Abstract

This study explores the use of remote sensing and machine learning (ML) for early detection of Pyricularia oryzae (rice blast) in ‘Bomba’ rice. Conducted in Spain’s Albufera Natural Park over four seasons (2021–2024), 94 fields were monitored using Sentinel-2 imagery and Topcon Yield Trakk data. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identified key spectral bands (B03, B04, B05, B07, B08, B11) at early stages (35 and 55 DAS). Three ML classifiers—K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs)—were tested to categorize fields by yield-based infection levels. RF achieved the best performance (up to 94% Accuracy), showing high robustness across band combinations and dates. KNN was more input-sensitive, and SVM performed weakest. Integrating multispectral and multitemporal data enhanced accuracy. Overall, RF and remote sensing proved reliable tools for early disease detection, supporting Precision Agriculture and real-time pest management.

1. Introduction

Rice is a staple in the diet of a significant portion of the world’s population, making it a crucial crop for food security. Global rice consumption reached 450 million tons in 2011, increased to 490 million tons in 2020, and is projected to rise to 650 million tons by 2050 [1]. Within the European Union, Spain stands out as one of the leading producers, benefiting from favorable climatic conditions and a long-standing cultivation tradition. In 2020, Spanish rice production accounted for around 26% of the total EU output, equivalent to roughly 739 thousand tons [2]. The Valencian region, in particular, contributes significantly to national production, representing nearly 15% of the total, with an estimated yield of 112 thousand tons distributed across approximately 15,000 hectares [3]. Rice cultivation in L’Albufera de Valencia dates back to the 12th century, marking it as the first region in Spain where rice was systematically grown before its expansion to other parts of the country [4]. Among the traditional varieties, ‘Bomba’ stands out as an emblematic landrace, cultivated since the late 19th century and widely appreciated for its grain quality and adaptability [5].

Throughout history, epidemics of rice crop diseases have resulted in famines in various countries [6]. The primary factor contributing to low rice production is the fungus Pyricularia oryzae Cav. [7]. This disease was first identified in China as ‘rice fever’ in 1637, as noted by Wang et al. [8].

Rice blast is a significant fungal disease that drastically reduces grain weight and the percentage of mature spikelets and grains [9]. This pathogen impacts the entire aerial part of the plant, affecting leaves, stems, the panicle neck, and the panicle itself, which hinders plant development and productivity [10]. The conditions that favor its proliferation include temperatures ranging from 17 °C to 28 °C and relative humidity above 93% [11]. Under optimal conditions, the fungus can destroy the plant within 20 days, potentially leading to total yield losses [12].

P. oryzae is the primary fungal pathogen affecting rice worldwide and is responsible for annual yield losses of up to 30% [13]. In Europe, rice blast is among the most significant diseases affecting yield stability and grain quality, with recurrent outbreaks reported in Mediterranean regions such as Spain and Italy [14]. It is one of the most damaging diseases due to its widespread occurrence and high destructive capability. Some rice varieties, such as ‘Bomba’, are particularly vulnerable to P. oryzae [15]. These varieties can suffer yield losses of up to 65% [16].

Environmental regulations limit the range of specific phytosanitary products available for managing blast infestations, which presents a significant challenge for the rice industry and rice-producing countries [17]. One proposed solution to mitigate blast infestations is genetic improvement. Research by Oliveira-García et al. [18] indicates that various rice varieties, assessed on a scale from 0 to 6 based on their susceptibility to blast, harbor valuable genes for genetic enhancement. This approach is crucial as blast is a global issue. Rice-producing countries, such as the United States, are adopting these techniques, as maintaining genetic improvement for pathogen resistance can help increase food supply. Ignoring this aspect may diminish the overall benefits of rice production [19]. In addition to genetic solutions, innovative technologies are needed to slow the development of pests and prevent the fungus from developing resistance to applied fungicides [13]. Remote sensing is a valuable tool for enhancing crop management and promoting environmental sustainability in agriculture.

Digitalization in agriculture has become increasingly important in recent years, with concepts such as Smart Farming and Precision Agriculture gaining traction [20]. Among the technologies widely used in Precision Agriculture, remote sensing has proven exceptionally valuable for enhancing productivity, monitoring rice crops, and controlling pests [21].

Agricultural precision systems require large volumes of big data for effective decision-making. Analyzing this data can be complex, and machine learning (ML) plays a crucial role in facilitating predictions and decisions with minimal human intervention [22]. In the agricultural industry, ML is employed for various purposes, including crop management, yield prediction, and disease detection. Techniques such as neural networks and machine vision enhance accuracy, although there are still challenges related to automation and cost-effectiveness for farmers [23].

Research conducted by Ramesh and Vydeki in 2019 [24] demonstrated that using ML algorithms for disease detection in rice crops yields highly satisfactory results. Implementing various statistical analyses and classification techniques has improved the identification of infections in the field, providing technicians and farmers with more effective solutions.

To develop environmentally friendly crop management strategies, it is proposed that intrafield studies be conducted on rice blast-susceptible varieties, such as the ‘Bomba’ rice variety. These studies aim to assess the impact of disease on productivity and help establish control measures that align with Integrated Pest Management (IPM) systems.

This work aims to create a blast detection model using ML techniques. This model will utilize satellite image data and statistical methods to classify pixel areas of blast-infested ‘Bomba’ rice fields based on their expected yield predictions. By doing so, we can propose disease control strategies in advance, enabling more efficient management of infestations with fewer inputs and a lower environmental impact. Additionally, these studies will assess the effect of the disease on productivity, further contributing to establishing control measures compatible with IPM systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

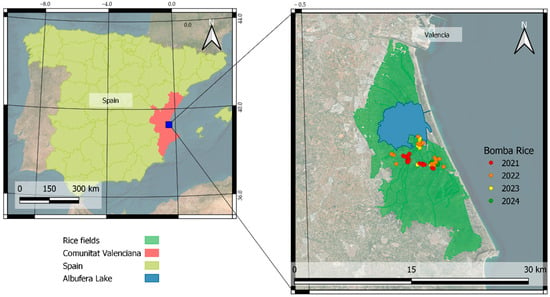

The present study was conducted during the 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 rice-growing seasons in the fields located in the Albufera Natural Park in Valencia (Figure 1), Spain (N 39°16′60″, W 0°22′0.01″). The Albufera lake covers an area of over 211 km2 and is bordered by the Júcar River to the south and the Turia River to the North. This area is characterized by its vast surrounding surface dedicated to rice cultivation, a homogeneous rice plantation zone covering approximately 10 × 20 km2.

Figure 1.

Fields of the seasons 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 of the ‘Bomba’ variety.

The climate is classified as subtropical Mediterranean [25], with hot and dry summers. The soil is sandy loam with a pH of 7.8, 3.0% organic matter, and an electrical conductivity (EC) of 3.2 dS·m−1. The irrigation water comes from the lake and has no salinity restrictions (pH: 7.5; EC: 3.2 dS·m−1). Water management is carried out by flooding the fields to a maximum depth of 15 cm throughout the season, except for three periods when the fields are traditionally dried for treatments such as top-dressing fertilization, herbicides, pesticides, and harvesting [17].

2.2. Experimental Setup

The variety studied was ‘Bomba’, which is characterized by its round and pearly grain and is highly valued in many culinary recipes due to its high starch content, making it particularly interesting for this industry [26]. The plant is distinguished by its typical light green color and poor response to nitrogen fertilization.

A total of 94 fields were monitored, and the number of fields varies from one season to the others, depending on those cultivated with the ‘Bomba’ variety, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of fields and total area (ha) of each season.

The rice was sown on 27 May 2021, on 9 June 2022, on 10 May 2023, and on 29 May 2024 (0 DAS, days after sowing), with a sowing rate of 190 kg∙ha−1. Harvesting for all seasons took place approximately at 110 DAS. The phenological stages were classified following the BBCH scale (Biologische Budesanstalt, Bundessortenamt und Chemische Industrie) [27] (Table 2).

Table 2.

BBCH scale of ‘Bomba’ rice.

2.3. Field Data

2.3.1. Remote Sensing Data

Satellite images were acquired from the Multispectral Instrument (MSI) (MSI, Airbus Defence and Space, Friedrichshafen, Germany) aboard the Sentinel-2A/B constellation, specifically from tile T30SYJ. Sentinel-2 captures images of Earth’s surface in 10 distinct spectral bands. In this research, bands with the highest spatial resolution of 10 m and a lower resolution of 20 m were analyzed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bands and their resolution (m) from Sentinel-2 and each wavelength (nm) resolution and region.

Cloud-free dates were identified using the Copernicus Browser [28], and the corresponding Sentinel-2 images were subsequently downloaded and processed in Google Earth Engine [29] for the period from sowing to harvest for the seasons from 2021 to 2024. Dates were selected to match for all the years, based on days after sowing and crop phenology (Table 2), as detailed in Table 4. The downloaded images provided surface reflectance data.

Table 4.

Dates of downloaded images of all the seasons and days after sowing.

2.3.2. Yield Data

Yield data was obtained using the Yield Trakk system, YieldTrakk YM-3 system (Topcon Agriculture, Livermore, CA, USA) a monitoring software developed by Topcon [30]. This system measures yield in real-time as the harvester operates in the field. The cutting width of the harvester was 7.6 m, providing continuous yield data approximately every meter. Data were processed according to Fita et al. [31].

2.3.3. Determination of Pyricularia oryzae

To evaluate the infestation of Pyricularia oryzae, the following parameters were considered: leaf incidence, leaf severity (percentage of affected area), panicle infestation percentage, neck panicle infection percentage, and the percentage of affected nodes, as defined by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) [32].

Research by Teng and Torres [9], Surin et al. [33], and Katsube and Koshimizu [34] has linked yield loss in rice crops to the incidence of blast. To support this finding, field monitoring of Pyricularia infestation was conducted throughout the crop cycle at 45, 65, 85, and 105 days after sowing (DAS), along with yield estimation by counting and weighing grains from panicles in 18 randomized fields.

A linear regression analysis was performed using data collected at different stages of the crop cycle (45, 65, 85, and 105 DAS). During these sampling periods, the incidence of the disease on leaves, nodes, and panicles was assessed as a percentage, referred to as the Pyricularia Infestation Index (PII). This index was calculated according to the specified model for each DAS, and the correlation coefficient between PII at each DAS and yield was determined (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between yield and the Pyricularia Infestation Index (PII), calculated according to the author’s proposed method at each DAS.

The results showed a progressive increase in Pyricularia incidence throughout the crop cycle, with the highest infestation occurring at 105 DAS. The correlation coefficient obtained between PII and yield at this stage was −0.67, indicating that higher fungal infestation was associated with lower yields and reduced production.

This strong negative correlation demonstrates that in the ‘Bomba’ variety, which is highly susceptible to Pyricularia oryzae, the decrease in yield is directly related to the incidence of the fungus. Consequently, the lower productivity of this variety is attributed to the intensity of Pyricularia infestation, as quantified through the PII values.

2.3.4. Statistics and ML Algorithms

The main objective of this study was to classify rice samples according to the presence or absence of Pyricularia oryzae infection. As a preliminary step, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted to identify the most relevant days after sowing (DAS) and spectral bands contributing to the construction of the classification model.

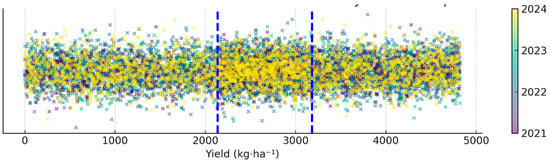

For the definition of the infection categories, yield data from all fields were statistically analyzed and divided into three equal groups based on their distribution. This stratification allowed the establishment of yield thresholds corresponding to three classes:

- Infected: yield < 2135 kg·ha−1;

- Partially infected: 2135 ≤ yield ≤ 3182 kg·ha−1;

- Non-infected: yield > 3182 kg·ha−1.

This data-driven segmentation ensured a balanced representation of each infection level within the dataset, enabling a more robust and objective classification model. This segmentation was based on the empirical quantiles of the yield distribution (33rd and 66th percentiles), ensuring that each class contained approximately one-third of the total observations (Figure A1).

Quantile-based thresholds provide a statistically balanced, non-parametric, and robust separation of yield levels. This approach minimizes bias caused by outliers or unequal class frequencies.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a very useful statistical technique when working with large datasets. Its main purpose is to reduce the dimensionality of a dataset while retaining as much information or variance as possible.

Thus, given a sample of size n with p variables X1, X2, …, Xₚ that are initially correlated, the objective of PCA is to obtain, through normalized linear combinations of these variables, a number k ≤ p of new uncorrelated variables Z1, Z2, …, Zk, known as principal components, which explain most of the variability in the sample. Each principal component is given by the following:

Zj = v1j X1 + v2j X2 + ⋯ +vpj Xp

The coefficients vij of these combinations give an idea of the weight of each variable Xi in the corresponding principal component Zj and, therefore, of their correlation.

Principal components have the advantage of being uncorrelated with each other and can be ordered according to the amount of information they carry, as measured by their variance. The greater the variance, the more information the component contains. Thus, the first component selected is the one with the highest variance, and the last is the one with the lowest.

Therefore, PCA allows for the visualization of data in 2D or 3D to better analyze the possible existence of production groups within the pixel population. Additionally, it helps to understand how the variables—i.e., the reflectance values of the bands—are related, which can be used to identify the bands that best explain the variance in the data and, indirectly, the group membership.

PCA was performed for each of the time points indicated at 35, 55, and 80, taking the reflectance values of the bands listed in Table 3 as variables. To define the band combinations that would be used as variables in the classification models, for each analysis, the bands whose coefficients in the normalized linear combination were greater than 0.4 in the first three principal components were selected. Finally, the bands that appeared consistently across all time points analyzed were selected, regardless of the principal component.

Machine Learning Models

Different ML models were applied to classify pixels into three groups according to yield, previously defined. From the datasets of 2021, 2022, and 2023, 80% of the data was allocated for model training, 20% for testing, and the dataset of 2024 for validation. To avoid bias in data selection, stratified random sampling was applied.

For data classification, three supervised learning algorithms widely used in classification problems were employed: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machines (SVMs). These models were selected for their effectiveness in classifying data with complex features and their applicability in similar classifying studies (Table 6).

Table 6.

Crop diseases studies that use ML models.

KNN: This model was implemented and optimized by evaluating different values of k through cross-validation. This method was selected for its simplicity, ability to capture local patterns, and proven effectiveness in similar studies. It is a proximity-based classification algorithm, where a new datum is assigned to the majority class among its ‘k’ nearest neighbors in the feature space. KNN is a non-parametric method and is considered a ‘lazy learner’ as it does not generate a prior model but classifies based on the structure of the data at query time. The KNN algorithm is considered one of the easiest algorithms to use in ML. It is predominantly used for object classification. It is a very useful algorithm, used to assign missing values and perform data resampling.

SVM: This model was trained using a radial basis kernel to capture non-linear relationships in the data. Hyperparameters were optimized using a grid search with 5-fold cross-validation. It uses hyperplanes to separate data into different classes in an n-dimensional space. This algorithm is especially useful in classification problems with high dimensionality data and when the separation between classes is not linear.

RF: This model was included for its ability to handle non-linear relationships and noisy data while providing insights into variable importance. It is a model based on an ensemble of decision trees that combines individual predictions to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting. It is based on random sampling of data and features, allowing for robust and stable classification.

Performance Evaluation

The confusion matrix is a powerful tool for analyzing the performance of a multiclassifier [44] since it allows us to easily obtain the number of correct and incorrect answers for a classification algorithm. Thus, with a k × k confusion matrix as shown in Table 7, there are k correct classifications and k2-k possible errors.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix of N elements for pairwise comparison.

Particularly for this work,

- , : The different rice varieties;

- : The number of samples that truly belong to class and were predicted as class ;

- : Total number of samples that truly belong to class (i = 1, 2, 3);

- : Total number of samples that were predicted as class (j = 1, 2, 3);

- N: Total number of samples.

In general, for each class , the correct classifications, called True Positives (), is the number of samples correctly classified as belonging to this class, so it is obtained by the following:

On the other hand, there are two kinds of errors:

False Positives (), which are the samples that have been incorrectly classified as belonging to class , that is,

False negatives (), which are the samples that have been incorrectly classified as not belonging to class thus,

Moreover, there is a fourth type of sample called the True Negatives (), which are those that do not actually belong to class . They are calculated by adding the entries of the submatrix that result from eliminating row and column i in the confusion matrix, that is,

Knowing the values of these four types of samples, several commonly used metrics can be generated, as shown in Table 8, to evaluate the performance of the classifier with different evaluation approaches. These metrics must be computed for each class , and then the model metrics will be the average of them.

Table 8.

Definitions and formulas of common Classification Performance Metrics.

2.3.5. Software

Processing of satellite images obtained from Google Earth Engine (GEE) for Sentinel-2 was carried out using QGIS 3.10.14 software [45].

The statistical analyses were performed using the Scikit-learn library in Python [46]. Experiments and model evaluations were conducted in a Python 3.9 environment.

3. Results

3.1. PCA

Prior to the classification study, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of all Sentinel-2 bands for which we have reflectance data was performed.

For yield classification, interest was focused on early cultivation dates (35, 55, and 80 DAS). In addition, it should be noted that the challenge lies in being able to classify the infestation at dates when the farmer can carry out actions in agronomic management and correct or enhance productivity. The purpose of PCA is to transform a set of variables, which are called originals, into a new set of variables called principal components, which are characterized by the fact that they are not correlated among themselves. If the database contains numerous original variables (in this case 10, as many as bands: B02, B03, B04, B05, B06, B07, B08, B08A, B11, B12), what usually happens is that many of these are correlated. Ideally, new variables are sought that are linear combinations of the original variables and that are not correlated, gathering most of the information or variability of the data. The first analysis of interest is presented in Table A2, which shows the correlation between bands at each time point analyzed (35, 55, and 80 DAS) and shows the strong correlation between visible bands (B02, B03, B04) and B05, between Near-Infrared and NIR bands (B06, B07, B08, and B08A), and between the two bands of the SWIR spectrum (B11 and B12).

Subsequently, the screen field was analyzed to analyze the values of the principal components in the analysis, i.e., the variance (variability) explained by each dimension (principal component) in each of the PCAs constructed at 35, 55, and 80 DAS (Table A1). It was observed that only three dimensions would explain more than 90% of the accumulated variance (95.8% at 35 DAS, 93.5% at 55 DAS, and 97.2% at 80 DAS).

The variables with the greatest weight in the first two dimensions of the PCA at 35 and 55 DAS fall mainly on bands B06, B07, B08, B08A, and B11 in one dimension and on bands B02, B03, B04, and B05 in the second dimension (Table A1). At 80 DAS, the weight of the variables did not follow the pattern of the 35 and 55 DAS moments. This weight is more distributed among all bands, with emphasis on bands B06, B11, and B04. This weight contribution analysis could help to decide which bands should be isolated and studied separately in the ML analysis in the next section. With the contribution of the original variables to each dimension of the PCA studied on different dates, one should opt for using bands according to the pattern established for 35 and 55 DAS. That is, respecting a minimum number of bands and that these are mixed between the visible (B02, B03, B04), Near-Infrared (B05, B06, B07), NIR (B08 and B08A), and SWIR (B11 and B12) regions, with special interest in bands B03, B04, B05, B07, B08, and B11. A general criterion is used for the selection of combinations, based on the results obtained from the PCA and the correlations between variables (Table A2). The resulting combinations to apply the ML models are indicated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Combinations used for ML models. Band combinations and each scenario assigned.

3.2. Machine Learning Analysis

Different combinations of spectral bands applied for each model were analyzed, using different dates (DAS: 35, 55, 80) and bands combinations (Table 9). The objective was to evaluate the model performance as a function of the number and type of bands used, considering metrics shown in Table 8. After applying the ML models, the following results were obtained:

KNN: Table 10 presents the results of the KNN model applied to different validation and test scenarios. The results are organized by two dates, 35 and 55 DAS. The model’s Accuracy remains relatively high in most scenarios, both in testing and validation, with values ranging from 0.74 to 0.89, However some differences can be observed among the key metrics reflecting variations in the performance of the model depending on the scenario and the type of evaluation.

Table 10.

Test and validation results (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, Specificity, and F1-Score) of the KNN model to classify Bomba rice in the different scenarios and DAS.

The KNN model shows better performance in scenarios such as Scenario 1, where Accuracy is higher, reaching up to 0.89 in validation for both DAS configurations. This suggests that the model fits better under these conditions. In contrast, Scenario 7 shows the lowest values, especially in Precision metrics, indicating a lower ability of the model to correctly classify in that scenario.

Another relevant aspect is that the differences between the test and validation metrics are minimal, indicating good model stability and generation ability. Specificity metrics are consistently higher than Recall in most scenarios, suggesting that the model is better at correctly identifying negative classes those positive ones.

In conclusion, the KNN model demonstrates solid performance in most scenarios, especially in the first ones. However, performance decreases in scenarios like Scenario 7, which may indicate the need to adjust the model parameters or explore additional data preprocessing methods to improve its classification ability.

SVM: Table 11 presents the results of the SVM model applied in the same scenarios and dates as KNN. In general, the SVM model shows lower performance compared to the KNN model previously discussed. Accuracy ranges from 0.57 to 0.78, with Scenario 1 consistently presenting the best performance, while Scenario 7 shows the lowest values. This indicates that the SVM model may be more sensitive to the characteristics of the data in each scenario.

Table 11.

Test and validation results (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, Specificity, and F1-Score) of the SVM model to classify Bomba rice in the different scenarios and DAS.

The Precision values remain relatively consistent, but the Recall values are notably lower than those of the KNN model, suggesting that the SVM model has more difficulty identifying positive classes correctly. Specificity values are generally higher than Recall values, indicating that the model is better at identifying negative classes than positive ones.

One important observation is that the performance of the model is relatively stable between test and validation phases, which indicates a consistent generalization capability despite the lower overall performance.

In conclusion, the SVM model demonstrates moderate performance across the different scenarios, with notable weakness in scenarios like Scenario 7. This suggests the need for further optimization of the SVM parameters or the exploration of alternative models for improved classification performance.

RF: Table 12 shows the results of the RF model applied with the same configurations as the other models.

Table 12.

Test and validation results (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, Specificity, and F1-Score) of the RF model to classify Bomba rice in the different scenarios and DAS.

The RF model demonstrates consistently high performance across most scenarios, with Accuracy values ranging from 0.83 to 0.94. Scenario 1 shows the highest performances, particularly in the validation phase with 55 DAS, where it achieves an Accuracy of 0.94. This suggests that the RF model is well-suited for the data characteristics in the scenario.

Precision, Recall, and Specificity values are consistently high, reflecting the model’s strong ability to correctly classify both positive and negative classes. Notably, the Recall values, which measure the ability to identify positive classes, are higher in this model compared to SVM and KNN, indicating better sensitivity.

The stability of the model is also evident, with minimal differences between the test and validation results in most scenarios. This suggests a strong generalization capability.

The RF model demonstrates the bests overall performance among the three models analyzed. achieving high Accuracy, Precision, and Recall across various scenarios. This makes it a robust option for classification tasks in this context.

From the comparative analysis of the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) models, clear differences emerge in terms of performance, sensitivity to spectral band combinations, and generalization capacity across different spatial resolutions.

The KNN model showed good overall performance. especially when all available bands within a single DAS or multiresolution combinations were used. Metrics such as Accuracy and F1-Score coefficient improved significantly when integrating information from different scales, with one multiresolution combination reaching an Accuracy of 0.93 and an F1-Score of 0.86. This confirms that KNN benefits from a dataset rich in spectral and spatial diversity.

The SVM model exhibited more modest performance. Its Accuracy and F1-Score were lower across all configurations and showed a sharper drop in sensitivity (Recall) when working with reduced band subsets or individual resolutions. Although it also showed slight improvement in multiresolution combinations, it did not reach the performance levels observed with KNN or RF, suggesting that SVM is less adaptable to data with high spectral and spatial complexity.

Conversely, the RF model consistently achieved the best results. All evaluated combinations surpassed 90% Accuracy, with balanced and high metrics in both sensitivity and Specificity. Multiresolution combinations were especially effective, reaching up to 0.94 Accuracy and over 0.96 Specificity, indicating a highly robust and reliable model. Additionally, RF showed less dependence on the total number of bands, achieving high values even with well-selected reduced combinations.

In conclusion, the results show that RF is the most effective model for this task, followed by KNN, which also performs well when appropriate multispectral combinations are used. SVM, while useful in certain contexts, appears to be a less competitive alternative under the evaluated conditions. Integrating information from different spatial resolutions proves to be a key strategy for enhancing the predictive capability of models, particularly in complex and multivariate environments like the one analyzed.

4. Discussion

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) provided valuable insights for dimensionality reduction and the selection of the most relevant bands for early-stage yield classification. The strong correlations observed among spectral groups highlighted the need to transform the original variables into uncorrelated components. According to the results, three principal components explained over 90% of the variance at all evaluated dates (35, 55, and 80 DAS), indicating that a significant portion of the information contained in the ten original bands can be effectively summarized in a few dimensions. This finding not only improves model interpretability but also suggests that subsequent analyses, such as ML classification, can be optimized using a reduced subset of bands as other studies have shown, from a set with 10 bands to 4 (Band 06, Band 07, Band 08, and Band 8A) [47], transforming the correlated dataset from Sentinel-2 into smaller set of variables representing most of the information of the original dataset. Specifically, Sentinel-2 bands B03, B04, B05, B07, B08, and B11 emerged as the most relevant contributors to the first components at key early dates (35 and 55 DAS), aligning with the objective of identifying agronomically actionable scenarios. This contribution pattern supports the band combinations selected for the different modeling scenarios, prioritizing those that balance representation across the visible, NIR, and SWIR spectral regions while maximizing the predictive information for infection classification.

The results obtained in the ML study provide a robust comparative evaluation of the performance of three supervised classification algorithms (KNN, SVM, and RF) applied to remote sensing data at different dates as other authors have studied in the classification of crop types [48]. In all cases, input configurations based on multiresolution band combinations had a positive impact on model performance, especially on global indicators such as Accuracy and F1-Score. This trend supports the hypothesis that integrating spectral information from different spatial scales provides a richer and more discriminative representation of the observed phenomenon, leading to more accurate classification. By employing machine learning algorithms in rice crops, like the study of Lopez-Andreu et al. [49], we achieved high classification accuracy, highlighting the effectiveness of multispectral data in capturing subtle spectral differences related to crop phenology and agricultural practices

Overall, the RF model demonstrated the best performance. It not only achieved the highest values in global metrics (Accuracy up to 0.94. F1-Score up to 0.94 and Specificity up to 0.96) but also showed notable stability when the number of input bands was reduced. This suggests that RF can efficiently handle spectral redundancy and potential multicollinearity among bands, leveraging its ensemble structure and ability to perform robust feature space partitioning. This behavior aligns with findings in the literature, where RF has consistently outperformed other classifiers in multispectral classification tasks across both natural and urban environments. This model has been used in several similar studies, including that of Liu et al. [50], who achieved the best result (above 91%) compared to other models by applying machine learning-based classification techniques for the early detection of rice cultivation areas using remote sensing data.

The KNN model also showed acceptable performance, particularly when a wide range of bands or multispectral combinations were used. Its results were consistent, with Accuracy exceeding 0.93 in its best configuration. However, its performance was more sensitive to reduced-band setups, with F1-Score significantly dropping in simpler configurations. Therefore, its applicability in more complex scenarios may be limited without a sufficiently representative training set.

In contrast, the SVM model obtained the lowest performance. While theoretically suitable for high-dimensional problems, in this case it exhibited limitations in generalization, especially under configurations with lower spectral diversity. The lower Recall and F1-Score values indicate greater difficulty in correctly identifying positive cases, which could be attributed to its sensitivity to the regularization parameter and kernel selection, two aspects that were not extensively optimized in this study. Additionally, the fact that SVM did not benefit substantially from multiresolution combinations suggests that the model may require more complex tuning to fully exploit multiscale information.

One significant limitation of this analysis is the absence of feature selection or dimensionality reduction techniques such as PCA or variable importance-based approaches. This could further improve model performance, particularly for models that are more sensitive to redundancy, such as SVM.

Overall, the findings confirm that ensemble-based models such as RF, when combined with multispectral and multiresolution data, offer a robust and reliable approach for spectral classification tasks. These results may have significant implications for practical applications such as environmental remote sensing, precision agriculture, or land cover monitoring, where high Accuracy and classification stability are required when working with complex satellite-derived data.

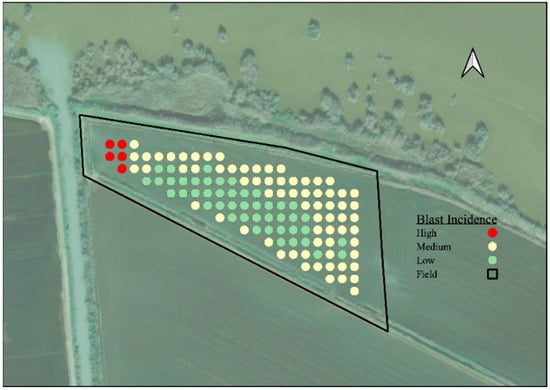

With all the studies carried out, it is possible to prepare a base and the first steps for the development of a digital application in which the early detection of the infestation could be observed in a visual way, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Output of the app in one of the fields of Bomba rice with Blast Incidence levels.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that integrating multitemporal Sentinel-2 imagery with machine learning algorithms creates a reliable and scalable tool for early detection of rice blast disease (Pyricularia oryzae). The results confirm that spectral and temporal information—particularly from the visible, red-edge, and Near-Infrared bands—allows the identification of infection stages before visual symptoms appear, offering a practical advantage for preventive crop management.

Among the models tested, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm showed the highest Accuracy and stability, outperforming both K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) models. It shows its effectiveness for analyzing non-linear and heterogeneous datasets from agricultural environments. The Accuracy achieved with the models was 94% on the validated dataset using vegetation indices and temporal dynamics, thereby improving the model’s performance. So, it clearly shows that remote sensing combined with machine learning enables a scientific understanding of the crop–pathogen system, providing a key tool for decision-making by farmers. Enabling early disease detection facilitates targeted fungicide applications, reduces input costs, and promotes environmentally sustainable rice production.

The accuracy of the models and the possibility of applying these models in other general conditions could form the basis for future research focused on validating models under different climatic conditions and agronomic management practices. At the same time, these models could be applied to similar crops, such as wheat and barley, to be evaluated. Finally, the results of this work could enable a transition to digital, sustainable, and resilient agriculture, capable of reducing production inputs, improving input efficiency and crop productivity, and minimizing environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R., A.U., B.R. and A.S.B.; methodology, A.A.-M., C.R., A.U., B.R. and A.S.B.; software, A.A.-M., R.S., C.R., A.U., B.R. and B.F.; validation, A.A.-M., C.R., A.U., B.R., B.F. and A.S.B.; formal analysis, A.A.-M., R.S., C.R., A.U., B.R., B.F. and A.S.B.; investigation, A.A.-M., R.S., A.U., B.R. and B.F.; resources, C.R., B.F. and A.S.B.; data curation, R.S., C.R., A.U., B.F. and A.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-M., R.S., C.R., B.R. and A.S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-M., C.R., A.U., B.R., B.F. and A.S.B.; visualization, A.A.-M., R.S., A.U., B.F. and A.S.B.; supervision, A.A.-M., R.S., C.R., A.U., B.R., B.F. and A.S.B.; project administration, A.S.B.; funding acquisition, C.R., B.F. and A.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the DETECTORYZA project INNEST/2022/227, INNEST/2022/319 and INNEST/2022/361 Regional Operational Programme, FEDER Comunitat Valenciana de la Innovació, Generalitat Valenciana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Variability explained by each dimension (principal component) in PCA at 35, 55, and 80 DAS. The blue dashed lines delineate the three equivalent groups used for the classification of infection categories.

Table A1.

Variability explained by each dimension (principal component) in PCA at 35, 55, 80 DAS.

Table A1.

Variability explained by each dimension (principal component) in PCA at 35, 55, 80 DAS.

| 35 DAS | DIM.1 | DIM.2 | DIM.3 |

| B02 | 2.73 | 22.15 | 25.34 |

| B03 | 0.01 | 30.23 | 8.78 |

| B04 | 6.32 | 15.53 | 21.15 |

| B05 | 0.04 | 27.03 | 31.65 |

| B06 | 14.96 | 1.96 | 1.33 |

| B07 | 15.86 | 0.33 | 0.18 |

| B08 | 15.61 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

| B8A | 15.84 | 0.33 | 0.49 |

| B11 | 15.12 | 0.50 | 5.85 |

| B12 | 13.46 | 1.64 | 5.18 |

| 55 DAS | DIM.1 | DIM.2 | DIM.3 |

| B02 | 17.68 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| B03 | 17.76 | 0.35 | 1.65 |

| B04 | 17.67 | 0.00 | 2.44 |

| B05 | 18.03 | 0.35 | 0.83 |

| B06 | 0.10 | 24.27 | 10.90 |

| B07 | 8.30 | 16.51 | 0.66 |

| B08 | 8.24 | 16.54 | 0.20 |

| B8A | 0.18 | 4.64 | 82.70 |

| B11 | 2.72 | 24.64 | 0.00 |

| B12 | 3.91 | 12.48 | 0.57 |

| 80 DAS | DIM.1 | DIM.2 | DIM.3 |

| B02 | 9.60 | 9.90 | 9.42 |

| B03 | 10.95 | 7.61 | 3.69 |

| B04 | 4.85 | 25.11 | 5.56 |

| B05 | 10.69 | 7.87 | 0.05 |

| B06 | 12.53 | 3.87 | 1.23 |

| B07 | 9.52 | 13.44 | 2.81 |

| B08 | 8.54 | 15.76 | 3.16 |

| B8A | 8.91 | 15.14 | 2.88 |

| B11 | 12.74 | 0.13 | 26.21 |

| B12 | 11.64 | 1.16 | 44.98 |

Table A2.

Correlation between bands at each time (35, 55, and 80 DAS).

Table A2.

Correlation between bands at each time (35, 55, and 80 DAS).

| 35 DAS | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B08A | B11 | B12 |

| B02 | 1 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.63 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.31 | −0.3 | −0.26 | −0.16 |

| B03 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| B04 | 1 | 0.55 | −0.44 | −0.52 | −0.53 | −0.51 | −0.46 | −0.37 | ||

| B05 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.13 | |||

| B06 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.87 | ||||

| B07 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.87 | |||||

| B08 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.86 | ||||||

| B08A | 1 | 0.94 | 0.87 | |||||||

| B11 | 1 | 0.97 | ||||||||

| B12 | 1 | |||||||||

| 55 DAS | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B08A | B11 | B12 |

| B02 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.02 | −0.54 | −0.55 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.66 |

| B03 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.12 | −0.53 | −0.55 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.66 | |

| B04 | 1 | 0.88 | −0.14 | −0.60 | −0.60 | −0.03 | 0.36 | 0.67 | ||

| B05 | 1 | 0.09 | −0.56 | −0.55 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.71 | |||

| B06 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.67 | −0.12 | 0.69 | 0.40 | ||||

| B07 | 1 | 0.97 | −0.28 | 0.38 | −0.03 | |||||

| B08 | 1 | −0.29 | 0.40 | 0.01 | ||||||

| B08A | 1 | −0.27 | −0.19 | |||||||

| B11 | 1 | 0.89 | ||||||||

| B12 | 1 | |||||||||

| 80 DAS | B02 | B03 | B04 | B05 | B06 | B07 | B08 | B08A | B11 | B12 |

| B02 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| B03 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 0.83 | |

| B04 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.62 | ||

| B05 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.79 | 0.85 | |||

| B06 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.78 | ||||

| B07 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.79 | 0.63 | |||||

| B08 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.58 | ||||||

| B08A | 1 | 0.77 | 0.60 | |||||||

| B11 | 1 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| B12 | 1 |

References

- Lim, S.H. Floating rice fields, the quest for solutions to combat drought, floods and rising sea levels. In WCFS2020: Proceedings of the Second World Conference on Floating Solutions, Rotterdam; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#home (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- MAPA. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/default.aspx (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Ferrando, J.S.; Jambrino, B.D. El parc natural de l’Albufera. Un paisaje cultural cargado de historia. PH Bol. Inst. Andal. Patrim. Hist. 2014, 22, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, R. El Departamento del Arroz del IVIA. Comunitat Valencia. Agrar. 2003, 21, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, S.Y. The great Bengal famine. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1973, 11, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thon, M.R.; Pan, H.; Diener, S.; Papalas, J.; Taro, T.; Mitchell, T.K.; Dean, R.A. The role of transposable element clusters in genome evolution and loss of synteny in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lee, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Bianco, T.; Jia, Y. Current advances on genetic resistance to rice blast disease. Rice-Germplasm Genet. Improv. 2014, 23, 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, P.S.; Torres, C.Q.; Nuque, F.L.; Calvera, S.B. Current knowledge on crop losses in tropical rice. In Crop Loss Assessment in Rice; International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines, 1990; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pla, E.; Català, M.M.; Tomàs, N. Ficha número 9: La Pyriculariosis del arroz. In Fichas Técnicas IRTA de las Mejores Prácticas de Cultivo del Arroz; IRTA Amposta: Amposta, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Delgado, F. Caracterización Agronómica y Monitoreo de la Pyriculariosis de una Selección de Variedades de Arroz. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain, 8 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kihoro, J.; Bosco, N.J.; Murage, H.; Ateka, E.; Makihara, D. Investigating the impact of rice blast disease on the livelihood of local farmers in the greater Mwea region of Kenya. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunova, A.; Palazzolo, L.; Forlani, F.; Catinella, G.; Musso, L.; Cortesi, P.; Dallavalle, S. Structural investigation and molecular modeling studies of strobilurin-based fungicides active against the rice blast pathogen Pyricularia oryzae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsantonis, D.; Kadoglidou, K.; Dramalis, C.; Puigdollers, P. Rice blast forecasting models and their practical value: A review. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2017, 56, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Català, M.; Almacellas, J.; Marín, J.P.; Tomàs, N.; Martínez Eixarch, M.; Pla Mayor, E. Reacción a Pyricularia grisea de las variedades más importantes de arroz cultivadas en el Delta del Ebro durante el período 2000–2008. Phytoma España Rev. Prof. Sanid. Veg. 2010, 220, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhara, M.V.; Gururaj, S.; Naik, M.K.; Nagaraju, P. Screening of rice genotypes against rice blast caused by Pyricularia oryzae Cavara. Karnatak J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 21, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de Barreda, D.; Pardo, G.; Osca, J.M.; Catala-Forner, M.; Consola, S.; Garnica, I.; López-Martínez, N.; Palmerín, J.A.; Osuna, M.D. An overview of rice cultivation in Spain and the management of herbicide-resistant weeds. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Garcia, E.; Budot, B.O.; Manangkil, J.; Dala Lana, F.; Angira, B.; Famoso, A.; Jia, Y. An efficient method for screening rice breeding lines against races of Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalley, L.; Tsiboe, F.; Durand-Morat, A.; Shew, A.; Thoma, G. Economic and environmental impact of rice blast pathogen (Magnaporthe oryzae) alleviation in the United States. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, M.V.; Heil, R.; Bittner, L. Big data on a farm—Smart farming. In Big Data Context; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginestet, P.C. Estimación de Rendimientos y Contenido de Proteína en el Cultivo de Trigo Candeal Mediante la Utilización de Sensores Remotos; Curso Internacional de Agricultura de Precisión: Manfredi, Argentina, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alzubi, J.; Nayyar, A.; Kumar, A. ML from theory to algorithms: An overview. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1142, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. ML in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, S.; Vydeki, D. Application of ML in detection of blast disease in South Indian rice crops. J. Phytol. 2019, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, F.; Ruiz Beltrán, L. Agroclimatología de España; INIA: Cuaderno, Spain, 1997; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Franch, B.; San Bautista, A.; Fita, D.; Rubio, C.; Tarrazó-Serrano, D.; Sánchez, A.; Uris, A. Within-field rice yield estimation based on Sentinel-2 satellite data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancashire, P.D.; Bleiholder, H.; Boom, T.V.D.; Langelüddeke, P.; Stauss, R.; Weber, E.; Witzenberger, A. A uniform decimal code for growth stages of crops and weeds. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1991, 119, 561–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Space Agency. Copernicus Browser [Software]. 2024. Available online: https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcon. Available online: https://www.topconpositioning.com/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Fita, D.; Rubio, C.; Franch, B.; Castiñeira-Ibáñez, S.; Tarrazó-Serrano, D.; San Bautista, A. Improving harvester yield maps postprocessing leveraging remote sensing data in rice crop. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SES; IRRI. Standard Evaluation System for Rice; International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Surin, A.; Arunyanart, P.; Dhitikiattipong, R.; Rojanahusdin, W.; Disthaporn, S.; Soontrajarn, K. Rice yield loss to sheath rot. Int. Rice Res. Newsl. 1988, 13, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Katsube, T.; Koshimizu, Y. Influence of blast disease on harvests in rice plant. I. Effect of panicle infection on yield components and quality. Bull. Tohoku Natl. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1970, 39, 155–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnenkamp, D.; Behmann, J.; Mahlein, A.K. In-field detection of yellow rust in wheat on the ground canopy and UAV scale. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, M.; Ashourloo, D.; Aghighi, H.; Radiom, S.; Alimohammadi, A. Wheat leaf rust detection at canopy scale under different LAI levels using machine learning techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Lizarazo, I.; Prieto, F.; Angulo-Morales, V. Assessment of potato late blight from UAV-based multispectral imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Liu, C.; Coombes, M.; Hu, X.; Wu, W.; Song, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhu, Y. Wheat yellow rust monitoring by learning from multispectral UAV aerial imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván Fraile, J. Machine Learning for Remote Sensing of Xylella fastidiosa. Master’s Thesis, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Palma, Spain, 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11201/156941 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Waters, E.K.; Chen, C.-M.; Rahimi Azghadi, M. Machine Learning for asymptomatic ratoon stunting disease detection with freely available satellite-based multispectral imaging. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.03141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzia, V.; Khaliq, A.; Chiaberge, M. Improvement in land cover and crop classification based on temporal features learning from Sentinel-2 data using recurrent-convolutional neural network (R-CNN). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Yu, Q.; Xiang, L.; Zeng, F.; Dong, J.; Xu, O.; Zhang, J. Integrating UAV and high-resolution satellite remote sensing for multi-scale rice disease monitoring. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 234, 110287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapu, I.; Chandel, A.; Sie, E.K.; Okello, D.K.; Oteng-Frimpong, R.; Okello, R.C.O.; Balota, M. Comparing regression and classification models to estimate leaf spot disease in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for implementation in breeding selection. Agronomy 2024, 14, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A. Classification assessments methods. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2020, 17, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Project. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/en/site/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Python, version 3.11; Python Software Foundation: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.python.org (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Rana, V.K.; Suryanarayana, T.M.V. Performance evaluation of MLE, RF and SVM classification algorithms for watershed scale land use/land cover mapping using Sentinel-2 bands. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2020, 19, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maponya, M.G.; Van Niekerk, A.; Mashimbye, Z.E. Pre-harvest classification of crop types using a Sentinel-2 time-series and machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Andreu, F.J.; Erena, M.; Domínguez-Gómez, J.A.; López-Morales, J.A. Sentinel-2 images and machine learning as tools for monitoring the Common Agricultural Policy: Calasparra rice as a case study. Agronomy 2021, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, D.; Yang, W. An algorithm for early rice area mapping from satellite remote sensing data in southwestern Guangdong in China based on feature optimization and random forest. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 72, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).