1. Introduction

At present, energy transition represents one of the key directions of development policies, both globally and in the European context [

1,

2,

3]. In view of climate challenges, growing energy demand and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), the importance of investments in renewable energy sources (RES) and other actions supporting the development of low-carbon economy is increasingly being recognized [

4,

5]. It is envisaged as a development model limiting GHG emissions (particularly CO

2) thanks to the decarbonization of the energy generation system, improved energy efficiency, and substitution of fossil fuels with RES in key sectors such as construction and transportation [

6,

7]. Such a paradigm promotes lower consumption of energy and resources, as well as the modernization of manufacturing processes [

8]. In respective EU documents the development of RES and enhanced energy efficiency are treated not only as an instrument promoting environmental protection, but also as an impulse towards local and regional development [

9,

10].

A major group of entities implementing measures aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy comprises local government units, responsible for planning and execution of investments adapted to local conditions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The commune, as the basic local government unit in Poland, is the creator of local development within the three pillars of sustainability—social, economic, and environmental. The importance of local government units as agents in climate policy has been confirmed by the growing body of research analyzing the scope and local conditions for investments aimed at climate neutrality [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Local governments finance these actions using both their own funds and—to a considerable degree— EU funds (including, e.g., cohesion policy and territorial cooperation programs). As a consequence, within the discussed scope the assessment of their investment activity constitutes a useful, empirical measure for the progress attained by these regions in the implementation of low-carbon economy measures.

Studies conducted to date concerning investments made by local government units in RES and the low-carbon economy in Poland have focused primarily on the national perspective, divided into administration types of communes, or on the regional level. However, there is a shortage of in-depth studies covering the unique conditions found in communes located in the border regions of Poland, particularly the voivodships (Polish: województwa, provinces) comprising the Eastern Macroregion (i.e., Podlaskie, Lubelskie, and Podkarpackie). This area constitutes a continuous EU border zone (the borders with Lithuania and Slovakia) and the external border of the EU (Belarus and Ukraine), which significantly modifies their development conditions: market accessibility, costs of infrastructure, and directions of public cooperation (e.g., Interreg) concerning the environment, energy, and climate. According to a report by Statistics Poland (Polish: Główny Urząd Statystyczny, GUS) [

23], these regions belong to the peripheral areas with the lowest level of socio-economic development in the country (quantified based on GDP per capita), a relatively important role of agriculture (the highest share of population employed in agriculture), and lesser accessibility, as well as limited technological infrastructure. An additional challenge is connected to their depopulation (the highest negative net migration) and population aging, which hinder implementation of advanced technological solutions and reduce the endogenous potential of local government units [

23]. On the other hand, these areas are equipped with considerable natural (environmental) capital (protected areas, high forest cover, and water resources) and they utilize cross-border cooperation mechanisms, providing them with potential alternative pathways to economic growth, including investments in RES and the low-carbon economy. Filling the above-mentioned research gap is of significant importance, since in the peripheral regions, energy transition may constitute both an additional burden and a chance to strengthen local economies.

In the Eastern Macroregion, rural areas cover the vast majority of the territory and have a markedly higher share of rural communes in their structure of local government units compared to the national average. Thus, the percentage of the population inhabiting rural areas is one of the highest in Poland, accounting for approximately 53% compared to slightly over 40% on the national scale [

23]. According to the Delimitation of Rural Areas (DRA) [

24], a considerable part of these communes belongs to non-agglomeration zones of low population density, which additionally enhances their peripheral character. For this reason, this analysis focuses on rural and urban–rural communes, as those areas experience accumulated diverse developmental challenges, e.g., adverse demographic trends (depopulation and population aging), scattered settlements and low population density, higher unit costs of infrastructure, and limited fiscal potential, which makes it more difficult for them to raise capital for investments. Additionally, energy poverty is more prevalent (related to obsolete housing, individual high-emission heating sources, etc.) and grid barriers (limited grid capacity and grid accessibility). Analysis focused on rural and urban–rural communes provides a more reliable presentation of the unique character of the peripheral regions of Eastern Poland, reducing the bias resulting from overgeneralizations made based on data concerning cities. It also makes it possible to assess to what degree investments in RES and the low-carbon economy may mitigate the indicated structural deficits.

The process of energy transition has a distinct territorial dimension, as its course is closely interlinked with the spatial structure of development and the relationships between settlement units. The literature emphasizes that the functional linkages between communes and urban centers determine their developmental and investment potential [

25,

26]. According to the classical theories of spatial development—the growth pole theory [

27], the core–periphery model [

28], and the theory of cumulative causation and spread–backwash effects [

29]—economic impulses generated in urban areas tend to diffuse into adjacent territories, reinforcing their investment activity. From this perspective, the analysis of relationships between rural communes and urban centers becomes particularly relevant in peripheral regions such as the Eastern Macroregion of Poland. Although these areas are characterized by limited economic and infrastructural potential, they display substantial internal diversity in terms of functional connections, which may influence their capacity to implement investments in the low-carbon economy. Contemporary studies indicate that communes maintaining stronger linkages with urban centers are more likely to participate in modernization processes related to sustainable development and energy transition [

30,

31,

32]. Therefore, the spatial position of communes with respect to large cities and their integration within functional networks can be regarded as an important factor differentiating investment activity in the field of the low-carbon economy in Eastern Poland’s peripheral regions.

The primary aim of this study was to assess how location in a border region and relation to FUA diversify investment activity and level of investment co-financed by EU funds aimed at developing the low-carbon economy in rural and urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion. The analysis was conducted in two complementary dimensions: (i) a comparative nationwide assessment covering all macroregions of Poland within the two most recent, completed EU financial frameworks, i.e., the years 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 and (ii) an in-depth analysis of the Eastern Macroregion, with particular attention to rural and urban–rural communes, their affiliation with Functional Urban Areas (FUAs), and typology defined by the Delimitation of Rural Areas (DRA). The investigations aimed to provide an answer to the research hypothesis, assuming that “in the Eastern Macroregion the spatial conditions, i.e., the border zone and the location in relation to Functional Urban Areas (within an FUA vs. outside an FUA), significantly diversify the investment activity of rural and urban–rural communes in projects co-financed by EU funds and aimed at the low-carbon economy”.

In order to address the research problem in a coherent and comprehensive manner, the article is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes the theoretical background by reviewing the literature on energy transition in peripheral, rural, and border regions, thereby embedding the analysis within the broader framework of spatial development and local climate policy.

Section 3 describes the data sources, spatial classifications, and research methods applied, ensuring the transparency and reproducibility of the empirical approach.

Section 4 presents and interprets the empirical results, examining the spatial differentiation of investment activity in low-carbon projects, both in comparison with other macroregions of Poland and within the Eastern Macroregion in relation to Functional Urban Areas. Finally,

Section 5 synthesizes the findings, verifies the research hypothesis and discusses the key implications for regional and local development policy in peripheral border areas.

2. Review of the Literature: Local Government Units Facing Challenges of Energy Transition—The Context of Rural and Peripheral Communes

For decades the development of peripheral regions, including border zones, has been investigated by researchers specializing in spatial economics, socio-economic geography, and regional policy. Classical concepts of core vs. periphery and New Economic Geography (NEG) underline that the stability of differences in development result from cumulative mechanisms, such as feedback from agglomerations, costs of transport, and economies of scale [

29,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. In this approach the urban core attracts investments, residents, and innovations, while peripheries, lacking similar stimuli, suffer from increasing dependence and structural deficits.

In view of the classical concepts of unbalanced growth [

29,

33] and core–periphery theory, rural and agricultural areas are perceived as spaces with limited access to developmental stimuli, dominated by urban cores as centers for the diffusion of innovation and capital flow. In turn, Myrdal [

29] indicated the action of spread effects and backwash effects, which reinforce the advantage of urban centers at the expense of peripheries. Hirschman [

33] supplemented this approach with the concept of unbalanced growth, in which economic processes develop selectively, concentrating around the so-called growth poles.

New Economic Geography [

34,

36] has been developing these assumptions, indicating that stability of peripherality results from cumulative mechanisms, such as economies of scale, costs of transport, and effects of agglomeration. The NEG models show that in the case of the absence of compensation factors, such as transportation infrastructure, access to external markets or institutional support, peripheries develop at a much slower pace [

39]. In the context of rural areas, this means that structural inequalities in access to investments, innovations, and capital are strengthened, resulting in lesser potential to participate in energy transition processes.

The literature on the subject also underlines that peripherality is not solely a geographical category, rather being relational in character—it includes deficits in infrastructure, limitations in terms of social and human capital, demographic problems and absence of institutional development [

40]. Such understood peripherality is structural and functional in character, which means that peripheral areas remain dependent on the urban cores of development, not only spatially, but also economically and institutionally.

Border zones, being both spatial and political peripheries, experience these barriers particularly often. Medeiros [

41] pointed to the fact that the state border in Europe may act both as an isolating barrier and as a factor opening new opportunities thanks to the mechanisms of cross-border cooperation. In view of regional development, the key role is played by market accessibility, which determines the movement of goods, people, and knowledge. Its low level is considered to be one of the primary causes for inferior economic outcomes of border regions [

36,

42].

In contemporary research, peripherality is increasingly interpreted—not only in geographical but also in functional terms—as a limited degree of integration of individual territorial units with the main centers of development [

38,

40]. Within this framework, the location of communes in relation to cities and the intensity of their interactions within Functional Urban Areas (FUA) play a crucial role. The FUA concept, developed by the OECD and the European Commission, assumes that the urban core and its surrounding communes form an integrated socio-economic system based on the flows of population, labor, goods, and services [

24,

25,

43]. This functional proximity influences the accessibility of infrastructure, as well as financial and institutional resources, which in turn affects the capacity of local government units to implement investment projects [

44,

45].

Classical theories of spatial development—growth poles [

27], development centers [

33], and the core–periphery model [

28,

29]—emphasize that economic and innovative impulses generated in cities may diffuse to their surroundings, provided that efficient channels of functional linkages exist [

46,

47]. At the same time, these theories point out that in the absence of such connections, peripheral areas may experience resource drain effects and deepening dependence on central regions.

In the case of Eastern Poland, characterized by a dispersed settlement network and limited infrastructural accessibility, it can be assumed that the location in relation to major urban centers significantly affects the variation in investment potential among communes. Those located closer to regional capitals may exhibit greater capacity to undertake investments in the low-carbon economy, whereas more remote units may face institutional and infrastructural constraints. In this context, the functional location of local government units can be regarded as a key dimension of peripherality—one that both reflects spatial differentiation in developmental potential and shapes the diversity of investment activity related to the low-carbon economy in the peripheral regions of Eastern Poland.

As a consequence, peripherality in present-day terms is perceived not only as a static characteristic of space, but as a result of interactions between geographical, institutional, and functional factors. It was these conditions, i.e., limited accessibility, poor economic links, and lower institutional potential, that constituted a starting point for the analysis of energy transition in the peripheral and border communes, which suffer from developmental deficits, while at the same time searching for new activization pathways based on the low-carbon economy.

Energy transition is becoming one of the most important present-day challenges for the development of peripheral areas. The literature sources on the subject underline that this process is not solely technological in character, but rather constitutes a profound structural change in the functioning of local economies and spatial systems [

48]. The low-carbon economy, based on energy efficiency and renewable energy sources, may serve the function of a new developmental factor, enhancing local resources, institutional capacities, and energy independence [

16,

49].

In rural and border regions investments in the low-carbon economy, including renewable energy sources, contribute to the creation of new jobs, improve the quality of technological infrastructure, and enhance socio-economic resilience [

50,

51]. At the same time, as indicated by Golubchikov and O’Sullivan [

48], spatial diversification of transition processes leads to the formation of so-called energy peripheries, in which the pace and scale of changes are limited by institutional, infrastructural, and financial factors.

In the most recent literature published after 2020, energy transition in peripheral and rural regions is increasingly analyzed through the lens of spatial justice, institutional capacity, and socio-technical change. Contemporary studies demonstrate that peripheral regions often experience delayed and uneven energy transition due to weaker administrative capacity, limited access to financing, and underdeveloped grid infrastructure [

48,

52,

53]. In this context, the concept of “energy peripheries” highlights how spatially remote areas may remain structurally disadvantaged in low-carbon transformation processes despite possessing significant renewable energy potential [

48]. At the same time, recent empirical research confirms that renewable energy investments in rural and border regions may significantly strengthen local resilience, reduce energy poverty and stimulate endogenous economic development, provided that adequate governance frameworks and stable financial instruments are in place [

54,

55,

56,

57].

In this context a particularly important role is played by initiatives based on the cooperation of local actors, including energy communities [

58], which facilitate diffusion of innovations and incorporation of local communities in the transition processes. As a consequence, the low-carbon economy is becoming not only an instrument of climate policy, but also a new paradigm for endogenous development, offering opportunities to strengthen the potential of peripheral and rural areas in the EU territorial structure.

For rural and border communes, this transition constitutes both a challenge for investment and an opportunity to overcome peripherality thanks to the development of local energy markets and improvement in the standard of technological infrastructure, as well as the activization of their economy based on endogenous resources [

59,

60]. Local government units, as entities implementing energy and climate policy, play an important role in this process. Their involvement in thermal upgrade projects, investments in renewable energy sources, local heating networks, or sustainable transport, fulfils not only the objectives of the EU and national climate strategies, but also supports the long-term socio-economic development of peripheral regions [

61].

Within the EU climate policy rural areas serve dual roles. On the one hand, they are significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions, e.g., agriculture in Poland is responsible for approximately 8.5% of total GHG emissions, including 37.5% of methane and over 80% of nitrous oxide [

62]. On the other hand, they are equipped with considerable potential for the development of renewable energy sources and sustainable resource management [

12,

63]. Local resources, such as biomass and biogas, constitute an important basis for local power systems, including heating networks and energy clusters [

64,

65]. At the same time, wind and solar energy are gaining in importance in rural areas, where planning the locations for respective installations while respecting spatial conditions is feasible [

66]. The latest data confirm rapid increases in the number and capacity of small renewable energy installations (PV, wind, and biogas), which is manifested in increased energy self-reliance [

67], while providing tangible fiscal benefits for local government units. As a result, investments in biogas plants, wind farms and photovoltaic farms support the diversification of the local economy and improve the standard of the technological infrastructure, enhancing the socio-economic resilience of peripheral areas [

68].

From the perspective of local government units, low-carbon investments implemented in rural communes may also interact indirectly with the functioning of the agricultural sector, particularly in areas where bioenergy projects or biomass-based heating systems are developed [

69,

70]. Such projects can influence local patterns of land use and the availability of biomass resources, which in turn may shape production conditions for farms [

71]. At the same time, bioenergy-related initiatives may contribute to income diversification and support rural development, as documented in studies on agricultural biogas and renewable energy uptake in rural areas [

72]. Therefore, in rural communes, the assessment of low-carbon investment policies should take into account not only energy and climate objectives, but also their potential indirect linkages with rural development processes.

However, implementation of such investments requires adequate institutional and financial potential, as well as a stable legal environment. In practice many communes continue to face financial, procedural and social barriers resulting from their limited fiscal potential, lack of sufficiently adapted transmission networks, ambiguous regulations, or lack of social acceptance (e.g., for the location of investments in renewable energy sources). Studies indicate that a major barrier for investments in RES in communes is connected with insufficient development of electricity grids. For example, Kryszk et al. [

73] showed that the availability of so-called hosting capacity constitutes a key limiting factor. In turn, investigations conducted by Kata and Pitera [

15] indicate that investments in energy transition made by communes in Poland are strongly dependent on subsidies and are faced with considerable fiscal barriers. In rural and peripheral areas, research has indicated that a lack of initiative on the part of local government units, excessively bureaucratic procedures, and limited social acceptance constitute significant barriers to the development of the green economy [

74].

Energy transition in peripheral regions is implemented under multi-level governance (MLG), which assumes cooperation of local, regional, national and EU institutions [

75]. Since the transition process requires both strategic decisions and implementation at the commune level, MLG facilitates coordination of climate and energy policies at all these levels. In such a system local government units are both beneficiaries and initiators of actions promoting reduction of GHG emissions and improved energy efficiency, as confirmed by studies on regional energy transition processes [

76].

Contemporary studies strongly emphasize the role of local governments as key intermediaries in steering energy transition in peripheral regions after 2020. Recent empirical evidence indicates that municipalities play a decisive role in initiating renewable energy projects, coordinating local stakeholders and facilitating access to public support schemes and EU climate funds [

55,

77,

78]. At the same time, research consistently points to persistent institutional and socio-spatial asymmetries between urban cores and peripheral communes, which translate into differentiated administrative capacities, financial resources and planning potential for the implementation of low-carbon investments [

48].

Despite the growing number of analyses concerning the role of communes in the low-carbon economy, the literature on the subject indicates a lack of research referring to the unique character of border regions. The scope of a marked majority of studies is the national or provincial scale, while analyses concerning communes are scarce. However, it is in those regions that energy transition processes may be of particular importance, constituting both a financial and organizational burden, and a chance to utilize local environmental resources and improve investment and tourism attractiveness in the areas. The location within the border zone may have a dual effect: as a barrier to development (transportation exclusion, limited market accessibility, poor technological infrastructure, and adverse demographic trends), but also factors providing unique opportunities, facilitating the use of cross-border cooperation mechanisms [

79]. In this respect the Interreg programs are of particular importance (e.g., Poland–Lithuania, Poland–Ukraine, and Poland–Slovakia), as they support investments aimed at energy efficiency and renewable energy sources [

80].

In recent years an increasingly important role in the development policies in these areas has been played by energy transition, which is becoming a new paradigm for endogenous development. As was observed by Furmankiewicz et al. [

81], the present-day concept of neoendogenous growth assumes the utilization of local resources and social and natural potential in the establishment of sustainable foundations for development at the commune level. According to a European Commission report [

82], investments in RES financed within the cohesion policy in the years 2021–2027 are key instruments supporting the sustainable development of peripheral regions. In turn, the policy document European Funds for Eastern Poland 2021–2027 [

83] indicates that energy transition is considered to be the primary direction for economic and social modernization in Eastern regions of Poland.

In recent years, border regions have attracted growing attention in research on energy transition, particularly in the context of cross-border governance, infrastructure integration, and regulatory coordination [

84]. Studies indicate that cross-border peripheral areas face specific challenges related to institutional fragmentation, infrastructure discontinuity and exposure to geopolitical risks [

85], which strongly affect their low-carbon transformation pathways. At the same time, EU territorial cooperation frameworks, including the Connecting Europe Facility, are identified as key instruments supporting cross-border renewable energy projects and energy infrastructure investments [

86]. These findings confirm that border location may simultaneously constrain and stimulate local energy transition pathways.

In this context, rural and urban–rural communes in the border regions of Eastern Poland increasingly often serve the role of laboratories for local transition, utilizing EU funds, local sources of renewable energy, and cross-border cooperation. However, there is still a shortage of systemic analyses showing to what degree spatial factors, such as location within the border region and location in relation to Functional Urban Areas (FUA), diversify the scale and character of investments in the low-carbon economy. It is necessary to fill this gap in order to assess the diversification of the trajectory of energy transition in Eastern Poland, as well as to design effective instruments of this policy adapted to specific local conditions and supporting sustainable development of peripheral regions.

3. Materials and Methods

The investigations covered communes (basic local government units) in Poland, with the Eastern Macroregion (comprising the Podlaskie, Lubelskie, and Podkarpackie voivodships, i.e., the border regions of Eastern Poland) constituting the primary area of analysis and a reference point in comparisons to the rest of Poland. The settlement structure of the Eastern Macroregion, with its predominance of rural communes (approximately 70% compared to approximately 60% on the national scale) as well as a considerable share of non-agglomeration units with a low population density (almost 40%), justifies the selection of rural and urban–rural communes as the main object of analysis [

24,

87].

Studies on the level and diversification of investment activity in communes aimed at the low-carbon economy in the Eastern Macroregion were conducted using the classification developed by Statistics Poland (GUS), i.e., Delimitation of Rural Areas (Polish: Delimitacja Obszarów Wiejskich, DOW), which was prepared using the typology of functional urban areas (FUA), covering urban cores and their commuter belts. The Delimitation of Rural Areas classifies rural communes and rural parts of urban–rural communes, including the impact of large urban centers on these communes, and it is a two-layer analysis [

24]:

- ▪

Level 1—the location of communes within FUAs of provincial cities or other cities of ≥150 thousand inhabitants (two categories are distinguished here, i.e., agglomeration and non-agglomeration communes).

- ▪

Level 2—population density—in each of the groups of communes distinguished according to Level 1, units of high density (greater than the national average in the case of agglomeration communes or greater than 1/3 national population density in the case of non-agglomeration communes) and those of low population density (equal to or lower than the national average in the case of agglomeration communes or equal or lower than 1/3 national population density in the case of non-agglomeration communes).

Since the Delimitation of Rural Areas ascribes classes separately for the urban and rural parts of the urban–rural communes, while available data on implemented investments in the low-carbon economy concerns communes as a whole, it was necessary to adopt one class of the Delimitation of Rural Areas for an entire urban–rural commune. In the analyses, the urban–rural communes were ascribed the class within the Delimitation of Rural Areas typical for their rural part (TERYT = 5).

According to the adopted classification of rural and urban–rural communes, analyses were conducted concerning the number and value of EU funds acquired for purposes related to the low-carbon economy, while the intensity of executed investments is presented per capita and area units. Data concerning the projects came from the databases of the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy (concerning the financial frameworks of 2007–2013 and 2014–2020) [

88,

89]. From several dozen thousand projects, those classified as low-carbon economy were selected. The other data were collected from the Local Data Bank (Polish: Bank Danych Lokalnych GUS) of Statistics Poland [

87]. The data quoted in the text were converted according to the National Bank of Poland’s average exchange rate [

90]. The calculations were performed using Statistica software (version 13.3).

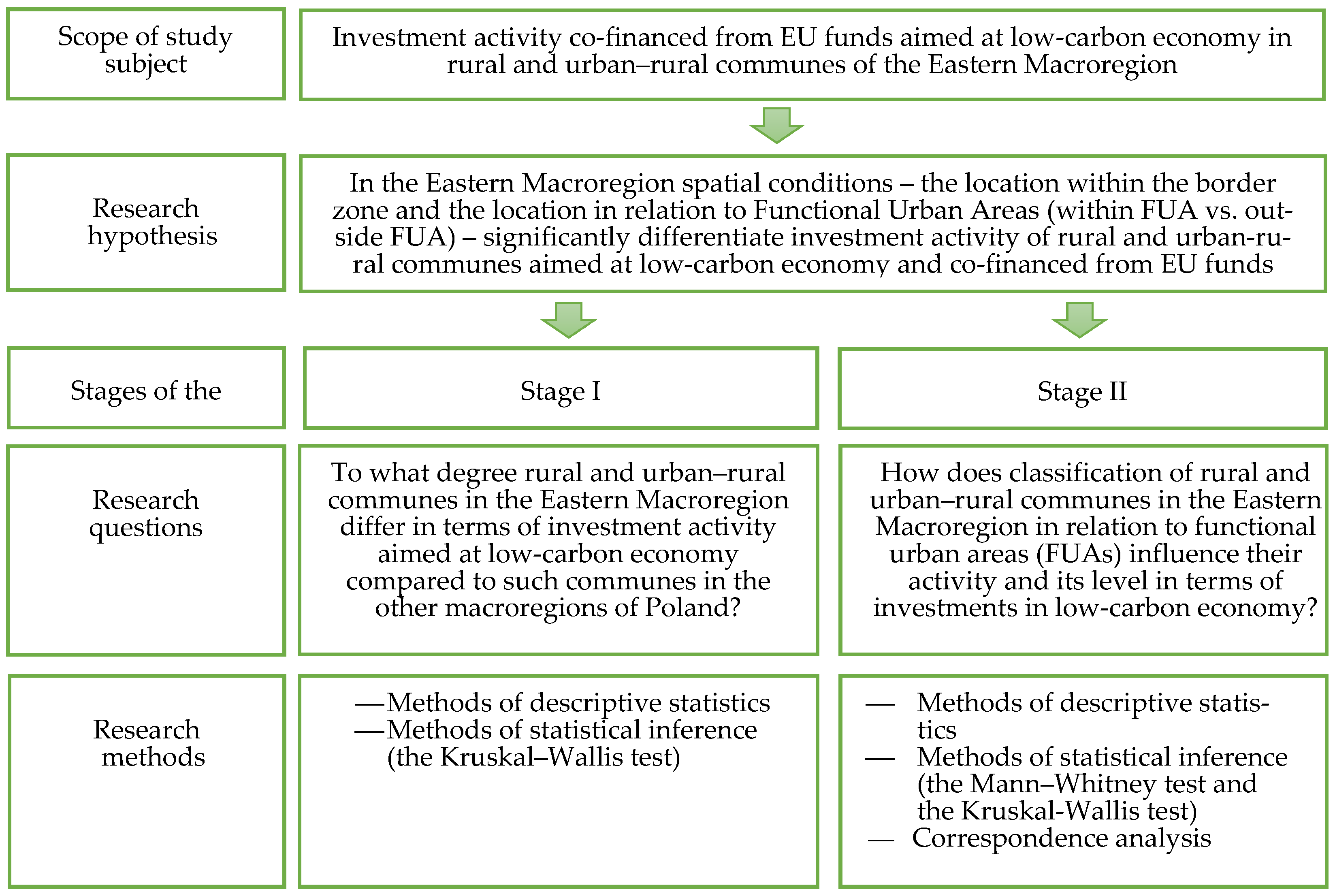

Empirical studies conducted in two stages were required to attain the assumed aim of the study (

Figure 1). The first stage analyses, in order to assess investment activity aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy, concerned both the activity and the number and value of respective projects acquired by rural and urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion compared to the other macroregions of Poland. In the study, a combined approach to investment expenditures related to the development of the low-carbon economy was adopted, which made it possible to capture the overall level of investment activity of communes in this area. It should be noted, however, that particular types of investments—those related to energy efficiency, renewable energy sources, transport, or municipal infrastructure—differ in terms of cost scale and financing mechanisms. This constitutes an important interpretative limitation and an indication for further research. At this stage of the analysis, methods of descriptive statistics and statistical inference (non-parametric tests for comparisons of several independent samples—the Kruskal–Wallis test) were applied for this purpose [

91,

92].

The second stage of the study consisted of the assessment of the investment activity of rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion. Both the activity and the level of investments co-financed by EU funds aimed at the low-carbon economy were evaluated in terms of these parameters per capita and per unit area (km

2) of communes according to delimitation types. In this part of the study methods of descriptive statistics as well as statistical inference were used. To ensure the appropriate selection of statistical methods, the study was preceded by verification of the distribution of the dependent variable within the analyzed groups. Both graphical analysis (histograms) and the Shapiro–Wilk normality test were applied to assess the shape of the distribution. Due to its high power and accuracy, the Shapiro–Wilk test is recommended for samples of this size [

93]. In cases where the assumption of normal distribution was not met, non-parametric tests were used, such as the Mann–Whitney test for comparisons of two independent samples and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons of several independent samples [

91,

92].

The results of the tests served as a starting point for further exploration of structural relationships. In order to investigate dependencies between the types of rural and urban-rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion following the Delimitation of Rural Areas and the level of their investments in the low-carbon economy, correspondence analysis was applied. It is a method of exploratory data analysis for qualitative data [

94]. It is a statistical approach facilitating graphical display for the structure of dependencies between categorical data in a two-dimensional space. The correspondence analysis does not have to meet assumptions of normal distribution or homogeneity of variance, which distinguishes it from many classical parametric methods [

95].

Relations between categories of two variables were the object of analysis here. The first variable was the type of rural and urban–rural communes in Eastern Poland according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas (agglomeration vs. non-agglomeration, differentiated in terms of their population density). The other variable was the level of investments in the low-carbon economy per capita and per unit area (km

2). The quantitative variable was categorized into four classes based on the quartiles of its distribution, representing different levels of capital expenditure: none or low (values below or equal to the bottom quartile), mean lower (above the lower quartile and lower or equal to the median), mean higher (above the median and below or equal to the upper quartile), and high (values exceeding the upper quartile). This approach limits the influence of extreme observations and allows complex relationships to be presented in the form of an interpretable correspondence map. This method does not replace quantitative analysis but rather complements it, allowing for a graphical representation of relationships and similarities between categories in a two-dimensional space. The choice of correspondence analysis was justified by the need to identify patterns of associations between the type of local government unit and the categories of investment levels, while maintaining the ability to present the results synthetically within a factorial space [

94].

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the analysis is limited to projects co-financed from European Union funds. As a result, investments financed exclusively from national or local sources are not included, which may lead to an underestimation of the total scale of low-carbon investment activity in communes. Nevertheless, the use of EU-funded projects ensures data availability, consistency, and spatial comparability. Second, the identification of projects related to the low-carbon economy is based on their classification in official program databases. Due to the multi-purpose character of many public investments, some projects may generate only indirect climate effects, while others may include components that are not strictly related to emission reduction. This introduces a degree of uncertainty in assigning projects to the low-carbon category. Third, various types of low-carbon investments—such as energy efficiency, renewable energy sources, transport, and municipal infrastructure—were analyzed jointly, despite differences in their cost structures, implementation scales, and financing mechanisms. Therefore, the results reflect overall investment activity rather than sector-specific patterns.

4. Results

4.1. Border Areas in Transition Towards Low-Carbon Economy: Investment Activity of Rural and Urban–Rural Communes in the Eastern Macroregion Compared to the Other Regions of Poland

In view of the considerable spatial diversification of Poland [

23], including, among other things, differences in the income potential of local government units, structure and demographic trends (depopulation and population aging), transportation and market accessibility (duration of travel to provincial centers and network density), economic structure (share of agriculture and share of SMEs), technological potential, and conditions for development of renewable energy sources (insolation, wind, biomass and grid connectivity), it is justified to conduct the analysis at the macroregional scale. In the case of the Eastern Macroregion, it is additionally advisable to refer to the above-mentioned DRA [

24], which distinguishes agglomeration and non-agglomeration communes of high and low population density, making it possible to precisely identify its peripheral character and its impact on the scale and intensity of low-carbon investments. In the peripheral regions of Eastern Poland rural and urban–rural communes predominate in the structure of local government units, while at the same time they face challenges typical of such peripheries, such as scattered settlement patterns, lower population density, population aging, less developed entrepreneurship, and limited income potential [

23]. These conditions may influence both the number and value of projects aimed at the low-carbon economy implemented by local government entities.

Investments of communes aimed at the low-carbon economy (including renewable energy sources) constitute a major channel for the implementation of EU climate and energy goals at the local level. In EU financial frameworks, i.e., in the years 2007–2013 and 2014–2020, financing came primarily from the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund (e.g., regional operational programs) and territorial cooperation programs (e.g., Interreg). According to the results of research conducted by Standar et al. [

22], communes in Poland within the two most recent financial frameworks were the primary beneficiaries, utilizing approximately half the number and value of national projects aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy.

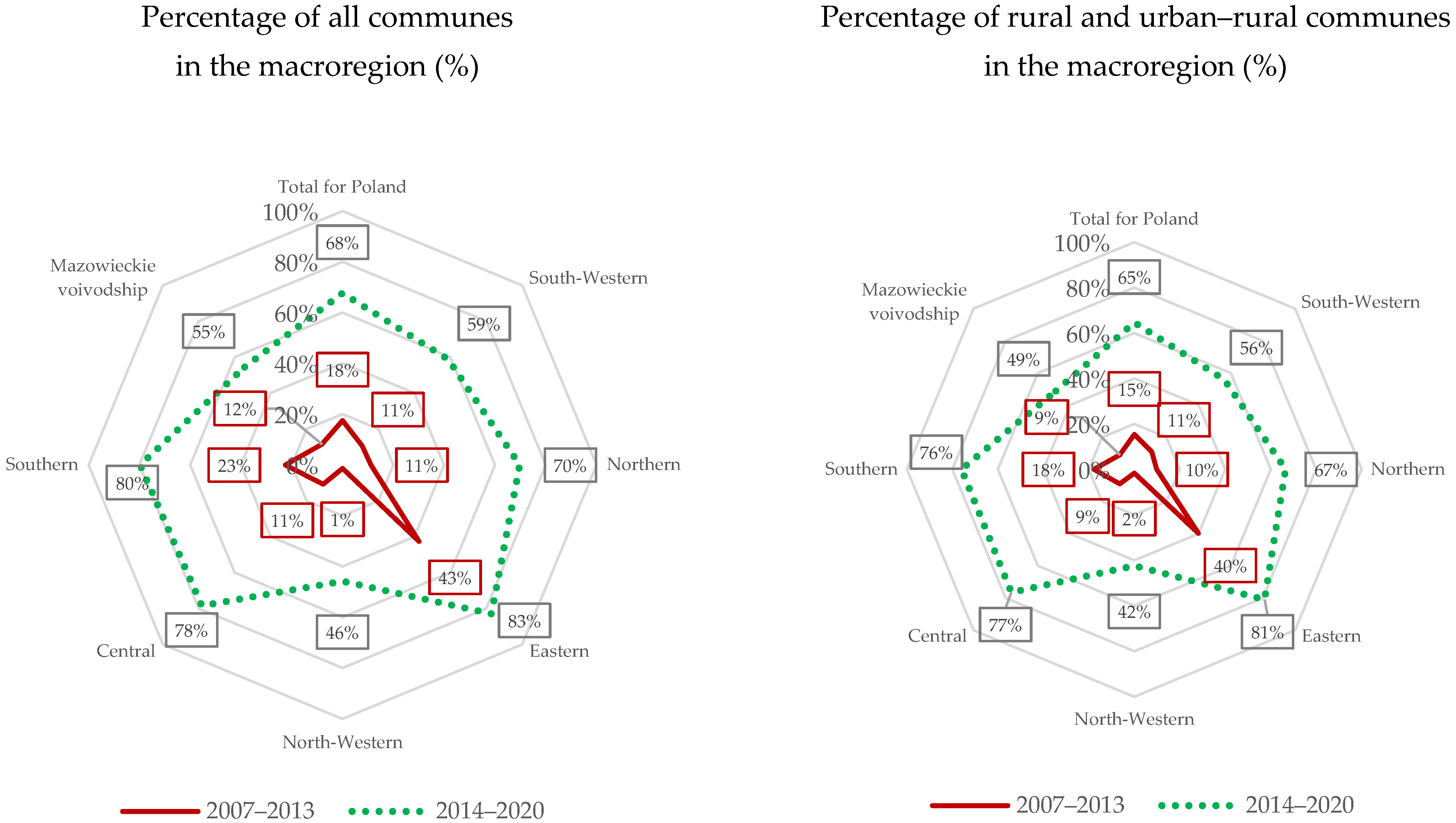

Between both these financial frameworks, a significant change occurred both in the scale and level of maturity of the discussed actions. While the years 2007–2013 may be defined as the initial stage, the years 2014–2020 marked a definite popularization of the discussed investments as well as a considerable expansion of their range among communes. As indicated by data presented in

Figure 2, the level of participation increased, understood as the percentage of communes which implemented at least one project related to the development of the low-carbon economy. This index may be treated as a measure of the diffusion of public policy, referring to the local government units entering the program, while at the same time it supplements indexes showing the intensity of the investigated phenomenon. On the national scale, the participation index increased from 18% in the years 2007–2013 to 68% in the period 2014–2020, which confirms the transition from the pilot phase to the stage of extensive implementation. In this respect, the Eastern Macroregion was distinguished by the greatest activity in both these financial frameworks, as in 2007–2013 the percentage of communes implementing these projects already amounted to 43%, while in the years 2014–2020 it reached 83%. Within the second discussed financial framework, comparable values were recorded in the Southern (80%) and Central Macroregions (78%), while they were lower in the Northern (70%), South-Western (59%), Mazowiecki (55%) and North-Western Macroregions (46%). The greatest increments in the values of the index were recorded in regions with low initial levels; i.e., in the Central (+68%), Northern (+59%), and Southern Macroregions (+57%). The range between the macroregions decreased markedly (from approximately 1–43% to 46–83%), which indicates convergence in the level of investment activity aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy, with the Eastern Macroregion maintaining the leading position (

Figure 2).

An analogous pattern was observed in the group of rural and urban–rural communes. On the national scale the percentage of entities, wChich implemented at least one project increased from 15% in the years 2007–2013 to 65% in the period 2014–2020 (i.e., by 49%), which confirms significant popularization of investments aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy outside large cities. The Eastern Macroregion maintained its leading position in both financial frameworks, recording an increase from 40% to 81% (i.e., +41%), although the increase was slightly lower than in the regions starting from relatively low initial levels, such as the Central (+68%), Southern (+58%), or Northern Macroregions (+57%). The difference between the macroregions in terms of the share of rural and urban–rural communes acquiring and implementing projects co-financed by EU funds and aimed at the low-carbon economy decreased markedly. This means that the level of participation of these communes in individual parts of Poland was increasingly similar. At the same time, the Eastern Macroregion maintained its leading position, while the North-Western Macroregion and the Mazowieckie Voivodship were below average in the second of the investigated financial frameworks (

Figure 2).

In both analyzed financial frameworks, communes were allocated acquired funds primarily to thermal upgrade of public buildings, street lighting, local heating systems, development of renewable energy systems, sustainable mobility, and supplementary measures (such as energy management or education) [

88,

89]. In the years 2014–2020 compared to 2007–2013, the number of communes implementing similar projects increased considerably, with the projects having greater budgets (

Figure 2,

Table 1). As shown by the results from the data provided in

Table 1, in both investigated financial frameworks, Polish communes jointly completed approximately 4.9 thousand projects aimed at the low-carbon economy, acquiring for this purpose almost PLN 40 billion (EUR 9.5 billion). A significant majority of these enterprises was conducted in the years 2014–2020 (over 85%). Among them rural and urban–rural communes accounted for approximately 3.5 thousand investment projects (over 70% of projects), with a total value exceeding PLN 11.5 billion (EUR 2.7 billion) (approximately 30% of the total;

Table 1).

It needs to be stressed that in the years 2014–2020, compared to the previous financial framework, the frameworks for the implementation of low-carbon measures were significantly standardized. Among other things, ex ante and ex post energy audits became commonly applied procedures, a set of universal indexes to monitor effects was introduced, while the application procedure was standardized. These changes also included local government units, which promoted the execution of routine packages of measures, such as thermal upgrades to multiple structures, modernization of lighting systems, and installation of local renewable energy sources, all resulting in a greater scale of implemented projects and increased stability of unit costs, as well as more predictable energy and emission levels [

96].

Table 1 presents the distribution of the number of projects and the value of acquired funds in the macroregions, both jointly for all communes and separately for rural and urban–rural communes. This approach makes it possible to identify the unique character of the Eastern Macroregion compared to the other parts of Poland in relation to the analyzed phenomenon. In the further stages of this analysis, these compilations were supplemented with data converted to unit measures (per capita and per km

2).

In the Eastern Macroregion, communes completed almost 1.4 thousand projects (i.e., over ¼ of their total number in the country), the value of which exceeded PLN 6.7 billion (EUR 1.6 billion) (i.e., almost 17% of their total value in Poland). Between the two financial frameworks, a marked increase in activity was observed: the number of projects went up from 321 to 1048 (over 3-fold), while their value increased from PLN 0.75 billion to as much as PLN 5.97 billion (from EUR 0.17 billion to EUR 1.4 billion) (almost 8-fold). In both financial frameworks the Eastern Macroregion ranked first in Poland in terms of the number of acquired projects, whereas in terms of their value it ranked third, after the Mazowieckie Voivodship and the Southern Macroregion (

Table 1).

The importance of the Eastern Macroregion was even more evident in the group of rural and urban–rural communes. These units implemented over 1.1 thousand projects (over 80% of all such enterprises in the macroregion) valued at approximately PLN 3.3 billion (EUR 0.8 billion) (almost a half of their total value). In both financial frameworks rural and urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion maintained the leading position on the national scale, both in terms of the number of projects and the value of acquired funds. During the analyzed period, almost every third project in this category of communes co-financed by EU funds was implemented in the Eastern Macroregion—they accounted for approximately 32% of their total number and over 28% of the value of such investments (

Table 1).

Summing up, the unique character of local government activity in the Eastern Macroregion needs to be stressed here, as projects completed by rural and urban–rural communes accounted for over 80% all enterprises, at the national level slightly over 70%. In terms of the financial value, the share of this group reached almost 50%, with less than 30% at the national scale. These data indicate that investments co-financed by EU funds and aimed at the low-carbon economy in the peripheral regions of Eastern Poland were predominantly rural, which justifies the need for further in-depth analysis of this category of communes.

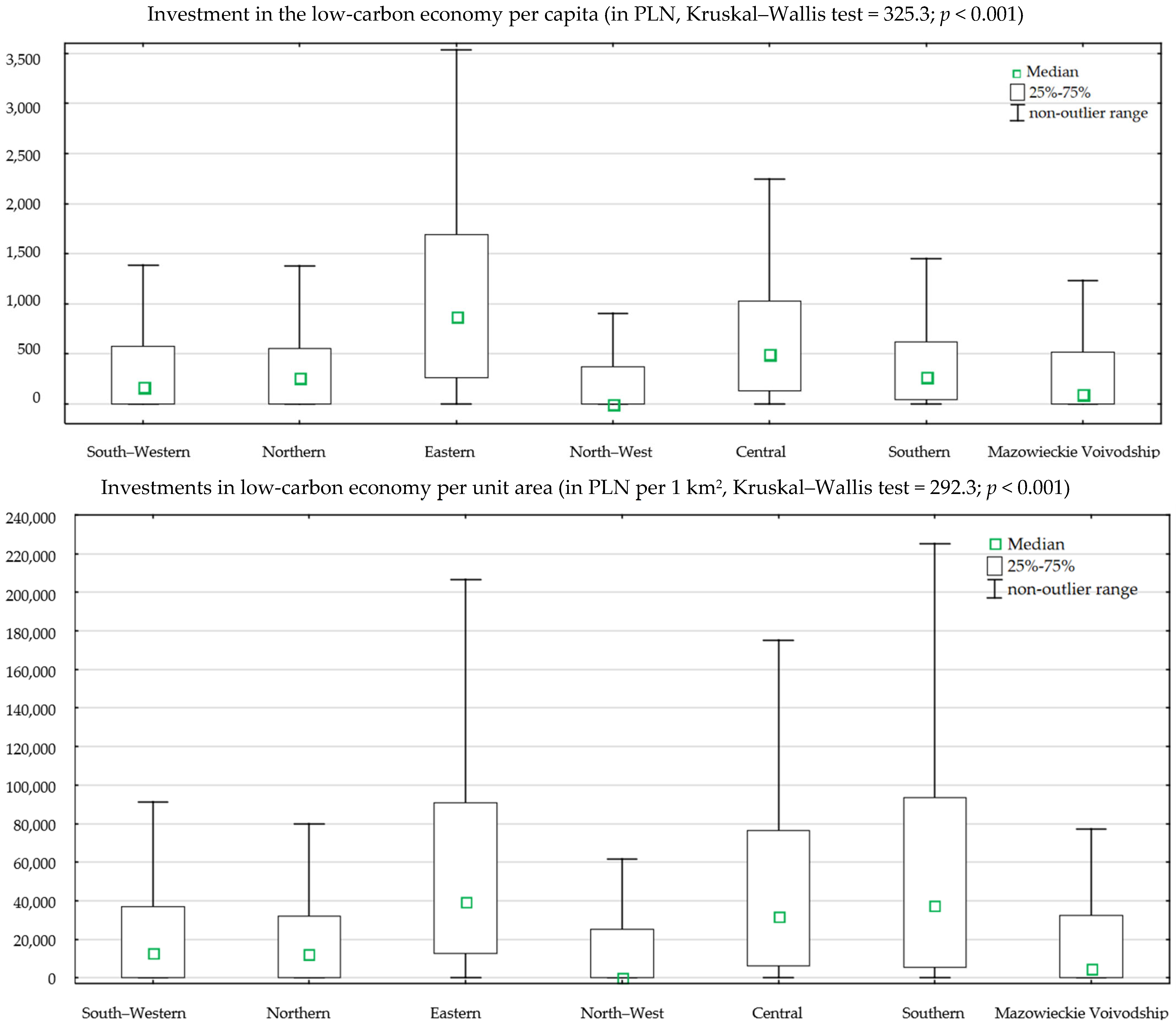

Figure 3 shows the average value of projects aimed at the low-carbon economy completed in the years 2007–2020 by all communes jointly and by rural and urban–rural communes in the macroregions of Poland. Statistical analysis conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed that differences in medians for acquired funds per capita and per 1 km

2 between the macroregions are statistically significant (

p < 0.05). The highest value was recorded in the Eastern Macroregion. The median of funds acquired by urban–rural communes in that macroregion amounted to over PLN 870 per capita (EUR 207 per capita) and over PLN 39 thousand/km

2 (EUR 9.3 thousand per km

2), whereas on average on the national scale these values were PLN 275 (EUR 65.5 per capita) and slightly below PLN 17 thousand/km

2 (EUR 4.1 thousand per km

2). This means that the intensity of investment activity in urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion was over 3-fold higher per capita and over 2-fold higher per 1 km

2 compared to the national mean. When interpreting these results, it needs to be stressed that the high values per unit area indicate that the advantage of the Eastern Macroregion does not result solely from demographic factors (i.e., the smaller population size), but also reflects greater accumulation of outlays in spatial terms. Relatively high medians per 1 km

2 were also recorded in the Southern Macroregion (almost PLN 38 thousand/km

2, i.e., EUR 9.1 thousand per km

2) and the Central Macroregion (approximately PLN 31.5 thousand/km

2, i.e., EUR 7.5 thousand per km

2), although this was at lower values per capita (amounting to PLN 265 and PLN 502 per capita, i.e., EUR 63 and 120 per capita). This indicates a different combination of demographic and spatial conditions, as a more compact settlement structure promotes high outlays per unit area, but it is not reflected proportionally in the intensity of investment activity per capita. In turn, the Northern and South-Western Macroregions ranked below the mean in both categories of these indexes.

4.2. Between Functional Urban Areas and Peripheries: Investment Activity of Rural and Urban–Rural Communes in the Eastern Macroregion

In the Eastern Macroregion, the activity of communes to acquire EU funds for enterprises aimed at the low-carbon economy constituted a significant mechanism for the implementation of climate and energy policies at the local level. However, the scale of this activity is far from uniform—it varies depending on the type of rural and urban–rural communes, classified according to delimitation typology. This distinction into agglomeration and non-agglomeration communes and into units with high and low population densities makes it possible to separate the impact of location in relation to Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) from the influence of the internal settlement structure, determining unit costs and the character of potential investments.

In the Eastern Macroregion, a definite majority of rural and urban–rural communes are non-agglomeration communes (approximately 83%). In this group, proportions of communes with low (52%) and high population density (48%) are comparable. This structure differs from the national figures, where units with a high population density (55% of the total) predominate among non-agglomeration communes. Agglomeration units in the Eastern Macroregion account for less than 17% of all rural and urban–rural communes, which is 2% less than the national mean, while units with a low population density predominate there [

24].

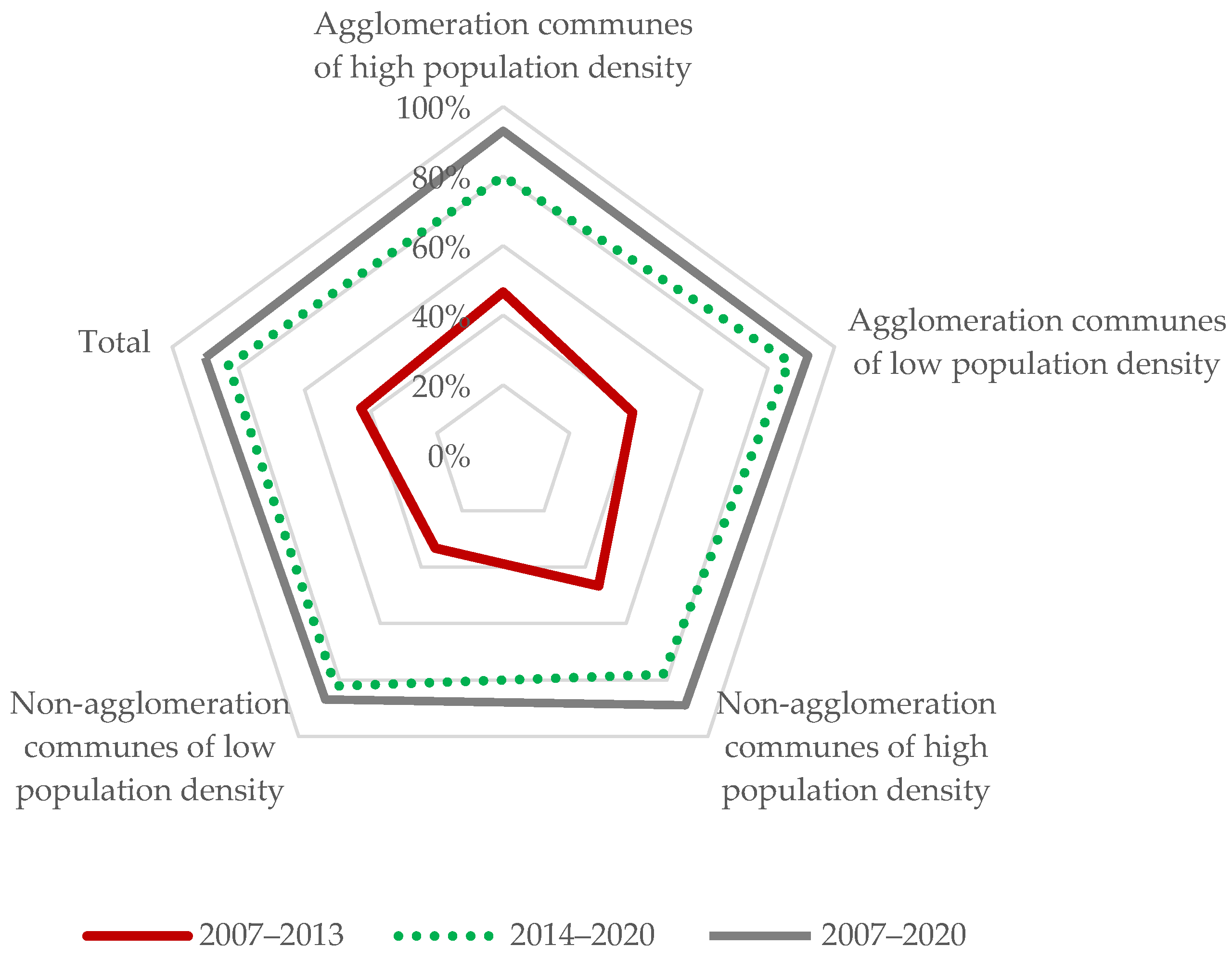

In the next part of the analysis, the popularity of low-carbon measures was assessed in rural and urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion, assuming as a measure the percentage of communes which acquired at least one project within a given financial framework. A comparison of the years 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 makes it possible to identify the transition from the pilot phase to the stage of common participation, whereas the joint presentation for the entire period of 2007–2020 makes it possible to assess stability and range of participation within a longer timeframe.

In the years 2007–2013, the investment activity of rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion was moderate and markedly varied—from 33% in non-agglomeration communes with low population density to almost 47% in agglomeration communes with high population density. However, in the succeeding financial framework (2014–2020), a definite increase in that activity was recorded. The highest level was found for agglomeration communes with low population density (over 86%), while it was lowest in non-agglomeration communes with low population density (78%). The dynamics of change were most evident in the groups of communes with low population density, both in agglomeration (an increase by over 47%) and non-agglomeration communes (by almost 49%). The increase in investment activity among communes with high population density was smaller, although it was still considerable (by over 33% in agglomeration communes and by almost 32% in non-agglomeration ones) (

Figure 4).

When investigated jointly for the years 2007–2020, the participation of rural and urban–rural communes in low-carbon projects was almost universal, as it reached 93% in agglomeration communes of high population density, 92% in agglomeration communes of low population density, 89% in non-agglomeration ones with high population density, and 87% in non-agglomeration communes of low population density (

Figure 4). This shows convergence between types specified in the Delimitation of Rural Areas and transition from selective implementation (2007–2013) to the extensive popularity of the discussed actions (2014–2020). The greatest dynamics of change were observed in communes with low population density, which suggests that the accumulation of project activity promoted acquisition of expertise on the part of local organizations and diffusion of good practice in the entire macroregion. At the same time, it needs to be stated that there is a certain group of communes (from 7% to 13%, depending on their type), which in both financial frameworks implemented no projects aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy. It is these communes that should be a priority target group for interventions in the current financial framework of 2021–2027.

In the years 2014–2020, there was a marked popularization and increase in the scale of actions undertaken by rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion. Overall, they completed over 1.1 thousand projects worth approximately PLN 3.3 billion (EUR 0.8 billion), of which the second investigated financial framework accounts for over 77% of the number and more than 82% of the value. The average value of a project increased from approximately PLN 2.3 million (EUR 0.6 million) in the years 2007–2013 to approximately PLN 3.1 million (EUR 0.7 million) in the years 2014–2020, which indicates the increased financial scale of this activity (

Table 2).

In terms of their types according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas, the greatest share in the number and value of projects was found for non-agglomeration communes, which completed a total of 881 projects worth over PLN 2.5 billion (EUR 0.6 billion). However, it needs to be remembered that they constitute approximately 83% all rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion (half of them with low and half with high population density), while agglomeration communes account for less than 17%, being predominantly entities with low population density. Thus, the predominance of communes located outside FUAs in the joint presentations of data is partly the effect of population structure. In this respect, agglomeration communes with high population density are exceptions to the trend, since despite the relatively low number of projects (44) they acquired a total of PLN 266.6 million (EUR 63.5 million), which is equivalent to a unit value above the average (approximately PLN 6.1 million, i.e., EUR 1.5 million). This indicates the implementation of more capital-intensive, integrated projects, such as the thermal upgrade of many buildings or systemic modernization of lighting, taking advantage of the economies of density.

Analysis of the division into communes located within FUAs and those outside these areas confirms the dominance of entities outside FUAs, which accounted for over 78% of the total number and almost 77% of the value of the projects in the region. However, this advantage decreased in the second of the investigated financial frameworks. In the years 2007–2013, the ratio of the number of projects implemented outside FUAs to those within FUAs was approximately 5:1 (219/38; 497/84.5 PLN million), while in the years 2014–2020 it dropped to 3:1 (662/209; 2010.6/670.7 PLN million) (

Table 2).

In the Eastern Macroregion, in the group of rural and urban–rural communes, the median for the value of acquired projects aimed at the low-carbon economy per capita in the first financial framework (2007–2013) amounted to PLN 0 in all types of communes classified according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas (

Table 3). This means that at least a half of communes in each category did not acquire any projects for this type of activity within this period, which is consistent with the early period of formation of the support system and the limited availability of stable, predictable, and standardized financing mechanisms for investments made by local government units concerning energy efficiency and renewable energy sources.

In the second investigated financial framework (2014–2020), a definite popularization of these measures was observed and medians for the values of acquired projects aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy per capita significantly increased, particularly in the group of communes with low population density, including both agglomeration and non-agglomeration communes. The fact that even within FUAs, the median for the value of investments in the low-carbon economy per capita was higher in the group of communes with low rather than high population density indicates that the diversification is caused not only by the location of these territorial units in relation to urban cores, but also by the character of the settlement structure itself.

As previously mentioned, among rural and urban–rural communes, the highest average amount of funds acquired in low-carbon projects co-financed by EU funds per capita was recorded in territorial units of low population density. In agglomeration communes of this type, this amounted to almost PLN 925 per capita (EUR 220 per capita), while in non-agglomeration communes it was over PLN 901 (EUR 215 per capita). Furthermore, in the latter group, the greatest diversification was observed between the quartiles, which shows strong differentiation of individual investment trajectories. Slightly lower values were recorded in non-agglomeration communes of high population density (approximately PLN 872 per capita, i.e., EUR 208 per capita), while markedly the lowest values were in agglomeration communes with high population density (PLN 276 per capita, i.e., EUR 66 per capita) (

Figure 5).

This system suggests that in less populated parts of the macroregion, typical modernization packages (e.g., thermal upgrades of public buildings, modernization of street lighting using LED systems, and microinstallation of renewable energy sources) generated relatively stronger effects per capita. It was different for agglomeration communes with high population density, where the median was markedly lower. This resulted both from the higher population denominator, and a different investment profile, in which a significant role was played by competition for funds other than low-carbon projects.

Figure 5 presents a total median for the value of low-carbon projects acquired by rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion expressed per unit area (1 km

2), depending on the division into delimitation types. In the entire macroregion, the median amounted to almost PLN 46 thousand/km

2 (EUR 11 thousand per km

2). The highest value was recorded in non-agglomeration communes with high population density (PLN 56.5 thousand/km

2, i.e., EUR 13.5 thousand per km

2), which was slightly higher than in agglomeration communes of high population density (PLN 51.7 thousand/km

2, i.e., EUR 12.3 thousand per km

2) and agglomeration communes of low population density (PLN 50.8 thousand/km

2, i.e., EUR 12 thousand per km

2). Differences between these two types of agglomeration communes were slight (1–2%), whereas the advantage of non-agglomeration communes with high population density and agglomeration communes reached approximately 10%.

In the group of agglomeration communes of high population density, nevertheless, a marked interquartile range was observed, showing high heterogeneity in terms of the intensity of investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy. This diversification may have resulted from several factors. Firstly, it may be influenced by the effect of area and the share of urbanized area. In smaller communes with a denser settlement and building structure the same amounts manifested in higher values per 1 km2, while in larger communes, they were distributed over a larger area. Secondly, from different profiles of the investment portfolio, communes implementing grid investment projects (e.g., modernization of street lighting systems and thermal upgrade packages for multiple buildings) attained greater intensity of spatial outlays compared to communes in which single point projects predominated. Thirdly, a significant role could have been played by differences in institutional and fiscal potential, access to territorial instruments (cross-border cooperation), and technological conditions (e.g., grid connectivity and standard of municipal infrastructure assets), which directly determined the scale and type of feasible measures.

The lowest level of investments aimed at the low-carbon economy per unit area was recorded in non-agglomeration communes of low population density (PLN 24.4 thousand/km2, i.e., EUR 5.8 thousand per km2), which constituted approximately half of the value acquired in the other three types of rural and urban–rural communes. This distribution is consistent with the logic of the spatial index, i.e., in territorial units of large area, frequently characterized by a high share of forested areas and protected areas, outlays are distributed more uniformly and are more markedly scattered, while their lower urbanization rate additionally limits intensity in terms of value per 1 km2.

The relatively high investment activity observed in peripheral communes should be interpreted in the context of their structural constraints. Limited fiscal capacity, dispersed settlement patterns, and ageing energy infrastructure increase the sensitivity of these areas to energy costs and external supply risks. Under such conditions, EU co-financing becomes a crucial enabling factor, allowing peripheral local governments to overcome investment barriers and actively participate in low-carbon transition, despite long-term development disadvantages.

Recorded research results constituted the basis for an in-depth intraregional analysis. Mann–Whitney tests confirmed that the significant differences in the level of investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy between communes located within and those outside FUAs were observed when converting the value of acquired projects into respective figures per unit area (km

2). Overall, for the entire period of analysis (2007–2020) no significant differences were found in the level of investment per capita between communes located within an FUA and those outside FUAs (median: PLN 752.7 vs. 877.9/person;

U = 13,288,

p = 0.74). This indicates that when expressed in values per capita the investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy was comparable regardless of the communes’ location in relation to Functional Urban Areas. Furthermore, the division into types of communes according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas did not differentiate statistically significantly the level of investments in the low-carbon economy per capita. Despite marked differences in medians (e.g., a lower value in agglomeration communes of high population density), considerable dispersion, including the recorded zero values, leads to lack of significance at typical α levels (

Table 4).

A different situation is found for investments in the low-carbon economy in rural and urban–rural communes of the Eastern Macroregion per unit area (km2). Communes located within FUAs attained higher spatial intensity of outlays than communes located outside FUAs (PLN 51.2 thousand vs. 35.3 thousand/km2; U = 18,789, p = 0.02). Statistically significant differences were also found between types of communes distinguished according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas (H = 38.87, p < 0.001). The lowest median was recorded in non-agglomeration communes of low population density (PLN 24.4 thousand/km2), the highest in non-agglomeration communes of high population density (PLN 56.5 thousand/km2), while the types of agglomeration communes received intermediate ranking positions.

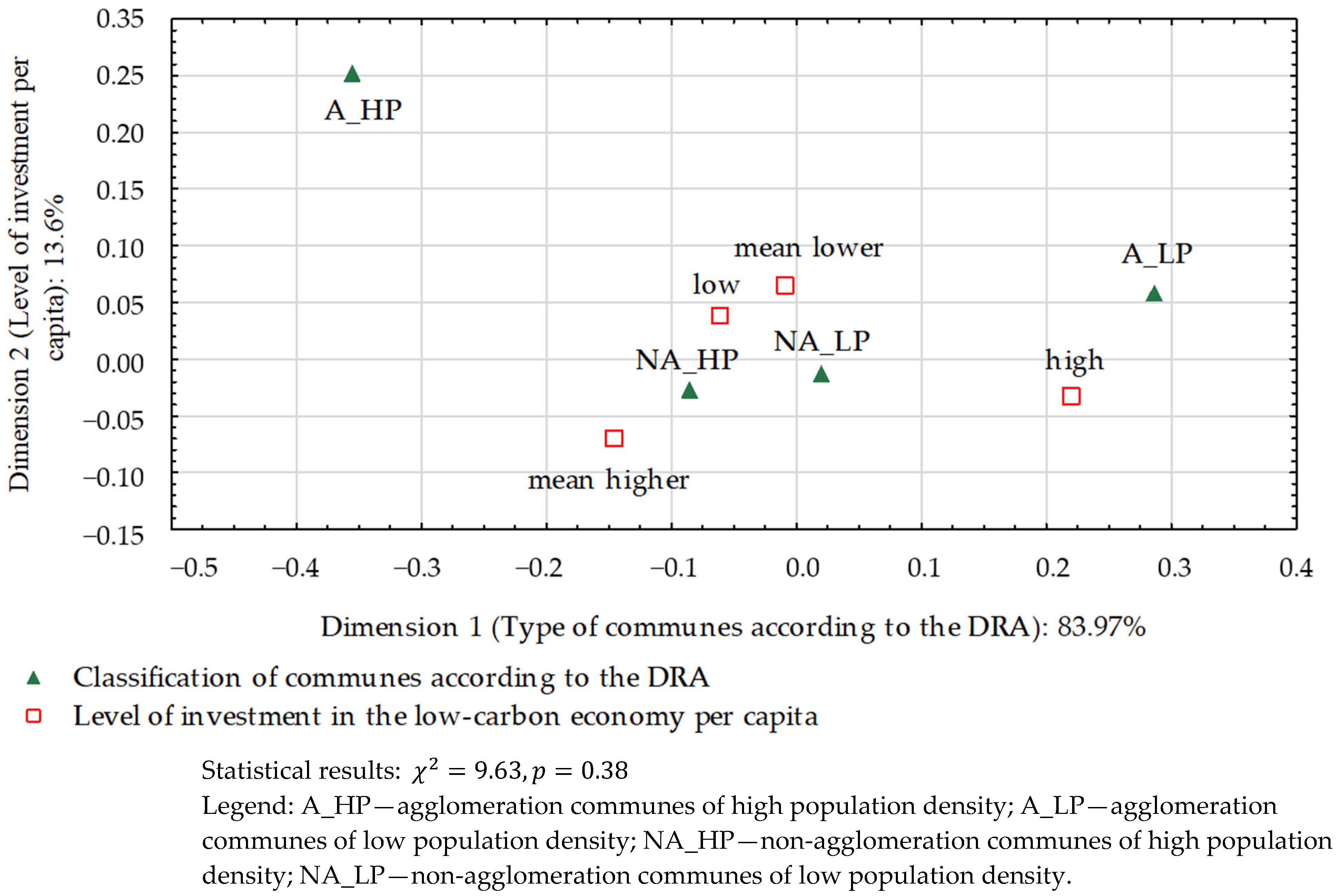

In the next stage of the study, correspondence analysis was applied in order to identify dependencies between the types of rural and urban–rural communes according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas in the Eastern Macroregion, and the level of investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy. This analysis treats the system of categories as points in space and makes it possible to assess both the existence of a relationship (the χ

2 test) and the geometry of relationships (factorial coordinates, cos

2, and representation quality) (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 and

Table 5 and

Table 6).

In the first case, when the value of investments was calculated per capita and then categorized (absence or low, mean lower, mean higher, or high level), no statistically significant relationship was found between the type of communes and the level of their investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy (χ2 = 9.63; p = 0.38). Although the distribution of points suggests a weak trend along Dimension 1, the category high (a positive coordinate) is located closer to agglomeration communes of low density (A_LP: 0.29), while mean higher (a negative coordinate) is closer to agglomeration communes of high population density (A_HP: −0.35). Non-agglomeration communes are located closer to the center (NA_HP: −0.09; NA_LP: 0.02). However, as there is a lack of significance in Chi-squared tests, these relationships need to be treated as weak and non-correlated. The high quality of representation for some categories in Dimension 1 (e.g., high, mean higher, A_LP, and A_HP) needs to be stressed, which means that this dimension properly orders the data in the geometrical sense, but is not reflected in a statistically significant dependence between the variables. The lack of statistical significance for the dependencies between the investigated phenomena is consistent with the earlier results of non-parametric tests for the index of investment in the low-carbon economy per capita (lack of differences between inside an FUA vs. outside FUA, and between the delimitation classes), which suggests that the figures calculated per capita equalize diversification between the types of communes.

In turn, the arrangement of points in the correspondence map (

Figure 7) indicates a clear pattern of correspondence between the types of rural and urban–rural communes classified according to the Delimitation of Rural Areas and the level of investments in the low-carbon economy per unit area (km

2) in the Eastern Macroregion (χ

2 = 50.0;

p < 0.001). Dimension 1 (the principal axis of correspondence) orders categories from lower values of investment on the positive side—where the levels low and mean lower are found, as well as non-agglomeration communes of low population density (NA_LP: x = 0.37)—to higher values on the negative side, with the level high (x = −0.52) and the types of communes with higher population density more strongly linked with FUAs: non-agglomeration communes with a high population density (NA_HP: x = −0.26) and agglomeration communes (A_LP: x = −0.31; A_HP: x = −0.32). This means that territorial units of considerable area and scattered settlement patterns (NA_LP) are relatively more often linked with lesser intensity of investment in the low-carbon economy per 1 km

2, while communes with greater population density, both non-agglomeration and agglomeration types, are associated with higher levels of the discussed investment activity index. Dimension 2 provides, first of all, intragroup differentiation among the agglomeration groups: A_HP (y = 0.40) is closer to the profile mean higher (y = 0.18), while A_LP (y = −0.22) is closer to high (y = −0.60), which may be interpreted as a different manner of spatial concentration of projects in agglomeration communes of varied population density. These results are consistent with the earlier non-parametric tests of the investment activity index calculated per unit area (per 1 km

2) and they support the conclusion that settlement structure and linkages with FUAs are correlated with the intensity of investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy in spatial terms, while in terms of data presented per capita, differences between the delimitation classes were not confirmed statistically.

5. Conclusions

The empirical studies conducted made it possible to assess the level, diversification, and dynamics of changes in investment activity connected to the development of the low-carbon economy co-financed by EU funds in Polish communes, focusing on rural and urban–rural communes in the Eastern Macroregion. The results of these analyses clearly confirm that in the two completed financial frameworks, the policy to support low-carbon projects in Poland shifted from the pilot stage to the phase of extensive popularization. The share of communes which implemented at least one such project increased from 18% in the years 2007–2013 up to 68% in the financial framework 2014–2020, which marked the transition from selective implementation to common implementation of low-carbon measures. This process is promoted by the standardization of implementation procedures, such as the obligation to conduct ex ante and ex post energy audits, application of uniform indicators, and standardization of documentation, which facilitated the replication of routine investment packages such as thermal upgrades of multiple buildings, modernization of street lighting, and local renewable energy systems. As a consequence, these measures have led to more predictable unit costs and stable energy generation and GHG emission levels.

In both investigated financial frameworks, the Eastern Macroregion was distinguished by the greatest participation of communes on a national scale, both in absolute numbers and among rural and urban–rural communes. In that macroregion, a total of 1.4 thousand projects were implemented, accounting for almost ¼ of all projects in Poland, confirming the key role of this macroregion in the implementation of local climate and energy policies. A particularly characteristic aspect was connected with the markedly rural profile of this investment activity. Over 80% of projects in the investigated macroregion were implemented by rural and urban–rural communes, which accounted for almost 50% of the total value (compared to less than 30% on the national scale). This means that the advantage of the Eastern Macroregion did not result solely from its demographic structure, but also from the greater scale and accumulations of these projects. An increase in the average value of a project from approximately PLN 2.3 million (EUR 0.6 million) to PLN 3.1 million (EUR 0.7 million) indicates the transition to more complex and capital-intensive investments, despite the fact that in terms of the total value of projects the region ranked third in Poland.

From the perspective of energy security, the analyzed low-carbon investments play a dual role. On the one hand, improvements in energy efficiency and the deployment of renewable energy sources in rural and urban–rural communes reduce dependence on external energy supplies and increased local generation capacity, which enhances the reliability of energy provision in peripheral areas. On the other hand, the diversification of energy sources and the modernization of local infrastructure mitigate exposure to energy price shocks and contribute to the long-term affordability and stability of energy services for households and local enterprises. In this sense, the high absorption of EU funds in the Eastern Macroregion strengthens not only low-carbon transition, but also the multidimensional energy security of structurally weaker territories.

It needs to be stressed that high investment activity of communes in the Eastern Macroregion was also supported by the dedicated financial instruments allocated to this part of the country. Within the Operational Program Eastern Poland 2014–2020, that region was provided with an additional amount of structural funds allocated not only to support competitiveness and innovation, but also sustainable energy transition. However, it needs to be stressed that these programs were to the greatest extent used by large cities serving the function of subregional growth poles, implementing projects aimed at the development of sustainable municipal transport and low-carbon mobility. Rural and urban–rural communes, despite limited access to such instruments, showed high activity in acquiring funds within the regional operational programs, which confirms their increasing institutional and operational capacity in the implementation of climate and energy policies.

In terms of research methodology, a particularly significant role is played by the sensitivity of formulated conclusions in relation to the selection of a point of reference or benchmark. When presenting the funds acquired for low-carbon investments per capita no statistically significant differences were found between rural and urban–rural communes located within Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) and those outside these areas, which was similar to the relationship between the types of communes classified according to the delimitation methodology. However, a different picture is obtained when analyzing the intensity of allocated outlays per unit area, as communes located within an FUA and those with greater population density (both agglomeration and non-agglomeration communes) reached significantly higher values of investments per 1 km2, while non-agglomeration communes of low population density recorded the lowest levels of this activity. This means that in communes with greater building development density and technological infrastructure, identical investment outlays are reflected in higher intensity in spatial terms, whereas in scattered rural structures this effect was diffused.

Within the Eastern Macroregion, progress in institutional learning could be observed along with the diffusion of good practice, particularly in communes with low population density, where the growth dynamics for the increase in commune participation was greatest. At the same time, a group of communes was identified (from 7% to 13% depending on the type), which in both financial frameworks implemented no projects aimed at the development of the low-carbon economy. These communes, most frequently non-agglomeration communes with low population density and limited income potential, should become a priority for measures in the current financial framework 2021–2027. In turn, in agglomeration communes of high population density, a relatively lower number of projects was recorded, while there was a higher unit value of investments, which indicates implementation of more integrated projects utilizing economies of scale.

High absorption of EU funds in the Eastern Macroregion shows that the institutional solutions used in the years 2014–2020, such as standardization of procedures, common monitoring indexes, and routine investment packages, made it considerably easier for communes to acquire EU funds and implement projects. It would be advisable to maintain and develop similar mechanisms in successive program periods, particularly in relation to peripheral areas, where stability and predictability of support instruments are of key importance for the effectiveness of implemented projects.

In terms of public policies, the recorded results indicate the need for a dual strategy. Firstly, continuation of support for non-agglomeration communes of low population density through umbrella projects (i.e., joint initiatives of local government bodies facilitating implementation of numerous small investments, e.g., renewable energy installations, within one program), joint commissioning, and development of institutional potential. Secondly, it is important to provide further support for agglomeration communes in the execution of more capital-intensive systemic projects. In broader terms, the results of this study undermine the stereotype of Eastern Poland as an area with development deficits. High investment activity aimed at the low-carbon economy on the part of rural and urban–rural communes in that region shows that peripheral regions of Poland may serve as leaders in local energy transition.

Analyses conducted to date concerning the development of the low-carbon economy in Poland focused primarily on urban and metropolitan centers, leading to the marginalization of rural and peripheral regions. This study fills this research gap, showing the Eastern Macroregion as a region of active adaptation to climate policy, in which communes of rural and urban–rural character predominate. The application of two measures for investment intensity, i.e., per capita and per 1 km2, made it possible to separate demographic and spatial effects. This confirms that the assessment of local energy transition and its implications for energy security is highly sensitive to the choice of reference unit, and that spatial concentration of investment may be a more informative indicator than per capita figures in sparsely populated peripheral regions.

The results of empirical studies have made it possible partly to positively verify the research hypothesis, according to which, spatial conditions in the Eastern Macroregion, including location in the border zone as well as location in relation to Functional Urban Areas (within an FUA vs. outside an FUA), significantly diversify the investment activity of rural and urban–rural communes related to the low-carbon economy and co-financed by EU funds. However, this differentiation is manifested primarily in spatial terms (value of investments per 1 km2), where communes located within an FUA and those with greater population density attained significantly higher levels of investment compared to non-agglomeration communes with low population density. In terms of respective figures per capita, this dependence was not statistically significant, which indicates that the effect of the settlement structure and location is manifested only after the spatial concentration of the population and infrastructure have been considered.