Organic Chromium Sources as a Strategy to Improve Performance, Carcass Traits, and Economic Return in Lambs Finishing at Heavier Weights

Abstract

1. Introduction

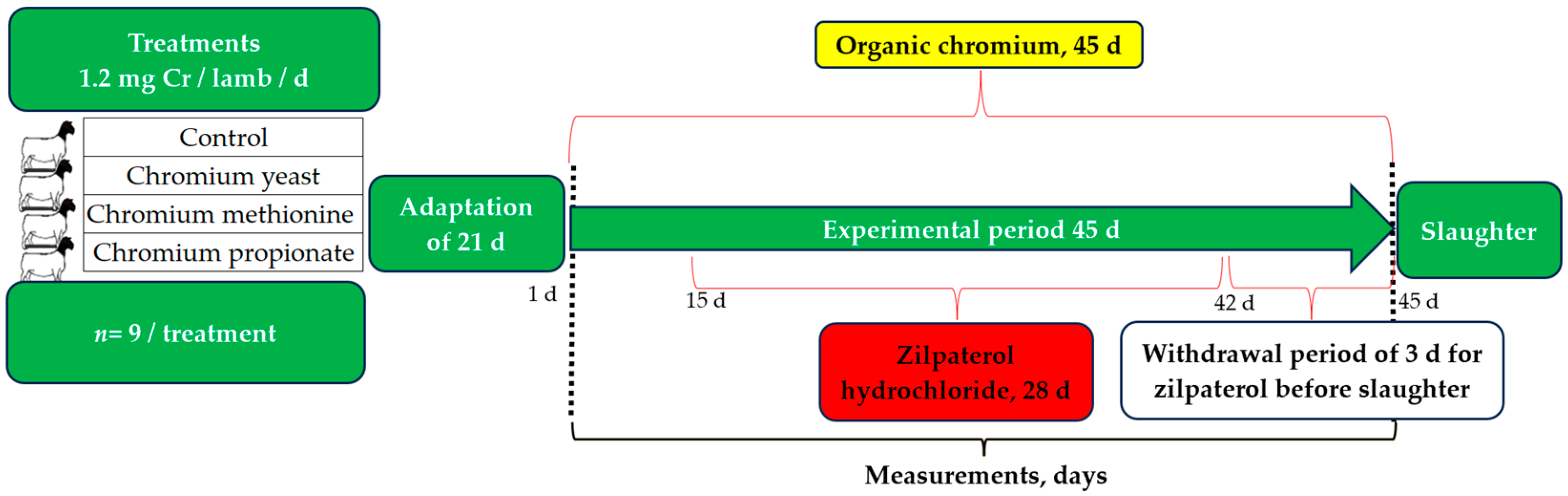

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Processing, Housing, and Feeding

2.2. Treatments and Diets

2.3. Chemical Analyses

2.4. Calculations

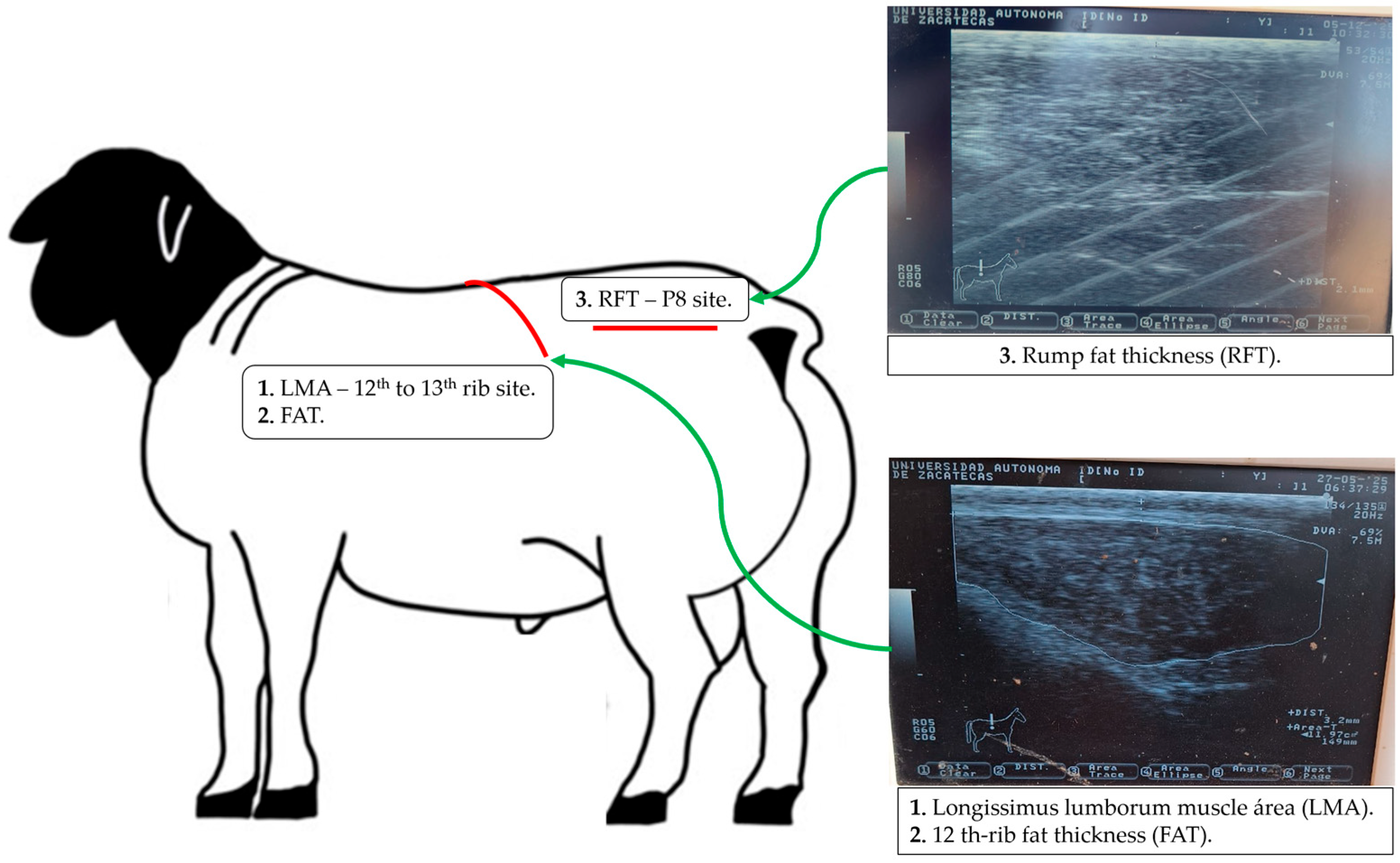

2.5. Body Fat Reserves and Longissimus Muscle Area

2.6. Slaughter Procedure and Visceral Organ Mass Determination

2.7. Carcass Characteristics

2.8. Whole Cuts

2.9. Meat Quality

2.10. Analysis of Economic Profitability

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance and Dietary Energetics

3.2. Visceral Mass

3.3. Ultrasound Measurement, Carcass Characteristics, Whole Cuts and Meat Characteristics

3.4. Economic Profitability

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance and Dietary Energetics

4.2. Visceral Mass

4.3. Ultrasound Measurement, Carcass Characteristics, Whole Cuts and Meat Characteristics

4.4. Cost/Income

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowen, M.K.; Ryan, M.P.; Jordan, D.J.; Beretta, V.; Kirby, R.M.; Stockman, C.; McIntyre, B.L.; Rowe, J.B. Improving sheep feedlot management. Int. J. Sheep Wool Sci. 2006, 54, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Galyean, M.L.; Hales, K.E.; Smith, Z.K. Evaluating differences between formulated dietary net energy values and net energy values determined from growth performance in finishing beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 10, skad230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeman, M.E. Effects of metabolic modifiers on carcass traits and meat quality. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Angulo, A.; Valdés, Y.S.; Carrillo-Muro, O.; Castro-Pérez, B.I.; Barreras, A.; López-Soto, M.A.; Plascencia, A.; Dávila-Ramos, H.; Ríos, F.G.; Zinn, R.A. Effects of feeding different levels of chromium-enriched live yeast in hairy lambs fed a corn-based diet: Effects on growth performance, dietary energetics, carcass traits and visceral organ mass. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2013, 53, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Muro, O.; Rivera-Villegas, A.; Hernandez-Briano, P.; Lopez-Carlos, M.A.; Castro-Perez, B.I. Effect of dietary calcium propionate inclusion period on the growth performance, carcass characteristics, and meat quality of feedlot ram lambs. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Muro, O.; Rivera-Villegas, A.; Hernandez-Briano, P.; Lopez-Carlos, M.A.; Plascencia, A. Effects of duration of calcium propionate supplementation in lambs finished with supplemental zilpaterol hydrochloride: Productive performance, carcass characteristics, and meat quality. Animals 2023, 13, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Muro, O.; Rivera-Villegas, A.; Hernández-Briano, P.; López-Carlos, M.A.; Aguilera-Soto, J.I.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Mendez-Llorente, F. Effect of calcium propionate level on the growth performance, carcass characteristics, and meat quality of feedlot ram lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 207, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, P.A.; Orzuna-Orzuna, J.F.; Chay-Canul, A.J.; Vázquez-Silva, G.; Díaz-Galván, C.; Razo-Ortíz, P.B. Meta-analysis of organic chromium dietary supplementation on growth performance, carcass traits, and serum metabolites of lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 233, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, S.; Habibian, M.; Jensen, S.K. A review on the role of chromium supplementation in ruminant nutrition—Effects on productive performance, blood metabolites, antioxidant status, and immunocompetence. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 186, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, W. Chromium in human nutrition: A review. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.B. The biochemistry of chromium. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechová, A.; Pavlata, L. Chromium as an essential nutrient: A review. Vet. Med. 2007, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A.; Ganjkhanlou, M.; Zali, A. Effects of Cr methionine on glucose metabolism, plasma metabolites, meat lipid peroxidation, and tissue chromium in Mahabadi goat kids. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 164, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.; El-Hack, M.E.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Hendy, Y.A.; Ghanem, H.A.; Alsafy, S.A.; Khafaga, A.F.; Noreldin, A.E.; Shannen, H.; Samak, D.; et al. Potential use of chromium to combat thermal stress in animals: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Barbosa, O.Y.; Carrillo-Muro, O.; Hernández-Briano, P.; Rodríguez-Cordero, D.; Rivera-Villegas, A.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Plascencia, A.; Lazalde-Cruz, R. Effect of calcium propionate and chromium-methionine supplementation: Growth performance, body fat reserves, and blood parameters of high-risk beef calves. Ruminants 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Polansky, M.M.; Bryden, N.A.; Roginski, E.E.; Mertz, W.; Glinsmann, W. Chromium supplementation of human subjects: Effects on glucose, insulin, and lipid variables. Metabolism 1983, 32, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowat, D.N. Organic Chromium in Animal Nutrition; CABI Digital Library: Guelph, ON, Canada, 1997; ISBN 978-0-9681853-0-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, M.D.; Wood, C.M.; Harper, A.F.; Kornegay, E.T.; Anderson, R.A. Dietary chromium picolinate additions improve gain:feed and carcass characteristics in growing-finishing pigs and increase litter size in reproducing sows. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-García, Y.S.; Aguilera-Soto, J.I.; Barreras, A.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Gómez-Vázquez, A.; Plascencia, A.; Ríos, F.G.; Reyes, J.J.; Stuart, J.; Torrentera, N. Growth performance and carcass characteristics in finishing feedlot heifers fed different levels of chromium-enriched live yeast or fed zilpaterol hydrochloride. Cuban J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 45, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mendoza, B.; Aguilar-Hernández, A.; López-Soto, M.A.; Barreras, A.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Navarro, F.J.M.; Torrentera, N.; Zinn, R.A.; Plascencia, A. Effects of high-level chromium methionine supplementation in lambs fed a corn-based diet on the carcass characteristics and chemical composition of the longissimus muscle. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2015, 39, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Pérez, B.I.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Urías-Estrada, J.D.; Ponce-Barraza, E.; Valdés-García, Y.; Barreras, A.; Carrillo-Muro, O.; Plascencia, A. Effects of feeding different levels of chromium-methionine in hairy lambs finished with high-energy diets under high ambient heat load. Large Anim. Rev. 2025, 31, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maioli, B.M.; Ribeiro, M.G.; de Carvalho, A.; Goncalves, L.A.; de Almeida, D.L.; de Zoppa, A.L.D.V.; Gallo, S.B. Nutrition of lambs with chromium propionate and its effects on metabolism, performance and meat quality. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 237, 107306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Najaf Panah, M.J.; Bakhtiarizadeh, M.R.; Emami, A. Transcription analysis of genes involved in lipid metabolism reveals the role of chromium in reducing body fat in animal models. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015, 32, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniek, H.; Krejpcio, Z. The effects of supplementary Cr3 (chromium(III) propionate complex) on the mineral status in healthy female rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 180, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOM-024-ZOO-1995; Especificaciones y Características Zoosanitarias Para el Transporte de Animales, Sus Productos y Subproductos, Productos Químicos, Farmacéuticos, Biológicos y Alimenticios Para Uso en Animales o Consumo Por Éstos. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/202301/NOM-024-ZOO-1995_161095.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- NOM-051-ZOO-1995; Trato Humanitario en la Movilización de Animales. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/senasica/documentos/nom-051-zoo-1995 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999; Especificaciones Técnicas Para la Producción, Cuidado y Uso de Los Animales de Laboratorio. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/senasica/documentos/nom-062-zoo-1999 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- NOM-033-SAG/ZOO-2014; Métodos Para dar Muerte a Los Animales Domésticos y Silvestres. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5405210&fecha=26/08/2015#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- AOAC (Official Methods of Analysis). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 20th ed.; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemist. Methods 925.09 and 926.08. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Sheep. Nutrient Requirements of Sheep, 6th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Angulo, A.; Barreras-Serrano, A.; Contreras, G.; Obregon, J.F.; Robles-Estrada, J.C.; Plascencia, A.; Zinn, R.A. Influence of level of zilpaterol hydrochloride supplementation on growth performance and carcass characteristics of feedlot lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 80, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, R.A.; Barreras, A.; Owens, F.N.; Plascencia, A. Performance by feedlot steers and heifers: Daily gain, mature body weight, dry matter intake, and dietary energetics. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 2680–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luaces, M.L.; Calvo, C.; Fernández, B.; Fernández, A.; Viana, J.L.; Sánchez, L. Predicting equations for tisular composition in carcass of Gallega breed lambs. Arch. Zootec. 2008, 57, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- NAMP. The Meat Buyers Guide; North American Meat Processor Association: Weimar, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T.C.; Ockerman, H.W. Water binding measurement of meat. J. Food Sci. 1981, 46, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMSA. Research Guidelines for Cookery, Sensory Evaluation, and Instrumental Tenderness Measurements of Meat, 2nd ed.; American Meat Science Association: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS OnDemand for Academics: SAS Studio, versión 3.8; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.sas.com (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Spears, J.W.; Whisnant, C.S.; Huntington, G.B.; Lloyd, K.E.; Fry, R.S.; Krafka, K.; Hyda, J. Chromium propionate enhances insulin sensitivity in growing cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 2037–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suttle, N.F. Mineral Nutrition of Livestock, 4th ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; p. 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltan, M.A. Effect of dietary chromium supplementation on productive and reproductive performance of early lactating dairy cows under heat stress. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2010, 94, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Zhou, X. Effects of concentrate level and chromium-methionine supplementation on the perf ormance, nutrient digestibility, rumen fermentation, blood metabolites, and meat quality of Tan lambs. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Vara, I.A.; González-Muñoz, S.S.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Bórquez-Kegley Gastelum, J.L.; Bárcena-Gama, R.; Mendoza-Martínez, G.; Zapata, L.E.; Landois-Palencia, L.L. Effects of feeding selenium-yeast and chromium-yeast to finishing lambs on growth, carcass characteristics, and blood hormones and metabolites. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 152, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, S.; Habibi, Z.; Karimi-Dehkordi, S. Grain source and chromium supplementation: Effects on feed intake, meal and rumination patterns, and growth performance in Holstein dairy calves. Animal 2019, 13., 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Raboisson, D.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X. Effects of dietary chromium supplementation on dry matter intake and milk production and composition in lactating dairy cows: A meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1076777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Angulo, A.; Zapata-Ramírez, O.; Castro-Pérez, B.I.; Urías-Estrada, J.D.; Gaxiola-Camacho, S.; Angulo-Montoya, C.; Ríos-Rincón, F.G.; Barreras, A.; Zinn, R.A.; Leyva-Morales, J.B.; et al. The effects of single or combined supplementation of probiotics and prebiotics on growth performance, dietary energetics, carcass traits, and visceral mass in lambs finished under subtropical climate conditions. Biology 2021, 10, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafpanah, M.J.; Zali, M.S.A.; Moradi-Shahrebabak, H.; Mousapour, H. Chromium downregulates the expression of acetyl CoA carboxylase 1 gene in lipogenic tissues of domestic goats: A potential strategy for meat quality improvement. Gene 2014, 543, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Gao, Z.; Chu, W.; Cao, Z.; Li, C.; Zhao, H. Effects of chromium picolinate on fat deposition, activity and genetic expression of lipid metabolism-related enzymes in 21-day-old Ross broilers. Asian Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, A.T.; Leury, B.J.; Sabin, M.A.; Fahri, F.; DiGiacomo, K.; Lien, T.F.; Dunshea, F.R. Dietary nano chromium picolinate can ameliorate some of the impacts of heat stress in cross-bred sheep. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Camarena, L.; Domínguez-Vara, I.; Bórquez-Gastelum, J.; Sánchez-Torres, J.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.; Mariezcurrena-Berasain, A.; Morales-Almaráz, E.; Salem, A.Z.M. Effects of organic chromium supplementation to finishing lambs diet on growth performance, carcass characteristics and meat quality. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Camarena, L.; Domínguez-Vara, I.; Morales-Almaráz, E.; Bórquez-Gastelum, J.; Trujillo-Gutiérrez, D.; Acosta-Dibarrta, J.P.; Sánchez-Torres, J.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.; Mondragón-Ancelmo, J.; Barajas-Cruz, R.; et al. Effects of dietary chromium-yeast level on growth performance, blood metabolites, meat traits and muscle fatty acids profile, and microminerals content in liver and bone of lambs. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 19, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.P.; Spears, J.W. Vitamin and trace mineral effects on immune function of ruminants. In Ruminant Physiology; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 979-90-8686-566-6. [Google Scholar]

| Ingredients | % of Dietary DM |

|---|---|

| Corn grain, flaked | 50.0 |

| Corn stover | 22.0 |

| Distillers Gr., solubles dehy | 8.0 |

| Soybean, meal—44 | 8.0 |

| Molasses, cane | 7.9 |

| Urea | 0.5 |

| Sodium sesquicarbonate | 1.5 |

| Calcium carbonate | 1.0 |

| Sodium bentonite | 0.8 |

| Salt | 0.3 |

| Premix a | 0.1 |

| Chemical composition, % | |

| Dry matter | 86.94 |

| Organic matter | 79.54 |

| Crude protein | 14.04 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 21.83 |

| Ether extract | 3.48 |

| Ash | 7.40 |

| Calcium b | 0.68 |

| Phosphorus b | 0.35 |

| Ca/P ratio | 1.94 |

| Calculated net energy, Mcal/kg b | |

| Total digestible nutrients, % | 80.44 |

| Maintenance | 1.97 |

| Gain | 1.33 |

| Item | Control | Cr-Yeast | Cr-Met | Cr-Pr | SEM 2 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, kg | ||||||

| Initial | 44.16 | 43.63 | 44.04 | 43.70 | 0.298 | 0.820 |

| Final | 49.90 b | 50.44 ab | 50.87 ab | 52.42 a | 0.631 | 0.025 |

| Average daily gain, kg/d | 0.128 b | 0.151 ab | 0.152 ab | 0.194 a | 0.016 | 0.034 |

| Dry matter intake, kg/d | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 1.31 | 0.034 | 0.583 |

| Gain to feed, kg/kg | 0.102 b | 0.119 ab | 0.122 ab | 0.148 a | 0.011 | 0.045 |

| Observed dietary net energy, Mcal/kg | ||||||

| Maintenance | 1.61 b | 1.72 ab | 1.77 ab | 1.91 a | 0.068 | 0.041 |

| Gain | 1.01 b | 1.10 ab | 1.14 ab | 1.26 a | 0.060 | 0.046 |

| Observed to expected dietary net energy ratio | ||||||

| Maintenance | 0.82 b | 0.87 ab | 0.90 ab | 0.97 a | 0.046 | 0.042 |

| Gain | 0.76 b | 0.82 ab | 0.86 ab | 0.95 a | 0.045 | 0.046 |

| Item | Control | Cr-Yeast | Cr-Met | Cr-Pr | SEM 2 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty body weight, kg | 43.06 c | 44.75 b | 44.84 b | 45.67 a | 0.475 | 0.029 |

| Organ, g/kg empty body weight | ||||||

| Stomach complex | 27.71 | 28.00 | 27.58 | 29.25 | 0.932 | 0.730 |

| Large intestine | 13.39 | 13.36 | 15.80 | 16.55 | 2.058 | 0.858 |

| Small intestine | 18.75 | 19.52 | 20.29 | 20.41 | 0.917 | 0.783 |

| Skin | 162.88 | 171.04 | 170.03 | 174.07 | 7.660 | 0.406 |

| Limbs | 28.32 | 26.00 | 25.80 | 25.29 | 1.022 | 0.513 |

| Head | 41.84 | 41.79 | 39.28 | 41.87 | 1.367 | 0.685 |

| Heart | 5.06 | 4.93 | 5.30 | 5.24 | 0.355 | 0.605 |

| Lungs | 20.34 | 23.28 | 22.35 | 21.10 | 0.912 | 0.284 |

| Liver | 20.12 | 19.76 | 20.30 | 20.94 | 0.769 | 0.893 |

| Spleen | 1.58 | 1.67 | 1.95 | 2.20 | 0.195 | 0.277 |

| Kidney | 2.74 | 2.62 | 2.68 | 2.54 | 0.159 | 0.952 |

| Testicles | 17.83 | 16.53 | 17.76 | 19.79 | 0.927 | 0.292 |

| Omental fat | 18.05 a | 13.58 b | 15.19 b | 14.97 b | 1.007 | 0.034 |

| Mesenteric fat | 16.80 a | 15.56 b | 15.64 b | 15.57 b | 0.878 | 0.042 |

| Visceral fat | 34.85 a | 29.13 b | 30.83 b | 30.54 b | 0.976 | 0.034 |

| Perirenal fat | 18.93 a | 10.48 b | 13.77 b | 11.53 b | 0.987 | 0.028 |

| Item | Control | Cr-Yeast | Cr-Met | Cr-Pr | SEM 2 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound measurements | ||||||

| Rib fat thickness, mm | 3.97 a | 3.55 ab | 3.36 b | 3.22 b | 0.017 | 0.024 |

| Rump fat thickness, mm | 4.28 a | 4.04 ab | 3.78 b | 3.74 b | 0.016 | 0.048 |

| Longissimus lumborum muscle area, cm2 | 13.61 | 13.42 | 13.74 | 12.45 | 0.915 | 0.284 |

| Carcass characteristics | ||||||

| Hot carcass weight, kg | 24.25 b | 25.18 ab | 25.25 ab | 25.51 a | 0.276 | 0.031 |

| Cold carcass weight, kg | 23.49 | 24.38 | 24.54 | 24.73 | 0.276 | 0.674 |

| Dressing, % | 54.84 | 54.70 | 53.50 | 54.9 | 0.891 | 0.221 |

| Cooling loss, % | 2.82 | 3.25 | 2.92 | 3.14 | 0.133 | 0.131 |

| Carcass length, cm | 68.83 | 68.83 | 68.31 | 68.46 | 0.783 | 0.445 |

| Leg circumference, cm | 39.91 | 39.86 | 40.35 | 40.59 | 1.204 | 0.798 |

| Chest circumference, cm | 19.60 | 19.74 | 19.64 | 18.80 | 0.557 | 0.145 |

| Shoulder composition, % | ||||||

| Muscle | 61.45 b | 64.77 a | 63.54 ab | 65.65 a | 0.768 | 0.003 |

| Fat | 19.64 a | 15.68 b | 16.32 ab | 14.43 b | 0.841 | 0.018 |

| Muscle/Fat ratio | 3.01 b | 4.27 a | 3.69 ab | 4.53 a | 0.394 | 0.045 |

| Item | Control | Cr-Yeast | Cr-Met | Cr-Pr | SEM 2 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cuts, % of cold carcass weight | ||||||

| Forequarter | 54.21 | 54.12 | 53.31 | 55.17 | 0.861 | 0.859 |

| Hindquarter | 44.85 | 44.45 | 43.61 | 44.31 | 0.837 | 0.957 |

| Neck | 7.72 | 7.40 | 7.42 | 7.95 | 0.404 | 0.468 |

| Shoulder IMPS206 | 9.13 | 9.46 | 9.76 | 10.20 | 0.309 | 0.416 |

| Shoulder IMPS207 | 17.14 | 17.20 | 17.05 | 17.37 | 0.358 | 0.845 |

| Rack IMPS204 | 6.92 a | 6.82 ab | 5.98 b | 6.08 b | 0.294 | 0.041 |

| Breast IMPS209 | 3.64 | 3.99 | 4.08 | 3.98 | 0.238 | 0.267 |

| Ribs IMPS209A | 6.00 | 5.76 | 5.61 | 5.62 | 0.211 | 0.359 |

| Loin IMPS231 | 6.90 | 6.60 | 7.00 | 6.92 | 0.336 | 0.621 |

| Flank IMPS232 | 7.49 | 7.48 | 7.54 | 7.29 | 0.362 | 0.938 |

| Leg IMPS233 | 30.46 | 30.36 | 29.54 | 30.08 | 0.557 | 0.432 |

| Meat characteristics | ||||||

| pH24h | 5.57 | 5.49 | 5.52 | 5.46 | 0.100 | 0.254 |

| Purge loss24h, % | 3.12 | 3.12 | 4.12 | 4.12 | 0.790 | 0.451 |

| Cook loss, % | 27.37 | 30.19 | 28.13 | 29.20 | 0.990 | 0.841 |

| Water-holding capacity, % | 26.44 b | 29.08 b | 31.31 ab | 33.50 a | 1.650 | 0.014 |

| Warner-Bratzler shear force, kg/cm2 | 3.65 | 3.05 | 3.19 | 3.28 | 0.280 | 0.654 |

| Item | Control | Cr-Yeast | Cr-Met | Cr-Pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing practice costs, USD/Lamb 2 | ||||

| Preventative health | $0.43 | $0.43 | $0.43 | $0.43 |

| Deworming | $0.35 | $0.35 | $0.35 | $0.35 |

| Ear tag | $0.27 | $0.27 | $0.27 | $0.27 |

| Subtotal | $1.05 | $1.05 | $1.05 | $1.05 |

| Feed costs, $/lamb | ||||

| Fed 3 | $15.48 | $15.73 | $15.44 | $16.30 |

| Cr-Yeast supplementation 4 | - | $0.23 | - | - |

| Cr-Met supplementation 4 | - | - | $0.28 | - |

| Cr-Pr supplementation 4 | - | - | - | $0.14 |

| Subtotal | $15.48 | $15.96 | $15.71 | $16.43 |

| Total cost 5 | $16.53 | $17.01 | $16.76 | $17.48 |

| Income selling lamb, USD/Lamb | ||||

| Income 6 | $27.44 | $32.53 | $32.65 | $41.70 |

| Net income 7 | $10.91 | $15.52 | $15.89 | $24.22 |

| Difference 8 | - | $4.62 ** | $4.98 ** | $13.32 *** |

| Cost of gain, $/kg 9 | $2.88 | $2.50 ** | $2.45 ** | $2.00 *** |

| Income selling carcass, USD/carcass | ||||

| Income 10 | $30.94 | $36.60 | $35.92 | $47.08 |

| Net income 11 | $14.41 | $19.59 ** | $19.16 ** | $29.60 *** |

| Difference 12 | - | $5.17 ** | $4.75 ** | $15.19 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera-Villegas, A.; Ríos, A.; Sánchez-Barbosa, O.Y.; Carrillo-Muro, O.; Hernández-Briano, P.; Plascencia, A.; Martínez-Guerrero, O.; Lazalde-Cruz, R. Organic Chromium Sources as a Strategy to Improve Performance, Carcass Traits, and Economic Return in Lambs Finishing at Heavier Weights. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242559

Rivera-Villegas A, Ríos A, Sánchez-Barbosa OY, Carrillo-Muro O, Hernández-Briano P, Plascencia A, Martínez-Guerrero O, Lazalde-Cruz R. Organic Chromium Sources as a Strategy to Improve Performance, Carcass Traits, and Economic Return in Lambs Finishing at Heavier Weights. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242559

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera-Villegas, Alejandro, Alejandra Ríos, Oliver Yaotzin Sánchez-Barbosa, Octavio Carrillo-Muro, Pedro Hernández-Briano, Alejandro Plascencia, Octavio Martínez-Guerrero, and Rosalba Lazalde-Cruz. 2025. "Organic Chromium Sources as a Strategy to Improve Performance, Carcass Traits, and Economic Return in Lambs Finishing at Heavier Weights" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242559

APA StyleRivera-Villegas, A., Ríos, A., Sánchez-Barbosa, O. Y., Carrillo-Muro, O., Hernández-Briano, P., Plascencia, A., Martínez-Guerrero, O., & Lazalde-Cruz, R. (2025). Organic Chromium Sources as a Strategy to Improve Performance, Carcass Traits, and Economic Return in Lambs Finishing at Heavier Weights. Agriculture, 15(24), 2559. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242559