ADC; (b) Engine Operating Point of CSC.

Additionally, as indicated by the engine operating points in Figure 24 and based on the BSFC map, the engine efficiency under the ADC strategy decreases from 44.7% on flat terrain to 43.1% on both 10% and 20% slopes. This reduction occurs because the ADC strategy increases the engine speed.

7. Conclusions

This paper introduces a four-wheel-drive hydrostatic transmission system for harvesters. The system employs a single-variable displacement pump paired with two variable displacement motors, which are installed on the front and rear axles, respectively. This configuration improves the vehicle’s adaptability to complex terrain conditions. Based on the original electronically controlled pump, an adaptive traveling power control strategy has been developed. This strategy dynamically adjusts the power distribution between traveling and harvesting according to different terrains, prioritizing harvesting power while regulating engine speed and vehicle speed to prevent engine stalling. As a result, it improves both operational quality and efficiency. A model of the full vehicle was constructed using Amesim software, and a comparation of adaptive control and constant speed control is modeled under a hardware-in-the-loop environment. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed control strategy achieves reasonable power distribution under various slope and speed conditions and avoids engine stalling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X., W.M. and X.W.; methodology, J.X. and X.W.; software, J.X.; validation, J.X., Z.W. and X.W.; formal analysis, J.X.; investigation, J.X.; resources, Z.W.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and Z.W.; visualization, J.X.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology Youth Growth Science and Technology, grant number 20230508151RC, research on power matching and optimization of hydrostatic transmission system for corn harvesters in hilly areas.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on demand from the corresponding authors at wangxin_jlu@jlu.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DCM | Displacement Control Module |

| PCM | Power Control Module |

| PR | Power Requirement |

| PMAX | Maximum Available Engine Power |

| PACS | Available Power at Current Speed |

| ECU | Engine Control Unit |

| BSFC | Brake Specific Fuel Consumption |

| HIL | Hardware In the Loop |

| ADC | Adaptive Control |

| CSC | Constant Speed Control |

References

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chu, G.; Niu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F. Design Matching and Dynamic Performance Test for an HST-Based Drive System of a Hillside Crawler Tractor. Agriculture 2021, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoluzzi, R.; Zarotti, L. Properties and sizing methods of 2-motor transmissions. Int. J. Fluid Power 2017, 18, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, R. Steady state performance analysis of hydrostatic transmission system using two motor summation drive. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. C 2013, 94, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Ni, X.; Cai, W.; Zhong, C.; Ye, H.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, W.; Lin, Y. Design of Hydrostatic Power Shift Compound Drive System for Cotton Picker Experiment. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Vacca, A. Advanced design and optimal sizing of hydrostatic transmission systems. Actuators 2021, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, N. Mapping the efficiency for a hydrostatic transmission. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 2016, 138, 031004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; An, Z.; Liu, R. energy-efficient adaptive speed-regulating method for pump-controlled motor hydrostatic drive powertrains. Processes 2023, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Kun, J. Design and Simulation of the Hydraulic Traveling System of Hilly Tractors. Mach. Tool Hydraul. 2021, 49, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, X. Matching and Performance Simulation for the Hydraulic Travel Traveling System of Combine Harvester. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, H. Transmission Characteristic research on Hydrostatic Transmission System of Corn Harvester. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2018, 40, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Guo, H.; Lv, Q.; Xu, Z.; Gao, G. Design and Simulation of Hydraulic Traveling System for Xinjiang C-2 Combine Harvester. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2018, 40, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Sheng, J. Design and Experimental Study on Key Hydraulic System of Cotton Picker. Farm Machinery 2022, 12, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. Research on the Electro-Hydraulic Transmission and Control System of Combine Harvesters Based on Hydraulic Drive. Tract. Farm Transp. 2025, 52, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Yan, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. Research on energy-saving optimization control of multi-working conditions for hybrid electric tractors based on a constrained proportional power-following strategy. J. Intell. Agric. Mech. 2025, 6, 35−44. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. Research on Hydrostatic Drive System of Grain Combine Harvester. Master’s Thesis, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Chai, X.; Xu, L.; Quan, L.; Yuan, C.; Tian, S. Design and performance of a distributed electric drive system for a series hybrid electric combine harvester. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 236, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Study on LR Control Characteristics of Piston Pump Based on AMESim. Hydraul. Pneum. Seals 2020, 40, 32–35+39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Analysis of Constant Power Control for Hydraulic Drive System of Shield Machine Cutterhead. Constr. Mech. 2023, 44, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, J. Function Analysis and System Debugging of Hydraulic Pump with DA Valve. Tunn. Constr. 2020, 40, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Dynamic Characteristics Analysis on HD Valve of A4VG Closed Type Pump. Hydraul. Pneum. Seals 2018, 38, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H. Introduction of Remote Pressure Control System Based on REXROTH A4VG Pump. Hydraul. Pneum. Seals 2018, 38, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Domestic A4VG Hydraulic Pump Performance Characteristics Analysis and Test. Master’s Thesis, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G. Research on Constant Power Control and Fault Diagnosis Method of Main Hydraulic Pump for Truck-mounted Concrete Pump. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Liao, H.; Ma, W. Hydraulic Retarder Filling Rate Control Simulation Experimental Research Based on Weak Coupling Co-simulation. Hydraul. Pneum. Seals 2023, 43, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, L. Fault diagnosis of hydraulic system based on DS evidence theory and SVM. Int. J. Hydromechatronics 2024, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Xie, J.; Nie, L. Amesim Mechatronics Simulation Tutorial, 1st ed.; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Control method for automotive PEMFC air supply system and research on vehicle energy management strategies. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).