Shifts in Bacterial Community Structure and Humus Formation Under the Effect of Applying Compost from the Cooling Stage as a Natural Additive

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Composting Design

2.3. Measurement of Physical and Chemical Properties

2.4. Determination of Humus Prerequisite Substances and Humic Substances

2.5. The Composition of the Microbial Community

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Variation in Temperature, pH, EC, C/N Ratio, and Germination Index of Composting

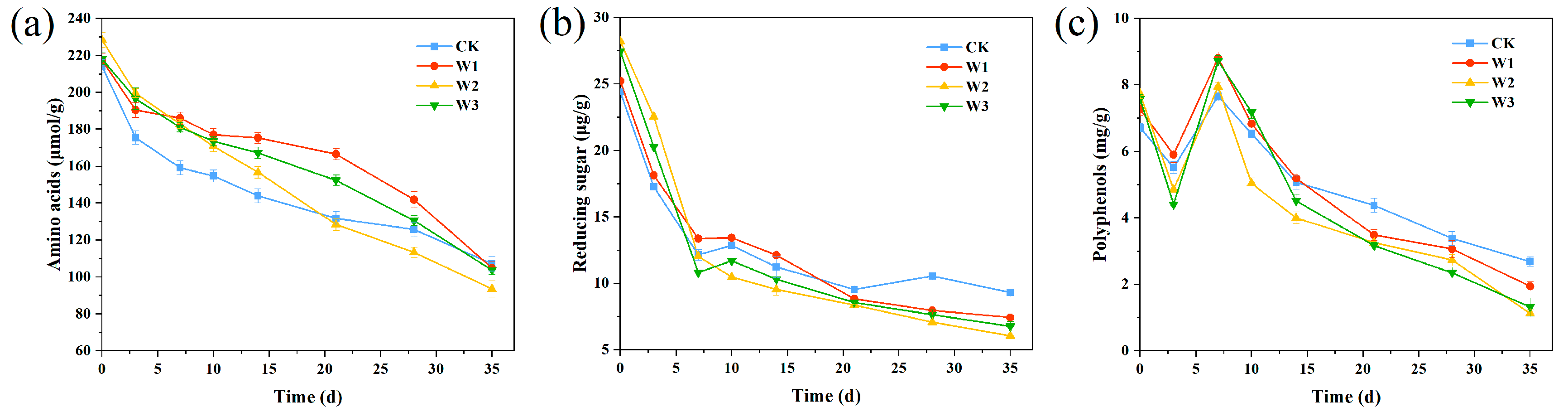

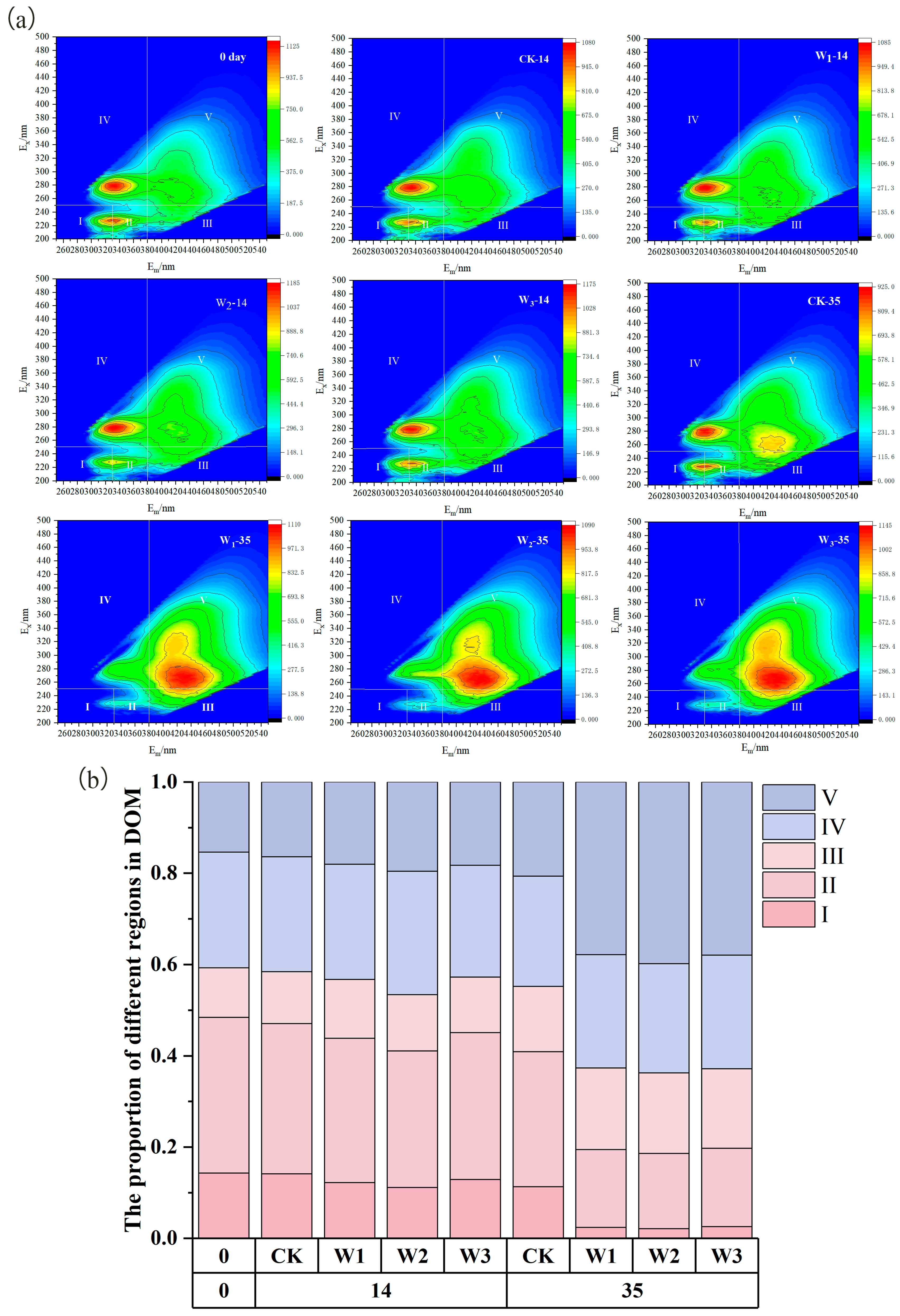

3.2. Humification Precursor Substances and EEM Analysis of the Humification Process

3.3. Transformation of Humus Composition During Composting

3.4. The Microbial Community Structure Changes

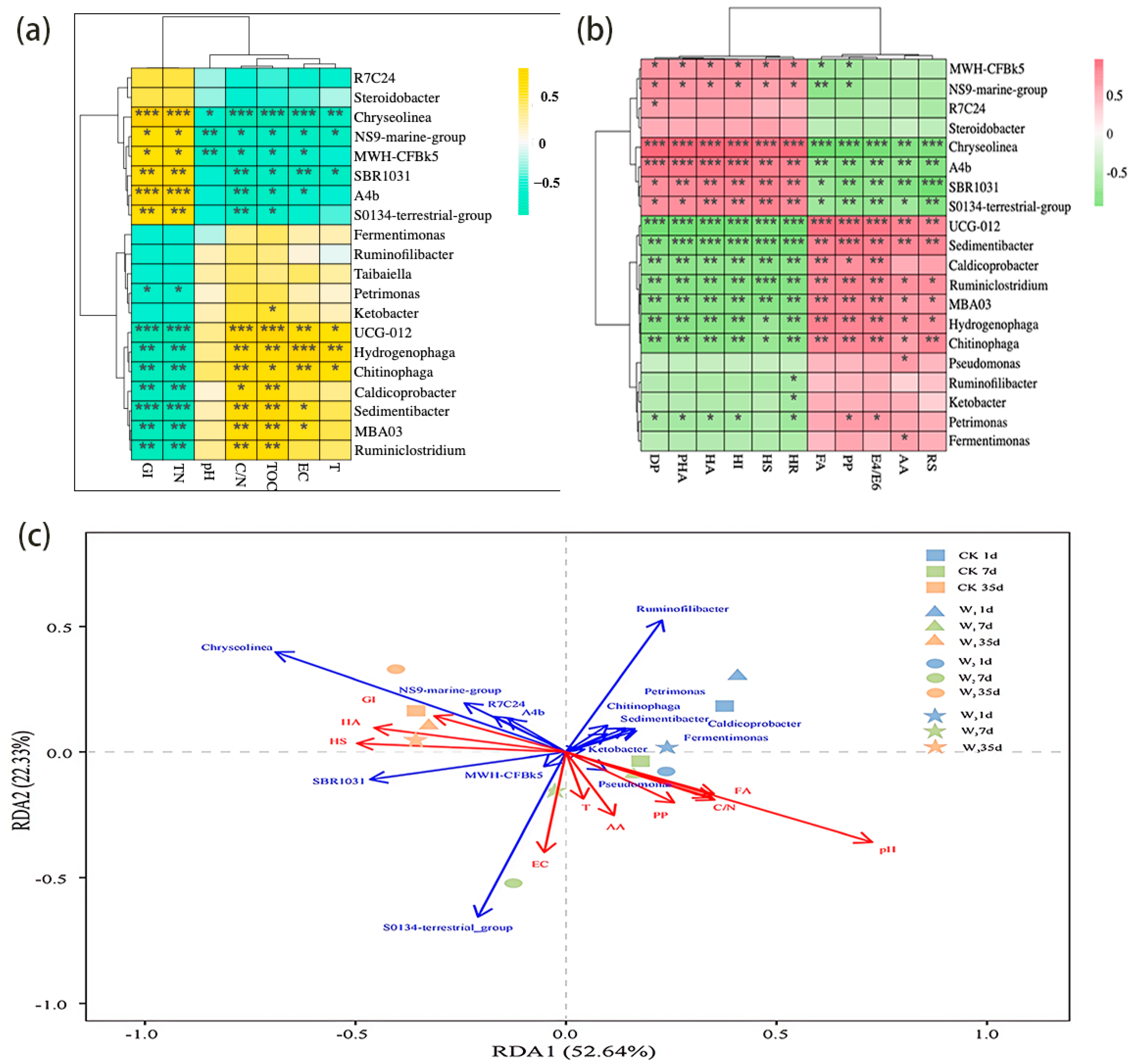

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between Physicochemical Properties, Humification Coefficient and Bacterial Community

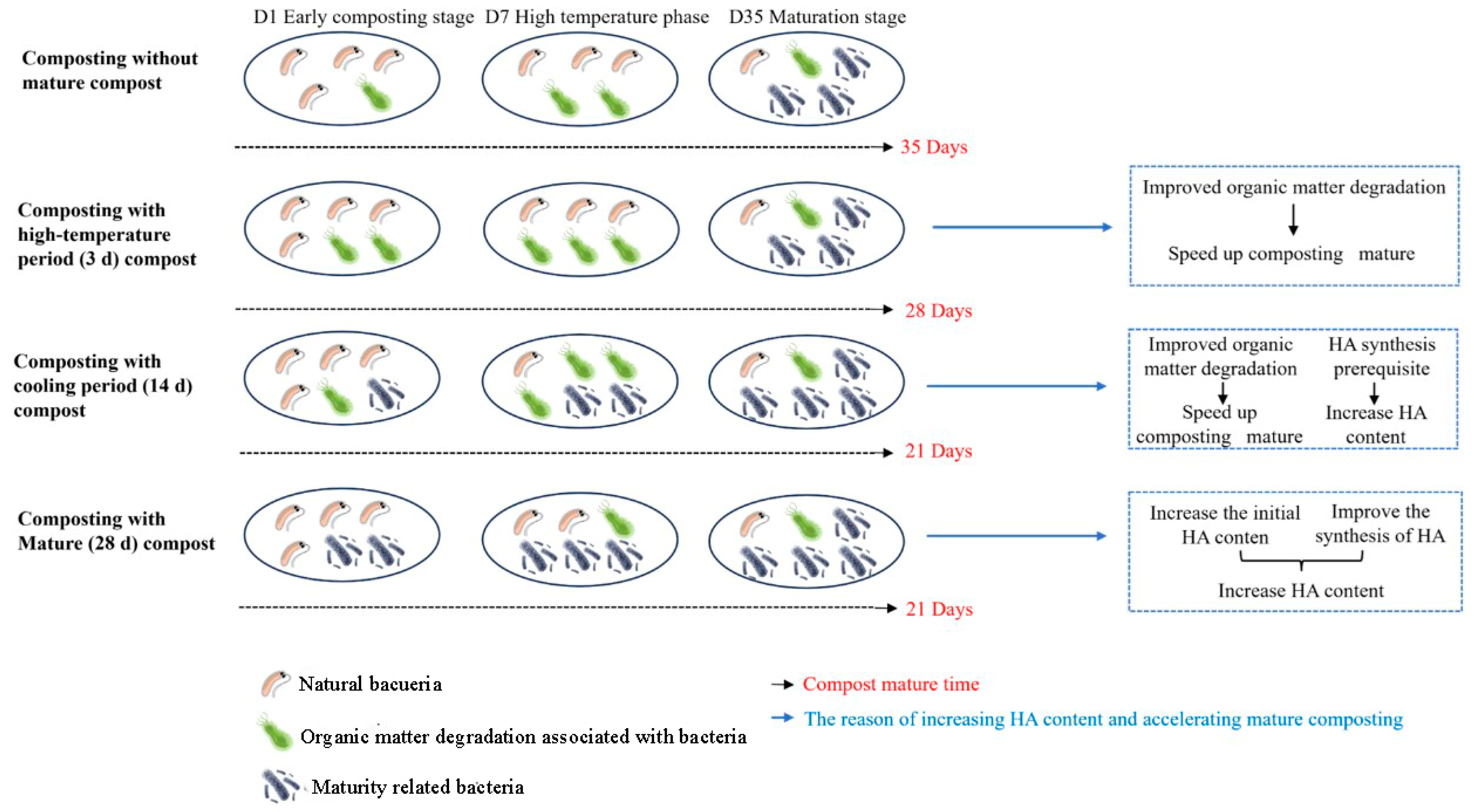

3.6. Potential Mechanism by Which Adding Different Composting Samples Improves Composting Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, X.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Yi, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Mazarji, M.; Syed, A.; et al. Exploring carbon conversion and balance with magnetite-amended during pig manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 388, 129707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zou, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, J. Biochar improves compost humification, maturity and mitigates nitrogen loss during the vermicomposting of cattle manure-maize straw. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ma, N.L.; Fei, S.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. Enhanced humification via lignocellulosic pretreatment in remediation of agricultural solid waste. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.K.; Alagumalai, A.; Balaji, D.; Song, H. Bio-based agricultural products: A sustainable alternative to agrochemicals for promoting a circular economy. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 746–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Han, X.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Feng, H.; Wu, Z.; Liu, C.; Yan, J.; Zou, W. Evaluation of the soil aggregate stability under long term manure and chemical fertilizer applications: Insights from organic carbon and humic acid structure in aggregates. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 376, 109217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; DeMarco, J. Composted biosolids amendments for enhanced soil organic carbon and water storage in perennial pastures in Colorado. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 347, 108401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddech, N.; Theerakulpisut, P.; Ma, Y.N.; Sarin, P. Bioorganic fertilizers from agricultural waste enhance rice growth under saline soil conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sloot, M.; Limpens, J.; De Deyn, G.B.; Kleijn, D. The multifunctionality of cuttings from semi-natural habitats as organic amendments in arable farming. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 386, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lorca, M.; Jaime-Rodríguez, C.; González-Coria, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Pérez, M.; Valluerdú-Queralt, A.; Hernández, R.; Chantry, O.; Romanyà, J. Increasing soil organic matter and short-term nitrogen availability by combining ramial chipped wood with a crop rotation starting with sweet potato. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 392, 109740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, W.; Xie, L.; Zhang, G.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Song, C.; Chang, M. Malonic acid shapes bacterial community dynamics in compost to promote carbon sequestration and humic substance synthesis. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Q.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z. Effect of thermo-tolerant actinomycetes inoculation on cellulose degradation and the formation of humic substances during composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, H.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zou, B. Improving the humification by additives during composting: A review. Waste Manag. 2023, 158, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.-X.; Liu, H.-T.; Wu, S.-B. Humic substances developed during organic waste composting: Formation mechanisms, structural properties, and agronomic functions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Ma, R.; Yuan, J.; Li, G. Key factors affecting seed germination in phytotoxicity tests during sheep manure composting with carbon additives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, H.; Huang, H. Reduced pH is the primary factor promoting humic acid formation during hyperthermophilic pretreatment composting. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hao, Y.; Lin, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, K.; Li, J. The bioaugmentation effect of microbial inoculants on humic acid formation during co-composting of bagasse and cow manure. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, J.; Song, C.; Wei, Z. The biotic effects of lignite on humic acid components conversion during chicken manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 398, 130503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Improving food waste composting efficiency with mature compost addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 349, 126830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Zou, X.; Cheng, T.; Li, J. Aerobic co-composting of mature compost with cattle manure: Organic matter conversion and microbial community characterization. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, Y.; Yan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tian, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z. Insight into the microbial mechanisms for the improvement of spent mushroom substrate composting efficiency driven by phosphate-solubilizing Bacillus subtilis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zhu, C.; Xue, S.; Li, B.; Ye, J.; Geng, B.; Li, L.; Fahad Sardar, M.; Li, N.; Feng, S.; et al. Comparative effects of different antibiotics on antibiotic resistance during swine manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X. Improvement of two-stage composting of green waste by addition of eggshell waste and rice husks. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 117561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, Q.; Li, G.; Ma, C.; Li, Q.; Meng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q. Impacts of red mud on lignin depolymerization and humic substance formation mediated by laccase-producing bacterial community during composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 410, 124557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhdar, A.; Falleh, H.; Ouni, Y.; Oueslati, S.; Debez, A.; Ksouri, R.; Abdelly, C. Municipal solid waste compost application improves productivity, polyphenol content, and antioxidant capacity of Mesembryanthemum edule. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 191, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tian, L.; Li, Y.; Zhong, C.; Tian, C. Effects of exogenous cellulose-degrading bacteria on humus formation and bacterial community stability during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, G.; Zhang, W.; Hou, J.; Daniel Tang, K.H.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Abdelrahman, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. Ferrous salts accelerate humification and reduced carbon emissions during the co-composting of hoggery slurry and wheat husks: New insights into their biotic and abiotic functions and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, D.; Li, B.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y. Enhanced turnover of phenolic precursors by Gloeophyllum trabeum pretreatment promotes humic substance formation during co-composting of pig manure and wheat straw. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Shen, Y.; Ding, J.; Meng, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. New insight into the impact of moisture content and pH on dissolved organic matter and microbial dynamics during cattle manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Deng, F.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Li, D. Bioaugmentation on humification during co-composting of corn straw and biogas slurry. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 374, 128756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, D.; Pan, Y.; Su, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cernava, T.; Wang, Q. Di-n-butyl phthalate negatively affects humic acid conversion and microbial enzymatic dynamics during composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Ding, S.; Wen, X.; Yu, M.; Zou, X.; Wu, D. Investigating inhibiting factors affecting seed germination index in kitchen waste compost products: Soluble carbon, nitrogen, and salt insights. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 130995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; He, X.S.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Tao, Y.Q.; Wang, C.; Qiu, Z.P. Influence of moisture content on chicken manure stabilization during microbial agent-enhanced composting. Chemosphere 2021, 264 Pt 2, 128549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, D.; Wei, D.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Xie, X.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Z. Improved lignocellulose-degrading performance during straw composting from diverse sources with actinomycetes inoculation by regulating the key enzyme activities. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 271, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, R.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wen, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, Q. Metagenomics analysis revealed the coupling of lignin degradation with humus formation mediated via shell powder during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Deng, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Li, D. Bioaugmentation mechanism on humic acid formation during composting of food waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, C.; da Silva, A.J.R.; Lopes, M.L.M.; Fialho, E.; Valente-Mesquita, V.L. Polyphenol oxidase activity, phenolic acid composition and browning in cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale L.) after processing. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Bao, R.; Huang, W.; Li, Q. Facilitating the enzymatic hydrolysis of polysaccharides by carbohydrate active enzymes and enhanced humification process with microbial consortium revealed by metagenomics analysis during cow manure-straw composting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Wan, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Yao, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, Y.; Xie, J.; et al. Fulvic acid-like substance and its characteristics, an innovative waste recycling material from pulp black liquor. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, W.; Gao, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, F.; et al. Enhancing humification in high-temperature composting: Insights from endogenous and exogenous heating strategies. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 419, 132099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Ji, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Yao, X.; Hu, B. Self-circulating pulse alternating ventilation composting technology: Biotic and abiotic effects of mature compost on humification during food waste composting. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, X.; Yu, Y.; Teng, Z.; Chen, J. Enhanced lignocellulose degradation and composts fertility of cattle manure and wheat straw composting by Bacillus inoculation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y. Increased enzyme activities and fungal degraders by Gloeophyllum trabeum inoculation improve lignocellulose degradation efficiency during manure-straw composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Kang, J.; Sun, R.; Liu, J.; Ge, J.; Ping, W. Ecological succession of abundant and rare subcommunities during aerobic composting in the presence of residual amoxicillin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, X.; Khan, R.A.A.; Chen, S.; Jiao, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Jiang, L.; Song, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Deciphering the role of rhizosphere microbiota in modulating disease resistance in cabbage varieties. Microbiome 2024, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Zhu, D.; Zou, Y. Combined virome analysis and metagenomic sequencing to reveal the viral communities and risk of virus-associated antibiotic resistance genes during composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Keiblinger, K.M.; Huang, Y.; Bhople, P.; Shi, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, F.; Liu, D. Virome and metagenomic sequencing reveal the impact of microbial inoculants on suppressions of antibiotic resistome and viruses during co-composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, H.; Lv, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, R.; Zhai, B.; Wang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L. Improvement of biochar and bacterial powder addition on gaseous emission and bacterial community in pig manure compost. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 258, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Singh, S.; Yadav, A.N.; Nain, L.; Saxena, A.K. Phylogenetic Diversity and Characterization of Novel and Efficient Cellulase Producing Bacterial Isolates from Various Extreme Environments. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2014, 77, 1474–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapébie, P.; Lombard, V.; Drula, E.; Terrapon, N.; Henrissat, B. Bacteroidetes use thousands of enzyme combinations to break down glycans. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yu, K.; Ahmed, I.; Gin, K.; Xi, B.; Wei, Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, B. Key factors driving the fate of antibiotic resistance genes and controlling strategies during aerobic composting of animal manure: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Sun, Z.Y.; Wang, S.T.; Yuan, H.W.; An, M.Z.; Xia, Z.Y.; Tang, Y.Q.; Shen, C.H.; Kida, K. Bacterial Community Structure and Metabolic Function Succession During the Composting of Distilled Grain Waste. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 1479–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Awasthi, M.K.; Syed, A.; Bahkali, A.H. Engineered biochar combined clay for microplastic biodegradation during pig manure composting. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, W.; Wei, Z.; Song, C. Investigating the effect of Fenton-like pretreatment-clay mineral addition on humic substance during straw composting. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 154199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sardar, M.F.; Zhang, X.; Ye, J.; Tian, Y.; Song, T.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, H. Electrokinetic technology enhanced the control of antibiotic resistance and the quality of swine manure composting. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Wu, H.; Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Lyu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, T.; Li, R.; Yao, Y. Soil decreases N2O emission and increases TN content during combined composting of wheat straw and cow manure by inhibiting denitrification. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | pH | MC (%) | TOC (%) | TN (%) | C/N | EC (mS/cm) | AA (μmol/g) | RS (μg/g) | PP (mg/g) | HA (g/kg) | FA (g/kg) | HS (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow manure | 8.51 ± 0.32 | 78.13 ± 2.3 | 32.09 ± 0.64 | 1.54 ± 0.32 | 21.39 ± 0.48 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | ||||||

| Corn straw | — | 9.31 ± 1.5 | 46.9 ± 0.52 | 0.58 ± 0.28 | 80.86 ± 0.33 | 1.44 ± 0.03 | ||||||

| High-temperature additive | 8.32 ± 0.04 | 63.63 ± 0.38 | 40.77 ± 0.43 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 36.72 ± 0.53 | 1.45 ± 0.03 | 175.46 ± 3.71 | 17.27 ± 0.03 | 5.51 ± 0.18 | 39.28 ± 1.13 | 31.74 ± 1.13 | 71.02 ± 0.56 |

| Cool additive | 8.66 ± 0.03 | 51.7 ± 0.64 | 38.05 ± 0.82 | 1.47 ± 0.01 | 25.88 ± 0.48 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 143.89 ± 3.84 | 11.23 ± 0.08 | 5.07 ± 0.21 | 52.26 ± 1.13 | 30.26 ± 1.13 | 82.52 ± 0.64 |

| Mature additive | 8.35 ± 0.02 | 47.19 ± 0.66 | 36.84 ± 0.75 | 1.72 ± 0.03 | 21.41 ± 0.56 | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 125.64 ± 3.99 | 10.55 ± 0.03 | 3.38 ± 0.20 | 60.37 ± 1.19 | 26.43 ± 1.19 | 86.80 ± 0.24 |

| CK | 7.79 ± 0.04 | 65.65 ± 0.60 | 43.18 ± 0.39 | 1.45 ± 0.08 | 29.69 ± 0.67 | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 214.15 ± 3.52 | 24.41 ± 0.15 | 6.71 ± 0.12 | 29.35 ± 1.04 | 35.49 ± 1.18 | 64.84 ± 0.14 |

| W1 | 8.05 ± 0.05 | 66.05 ± 0.58 | 45.11 ± 0.54 | 1.57 ± 0.06 | 28.78 ± 0.49 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 217.47 ± 3.70 | 25.23 ± 0.11 | 7.27 ± 0.18 | 29.57 ± 1.05 | 35.78 ± 1.26 | 65.35 ± 0.04 |

| W2 | 7.87 ± 0.02 | 66.01 ± 0.53 | 46.91 ± 0.28 | 1.64 ± 0.086 | 28.57 ± 0.52 | 1.31 ± 0.03 | 228.43 ± 4.07 | 28.22 ± 0.38 | 7.73 ± 0.14 | 35.13 ± 1.12 | 38.72 ± 1.12 | 73.85 ± 0.29 |

| W3 | 7.86 ± 0.05 | 65.43 ± 0.62 | 45.30 ± 0.49 | 1.57 ± 0.06 | 28.90 ± 0.53 | 1.31 ± 0.02 | 218.08 ± 3.20 | 27.45 ± 0.04 | 7.58 ± 0.13 | 37.26 ± 1.10 | 38.59 ± 1.10 | 75.85 ± 0.05 |

| Treatment | pH | C/N | EC (mS/cm) | AA (μmol/g) | RS (μg/g) | PP (mg/g) | HA (g/kg) | FA (g/kg) | HS (g/kg) | DP | E4/E6 | GI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 8.15 ± 0.02 c | 19.90 ± 0.41 d | 1.20 ± 0.03 b | 107.10 ± 3.98 b | 9.31 ± 0.22 d | 2.68 ± 0.14 c | 61.07 ± 0.88 c | 25.13 ± 1.14 b | 86.20 ± 0.88 b | 2.43 ± 0.05 d | 3.86 ± 0.16 c | 92.11 ± 3.26 c |

| W1 | 8.22 ± 0.02 b | 18.76 ± 0.53 c | 1.15 ± 0.03 ab | 104.83 ± 3.34 b | 7.43 ± 0.05 c | 1.94 ± 0.14 b | 67.02 ± 1.10 b | 24.24 ± 1.10 b | 91.25 ± 0.63 a | 2.77 ± 0.04 c | 2.99 ± 0.29 b | 97.98 ± 5.40 bc |

| W2 | 8.47 ± 0.05 a | 15.95 ± 0.47 a | 1.11 ± 0.03 a | 93.47 ± 4.39 a | 6.05 ± 0.07 a | 1.12 ± 0.11 a | 71.49 ± 1.03 a | 19.63 ± 1.03 a | 91.12 ± 0.40 a | 3.64 ± 0.05 a | 2.55 ± 0.12 a | 107.01 ± 3.04 a |

| W3 | 8.36 ± 0.06 a | 17.65 ± 0.28 b | 1.12 ± 0.03 a | 103.67 ± 2.39 b | 6.75 ± 0.36 b | 1.31 ± 0.27 a | 69.35 ± 1.06 ab | 21.64 ± 1.06 a | 90.98 ± 0.34 a | 3.20 ± 0.05 b | 2.69 ± 0.14 ab | 101.58 ± 3.75 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, C.; Ma, N.L. Shifts in Bacterial Community Structure and Humus Formation Under the Effect of Applying Compost from the Cooling Stage as a Natural Additive. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242591

Ma J, Wang Y, Zhang X, Chen G, Wang J, Sun Y, Sun C, Ma NL. Shifts in Bacterial Community Structure and Humus Formation Under the Effect of Applying Compost from the Cooling Stage as a Natural Additive. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242591

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Jianxun, Yufan Wang, Xinyu Zhang, Guang Chen, Jihong Wang, Yang Sun, Chunyu Sun, and Nyuk Ling Ma. 2025. "Shifts in Bacterial Community Structure and Humus Formation Under the Effect of Applying Compost from the Cooling Stage as a Natural Additive" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242591

APA StyleMa, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, G., Wang, J., Sun, Y., Sun, C., & Ma, N. L. (2025). Shifts in Bacterial Community Structure and Humus Formation Under the Effect of Applying Compost from the Cooling Stage as a Natural Additive. Agriculture, 15(24), 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242591