Abstract

In the cherry-growing area of Apulia (Italy), sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cultivars are commonly grafted onto Prunus mahaleb L. rootstock. This study investigated the influence of the scion on the fruit quality of the rootstock, an aspect that remains largely underexplored in studies of stionic interactions. In an old sweet cherry orchard in the Bari area, several ‘Ferrovia’ trees grafted onto P. mahaleb L. rootstock were observed, where some rootstock individuals had developed fruiting branches below the grafting point. We collected fruits from those mahaleb rootstocks and compared them with fruits produced by non-grafted P. mahaleb L. trees growing in the same orchard. Extracts of grafted and non-grafted mahaleb cherries was analyzed by HPLC-DAD and 1H-NMR. Anthocyanins, coumaric acid derivatives, organic acids, and reducing sugars were identified in both extracts. Non-grafted mahaleb fruits were characterized by a higher relative content of malic acid, fructose, dihydro-coumaric acid derivatives, and anthocyanins and lower content of α/β glucose and sorbitol, with respect to the grafted mahaleb. The metabolic differences observed between fruits from grafted and non-grafted P. mahaleb L. were further supported by our preliminary NMR-based analysis conducted on fruit juice over two consecutive years. The results suggest that grafting may induce some physiological changes not only in the scion, but also in the rootstock, even in its vegetative (above-ground) organs, if developed. This work represents a novel finding and reinforces the broader understanding that grafting impacts physiological processes in plants.

Keywords:

mahaleb rootstock; grafting; stionic influence; wild cherry fruit; anthocyanin; HPLC-DAD; 1H-NMR; metabolomics 1. Introduction

Fruit trees are typically formed by a combination of a scion and a rootstock, where the rootstock has been selected to be more adapted to the pedological conditions and the scion has been chosen for its desirable fruit quality traits [1].

The formation of a successful graft is a complex biochemical and structural process that includes an immediate wound response, followed by the development of a callus and the formation of new vascular tissues, between rootstock and scion [2]. The bionts often belong to the same species or genus to favor the interaction between scion and rootstock. However, the phenomenon of graft incompatibility is frequently reported in the literature [3,4]. In fact, grafting induces significant biochemical, physiological, and anatomical changes in the tree, which have been associated with the inhibition of cambial activity at the grafting point and the subsequent lack of vascular union. As a result, water flow and the translocation of minerals and metabolites through the graft union are greatly reduced. This occurrence affects not only the vegetative status of the tree but also negatively influences fruit quality [5].

It is well established that rootstock influences the scion’s growth, yield, and nutrient translocation, as well as its response to biotic and abiotic stresses through molecular crosstalk between the two grafted partners [6]. Fruit quality attributes, which are highly valued in modern fruit tree cultivation, are also influenced by the rootstock [7]. In rare instances, the rootstock may produce suckers that eventually flower and fruit. From an agronomic standpoint, this phenomenon is regarded as undesirable, as it leads to physiological imbalances that can compromise tree productivity and longevity.

In the Apulia Region (Italy), sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) is commonly grafted onto seedlings belonging to Prunus mahaleb L. (also known as ‘mahaleb’), which is well adapted to the drained local soils. The compatibility between the main cultivars grown in the area (i.e., ‘Ferrovia’, ‘Giorgia’, ‘Bigarreau Burlat’, ‘Lapins’) and the mahaleb rootstock is generally satisfactory [8].

P. mahaleb L. is a deciduous tree species belonging to the Rosaceae, subfamily Prunoideae. It is native to the warm and dry regions of Western Asia, although it also occurs in Central and Southern Europe and North Africa, with its distribution extending as far as Central Asia.

In the Apulia Region, P. mahaleb is well adapted to the warm and dry environment and is almost exclusively employed as a rootstock for sweet cherry. For this reason, a few local nurseries cultivate it to produce seedlings to be used as rootstocks. The mahaleb fruit looks like a small cherry that turns from red to dark purple during ripening, and becomes black at full maturity. These fruits have an intense bitter taste due to coumarin content that makes them inedible, although they are used in Apulia to prepare a local alcoholic infusion (liqueur) called ‘Mirinello di Torremaggiore’ [9].

An undesirable characteristic of a rootstock is represented by its re-growth (known as a sucker), a phenomenon that happens when, in spring, buds break and grow. In addition, a rootstock can produce fruits, but with less desirable pomological traits. Such an event was observed in an old sweet cherry orchard located in Bari province (Apulia Region, Italy), in which P. mahaleb L. was used as rootstock. Exceptionally, several individuals produced fruiting branches growing below the grafting point, which bloomed and fruited in the same way as the scion, which itself was also bearing fruit at the same time. This intriguing situation inspired us to set up a comparison between the fruits produced by mahaleb rootstocks and those obtained from non-grafted mahaleb trees growing in the same orchard. Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze fruits from both grafted (rootstock) and non-grafted mahaleb, in order to assess whether the scion (the grafted cultivar) influences the traits of the fruit produced by the rootstock (mahaleb). This approach is the opposite of what has traditionally been applied in agronomic studies on grafted plants. It is well known that rootstock impacts the scion’s growth, yield and quality attributes, by modulating the plant physiology in different ways [6,7]. This study, instead, originated from a curiosity-driven investigation into the metabolic events induced by grafting, affecting not the scion but rather the rootstock, at the fruit metabolomic level. In this study, we report the HPLC and 1H-NMR analysis of metabolites found in mahaleb fruits, both from grafted and non-grafted trees. NMR spectral data were then submitted to chemometric analysis to investigate potential differences in the metabolic profiles of fruits originating from grafted and non-grafted trees.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

This research was established in the summer season of 2021, following preliminary NMR-based analysis performed in 2019 and 2020 in the countryside of Conversano (Bari, Apulia Region, Italy, lat.: 40° 58′ 1.92″, long.: 17° 6′ 56.16″). The sweet cherry orchard under study consisted of the main Apulian cultivar ‘Ferrovia’ (P. avium L.), grafted onto P. mahaleb L. (aged over 10 years). In that orchard, several individuals (n = 3) exhibited fruiting branches growing below the grafting point, which fruited during the same period as the scion. Some adult trees of P. mahaleb L. (non-grafted mahaleb, aged over 10 years) were also growing in the same orchard. Trees, trained to vase, at 5 × 5 m distance, were managed according to standard agronomic practices of the area. In the second fortnight of June, mahaleb fruits were collected, at the same stage of ripening (full ripening) and on the same date, from both the re-growth part of mahaleb (grafted to ‘Ferrovia’) and the non-grafted mahaleb trees. Sample fruits (10 fruits/tree) were maintained in cold conditions up to the laboratory and then stored at −20 °C until HPLC analysis. Plant material collection (2019–2020 harvest year) related to the preliminary NMR-based analysis consisted of a total of eighteen fruit juice samples (six from non-grafted and six from grafted trees, for the 2019 harvest year; three from non-grafted and three from grafted trees, for the 2020 harvest year), as described in Supplementary Material S1.

2.2. Chemicals

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), except authentic standards of kuromanin chloride (cyanidin 3-O-glucoside chloride) (Extrasynthèse, Genay, France). Deuterium oxide (99.9 atom %D) containing 0.05 wt% 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionic-2,2,3,3 d4 acid sodium salt (TSP) was purchased from Armar Chemicals (Döttingen, Switzerland).

2.3. Extraction and Analysis for Identification and Quantification of Anthocyanins by HPLC

Extraction was performed in triplicate from 500 mg ground (depitted) mahaleb fruits macerated in 10 mL solvent (ethanol/methanol + 2% formic acid) overnight at 4 °C. After centrifugation at 3500× g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was recovered and the extraction was repeated on a rotary shaker at room temperature for one hour. After centrifugation (as above), both supernatants were combined and the organic solvent evaporated in vacuo at 32 °C, using an R-205 Büchi rotavapor (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland), then brought to a known volume with acidified water (0.1% formic acid). Extracts were filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane (PTFE) (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), stored at −20 °C and analyzed by HPLC within one week. Aliquots of extracts were lyophilized (Freezone®, Labconco Corp., Saint Louis, MO, USA) for NMR analysis.

The identification and quantification of anthocyanins in mahaleb extracts were performed using an Agilent 1100 Liquid Chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA); the chromatographic conditions and column were the same as reported in Gerardi et al. [10]. Individual anthocyanins were identified by comparing their peak retention times and UV–Vis spectra with those of a commercial standard (for cyanidin 3-O-glucoside) and anthocyanin profiles previously reported for mahaleb fruits [9]. The identified compounds were quantified by the external standard method using a six-point calibration curve of kuromanin chloride (cyanidin 3-O-glucoside chloride). The results were expressed as mg Kuromanin Equivalent (KEq)/g fresh weight (fw).

2.4. Sample Preparation for NMR Analysis

A total of six lyophilized extracts from grafted and non-grafted mahaleb samples were analyzed. Each sample was obtained by dissolving the extract in 600 μL of deuterated water (D2O) containing the internal standard TSP 0.05 wt%. The resulting solution was then placed in an NMR tube (0.5 mm diameter). P. mahaleb L. fruit juice sample preparation related to preliminary NMR-based studies performed in 2019 and 2020 is described in Supplementary Material S2.

2.5. 1H-NMR Spectra Acquisition and Processing

The acquisition of the spectra was conducted at a constant temperature (300 K) on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz Ascend NMR Spectrometer (Bruker Italia, Milan, Italy), operating at 600.13 MHz, equipped with a z-axis gradient coil and automatic tuning matching (ATM). The acquisition of the experiments was performed in automation mode, with IconNMR software version 5 (Bruker), after loading of the samples with a Bruker Automatic Sample Changer, and a 1H NMR spectrum with water signal suppression (zgcppr Bruker pulseprogram was acquired for each sample, with a spectral window of 20.0276 ppm (12,019.230 Hz), 128 scans (NS), 16 dummy scans (DS) and a 90° pulse (p1) of 12.90 msec. The standard processing procedures (Fourier transform, phase and baseline correction, 0.3 Hz line broadening (LB)) were applied on the Free Induction Decay (FID) by the software TopSpin 3.6.1 (Bruker, Biospin, Italy). After acquisition and processing, the NMR spectra were calibrated to the internal standard TSP (chemical shift set at 0.00 ppm). The assignment of metabolite signals was ascertained by the analysis of two-dimensional homo- and heteronuclear NMR spectra (2D 1H J-resolved, 1H COSY, 1H-13C HSQC, and HMBC) and by comparison with the literature data [11,12]. The NMR spectra were further segmented into a fixed base width (0.04 ppm, “normal rectangular bucketing) histograms, by Amix 3.9.15 (Analysis of Mixture, Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) software. The resulting bucket table was subjected to a standardization procedure. Specifically, centering, total sum normalization and Pareto scaling operations [13] were applied to the data matrices (“buckets”). The resulting data table, after alignment of buckets of row-reduced spectra, was used for further multivariate data analysis. The quantitative variation in discriminating metabolite content among grafted and non-grafted mahaleb extract samples was then assessed by analyzing the integrals of selected distinctive unbiased NMR signals using TSP for chemical shift calibration and quantification [14].

2.6. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

The multivariate statistical analysis was performed with the help of Simca-P version 14 (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Umeå, Sweden) software. In particular, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS–DA) were used. Unsupervised methods, such as PCA, represent the first step in data analysis and are often used at first glance to obtain a general description of the sample distribution [15]. The assessment of the correlation between the clusters of the analyzed samples (observed by PCA) and the considered classes is then carried out by using supervised multivariate statistical analysis such as OPLS–DA [16]. The DModX and Hotelling’s T-squared tests were performed to identify moderate and strong outliers, respectively. Hotelling’s T-squared test is a generalization of Student’s t-test and, in conjunction with a score plot, defines the confidence area (i.e., at 95 or 99%) [17]. The distance to the model in the X space (DModX) is calculated for each observation and defines the maximum tolerable distance (Dcrit, set at a 0.05 significance level) from the model [17]. Validation of the statistical models was performed and further evaluated by using the internal cross-validation default method (seven-fold) and with a permutation test (20 permutations) available in SIMCA-P version 14 software [17]. The parameters R2 and Q2 were used to describe the quality of the model [18]. The first (R2) is a cross-validation parameter that describes the goodness of fit. The second (Q2) described the predictive ability of the model. The level of significance (p value < 0.05) of group separation in OPLS-DA was estimated by the cross-validated analysis of variance (p[CV − ANOVA]). The tool S-line plot for the pairwise OPLS-DA model was used to visualize the centered loading vector p(ctr) colored according to the absolute value of the correlation loading, p(corr) and was used to identify discriminant metabolites. The VIP (Variable Importance in Projection) and correlation coefficient p(corr) absolute values were then considered to select the significant discriminant metabolites [17]. Values larger than 1.0 and 0.5 for VIP and absolute p(corr), respectively, were considered to select metabolites for further relative quantification. The differences in selected discriminating metabolites were then quantified by calculating the ratios, expressed as fold change (FC), of the mean intensities and standard deviation of the selected integrated NMR signals [19]. The statistical significance of the differences between the means of each variable for the two groups was assessed by the student’s t-test, with a p value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Quantification of Anthocyanins by HPLC-DAD

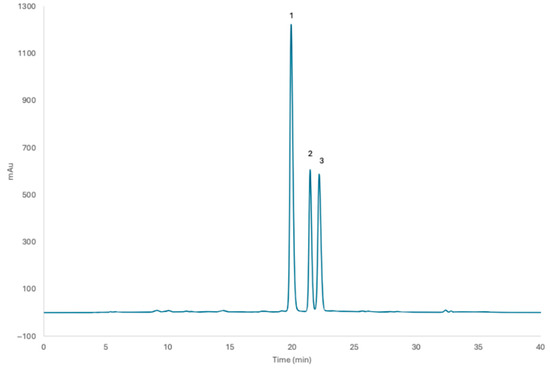

The chromatographic profile of P. mahaleb L. fruit extract (from non-grafted tree) showed three anthocyanins, all cyanidin-based, with cyanidin 3-O-glucoside as the predominant one, confirmed by matching with the external standard kuromanin chloride and spectra analysis with our previous studies on mahaleb [9,10] (Figure 1). Extracts from grafted mahaleb fruits showed similar profiles when analyzed by HPLC-DAD. The total anthocyanin quantification did not show statistical differences between non-grafted (5.58 mg KEq/g fw) and grafted mahaleb (4.84 KEq/g fw)

Figure 1.

Chromatographic profile of non-grafted P. mahaleb L. fruit extract. Peak 1: cyanidin 3-O-glucoside; peak 2: cyanidin 3-O-sambubioside; peak 3: cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside.

3.2. Metabolite Assignment in the NMR Spectrum

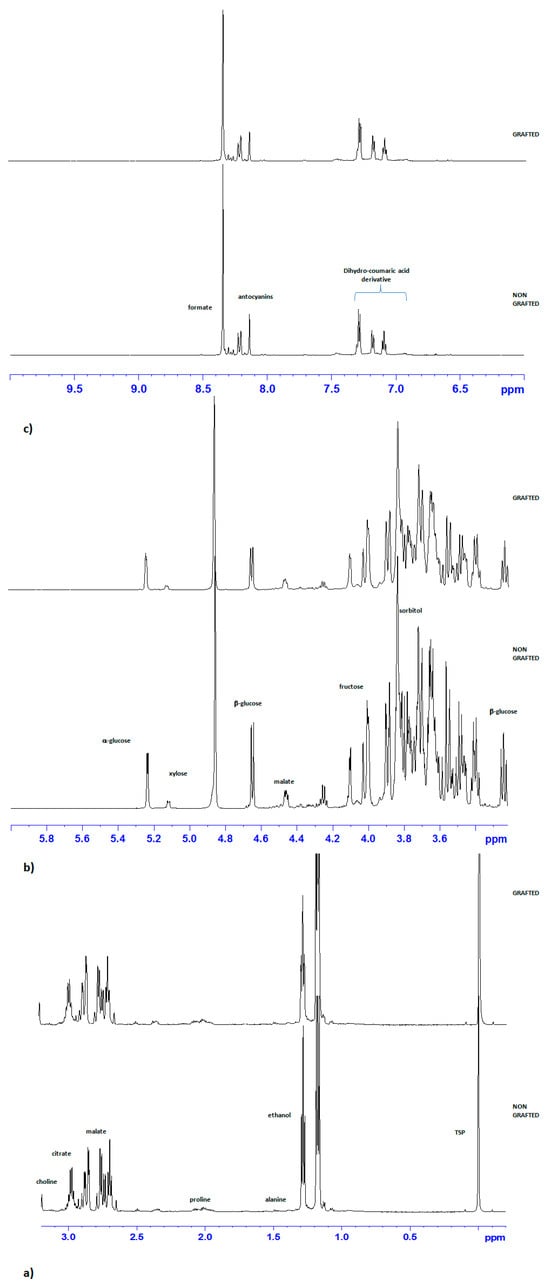

Visual inspection of the stacked plot of grafted and non-grafted mahaleb fruit extract 1H NMR spectra revealed the presence of different classes of metabolites (Figure 2). In the up-field region of the spectra (0.5–5 ppm), signals assigned to amino and organic acids and reducing sugars were observed (Figure 2a,b). As already described [10], alanine and proline, sorbitol, fructose, together with the anomeric protons of α/β glucose and citrate and malate were identified for the amino acids, organic acids and sugar classes, respectively. Moreover, signals of choline and ethanol were also observed. In the high-frequency region of the spectrum (6.0–9.5 ppm), intense signals ascribable to dihydro-coumaric acid derivatives and anthocyanin diagnostic peaks were observed (Figure 2c). These findings are consistent with our previous studies [9,10,20].

Figure 2.

Expanded areas (a) (−0.5–3.5 ppm), (b) (3–6 ppm) and (c) (6–10 ppm) of the stacked plot of 1H NMR representative spectra of grafted and non-grafted P. mahaleb L. fruit extract. The main metabolites’ resonances are indicated. TSP = trimethylsilyl propionic-2,2,3,3-d 4 acid sodium salt (internal standard).

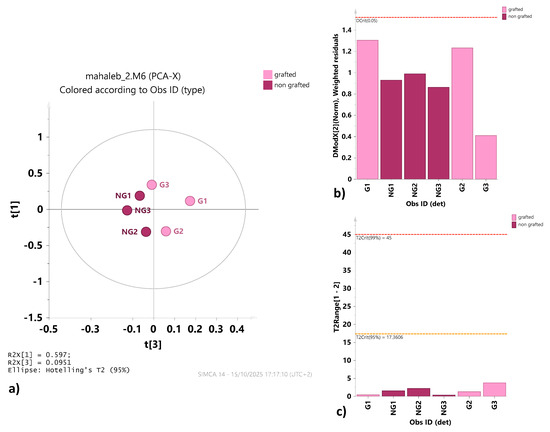

Despite the restricted database, multivariate analysis was performed to identify any possible relative difference in assigned metabolite content between the extracts of grafted and non-grafted mahaleb cherries. The preliminary unsupervised PCA, performed to obtain an overview of the sample distribution, provided a model described by t1, t2 and t3 components, explaining 59.7, 22.1 and 9.5% of the total variance, respectively. Visual inspection of the t1/t3 score plot of the model revealed a good partition between the two sample groups (Figure 3a). The goodness (R2) and predictive ability (Q2) of the model were found to be sound, with R2 cum = 0.913 and Q2 cum = 0.562. With the aim of identifying strong and moderate outliers, Hotelling’s T-squared test (Figure 3c) and DModX test (Figure 3b) were performed, respectively. No strong or moderate outliers in the samples were identified, without any evident deviation from critical limits (0.05).

Figure 3.

(a) PCA t1/t3 score plot for grafted and non-grafted mahaleb fruit extracts. Each point in the plot corresponds to an observation. These scores are weighted averages of the original ones, hence providing a good summary. Observations are colored and labeled according to the grafted (G) and non-grafted (NG) type. The confidence ellipse is based on Hotelling’s T2, with a significance level set at 0.05. (b) DMODX control chart for the whole NMR dataset. No observations exceed the critical distance (Dcrit). Observations well above the red line are significantly dissimilar from the others. (c) Hotelling’s T2 range plot displaying the distance from the origin in the model plane (score space) for each observation. Values larger than the yellow limit are suspect (0.05 level), and values larger than the red limit (0.01 level) can be considered serious outliers.

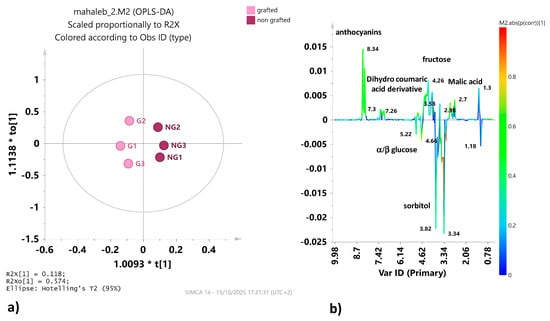

The PCA was then refined by performing an OPLS-DA pairwise analysis with the aim of identifying the discriminant metabolites between the two considered classes. Also in this case, although the ANOVA assessment of the cross-validatory (CV) predictive residuals of the model returned a p value > 0.05, a rather good model was obtained, described by 1 + 2 + 0 components that gave satisfactory descriptive (R2X = 0.89; R2Y = 0.96) and predictive parameters (Q2 = 0.51). With both values exceeding 0.5, it could be considered that the model fits the data well and has good predictive ability. The relative score plot of P. mahaleb L. fruit extracts from grafted and non-grafted trees showed a clear separation, with the non-grafted samples forming a distinct cluster (Figure 4a). Differences in the metabolic profiles of the two classes were observed by examining the S line plot for the model (Figure 4b). The extracts from non-grafted mahaleb fruits were characterized by higher relative content of malic acid (bins at 2.98 and 2.7), fructose (bin at 4.02), dihydro-coumaric acid derivatives (bins at 7.30, 7.18 and 7.1) and anthocyanins (bins at 8.22) and lower content of α/β glucose (bins at 5.22 and 4.66, respectively) and sorbitol (bin at 3.82), with respect to the grafted mahaleb.

Figure 4.

(a) OPLS DA t1/to1 score plot for the grafted (G) and non-grafted (NG) mahaleb fruit extract. (b) S line plot for the model colored according to the correlation scaled coefficient (p(corr) ≥ |0.5|). The color bar associated with the plot indicates the correlation of the metabolites that discriminate the classes.

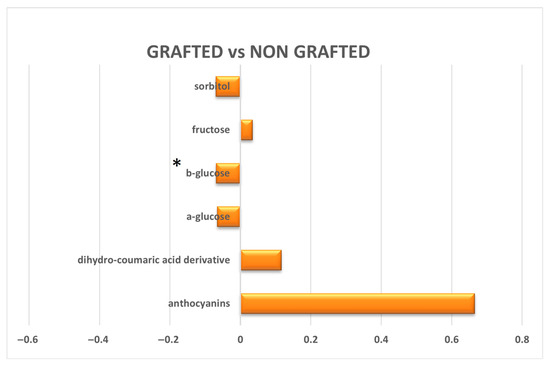

The relative quantification of the differences in the discriminating metabolites was further assessed by analyzing the integrals of selected, distinctive, unbiased NMR signals, following spectra normalization (excluding the residual water region) [21]. Specifically, only potential significant discriminant metabolites, exhibiting strong statistical reliability (|p(corr)| ≥ 0.5) and discrimination power (VIP ≥ 1), were selected for further quantification. Then, the relative variations in the discriminating metabolite content between grafted and non-grafted samples were quantified as the ratio of the normalized integrated signal areas of the corresponding NMR undistorted signals in the comparisons and graphically represented as log2 of the fold change ratios (Figure 5). A significant (p value < 0.05) log2(FC) was obtained for β-glucose content, which showed statistically significantly higher content in grafted samples.

Figure 5.

Graphic representation of the quantitative differences in the discriminating metabolites between grafted and non-grafted samples. The x-axis reports the log2 (fold change) values. Metabolites with significant log2(FC) values are indicated with * (p value < 0.05).

Interestingly, these results corroborate our preliminary NMR-based analysis performed on the whole fruit juice samples collected during 2019 and 2020 harvest seasons. Supervised OPLS-DA analysis provided good models with high predictive and descriptive ability, bringing out a clear separation between grafted and non-grafted samples (Figure S1a,b). Moreover, in both years, the separation between grafted and non-grafted samples was ascribed to the same metabolite variation reported in the present study. Consistently, non-grafted samples showed higher content of coumaric acid derivatives and fructose, whereas higher content of α/β glucose and sorbitol characterized grafted samples (Figure S1c,d).

4. Discussion

Historically, P. avium L. is an important fruit crop in Apulia (Italy), especially in the Bari area, where the renowned cv ‘Ferrovia’ is produced and exported. In those pedoclimatic conditions, the most commonly used rootstock in the area is P. mahaleb L., which is well adapted to shallow, skeletal-rich soils [8]. The grafting practice with mahaleb seedlings is typically performed on-site. In traditional cherry orchards, some mahaleb trees are usually left ungrafted as a source of seeds for future propagation.

In an old sweet cherry orchard, some mahaleb rootstocks grafted onto ‘Ferrovia’ trees developed fruiting branches below the grafting point. This unusual circumstance encouraged the present research which focused on the comparison between fruits obtained from mahaleb (grafted) rootstocks and those produced by mahaleb (non-grafted) trees. In particular, we aimed to evaluate the potential differences in the metabolic profile between fruits obtained from P. mahaleb L. trees and fruits produced from the re-growth of mahaleb as rootstocks of ‘Ferrovia’. We hypothesized that grafting affects not only the fruits produced by the scion, but also those that exceptionally develop from the rootstock, suggesting a possible influence of the scion on the rootstock.

P. mahaleb L. fruit anthocyanins have been identified and quantified in previous studies showing from three to five different anthocyanin species, all cyanidin-based: cyanidin 3,5-diglucoside; cyanidin 3-O-sambubioside; cyanidin 3-O-glucoside; cyanidin 3-O-xylosyl rutinoside; cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside [9,10,22]. Here we were able to separate and identify the three predominant anthocyanins (cyanidin 3-O-glucoside; cyanidin 3-O-sambubioside; cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside), on the basis of the retention time and spectra of the previously identified mahaleb anthocyanins [9]. The other two anthocyanins were likely co-eluted as minor components. Apart from this, the total anthocyanin quantification did not show statistical differences between grafted and non-grafted mahaleb fruits.

The anthocyanin content of the fruits from non-grafted mahaleb (5.58 mg KEq/g fw) was a bit higher than the content already reported for the wild mahaleb fruit (3.4–4.6 mg KEq/g fw) from the same area of cultivation collected years before [9]. As reported in our previous work, this finding can be attributed to variations in growing seasons and environmental factors [9].

Chemical investigations of P. mahaleb L. fruit extracts from grafted and non-grafted trees were then performed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Coupled with metabolomics, high-resolution NMR is widely used as a proficient tool in food sciences for quality, traceability and geographical/origin assessment [14,19,23,24]. The preliminary unsupervised analysis revealed a notable separation between the metabolic profiles of non-grafted and grafted P. mahaleb samples. Analysis of the S-line plot from the OPLS-DA supervised model revealed the potential biomarkers highly correlated to the model and strongly discriminating between the classes. Interestingly, our preliminary NMR-based investigations, performed on the whole fruit juice samples collected during previous harvest seasons (2019 and 2020), also revealed a clear separation between non-grafted and grafted samples, attributed to the same discriminant metabolite variations reported in the present study (Figure S1). Thus, consistently with findings reported in the literature [20], mahaleb fruit extracts from non-grafted trees were found to be richer in malic acid and fructose and also exhibited higher levels of dihydro-coumaric acid derivatives and anthocyanins. As already reported [9,10,22], mahaleb fruits are rich in coumarin-derived compounds. Coumarin compounds are recognized for their pleasant vanilla-like odor and a wide range of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticoagulant properties. The abundance of coumarin-derived molecules in mahaleb fruits makes them of interest for applications as pharmaceuticals, fragrances, cosmetics, dyes, or agricultural pesticides. The appealing properties and healing ability of the mahaleb fruit may be a result of the presence of coumarin derivatives. Different parts of the plant, including fruits, have been used as a tonic to heal various ailments in traditional medicine in Turkey [25,26].

The comparison between the metabolic profile of grafted and non-grafted P. mahaleb L. fruit extracts also reveals that, following grafting, rootstock-derived fruits exhibited higher levels of sorbitol and β-glucose, the latter with interesting statistical significance.

Sorbitol is the primary sugar alcohol in sweet cherries, accounting for more than 90% of the total, as described [27]. Its accumulation in fruit is associated not only with sweetness but also with roles as a signaling molecule involved in environmental stress responses and the regulation of plant growth and development [28]. In addition, glucose is the most abundant sugar in sweet cherry, regardless of cultivar [27], and its increase was already correlated to the rootstock effect as a consequence of enhanced photosynthesis and sugar translocation to the fruit [29]

Despite the complexity of understanding the rootstock–scion interactions, the preliminary findings of this work could lead to the hypothesis that the scion may interact with rootstock, influencing the phytochemical profile of the fruits produced by the rootstock’s suckers. Possible metabolic and hormonal competitions in regulating growth and stress responses between the two genotypes (bionts) could occur. The maintenance of proper equilibrium between the vegetative and reproductive processes is a major challenge in tree fruit production [30]. The physical interactions of the rootstock and scion [31] and the hormonal crosstalk between the two genotypes [32] might induce the rootstock to differentiate flower buds and subsequently set fruit. The understanding of these complex interactions would need specific investigation on the control mechanisms of stock/scion communication such as protein, hormone, mRNA and small RNA transport across the junction [33]. In particular, it has been revealed that multiple types of RNA molecules are actively transported across the graft union, providing a putative mechanism for the rootstock to control scion gene expression, and vice versa [34].

5. Conclusions

This study addressed a previously unexplored aspect of the rootstock–scion relationship in Prunus mahaleb L., focusing on its ability to set fruit when used as a rootstock genotype. The potential influence of the scion on the metabolic physiology of the rootstock at the fruit level was investigated for the first time. Although the statistical significance of the results is partially affected by the small sample size used, the observed metabolic differences between fruits from grafted and non-grafted P. mahaleb L. suggest that the grafting may induce some physiological changes not only in the scion, but also in the rootstock, even in its vegetative (above-ground) organs, if developed. Therefore, as supported by the good statistical parameters of the models, it is reasonable to consider the small sample size responsible for the study’s limitations rather than the null hypothesis. On the other hand, the metabolic patterns observed by HPLC and NMR methods were also in accord with the previous preliminary NMR-based research, conducted over two consecutive harvest years (2019, 2020) on the whole fruit juice, confirming and strengthening the reliability of our results.

Future research, performed on a larger dataset, could find a trend toward significance, further validating these findings.

This work adopts a novel and previously unexplored approach, the study of the rootstock fruit instead of the scion fruit, and represents a novel finding while reinforcing the broader understanding that grafting impacts physiological processes in plants.

According to our descriptive statistical results, corroborated by the preliminary investigation on the juice, this work provides new insights into the reciprocal influence between scion and rootstock—when both possess vegetative foliage on the same tree—that could potentially be exploited to fine-tune fruit characteristics.

In this context, such an approach could enable fine-tuning of rootstock fruit characteristics, specifically targeting the selective modulation of their suitability for use in local alcoholic infusions (liqueur production) or other applications where antioxidant metabolites—anthocyanins and other polyphenols or coumarins—are valued.

Nevertheless, the potential influence of a vegetative rootstock on scion fruit metabolic profiles may also be of interest and warrants further investigation in future studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242539/s1. S1: Plant material; S2. Fruit Juice: NMR sample preparation; Figure S1: OPLS DA t1/to1 score plot for the grafted (G) and non-grafted (NG) mahaleb fruit extracts from (a) 2019 and (b) 2020. S line plots (c) and (d) for the models colored according to the correlation scaled coefficient (p(corr) ≥ |0.5|).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P.F.; methodology, C.R.G. and F.B.; validation, C.R.G. and F.B.; formal analysis, C.R.G.; investigation, C.R.G. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.G. and F.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B. and F.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical contribution of Leone D’Amico, and of Rana N. Bildirici and Merve Koc, from Van University (Turkiye). Special thanks are due to Serena Marzo for the English revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| HPLC-DAD | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection |

References

- Mudge, K.; Janick, J.; Scofield, S.; Goldschmidt, E.E. A history of grafting. Hortic. Rev. 2009, 35, 437–493. [Google Scholar]

- Pina, A.; Errea, P. A review of new advances in mechanism of graft compatibility–incompatibility. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feutch, W. Graft incompatibility of tree crops: An overview of the present scientific status. Acta Hortic. 1988, 227, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenik, V.; Štampar, F. Influence of various rootstocks for cherries on p-coumaric acid, genistein and prunin content and their involvement in the incompatibility process. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. (Gartenbauwissenschaft) 2000, 65, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, B.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, A.; Silva, A.P.; Bacelar, E.; Correia, C.; Rosa, E. Scion–rootstock interaction affects the physiology and fruit quality of sweet cherry. Tree Physiol. 2005, 26, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivran, M.; Sharma, N.; Dubey, A.K.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, R.M.; Singh, N.; Singh, R. Scion–Rootstock relationship: Molecular mechanism and quality fruit production. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazem, P.; Štampar, F.; Hudina, M. Quality analysis of ‘Redhaven’ peach fruit grafted on 11 rootstocks of different genetic origin in a replant soil. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrotkò, K. Potentials in Prunus mahaleb L. for cherry rootstock breeding. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 205, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blando, F.; Albano, C.; Liu, Y.; Nicoletti, I.; Corradini, D.; Tommasi, N.; Gerardi, C.; Mita, G.; Kitts, D.D. Polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of the underutilized Prunus mahaleb L. fruit. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2641–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardi, C.; Tommasi, N.; Albano, C.; Pinthus, E.; Rescio, L.; Blando, F.; Mita, G. Prunus mahaleb L. fruit extracts: A novel source for natural pigments. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, M.R.; Pedersen, B.H.; Bertram, H.C.; Kidmose, U. Quality of sour cherry juice of different clones and cultivars (Prunus cerasus L.) determined by a combined sensory and NMR spectroscopic approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12124–12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulas, V.; Minas, I.S.; Kourdoulas, P.M.; Lazaridou, A.; Molassiotis, A.N.; Gerothanassis, I.P.; Manganaris, G.A. 1H NMR metabolic fingerprinting to probe temporal postharvest changes on qualitative attributes and phytochemical profile of sweet cherry Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, R.A.; Hoefsloot, H.C.; Westerhuis, J.A.; Smilde, A.K.; van der Werf, M.J. Centering, scaling, and transformations: Improving the biological information content of metabolomics data. BMC Genom. 2006, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girelli, C.R.; De Pascali, S.A.; Del Coco, L.; Fanizzi, F.P. Metabolic profile comparison of fruit juice from certified sweet cherry trees (Prunus avium L.) of Ferrovia and Giorgia cultivars: A preliminary study. Food Res. Int. 2016, 90, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettaneh, N.; Berglund, A.; Wold, S. PCA and PLS with very large data sets. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trygg, J.; Wold, S. Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J. Chemom. 2002, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Byrne, T.; Johansson, E.; Trygg, J.; Vikström, C. Multi- and Megavariate Data Analysis Basic Principles and Applications, 3rd ed.; Umetrics Academy: Malmö, Sweden, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock, Å.M.; Wheelock, C.E. Trials and tribulations of ‘omics data analysis: Assessing quality of SIMCA-based multivariate models using examples from pulmonary medicine. Mol. BioSyst. 2013, 9, 2589–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.H.; Elhabashy, A.; Anthony, B.M.; Kim, Y.-K.; Krishnan, V.V. Postharvest NMR Metabolomic Profiling of Pomegranates Stored Under LowPressure Conditions: A Pilot Study. Metabolites 2025, 15, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardi, C.; Blando, F.; Mulé, G.; Maltese, F.; Ali, K.; Verpoorte, R. Metabolic characterization of Prunus cerasus L. and Prunus mahaleb L. fruits. Acta Hortic. 2012, 940, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghini, V.; Unger, F.T.; Tenori, L.; Turano, P.; Juhl, H.; David, K.A. Metabolomics profiling of pre- and post-anesthesia plasma samples of colorectal patients obtained via Ficoll separation. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieri, F.; Pinelli, P.; Romani, A. Simultaneous determination of anthocyanins, coumarins and phenolic acids in fruits, kernels and liqueur of Prunus mahaleb L. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 2157–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, A.P.; Ingallina, C.; Spano, M.; Di Matteo, G.; Mannina, L. NMR-Based Approaches in the Study of Foods. Molecules 2022, 27, 7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girelli, C.R.; Papadia, P.; Pagano, F.; Miglietta, P.P.; Fanizzi, F.P.; Cardinale, M.; Rustioni, L. Metabolomic NMR analysis and organoleptic perceptions of pomegranate wines: Influence of cultivar and yeast on the product characteristics. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baytop, T. Curing with Plants in Turkey (In the Past and Today); Istanbul University Press, Nr. 3255–Faculty of Pharmacy Nr. 40; Sanal Publishing: Istanbul, Turkey, 1984; pp. 271–272. [Google Scholar]

- Özçelİk, B.; Koca, U.; Kaya, D.A.; Șekeroğlu, N. Evaluation of the in vitro bioactivities of mahaleb cherry (Prunus mahaleb L.). Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 17, 7863–7872. [Google Scholar]

- Hayaloglu, A.A.; Demir, N. Physicochemical characteristics, antioxidant activity, organic acid and sugar contents of 12 sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cultivars grown in Turkey. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Q.; Ogutu, C.O.; Liao, L.; Han, Y. Analysis of sorbitol content variation in wild and cultivated apples. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Ying, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, Y. Grafting onto pumpkin alters the evolution of fruit sugar profile and increases fruit weight through invertase and sugar transporters in watermelon. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 314, 111936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rehalia, A.S.; Sharma, S.D. Vegetative growth restriction in pome and stone fruits—A review. Agric. Rev. 2009, 30, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ballesta, M.C.; Alcaraz-Lopez, C.; Muries, B.; Mota-Cadenas, C.; Carvajal, M. Physiological aspects of rootstock–scion interactions. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloni, B.; Cohen, R.; Karni, L.; Aktas, H.; Edelstein, M. Hormonal signaling in rootstock–scion interactions. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.; Mansoor, S.; Bhat, K.M.; Hassan, G.I.; Baba, T.R.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Alsahli, A.A.; El-Serehy, H.A.; Paray, B.A.; Ahmad, P. Mechanisms Underlying Graft Union Formation and Rootstock Scion Interaction in Horticultural Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 590847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepke, T.; Dhingra, A. Rootstock scion somatogenetic interactions in perennial composite plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 1321–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).