Economic and Financial Performance of Smallholder Dairy Farms in the Mexican Highlands: Prospective to 2033

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Representative Smallholder Dairy Farms (RSDFs)

2.2. Model Specification

2.3. Stochastic Variables of the Model

2.4. Economic and Financial Viability Indicators

2.5. Model Assumptions

3. Results

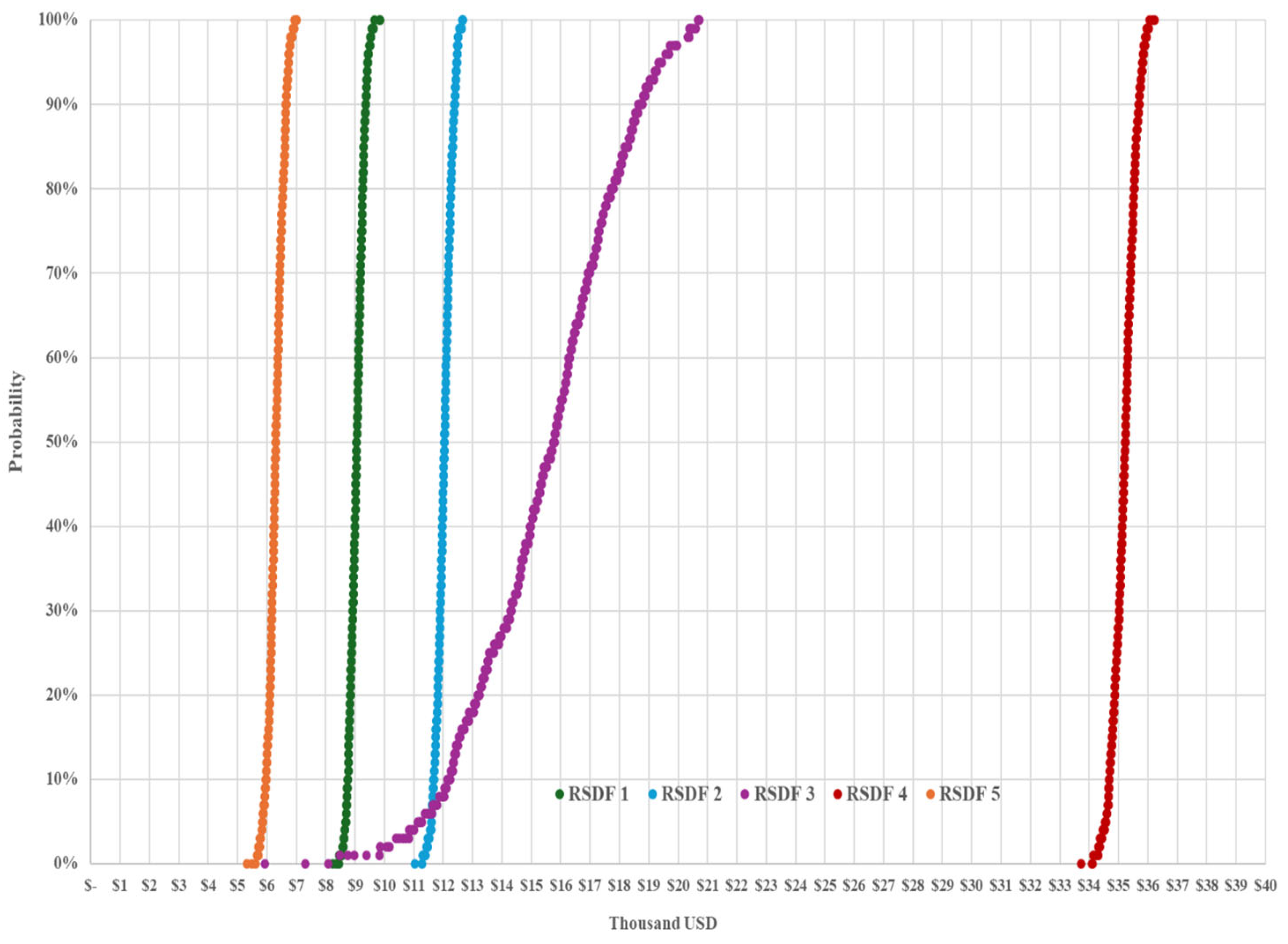

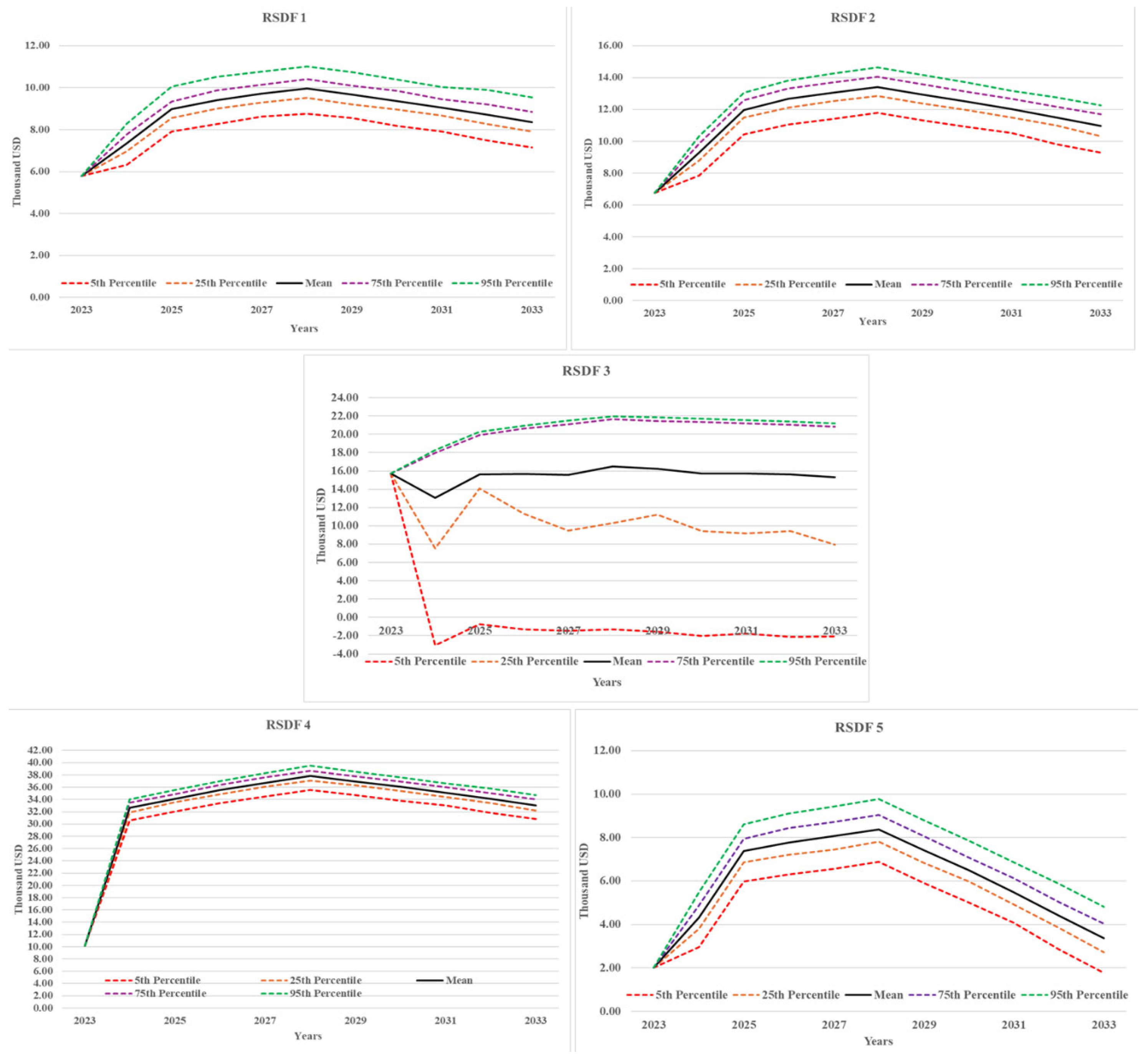

3.1. General Panorama

3.2. Economic Viability Indicators

3.3. Financial Viability Indicators

3.4. Role of Family Labor in the Economic and Financial Viability of Smallholder Dairy Farms

4. Discussion

4.1. General Panorama

4.2. Economic Viability Indicators

4.3. Financial Viability Indicators

4.4. Role of Family Labor in the Economic and Financial Viability of Smallholder Dairy Farms

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSND | Adjusted correlated standard normal deviation |

| B/C | Benefit to cost ratio |

| CFD | Correlated fractional deviations |

| CMR | Crop market receipts |

| CSND | Correlated standard normal deviation |

| CUD | Correlated uniform deviation |

| DR | Dairy receipts |

| ECD | Empirical Cumulative Distribution |

| ECM | Energy-corrected milk |

| ECR | Ending cash reserves |

| EHL | External hired labor |

| FL | Family labor |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IRR | Internal rate of return |

| ISND | Independent standard normal deviation |

| KOV | Key output variable |

| MVE | Multivariate empirical distribution |

| NC | Net cash |

| NCFI | Net cash farm income |

| NPV | Net present value |

| ROA | Return on assets |

| RRA | Rate of return on assets |

| RSDF | Representative smallholder dairy farm |

| SCM | Solids-corrected milk |

| TE | Total expenditure |

| TI | Total income |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| USD | United States dollar |

References

- IFCN Dairy Research Network. IFCN Dairy Outlook 2030. Available online: https://ifcndairy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IFCN-Dairy-Outlook-2030-Article-1.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- OECD; FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, P. Does plant-based milk reduce sales of dairy milk? Evidence from the almond milk craze. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2023, 52, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J.H.; Cushman, R.A.; Dechow, C.D.; Dobson, H.; Humblot, P.; Hutjens, M.F.; Jones, G.A.; Ruegg, P.S.; Sheldon, I.M.; Stevenson, J.S. Invited review: Learning from the future—A vision for dairy farms and cows in 2067. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3722–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, R.; Infascelli, F. The Path to Sustainable Dairy Industry: Addressing Challenges and Embracing Opportunities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Schäfer, D.; Holm-Müller, K.; Britz, W. On-farm compliance costs with the EU-Nitrates Directive: A modelling approach for specialized livestock production in northwest Germany. Agric. Syst. 2019, 173, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing, M.M.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Harrigan, T.; Woznicki, S.A. Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farm Management—University of Wisconsin–Madison Division of Extension. The Future of Global Dairy: Economic Trends, Regional Developments, and Market Vulnerabilities Through 2030. Available online: https://farms.extension.wisc.edu/articles/the-future-of-global-dairy-economic-trends-regional-developments-and-market-vulnerabilities-through-2030/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Hemme, T.; Otte, J. Status of and Prospects for Smallholder Milk Production—A Global Perspective; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IFCN. IFCN Dairy Report 2024. Available online: https://ifcndairy.org/ifcn-products-services/dairy-report/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Fariña, S.R.; Baudracco, J.; Bargo, F. Dairy production in diverse regions: Latin America. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; McSweeney, P.L.H., McNamara, J.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Pérez, L.M.; Soriano-Robles, R.; Espinosa-Ortiz, V.E.; Miguel-Estrada, M.; Rendón-Rendón, M.C.; Jiménez-Jiménez, R.A. Does small-scale livestock production use a high technological level to survive? Evidence from dairy production in Northeastern Michoacán, Mexico. Animals 2021, 11, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas-Domínguez, R.R.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E. Contribution of family labour to the profitability and competitiveness of small-scale dairy production systems in central Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyhard, J.; Tauer, L.; Gloy, B. Analysis of price risk management strategies in dairy farming using whole-farm simulations. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Uddin, M.M.; Akter, A.; Khaleduzzaman, A.B.M.; Sultana, M.N.; Hemme, T. Application of the farm simulation model approach on economic loss estimation due to Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Bangladesh dairy farms—Strategies, options, and way forward. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffolani, G.; Bentivoglio, D.; Finco, A. Economic assessment of small-scale mountain dairy farms by using accounting data: Evidence from an Italian case study. AGRIS On-Line Pap. Econ. Inform. 2024, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.; van Middelaar, C.E.; Mostert, P.F.; van Knegsel, A.T.M.; Kemp, B.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Hogeveen, H. Effects of dry period length on production, cash flows and greenhouse gas emissions of the dairy herd: A dynamic stochastic simulation model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezat-Jarzebowska, A.; Rembisz, W. Modeling the profitability of milk production—A simulation approach. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas-Domínguez, R.R.; Del Razo-Rodríguez, O.E.; Almaraz-Buendía, I.; Peláez-Acero, A.; Espinosa-Muñoz, V.; Rebollar-Rebollar, S.; Salinas-Martínez, J.A. Evaluation of comparative advantages in the profitability and competitiveness of the small-scale dairy system of Tulancingo Valley, Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018, 50, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Martínez, J.A.; Posadas-Domínguez, R.R.; Morales-Díaz, L.D.; Rebollar-Rebollar, S.; Rojo-Rubio, R. Cost analysis and economic optimization of small-scale dairy production systems in Mexico. Livest. Sci. 2020, 237, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. Decomposing variation in dairy profitability: The impact of output, inputs, prices, labour and management. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.C.; Salkind, N.J. Handbook of Research Design & Social Measurement, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.W.; Klose, S.L.; Gray, A.W. An applied procedure for estimating and simulating multivariate empirical (MVE) probability distributions in farm level risk assessment and policy analysis. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, V.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Rogers-Montoya, N.A.; Martínez-García, C.G.; Salinas-Martínez, J.A.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E. Economic and financial performance of representative small-scale dairy production units to 2027. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2024, 27, 057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Castañeda, F.E.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Cuevas-Reyes, O.; Rogers-Montoya, N.A.; Gómez-Tenorio, G.; Trujillo-Ortega, M.E.; Peñuelas-Rivas, C.G.; Hernández, E. Economic and financial viability of a pig farm in central semi-tropical Mexico: 2022–2026 prospective. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (SADER). Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta (SIACON). Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/dgsiap/prensa/sistema-de-informacion-agroalimentaria-de-consulta-siacon?idiom=es (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Richardson, J.W. Simulation and Econometrics to Analyze Risk; Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.W. Simulation for Applied Risk Management; Agricultural and Food Policy Center, Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García, C.G.; Rayas-Amor, A.A.; Anaya-Ortega, J.P.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E.; Espinoza-Ortega, A.; Prospero-Bernal, F.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Performance of small-scale dairy farms in the highlands of central Mexico during the dry season under traditional feeding strategies. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel-Molina, O.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Barba, C.; Rangel, J.; García, A. Does Gender Impact Technology Adoption in Dual-Purpose Cattle in Mexico? Animals 2022, 12, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ableeva, A.; Salimova, G.; Gusmanov, R.U.; Lubova, T.N.; Eφимов, O.H.; Farrahetdinova, A. The Role of Agriculture in the Formation of Macroeconomic Indicators of National Economy. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2019, 15, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, W.H. The Farm Economies of the Plains: Comment. Rev. Reg. Stud. 1987, 17, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, D.; Howland, O.; Loiske, V.-M.; Mnzava, M.; Noe, C. Economic growth, rural assets and prosperity: Exploring the implications of a 20-year record of asset growth in Tanzania. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2018, 56, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belongia, M.T.; Gilbert, R.A. The Farm Economies of the Plains. Rev. Reg. Stud. 1987, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.C.U.; González-Quiñónez, L.A.; Reyna-Tenorio, L.J.; Salgado-Ortiz, P.J.; Chere-Quiñónez, B.F. Renewable Energy Development and Employment in Ecuador’s Rural Sector: An Economic Impact Analysis. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, M.W.; Masuku, M.M. Small-Scale Agriculture as a Panacea in Enhancing South African Rural Economies. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2018, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qili, M.; Zhao, Z.; Bao, J.; Wu, N.; Gou, B.; Ying, Y.; Bilige, B.; Sun, L.; Xue, Y.; Yang, F. Nitrogen use efficiencies, flows, and losses of typical dairy farming systems in Inner Mongolia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1433129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, M.C.; Pohler, K.G. North American perspectives for cattle production and reproduction for the next 20 years. Theriogenology 2025, 232, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, S.; Neethirajan, S. Integrating artificial intelligence in dairy farm management: Biometric facial recognition for cows. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Law, J.; Mosheim, R. Consolidation in U.S. Dairy Farming; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ERR-274. [Google Scholar]

- Amber Waves—USDA ERS. Scale Economies Provide Advantages to Large Dairy Farms. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2020/august/scale-economies-provide-advantages-to-large-dairy-farms (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo Agropecuario 2022: Resultados Definitivos. Nacional; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2023. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/ca/2022/doc/ca2022_rdnal.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Freitas, E.N.A.; Cabrera, V.E. Dairy Victory Platform: A novel benchmarking platform to empower economic decisions on dairy farms. JDS Commun. 2024, 6, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Covarrubias, L.; Läpple, D.; Dillon, E.; Thorne, F. The role of hired labour on technical efficiency in an expanding dairy sector: The case of Ireland. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2024, 68, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). Farm Income and Wealth Statistics: Farm Business Average Net Cash Income; USDA ERS: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=4046 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Shanmugam, P.M.; Sangeetha, S.P.; Prabu, P.C.; Varshini, S.V.; Renukadevi, A.; Ravisankar, N.; Parasuraman, P.; Parthipan, T.; Satheeshkumar, N.; Natarajan, S.K.; et al. Crop–livestock integrated farming system: A strategy to achieve synergy between agricultural production, nutritional security, and environmental sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1338299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdine, K.H.; Kusunose, Y.; Maynard, L.J.; Blayney, D.P.; Mosheim, R. Livestock Gross Margin–Dairy: An assessment of its effectiveness as a risk management tool and its potential to induce supply expansion. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolf, C.A.; Widmar, N.J.O. Adoption of milk and feed forward pricing methods by dairy farmers. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, E.; Yu, X.; Trestini, S. The role of trust and perceived barriers on farmer’s intention to adopt risk management tools. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2020, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Martínez, M.A.; Vera-Ávila, H.R.; Estrada-Cortés, E.; Ruiz-López, F.J.; Montiel-Olguín, L.J. Effects of assisted calving and retained fetal membranes on milk production in the smallholder farming system. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2025, 27, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirimi, A.K.; Nyarindo, W.N.; Gatimbu, K.K. Is adoption of modern dairy farming technologies interrelated? A case of smallholder dairy farmers in Meru County, Kenya. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitmun, T.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Datta, A.; Anal, A.K. Factors influencing membership of dairy cooperatives: Evidence from dairy farmers in Thailand. J. Coop. Organ. Manag. 2020, 8, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Shalloo, L.; Pierce, K.M.; Horan, B. Evaluating expansion strategies for startup European Union dairy farm businesses. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 4059–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.M.; Benson, G.A. Roles and responsibilities of the manager. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; McSweeney, P.L.H., McNamara, J.P., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Navarro, E.; Faure, G.; Cortijo, E.; De Nys, E.; Bogue, J.; Gómez, C.; Mercado, W.; Gamboa, C.; Le Gal, P.-Y. The impacts of differentiated markets on the relationship between dairy processors and smallholder farmers in the Peruvian Andes. Agric. Syst. 2015, 132, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taramuel-Taramuel, J.P.; Aza-Fuelantala, O.E.; Ader, D.; Mayorga, A.; Barrios, D. Technology adoption in smallholder dairy farms in Indigenous Pastos communities of Colombia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Renwick, A.; Zhou, X. Short communication: The relationship between farm debt and dairy productivity and profitability in New Zealand. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8251–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzelak, A.; Staniszewski, J. Relative return on assets in farms and its economic and environmental drivers: Perspective of the European Union and the Polish region Wielkopolska. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.; Bevan, K.; Moxey, A.; Grierson, S.; Toma, L. Identifying best practice in Less Favoured Area mixed livestock systems. Agric. Syst. 2023, 208, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.; Neal, J.; Fulkerson, W. Optimal choice of dairy forages in eastern Australia. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 3044–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, L.; Dalton, T. Factors affecting the decision to exit dairy farming: A two-stage regression analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 3092–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, S.H.; Adnan, K.M.M.; Baimbill Johnson, S.; Talukder, A.A.; Yu, M.; Osei, E. Challenges and solutions for small dairy farms in the U.S.: A review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Ma, C.; Kang, Y.; Jia, Y. Why is dairy production so difficult to stabilize? Research on the micro-mechanism and transformation mechanism of cyclical fluctuations of raw milk prices in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1655741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Benni, N.; Finger, R. Gross revenue risk in Swiss dairy farming. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.; Luta, G.; Wilcox, R. On testing the equality between interquartile ranges. Comput. Stat. 2024, 39, 2873–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, C.; Areal, F.J.; Semenov, M.A.; Senapati, N.; Shield, I.F.; Bishop, J. Stability of farm income: The role of agricultural diversity and agri-environment scheme payments. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, J.M.; Mishra, A.K.; Blayney, D. Assessing participation in the Milk Income Loss Contract program and its impact on milk production. J. Policy Model. 2013, 35, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouan, J.; Ridier, A.; Carof, M. SYNERGY: A regional bio-economic model analyzing farm-to-farm exchanges and legume production to enhance agricultural sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 175, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Gutiérrez, M.R.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Rogers-Montoya, N.A.; González-Hernández, V.; González-López, R.; Martínez-García, C.G.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E. Prospectiva ambiental al 2030 en sistemas de producción de leche de vaca en México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2023, 14, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Ureta, B.E.; Wall, A.; Neubauer, F. Dairy farming from a production economics perspective: An overview of the literature. In Handbook of Production Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, A.; Lips, M. Influence of milk yield on profitability—A quantile regression analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8350–8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, L.; Manning, L.; Moore, H.L.; Lindahl, J.F.; Gemechu, G.; Mihret, A.; Berg, S.; Wood, J.L.N.; Nyokabi, N.S. Adoption of dairy technologies in smallholder dairy farms in Ethiopia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1070349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, N.; Garnett, T.; Lorimer, J. Dairy intensification: Drivers, impacts and alternatives. Ambio 2020, 49, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.H.K.; Lim, W.M.; Yii, K.J. Financial planning behaviour: A systematic literature review and new theory development. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2024, 29, 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämö, J.; Tupek, B.; Lehtonen, H.; Mäkipää, R. Towards climate targets with cropland afforestation—Effect of subsidies on profitability. Land Use Policy 2023, 124, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livest. Sci. 2010, 130, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Zurita, J.; Oswald-Spring, Ú. Modeling water availability under climate change scenarios: A systemic approach in the metropolitan area in Morelos, México. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1466380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Austria, P.F. Climate change and water resources in Mexico. In Water Resources of Mexico; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, J.O.; Robling, H.; Cederberg, C.; Spörndly, R.; Lindberg, M.; Martiin, C.; Ardfors, E.; Tidåker, P. What can we learn from the past? Tracking sustainability indicators for the Swedish dairy sector over 30 years. Agric. Syst. 2023, 212, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Campêlo, V.R.; Paradis, M.-E.; Arango-Sabogal, J.C.; Beauregard, N.; Roy, J.-P.; Racicot, M.; Aenishaenslin, C.; Dufour, S. Biosecurity adoption in Québec dairy farms: Results from a risk assessment questionnaire analyzed using conventional and unsupervised artificial intelligence methods. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6000–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, P.; Barkema, H.W.; Osei, P.P.; Taylor, J.; Shaw, A.P.; Conrady, B.; Chaters, G.; Muñoz, V.; Hall, D.C.; Apenteng, O.O.; et al. Global losses due to dairy cattle diseases: A comorbidity-adjusted economic analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6945–6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Gutiérrez, M.R.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E.; Rogers-Montoya, N.A.; Martínez-Campos, A.R.; Gómez-Tenorio, G.; Velazquez, L.; Peñuelas-Rivas, C.G. Environmental impacts of medium-scale pig farming at technical and economic optimum production weight in Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V.E. Invited review: Helping dairy farmers to improve economic performance utilizing data-driven decision support tools. Animal 2018, 12, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFRACA; FAO. Agricultural Value Chain Finance Innovations and Lessons—Case Studies in Africa, 2nd ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarica, D.; Demircan, V.; Naziroglu, A.; Aydin, O.; Koknaroglu, H. The cost and profitability analysis of different dairy farm sizes. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Qin, S.; Anwar, M.; Zhou, Y. Technical Efficiency, Economic Sustainability, and Environmental Implications of Dairy Farms in Pakistan. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 34, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.N.F.A.; Cavalcanti Neto, I.; Pereira, C.V.M.; do Nascimento Ramalho, J.A.; Ferreira, J.C.V.; Cunha, P.E.V.; Costa, C.W. Spatial assessment and prioritization strategies for water erosion-induced soil loss in the Brazilian semiarid. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2025, 162, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Ahmadi Bouda, V.; Barratt, A.S.; Thomson, S.G.; Stott, A.W. Financial vulnerability of dairy farms challenged by Johne’s disease to changes in farm payment support. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullock, K.; Hoag, D.L.; Parsons, J.; Lacy, M.; Seidel, G.E., Jr.; Wailes, W. Factors affecting economics of using sexed semen in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 6366–6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M.; Hansen, J.K.; Lamers, P.; Thrän, D. Making money from waste: The economic viability of producing biogas and biomethane in the Idaho dairy industry. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.M.; Parsons, R.L.; Kolodinsky, J.; Matiru, G.N. A cost and returns evaluation of alternative dairy products to determine capital investment and operational feasibility of a small-scale dairy processing facility. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2506–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Torres, M.E.; García-Martínez, A.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M.; Dorward, P.; Rayas-Amor, A.A.; Martínez-García, C.G. Role of small-scale dairy production systems in central Mexico in reducing rural poverty. Exp. Agric. 2022, 58, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzonko, A.; Wojewodzic, T.; Czekaj, M.; Płonka, R.; Parzonko, A.J. Remuneration for own labour in family-run dairy farms versus the salaries and wages in non-agricultural sectors of the economy—Evaluation of the situation in Poland in 2005–2022. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Jiménez, R.A.; Espinosa Ortiz, V.; Soler Fonseca, D.M. El costo de oportunidad de la mano de obra familiar en la economía de la producción lechera de Michoacán, México. Rev. Investig. Agrar. Ambient. 2014, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; García-Cornejo, B.; Pérez-Méndez, J.A.; Roibás, D. Value-creating strategies in dairy farm entrepreneurship: A case study in northern Spain. Animals 2021, 11, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetroiu, R.; Cișmileanu, A.E.; Cofas, E.; Petre, I.L.; Rodino, S.; Dragomir, V.; Marin, A.; Turek-Rahoveanu, P.A. Assessment of the relations for determining the profitability of dairy farms, a premise of their economic sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Li, J.; Qu, Y. Green total factor productivity of dairy cow in China: Key facts from scale and regional sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wei, L.; Wang, W. Review: Challenges and prospects for milk production in China after the 2008 milk scandal. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 37, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, V.A.; Owuor, G.; Rao, E.J.; Otieno, D.J. Impact of cooperatives on smallholder dairy farmers’ income in Kenya. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2291225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Martínez, J.A.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M.; Herrera-Tapia, F.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E. Transición generacional de los establos lecheros en pequeña escala como elemento de sustentabilidad. In La Ganadería en la Seguridad Alimentaria de las Familias Campesinas; Cavallotti, V.B.A., Rojo, M.G.E., Ramírez, V.B., Cesín, V.A., Marcof, A.C.F., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH): Chapingo, Mexico, 2013; pp. 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Contreras, E.A.; Valtierra-Pacheco, E. Consecuencias de la urbanización en la lechería familiar de Cerrito Colorado en Querétaro, México. Econ. Soc. Territ. 2025, 25, e2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas-Domínguez, R.R.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E. Economic and financial viability of small-scale dairy systems in central Mexico: Economic scenario 2010–2018. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachura, P. The Economic Geography of Globalization. In InTech eBooks; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.C.; Cárdenas, J.R.A.; Ángel, M.; Islas-Moreno, A. Pequeñas empresas productoras de leche: Un estudio desde la perspectiva del modelo de negocio. Innovar 2022, 32, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hernández, S.; López-González, F.; Prospero-Bernal, F.; Martínez-García, C.G.; Flores, G.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Estimación De Emisión De Metano Entérico En Sistemas De Producción De Leche Bovina En Pequeña Escala Bajo Diferentes Estrategias De Alimentación. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2021, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, L.J.; Chiumia, D.; Gondwe, T.N.; Gondwe, S.R. Smallholder Dairy Farming Contributes to Household Resilience, Food, and Nutrition Security besides Income in Rural Households. Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, D.J.; Chirwa, E.W.; Dorward, A.; Ruffhead, H.J.; Hill, R.; Osborn, J.; Langer, L.; Harman, L.; Asaoka, H.; Coffey, C.; et al. Agricultural Input Subsidies for Improving Productivity, Farm Income, Consumer Welfare and Wider Growth in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2018, 14, 1–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel Quintos, J. Estrategias de Vida del Productor Agropecuario en Zonas Periurbanas Como Forma de Adaptación al Medio: Caso de San Andrés Mixquic y San Nicolás Tetelco. Master’s Thesis, Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Estado de México, Mexico, 2001; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez, A.; Rivas-Rangel, J.; Rangel-Quintos, J.; Espinosa, J.A.; Barba, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C. A Methodological Approach to Evaluate Livestock Innovations on Small-Scale Farms in Developing Countries. Future Internet 2016, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Representative Smallholder Dairy Farms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Crop market receipts (CMR) | 2023 | USD 0.00 | USD 0.00 | USD 0.00 | USD 16.75 | USD 12.48 |

| 2033 | USD 0.00 | USD0.00 | USD 0.00 | USD 29.58 | USD 20.60 | |

| Dairy receipts (DR) | 2023 | USD 17.82 | USD 28.29 | USD 19.58 | USD 32.03 | $USD 26.85 |

| 2033 | USD 23.36 | USD 37.61 | USD 25.77 | USD 51.66 | USD 42.15 | |

| Total income (TI) | 2023 | USD 17.82 | USD 28.29 | USD 19.58 | USD 51.44 | USD 39.33 |

| 2033 | USD 23.36 | USD 37.61 | USD 25.77 | USD 85.37 | USD 62.75 | |

| Total expenditure (TE) | 2023 | USD 12.04 | USD 21.53 | USD 3.83 | USD 41.27 | USD 36.93 |

| 2033 | USD 15.00 | USD 26.65 | USD 10.45 | USD 52.31 | USD 45.58 | |

| Net cash farm income (NCFI) | 2023 | USD 5.78 | USD 6.77 | USD 15.74 | USD 10.17 | USD 2.41 |

| 2033 | USD 8.36 | USD 10.96 | USD 15.32 | USD 33.01 | USD 17.17 | |

| Ending cash reserves (ECR) | 2023 | USD 16.22 | USD 12.57 | USD 20.84 | USD 15.38 | USD 2.41 |

| 2033 | USD 324.18 | USD 270.89 | USD 364.29 | USD 576.37 | USD 220.40 | |

| Net cash (NC) | 2023 | USD 121.33 | USD 209.07 | USD 53.29 | USD 165.36 | USD 284.96 |

| 2033 | USD 453.16 | USD 517.01 | USD 364.29 | USD 734.90 | USD 535.82 | |

| Return on Assets (ROA, %) | 2023 | −USD 9.18 | USD 17.61 | USD 131.81 | USD 32.62 | $USD 4.56 |

| 2033 | USD 15.00 | USD 11.53 | USD 17.72 | USD 21.75 | USD 17.40 | |

| Representative Smallholder Dairy Farms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Internal Rate of return (%) | 14 | 12 | 26 | 16 | 6 |

| Ratio Cost/Benefit (mean) | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.59 | 1.17 |

| Net Present Value (Thousand USD) | USD 98,837.90 | USD 110,124.00 | USD 344,005.08 | USD 83,147.33 | −USD 41,822.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers-Montoya, N.A.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Herrera-Haro, J.G.; Vilchis-Granados, G.B.; Cruz-Olayo, A.; Domínguez-Olvera, D.A.; González-López, R.; Ruiz-Torres, M.E.; Zarco-González, M.M.; et al. Economic and Financial Performance of Smallholder Dairy Farms in the Mexican Highlands: Prospective to 2033. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242593

Rogers-Montoya NA, Martínez-Castañeda FE, Callejas-Juárez N, Herrera-Haro JG, Vilchis-Granados GB, Cruz-Olayo A, Domínguez-Olvera DA, González-López R, Ruiz-Torres ME, Zarco-González MM, et al. Economic and Financial Performance of Smallholder Dairy Farms in the Mexican Highlands: Prospective to 2033. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242593

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers-Montoya, Nathaniel Alec, Francisco Ernesto Martínez-Castañeda, Nicolás Callejas-Juárez, José Guadalupe Herrera-Haro, Gabriela Berenice Vilchis-Granados, Ariana Cruz-Olayo, Daniel Alonso Domínguez-Olvera, Rodrigo González-López, Monica Elizama Ruiz-Torres, Martha Mariela Zarco-González, and et al. 2025. "Economic and Financial Performance of Smallholder Dairy Farms in the Mexican Highlands: Prospective to 2033" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242593

APA StyleRogers-Montoya, N. A., Martínez-Castañeda, F. E., Callejas-Juárez, N., Herrera-Haro, J. G., Vilchis-Granados, G. B., Cruz-Olayo, A., Domínguez-Olvera, D. A., González-López, R., Ruiz-Torres, M. E., Zarco-González, M. M., & Martínez-Campos, A. R. (2025). Economic and Financial Performance of Smallholder Dairy Farms in the Mexican Highlands: Prospective to 2033. Agriculture, 15(24), 2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242593