Abstract

In major pineapple-producing regions of China, conventional manual harvesting is challenged by high labor intensity and cost. Existing mechanical harvesters, still largely in the research and development stage, often suffer from low efficiency and high susceptibility to fruit damage, failing to meet large-scale production demands. This study focuses on the Tainung 16 pineapple, determining that the tensile force required to separate the fruit stem at the calyx ranges from 100.42 N to 165.38 N. Drawing on the biomimetic principles of manual stem-breaking, we designed a harvesting device featuring a curved fixed baffle and a rotating unit. Using theoretical analysis and ADAMS simulation, a mechanical model of the device–stem interaction was established to simulate the force application, bending, and separation processes. This led to the identification of optimal operational parameters: a forward speed of 1.5 m/s, a harvesting unit rotational speed of 37 r/min, and a motion trajectory parameter of 1.3. Field tests demonstrated an average harvesting success rate of 81.23% with a fruit damage rate as low as 9.35%. The device thus effectively addresses the critical industry challenges of low efficiency and high damage. This work provides a direct technical reference and theoretical foundation for the engineering development, refinement, and standardized field operation of pineapple harvesters, facilitating the transition to mechanized large-scale harvesting.

1. Introduction

As one of the world’s four major tropical fruits, pineapple originated in the Amazon River basin. Introduced to China in the 16th century, it has since spread widely across tropical regions [1,2,3]. China ranks among the top five pineapple producers globally, with primary cultivation zones concentrated in Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. Guangdong and Hainan together account for over 70% of the nation’s total planting area and output [4]. However, due to the spiny crown and leaf margins, highly seasonal harvesting periods, and labor-intensive nature of pineapple picking, coupled with labor shortages and the continuous expansion of agricultural industrialization, traditional manual harvesting methods have become increasingly unsuitable for large-scale, intensive production demands [5,6]. Therefore, developing efficient, low-damage pineapple harvesting equipment tailored to major production areas is of great practical significance.

Mechanized harvesting is a key approach to enhancing operational efficiency and reducing production costs [7,8,9]. To alleviate labor intensity and improve harvesting efficiency [10,11], researchers worldwide have conducted relevant studies [12]. Early on, O’Brien et al. [13] proposed an automated pineapple harvester that combined chemical ripening with mechanical force to detach the fruit. Plebe and Grasso [14] applied machine vision technology to locate spherical fruit, providing target recognition solutions for automated harvesting [15]. Current primary pineapple harvesting technologies include handheld harvesting devices, harvesting robots, and vision-assisted harvesting systems. Handheld devices, designed based on pineapple biology, employ various actions and structures such as gripping, shearing, and stem-breaking, achieving harvesting rates and success rates exceeding 80% [16,17,18] while significantly reducing fruit loss and missed harvest rates. To reduce the labor intensity of manually operating robotic arms, control systems and power-assisted mechanical devices have been progressively integrated into mechanical structures. Wang et al. [19] designed a manually assisted portable harvesting robotic arm that uses a screw-nut drive system to control claw closure for pineapple gripping. However, this device did not fundamentally improve field harvesting efficiency. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of machine vision technology, numerous scholars have developed monocular vision-based field pineapple fruit recognition systems and automated harvesting manipulators [20,21,22]. Image processing methods and algorithm optimization enable precise localization and segmentation of pineapples [23,24,25]. Although these systems reduce manual labor intensity, the prolonged processing and execution times result in low efficiency, failing to meet the demands of large-scale production. Furthermore, existing devices exhibit limited adaptability to pineapple plants of varying morphologies [26]. The stability and efficiency of mechanical structures and motion control systems require further optimization, while issues such as low fruit harvesting rates and high damage rates remain unresolved.

To address the aforementioned challenges, aiming at the problems of poor adaptability, low efficiency, and high damage rate of existing pineapple harvesting equipment, this study developed a biomimetic pineapple harvesting device tailored for large-scale mechanized field harvesting. Integrating pineapple’s geometric morphology and biological characteristics—such as its waxy, hard rind—the design emulates manual stem-breaking motions based on bionic principles. This device mimics the manual breaking torque through the coordinated motion of a curved fixed baffle and rotating harvesting unit, adapting to pineapples of varying shapes to achieve efficient, precise, and low-damage harvesting. Kinematic and dynamic simulations of the device-plant interaction were conducted using Adams 2018 software to determine the optimal design, which was then validated through field experiment. This research addresses the core challenges of low harvesting efficiency and high damage rates in major pineapple-producing regions, providing theoretical guidance and technical support for upgrading pineapple harvesting machinery.

2. Pineapple Agronomic Parameters and Mechanical Properties

2.1. Agronomic Parameters and Physical Characteristics of Pineapple Cultivation

The typical planting density for pineapples in the field is 45,000–60,000 plants ha−1. When the slope of the planting area exceeds 20°, the planting configuration can be adjusted based on the actual terrain conditions. To maximize land resource efficiency and provide plants with ample space, sunlight, and nutrient supply, pineapple cultivation widely adopts a wide-narrow row planting pattern. This method not only significantly improves land utilization but also effectively boosts pineapple yields. According to standardized planting technical specifications, the core agronomic parameters are as follows: plant spacing of 350–450 mm and row spacing of 400–500 mm.

The physical and mechanical properties of pineapple fruit serve as the core basis for developing non-destructive harvesting techniques [27]. According to the pineapple maturity standard (FFV-49) established by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), which is a widely recognized reference for tropical fruit maturity classification globally. Pineapple maturity is classified into five stages based on peel color: from C0 (entirely green peel) to C4 (entirely yellow peel), with the proportion of yellow peel gradually increasing from 0% to 100%. Research confirms that pineapples at the C1 stage (0–25% yellow skin) and C2 stage (25–50% yellow skin) exhibit optimal transport tolerance and damage resistance, these two stages represent the ideal maturity range for harvesting and post-harvest distribution [28].

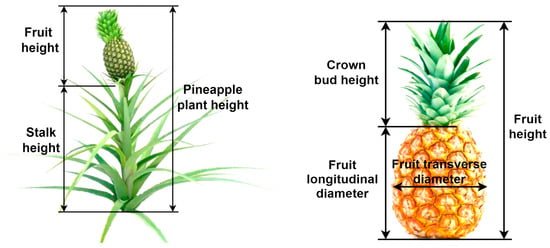

To obtain fundamental physical parameters, this study selected Tainung 16 pineapples as the research subject. At the pineapple experimental base of the South Subtropical Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences in Zhanjiang, Guangdong, random sampling was employed to measure key dimensional parameters of 50 pineapple fruits and plants, all of which were at C1–C2 maturity stages (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the measurement of dimensional parameters of pineapple.

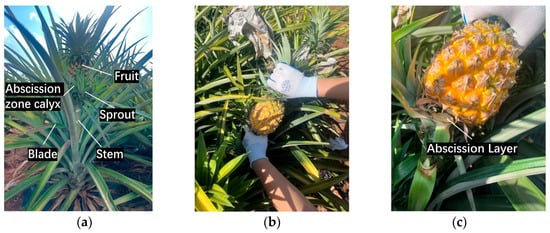

2.2. Analysis of Biomimetic Principles in Pineapple Harvesting Processes

Pineapple plants exhibit tall and dense morphological characteristics, with their leaves forming natural mechanical obstacles during harvesting operations. Structurally, pineapple plants primarily consist of crown buds, fruits, leaves, and stems (Figure 2a). Investigating manual pineapple harvesting techniques not only aids in elucidating the optimal mechanism for separating fruit from the plant [29] but also provides crucial insights for optimizing the design of biomimetic harvesting devices. In the practical operation of manually harvesting pineapples, the operator typically grasps the crown bud with one hand while stabilizing the stem with the other (Figure 2b). By simultaneously applying bending and pulling forces, shear stress is generated in the calyx region, causing the fruit to naturally separate from the stem and completing the harvesting process.

Figure 2.

Schematic of pineapple fruit separated from plant. (a) Structure of the pineapple. (b) Manual harvesting process. (c) Pineapple abscission layer.

From the perspective of plant structure and function, the calyx serves as the transitional junction between the base of the pineapple fruit and the stem. Its interior is rich in fibrous tissue, providing mechanical support for the fruit (Figure 2c) [30]. As the fruit matures, cells in the abscission zone gradually degenerate, with pectin and cellulose in the cell walls degraded to form a naturally cleavable fracture surface [31]. When a bending moment is applied to the calyx, the fruit bends along the stem axis: one side of the calyx is subjected to compressive stress, while the other side experiences tensile stress, weakening its mechanical support. Subsequently, the applied shear stress breaks the cell wall connections in the abscission zone, ultimately separating the fruit from the plant.

Based on the aforementioned biomimetic mechanism of manual harvesting, the pineapple harvesting device must apply an appropriate torque to the abscission layer at the calyx to simulate the separation effect achieved by manual operation, thereby enabling the natural separation of the fruit from the plant. Therefore, accurately determining the tensile force required to break and separate the fruit from the stem at the pineapple calyx is a fundamental prerequisite for the design and optimization of the harvesting device in this study.

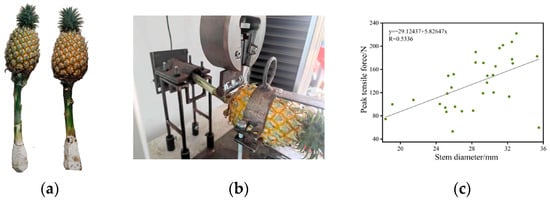

2.3. Mechanical Properties of Pineapple Calyx

To precisely obtain the mechanical parameters required for the fracture of the abscission layer at the calyx, this study conducted mechanical property tests on pineapple calyces. These tests not only provide data support for clarifying the mechanical characteristics of the fruit-stem connection structure but also offer scientific basis for optimizing harvesting methods and reducing fruit damage [32]. Based on previous studies examining the mechanical properties of fruit-stem junctions, a sample size of 30 pineapple specimens was selected [30]. The Tainung 16 cultivar was selected for the experiment, which met the criteria of uniform size, being pest- and disease-free, and having maturity levels of C1 or C2. During sampling, the plant roots were severed manually using a sickle, with approximately 300 mm of stem retained (Figure 3a) to match the fixture size of the testing machine and ensure stable clamping during the test. All experiments were completed on the same day as sampling to minimize the influence of variables such as water loss and fluctuations in environmental temperature and humidity [11]. The testing equipment utilized a WDW-50E microcomputer-controlled electronic universal testing machine (manufactured by Jinan Hengke Test Equipment Co., Ltd., Jinan City, China), with a test speed range of 0.05–500 mm·min−1 and a test force range of 100–5000 N. A 250 N force sensor was selected, and the loading rate was set to 10 mm/min. During clamping, one end of the pineapple was secured in a custom-made holding device. Before testing, the pineapple was placed horizontally with its stem axis perpendicular to the testing machine’s indenter (Figure 3b). Complete data were recorded synchronously throughout the testing process.

Figure 3.

Mechanical properties test. (a) Test samples. (b) Test process. (c) Test results.

Test results indicate that the tensile force range required to separate the fruit from the stem at the calyx of No. Tainung 16 Pineapples is 100.42–165.38 N. Further analysis reveals that the scatter plot and fitting results in Figure 3c indicate a positive correlation between stem diameter and peak tensile force. Specifically, as stem diameter increases, the required peak tensile force gradually rises. This primarily stems from larger stems possessing higher internal fiber content and greater tensile strength. However, some data points deviate from the fitted line, suggesting that unquantified factors may contribute to fluctuations in mechanical properties, including variations in environmental temperature and humidity, as well as inter-sample differences in abscission zone cell degradation degree, cell wall strength, and fiber composition.

In summary, the critical breaking force of pineapples measured in this test was 100.42 N, with a maximum load of 165.38 N. These values provide an evaluation basis for subsequent simulations and parameter screening, ensuring that the selected working parameter combinations align with the mechanical properties of the fruit stem junction and laying the foundation for efficient, low-damage harvesting.

3. Structure and Working Principle of Pineapple Harvesting Device

3.1. Structure of Pineapple Harvesting Device

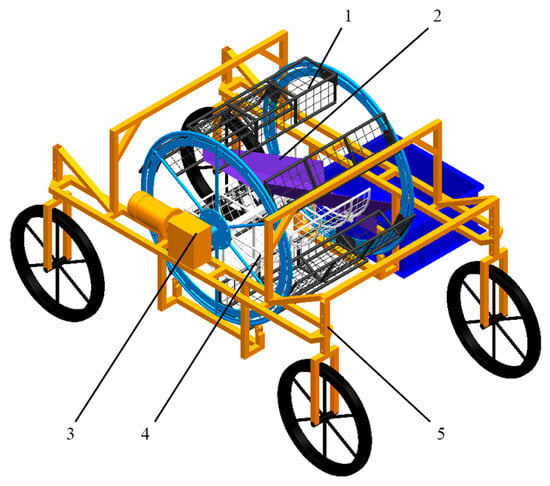

To validate the feasibility of a biomimetic harvesting device and achieve the objectives of high-efficiency harvesting with minimal damage, this study innovatively designed a biomimetic pineapple harvesting device. The device primarily consists of a curved fixed baffle, rotating harvesting units, a conveying slide plate, a power mechanism, and a lifting frame (Figure 4). Key component parameters are as follows: The overall device adopts a cylindrical drum structure with a drum radius of 500 mm and width of 800 mm. The curved fixed baffle adopts a semi-cylindrical design and is positioned inside the harvesting device, with a radius of 300 mm and width of 750 mm, serving to position and guide fruit orientation. Six rotating harvesting units are employed, each unit an L-shaped structure with an overall width of 780 mm, a tangential length of 200 mm, and an axial length of 150 mm. The lifting frame offers a height adjustment range of 300–700 mm. This range allows the harvesting unit to be accurately aligned with the calyx region of pineapple plants (height: 500–700 mm), ensuring operational adaptability across different growth stages.

Figure 4.

Biomimetic pineapple harvesting device. 1. Rotating harvesting unit. 2. A conveying slide plate. 3. Power mechanism. 4. Curved fixed baffle. 5. Lifting frame.

3.2. The Principle of Pineapple Harvesting

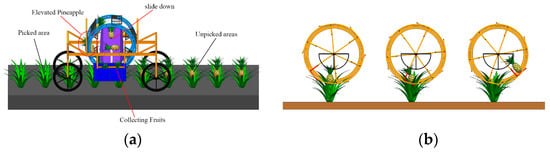

The complete operational process of the harvesting device is illustrated in Figure 5a, with its working principle shown in Figure 5b. The process can be divided into two main stages: pre-operation calibration and field harvesting. Its core functionality relies on the coordinated action of curved fixed baffles and a rotating harvesting unit to achieve automated, low-damage harvesting.

Figure 5.

Harvesting process and principles. (a) harvesting device workflow diagram. (b) schematic diagram of working principle.

Pre-operation Calibration: To ensure operational adaptability and precision, adjust the lifting frame height based on the actual height range of pineapple plants in the field, aligning the feeding height range of the harvesting device with the plant’s calyx region. Simultaneously, preset the machine’s travelling speed and the harvesting device’s rotational speed to appropriate initial values.

Field harvesting operation stage: This stage achieves an integrated process of feeding, separation, conveying, and collection. The first stage is fruit feeding: The harvesting device moves at a constant travelling speed along the pineapple rows. When a pineapple enters the harvesting zone, the curved fixed baffle is brought into contact with the fruit at a constant speed as the device moves forward. Upon contact, it creates a blocking effect, limiting relative displacement between the fruit and the harvesting device. As the fixed curved baffle continues moving forward at a constant speed, the process enters the plant separation stage. Under this blocking force, the rotating harvesting unit simultaneously contacts and acts on the pineapple stem. It rotates at a constant speed tangentially perpendicular to the curved fixed baffle. This rotational speed not only adapts to the complex morphology of the pineapple stem but also interacts with the constant linear velocity of the curved fixed baffle to generate a breaking torque on the stem. This torque is crucial for achieving stem fracture. Designed based on the mechanical principles of stem fracture, it ensures low-damage fruit separation with minimal force while meeting the required breaking tension. Finally, the fruit conveyance and collection stage: After separation, the pineapples move with the rotating harvesting unit to the upper part of the drum. Under gravity, they detach from the unit and fall onto the conveying slide. They then slide down the slide at a preset angle into the fruit collection bin, completing the entire harvesting process.

Throughout the harvesting process, adjusting the picking force and application angle is achieved by controlling the travelling speed of the harvesting device, the rotational speed of the rotating harvesting unit, and the coordination between their movements. This approach not only minimizes damage to the pineapple fruit’s skin and internal tissue during harvesting but also prevents mechanical interference with surrounding unharvested plants during operation. Ultimately, this ensures both efficiency and safety in large-scale field harvesting.

3.3. Force Analysis of Pineapple Harvesting

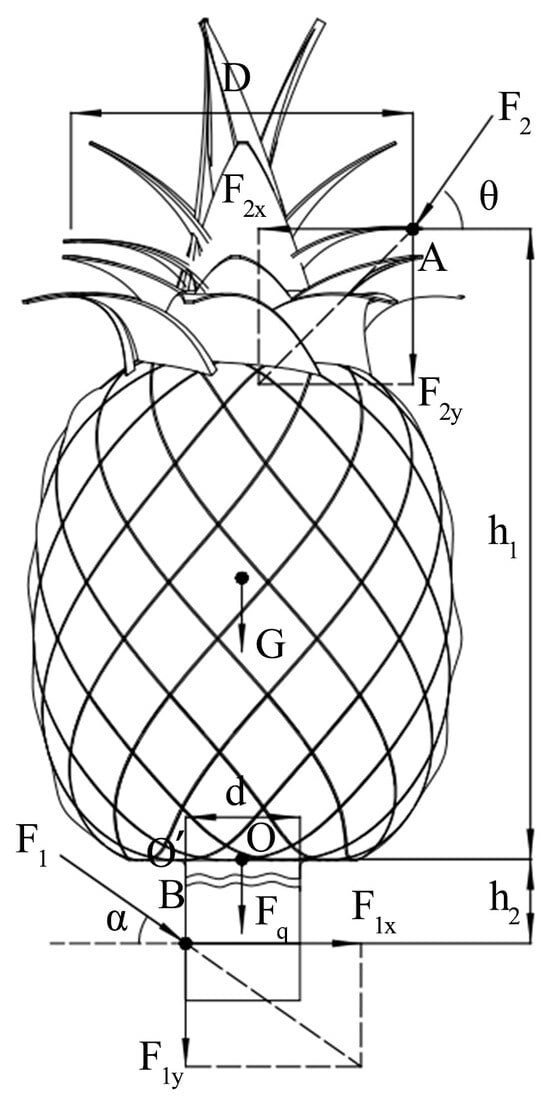

A force analysis of the pineapple harvesting process reveals that during picking, the pineapple plant primarily experiences two opposing forces originating from the rotating harvesting unit and the curved fixed baffle. The specific force analysis is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Force analysis.

When harvesting pineapples, the force exerted by the curved fixed baffle acts on point of the pineapple fruit, while the force exerted by the rotating harvesting unit acts on point of the pineapple stem. The pineapple fruit will rotate about point , generating an external torque on point . To ensure smooth harvesting of the pineapple fruit, the following relationship must be satisfied:

Because of

Then

The internal moment of the pineapple and stem is expressed as:

where F1—Force exerted by the rotating harvesting unit on pineapple stems, N;

F2—Force exerted by the curved fixed baffle on pineapple fruit, N;

h1—Distance from F2 to the pineapple calyx, mm;

h2—Distance from F1 to the pineapple calyx, mm;

d—Pineapple stem diameter, mm;

G—Gravity of pineapple Fruit, N;

Fq—The bonding strength between pineapple fruit and stem, N;

D—Diameter of the pineapple fruit at the point of application, mm.

It can be deduced from Equations (4) and (5) that: When ≥ , the pineapple fruit separates from the stem, completing the harvesting of the pineapple fruit. Based on this constraint, the key parameters affecting harvesting efficiency can be further categorized into two types, providing a clear direction for subsequent device design and simulation optimization: h1, h1, d, and G are determined by the agronomic and physical characteristics of the pineapple itself and are non-adjustable fixed parameters in the design and optimization of the harvesting device. In contrast, F1 and F2 are core adjustable variables directly related to the structural of the rotating harvesting unit and the curved fixed baffle, as well as the operational parameters of the device. Therefore, subsequent research should focus on conducting simulation studies centered on the two core adjustable variables F1 and F2.

4. Key Component Design and Analysis

4.1. Motion Analysis of the Rotating Harvesting Unit

The motion of the rotating harvesting unit consists of two key coupled elements: the overall forward movement of the harvesting device and the circular motion of the rotating harvesting unit around its rotational axis. Together, these determine the point of contact between the harvesting unit and the pineapple stem, as well as the applied force effect. A Cartesian coordinate system is established with the center of the rotating harvesting unit’s axis as the origin. The forward direction of the harvesting device is defined along the x-axis. The rotating harvesting unit moves with horizontal velocity and angular velocity . After time t, the trajectory equation for any point on the rotating harvesting unit can be derived [33]. Let the coordinates of this point be , and its motion trajectory equation is:

where —Rotation radius of the rotating harvesting unit, mm;

—Rotational angular velocity of the rotating harvesting unit, rad/s;

—Any working hours, s;

—Device forward speed, m/s;

—The angle rotated by the rotating harvesting unit within time , rad;

The horizontal velocity and vertical velocity at any point on the rotating harvesting unit are:

where vx—Horizontal speed at the first point on the rotating harvesting unit, m/s;

vy—Vertical velocity at the first point on the rotating harvesting unit, m/s.

During the harvesting process, the motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit and the movement speed of the curved fixed baffle significantly impact pineapple harvesting efficiency. To ensure the continuity and reliability of pineapple feeding, positioning, separation, and lifting operations, the motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit must satisfy the residual pendulum line characteristics: a trajectory with loops, where around the trajectory ring, the horizontal velocity component is zero at the extreme points of the maximum transverse chord of the cosine curve of the trajectory ring. From a kinematic constraint perspective, this characteristic must satisfy the following conditions:

By Equations (8) and (9), obtain

If

where —Characteristic parameters of the rotating harvesting unit’s motion trajectory.

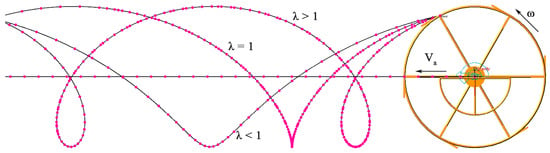

From the definition of the characteristic parameter , it can be seen that can take three values [34]: > 1, = 1, and < 1, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit.

Based on the established kinematic model, the characteristic parameter exerts a significant regulatory effect on both the trajectory morphology and the pineapple harvesting efficiency. The specific analysis is as follows:

When < 1, the motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit exhibits a short cycloid shape. At this point, the horizontal velocity component at any point on the cycloid aligns with the device’s forward direction. However, the linear velocity of the rotating harvesting unit is lower than the device’s forward speed, resulting in insufficient contact time between the device and pineapple fruits. This prevents the generation of stable and adequate shear torque, thereby compromising the separation of fruits from stems and reducing harvesting efficiency.

When = 1, the motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit transforms into a cycloid. A distinctive feature of this trajectory is that the horizontal component of velocity is zero at all points, meaning there is no relative velocity between the rotating harvesting unit and the fruit during contact. While this reduces fruit skin damage to some extent, the insufficient contact force and shear stress prevent effective separation of the fruit from the plant.

When > 1, the motion trajectory of the rotating harvesting unit exhibits a residual pendulum line. The maximum lateral chord forms at the looping point of this trajectory, and the horizontal component of velocity is directed opposite to the device’s forward movement. The formation of this loop structure significantly extends the contact time between the rotating harvesting unit and the fruit. This not only ensures the unit fully envelops the fruit but also adapts to the uneven distribution of pineapples in the field. Simultaneously, it provides sufficient shear stress to meet the requirements for separating the fruit from the plant, ultimately enhancing pineapple harvesting efficiency.

In summary, the value of directly affects the motion trajectory of the harvesting device. When λ > 1, meaning the circumferential linear velocity of the rotating harvesting unit exceeds the device’s forward speed, the rotating harvesting unit can perform its operations normally. Therefore, the theoretical lower limit for λ is λ > 1, and subsequent simulations and experiments are conducted based on this premise.

4.2. Rotation Radius of the Rotating Harvesting Unit

During harvesting operations, to prevent mechanical damage to pineapple plants caused by the rotating harvesting unit and reduce impact forces during fruit contact to preserve fruit quality, the structural parameters of the rotating harvesting unit must be designed such that its horizontal component velocity (x-direction) at points A and B—located at the maximum lateral chord of the cosine curve during rotation—is zero within a single motion cycle.

According to Equations (10) and (11), we obtain:

The rotating harvesting unit primarily operates at the calyx of pineapple plants during harvesting. Field measurements indicate an average plant height of 630 mm. Using Equations (9) and (10), the radius of the rotating harvesting unit is calculated as:

Combining with Equation (12), the radius of the rotating harvesting unit can be obtained:

where —Rotation radius of the rotating picking unit, mm;

—Pineapple feeding angle, °;

—The distance between the pineapple calyx and the ground is 410–430 mm.;

—Characteristic parameter of motion trajectory. Based on the growth characteristics of pineapple plants, is temporarily set to 1.7.

Considering various factors under actual growing conditions, the radius r of the rotating harvesting unit was determined to range from 485 to 534 mm based on design requirements. According variations in actual plant height and ground unevenness, a radius of = 500 mm (the midpoint of the 485–534 mm range) was selected. This value ensures efficient feeding for most pineapples while simplifying manufacturing and processing.

4.3. Feed Angle of the Rotating Harvesting Unit

In the analysis of pineapple harvesting operations, it can be assumed that the pineapple plant maintains an ideal posture perpendicular to the ground, and the rotating harvesting unit initiates fruit feeding from the point of maximum chord on a residual pendulum line. To avoid horizontal impact on the fruit during the initial feeding stage, a core design constraint is imposed: the horizontal component velocity of the rotating harvesting unit at the start of feeding is set to zero. This prevents additional forces or impact loads on the fruit caused by abrupt changes in horizontal velocity. When the horizontal component velocity , substituting the angular parameter into Equation (12) yields an ideal feeding angle for the rotary harvesting unit when .

4.4. Rotational Speed of the Rotating Harvesting Unit

During the harvesting process, to ensure each pineapple is accurately picked, the spacing between pineapple plants must be considered. This allows each rotating harvesting unit to complete the picking task. Given a constant travelling speed , the rotational speed of the harvesting unit can be determined.

Combining Equations (15)–(17) can be obtained:

Then

where —Pineapple plant spacing, take 400 mm;

—The arc length of each rotary harvesting unit spacing.

In summary, during pineapple harvesting, the device typically operates at a speed of 1–2 m per second, equipped with six rotating harvesting units. The rotational radius of the rotating harvesting unit assembly is 500 mm. The arc length between each rotating harvesting unit is mm. Calculations show that the rotational speed of the rotating harvesting unit is 25–50 r/min.

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. 3D Model Construction and Parameter Settings

In Unigraphics NX12.0 (Siemens Digital Industries Software, Plano, TX, USA), simplified models of the harvesting device and pineapple plant were created and imported into the ADAMS 2018 software (MSC Software Corporation, Newport Beach, CA, USA). Material properties were defined for both the harvesting device and the pineapple plant model. The parameters for the pineapple plant model’s pulp, rind, and core are shown in Table 1. Flexible treatment was applied to the pineapple fruit and stem models to simulate their real mechanical responses under external forces [35]. The sleeve force dynamically adjusts its transmission direction in real time as the flexible body deforms, precisely reproducing the entire process of force application by the harvesting device, stem bending, and fracture separation. Based on this, the flexible coupling established between the pineapple fruit and stem via the sleeve force simultaneously simulates their flexible connection and reflects the mechanical properties of the separation zone. A fixed joint is formed between the pineapple stem and the ground. A revolute joint and a prismatic joint are configured for the harvesting device. A prismatic joint is set up for the curved fixed baffle.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters for pineapple fruit.

Contact forces between the rotating harvesting unit and the curved fixed baffle in the harvesting apparatus were modeled separately for pineapple fruit and stems. Contact force parameters included stiffness coefficient, collision index, damping coefficient, and maximum penetration depth [36]. The collision index was set to 2.2; the damping coefficient ranged from 0.1% to 1% of the stiffness coefficient of the contact pair; and the maximum penetration depth was set to 0.1 mm. Friction forces between the harvesting device and the plant/stem were incorporated, defined using Coulomb’s law. The dynamic friction coefficient between the rotating harvesting unit and the fruit was set to 0.36, while that between the rotating harvesting unit and the stem was set to 0.24.

5.2. Simulation Test

Determine the travelling speed of the device based on actual operational requirements, and calculate the rotational speed of the harvesting device using λ. To fully reflect the variability of experimental parameters and cover as much of their potential range as possible, each travelling speed group is configured with four distinct harvesting rotational speeds (Table 2), enabling a comprehensive analysis of how parameter variations affect harvesting stress. Set pineapple plant spacing based on actual planting density, establishing a pineapple harvesting device and pineapple plant interaction model.

Table 2.

Simulation test plan.

5.3. Simulation Test Results and Analysis

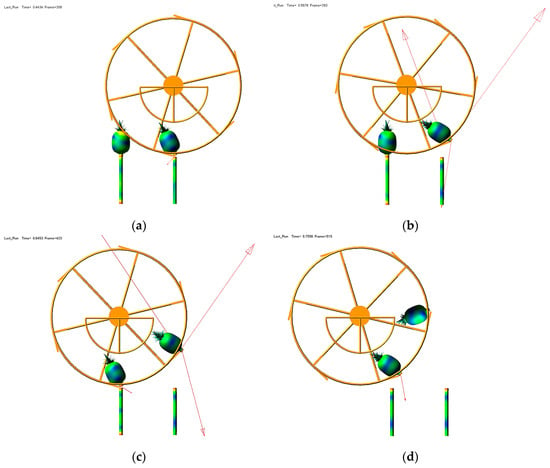

Simulation tests primarily analyze the tensile force exerted by the rotating harvesting unit on pineapple stems and the support force exerted by the curved fixed baffle on pineapple fruits under different parameters, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Simulated pineapple harvesting process. (a) The rotating harvesting unit makes contact with the first pineapple. (b) The first pineapple was picked. (c) The rotating harvesting unit makes contact with the second pineapple. (d) The second pineapple was picked.

5.3.1. Tensile Force Analysis

The core function of the rotating harvesting unit is to apply a tensile force to the pineapple stem, causing the fruit to break off at the calyx and thereby completing the harvesting operation. The magnitude of this tensile force directly determines both the fruit harvesting success rate and the extent of damage. This study employs simulation analysis to investigate the variation patterns of tensile force F1 under different operational parameters and its impact on harvesting effectiveness. The specific results are as follows:

When the harvesting device operates at a speed of .3 m/s, simulation results indicate that the tensile force applied by the rotating harvesting unit ranged from 102.33 N to 109.99 N, with an average value of approximately 107.6 N. This value falls below the pineapple stem fracture threshold range (100.42–165.38 N) measured in prior experiments. Under these conditions, some pineapple stem fail to meet the mechanical conditions required for fracture, experiencing only bending deformation, which significantly reduces harvesting success rates. Simultaneously, the low-speed operation prolongs the contact duration between the fruit and the rotating harvesting unit, resulting in a gradual loading process that further increases field operation time and constrains efficiency improvements. Additionally, when the trajectory parameter = 1.1, the issue of insufficient tensile force becomes more pronounced, making it difficult for the fruit to detach from the stem and maintaining a high harvesting failure rate.

As the harvesting device’s travelling speed increased to .5 m/s, the tensile force exerted by the rotating harvesting unit rose to 214.18–246.06 N. This range approached the upper limit of the pineapple stem’s fracture threshold, significantly enhancing the stability of the shearing process. Fruit stems could now break cleanly along the calyx, markedly improving harvesting success rates. Specifically, when trajectory parameter = 1.3 and rotational harvesting unit speed n = 37.0 r/min, the fluctuation amplitude of tensile force was minimal. This allowed the force to be applied uniformly to the fruit stem further ensuring the reliability of the harvesting process.

As the travelling speed further increases to .0 m/s, the tensile force significantly rises to 538.28–624.55 N, far exceeding the pineapple stem’s fracture threshold. Particularly when > 1.7, excessive tensile forces cause intense impact at the moment of stem breakage. This not only leads to uneven break surfaces but may also cause fruit to bounce off due to the impact, thereby reducing harvesting efficiency. Simultaneously, the vigorous shearing process at high rotational speeds subjects some fruits to excessive impact, resulting in skin damage or internal tissue bruising, significantly degrading harvest quality.

The comprehensive analysis indicates that = 214.18–246.06 N represents the optimal tensile force range. Specifically, when = 1.5 m/s and = 1.3, the shearing effect is most stable, fruit breakage is most uniform, harvesting success rate is highest, and mechanical impact on the fruit is minimized.

5.3.2. Support Force Analysis

The core function of the curved fixed baffle is to provide stable support for the crown bud of pineapple fruits, ensuring synergistic torque generation with the rotating harvesting unit. This study employs simulation analysis to investigate the variation patterns of support force under different operational parameters and its impact on harvesting efficiency. The specific results are as follows:

When the harvesting device operates at a speed of .3 m/s, simulation results indicate that the support force exerted by the curved fixed baffle within the range of 29.32–32.24 N. Under these low-speed conditions, fruit remains within the curved fixed baffle for extended periods. However, insufficient support force causes fruit to tilt, shifting the contact position between the rotating harvesting unit and the stem. This subsequently impacts harvesting success rates. Furthermore, when trajectory parameter = 1.1, with some fruit failing to enter the optimal harvesting trajectory altogether.

As the travelling speed increases to .5 m/s, the support force of the curved fixed baffle rises to 45.79–50.22 N. Under these conditions, the support force evenly acts on the fruit’s crown bud, maintaining a stable vertical orientation. This ensures the tensile force applied by the rotating harvesting unit precisely targets the stem at the calyx, achieving efficient harvesting. When the trajectory parameter λ falls within the range of 1.3–1.5, the curved fixed baffle provides optimal support for the fruit. This ensures stable entry into the rotating harvesting unit and achieves the highest harvesting success rate.

When the travelling speed is further increased to .0 m/s, the instantaneous support force of the curved fixed baffle significantly increases to 108.62–116.3 N. High speeds drastically shorten the fruit’s residence time within the rotating harvesting unit. The instantaneously increased support force generates strong impact loads, and excessive contact forces readily cause deformation or damage to the fruit’s crown bud. Particularly when > 1.7, the impact characteristics of the support force become more pronounced. Fruit posture stability declines sharply, and collisions between fruit and the curved fixed baffle may even cause damage, severely compromising harvesting quality.

Based on the simulation results summarized above, the optimal support force range for the curved fixed baffle is = 45.79–50.22 N. Specifically, when = 1.5 m/s and = 1.3–1.5, the curved fixed baffle exhibits uniform support force, achieving the highest fruit stability and the smoothest harvesting process.

5.3.3. Comprehensive Analysis

Based on simulation results tensile force and support force , the synergistic effects of machine travelling speed , rotational speed , and trajectory parameter on pineapple harvesting performance are as follows:

When = 0.3 m/s, the support force exerted by the curved fixed baffle ranges between 29.32 N and 32.24 N. This force is insufficient to maintain the fruit’s stable posture, making it prone to deflection. Simultaneously, the tensile force generated by the rotating harvesting device ranges from 102.33 N to 109.99 N, falling below the critical pineapple stem fracture threshold measured in prior experiments, ultimately resulting in a high harvesting failure rate. When = 3.0 m/s, the support force increases to 108.62–116.3 N. Excessive support force intensifies fruit compression, potentially causing damage. Tensile force surged to 538.28–624.55 N, far exceeding the stalk fracture threshold. The impact force from fracture damaged the fruit, significantly degrading harvest quality.

When = 1.5 m/s, the average support force is 47.39 N and the average tensile force is 225.45 N. Both fall within their respective optimal mechanical ranges. Harvesting at this point yields the best results. At four levels of λ = 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.7, the upper limit and optimal value of λ were determined by quantifying the tensile force F1 and the supporting force F2. When = 1.1, the tensile force of the rotating harvesting unit is insufficient to meet the mechanical requirements for stem breakage, making it difficult to separate the fruit from the plant. When > 1.7, the impact characteristics of the tensile force become excessively strong, increasing the risk of mechanical damage to the fruit. Therefore, the theoretical upper limit of λ is λ < 1.7.

By comparing the values in Table 2 across different λ levels, at λ = 1.3, = 225.45 N exceeds the fracture threshold, satisfying the fracture margin. = 47.39 N falls within the optimal support force range. All metrics outperform those at λ = 1.1 and λ = 1.5. Therefore, simulation experiments determine the optimal range for λ as 1 < λ ≤ 1.7, with λ = 1.3 being the optimal value.

In summary, the optimal operating parameters for the pineapple harvesting device are: .5 m/s, = 37 r/min, = 1.3. Under these conditions, the curved fixed baffle provides uniform support force and stable tensile force, ensuring a smooth harvesting process while preventing damage. This achieves efficient harvesting with minimal injury.

6. Bench Test

6.1. Pineapple Harvesting Experiment

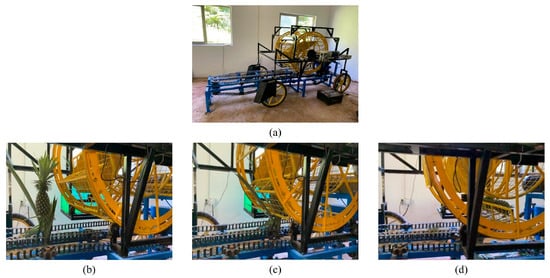

The pineapple harvesting test rig primarily consists of a gripper chain conveyor mechanism, a pineapple harvesting device, Hall sensors, and a motor speed controller. The harvesting device is powered mainly by a DC motor, with its speed controlled via the speed controller. The gripper chain conveyor mechanism is powered primarily by a three-phase asynchronous motor, whose speed is regulated through a variable frequency drive to adjust the chain conveyor speed. The experiment material consisted of intact Tainung 16 pineapples plants. To replicate the interference of field leaves on the harvesting mechanism, all pineapple plants retained functional leaves on the upper stem section (i.e., key leaves covering the fruit stem and crown bud), while non-functional leaves from the lower stem sections were removed. During testing, the plants were conveyed via the gripping chain to the position beneath the harvesting device, simulating the machine’s movement in the field. Test parameters for the bench test are set based on theoretical calculations and simulation parameters from the preceding section, with five replicates conducted for each level. As shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Pineapple harvesting test bed. (a) Test bed. (b) Convey. (c) Feed. (d) Picking.

6.2. Evaluation Indicators

Based on the agronomic requirements for pineapple harvesting in actual production, the primary evaluation metrics for this experiment are the harvest rate and damage rate of pineapples. Pineapple rinds are relatively thick and tough, making it difficult for external physical impacts or injuries to penetrate the skin. Damage to the flesh cannot be directly observed. Therefore, the harvested pineapples were stored under constant temperature conditions for three days before being cut open to examine potential injury locations and whether the flesh had discolored. Undamaged flesh retained its original color at the time harvesting, while damaged flesh showed a yellowish-brown hue [10].

Pineapple harvesting rate is a key indicator for evaluating mechanical performance, while damage rate reflects the extent of physical damage inflicted on pineapples during the harvesting operation. A lower damage rate typically indicates that the harvesting device more effectively preserves pineapple integrity, thereby enhancing harvesting efficiency and product quality [37,38].

The pineapple harvesting rate refers to the ratio of the actual number of successfully harvested pineapples to the total number of pineapples that should be harvested, as shown in Equation (20). The harvesting damage rate refers to the proportion of pineapples damaged during the harvesting process, specifically the percentage of successfully harvested pineapples that sustain damage due to mechanical operations, as shown in Equation (21).

where is pineapple harvesting rate, is the damage rate; is the number of successfully harvested pineapple; is the number of unsuccessfully harvested pineapple; is the number of undamaged pineapples successfully harvested; is the number of damaged pineapples successfully harvested.

6.3. Bench Test Design and Results Analysis

The test results are shown in Table 3. The average pineapple harvesting success rate was 74.94%, with an average damage rate of 8.22%.

Table 3.

Experimental design and results.

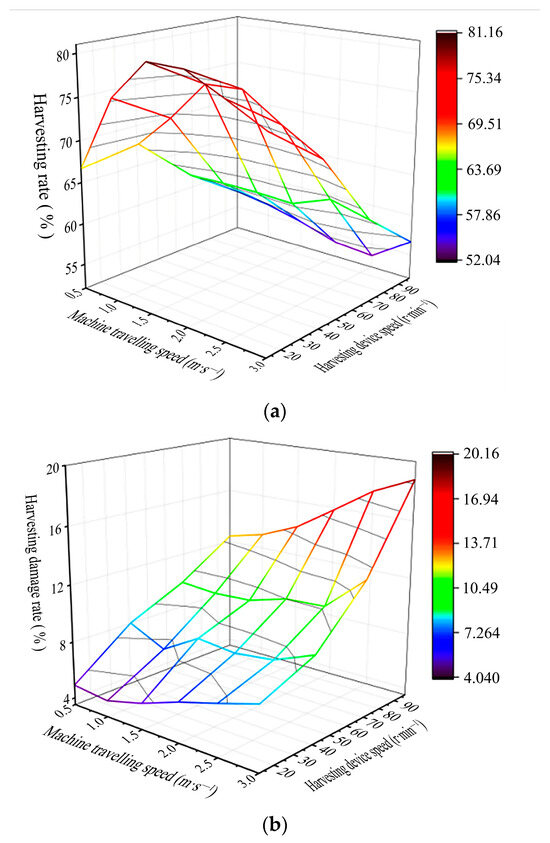

Figure 10a illustrates the relationship between the harvesting rate and the combination of the device’s travel speed and the harvesting device’s rotational speed. The figure reveals that when the travelling speed is low (1.0 m/s), the harvesting rate generally remains within the lower range of 66.70–80.00%. This phenomenon aligns with previous simulation results: at low speeds, the insufficient tensile force of the rotating harvesting unit prevents some fruits from reaching the stem breakage threshold, thus failing to achieve effective detachment. As the travelling speed increases to 1.5–2.0 m/s, the harvesting rate shows a significant upward trend. When = 1.3, the harvesting rate reaches its peak of 84.70%, indicating that this parameter combination achieves uniform tensile force and the highest harvesting success rate. However, when > 2.5 m/s, the harvesting rate fluctuates. This may be due to excessive shear impact force causing fruit to bounce off during breakage, failing to land smoothly in the harvesting device and thus affecting harvesting efficiency. Consequently, optimizing the matching relationship between travelling speed and rotational speed can effectively enhance the harvesting rate.

Figure 10.

Bench test results. (a) Harvesting rate. (b) Damage rate.

Figure 10b indicates that under low-speed conditions (.5 m/s), the damage rate ranges from 6.65% to 7.55%, remaining at a relatively low level overall. This is attributed to the reduced tensile force at low speeds, which exerts weaker destructive effects on both the fruit skin and internal tissues. This indicates insufficient tensile force at this parameter setting, coupled with a gradual application process. While reducing impact damage, it fails to meet the requirements for efficient harvesting. As the travelling speed increases to 1.5 m/s, the damage rate range expands to 7.75–9.25%. At = 1.3, the damage rate stabilizes at a moderate level of 8.25%, while the harvesting rate reaches its maximum value. This indicates that this parameter combination achieves a good balance between high harvesting rate and low damage rate. When the travelling speed is further increased to 2.5 m/s, the damage rate significantly rises to 8.85–10.95%; Particularly at = 1.7, damage rates peaked. This occurred because excessive tensile forces caused fruit skin rupture or internal tissue bruising, severely compromising fruit quality. Therefore, while excessively high values may partially maintain harvesting rates, they substantially increase damage risks, necessitating a reasonable trade-off between the two objectives.

Based on the combined results of harvesting rate and damage rate tests, the optimal operating parameter combination for the pineapple harvesting device is: travelling speed of 1.5 m/s, characteristic parameter of = 1.3, and rotational speed of 37 r/min. At these parameters, the harvesting rate reaches its maximum value of 84.70%, while the damage rate remains at a moderate level of 8.25%. This configuration exhibits optimal shearing characteristics, enabling smooth fruit separation with minimal damage.

7. Field Experiment

7.1. Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted in May 2025 at the pineapple cultivation base of the South Subtropical Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, in Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province. The experimental plots were selected from contiguous planting areas with flat terrain and uniformly grown pineapple plants. The experimental variety was Tainung 16 pineapples, planted at a density of approximately 45,000 plants ha−1. The plots were free from pest and disease infestations and dense weed growth to ensure the representativeness of the experimental samples.

The experimental operation device comprised a biomimetic pineapple harvesting device independently developed in this study and a high-clearance traction machine (Figure 11). The harvesting device’s forward motion was entirely powered by the high-clearance traction machine, which featured a lockable multi-speed regulation mechanism. By shifting between different gears, stable and precise control of travel speed was achieved, ensuring the operating speed remained consistently within the target range throughout the process.

Figure 11.

Field experiment. (a) experimental site. (b) experimental device. (c) harvest results.

7.2. Experimental Design and Results Analysis

Field experiments were conducted using the optimal operating parameters selected from bench trials. Specific parameter settings were as follows: harvesting unit travelling speed of 1.5 m/s, characteristic parameter = 1.3, and rotating harvesting unit speed of 37 r/min. This configuration aimed to validate the operational stability of these parameters under actual field conditions. A randomized block design was employed, with 10 independent operational replicates conducted.

Each experiment utilized a 40 m continuous planting row divided into three zones: Front 10 m calibration zone: Equipment fine-tuned to ensure operational stability. Middle 20 m measurement zone: Manual counting of total fruit and marking of start/end positions. Rear 10 m buffer zone: Used for device deceleration and shutdown; no data collection Residual branches, leaves, or fruit debris were removed from the device to prevent interference with experimental results.

Field experiment results indicate that under the optimal operating parameters, the biomimetic harvesting device achieved an average harvesting rate of 81.23% and a fruit damage rate of 9.35%, which was consistent with the bench test findings. Detailed results for each group are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Field experiment results.

7.3. Comparison with Manual Harvesting

Currently, pineapple harvesting in actual production remains predominantly manual. Although some research on pineapple harvesting machinery exists, most remain in the experimental stage. No commercially viable combined pineapple harvesters are available for large-scale operations, making it impossible to directly compare the harvesting device developed in this study with existing mechanized equipment. Therefore, this section focuses on analyzing and discussing the differences between the developed device and manual harvesting in three aspects: harvesting costs, operational efficiency, and fruit damage rates.

Operational Efficiency: Operating at optimal parameters (1.5 m/s forward speed, 37 r/min rotational speed), a single unit of the harvesting device can cover approximately 0.15 hectares per hour. Based on an 8 h workday and a planting density of 45,000 plants per hectare, one machine can harvest approximately 1.2 hectares per day. In contrast, a skilled manual harvester averages about 1000 plants per day, equivalent to roughly 0.022 hectares. Thus, the mechanized harvesting efficiency is approximately 55 times higher than manual harvesting.

Fruit Damage Rate: The field experiment demonstrated an average fruit damage rate of 9.35% for the harvesting de-vice. Manual harvesting typically results in a lower damage rate (approximately 1%), mainly due to accidental drops during handling. However, the significantly higher efficiency of mechanized harvesting offsets the moderately higher damage rate, especially for large-scale operations where throughput is critical.

Economic Cost Analysis: A preliminary cost comparison was conducted on a per-hectare basis. For manual harvesting, employing skilled labor at 200 CNY per day (harvesting 0.022 hectares daily) translates to a labor cost of approximately 9091 CNY per hectare. For mechanized harvesting, the daily operating cost (including fuel and operator wages) is about 1800 CNY. With a daily capacity of 1.2 hectares, the operational cost per hectare is approximately 1500 CNY. Although the initial investment and maintenance costs for the machinery are not included in this operational cost, large-scale and long-term deployment would substantially amortize these fixed costs, making mechanized harvesting economically advantageous by drastically reducing labor dependency and cost per unit area.

In summary, while the developed device exhibits a higher fruit damage rate than manual harvesting, it offers overwhelming advantages in operational efficiency and potential long-term cost reduction, addressing the core challenges of labor scarcity and high costs in large-scale pineapple production.

8. Conclusions

To mitigate the challenges of high labor intensity, low operational efficiency, and elevated fruit damage rates associated with large-scale pineapple harvesting, this study developed a biomimetic pineapple harvesting device inspired by the mechanics of manual stem-breaking, tailored specifically for the Tainung 16 pineapple cultivar. Key findings of this research are as follows:

- (1)

- Field measurements and mechanical characterization tests quantified the tensile force required for the detachment of Tainung 16 pineapple fruit from the stem at the calyx abscission zone as 100.42–165.38 N. This foundational mechanical dataset enabled the rational design of the harvesting device, ensuring sufficient force for effective fruit-stem separation while mitigating excessive mechanical damage to the fruit.

- (2)

- Dynamic simulation via Adams 18.0 software identified the optimal operational parameters: a travelling speed of 1.5 m/s, a rotational speed of 37 r/min for the rotary harvesting unit, and a motion trajectory characteristic parameter (λ) of 1.3. Subsequent field validation demonstrated that the device achieved an average harvesting rate of 81.23% and a fruit damage rate of 9.35%, effectively addressing the core technical bottlenecks of low efficiency and high fruit damage in mechanized pineapple harvesting.

This biomimetic harvesting device and its optimized operational parameters provide tangible technical support for advancing the mechanization level of pineapple harvesting in major production regions of China. Nevertheless, the present study exhibits inherent limitations: validation was exclusively conducted on the Tainung 16 cultivar under homogeneous, flat-field conditions, with no systematic assessment of the device’s performance under complex agronomic scenarios nor its adaptability to other commercially important pineapple cultivars. Future research endeavors will focus on enhancing the device’s compatibility with diverse pineapple varieties, different maturity stages and field environments, as well as integrating machine vision technology to further improve its operational efficiency and robustness in complex natural settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and W.Z.; methodology, W.Z.; software, P.S.; validation, H.S. and P.S.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, Z.X. and M.L.; resources, H.Z.; data curation, H.Z. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S., M.L. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, H.S., W.Z., H.L., Z.X. and H.Z.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.S., H.L. and Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 325QN432), Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences for Science and Technology Innovation Team of National Tropical Agricultural Science Center (NO.CATASCXTD202513), Hainan Province’s Key Research and Development Project “Development and Demonstration of a Low-Damage and High-Efficiency Combined Pineapple Harvester” (NO. ZDYF2025XDNY099), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (NO.1630062025018), Hainan Province’s Key Research and Development Project “Pineapple Mechanized Harvesting Key Technology and Equipment Integration R&D and Demonstration” (No. ZDYF2023XDNY058).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in this article in the form of figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the College of Engineering, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University and the South Subtropical Crops Research Institute, China Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences. We gratefully acknowledge the foundations for their financial support of this study, and our researchers and collaborators for their valuable contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ikram, M.M.M.; Mizuno, R.; Putri, S.P.; Fukusaki, E. Comparative metabolomics and sensory evaluation of pineapple (Ananas comosus) reveal the importance of ripening stage compared to cultivar. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 132, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, F.; Cabral, J. Pineapple germplasm in Brazil. Int. Pineapple Symp. 1992, 334, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horry, J.; Lenoir, H.; Perrier, X.; Teisson, C. The CIRAD pineapple germplasm database. IV Int. Pineapple Symp. 2002, 666, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Ehsani, R.; Toudeshki, A.; Zou, X.J.; Wang, H.J. Experimental study of vibrational acceleration spread and comparison using three citrus canopy shaker shaking tines. Shock Vib. 2017, 1, 9827926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.G.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, G.R.; Li, G.J.; Yan, B.; Pan, D.X.; Luo, X.W.; Li, J.H. Research status and development trend of key technologies for pineapple harvesting equipment: A review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Zheng, Y.; Lai, J.S.; Cheng, Y.F.; Chen, S.Y.; Mai, B.F.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Xue, Z. Extracting visual navigation line between pineapple field rows based on an enhanced YOLOv5. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P. Use of shaking mechanism and robotic arm in fruit harvesting: A comprehensive review. J. Crop Weed 2021, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Cargill, B.F.; Fridley, R.B. Economic aspects related to the fruit industry. In Principles and Practices for Harvesting and Handling Fruits and Nuts; AVI Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1983; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.X.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, X.M.; Sun, W.S.; Sun, H.T.; Zou, H.F.; Yu, Z.Z.; Wang, C. Research progress of mechanization technology and equipment for the whole pineapple production process. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2025, 47, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, T.H.; Zeng, T.Y.; Ma, R.J.; Cheng, Y.F.; Yan, Z.; Qiu, J.; Long, Q. Prediction of internal mechanical damage in pineapple compression using finite element method based on Hooke’s and Hertz’s laws. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 308, 111592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Liu, W.; Zeng, Y.T.; Cheng, Y.F.; Yan, Z.; Qiu, J. A multi-flexible-fingered roller pineapple harvesting mechanism. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K.; Chayalakshmi, C. Microcontroller-based semiautomated pineapple harvesting system. Int. Conf. Mob. Comput. Sustain. Inform. 2021, 12, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Kahl, W.H.; Moffett, L. Is mechanically harvesting pineapple practical? Agric. Eng. 1970, 51, 564–565. [Google Scholar]

- Plebe, A.; Grasso, G. Localization of spherical fruits for robotic harvesting. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2001, 13, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Henten, E.J.; Hemming, J.; Van Tuijl, B.; Kornet, J.; Meuleman, J.; Bontsema, J.; Van Os, E.A. An autonomous robot for harvesting cucumbers in greenhouses. Auton. Robot. 2002, 13, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Yang, X.; Ji, J.; Jin, X.; Chen, L. Design and test of a pineapple picking end-effector. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2019, 35, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Z.; Lian, H.S.; Gong, M.F.; Chen, H.L.; Liao, G.X.; Deng, Z.X. Structural design and experiment of pineapple picking manipulator. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 51, 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Design of the pineapple picking manipulator. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2014, 12, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.F.; Li, B.; Liu, G.Y.; Xu, L.M. Design and experiment of pineapple picking manipulator. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2012, 28, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.H.; Nie, X.N.; Wu, J.M.; Zhang, D.; Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.F.; Yan, Z.; Qiu, J.; Long, Q. Pineapple (Ananas comosus) fruit detection and localization in natural environment based on binocular stereo vision and improved YOLOv3 model. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, M.H.; Li, L. Identification of pineapple fruits in the field based on monocular vision. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2010, 26, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, H.F.; Huang, W.Q.; Zhang, C. Construction and field trial of low-cost binocular vision platform for pineapple harvesting machinery. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2012, 28, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, M. In-field recognition and navigation path extraction for pineapple harvesting robots. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2013, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.H.; Wu, Z.M.; Yan, M.S.; Liang, R.J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yan, F.W.; Wu, T.J.; Deng, G.K.; Yao, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.L. Design and experiment of multi-arm pineapple picking robot based on machine vision. Mech. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 52, 141–144+154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Ma, R.J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, E.H.; Yang, J.P.; Wen, G.Z.; Pan, X. Detection method of cutting point of pineapple stem based on multi-sensor information fusion. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2024, 43, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Chen, R.Y.; Zhang, X.M. Research status of mechanized planting and harvesting of pineapple. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 41, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisomboon, P.; Tanaka, M.; Kojima, T. Evaluation of tomato textural mechanical properties. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.D.; Chen, M.W.; Xie, J.Q.; Deng, G.R.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, S. Preliminary study on the cultivation mode of mechanized pineapple and its mechanization in Zhanjiang. Mod. Agric. Equip 2022, 43, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke, R.; Gortner, W. Stem bromelain—A new protease preparation from pineapple plants. Econ. Bot. 1957, 11, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, L.; Yue, D.; Wang, B.; Li, J. Fracture mechanism and separation conditions of pineapple fruit-stem and calibration of physical characteristic parameters. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2023, 16, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, R. Anatomical, physiological, and hormonal aspects of abscission in citrus. Hortic. Rev. 1993, 15, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, E.; Fernández, R.; Sepúlveda, D.; Armada, M.; Gonzalez-de-Santos, P. Soft grippers for automatic crop harvesting: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalali, A.; Abdi, R. The effect of ground speed, reel rotational speed and reel height in harvester losses. J. Agric. Sustain. 2014, 5, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Jin, M.; Jiang, T. Design and parameter optimization of variable speed reel for oilseed rape combine harvester. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, H.J.; Yang, H.W.; Yan, Y.F.; Sun, J.W.; Zhao, G.Z.; Wang, J.X.; Fan, G.Q. Optimization and experimental study of structural parameters for a low-damage packing device on an apple harvesting platform. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, X.; Zheng, W.; Wu, Y. Structure design and analysis of pineapple picking mechanism based on the principle of shutter mechanism. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 382, 042049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Li, C.; Zheng, Z. Design and analysis of semi-automatic screw type pineapple picking-collecting machine. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 27, 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Shi, J.; Zhang, R. Structure design of automatic pineapple picking machine. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2011, 39, 9861–9863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).