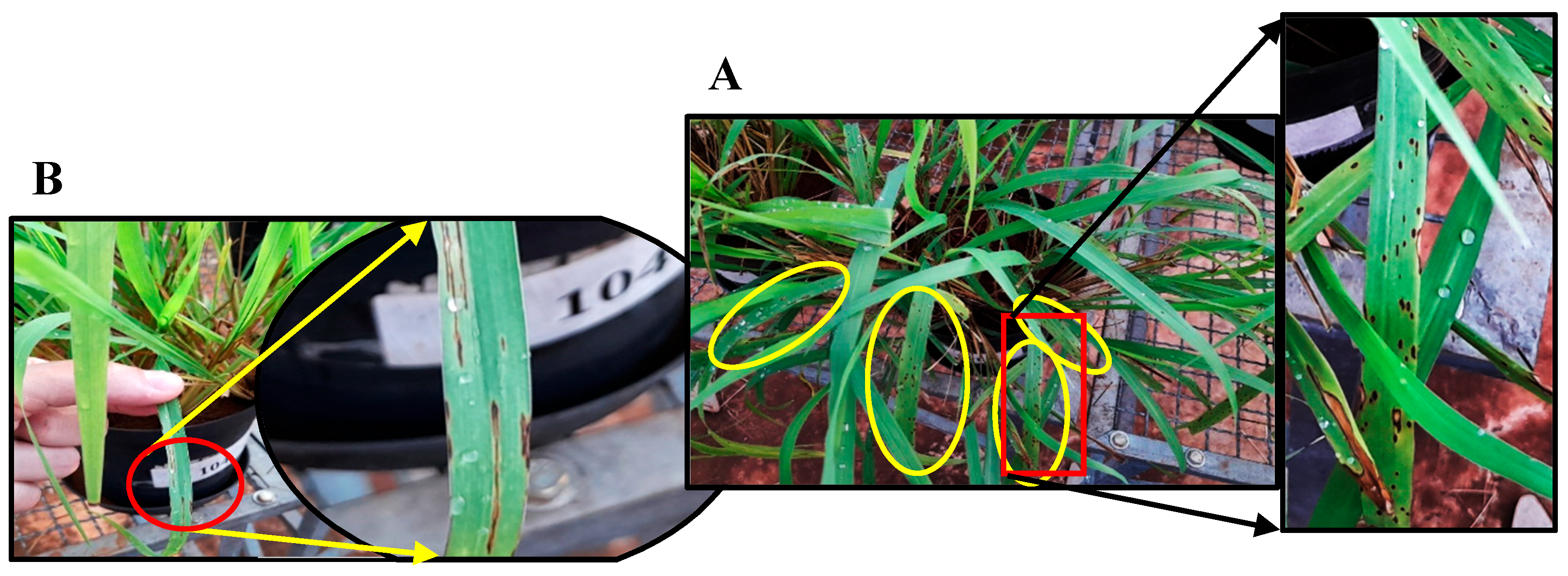

Severity of Leaf Spots Caused by Bipolaris maydis and Cercospora fusimaculans on Panicum maximum Forages Under Phosphate Fertilization and Limestone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

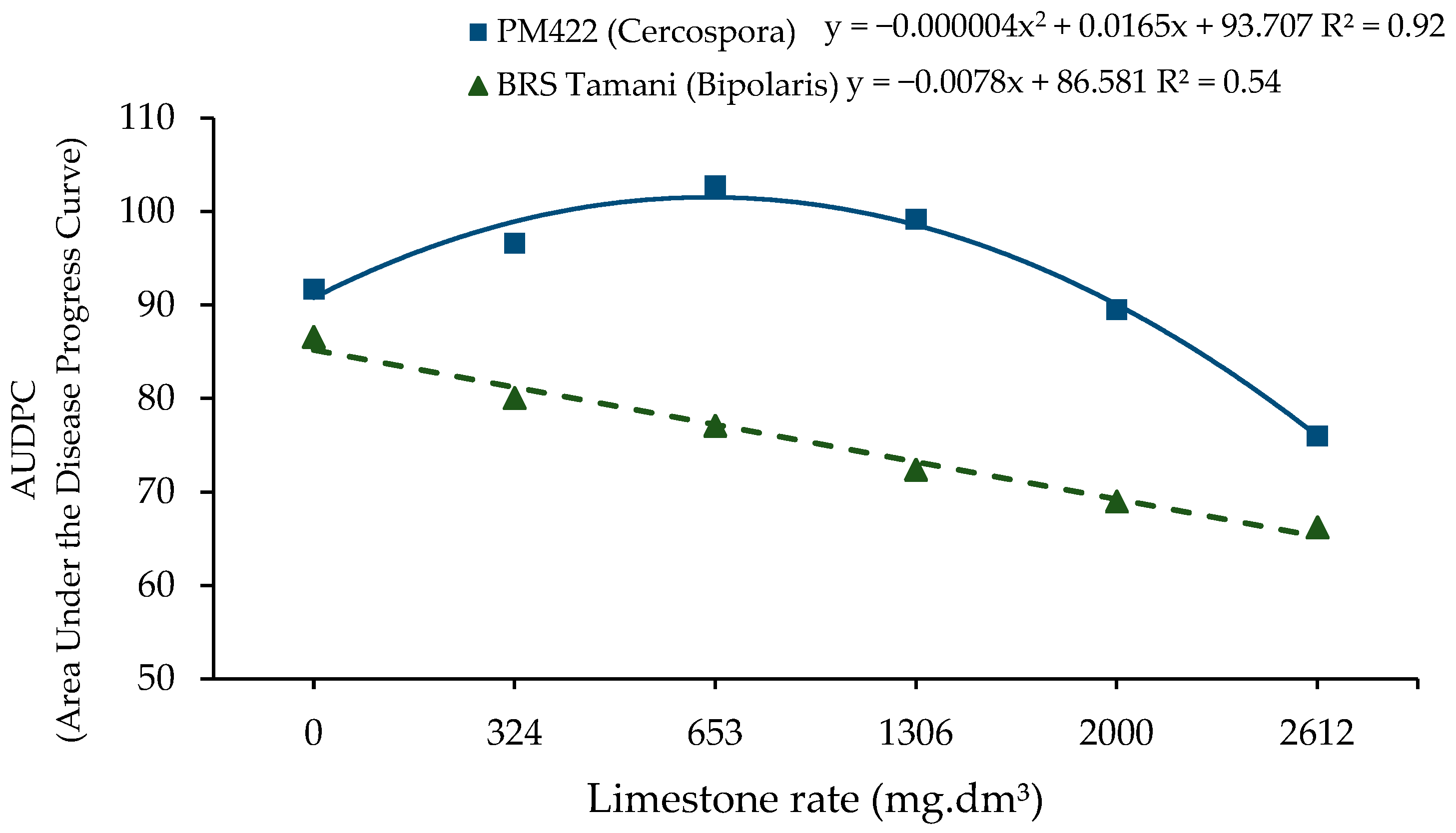

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Agropecuário; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Euclides, V.P.B.; Montagner, D.B.; Macedo, M.C.M.; Araújo, A.R.; Difante, G.S.; Barbosa, R.A. Grazing intensity affects forage accumulation and persistence of Marandu palisadegrass in the Brazilian savannah. Grass Forage Sci. 2019, 74, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeão, R.M.; Resende, M.D.V.; Alves, R.S.; Pessoa Filho, M.A.C.P.; Azevedo, A.L.S.; Jones, C.S.; Pereira, J.F.; Machado, J.C. Genomic Selection in Tropical Forage Grasses: Current Status and Future Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 624584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappacosta, M.; Bustamante, M.; Quarin, C.; Lavia, G. Genetic Transformation of Apomictic Grasses: Progress and Constraints. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 756382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenne, J.M. A Word List of Fungal Diseases of Tropical Pasture Species; Phytopathological Papers; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 1990; Volume 31, p. 177. ISBN 0851986749. [Google Scholar]

- Perrenoud, S. Potassium and Plant Health; International Potash Institute (IPI): Basel, Switzerland, 1990; IPI Research Topics No. 3; 361p, ISBN 3-906535-11-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, E. Mecanismos estruturais na resistência de plantas a patógenos. Summa Phytopathol. 2007, 33, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, E. Soil biota, ecosystem services and land productivity. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charchar, M.J.A.; Anjos, J.R.N.; Fernandes, F.D. Panicum maximum cv. Tanzânia, nova hospedeira de Bipolaris maydis. Fitopatol. Bras. 2003, 28, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, S.R.; Njarui, D.; Mutimura, M.; Cardoso, J.; Johnson, L.; Gichangi, E.; Teasdale, S.; Odokonyero, K.; Caradus, J.; Rao, I.M. Climate-smart Brachiaria for improving livestock production in East Africa: Emerging opportunities. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Grassland Congress 2015—Keynote Lectures, New Delhi, India, 20–24 November 2015; pp. 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, S.E.; Caradus, J.R.; Johnson, L.J. Fungal endophyte diversity from tropical forage grass Brachiaria. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2019, 11, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charchar, M.J.D.; dos Anjos, J.R.N.; Silva, M.S. Leaf spot in elephantgrass in the Cerrado region of central Brazil caused by Bipolaris maydis. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2008, 43, 1637–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemond, P.; Oguntade, O.; Stomph, T.-J.; Kumar, P.L.; Termorshuizen, A.J.; Struik, P.C. Saúde de sementes de milho armazenadas por agricultores no nordeste da Nigéria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 137, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsibo, D.L.; Barnes, I.; Omondi, D.O.; Dida, M.M.; Berger, D.K. Estrutura genética populacional e padrões de migração do fungo patogênico do milho, Cercospora zeina, na África Oriental e Meridional. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 149, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, S. Foliar fungal diseases respond differently to nitrogen and phosphorus additions in Tibetan alpine meadows. Ecol. Res. 2020, 35, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.F. Effect of levels of take-all and phosphorus fertiliser on the dry matter and grain yield of wheat. J. Plant Nutr. 1995, 18, 1159–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csöndes, I.; Balikó, K.; Degenhardt, A. Effect of different nutrient levels on the resistance of soybean to Macrophomina phaseolina infection in field experiment. Acta Agron. Hung. 2008, 56, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, F.N.; Leiva, M.; Chiocchio, V.; Lavado, R.S. Phosphorus fertilization reduces the severity of charcoal rot (Macrophomina phaseolina) and the arbuscular mycorrhizal protection in soybean. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018, 181, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Martinez, A.; Franzener, G.; Stangarlin, J.R. Damages caused by Bipolaris maydis in Panicum maximum cv. Tanzânia. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2010, 31, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.D.; Chermouth, K.S.; Jank, L.; Mallmann, G.; Fernandes, E.T.; Queiróz, C.A.; Carvalho, C.; Quetez, F.A.; Silva, M.J.; Batista, M.V. Reação de híbridos de Panicum maximum à mancha das folhas em condições de infecção natural. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Forage Breeding, Bonito, Brazil, 14–17 November 2011; Embrapa Gado de Corte: Campo Grande, Brazil, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, B.D.; Giehl, R.F.H.; Friedel, S.; Wirén, N.V. Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.; Liao, Y.Y.; Chiou, T.J. The Impact of Phosphorus on Plant Immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Heath, M.C. Role of calcium in signal transduction during the hypersensitive response caused by basidiospore-derived infection of the cowpea rust fungus. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzergue, C.; Chabaud, M.; Barker, D.G.; Bécard, G.; Rochange, S.F. High phosphate reduces host ability to develop arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis without affecting root calcium spiking responses to the fungus. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teixeira, A.C.B.; Gomide, J.A.; Oliveira, J.A.; Alexandrino, E.; Lanza, D.C.F. Distribuição de fotoassimilados de folhas do topo e da base do capim-Mombaça (Panicum maximum Jacq.) em dois estádios de desenvolvimento. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2005, 34, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.D.M.; Mittelmann, A. Doenças do Azevém. Documentos 2009, 279, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, R.; Tewari, R.; Singh, K.P.; Keswani, C.; Minkina, T.; Srivastava, A.K.; De Corato, U.; Sansinenea, E. Plant mineral nutrition and disease resistance: A significant linkage for sustainable crop protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 883970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, H.R.; Frontado, N.E.V.; Tico, M.A.; de Faria Theodoro, G.; Sanches, M.M.; Fernandes, C.D.; Difante, G.D.S. Behavior of Megathyrsus maximus cv. BRS Tamani to brown leaf spot, caused by Bipolaris yamadae, as a function of nitrogen fertilization doses. J. Plant Pathol. 2025, 107, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véras, E.L.d.L.; Difante, G.d.S.; Araújo, A.R.d.; Montagner, D.B.; Monteiro, G.O.d.A.; Araújo, C.M.C.; Gurgel, A.L.C.; Macedo, M.C.M.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Santana, J.C.S. Potassium Fertilization Alters the Morphogenetic, Structural, and Productive Characteristics of Panicum maximum Cultivars. Grasses 2024, 3, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.S.; Frazener, G.; Stangarlin, J.R. Avaliação do dano provocado por Bipolaris maydis em Panicum maximum cv. Tanzânia-1. Dissertation, Marechal Cândido Rondon, State University of Western Paraná, Cascavel, Brazil, 2006; 41p. Available online: https://tede.unioeste.br/handle/tede/1273 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pinto, N.F.J.D.A. Controle químico da “ergot” (Claviceps africana Frederickson, Mantle & de Milliano) ou doença-açucarada e das principais doenças foliares do sorgo (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2003, 27, 939–944. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.A.; Romeiro, R.S.; Resende, R.S.; Dallagnol, L.J. Indução de resistência em plantas a patógenos. In O Essencial da Fitopatologia: Epidemiologia de Doenças de Plantas; Zambolim, L., Júnior, W.C.J., Rodrigues, F.A., Eds.; Universidade Federal de Viçosa: Viçosa, Brazil, 2014; pp. 264–290. ISBN 978-85-60027-37-8. [Google Scholar]

| TRT | pH | Ca++ | Mg++ | K+ | Al+3 | H + Al | S | T | CEC | BS | m | OM | PM1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg dm−3) | ||||||||||||||

| P | CaCO3 | CaCl2 | cmolc/dm3 | % | dag/dm3 | mg/dm3 | ||||||||

| 0 | 4.61 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 5.04 | 0.88 | 5.91 | 1.16 | 14.8 | 24.6 | 2.56 | 4.60 | |

| 326 | 4.72 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 5.00 | 1.20 | 6.20 | 1.38 | 19.40 | 13.10 | 2.58 | 4.62 | |

| 116 | 653 | 4.97 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 4.90 | 1.54 | 6.45 | 1.64 | 23.90 | 5.80 | 2.58 | 4.28 |

| 1306 | 5.12 | 1.06 | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 4.49 | 2.12 | 6.61 | 2.16 | 32.1 | 2.00 | 2.49 | 3.65 | |

| 2612 | 5.62 | 1.86 | 1.67 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 3.80 | 3.66 | 7.46 | 3.66 | 49.10 | 0.00 | 2.45 | 3.86 | |

| 0 | 4.65 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 4.90 | 0.58 | 5.49 | 0.98 | 10.70 | 40.10 | 2.95 | 1.10 | |

| 326 | 4.71 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 4.97 | 0.91 | 5.88 | 1.12 | 15.5 | 18.90 | 2.73 | 1.63 | |

| 19 | 653 | 4.86 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 4.87 | 1.23 | 6.1 | 1.34 | 20.1 | 8.70 | 3.02 | 0.76 |

| 1306 | 5.22 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 5.00 | 2.16 | 7.16 | 2.19 | 30.1 | 1.50 | 2.57 | 0.88 | |

| 2612 | 5.49 | 1.57 | 1.47 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 4.09 | 3.18 | 7.27 | 3.18 | 43.8 | 0.00 | 2.70 | 0.86 | |

| AUDPC Bipolaris maydis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Doses (mg dm−3) | Limestone Doses (mg dm−3) | |||||||

| 0 | 326 | 653 | 1306 | 2612 | SEM | LSD | p-Value | |

| 19 | 33.5 aA | 30.6 aA | 41.1 aA | 34.4 aA | 26.8 aA | 3.97 | 15.55 | 0.1202 |

| 116 | 14.0 bA | 20.0 aA | 15.0 bA | 19.1 bA | 25.1 aA | 3.97 | 15.55 | 0.2673 |

| AUDPC Cercospora fusimaculans | ||||||||

| 19 | 92.4 aAB | 102.2 aA | 95.3 aAB | 84.6 aB | 92.5 aAB | 4.34 | 16.96 | 0.0854 |

| 116 | 81.5 aA | 75.5 bAB | 67.5 bAB | 78.7 aA | 59.3 bB | 4.34 | 16.96 | 0.0029 |

| Forage | P Doses (mg dm−3) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 116 | ||

| AUDPC (Bipolaris maydis) | |||

| Tamani | 113.8 aA | 43.9 aB | <0.0001 |

| PM422 | 29.2 bA | 17.6 bA | 0.0549 |

| PM408 | 24.9 bcA | 14.8 bA | 0.0930 |

| Zuri | 16.2 bcdA | 8.8 bA | 0.2175 |

| PM414 | 9.7 cdA | 14.6 bA | 0.4124 |

| PM406 | 6.0 dA | 12.1 bA | 0.3040 |

| Mean | 33.3 | 18.6 | |

| AUDPC (Cercospora fusimaculans) | |||

| Tamani | 69.1 cA | 44.4 cB | 0.0004 |

| PM422 | 107.2 aA | 75.3 aB | <0.0001 |

| PM408 | 95.4 abA | 55.1 bB | <0.0001 |

| Zuri | 99.9 abA | 93.9 aA | 0.3790 |

| PM414 | 86.8 bcA | 79.7 aA | 0.2992 |

| PM406 | 102.1 abA | 86.6 aB | 0.0248 |

| Mean | 93.4 | 72.5 | |

| Forage | P Doses (mg dm−3) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 116 | ||

| AUDPC (Bipolaris maydis) | |||

| 30 day | 0.0005 | ||

| Tamani | 62.14 aAa | 35.19 aBa | <0.0001 |

| PM422 | 24.01 bAa | 9.81 bBa | <0.0001 |

| PM408 | 15.74 bcAa | 7.44 bBa | 0.0208 |

| Zuri | 9.66 cdAa | 5.8 bAa | 0.2811 |

| PM414 | 5.8 cdAa | 7.76 bAa | 0.5846 |

| PM406 | 3.00 dAa | 7.34 bAa | 0.2243 |

| 60 day | |||

| Tamani | 51.73 aAb | 8.76 aBb | <0.0001 |

| PM422 | 5.22 bAb | 7.85 aAa | 0.4612 |

| PM408 | 9.25 bAa | 7.44 aAa | 0.6136 |

| Zuri | 6.54 bAa | 3.00 aAa | 0.3224 |

| PM414 | 3.90 bAa | 6.85 aAa | 0.4092 |

| PM406 | 3.00 bAa | 4.80 aAa | 0.6129 |

| Forage | Day | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | ||

| AUDPC (Cercospora fusimaculans) | |||

| Tamani | 22.00 cB | 34.78 cA | 0.0002 |

| PM422 | 42.75 abA | 48.51 abA | 0.0935 |

| PM408 | 40.48 bA | 34.84 cA | 0.1006 |

| Zuri | 44.75 abB | 52.17 aA | 0.0311 |

| PM414 | 41.20 bA | 42.09 bcA | 0.7957 |

| PM406 | 50.06 aA | 44.32 abA | 0.0945 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frontado, N.E.V.; Difante, G.d.S.; Araújo, A.R.d.; Macedo, M.C.M.; Montagner, D.B.; Sanches, M.M.; Fernandes, C.D.; Silva, H.R.d.; Theodoro, G.d.F.; Tico, M.A.; et al. Severity of Leaf Spots Caused by Bipolaris maydis and Cercospora fusimaculans on Panicum maximum Forages Under Phosphate Fertilization and Limestone. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232506

Frontado NEV, Difante GdS, Araújo ARd, Macedo MCM, Montagner DB, Sanches MM, Fernandes CD, Silva HRd, Theodoro GdF, Tico MA, et al. Severity of Leaf Spots Caused by Bipolaris maydis and Cercospora fusimaculans on Panicum maximum Forages Under Phosphate Fertilization and Limestone. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232506

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrontado, Néstor Eduardo Villamizar, Gelson dos Santos Difante, Alexandre Romeiro de Araújo, Manuel Claudio Motta Macedo, Denise Baptaglin Montagner, Marcio Martinello Sanches, Celso Dornelas Fernandes, Hitalo Rodrigues da Silva, Gustavo de Faria Theodoro, Mariane Arce Tico, and et al. 2025. "Severity of Leaf Spots Caused by Bipolaris maydis and Cercospora fusimaculans on Panicum maximum Forages Under Phosphate Fertilization and Limestone" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232506

APA StyleFrontado, N. E. V., Difante, G. d. S., Araújo, A. R. d., Macedo, M. C. M., Montagner, D. B., Sanches, M. M., Fernandes, C. D., Silva, H. R. d., Theodoro, G. d. F., Tico, M. A., Gurgel, A. L. C., Rodrigues, J. G., & Gonzalez, A. (2025). Severity of Leaf Spots Caused by Bipolaris maydis and Cercospora fusimaculans on Panicum maximum Forages Under Phosphate Fertilization and Limestone. Agriculture, 15(23), 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232506