Abstract

Coleoptera, specifically leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae) and weevils (Curculionidae), are the dominant pests in tea plantations, significantly impacting tea yield and quality. Insect endosymbiont microbial communities play a crucial role in the physiological metabolism and pathogenicity of their hosts. However, there is still a lack of understanding regarding the composition and function of these communities in coleopteran pests in tea plantations. This study utilized high-throughput sequencing technology to analyze the composition and function of the endosymbiont microbial communities in four species of coleopteran insects from tea plantations. The results indicated that at the phylum level, the dominant bacteria in both leaf beetles and weevils were Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, while the dominant fungi were Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. At the genus level, the primary dominant bacteria in leaf beetles were Enterobacter and Lactococcus, whereas in weevils, they were Klebsiella, Pantoea, and Cedecea. The dominant fungi in leaf beetles consisted of Mortierella, Fusarium, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, and Penicillium, while those in weevils were Aspergillus, Thelebolus, Cladosporium, and Fusarium. Each species harbored its own distinct set of dominant genera. Furthermore, the abundance profiles of shared and unique bacterial and fungal genera revealed distinct characteristics in leaf beetles versus weevils. Although overall microbial diversity did not differ significantly among the four species, their bacterial community structures varied markedly. Functional prediction indicated ‘Plant Pathogen’ as the predominant type in leaf beetles, contrasting with ‘Membrane Transport’ in weevils. These findings provide a foundation for understanding endosymbionts in tea plantation beetles and their potential interactions with host insects.

1. Introduction

Pests and diseases represent a major constraint on tea production. In recent years, innovations in cultivation techniques, the diversification of planting systems, and pest control interventions have altered the insect community structure and reduced biodiversity within tea agroecosystems. These changes have led to the emergence of previously minor pests and diseases as major economic threats [1,2]. With consumption upgrading and growing health consciousness, there has been an increasing demand for green, organic, and high-quality tea products, consequently raising the quality standards for tea. However, the high yield and quality of premium tea have been consistently threatened by pest infestations in tea plantations. Tea pests encompass a wide variety of species, primarily including Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Lepidoptera, Thysanoptera, Orthoptera, and Acari [3,4]. Coleoptera contributes a significant number of pest species in tea plantations, such as leaf beetles, weevils, and longhorn beetles [5,6,7].

Diverse insect endosymbionts are ubiquitous and represent an integral component of their microecology. These endosymbionts perform diverse functions that play a pivotal role in the life activities of their hosts, including, but not limited to, nutrient provisioning, metabolic support, defense assistance, and reproductive manipulation [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The taxonomic composition, population density, and spatial distribution of insect endosymbionts are governed by a spectrum of factors, notably the host insect’s identity, its developmental phase, and ambient environmental conditions [14,15]. Research on endosymbionts in coleopteran insects currently focuses predominantly on bacterial taxa within the gut microbiota. For instance, in the bark beetle Dendroctonus armandi, the larval gut bacterial community during overwintering is primarily composed of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes [16]. The larval intestinal microbiota of Titocerus jaspideus and Passalus punctiger is dominated by Lactococcus, a genus noted for its beneficial probiotic characteristics [17]. The gut bacterial of lesser mealworms predominantly comprises the genera Kluyvera, Lactococcus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Enterococcus [18]; Dietary habit constitutes a pivotal factor in structuring the intestinal bacterial diversity of insects. A case in point is observed in stag beetle larvae, where although compositional differences exist across developmental phases, the core bacterial community remains dominated by Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria. Functional profiling further demonstrates distinct metabolic specialization: wood-feeding larvae harbor gut microbiota predominantly engaged in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, whereas fungus-feeding specimens exhibit upregulated activities related to membrane transport systems [19]. In addition, parental transmission and intergenerational vertical transfer of gut microbiota occur in coleopteran insects, as documented in Nicrophorus spp. (burying beetles) (Nicrophorus spp.) and Galerucella [20,21]. Nevertheless, existing studies on endosymbionts in coleopteran insects have thus far covered only a limited range of species, with research on non-gut microbiota and fungal communities remaining particularly underdeveloped. Therefore, investigation of both bacterial and fungal endosymbionts in coleopteran insects is essential for a comprehensive understanding of their characteristics and functional roles.

China is recognized as the centre of origin of tea and the world’s largest tea producer, with its cultivation predominantly concentrated in the southern regions. Guizhou Province represents one of the key tea-producing areas in the country. A total of 497 pest species, encompassing 91 families within 11 orders, have been documented in Guizhou’s tea plantations. Coleoptera represent the most dominant order. Particularly widespread are pests from the leaf beetle and weevil species [7,22]. Nevertheless, current understanding of endosymbiotic microbes in coleopteran pests infesting tea plantations remains limited. To address this knowledge gap, the present investigation employs 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing to characterize the endosymbiotic bacterial and fungal communities in four predominant coleopteran pests (3 leaf beetles: Gallerucida bifasciata, Plagiodera versicolora, Humba cyanicollis and Myllocerinus aurolineatus) in tea ecosystems. This research aims to elucidate the structural and functional profiles of these microbial assemblages, with the anticipated outcomes expected to inform future strategies for integrated pest management targeting coleopteran species in tea cultivation systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Identification

The research was conducted in a tea plantation located in Huaxi District (26.5249796° N, 106.6139724° E; elevation 1347.63 m). The samples were collected on 21 June 2025. Guiyang City, southwestern China’s Guizhou Province. Four species of coleopteran pests were collected in the study area during the summer tea harvest period (June) using a standardized sweep netting method. This sampling timeframe coincided with the vigorous vegetative growth stage of tea plants, characterized by dense canopy formation of mature banjhi leaves. All insects were collected at the adult stage using a 38 cm diameter insect net through targeted sweeping of observed aggregation areas in the tea canopy. The collected species included: G. bifasciata (GB, n = 3), P. versicolora (PV, n = 3), M. aurolineatus (MA, n = 3), and H. cyanicollis (HC, n = 3). Species identification was conducted morphologically [23,24,25].

2.2. Sample Processing

All insect specimens were subjected to a 48 h fasting treatment prior to analysis to remove transient dietary microbes and normalize intestinal contents [19]. The samples were first subjected to surface sterilization by immersion in 75% ethanol for one minute, followed by three washes with sterile water. This was succeeded by a three-minute treatment with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution and another three sterile water rinses. After surface disinfection, each sample was transferred to a sterile 2 mL centrifuge tube, homogenized using a cryogenic grinder, and ultimately stored at −80 °C.

2.3. DNA Extraction, Amplicon Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Total DNA was extracted from each sample and subjected to PCR amplification. The V3–V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [26]. The fungal ITS1 region was amplified with primers ITS1 (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). Following purification and quality control verification, the amplified PCR products underwent high-throughput amplicon sequencing. This sequencing service was provided by Biomarker Technologies Co. (Beijing, China) utilizing the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Raw sequencing reads underwent quality control with Trimmomatic 0.33 and primer removal with Cutadapt 1.9.1, allowing a maximum mismatch rate of 20% and requiring a minimum coverage of 80%. Paired-end reads were assembled using Usearch 10 under the criteria of a minimum 10 bp overlap, 90% overlap similarity, and a maximum of 5 bp mismatches. Chimeric sequences were subsequently removed with UCHIME 8.1. The resulting high-quality sequences were denoised using the DADA2 plugin within QIIME2 to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which were filtered using a conservative abundance threshold of 0.005%.

In this study, deep sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 region generated a total of 1,315,613 raw reads from 12 samples. After quality control and processing, 1,122,345 high-quality reads were obtained, which were clustered into 4027 ASVs. High-throughput sequencing of the fungal ITS1 region generated 1,296,237 raw reads across the 12 samples. After rigorous quality filtering, 1,051,952 high-quality sequences were retained, which subsequently produced 3544 ASVs. Bacterial and fungal ASVs were taxonomically classified against the SILVA (Release 138) and UNITE (Release 8.0) databases, respectively, using a confidence threshold of 70%. The bacterial functions were predicted using PICRUSt2 [27], and the fungal functions were predicted using FUNGuild [28].

2.4. Data Analyses

Statistical analysis of endosymbiont data was implemented through an integrated analytical workflow. The ggpubr and vegan packages in R 4.3.2 facilitated nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum testing and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). Normality assessment and comparative analyses were executed in SPSS 26.0, while GraphPad Prism 9.0 enabled comprehensive visualization of microbial composition, functional attributes, and diversity patterns.

3. Results

3.1. Endosymbiont Composition and Diversity

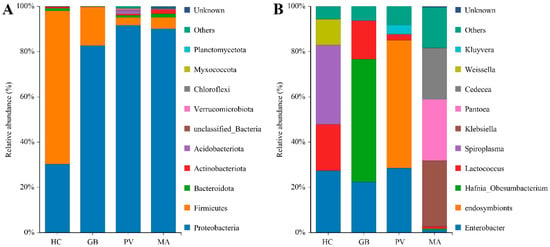

The bacterial endosymbiont communities across the four coleopteran species encompassed a broad taxonomic diversity, spanning 2 kingdoms, 35 phyla, 76 classes, 183 orders, 345 families, and 679 genera in total. Species-specific analysis revealed distinct patterns: H. cyanicollis contained microorganisms from 2 kingdoms, 20 phyla, 33 classes, 77 orders, 129 families, and 210 genera; G. bifasciata hosted 2 kingdoms, 14 phyla, 17 classes, 39 orders, 77 families, and 105 genera; P. versicolora exhibited the richest diversity with 2 kingdoms, 31 phyla, 67 classes, 159 orders, 280 families, and 471 genera; while M. aurolineatus comprised 2 kingdoms, 22 phyla, 38 classes, 80 orders, 132 families, and 235 genera (Table S1). At the phylum level, the endosymbiont bacterial communities across the four insect species were primarily constituted by Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Acidobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota, Chloroflexi, Myxococcota, and Planctomycetota (Figure 1A). Among them, distinct dominance patterns were observed among the species: G. bifasciata, P. versicolora and M. aurolineatus demonstrated marked predominance of Proteobacteria (82.70–91.65%), supplemented by Firmicutes (3.52–17.12%). Conversely, H. cyanicollis displayed a contrasting configuration where Firmicutes represented the major constituent (67.72%), with Proteobacteria comprising a secondary proportion (30.29%). At the genus level, the bacterial communities across the four insect species primarily consisted of Enterobacter, endosymbionts, Hafnia-Obesumbacterium, Lactococcus, Spiroplasma, Klebsiella, Pantoea, Cedecea, Weissella, and Kluyvera; however, the specific dominant genus varied significantly across the different insect hosts (Figure 1B). Specifically, the dominant genera in H. cyanicollis were Enterobacter (27.34%), Spiroplasma (35.01%), Lactococcus (20.46%), and Weissella (11.39%). G. bifasciata was primarily dominated by Hafnia-Obesumbacterium (54.26%), Enterobacter (22.44%), and Lactococcus (16.94%). P. versicolora showed predominance of endosymbionts (56.52%), Enterobacter (28.54%), Kluyvera (3.91%), and Lactococcus (2.37%), while M. aurolineatus exhibited dominance of Klebsiella (29.00%), Pantoea (27.08%), Cedecea (22.65%), and Enterobacter (1.26%).

Figure 1.

Relative abundance of endosymbiotic bacteria at the phylum and genus levels ((A): phylum level; (B): genus level). The abbreviations HC, GB, PV, and MA are used hereafter for Humba cyanicollis, Gallerucida bifasciata, Plagiodera versicolora, and Myllocerinus aurolineatus, respectively.

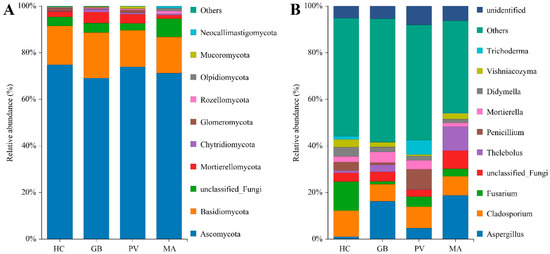

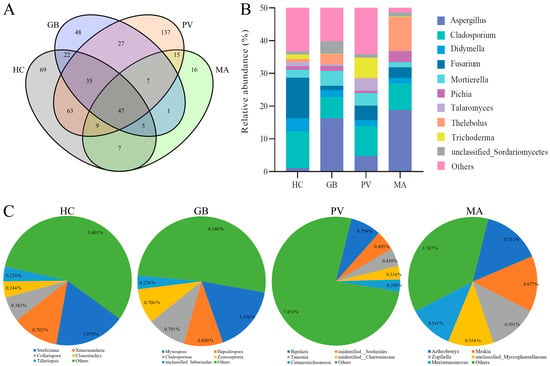

The endosymbiotic fungi identified from the four insect species collectively spanned 1 kingdom, 14 phyla, 43 classes, 100 orders, 220 families, and 433 genera. Species-specific analysis demonstrated varying levels of fungal diversity: H. cyanicollis contained 11 phyla, 31 classes, 74 orders, 143 families, and 224 genera; G. bifasciata comprised 10 phyla, 30 classes, 63 orders, 122 families, and 167 genera; P. versicolora included 11 phyla, 33 classes, 78 orders, 154 families, and 288 genera; while M. aurolineatus exhibited the most limited diversity with 9 phyla, 19 classes, 43 orders, 72 families, and 96 genera (Table S1). At the phylum level, the endosymbiotic fungal communities across the four insect species were predominantly composed of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, unclassified Fungi, Mortierellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Rozellomycota, Olpidiomycota, Mucoromycota, and Neocallimastigomycota (Figure 2A). All four insect species demonstrated a consistent fungal community structure at the phylum level, with Ascomycota representing the predominant phylum (69.12–74.87%). Basidiomycota constituted the secondary major component (15.51–19.51%), while unclassified Fungi (2.99–7.84%) and Mucoromycota (1.57–4.72%) were consistently present as minor but notable constituents. At the genus level, the fungal communities across the four insect species were primarily composed of Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Fusarium, Thelebolus, Penicillium, Mortierella, Didymella, Vishniacozyma, and Trichoderma, though the dominant genera varied among different insect species (Figure 2B). Analysis of genus-level fungal dominance revealed distinct species-specific patterns: H. cyanicollis exhibited predominant representation of Fusarium (12.44%), Cladosporium (11.18%), Didymella (4.01%), and Penicillium (3.72%). G. bifasciata demonstrated a fungal profile dominated by Aspergillus (16.26%), supplemented by Cladosporium (7.26%), Mortierella (4.56%), and Thelebolus (3.07%). The mycobiota of P. versicolora displayed a more diversified structure with Cladosporium (9.11%), Penicillium (8.57%), Trichoderma (6.15%), Aspergillus (4.77%), Fusarium (4.38%), and Mortierella (3.85%) as major constituents. In contrast, M. aurolineatus showed a configuration characterized by Aspergillus (18.80%), Thelebolus (10.26%), Cladosporium (8.12%), and Fusarium (3.27%).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of endosymbiotic fungi at the phylum and genus levels ((A): phylum level; (B): genus level).

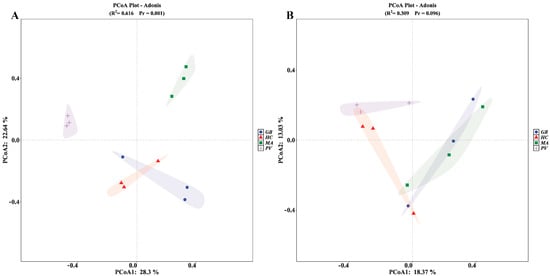

Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests revealed no statistically significant differences in either Simpson or Shannon indices for both bacterial and fungal communities across the four insect species (p > 0.05), indicating comparable levels of endosymbiont diversity among all examined specimens (Figure S1). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on binary Jaccard dissimilarity revealed significant compositional divergence in bacterial communities among the four insect species (R2 = 0.616, p = 0.001; Figure 3A). The ordination demonstrated clear separation of P. versicolora and M. aurolineatus from other species, while H. cyanicollis and G. bifasciata formed overlapping clusters, indicating negligible structural differentiation between these two species. Fungal communities, however, showed no statistically significant interspecific differentiation (R2 = 0.309, p = 0.096; Figure 3B), despite observable separation of P. versicolora from both G. bifasciata and M. aurolineatus, suggesting species-specific mycobiome patterning in the former.

Figure 3.

PCoA of endosymbiotic bacterial and fungal communities across the four insect species ((A): bacteria; (B): fungi).

3.2. Shared and Unique Taxa of Endosymbionts

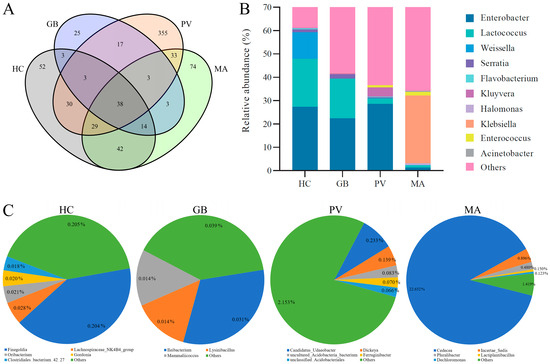

The analysis of endosymbiotic bacterial genera revealed 38 shared operational taxonomic units across all four insect species. Species-specific distributions showed that H. cyanicollis, G. bifasciata, P. versicolora, and M. aurolineatus possessed 52, 25, 355, and 74 unique genera, respectively (Figure 4A). Among the shared genera, the five most relatively abundant were Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Lactococcus, Weissella, and Kluyvera (Figure 4B). The relative abundances of these common genera exhibited substantial variation across the different insect species. The relative abundance profiles of the core bacterial genera revealed species-specific distribution patterns: H. cyanicollis was characterized by substantial representation of Enterobacter (27.34%), Lactococcus (20.46%), Weissella (11.39%), and Serratia (1.35%). G. bifasciata exhibited comparable dominance of Enterobacter (22.44%) and Lactococcus (16.94%), accompanied by Serratia (1.82%). In contrast, P. versicolora demonstrated predominant abundance of Enterobacter (28.54%), with secondary representation of Kluyvera (3.91%) and Lactococcus (2.37%). Notably, M. aurolineatus displayed a divergent profile dominated by Klebsiella (29.00%), while maintaining minimal proportions of Enterococcus (1.55%) and Enterobacter (1.26%). The unique genera accounted for minimal proportions in the endosymbiotic bacterial communities of the four insect species, with the notable exception of Cedecea in M. aurolineatus (Figure 4C). Specifically, unique taxa represented merely 0.50% of the total community in H. cyanicollis, predominantly comprising Finegoldia (0.20%); 0.10% in G. bifasciata, primarily represented by Ileibacterium (0.03%); and 2.74% in P. versicolora, mainly consisting of Candidatus Udaeobacter (0.23%) and Dickeya (0.14%). In contrast, M. aurolineatus exhibited a substantially higher proportion of unique genera at 25.72%, dominated by Cedecea (22.65%), with additional contributions from Incertae Sedis of Erwiniaceae (0.90%) and Pluralibacter (0.48%).

Figure 4.

Shared and unique genera of endosymbiotic bacteria among the four insect species ((A): Shared genera; (B): Abundance of shared genus; (C): Unique genera).

The endosymbiotic fungal communities across the four insect species shared 47 common genera, while exhibiting distinct species-specific patterns: H. cyanicollis, G. bifasciata, P. versicolora, and M. aurolineatus possessed 69, 48, 137, and 16 unique genera, respectively (Figure 5A). Among the shared taxa, the five most relatively abundant genera were Aspergillus, Fusarium, Cladosporium, Thelebolus, and Trichoderma (Figure 5B). Substantial interspecific variation was observed in the relative abundance distribution of these core fungal genera: H. cyanicollis was predominantly characterized by Fusarium (12.44%), Cladosporium (11.18%), and Didymella (4.01%); G. bifasciata showed dominant representation of Aspergillus (16.26%), Cladosporium (6.47%), and Mortierella (4.56%); P. versicolora exhibited a diversified profile with Cladosporium (9.11%), Trichoderma (6.15%), Aspergillus (4.77%), and Fusarium (4.38%) as major components; whereas M. aurolineatus demonstrated a distinct configuration dominated by Aspergillus (18.80%), Thelebolus (10.26%), and Cladosporium (8.12%). The unique fungal genera accounted for relatively low proportions (4.84–9.77%) of the total endosymbiotic fungal communities across all four insect species (Figure 5C). Specifically, unique taxa represented 6.03% in H. cyanicollis, predominantly comprising Strelitziana (1.07%) and Xenoramularia (0.70%); 8.08% in G. bifasciata, mainly represented by Myxospora (1.36%), Hapsidospora (0.80%), Cladosporium (0.79%), and Zymoseptoria (0.71%); 9.77% in P. versicolora, primarily consisting of Bipolaris (0.75%), unidentified Sordariales (0.49%), and Tausonia (0.44%); and 4.84% in M. aurolineatus, dominated by Arthrobotrys (0.71%), Mrakia (0.68%), Zopfiella (0.59%), unclassified Mycosphaerellaceae (0.55%), and Meristemomyces (0.54%).

Figure 5.

Shared and unique genera of endosymbiotic fungi among the four insect species ((A): Shared genera; (B): Abundance of shared genus; (C): Unique genera).

3.3. Predicted Functional Profiles of the Endosymbionts

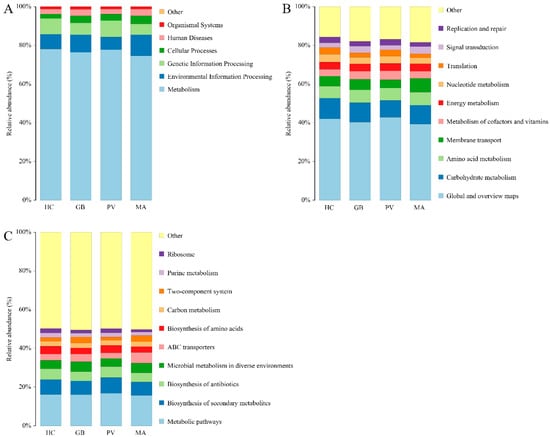

Functional prediction of endosymbiotic bacteria in the four insect species was performed using PICRUSt based on the KEGG database. At level 1, the functions were categorized into 6 major types: Metabolism, Genetic Information Processing, Environmental Information Processing, Cellular Processes, Organismal Systems, and Human Diseases (Figure 6A). Metabolism represented the most predominant functional category (relative abundance: 74.68–78.12%), with the lowest abundance observed in M. aurolineatus. This was followed by Environmental Information Processing (6.52–10.84%), which exhibited the highest abundance in M. aurolineatus. Genetic Information Processing constituted the third major category (5.61–8.50%), again showing the lowest abundance in M. aurolineatus. At Level 2, a total of 45 functional categories were predicted. Among the top 10 most abundant functional groups (Figure 6B), “Global and overview maps” consistently represented the highest relative abundance across all four insect species (39.42–42.87%), with M. aurolineatus exhibiting the lowest proportion within this category. This was followed by “Carbohydrate metabolism” (8.64–10.70%), which showed peak abundance in H. cyanicollis. The subsequent major categories, “Amino acid metabolism” (6.23–6.73%) and “Membrane transport” (4.28–7.13%), both demonstrated markedly elevated levels in M. aurolineatus compared to the other species. At Level 3, a total of 327 functional subcategories were predicted. Among the ten most abundant functional types (Figure 6C), “Metabolic pathways” represented the predominant category with a relative abundance of 15.73–16.77%. This was followed by “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (6.88–8.10%), “Biosynthesis of antibiotics” (4.79–5.66%), “Microbial metabolism in diverse environments” (4.20–5.06%), “ABC transporters” (2.94–5.46%), “Biosynthesis of amino acids” (3.09–4.02%), and “Carbon metabolism” (2.52–2.61%).

Figure 6.

Predicted functional profiles of the endosymbiotic bacterial community based on PICRUSt2 analysis ((A): At level 1; (B): At level 2; (C): At level 3).

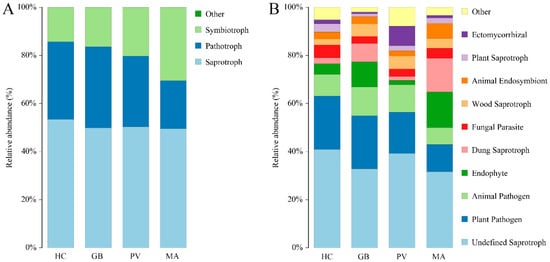

FUNGuild analysis of the endosymbiotic fungal communities identified three trophic modes encompassing 22 functional guilds. Saprotrophy represented the predominant nutritional mode (49.59–53.43%), followed by pathotrophy (19.96–33.74%) and symbiotrophy (14.31–30.45%). M. aurolineatus exhibited a distinct trophic profile characterized by the lowest pathotrophic abundance and the highest symbiotrophic representation among all examined species (Figure 7A). Among the top 10 most abundant functional guilds (Figure 7B), Undefined Saprotroph demonstrated the highest relative abundance (31.63–40.92%), followed by Plant Pathogen (11.32–22.20%) and Animal Pathogen (7.07–11.93%), with M. aurolineatus exhibiting the lowest proportions in all three categories. The subsequent major guilds, Dung Saprotroph (1.64–14.00%) and Endophyte (1.84–14.83%), both showed markedly elevated abundances in M. aurolineatus. The remaining functional groups included Fungal Parasite (2.89–5.30%), Wood Saprotroph (2.49–5.29%), Animal Endosymbiont (2.21–6.21%), Plant Pathotroph (1.17–3.41%), and Ectomycorrhizal (0.66–8.13%) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Predicted functional profiles of the endosymbiotic fungal community based on FUNGuild analysis ((A): trophic modes; (B): Top 10 most abundant functional guilds).

4. Discussion

The four species of coleopteran insects investigated in this study are taxonomically classified into two distinct families: H. cyanicollis, G. bifasciata, and P. versicolora belong to Chrysomelidae, while M. aurolineatus is categorized under Curculionidae.

In the endosymbiotic bacterial communities of the four insect species, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes served as the dominant phyla, with their combined relative abundances exceeding 95% in all species. Particularly, this proportion reached 99.81% in G. bifasciata. However, interspecific variations were observed: H. cyanicollis exhibited the highest abundance of Firmicutes, whereas the other three species were predominantly dominated by Proteobacteria. At the genus level, the bacterial composition displayed certain distinctive features corresponding to the taxonomic families of the insects. Among the three leaf beetle species, Enterobacter and Lactococcus consistently served as dominant genera, each maintaining relative abundances exceeding 16% (except for Lactococcus in P. versicolora). Furthermore, species-specific dominance patterns were observed: H. cyanicollis was characterized by substantial representation of Spiroplasma and Weissella; G. bifasciata exhibited predominance of Hafnia-Obesumbacterium; while P. versicolora demonstrated a distinct profile dominated by endosymbionts and Kluyvera. This pattern reveals distinct interspecific differentiation in bacterial community structure. However, M. aurolineatus exhibited a fundamentally distinct profile, dominated primarily by Klebsiella, Pantoea, and Cedecea—genera that were either absent or minimally represented in the three leaf beetle species. Although Enterobacter and Lactococcus were also detected in M. aurolineatus, their relative abundances were substantially lower than those observed in the leaf beetles. Consequently, the endosymbiotic bacterial communities exhibit marked compositional divergence between these two coleopteran families, a pattern further corroborated by the results of the Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). Among the shared bacterial genera across the four insect species, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Lactococcus, Weissella, and Kluyvera were identified as high-abundance taxa. Previous studies have indicated that these genera also represent dominant components of the gut microbiota in various other coleopteran insects [17,18,29,30,31,32,33]. Likewise, these shared bacterial genera exhibited significant differences in abundance between leaf beetles and weevils. The three chrysomelid species showed high abundances of Enterobacter, Lactococcus, and Serratia, but a low abundance of Klebsiella; conversely, the opposite pattern was observed in the weevil M. aurolineatus. Regarding the unique bacterial genera across the four insect species, the three leaf beetles exhibited exceptionally low proportions of unique taxa within their endosymbiotic communities, ranging from 0.10% to 2.74%. In striking contrast, M. aurolineatus possessed a substantially higher proportion of unique genera, accounting for 25.72% of its endosymbiotic bacteria. This notable disparity was primarily attributable to the exceptionally high abundance of Cedecea, which alone constituted 22.65% of the total bacterial community in this species. To date, the bacterial genus Cedecea remains unreported in coleopteran insects. Existing research, however, has documented its presence in the gut microbiota of certain dipteran and lepidopteran species, linking it to various functions including the degradation of substrates, antibiotic resistance, and the transmission pathways of endosymbionts [34,35,36]. Furthermore, Pantoea was identified as a dominant genus in M. aurolineatus but was either absent or present at minimal abundance in the three leaf beetle species. This genus has been documented to influence feeding behavior, insecticide resistance, and manipulation of plant defense responses in coleopteran insects [37,38,39]. The high relative abundance of both Cedecea and Pantoea may contribute to the ecological adaptability and frequent occurrence of M. aurolineatus in tea plantation ecosystems.

The endosymbiotic fungal assemblages in the four insect species were predominantly characterized by Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which collectively constituted more than 86% of the total fungal community in each species. Moreover, the relative abundance of Mucoromycota in M. aurolineatus was significantly lower than that in the three leaf beetle species. At the genus level, although some taxon-specific patterns were observed across the four insect species corresponding to their respective families, the degree of differentiation was less pronounced compared to the bacterial communities. The three leaf beetles exhibited substantially higher abundances of Mortierella and consistently contained Penicillium compared to M. aurolineatus. Additionally, each leaf beetle displayed distinct dominant fungal genera: H. cyanicollis was characterized by Fusarium and Cladosporium; G. bifasciata was predominantly associated with Aspergillus; and P. versicolora showed a fungal profile dominated by Cladosporium and Penicillium. However, M. aurolineatus exhibited a substantially higher abundance of Thelebolus and completely lacked Penicillium compared to the three leaf beetle species. Among the fungal genera shared by the four insects, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Cladosporium, Thelebolus, and Trichoderma were identified as the predominant high-abundance taxa. These genera have been previously documented in the gut microbiota of various coleopterans [37,38,39,40,41,42]. Among these shared genera, the three leaf beetles exhibited relatively high abundance of Mortierella and low abundance of Thelebolus, whereas M. aurolineatus displayed the opposite pattern. The three leaf beetles contained a higher proportion of unique fungal genera in their endosymbiotic communities than M. aurolineatus. These unique taxa consisted predominantly of plant pathogens.

A comparative analysis of endosymbiotic bacterial functions revealed that, while most KEGG categories from Level 1 to Level 3 differed in abundance between the three leaf beetles and M. aurolineatus, the disparities were generally limited in magnitude. A pronounced disparity was identified in the “Membrane transport” category at Level 2, which was significantly enriched in M. aurolineatus. The functional profiles of the endophytic fungi were marked by a relatively distinct, family-level divergence among the four insect species. Among the three trophic modes, M. aurolineatus exhibited significantly lower abundance of pathotrophs and substantially higher abundance of symbiotrophs compared to the three leaf beetle species. The three leaf beetles demonstrated significantly higher abundances of Plant Pathogen compared to M. aurolineatus. In contrast, M. aurolineatus exhibited markedly greater abundances of Endophyte, Dung Saprotroph, and Animal Endosymbiont relative to the leaf beetles.

This study provides a robust characterization of the insect microbiota during a critical phenological period (early summer). While the single time-point sampling design appropriately captures this specific context, it inherently prevents the analysis of seasonal succession. We therefore propose that future research prioritize longitudinal sampling to resolve the temporal dynamics and environmental drivers of these host-microbe associations.

5. Conclusions

Our investigation of endosymbionts in four coleopteran insects within a tea plantation elucidated clear distinctions in the taxonomic and functional composition of the microbiota between leaf beetles and weevils under a shared habitat. Chrysomelid beetles were characterized by dominant genera including Enterobacter, Lactococcus, Mortierella, and Penicillium, while curculionid weevils exhibited a distinct profile dominated by Klebsiella, Pantoea, Cedecea, and Thelebolus; Leaf beetles were characterized by dominant genera including Enterobacter, Lactococcus, Mortierella, and Penicillium. In contrast, M. aurolineatus exhibited a distinct profile dominated by Klebsiella, Pantoea, Cedecea, and Thelebolus. Leaf beetles exhibited predominant functional traits related to plant pathogenesis, whereas the curculionid weevil M. aurolineatus was characterized by enhanced membrane transport capabilities. These findings provide valuable insights for developing targeted management strategies against coleopteran pests in tea plantations. The observed microbiota divergence primarily reflects host identity effects under the present study conditions, though the relative contributions of host, habitat, and climate remain to be fully disentangled. Future cross-seasonal studies should clarify how these factors interact across temporal scales. A more systematic survey encompassing greater taxonomic diversity is needed to achieve a comprehensive understanding of microbial associations across this phylogenetically diverse family.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242592/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human participants or vertebrate animals. The insect specimens collected from the field are not endangered or protected species. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of NCBI at https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov or the accession number PRJNA1347653 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.L.; Zhong, W.Y.; Hu, H.Q.; Lin, C.J.; Jiang, M.X.; Li, Y.P.; Chen, M.Y. Prediction of the Potential Suitable Areas for Myllocerinus aurolineatus in China under Climate Change Scenarios. J. Environ. Entomol. 2024, 46, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.H.; Xia, S.M.; Han, B.Y. Investigation on Pest Fauna and Analysis of Dominant Species Succession Trends in Guizhou Tea Plantations. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2010, 37, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, W.; Wu, G.L.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, Z.M.; Li, J.M.; Lin, A.C. Insect Diversity and Pest Occurrence Patterns in Tea Plantations of Pu’an County. Hubei Plant Prot. 2023, 4, 44–48+51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Yang, D.; Zheng, J.L.; Yao, J.W.; Zhu, Z.G.; Huang, D.Y.; Cao, C.X. Research Progress on Biological Control of Major Pests in Chinese Tea Plantations. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2020, 59, 5–9+22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Liu, F.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, M. Leaf Beetle Symbiotic Bacteria Degrade Chlorogenic Acid of Poplar Induced by Egg Deposition to Enhance Larval Survival. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4212–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Lin, J.; Lin, C.Z. Occurrence and Damage Characteristics of Myllocerinus aurolineatus in Fu’an Tea Plantations and Green Control Strategies. Farmers Consult. 2021, 2, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.J.; Li, H.L.; Gao, X.F. Identification of Defense-Related Enzyme Genes in Tea Plants Induced by Damage from Myllocerinus aurolineatus. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2018, 32, 2313–2325. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R.P.; Anderson, C.M.H.; Thwaites, D.T.; Luetje, C.W.; Wilson, A.C.C. Co-option of a conserved host glutamine transporter facilitates aphid/Buchnera metabolic integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2308448120. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlin, L.; Gaget, K.; Lapetoule, G.; Quivet, Y.; Baa-Puyoulet, P.; Rahioui, I.; Ribeiro Lopes, M.; Da Silva, P.; Calevro, F.; Charles, H. Quantifying supply and demand in the pea aphid-Buchnera symbiosis reveals the metabolic Achilles’ heels of this interaction. Metab. Eng. 2025, 92, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, G.; Mikaelyan, A.; Fukui, C.; Matsuura, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Fujishima, M.; Brune, A. Fiber-associated spirochetes are major agents of hemicellulose degradation in the hindgut of wood-feeding higher termites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11996–E12004. [Google Scholar]

- Tokuda, G. Origin of symbiotic gut spirochetes as key players in the nutrition of termites. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 4092–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascar, J.; Middleton, H.; Dorus, S. Aedes aegypti microbiome composition covaries with the density of Wolbachia infection. Microbiome 2023, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubi, A.; Talebi, A.A.; Fathipour, Y.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Mehrabadi, M. Symbiont-mediated insect host defense against parasitism: Insights from the endosymbiont, Hamiltonella defensa and the insect host, Myzus persicae. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 4886–4893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jang, S.; Kikuchi, Y. Impact of the insect gut microbiota on ecology, evolution, and industry. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 41, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N.A. The gut microbiota of insects—Diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Community structure of gut bacteria of Dendroctonus armandi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) larvae during overwintering stage. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibet, S.; Mudalungu, C.M.; Kimani, N.M.; Makwatta, J.O.; Kabii, J.; Sevgan, S.; Kelemu, S.; Tanga, C.M. Unearthing Lactococcus lactis and Scheffersomyeces symbionts from edible wood-boring beetle larvae as a bio-resource for industrial applications. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Ndotono, E.W.; Tanga, C.M.; Kelemu, S.; Khamis, F.M. Mitogenomic profiling and gut microbial analysis of the newly identified polystyrene-consuming lesser mealworm in Kenya. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bin, X.; Xiang, X.; Wan, X. Diversity and Metabolic Potential of Gut Bacteria in Dorcus hopei (Coleoptera: Lucanidae): Influence of Fungus and Rotten Wood Diets. Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1692. [Google Scholar]

- Ayayee, P.A.; Sunny, B.; Montooth, K.L.; Rauter, C.M. The Larval and Adult Female Gut Microbiomes of Two Burying Beetles (Nicrophorus spp.) With Distinct Parental Care Traits. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 27, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Garcia, S.L.; Hambäck, P.A. Microbial transfer through fecal strings on eggs affects leaf beetle microbiome dynamics. mSystems 2025, 10, e0172324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.L.; Liu, F.J.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.D.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, D.F. Control Efficacy of Beauveria bassiana Granules Against Myllocerinus aurolineatus in Soil. Acta Tea Sinica. 2023, 64, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.F. The genus Gallerucida Motschulsky in Taiwan (Insecta, Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Galerucinae). Zookeys 2017, 723, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.X.; Luo, Z.X.; Li, Z.Q.; Bian, L.; Xiu, C.L.; Zhou, L.; Cai, X.M. Morphological characteristics and bionomics of the tea weevil, Myllocerinus aurolineatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Acta Entomologica Sinica 2025, 68, 174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Y.; Ge, S.Q.; Yang, X.K.; Li, W.Z.; Zhang, P.F. Records of Galerucinae from Guangxi, China (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Entomotaxonomia 2002, 2, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Braglia, C.; Cutajar, S.; Magagnoli, S.; Asciano, D.; Burgio, G.; Di Gioia, D.; Baffoni, L.; Alberoni, D. The Ground Beetle Poecilus (Carabidae) Gut Microbiome and Its Functionality. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Tyson, G.W.; Hugenholtz, P.; Beiko, R.G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3123–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Gao, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Du, C. Comparative Analyses of Gut Microbiomes in Hycleus cichorii (Coleoptera: Meloidae) Adults Reveal Their Distinct Microbes, Microbial Diversity and Composition Associated to Food. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.; Newton, J.A.; von Beeren, C.; O’Donnell, S.; Kronauer, D.J.C.; Russell, J.A.; Łukasik, P. Microbial symbionts are shared between ants and their associated beetles. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 3466–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A.M.; Garcia, A.M.; Khlystov, N.A.; Wu, W.M.; Criddle, C.S. Enhanced Bioavailability and Microbial Biodegradation of Polystyrene in an Enrichment Derived from the Gut Microbiome of Tenebrio molitor (Mealworm Larvae). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2027–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, M.; Lidon, P.; Carrascosa, A.; Muñoz, M.; Navarro, M.V.; Orts, J.M.; Pascual, J.A. Polyurethane foam degradation combining ozonization and mealworm biodegradation and its exploitation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 5332–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matyakubov, B.; Lee, T.J. Optimizing polystyrene degradation, microbial community and metabolite analysis of intestinal flora of yellow mealworms, Tenebrio molitor. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 403, 130895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, P.; Grizard, S.; Tran, F.H.; Lejon, D.; Bellemain, A.; Van Mavingui, P.; Roiz, D.; Simard, F.; Martin, E.; Abrouk, D.; et al. Bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and microbiota dynamics across developmental stages of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus exposed to urban pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 286, 117214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viafara-Campo, J.D.; Vivero-Gómez, R.J.; Fernando-Largo, D.; Manjarrés, L.M.; Moreno-Herrera, C.X.; Cadavid-Restrepo, G. Diversity of Gut Bacteria of Field-Collected Aedes aegypti Larvae and Females, Resistant to Temephos and Deltamethrin. Insects 2025, 16, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Ai, Q.; Xia, X. Potential Source and Transmission Pathway of Gut Bacteria in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella. Insects 2023, 14, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Sun, J.; Xu, L. Gut bacteria facilitate leaf beetles in adapting to dietary specialization by enhancing larval fitness. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielkopolan, B.; Szabelska-Beręsewicz, A.; Gawor, J.; Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A. Cereal leaf beetle-associated bacteria enhance the survival of their host upon insecticide treatments and respond differently to insecticides with different modes of action. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ju, X.; Yang, M.; Xue, R.; Li, Q.; Fu, K.; Guo, W.; Tong, L.; Song, Y.; Zeng, R.; et al. Colorado potato beetle exploits frass-associated bacteria to suppress defense responses in potato plants. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3778–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jia, Y.; Li, Y.; Geng, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, N.; Zeng, J.; Su, X.; et al. Potential Functions and Transmission Dynamics of Fungi Associated with Anoplophora glabripennis Across Different Life Stages, Between Sexes, and Between Habitats. Insects 2025, 16, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afe, A.E.; Lawal, O.T.; Bamidele, O.S.; Badshah, F.; Oyelere, B.R.; Efomah, A.N.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Fatima, S.; Alamri, A.; El-Tayeb, M.A.; et al. Production, purification, and characterization of a thermally stable, Acidophilic Cellulase from Aspergillus awamori AFE1 isolated from Longhorn beetle (Cerambycidae latreille). Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Gao, J.; Hao, C.; Dai, L.; Chen, H. Biodiversity and Activity of Gut Fungal Communities across the Life History of Trypophloeus klimeschi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).