Abstract

Recycled bio-wastes such as compost and vermicompost, and bioenergy byproducts such as digestate and biochar are widely acknowledged for their role as soil conditioners capable of preserving soil fertility, maintaining soil health, and acting as a bio-adsorbent of organic soil pollutants (BIOSORs). Moreover, they are attracting increasing attention for use as effective carriers of microbial consortia into arable soils. This study aims to combine selection of bacteria tolerating contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) and their use to fortify BIOSORs. Seventeen bacterial strains isolated from commercial bio-stimulant formulations were studied together with three strains previously isolated and identified as Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, and Serratia plymuthica. All the strains were tested in vitro for their ability to grow under increasing concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.5 and 1 mg L−1) of CECs: bisphenol A, 4-nonylphenol, penconazole, and S-metolachlor. Results highlighted a variability in the tolerance of the bacteria to the tested CECs. The B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and S. plymuthica were the most promising strains, individually or as consortium, to tolerate individual CECs and their mix. Moreover, they exhibited metabolic activity when inoculated in the BIOSORs. Nevertheless, additional investigations such as quantitative assessment of CECs are needed to validate the methodology. This work contributes to investigate the feasibility of stable and functionally active microbially enriched bio-sorbents (Me-BIOSORs) and provides preliminary evidence supporting the potential to be used in soil–plant systems at the field scale.

1. Introduction

Soil organic matter (SOM) promotes soil health and functioning by supporting biological diversity and life processes, contributing to ecosystem resilience, stimulating/inhibiting plant and microbial growth, and improving physical and chemical properties of the soil [1,2,3]. A widely accepted, effective, and economically feasible practice for maintaining functional soil health and fertility [4,5,6,7,8,9,10] is the application of organic amendments such as digestate (DG), compost (CP), vermicompost (VP), and biochar (BC), obtained from various technologies of biomass treatments [11,12,13].

DG is obtained from the anaerobic digestion of plant and animal waste [14]. CP derives from the biological decomposition of organic materials under aerobic conditions, similarly to VP, in which the stability of the process is aided by earthworms [15]. BC is the porous carbonaceous byproduct of the thermochemical conversion of biomass through pyrolysis or gasification processes [16].

These amendments can act effectively as bio-adsorbents (BIOSORs) of organic and inorganic soil contaminants. This is ascribable to their physical properties, particularly their micromorphology (large specific surface area, high porosity, and so on) and the abundance and type of reactive surface functional groups. Due to their chemical structure, BIOSORs form weak and strong bonds with hydrophilic and hydrophobic organic compounds present in the soil [17]. Conventional agriculture, among other causes, is a source of releasing potentially contaminating chemicals defined as contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) due to the use of synthetic industrial products and the addition of unstabilized and unsanitized agro-industrial biomass to the soil [18]. Due to accidental accumulation or transfer, agricultural soils can become receptors of CECs, from which they can then migrate into water or be absorbed by plants, accumulating in edible plant organs and thus entering the animal and human food chain [19].

The practice of bio-fortifying soil amendments is attracting increasing attention for their use as effective carriers of useful microbial consortia into soils [20,21,22]. Indeed, the application of microorganisms possessing plant-beneficial properties for healthier soils and food is widely recognized [23,24,25]. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, and Azotobacter play roles in soil organic matter turnover, insoluble nutrient solubilization (phosphate), the release of plant metabolites such as phytohormones, and the control of plant pathogens [26,27,28,29]. Other than enhancing soil fertility, they are involved in the restoration of contaminated agricultural areas, supporting plant recovery from xenobiotic pollutants [30]. Nevertheless, different contaminants could exert toxicity on microorganisms, leading to effects such as changes in cell metabolism, genetic variation, modification in the production of extracellular polymeric substances and enzymatic activity, and death [31,32,33,34]. In order to achieve effective biofortification of amendments against toxic compounds, it is essential to select microbial strains that tolerate these contaminants. However, little is known about the tolerance and metabolic activity of PGPB in the presence of CECs within soil amendments.

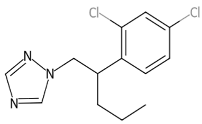

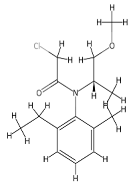

Among CECs, plant protection products (PPP) are widely employed to control crop diseases and weeds. These compounds can reach the soil following their direct application, as in the case of herbicides, after leaching from treated plants, during plant irrigation, and as components of soil amendments. Repeated treatments, excessive dosage, or incorrect use cause soil contamination and compromise the safety of agricultural products. Most of the PPP are recalcitrant to biodegradation and therefore persist in the soil for a long time, thus representing a potential toxicity for soil microbial communities. In this study, two model pesticides were considered, namely penconazole (PEN) and S-metolachlor (MET). PEN, 1-(2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl) pentyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole, is a systemic fungicide belonging to the triazole family routinely used to treat diseases caused by phytopathogenic fungi in wheat, banana, citrus, apples, and grapes [35,36]. PEN concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 0.1 mg kg−1 have been measured in a large number of sludge samples collected from municipal treatment plants in northwest Spain, with a detection rate of approximately 20% [37]. PEN exerts endocrine-disrupting effects and is toxic for soil microorganisms and animals [38,39]. MET, 2-chloro-N-(2-ethyl-6-methylphenyl)-N-(methoxyprop-2-yl)acetamide, is a selective chloroacetamide herbicide used to control grass weeds in crops such as corn, soybean, peanut, potato, tomato, and other crops [40,41]. In a silt loam soil treated with 1.36 and 1.88 mg kg−1 MET, residues were approximately 0.43 and 0.80 mg kg−1 112 d after application [42]. MET is a suspected animal carcinogen and a proven endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) [43]. Ecotoxicological effects induced by MET have been studied using the soil amoeba Euglypha rotunda [44].

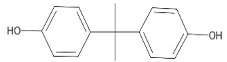

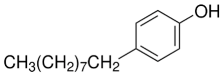

Besides pesticides, another source of organic soil contamination comes from solid and liquid matrices frequently added to cultivated fields intentionally or through mismanagement, as in the case of landfill leachate. Insufficiently decontaminated industrial and municipal wastewater and sewage sludge are increasingly spread directly on the soil for disposal by fertilizing the soil. In other cases, these wastes are added to agrozootechnical biomass entering composting plants or anaerobic digesters, whose products (compost and solid digestate) are used as soil amendments. These practices have contributed to the covert introduction of plastic derivatives, dyes, pharmaceuticals, surfactants, and other non-agricultural compounds into the soil. The xenoestrogens bisphenol A (BPA), 4,4′-(propane-2,2-diyl)diphenol, and 4-nonylphenol (4-NP), 4-(3,6-Dimethylheptan-3-yl)phenol, are widespread industrial contaminants belonging to the class of EDCs. Both EDCs have the potential to enter the soil and cause adverse effects in humans, wildlife, and the environment [45]. BPA, used to produce different plastic products, food packaging, and dental sealants, interferes with human reproduction and development, and induces metabolic diseases and gland dysfunction [46]. An extensive nationwide investigation conducted in China in 2019 showed that up to 32 bisphenols were present in the monitored soil, with the highest detection frequency for BPA (84.5%), and at least 2 bisphenols were detected in each soil sample collected [47]. In soil, BPA concentration varies over several orders of magnitude, i.e., between <0.01 µg kg−1 and 1 mg kg−1 depending on the amount and type of effluent or waste received [48]. 4-NP, used in industrial manufacturing, disrupts hormonal homeostasis, induces genotoxic effects, and damages reproductive functions [49]. 4-NP is often present in wastewater treatment plant effluents and can be released in the environment, where it persists for a long time due to its significant recalcitrance to biodegradation [50].

In this study, the four compounds were selected as representatives of the two main classes of organic soil contaminants, namely agrochemicals and industrial pollutants, and for their contrasting physicochemical properties, such as hydrophobicity (minimum Log Kow 3.24 for MET and maximum 5.76 for 4-NP), elemental composition (N presence/absence), and water solubility.

An interesting and feasible step forward for mitigating soil CEC pollution appears to be the inoculation of soil amendments with bacteria capable of metabolizing this type of pollutant and therefore acting as bio-remediators. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies either examined CECs microorganisms’ tolerance and degradation [51,52,53] or the microbial fortification amendments [20,21,22,54,55,56], but no studies have combined the selection of bacteria able to tolerate CECs and their use to fortify BIOSORs.

Given this premise, the research (carried out from November 2024 to July 2025) was sequentially structured to (i) test the ability of 20 bacterial strains isolated from commercial formulations and three bacterial strains with PGP properties previously isolated and identified to tolerate four CECs, namely PEN, MET, BPA, and 4-NP, and (ii) select the most promising candidates for the inoculation of four BIOSORs such as a BC from virgin forest trees, a DG from mixed feedstock, and DG derivative compost CP and VC.

Therefore, the aim of this work was to fill the above-mentioned research gap by evaluating the potential development of amendments fortified with bacteria able to tolerate CECs to mitigate the anthropogenic contamination in agricultural soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

In order to isolate and select candidate bacterial strains, two commercial formulations, here referred to as A and B, available on the market, were used. These formulations combine the presence of PGPB and mycorrhizal fungi. The rationale in using commercial formulations as an isolation source lies in the fact that they contain already selected bacteria with beneficial properties for the soil; they may also possess the ability to tolerate toxic compounds. Briefly, an amount of each commercial inoculum was suspended at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl sterile solution. The suspension was homogenized at maximum speed for 2 min by using a Stomacher (Astori Tecnica, Brescia, Italy). Then, a ten-fold dilution in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl sterile solution was prepared and plated onto Petri plates containing Luria–Bertani agar (LBA: LB broth—Biomaxima, Lublin, Poland, and agar 18 g L−1—VWR International, Leuven, Belgium) to obtain isolated colonies. The plates were aerobically incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, colonies were randomly picked, considering different colony characteristics (shape, color, structure), purified on the same isolation medium, and streaked individually on LBA. The obtained biomass of each strain was stored as a glycerol stock at −80 °C until analysis.

Moreover, three bacterial strains with PGP properties previously isolated and identified as Bacillus subtilis PCM B/00105 (B. subtilis, in the following named BS), Bacillus licheniformis PCM B/00106 (B. licheniformis, in the following named BL) [57,58], and Serratia plymuthica HRO-C48 (S. plymuthica, in the following named SP) [59] were also studied. The two Bacillus strains were previously isolated from the natural environment and are deposited in the Polish Microbial Collection of the Polish Academy of Sciences (Wrocław, Poland). They are capable of producing cellulolytic enzymes that accelerate the decomposition of crop residues, and at the same time provide the soil with nutrients that are easily absorbed by plants [60]. They are a component of microbiological preparation under patent n. PL230762B1. The SP strain was previously isolated from the rhizosphere of oilseed rape and is deposited in the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany). It has been reported to exhibit antifungal effect against plant pathogenic fungi, and to show a plant growth-promoting ability; indeed, it is characterized by chitinolytic activity and production of both antifungal antibiotics and plant growth hormone indole-3-acetic acid [61,62]. It was successfully applied to protect strawberry roots and the seeds of the oilseed rape as a biocontrol agent [59]. These three strains were tested on apple, tomato, and strawberry as part of the H2020 EXCALIBUR project (grant no. 817946).

Therefore, a screening of the isolated strains for their ability to tolerate the CECs under study was carried out. Results (see Section 3) led to discarding the newly isolated strains in favor of BS, BL, and SP; hence, no further investigations were carried out to identify the newly isolated strains.

2.2. Chemicals

Chemicals tested were the EDCs BPA with purity ≥ 99.0% (CAS no: 80-05-7) and 4–NP with purity ≥ 98.0% (CAS no: 104-40-5), the fungicide PEN with purity ≥ 98.0% (CAS no: 66246-88-6), and the herbicide MET with purity ≥ 98.0% (CAS no: 87392-12-9). These compounds were purchased from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. The structural formula and some properties of these chemicals are shown in Table 1. For each chemical, a stock solution with a concentration of 1 g L−1 in 96% ethanol (HPLC grade purchased from Merck KGaA) was prepared and then properly supplemented in the LB growth medium to reach a final concentration of 1, 0.5, and 0.2 mg L−1 for the resistance assays. A control solution with no contaminant addition (0 mg L−1) was also prepared. The CECs mixture contained all four compounds, each at 1 mg L−1. The maximum percentage of ethanol present in the growth medium was 0.096%.

Table 1.

Chemical name and some properties of the four CECs tested.

2.3. Organic Amendments

Samples of DG and its aerobic derivatives, CP and VC, were provided by the C&F Energy Società Agricola s.r.l., Capaccio, Italy. DG was produced by a medium-scale biogas-producing plant operating under thermophilic conditions (55–60 °C). The biogas plant was supplied with a mixture of 80% buffalo manure, 15% olive mill wastewater, 3% agrifood industry residues, and 2% poultry manure. The rated power of the plant, constituted by two continuously stirred tank reactors (CSTR) of a total capacity of 3000 m3, was 500 kW with a hydraulic retention time of 60 days which ensured optimal conditions for the bioconversion of the feeding biomass. The resulting raw DG was mechanically separated into the liquid fraction (named liquor), which was discarded, and the solid fraction, which was collected. Before storage, the solid DG was subjected to a post-process thermal treatment (65 °C, 5 days), which is comparable to a pasteurization process.

The CP and VC were produced through aerobic bioconversion of the above-described solid DG. In short, mature CP was obtained as the final product of DG composting in an aerated pile composting system for approximately 2 months. To produce VC, solid DG was kept in the open air for 4 days, then earthworms (Eisenia fetida L.) were added, and the biomass was allowed to stabilize for 2 months. The main process parameters (moisture, temperature, pile aeration, and earthworm vitality) were strictly controlled during the vermicomposting process. Further details on DG, CP, and VC production and their multianalytical characterization are reported in Loffredo et al. [63].

The BC sample, commercially named “Natural Biochar”, was purchased from Silpa s.r.l., Crotone, Italy. It was produced through a pyro-gasification process at a temperature of 750 °C exclusively from virgin beech wood chips from authorized cuts of forests falling within the territory of controlled supply chains. After the entry of the biomass (moisture between 7 and 13%) into the reactor, preheated air was blown in to trigger the thermochemical reaction and maintain the process temperature. The process yield was approximately 5% by weight of dry biomass. Compositional and structural characterization of BC is reported by Loffredo et al. [64].

Before use, each material was carefully homogenized, air-dried, and ground with a mortar and pestle to obtain particle dimensions ≤ 0.5 mm. Major characteristics of DG, CP, VC, and BC are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Major properties (means ± standard deviation, n = 3) of the BIOSORs tested in the present study.

2.4. Assay of Bacterial Strains’ Tolerance to CECs

All the bacteria were tested in vitro on LBA to assess their ability to grow in presence of the four CECs, applied either individually at increasing concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg L−1) or as a mixture (at 1 mg L−1 each). The growth response of each strain was expressed as the percentage of microbial spot diameter variation in comparison to their growth in uncontaminated sterile LBA medium. The data were, then, statistically analyzed (see Section 2.5). The CEC concentrations used in this study fall within the range of soil applications of these compounds (pesticides) or detected (pesticides and xenoestrogens) during soil monitoring activities in various regions [48]. Numerous investigations into the environmental fate of CECs and/or their effects on plants and microorganisms have used doses ranging from hundreds of µg kg−1 to a few mg kg−1 [19,65].

Since the BS, BL, and SP strains tested singularly exhibited the best tolerance to CECs, they were also tested as a consortium for their ability to grow in the presence of individual contaminants at different dosages, and in the presence of a CECs mixture at the highest dosage (1 mg L−1).

Briefly, either individual overnight broth cultures in LB or their mix (5 μL) were spotted in triplicate on contaminated LBA and uncontaminated LBA plates, incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The diameters of microbial spots were measured using the ImageJ® 1.54k software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (https://imagej.net/ij/docs/ (accessed on 30 May 2025)) by one operator carrying out all the measurements. The mean percentage variation in spot diameter was calculated in comparison to the control (LBA), and this metric was used as an indicator of strain/consortium tolerance to the different CEC concentrations.

Before growing the strains as a consortium, bacteria were tested for their antagonistic activity using the cross-streaking method [66]. Tester strains were first streaked across one half of a Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) plate and grown at 30 °C for 48 h in order to allow the possible production of antimicrobial compounds. Target strains were then streaked perpendicularly to the tester strain, and plates were incubated at 30 °C for an additional 48 h. Additionally, target strains were grown at 30 °C for 48 h in the absence of the tester, as growth control. The antagonistic effect was evaluated for the absence or reduction in the target strains’ growth compared to their growth in the absence of the tester strain. Each strain was investigated both as a tester and a target strain.

2.5. Me-BIOSORs Community-Level Physiological Profiling

The metabolic activity of microbially enriched BIOSORs (hereafter Me-BIOSORs) with selected bacterial strains (BS, BL, and SP) and their consortium in contaminated medium was evaluated through Community-Level Physiological Profiling (CLPP) analysis, using Biolog EcoPlates (Biolog Inc., Hayward, CA, USA). Each EcoPlate contains 31 different carbon sources and the control, each replicated three times. In brief, strains were grown overnight in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 30 °C. Then, cells were counted using a Thoma chamber, and approximately 108 cells of each strain (separately or as a consortium) were added to 2 g of each BIOSOR, diluted in 4 mL of TSB.

Four mL of clean TSB were added to the control samples. Tubes were then incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The following day, 16 mL of sterile 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution and 5 g of sterile glass beads (mean diameter 0.5 mm) were added to each tube. In the experiments involving CECs, the contaminants were added to a final volume of 20 mL of each tube at a concentration of 1 mg L−1. Tubes were shaken horizontally at 200 rpm for 1 h, centrifuged at 3000× g for 1 min, and the supernatant medium was collected in Biolog reservoirs. An amount of 100 µL of suspension was dispensed into each well of the EcoPlate, which was then incubated at 30 °C in an Omnilog reader (Biolog Inc., Hayward, CA, USA) for 48 h, during which the well color development was measured every 15 min. Microbial metabolism of the carbon substrates in the plate wells produced NADH, which reduced the tetrazolium redox dye included in each well into formazan, characterized by a purple color. Data of color development were visualized using the Biolog Data Analysis software (version 1.7), and the opm package (version 1.3.77) running on R (version 4.2.1) which allowed to calculate all metabolic curve parameters (λ, duration of lag phase; µ, slope of the curve; A, maximum amplitude of the curve; AUC, area under the curve), for each carbon substrate in each EcoPlate.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were initially checked for normality and homogeneity of variance. Data on strain tolerance to each CEC at the end of the 24 h growth period were analyzed by three-way ANOVA (bacterial strain × contaminant type × contaminant dosage). Another three-way ANOVA (bacterial group × contaminant type × contaminant dosage) was performed by grouping the data obtained by strain isolation origin. Data obtained from testing strains with the CECs mixture were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (bacterial strain × treatment). Multiple pairwise comparisons of means were performed by the least significant difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the software SYSTAT 13.0 (SYSTAT Software Inc., Erkrath, D). Graphs were drawn using the SigmaPlot 10.0 software (SYSTAT Software Inc.). For Biolog analyses, the differences between the groups were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey HSD post hoc test, using stats (version 4.4.1) and multcompView (version 0.1.10) R packages. The lot was obtained using the ggplot2 (version 3.5.2) R package.

3. Results

3.1. Isolated Strains and Their Tolerance to CECs

A total of 17 bacterial strains were isolated from two commercial formulations: 14 from the bio-stimulant A (MCB 1, MCB 2, MCB 3, MCB 4, MCB 5, MCB 6, MCB 7, MCB 8, MCB 9, MCB 10, MCB 11, MCB 12, MCB 13, MCB 14) and 3 from the bio-stimulant B (PNC 1, PNC 2, PNC 3).

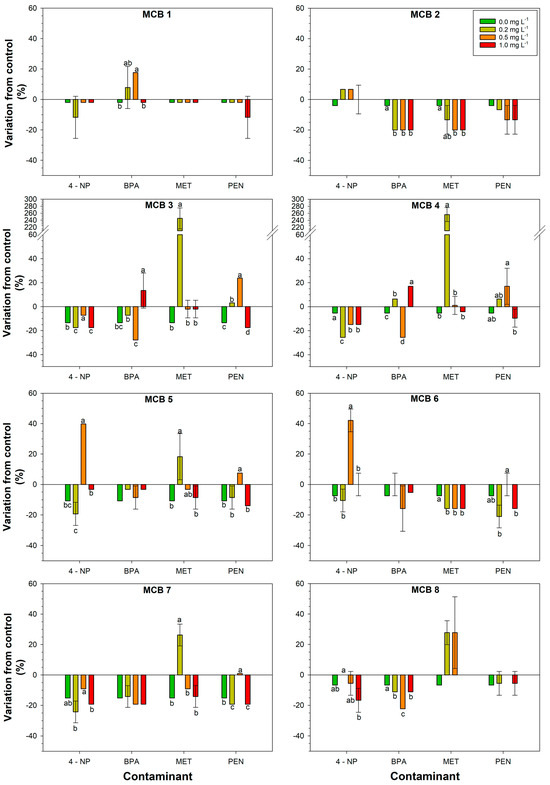

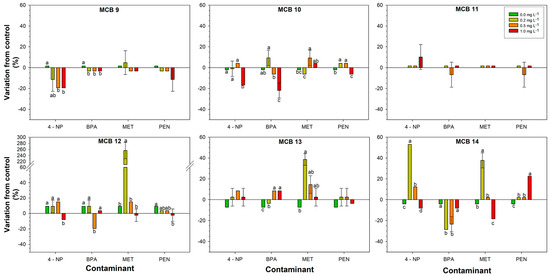

The relative growth response of each bacterial strain exposed to increasing concentrations of single contaminants is shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3. All the strains exhibited response variability both towards each CEC and their different concentrations.

Figure 1.

Response of the bacterial strains isolated from bio-stimulant A to increasing concentrations of the contaminant. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Response of the bacterial strains isolated from bio-stimulant B to increasing concentrations of the contaminant. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Response of Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus subtilis, and Serratia plymuthica strains to increasing concentrations of the contaminant. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

The strains MCB 1, MCB 9, MCB 10, and MCB 11 behaved either similarly to the control (LBA only) or were slightly inhibited (Figure 1). The strain MCB 2 did not tolerate BPA, MET, and PEN. The strains MCB 3 and MCB 4 reduced their growth in the presence of all CECs and all dosages tested, except for a slight increase when tested with BPA and PEN at the highest and medium dosages, respectively. Moreover, these strains showed a strong stimulation by MET at 0.2 mg L−1 (245% and 256% increase for MCB3 and MCB4, respectively), which suggested their ability to metabolize the compound and use it as nourishment. The strains MCB 5 and MCB 6 behaved either similarly to the control or exhibited a decrease in spot diameters. The same strains also exhibited a stimulation by 0.5 mg L−1 4-NP. The MCB 5, compared to MCB 6, showed a slight increase in spot diameter when in the presence of the lowest dosage of MET. The strains MCB 7 and MCB 8 behaved either similarly to the control or exhibited a general inhibition, although the lowest MET dosage seemed to stimulate these strains. The strain MCB 12 slightly increased its growth in the presence of all different CECs and dosages, while, compared to the control, a huge increase (256%) was observed in the presence of MET at the lowest dosage. The strain MCB 13 increased its growth when tested in the presence of MET at low and medium dosages, whereas the increase was lower in the other conditions. The strain MCB 14 was positively affected by low dosage of 4-NP and MET, and by the highest dosage of PEN (Figure 1).

Concerning the strains isolated from the bio-stimulant B, as a trend, the strains PNC 1 and PNC 2 exhibited a spot diameter increase (11.0–30.0%) with the exception of medium and high dosage of 4-NP for PNC 1, even if not always statistically supported. Towards BPA, the strain PNC 2 behaved as the control for all the dosages. On the contrary, the strain PNC 3 was inhibited by all the dosages of all the CECs (Figure 2).

Regarding the growth of the three PGPB, BL was positively affected by 4-NP and BPA at 1 mg L−1 (77.0 and 95%, respectively). The strain BS showed a variable behavior according to the CEC tested, with maximum increases for 4-NP at the highest dosage and PEN at the lowest dosage (53.0%). The strain SP increased its growth in the presence of the majority of CECs at different concentrations, with an increase ranging from 5.9 to 23.5% (Figure 3). Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 (Appendix A) show the significant impact of the CECs’ presence on the strains’ growth.

A different behavior of the strains was also observed in the presence of the CECs mix (each compound at 1 mg L−1) (Table 3). As a trend, 50% of the strains did not tolerate the CECs mix, showing a decrease in spot diameters, even if not always statistically supported. The other 50% of the strains did metabolize the mix and increased their growth (range 1.7–22% of increase).

Table 3.

Percentage variation in mean spot diameter in comparison to the control (LBA) of a single bacterial strain treated with the CECs mixture at 0 and 1 mg L−1. (mean ± SD, n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences within each bacterial strain according to the LSD post hoc test (significant at p < 0.05).

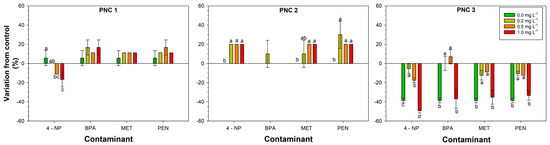

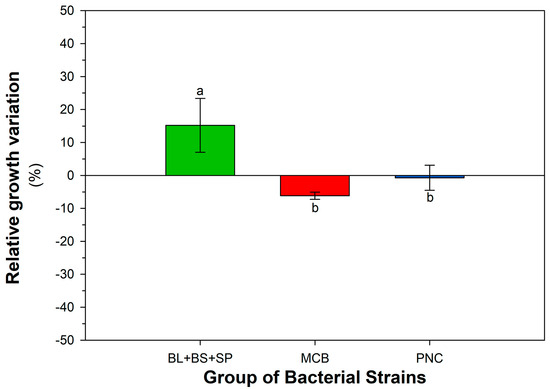

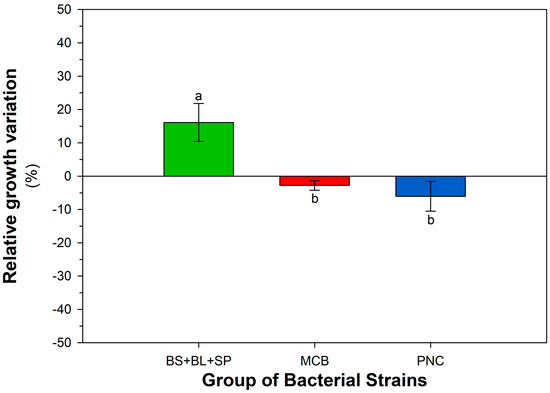

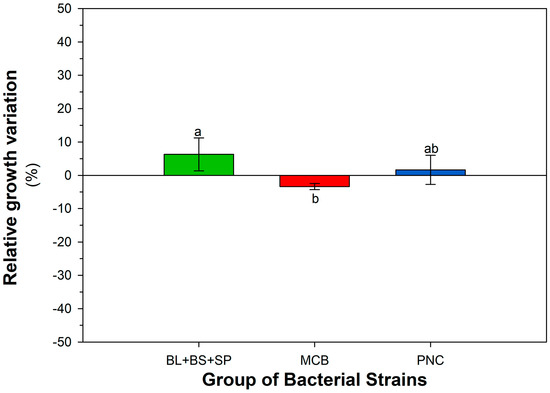

Taking into consideration the response of each strain to single contaminants at different dosages and their mix, the strains BS, BL, and SP were chosen. Furthermore, this selection was confirmed by considering the response to CECs by strains as a group: MCB, PNC, and BS + BL + SP (as cumulative growth response in each group of strains). Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4 (Appendix A) show the response of bacterial groups to each contaminant, considering all dosages. For 4-NP, BPA, the group BS + BL + SP exhibited a positive percentage variation compared to the control; the difference was statistically significant compared to the MCB and PNC group, which showed a decrease in growth. For PEN, the group BS + BL + SP showed a significant increase in diameter compared to the decrease in the MBC group. In the presence of MET, as a trend, the percentage increase in the group MCB was higher than the group BS + BL + SP, although this result was not statistically different. This was expected since, as reported above, some strains belonging to MCB significantly increased their biomass spot diameter when tested in the presence of MET. Figure A5 (Appendix A) shows, in absolute terms, the response considering all contaminants and all dosages of bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BS + BL + SP). Also in this case, the group BS + BL + SP exhibited the best performance. Statistical analysis of data is reported in Table A3. The response of bacterial groups to the CECs mix is reported in Figure 4. The groups BS + BL + SP and MCB showed positive percentage variation, while the PNC group was negatively affected. Table A4 (Appendix A) reports the two-way ANOVA performed considering the strains and CECs treatment.

Figure 4.

Growth response of different bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BL + BS + SP), expressed as percentage variation relative to the control condition (LBA), to treatment with the mix of contaminants (4-NP, BPA, MET, PEN) at individual dosage of 1 mg L−1 (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the theses (LSD test, p < 0.05).

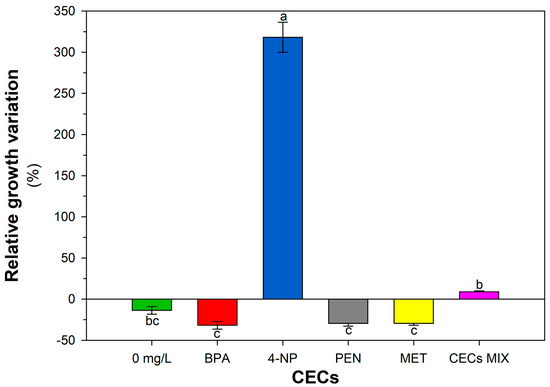

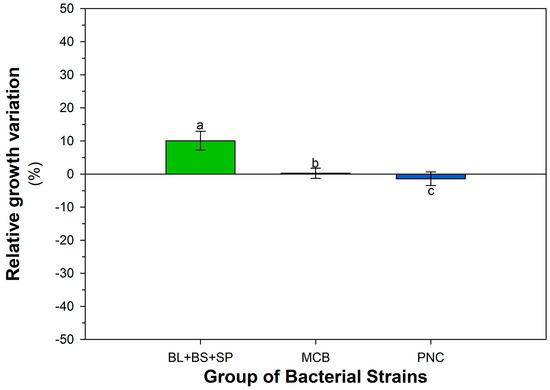

The absence of antagonistic activity among BL, BS, and SP strains was assessed using cross-streaking, and the consortium’s tolerance to each CEC and their mix is reported in Figure 5. BPA, PEN, and MET induced a reduction in spot diameter of the consortium, while a very high positive percentage variation was observed for 4-NP, compared to the control. A positive response from the consortium was also observed for the CECs mix, albeit to a lesser extent.

Figure 5.

Relative growth response of the bacterial consortium (BL + BS + SP) to single and combined CECs (CECs mix), expressed as percentage variation relative to the control (LBA) (mean ± SEM, n = 3). All contaminants were tested individually or as a mix at a concentration of 1 mg L−1. The 0 mg L−1 bar corresponds to the negative control for contaminants. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

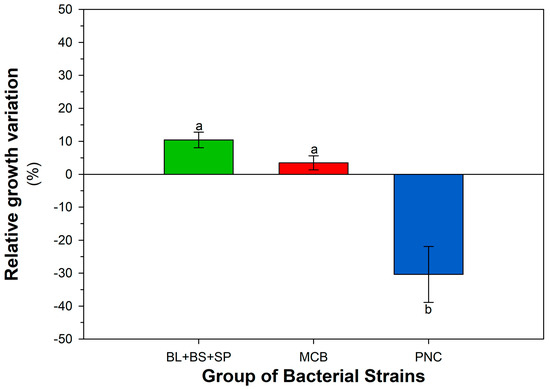

3.2. Metabolic Profile of Me-BIOSORs

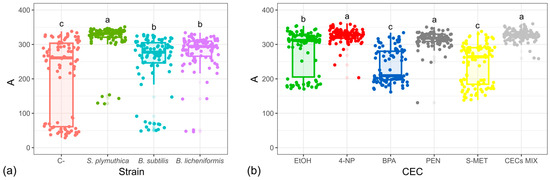

To assess whether the microbial community within the different BIOSORs was able to metabolize different carbon sources, and how this metabolic capacity changed in Me-BIOSORs, the bacterial strains BS, BL, and SP were individually added to each BIOSOR (CP, VC, DG, and BC). The investigation of their metabolic profile using Biolog technology evidenced that for CP, VC, and DG, no difference was observed between the control sample (not inoculated BIOSOR) and each Me-BIOSOR. More specifically, high metabolic activity was detected in all samples and in all EcoPlate wells, probably due to the intrinsic high microbial load and availability of nutrients in these matrices. On the other hand, concerning BC, a difference in metabolic kinetics was observed between BC and Me-BC (Figure 6). Me-BC showed a significantly higher metabolic activity (ANOVA p < 0.001) across nearly all carbon sources, compared to non-inoculated BC. Analysis of the metabolic curve amplitude (A) revealed that BC enriched with BS, BL, and SP exhibited values generally higher than 200 Biolog units (BU). In contrast, non-inoculated BC showed greater variability, with A values ranging from 50 to 300 BU (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Boxplots of the metabolic curve amplitudes (A) for each EcoPlate testing Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, and Serratia plymuthica singly taken and combined in a consortium. Each dot represents the A value corresponding to a different EcoPlate carbon source. (a) Biochar enriched with individual bacterial strains. (b) Biochar enriched with the bacterial consortium (B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and S. plymuthica) and added with CECs each at a concentration of 1 mg L−1. Significant differences between samples are evidenced with different letters.

Subsequently, the three strains were jointly added to BC to evaluate their potential to enhance its metabolic activity as a consortium, even in the presence of CECs. Despite some statistically significant differences (ANOVA p < 0.001) among the different CECs, all the samples showed a good metabolic profile, with metabolic curve amplitudes generally higher than 200 BU (Figure 6b).

4. Discussion

Microorganisms can utilize pesticides, biocides, and other organic xenobiotics through different mechanisms; by speeding up their breakdown, they contribute to decontaminating polluted environments. Indeed, bioremediation or bioaugmentation, i.e., the biodegradation process operated by microorganisms, is recognized as an effective and eco-friendly method to clean up contaminated sites [67,68]. Different bacterial species have been isolated from contaminated industrial sites, agricultural soils, and DG containing plastic debris to identify strains able to decompose plastic, bioplastic, and chemical contaminants [69,70,71,72,73]. Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, Sphingomonas, Aeromonas, Citrobacter, and Serratia, among other genera, are reported as degraders of fungicides, herbicides, and EDCs [74,75,76,77,78].

In this study, twenty bacterial strains—seventeen of new isolation and three already identified as B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and S. plymuthica—were tested for their ability to grow in the presence of CECs. Results obtained indicated that the bacterial tolerance to tested CECs was not only strain-dependent but also linked to the physicochemical properties (chemical structure, hydrophobicity, elemental composition, and so on) of the contaminant applied; for example, the N present in the molecular structure of PEN and MET could become available to microbial cells after decomposition of the contaminants. We did not perform chemical analyses to investigate the CEC degradation by the tested strains, but their variation in growth could be an indication of the breakdown of the molecules that need to be verified.

The three selected bacterial strains (BS, BL, and SP) are known for their plant-growth-promoting properties. The genus Bacillus encompasses several well-known PGPB species [58], and BS and BL can prevent the development of pathogenic factors, have a positive effect on soil properties (on its structure, availability of micro and macronutrients, water capacity), and stimulate the growth and development of agricultural and horticultural plants [57]. Moreover, S. plymutica is reported for its antifungal activity in plant protection [59,79,80].

In addition to the benefits on plants, this study highlighted a new important characteristic of these strains, employed individually and as a consortium, such as their significant tolerance to the CECs tested either singularly or in mixture.

Results obtained indicated that these bacteria could be good candidates for biofortification of organic matrices, as demonstrated by the good tolerance shown to the CECs mix at the highest dosage of 1 mg L−1 in BC.

As mentioned above (see Section 1), no research has reported the combination of CECs-tolerant bacteria selection and bacterial amendment fortification. Bioaugmentation is usually studied or carried out with microbial consortia directly added to the contaminated sites. The application of a consortia made with four Bacillus strains, one Alcaligenes strain, and one Pseudomonas strain was reported to be efficient in bioremediating soil contaminated with chlorantraniliprole [81]. Species of Aeromonas, Acinetobacter, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas exerted optimal removal of contaminants from wastewater [82]. Different authors have reported either the fortification of amendments with PGPB or the application of amendments and PGPB separately with a goal different from site detoxification by microorganisms [20,21,22,83,84]. Recent research has reported the sites’ decontamination by amendments and microorganism consortia applied separately to the sites. Indeed, Cao et al. 2022 [85] demonstrated significantly enhanced soil detoxification from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and toxic metals due to the integrative effects of amendments and microbial agents such as Bacillus subtilis, Sphingobacterium multivorum, and a commercial microbial inoculant. Instead of amendments used as immobilization supports for CEC-detoxifying bacteria, recent research has reported the usefulness of a combination of Halomonas sp. and nanoparticles in remediating metal pollution [86]. Although it is not possible to directly compare these literature results with ours (different aims, methods, and microorganisms used), they nevertheless indicate an increasing interest in exploring new strategies involving bacteria for site CEC augmentation.

Hence, the innovation of our study lies in having explored the feasibility of developing Me-BIOSORs fortified with bacteria possessing both PGP traits and tolerance to CECs that they may encounter in the soil and in contaminated organic matrices that reach the soil. Considering the need to mitigate the contamination of agricultural systems by CECs, the bacterial strains selected in this study could be useful because, in vitro, they tolerated the presence of CECs, individually or as a consortium, and exhibited metabolic activity in the enriched matrices, in particular BC.

A step forward, the results obtained here are evaluating the effectiveness of the Me-BIOSORs in reducing the entry and accumulation of organic contaminants in plants, and consequently in the human food chain, by a microcosmic-scale experiment in which the Me-BIOSORs obtained with BL, BS, and SP will be applied in a model soil–plant system with different plant species artificially contaminated with CECs.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, three of the twenty bacterial species tested, namely B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and S. plymuthica, were selected as the most suitable for tolerating and metabolizing in vitro four CECs widely present in environmental systems as a result of agricultural and industrial activities. This study demonstrates that the different soil amendments tested are suitable supports for bacteria immobilization and that the BL, BS, and SP strains immobilized in CEC-contaminated amendments can cope with the presence of CECs and exert metabolic activities. The relevance of this research lies in an integrated approach that combines the useful properties of amendments and microorganisms in the environment for CEC decontamination. Although these results require further investigation and validation for both bacterial survival and decontamination properties in an experimental soil–plant system, they appear encouraging and may pave the way for the development of new biofortified soil improvers useful in sustainable agriculture.

Indeed, the practical implication of this work is the possibility of producing biofortified soil amendments with an established consortium of PGPB characterized by decontamination properties towards one or more CEC, for direct use in contaminated agricultural soils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., R.S., M.T.R., G.S., S.M., S.D.D. and E.L.; methodology, R.S. and S.D.D.; formal analysis, M.T.R. and S.D.D.; software, G.S. and S.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and S.D.D.; writing—review and editing, R.S., M.T.R., G.S., S.M., S.D.D., E.L.; funding acquisition, A.G., S.M. and E.L.; project administration, A.G., S.M. and E.L.; supervision, A.G., R.S. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present work contributes to the project PRIN 2022 PNRR, entitled “Microbially enriched biosorbents from waste recycling and soil-resident fungi as novel and sustainable tools to mitigate soil pollution by chemicals of emerging concern and prevent their entry and accumulation in vegetables”, Call 1409, dated 14 September 2022, financially supported by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—PNRR—Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1. Prot. P20223YAYP. CUP master: H53D23010520001, CUP: C53D23009560001. This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Giancarlo Cattaneo from C&F Energy, Società Agricola s.r.l. (Altavilla Silentina, Italy) for having generously provided solid digestate and its derivatives compost and vermicompost. The authors are also grateful to Wojciech Kepka from INTERMAG Sp. Z o.o. (Olkusz, Poland) and Gabriele Berg from Graz University of Technology (Graz, Austria) for providing the strains Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis, and Serratia plymuthica, respectively, used in the activities of the H2020 EXCALIBUR project (grant no. 817946). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DG | Solid anaerobic digestate |

| CP | Digestate-derived compost |

| VC | Digestate-derived vermicompost |

| BC | Biochar |

| CECs | Contaminants of emerging concern |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| 4-NP | 4-Nonylphenol |

| PEN | Penconazole |

| MET | S-Metolachlor |

| CLPP | Community-Level Physiological Profiling |

| LBA | Luria–Bertani agar |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Effects of bacterial strains, contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter compared to the control (LBA) tested by three-way ANOVA (Bacterial strain × Contaminant × Dosage).

Table A1.

Effects of bacterial strains, contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter compared to the control (LBA) tested by three-way ANOVA (Bacterial strain × Contaminant × Dosage).

| Main Factor | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Bacterial strain (S) | <0.0001 *** |

| Contaminant (C) | <0.0001 *** |

| Dosage (D) | <0.0001 *** |

| S × C | <0.0001 *** |

| S × D | <0.0001 *** |

| C × D | <0.0001 *** |

| S × C × D | <0.0001 *** |

Bold values are statistically significant. *** p < 0.001.

Table A2.

Effect of contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter in comparison to the control (LBA). Values are p-values from two-way ANOVA (Contaminant × Dosage). Significant values are in bold.

Table A2.

Effect of contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter in comparison to the control (LBA). Values are p-values from two-way ANOVA (Contaminant × Dosage). Significant values are in bold.

| Strains | Main Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Contaminant (C) | Dosage (D) | C × D | |

| MCB 1 | 0.1390 | 0.0146 | 0.1429 |

| MCB 2 | <0.0001 | 0.0057 | 0.0230 |

| MCB 3 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 4 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 5 | 0.0180 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 6 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 7 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 8 | <0.0001 | 0.0234 | 0.0083 |

| MCB 9 | <0.0001 | 0.0057 | 0.0230 |

| MCB 10 | 0.0077 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| MCB 11 | 0.3339 | 0.1344 | 0.7563 |

| MCB 12 | 0.0235 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| MCB 13 | 0.0235 | 0.0029 | <0.0381 |

| MCB 14 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PNC1 | <0.0001 | 0.4182 | 0.0230 |

| PNC2 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 | 0.0921 |

| PNC3 | 0.0047 | <0.0001 | 0.0183 |

| BL | 0.0872 | 0.3255 | 0.4850 |

| BS | 0.6260 | 0.3247 | 0.4875 |

| SP | 0.1759 | 0.0056 | 0.0535 |

Bold values are statistically significant.

Table A3.

Effects of bacterial group (MCB, PNC, and BS + BL + SP), contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter compared to the control (LBA) tested by three-way ANOVA (Bacterial group × Contaminant × Dosage).

Table A3.

Effects of bacterial group (MCB, PNC, and BS + BL + SP), contaminant, dosage, and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter compared to the control (LBA) tested by three-way ANOVA (Bacterial group × Contaminant × Dosage).

| Main Factor | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Bacterial group (G) | 0.0032 ** |

| Contaminant (C) | 0.8152 ns |

| Dosage (D) | 0.0049 ** |

| G × C | 0.0020 ** |

| G × D | 0.0386 * |

| C × D | 0.2706 ns |

| G × C × D | 0.0005 *** |

Bold values are statistically significant. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns: not significant.

Table A4.

Effect of bacterial strain and treatment (CECs mix) and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter in comparison to the control (LBA). Values are p-values from two-way ANOVA (Bacterial strain × Treatment).

Table A4.

Effect of bacterial strain and treatment (CECs mix) and their interactions on percentage variation in mean spot diameter in comparison to the control (LBA). Values are p-values from two-way ANOVA (Bacterial strain × Treatment).

| Main Factor | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Bacterial strain (S) | 0.0001 *** |

| Treatment (Tr) | <0.0001 *** |

| S × Tr | <0.0001 *** |

Bold values are statistically significant. *** p < 0.001.

Figure A1.

Cumulative growth response of different bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BS + BL + SP) to bisphenol A (BPA), expressed as percentage variation compared to the control (LBA). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3), calculated across all tested concentrations of BPA (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg L−1). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure A2.

Cumulative growth response of different bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BS + BL + SP) to 4-nonylphenol (4-NP), expressed as percentage variation compared to the control (LBA). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3), calculated across all tested concentrations of 4-NP (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg L−1). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure A3.

Cumulative growth response of different bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BS + BL + SP) to penconazole (PEN), expressed as percentage variation relative to the control condition (LBA). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3), calculated across all tested concentrations of PEN (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg L−1). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among groups (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure A4.

Cumulative growth response of different bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BS + BL + SP) to S-Metolachlor (MET), expressed as percentage variation relative to the control condition (LBA). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3), calculated across all tested concentrations of MET (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg L−1). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among groups (LSD test, p < 0.05).

Figure A5.

Cumulative growth response of bacterial groups (MCB, PNC, BL + BS + SP) to contaminants of emerging concern (CECs), expressed as percentage variation relative to the control condition (LBA). Each bar represents the overall mean (±SEM, n = 3), calculated by averaging all growth responses across the four tested contaminants (BPA, 4-NP, PEN, MET) and their respective concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.5, 1 mg L−1). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups (LSD test, p < 0.05).

References

- Weil, R.R.; Brady, N.C. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Global Edition; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-292-16223-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baldock, J.A.; Nelson, P.N. Soil organic matter. In Handbook of Soil Science; Sumner, M.E., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. B25–B84. ISBN 0-8493-3136-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, W.A.; Gregorich, E.G. Developing and maintaining soil organic matter levels. In Managing Soil Quality: Challenges in Modern Agriculture; Schjønning, P., Elmholt, S., Christensen, B.T., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Oxon, UK, 2004; pp. 103–120. ISBN 0-85199-671-X. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Schulz, H.; Brandl, S.; Miehtke, H.; Huwe, B.; Glaser, B. Short-Term Effect of Biochar and Compost on Soil Fertility and Water Status of a Dystric Cambisol in NE Germany under Field Conditions. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, G. A Review on Impact of Compost on Soil Properties, Water Use and Crop Productivity. Acad. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2016, 4, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a Tool for the Improvement of Soil and Environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Midden, C.; Harris, J.; Shaw, L.; Sizmur, T.; Pawlett, M. The Impact of Anaerobic Digestate on Soil Life: A Review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 191, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragályi, P.; Szécsy, O.; Uzinger, N.; Magyar, M.; Szabó, A.; Rékási, M. Factors Influencing the Impact of Anaerobic Digestates on Soil Properties. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros-Lajszner, E.; Wyszkowska, J.; Kucharski, J. Biochar as a Stimulator of Zea mays Growth and Enzyme Activity in Soil Contaminated with Zinc, Copper, and Nickel. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuccio, M.R.; Romeo, F.; Mallamaci, C.; Muscolo, A. Digestate Application on Two Different Soils: Agricultural Benefit and Risk. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 4341–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Bai, X.; Huang, D.; Chen, Q.; Shao, M.; Xu, Q. Impacts of Digestate-Based Compost on Soil Property and Nutrient Availability. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Tiong, Y.W.; Yan, M.; Lam, H.T.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y.W. Plant Growth Enhancement under Combined Amendments of Food Waste Digestate and Rhizosphere Microbial Co-Occurrence. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, Y.W.; Sharma, P.; Xu, S.; Bu, J.; An, S.; Foo, J.B.L.; Wee, B.K.; Wang, Y.; Lee, J.T.E.; Zhang, J.; et al. Enhancing Sustainable Crop Cultivation: The Impact of Renewable Soil Amendments and Digestate Fertilizer on Crop Growth and Nutrient Composition. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decorte, M.; Papa, G.; Pasteris, M.; Sever, L.; Gaffuri, C.; Cancian, G.; Bremond, U.; Flamin, C. Exploring Digestate’s Contribution to Healthy Soils; European Biogas Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.L.; Wu, T.Y.; Lim, P.N.; Shak, K.P.Y. The Use of Vermicompost in Organic Farming: Overview, Effects on Soil and Economics. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Tan, X.; Huang, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, B. Biochar to Improve Soil Fertility: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, E.; Parlavecchia, M.; Perri, G.; Gattullo, R. Comparative assessment of metribuzin sorption efficiency of biochar, hydrochar and vermicompost. J. Environ. Sci. Health—Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes 2019, 54, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Mol, H.G.J.; Zomer, P.; Tienstra, M.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Pesticide Residues in European Agricultural Soils—A Hidden Reality Unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlavecchia, M.; Carnimeo, C.; Loffredo, E. Soil Amendment with Biochar, Hydrochar and Compost Mitigates the Accumulation of Emerging Pollutants in Rocket Salad Plants. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppuraj, R.; Thilagavathy, D.; Natchimuthu, K. Microbial Enrichment of Vermicompost. ISRN Soil Sci. 2012, 2012, 946079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Ó.J.; Ospina, D.A.; Montoya, S. Compost Supplementation with Nutrients and Microorganisms in Composting Process. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, K.R.; Ormåsen, I.; Duffner, C.; Hvidsten, T.R.; Bakken, L.R.; Vick, S.H.W. A Dual Enrichment Strategy Provides Soil- and Digestate-Competent Nitrous Oxide-Respiring Bacteria for Mitigating Climate Forcing in Agriculture. mBio 2022, 13, e00788-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, V.S.; Meena, S.K.; Verma, J.P.; Kumar, A.; Aeron, A.; Mishra, P.K.; Bisht, J.K.; Pattanayak, A.; Naveed, M.; Dotaniya, M.L. Plant Beneficial Rhizospheric Microorganism (PBRM) Strategies to Improve Nutrients Use Efficiency: A Review. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 107, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Prabha, R.; Gupta, V.K. Microbial Inoculants for Sustainable Crop Management. In Microbial Interventions in Agriculture and Environment. Vol. 2 Rhizosphere, Microbiome and Agro-Ecology; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, M.; Flor-Peregrin, E.; Malusá, E.; Vassilev, N. Towards Better Understanding of the Interactions and Efficient Application of Plant Beneficial Prebiotics, Probiotics, Postbiotics and Synbiotics. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pii, Y.; Mimmo, T.; Tomasi, N.; Terzano, R.; Cesco, S.; Crecchio, C. Microbial Interactions in the Rhizosphere: Beneficial Influences of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Nutrient Acquisition Process. A Review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, N.; Vassileva, M.; Nikolaeva, I. Simultaneous P-Solubilizing and Biocontrol Activity of Microorganisms: Potentials and Future Trends. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, M.; Serrano, M.; Bravo, V.; Jurado, E.; Nikolaeva, I.; Martos, V.; Vassilev, N. Multifunctional Properties of Phosphate Solubilizing Microorganisms Grown on Agro-Industrial Wastes in Fermentation and Soil Conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilev, S.; Azaizeh, H.; Vassilev, N.; Georgiev, D.; Babrikova, I. Interactions in Soil-Microbe-Plant System: Adaptation to Stressed Agriculture. In Microbial Interventions in Agriculture and Environment; Singh, D., Gupta, V., Prabha, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 131–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilev, S.; Naydenov, M.; Sancho Prieto, M.; Vassilev, N.; Sancho, D.E. PGPR as Inoculants in Management of Lands Contaminated with Trace Elements. In Bacteria in Agrobiology; Maheshwari, D.K., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.B.; Maillard, J.-Y.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Emerging Contaminants Affect the Microbiome of Water Systems—Strategies for Their Mitigation. npj Clean Water 2020, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C.E.I.; Okeke, E.S.; Umeoguaju, F.U.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Adedipe, D.T.; Ezeorba, T.P.C. Addressing Emerging Contaminants in Agriculture Affecting Plant–soil Interaction: A Review on Bio-based and nano-enhanced Strategies for Soil Health and Global Food Security (GFS). Discov. Toxicol. 2025, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Gao, P.; Zhu, L. Environmental Behaviors and Toxic Mechanisms of Engineered Nanomaterials in Soil. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premalatha, R.P.; Kumari, A. Contamination of arable soils with bisphenol A and phthalates along with their consequent impacts on the crops. In Emerging Contaminants Sustainable Agriculture and the Environment; Kumari, A., Rajput, V.D., Mandzhieva, S.S., Minkina, T., Van Hullebusch, E., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 307–334. ISBN 978-0-443-18985-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, M.; Paradelo, M.; López, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Influence of pH and Soil Copper on Adsorption of Metalaxyl and Penconazole by the Surface Layer of Vineyard Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8155–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nie, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Gao, X.; Shah, B.S.A.; Yin, N. Chiral Fungicide Penconazole: Absolute Configuration, Bioactivity, Toxicity, and Stereoselective Degradation in Apples. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Fernández, V.; Ramil, M.; Rodríguez, I. Basic Micro-pollutants in Sludge from Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Northwest Spain: Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Sludge Disposal. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdichizzi, S.; Mascolo, M.S.; Silingardi, P.; Morandi, E.; Rotondo, F.; Guerrini, A.; Prete, L.; Vaccari, M.; Colacci, A. Cancer-related Genes Transcriptionally Induced by the Fungicide Penconazole. Toxicol. Vitr. 2014, 28, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Triana, I.; Rubilar, O.; Parada, J.; Fincheira, P.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Durán, P.; Fernández-Baldon, M.; Seabra, A.B.; Tortella, G.R. Metal Nanoparticles and Pesticides under Global Climate Change: Assessing the Combined Effects of Multiple Abiotic Stressors on Soil Microbial Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 942, 173494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, P.J.; Harms, C.T.; Allen, J.R. Metolachlor, S-Metolachlor and Their Role within Sustainable Weed-Management. Crop Prot. 1998, 13, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.J.; Anderson, T.A.; Coats, J.R. Degradation and Persistence of Metolachlor in Soil: Effect of Concentration, Soil Moisture, Soil Depth and Sterilization. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 2640–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Ribeiro Maia, L.; Armstrong, S.D.; Kladivko, E.J.; Young, B.G.; Johnson, W.G. Influence of Cover Crop Termination Strategies on Weed Suppression, Concentration of Residual Herbicides in the Soil, and Soybean Yield. Weed Sci. 2025, 73, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou-Yang, K.; Feng, T.; Han, Y.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Ma, H. Bioaccumulation, Metabolism and Endocrine-reproductive Effects of Metolachlor and its S-enantiomer in Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amacker, N.; Mitchell, E.A.D.; Ferrari, B.J.D.; Chèvre, N. Development of a New Ecotoxicological Assay Using the Testate Amoeba Euglypha rotunda (Rhizaria; Euglyphida) and Assessment of the Impact of the Herbicide S-metolachlor. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Careghini, A.; Mastorgio, A.F.; Saponaro, S.; Sezenna, E. Bisphenol A, Nonylphenols, Benzophenones, and Benzotriazoles in Soils, Groundwater, Surface Water, Sediments, and Food: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5711–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, J.R. Bisphenol A and Human Health: A Review of the Literature. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhu, F.-J.; Jia, S.-M.; Ma, W.-L. National Investigation of Bisphenols in the Surface Soil in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, J.; Kristofco, L.A.; Steele, W.B.; Yates, B.S.; Breed, C.S.; Williams, E.S.; Brooks, B.W. Global Assessment of Bisphenol A in the Environment: Review and Analysis of Its Occurrence and Bioaccumulation. Dose-Response Int. J. 2015, 13, 15593258155983081559325815598308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Lin, H. Nonylphenol in Agricultural Soil System: Sources, Effects, Fate, and Bioremediation Strategies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 45, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, L.W.B.; Okoh, O.O.; Mkwetshana, N.T.; Okoh, A.I. Environmental Water Pollution, Endocrine Interference and Ecotoxicity of 4-tert-Octylphenol: A Review. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 248, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.A.; Malhotra, H.; Papade, S.E.; Dhamale, T.; Ingale, O.P.; Kasarlawar, S.T.; Phale, P.S. Microbial Degradation of Contaminants of Emerging Concern: Metabolic, Genetic and Omics Insights for Enhanced Bioremediation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 12, 1470522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, H.; Khalfaoui-Hassani, B.; Godino-Sanchez, A.; Naimah, Z.; Sebilo, M.; Guyoneaud, R.; Monperrus, M. Insights into Bacterial Resistance to Contaminants of Emerging Concerns and Their Biodegradation by Marine Bacteria. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.B. The Overlooked Interaction of Emerging Contaminants and Microbial Communities: A Threat to Ecosystems and Public Health. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.P.; Prabha, R.; Renu, S.; Sahu, P.K.; Singh, V. Agrowaste Bioconversion and Microbial Fortification Have Prospects for soil Health, Crop Productivity, and Eco-enterprising. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, L.; Gorai, P.S.; Mandal, N.C. Microbial fortification during vermicomposting: A brief review. In Recent Advancement in Microbial Biotechnology, Agricultural and Industrial Approach; Mandal, S.D., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 99–118. ISBN 978-0-12-822098-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Noman, M.; Qi, Y.; Shahid, M.; Hussain, S.; Masood, H.A.; Xu, L.; Ali, H.M.; Negm, S.; El-Kott, A.F.; et al. Fertilization of Microbial Composts: A Technology for Improving Stress Resilience in Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciecierski, W.; Kardasz, H.; Szychowska, K.; Wilk, R. Microbiological Preparation for Mineralization of Cellulose-Containing Organic Matter, Preferably the Postharvest Wastes and Application of Microbiological Preparation in Cultivation of Plants. Patent n. PL230762B1, 31 December 2018. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/PL230762B1/en (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Manfredini, A.; Malusà, E.; Canfora, L. Aptamer-based technology for detecting Bacillus subtilis in soil. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 6963–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurze, S.; Bahl, H.; Dahl, R.; Berg, G. Biological control of fungal strawberry diseases by Serratia plymuthica HRO-C48. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wita, A.; Białas, W.; Wilk, R.; Szychowska, K.; Czaczyk, K. The Influence of Temperature and Nitrogen Source on Cellulolytic Potential of Microbiota Isolated from Natural Environment. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, J.; Lorito, M.; Scala, F.; Schmid, R.; Berg, G.; Bahl, H. Purification and Properties of Two Chitinolytic Enzymes of Serratia plymuthica HRO-C48. Arch. Microbiol. 2001, 176, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.; Berg, G. Impact of Formulation Procedures on the Effect of the Biocontrol agent Serratia plymuthica HRO-C48 on Verticillium Wilt in Oilseed Rape. BioControl 2008, 53, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, E.; Vona, D.; Porfido, C.; Giangregorio, M.M.; Gelsomino, A. Compositional and Structural Characterization of Bioenergy Digestate and its Aerobic Derivatives Compost and Vermicompost. J. Sust. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, E.; Denora, N.; Vona, D.; Gelsomino, A.; Porfido, C.; Colatorti, N. Wood gasification biochar as an effective biosorbent for the remediation of organic soil pollutants. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Xu, M.; Afzal, M.; Jin, W.; Islam, F.; Zhong, W.; Yue, Q.; Ahmed, W.; Wang, W. Synergistic Impacts of Bisphenol A and Elevated Temperatures on Oryza sativa Development and Rhizosphere Microbiome in Diverse Cultivars. Ecotoxic. Environ. Safe. 2025, 302, 118648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castronovo, L.M.; Calonico, C.; Ascrizzi, R.; Del Duca, S.; Delfino, V.; Chioccioli, S.; Vassallo, A.; Strozza, I.; De Leo, M.; Biffi, S.; et al. The Cultivable Bacterial Microbiota Associated to the Medicinal Plant Origanum vulgare L.: From Antibiotic Resistance to Growth-Inhibitory Properties. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycoń, M.; Mrozik, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Bioaugmentation as a Strategy for the Remediation of Pesticide-Polluted Soil. Chemosphere 2017, 172, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Yadav, A.; Singh, M.; Joshi, D.; Singh, J.; Suyal, D.C.; Kumar, A.; Rajput, V.D.; et al. Beneficial Microbiomes for Bioremediation of Diverse Contaminated Environments for Environmental Sustainability: Present Status and Future Challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24917–24939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aislabie, J.; Lloyd-Jones, G. A Review of Bacterial Degradation of Pesticides. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1995, 33, 925–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde, J.; Láiz, L.; Lara-Moreno, A.; González-Pimentel, J.L.; Morillo, E. Bioaugmentation of PAH-Contaminated Soils with Novel Specific Degrader Strains Isolated from a Contaminated Industrial Site: Effect of Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin as PAH Bioavailability Enhancer. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Kondo, F. Bisphenol A Degradation by Bacteria Isolated from River Water. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002, 43, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Le, V.T.; Pham, T.H.T.; Ho, T.-T.; Nguyen, N.-L. Degradation of Triazole Fungicides by Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria from Contaminated Agricultural Soil. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidari, R.; Pittarello, M.; Rodinò, M.T.; Panuccio, M.R.; Lo Verde, G.; Laudicina, V.A.; Gelsomino, A. Isolation and Selection of Cellulose-Chitosan Degrading Bacteria to Speed up the Mineralization of Bio-Based Mulch Films. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1597786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Maki, J.-I.; Oshiman, K.-I.; Matsumura, Y.; Tsuchido, T. Biodegradation of Bisphenol A by Cells and Cell Lysate from Sphingomonas sp. Strain AO1. Biodegradation 2005, 16, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hou, X.; Liang, S.; Lu, Z.; Hou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H. Biodegradation of Fungicide Tebuconazole by Serratia marcescens Strain B1 and Its Application in Bioremediation of Contaminated Soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 127, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Chen, F.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S.; Cui, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W. Microbes as Carbendazim Degraders: Opportunity and Challenge. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1424825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książek-Trela, P.; Leszek, P.; Szpyrka, E. The Impact of Novel Bacterial Strains and Their Consortium on Diflufenican Degradation in the Mineral Medium and Soil. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatassi, G.; Baysal, Ö.; Silme, R.S.; Örnek, G.P.; Örnek, H.; Can, A. Pesticide Degradation Capacity of a Novel Strain Belonging to Serratia sarumanii with Its Genomic Profile. Biodegradation 2025, 36, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vleesschauwer, D.; Höfte, M. Using Serratia plymuthica to Control Fungal Pathogens of Plants. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2007, 2, 046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Z.; Tian, Y.; Su, X.; Tian, T.; Shen, T. A Biocontrol Strain of Serratia plymuthica MM Promotes Growth and Controls Fusarium Wilt in Watermelon. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.A.; Salem, S.H.; Abd El-Fattah, H.I.; Akl, B.A.; Fayez, M.; Maher, M.; Aioub, A.A.A.; Sitohy, M. Insights into the Role of Hexa-bacterial Consortium for Bioremediation of Soil Contaminated with Chlorantraniliprole. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Guo, H.; Ma, F.; Shan, Z. Enhanced Treatment of Synthetic Wastewater by Bioaugmentation with a Constructed Consortium. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Sardar, F.; Khaliq, Z.; Nawaz, M.S.; Shehzad, A.; Ahmad, M.; Yasmin, S.; Hakim, S.; Mirza, B.S.; Mubeen, F.; et al. Tailored Bioactive Compost from Agri-Waste Improves the Growth and Yield of Chili Pepper and Tomato. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 787764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, D.; Ventorino, V.; Fagnano, M.; Woo, S.L.; Pepe, O.; Adamo, P.; Caporale, A.G.; Carrino, L.; Fiorentino, N. Compost and Microbial Biostimulant Applications Improve Plant Growth and Soil Biological Fertility of a Grass-based Phytostabilization System. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Cui, X.; Xie, M.; Zhao, R.; Xu, L.; Ni, S.; Cui, Z. Amendments and Bioaugmentation Enhanced phytoremediation and Micro-ecology for PAHs and Heavy Metals Co-contaminated Soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 426, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Alabresm, A.; Chen, Y.P.; Decho, A.W.; Lead, J. Improved Metal Remediation Using a Combined Bacterial and Nanoscience Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).