Spray Deposition, Drift and Equipment Contamination for Drone and Conventional Orchard Spraying Under European Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Field

2.1.1. Spraying

2.1.2. Weather Conditions Measurement

2.2. Spraying Equipment

2.2.1. Drone—Technical Parameters and Spraying Parameters

2.2.2. Orchard Sprayer—Technical Parameters and Spraying Parameters

2.3. Field Measurements

2.3.1. Spray Deposit Measurement

2.3.2. Spray Drift Measurement

Air Drift Measurements

Sedimentation Drift Measurements

2.3.3. Measurements of Spraying Equipment Contamination (Drone and Sprayer)

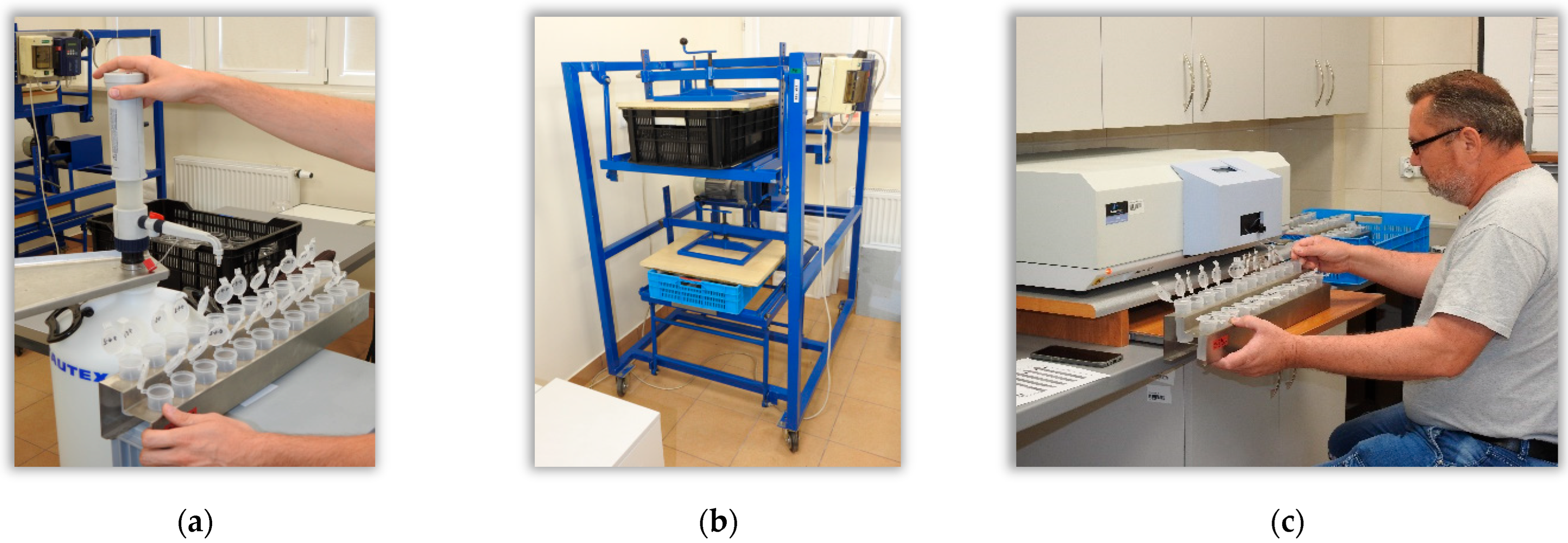

2.4. Laboratory Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analyses and Other Calculations

- deposition on the upper surfaces of the leaves—U;

- deposition on the lower surfaces of the leaves—L;

- total deposition on both leaf surfaces—U + L;

- the ratio of deposition on the upper leaf surfaces to deposition on the lower leaf surfaces—U/L.

- average values for entire trees;

- average values in the upper zone of trees (the two upper measurement locations on the masts, Figure 9a) (Tree Top—TT);

- average values in the lower zone of trees (the two lower measurement locations on the masts, Figure 9a) (Tree Bottom—TB);

- average values in the windward layer of the tree (Figure 9b) (Tree Windward—TW);

- average values in the leeward layer of the tree (Figure 9b) (Tree Leeward—TL).

- the ratio of the deposition value in the upper zone of the trees to the average deposition value in the lower zone (Figure 9a) Tree Top/Bottom (T-T/B);

- the ratio of deposition in the windward zone of sprayed trees to the deposition in the leeward zone of sprayed trees (Figure 9b) Tree Windward/Leeward (T-W/L).

3. Results and Discussion

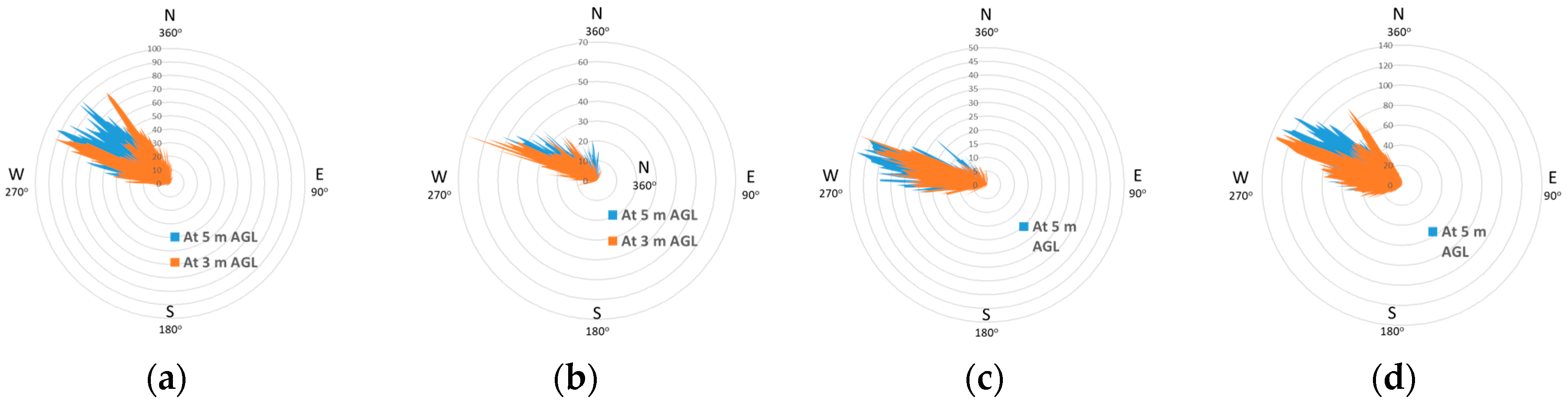

3.1. Weather Conditions

- —mean value of the cosines of the measured wind direction angles;

- —mean value of the sines of the measured wind direction angles.

3.2. In-Tree Deposition

- Total deposition (U + L): in the windward layer (Table 7);

- Deposition on upper surfaces (U): for the ratio of deposition in the upper zone to deposition in the lower zone (T-T/B) and for deposition in the windward layer (TW) (Table 8);

- Deposition on lower surfaces (L): for the T-T/B ratio and for the T-W/L ratio (the combination was also not significant, similarly for deposition in the windward zone) (Table 9);

- U/L uniformity index: in the upper tree zone (TT), the lower tree zone (TB), and in the leeward layer (TL) (Table 10).

3.3. Spray Drift

3.3.1. Airborne Drift

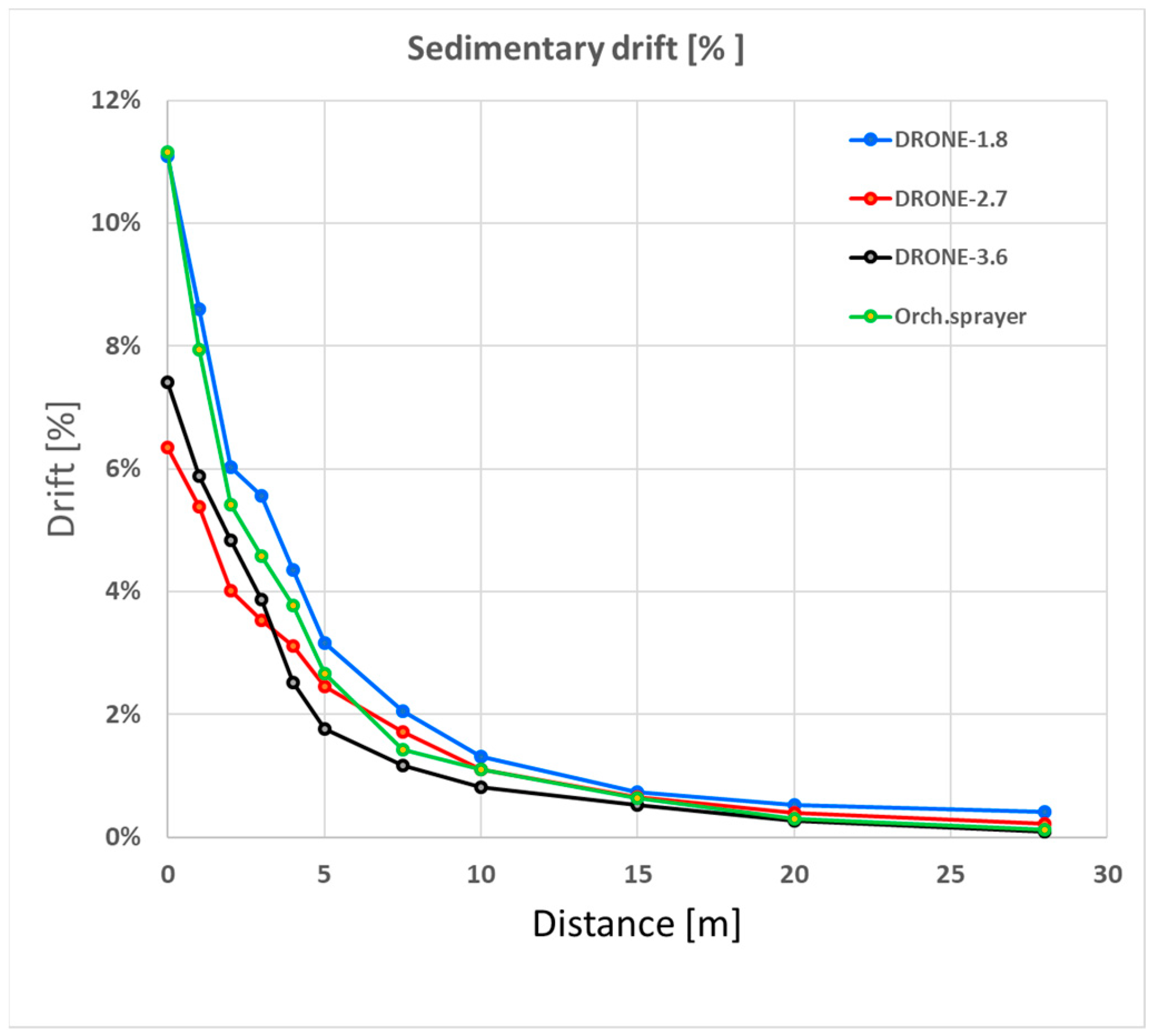

3.3.2. Sedimentation Drift

3.4. Contamination of Spraying Equipment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitford, F.; Virk, S.; Young, B.; Li, S.; Helms, A.; Ozkan, E.; Adair, A.; Medenwald, H.; Butts, T.; Shanks, A.; et al. The Evolution of Spray Drones: Their Capabilities and Challenges for Pesticide Applications. 2025. Available online: https://ag.purdue.edu/department/extension/ppp/resources/ppp-publications/_docs/ppp-154.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Gao, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.; Liao, M.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, M.; Shi, Y.; Cao, H. Effect of application method and formulation on prothioconazole residue behavior and mycotoxin contamination in wheat. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 139019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2009, 309, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Biglia, A.; Grella, M.; Bloise, N.; Comba, L.; Mozzanini, E.; Sopegno, A.; Pittarello, M.; Dicembrini, E.; Eloi Alcatrão, L.; Guglieri, G.; et al. UAV-spray application in vineyards: Flight modes and spray system adjustment effects on canopy deposit, coverage, and off-target losses. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. Development of a recognition system for spraying areas from unmanned aerial vehicles using a machine learning approach. Sensors 2019, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnacki, J.; Pachuta, A. Impact of the parameters of spraying with a small unmanned aerial vehicle on the distribution of liquid on young cherry trees. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Chen, P.; Yao, W.; Yan, Y.; Zeng, T.; Chen, S.; Lan, Y. Evaluation of aerial spraying application of multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle for Areca catechu protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1093912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsari, P.; Grella, M.; Marucco, P.; Matta, F.; Miranda-Fuentes, A. Assessing the influence of air speed and liquid flow rate on the droplet size and homogeneity in pneumatic spraying. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruchowski, G.; Hołownicki, R.; Godyń, A.; Świechowski, W. Calibration of orchard sprayers–the parameters and methods. In Proceedings of the Fourth European Workshop on Standardised Procedure for the Inspection of Sprayers in Europe (SPISE 4), Lana, Italy, 27–29 March 2012; Volume 439, pp. 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, L.; Wu, Y.; Musiu, E.M.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, P. Numerical simulation of airflow field from a six-rotor plant protection drone using lattice Boltzmann method. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 197, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lan, Y.; Wen, S.; Hewitt, A.J.; Yao, W.; Chen, P. Meteorological and flight altitude effects on deposition, penetration, and drift in pineapple aerial spraying. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 15, e2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, A.S.; Han, X.; Yu, S.-H. Independent control spraying system for UAV-based precise variable sprayer: A review. Drones 2022, 6, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 24253-2:2015; Crop Protection Equipment—Spray Deposition Test for Field Crop—Part 2: Measurement in a Crop. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 22522:2007; Crop Protection Equipment—Field Measurement of Spray Distribution in Tree and Bush Crops. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- ISO 22369-1:2006; Crop Protection Equipment—Drift Classification of Spraying Equipment—Part 1: Classes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 23117-2:2025; Agricultural and Forestry Machinery—Unmanned Aerial Spraying Systems—Part 2: Test Methods to Assess the Horizontal Transverse Spray Distribution. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Hołownicki, R.; Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Bartosik, A.; Konopacki, P.; Godyń, A. Influence of air-jet configuration on spray deposit and drift in a blackcurrant plantation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, C.; Du, G.; Yu, F.; Yao, W.; Lan, Y. Evaluating the use of unmanned aerial vehicles for spray applications in mountain Nanguo pear orchards. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3590–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yi, T.; Han, P.; Zhang, R.; Pan, L. Effect of flight velocity on droplet deposition and drift of combined pesticides sprayed using an unmanned aerial vehicle sprayer in a peach orchard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 981494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lan, Y.; Wang, G.; Hussain, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Shan, C.; Wang, B.; Song, C. Evaluation of the deposition and distribution of spray droplets in citrus orchards by plant protection drones. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1303669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, S.; Yao, W.; Deng, J. Drift and deposition of pesticide applied by UAV on pineapple plants under different meteorological conditions. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, J.G.P.; van de Zande, J.C.; Wenneker, M.; Stallinga, H.; van Velde, P. External loading of an orchard sprayer with agrochemicals during application. Asp. Appl. Biol.-Int. Adv. Pestic. Appl. 2012, 114, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Balsari, P.; Marucco, P. Internal and external contamination of sprayers: Causes and strategies to minimise negative effects on the environment. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 58, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Wang, T.; Cao, F.; Yu, C.; Chu, Q.; Wang, F. A comparative study on the adsorption behavior of pesticides by pristine and aged microplastics from agricultural polyethylene soil films. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrow, J.E.; Wong, J.M.; Seiber, J.N. Pesticide residues in spray aircraft tank rinses and aircraft exterior washes. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1989, 42, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Munguía, A.; Guerra-Ávila, P.L.; Islas-Ojeda, E.; Flores-Sánchez, J.L.; Vázquez-Martínez, O.; García-Munguía, A.M.; García-Munguía, O. A review of drone technology and operation processes in agricultural crop spraying. Drones 2024, 8, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Lan, Y.; Huang, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Xiao, H. Droplet deposition and control of planthoppers of different nozzles in two-stage rice with a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Agronomy 2020, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Guanter, J.; Agüera, P.; Agüera, J.; Pérez-Ruiz, M. Spray and economic assessment of a UAV-based ultra-low-volume application in olive and citrus orchards. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyurt, H.B.; Duran, H.; Çelen, İ.H. Determination of the application parameters of spraying drones for crop protection in hazelnut orchards. J. Tekirdag Agric. Fac. 2022, 19, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengeru, Y.; Ramasamy, K.; Allimuthu, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Kumar, A.P.M.; Kannan, B.; Karuppasami, K.M. Study on spray deposition and drift characteristics of UAV agricultural sprayer for application of insecticide in redgram crop (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.D.L.; Cunha, J.P.A.R.D.; Nomelini, Q.S.S. Use of unmanned aerial vehicle for pesticide application in soybean crop. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 2049–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallappa, D.; Kavitha, R.; Surendrakumar, A.; Suthakar, B.; Mohan Kumar, A.P.; Kalarani, M.K.; Kannan, B. Effect of downwash airflow distribution of multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle on spray droplet deposition characteristics in rice crop. Curr. Sci. 2023, 125, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhigarjan, A.; Safari, M.; Ghazi, M.M.; Zarnegar, A.; Shahrokhi, S.; Bagheri, N.; Moein, S.; Seyedin, P. Chemical control of wheat sunn pest (Eurygaster integriceps) by UAV sprayer and very low volume knapsack sprayer. Phytoparasitica 2024, 52, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wongsuk, S.; Wu, X.; He, X. Spray performance evaluation of a six-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle sprayer for pesticide application using an orchard operation mode in apple orchards. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2449–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Müller, J.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, Z.; He, M.; Liu, Y.; et al. Effect of operational parameters of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) on droplet deposition in trellised pear orchard. Drones 2023, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, D.; Martelloni, L.; Rimediotti, M.; Lisci, R.; Lombardo, S.; Vieri, M. Testing a multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle for spray application in high slope terraced vineyard. J. Agric. Eng. 2019, 50, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Singh, M.; Parmar, R.; Bhullar, K. Feasibility study on hexacopter UAV based sprayer for application of environment-friendly biopesticide in guava orchard. J. Environ. Biol. 2022, 43, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhong, W.; Liu, C.; Su, J.; Lan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M. UAV spraying on citrus crop: Impact of tank-mix adjuvant on the contact angle and droplet distribution. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 22866:2005; Equipment for Crop Protection—Methods for Field Measurement of Spray Drift. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 22369-2:2010; Crop Protection Equipment—Drift Classification of Spraying Equipment—Part 2: Classification of Field Crop Sprayers by field measurements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Wang, C.; Herbst, A.; Zeng, A.; Wongsuk, S.; Qiao, B.; Qi, P.; Bonds, J.; Overbeck, V.; Yang, Y.; Gao, W.; et al. Assessment of spray deposition, drift and mass balance from unmanned aerial vehicle sprayer using an artificial vineyard. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godyń, A.; Doruchowski, G.; Hołownicki, R.; Świechowski, W.; Masny, A.; Michalecka, M.; Piotrowski, W. The effect of the tunnel spraying technique and nozzle type on the spray deposit and drift during spray application in strawberries in ground cultivation. Agric. Eng. 2024, 28, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Hołownicki, R.; Godyń, A.; Bartosik, A. Effect of airflow settings of an orchard sprayer with two individually controlled fans on spray deposition in apple trees and off-target drift. Agriculture 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Salyani, M.; Cromwell, R.P. Spray drift from ground and aerial applications. Trans. ASAE 1992, 35, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenneker, M.; van de Zande, J.C. Spray drift reducing effects of natural windbreaks in orchard spraying. Asp. Appl. Biol. Int.-Adv. Pestic. Appl. 2008, 84, 25. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40801850_Spray_drift_reducing_effects_of_natural_windbreaks_in_orchard_spraying (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Grella, M.; Marucco, P.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Balsari, P. Spray drift generated in vineyard during under-row weed control and suckering: Evaluation of direct and indirect drift-reducing techniques. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Combination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 | |

| Flight/Ground Speed [m·s−1] | 1.8 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 1.7 (6.0 km·h−1) |

| Flight height AGL [m]—May | 8–9 | N/A | ||

| Flight height AGL [m]—September | 7–8 | N/A | ||

| Spray volume [l·ha−1]—May | 27 | 400 | ||

| Spray volume [l·ha−1]—September | 40 | 400 | ||

| Nozzle [type] Pressure [bar] | Rotational CDA | Lechler TR 80 15 @ 6.6 bar | ||

| Nozzle number | 2 | 16 | ||

| Droplets VMD [µm] | 195 | ca 150 | ||

| Tracer dose—BF7G [g·ha−1] | 1200 g/ha | |||

| General Specifications of ABZ Innovation L10 | |

|---|---|

| Total weight (without batteries) | 13.6 kg |

| Max. Take-off weight | 29 kg |

| Dimensions | 1460 × 1020 × 610 [mm] |

| GPS | GPS, GLONAS, Galileo |

| Hovering precision | ±10 cm (RTK) ±2 m (without RTK) |

| Battery capacity | 16,000 mAh |

| Battery voltage | 44.4V |

| Battery weight | 4.7 kg |

| Spraying | |

| Per Hectare Performance | 10 ha/h |

| Spraying system | rotational CDA |

| Number of nozzles | 2 |

| Droplet size (adjustable) | 40–1000 µm |

| Adjustable working width | 1.5–6.0 m |

| Pump type | Membrane |

| Maximum liquid flow | 5 L·min−1 |

| Pump operating voltage | 48 V |

| Flight | |

| Max. Pitch angle | 30° |

| Max operating flight speed | 7 m·s−1 |

| Max level speed | 24 m·s−1 |

| Max flight altitude | 120 m |

| Max tolerable wind speed | 10 m·s−1 |

| Altitude measurement | LIDAR |

| Description of the Sample Placement Location | Samples | Drone Area Represented (cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Area (cm2) | Dimensions (cm × cm) | ||

| Casing | 1, 2 | 2 × 36 | 6 × 6 | 210.0 |

| Tank | 3–8 | 6 × 36 | 6 × 6 | 2287.6 |

| Case | 9–14 | 6 × 36 | 6 × 6 | 862.0 |

| Propellers carriers | 15–22 | 8 × 72 | 12.5 × 5.76 | 2968.4 |

| Drone base (legs, crossbars) | 23–34 | 12 × 36 | 6 × 6 | 1356.8 |

| Nozzles holders | 35–38 | 4 × 36 | 7.5 × 4.8, 6 × 6 | 531.2 |

| Description of the Sample Placement Location | Samples | Sprayer Area Represented (cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Area (cm2) | Dimensions (cm × cm) | ||

| Sprayer | ||||

| Fan | 1–10 | 10 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 41,314.6 |

| Tank | 11–18 | 8 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 49,338.0 |

| Sprayer wheels | 19–22 | 4 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 5652.0 |

| Tractor | ||||

| Windows (left, right, front, rear) | 23–30 | 8 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 3825.0 |

| Tractor roof | 31, 32 | 2 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 11,700.0 |

| Tractor rear wheels | 33–36 | 4 × 64 | 8 × 8 | 13,364.0 |

| Parameter/Combination | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automatic measurement of wind direction and wind speed [m·s−1] parameters | ||||

| Mean direction at 3 m AGL | 293° | 287° | 282° | 292° |

| Mean direction at 5 m AGL | 300° | 287° | 286° | 294° |

| Wind dir. consist. (R) at 3 m AGL | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.92 |

| Wind dir. consist. (R) at 5 m AGL | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Speed (10th–90th percentile) at 3 m | 1.47–4.70 | 1.56–4.05 | 1.61–4.22 | 1.55–3.45 |

| Speed (10th–90th percentile) at 5 m | 2.03–5.90 | 1.84–5.38 | 2.12–5.06 | 2.16–4.56 |

| Mean speed at 3 m AGL | 2.84 | 2.74 | 2.83 | 2.41 |

| Mean speed at 5 m AGL | 3.93 | 3.46 | 3.75 | 3.29 |

| Wind speed CV at 3 m AGL [%] | 43.3 | 34.8 | 35.9 | 30.7 |

| Wind speed CV at 5 m AGL [%] | 37.9 | 38.8 | 30.5 | 27.2 |

| Spraying duration [s] | 211 | 107 | 90 | 318 |

| Manual measurement of wind speed and direction, temperature and humidity | ||||

| Mean speed at 2.5 m AGL Speed range (min.–max.) | 2.76 0.9–5.5 | 3.04 0.4–5.3 | 3.62 1.7–5.6 | 2.43 1.2–3.6 |

| Wind direction range at 2.5 m AGL | 280–315° | 280–310° | 280–310° | 280–310° |

| Air temperature [°C] | 31.2 | 30.4 | 32.1 | 32.1 |

| Relative air humidity [%] | 26.5 | 20.8 | 17.9 | 19.4 |

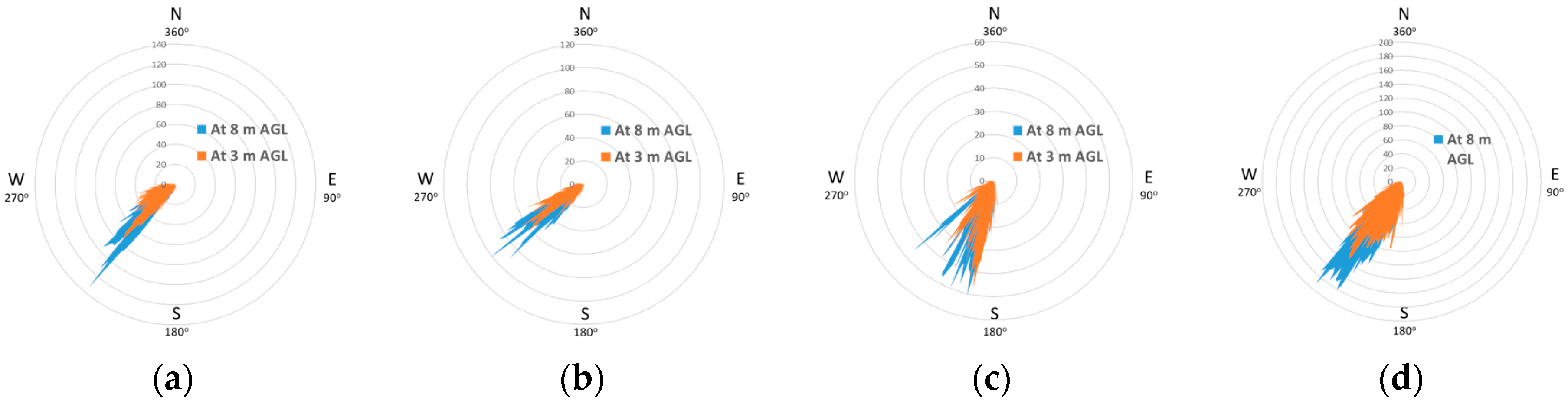

| Parameter/Combination | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automatic measurement of wind direction [°] and wind speed [m·s−1] parameters | ||||

| Mean direction at 3 m AGL | 234° | 236° | 208° | 213° |

| Mean direction at 8 m AGL | 228° | 231° | 206° | 214° |

| Wind dir. consist. (R) at 3 m AGL | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| Wind dir. consist. (R) at 8 m AGL | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Speed (10th–90th percentile) at 3 m | 1.01–2.78 | 1.22–2.87 | 1.26–3.64 | 1.22–3.36 |

| Speed (10th–90th percentile) at 8 m | 2.09–3.79 | 2.45–3.52 | 1.96–4.58 | 1.60–4.40 |

| Mean speed at 3 m AGL | 1.94 | 2.10 | 2.36 | 2.33 |

| Mean speed at 8 m AGL | 2.96 | 3.00 | 3.17 | 3.18 |

| Wind speed CV at 3 m AGL [%] | 35.5 | 32.0 | 37.7 | 36.3 |

| Wind speed CV at 8 m AGL [%] | 22.3 | 13.9 | 30.2 | 31.2 |

| Spraying duration [s] | 144 | 104 | 87 | 327 |

| Manual measurement of wind speed [m·s−1] and direction [°], temperature and humidity | ||||

| Mean speed at 2.5 m AGL | 1.90 | 1.82 | 1.48 | 1.43 |

| Speed range (min.–max.) | 0.9–3.1 | 1.2–2.5 | 0.5–2.4 | 0.9–1.7 |

| Wind direction range at 2.5 m AGL | 250–270° | 250–270° | 250–270° | 250–270° |

| Air temperature [°C] | 26.1 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 28.6 |

| Relative air humidity [%] | 42.6 | 43.5 | 40.3 | 36.6 |

| Tree Zone | Term | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The whole tree | 1 | 1380.5 a | 1992.8 a | 1607.2 a | 2722.4 b |

| 2 | 3798.6 c | 1573.4 a | 1507.2 a | 3736.4 c | |

| Lower tree zone TB | 1 | 629.8 a | 1293.9 b | 797.5 ab | 2280.9 c |

| 2 | 2640.2 c | 890.9 ab | 903.3 ab | 2570.7 c | |

| Upper tree zone TT | 1 | 2131.1 a | 2691.7 a | 2416.8 a | 3164.0 a |

| 2 | 4957.0 b | 2255.9 a | 2111.2 a | 4902.2 b | |

| Leeward layer TL | 1 | 1160.3 a | 763.1 a | 910.7 a | 2539.1 b |

| 2 | 3156.2 b | 1203.7 a | 1207.3 a | 3162.2 b | |

| Windward layer TW | 1 | 2118.1 a | 4432.2 cd | 3186.0 a–c | 3723.4 bc |

| 2 | 5953.8 e | 2393.6 ab | 2185.2 ab | 5256.0 de | |

| Ratio T-T/B | 1 | 3.40 c | 2.30 a–c | 2.96 bc | 1.40 a |

| 2 | 1.97 ab | 2.55 a–c | 2.45 a–c | 1.94 ab | |

| Ratio T-W/L | 1 | 2.71 a | 8.89 b | 3.78 a | 1.47 a |

| 2 | 2.65 a | 2.20 a | 2.17 a | 1.67 a |

| Tree Zone | Term | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The whole tree | 1 | 1253.0 a | 1905.8 a | 1473.6 a | 1251.8 a |

| 2 | 3472.0 b | 1433.2 a | 1337.4 a | 1797.2 a | |

| Lower tree zone TB | 1 | 521.1 a | 1227.6 cd | 662.9 ab | 1185.9 b–d |

| 2 | 2154.0 e | 757.6 a–c | 802.0 a–c | 1356.0 d | |

| Upper tree zone TT | 1 | 1985.0 a | 2584.1 a | 2284.4 a | 1317.6 a |

| 2 | 4790.0 b | 2108.9 a | 1872.8 a | 2238.3 a | |

| Leeward layer TL | 1 | 1073.6 a | 693.1 a | 764.7 a | 1277.1 a |

| 2 | 2826.2 b | 1094.4 a | 1021.8 a | 1512.1 a | |

| Windward layer TW | 1 | 1901.9 a | 4313.2 b | 2983.7 a | 1623.0 a |

| 2 | 5597.4 b | 2190.4 a | 1995.7 a | 2374.7 a | |

| Ratio T-T/B | 1 | 4.1 c | 2.3 ab | 3.6 bc | 1.2 a |

| 2 | 2.4 ab | 2.8 a–c | 2.5 a–c | 1.7 a | |

| Ratio T-W/L | 1 | 2.6 a | 9.6 b | 4.9 a | 1.3 a |

| 2 | 3.0 a | 2.2 a | 2.3 a | 1.8 a |

| Tree Zone | Term | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The whole tree | 1 | 127.45 a | 86.95 a | 133.51 a | 1470.66 b |

| 2 | 326.61 a | 140.17 a | 169.89 a | 1939.29 c | |

| Lower tree zone TB | 1 | 108.75 a | 66.33 a | 134.61 a | 1094.96 c |

| 2 | 486.19 b | 133.29 a | 101.31 a | 1214.61 c | |

| Upper tree zone TT | 1 | 146.15 a | 107.57 a | 132.41 a | 1846.35 b |

| 2 | 167.03 a | 147.05 a | 238.47 a | 2663.97 c | |

| Leeward layer TL | 1 | 86.6 a | 70.0 a | 146.0 a | 1262.0 b |

| 2 | 330.0 a | 109.2 a | 185.4 a | 1650.1 c | |

| Windward layer TW | 1 | 216.2 a | 118.9 a | 202.4 a | 2100.4 b |

| 2 | 356.3 a | 203.2 a | 189.5 a | 2881.2 c | |

| Ratio T-T/B | 1 | 2.05 ab | 1.77 ab | 1.38 ab | 1.88 ab |

| 2 | 0.36 a | 1.24 ab | 2.35 c | 2.21 c | |

| Ratio T-W/L | 1 | 3.58 a | 2.38 a | 1.98 a | 1.73 a |

| 2 | 1.33 a | 2.01 a | 1.48 a | 1.73 a |

| Tree Zone | Term | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The whole tree | 1 | 18.73 c | 24.89 c | 19.33 c | 1.51 a |

| 2 | 22.47 c | 11.24 b | 11.75 b | 1.48 a | |

| Lower tree zone TB | 1 | 7.25 ab | 21.65 c | 12.83 b | 1.92 a |

| 2 | 9.96 b | 6.71 ab | 12.99 b | 1.76 a | |

| Upper tree zone TT | 1 | 30.22 d | 28.13 d | 25.83 cd | 1.09 a |

| 2 | 34.98 d | 15.77 bc | 10.50 ab | 1.21 a | |

| Leeward layer TL | 1 | 19.63 bc | 10.61 ab | 8.00 a | 1.96 a |

| 2 | 23.78 c | 11.57 ab | 9.14 a | 1.23 a | |

| Windward layer TW | 1 | 22.27 bc | 51.53 e | 37.57 de | 1.07 a |

| 2 | 29.92 cd | 11.96 ab | 12.83 ab | 1.30 a |

| Height from the Ground [m] | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.0 | 0.94 a | 2.04 a | 8.15 ab | 2.74 a |

| 7.0 | 1.71 a | 2.48 a | 11.32 ab | 3.90 a |

| 6.0 | 3.18 a | 7.07 ab | 16.53 ab | 4.43 a |

| 5.0 | 6.03 a | 14.18 ab | 26.83 bc | 6.49 a |

| 4.0 | 7.95 ab | 62.09 fg | 48.61 d–f | 7.80 ab |

| 3.0 | 14.88 ab | 75.82 g | 41.97 c–e | 9.69 ab |

| 2.0 | 35.06 cd | 101.41 h | 56.09 ef | 10.16 ab |

| 1.0 | 46.02 d–f | 63.52 fg | 48.56 d–f | 9.86 ab |

| Mean (1–8 m) | 14.47 a | 41.08 b | 32.26 b | 6.88 a |

| Upper mast (5–8 m) | 2.97 a | 6.44 a | 15.71 c | 4.39 a |

| Lower mast (1–4 m) | 25.98 b | 75.71 d | 48.81 c | 9.38 a |

| Ratio Upper/Lower | 0.14 ab | 0.09 a | 0.33 bc | 0.54 c |

| Distance [m] | Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.8 a–d | 5.9 a | 6.6 ab | 9.5 a–c |

| 2 | 17.1 c–g | 10.6 a–d | 12.0 a–e | 16.2 c–g |

| 3 | 22.9 g–j | 14.3 b–f | 16.4 c–g | 21.2 f–j |

| 4 | 27.9 i–n | 17.6 d–h | 19.6 e–h | 25.4 h–k |

| 5 | 31.7 k–q | 20.4 f–i | 21.7 f–j | 28.6 j–o |

| 7.5 | 38.2 q–u | 25.7 h–m | 25.3 h–l | 33.7 m–r |

| 10 | 42.4 s–v | 29.2 j–p | 27.8 i–n | 36.9 p–t |

| 15 | 47.5 v–x | 33.5 l–r | 31.2 k–q | 41.2 r–v |

| 20 | 50.6 w–x | 36.2 o–t | 33.1 k–q | 43.5 t–w |

| 28 | 54.4 x | 38.6 q–u | 34.6 n–s | 45.2 u–w |

| Parameter | Combination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drone-1.8 | Drone-2.7 | Drone-3.6 | Orch.Spr.-1.7 | |

| Equipment contamination [mg] | 46.48 + at standstill | 11.98 | 6.85 | 1001.33 |

| Equipment area with samples [m2] | 0.82 | 9.63 | ||

| Area without samples [% of Area with samples] | +30% (without propellers) +78% (with propellers) | +8.3% | ||

| Tractor contamination [mg] | N/A | 2.77 | ||

| Tractor area with samples [m2] | N/A | 6.33 | ||

| Tractor area without samples [% of with …] | N/A | +100% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godyń, A.; Świechowski, W.; Doruchowski, G.; Hołownicki, R.; Bartosik, A.; Sas, K. Spray Deposition, Drift and Equipment Contamination for Drone and Conventional Orchard Spraying Under European Conditions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232467

Godyń A, Świechowski W, Doruchowski G, Hołownicki R, Bartosik A, Sas K. Spray Deposition, Drift and Equipment Contamination for Drone and Conventional Orchard Spraying Under European Conditions. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232467

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodyń, Artur, Waldemar Świechowski, Grzegorz Doruchowski, Ryszard Hołownicki, Andrzej Bartosik, and Konrad Sas. 2025. "Spray Deposition, Drift and Equipment Contamination for Drone and Conventional Orchard Spraying Under European Conditions" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232467

APA StyleGodyń, A., Świechowski, W., Doruchowski, G., Hołownicki, R., Bartosik, A., & Sas, K. (2025). Spray Deposition, Drift and Equipment Contamination for Drone and Conventional Orchard Spraying Under European Conditions. Agriculture, 15(23), 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232467