Abstract

Agriculture puts significant pressure on freshwater sources, which motivates the use of reclaimed water for irrigation as a promising alternative to reduce freshwater demand while also providing nutrients. This study applies Life Cycle Assessment to determine the environmental impacts of irrigating a DOCa La Rioja vineyard with reclaimed water in the cultivation of organic grapes (scenario A) and compares it with an irrigation practice that uses canal water combined with organic extra-fertilisation (scenario B), accounting for differences in wastewater treatment processes. Results show that scenario A reduces impacts in categories such as global warming (16.2%) and freshwater eutrophication (25.6%) compared with scenario B, primarily due to the lower emissions associated with reclaimed water treatment. Additionally, a water balance was performed for the plot, which indicated that current inputs currently exceed losses in the region, so water stress is not observed; however, this situation may change in the near future due to population growth and climate change. These findings underscore the need to enhance the efficiency of the reclaimed water production, primarily by optimising its energy requirements, to support sustainable water use in agricultural systems.

1. Introduction

Population growth and rising food demand have driven a shift toward intensive agriculture, characterised by heavy agrochemical use and mechanisation that degrade soil quality [1]. These fertilisers and pesticides are later released into the soil, water, and air as nitrous oxides, ammonia, or phosphates, posing risks to humans and animals and contributing to climate change [2]. As a result, the sector is responsible for approximately 17% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [3]. Additionally, the agriculture sector represents approximately 70% of global freshwater demand [4]. In Europe, about 44% of water use is allocated to agricultural irrigation, whereas in the United States this figure falls to 37%, with industrial and energy production constituting other major uses [5]. Currently, around 60% of irrigated crops worldwide are at high or extremely high risk of water stress, highlighting the importance of addressing this issue [6].

Reclaimed water, also known as recycled water or reuse water, refers primarily to municipal or domestic wastewater that has undergone treatment for non-potable uses. In the agricultural sector, using reclaimed water presents significant advantages, such as reducing fertiliser consumption (and its related emissions) and alleviating the sector’s pressure on freshwater resources. Despite its benefits, the overall contribution of reclaimed water remains limited. Around 1 billion m3 of urban wastewater currently reused in the European Union accounts for less than 0.5% of total freshwater extractions [7]. Spain leads the reclaimed water production, generating approximately 347 hm3 per year, of which around 71% is allocated to crop irrigation [8]. To address concerns regarding its use, particularly in relation to potential contaminants, the Royal Decree 1085/2024 establishes minimum water quality parameters for safe reuse. This regulation ensures that reclaimed water meets specific standards depending on its intended application, reinforcing its safety and reliability [9].

The reuse of treated wastewater aligns with the principles of the circular economy (CE) [10], as water circularity supports sustainable production and consumption through resource recovery and the reintegration of treated water into a system [11]. Furthermore, this approach is directly linked to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [12], such as SDG 6, which aims to improve water quality by treating and safely reusing wastewater for irrigation; and SDG 12, which promotes responsible consumption and production through sustainable resource use, such as water reuse in agricultural practices.

Although grape cultivation stands out as a highly widespread and economically significant activity worldwide, it contributes around 2% of GHG emissions from the agricultural sector [13]. Regarding world wine production, Spain ranks third, following France and Italy, with around 28.3 million hL [14]. In Spain, the region of La Rioja stands out as one of the most renowned wine-producing areas, both nationally and internationally, accounting for approximately 26.8% of the country’s total wine production [15]. Additionally, the region has held the Qualified Designation of Origin Rioja (DOCa) since 1991, representing the quality and authenticity of this product [16]. Nevertheless, vineyards in Mediterranean areas face seasonal droughts that result in water shortages, potentially compromising yield and grape quality [5]. Consequently, the use of reclaimed water for agricultural irrigation is becoming an increasingly relevant strategy to address the scarcity of this resource [17].

Advocating for a sustainable agricultural sector requires the use of tools that help quantify its environmental impacts. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) stands out for its scientific recognition for measuring key impact categories in agricultural systems, such as global warming potential, acidification and eutrophication [18,19,20]. However, to provide a comprehensive view of the impacts generated by the system under study, the inclusion of ecosystem services (ES) is receiving increasing attention [21]. These services refer to the direct, indirect, and intermediate benefits that ecosystems provide to people, emphasising their contribution to human well-being [22]. Although ES encompasses a wide variety of functions, this study focuses on those related to the water cycle, specifically water regulation, to support site-specific irrigation strategies and assess the actual water availability in the Rioja region.

In the literature, there is a discrepancy regarding the environmental advantages or drawbacks associated with the use of regenerated water, as some studies suggest lower impacts than conventional irrigation, while others suggest the opposite [23]. This difference primarily depends on the technologies used for reclaimed water production, as well as the system design (such as pumping distance to the crop) and energy mix [24]. Moreover, only a few studies have assessed the impacts of reclaimed water use in vineyards. For instance, Canaj et al. [17] examined vineyards in Apulia, Italy, where reclaimed water generation relies on filtration and UV disinfection, while Kalboussi et al. [24] evaluated a baseline scenario in France in which reclaimed water is treated in a lagoon and through tertiary treatment, comparing it with alternative irrigation scenarios. These studies highlight the need for region-specific assessments and for the evaluation of different reclaimed water production technologies.

In this context, the present study addresses this gap by pursuing two objectives: (i) evaluating the potential environmental impacts of implementing an irrigation strategy using reclaimed water in a vineyard in La Rioja, where fertiliser demand is reduced due to the organic content of this water source; and (ii) estimating water stress in local conditions. This approach enables the identification of the main benefits and limitations from a life-cycle perspective, with the aim of promoting its future implementation in the agricultural sector and informing the development of related policies. Furthermore, the environmental performance of this strategy is compared with an irrigation system using treated canal water, in which nutrients are supplied solely through organic fertilisation. The findings provide a clearer understanding of the environmental implications of using reclaimed water for agricultural irrigation and demonstrate its potential as a sustainable alternative in the global context of increasing water scarcity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Evaluated Scenario

This research was conducted in a vineyard located in the La Rioja Alta subzone, northern Spain (42°26′34.1″ N, 2°30′58.2″ W) (see Figure 1), one of the three subzones within the DOCa. The region is characterised by a continental Mediterranean climate, with an annual rainfall of approximately 579 mm in 2024. Additional climate data, including monthly rainfall and temperature, are provided in Tables S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Materials (SMs) [25]. The vineyard covers a total cultivated area of about 2 ha within a 2.6 ha plot, which is completely flat. The production reaches around 5 t/ha of ‘Tempranillo’ grapes, yielding approximately 3.5 t/ha of wine. The soil is silty loam, low in organic matter and has low salinity. It is also important to highlight that this vineyard operates under certified organic farming practices, which limit the use of agrochemicals, applying only the permitted doses.

Figure 1.

View of the ICVV facilities with the vineyard area [26].

2.2. Environmental Assessment

The environmental impacts of this system are quantified and analysed using an attributional LCA approach, in accordance with the guidelines established in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 [27,28]. The following subsections outline the different phases of the methodology: (i) goal and scope definition, (ii) life cycle inventory analysis, (iii) life cycle impact assessment, and (iv) interpretation of the results.

2.2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The objective of this LCA study is to assess the environmental impacts of using reclaimed water for irrigation process in an organic vineyard located in the Rioja DOCa, aiming to identify potential benefits or drawbacks of applying this practice. The environmental assessment is carried out by comparing the use of reclaimed water with a conventional irrigated scenario. To represent this, two functional units were selected:

- FU1: 1 ha of cultivated land to evaluate the effects of irrigation in agricultural practices.

- FU2: 1 kg of harvested grapes to account for production yield in the environmental profile.

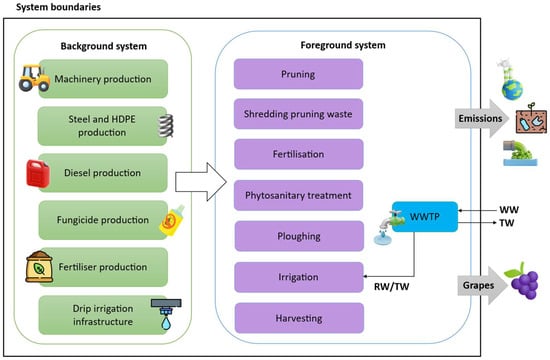

These two functional units were selected to provide complementary perspectives: FU1 allows assessment of environmental impacts at the field scale, which is useful for farm management and regional comparisons, while FU2 enables comparisons of product-level efficiency, which is more commonly reported in the literature. The system boundaries follow a cradle-to-farm gate approach (see Figure 2), including raw material extraction (e.g., fossil fuels, steel), agrochemicals and machinery production, infrastructure related to irrigation process and field operations. Furthermore, no allocation is performed, as the total environmental impacts are assigned to the only system’s product, i.e., the grapes. Pruning residues from the vineyards are shredded and incorporated into the soil, acting as an organic amendment.

Figure 2.

System boundaries of grape cultivation with the main activities and processes considered. RW is only considered for Scenario A, while TW is used in Scenario B. WWTP: Wastewater Treatment Plant; WW: Wastewater; TW: Treated Water; RW: Reclaimed Water.

Crop Management

The 2024 crop season under study starts in January with pruning (about 700 kg/ha of pruning wood collected, shredded and used as soil enrichment) and ends with the harvest in September. During April, an organic fertilisation (5% N, 5% P2O5 and 15% K2O) is applied at a rate of around 700 kg/ha. Between May and July, a series of phytosanitary treatments are carried out, in which an atomiser is used to apply approximately 25 kg/ha of solid sulphur (98.5% sulphur), 6.75 L/ha of liquid sulphur (82.5% sulphur), 2.5 kg/ha of solid copper (28% Cu) and 2 L/ha of essential oils. For the dispersion of these treatments, approximately 1800 L/ha of water is required. Finally, in July, superficial tilling is carried out with a chisel plough before the harvest.

Drip irrigation was implemented using a 1.35 kW electric pump, providing an irrigation rate of 273.6 m3/ha in August, before harvesting. The characteristics of the reclaimed and discharged water are shown in Table 1. In terms of required infrastructure, approximately 600 kg/ha of galvanised steel wire and 1250 kg/ha of galvanised steel posts were installed.

Table 1.

Characterisation of the reclaimed water used for the irrigation of the vineyard.

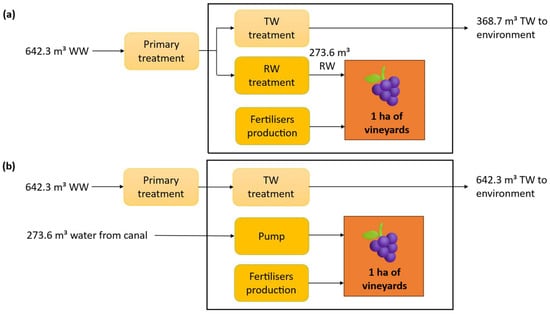

Regarding reclaimed water production, only the treatment stages directly related to its generation and agricultural reuse were included within the system boundaries. Preliminary and primary treatment steps, which are performed regardless of whether the water is reclaimed or discharged, were excluded. In the scenario where reclaimed water is produced, additional treatment is applied to ensure its suitability for irrigation, based on a membrane bioreactor and ultraviolet disinfection if the water quality is not sufficient. Conversely, when the effluent is discharged into the environment (Scenario B), it undergoes a standard secondary treatment process. The descriptions of the evaluated scenarios are detailed below and illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of the evaluated scenarios depending on whether reclaimed water (RW) or treated water (TW) is used. Although the type of fertiliser used is the same, a higher amount is required in Scenario B. WW: wastewater, (a): Scenario A, (b): Scenario B. The diagram design is adapted from Kalboussi et al. [24].

- Scenario A: Corresponds to the irrigation process using reclaimed water in the vineyard.

- Scenario B: Irrigation process is based on water pumped from a canal, where treated water is stored. The nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, are provided through organic fertilisers. The amount supplied by organic fertiliser is 3.9 kg of nitrogen and 1.1 kg of phosphorus.

2.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory

The environmental impacts were calculated using a combination of primary data, obtained directly from the farmer through a series of questionnaires regarding the field operations conducted for grape cultivation (including machinery used, diesel consumption, types and amounts of agrichemicals used, irrigation method, pumping electricity consumption and other relevant operational details). Secondary data, corresponding to the background system (e.g., agrochemical production, or infrastructure related to the irrigation system), were extracted from the Ecoinvent® database, version 3.8 [29]. The life cycle inventory was modelled in the SimaPro software version 10.0 [30]. The reclaimed water is produced at the Institute of Grapevine and Wine Sciences (in Spanish, Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y el Vino-ICVV) facilities from wastewater generated by the winery itself. This process was modelled using primary data provided by the facility managers. The inventory data for grape production are shown in Table 2. A summary of the data used and their sources is presented in Tables S3 and S4 in the SMs.

Table 2.

Main inventory data associated with the viticulture system expressed per hectare of land.

A variety of empirical models were used to estimate on-field emissions resulting from the application of pesticides and fertilisers. These include: (i) the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines for National GHG Inventories to quantify both direct and indirect N2O emissions [31]; (ii) the nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ammonia (NH3) emission models from the European Environment Agency (EEA) and the European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme (EMEP) [32]; (iii) the SQCB model developed by Faist Emmenegger et al. [33] for calculating nitrate (NO3−) emissions; (iv) the SALCA-P method for estimated phosphorus leaching and runoff, conducted by Agroscope [34]. Additionally, air, water and soil emissions associated with the use of phytosanitary products are estimated according to the European Commission’s Product Environmental Footprint Category Rules [35].

In relation to on-field emissions resulting from land use change, both indirect (iLUC) and direct (dLUC) land use change emissions were also considered. On the one hand, iLUC refers to emissions arising from the transformation of land use in other areas as a consequence of the land being used for cultivating the assessed crop, as calculated following the method proposed by Schmidt et al. [36] and considering the productivity capacity factor outlined by Haberl et al. [37]. On the other hand, dLUC refers to emissions caused by management practices implemented on the land under study, such as the handling of pruning waste in the vineyard, which is shredded and left on the soil [36].

2.2.3. Impact Assessment

The environmental impacts of the grape cultivation with reclaimed water was assessed on the basis of nine impact categories with high importance in the agricultural sector: Global Warming (GW), Stratospheric Ozone Depletion (SOD), Terrestrial Acidification (TA), Freshwater Eutrophication (FE), Marine Eutrophication (ME), Terrestrial Ecotoxicity (TET), Freshwater Ecotoxicity (FET), Marine Ecotoxicity (MET), Fossil Resource Scarcity (FRS) and Water Scarcity (WS). These categories are widely used in agricultural LCA studies [38], and they are quantified using the ReCiPe 2016 v1.07 Hierarchist Midpoint World (2010) method [39]. Additionally, water scarcity was also assessed using the Available WAter REmaining (AWARE) method v1.2c [40], providing a comprehensive metric for assessing water scarcity impacts with region-specific characterisation factors.

Moreover, the ReCiPe 2016 V1.07 Hierarchical Endpoint World (2010) H/H method [39] was applied to compare the valorisation profiles of both scenarios and determine which one presents a more favourable environmental performance. This endpoint approach provides a single score representing the overall environmental impacts, facilitating the communication and interpretation of the results, quantifying the relative severity of impacts in three categories: Human Health (HH), Ecosystems (E) and Resources (R).

2.3. Seasonal Water Yield

Given the increasing pressure exerted on water resources both in agriculture and to meet human consumption needs, it is essential to design strategies for optimising water use based on its availability and periods of higher or lower water stress. To this end, the Seasonal Water Yield model from InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs) was used. This model allows for the estimation of the amount of water available in a region during a given season, taking into account factors such as land use, monthly precipitation, evapotranspiration, topography and vegetation type [41]. This is fundamental for proper resource management, evaluation of the influence of land use on water availability and support for planning and sustainable management of water resources. The required data includes maps of monthly precipitation in the region [42], maps of monthly evapotranspiration [43], elevation and land use maps [44,45], soil classification maps based on drainage capacity, biophysical properties of different land uses [46] and the number of rainfall events in the region [47].

The outputs of the model allow for a complete water balance assessment in the plot, enabling the identification of possible accumulation or depletion of water within the watershed. This is calculated using Equation (1):

where corresponds to the change in the water balance, is precipitation (mm), is the accumulated recharge from upslope (mm), is the recharge that infiltrates and is available for evapotranspiration (mm), is the additional system recharge (can be positive or negative) (mm), is irrigation (mm), is quickflow (mm), is baseflow (mm) and is evapotranspiration (mm).

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Impact Profile: Midpoint Approach

Table 3 shows the results of the environmental impacts of grape cultivation using reclaimed water (Scenario A) and treated water with organic extra fertilisation (Scenario B).

Table 3.

Environmental impacts per each one of the analysed scenarios.

Regardless of the FU used, scenario A yields better results across all assessed categories, with the smallest differences observed in SOD and WS. In the case of WS, this is expected, as although the type and treatment of water differ in both cases, the quantity used is the same. The results for SOD are also very similar, since this category is directly related to on-field emissions, which include emissions resulting from the use of organic fertilisers and approved pesticides, as well as those associated with land use change, and are identical in both cases. On the other hand, the categories showing the most significant differences are TA, FE, ME, FET and MET. These discrepancies arise from the fact that, in Scenario B, the water undergoes only secondary treatment before being discharged into the environment, leading to a higher release of substances into aquatic systems. In contrast, in Scenario A, the use of reclaimed water enables nitrogen and phosphorus to be directly utilised as nutrient sources for the crop, thereby reducing their release into the environment.

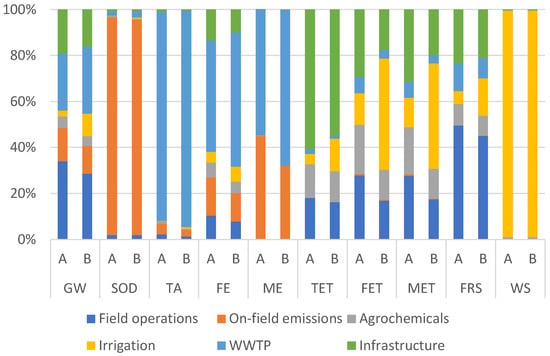

The main hotspot is wastewater treatment, since 642 m3 of wastewater must be processed to yield only 273 m3 of irrigation-quality reclaimed water, equating to a recovery rate of just 0.43 m3 per cubic metre treated at the WWTP, where the production of the necessary energy is the process that contributes the most to the environmental impact in this subsystem. This is followed by the impacts related to the drip irrigation system, particularly in Scenario B, where the energy required to pump water from the canal is higher than that needed for reclaimed water. Other relevant contributions include the production of the steel and polyethylene used to support the vineyard, field operations and on-field emissions resulting from agrochemical use. The impacts associated with agrochemical production are not particularly significant, exceeding 20% of the total impacts only in FET and MET (Figure 4). This outcome is expected, as the case study concerns an organic farm that promotes minimal use of such compounds.

Figure 4.

Percentage distribution of environmental impacts per year in each category analysed and their causes. A: Reclaimed water irrigation scenario; B: Canal irrigation scenario; GW: Global Warming; SOD: Stratospheric Ozone Depletion; TA: Terrestrial Acidification; FE: Freshwater Eutrophication; ME: Marine Eutrophication; TET: Terrestrial Ecotoxicity; FET: Freshwater Ecotoxicity; MET: Marine Ecotoxicity; FRS: Fossil Resource Scarcity; WS: Water Scarcity; WWTP: Wastewater Treatment Plant.

3.1.1. Global Warming

Impacts on GW are primarily driven by carbon dioxide, dinitrogen monoxide and methane emissions [48]. Carbon dioxide is the predominant contributor, accounting for approximately 74% of the impact across all scenarios. The main sources of these emissions are: (i) field operations, particularly due to diesel combustion and tillage machinery production; (ii) infrastructure, where steel production and the electricity needed account for almost all the emissions; and (iii) wastewater treatment, mainly due to electricity consumption. In this category, both iLUC and dLUC emissions are relatively minor. dLUC only offsets around 7% of the total emissions, due to the low amount of pruning residues remaining on the field, while iLUC is even less significant.

3.1.2. Stratospheric Ozone Depletions and Terrestrial Acidification

In SOD, the impacts in both scenarios are almost entirely attributable to the decomposition of nitrogen-based fertilisers into N2O, which accounts for over 99% of the total impacts. Emissions are nearly identical in both cases because the amount of nitrogen used for fertilisation is the same. In Scenario B, nitrogen is provided only through organic fertilisation, while in Scenario A it comes from both organic fertilisation and nitrogen contained in the reclaimed water.

Conversely, in TA, more than 90% of the impacts in both scenarios stem from water treatment. Nitrogen dioxide released into the air during this process is the main contributor. When combined with the large volume of water treated, this makes water treatment the primary driver of impacts in this category. Other contributors with smaller shares include ammonia from field emissions and sulphur dioxide generated during the production of infrastructure and chemicals.

3.1.3. Freshwater and Marine Eutrophication

The wastewater treatment process is also the main contributor in both impact categories, accounting for 49% and 58% of the impacts in Scenario A and B for FE, respectively. In the ME category, the treatment represents about 55% in Scenario A and 68% in Scenario B. The second most relevant source, although considerably lower, is the field emissions from agrochemical application. In the ME category, they represent about 45% in Scenario A and 32% in Scenario B, while in FE, they account for 17% and 12% in Scenario A and B, respectively. These field emissions in the FE category are primarily attributed to phosphates released as a result of the transformation of phosphorus from fertilisers (17%), followed by other phosphates and phosphorus emissions mainly generated during wastewater treatment, as well as BOD5 and COD emissions associated with steel production, primarily due to the use of ferronickel. Additionally, impacts arise from the production of tillage machinery and the discharge of treated water into the environment. On the other hand, nitrogen emissions from WWTP are the predominant contributors to impacts in ME, responsible for about 55% of the total, followed by nitrate emissions resulting from the decomposition of nitrogen-based fertilisers.

3.1.4. Terrestrial Ecotoxicity

In TET, the main hotspot across all scenarios is the production of infrastructure required for the vineyard, particularly steel, which is the most extensively used material. These impacts are primarily caused by substances such as copper, chromium and zinc, each contributing at least 8% of the total impact. Following this, field operations account for approximately 18% of the contributions in both scenarios, mainly due to tillage machinery production, while agrochemical production contributes around 14%, due to the copper used.

3.1.5. Freshwater Ecotoxicity and Marine Ecotoxicity

Regarding FET and MET, the distribution of impacts is relatively similar. In Scenario A, the main hotspot is the steel production required for vineyard infrastructure, accounting for approximately 29% of the total impact. This is followed by field operations (around 28%), particularly the production of tillage equipment, and agrochemical production at roughly 21%, mainly due to the copper used. In contrast, in Scenario B, the primary contributor is the drip irrigation infrastructure, responsible for about 47% of the impacts. This is mainly due to the pump, which has a significantly higher power requirement than the one used for reclaimed water, as it must operate over a longer distance. Field operations and the steel needed to support the vineyard structure follow, each contributing around 17 to 20%. The main contributing substances in both categories are copper, zinc and nickel, each with a contribution exceeding 6%.

3.1.6. Fossil Resource Scarcity and Water Scarcity

Field operations represent the main hotspot in terms of FRS, consistently accounting for over 45% of the total impacts across all scenarios. This is primarily due to diesel production, which contributes more than 50% of the impacts, followed by the energy consumption related to tillage machinery production because of the large quantities of fuel and materials required.

Regarding WS, the majority of impacts are linked to the irrigation process, with both scenarios using approximately 4.4 cubic metres of water. Although the volume consumed is the same, the source of the water is a crucial factor. While impacts are similar in both cases, Scenario A uses reclaimed water, which reduces net pressure on freshwater resources by promoting circularity and lowering dependence on surface or groundwater, an important aspect to consider.

3.2. Environmental Impact Profile: Endpoint Approach

The environmental results were expressed as a single overall score to facilitate the comparison between the evaluated scenarios. In this study, only the impact categories previously selected for the environmental assessment at the midpoint level (GW, SOD, TA, FE, ME, TET, FET, MET and FRS) are considered for the estimation of the single environmental score, in view of the corresponding weighting and normalisation factors. Among these, GW contributes to both HH and E, SOD to HH, FRS contributes to R, while the remaining impact categories contribute to E. The findings (see Table 4) from the midpoint analysis are confirmed: the scenario using reclaimed water presents a better overall environmental performance, with a total impact 23% lower than scenario B. Although the impacts associated with the additional fertilisation provided by the reclaimed water are not particularly significant, the main environmental burden in scenario B arises from the substances discharged into the environment with the treated wastewater. Regarding the distribution, in Scenario A, approximately 68% of the impacts are attributed to the HH category, 29% to E and 3% to R. In contrast, Scenario B shows a higher proportion of impacts in the Ecosystems category, as previously explained, increasing to 35%, while the contribution to Human Health decreases to 62% and Resources remains constant at 3%.

Table 4.

Endpoint damage per scenario expressed in milli points (mPt). A: Reclaimed water irrigation scenario; B: Canal irrigation scenario.

Therefore, the use of reclaimed water exhibits better environmental performance, demonstrating its viability from an environmental perspective in water-stressed regions by alleviating the pressure exerted by agriculture on available freshwater resources, thereby allowing these to be prioritised for human consumption. Furthermore, much of its environmental impact comes from the treatment technology used, suggesting that enhancing this process could reduce the overall impact, showing that there is still plenty of potential for improving its environmental efficiency [24].

3.3. Water Yield Assessment

The Seasonal Water Yield model provides a comprehensive set of key parameters to assess water availability at a specific location, which is essential for designing effective erosion control and irrigation strategies. To analyse the water cycle within the study area, the model generates several outputs. One of the most relevant is the annual surface runoff map, which indicates the volume of water that does not infiltrate the soil but instead flows across the surface towards downstream water bodies, potentially increasing erosion risk. For the specific plot where the vineyard is located (see Figure S1 in the SMs), the estimated quickflow is 165.61 mm per year, representing the volume of water that runs off annually due to precipitation.

Based on this result, along with the data from the other maps generated by the model—such as annual precipitation, water recharge and evapotranspiration—and using the specific value calculated for the plot, these inputs can be used in Equation (1) to determine the overall water balance:

This positive value indicates a net water accumulation within the area, suggesting that the inputs from precipitation, upslope recharge, local infiltration and irrigation exceed the losses caused by surface runoff, baseflow and evapotranspiration. Consequently, no water stress is expected in the vineyard plot during the evaluated period. While the absence of drought conditions supports vine physiology and yield, it should be noted that moderate water deficit can enhance grape composition by increasing sugars, phenolic compounds and anthocyanins. Conversely, severe or prolonged water stress may reduce berry size, yield, and negatively affect fruit balance [49].

However, these findings must be interpreted within the temporal and spatial limitations of the Seasonal Water Yield model. The outputs represent average annual conditions and do not capture seasonal variability or potential future climate scenarios. Therefore, the positive water balance reported here should be considered as a short-term result. Long-term monitoring and the integration of dynamic climate projections are recommended to better assess future water availability and its implications for vineyard sustainability.

4. Discussion

When evaluating the results obtained from the use of reclaimed water, a literature review of other studies focused on vineyards was conducted. Canaj et al. [50] studied a pilot project located in southern Italy, where irrigation was carried out with a 50:50 mix of reclaimed and groundwater (3160 m3/ha) using drip irrigation. The reclaimed water underwent tertiary treatment, including disc filtration and UV disinfection. It is important to highlight that, compared to the conventional scenario of 100% groundwater irrigation, the incorporation of reclaimed water led to a 9% reduction in crop yield, although this is more associated with soil quality than with water issues. The values reported by Canaj et al. [50] for the different impact categories per kilogram of harvested grapes were: 0.26 kg CO2 eq for GW, 0.17 g P eq for FE and 45.2 g N eq for ME. The role of the irrigation process has a significant contribution in their study, which is consistent with the findings of this manuscript. Although irrigation levels were more than eleven times higher, the associated impacts accounted for around 30% of the total in GW, approximately the same as in the present study, suggesting that the technology used here could still be optimised to achieve substantially lower impacts. In FE, the values reported by Canaj et al. [50] are also lower—almost 50% less than those found in this study. This difference can be explained by the fact that, in this study, the majority of impacts are generated by emissions associated with the water treatment process, which is not considered in the study by Canaj et al. [50]. However, in the case of ME, the impacts reported in this study are lower, primarily due to the lower nitrogen fertilisation rate applied, approximately 40 kg/ha compared to 135 kg/ha in Canaj et al. [50]. The higher application rate in their study leads to greater nitrate emissions, which are the main contributors to impacts in this category [51,52].

Another relevant study is located in La Rioja, where an organic system was examined. Agraso-Otero et al. [53] reported the impacts of an unirrigated vineyard. The impacts reported per kg of grapes were: 15.31 g CO2 eq for GW, 1.36 g SO2 eq for TA, 0.11 g P eq for FE and 0.69 g N eq for ME. These impacts are considerably lower than those reported in the present study, especially for GW, as a significantly higher amount of pruning residues was returned to the soil, which helped reduce emissions in GW. Additionally, in this study, the crop yield was lower compared to that reported by Agraso-Otero et al. [53]. According to the farmers, this decrease was due to pests and animals that attacked the vineyard, although yields are usually similar to those reported in that study.

An additional non-irrigated scenario in the region was conducted by Gazulla et al. [54]. Values of 503 g CO2 eq for GW and 2.1 g SO2 eq for TA were reported per 0.75 L bottle of wine. Given that 1.27 kg of grapes are required for one bottle, this corresponds to 396 g CO2 eq and 1.7 g SO2 eq per kg of grapes. For GW, the above value is approximately 30% higher than this research with reclaimed water. This may be attributed to the application of 3.5 tons per hectare of fertilisers, whose production and use result in considerable emissions. In contrast, for the category TA, the value is 91% lower, as the study by Gazulla et al. [54] did not include pesticide production within its system boundaries; an omission that likely excludes relevant SO2 emissions, which are significant contributors in this category.

Although the main contributor to the environmental profile is related to irrigation practices, it is also important to consider that organic management strategies directly influence soil and nutrient dynamics. Organic practices, such as the return of pruning residues to the soil and reduced agrochemical inputs, can significantly influence nitrogen cycling and soil carbon dynamics [55]. Organic amendments may increase soil organic matter and enhance carbon sequestration, thereby mitigating greenhouse gas emissions [56]. However, the use of organic fertilisers can also lead to greater variability in soil nitrogen availability and potentially higher N2O emissions if not carefully managed [57]. Therefore, the complex interactions between soil management, nutrient cycling, and carbon storage are highly relevant for providing a realistic assessment of the environmental impacts of these systems.

While this study is limited to a specific vineyard located in La Rioja, characterised by a Mediterranean–continental climate with dry summers, mean annual precipitation of approximately 500 mm and silty loam soil, the main contributor to the environmental impacts is the water treatment process rather than local climatic or soil conditions. Consequently, the general patterns observed here may be transferable to other wine-growing regions facing water scarcity. It remains essential to optimise the energy consumption of the selected technology for reclaimed water production, as its environmental viability largely depends on this factor.

5. Conclusions

This manuscript assesses the environmental profile of an organic vineyard irrigated with reclaimed water in the DOCa La Rioja. Scenario A, using reclaimed water, is compared with Scenario B, where irrigation is supplied with treated canal water. Both scenarios include wastewater treatment, although implemented differently. The reclaimed water scenario shows better environmental performance than treated canal water, supporting its viability for water-stressed regions by preserving freshwater for human consumption. In contrast, the scenario with treated water is significantly penalised due to the discharge of treated water into the environment, contributing nitrogen, potassium, COD and BOD5. The main hotspot in both systems is the water treatment process itself, suggesting that there is still a challenge to improve the technology, and further research is needed to minimise its environmental impacts. Furthermore, this study highlights the effective environmental practices implemented in the vineyard and demonstrates that in this Designation of Origin, one of the most prestigious in the world, it is indeed possible to produce wine with a low environmental impact, supporting the transition towards a more sustainable wine sector in the long term. Although these results were obtained in a specific region with particular characteristics, they may be extrapolated to other regions, as the main environmental impacts arise from factors largely independent of the vineyard itself, such as reclaimed water production.

Regarding water availability, the water balance analysis for the region showed a net positive value, indicating that the watershed is not currently under water stress. These findings must be interpreted within the temporal and spatial limitations of the model, which does not capture seasonal variability or potential future climate scenarios. However, this does not negate the importance of strategies such as water reuse. With the ongoing effects of climate change, including increasing global temperatures, water availability is expected to decrease in the coming years. Implementing sustainable irrigation practices now can help ensure long-term resilience in agriculture. In addition, more in-depth consideration of interactions between soil management, nutrient cycling, and carbon storage is needed to fully understand their role in shaping future emission profiles and vineyard sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15232505/s1. Table S1: Mean temperature of the region from 2024 to 2018; Table S2: Monthly mean rainfall of the region from 2018 to 2024; Table S3: Source of the data used for the environmental analysis; Table S4: Ecoinvent processes used for each activity; Figure S1: Annual surface runoff map of La Rioja. The vineyard plot under analysis is highlighted by a white circle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.A.-O. and S.G.-G.; methodology, A.A.-O. and S.G.-G.; software, A.A.-O.; validation, R.R.-L. and S.G.-G.; formal analysis, A.A.-O.; investigation, A.A.-O. and S.G.-G.; resources, M.V.d.l.T. and M.M.M.; data curation, A.A.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-O.; writing—review and editing, M.V.d.l.T., R.R.-L. and S.G.-G.; visualisation, A.A.-O.; supervision, R.R.-L. and S.G.-G.; project administration, S.G.-G.; funding acquisition, S.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the project Transition to sustainable agri-food sector bundling life cycle assessment and ecosystem services approaches (ALISE) (TED2021-130309B-I00), funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR, and by the project “Sustainable management of water resources in irrigated agriculture in the SUDOE area (I-ReWater-S1/2.5/E0136)”, co-funded by the programme INTERREG SUDOE. A.A.O. and S.G.G. belong to the Galician Competitive Research Group (GRC ED431C 2021/37) and to the Cross-disciplinary Research in Environmental Technologies (CRETUS Research Center, ED431G 2023/12).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations have been used in this study:

| DOCa | Qualified Designation of Origin |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas Emissions |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ES | Ecosystem Services |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| WW | Wastewater |

| TW | Treated Water |

| RW | Reclaimed Water |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| EEA | European Environmental Agency |

| EMEP | European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme |

| iLUC | Indirect Land Use Change |

| dLUC | Direct Land Use Change |

| GW | Global Warming |

| SOD | Stratospheric Ozone Depletion |

| TA | Terrestrial Acidification |

| FE | Freshwater Eutrophication |

| ME | Marine Eutrophication |

| TET | Terrestrial Ecotoxicity |

| FET | Freshwater Ecotoxicity |

| MET | Marine Ecotoxicity |

| FRS | Fossil Resource Scarcity |

| WS | Water Scarcity |

| HH | Human Health |

| R | Resources |

| E | Ecosystems |

References

- Fernández-Lobato, L.; García-Ruiz, R.; Jurado, F.; Vera, D. Life cycle assessment, C footprint and carbon balance of virgin olive oils production from traditional and intensive olive groves in southern Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elumalai, P.; Gao, X.; Parthipan, P.; Luo, J.; Cui, J. Agrochemical pollution: A serious threat to environmental health. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 43, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). Agriculture Sector Risks Briefing. 2023. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Agriculture-Sector-Risks-Briefing.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Zaragoza, C.A.; García, I.F.; García, I.M.; Poyato, E.C.; Díaz, J.A.R. Spatio-temporal analysis of nitrogen variations in an irrigation distribution network using reclaimed water for irrigating olive trees. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 262, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrouk, O.; Costa, J.M.; Francisco, R.; Lopes, C.; Chaves, M.M. Drought and water management in Mediterranean vineyards. In Grapevine in a Changing Environment: A Molecular and Ecophysiological Perspective; WILEY Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 38–67. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute. One-Quarter of World’s Crops Threatened by Water Risks. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/growing-water-risks-food-crops (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- García-Valverde, M.; Aragonés, A.M.; Andújar, J.A.S.; García, M.D.G.; Martínez-Bueno, M.J.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Long-term effects on the agroecosystem of using reclaimed water on commercial crops. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodar-Abellan, A.; López-Ortiz, M.I.; Melgarejo-Moreno, J. Wastewater treatment and water reuse in Spain. Current situation and perspectives. Water 2019, 11, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. Real Decreto 1085/2024, de 22 de Octubre, Por el que se Regula la Reutilización de Aguas Depuradas. Boletín Oficial del Estado. 2024. Available online: https://www.boe.es (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Mannina, G.; Gulhan, H.; Ni, B.J. Water reuse from wastewater treatment: The transition towards circular economy in the water sector. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Wang, S.W.; Kim, H.; Pan, S.Y.; Fan, C.; Lin, Y.J. Non-conventional water reuse in agriculture: A circular water economy. Water Res. 2021, 199, 117193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Trioli, G.; Sacchi, A.; Corbo, C.; Trevisan, M. Environmental Impact of Vinegrowing and Winemaking Inputs: An European Survey. Internet J. Vitic. Enol. 2015, 7. Available online: https://www.infowine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/libretto12728-02-1.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2024-04/OIV_STATE_OF_THE_WORLD_VINE_AND_WINE_SECTOR_IN_2023.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Regulatory Council of the DOCa Rioja. Extraordinary Performance of Rioja Exports in 2024 with a Growth of 4.42% (vs. 2023). Available online: https://riojawine.com/en-us/sin-categorizar/growth-of-rioja-exports-in-2024/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Spanish Government. Designations of Origin, Protected Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialties Guaranteed. Available online: https://administracion.gob.es/pag_Home/en/Tu-espacio-europeo/derechos-obligaciones/empresas/inicio-gestion-cierre/derechos/denominaciones-origen.html#:~:text=Products%20with%20a%20protected%20designation,which%20they%20take%20their%20name (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Canaj, K.; Morrone, D.; Roma, R.; Boari, F.; Cantore, V.; Todorovic, M. Reclaimed water for vineyard irrigation in a mediterranean context: Life cycle environmental impacts, life cycle costs, and eco-efficiency. Water 2021, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volanti, M.; Martínez, C.C.; Cespi, D.; Lopez-Baeza, E.; Vassura, I.; Passarini, F. Environmental sustainability assessment of organic vineyard practices from a life cycle perspective. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 4645–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffard, B.; Winter, S.; Guidoni, S.; Nicolai, A.; Castaldini, M.; Cluzeau, D.; Coll, P.; Cortet, J.; Le Cadre, E.; D’errico, G.; et al. Vineyard Management and Its Impacts on Soil Biodiversity, Functions, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 22, 850272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, B.G.; García, B.G.; García, J.G. Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, V.; Martínez-Paz, J.M.; Alcon, F. Sustainability assessment of agricultural practices integrating both LCA and ecosystem services approaches. Ecosyst. Serv. 2025, 72, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Crovella, T.; Paiano, A.; Falciglia, P.P.; Lagioia, G.; Ingrao, C. Wastewater recovery for sustainable agricultural systems in the circular economy—A systematic literature review of Life Cycle Assessments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalboussi, N.; Biard, Y.; Pradeleix, L.; Rapaport, A.; Sinfort, C.; Ait-Mouheb, N. Life cycle assessment as decision support tool for water reuse in agriculture irrigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rioja Government. Datos Mensuales Históricos por Estaciones. Available online: https://www.larioja.org/agricultura/es/informacion-agroclimatica/datos-mensuales-historicos-estaciones (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Microsoft. Bing Satellite [Satellite Image]. Available online: https://www.bing.com/maps (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. ISO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2006.

- Ecoinvent. Data with Purpose. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- PRé Sustainability. Simapro Database Manual; Methods Library: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). N2O Emissions From Managed Soils, and CO2 Emissions From Lime and Urea Application. In 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EMEP/EEA. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023; Technical guidance to prepare national emission inventories; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emmenegger, M.F.; Zah, R.; Reinhard, J. Sustainable Quick Check for Biofuels (SQCB): A Web-based tool for streamlined biofuels’ LCA. Environ. Inform. Ind. Environ. Prot. Concepts Methods Tools 2009, 1, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Prasuhn, V. Erfassung der PO4-Austräge für die Ökobilanzierung—SALCA-Phosphor; Agroescope Reckenholz: Zürich, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Environmental Footprint Category Rules Guidance; PEFCR Guid; European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/permalink/PEFCR_guidance_v6.3-2.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Schmidt, J.H.; Weidema, B.P.; Brandão, M. A framework for modelling indirect land use changes in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Erb, K.H.; Krausmann, F.; Gaube, V.; Bondeau, A.; Plutzar, C.; Gingrich, S.; Lucht, W.; Fischer-Kowalski, M. Quantifying and mapping the human appropriation of net primary production in earth’s terrestrial ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12942–12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Olveira, S.; Cancela, J.J.; Tubío, M.; Moreira, H.F.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Environmental benefits of ozonated water for sustainable grapevine disease control: A life cycle and carbon sequestration analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.; Steinmann, Z.J.; Elshout, P.M.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; Van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulay, A.M.; Bare, J.; Benini, L.; Berger, M.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Manzardo, A.; Margni, M.; Motoshita, M.; Núñez, M.; Pastor, A.V.; et al. The WULCA consensus characterization model for water scarcity footprints: Assessing impacts of water consumption based on available water remaining (AWARE). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 23, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Capital Project. InVEST Seasonal Water Yield Model. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/releases.naturalcapitalproject.org/invest-userguide/latest/en/seasonal_water_yield.html#rain-events (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- WorldClim. Monthly Weather Data. WorldClim—Global Climate Data. Available online: https://www.worldclim.org/data/monthlywth.html (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Natural Capital Project. Water-Related Datasets. Stanford University. Available online: https://data.naturalcapitalproject.stanford.edu/dataset/?topic=Water (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- European Environment Agency. CORINE Land Cover 2018. Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover/clc2018 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- European Space Agency. Copernicus Global Digital Elevation Model. OpenTopography. Available online: https://portal.opentopography.org/datasetMetadata?otCollectionID=OT.032021.4326.1 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Natural Capital Project. InVEST 3.10.2 Data. Available online: http://releases.naturalcapitalproject.org/?prefix=invest/3.10.2/data/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- WeatherSpark. Clima Promedio en Rioja, España Durante Todo el año. Available online: https://es.weatherspark.com/y/38194/Clima-promedio-en-Rioja-Espa%C3%B1a-durante-todo-el-a%C3%B1o#google_vignette (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- EPA. Overview of Greenhouse Gases. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Alatzas, A.; Theocharis, S.; Miliordos, D.E.; Leontaridou, K.; Kanellis, A.K.; Kotseridis, Y.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Koundouras, S. The effect of water deficit on two greek vitis vinifera l. Cultivars: Physiology, grape composition and gene expression during berry development. Plants 2021, 10, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaj, K.; Mehmeti, A.; Berbel, J. The economics of fruit and vegetable production irrigated with reclaimed water incorporating the hidden costs of life cycle environmental impacts. Resources 2021, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasuriya, B.T.G.; Ghose, A.; Gheewala, S.H.; Prapaspongsa, T. Assessment of eutrophication potential from fertiliser application in agricultural systems in Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 154993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Wang, W.; Nie, G.; Yuan, Y.; Song, X.; Yu, Z. Key biogeochemical processes and source apportionment of nitrate in the Bohai Sea based on nitrate stable isotopes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 205, 116617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agraso-Otero, A.; Cancela, J.J.; Vilanova, M.; Andreva, J.U.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; González-García, S. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Organic Wine Grape Production with Qualified Designation of Origin in La Rioja, Spain. Agriculture 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazulla, C.; Raugei, M.; Fullana-I-Palmer, P. Taking a life cycle look at crianza wine production in Spain: Where are the bottlenecks? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, A.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Novara, A.; Laudicina, V.A.; Barone, E.; Santoro, A.; Gristina, L.; Barbagallo, M.G. Cover crop and pruning residue management to reduce nitrogen mineral fertilization in mediterranean vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Martínez, A.; Sanz-Cobeña, A.; Bustamante, M.A.; Agulló, E.; Paredes, C. Effect of organic amendment addition on soil properties, greenhouse gas emissions and grape yield in semi-arid vineyard agroecosystems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J.K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Bertrand, N. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).