Abstract

The individual application of salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (ST-PGPR) or organic amendments exhibits certain limitations in remediating saline-alkali soils. This study developed a co-application treatment by combining a functionally complementary ST-PGPR consortium (Bacillus velezensis and Bacillus marisflavi) with optimized organic amendments (biochar at 22.5 t·ha−1 and sheep-manure organic fertilizer at 7.5 t·ha−1) to enhance soil quality and wheat growth. Compared with the control, the combination of the ST-PGPR consortium with organic amendments significantly reduced soil electrical conductivity by 52.69%. while soil organic matter, alkaline nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium increased by 54.37%, 7.68%, 11.85%, and 39.57%, respectively (p < 0.05). The activities of sucrase, urease, and catalase also increased by 147.69%, 28.56%, and 30.26%, respectively (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the combined treatment significantly promoted wheat growth, increasing plant height, root length, and fresh weight by 12.11%, 26.60%, and 35.00%, respectively (p < 0.05), while alleviating osmotic and oxidative stress. β-diversity analysis revealed distinct microbial community compositions across treatments, and microbial composition indicated that Actinobacteriota and Starmerella were enriched under the co-application. Additionally, the co-application significantly enhanced the complexity and interconnectivity of the bacterial network, while reducing the stability of the fungal network. Partial least squares path and random forest models identified soil chemical properties as the key factors driving wheat growth. This synergistic system presents a promising and sustainable strategy for remediating saline-alkali soils and enhancing crop productivity.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), one of China’s primary staple crops, is closely linked to national food security and agricultural development [1]. However, in major wheat-producing regions, particularly the arid and semi-arid areas of Northwest, North, and Northeast China, soil salinization has become a prominent barrier to achieving yield potential, seriously restricting wheat growth and final productivity [2,3,4]. China is estimated to contain about 99.13 million hm2 of saline-alkali land, with more than 10% of arable land affected and the extent continuing to expand annually [5]. Saline-alkali soils are characterized by high concentrations of soluble salts (e.g., Na+ and Cl−) that induce osmotic stress and ion toxicity, accompanied by soil compaction, poor nutrient availability, and functional deterioration of microbial communities [6]. These detrimental conditions restrict plant growth, resulting in yield losses. Consequently, the development of efficient, environmentally friendly, and sustainable strategies for ameliorating saline–alkali soils have become an urgent requirement for safeguarding China’s grain production and ecological security.

Among the various strategies for saline-alkali soil remediation, bioremediation and the application of organic amendments have attracted increasing attention due to their strong environmental compatibility and sustainability [7,8]. ST-PGPR can alleviate soil salinity and alkalinity, enhance nutrient availability, and improve soil fertility through mechanisms such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and exopolysaccharides (EPS) production, thereby enhancing nutrient use efficiency and improving the rhizosphere microenvironment [9,10,11]. For example, Bacillus subtilis has been reported to significantly increase nutrient availability and soil enzyme activities while reducing soil pH and salinity in cotton-growing systems [12]. Mukherjee et al. showed that the halophilic rhizobacterium Halomonas sp. Exo1 produces EPS, solubilizes inorganic phosphate, and synthesizes indole-3-acetic acid, thereby improving rice growth and N and P uptake under salt stress [13]. Meanwhile, organic amendments such as biochar and organic fertilizer represent another major approach to saline-alkali soil amelioration by physical adsorption, nutrient supplementation, and soil structure improvement [14,15]. The porous structure of biochar enhances cation exchange capacity, immobilizes excess salt ions, and improves soil aeration [16,17]. Previous studies have confirmed that the sole application of biochar can increase wheat yield in saline-alkali soils by 8.4–8.6% [18]. Organic fertilizers also replenish soil organic matter, enrich microbial carbon sources, and enhance soil enzyme activities and nutrient availability [19].

Despite the emerging potential of ST-PGPR and organic amendments, their individual application still presents considerable limitations. For ST-PGPR, the efficacy is highly dependent on their ability to colonize and survive in soil, whereas the extreme conditions of saline-alkali soils often impede bacterial survival and restrict functional expression [20]. For organic amendments, the ameliorative effect of biochar is strongly dosage-dependent, and excessive application may increase soil pH and thereby exacerbate alkaline stress [21]. Likewise, the sole use of organic fertilizers is constrained by unbalanced nutrient release [22]. In recent years, several studies have attempted to combine ST-PGPR with biochar, revealing a synergistic interaction that enhances soil fertility and promotes crop growth. For instance, Hou et al. demonstrated a pronounced synergy between Azotobacter chroococcum and biochar, with the combined treatment producing greater increases in soil organic carbon and nitrate nitrogen than either amendment applied alone [23]. Malik et al. further showed that co-application of biochar with a salt-tolerant phosphate-solubilizing Bacillus strain increased soil available phosphate by 37–53%, enhanced wheat grain yield by 34–37% compared with the single-amendment treatments. [24]. However, critical gaps remain in existing combined-application studies: (i) microbial consortia are often assembled from single functional strains or simple mixtures, lacking rational design based on complementary functions such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and EPS production; (ii) organic amendments are typically limited to a single type, and the optimal biochar-organic fertilizer ratios and their interactions with ST-PGPR remain unclear; and (iii) systematic mechanistic elucidation of how such synergistic systems improve saline–alkali soil microenvironments is still insufficient.

This study aims to develop a synergistic remediation system integrating functionally complementary ST-PGPR consortium with optimized organic amendments, and to elucidate its regulatory effects and mechanisms on saline-alkali soil microenvironments and wheat performance. The specific objectives are as follows: (1) to screen and construct a functionally complementary salt-tolerant microbial consortium; (2) to optimize the application ratio of biochar and organic fertilizer; (3) to explore the comprehensive effects of the synergistic system on the micro-environment of saline-alkali soils and wheat growth; (4) to comprehensively elucidate the synergistic mechanisms of the system, including soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, microbial community structure, and network interactions. This study is expected to provide a ternary composite remediation approach, offering theoretical and data support for the development of efficient ecological restoration technology for saline-alkali soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Materials

Saline-alkaline soil for the pot experiment was collected from Guangming Village, Xingongzhong Town, Bayannur, Inner Mongolia, China (108°16′ E, 41°05′ N). The basic properties of the soil were: EC 1826 µS·cm−1, pH 8.13; SOM, TN, TP, and TK contents were 7.36, 0.39, 0.66, and 19.11 g·kg−1, respectively; AK, AP, and AN content were 197.83, 4.44, and 23.74 mg·kg−1, respectively. Corn-straw biochar was purchased from Zhongda Hanxing Environmental Remediation Co., Ltd. (Tangshan, China), with a carbon content of 80.6%, ash content of 10–20%, and pH of 9.69. The organic fertilizer was mainly processed from sheep manure, containing 33.7% organic matter, 2.48% N, 1.91% P2O5, and 2.37% K2O, respectively.

2.2. Isolation, Purification, and Characterization of Salt-Tolerant Strains

2.2.1. Isolation and Purification

Soil samples were collected from Wuyuan County, Haixing County and Huanghua City. Bacterial isolation was performed using the serial dilution and spread plate method on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plates. After incubation at 28 °C for 3 days, colonies exhibiting distinct morphologies were selected for purification. The strains were inoculated into LB medium supplemented with 5% NaCl (w/v) and pH 9.0 to screen for salt-alkali-tolerant strains.

2.2.2. Assessment of Growth-Promoting Characteristics of Strains

The strains were cultured in inorganic phosphorus, organic phosphorus, nitrogen-fixing, IAA-producing, and exopolysaccharide (EPS)-producing media to evaluate their growth-promoting characteristics. For inorganic and organic phosphorus assays, strains were incubated at 28 °C for 7 days, and the phosphate-solubilizing ability was indicated by the ratio of transparent zone diameter to colony diameter (D/d). Growth on nitrogen-free medium was observed after 7 days. For IAA quantification, strains were inoculated at 5% (v/v) into specific media and shaken at 28 °C for 48 h. The supernatant was reacted with Salkowski reagent, and IAA concentration was determined by measuring OD530 [25]. For EPS production, strains were grown similarly in EPS medium. Biomass was determined by dry weight of pelleted cells. EPS was precipitated from the supernatant using ethanol, dried, and weighed to calculate the yield [26].

2.3. Construction and Molecular Identification of Microbial Consortium

The purified strains were individually inoculated into LB liquid medium and cultured for 24 h. After centrifugation, the cells were collected and resuspended in sterile water to adjust the bacterial suspension to an OD600 of 0.1. Wheat seeds were planted in Petri dishes containing 35 g of vermiculite, and 5 mL of bacterial suspension was added, with an equal volume of sterile water serving as the control. Before sowing, wheat seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min and 2% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, then rinsed with sterile distilled water. Vermiculite was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min and cooled to room temperature before use. Each treatment was performed in triplicate, with 10 seeds per Petri dish, and watered with distilled water containing 1% NaCl. After 10 days of cultivation, plant height, root length, and fresh weight were measured. Based on the wheat growth promotion results, four of the most effective strains were selected and combined in equal proportions to form different microbial consortia (Table 1). A secondary screening was then performed using the same method, and the impact of each combination on wheat growth was assessed to identify the optimal core microbial consortium. For molecular identification, 16S rRNA gene analysis was performed, sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree analysis were carried out according to [27].

Table 1.

Designed groups of bacterial consortia.

2.4. Pot Experiments

The pot experiment was performed in Hebei University of Science and Technology, China (114°30′ E, 37°58′ N) in 2024. Different application rates of organic amendments were employed: (1) biochar applied at 15, 45, and 75 t·ha−1; (2) organic fertilizer applied at 7.5, 15, and 22.5 t·ha−1; (3) biochar and organic fertilizer applied at 45 + 15, 22.5 + 7.5, 30 + 5, and 15 + 10 t·ha−1 (BF1–BF4). A treatment without organic amendments served as the control. After 20 days, plant height, fresh weight, and chlorophyll content (SPAD) were measured. The optimal application rate of organic amendments was selected based on the overall growth performance of wheat.

Based on the optimal application rate of organic amendments determined in the first pot experiment, a second pot experiment was conducted to evaluate the synergistic effects between the microbial consortium and the optimized organic amendment blend. Four treatment groups were established to assess the effects. The treatments were as follows: (1) no organic amendments or microbial consortium applied (CK); (2) 3.2 mL (107 CFU/mL) of microbial consortium (T1); (3) organic amendments applied at optimized rates (T2); (4) 3.2 mL of microbial consortium + organic amendments applied at optimized rates (T3). Each pot contained 800 g of soil, with the soil moisture content maintained at 60% of the maximum capacity using distilled water. The total nitrogen input was 207.5 kg N·hm−2. Each treatment had 10 replicates. After 20 days, wheat growth traits and antioxidant enzyme activities were measured; bulk soil samples were collected, with part stored at −80 °C for high-throughput sequencing and the other part air-dried for measuring soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities.

2.5. Measurement Methods

2.5.1. Plant Growth and Physiological Indicators

Plant height and root length were measured using a vernier caliper. Fresh weight of the aboveground parts was weighed using an analytical balance. The chlorophyll of leaves was measured with a handheld chlorophyll analyzer (LD-YD, Laiende, Weifang, China). The activities of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) and proline (PRO) were determined as described [28].

2.5.2. Soil Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured using a pH meter (PB-10, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) and a conductivity meter (DDS-307A, Leici, Shanghai, China), respectively, with a soil-to-water ratio of 1:5 (w/v). Soil organic matter (SOM) was determined using the potassium dichromate oxidation method with external heating. Alkaline nitrogen (AN) was measured by alkaline diffusion. Available phosphorus (AP) was measured by sodium bicarbonate extraction and molybdenum-antimony colorimetry. Available potassium (AK) was determined by ammonium acetate extraction and flame photometry [29]. Total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and total potassium (TK) were measured by the Kjeldahl method, sodium hydroxide fusion-molybdenum-antimony colorimetry, and flame photometry, respectively [30]. The activities of urease (UE), catalase (CAT), sucrose enzyme (SC) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were determined as described [4].

2.5.3. Soil DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

Soil total DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 region was amplified using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The fungal ITS1 region was amplified using primers ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). PCR products were purified and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with paired-end sequencing. Raw data were quality-filtered and chimeras were removed, followed by ASV clustering and species annotation using QIIME2 (v2022.8). The raw 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession numbers PRJNA1358025 and PRJNA1358235, respectively.

2.6. Data Analysis

The microbial community structure was visualized by Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distance. The microbial co-occurrence network was constructed using the “ggClusterNet” package and visualized in Gephi (v0.10.1). The correlation between environmental factors and microbial communities was analyzed using the Mantel test. Partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) was used to analyze the relationships among soil properties, microbial communities, and wheat growth. Random forest model was used to identify the dominant factors influencing wheat growth (“rfPermute” package). All data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS (v26.0), with significant differences determined by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Assembly of Functionally Complementary Microbial Consortium

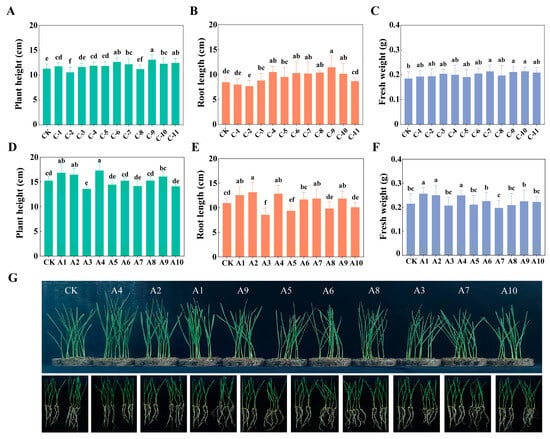

A total of 11 salt-tolerant strains were isolated from saline-alkali soils (labeled C-1 to C-11), and the morphological characteristics of the strains are shown in Figure S1. Table 2 presents the growth-promoting characteristics of these strains. Seven strains (C-3, C-4, C-6, C-7, C-9, C-10, and C-11) demonstrated more noticeable growth-promoting effects, with plant height, fresh weight, and root length increase rates ranging from 5.1% to 15.6%, 7.9% to 15.5%, and 2.2% to 38.4%, respectively (Figure 1A–C). Based on the functional complementarity principle, microbial consortia were assembled using strains C-3, C-6, C-9, and C-11, collectively covering the function of growth-promoting. The four strains were selected for their distinct, complementary functions: C-9 for nitrogen fixation, C-11 for organic phosphorus solubilization, and C-3 and C-6 for high production of IAA and EPS, respectively. Additionally, C-6 demonstrated inorganic phosphorus solubilization.

Table 2.

Assessment of plant growth-promoting traits of the bacterial strains.

Figure 1.

Effects of salt-tolerant strains on plant height (A), root length (B), fresh weight (C) of wheat, and of bacterial consortia on plant height (D), root length (E), fresh weight (F) of wheat and phenotype of wheat growth (G). Bars and error bars show means ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 10). Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Ducan test).

The results of the vermiculite-plate wheat growth assay revealed that the A1, A2, and A4 combinations significantly enhanced wheat height by 8.07–13.52% and root length by 14.55–20.84% (p < 0.05) compared with the control (Figure 1D–F). Notably, the A4 consortium integrated two key nutrient acquisition functions: nitrogen fixation (C-9) and organic phosphorus solubilization (C-11), and thus was selected for subsequent experiments due to its functional complementarity. The phylogenetic tree revealed that C-6 clustered with Bacillus velezensis and C-9 clustered with Bacillus marisflavi (Figure S2).

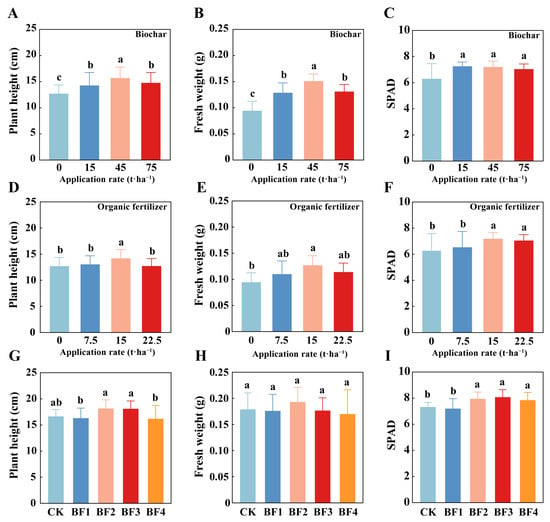

3.2. Optimization of the Co-Application of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer

The optimization results for the single application of biochar (Figure 2A–C) indicated that all three biochar treatments significantly enhanced wheat plant height, fresh weight, and SPAD values (p < 0.05). Among these, the application of biochar at 45 t·ha−1 exhibited the most significant effect, with plant height, fresh weight, and SPAD values increasing by 23.92%, 66.67%, and 14.29%, respectively, compared with the no-biochar treatment. The optimization results for the single application of organic fertilizer (Figure 2D–F) showed that the application of organic fertilizer at 15 t·ha−1 resulted in the greatest improvement, with plant height, fresh weight, and SPAD values increasing by 11.64%, 44.44%, and 14.13%, respectively, compared with the no-organic fertilizer treatment (p < 0.05). Subsequently, based on the optimized single applications, the combined effect of biochar and organic fertilizer was further explored (Figure 2G–I). The results showed that the BF2 and BF3 treatments had the best overall effects, with SPAD values increasing by 8.46% and 10.23%, respectively, compared to CK (p < 0.05). However, considering the substantially higher cost of biochar compared to organic fertilizer, the BF2 treatment was identified as the optimal mixed ratio, as it provides both effective results and economic feasibility. Consequently, the BF2 application rate (biochar 22.5 t·ha−1; organic fertilizer 7.5 t·ha−1) was adopted for subsequent synergistic experiments with the microbial consortium.

Figure 2.

Effects of different application rates of biochar (A–C), organic fertilizer (D–F), and organic amendments (G–I) on plant height, fresh weight, and chlorophyll content in wheat. Bars and error bars show means ± SD (n = 10). Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Ducan test).

3.3. Effects of Synergistic Treatment on Soil Properties and Plant Responses

3.3.1. Changes in Soil Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

The effects of different treatments on soil chemical properties are shown in Table 3. Compared with the control group, none of the three treatments reduced soil pH. In contrast, all treatments significantly reduced soil EC, with the lowest EC observed under T3, which was 52.69% lower than CK (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, T3 treatments significantly improved SOM, AN, AP, and AK, which increased by 54.37%, 7.68%, 11.85%, and 39.57%, respectively, compared with CK (p < 0.05). Overall, T3 treatment not only reduced soil EC but also improved plant-available nutrients, showing the most significant ameliorative effect on the amelioration of saline-alkali soil chemical properties. For soil enzyme activities, T3 treatment significantly enhanced several key enzymes (Table 4). The SC activity presented a 147.69% increase compared to CK (p < 0.05), which was substantially greater than the increases observed in T1 (86.15%) and T2 (12.31%). The UE activity in T3 was significantly increased by 28.56% compared to CK (p < 0.05), while T1 and T2 showed no significant difference from CK. Regarding the alleviation of oxidative stress, the CAT activity in T2 and T3 treatments was significantly higher than that in CK (p < 0.05), with increases of 14.34% and 30.26%, respectively.

Table 3.

Effects of different treatments on soil chemical properties.

Table 4.

Effects of different treatments on soil enzyme activities.

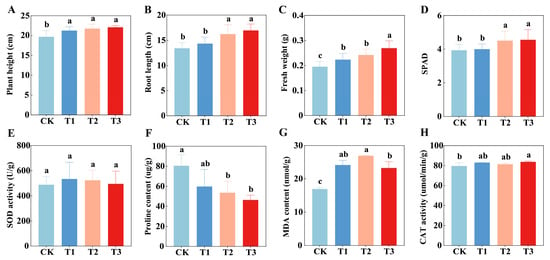

3.3.2. Wheat Growth Performance and Physiological Resistance

Wheat growth and physiological indicators reflect the positive effects of soil environment improvement on plants. In terms of growth parameters (Figure 3A–C), treatments T1, T2, and T3 significantly enhanced wheat plant height, root length, and fresh weight (p < 0.05). Among them, T3 treatment showed the best results, with plant height, root length, and fresh weight increasing by 12.11%, 26.60%, and 35.00%, respectively, compared to CK. Overall, T3 tended to promote wheat growth more effectively than the single-component treatments. The chlorophyll content (Figure 3D) was significantly higher in T2 and T3 treatments than in CK and T1 treatments (p < 0.05), with T3 exhibiting the highest value, indicating that the organic amendments input and synergistic treatment effectively enhanced the photosynthetic capacity of wheat.

Figure 3.

Effects of different treatments on growth parameters (A–D) and antioxidant enzyme activities (E–H) of wheat. Bars and error bars show means ± SD (n = 5). Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Ducan test).

Physiological indicators revealed the plants’ response to salinity and alkalinity stress (Figure 3E–H). The CAT activity in T3 treatment was significantly higher than in CK (p < 0.05), with an increase of 5.15%. PRO content was significantly lower in T2 and T3 treatments compared to CK (p < 0.05), decreasing by 33.39% and 42.24%, respectively. MDA content in T1, T2, and T3 treatments was significantly higher than in CK (p < 0.05). Combined with growth parameters, this accumulation of MDA did not inhibit wheat growth. The changes in SOD activity showed no significant differences among the treatments.

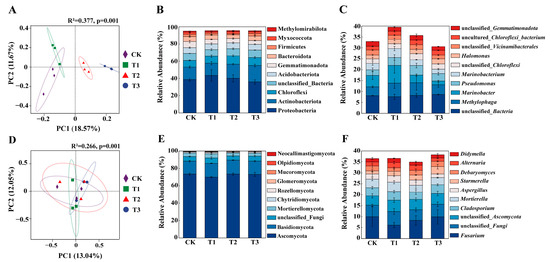

3.4. Dynamics of Soil Microbial Community Structure

3.4.1. Microbial Diversity and Composition

PCoA revealed distinct clustering of microbial communities according to treatment (Figure 4A,D). The bacterial and fungal community compositions were significantly divergent across treatments. In the bacterial community, PC1 and PC2 axes together explained 30.24% of the variation, and the differences between treatments were highly significant (R2 = 0.377, p = 0.001). Similarly, the fungal community displayed highly significant inter-group differences (R2 = 0.266, p = 0.001), with the PC1 and PC2 axes together explaining 25.09% of the variation. These results suggest that the synergistic treatment significantly impacted the microbial community structure of saline—alkaline soil.

Figure 4.

Soil microbial β-diversity for bacteria (A), dominant bacterial phyla (B), and dominant bacterial genera (C); β-diversity for fungi (D), dominant fungal phyla (E), and dominant fungal genera (F).

In the bacterial community, the dominant bacterial phyla across all treatments were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Chloroflexi (Figure 4B). The relative abundance of Actinobacteriota in T3 was significantly higher than in CK (p < 0.05). In the fungal community, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominant phylum (Figure 4E). The T3 treatment significantly enriched Starmerella (Figure 4F), with its relative abundance being significantly higher than the CK treatment (p < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was observed between T1 and T2 treatments and CK.

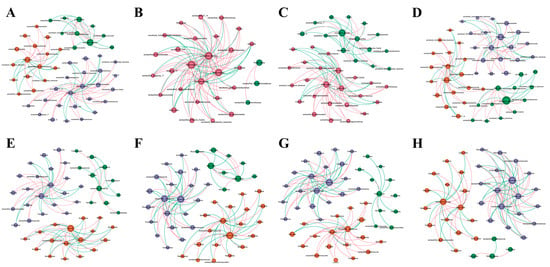

3.4.2. Microbial Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

Co-occurrence network and topological analysis explored the impact of different treatments on microbial interactions in saline-alkali soil (Figure 5 and Table S1). Compared to T1 and T2 treatments, T3 showed an increase in node count, modularity, and average path length. Moreover, the positive correlation ratio in T3 was 65%, which was higher than CK (62%), T1 (34%) and T2 (42%). This indicates that T3 can maintain microbial community diversity, enhance cooperation among bacteria, and improve the network structure and interaction quality. For fungi, T3 had the fewest nodes, lowest modularity, average path length and average clustering coefficient. This suggests that the combination of organic amendments and microbial consortium appeared to reduce the complexity and stability of the fungal community structure. Additionally, T3 treatment slightly weakened the positive correlation in the fungal network while enhancing the negative correlation. This suggests that T3 treatment might intensify resource competition among fungal groups.

Figure 5.

Bacterial co-occurrence network: CK (A), T1 (B), T2 (C), T3 (D); fungal co-occurrence networks: CK (E), T1 (F), T2 (G), T3 (H).

Zi-Pi analysis was performed to identify keystone species (Table S2). For bacteria, the CK, T1, T2, and T3 samples contained 4, 0, 3, and 4 module hubs, respectively. Notably, Methylophaga was a unique module hub shared by T2 and T3, distinct from CK, potentially linked to the utilization of intermediate products in organic matter degradation (e.g., methanol). For fungi, the CK, T1, T2, and T3 samples contained 3, 4, 3, and 2 module hubs, respectively. These core species play important roles in the network, and their changes reflect the restructuring of the microbial community structure and functional core due to the treatments.

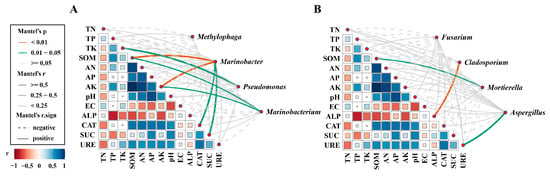

3.4.3. Correlation Between Key Microbial Genera and Environmental Factors

The Mantel test revealed the correlation between key microbial genera and soil environmental factors (Figure 6). For bacteria (Figure 6A), the abundance of Marinobacter was significantly positively correlated with SOM and AK (p < 0.01), as well as with the activities of SC and CAT (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the abundance of Pseudomonas was significantly positively correlated with TK (p < 0.05). For fungi (Figure 6B), the abundance of Cladosporium was highly positively correlated with ALP activity (p < 0.01), Aspergillus showed a significant positive correlation with UE activity. and Mortierella was significantly positively correlated with SOM (p < 0.05). Overall, these results indicate close associations between specific bacterial and fungal genera and soil environmental factors.

Figure 6.

Mantel test assessing the correlation between environmental variables and keystone bacterial (A) and fungal (B) genus.

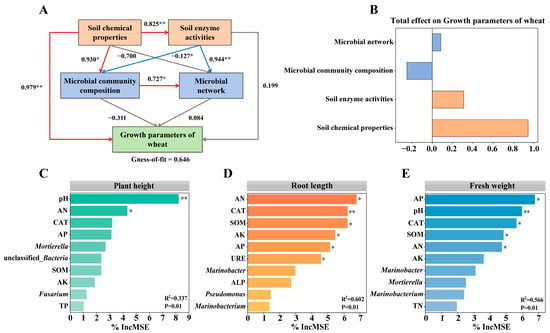

3.5. Identification of Key Drivers of Wheat Growth Enhancement

The results of partial least squares path model (PLS-PM) analysis demonstrated that the addition of microbial consortium and organic amendments significantly affected wheat growth in saline-alkaline soil (Figure 7A). The PLS-PM analysis showed that soil chemical properties and enzyme activities strongly influenced the microbial community composition and network, which in turn impact wheat growth parameters. Notably, soil chemical properties exerted the strongest positive influence on wheat growth (total effect = 0.9435), followed by soil enzyme activities (total effect = 0.3099). Although both microbial community composition and network contributed to wheat growth, their effects were weaker compared to soil chemical properties and enzyme activities.

Figure 7.

Partial least squares path modeling (A,B) and random forest analysis (C–E). Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Following the identification of soil properties as the primary driving factors in PLS-PM, the significance of each factor was further assessed and quantified using random forest model (Figure 7C–E). AN, AP, SOM, and pH were identified as the primary drivers of wheat growth. Moreover, the CAT activity represented another critical factor influencing wheat growth. This result supplements the PLS-PM model’s conclusion that soil physicochemical properties are the main drivers and indicates that, in a synergistic improvement system, targeting these specific key factors, in addition to overall soil amelioration, can more effectively promote wheat growth.

4. Discussion

This study constructed a functionally complementary salt-tolerant microbial community (Bacillus velezensis and Bacillus marisflavi) combined with optimized organic amendments, revealing the synergistic effects of this system on the micro-environment of saline-alkali soil and wheat growth. The results indicate that the “microbial consortium-organic amendments” synergistic treatment (T3) significantly outperforms individual treatments (T1 and T2) in improving soil physical and chemical properties, enhancing enzyme activity, promoting wheat growth and stress resistance, and reshaping soil microbial community structure.

4.1. Impact of the Synergistic Treatment on the Soil Microenvironment

The superior performance of the T3 treatment can be attributed to the combined effects of the organic amendments and the functional microbial consortium, improving soil chemical properties and enzyme activities in the saline-alkali soil. Notably, the decrease in EC (52.69%) exceeded the effect reported for single salt-tolerant microorganism treatment (39.7%) [12], further highlighting the advantage of the synergistic treatment. The EPS secreted by microbial consortium not only acted as a binding agent for soil particles but also chelated Na+, directly ameliorating ionic stress and improving soil structure simultaneously [31]. Meanwhile, the porous structure of biochar not only provides a protective niche for microorganisms from salt stress but also effectively adsorbs salt ions such as Na+ [32,33], which primarily contributed to the significant reduction in EC observed in T3 treatment. Soil enzyme activity is a direct indicator of microbial function, reflecting the key role of microorganisms in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling [34]. T3 treatment significantly enhanced the activities of sucrase and urease, indicating that the synergistic treatment facilitated the soil carbon cycling and nitrogen cycling and improved the efficiency of plant nutrient absorption [35,36]. This is consistent with the higher AN content observed under T3 (Table 3). This effect may be partly attributed to the ability of biochar to stabilize extracellular enzymes and maintain higher activities of sucrase and urease over time by providing protective microhabitats and adsorption sites [37]. Additionally, the highest CAT activity in T3 indicated that the synergistic treatment most effectively enhanced the ability to alleviate oxidative stress in the soil.

4.2. Response of Microbial Communities to the Synergistic Treatment

High-throughput sequencing revealed that the T3 treatment not only affected microbial abundance but also altered community structure. PCoA analysis indicated that the T3 treatment significantly impacted the bacterial and fungal community structures. In the bacterial community, Actinobacteriota exhibited notable enrichment under the T3 treatment. Actinobacteriota are key participants in the decomposition of soil organic matter, which helps improve soil fertility and provides nutrients for plant growth [38,39]. Accordingly, the increased relative abundance suggests an enhanced potential for organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, as well as improved soil aggregation and overall soil quality [40,41], indicating that the co-application treatment created a more favorable environment for bacterial survival, providing abundant substrates that significantly enhanced the nutrient cycling potential of the soil. At the fungal level, the specific enrichment of Starmerella under the T3 treatment is of particular significance. This fungal genus is typically associated with environments rich in available carbohydrates [42]. Its increased abundance suggested that the synergistic treatment significantly optimized soil carbon resources. This directly correlates with the notably elevated sucrase activity observed in the T3 treatment (Table 4). The optimization of carbon, facilitated by this treatment, further supported the proliferation of beneficial fungal populations, reinforcing the system’s overall carbon metabolism function.

As revealed by co-occurrence network analysis, the T3 treatment also altered the interactions among microbial taxa. In the bacterial network, T3 treatment showed higher nodes, modularity, and proportions of positive correlations, suggesting enhanced cooperative interactions among bacteria and increased network complexity and stability. These changes may be associated with the input of organic materials and the metabolic activation of functional microbial communities, collectively promoting bacterial colonization and cooperative metabolism. In contrast, the complexity of the fungal network decreased under T3 treatment, with reduced modularity and connectivity, and an increase in negative correlations, suggesting intensified resource competition. As key participants in organic matter decomposition, a simplification of the fungal network may affect the continuity and efficiency of nutrient release [43]. This phenomenon may be related to the preferential utilization of easily degradable carbon sources by bacteria, limiting resource availability for fungi [44], suggesting the need for further attention to the balance between bacterial and fungal functions in synergistic regulation.

Mantel analysis further highlighted associations between dominant bacterial and fungal genera and soil environmental factors (Figure 6). Bacterial genera such as Marinobacter and Pseudomonas were positively correlated with SOM, AK, TK and the activities of SC and CAT, while fungal genera including Cladosporium, Aspergillus and Mortierella were associated with SOM and P-cycling enzyme activities. Pseudomonas have been reported to solubilize potassium from K-bearing minerals, thus facilitating the biogeochemical cycling of potassium in the soil [45]. Mortierella fungi typically show higher abundance in organic-rich soils and can indirectly alter soil nutrient (carbon and nitrogen) transformation capacity and availability by affecting soil fungal community composition and abundance [46]. These patterns suggest that changes in soil nutrient status and enzyme activities under the synergistic treatment are closely linked to shifts in specific bacterial and fungal genera, consistent with a role of the soil microbiota in mediating nutrient availability and stress-related processes in saline-alkali soils [47].

4.3. Plant Response: From Stress Mitigation to Growth Promotion

The successful optimization of the soil microenvironment through synergistic treatments culminated in a significant improvement in wheat growth, with the T3 treatment demonstrating superior efficacy in both stress mitigation and growth promotion. The accumulation of PRO is a typical response of plants to osmotic stress [48]. The significant reduction in PRO content in wheat leaves under the synergistic treatment indicated that the osmotic stress endured by the crop has been alleviated. CAT is responsible for the removal of H2O2, and the increase in CAT activity in the leaves indicates that the plant’s ability to eliminate oxidative stress has been enhanced, enabling better protection against oxidative damage under saline-alkali conditions [49,50]. MDA is a product of lipid peroxidation, and its accumulation is generally associated with stress damage [25]. The observed increase in MDA content in T3 may be linked to highly active metabolism and accelerated lipid turnover in vigorously growing plants [51], rather than solely indicating severe oxidative damage. This suggests that the synergistic treatment overall shifted the plant’s physiological state from “stress resistance survival” to “active growth”.

It is worth emphasizing that, although strain C-5 displayed higher in vitro PGP indices than C-4 (Table 2), wheat seedlings inoculated with C-4 in the vermiculite assay showed better growth performance (Figure 1). Similar discrepancies between in vitro PGP traits and plant responses in gnotobiotic or greenhouse assays have been reported, where isolates with multiple promising PGP traits did not necessarily increase biomass compared with the uninoculated control [52]. This suggests that, beyond the magnitude of PGP traits measured in vitro, factors such as strain–plant compatibility, colonization behavior in the experimental substrate, and dose- or threshold-dependent effects of phytohormones such as IAA are also critical [53], which may explain why C-4 provided a more favorable growth response than C-5 under our experimental conditions.

PLS-PM and random forest analysis further validated the synergistic treatment’s enhanced efficacy from a multivariable statistical perspective. The PLS-PM results underline that the improvement of soil physicochemical properties is the primary and most direct pathway influencing wheat growth. This finding highlights the crucial role of soil chemistry in optimizing the soil microenvironment, directly influencing wheat growth. Additionally, the positive impact on soil enzyme activities indirectly promotes nutrient cycling, further facilitating wheat growth. The random forest model further refined that AN, pH, and CAT activity are the primary factors influencing wheat growth. These insights suggest that a targeted approach, focusing on specific soil factors, alongside general soil improvement, can more effectively enhance wheat growth in different aspects. This approach allows for refined management practices, specifically in saline-alkaline soil, where precise control over limiting factors like nitrogen, phosphorus, and pH can optimize wheat productivity. This comprehensive analysis provides a foundation for advancing soil amelioration strategies aimed at enhancing wheat growth in challenging soil environments.

5. Conclusions

The synergistic application of a salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria consortium combined with optimized organic amendments (biochar and organic fertilizer) significantly improved the remediation of saline-alkali soils and promoted wheat growth. This synergistic system not only enhanced soil chemical properties but also improved key soil enzyme activities related to nutrient cycling and stress mitigation. Additionally, microbial community structure analysis revealed a shift in the microbial community, with an enhanced bacterial network structure. In terms of promoting wheat growth, the synergistic system significantly increased plant height, root length, and fresh weight, while reducing oxidative stress and improving photosynthetic capacity. This study highlights the potential of the combined microbial and organic amendment system as an effective and scalable strategy for soil restoration and sustainable agricultural practices in saline-affected areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242558/s1.

Author Contributions

Y.H. (Yanxia He): Data curation, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. Z.N.: Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. Y.C.: Data curation, Software, Writing—review and editing. X.Y.: Project administration, Software, Writing—review and editing. Y.H. (Yali Huang): Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing—review and editing. C.Z.: Methodology, Resources, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1902602-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available. The bacterial original sequence has been submitted to NCBI with registration number PRJNA1358025. The fungal original sequence has been submitted to NCBI with registration number PRJNA1358235.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gong, K.; Rong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Duan, F.; Li, X.; He, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, S.; Feng, H.; et al. Efficient agronomic practices narrow yield gaps and alleviate climate change impacts on winter wheat production in China. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, M.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y. Improving Winter Wheat Yield Estimation Under Saline Stress by Integrating Sentinel-2 and Soil Salt Content Using Random Forest. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X. The response strategies to saline-alkali stress in wheat: Soil improvement, agronomic management, salt-tolerant variety breeding, and biochemical regulation. Geogr. Bull. 2025, 4, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Piao, J.L.; Miao, S.H.; Che, W.K.; Li, X.; Li, X.B.; Shiraiwa, T.; Tanaka, T.; Taniyoshi, K.; Hua, S.; et al. Long-term effects of biochar one-off application on soil physicochemical properties, salt concentration, nutrient availability, enzyme activity, and rice yield of highly saline-alkali paddy soils: Based on a 6-year field experiment. Biochar 2024, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Xing, S.; Song, J.; Lu, S.; Ling, L.; Qu, L. Transcriptome Reveals the Differential Regulation of Sugar Metabolism to Saline–Alkali Stress in Different Resistant Oats. Genes 2025, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; She, D.; Fei, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, L. Three-dimensional fractal characteristics of soil pore structure and their relationships with hydraulic parameters in biochar-amended saline soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, P.; Wu, X.; Zhu, M.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Kang, J.; Chen, J.; Tong, L.; Ding, R. Optimizing cotton growth in saline soil: Compound microbial agent modulates indigenous bacteria to enhance photosynthesis and vegetative-reproductive balance. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeknassi, M.; Elghali, A.; de Carvalho, H.W.P.; Laamrani, A.; Benzaazoua, M. A review of organic and inorganic amendments to treat saline-sodic soils: Emphasis on waste valorization for a circular economy approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, W.J.; Wang, C.X.; Ji, L.; Han, K.; Gong, J.H.; Dong, S.Y.; Wang, H.L.; Zhu, X.M.; Du, B.H.; et al. Growth-promoting effects of self-selected microbial community on wheat seedlings in saline-alkali soil environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1464195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, J.; Alikhani, H.A.; Etesami, H.; Pourbabaei, A.A. Improved Phosphorus Uptake by Wheat Plant (Triticum aestivum L.) with Rhizosphere Fluorescent Pseudomonads Strains Under Water-Deficit Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Deka, S. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria-alleviators of abiotic stresses in soil: A review. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Li, P.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Meng, Q.; Ye, F.; Yin, W. Study of the mechanism by which Bacillus subtilis improves the soil bacterial community environment in severely saline-alkali cotton fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Mitra, A.; Roy, M. Halomonas rhizobacteria of Avicennia marina of Indian Sundarbans promote rice growth under saline and heavy metal stresses through exopolysaccharide production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.M.; Zhang, S.R.; Liu, L.; Wu, L.P.; Ding, X.D. Combined organic amendments and mineral fertilizer application increase rice yield by improving soil structure, P availability and root growth in saline-alkaline soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 212, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Xu, Y.; He, G.; Zhao, X.H.; Wang, C.P.; Li, S.J.; Zhou, G.K.; Hu, R.B. Combined application of acidic biochar and fertilizer synergistically enhances Miscanthus productivity in coastal saline-alkaline soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 893, 164811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; He, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hu, R. Biochar amendment ameliorates soil properties and promotes Miscanthus growth in a coastal saline-alkali soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 155, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, E.; El-Beshbeshy, T.; Abd El-Kader, N.; El Shal, R.; Khalafallah, N. Impacts of biochar application on soil fertility, plant nutrients uptake and maize (Zea mays L.) yield in saline sodic soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Lu, P.; Zhu, C. Effect of straw biochar on soil properties and wheat production under saline water irrigation. Agronomy 2019, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Li, B.; Cao, E.; Jian, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, C. Optimizing maize yield and mitigating salinization in the Yellow River Delta through organic fertilizer substitution for chemical fertilizers. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 249, 106498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, S.N.; Zhou, L.L.; Sun, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, L.L. Combination of Biochar and Functional Bacteria Drives the Ecological Improvement of Saline-Alkali Soil. Plants 2023, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Tao, J. The effect of biochar on crop productivity and soil salinity and its dependence on experimental conditions in salt-affected soils: A meta-analysis. Carbon Res. 2024, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Li, P.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Meng, Q. Applying bio-organic fertilizer improved saline alkaline soil properties and cotton yield in Xinjiang. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.J.; Tang, J.W.; Zhang, X.T.; Zhang, S.D.; Zhang, Q.Z. Combined improvement of coastal saline-alkali soils by biochar and Azotobacter chroococcum: Effects and mechanisms. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 212, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.; Sanaullah, M.; Mahmood, F.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, T. Co-application of biochar and salt tolerant PGPR to improve soil quality and wheat production in a naturally saline soil. Rhizosphere 2024, 29, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.H.; Liu, Y.W.; Liu, X.C.; Guo, M.F.; Gao, J.Z.; Yang, M.; Liu, X.S.; Wang, W.; Jin, Y.; Qu, J.J. Screening of saline-alkali tolerant microorganisms and their promoting effects on rice growth under saline-alkali stress. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 481, 144176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkaew, T.; Kantachote, D.; Nitoda, T.; Kanzaki, H.; Ritchie, R.J. Characterization of exopolymeric substances from selected Rhodopseudomonas palustris strains and their ability to adsorb sodium ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, A.; Pang, Q. Enhancement of sulfur metabolism and antioxidant machinery confers Bacillus sp. Jrh14-10–induced alkaline stress tolerance in plant. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yan, L.; Riaz, M.; Zhang, Y.R.; Jiang, C.C. Role of boron and its detoxification system in trifoliate seedlings (Poncirus trifoliate (L) Raf.) response to H+ toxicity: Antioxidant responses, stress physiological indexes, and essential element contents. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Xue, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Y. Biochar-based fertilizer amendments improve the soil microbial community structure in a karst mountainous area. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Weisenhorn, P.; Gilbert, J.A.; Chu, H. Wheat rhizosphere harbors a less complex and more stable microbial co-occurrence pattern than bulk soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 125, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyksma, S.; Pester, M. Oxygen respiration and polysaccharide degradation by a sulfate-reducing acidobacterium. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolan, S.; Hou, D.; Wang, L.; Hale, L.; Egamberdieva, D.; Tammeorg, P.; Li, R.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; et al. The potential of biochar as a microbial carrier for agricultural and environmental applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 886, 163968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifullah; Dahlawi, S.; Naeem, A.; Rengel, Z.; Naidu, R. Biochar application for the remediation of salt-affected soils: Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.Q.; Wang, Y.S.; Huo, X.Y.; Chen, W.J.; Wang, D.X. Drought and vegetation restoration patterns shape soil enzyme activity and nutrient limitation dynamics in the loess plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 123846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Christie, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Maize yield and soil fertility with combined use of compost and inorganic fertilizers on a calcareous soil on the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 155, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Y.; Song, C.C.; Yang, G.S.; Miao, Y.Q.; Wang, J.Y.; Guo, Y.D. Changes in labile organic carbon fractions and soil enzyme activities after marshland reclamation and restoration in the Sanjiang plain in northeast China. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Huang, R. Adsorption of extracellular enzymes by biochar: Impacts of enzyme and biochar properties. Geoderma 2024, 451, 117082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, Y. Variations in Soil Bacterial Community Diversity and Structures Among Different Revegetation Types in the Baishilazi Nature Reserve. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, J.; Wei, G.; Lin, Y. Natural revegetation of a semiarid habitat alters taxonomic and functional diversity of soil microbial communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.Y.; Chen, R.R.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.P.; Lin, X.G.; Feng, Y.Z. Important ecophysiological roles of non-dominant Actinobacteria in plant residue decomposition, especially in less fertile soils. Microbiome 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Tian, L.; Shi, S.; Xu, S.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, C. Aggregate-related changes in soil microbial communities under different ameliorant applications in saline-sodic soils. Geoderma 2018, 329, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadekar, S.D.; Kale, S.B.; Lali, A.M.; Bhowmick, D.N.; Pratap, A.P. Utilization of sweetwater as a cost-effective carbon source for sophorolipids production by Starmerella bombicola (ATCC 22214). Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 42, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lee, J.G.; Cho, S.R.; Song, H.J.; Kim, P.J. Silicate Fertilizer Amendment Alters Fungal Communities and Accelerates Soil Organic Matter Decomposition. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Su, L.B.; Jing, M.; Wang, K.Q.; Song, C.G.; Song, Y.L. Nitrogen addition restricts key soil ecological enzymes and nutrients by reducing microbial abundance and diversity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Maurya, B.R.; Meena, V.S.; Bahadur, I.; Kumar, A. Identification and characterization of potassium solubilizing bacteria (KSB) from Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.B.; Dsouza, M.; Gilbert, J.A.; Guo, X.S.; Wang, D.Z.; Guo, Z.B.; Ni, Y.Y.; Chu, H.Y. Fungal community composition in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization is most influenced by the type of organic matter. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 5137–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Liu, J.J.; Yu, Z.H.; Li, Y.S.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.B.; Wang, G.H. Three years of biochar amendment alters soil physiochemical properties and fungal community composition in a black soil of northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.T.; Liu, D.D.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.Z.; Dou, R.Z.; Gao, X.; Wang, L. Effects of metal oxide nanoparticles on soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities in two different soil types. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xun, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R. Rhizosphere microbes enhance plant salt tolerance: Toward crop production in saline soil. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 6543–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Yasmeen, T.; Arif, M.S.; Ali, S.; Ali, B.; Hameed, S.; Zhou, W.J. Plant growth promoting bacteria confer salt tolerance in Vigna radiata by up-regulating antioxidant defense and biological soil fertility. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 80, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.Y.; Hu, H.Z.; Feng, J.C.; Xu, B.M.; Du, C.Y.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Y.X.; Wang, C.Y. Metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses revealed overexpression of TaMGD enhances wheat plant heat stress resistance through multiple responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizjak-Johansson, T.; Braunroth, A.; Gratz, R.; Nordin, A. Inoculation with in vitro promising plant growth-promoting bacteria isolated from nitrogen-limited boreal forest did not translate to in vivo growth promotion of agricultural plants. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbez, E.; Dünser, K.; Gaidora, A.; Lendl, T.; Busch, W. Auxin steers root cell expansion via apoplastic pH regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4884–E4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).