Abstract

The dynamic response of soil bacterial communities to fertilization throughout the entire crop growth cycle remains inadequately characterized. To address this, we conducted a long-term field experiment in Jiangle County, Fujian Province, China, and collected soil samples across four rice growth stages (tillering, elongation, filling and maturity) under five fertilization regimes: no fertilization (CK); chemical fertilizer (NPK); and NPK supplemented with extra nitrogen (NPKN), extra phosphorus (NPKP) and rice straw (NPKS). Bacterial communities were analyzed by high-throughput sequencing. Our results revealed that soil bacterial diversity decreased progressively throughout the growth stages, with fertilization exerting only a minor influence. Structural equation modeling (SEM) identified daily mean temperature (DMT) as the factor with the strongest direct and total effects on the diversity. In contrast, fertilization regimes were the primary determinant of the community structure. Mantel test and redundancy analysis (RDA) indicated that soil pH was the most important factor shaping the community structure. Soil bacterial network attributes also varied mainly with fertilization: fertilizer addition reduced the complexity but enhanced stability, with NPK and NPKS showing the greatest stability. Regarding rice yields, all fertilized treatments were comparable but considerably higher than CK. In conclusion, rice growth stages primarily influenced soil bacterial diversity, while fertilization regimes predominantly shaped the community structure and network attributes. Further, we recommend NPK and NPKS as optimal strategies for balancing crop production, agroecosystem sustainability and environmental health.

1. Introduction

Rice, as a staple food for nearly half of the global population, is critical to shaping food production patterns and ensuring food security worldwide [1]. To meet rising demand under growing population pressure, mineral fertilizers have been extensively used to boost grain yield [2]. For instance, while China’s total grain output has tripled over the past half-century, nitrogen (N) fertilizer inputs have surged nearly 37-fold [3]. However, the overuse of chemical fertilizers, especially in paddy systems, has triggered soil acidification, water eutrophication, air pollution, and declining land productivity, thereby undermining agricultural sustainability [4,5]. In response, improved agricultural management practices have been implemented, such as soil testing and formulated fertilization, addition of controlled-release fertilizers, deep placement of fertilizers and incorporation of organic fertilizers [6].

Soil microorganisms are essential to ecosystem functions and soil quality, regulating nutrient cycling, bioremediation and plant growth [7]. Among them, bacteria represent the most abundant, diverse, and metabolically active group, and respond rapidly to agricultural management [8]. Dai et al. [9] found that N fertilization alone significantly decreased soil bacterial diversity, while combined NPK fertilization increased it in agroecosystems. Compared to mineral-only fertilization, organic amendments, including straw, plant residue, and manure, increased soil bacterial diversity in both paddy and upland-paddy fields and shifted the community structure [10]. These changes in soil bacterial communities were closely linked to variations in soil properties, particularly soil pH and organic carbon. However, Chen et al. [11] reported that organic amendments reduced bacterial diversity in water-dry rotation soils, and temperature might outweigh soil properties in driving diversity patterns. Moreover, some studies reported no significant effects of inorganic fertilizers or straw return on soil bacterial diversity or community structure in paddy fields [12,13,14]. These inconsistencies highlight the context-dependent nature of soil bacterial responses, which are likely influenced by differences in soil properties, fertilization rates, and water management [15].

Beyond fertilization, crop growth stages also influence soil microbial communities [16,17]. Temporal shifts in soil microbes are generally caused by stage-related changes in temperature, moisture, soil nutrient availability and root exudation [18,19]. In wheat and rice systems, growth stage has been identified as a stronger predictor of soil bacterial abundance and community structure than fertilization [12,20]. Long-term straw return significantly altered soil bacterial community structure across rice growth stages, reducing diversity at early tillering but increasing it at the panicle initiation and heading stages [8]. Given this temporal variability, it is imperative to track bacterial community dynamics across the growing season to accurately assess fertilization effects. However, most existing studies rely on single time-point sampling, offering only a snapshot of potential bacterial community responses. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of how bacterial communities evolve under different fertilization practices over time remains limited for paddy soils.

Soil microorganisms do not exist in isolation but form complex ecological networks through material, energy and information exchange [21,22]. These interacting clusters are expected to play essential roles in nutrient cycling, soil structure improvement, disease suppression and plant health regulation [23]. Emerging evidence suggests that the complexity and stability of soil microbial network underpin ecosystem multifunctionality. For instance, reduced rainfall diminished soil multifunctionality in semiarid grassland by lowering microbial network complexity [24]. Intensive soil management decreased the stability of soil biota networks, which in turn predicted declines in soil multifunctionality [2]. Similarly, carbon loss in permafrost was linked to declining microbial network stability in the active layer [25]. Despite these insights, little is known about how rice growth stages and fertilization regimes affect the complexity and stability of soil bacterial networks.

In this study, we sampled soils from a long-term field fertilization experiment across four rice growth stages (tillering, elongation, filling and maturity) under five fertilization regimes: no fertilization, chemical fertilizer at the locally recommended rate, and 50% extra N, 50% extra phosphorus (P) and straw return combined with the recommended rate. Soil bacterial communities were characterized by high-throughput sequencing. Our objectives were to (1) assess the influence of rice growth stages on soil bacterial diversity and community structure under different fertilization treatments; (2) track the dynamic response of soil bacterial communities to fertilization treatments across rice growth stages; and (3) evaluate the effects of rice growth stages and fertilization treatments on the complexity and stability of soil bacterial networks. Understanding how bacterial communities change over the growing season under different fertilization practices will provide valuable insights for optimizing agricultural management and enhancing sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

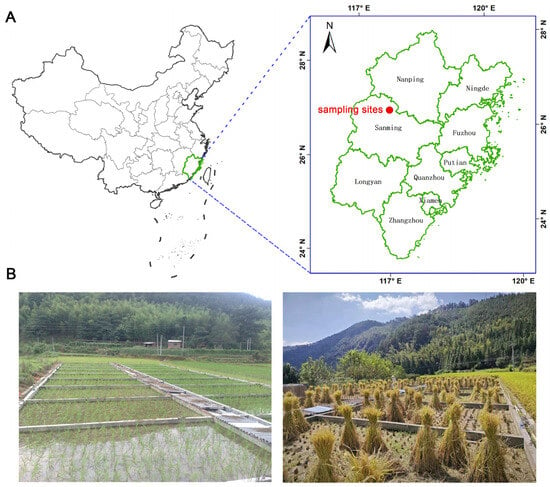

The long-term field experiment was established in 2008 in Jiangle County, Sanming City, Fujian Province, China (26.748° N, 117.113° E) (Figure 1). The site is located in the subtropical region, with a mean annual temperature of 19 °C and mean annual precipitation of 1670 mm. The soil was classified as an Anthrosol according to the WRB soil classification system and originated from granite bedrock. The cropping system follows a tobacco-rice rotation, a common paddy-upland system in the subtropical regions of China. The rice variety is Huifengyou3518, cultivated from June to October. During the rice growing season, a water layer of approximately 5 cm was maintained above the soil surface. The soil is predominantly composed of silt and clay, resulting in a loam texture.

Figure 1.

The sampling sites in Jiangle County, Sanming City, Fujian Province, China (A). Growth and harvest of rice during the trial period (B).

The experiment included five fertilization treatments: no fertilization (CK); N, P, and K fertilizers applied at the locally recommended rate based on soil testing and formulated fertilization (NPK); NPK with 50% extra N (NPKN); NPK with 50% extra P (NPKP); and NPK combined with straw return (NPKS). Rice straw was chopped and incorporated into the soil by plowing at a rate of 3600 kg ha−1. N was supplied as ammonium bicarbonate and urea each year. Treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replicates. Each plot (7 m × 4 m) was separated by brick frames. Detailed fertilizer application rates during rice growing season are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Annual fertilizer application rates in the long-term field experiment in paddy fields from 2008 to 2024.

2.2. Soil Sampling

Bulk soil samples were collected during the 2024 rice growing season at four key growth stages: tillering (1 August), elongation (23 August), filling (13 September) and maturity (10 October). Sampling occurred at least two weeks after any fertilizer application. In each plot, five topsoil cores (0–20 cm depth) were collected from the plow layer using a soil auger and combined into one composite sample. This procedure yielded a total of 60 samples (5 treatments × 3 replicates × 4 stages). All samples were immediately placed in an ice box for transport to the laboratory. Upon arrival, each composite sample was processed as follows: one portion was stored at 4 °C for measurement of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and soil water content (SWC); another was stored at −80 °C for molecular analysis of soil bacterial community; and the remaining soil was air-dried and sieved for analysis of standard soil physicochemical properties.

2.3. Acquisition of Soil Properties

SWC was determined by drying fresh soil at 105 °C for 48 h. Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 soil/water suspension using a glass electrode meter. Soil organic matter (SOM) was analyzed by the wet digestion method with K2Cr2O7-H2SO4, and total nitrogen (TN) was determined by the semi-micro Kjeldahl method [26]. Exchangeable NH4+-N and NO3−-N were extracted with 2 mol/L KCl, shaking at 250 rpm for 60 min at 25 °C on a mechanical shaker. After the extract was filtered, their concentrations were quantified using a segmented-continuous flow analyzer (Skalar, Breda, The Netherlands) [27]. Available phosphorus (AP) was extracted with sodium bicarbonate and measured by the molybdenum blue method [28]. DOC was extracted with 0.5 mol/L K2SO4 and analyzed by an organic carbon-nitrogen analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.4. Analysis of Soil Bacterial Community

Soil DNA was extracted using the Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer was used to evaluate DNA quality and quantity (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The V4-V5 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 907R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′). To monitor potential contamination, a negative control (using nuclease-free water as template) was included during the PCR amplification process. PCR amplification was performed in a 50 μL reaction mixture with the following procedure: 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s), and 72 °C for 10 min. For each sample, three independent PCR amplifications were performed and the resulting products were pooled. PCR products were separated into 1.5% agarose gels and subsequently extracted from the gels. The mixture of PCR products was purified using the E.Z.N.A. Gel Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Lastly, the purified products were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Raw sequences were processed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME, version 2020.11.0) [29]. The DADA2 plugin (version 1.8) was used to identify ASVs by clustering or de-duplication with a 100% similarity threshold [30]. A total of 124,802 ASVs were acquired, each of which was matched to SILVA 138 for its taxonomy. Samples of soil bacteria were rarefied to 42,822 sequences based on the minimum sequencing number.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the impact of fertilization treatments, rice growth stages, and their interactions. One-way ANOVA was performed to compare the differences among fertilization treatments and growth stages. The Bonferroni test (α = 0.05) was used to conduct post hoc multiple comparisons using the “agricolae” package in R (version 4.3.3). The overall distribution of soil properties across samples was visualized by principal component analysis (PCA). Rarefaction curves of ASVs were generated to evaluate sequencing depth coverage. Unique and shared ASVs among different groups were shown in UpSet plots implemented with the “UpSetR” package [31]. SEM was constructed using the robust maximum likelihood evaluation method in AMOS 28.0. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed based on Bray–Curtis distances to show the distribution of soil bacterial communities. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to test the significant effect of growth stages, fertilization, and their interactions on the community structure. Relationships between the community structure and environmental variables were calculated by Mantel test and RDA. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was conducted using LEfSe to identify biomarkers at multiple taxonomic levels (p < 0.05, LDA score > 3.0). The PCA, PCoA, PERMANOVA, RDA, and Mantel tests were conducted using the “vegan” package in R.

Soil bacterial networks were constructed following the approach of Xu et al. [32], including only ASVs with a relative abundance > 0.01%. Random matrix theory (RMT) was utilized to identify an appropriate correlation threshold [33]. The complexity and stability of soil bacterial network were calculated as described by Long et al. [2] Simply, the average variation degree (AVD) reflects the overall stability of a community by calculating the variation between the abundance of each species [34]. Higher AVD values indicated greater variability and fluctuations in bacterial network. Therefore, 1/AVD was used to represent the stability in this study. The topological features of the networks were calculated to evaluate the network complexity, including average degree, average clustering coefficient, average path length, network diameter, graph density, and modularity. We computed one index to reflect the complexity by averaging the standardized scores (a common scale ranging from 0 to 1) of the topological features.

3. Results

3.1. Rice Yield and Soil Physicochemical Properties

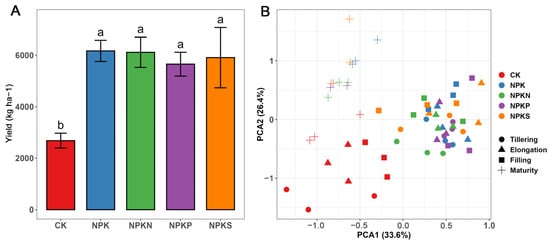

Compared to the CK treatment, chemical fertilizer application significantly increased rice yield by 210–230%; however, no significant differences were observed among treatments with fertilizer application (Figure 2A). The NPK treatment was designed based on soil testing and formulated fertilization, as well as long-term production experience in the study region. These results implied that moderate fertilization could enhance crop yields, whereas excessive fertilizer input does not provide additional yield benefits and may even lead to yield plateaus.

Figure 2.

Rice yields and soil physicochemical properties. Rice yields under different fertilization treatments (A). Different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences among fertilization treatments (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni test). PCA plots of soil properties among rice growth stages and among fertilization treatments (B).

According to two-way ANOVA, all measured soil properties varied significantly across rice growth stages, whereas fewer were significantly affected by fertilization practices (Table 2, Table S1). Significant interactions between the growth stages and fertilization were detected only for a minority of properties, such as pH, NO3− and AP. The maturity stage was characterized by the highest SOM and the lowest pH, NH4+, AP and SWC. Paddy soils from the tillering stage contained the lowest TN, while the soils from the filling stage showed the lowest C/N and NO3−. DOC consistently decreased from the tillering, elongation, filling to maturity stages. Fertilization treatments did not significantly affect C/N, NH4+ and DOC. However, CK exhibited the highest pH and NO3− levels, and fertilizer application increased SOM, TN, AP and SWC. PCA of soil properties clearly distinguished maturity stage soils from other stages and separated CK from fertilized treatments (Figure 2B). Together, these results demonstrated that both fertilization regimes and rice growth stages shaped distinct soil conditions in this study.

Table 2.

The effects of rice growth stages, fertilization treatments and their interactions on soil properties by two-way ANOVA.

3.2. Soil Bacterial Community Composition

All samples were rarefied to 42,822 sequences. The rarefaction curves approached a plateau at this sequencing depth, confirming that the data sufficiently captured the majority of soil bacteria (Figure S1). A total of 124,802 ASVs were identified across all sequences, and the distribution of these ASVs among the different groups was visualized using UpSet plots. From the tillering to maturity stages, paddy soils contained a progressively decreasing number of ASVs, and the number of unique ASVs at different stages followed a similar declining trend (Figure S2A). In comparison, the number of ASVs shared among the growth stages was low. For example, only 3522 ASVs (2.8%) were shared among all four growth stages. Likewise, the number of unique ASVs in each fertilization treatment substantially exceeded the number shared among the treatments (Figure S2B). The total number of ASVs per treatment followed the order: NPKP > NPK > NPKN > NPKS > CK.

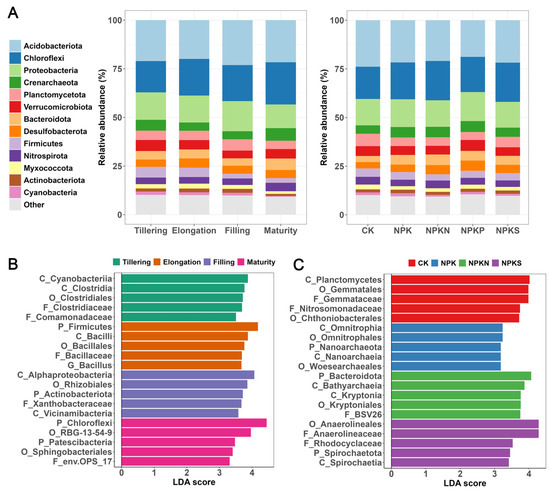

All sequences were classified into 71 phyla. The dominant phyla with a relative abundance > 1% included Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, Crenarchaeota, Planctomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota, Bacteroidota, Desulfobacterota, Firmicutes, Nitrospirota, Myxococcota, Actinobacteriota and Cyanobacteria (Figure 3A). These phyla were consistently detected in all samples, with cumulative relative abundances ranging from 86.5% to 92.7%. The LEfSe method was employed to identify differentially abundant bacterial taxa from phylum to genus level, revealing 123 and 120 biomarkers for rice growth stages and fertilization treatments, respectively. The top five biomarkers based on LDA score for each stage and treatment are listed in Table S2. The phylum Firmicutes, along with the classes Bacilli, Alphaproteobacteria and Anaerolineae, were the most discriminative biomarkers for the tillering, elongation, filling and maturity stages, respectively (Figure 3B). For fertilization treatments, the classes Planctomycetes and Omnitrophia, phylum Bacteroidota, genus Sideroxydans and order Anaerolineales were the predominant biomarkers in CK, NPK, NPKN, NPKP and NPKS, respectively (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Comparison of soil bacterial taxa among rice growth stages and fertilization treatments. The phyla with the relative abundance > 1% among different growth stages and fertilization treatments (A). Biomarkers at each rice growth stage (B) and in each fertilization treatment (C) including phylum (P_), class (C_), order (O_), family (F_), and genus (G_) taxonomic levels. The top 5 biomarkers for LDA scores in each stage and treatment are listed.

3.3. Soil Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure

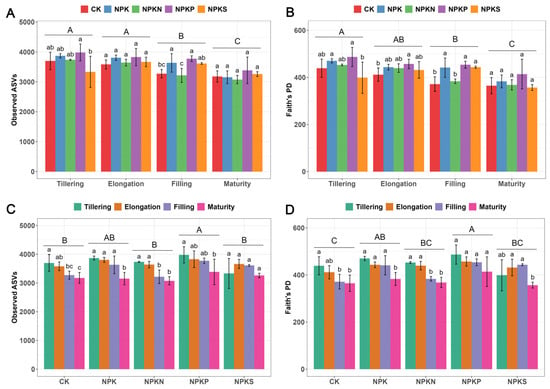

Two-way ANOVA indicated that rice growth stages and fertilization treatments significantly influenced soil bacterial diversity, as measured by observed ASVs and Faith’s PD, though their interactions were not significant (Table 3). Both diversity indices of all soils decreased progressively across rice growth stages, with significant differences observed among the tillering, filling and maturity stages (Figure 4A,B). A similar temporal trend was observed in the CK, NPK, NPKN and NPKP treatments (Figure 4C,D). Compared to CK, only NPKP significantly increased observed ASVs (Figure 4C), whereas both NPKP and NPK elevated Faith’s PD across all samples (Figure 4D). These fertilization effects remained consistent at each individual growth stage (Figure 4A,B). Overall, rice growth stages had a stronger influence on soil bacterial diversity than fertilization treatments in this study.

Table 3.

The effects of rice growth stages, fertilization treatments and their interactions on soil bacterial diversity by two-way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

Observed ASVs among different growth stages (A) and fertilization treatments (C). Faith’s PD among different growth stages (B) and fertilization treatments (D). Different uppercase letters and different lowercase letters above bars indicate significant differences.

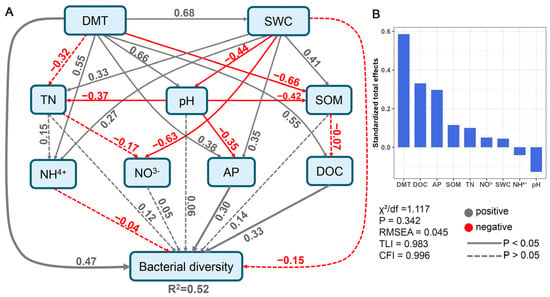

SEM quantified the direct and indirect effects of environmental variables on soil bacterial diversity, explaining 52% of the total variance (Figure 5A). DMT, DOC and AP had direct positive effects on the diversity, with standardized path coefficients of 0.47, 0.33 and 0.30, respectively. In addition, DMT, SWC and soil pH indirectly influenced the diversity through AP, while DMT also exerted an indirect effect via DOC. DMT exhibited the highest total standardized effect on the diversity, followed by DOC and AP (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Structural equation model (SEM) used to assess multivariate effects on the soil bacterial diversity (A). Solid and dash lines indicate the significant and non-significant pathways, and gray and red lines indicate the positive and negative correlations, respectively. The numbers are the standardized path coefficient. Standardized total effects of environment factors on soil bacterial diversity as revealed from the SEM (B).

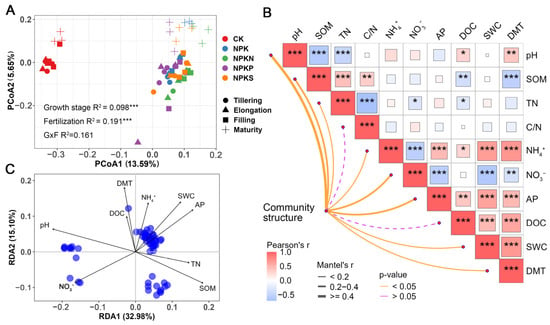

In the PCoA plot, bacterial communities in the CK treatment were clearly separated from those under fertilized regimes (Figure 6A). PERMANOVA confirmed that both rice growth stages (R2 = 0.098, p < 0.001) and fertilization treatments (R2 = 0.191, p < 0.001) significantly influenced the community structure, with no significant interaction observed. Fertilization exerted a stronger influence than the growth stages. Both Mantel tests and RDA identified soil pH as the strongest predictor of the community structure, followed by SOM, NO3−, AP and SWC (Figure 6B,C).

Figure 6.

Soil bacterial community structure and its influencing factors. The PCoA ordinations show soil bacterial communities among rice growth stages and fertilization treatments (A). Mantel test of soil bacterial community structure based on Bray–Curtis distances (B). Redundancy analysis (RDA) of soil bacterial community structure for all samples (C). Asterisks represent significance of correlation (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

3.4. Soil Bacterial Network Complexity and Stability

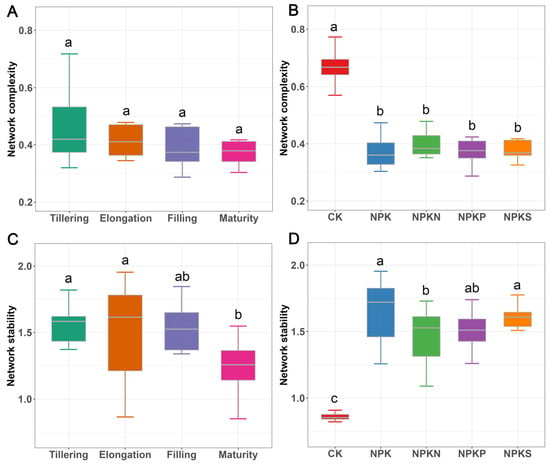

RMT was applied to determine the correlation threshold for constructing soil bacterial networks, yielding an optimal cutoff of 0.656 (Figure S3). The complexity and stability of soil bacterial network were subsequently quantified. Two-way ANOVA identified that the complexity was significantly influenced only by fertilization, whereas the stability was affected by both fertilization and rice growth stages, and no significant interactions between the two factors were observed (Table 4). The complexity remained stable across the growth stages (Figure 7A) but was significantly higher in CK than in fertilized treatments (Figure 7B). In contrast, the stability was lowest in CK, with NPK and NPKS showing the highest stability, followed by NPKP and NPKN (Figure 7D). Among different growth stages, the stability was significantly higher at the tillering and elongation stages than at the maturity stage (Figure 7C). Overall, fertilization had a stronger effect than the growth stages on both the complexity and stability.

Table 4.

The effects of rice growth stages, fertilization treatments and their interactions on the complexity and stability of soil bacterial network by two-way ANOVA.

Figure 7.

Soil bacterial network complexity among different growth stages (A) and fertilization treatments (B). The stability among different growth stages (C) and fertilization treatments (D). The differences in the complexity and stability are identified by the Bonferroni test. Different lowercase letters above boxes indicate significant differences.

We further evaluated the correlations between soil bacterial network attributes and the relative abundance of dominant phyla (Table 5). The complexity correlated positively with Acidobacteriota and Planctomycetota but negatively with Bacteroidota and Desulfobacterota. In contrast, the stability was positively associated with Actinobacteriota and negatively associated with Planctomycetota.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficients between soil bacterial network complexity and stability and the phyla with the relative abundance > 1%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Rice Growth Stages Outweigh Fertilization for Soil Bacterial Diversity

In the present study, soil bacterial diversity progressively declined from rice tillering to maturity stages (Figure 4A,B). Among fertilization treatments, NPKP supported the highest diversity, followed by NPK and other treatments (Figure 4C,D). Overall, rice growth stages outweighed fertilization for influencing the diversity (Table 3). Consistent with our findings, Wu et al. [13] reported that fertilization exerted only a minor effect on the bacterial diversity for a 17-year fertilization experiment in paddy soils, suggesting that long-term fertilization might diminish the responsiveness of soil bacterial diversity to nutrient amendments. Similarly, other studies have observed that rice growth stages influence soil microbial diversity more strongly than cropping practices [16,17].

Temporal shifts in microbial communities during plant growth are influenced by factors such as temperature, moisture, soil nutrient status and root exudates. Although root exudates such as organic acids and amino acids were not quantified in this study, previous work indicated their concentrations were generally low in bulk soil [12,35]. To elucidate the direct and indirect effects of multiple environmental variables, we performed SEM (Figure 5). The model showed that DMT had the strongest direct and total effect on the diversity, underscoring the critical role of temperature in shaping soil bacterial communities. Temperature is widely recognized as a key driver of soil microbial diversity [36,37]. The most important direct mechanism is that elevated temperatures accelerate microbial metabolism, growth and population turnover [38]. Second, higher temperatures can enhance plant productivity, thereby supporting greater microbial species richness [39]. Additionally, temperature also indirectly influenced microbial diversity through interactions with soil nutrient availability, such as DOC and AP in this study (Figure 5A).

DOC emerged as the second most important factor affecting the diversity, likely due to its rapid turnover and high bioavailability to soil microbes [40,41]. Notably, the temporal trend in soil bacterial diversity during the rice growth period paralleled that of DOC in this study. Whereas a global meta-analysis suggested that soil microbial diversity decreased with DOC, in which the N application reduced soil pH, and low pH increased the mortality of soil microorganisms and plant roots, further contributing to the release of DOC [42]. This phenomenon was more prevalent in alkaline soils, and soil pH was often negatively correlated with DOC. In contrast, the soils in our study were acidic, and soil pH showed a positive correlation with DOC (Figure 6B). SEM also indicated that AP significantly influenced diversity, which aligns with our observation that NPKP, the treatment with the highest AP levels, supported the greatest diversity among all fertilization regimes (Figure 4C,D). In support of this, Li et al. [17] emphasized the important role of P input levels in regulating soil microbial diversity.

4.2. Fertilization Has a Greater Effect on Soil Bacterial Community Structure

Although both rice growth stages and fertilization treatments significantly altered soil bacterial community structure, the differences were more pronounced among fertilization treatments than among growth stages (Figure 6A), indicating that fertilization regimes exerted a stronger influence. Soil pH was identified as the strongest predictor of community structure (Figure 6B,C). This is consistent with the observed reduction in soil pH under chemical fertilizer application, while pH variation across growth stages remained relatively minor (Table 2 and Table S1). This likely explains why fertilization had such a pronounced effect on the community structure [43]. The acidifying effect of chemical fertilizers on soil pH, combined with the established role of pH in structuring soil microbial communities, is well documented [44]. While soil pH had only a minor impact on soil bacterial diversity, it strongly influenced community structure, suggesting that pH acts not merely as a broad filter on taxonomic richness, but likely governs community assembly by modulating the relative abundance of specific bacterial taxa.

Soils in CK, NPK, NPKN, NPKP and NPKS stimulated Planctomycetes, Omnitrophia, Bacteroidota, Sideroxydans and Anaerolineales, respectively (Figure 3B, Table S2). These findings align with Zhang et al. [45], who reported that N application shifted soil bacterial community composition in degraded grasslands, and some oligotrophic taxa, such as Planctomycetes adapted to the barren environments, were excluded by copiotrophic taxa, such as Bacteroidota growing faster under nitrogen-enriched conditions. Anaerolineales, which are primarily involved in organic matter degradation [46], increased in abundance under straw addition (NPKS), reflecting their role in carbon cycling. The iron-oxidizing bacterium Sideroxydans was enriched in NPKP, likely due to enhanced iron-phosphorus coupling processes in paddy soils under high phosphorus input [47]. Although Omnitrophia remains poorly characterized, it belongs to the Verrucomicrobiota phylum, which is common in paddy soils [48]; its increase under NPK may reflect adaptation to moderately acidic conditions.

4.3. Fertilizer Addition Reduces the Complexity but Increases the Stability of Network

Similarly to soil bacterial community structure, both the complexity and stability of soil bacterial network were more strongly influenced by fertilization regimes than by rice growth stages (Table 4, Figure 7). Fertilizer application significantly reduced the complexity compared to the CK treatment, a pattern consistent with previous reports of simplified soil microbial networks under long-term inorganic fertilization [49,50]. These results implied that achieving higher crop yields through chemical fertilization might come at the cost of reduced network complexity. However, a recent study proposed that a simpler microbial network might indicate weaker cascading effects, which could make ecosystems less susceptible to cascading biodiversity loss, potentially enhancing ecosystem resilience [51].

The complexity was positively correlated with Acidobacteriota and Planctomycetota, and negatively correlated with Bacteroidota and Desulfobacterota (Table 5). Acidobacteriota and Planctomycetota are typically oligotrophic bacteria, whereas Bacteroidota are considered as the copiotrophic bacteria [52,53]. This outcome is consistent with Chen et al. [54], who suggested that chemical fertilizer application increased the concentration of fast-acting nutrients in soils, shifting microbial interactions from cooperative processes toward direct competition for abundant resources, thereby reducing the complexity of microbial networks.

The stability was highest under NPK and NPKS, followed by NPKP and NPKN, with CK showing the lowest stability (Figure 7D). This is consistent with Yang et al. [55], who also observed enhanced microbial network stability under inorganic fertilization. The divergent trends observed between microbial network complexity and stability are not unexpected, as the complexity reflects a structural attribute, while the stability relates to a functional one [56]. The stability was positively associated with Actinobacteriota and negatively with Planctomycetota. Actinobacteriota are regarded as generalists due to their high metabolic diversity and ecological adaptability, whereas Planctomycetota are often recognized as specialists owing to their single metabolic capabilities and niche specialization [57,58]. This supports the view that taxa with broader functional diversity and environmental adaptability contribute more significantly to network stability.

The stability of soil biota network might serve as a better predictor of soil multifunctionality than complexity or biodiversity in disturbed agroecosystems, with more stable networks consistently supporting higher levels of multifunctionality [2]. Although rice yields under NPKS and NPK were comparable to those under NPKN and NPKP, the former two treatments utilized lower fertilizer inputs and demonstrated higher network stability. Considering crop yield, agroecosystem sustainability and environmental impacts, NPK and NPKS emerge as the most recommended fertilization regimes for rice production in this study region.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the dynamics of soil bacterial communities under different fertilization regimes across multiple rice growth stages. Rice growth stages were the primary factor influencing soil bacterial diversity, which progressively declined throughout the growing season, largely driven by DMT. In contrast, fertilization had a stronger effect on the community structure, with soil pH identified as the most influential factor. Fertilization also played a dominant role in shaping bacterial network properties: fertilizer addition reduced network complexity, likely due to a shift in bacterial interactions from cooperation toward direct competition for concentrated nutrients. However, fertilized treatments, especially NPK and NPKS, exhibited higher network stability, which was associated with an increase in bacterial taxa with broader functional diversity and environmental adaptability. Altogether, we recommend NPK and NPKS as optimal fertilization strategies for this region. These insights improve our understanding of the successional dynamics of soil bacterial communities in response to fertilization during crop development and provide a scientific basis for designing sustainable agricultural practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15232466/s1, Figure S1: Rarefaction curves of cumulative ASVs for all samples; Figure S2: UpSet plots illustrating quantitative intersection of ASVs among rice growth stages (A) and fertilization regimes (B); Figure S3: Determination of the correlation threshold for bacterial network using Random Matrix Theory (RMT); Table S1: Soil properties in different rice growth stages and fertilization treatments; Table S2: The top 5 biomarkers for LDA scores for each stage and treatment including phylum (P_), class (C_), order (O_), family (F_), and genus (G_) taxonomic levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.X.; methodology, A.X. and X.Z.; software, Y.Z.; investigation, A.X. and H.W.; data curation, A.X. and Q.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.X.; writing—review and editing, A.X. and X.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, A.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of Fujian province, grant number 2023J05063; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42407193; the Extension Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number GJYS250502; the Public Welfare Project of Fujian Province, grant number 2024R1024002; the Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Funds Project, grant number 2023L3022; and Fujian Provincial Tobacco Monopoly Bureau, grant number 2025350000240078.

Data Availability Statement

Data are deposited into NCBI (PRJNA1357871).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CK | No fertilization |

| NPK | Chemical fertilizer |

| NPKN | NPK supplemented with extra N |

| NPKP | NPK supplemented with extra P |

| NPKS | NPK supplemented with rice straw |

| DMT | Daily mean temperature |

| SWC | Soil water content |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

References

- Yuan, S.; Linquist, B.A.; Wilson, L.T.; Cassman, K.G.; Stuart, A.M.; Pede, V.; Miro, B.; Saito, K.; Agustiani, N.; Aristya, V.E.; et al. Sustainable intensification for a larger global rice bowl. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Li, J.; Liao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Zhao, J. Stable Soil Biota Network Enhances Soil Multifunctionality in Agroecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xia, L.; Ti, C. Win-win nitrogen management practices for improving crop yield and environmental sustainability. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2018, 33, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, M. Effect of bio-organic fertilizers partially substituting chemical fertilizers on labile organic carbon and bacterial community of citrus orchard soils. Plant Soil 2023, 483, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, H.; Xie, X.; Gao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Nie, J. Long-term application of legume green manure improves rhizosphere soil bacterial stability and reduces bulk soil bacterial stability in rice. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2024, 122, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, C.; Kong, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Canopy light and nitrogen distributions are related to grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Field Crops Res. 2017, 206, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Gu, J.; Yang, J. Effects of long-term straw returning on rice yield and soil properties and bacterial community in a rice-wheat rotation system. Field Crops Res. 2023, 291, 108800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Su, W.; Chen, H.; Barberán, A.; Zhao, H.; Yu, M.; Yu, L.; Brookes, P.C.; Schadt, C.W.; Chang, S.X.; et al. Long-term nitrogen fertilization decreases bacterial diversity and favors the growth of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in agro-ecosystems across the globe. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Organic amendments enhance soil microbial diversity, microbial functionality and crop yields: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, M.; Yin, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Qin, W. Effect of organic material addition on active soil organic carbon and microbial diversity: A meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 241, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z.; Ran, W.; Cui, Z. Succession of Composition and Function of Soil Bacterial Communities During Key Rice Growth Stages. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Qin, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Wei, W. Effect of long-term fertilization on bacterial composition in rice paddy soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, L.; Yanan, B.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Tian, M.; Wangting, Y.; Jin, J.; et al. Response of potential activity, abundance and community composition of nitrite-dependent anaerobic methanotrophs to long-term fertilization in paddy soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 5005–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Li, S.-L.; Chen, Q.-L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Guo, Z.-F.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-G. Fertilization regulates global thresholds in soil bacteria. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adithya, S.; Nunna, S.A.D.; Chinnadurai, C.; Balachandar, D. Rhizosphere bacterial diversity and soil biological attributes of rice in different phenological stages and wetland cultivation methods. Pedosphere 2024, 35, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Su, N.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Peng, J.; Rong, X.; Luo, G. Knowledge-based phosphorus input levels control the link between soil microbial diversity and ecosystem functions in paddy fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrune, F.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Colinet, G.; Hiel, M.-P.; Bodson, B.; Taminiau, B.; Daube, G.; Vandenbol, M.; Hartmann, M. Temporal Dynamics of Soil Microbial Communities below the Seedbed under Two Contrasting Tillage Regimes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, C.; Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q. Wheat and Rice Growth Stages and Fertilization Regimes Alter Soil Bacterial Community Structure, But Not Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y. Balance between community assembly processes mediates species coexistence in agricultural soil microbiomes across eastern China. ISME J. 2020, 14, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.J.; Van Altena, C.; De Ruiter, P.C.; Van Gerven, L.P.; Janse, J.H.; Mooij, W.M. Food-web stability signals critical transitions in temperate shallow lakes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoogen, J.; Geisen, S.; Routh, D.; Ferris, H.; Traunspurger, W.; Wardle, D.A.; De Goede, R.G.; Adams, B.J.; Ahmad, W.; Andriuzzi, W.S. Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature 2019, 572, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, W.; Xiao, N.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; et al. Decreased soil multifunctionality is associated with altered microbial network properties under precipitation reduction in a semiarid grassland. iMeta 2023, 2, e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Xue, K.; Chen, S.-L.; Wang, X.-M.; Chen, T.; Kang, S.-C.; Rui, J.-P.; Thies, J.E.; et al. Reduced microbial stability in the active layer is associated with carbon loss under alpine permafrost degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025321118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis; SSSA Book Series; American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Meng, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z. Agricultural land use affects nitrate production and conservation in humid subtropical soils in China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 62, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Meth. 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.; Lex, A.; Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: An R Package For The Visualization Of Intersecting Sets And Their Properties. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2938–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Guo, Z.; Pan, K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Pan, X.J. Increasing land-use durations enhance soil microbial deterministic processes and network complexity and stability in an ecotone. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 181, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhong, J.; Yang, Y.; Scheuermann, R.H.; Zhou, J. Application of random matrix theory to biological networks. Phys. Lett. A 2006, 357, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R.J.M. Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability. Microbiome 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, X.; Weng, B.; Su, J.; Nie, S.a.; Gilbert, J.A.; Zhu, Y.-G. The phenological stage of rice growth determines anaerobic ammonium oxidation activity in rhizosphere soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 100, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Dumack, K.; Anantharaman, K.; Ma, B.; He, Y.; Liu, W.; Di, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, J. Temperature-dependent trophic associations modulate soil bacterial communities along latitudinal gradients. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Deng, Y.; Shen, L.; Wen, C.; Yan, Q.; Ning, D.; Qin, Y.; Xue, K.; Wu, L.; He, Z.; et al. Temperature mediates continental-scale diversity of microbes in forest soils. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, T.E.; Tucker, C.; Alonso-Rodríguez, A.M.; Loza, M.I.; Grullón-Penkova, I.F.; Cavaleri, M.A.; O’Connell, C.S.; Reed, S.C. Warming induces unexpectedly high soil respiration in a wet tropical forest. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Johnston, E.R.; Barberán, A.; Ren, Y.; Lü, X.; Han, X. Decreased plant productivity resulting from plant group removal experiment constrains soil microbial functional diversity. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4318–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, B.; Shi, J.; Liao, M.; He, K.; Tian, H.; Megharaj, M.; He, W. Arsenic stress on soil microbial nutrient metabolism interpreted by microbial utilization of dissolved organic carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Shi, J.; Lin, W.; Liang, J.; Lu, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, C. Soil Bacteria Mediate Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration under Different Tillage and Straw Management in Rice-Wheat Cropping Systems. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Li, T.; Dou, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Chang, S. Nitrogen fertilization weakens the linkage between soil carbon and microbial diversity: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 6446–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sansupa, C.; Sereenonchai, S.; Hatano, R. Stability of soil bacteria in undisturbed soil and continuous maize cultivation in Northern Thailand. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1285445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Dong, L.; Wang, W. Grassland degradation amplifies the negative effect of nitrogen enrichment on soil microbial community stability. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guan, Y. Consistent responses of soil bacterial communities to bioavailable silicon deficiency in croplands. Geoderma 2022, 408, 115587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Bai, L.; Guo, J. Modeling phosphorus dynamics in rice irrigation systems: Integrating O-Fe-P coupling and regional water cycling. J. Hydrol. 2025, 649, 132405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, B.; Nayak, S.; Pahari, A.; Nayak, S. Verrucomicrobia in soil: An agricultural perspective. In Frontiers in Soil and Environmental Microbiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; McGrath, S.P.; Hirsch, P.R.; Clark, I.M.; Storkey, J.; Wu, L.; Zhou, J.; Liang, Y. Plant–microbe networks in soil are weakened by century-long use of inorganic fertilizers. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Rui, J.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Bai, Y.; Heděnec, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Pei, K.; Liu, C.; et al. Rate-specific responses of prokaryotic diversity and structure to nitrogen deposition in the Leymus chinensis steppe. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 79, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, A.M.; Drescher, J.; Darras, K.; Wenzel, A.; Janotta, N.; Nazarreta, R.; Kasmiatun; Laurent, V.; Mawan, A.; Utari, E.H. Rainforest transformation reallocates energy from green to brown food webs. Nature 2024, 627, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Sun, C.; Luo, W.; Gong, Y.; Tang, X. Distinct ecological niches and community dynamics: Understanding free-living and particle-attached bacterial communities in an oligotrophic deep lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e00714–e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Cai, Z.; Penuelas, J.; Huang, X. Soil Nutrient Enrichment Induces Trade-Offs in Bacterial Life-History Strategies Promoting Plant Productivity. Adv. Sci. 2025, e10066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, T.; He, H.; Liu, J.; Duan, C.; Cui, Y.; Huang, M.; Wu, C.; Fang, L. High nitrogen fertilizer input enhanced the microbial network complexity in the paddy soil. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 6, 230205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Sun, R.; Li, J.; Zhai, L.; Cui, H.; Fan, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, H. Combined organic-inorganic fertilization builds higher stability of soil and root microbial networks than exclusive mineral or organic fertilization. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2022, 5, 220142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Qiao, Z.; Tikhonenkov, D.V.; Gong, Y.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Sun, K.; Huo, D. Temporal Dynamics and Adaptive Mechanisms of Microbial Communities: Divergent Responses and Network Interactions. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka Essaid, A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Klenk, H.-P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel Gilles, P. Taxonomy, Physiology, and Natural Products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yue, Y.; Nair, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Adaptive traits of Planctomycetota bacteria to thrive in macroalgal habitats and establish mutually beneficial relationship with macroalgae. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2024, 9, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).