Assessment of Competitiveness and Complementarity in Agri-Food Trade Between the European Union and Mercosur Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Method and Data Sources

3.1. Method 1

- —exports of product k by country i;

- —total exports of country i;

- —exports of product k worldwide;

- —total world exports.

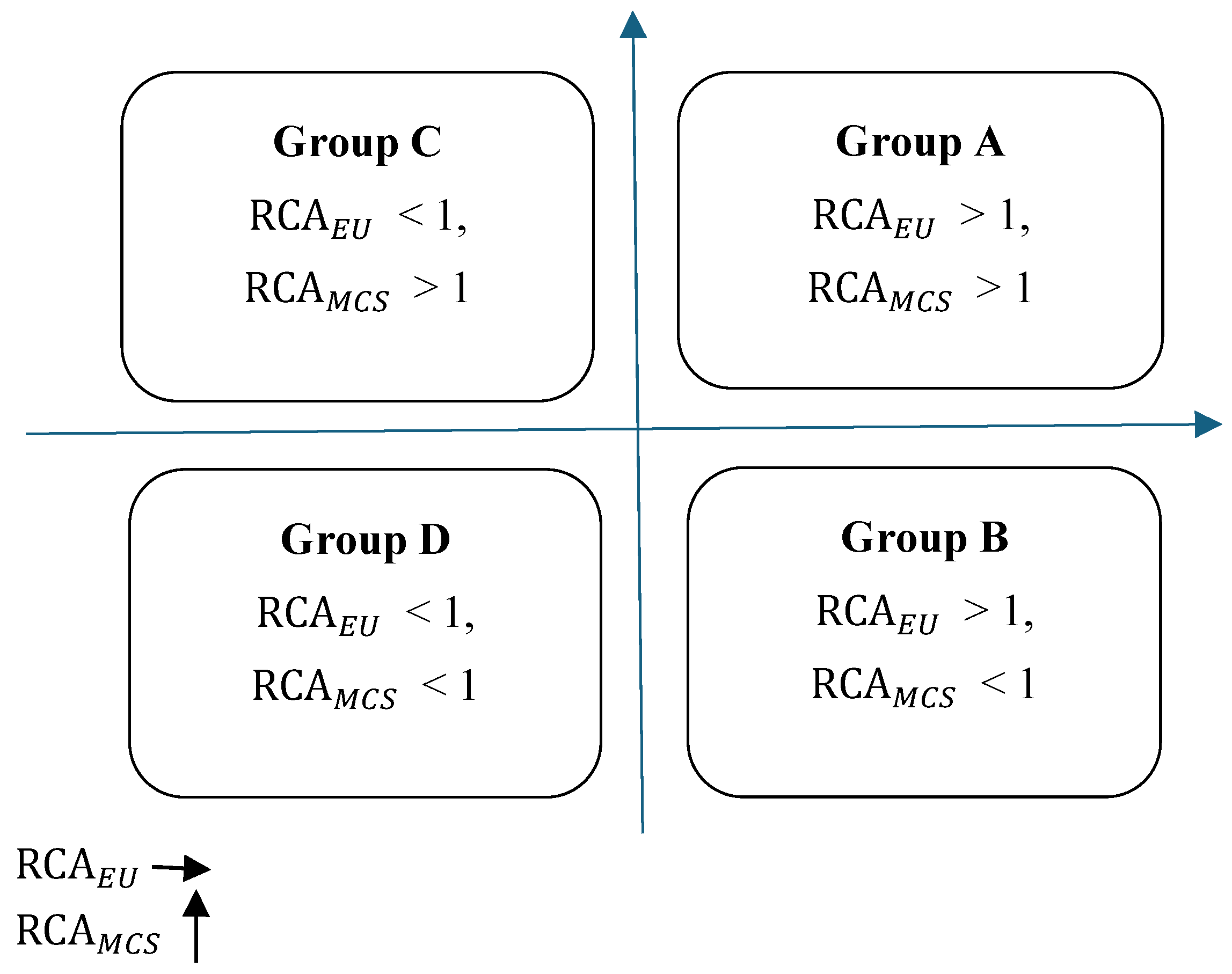

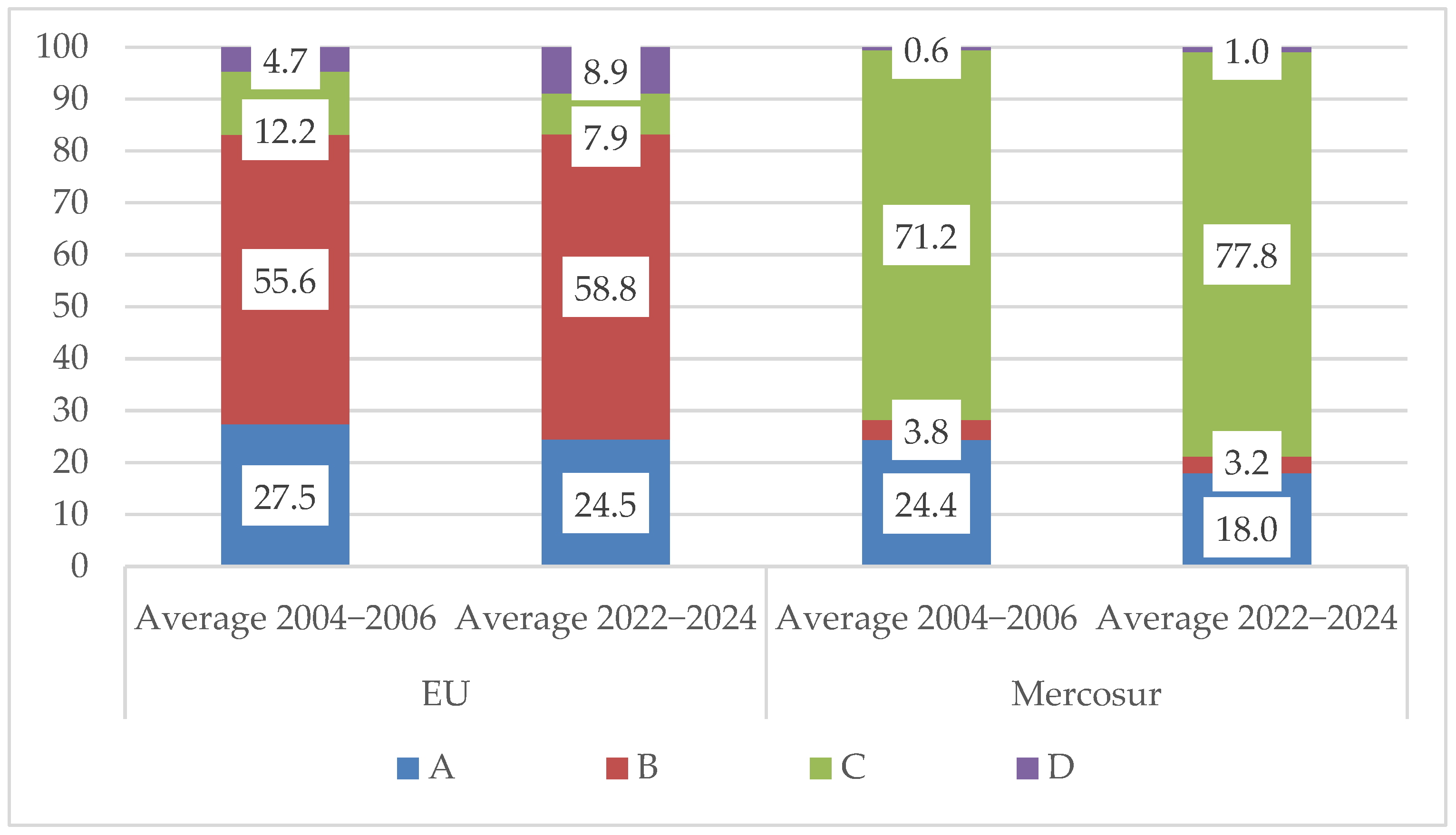

- Group A—products in which both the EU and Mercosur possess comparative advantages in export ( > 1, > 1);

- Group B—products in which the EU has advantages, but Mercosur does not ( > 1, < 1);

- Group C—products in which Mercosur has advantages, whereas the EU does not ( < 1, > 1);

- Group D—products for which neither side demonstrates comparative advantages ( < 1, < 1).

3.2. Method 2

- —index of comparative advantages in the exports of product k from country i;

- —index of comparative advantages in the imports of product k by country j;

- —imports of product k by country j;

- —total imports of country j;

- —world imports of product k;

- —total world imports.

3.3. Method 3

- —value of exports from country i to country j;

- —total export value of country I;

- —total import value of country j;

- —total value of world imports.

3.4. Method 4

- —share of product k in the total exports of country I;

- —share of product k in the total exports of country j.

- ESI = 1 indicates a complete similarity of export structures, reflecting a high level of competition in external markets (countries export the same products in similar proportions).

- ESI = 0 indicates a complete lack of similarity, i.e., complementarity of export structures, characteristic of trade based on comparative differences (export structures are entirely distinct).

4. Results

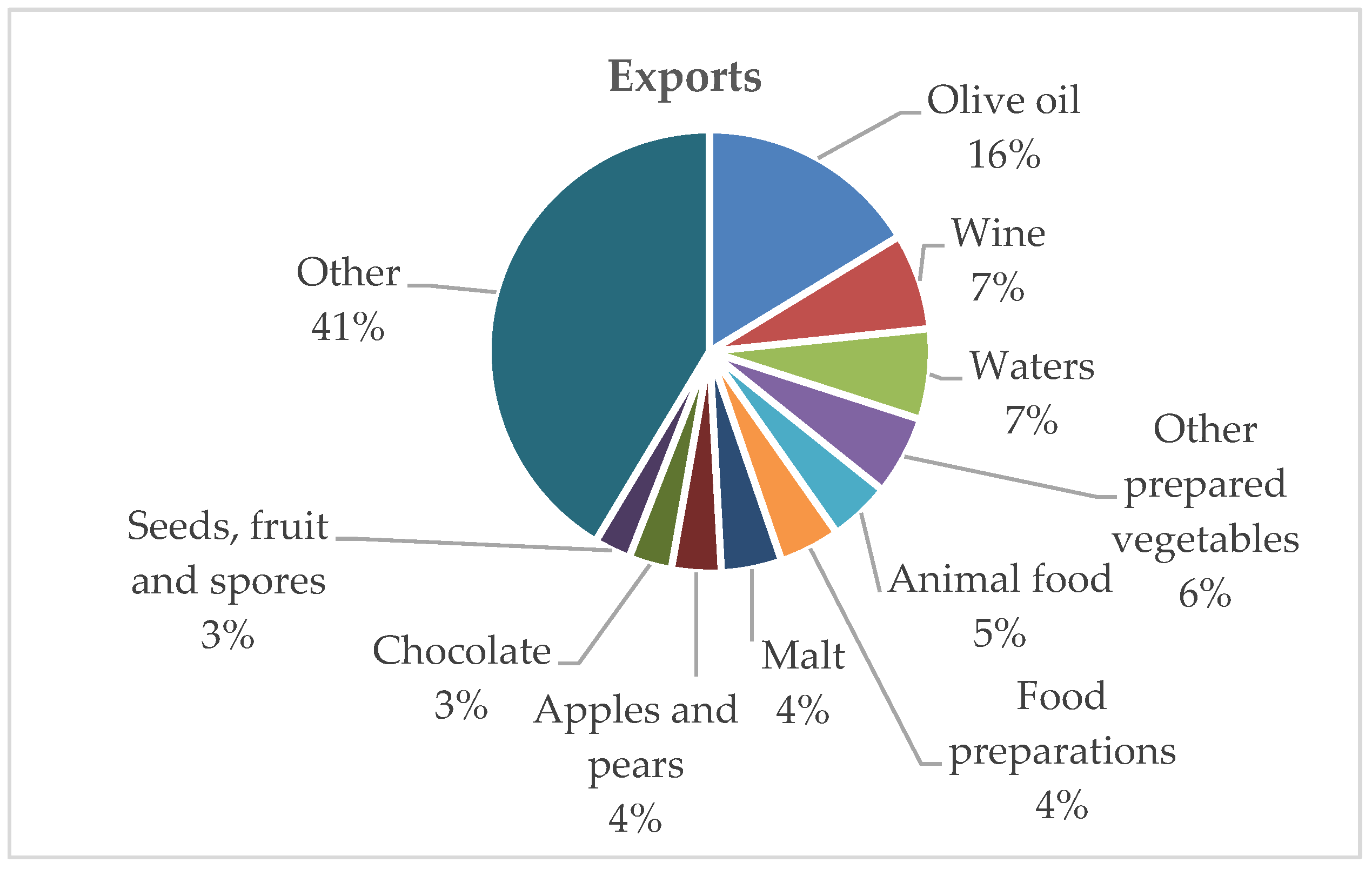

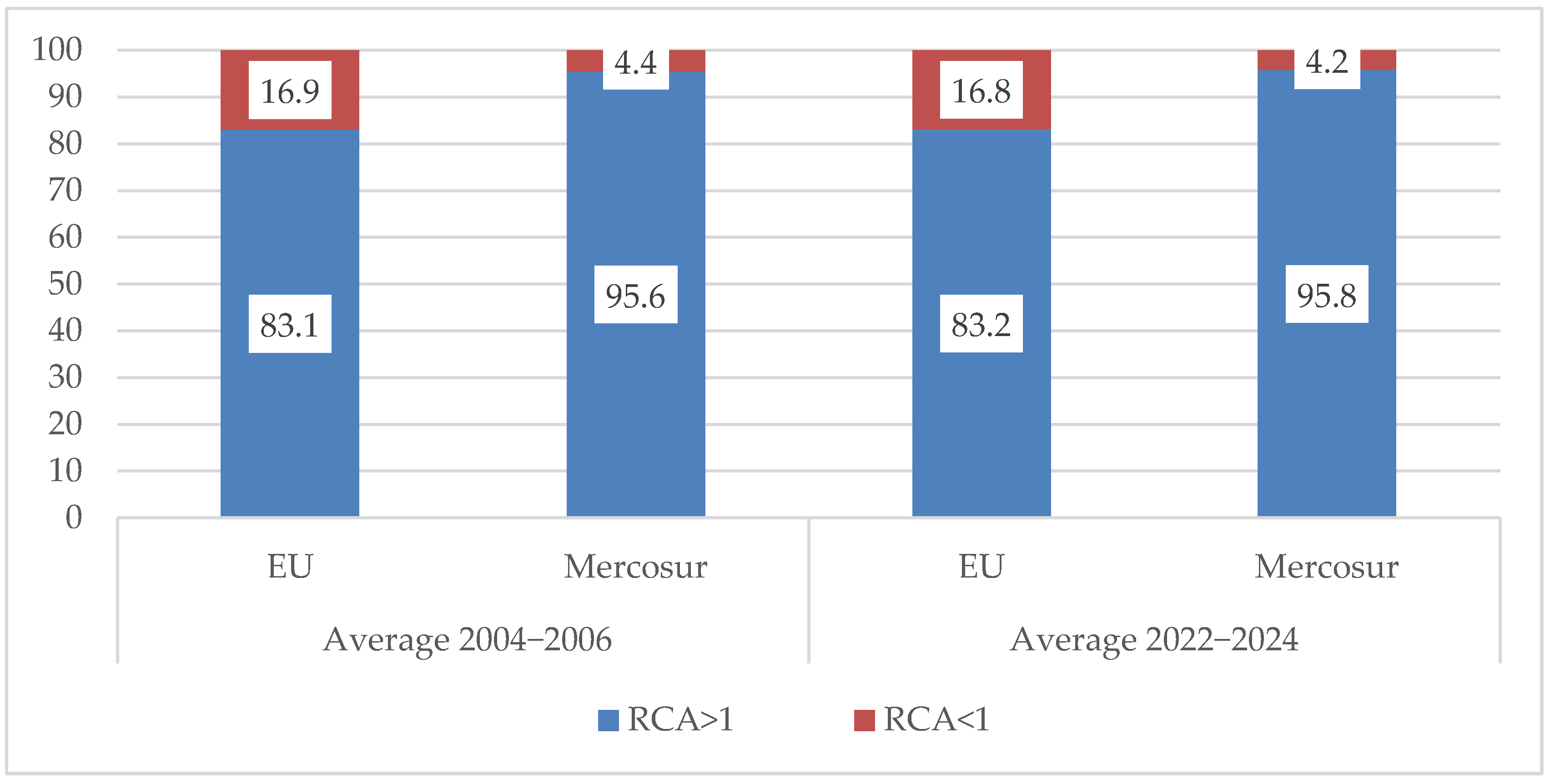

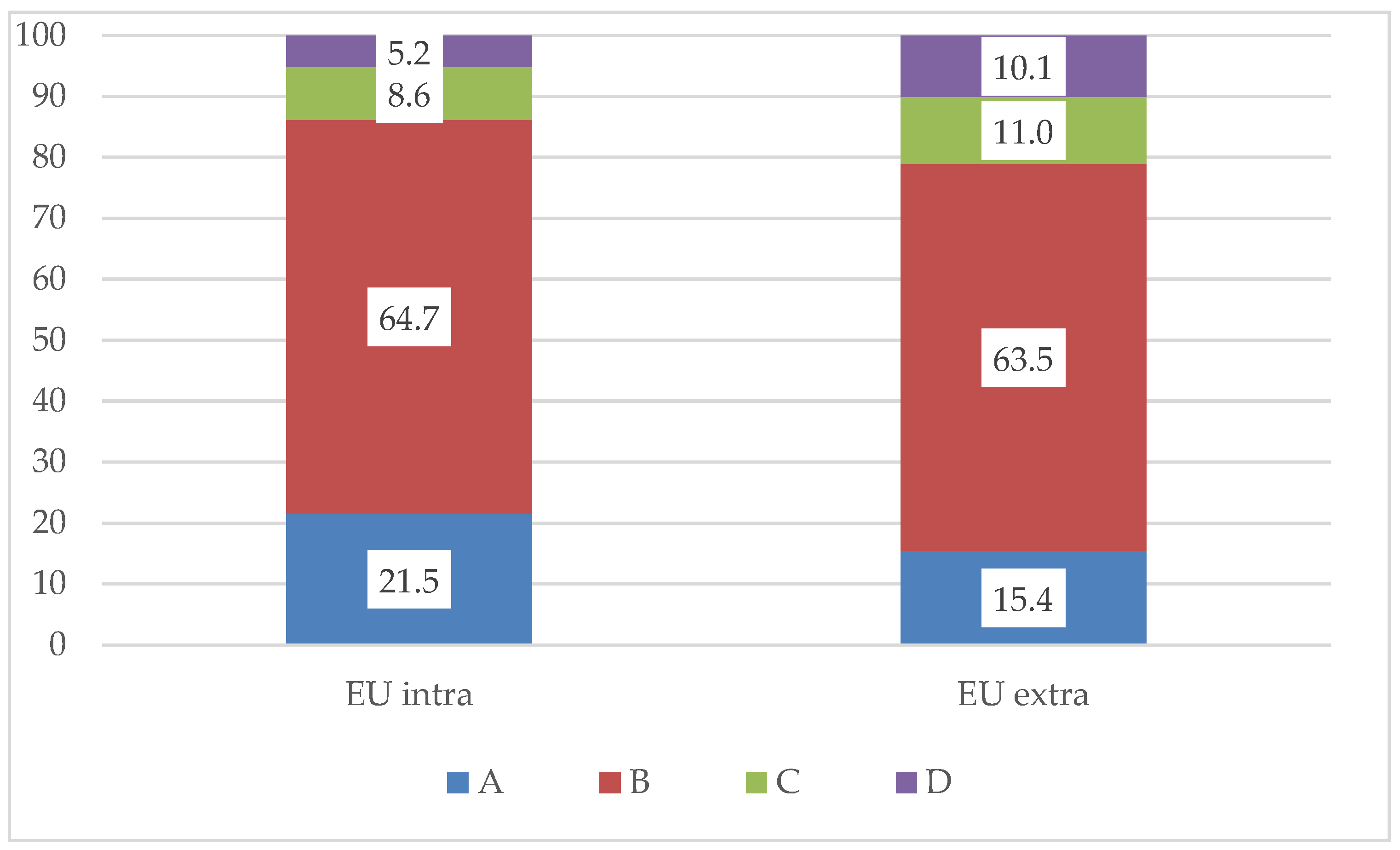

4.1. Analysis of RCA Indicators

4.2. Results of the TCI Analysis

- Soybean meal (TCI = 36.2);

- Coffee (TCI = 18.7);

- Poultry meat (TCI = 16.7);

- Sugar (TCI = 14.7);

- Maize (TCI = 13.7);

- Fruit juices (TCI = 12.8).

- Malt (TCI = 18.6);

- Olive oil (TCI = 8.6);

- Frozen vegetables (TCI = 4.1);

- Apples and pears (TCI = 3.0);

- Barley (TCI = 2.4);

- Milk powder (TCI = 2.3);

- Wine (TCI = 2.2).

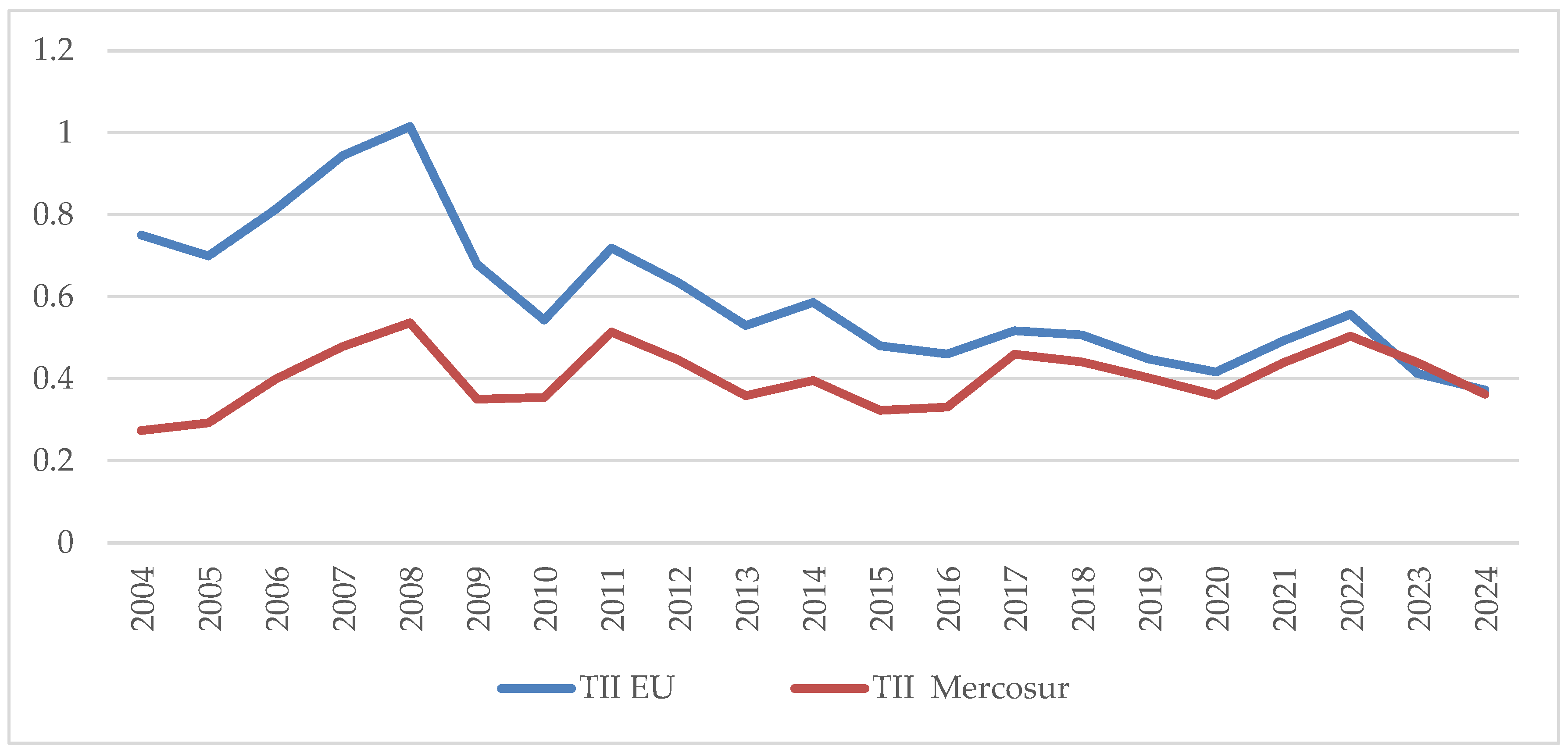

4.3. Results of the TII Analysis

4.4. Results of the ESI Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| HS4 | Name | RCA Intra-EU | RCA Extra-EU | RCA Mercosur | Share in Agri-Food Exports on Average in 2022–2024 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004– 2006 | 2022– 2024 | 2004– 2006 | 2022– 2024 | 2004– 2006 | 2022– 2024 | Intra-EU | Extra-EU | Mercosur | Intra and Extra EU | ||

| 0203 | Meat of swine | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

| 0207 | Meat of poultry | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 2.0 |

| 0201 | Meat of bovine animals, fresh or chilled | 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| 0901 | Coffee | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| 1602 | Preserved meat | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 7.9 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| 2004 | Vegetable mixes | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| 0402 | Milk powder | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 2009 | Fruit juices | 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 10.2 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| 0805 | Citrus fruit | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| 1512 | Sunflower seed oil | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 17.8 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| 2207 | Ethyl alcohol | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 22.4 | 6.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| 1601 | Sausages | 2.5 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 0102 | Bovine animals; live | 2.6 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 1003 | Barley | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| 0210 | Meat and edible meat offal | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 2101 | Extracts, essences of coffee, tea | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| 1804 | Cocoa butter | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 1517 | Margarine | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 0808 | Apples, pears and quinces | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| 0407 | Birds’ eggs | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 1107 | Malt, whether or not roasted | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 0703 | Onions, garlic | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 0105 | Poultry; live | 2.4 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 1108 | Starches | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 1805 | Cocoa; powder | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 0807 | Melons (including watermelons) | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 1101 | Wheat flour | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 0504 | Guts, bladders, and stomachs of animals | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 0511 | Animal products not elsewhere specified or included | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 2102 | Yeasts, baking powders | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 1104 | Cereal grains, ground | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 2302 | Bran, sharps | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 7.2 | 9.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 0409 | Honey, natural | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 13.9 | 7.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| HS4 | Name | TCI for Mercosur | EU Imports Average in 2022–2024 | Share of EU-Extra in EU Imports | Share of Mercosur in EU Extra Imports | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004– 2006 | 2022– 2024 | USD Thousand | % | ||||

| 0901 | Coffee | 18.5 | 18.7 | 20,978,535 | 3.0 | 60.1 | 33.1 |

| 2309 | Petfood | 0.9 | 1.2 | 19,681,713 | 2.9 | 18.2 | 0.7 |

| 0203 | Meat of swine | 4.3 | 5.5 | 14,995,716 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| 0201 | Meat of bovine animals, fresh or chilled | 10.5 | 7.5 | 12,627,322 | 1.8 | 15.3 | 53.9 |

| 2204 | Wine | 0.9 | 1.1 | 12,137,788 | 1.8 | 15.5 | 6.1 |

| 1005 | Maize (corn) | 5.5 | 13.7 | 12,034,084 | 1.7 | 47.5 | 23.0 |

| 0207 | Meat of poultry | 16.6 | 16.7 | 11,356,092 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 27.3 |

| 1001 | Wheat | 3.7 | 2.3 | 11,233,850 | 1.6 | 26.9 | 0.0 |

| 2304 | Soybean meal | 57.2 | 36.2 | 11,187,592 | 1.6 | 73.6 | 85.6 |

| 1201 | Soya beans | 20.7 | 9.7 | 8,362,465 | 1.2 | 91.0 | 46.0 |

| 1205 | Rape or colza seeds | 0.1 | 1.0 | 8,011,130 | 1.2 | 50.4 | 2.1 |

| 1602 | Preserved meat | 8.7 | 4.2 | 7,908,939 | 1.1 | 15.3 | 24.4 |

| 2009 | Fruit juices | 15.0 | 12.8 | 7,339,772 | 1.1 | 38.0 | 53.6 |

| 0805 | Citrus fruit | 4.6 | 1.9 | 7,209,653 | 1.0 | 35.2 | 12.5 |

| 1512 | Sunflower seed oil | 23.5 | 4.0 | 7,046,656 | 1.0 | 41.3 | 1.0 |

| 2207 | Ethyl alcohol | 20.7 | 10.8 | 6,763,807 | 1.0 | 24.4 | 15.2 |

| 0804 | Dates, figs, pineapples, avocados | 2.2 | 1.4 | 6,506,248 | 0.9 | 72.4 | 8.4 |

| 1701 | Sugar | 15.3 | 14.7 | 5,958,276 | 0.9 | 27.1 | 30.2 |

| 1804 | Cocoa; butter, fat, and oil | 5.3 | 2.5 | 4,918,870 | 0.7 | 36.1 | 1.2 |

| HS4 | Name | TCI for EU-27 | Mercosur Imports Average in 2022–2024 | Share of Mercosur in EU Extra Exports | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004–2006 | 2022–2024 | USD Thousand | % | |||

| 1001 | Wheat | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1,828,315 | 7.6 | 0.0 |

| 1107 | Malt, whether or not roasted | 18.3 | 18.6 | 881,700 | 3.7 | 9.4 |

| 0302 | Fish, fresh or chilled | 0.7 | 2.4 | 857,720 | 3.6 | 0.2 |

| 1509 | Olive oil | 4.2 | 8.6 | 661,162 | 2.8 | 11.6 |

| 0402 | Milk powder | 1.0 | 2.3 | 626,762 | 2.6 | 0.0 |

| 2309 | Petfood | 1.7 | 1.6 | 588,724 | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| 2204 | Wine | 1.0 | 2.2 | 565,653 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| 2004 | Frozen vegetables | 2.7 | 4.1 | 468,256 | 2.0 | 4.7 |

| 1513 | Coconut oil | 0.9 | 1.2 | 380,908 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| 0808 | Apples, pears, and quinces | 2.0 | 3.0 | 370,498 | 1.5 | 9.1 |

| 2202 | Non-alcoholic beverages | 0.6 | 1.2 | 287,026 | 1.2 | 3.9 |

| 0406 | Cheese and curd | 0.3 | 1.0 | 278,561 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| 1003 | Barley | 1.1 | 2.4 | 278,202 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| 1806 | Chocolate | 0.8 | 1.0 | 269,881 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 0703 | Onions, garlic, leeks | 3.4 | 2.1 | 254,676 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

References

- Krugman, P. Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade. J. Int. Econ. 1979, 9, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Agricultural Trade and Food Security Outlook; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Agricultural Outlook 2023–2032; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, J.M.; Borges Aguiar, G.M. Determinants of Latin American and the Caribbean Agricultural Trade: A Gravity Model Approach. Agric. Econ. Czech 2022, 68, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, P. Japan and Australia: The Prospect for Closer Economic Integration. Econ. Pap. 1969, 1, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, J.-C.; Jean, S. The Impact of the EU–Mercosur Agreement on Agricultural Trade and the Environment; OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 145; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bułkowska, M. Potencjalne skutki utworzenia strefy wolnego handlu UE–MERCOSUR dla handlu rolno-spożywczego Polski (Potential effects of the creation of the EU–Mercosur free trade area for polish agri-food trade). Stud. I Pr. Wydziału Nauk Ekon. I Zarz. Uniw. Szczec. 2018, 53, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułkowska, M. Umowa o wolnym handlu—UE–Mercosur—Szansa czy zagrożenie? (EU–Mercosur Free Trade Agreement—Opportunities or Threats?). Przem. Spoż./Food Ind. 2020, 74, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, R.; Ratnasena, S. Revealed Comparative Advantage and Half-a-Century Competitiveness of Canadian Agriculture: A Case Study of Wheat, Beef, and Pork Sectors. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 62, 519–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Godar, J.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Löfgren, P.; Gardner, T.; Vasconcelos, A.; Meyfroidt, P. The origin, supply chain, and deforestation risk of Brazil’s beef exports. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31770–31779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.L.d.C.; Pflanzer, S.B.; Rezende-de-Souza, J.H.; Chizzotti, M.L. Beef production and carcass evaluation in Brazil. Anim. Front. 2024, 14, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, A. Konkurencyjność Sektora Rolno-Spożywczego w Polsce w Kontekście Integracji Europejskiej (Competitiveness of the Agri-Food Sector in Poland in the Context of European Integration); IERiGŻ-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, K. Konkurencyjność Eksportu Produktów Rolno-Spożywczych UE na Rynkach Światowych (Competitiveness of EU Agri-Food Exports on World Markets); Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buczinski, B.; Chotteau, P.; Duflot, B.; Rosa, A. The EU-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement, Its impacts on Agriculture; Institut de l’Elevage: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Michaely, M. Trade Preferential Agreements in Latin America: An Ex-Ante Assessment; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 1583; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K.; Sapa, A. Potencjalne skutki utworzenia strefy wolnego handlu UE-MERCOSUR dla handlu rolno-żywnościowego UE. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW-Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2016, 16, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdráhal, I.; Hrabálek, M.; Becvárová, V. Assessing the agricultural trade complementarity of Mercosur and the European Union. In Agrarian Perspectives XXIX: Trends and Challenges of Agrarian Sector; Tomsik, K., Ed.; Czech University of Life Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020; pp. 418–425. Available online: https://ap.pef.czu.cz/dl/88730?lang=en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Commission. EU–Mercosur Trade Agreement: Political Agreement Summary; DG Trade: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU–Mercosur Trade Agreement: Proposal for Signature and Conclusion; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Dupré, M.; Kpenou, S. Key Insights into the Final EU–Mercosur Agreement; Veblen Institute: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.veblen-institute.org/Key-Insights-into-the-Final-EU-Mercosur-Agreement.html (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Gohin, A.; Matthews, A. The European Union–Mercosur Association Agreement: Implications for the EU Livestock Sector. J. Agric. Econ. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemejer, J.; Stoll, P.-T.; Rudloff, B.; Mensah, K. An Update on the Economic, Sustainability and Regulatory Effects of the Trade Part of the EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2025/754476/EXPO_STU%282025%29754476_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Balassa, B. Trade Liberalisation and “Revealed” Comparative Advantage. Manch. Sch. 1965, 33, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, J.M.; Kreinin, M.E. A Measure of ‘Export Similarity’ and Its Possible Uses. Econ. J. 1979, 89, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.; Piñeiro, V.; Pereda, P. Agricultural Trade and Sustainability: The EU–Mercosur Perspective; FAO Discussion Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. The WTO SPS Agreement: Texts, Cases and Practices; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemejer, J.; Maurer, A.; Rudloff, B.; Stoll, P.-T.; Woolcock, S.; Costa Vieira, A.; Mensah, K.; Sidło, K. Trade Aspects of the EU–Mercosur Association Agreement; Policy Department for External Relations, Directorate-General for External Policies, European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/653650/EXPO_STU(2021)653650_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pelikan, J.; Döbeling, T. Update: EU–Mercosur Agreement—Implications for the Agri-Food Sector; Thünen Institute of Market Analysis: Braunschweig, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/dn069863.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- European Commission. EU Agri-Food Trade Statistical Factsheet: EU27 Agri-Food Trade with Mercosur 4 (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay); Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-05/agrifood-mercosur-4_en.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Caves, R.E.; Jones, R.W.; Frankel, J.A. World Trade and Payments: An Introduction, 6th ed.; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. Scale Economies, Product Differentiation, and the Pattern of Trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 1980, 70, 950–959. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Sriboonchitta, S. Analysis on Trade Competition and Complementarity of High-Quality Agricultural Products in Countries along the Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z. Competitiveness and complementarity of agricultural products between Thailand and China on a short-term basis. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2022, 20, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Yang, F. Research on the Competitiveness and Complementarity of Agricultural Trade between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Ramasamy, S.S.; Naktnasukanjn, N.; Ying, F. Assessing competitiveness and complementarity in agricultural trade between China and Cambodia pre-pandemic and post-pandemic. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K. The Pattern of International Trade among Advanced Countries. Hitotsubashi J. Econ. 1964, 5, 16–36. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43295433 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- UNCTAD. Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Echaide, J. Environmental Impacts of the Agreement Between the European Union and Mercosur. J. Law Stud. 2022, 27, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Customs Organization. Available online: https://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/topics/nomenclature/instruments-and-tools/hs-nomenclature-2022/2022/table-of-contents_2022e_rev.pdf?la=en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Balassa, B. ‘Revealed’ Comparative Advantage Revisited: An Analysis of Relative Export Shares of the Industrial Countries, 1953–1971. Manch. Sch. 1977, 45, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WITS-Comtrade Database. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Ferrari, E.; Elleby, C.; De Jong, B.; M’barek, R.; Dominguez, I.P. Cumulative Economic Impact of Upcoming Trade Agreements on EU Agriculture: Update 2024; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, R.; Amice, C.; Amato, M.; Verneau, F. Beyond the Finish Line: Sustainability Hurdles in the EU–Mercosur Free Trade Agreement. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, S.E.M.C.; Visentin, J.C.; Pavani, B.F.; Branco, P.D.; de Maria, M.; Loyola, R. The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement as a tool for environmentally sustainable land use governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 161, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | HS Code | Commodities |

|---|---|---|

| I. Animal and animal products | 01 | Live animals |

| 02 | Meat and meat offal | |

| 03 | Fish and seafood | |

| 04 | Dairy products, eggs and honey | |

| 05 | Other products of animal origin | |

| II. Vegetable products | 06 | Live trees and other plants |

| 07 | Vegetables | |

| 08 | Fruit and nuts | |

| 09 | Coffee, tea, spices | |

| 10 | Cereals | |

| 11 | Milling products | |

| 12 | Oil seed and oleaginous fruits | |

| 13 | Vegetable saps and extracts | |

| 14 | Vegetable plaiting materials | |

| III. Fats and Oils | 15 | Animal and vegetable fats and oils |

| IV. Prepared Foodstuffs | 16 | Meat and fish preparations |

| 17 | Sugars and sugar confectionery | |

| 18 | Cocoa and cocoa preparations | |

| 19 | Cereal preparations | |

| 20 | Vegetable and fruit preparations | |

| 21 | Miscellaneous food products | |

| 22 | Alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages | |

| 23 | Waste and animal feed | |

| 24 | Tobacco and tobacco products |

| Area | Countries |

|---|---|

| European Union (EU-27) | Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Greece, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden |

| Mercado Común del Sur (Mercosur) | Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay |

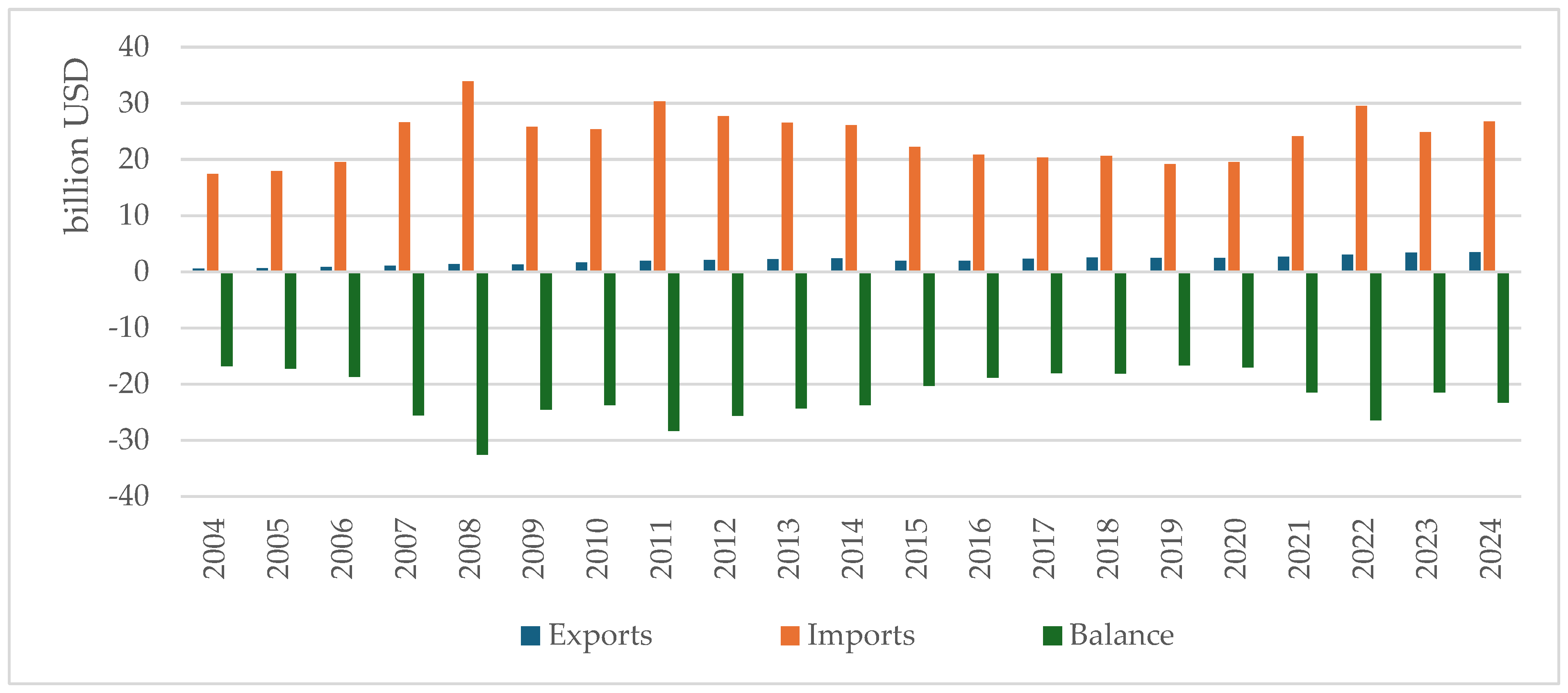

| Specification | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2004–2006 Average | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2022–2024 Average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD Million | % | USD Million | % | |||||||||

| EU-27 | Exports | World | 277,352 | 301,231 | 330,777 | 303,120 | 100.0 | 707,313 | 750,512 | 776,838 | 744,887 | 100.0 |

| Intra-EU | 187,583 | 204,730 | 222,490 | 204,934 | 67.6 | 471,637 | 509,777 | 527,433 | 502,949 | 67.5 | ||

| Extra-EU | 89,770 | 96,501 | 108,287 | 98,186 | 32.4 | 235,673 | 240,733 | 249,353 | 241,920 | 32.5 | ||

| Mercosur | 565 | 650 | 814 | 676 | 0.2 | 3014 | 3383 | 3467 | 3288 | 0.4 | ||

| Imports | World | 270,276 | 293,229 | 320,820 | 294,775 | 100.0 | 665,421 | 699,468 | 726,671 | 697,187 | 100.0 | |

| Intra-EU | 180,612 | 196,252 | 214,805 | 197,223 | 66.9 | 455,490 | 496,419 | 503,565 | 485,158 | 69.6 | ||

| Extra-EU | 89,664 | 96,977 | 106,015 | 97,552 | 33.1 | 209,930 | 203,048 | 223,104 | 212,027 | 30.4 | ||

| Mercosur | 17,411 | 17,926 | 19,510 | 18,282 | 6.2 | 29,500 | 24,896 | 26,724 | 27,040 | 3.9 | ||

| Balance | World | 7076 | 8002 | 9957 | 8345 | - | 41,892 | 51,044 | 50,166 | 47,701 | - | |

| Intra-EU | 6970 | 8478 | 7685 | 7711 | - | 16,147 | 13,358 | 23,868 | 17,791 | - | ||

| Extra-EU | 106 | −476 | 2272 | 634 | - | 25,744 | 37,685 | 26,249 | 29,892 | - | ||

| Mercosur | −16,845 | −17,276 | −18,697 | −17,606 | - | −26,486 | −21,513 | −23,256 | −23,752 | - | ||

| Mercosur | Exports | World | 46,996 | 53,318 | 60,731 | 53,682 | 100.0 | 203,555 | 196,276 | 186,735 | 195,522 | 100.0 |

| EU | 14,730 | 15,567 | 17,106 | 15,801 | 29.4 | 29,323 | 24,146 | 24,830 | 26,100 | 13.3 | ||

| RoW | 32,266 | 37,751 | 43,626 | 37,881 | 70.6 | 174,231 | 172,130 | 161,905 | 169,422 | 86.7 | ||

| Mercosur | 3056 | 3227 | 3729 | 3337 | 6.2 | 10,810 | 14,243 | 11,522 | 12,192 | 6.2 | ||

| Imports | World | 4809 | 5175 | 6330 | 5438 | 100.0 | 22,992 | 25,449 | 23,483 | 23,975 | 100.0 | |

| EU | 546 | 662 | 810 | 673 | 12.4 | 3105 | 3354 | 3307 | 3255 | 13.6 | ||

| RoW | 4263 | 4513 | 5520 | 4765 | 87.6 | 19,887 | 22,095 | 20,176 | 20,720 | 86.4 | ||

| Mercosur | 2979 | 3115 | 3799 | 3298 | 60.6 | 12,310 | 14,938 | 12,476 | 13,241 | 55.2 | ||

| Balance | World | 42,187 | 48,143 | 54,402 | 48,244 | - | 180,562 | 170,827 | 163,252 | 171,547 | - | |

| EU | 14,184 | 14,904 | 16,296 | 15,128 | - | 26,218 | 20,792 | 21,524 | 22,845 | - | ||

| RoW | 28,003 | 33,239 | 38,106 | 33,116 | - | 154,344 | 150,035 | 141,728 | 148,702 | - | ||

| Mercosur | 77 | 112 | −70 | 40 | - | −1500 | −694 | −954 | −1049 | - | ||

| HS 4 | Description | Mercosur | UE-27 (Intra and Extra) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports in mln USD (2022–2024) | |||

| 0203 | Meat of swine | 2642 | 21,524 |

| 1001 | Wheat and meslin | 3345 | 17,229 |

| 0207 | Meat and edible offal of poultry | 9172 | 14,465 |

| 0201 | Meat of bovine animals, fresh or chilled | 3086 | 13,486 |

| 1602 | Prepared or preserved meat | 1229 | 10,739 |

| 2004 | Frozen vegetables | 280 | 8626 |

| 0402 | Milk and cream, concentrated | 1030 | 8395 |

| 2009 | Fruit juices | 3087 | 6913 |

| 0805 | Citrus fruit | 369 | 6019 |

| 1512 | Sunflower oil | 990 | 5932 |

| 2207 | Ethyl alcohol | 1625 | 5392 |

| 1601 | Sausages | 210 | 5353 |

| 0102 | Live bovine animals | 616 | 4778 |

| 1003 | Barley | 949 | 4253 |

| 0210 | Meat and edible offal, salted, dried, or smoked | 459 | 4195 |

| 2101 | Extracts, essences and concentrates of coffee, tea, or maté | 820 | 4073 |

| 1804 | Cocoa butter, fat, and oil | 160 | 4065 |

| 1517 | Margarine | 189 | 4051 |

| 0808 | Apples, pears, and quinces, fresh | 301 | 3684 |

| 0206 | Edible meat offal fresh, chilled or frozen | 784 | 3668 |

| 0407 | Birds’ eggs | 129 | 3184 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bułkowska, M.; Ambroziak, Ł. Assessment of Competitiveness and Complementarity in Agri-Food Trade Between the European Union and Mercosur Countries. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232504

Bułkowska M, Ambroziak Ł. Assessment of Competitiveness and Complementarity in Agri-Food Trade Between the European Union and Mercosur Countries. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232504

Chicago/Turabian StyleBułkowska, Małgorzata, and Łukasz Ambroziak. 2025. "Assessment of Competitiveness and Complementarity in Agri-Food Trade Between the European Union and Mercosur Countries" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232504

APA StyleBułkowska, M., & Ambroziak, Ł. (2025). Assessment of Competitiveness and Complementarity in Agri-Food Trade Between the European Union and Mercosur Countries. Agriculture, 15(23), 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232504